Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.28 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub Sep 06, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782023280087

Article

Analysis of the Movement of Senses in Education research

IUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil.

IIInstituto Federal Farroupilha, Santo Augusto, RS, Brazil.

The Analysis of the Movement of Senses is described as a theoretical and methodological fundamentals for research in education. Initially, the context and the bases are described, to subsequently describe procedures and phases of application of Analysis of the Movement of Senses . In this path, the dialectic perspective, the notions of movement and meaning, always in relation to discourse, are highlighted. For the elaboration of the text, as a kind of metalanguage, the Analysis of the Movement of Senses was applied, producing data through bibliographic research and systematizing them in the meanings that compose the arguments. As every sense is always in motion, the final considerations reiterate the need to understand that, in research in education, there is no absolute end, but a continuous movement of meanings and renewed demands for study.

KEYWORDS Analysis of the Movements of Senses; Education research; speech; senses

Descreve-se a Análise dos Movimentos de Sentidos, como fundamento teórico-metodológico para a pesquisa em Educação. Inicialmente, são apresentados o contexto e as bases, para, na sequência, descrever procedimentos e fases de aplicação da Análise dos Movimentos de Sentidos . Nesse percurso, põe-se em relevo a perspectiva dialética, as noções de movimento e sentido, sempre em relação ao discurso. Para elaboração do texto, como uma espécie de metalinguagem, aplicou-se a Análise dos Movimentos de Sentidos, produzindo dados por meio da pesquisa bibliográfica e sistematizando-os nos sentidos que compõem os argumentos. Como todo sentido está sempre em movimento, as considerações finais reiteram a necessidade de se entender que não há, na pesquisa em Educação, um fim absoluto, mas um contínuo movimentar-se de sentidos e renovadas demandas de estudo.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Análise dos Movimentos de Sentidos; pesquisa em Educação; discursos; sentidos

El Análisis de los Movimientos de los Sentidos se describe como un fundamento teórico-metodológico para la investigación en educación. Inicialmente, se describen el contexto y las bases, con el fin de describir los procedimientos y fases de aplicación del Análisis de los Movimientos de los Sentidos. En este camino se destaca la perspectiva dialéctica, las nociones de movimiento y significado siempre con relación al discurso. Para la elaboración del texto, como una especie de metalenguaje, se aplicó el Análisis de Movimientos de Sentido, produciendo datos a través de la investigación bibliográfica y sistematizándolos en los sentidos que componen los argumentos. Como todo sentido está siempre en movimiento, las consideraciones finales reiteran la necesidad de entender que no hay un fin absoluto en la investigación en educación, sino un movimiento continuo de significados y renovadas demandas de estudio.

PALAVRAS CLAVE Análisis de los Movimientos de los Sentidos; investigación en Educación; discurso; sentidos

Times change

Times change, wills change,

one changes one's being, one changes one's confidence;

the whole world is made up of change,

always taking on new qualities. […]

Camões (1992, our translation)

Being in transformation, reality changing and life following its challenges. Thus, existence is produced, which, from the perspective of dialectics, is in motion and in a permanent process of overcoming, as a becoming. These changes, impregnated by contradictions, by denial and renewal of the qualities that govern the orchestra of life, are limited to the movements that are processed in the existence of the human being, producing history. Orchestra, because it is understood that, at the same time that the human being lives as a “free” subject, guided by the charm of the melody, there are social rules that need to be followed, like a score.

In this context, as a historical-social subject, creator of reality (Cury, 1986), the human being (re)produces and conducts his existence under adverse conditions, with political, social, and ideological clashes. That's because, “[…] in the social production of their own existence, men enter into determined, necessary relations, independent of their will; […]” (Marx, 2008, p. 49, our translation). In this reality, the choices about the way of living, thinking, acting, in short, of being and of being in the world do not occur randomly, neutrally and from only individual wills.

The dominant discourse1 omits, denies the exploitation of one class over another, the antagonisms of classes and asserts itself “[…] supposedly universal, egalitarian, and therefore falsely identical and homogeneous.” (Cury, 1986, p. 47, our translation). Based on pseudo-concreteness2 (Kosik, 1976), the ruling class, which owns the means of production, establishes its conceptions of reality as finished and immutable truths. The reified3 world is expressed under deceptive appearances, with prejudices, such as fetishized praxis4 (ibidem), in which immediate phenomena5 and evidence penetrate the consciousness of individuals. The overcoming of pseudo-concreteness is processed from the revolutionary critique of praxis, explained by this Czech philosopher (1926–2003), highlighting the following argument: “In order for the world to be explained ‘critically’, it is necessary that the explanation itself be placed on the terrain of ‘revolutionary praxis’.”(ibidem, p. 22, our translation).

In this sense, the process of overcoming pseudo-concreteness encompasses education, both in the formal and informal spheres. It is, education, “[…] a very broad field6 and is characterized by its intrinsic relationship with the other fields of human life: the social and, therefore, cultural, the economic, the political.” (Ferreira, 2017, p. 19, our translation). In this way, the author continues, education “[…] is susceptible to any social movements.” (ibidem, p. 19, our translation). In this relationship, different interferences of these distinct fields of social life bring about changes, and education triggers modifications, therefore, they are articulated and influenced in an immanent way. The movement of reality is processed, in which all phenomena are interrelated with implications between one and the other, in a spiral.

The dialectical movement of thinking, of perceiving the peculiarities and of understanding the phenomena of reality and, as a result, apprehending and elucidating its “multiple determinations”7 (Marx, 2008, p. 260) and, intrinsically, interfering in it, converges to the need to understand the category8 “totality”. To this end, it is considered, with Hungaro (2014, p. 19, emphasis added, our translation), the apprehension of reality in its entirety and it is emphasized: “[…] this same reality is understood as a processuality, as a movement, in short, as coming to be that carries in itself elements of overcoming and continuity.”. Being thus constituted, it means that,

The totality is in concrete reality, and the researcher can reproduce it ideally. It is not about knowing the various aspects (factors) that make up reality and then adding them up. It is about realizing that reality is in itself totality and it is possible for us to apprehend the articulating logic of this reality. Thought does not put logic into reality, the movement is just the opposite. (Hungaro, 2014, p. 66, our translation)

Based on this immanent relationship between reality and totality equivalent to a structured, dialectical whole, in which facts can be rationally understood, as knowledge of reality and the parts are the structural elements of the whole (Kosik, 1976), it aims to understand the movements of the phenomena of the real, in different times and contexts. Totality, as a structuring axis, allows the problematization of reality with its numerous challenges, the historical genesis of its formation process, the limits generated by class antagonisms and the possibilities of overcoming by revolutionary praxis.9

In this way, immersed and oriented education is understood under the pillars of capital, as an uncontrollable system, that is, “[…] as a mode of sociometabolic control and system of social reproduction.” (Mészáros, 2011, p. 96, our translation). And, in view of the changes caused by the innumerable determinations of capital, it was felt the need to review the perspective of study and research10 in Education, aiming to carry it out based on the dialectic and based on the discourse, with its movements of meanings being the centrality. In addition, it is known the importance of subsidizing a proposal for study and research in Education with the fruitful categories: “totality”, “contradiction” and “historicity” (Cury, 1986; Netto, 2011; Lukács, 2013), therefore, the need to articulate them to the concepts of “movements”, “discourses” and “senses”. These, interpreted and exposed the arguments, become categories. This is justified by the understanding that “[…] the categories must correspond to the concrete conditions of each time and place. They are not something defined once and for all and do not have an end in themselves.” (Cury, 1986, p. 21, our translation).

