Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.28 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub Oct 20, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782023280109

Article

Black/quilombola identity: intergenerational dialogues on self-naming in a community in the Northeastern sertão1

Maria Thaís Mota do Nascimento has a graduate in Pedagogy from the Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL). Pedagogical Coordinator of the State School of Xingó II (EEX-II). E-mail:maria.thais@delmiro.ufal.br

I , Writing – Original Draft, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3145-4676

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3145-4676

Suzana Santos Libardi has a doctorate in Psychology from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She is a professor at the Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL). E-mail:suzana.libardi@delmiro.ufal.br

II , Data Curation, Resources, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2185-6786

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2185-6786

IEscola Estadual de Xingó II, Piranhas, AL, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Federal de Alagoas, Palmeira dos Índios, AL, Brazil.

This work registers a research carried out with quilombola children, preadolescents and elderly people presenting the following topic: the construction processes of black and quilombola identities and self-affirmation. The research aimed to identify racial- and cultural-defined factors of these individuals’ identities; presenting the relations between racial identity and quilombola identity, in order to comprehend how such social constructions are related to each other and how they are managed by individuals from different generations. The research was conducted at the quilombola community Serra das Viúvas (Alagoas). A qualitative research was carried out with group workshops inspired by focal groups. A group of two elderly people and 37 children and preadolescents participated in the research. The results show generational factors involved in racial self-affirmation, as well as in being a quilombola, factors which were presented differently by young and elder participants.

KEYWORDS black identity; quilombola identity; generation; sef-affirmation

Este trabalho registra pesquisa realizada com crianças, pré-adolescentes e idosos quilombolas, voltando-se à seguinte temática: processos de construção e autoafirmação das identidades negra e quilombola. O objetivo foi conhecer alguns elementos raciais e culturais evocados por esses indivíduos, ressaltando as relações entre identidade racial e identidade quilombola, a fim de compreender como tais construções sociais se relacionam e como são manejadas por sujeitos de diferentes gerações. A pesquisa foi realizada na comunidade quilombola Serra das Viúvas (Alagoas). Trata-se de uma pesquisa de cunho qualitativo, com realização de oficinas inspiradas nos grupos focais. Participaram dois idosos e 37 crianças e pré-adolescentes. Os resultados demonstraram elementos geracionais da autoafirmação racial, bem como do ser quilombola, apresentados diferentemente pelos/as participantes mais velhos/as e mais jovens.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE identidade negra; identidade quilombola; geração; branqueamento

Este trabajo registra la investigación realizada junto a niños, preadolescentes, y personas mayores afrodescendientes, volviendo al siguiente tema: procesos de construcción y autoafirmación de las identidades negras y afrodescendientes. El objetivo fue conocer algunos elementos raciales y culturales de la identidad de estos individuos; evidenciando las relaciones entre la identidad racial y la identidad afrodescendiente, para comprender cómo estas construcciones sociales se relacionan y cómo son gestionadas por sujetos de distintas generaciones. La investigación fue realizada en la comunidad afrodescendiente Serra das Viúvas (Alagoas). Se trata de una investigación cualitativa con talleres inspirados en grupos focales. Han participado 2 personas mayores y 37 niños, niñas y preadolescentes. Los resultados demuestran cómo las personas vienen construyendo su negritud, desde la identificación de elementos generacionales de autoafirmación racial, además de ser afrodescendiente, presentados distintamente por los participantes mayores y menores.

PALABRAS CLAVE identidad negra; identidad afrodescendiente; generación; blanqueamiento

INTRODUCTION

When observing the profile photos of the children who are part of the WhatsApp group, we noticed that some of them use caricatures produced by an app. In the Dollify app, users provide information about themselves to create a character as similar to themselves as possible. We realized that the images used by the children do not present traits that are faithful to their true looks. The characters have light skin, straight hair, and other characteristics that, in addition to not resembling the children, are quite far from black racial identity.

(Passage from the authors’ fieldwork report)

The previuous excerpt registers our observation and concerns about the self-representation of quilombola children and preadolescents on a cellphone app. This episode instigated the execution of this study, which focuses on the construction of Black racial and quilombola cultural identities. By denying some qualities of their appearance and attributing to themselves characteristics that do not match their real physical appearances, are we observing a reaffirmation of the social valorization of the white racial standard? How does the racial factor relate to quilombola identity?

