Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.28 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub Oct 20, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782023280115

Article

Sensitivities of past and present in the curriculum: history in portuguese basic education

IColégio Externato Imaculada Conceição, Maia, Portugal.

IIInstituto Politécnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal.

This paper seeks to understand how the national curricular guidelines for the History curriculum component, in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education in Portugal, dialog with sensitive themes. Considering the most recent documents — Metas Curriculares (2012–2021) and Aprendizagens Essenciais (2018–present) — from a comparative perspective, but not exclusively so, an analysis of ‘socially active questions’ included in or excluded from those was made, along with that of the sense of teaching and the underlying history learning. That initial approach has thus enabled a definition of revealing categories and subcategories. It has also created further data interpretation based on the principles arising from Curriculum and History Education research. Among the main results, stands out a certain prevalence of a (individual? collective?) memory emerging from some (intentional? accidental?) oblivion of the past, and which seems to be incapable of encompassing various sensitivities of contemporary times.

KEYWORDS history education; curriculum; sensitive topics; learning competencies

Este artigo procura compreender o modo como as orientações curriculares nacionais para a componente curricular de História, no 2.° e 3.° ciclos do Ensino Básico em Portugal, dialogam com os chamados temas sensíveis. Tomando em consideração o conteúdo dos documentos curriculares mais recentes — Metas Curriculares (2012–2021) e Aprendizagens Essenciais (2018–presente) — numa lógica comparativa, mas não só, observaram-se as “questões socialmente vivas” incluídas ou excluídas, bem como o sentido do ensino e da aprendizagem histórica subjacente. Essa leitura inicial permitiu a definição de categorias e subcategorias e uma interpretação dos dados baseada nos princípios que decorrem dos Estudos Curriculares e da Educação Histórica. Como principais resultados sobressai certa prevalência de uma memória (individual? coletiva?) que se faz de alguns (intencionais? imponderados?) esquecimentos do passado e que também parece não ser capaz de contemplar as várias sensibilidades da contemporaneidade.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE educação histórica; currículo; temas sensíveis; aprendizagens

Este artículo pretende entender cómo las directrices curriculares nacionales para el componente curricular de Historia, en el 2° y 3° ciclo de la educación básica en Portugal, dialogan con los temas sensibles. Teniendo en cuenta los documentos curriculares más recientes — Metas Curriculares (2012–2021) y Aprendizagens Essenciais (2018–actualidad) — en una lógica comparativa, pero no solo, se observaron las “cuestiones socialmente vivas” incluidas o excluidas, así como el significado de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje histórico subyacente. Esta lectura inicial permitió definir las categorías y subcategorías pertinentes, además una interpretación de los datos basada en los principios derivados de la investigación curricular y de la didáctica de la historia. Como principales resultados destaca una cierta prevalencia de una memoria (¿individual? ¿colectiva?) que está hecha de algún olvido (¿intencionado? ¿reflexivo?) del pasado y que además parece no poder contemplar las diversas sensibilidades de la contemporaneidad.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación histórica; curriculum; temas sensibles; aprendizaje

INTRODUCTION1

Topics which raise awareness, are disturbing or become controversial have increasingly become the subject of public debate. Contradicting points of view highlight memories which can be more or less discordant, and prompt more or less activated sensitivities.

Within a school context, for example, such socially acute questions may be discussed in the History lessons or other similar curricular components, not only to ensure that students acquire substantive knowledge, but also for the development of a historical thinking based on multi-perspective, empathy or argumentation based on evidence.

Nevertheless, it is relevant to note that much of what happens in the classroom is a result of that which has been established in official documents, often for the national framework. Therefore, all items included or excluded from the lessons will also have an impact on the (historical) training of children and young people.

The aim of this paper is thus to present the result of research work which discussed memories of political, ethnic and racial, and gender violence (specifically as regards women in the latter) in authoritarian regimes and democratic contexts within the core of the Portuguese education reality, and it was based on the two most recent curricular documents — the learning goals known as Metas Curriculares (2012–2021) and the key learning outcomes known as Aprendizagens Essenciais (currently in use). The object of study was Ensino Básico (the Portuguese basic education from 1st to 9th grade), with an emphasis on the specific curricular components of History (2.° and 3.° ciclos, ranging from 5th to 9th grade): Portugal History and Geography (5th and 6th grades) and History (7th, 8th and 9th grades).2

Following this brief introduction, there is an explanation of the theoretical framework of this research work and also the clarification of the chosen methodological options. At the end of the analysis and discussion of the collected data, it is possible to draw some considerations retrospectively and, to some extent, prospectively as well.

At this stage, it is worth noting that the purpose of the following text is to understand how national curricular guidelines for the curricular component of History in Portuguese Basic Education communicate with topics considered to be sensitive.

CURRICULUM IN CONTEMPORARY EDUCATIONAL SYSTEMS

It is possible to state from an early start that the curriculum is particularly relevant in the various education systems (Goodson, 1997; 2012; Gimeno Sacristán, 2015; Duarte, 2021). In fact, in accordance with Young (2014), it derives from the idiosyncratic concept of educational organizations — and subsequently educational studies. It is therefore a characteristic element of such organizations, which sets them apart from all other institutions, since no other includes it in its purpose or dynamics. Nevertheless, it is also noted that the concept is not commonly included in reflections emerging from various educational contexts and that it is considered discordant and unrelated to pedagogical practices instead (Freitas, 2019). Such peculiarities may be explained by the inexistence of a unanimous definition of the concept (Kelly, 2004; Silva, 2016) or, also by the fact that the curriculum becomes different in the various formative realities (Steinberg, 2016).

A certain elasticity — and partially some ambiguity — can be seen in association with the term curriculum, which creates diverse definitions according to different historical moments or based on various theoretical positions (Goodson, 1997). In that sense, it seems clear that curricular studies inevitably need to include the polysemy associated with the word, which reveals the simultaneous complexity and (potential) richness of curriculum (Gimeno Sacristán and Pérez Gómez, 2008).

Given its terminological diversity, it is important that the definition of curriculum is considered explicitly in each paper. In this particular case, it is perceived as “[…] a political-educational project, humanly and interactively (re)constructed and lived, around school knowledge and experiences” (Duarte, 2021, p. 41, our translation).

From this position and in view of all the data that will be presented, there are three underlying dimensions worth considering in greater detail:

the interaction between curricular thinking and political and/or ideological dimensions;

its connection to knowledge and the importance of the latter for educational systems;

the implication of curriculum in the humanisation and identity/ies of the various school agents.

Considering the ideas of Freitas (2019), and as regards the Portuguese reality, the most common explanation links curriculum to an artefact that can be more or less changeable, and which identifies what and sometimes how to teach. That idea tends to take curriculum as a product (Kelly, 2004), traditionally exogenous to each reality, that is to say, as an apolitical text solely defined and established according to a technical rationality of definition or discovery of the ideal script (Kliebard, 2004). This vision is, to some extent, the result of the thinking of first generation curricular studies, which were linked to an effective relationship with the Tylerian rationale (Beyer, 2004). Alongside the work of Burns (2018) and Saltman and Means (2019), that same framework is responsible for narrowing curriculum to aspects similar to a list of predetermined objectives, standardised assessment and, more commonly, didactical scripts considered to be sound practices, including in the present moment.