Having presented these prolegomenes, necessary to understand how this article was articulated, it is also worth clarifying how the writing systematizes the group studies, aiming to describe the Analysis of the Movements of Senses (AMS), its conceptual characteristics, as a theoretical-methodological foundation for research in Education (which will be presented in the next section). To this end, the conceptual and operational aspects in the analysis of movements and in the conception of meanings (described in the third section of the text) are presented. The following are final considerations, reiterating the main aspects dealt with in the text.

ANALYSIS OF THE MOVEMENTS OF SENSES: A GENERAL DESCRIPTION

This article discusses the elaboration of the AMS as a theoretical-methodological11 foundation. For the subjects involved in this study and research proposal, movements, discourses and meanings emerge as categories, given the complexity and the broad perspective of analysis of the phenomena of the social field, especially those related to education. From the need to highlight the context of production of research data, in which it is possible to relate it to the fabric of the facts, this process began. This is because research also tends to make explicit the existing movement and the meanings produced, these being articulated and, in addition, potentiating the discursive materiality influenced by the medium, but not determinant. In this process, the comparison between the fundamental movements of the totality of the subjects occurs in the division of circumstances and situations in which they are produced.

It should be noted that, in the AMS, the theory presents itself in constant reevaluation and recreation, both in the scope of the method and in the denomination. In this sense, densifying studies related to the theme makes it possible to contribute with subsidies for researchers who intend to investigate in the educational field, without opposing the scientific methodologies already consolidated in research in Education, but indicating an alternative.

It is worth mentioning that the development of the AMS arises from the need for students and researchers of the Kairós Research Group, with a view to research in Education, to coherently elaborate an approximation and consonance between the theoretical and methodological contributions. It was based on the perception of the research itself and the procedures chosen in the group. It was decided, to bring these contributions closer together, to elaborate a theoretical-methodological foundation, one and the other together, allies, according to the culture of research in the area of Education. To approach it, initially, more than a methodological description itself, it is necessary to understand the definitions of the terms approach,12method,13technique,14 and methodology15. The purpose of distinguishing them becomes essential to advance in this argumentation, because, starting from these distinctions, it is intended to assume, even if momentarily, as a founding part of the AMS, the perspective that has been studied: theoretical-methodological foundation.

That said, in addition to explaining the recurrent terms in research methodologies, understanding them in their production context is important to delimit where they come from. In this sense, it is noteworthy that, in the elaboration of this section of the text, four thematic blocks, interconnected and interdependent, were organized to facilitate the distinction of each term: approach, method, technique, and methodology. The choice of “[…] Organization is hierarchical. The reason for this organization is that the techniques perform a method that is consistent with an approach.” (Anthony, 1963, p. 63-67, highlights in the original, our translation). The need to distinguish the terms is due to the fact that we find them in academic texts relativized as synonyms or similar. Disagreeing with this similarity, it is believed that it becomes relevant to understand and distinguish them, since, as an essential part of the research method, they constitute the subsidies for the investigation.

It proceeds with the explanations of the terms presented according to their etymology. Initially, the word approach, designated as a feminine noun, of French origin abordage, is contemplated. The term approach “[…] appears in the literature, after studies in the areas of structuralist linguistics and behavioral psychology […]” (Borges, 2010, p. 398, our translation).

The method, in turn, is characterized by not prescribing, considering the specificities and particularities of each study and research, allowing autonomy of choice to researchers. Already, in relation to the word methodology is composed of méthodos, formed by two words — meta: “[…] something that is beyond, ahead or at the end, in the intention that it be achieved.” (Souza, 2009, n. p., our translation) and hodos (passage or path) — plus the suffix logia. In short, methodology is “[…] the organization and planning of a passage in relation to the study, practice and/or conclusion of a theme.” (Veschi, 2019, n. p., our translation).

When resorting to the meanings of the terms in the dictionary sense, it is observed that some have certain similarities, and, due to this, conceptual mistakes may occur, which allows us to question: which term is more appropriate or with greater semantic proximity, for the description of what the AMS is? As an answer to this question, it is considered that movements — meanings — discourses are the basic categories for research in Education. That said, in this process, the consensus was reached that the mentioned terms do not currently measure such a study. As a result, it was decided that the terminology for distinction and general characterization of AMS, consistent with what is proposed, would be a theoretical-methodological foundation.

Here it is worth mentioning that the productions of Liliana Soares Ferreira and researchers from Kairós, on AMS, intensified from the year 2018. The materials published during these four years address the AMS as a technique (Ferreira, Braido, and De Toni, 2020), analytical approach (Ferreira et al., 2019), theoretical approach (Rodrigues and Ferreira, 2020), research (Ferreira, Braido, and De Toni, 2020), and theoretical-methodological contributions (Siqueira, 2020). Because it is a study in production, constant evaluation and deepening of the categories and concepts that densify the different elaborations, such as scientific articles, monographs, course conclusion work (TCC), dissertations and theses, the AMS is a technique, in a significant part of these productions: Ferreira et al. (2019); Ferreira (2020); Rodrigues and Ferreira (2020) because, until then, the conception of technique approached the demands arising from the research objects. However, with the thematic expansion, it was observed the need to seek a terminology that could contemplate other different possibilities for the conceptual description, which is the theoretical-methodological foundation.

