Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.28 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub May 23, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782023280052

Article

Youth as a viewpoint of social phenomena and the reform of high school — what do you see when you look from another place?

IUniversidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

IIUniversidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

This article seeks to design a new investigative approach in education field of studies, starting from the youth, building it as a “place of observation” of the high school reform. In it, we will, at first, deal with youth as a social position, subject to a variety of living conditions and modes of expression. In a second movement, we will try to demonstrate the analytical possibilities opened up by such an approach to the field of education, based on transition studies and through an analysis exercise on high school and its reform. The results point, firstly, to a definition of youth in which space (place, in Bourdieu’s perspective) and time (flow of history, in Mannheim’s formulation) synthesize the location of this social group (young people). Secondly, by taking high school as a dividing line between different modes of school-work transition, we will demonstrate the impact of the reform on those it casts in the shadows: young people recently included in this level of education.

KEYWORDS youth; school-work transition; high school reform

Este artigo objetiva apresentar o desenho de uma abordagem para o campo da educação, a partir da perspectiva da juventude, construindo-a como um “lugar de observação” da reforma do ensino médio. Nela, trataremos a juventude como posição social, sujeita a uma variedade de condições de vida e de modos de expressão, e procuraremos demonstrar as possibilidades analíticas abertas para o campo da educação, a partir dos estudos de transição para a vida adulta, por meio de um exercício sobre o ensino médio e sua reforma. Os resultados apontam para uma definição de juventude em que espaço (lugar, na perspectiva de Bourdieu) e tempo (fluxo da história, na formulação de Mannheim) sintetizam a localização desse conjunto social (os jovens). E ainda, ao tomarmos o ensino médio como linha divisória entre modos distintos de transição escola-trabalho, demonstraremos o impacto da reforma sobre aqueles que ela joga nas sombras: jovens recentemente incluídos nesse patamar de ensino.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE juventude; transição escola-trabalho; reforma do ensino médio

Este artículo tiene como objetivo presentar un primer diseño de aproximación investigativa al campo de la educación, a partir de la juventud, construyéndola como un “lugar de observación” de la reforma de la enseñanza media. En él, nos ocuparemos, en un primer momento, de la juventud como posición social, sujeta a una variedad de condiciones de vida y modos de expresión. En un segundo movimiento, intentaremos demostrar las posibilidades analíticas que abre tal abordaje del campo de la educación, a partir de los estudios de transición ya través de un ejercicio de análisis sobre la escuela secundaria y su reforma. Los resultados apuntan, en primer lugar, a una definición de juventud en la que el espacio (lugar, en la perspectiva de Bourdieu) y el tiempo (flujo de la historia, en la formulación de Mannheim) sintetizan la ubicación de este grupo social (los jóvenes). En segundo lugar, al tomar la enseñanza media como línea divisoria entre las distintas modalidades de transición escuela-trabajo, mostraremos el impacto de la reforma en aquellos que ensombrece: los jóvenes recién incorporados a este nivel educativo.

PALABRAS CLAVE juventud; transición escuela-trabajo; reforma de la enseñanza media

INTRODUCTION

The high school (HS) reform (Law No. 13,415/17 — Brasil, 2017) has been approached by several authors. An analysis of the productions referring to years after its approval shows us a brief scenario of the debate. Ferreti and Silva (2017), Frigotto and Motta (2017), Leão (2018), Silva (2018), Ferreti (2018) and Corti (2019) are some of the productions on the subject. Altogether, two objects were basically described: the legal frameworks that delimits the construction of the law and its effects on the HS curriculum. On the other hand, the debate becomes more diverse when it comes to the purposes of the reform and the approaches that ground the analyses.

In this sense, the reform can present itself as an expression of the dispute and construction of hegemony; as an expression of the ethical-political expression of thought and capitalist moral; as a field of dispute between educational projects, political programs and conceptions of youth; as a mean for curricular flexibilization and some conception of quality in education; as a mean of curricular contents and formative itineraries; and as a way to fill out an empty significance: the crisis in HS.

As to the approaches for the reform, it is analyzed considering the debate about hegemony under the terms of Gramsci, based on the concepts of political theory by Laclau and Mouffe (Corti, 2019), on the history status of HS in Brazil and on the scenario of the senses and purposes attributed to HS, based on internal contradictions and on the inside part of the debates about flexibility and quality inserted in the law that institutes the reform.

It is important to highlight that, in any of these productions, the centrality of the debate is circumscribed around the law or the set of legal limitations that led to the HS reform, to the impact of the expected transformations; and, from there, to this baseline in teaching, especially regarding curricular changes. But the debate about the effects on the teaching institution (HS) and its parties is not so much briefed. Our contribution aims at reaching this objective: to approach the HS reform based on the point of view of the effects that are possibly triggered by it on an important set of parties: the youngsters attending it.

PLACING THE ISSUE

The field of Education and, more specifically, the Sociology of Education, is used to approaching the issues surrounding the relationship between Education and Society, considering the teaching institution as a point of reference, as a place from where we observe. From this perspective, we investigate the school based on its agents, its practices and traditions, rituals, approaching it in its history, its relations with other institutions. We also investigate the youngsters and children who attend it (as subjects, as institutional parties) once they are, at the same time, object and objective of the educational and school action.

In 2003, Marilia Spósito, in the article “A non-academic perspective in the sociological analysis of the school”, recognizes the huge effort and the significant accomplishments that important authors in the field1 have been achieving since the 1950s regarding the knowledge about the school institution, its deadlocks, its parties, identifying emergences and ruptures. However, it also shows us that these studies have gaps. Therefore, in this sense, they provide, up to this day, “[…] suggestive paths capable of enriching the understanding about the school institution, especially in this moment that is characterized by a deep crisis in its socializing action.” (Spósito, 2003, p. 210, our translation).

Here, we do not intend to enter the debate about the socializing action of school and its crisis. Authors such as Dubet and Martucelli (1997), Lahire (2004), Thin (2006), and, in Brazil, Setton (2009) have been debating this matter at least since the 1990s, and Tomizaki, Silva and Carvalho-Silva (2016) has been analyzing political socialization. On the other hand, we want to assume other consequences from Spósito’s formulation.

If the relations between the forms of socialization become narrow, produce new sociability, then it is necessary to consider that the research about the school life in its non-school elements requires a denser knowledge of the subjects — in this case, adolescents and youngsters — that surpasses the limits of their lives inside the institution. This knowledge leads to the absorption of analytical and theoretical instruments of sociology in the stages of life — childhood and youth — and the relationships between generations. (Spósito, 2003, p. 222, our highlight)

To investigate the field of Education, built from the observation point of the youth, however, constitutes a specific activity. Because, for that, it is necessary to build a point of view based on these subjects.