On an international scale, a set of political and educational options — arising from a global education reform movement (GERM) — have indeed become dominant, bearing visible repercussions in curricular decisions, such as standardisation and narrowing of learning, practice homogenisation, deprofessionalisation of professionals, among others (Sahlberg, 2021).

An excessive technical/technological display becomes evident, and it detaches curriculum from any wider pedagogical, social or political reflection. At the same time, there is an image of neutrality, as if creating and developing it could be dissociated from any more complex social connections. This idea interacts with the urgency of the immediate, which highlights an eminently technical reflection — with repercussions in its textual and processual expression —, restricts the possibility and the importance of a more combined consideration of educational phenomena, their purposes and how they relate to the diverse social contexts (Torres Santomé, 2015).

Based on a certain resurgence of curricular theories and research, however, there is a growing idea that “[…] curriculum is not a neutral body, innocent and disinterested of knowledge” (Silva, 2016, p. 46, our translation). Consequently, there is a dimension surpassing instruction logics and which implicates it in a wider political reflection (Torres Santomé, 2017; Apple, 2019).

It is thus perceived as a social construction (Goodson, 1997; 2012), and for that reason granted an ideological dimension which is transverse to various areas, inevitable in any social artefact. In fact, it is the way to value its aforementioned intrinsic diversity, and to refuse any canonical, standardising or potentially technocratic logic that it may be associated with (Steinberg, 2016).

It is indeed understood that different papers have discussed the way ideological, ethical and social questions, for example, have an impact on curricular design and experience. To better illustrate such a connection, and linking the idea with the second aspect to be discussed, it is necessary to consider the knowledge which is or is not included in curricular choices.

By considering the approaches of Torres Santomé (2017) and Apple (2019), for example, it becomes clear that there is a connection between curriculum and knowledge according to two complementary logics.

The first refers to the way inequalities in cultural representation are also visible in the curriculum, since the groups with greater social and economic power aim to either make their dominant position legitimate, or increase the symbolic value of their knowledge through that element — it is important to notice, for example, that, in some social contexts, there is an attempt to balance the legitimacy of creationist visions with Darwinist theories through the school curriculum; and how the curriculum does or does not encompass the historical visions of minorities or colonised communities.

The second logic matches the design and perpetuation of the hierarchisation of various areas of knowledge in the curriculum. As regards this topic, there has been a growing focus on Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM areas) over the last few years, and also the inclusion of new areas, such as financial education, over other components, such as artistic education or social or human sciences.

The previous paragraphs thus highlight a structuring element for any curricular thinking: knowledge and selection, organisation and legitimation of knowledge in (and through) school realities (Goodson, 1997; 2012; Kliebard, 2004; Gimeno Sacristán and Pérez Gómez, 2008; Gimeno Sacristán, 2015). Contemporary reflections explain that decision emerges from implicit various motivations, resulting from distinctive political, social, ethical and pedagogical positionings. Additionally, the selected options have gradually been perceived as having implications in the creation of common senses (Torres Santomé, 2017) in a community or, in a different sense, they interfere with the development of identity references for each student (Silva, 2016).

This means curricular artefacts not only interact with specific ideological guidelines, but they also have profound impacts on the way children create mechanisms based on their school experiences for developing awareness and positions towards the remaining members of the community, in their processes of intersubjectivity (Duarte, 2021). In the words of Torres Santomé (2015, p. 152, our translation), “[…] all curricular proposals imply making choices on parts of reality, imply a cultural selection offered to the new generations in order to make their socialisation easier, so as to help them understand the world around them, to know their history, values and utopias”. This is particularly interesting when documents that compose the common curriculum are used as reference, as they enable the identification of the cultural heritage that all children of a country learn and share. Their connection to the design of common references which are directly linked to the construction of individual and collective identities of each student (Gimeno Sacristán, 2015; Silva, 2016) is thus undeniable.

It is therefore relevant to refer to Goodson (1997; 2012). According to the author, national curricular documents — which may be understood as the preactive written curriculum — are particularly interesting for/in curricular reflection. There are two complementary lines to be highlighted regarding this point: on the one hand, these artefacts “[…] represent visible, public and authentic evidence of the constant quest involving the aspirations and objectives of schooling” (Goodson, 2012, p. 105, our translation); that is to say they take on a symbolic dimension illustrating and legitimising knowledge and values to be preserved and shared with the younger generations; on the other hand, such curricular documents — which in the case of Portugal take on the role of national curricular guidelines — become relevant to what is truly experienced and grasped by students, given the fact that text curriculum “[…] frequently sets important parameters for practices in the classroom (not always, not in all occasions, not in all classrooms, but frequently)” (Goodson, 1997, p. 20, our translation).

To some extent, the previously mentioned two points do clarify the importance of research based on curricular documents.

On this topic, in terms of the Portuguese reality, it is necessary to highlight two distinctive political periods. The first, that of the normative recontextualization of the curriculum (from 2012 to 2017), pursued the reinforcement of subjects considered to be fundamental and established national curricular documents — the learning goals known as Metas Curriculares — which revealed an essentially technical logic for teaching; as previously mentioned, that situation was related to transnational political and educational movements (GERM), at least partially (Sahlberg, 2021). The second period, which started in 2017 and continues to this date, was known as Curricular Flexibility and favoured a type of speech more centred on the autonomy of each school; furthermore, it was characterised by the establishment of new curricular documents — the key learning outcomes known as Aprendizagens Essenciais —, with all other national curricular documents being revoked in 2021 (Duarte, 2021).

Although there is some range associated to curriculum and its field of studies, which is by definition part of and encompasses a wide set of school subjects and research areas, it is relevant not to reduce it to some sort of universal didactics, to be unilaterally owned by each of the curriculum components (Gimeno Sacristán and Pérez Gómez, 2008).

In that context, we have chosen to focus our attention on the possible conversation between previously discussed aspects and the formative peculiarities underlying the teaching and learning process of the subject of History. A curricular component amidst so many others that Portuguese students have the opportunity to study throughout their compulsory education.

SENSITIVE TOPICS AND TEACHING HISTORY

Between memory and sensitivities

Memory may be explicitly understood as an alternative source of knowledge, and some state categorically that “[…] without memory nothing exists, we are nothing, and neither is it possible to understand the world we live in” (Lomas, 2011, n. p., our translation).

Nevertheless, and as “there is no unique and correct vision of the past, we all create our own visions of the past” (Cooper, 2002, p. 35, our translation), it is important to understand readings of the past arising from collective memories, whether they emerge from abusive use of the past, ideological confrontation between different times, or underlying political interests.

In other words, and in accordance with Traverso (2012), it makes more sense to choose an enlightened historical interpretation of the behaviour of various social actors within their time under any circumstance, but without an inherent justifying intention. It is the way to acquire a critical perspective regarding the range of existing reminiscences.

Such memories frequently refer to issues known as “socially acute questions” (Legardez and Simonneaux, 2006, p. 1, our translation), for example in association with the cultural diversity between populations, traumatic experiences, individual testimonials, consented silencing acts or the search for truth or justice.

Such are the complex topics that create distress, undermining feelings or disturbances and as such, within an empathic but not apologetic logic (Traverso, 2012), they encompass doubt, discussion and have yet to include plural interpretations and the senses of transformation, which may be more or less wide. It is therefore not strange to note that such sensitive questions generate numerous social debates, repeatedly superficial, and are not included in the teaching and learning process (Legardez and Simonneaux, 2006). As a result, there are various single-explanatory and more positive trends for the group itself, reports that do not compromise national pride and essentialist and romantic readings of reality to be taken as an absolute and undisputed truth.