By what theoretical-methodological basis? It is justified on the basis of the meaning of the term foundation, with the following definition: “[…] the gathering of knowledge or that which sustains a theory, a system, a religion.”.16 In this sense, this terminology seems promising to distinguish the AMS, differentiating it from, for example, course or theoretical-methodological assumptions, recurrent in scientific language, to describe how the research was or will be carried out. When reviewing the explanation of the route (space traveled), assumptions (what comes before), to understand the meaning of these, it was questioned whether, in fact, they would be adequate or not, regardless of the context or the situations under investigation. When we did not find conclusive answers consistent with the subject in question, it was reiterated that the expression theoretical-methodological foundation is more appropriate, due to its meaning, as a reference scope to designate the AMS. It is affirmed, therefore, that it is intended to develop the theoretical-methodological foundation of research to be applied, especially in research in Education. This is because it is a proposal of dialectical basis, which aims to study, considering the social totality, in an investigative process that moves from the particular to the general and from this to the specific, analyzing, at all times, the meanings evidenced in relation to the phenomena.

It is reiterated that, in the AMS, movement is understood as a condition that gives rise to the senses, that is, for a sense to be produced there will be a movement. As an example, because it is a proposal for study and research in Education, the different phenomena that are part of this social field are analyzed: educational policies, government policies, organization of workers in education via unions, precariousness of labor relations, among others. These phenomena change according to the movements of reality and, in the case of Brazilian society, formed by the capitalist mode of organization of economic and social reproduction (Mészáros, 2008), capital dominates and reproduces. The multiple determinations of the social reproduction of capital define and direct policies in their different spheres. In fact, there are contradictions in the scope of discourses on education, from intentions in the school context, as well as informal. This is because reality in its totality is dynamic, changeable, produced by the human being. The reality is “[…] historicized, to be considered as a product of human praxis, since the historical world is the world of the processes of this praxis.” (Cury, 1986, p. 25, our translation).

As a result, for human beings, movement is the process of thought, in which, initially, the object of research is chaotic and, in the process, with the theoretical appropriation, built with criticism, interpretation and evaluation of the facts (Kosik, 1976), abstraction is realized. From the concrete to the abstract, Kosik (1976) defines it as the movement in thought and thought, therefore, is a movement that articulates concepts, as an element of abstraction. In this movement, the human being creates meanings for himself, “These same senses, through which man discovers reality and the meaning of it, thing, are a historical-social product.” (ibidem, p. 29, our translation).

Already, in the perspective of the natural sciences, specifically in Physics, which makes it possible to know various types of movements, there is another and complementary conceptual description of movement. The basic and popularly known is one-dimensional rectilinear motion, which determines the displacement in a straight line from a point A to a point B. What defines the existence or not of a movement is the variation of space between a body and a reference frame over time (Halliday, Resnick, and Walker, 2012). In other words, one has to take a point of reference in relation to what is analyzed as a function of space and time. In this sense, when the movement of displacement is not known, that is, it does not move in a rectilinear way, in which its trajectory is not identified, the laws of physics establish the mathematical language to observe these displacements, the scalar quantities. Therefore, according to the mentioned authors, “Not all physical greatness involves an orientation. Temperature, pressure, energy, mass, and time, for example, do not ‘point’ in any direction. […] The simplest vector quantity is the displacement or change of position.” (ibidem, 2012, p. 40, our translation).

Transposing this concept of Physics to the discursive field in question, as a kind of analogy, we have the analysis as a referential and, from this, the movement of production of meanings is processed. Between what the discourse expresses and its materiality,17 there is the movement that significantly alters it as a result of the determinations of reality. “So discourse is materiality. It is at the base of this, sustains it, feeds it with meanings and enables the movement of the subjects, in interrelationship.” (Ferreira, 2020, p. 10, our translation). The discourse, which presents nuances, and the reality, because it is characterized dynamic and permeated by contradictions, challenge the researcher to produce analyses from the confrontation and approximations and elaborate the systematization. The production of meanings develops in this movement, between analysis, synthesis, and systematization (Ferreira, Calheiros, and Siqueira, 2020).

As an analogy to the concept of movement in Physics, one can also observe a person standing in a certain place and performing the action of jumping into the air and returning to the same place. Although it did not move from its initial position, it moved away from the surface on which it was for a certain time, returning to the same initial position. Such action is configured as a movement. It is important to point out that movement does not happen only in materiality, but also in subjectivity.18 That is to say, when exercising thought for the production of the senses, movement occurs first of all.

Generally, the conception of movement is linked to the idea of displacement, transmuting from one point and/or state to another, and, not infrequently, is related to a lapse of time. In this way, movement is not something momentary, ready and finished. It occurs over a chronological, historical, social, and contextualized period of time. In this conception, it is assumed that, in order for the movement to happen, it is necessary to have a set of aggregated elements that interact with each other, which implies, directly or indirectly, in influences that the medium exerts in relation to the object analyzed. In short, movement is not something visible, tangible, palpable. It is a phenomenon of subjective characteristics. In the context of the AMS, movement constitutes the point of arrival and departure. For the purpose of systematizing the analysis of the data, it is considered as a category, whose centrality consists in producing the meanings and, a posteriori, enabling understanding.

The following is the description of the AMS and the limits found in the process of analysis of academic productions, especially in dissertations and theses. It is argued from the above and aims to explain the procedures for the analysis of academic works, books and discourses.

ANALYSIS OF THE MOVEMENTS OF SENSES

To carry out studies and research, researchers can start from themes and approaches that, in some way, are linked to their professional and/or academic experiences, as well as to those that relate to certain situations that, in turn, lead to abrupt changes in society. An example of this occurrence is the current pandemic stage, in which much research is being conducted on remote education and the impacts of this moment on the production of investigations. To initiate the studies, evaluating the context in which they occur, the researchers elaborate strategies such as state of knowledge and state of the art. With this, they obtain preliminary information about themes and approaches that are articulated to their research, as well as allows them to confirm the unprecedented character proposed in a research project, thus avoiding redundancy.

To better clarify this reference, we start from the understanding of “state of knowledge”, as Morosini and Fernandes (2014, p. 155, our translation) present the definition: “[…] identification, registration, categorization that lead to reflection and synthesis on the scientific production of a certain area, in a certain space of time, bringing together periodicals, theses, dissertations and books on a specific theme.”.

In this search in different sources, it has been recurrent the finding of significant production of works elaborated with a certain theme, without evidencing the meanings produced. Limits are perceived. One of them concerns the fact that researchers disregard the production immersed in a dialectical totality, which transcends the author and the work at all times, and, in this way, analyze to situate themselves regarding the themes of “[…] a certain area in a certain space and time.” (Morosini and Fernandes, 2014, p.155, our translation). Or they apply states of the art that “[…] they cover a whole area of knowledge […]” (Romanowski and Ens, 2006, p. 39, our translation), in which, not infrequently, they demonstrate understanding of the advances and/or setbacks of a given theme, being able to abstract the meanings and movements produced by the authors in other works with the same theme and disregard the space and time of the production.