The objective of this article is to carry out a first analysis with a new investigative approach for the field of Education, based on the construction of a point of view (Bourdieu, 2012). Therefore, in the first stage, we will build youth as a social position, however subjected to a significant variety of life conditions and ways of expression. In the second stage, we will try to demonstrate the analytical possibilities that come from such a perspective for the field of Education, through an exercise of analysis about the HS reform.

ELEMENTS OF THE DEBATE TO PRESENT YOUTH AS A POSITION

YOUTH AS A POSITION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PIERRE BOURDIEU

In the article “Class condition and class position”, Bourdieu (2009) shows that a social position is a social location, which delimits a set of properties (not only, but also — and maybe mostly — symbolic). From this place, connections are established with the broader system of social relations, and, at the same time, the sense of private social relations is built. Being in the same “abstract”, “on paper” social position (even if these constructions are necessary for the analysis) does not mean being immerse in the same set of situations and/or social conditions, according to the author.

To advance on the topic of distinguishing class position from class condition, Bourdieu (2009) will try to differentiate what is more or less permanent in terms of what relates to the analyzed relations, and, for that, he brings about the notion of structure. So, he asks: what can the structural approach do?; and he answers: the structural approach allows to capture transhistorical and transtructural features (we would say more permanent ones), through the systematic study of a particular case, which appear with few variations in all groups with equivalent positions.

The author leads us to conclude that, as expected, a social position accumulates permanent features. However, according to him, to escape from the abstract character of the definition of a position, it is not enough to only analyze it considering the transhistorical and transtructural elements that it gathers, once (as also teaches us Lefebvre (1991), in “Everyday life in the modern world”), societies are private products of specific historical and social formations, configuring, in its originality, their own relations and contradictions. Therefore, it is necessary to face, in the design of social positions, both the “permanent” and the “contingent” elements.2

Finally, for the French author, each social position corresponds to a significant and dynamic set of situations. Therefore, we can conclude that: a set of configurations corresponds to social positions. In this perception, it is necessary to distinguish social position (social location, which delimitates a set of properties), social condition (concrete conditions that lead the experiences of each position to vary), and situation3 (specific cases that are expressions of the relations between position and conditions).

How is the notion of social position configured for us based on Bourdieu’s text? Firstly, it is important to mention that Bourdieu, in this classic text, is trying to distinguish class condition from class position. He is distinguishing, temporarily, for purposes of analysis, the abstract idea of a general class position from the effective conditions of life in the social groups that have this position, showing that they vary. He demonstrates that the conditions of existence of social groups that have similar positions in different societies vary, and he shows that different social positions may hide similar life conditions in different societies.

We think this is a very interesting exercise, because it can be practiced when we think of youth. We have worked youth as a social position, one that is common to all of those who, in the scope of an extensive (variable) and intermediate (in-between stages of social life) age group go through, in capitalist, urban and western societies, the process of emancipation from institutions of circumscription to primary socialization, with simultaneous admission in the network/group/complex of institutions that integrate secondary socialization, leading to social insertion.

In this sense, youth is a social position, one that is simultaneously dynamic, tense, transitional, since it implies withdrawal (emancipation from the network of institutions that circumscribe primary socialization) towards a future process of social re-entry (in the network of institutions that delimitate secondary socialization). For us, this is what brings youth together (this state that is, at the same time, formative, initiating, transitional, aiming at the use of a present condition that configures a possible future insertion). In this sense, youth is a position in the social space.

This common data, however, is experienced in many variables and different manners. In Brazil, not only the conditions of exercise of youth are unequal, but the common position is experienced in absolutely divergent conditions, thus submitting the youngsters to situations of transition that are also very different. Therefore, only with a precise and rigorous design of cases it is possible to catch the inequalities and distances that mark the many ways to experience this common position.

YOUTH AS A POSITION FROM KARL MANNHEIM’S PERCEPTION

If for Bourdieu (2009) it was possible to mint the idea of youth being a position in the social space, for Mannheim (1968) we observe a relationship between youth and time. The author highlights that the common position of those who were born at the same chronological time is not only given by the possibility of experiencing the same facts or having similar experiences; but especially because they can process these facts or experiences in a similar manner.

Mannheim brings the idea of common position from a same chronological time and calls interior time an internal one, that is not measurable and can only be understood subjectively, from the qualitative perspective, and not from the objective point of view (Weller, 2005; 2010).

He highlights two perspectives from Dilthey’s line of thought and makes them reference to think about sociology of generations and the matter of time:

the contraposition between quantitative measurement and the exclusively qualitative understanding of interior experience time; and

the fact that it is not only the succession of a generation that anchors a deeper sense than the merely chronological one, but also the phenomenon of “contemporaneity” or “simultaneity”, that is, the sharing of a same “time”.

Therefore, Mannhein emphasizes the fact that different age groups experience different interior times in the same chronological period:

Each one lives with people of their own age and people of different ages in a variety of contemporary possibilities. For each one, the same time is a different time; as follows: a time that is different and belongs to the person, who only shares it with his/her contemporaries. (Mannhein, 1968, p. 517, our translation)

For Mannhein, the internal objectives — or “intimate goals” — shared by contemporaries of the same generation are called entelechies. So, Mannheim is dedicated to the study of common matters related to the “spirit of time” (Zeitgeist) — this entelechy — of a specific time, or even its deconstruction. This “spirit of time”, on the other hand, is formed by several generations that simultaneously work and interact in the social plan (Weller, 2010).

To sum up, the central categories in the “generation problem” brought by Mannheim are the idea of qualitative apprehension of time — contemporaneity of contemporaries — and “generational entelechy”. In this sense, this “contemporaneity of contemporaries”, or that common sharing of experiences, is revealed while the processing of experience takes place when the exercise of the juvenile condition and the juvenile experience happen in the objective reality.

THE SOCIOLOGICAL PROBLEM OF GENERATIONS AND THE MATTER OF TIME

For Mannheim (1968), youth would be characterized as a position in motion in time. To formulate that question, the author operates with three different concepts; however, they are related for us to think about the sociological problem of generations — generational unit, generational connection and, finally, generational position:

the generational unit would consist of less cohesive groups, of temporary character for a specific end;

the generational connection, however, may lead to the formation of a concrete group. Mannheim emphasizes it is a mere connection, that is, the individuals belong to it casually, but do not see themselves as a concrete group (Weller, 2010); and

the generational position — or generational situation — is the understanding that there is a biological rhythm, but that socioeconomic conditions constitute the common base of the subjects.

Mannheim highlights the fact that belonging to a generation may not be immediately inferred from the biological structures. On the contrary, the class situation and the generational situation would present, according to Weller (2005), similar aspects due to the specific position taken by the individuals in the social plan. But this position generates a specific modality of living and thinking, of the way the members interfere in the historical process, that is: “[...] an inherent tendency to each position that can only be determined based on the position itself” (Weller, 2010, p. 211, our translation).