Apparently, “[…] disturbing historical experiences require an interpretative overcoming, which can only be accomplished by genuine historical interpretation” (Barca, 2019, p. 509, our translation). That solution may then translate into reasonable historiographical individual and collective reflections and thus be separated from eventual simplifications of facts, binary interpretations, inappropriate comparisons or inaccurate categorisations (Alberti, 2014; Barca, 2019).

As disturbing topics tend to balance current certainties and expectations about the future, this pact with the past becomes fundamental in order to clarify the relationships between sensitivities and current history. Furthermore, according to Barca (2019, p. 501, our translation), it includes different times: “[…] times of mourning, times of fighting, times of negotiation of past senses in (more) balanced terms and of humanistic dialogue”.

Using the available evidence as grounded and rational evidence, the confrontation between sources with different perspectives, the acknowledgement of particularly emotional visions which are biased, the most intricate facts that have taken place are historically understood in a gradual way and in an oriented ethical sense. Simultaneously, individuals who are also historical actors develop transverse competences, such as critical questioning, the appreciation of diversity on various levels, the refusal to accept a softening of the actions of different agents, the fixed and finished reports or naturalizations of evil and inequality, for example (Lomas, 2011).

Sensitivities in History teaching

Whether the aim is to develop conscious and responsible citizenship, or whether that is not the aim of the formative intention, the truth is you cannot limit the access to knowledge about the past which erupts in the various spaces where the human being circulates. And, in the end, it is History that tells “[…] the origins, genealogies, connections, what is retained. It is History that legitimises good causes and reports bad experiences” (Alves, 2016, p. 20, our translation).

In accordance with Peter Seixas (2017), the History that is told, namely in the classroom, may follow three distinctive courses. On one of the possible paths, it reinforces collective memory; that is to say it reproduces that which is considered the finest version of History with social and national, even nationalistic, intentions. In the second alternative, it fosters the learning of criteria which validate History with a more epistemological focus, based on two versions of the same fact. The final option refers to the understanding of the differences and similarities between narratives organising the past and which derive from distinctive groups, in addition to the way in which each one serves the present.

By following the first path referred to, those mentioned issues known as socially acute questions tend to emerge under the format of “[…] a set of ideas that basically limit thinking” (Moreira, 2018, p. 69, our translation), as they mostly represent a certain nation identity based on a type of identification, projection and symbolisation game. This leads to the creation of an apparently unique historical narrative, shared by a specific community and capable of mediating the achieved interpretation of the past (Wertsch, 2004). Such sensitive topics are therefore repeatedly and equally present in individual opinions, social representations, in the reports of students, in the voice of teachers (Legardez and Simonneaux, 2006).

By structuring the narratives told within the school context, instead of having historical learning highlight the importance of imagining the others and their place, of meeting multiple perspectives, of basing the arguments on the available evidence, of creating distress due to untruth or injustice (Lomas, 2011), historical learning will merely corroborate a national history which has been revisionist and softened, by covering or altering facts that are less positive and less encouraging of collective pride. Relying on specific markers which have not been deconstructed or discussed, this timeless and eternal history becomes a limiting factor of the understanding — real, logical, and enlightened — of the present and its political, social, ideological, cultural peculiarities, among many others.

In turn, both other courses suggested by Peter Seixas (2017) help to justify pedagogical and curricular experiences based on the reading of sources with diverging perspectives, on the separation between rational assumptions and merely emotional assumptions, on the counter-argumentation when facing other points of view, on empathy towards the others (Traverso, 2012; Barca, 2019), or even on the enlightened debate, always based on historical evidence, of the socially acute questions.

In fact, in order to “make personal commitment possible” (Alberti, 2014, p. 2, our translation), historical learning, namely when focused on more sensitive or controversial matters, must be based on a social, temporal and spatial perspective which will enable children and young people to recognise their role as citizens in the context of the current world (Moreira, 2018; 2020).

In the History lesson, it is therefore important to go beyond conveying the national narrative present in the collective memory, and to foster the development of essential historical thinking competences. This will make it possible for each citizen to become capable of understanding the past, in their time, of critically observing the present, where they move practically on a daily basis, and of designing potential expectation horizons (Rüsen, 2012; Seixas, 2017). The ultimate objective will translate into “prompting student reflection” (Alberti, 2014, p. 2, our translation).

Nevertheless, the emergence of a democratic and fully experienced citizenship (Lomas, 2011) also derives from knowledge that surpasses ethnocentric logic or collective oblivion, which shows the multitude of thinking lines and lines of action, and which contributes towards a historical consciousness which also enables the interpretation of matters that are disrupting or ethically more debatable actions (Rüsen, 2012). Herein lies the main role of the curricular component of History.

METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

Referring back to that which was identified in the first section, the main aim of this research work is to understand how national curricular guidelines for the curricular component of History, in the basic education of Portugal, handle topics known as sensitive.

It is important to highlight the connection of that greater objective with the curriculum field of studies right from the beginning. In fact, there is already a tradition in this area which is associated with the analysis of curricular components that mark the education system. In this area, authors like Kliebard (2004), regarding the north-American reality, and Goodson (1997; 2012) for the British context, are compulsory examples revealing the multitude of research purposes, strategies and dynamics. Although without the extension and complexity of their work, for the purpose of this research work it is worth highlighting how the authors include a historical analysis of curriculum. Although at a more modest level, this research also takes on that role by considering the learning goals known as Metas Curriculares and the key learning outcomes known as Aprendizagens Essenciais.

Additionally, the research purpose shows a position regarding research in education which moves away from the more classical logic centred in the hypothetical and deductive paradigm. In a different sense, based on a multi-reference theoretical frame, it is advocated that research “[…] predicts and stimulates new and creative possibilities of thinking and acting towards knowledge” (Duarte, 2021, p. 129, our translation). This means that, beyond assuming any methodological purity, it is currently more important to understand the various existing options and generate, through a bricoleur process, a valid research format grounded on a multitude of techniques that aim for a coherent strategy (Zipf, 2016).

In this paper, two structuring ideas have been highlighted for a better understanding of the considered options.

On the one hand, the peculiarities of a case study. As stated by Yin (2018), this methodological form has gradually become more recognised and legitimised as regards its relevance in the research area. On the other hand, various authors (Amado, 2014; Cohen, Manion, and Morrison, 2018; Yin, 2018) have highlighted that there is no unique way of conceiving it, since it may bear an effective multitude of characteristics, such as mostly qualitative studies, predominantly quantitative studies, unique case studies, multiple case studies, among others. That conceptual multitude also results from the definition of ‘case’ itself. In fact, “[…] cases are perceived as holistic entities which have distinctive components which act or operate in their environments” (Johnson and Christensen, 2019, p. 1107); in other words, the concept of case implies a wide range of possibilities: a student, a class, a school, a subject… For this particular article, the case is Portuguese Basic Education, namely the components including History: History and Geography of Portugal (2.° ciclo — 5th and 6th grades) and History (3.° ciclo — 7th to 9th grades).

On the other hand — and considering the observations of Amado (2014, p. 143, our translation): “[…] possible combination [of study cases] with other research strategies and different techniques for data collection and analysis […]” — it is relevant to emphasize documental analysis. On this topic, Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2018) consider that it is possible to establish another path to interact with natural data, emerging from daily operation. According to another line of thinking, Coutinho (2013) states it is an analysis strategy with the aim of contributing to an analytical research, based on content analysis.