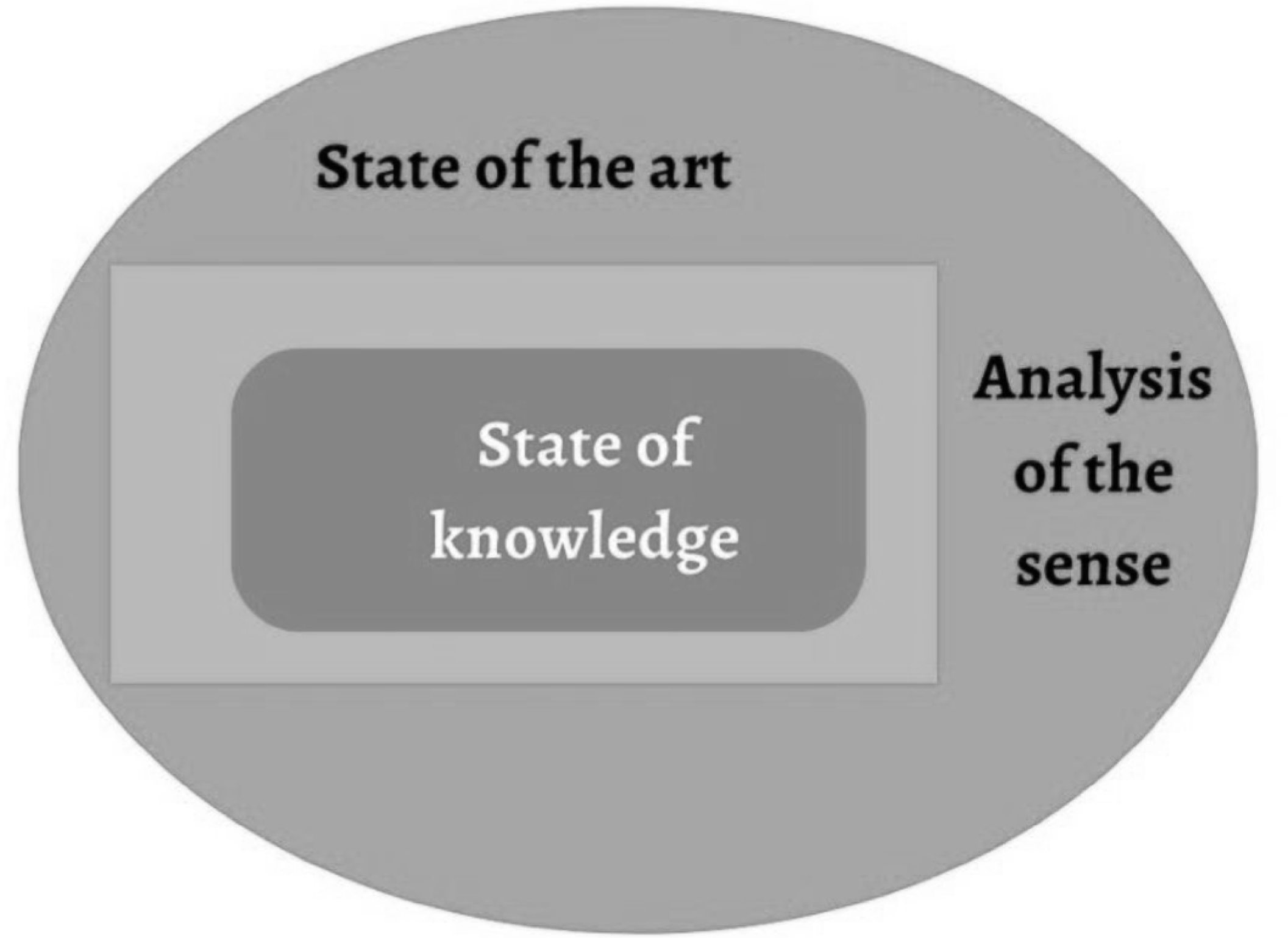

In accordance with what is evidenced in Figure 1, it is understood that the AMS covers the totality and, therefore, it is sought to represent it by a circle where the state of the art and state of knowledge are contained, in closed boxes, considering their limits, which make them static and closed.

Source: Braido (2020).

Figure 1 Relationship between Analysis of the Movement of Senses, state of the art and state of knowledge

Given this, we chose to call AMS, which aims to understand the relationships established about a given phenomenon, in addition to understanding the texts already elaborated on the theme, tending to scrutinize the context in which the productions take place (Ferreira, Zimmerman, and Calheiros, 2020). Thus, this theoretical-methodological foundation of study and research in Education produces and analyzes the data, presents the historicity and contradictions of reality, as capitalist society is configured. In other words, the meanings produced in the analyzed works are highlighted, highlighting the movement found in each sense, which would not be possible to analyze when it comes to meanings, because the essence of meaning is in the movement. The meanings, according to Ferreira (2020), are social constructions, systematized after the debate. In this way, the senses are understood in constant movements: the first, between the senses themselves; and the second movement to come to be signified, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Adaptation by the authors according to Ferreira (2020).

Figure 2 Differences between senses and meaning.

According to Figure 2, separate movements occur because they do not necessarily occur simultaneously. Not infrequently the movements of the senses occur in debates with other interlocutors, without resulting in systematization, therefore, in meaning. Considering these assumptions, from the choice of the theme of approach of the studies the research is made. It is envisaged, with it, to understand the works and studies already carried out that will be a parameter of analysis of the theme and, with this, “[…] to understand the way it expresses itself in different times and places, to know its historicity […]” (Braido, 2020, p. 13, our translation).

Thus, it is necessary to define which types of productions will be analyzed, such as, for example, interviews, legal texts referring to educational policies, books, course conclusion works and/or monographs and/or dissertations and/or theses, academic and/or professional productions, abstracts and/or articles, complete journals, annals of events, among others. Through these different sources of study and research, several possibilities are found and it is up to the researcher to delimit and always keep in mind the object of his research. From this, according to the choice of productions, it is decided which platform of analysis (repositories, libraries, journals, etc.) of the same. At this stage, it is important to pay attention to the observance of certain aspects, according to the discourse. This is what will be following described.

SELECTION OF ACADEMIC PAPERS

At this point, the importance of presenting the descriptor(s), written in all possible ways — with and without accent, with capital letters, with the first capital letter, with the first lowercase letter — is highlighted. If the expression has two words, the first is written with a capital letter and, in turn, the first letter of the second word, with a lowercase letter. Subsequently, it is reversed, as different search results can be obtained. In other situations, words may be synonymous; There are many possibilities and not all of them are present in this explanation, but the idea is to provide clues to the researcher of the importance of thinking about variables, since, according to the platform, the Boolean19 operator must also be considered. In Chart 1, the possibilities are shown and it is emphasized that it is necessary to observe and understand that each circle corresponds to a word of the theme, as exposed.