Mannheim then reinforces the idea that it is not enough to have been born in the same period. What would characterize a common position of those born in the same chronological period is the potentiality or possibility of living the same events and facts (Weller, 2010), or going through similar experiences — living, in the moment in which they process their entrance in society, historical configurations that are similar in the flow of history —, but, above all, of processing these facts similarly, experienced as a founding experience.

Based on this formulation, it is possible to observe that this processing is given based on the categories that configure the experience of the subjects. The experiences, however, are shaped by life conditions, and, therefore, of (conditions of) elaboration and expression, diverse and unequal. So, categories such as class, gender, race, work, territory, age group — to mention a few — would work as reality perception filters. This specific processing of experiences brings the possibility of identifying the subjects and building their subjectivity.

Aiming at analyzing the perspectives of the two aforementioned authors, we drew a synthetic chart (Chart 1) that allows us to verify both propositions based on some common parameters. For that we will mention how, in the elaborations approached here, we extracted, from each of them, a definition of position, a notion of social relations, and a set of properties limited by the social position occupied by youth.

Chart 1 Bourdieu-Mannheim comparative.

| Bourdieu | Mannheim | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of position | Location in the social space that limits a set of material and symbolic properties. | Generational position — it is an effect of historical conditions. From that perspective, youngsters would be those who have founding experiences, interpreting them based on the present configurations — the attribute of the position is a specific type of experimentation in the flow of history. |

| Social relations | These are relations between conditions and social positions. | The relations are given in positions (in the flow of history) and conditions (both historical and social of elaboration of common facts). |

| A position limits a set of properties | In the distinction between class position and class condition, the author tries to differentiate what is more permanent than what is less permanent in the analysis of social relations. He concludes that, based on the analysis of properties of a single position, it is possible to distinguish (in the case studies, or in those he calls systematic studies of specific cases), more permanent elements from less permanent ones. Therefore, the common social positions (more stable) would correspond to variable social conditions (more contingent). For this author, therefore, the position accumulates a set of stable (little or non-variable) features (or properties) that present themselves for the investigation in interaction with what is variable: the social conditions, which can be apprehended based on situations (potential and infinitely variable effect of the syntheses between position and social conditions). Here, youth is the location in social space. |

For Mannheim, generation is the social and historical position (a young person is the one who reaches society from its margins). Youth is a “place” in time. For this author, what would be the properties of this position? Based on the assumptions of a qualitative understanding of time and that different age groups experience different “interior periods” in a same chronological period, Mannhein builds the thesis that the position in history constituted by youth generates a specific modality of living and thinking, a “tendency that is inherent to the position and can only be determined based on position” (Weller, 2010, p. 211). From that perspective, the youngsters would be those who elaborate founding experiences, based on the configuration of the present conditions. In this sense, it is subjected to a form of elaboration of facts, which is not unambiguous, but always singular, in relation to the other members of society. Here, youth is a position in time, singular experience in the flow of history. |

DEFINITION OF YOUTH BASED ON THE SYNTHESIS OF BOURDIEU AND MANNHEIM

Therefore, youth can be characterized, in western, urban, and contemporary societies, by a state of social liminality, marked, on the one hand, by the emancipation from primary socialization and entrance and experimentation of processes of secondary socialization, aiming at autonomy and integration in society.4 From this perspective, youth is a place, a position in social space. But, as Mannheim (1968) teaches us, this social position also owns interpretative potentialities, since by living in a specific period of time, the groups of subjects from the same generation also share a historical configuration that constitutes the base from which their founding experiences are built, essential element in their view of the world. From that perspective, youth is a location in the experimentation of the flow of history.

WHAT CAN THE “YOUTH POSITION” TOOL DO?

If a social position is a social location, then it is also a place of observation. A belvedere. Let’s continue with this reasoning: a location delimitates a set of properties, especially symbolic ones (that is, properties that belong to the real world of social relations), from which relationships are established with the broader system of social relations. In our case, assuming youth as a position of observation means building a place of observation from where social relations are seen. From where institutions, for instance, are seen.

The first consequence of building youth as a position of observation of society is that this is the place from where institutions will be seen, such as school, work, family, religion and churches, groups of pairs, among others. In this record, we consider it is possible and fruitful to follow the proposal formulated by Spósito (2003) and Spósito, Souza and Silva (2018)5, in the sense that getting to know the school, or even the Brazilian school system, also goes through knowing the subjects attending it, beyond the school walls, surpassing the limits of their lives in the institution. We would add: to capture the senses contained in what they express about the institutions, such as school, it is necessary to know the “social place” from where they speak. Their position.

This is a new approach about the institution. The proposal is that, based on the recreation of the social location of the youngsters, it will be possible to produce another perspective, one that is able to clarify the educational phenomenon. In this sense, we will try to understand, considering the juvenile position involves a series of institutions, the relative (and, in that case, specific) importance of school in relation to the other institutions and social agents involved in the exercise of youth.6

The second consequence of considering youth as a social location, from the designed perspective, is that, based on this social position, this location, the sense of private social relations is built. In other words, taking the place of vision, the position of youth means reconfiguring the function, the use, and the perception in general (or of the academic field) of institutions (including school).

Finally, adopting the social location of youth as a belvedere means understanding that it is also from this place that youth build the sense of private social relations in which it is involved. Therefore, understanding it presupposes the reconstruction of this place from where the world is seen, from where the facts are interpreted, from where meanings and functions are built for the institutions.

One consequence is yet to be mentioned. If youth is a social position; and if this position refers to a state of liminality, then it is not a fixed position, let alone a stable position, once one of the characteristics of the social group that embodies that position is that it is, itself, in a transit condition.

To sum up, considering youth as a position helps us to create a perspective and a way to approach the phenomena based on the definition of the concrete position, from where the subjects we wish to analyze experience society and its time, and build, from there, their points of view. Considering youth as a position (in space and time) creates, for the researcher, a place from where we will build our research issues, a space-time place where we will put our analyses.

From this perspective, we now present a path of application, of a use for this tool in the field of studies of youth. In the following section, we will work with the question: what can (in terms of analysis) the perspective of “youth as a position” do? For that, we will use elements of the debate about the transition between school and work to locate a way to approach youth; therefore, from this perspective, we will approach the impact of the HS reform on that group of Brazilian young people who were recently included in the Brazilian public educational system, and thus derailed by the reform.

AN ANALYSIS THAT GIVES “BODY” TO THE QUESTION: WHAT DO WE SEE WHEN WE CONSIDER YOUTH AS A POSITION?

As we have previously defended, when we consider youth as a place, position of observation and analysis of social relations, we change the perspective with which we approach and, therefore, understand the phenomena. The studies about transition into adulthood, basically coming from demography, help us place the issues referring to youngsters (of a given society), on the one hand, because they involve the social process through which the new generations promote their insertion in society. On the other hand, these studies take this “part” of society (young people) as a place, a position from which the reached effects can be measured, for example, by social policies.