By articulating such conceptions and adding the thinking of Bardin (2011), it is still possible to consider the documental analysis process under two key points. The first point refers to document typology; according to the author, the ones under consideration are known as natural documents, since national curricular documents3 included in the research are “spontaneously produced in reality” (Bardin, 2011, p. 45, our translation). The second point is related to the procedure under consideration, since we have followed the author's suggestion:

pre-analysis, inherent to the process of data organisation;

material exploration, for example associated with the processes of excerpt encoding and enumeration; and

processing of results, implemented in the following section.

The case study does not, therefore, emerge as a simple or easy methodological option (Yin, 2018). On the path to another logic, just as educational research in its whole, it may be considered “[…] an interpretative process of reality, enabling a more critical and reflective understanding of phenomena under study, granting them sense and meaning” (Duarte, 2021, p. 132, our translation).

As a final note, it is worth mentioning that such meaning does not eliminate the fundamental criteria of validity, which makes the developed analysis and interpretation more robust (Bardin, 2011). As regards this point, and based on the work of Amado (2014, p. 367, our translation), we have included three distinctive elements related to the validity of this study:

descriptive credibility, associated to the reliability of that which has been described by resorting to the systematic and transparent quotation of excerpts;

theoretical credibility, which relies on a constant dialogue with the presented conceptual framework; and

confidence, ensured by the “[…] rigorous description of the research processes used”.

DATA DISCUSSION

Based on the encoding process developed, it was possible to distribute the 1,148 curricular guidelines according to seven emerging categories, as they are connected to the theme under consideration. Some of them include their own subcategories, as illustrated in Chart 1.

Chart 1 Absolute frequency of the defined categories, after document encoding.

| Categories | Absolute frequency |

|---|---|

| Unrelated | 1.045 |

| Dictatorships and nationalisms | 42 (9) |

| Dictatorship of 1926/Salazarismo | 33 |

| Colonialism | 40 (4) |

| Economic exploration | 11 |

| Expansion and greatness | 7 |

| Cultural hybridism | 7 |

| Colonial independence | 6 |

| Slavery | 5 |

| Contemporary social problems | 7 |

| Religious relationships | 6 |

| World Wars | 4 |

| World War I | 3 |

| World War II | 1 |

| Resistance | 3 |

| Slavery | 1 |

| Total | 1.148 |

Source: Elaboration by the authors.

The vast majority of the guidelines (≈91%) does not bear any connection to the issues known as socially acute questions. It is therefore important to clarify two aspects. On the one hand, in the 5th and 6th grades, the subject under consideration includes a component of geographical education which initially does not have a direct connection to those topics, at least not in a more historical dimension. On the other hand, there is a set of indications that does not bear any connections to controversial or disruptive topics; still, its formulation does not show their exploration/problematization in that sense (for example, “characterising the Roman economy as urban, commercial, monetary and slavery” or “identify consequences of the application of the Stalin economic model”), which lead to its exclusion.