It is emphasized that Booleans assist in research. In the first line of Chart 1, the search is carried out only in works that contain the expression pedagogical work. The two words, unlike the second case, presented in the second row of the column, which contemplates only productions with the word work, since the Boolean used excludes the second term. In the third case, in the third row of the table, the search is developed in the three possible versions, that is, the words work are inserted; pedagogical and, also, the expression pedagogical work. At the moment in which it is intended to carry out the research on a certain theme, composed of two words, such as the expression pedagogical work, it is indicated that the search is carried out with the words in quotation marks, because, in these terms, the decoder understands the search for these terms according to this order of writing.

To aid in search, certain platforms20 use certain wildcard characters, which would be the asterisk (*) and the question mark (?). The first helps in the search for words with multiple characters, for example pedagog* and then results appear as pedagogy, pedagogue, pedagogue, pedagogy, pedagogical. And if you modify only one character, do you use the question mark, as when searching for pedagog?. The search will be based on words that contain pedagogue.

Once the works that will compose the corpus are selected, the analysis begins, whose steps will be described later in the text.

SELECTION OF WORKS

It encompasses the bibliographic research, which is a technique of data production, carried out throughout the analysis to subsidize the meanings produced. The selected works have in common theoretical perspectives that either approach or distance each other. In this case, it is up to the researchers to clarify these approximations or not. Therefore, the bibliographic research does not concern only the selection, but the criteria for doing so.

Once the materials that make up the research corpus have been selected, the analysis is carried out. In this process, it is intended to highlight the discourses of the subjects, comparing them and articulating approximations and displacements, in view of the discourses “[…] be evidence of the subjects […]” (Ferreira, 2020, p. 9, our translation). In line with this conception, it understands that the discourses refer to

[…] statements organized and expressed by the subjects, through an intentionality, an objective in relation to the interlocutor(s), pre-established and teleologically elaborated, because they anticipate reactions, understandings, interactions to be achieved through the expressive organization of language. (ibidem, p. 4, our translation)

Produced in accordance with social materiality, the discourses express the subjects’ conceptions of the world, how they perceive and understand the contradictions of reality and their positions before the different aspects of the real. Through the discourses, the subjects manifest awareness about reality. Moreover, they present themselves as social beings belonging to a class, constituted by the non-owners of the means of production or, conversely, owners. For Marx (2008, p. 49, our translation), “The mode of production of material life conditions the process of social, political and intellectual life.”. Therefore, under this assumption, the reference, in this text, to the materiality of the production of discourses and to how the social being elaborates the consciousness about the reality of the phenomena.

In the analysis of the discourses are inserted, as techniques, documentary analysis, interviews, questionnaires, field diary, focus groups, among others (Ferreira, 2020). To carry out the documentary analysis, the researcher needs to equip himself with references produced from different instances and perspectives. It can make use of legislation, government projects, positions of subjects linked to the representation of workers, as well as entrepreneurs. In addition to these, there are other possibilities, such as articles published in newspapers, cartoons, documentary sources, as Ciavatta (2010) enumerates. Given the importance of the analysis of the mentioned author, we highlight the research in collections of schools, unions, universities, companies, public agencies, municipal governments, which,

They are, basically, institutions focused on the generation of information and the organization of research sources. The collections can be composed of textual documents, iconographic (photographic and other images, negatives, chromes, engravings, maps), legislation, newspapers and clippings, books, magazines, audiovisual material (cassette tapes, videos, films). The supports can be either printed, or in other material, or digital. (Ciavatta, 2010, p. 22, our translation)

Through these sources and the other research techniques listed above, the process of investigation, analysis and production of synthesis begins, and finally the systematization. This movement encompasses the analysis of works and discourses produced, represented with the sequence in Chart 2, in which the main aspects of each of the stages that are articulated and interdependent are highlighted.

Chart 2 Stages of application of the Analysis of the Movement of Senses

| Research ⇒ | Analysis of data ⇒ produced | Synthesis ⇒ | Systematization |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Bibliographic research; reading reports; collections; journals. | Problematization of phenomena; analysis instruments; language processes between subjects that aim to know the totality. | Groupings of meanings in their similarities. Recompose the text. |

Writing of the syntheses. Argumentation. |

Source: Elaboration by the authors according to Ferreira (2020).

Afterwards, it is suggested the creation of a table, as in Chart 3, for the recording of the first information of the work that also helps in the visualization of the relations of the meanings between the discourses and the respective authors.

Chart 3 Example table for Analysis of the Movement of Senses.

| N | Educational institution | Title | Author | Year | Keywords | Subtitles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | ||||||

| 02 |

Source: Elaboration by the authors.

It is exemplified with a table for the analysis of academic works and/or articles.

The items specified in Chart 3 show the meanings, such as the year in which there is significant production for the category in question. It is up to the researcher to elaborate hypotheses for this category, due to the emphasis or even the reduced insertion in the studies in a given educational institution. According to the situation analyzed, there are possibilities to point out interesting elements, such as, for example: why in a given institution(s) there is a higher or lower incidence of interest in the theme; from which point of view the journals conceive the object investigated; what other themes the author relates to the main focus of the research; and as he approaches the topic defined in his work from the subheadings present in the text.

In addition, the organization of the essential information of the productions intends to evidence the distribution of research in the Brazilian states, if it is a necessary item for the study. With this procedure, it becomes possible to elaborate hypotheses about the study of the theme in each region, among other possible meanings defined according to the interests of the researchers.

In the analysis of educational institutions, one can think and inquire about the administrative dependence in which it is found and whether the research is in accordance with the areas of knowledge of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES). Finally, data are elaborated related to the theme of study with its secondary focuses, which, in the case of the studies carried out, can be

pedagogical work in early childhood education;

pedagogical work in elementary school;

pedagogical work in high school;

pedagogical work in higher education; etc.

Subsequently, the rereading of the works under analysis is indicated, highlighting, in a second table, the items of interest of the research. Depending on the theme, different criteria can be selected. The following are exemplified as:

the central theme of the work;

panel of evaluators (if the intention is to evaluate the existence of a research network on the subject);

structure of the work (if one wants to understand how research in the area of knowledge happens);

references on the central theme (to visualize the authors and works that support the studies on the theme); and

author information.

This and the other tables are examples of instruments based on which the analysis of meanings will take place.