According to Pimenta (2007), the first author to face the discussion about the transition into adulthood was Chamborendon (1966). In a first movement, defining and identifying the process, this author points out that transition allows that social roles be transferred, and responsibilities be assumed by other members of society; that a generation succeeds the other, without implying the absence of conflicts in the passage. It also indicates that the way this period is experienced may vary according to gender, social class, family, ethnicity, religion, and age group. It can also vary according to the historical moment.

Through the notion of transition, it is also possible to analyze the several and complex processes of insertion of individuals inside social groups, delimited by specific variables. After the founding studies of Chamborendon came the elaborations of Galland (1997), who was a disciple of the former and deepened his model; in the 1980s, he observed that the linear models of school-work transition were substantially modified. For this author, after that, transition began to extend in time. On the other hand, the synchrony of the stages of transition into adulthood was ruptured,7 at the same time shuffling and disconnecting events of transition processes, that used to be organized, into a phenomenon called “desynchronization of stages”.

Passage enlargement and desynchronization of stages were formulations that ended up allowing the focus of transition into adulthood as a “new stage of life”, more than as a “passing stage”. On the other hand, this focus allowed the facing of differences (not to say inequalities) that mark the experiences of young people in relation to different genders, races and social classes, the variety of possibilities that such insertions delimitate and the several and unequal modalities of transitions that such insertions determine.

Finally, the experience of the Grup de Recerca en Educació i Treball (GRET) of the Sociology department at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, conducting studies about the itineraries of social and professional insertion of Catalan young people, tried to build a new theoretical and methodological perspective from which a study of the social status of youngsters would be released, providing the bases for a sociology that would be more effectively centered in the transition into adulthood. One of its most important contributions lies on the observation that the transition studies allow us to realize the longing effects (and, in some cases, permanent effects) of social inequalities on the reproduction of generations.

The recovery of the notion of transition into adulthood allows to cast the changes through which the ways of studying have been, besides the juvenile routes towards adulthood, allowing the focus of events and institutions involved in the processes of transition in current days. For example, it allows us to translate the social problem experienced by Brazilian young people (especially those included in the broad spectrum of “popular classes”) in a relationship: the one established between the expansion of school into a moment of retraction and precariousness of work processes with the general processes experienced by subjects nowadays, of dischronologization and desynchronization of the stages in the transition into adulthood. Therefore, we make room to another question: which particular contours appear with the crossing of such processes for the analysis of the singularity of young people in Brazil?

If we understand that one of the most remarkable features of our society are economic, social, cultural and political inequalities to which we submit our population, and if we consider that, regarding youth, one of the central elements of these inequalities lie exactly on the huge differences that mark the processes of social insertion of its members, of its generations, we will realize that one of the ways to capture these disparities is centered in the understanding of how this group combines (or not) these two institutions: school and work.

Cardoso (2008) shows that the process of social insertion of most poor young people in Brazil had work as the institution of reference. Through the history of this country, huge groups of youngsters left school prematurely, without concluding the minimum standards of schooling, thus also entering the workplace early through family or close networks. Therefore, they tended to maintain a work life not only not so generous in terms of rights (economic, social and, therefore, political rights), but also circumscribed their social and economic conditions around the type of occupation that was characteristic of their first entry. At the same time, there was a limited share of youngsters in middle classes, with access to higher levels in the school system, who counted on these institutions as central and guiding elements of the processes of formation towards social insertion and work, therefore able to build, based on school, a working career.

The amplification of the right to school and the increasing permeability of school systems to larger shares of popular sectors, however, brought about important changes for transition processes, so that the school began to compete with work as the anchorage of processes of social insertion, even among young people from popular classes, thus allowing the emergence of a third form of relationship between school and work in the transition process.

This “intermediate” mode of school-work transition8 involves young people who, included in teaching systems (some in precarious conditions) through policies of expansion of schooling in the country, but still inserted in families with variable access to social rights, try to combine school and work. Therefore, a group that does not experience an insertion in the workplace that takes them out of school early, nor experiences the guarantees that allow them to attend the school system until its superior levels in order to search for insertion in the workplace just then. It is a group that combines school and work.

What we are saying here is that the expansion of schooling had an effect on the processes of youth transition, rupturing with the separate and different modes of social insertion of youngsters from middle and low classes in Brazil.

SCHOOL EXPANSION AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

First of all, it would be interesting to place, in a preliminary manner, what we will first call recent expansive cycle, delimiting it from the 1990s until the 2000s. According to Algebaile (2009), in this period, school expansion affected especially elementary school (ES), and, indirectly, HS. Based on school flow correction policies, whose goal was to adjust the available infrastructure leading to a more efficient service of the school population group, the goal was to reduce the levels of retention. In this context, the programs of “learning acceleration” were the way to measure a project that tried to create vacancies by the acceleration of processes, without, however, creating infrastructure.

It is possible to highlight some effects of such policies with this design, that are current in the country, between the second half of the 1990s until 2002: first, the flow correction policies did not change the selective character of education, as we will see ahead; the reduction in the frequency of failure, however, improved the flow of the systems, and secondarily reduced the value of failures — as observed in Pinheiro et al. (2018) —; together with the policies addressed to families and against child labor, the reduction in the number of failures also reduced school dropouts, and, therefore, as shown by Ferreira (2019), the long school dropout.9

Unlike what we call the first recent cycle of school expansion, this, which we call second cycle (and lasted from the second half of the first decade of the 2000s until 2016) came with the increase in the amount of resources destined to the several levels of teaching, with the increase in levels of teaching reached by the financing of some funds (Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and Improvement of Teaching — FUNDEF, in the Portuguese acronym — and Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and Improvement of Education Professionals — FUNDEB, in the Portuguese acronym),10 strongly anchored by the debate with society. The increase in investments in education also reached higher education11 and technical courses with the creation of a network of federal institutes addressed to the graduation of technicians and technologists. However, it maintained to the ES level12 the emphasis on policies of school flow correction, therefore accompanied by evaluation strategies that aimed, on the one hand, to measure, and on the other, to reduce school inequalities.

The fact is that school expansion, designed after the mid 1990s and redirected after the early 2000s, has had major effects on the schooling processes in Brazil, in all its levels and modalities. The logic of elimination of huge contingents of children and adolescents still in ES seemed to have been replaced by a more integrative one, but which incorporated school contingents after a varied degree of conditions, thus projecting varied and unequal paths of future schooling.

On the other hand, if the system expanded, it maintained the same selective logic with which it has operated over the years. Therefore, the data in the report of the Youngsters and Adults International Conference (CONFINTEA) already demonstrated, in 2008, that non-conclusion or dropouts were, and still are, the elements that generated a demand for education of youngsters and adults in the country when we talk about the young population (Brasil, 2009). The 2016 education census gave signs that updated the tendency that had been detected in the report (Brasil, 2016). According to the collected data, a considerable increase was observed in the age/grade distortion already in the 5th year of regular ES, showing that the path of students is irregular and discontinuous in the early schooling years. On the other end, the observation of age distribution of the students who attended Education for Youngsters and Adults (EJA, in the Portuguese acronym) showed that the early years were (and are) constituted by much older students than those who attend the final years of ES, and equally older than those who attend HS in the modality. There was also a tendency that a younger population would always enter in the final stages of ES in this modality.