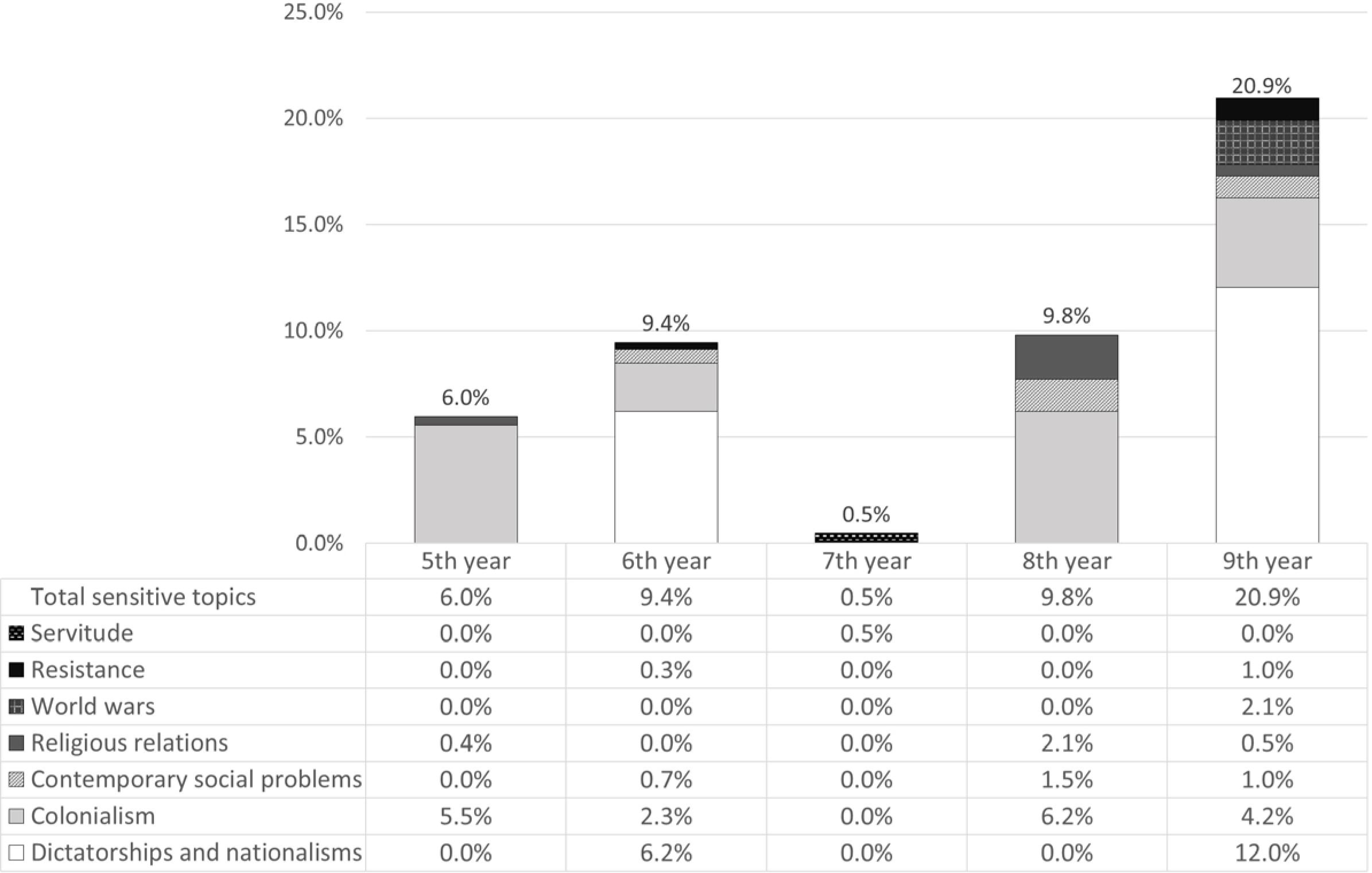

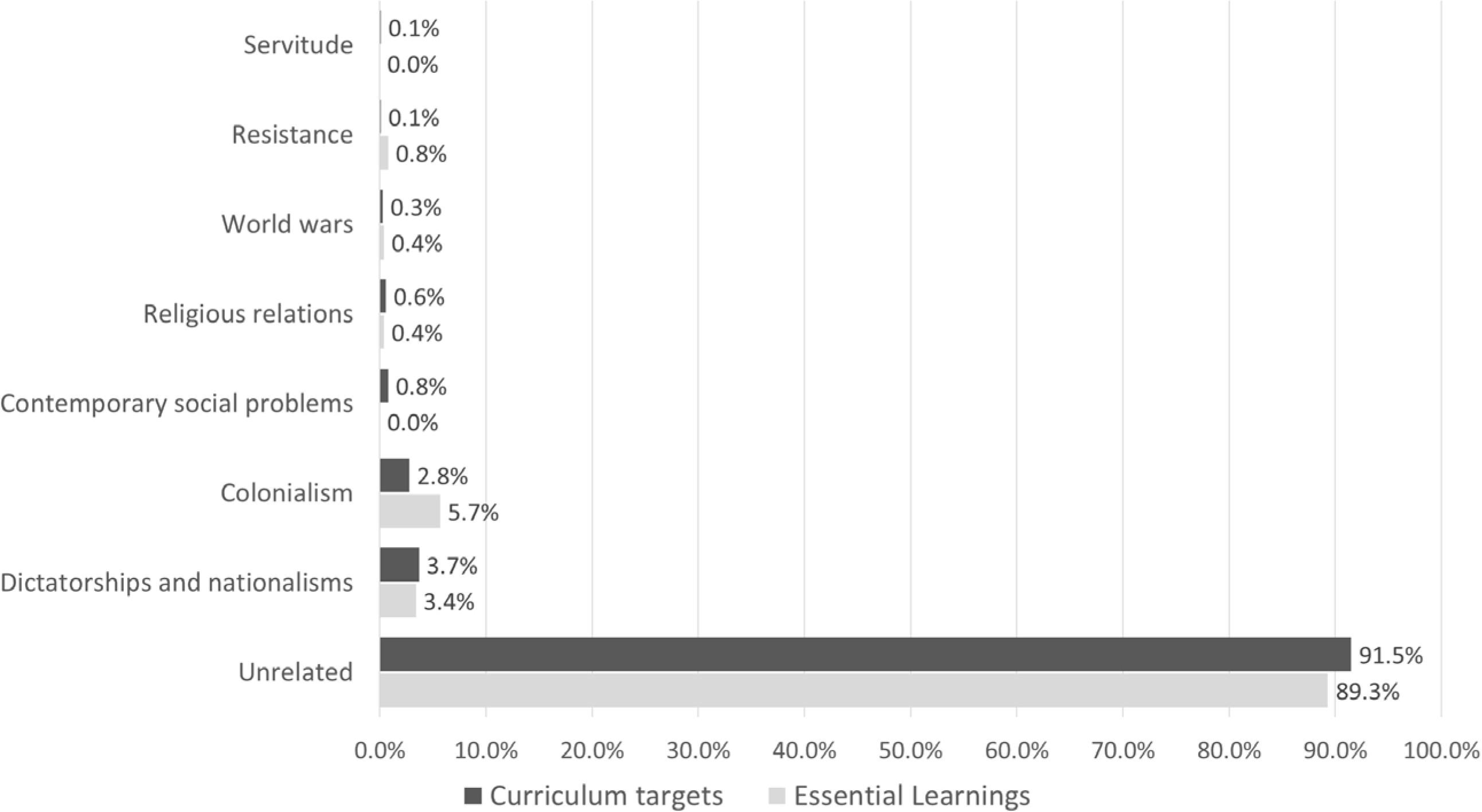

Before a more detailed analysis of each of the defined categories, it is important to consider its distribution in accordance with school year (Figure 1) and type of curricular document (Figure 2).

Source: Elaboration by the authors.

Figure 1 Relative frequency of each category defined by school year.

Source: Elaboration by the authors.

Figure 2 Relative frequency of each category defined by type of document.

By observing the charts, two ideas immediately stand out. Firstly, although there is a greater percentage and therefore greater diversity of sensitive topics to study in the 9th grade, there is not a simultaneous progressive integration through basic education, also due to the fact that the 7th grade shows a lower number of indications related to controversial themes. Moreover, the categories with greater expression vary every year, which makes it impossible to establish any regularity.

Secondly, it is visible that the most recent documents — associated with the current Portuguese curricular-normative period — show a greater percentage of guidelines referring to those questions, though that difference is not very significant (2,2%). It is worth mentioning that colonialism — extremely important in this context — is present in the documents in use with a more significant presence (5,7%). However, we have chosen a mostly integrated analysis based on the data emerging both from the extinct document (Metas Curriculares), and the one in use at the moment (Aprendizagens Essenciais), since the content referring to the focus of this research does not display significative differences.4 There will be three differentiating notes ahead.

We will now look at each set category (and subcategory) in greater detail.

The starting point may be the unique reference to servitude, separated from the colonial context: “to recognise the end of servitude in some European spaces as an important social and economic change” [M7]. Although it is exclusively a reference, it shows how to reflect upon servitude through historical learning, which is also contemporary. Nevertheless, this indication does not problematise the way in which that reality perpetuates, with specific contours, in different contemporary societies, with the choice being made for a reduction of the pedagogical approach to the emphasis on its extinction, which has only been recognised. This option seems to diverge from that which is stated by Torres Santomé (2017) and Burns (2018), since it is important that the curriculum contributes to the political agency of the students, which implies a critical understanding of society, and an inseparable awareness of social matters.

World Wars are present in three curricular references, and they are controversial topics due to the inherent causes, development and consequences. Regarding this category, the guidelines referring to World War I are based on aspects related to nationalistic and colonial tensions, which highlights the relevance of teaching History while crossing different perspectives of the same event, alongside the construction of a collective identity without interruptions. As regards this armed conflict, as in the case of World War II, the curricular texts thus clarify the need for students to identify the subsequent human and material losses, for a somewhat more empathic understanding of such topics, based on values of respect and solidarity.

Bearing the same absolute frequency, associations to resistance can be found. In the Portuguese context, this category is associated with movements of opposition which emerged during the period of the authoritarian regime known as Estado Novo. It is therefore possible to find a generic reference to the “internal opposition to the regime” [A9] and another more specific to the presidential candidacy of Humberto Delgado, in 1958 [M8]. There is essentially a suggestion of a descriptive approach of these two historical phenomena, without there being a wider study of the processes of resistance or such a phenomenon comes to bear multiform characteristics through time and even in contemporary reality. It would possibly make more sense that within this category it became possible to account for guidelines related to resistance movements born in territories under Portuguese domain during the authoritarian regime of the Estado Novo, as they are present in national guidelines. It would be a necessary pedagogical option for the development of that skill of placing oneself in ‘someone else's shoes’.

The category referring to religious relationships includes six curricular guidelines. Nearly all of these refer to the way the Inquisition “controlled heresy linked to the practice of Judaism, superstitions, pagan practices and different sexual conducts and the surveillance of cultural production and circulation” [M8] in Portugal. A reference to the catholic expansion which took place as a result from maritime expansion can also be found, and, in closer contact with current times, there is a reference to the “specific characteristics of ‘global terrorism’ associated to Islamic fundamentalism” [M9]. As is the case in other categories, there is a clear difficulty in promoting a reflection about religion within a wider debate with various historical, social and political implications.