Then, the analysis and movement of meanings begins, in which the reality, the context and the historical time are considered fundamental to the apprehension of the concepts and approaches presented by the authors in their works. At this point, one can seek explanations as hypotheses about what is made explicit, in order to understand the meanings produced by the author. It is noteworthy that there is no recipe to be followed to seek the senses produced. It is proposed to think of all the possibilities, however, always related to the phenomenon under analysis, to the historicity of the discourse or its subject, and also to the totality of capitalist society.

Initially, one can reflect on the origin of the production of the work according to the educational institution, if there are groups of research and studies on the subject, if there are disciplines in graduate programs on a certain subject, if the course in which the research is carried out is in the institution from the demand of the community and what is the relationship of the theme with the institution. In addition, it is asked about the relationship of the author with this theme: if it is the first approximation or if he has already addressed this theme; if in the year of the defense and/or publication there are also other authors researching on the same topic; whether this research theme has been recurrent in the institution, or in other institutions; whether these are public or private; why it presents peak or decline of productions in defined periods. With this, hypotheses are elaborated according to the annual production and the historical facts that move society, laws and decrees. In relation to legislation, as an object of study, the conception of Ciavatta (2010, p. 18, our translation) stands out: “Laws are also elaborated as new discourses that should propel society in a certain direction, but that can be understood in different ways.”. For these specific discourses, appropriate analysis criteria are created.

One can, as a continuous act, characterize the meanings produced in each work, that is, how each author understands the theme, identify the panel of evaluators, if these are recurrent, and why; which institutions they represent, and the most requested for the theme. In addition, there are conditions to verify the references cited in the researches, the recurrent methodologies cited as possibilities to start the production of data. It is also possible to verify aspects of the historicity of the theme in the researches developed, how they present the chosen theme, how they approach the proposed theme, if the structure presents the central elements: introduction, problematization, objectives, justification, development, theoretical foundation, methodology and conclusion. It is important to emphasize the importance of considering the following analysis criteria: there is or there is not repetition of investigative themes; there is a finding of new elaborations in the titles and subtitles, how they appear and relate to the research. It is observed whether the abstracts contemplate the research and meet the formal criteria of academic writing satisfactorily or not, and, finally, are identified in the texts images, graphics, or other support tools.

From these considerations, it is noteworthy that part of the suggestions on how to start the work was presented, by way of exemplification, and it is appropriate to adapt, expand and adapt them to the study to be carried out. As a rule, it is considered that, with this theoretical-methodological foundation applied to the study and research, the AMS, each researcher will present different results, because data were produced under different conditions, times and by different subjects. Therefore, they have their specificities. In any case, the study, once completed, can be a reference for other studies, with new approaches and resized.

BY WAY OF CONCLUSION

If movement is the centrality, it would be a mistake to state that the study and research proposal, based on the theoretical-methodological foundation, called AMS, ends with the explanations and arguments exposed in this article. The beginning can be the end, for while one cherishes the totality of the senses, one can end inconclusively. It is understood that, for the AMS, the production of meanings happens in the movement of analysis of phenomena and this movement is processed in its totality, permeated by contradictions. The historicity of the phenomena of reality is articulated with the other highlighted categories and, together, they are fundamental in the elaboration of the investigation to which the researcher proposes and remain until its conclusion. From the investigation to the analysis, synthesis and systematization, it is essential to permanently observe the problematization that generated the study.

In this article, we started from the description of discourse, meaning and movements, to present a proposal for research in Education, called AMS. Next, possibilities for the realization of this proposal were described with examples of steps and phases to be carried out. It was concluded, reiterating how productive it is to research considering the discourses of the subjects, expressed in the most different forms, as material evidence and, as a result, analyzeable of their movements in the social.

It was assumed, in the text now finalized, that all research is or should be unpublished, because each subject analyzes according to their perspective, knowledge and according to the characteristics of the research project. In this way, the movement is valued, by the relations that can be established from the theme with the phenomena that permeate the productions. As Camões states, in the epigraph of this text, “the whole world is composed of change, always taking on new qualities”, therefore, there is no way to finish, only to let it flow to other possibilities.

1In this analysis, we understand the discourses produced from social relations, which are “[…] ideological because, to say the world, represent it and conceptualize it, the discourses do so according to class interests.” (Cury, 1986, p. 46, our translation). Also, from Ferreira (2020), the discourses evidence what the subjects think and produce; it is the evidence of the subjects; they bring together senses and meanings and, moreover, can be formal and informal, academic or not. Also, speeches are “[…] statements organized and expressed by the subjects, through an intentionality, an objective in relation to the interlocutor(s), pre-established and teleologically elaborated, because they anticipate reactions, understandings, interactions to be achieved through the expressive organization of language.” (Ferreira, 2020, p. 4, our translation).

2It concerns the understanding of reality in a partial way, limited to appearance. “The complex of phenomena that populate the everyday environment and the common atmosphere of human life, which, with their regularity, immediacy and evidence, penetrate the consciousness of the individual agents, assuming an independent and natural aspect, constitutes the world of pseudo-concreteness.” (Kosik, 1976, p. 15, our translation, emphasis in the original). The author presents an example that enables the apprehension of the concept of pseudo-concreteness: “Men use money and with it make the most complicated transactions, without even knowing, nor being obliged to know, what money is. Therefore, the immediate utilitarian praxis and the common sense corresponding to it put the human being in a position to orient himself in the world, to become familiar with things and to manage them, but they do not provide the understanding of things and reality.“ (ibidem, p. 14, our translation, emphasis in the original). Therefore, “Pseudo-concreteness is precisely the autonomous existence of man‘s products and the reduction of man to the level of utilitarian praxis.” (ibidem, p. 24, emphasis added, our translation).

3In chapter 1, “The Commodity”, of Capital, Marx (2013) explains the transformation of use value into exchange value and how this was consolidated in the capitalist social relation. In this society, “[…] of commodity producers, whose general social relation of production consists in relating to their products as commodities, that is, as values, and, in this reified form (sachlich), to mutually confront their private labors as equal human labor […]” (Marx, 2013, p. 153-154, emphasis in the original, our translation). Therefore, reified has its origin in the word “sachlich”, “reified form” (ibidem, p. 154), and consists of understanding the social process of life impregnated with “[…] mystical veil of mist […]” (ibidem, p. 154, our translation).

4This is the conception of Vázquez (2011), which he defines as a central concept of Marxism and understands as a process of interpretation and transformation of the world. One has, on the basis of the studies of Marx and Engels, the category “praxis”, elaborated from the “[…] conception of man as an active and creative being, practical, who transforms the world not only in his consciousness, but also in his practice, really. […] Production — that is, productive material práxis — is not only the foundation of man's dominion over nature, but also of his own dominion. Production and society, or production and history, form an indissoluble unity.” (Vázquez, 2011, p. 53-54, our translation, emphasis in the original).