Therefore, if the policies of schooling expansion in Brazil undeniably have increased educational opportunities, they did so with the maintenance of the systems’ selectivity, so that the increase in opportunities corresponded to the maintenance of educational margins, that are functional to the systems; the learning acceleration programs (especially in the basic levels of schooling), night school (especially HS) and EJA (in all levels) were its most common expressions. But what are the effects of this selective expansion on the levels of schooling of young people? Was selective expansion capable of affecting the unequal distribution of educational opportunities among youngsters in Brazil?

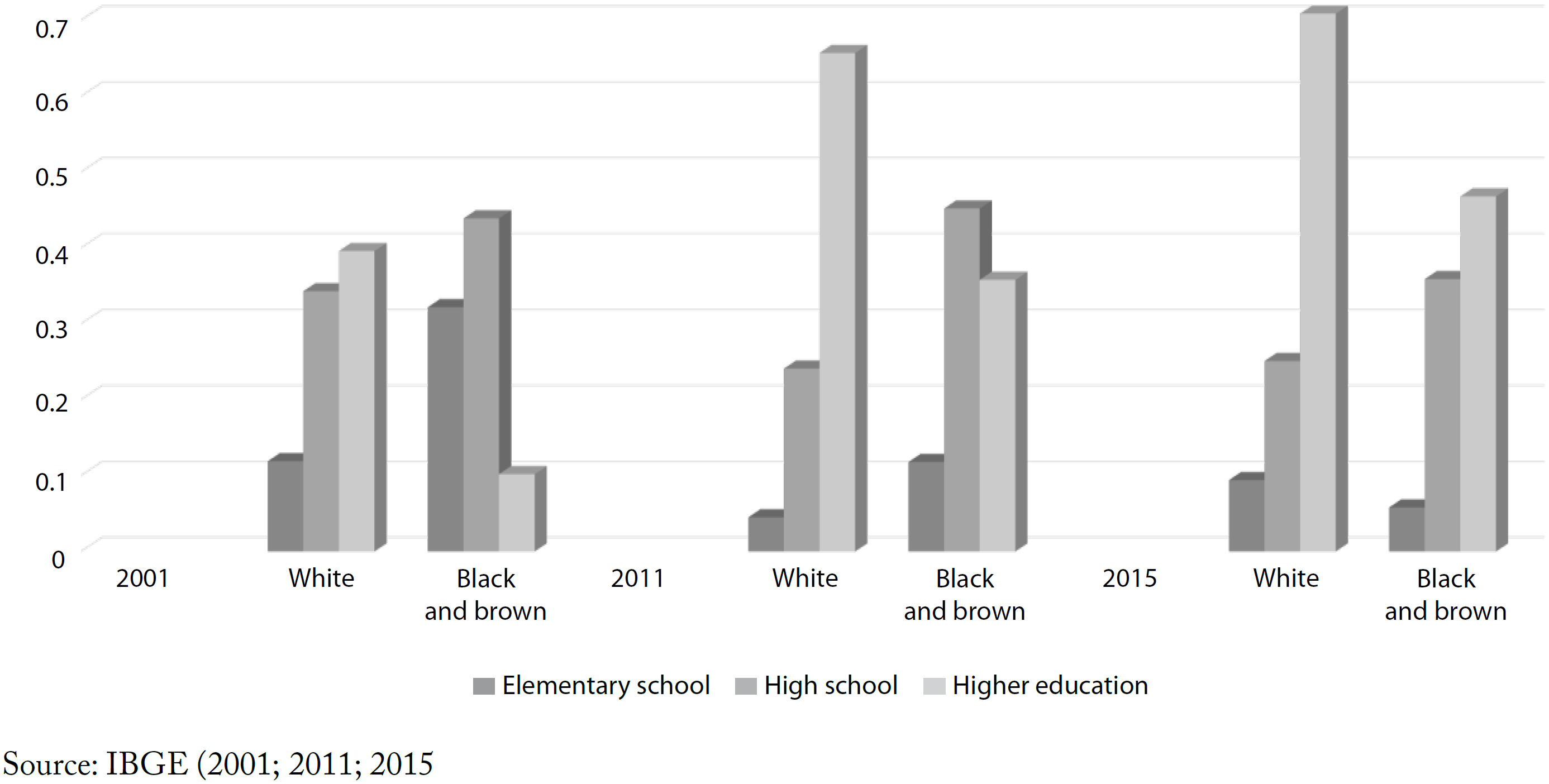

To demonstrate the growing importance of school in the lives of youngsters from popular classes in Brazil in the past 20 years, we will look at the data referring to the evolution in the distribution of white, black and brown young people in school levels (ES, HS and higher education) in 2001, 2011 and 2015.13 The object was the population aged between 18 and 24 years, because this young age group, in Brazil, is neither covered by mandatory education (which, including HS, includes the population aged up to 17 years), nor has completely consolidated its entrance in the Economically Active Population (EAP).

It is important to clarify that the population aged 18 to 24 years translates an interesting indicator, because even if only 30% of them were studying in 2015, and even if, in the set of this population, 18% were working in higher education,14 it expresses the results accumulated by the changes, limits and conquests of the schooling processes in ES and higher education. For this analysis, we used the data from the 2001, 2011 and 2015 National Household Sample Survey (PNAD, in the Portuguese acronyw — IBGE, 2002; 2012; 2016).

When we look at white students, observing Graph 1, we realize that the phenomenon to be noticed is that this group of students, over the years, had some oscillation; a percentage of 10% in enrollments in ES, increasing from 34% of enrollments in HS in 2001, until the stabilization of enrollments in 25% after 2011, using the extensive access to universities, extending the participation in this school level: from 39.6%, in 2001, to 65.7%, in 2011, and 71%, in 2015, almost doubling the importance of the participation of this teaching level among white students. Therefore, there was a change in the quantity of accesses of white students, aged 18 to 24 years, to higher education, but not a change in the access pattern (in this group, the distribution was, since 2001, proportionally lower in ES, and higher in higher education).

Source: IBGE (2001; 2011; 2015

Graph 1 Distribution of the population aged 18 to 24 years by school attendance according to color and race.

The case of black and brown students shows a very different scenario. This is because the pattern of distribution of students among the school levels changed significantly over the 14 years of this analysis. In 2001, the highest proportion of students in this group was first in HS (43.9%), then in ES (32.2%). Only 10% of the black and brown students were attending higher education in 2001. Ten years later, the scenario was very different: the percentage of enrollments is still prevalent in HS (45%), but the proportion of enrolled people in elementary and higher education is reversed. Higher education becomes the second level with the highest percentage of enrollments for black and brown students (35.8%), and ES becomes the less frequent one, with 11.8% of enrollments. 2015 shows a distribution of enrollments for this group of students in a quantitatively different pattern, but similar in quality (in terms of distribution of students per level) in relation to that found for white students. In it, we find 5.8% of black and brown students attending ES; 35.9%, HS; and the highest proportion of students (46.8%) attending higher education.