Within the framework of current realities, the following category immediately highlights the connection between the teaching of History and present times and sensitivities. There are seven curricular guidelines related to contemporary social problems, namely the armed conflicts in the Middle East [M9], climate change [M8], gender inequalities [M6 and M9], or continuation of racism displays [M8]. Recognising contemporary contexts where there is a “disregard for Human Rights” [M6] thus becomes a clear option for students. In current guidelines, the logic underlying the promotion of an undeniable approach in the classroom seems to have acquired a different space. This occurs because the following were previously highlighted — ‘noting’ the “greater gender equality of the present, despite there still being a long road to travel” [M6] or the “permanence and universality of racist values and attitudes until the present day” [M8]. Now, however, a more proactive attitude is visible in order to “identify actions to undergo so as to find a solution or alleviate some of the social problems” [A6].

Such guidelines converge to what is defined by Alves (2016) and Barca (2019), for example by stressing the preponderance of a historic learning for a more problematising and enlightened understanding of current times.

On the topic of human rights, indications regarding colonialism have also been considered and these amount to a total of 40 formal guidelines. Although this refers to a different logic from that underlying the previous categories, it includes a higher number of examples and a more expressive approach. It is worth mentioning that in Portugal, as regards History, the economic exploration processes considered are not only related to Portuguese colonialism (for example, “separating ways of occupation and economic exploration implemented in Africa, India and Brazil by Portugal, while considering the peculiarities of each of those regions” [A8], but also to the Spanish one (“Characterising the conquest and creation of the Spanish Empire in America” [M8]). However, according to the formulation used, there seems to a preference for an essential descriptive consideration of the phenomenon, which seems to be partially deviating from that which is sustained by Torres Santomé (2017), when the author states the way school may affect the creation of anti-colonialist and antiracist principles.

This situation is also visible when analysing the curricular guidelines which partially underlie the perspectives of colonial expansion and greatness of the colonising nation. This somewhat questionable classification of greatness refers to distinctive areas such as the literary field (“Listing great literary work from the era of the discoveries known as Descobrimentos and their authors” [M5]), or technical achievements (“Referring the contribution of great travels for the knowledge of new land, populations and cultures, namely those of Vasco da Gama, Pedro Álvares Cabral and Fernão de Magalhães” [A5]).

While still on the topic of colonialism, it is important to highlight its connection to slavery, as a result of a certain type of economic exploration, which has already been previously mentioned (“To relate free and forced migratory movements (salve trade) with sugarcane cultivation and the mining industry” [A6]). As regards this subject, there is a descriptive/explanatory logic of the phenomenon and consequently curricular texts include transport and living conditions of slaves (“To characterise the life of slaves, stressing the conditions they were subjected to (from liberation and transport from the African continent to their daily routines in sugar mills)” [M5]).

Nevertheless, there is no future plan for History lessons at school to include learning about slavery from a higher level ethical dimension (Seixas, 2017), which would be essential for the development of reflection and critical thinking competences by the students. It would in fact be essential to the construction of an increasingly elaborate historical consciousness (Rüsen, 2012).

This absence is equally recognised when analysing examples related to process of decolonisation, which constitutes a social and economic portrait, detached from the underlying principles or human dimensions and, to a certain extent, politics: (“To succinctly describe the process of Independence of Brazil” [M6] or “Analyse the decolonisation process” [A9]).

Finally, the last subcategory related to colonialism was called cultural hybridism. Despite a reference to the need to “value cultural diversity and the right to difference” [A5], these are mostly a result of cultural expansion practices, through the “action of the Jesuit Order in education” [M8] or other processes of “exchange, acculturation and assimilation” [M8], the latter very much because of the “influence of contacts established or promoted by the maritime discoveries” [M5]. In this context, the rationality associated with cultures, which could be a dialogic and potentially enriching process (Silva, 2016) is limited to actions marked by a certain imposition of the Portuguese culture or miscegenation in their ethnic and cultural dimensions.

The final category is related to dictatorships and nationalisms (fa=43). Here there is a wide set of curricular guidelines which contribute to being able to understand and “describe the main characteristics of totalitarian regimes” [A9], particularly those in Europe, such as the dictatorships of Salazar in Portugal and Franco in Spain, Nazism, Italian fascism and Stalinism.

Despite considering this diversity of regimes, especially due to the aspect of human rights violation, for example the “racism and genocide” [M9] of the Nazi regime, the majority of curricular guidelines is centred on the Portuguese context, that is, the military dictatorship started in 1926 and the authoritarian regime known as Estado Novo (1933–1974).

Regarding the latter dictatorship, two relevant topics are highlighted. The first refers to the emphasis on the identification of “the main principles of the Estado Novo, namely the slogan of ‘God, Homeland and Family’ and obedience” [M6] and the identification of operating mechanisms of the regime, such as “the absence of individual freedom, the existence of censorship and a political police force, the repression against the trade union movement, and the existence of a single political party” [A6]. Within the topic of features of the Estado Novo, it is important to highlight the discussion of dimensions related to the difficult living conditions of the population, a result of the political and financial choices made by Salazar, or other repression mechanisms, such as “the prison camp of Tarrafal” [M6] for political prisoners. These guidelines lead to an understanding of the social repercussions of the Estado Novo, which is a topic of sensitive and controversial interpretation up to the present date. Nevertheless, in the previous guidelines there was a reference to the “identification of measures taken by Salazar to solve the financial problem of the country” [M6], which is not sufficient to problematise the then impoverished life of the Portuguese population, whereas at the present time the topic has been omitted and there is only a clarification of the relevance of the “process of implementation of the Estado Novo in Portugal, with an emphasis on the role of Salazar” [A9].

The second point in turn matches a specific historical matter, which is the colonial war. This armed conflict had a varied set of “human and economic costs, not only for Portugal but also to colonial territories, which is related to the refusal to decolonise” [A9]. It is important to highlight the fact that there is a reference to the implications of that war (be it social, economic, political or human, among others) not only for Portugal but also to colonised territories. This generates a study centred in the ‘foreign territory’, which means in “the guerrilla warfare and the support of local populations to the movements fighting for independence” [M6].

However, and as is the case with other categories, historical empathy (Traverso, 2012), which is so necessary, tends to be absent from these curricular guidelines. In another sense, the actual lived experience, that which was truly experienced first-hand by military forces, their possible anguish, desires, fears, conquests, is kept apart from the curricular text, which makes it more difficult to provide a more human understanding of the historical process. Apparently, that vision which shows “the effects of war, highlighting the number of deployed soldiers […] and the problems associated to war which persist to this date” [M6] may be surpassed by other wider and more localised points of interest, namely “the increasing popular opposition to colonial war and the lack of individual and collective freedom” [A9].

As regards ‘lapses’, this is not isolated. According to multiple authors (for example, Gimeno Sacristán and Pérez Gomez, 2008; Apple, 2019; Duarte, 2021), it is currently recognised that contents omitted from curricular options are as pertinent to the debate as those included in the guidelines. In fact, in the Portuguese national panorama, those referring to History seem to be in accordance with the work of Silva (2016), as they perpetuate considerable absences, namely the voices, speeches and perspectives of women, minority social and/or economic groups (such as Black, Indigenous people or immigrants) and also certain colonised populations.

This dimension does not just define the Portuguese context; to a certain extent, Torres Santomé (2017) identifies similar trends in the Spanish reality. It does, however, highlight the difficulty of including a pedagogical and curricular approach in basic education (from 1st to 9th grades) that effectively takes on the importance of including the study, the multi-perspective analysis and the debate of sensitive themes as a fundamental topic for the (citizenship and democratic) education of younger generations.