5 Triviños (1987) relates the characteristics of the materialist conception, one of them being the materiality of the world, “[…] that is, all the phenomena, objects and processes that take place in reality are material, that they are all simply different aspects of matter in motion.” (Triviños, 1987, p. 52, our translation, emphasis in the original). Already, for Bello (2006), “Phenomenon” means what is shown; not only what appears or seems (Bello, 2006, p. 17). For Netto (2006, p. 17, our translation) “[…] phenomena are processes […]”.

6“Field” is a notion proposed by Bourdieu (2004, p. 20, our translation), an author who is not included among the Marxist ones, but who undoubtedly produced his work under the influence of these authors: “relatively autonomous space, this microcosm endowed with its own laws.”.

7From the exposition on the method of political economy, Marx (2008) approaches the process of study and analysis of reality in its totality, with all its relations. It defines its method as “[…] manifestly the scientifically accurate method. The concrete is concrete because it is the synthesis of many determinations, that is, unity of the diverse.” (Marx, 2008, p. 260, our translation).

8According to Netto (2011), the categories are reflective; reflections of the real and belong to thought. It also defines as forms of way of being; determinations of existence, therefore, are ontological, historical, and transient. For Cury (1986, p. 21, our translation), “Categories are basic concepts that intend to reflect the general and essential aspects of the real, its connections and relations. They arise from the analysis of the multiplicity of phenomena and claim a high degree of generality.”. According to Kosik (1976), the categories derive from a correct concept of social reality. For Trivinõs (1987, p. 54, our translation), the categories exist objectively and are “[…] understood as ‘forms of awareness of the concepts of the universal modes of man's relationship with the world, which reflect the more general properties and laws and essences of nature, society and thought’ and have a long story.”.

9According to Vázquez (2011, p. 298, our translation), revolutionary praxis “Linked to the objective aspect is the possibility of an effective transformation of society.”.

10For Ferreira, Cezar, and Machado (2020, note 06, our translation), “Research and study are differentiated. That concerns only the production and analysis of data. The study, from what is understood, includes research and goes beyond, analyzing not only the data produced, but the conditions of production, the interlocutory subjects and the productions of other authors, in the academic community.”.

11This elaboration took place within the scope of the research group in which we work. This is the Kairós — Group of Studies and Research on Work, Education and Public Policies. As a theoretical and methodological foundation, the AMS is registered in several articles and has already been worked on in dissertations and theses published in the repository of the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM).

12In the dictionary, the term approach comprises the following meanings: 1. The act of one boat approaching another, edge to edge (to enhance, attack, etc.); 2. Assault on a ship; 3. Collision. In.: Priberam Dictionary of the Portuguese Language [online], 2008-2020. Available at: https://dicionario.priberam.org/abordagem. Accessed on: Oct. 28, 2020.

13For the term method, two perspectives are presented. The first emphasizes that “method means a path — odos — to an end (or beyond) — a goal […]” (Souza, 2009, n. p., our translation). In the second perspective, the author defines method as “[…] the set of guiding principles and procedures of a scientific research.“ (ibidem, n. p., our translation). The author also associates this perspective with what „[…] favors a development that links the idea of method to that of science.” (ibidem, n. p., our translation, our highlight).

14The word technique is a feminine noun and covers different meanings, namely: „1. Material part of an art; 2. Set of processes of an art; 3. Practice.”. (In: Dicionário Priberam da Língua Portuguesa [on-line], 2008-2020. Available at: https://dicionario.priberam.org/t%C3%A9cnica. Accessed on: Aug. 7, 2023). “Being the form of production of some material or ideal product, the technique by nature proves to be historical, since it is the aspect of a human process of creation. […] with the emergence of consciousness, it becomes social and dictated by purposes.” (Vieira Pinto, 2005a, p. 156, our translation).

15The word methodology is inserted in the gender of the feminine noun and in the dictionary presents the following definitions: 1. Art of directing the spirit in the investigation of truth; 2. Application of the method in teaching: In: Priberam Dictionary of the Portuguese Language [online], 2008-2020. Available at: https://dicionario.priberam.org/metodologia. Accessed on: Oct. 30, 2020.

16DICIO. Online Dictionary of Portuguese, definitions and meanings. 2009-2020. Available at: https://www.dicio.com.br/fundamento/#:~:text=substantivo%20masculino%20plural%20Fundamentos.,Do%20latim%20fundamentum. Accessed on: Oct. 5, 2020.

17It is based on the conception of Marx and Engels (2009, p. 31, our translation), in The German ideology, who expresses: “The production of ideas, representations, consciousness is in principle directly intertwined with the material activity and material exchange of men, language of real life.”. Trivinõs (1987) discusses the categories of dialectical materialism, matter, consciousness and social practice and, in relation to matter, points out that, in the context of Philosophy, Lenin defines it as a “philosophical category”, and translates it: “[…] the philosophical category of matter, […] relates to its general property of being objective, that is, of existing independently of our consciousness and being reflected by it.” (Trivinõs, 1987, p. 57, our translation). Therefore, materiality refers to the material unity of the world, to reality.

18The comprehension of subjective characteristics is based on the elements that constitute the subjective dimension of reality. Here, the subjective dimension is understood in the dialectical relationship between subjectivity, taken as individual, but socially constituted, and objectivity, historically constructed from the collective action of humans, and therefore loaded with subjectivity (Bock and Aguiar, 2016).

19Booleans (AND, NOT, OR) should always be capitalized. The expression “Boolean” comes from George Boole, English mathematician, creator of Boolean algebra. Available at: https://www.dbd.puc-rio.br/sitenovo/#aviso. Accesse on: Aug. 4, 2023.

20One of them is the Capes Thesis Bank. Available at: https://catalogodeteses.capes.gov.br/catalogo-teses/#!/. Accesse on: Aug. 4, 2023.