These data show us that if the expansion of the highest teaching levels affected white, black, and brown students at the same time, the process was not identical between them. If among white students the expansion of schooling was given by the increasing number of students in higher educational levels, among black and brown students this change was not only quantitative, but also qualitative. Among the latter, there was a change in the distribution patterns of youngsters in the different school levels: from a predominantly medium-elementary distribution, we reached, 14 years later, a predominantly higher-medium distribution.

HIGH SCHOOL AS A “DIVIDER LINE”

The increasing schooling took place in a scenario of maintenance of school selectivity. Ours is a very unequal school system, despite the significant advances of the past 25 years (especially in the last 15 years). The net rate of school attendance in 2016 (Brasil, 2016) was 91.4% from 6 to 10 years of age; 78% from 11 to 14 years of age; 59% from 15 to 17 years of age; and 18.4% from 18 to 24 years of age. This shows that restrictions in the access to medium and higher levels of schooling, and especially the selectivity that crosses the whole system, from elementary to higher education, going through HS, are still a significant problem.

It is always important to remember that the delimited age groups correspond to corresponding school levels, and that the net rate of schooling points to the contingent of students enrolled in the educational system, in the expected age group. Therefore, a decreasing net rate throughout the age groups corresponding to the advance in school levels indicates that the school system, while advancing, leaves a significant contingent of students along the way.

The data in the 2016 educational census (Brasil, 2016) bring signs that update the already detected tendency in the Preparatory Document for the VI CONFINTEA, of 2008. According to the data collected in the census, there was a considerable increase in the age/grade distortion in the 5th grade of ES, showing that the path of students is irregular in the early schooling years. On the other end, the observation of age distribution of the students who attended EJA showed that the early years are constituted by much older students than those who attend the final years of ES, and equally older than those who attend HS in the modality. There is also a tendency that a younger population would always enter in the final stages of ES in the modality.

To sum up, the expansion of schooling (in the 15 first years of this millennium) increased possibilities, changed tendencies, ruptured with major inequalities in Brazilian society; but taking place in the marks of a still significantly selective educational system, it all happened by creating and incorporating margins to the systems.

In those margins are the students who had been kept inside the teaching systems exactly because the system expanded. There are men and women, youngsters, belonging to minorities and/or ethnic diversities in the country, usually living in “territorial edges”, suburbs, slums, traditional communities, rural areas, with records of a broken school history, marked by interruptions, and by the frequent or occasional combination with work. This is exactly why these young people attending HS are mostly found in night school and/or in the EJA’s modality.

As we have been showing up to here, the expansion of school in all levels, even those considered as higher education, has changed historical inequalities, thus accelerating, in the past two decades, the emergence of a way of social insertion, especially for specific groups of popular classes who found, not only exclusively at work, but in the combination of varied ways of relationship between school and work, their anchorage.

Our hypothesis is that, with this emerging configuration, a possible new regime of transition between school and work for youngsters of popular classes was announced, and HS is a divider line. On the one hand, as Madeira (2006) teaches us, by the extension of time of youth. On the other, as Guimarães (2005) has shown us for some time, by the possibility of projection of a working career, based on this level.

Why does the clear change in level happen in the passage to high school? In literature there is no attempt to explain it, only its recurrent observation. The hypothesis is that this stage in the process of school progress is usually understood as a necessary bridge to reach the highest educational levels, and therefore works as an important stimulus in the amplification of the period of exploration of possibilities, in the field of romantic relationships and personal improvement. Only after crossing that bridge it is feasible to design plans and dedicate some time to search for a better future. (Madeira, 2006, p. 141, our translation)

But as shown by Guimarães (2005), there are important specificities when it comes to the entry of youngsters in the work market in Brazil. Here, we highlight some of them:

changes in the productive sphere that affected the work market dynamics, especially the base of the occupational pyramid, extinguishing the “beginner” jobs;

coexistence with another demographic wave parallel to the young wave, constituted by those who were, in the 1990s, at the top of their productive capacity; and

work market with little quality, underpaid opportunities, few guarantees, and long working hours.

In this scenario, young people reach transitions that are, at the same time, intense and prospective “for work”, characterizing a process of constant entry and exit of the work market, search for better conditions and more qualified jobs. This is very common among young people, both for those in low and middle classes.

This situation has some effects: unemployment among young people is three times higher than among adults. Even in periods of employment, there is more informality among poorer youngsters, among women and in the black population. It is true that the context in which schooling expands itself, and where the workplace insists on presenting itself as little permeable to young people, creates what Guimarães (2005) identified 15 years ago as a paradox: a social destiny expected by youngsters — a transition with full social insertion — confronting with the lack of opportunities for most part of new generations.

Therefore, the benefits produced by policies of expansion in HS were not exclusive for young people, the first target-audience. The product of this expansion is remarkably social and is constituted of:

increase in schooling years: which leads to benefits of higher access to health information, more chances of better jobs with better salaries, which, in the Brazilian context, means access to water and sewer, food, health, life infrastructure and life project;

career projection: configuring new nuances to the Brazilian work market, remarkably structured by low salaries and qualification; and

access to higher education: reconfiguring the career possibilities for beyond the technician level, building specialized manpower and expanding this population beyond the white population, thus leading to access of black and brown people, as presented in the previous section.

Resuming the argument: in the basic education networks, the margins, which were then eliminated from school banks, are composed exactly by those who, throughout their school lives, especially the final years, combine school and work trying to overcome the “HS barrier”, aiming at instrumentalizing a possible construction of a labor career. Those who are engaged in the emerging ways of “transiting” towards adulthood without the exclusive anchorage in school (as still happens for the upper middle class, with long schooling and no interruptions, ending up in university graduation and certification aiming at entering the workplace), nor counting exclusively on family networks to enter the workplace in an unsafe, underpaid job, with no expectations for a career.

THE HIGH SCHOOL REFORM

The reform came without having been debated with society, and followed by a coup d’état that removed from power a government that had been democratically chosen, replacing it with an elitist and unpopular project of power that ended a growing process of expansion in educational possibilities, which began in the Constitution of 1988 and established some of its most important marks in the creation of the education maintenance funds (FUNDEF and FUNDEB), in the increasing educational obligatoriness and in the policies of expansion and democratization of access to universities.

As announced in the beginning of this article, much has been said about the HS reform. Ferreti and Silva (2017), Frigotto and Motta (2017), Leão (2018), Silva (2018), Ferreti (2018) and Corti (2019), among others, have been working to translate the reform by questioning its bases, purposes, and intentions.