This analysis is equally confirmed when focussing on the competences of historical thinking that curricular texts encourage students to develop, either implicitly or explicitly. Further ideas on this topic will be summarised as follows.

According to the collected data, it is in fact possible to extend the analysis to that which is perceived as the approach of socially acute questions, based on principles recommended by research in History Education in basic education in Portugal.

The relevance of these painful and troubled past events seems to decrease, if studied and understood, in order to foster a wider understanding of current times and their different dimensions. If those are studied under the light of the values of those times, without consisting of a way to corroborate such practices and ideologies, it may be possible to then have

the motto for assuming a critical, argumentative thinking which can reconstruct certain unchangeable viewpoints and, therefore, for the understanding that the sense of citizenship, human rights and civilization in general have evolved. (Moreira, 2020, p. 102, our translation)

This means that in some cases, such as the omission of the fight of Black people for their rights in the United States of America, the occupation of the territory in Timor or the apartheid in South Africa, oblivion tends not to be fought against and may even favour undesirable revisionistic logics (Lomas, 2011).

With a clear emphasis on the multi-perspective exploration of historic events, the valuing of historic argumentation based on evidence (Barca, 2019), the assumption of empathic and rational attitudes (Alberti, 2014), the study of the more controversial matters must also take place, alongside an awareness of respect and the necessary acceptance of alterity.

Without any apologetic, ideological or dissonant intentions, it is thus possible to build and rebuild individual and collective memories which frame the identity of each individual (Lomas, 2011; Traverso, 2012; Gimeno Sacristán, 2015).

Finally, in an almost comparative reading of the two curricular documents under consideration, since the previous points are transversal, it may be possible to refer to three distinctive aspects:

a current option for less detailed explanations of the study for the classroom, which may be beneficial to freer, more diverse teaching, more focused on the real learning needs of young students;

the previous perspective, the perception of the use of verbs focussing on greater development of various competences, such as ‘summarise, ‘contextualise’, ‘note changes’ or ‘value’, and not so much on the accumulation of knowledge through nouns, to list ‘competences, knowledge and attitudes’ to be enhanced by students. Although it is apparently a minor detail, the way to face historic content will also depend on that formulation, whether it is more or less comprehensive, more or less problematising, more or less focused on reflective criticism (Moreira, 2020).

as a final point, a detailed note on the socially acute questions which can be highlighted on its own. As regards the maritime expansion in the 15th century, in curricular guidelines in use until 2021, the wording included ‘discoveries’ and the ‘findings’ of territories and populations; however, the current ones have replaced those terms by others which may be more carefully selected by their historiographic and human dimensions, such as ‘maritime expansion’ or ‘Portuguese exploration’. There is still the idea of ‘great voyages’ in one of the formulations, possibly by lapse. This particular topic, of the language referring to such a historic era, generates discussion and controversy (Torres Santomé, 2017), also linked to the continuation of a certain common legacy (Beyer, 2004). As such, it would not make sense to consider it random in this research work.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

As identified at the start, the aim of this research work was to understand the way national curricular guidelines for the curricular component of History in Portuguese Basic Education communicate with topics considered to be sensitive. It is important to highlight four central ideas from the analysis on the previous pages, which are essentially the main results of the study.

Firstly, regarding the period of the normative recontextualization of the curriculum, and within the context of curricular flexibility, Portuguese curricular documents have included guidelines that relate to socially acute questions, with a relative frequency of 8,5 and 10,7%, respectively.

In fact, when considering the established categories, for example colonialism and dictatorships and nationalisms, these have actually shown particular expression in two different school years (5th and 8th; 6th and 9th, respectively). This may be justified by the fact that the study of History in Portugal is still chronological (Moreira, 2018), starting from the Portuguese reality (2.° ciclo — 5th and 6th grades) to the European and world dimension (3.° ciclo — 7th to 9th grades).

In that context, although some subjects or points for analysis are undeniably absent, it has not yet been possible to understand that reality as an attempt to eliminate or hide the History that may be disturbing, hurt pride, generate uncertainty or even present a unique, linear and harmonious historic narrative referring to Portugal and the World.

There are, in fact, controversial topics that have been included — slavery, war(s), dictatorships… —, and this tends to go against any pedagogical curricular poverty situation associated with a lack of themes that generate a multi-perspective, and also a more curious questioning. In History, this belief in the existence of various viewpoints about one topic is increasingly considered a skill that can only be explored in the classroom (Barca, 2019; Moreira, 2020).

As a second point and following the previous one, it is important to highlight the set of areas of human life and various groups which seem to be studied based on superficiality. Facing the sensitivities of past and present, topics related to the feminine world, religious diversity, conquests (be it national or international) of ethnic and cultural minorities (the Romani people, Black people, Indigenous people…), oppression processes (political, economic, cultural, etc.), servitude and/or decolonization processes bear very little expression (or none at times). Alternatively, they are identified briefly and superficially, mostly marked by a logic of linear description. All of these topics are considered without focusing on the voices of women, cultural and religious minority groups, colonised communities or social agents involved in movements aiming to (re)conquer rights, the ontological reconceptualising of the human being and citizenship, the emergence of new communities and new countries, among others. Such a conclusion meets the ideas of Silva (2016), when he refers to a certain difficulty of curricular artefacts to include the mixed diversity of the social reality, which also limits the way students build their individual and collective identities (as men or women, as Portuguese citizens, as Jewish, etc.).

A third topic which is not entirely diverse from the previous ones, in their formulation, the analysed curricular guidelines do not show an effective impact on the awareness of the younger generations regarding the fact that much of History is made of human actions within a certain period or geographic and cultural context (Cooper, 2002). In fact, although there are examples of sensitive topics in the curricular texts under consideration, the underlying human dimension seems underrated, mostly due to the ‘invisible’ reflection on the actions of individuals and their consequences in the lives of each and every one, yesterday, today and tomorrow. In other words, curricular texts do not clarify in work to be developed with students that such topics, and others, refer to actions of real people, with singular lives, which have been won or lost, and which aspire(d) not to being hostages of a narrative that was not written or corroborated by them.

Finally, in both learning goals known as Metas Curriculares and the key learning outcomes known as Aprendizagens Essenciais, it was also possible to identify a trend to promote a more descriptive study — visible in verbs such as verify, identify, recognise or refer — which thus has more difficulty generating debate or considerations. When thoroughly followed, this option may separate pedagogical work from that historic discussion which enables an ethical, social and political consideration of the various contents, also consequently limiting the development of competences of historic thinking which are so pertinent, such as (counter-)argumentation, empathy, plural reading/understanding, for example.

Apparently, sensitivities go through diverse times — in this case, with dictatorships and nationalisms and colonialism being the ones that stand out — and do not set themselves as a predominant axis of curricular options, marked here and there by a type of distant look, which also does not generate space for the listening of other opinions, stories or cultures which are fundamental to a historic learning more suited to the 21st century.

Based on the research work carried out, we believe that, regarding the teaching of History, Portuguese curricular artefacts may be included in a more significant way in the references leading to pedagogical work based on the humanization and identity (re)construction of the agents involved, in the awareness and appreciation of human diversity (Duarte, 2021) and in promoting an increasingly more elaborate historical awareness (Rüsen, 2012). This will therefore lead to the teaching of History without avoiding the most difficult topics of a common heritage of Humanity, and creating room for wider and more complex reflections without revisionisms or simplifications. Although possibly difficult or controversial, these reflections are relevant to the creation of critical and responsible citizenship, marked by plural and diverse knowledge, which is the foundation of transnational and cosmopolitan tolerance, fundamental to aspire to a fairer world.