REFERENCES

ANTHONY, E. M. Abordagem, Método e Técnica. Tradução de MEIRELES, A. J.; RODRIGUES, V. M. A.; ALMEIDA FILHO, J. C. P. English Language Teaching (ELT), v. 17, p. 63-67, 1963. Disponível em: http://www.helb.org.br/index.php/revista-helb/ano-5-no-5-12011/187-abordagem-metodo-e-tecnica. Acesso em: 12 out. 2021. [ Links ]

BELLO, Â. A. Introdução à fenomenologia. Bauru: EDUSC, 2006. [ Links ]

BOCK, A. M. B.; AGUIAR, W. M. J. . A Dimensão subjetiva: um recurso teórico para a Psicologia da Educação. In.: AGUIAR, W. M. J.; BOCK, A. M. B. (org.). A Dimensão Subjetiva do Processo Educacional: uma leitura sócio-histórica. São Paulo: Cortez, 2016. p. 43-59. [ Links ]

BORGES, E. F. V. Metodologia, abordagem e pedagogias de ensino de língua(s). Linguagem & Ensino, v. 13, n. 2, p. 397-414, 2010. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. Os usos sociais da ciência: por uma sociologia clínica do campo científico. São Paulo: UNESP, 2004. [ Links ]

BRAIDO, L. S. Gestão escolar no curso de especialização em Gestão Educacional (presencial) da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria: análise dos movimentos de sentidos. 2020. 41 f. Monografia (Especialização em Gestão Educacional) — Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, 2020. [ Links ]

CAMÕES, L. Mudam-se os tempos, mudam-se as vontades. In: GRÜNEWALD, J. L. Luís de Camões Lírica. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1992. p. 37. [ Links ]

CIAVATTA, M. Arquivos da memória do trabalho e da educação: Centros de memória e formação integrada para não apagar o futuro. In: CIAVATTA, M.; REIS, R. R. A pesquisa histórica em educação. Brasília: Liber Livro, 2010. p. 15-35. [ Links ]

CURY, C. R. J. Educação e contradição: elementos metodológicos para uma teoria crítica do fenômeno educativo. São Paulo: Cortez: Autores Associados, 1986. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S. Trabalho pedagógico na escola: sujeitos, tempo e conhecimentos. Curitiba: CRV, 2017. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S. Discursos em análise na pesquisa em educação: concepções e materialidades. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 25, e250006, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782019250006 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S.; BRAIDO, L. S.; DE TONI, D. L. P. Pedagogia nas Produções Acadêmicas da Pós-Graduação em Educação no Rio Grande do Sul: Análise dos Movimentos de Sentidos. Revista Cocar, Belém, n. 8, 2020, p. 146-164, 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicos.uepa.br/index.php/cocar/article/view/3052. Acesso em: 10 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S.; CALHEIROS, V. C.; SIQUEIRA, S. Educação Profissional e Tecnológica no Rio Grande do Sul com base em uma leitura das pesquisas na Pós-graduação no Estado. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 38, n. 2, p. 1-22, abr.-jun. 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/perspectiva/article/view/2175-795X.2020.e65080/pdf. Acesso em: 13 out. 2020. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S.; CEZAR, T. T.; MACHADO, C. T. Grupo de interlocução na pesquisa em educação: produção, análise e sistematização dos dados. Pro-Posições, Campinas, SP, v. 31, e20190025, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2019-0025 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S.; DE TONI, D. L. P.; BRAIDO, L. S.; NASCIMENTO, M. R. C. Trabalho pedagógico e valorização profissional: uma análise na historicidade do Curso Normal no Rio Grande do Sul. Cadernos de Pesquisa: Pensamento Educacional, Curitiba, v. 14, n. 38, p. 197-219, set.-dez. 2019. https://doi.org/10.35168/2175-2613.UTP.pens_ed.2019.Vol14.N38.pp197-219 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, L. S.; ZIMMERMAN, A. P. C.; CALHEIROS V. C. Trabalho pedagógico, trabalho dos professores e trabalho docente: movimentos de sentidos nas abordagens sobre educação física escolar. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 26, e26045, 2020. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.99565 [ Links ]

HALLIDAY, D.; RESNICK, R.; WALKER, J. Fundamentos de Física. v. 1. Rio de Janeiro: LTC, 2012. [ Links ]

HUNGARO, E. M. A questão do método na constituição da teoria social de Marx. In.: CUNHA, C.; SOUSA, J. V.; SILVA, M. A. S. (org.). O método dialético na pesquisa em educação. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2014. p. 15-78. [ Links ]

KOSIK, K. A dialética do concreto. 7. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1976. [ Links ]

LUKÁCS, G. Para uma ontologia do ser social II. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2013. [ Links ]

MARX, K. Contribuição à crítica da economia política. 2. ed. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2008. [ Links ]

MARX, K. O Capital: crítica da economia política. Livro I: o processo de produção do capital. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2013. [ Links ]

MARX, K.; ENGELS, F. A Ideologia Alemã. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2009. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, I. A educação para além do capital. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2008. [ Links ]

MÉSZÁROS, I. Para além do capital: rumo a uma teoria da transição. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2011. [ Links ]

MOROSINI, M. C.; FERNANDES, C. M. B. Estado do Conhecimento: conceitos, finalidades e interlocuções. Educação Por Escrito, Porto Alegre, v. 5, n. 2, p. 154-164, 2014. https://doi.org/10.15448/2179-8435.2014.2.18875 [ Links ]

NETTO, J. P. O que é marxismo. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2006. [ Links ]

NETTO, J. P. Introdução ao estudo do método de Marx. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2011. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, I. D. W. M.; FERREIRA, L. S. Gestão escolar e Pertença Profissional: uma análise dos discursos de professores iniciantes. Reflexão e Ação, v. 28, n. 2, p. 251-262, jun. 2020. https://doi.org/10.17058/rea.v28i2.13058 [ Links ]

ROMANOWSKI, J. P.; ENS, R. T. As pesquisas denominadas do tipo “Estado da Arte” em educação. Revista Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 6, n. 19, p. 37-50, 2006. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, S. de. Integração curricular e trabalho pedagógico: uma análise com base nos discursos de professores do IFFar Campus Júlio de Castilhos. 2020. 153 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica) — Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, 2020. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufsm.br/bitstream/handle/1/21119/DIS_PPGEPT_2020_SIQUEIRA_SILVIA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Acesso em: 10 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

SOUZA, R. A. Método. E-Dicionário de Termos Literários de Carlos Ceia. 2009. Disponível em: https://edtl.fcsh.unl.pt/encyclopedia/metodo. Acesso em: 28 out. 2020. [ Links ]

TRIVINÕS, A. N. S. Introdução à pesquisa em ciências sociais: a pesquisa qualitativa em educação. São Paulo: Atlas, 1987. [ Links ]

VÁZQUEZ, A. S. Filosofia da práxis. 2. ed. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2011. [ Links ]

VESCHI, B. Etimologia de Metodologia. 2019. Disponível em: https://etimologia.com.br/metodologia/. Acesso em: 5 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

VIEIRA PINTO, Á. O conceito de tecnologia. v. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005. [ Links ]

Received: August 26, 2021; Accepted: August 24, 2022

text in

text in