Besides the debate placing the theme, there is some consensus among the group of authors that approach the reform. It progressively increases the daily workload in HS to 1,400 hours/year (7 hours/day), going to at least 1,000 hours/year (5 hours/day) in a five-year deadline, but there is silence about the origin of the resources that will support this expansion, leaving the question about what will happen to night HS unanswered. Besides, the reform does not include the EJA/HS, elementary education modality belonging to this teaching level.

The most analyzed aspect of the reform has been the institution of the five formative itineraries (Languages and their technologies, Mathematics and its technologies, Sciences of nature and its technologies, Applied human and social sciences, and Technical and Professional formation), and the main critics involve the appeal inserted in the government propaganda at the time, which led people to believe that the itineraries would be possibilities open for the choice of the students, when actually what happened was the circumscription and limitation of itineraries according to the choices and/or possibilities of state administrations. Even if the matter is extremely important, what matters in this paper is exactly what the reform invalidates: the situation of night HS and EJA/HS, not included in the text.

An analysis of the 2016 school census shows us the size of the population excluded from the reform debates and text: the students in night HS and those enrolled in the EJA (Brasil, 2016). 30% of the students enrolled in regular HS attend the night shift. When we add those enrolled in EJA/HS, we comprise 40% of the students in HS, in 2016.

From that perspective, therefore, the HS reform eliminates (by invisibility, silencing) exactly the most socially vulnerable ones; those who probably concentrate irregular and discontinuous school paths; those who, after the virtuous cycle of school expansions, initiated in the late 1990s and renewed and expanded after the early 2000s, were able to stay in the educational system, trying to overcome the “divider line of HS”; those who tried to combine school and work; finally, those who tried to migrate to the emerging modes of school-work transition, configured with increasing strength after the Constitution of 1988.

CONCLUSION

In this text, we intended to prepare the land for the field of youth with the concept of youth as a position and its operation in a particular case: the HS reform. For that, we divided the text in two parts: the construction of the tool and its operation. In the first part, we analyzed Bourdieu and Mannheim to discuss major aspects in the analysis of youth and the study of positions, leading to the construction of a concept of youth supported by the idea of position and youth itself as a position. In the second part of the text, we presented practical matters of the juvenile reality in the Brazilian context based on specific parts of the PNAD according to age groups. Also, we used the tool with reflections about what could youth do — in the analytical sense of the term — as a position when observing a specific case: the HS reform.

Of this first approximation, we could draw the following main conclusions: considering youngsters as a position of observation leads us to replace the vision we have about social policies, and especially makes us see the limits of its operationalization in sectors (education and work, for instance); the studies of transition into adulthood (that impel us to capture the interactions between sectors instead of looking at them separately), among which we place the school-work transition, help us to look at that perspective regarding young people, that is, the one in which institutions and policies that make them dynamic can be observed from a closer (and broader) place from that where the juvenile experience is placed; also, in this sense, observing the onset of new configurations in the models of transition into adulthood in Brazil, based on the expansion of school systems, especially in the medium-higher levels, helps us to understand some of the most important impasses faced by youth today:

the productivity, but also the limits, of expansion of school opportunities in a scenario in which this educational growth and obligatoriness take place in a context of maintenance in school selectivity, leading to a process in which the increasing school opportunities do not eliminate the creation of school margins that are internal to the system;

in the scenario of selective expansion of school opportunities, we see a new social juvenile matter emerge, whose paradox consists of the expansion of formative horizons, with the construction of an expectation of careers in confrontation with a tough workplace, one that is unregulated and precarious in terms of rights;

we all see new margins appear in educational systems. They are in the educational systems thanks to the policies of school flow correction, and recognized by the policies of expansion in the obligatoriness of the right to education and the policies of expansion and democratization of the access to higher education; these margins, composed of students in situations of vulnerability (economic, social, and educational) live in the suburbs of society, attending night school and combining school and work; and

the point from which the new tendency (of combination of school and work, simultaneously or not, aiming at the construction of a labor career) becomes possible: the divider line of HS.

To sum up, we came here defending the possibilities opened by the consideration of youth as a position of observation of society. In the set of our arguments, we defend that this position finds its properties, on the one hand, in the urgent character of social insertion of youngsters in western capitalist societies; and on the other hand, in the singular experimentation of historical configurations that mark the succession of generations. In the scope of this argument, we also understand that the processes of social insertion of young people are subjected to “properties” coming from more permanent structural positions and processes of more contingent design, and that it is in the relationship between more solid positions and more contingent conditions that the social situations we investigate are consolidated. In this sense, understanding the ways with which public policies affect significant sets of youngsters in Brazil can be a fruitful way to test the hypothesis of our youth position as a strategic place of social observation, beyond a mere category of analysis, but as a belvedere that visualizes and re-signifies the social phenomena seen from other points of observation.

Finally, our proposal to bring a tool — youth as a position — and work with this tool based on the access and permanence of HS for young people aged 18 to 24 years, as well as the possible effects of the HS reform, shows that new points of observation create new possibilities to observe the social phenomena, and that the fact of highlighting the use of the “youth as a position” instrument shows us how much the HS reform is not only a “stopgap”, but a delay that has more expression and emphasis as a social regression — of the entire Brazilian society — than a policy of starvation only in the field of Education.

1In the article, Spósito (2003) especially approaches the authors that composed the “school of USP”, who, treating education as an important part of the disputes for development projects for the country, carried out investigations and analysis of the educational phenomenon based on this reality, configuring a current of thought that, based on authors such as Florestan Fernandes and Antonio Cândido, brought to light central researchers in the debate about the relationship between Education and Society, such as Marialice Foracchi, Luiz Pereira and João Baptista Borges Pereira — later followed by contemporary authors who, in the 1980s, disseminated this approach, such as Spósito herself, Maria Malta Campos and Rogério Cunha Campos.

2Which means that social positions should be studied based on specific cases. So, depending on the approach we make, we can identify the level, the reach and the stability of the elements involved in its composition.

3About situation: this would actually be the one to be studied with more materiality from the routine.

4This state of social liminality can be experienced, by different and unequal groups of youngsters, in very different manners, depending on the level and more or less equanimous distribution of social investments, resulting in very different processes of integration and autonomy.

5In a text from 2018 about a quantitative approach in the study about youngsters, Spósito, Souza and Silva (2018) presented the resumption of the argument of getting to know the young person outside the school environment.

6Leaving from a place of observation of youngsters, the school’s importance is related to the place it occupies in relation to other institutions and agents.

7As stages of transitions there are the succession between the condition of student and the condition of worker, considering the school system as an increased form of preparation for the career and productive insertion. The transition events are basically the demarcation of autonomy regarding the family nucleus, with the foundation of a new nucleus. The observation of Galland, in the 1980s, was exactly about the shuffling between stages and events, which used to be more organized and successive.