2The Portuguese basic education known as Ensino Básico is divided into three separate cycles: 1.° ciclo (from 1st to 4th grade), 2.° ciclo (5th and 6th grades) and 3.° ciclo (7th to 9th grades). However, in the 1.° ciclo, (Portugal) History is only studied in the last two years and it is not done so autonomously, as it is a part of the curricular component of Estudo do Meio (Social Studies).

3As explained in the Introduction, the documents emerging from the learning goals known as Metas Curriculares (2012–2021) and the key learning outcomes known as Aprendizagens Essenciais (2018–presente) were considered, totalling 1,148 curricular guidelines.

4Nevertheless, we point out that henceforth all excerpts of both documents are identified by initials — M or A — and by the number corresponding to the school year — 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th or 9th grades.

REFERENCES

ALBERTI, V. O professor de história e o ensino de questões sensíveis e controversas. In: COLÓQUIO NACIONAL HISTÓRIA CULTURAL E SENSIBILIDADES, 4., 2014, Caicó. Palestra. Caicó: UFRN, 2014. p. 1-11. Disponível em: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/17189. Acesso em: 25 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ALVES, L. A. Epistemologia e Ensino da História. Revista História Hoje, São Paulo, v. 5, n. 9, p. 9-30, 2016. https://doi.org/10.20949/rhhj.v5i9.229 [ Links ]

AMADO, J. Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2014. [ Links ]

APPLE, M. Ideology and curriculum. New York: Routledge, 2019. [ Links ]

BARCA, I. A controvérsia em história e em educação histórica. In: VERA, J.; FERNANDÉZ, J. (ed.). Temas controvertidos en la aula: enseñar historia en la era de la posverdad. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 2019. p. 497-511. [ Links ]

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70, 2011. [ Links ]

BEYER, L. Direções do currículo: as realidades e as possibilidades dos conflitos políticos, morais e sociais. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 4, n. 1, p. 72-100, 2004. [ Links ]

BURNS, J. Power, curriculum, and embodiment: re-thinking curriculum as a counter-conduct and counter-politics. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. [ Links ]

COHEN, L.; MANION, L.; MORRISON, K. Research methods in education. Oxon: Routledge, 2018. [ Links ]

COOPER, H. Didáctica de la historia en la educación infantil y primaria. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 2002. [ Links ]

COUTINHO, C. Metodologia de Investigação em Ciências Sociais e Humanas. 2. ed. Coimbra: Edições Almedina, 2013. [ Links ]

DUARTE, P. Pensar o desenvolvimento curricular: uma reflexão centrada no ensino. Porto: Escola Superior de Educação do Politécnico do Porto, 2021. [ Links ]

FREITAS, C. V. Flexibilidade curricular em análise: da oportunidade a uma prática consistente. In: MORGADO, J. C.; VIANA, I. C.; PACHECO, J. A. (ed.). Currículo, Inovação e Flexibilização. Santo Tirso: De Facto, 2019. p. 25-48. [ Links ]

GIMENO SACRISTÁN, J. El currículo como studio del contenido de la enseñanza. In: GIMENO SACRISTÁN, J.; SANTOS GUERRA, M. A.; TORRES SANTOMÉ, J.; JACKSON, P. W.; MARRERO ACOSTA, J. Ensayos sobre el curriculum: Teoría y práctica. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 2015. p. 29-62. [ Links ]

GIMENO SACRISTAN, J.; PÉREZ GOMEZ, Á. Comprender y transformar la enseñanza. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 2008. [ Links ]

GOODSON, I. F. A Construção Social do Currículo. Lisboa: Educa, 1997. [ Links ]

GOODSON, I. F. Currículo: teoria e história. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, B.; CHRISTENSEN, L. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2019. [ Links ]

KELLY, A. V. The Curriculum. London: SAGE Publications, 2004. [ Links ]

KLIEBARD, H. M. The struggle for the American curriculum, 1893–1958. New York: Routledge Falmer, 2004. [ Links ]

LEGARDEZ, A.; SIMONNEAUX, L. (coord.). L’école à l’épreuve de l'actualité: enseigner les questions vives. Issy-les-Moulineaux et Paris: ESF, 2006. [ Links ]

LOMAS, C. (coord.). Lecciones contra el olvido: Memoria de la educación y educación de la memoria. Barcelona: Editorial Octaedro, 2011. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. I. A História de Portugal nas aulas do 2.° ciclo do Ensino Básico: Educação histórica entre representações sociais e práticas educativas. 2018. 369 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) — Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, 2018. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. I. Para uma aprendizagem histórica: dos mitos aos desafios. História Hoje, São Paulo, v. 9, n. 18, p. 101-124, 2020. https://doi.org/10.20949/rhhj.v9i18.654 [ Links ]

RÜSEN, J. Aprendizagem histórica: fundamentos e paradigmas. Curitiba: W.A. Editores, 2012. [ Links ]

SAHLBERG, P. Finnish lessons 3.0: what can the world learn from educational change in Finland?. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

SALTMAN, K. J.; MEANS, A. J. Toward a Transformational Agenda for Global Education Reform. In: SALTMAN, K. J.; MEANS, A. J. (ed.). The Wiley Handbook of Global Educational Reform. Medford: Wiley Blackwell, 2019. p. 1-10. [ Links ]

SEIXAS, P. A model of historical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, Abingdon, v. 49, n. 6, p. 593-605, 2017. [ Links ]

STEINBERG, S. Curriculum? Tentative, at Best. Canon? Ain't no such thing. In: PARASKEVA, J.; STEINBERG, S. R. (ed.). Curriculum: decanonizing the field. New York: Peter Lang, 2016. p. 719-721. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T. Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2016. [ Links ]

TORRES SANTOMÉ, J. Sin muros en las aulas: El curriculum integrado. In: GIMENO SACRISTÁN, J.; SANTOS GUERRA, M. A.; TORRES SANTOMÉ, J.; JACKSON, P. W.; MARRERO ACOSTA, J. Ensayos sobre el curriculum: Teoría y práctica. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 2015. p. 141-147. [ Links ]

TORRES SANTOMÉ, J. Políticas educativas y construcción de personalidades neoliberales y neocolonialistas. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 2017. [ Links ]

TRAVERSO, E. O Passado, Modos de Usar. Lisboa: Edições Unipop, 2012. [ Links ]

WERTSCH, J. Specific narratives and Schematic narrative templates. In: SEIXAS, P. (ed.). Theorizing historical consciousness. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004. p. 49-62. [ Links ]

YIN, R. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. London: SAGE Publications, 2018. [ Links ]

YOUNG, M. Teoria do Currículo: O que é e por que é importante. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, n. 151, p. 190-202, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053142851 [ Links ]

ZIPF, R. A Bricoleur Approach to Navigating the Methodological Maze. In: HARREVELD, B.; DANAHER, M.; LAWSON, C.; KNIGHT, B. A.; BUSCH, G. (ed.). Constructing methodology for qualitative research: Researching education and social practices. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. p. 59-72. [ Links ]

Received: May 07, 2022; Accepted: November 04, 2022

text in

text in