8Which is not the “classic” model among young people from popular classes in Brazil, marked by the early dropout of school aiming at entering the workplace with no rights, no guarantees and no career, and where, therefore, work and school work as excluding institutions, that is, it is either “school” or “work”; nor is it the most common model among young people in middle classes, in which schooling points at university studies, succeeded by the search for a working career, and at a job with rights and guarantees, that is, first school and, then, work.

9Ferreira (2019) understands as long school dropout the prolonged and sustained period of school absence coming from the student. Suspensions of weeks or a few months are seen as a type of fluctuation between comings and goings, which is not configured as school dropout.

10FUNDEB started financing children’s education, high school, besides elementary school, and reached education for youngsters and adults.

11With policies to increase vacancies (Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais — REUNI — e Programa Universidade para Todos — PROUNI) and of democratization of the access to university for groups historically excluded from it, through quota policies.

12And, in some cases, like in Rio de Janeiro, with the Autonomy program, from the State government, for the acceleration of studies to the high school level.

132015 was the final year of our analysis, once this was the last year when the parameters established by the 1988 Constitution were current; it was ruptured in 2016, with a coup d’etat.

14Still, it is important to clarify that even in this apparently modest scenario, significant advances have been made, given that, for the population aged 18 to 24 years old, there was a gross schooling rate of 18.6% and a net of 12.3% in 2004.

REFERENCES

ALGEBAILE, E. B. Escola pública e pobreza no Brasil: a ampliação para menos. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, 2009. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. A economia das trocas simbólicas. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2009. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. (coord). A Miséria do mundo. 9. ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Editora Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade. Documento Nacional Preparatório à VI Conferência Internacional de Educação de Adultos (VI CONFINTEA) / Ministério da Educação (MEC). Brasília: MEC; Goiânia: FUNAPE/UFG, 2009. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=10024-confitea-6-secadi&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 7 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (INEP). Censo da Educação Básica 2016: Resumo técnico. Brasília: INEP, 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.415, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Brasília: Presidência da República, 2017. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, A. Transições da escola para o trabalho no Brasil: persistência da desigualdade e frustração de expectativas. Dados, Rio de Janeiro, v. 51, n. 3, p. 569-616, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0011-52582008000300002 [ Links ]

CHAMBORENDON, J.-C. La societé Française et sa jeunesse. In: DARRAS, P. (dir.). Le partage des bénéfices: Expansion et inégalités en France. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1966. p. 157-175. [ Links ]

CORTI, A. P. Política e significantes vazios: uma análise da reforma do Ensino Médio de 2017. Educação em Revista, v. 35, p. 1-20, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698201060 [ Links ]

DUBET, F.; MARTUCELLI, D. A socialização e a formação escolar. Lua Nova: Revista de cultura e política, São Paulo, n. 40-41, p. 241-266, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-64451997000200011 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, M. D. P. Efeitos das políticas de correção de fluxo sobre as gerações escolares que frequentam o Ensino Médio na modalidade de Jovens e Adultos no Rio de Janeiro. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, v. 16, n. 46, p. 372-403, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5935/2238-1279.20190112 [ Links ]

FERRETTI, C. J. A reforma do Ensino Médio e sua questionável concepção de qualidade da educação. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 32, n. 93, p. 25-42, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-4014.20180028 [ Links ]

FERRETI, C. J.; SILVA, M. R. Reforma do Ensino Médio no contexto da medida provisória 746/2016: estado, currículo e disputas por hegemonia. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 385-404, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302017176607 [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, G.; MOTTA, V. C. Por que a urgência da reforma do ensino médio? Medida Provisória nº 746/2016 (lei nº 13.415/2017). Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 355-372, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302017176606 [ Links ]

GALLAND, O. Sociologie de la jeneusse. Paris: Armand-Colin, 1997. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, N. A. Trabalho: uma categoria-chave no imaginário juvenil. In: ABRAMO, H. W.; BRANCO, P. P. M. Retratos da juventude brasileira: análises de uma pesquisa nacional, São Paulo: Editora Fundação Perseu Abramo/Instituto Cidadania, 2005. p. 149-174. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: síntese de indicadores 2001. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2002. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: síntese de indicadores 2011. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2012. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: síntese de indicadores 2015. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2016. [ Links ]

LAHIRE, B. Retratos sociológicos: disposições e variações individuais. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, Henri. A vida cotidiana no mundo moderno. Trad.: Alcides João de Barros. São Paulo: Ática, 1991. [ Links ]

LEÃO, G. O que os jovens podem esperar da reforma do ensino médio brasileiro?. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 34, p. 1-23, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698177494 [ Links ]

MADEIRA, F. R. Educação e desigualdade no tempo de juventude. In: CAMARANO, A. A. (org.). Transição para a vida adulta ou vida adulta em transição. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA, 2006. p. 139-170. [ Links ]

MANNHEIM, K. O Problema da Juventude na Sociedade Moderna. In: BRITO, S. Sociologia da Juventude I. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1968. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, M. M. Ser jovem e ser adulto: identidades, representações e trajetórias. 2007. 463 f. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia) — Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

PINHEIRO, D.; RIBEIRO, E.; PEREGRINO, M.; SUSSEKIND, L. School and work: elements to discuss youth in Brazil. Sociology International Journal, v. 2, n. 5, p. 349-353, 2018. https://doi.org/10.15406/sij.2018.02.00068 [ Links ]

SETTON, M. G. J. A socialização como fato social total: notas introdutórias sobre a teoria do habitus. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 14, n. 41, p. 296-307, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782009000200008 [ Links ]

SILVA, M. R. A BNCC da reforma do ensino médio: o resgate de um empoeirado discurso. Educação em Revista, v. 34, p. 1-15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698214130 [ Links ]

SPÓSITO, M. P. Uma perspectiva não escolar no estudo sociológico da escola. Revista USP, São Paulo, n. 57, p. 210-226, 2003. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9036.v0i57p210-226 [ Links ]

SPÓSITO, M. P.; SOUZA, R.; SILVA, F. A. A pesquisa sobre jovens no Brasil: traçando novos desafios a partir de dados quantitativos. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, p. 1-24, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634201712170308 [ Links ]

THIN, D. Para uma análise das relações entre famílias populares e escola: confrontação entre lógicas socializadoras. Trad.: Anna Carolina da Matta Machado. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 11, n. 32, p. 211-225, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782006000200002 [ Links ]

TOMIZAKI, K.; SILVA, M. G. V.; CARVALHO-SILVA, H. H. Socialização Política. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 37, n. 137, p. 929-934, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302016171151 [ Links ]

WELLER, W. A contribuição de Karl Mannheim para a pesquisa qualitativa: aspectos teóricos e metodológicos. Sociologias, Porto Alegre, n. 13, p. 260-300, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222005000100011 [ Links ]

WELLER, W. A atualidade do conceito de gerações de Karl Mannheim. Revista Sociedade e Estado, Brasília, v. 25, n. 2, p. 205-224, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69922010000200004 [ Links ]

Received: March 08, 2021; Accepted: July 15, 2022

text in

text in