The situation occurred during the period of our virtual interaction with children and preadolescents living in a quilombola community in Brazil's northeastern sertão [semi-arid interior]. They were participating in field activities carried out in a university research-extension project1 that guided our encounters with them. The general theme of the project was the young people's perspective on their own community. During field activities, several other issues arose in comments by the participants related to the problem specifically addressed here. This study presents a profile of the data generated in the broader context of the project, which was carried out in 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic.

The objective of this study was to learn about racial and cultural elements evoked by children, preadolescents, and elderly from a quilombola community. Throughout our period of interaction with the community, some factors specific to that locality were presented to us by the residents, that show their feeling of belonging as a quilombola group. Some of these factors are cultural practices transmitted to new generations through various customs, beliefs, and activities, and memory is an important factor in this construction and transmission (Valentim and Trindade, 2011). Considering that the research participants were quilombola residents, we were also interested in identifying in their discourses relationships between racial identity and quilombola identity; to understand how these social constructions are related and how they are managed by subjects of different generations.

The research allowed us to discover how children and preadolescents perceived themselves, how they wanted to represent themselves and how they tended to neglect in their appearance characteristics associated with the Black race. An example of this is that, although most of the children participating in the project had curly hair, dark black skin, and other aspects that reveal their blackness, the girls (especially) drew themselves as girls with straight hair, light skin, and used beige crayons to color their bodies, etc.

Practices like these have already been reported by other researchers (Fazzi, 2012; Máximo et al., 2012; Oliveira, 2017; Silva e Vieira, 2018; Freitas, 2019; Oliveira e Mattos, 2019; Silva et al., 2020), whose work has highlighted how Black individuals, especially women, seek alternatives that distance them from their Black racial identity.

Máximo et al. (2012), for example, investigated the racial preference of children when they face issues involving beauty, morals, social aptitudes and competitive situations, in a public school in João Pessoa, Paraíba. The study had the participation of 161 elementary school students, who were shown photos containing images of Black and white children. The researchers use in their work the terms ‘white’, ‘black’ and ‘moreno’ [brown skinned], although the latter term is now widely considered to be inadequate for identifying race even if it is still quite present in everyday language about color in Brazil (Piza and Rosemberg, 2014). The objective of their study was for each child to say which photo he/she thought they was most similar in appearance to him/herself and to attribute to each of the children in the photos the conditions previously mentioned.

An example of the situation adopted was the researchers’ request for children to indicate, among the photos used, which they found the most beautiful, among other attributes. The participating children chose the pictures of white children as the most beautiful ones, and also as the most communicative and intelligent. In contrast, photos of Black children were attributed socially undesirable characteristics. In addition, the Black children participating in the research did not feel represented by the Black children in the photos, although they had similar phenotypical characteristics. The participants self-categorized themselves racially as white (Máximo et al., 2012). The study concluded that “[…] lack children generally have a negative emotional evaluation of their racial belonging” (ibidem, p. 521, our translation).

Fazzi (2012), for example, investigated the racial representation and self-representation of children and revealed different situations of discrimination and prejudice in the school environment. The study was conducted in two municipal schools in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Children between six and 14 participated in the research. During the interviews conducted by Fazzi, the children with black skin, when referring to themselves or their peers, used the terms moreno/a [brown], moreno/a-claro/a [light brown], among others, and related the terms preto and negro [which both mean black] to socially undesirable characteristics, such as ugliness.

Acts of poor conduct, such as theft, were also associated with blackness. In the interviews, the researcher also used, among other resources, the ‘robbery game’. In this context, a hypothetical situation was mentioned to the children, according to which two dolls, one white and one non-white, had been robbed while walking home. The children were then shown two dolls that had very similar physical characteristics: they were the same size, wore the same type of clothes and shoes and wore the same hat. The two dolls were differentiated by their skin color; one was white and the other non-white. The children, at the request of the researcher, had to choose which of the dolls shown would represent the thief in the game. Most children associated the role of the thief with the non-white doll.

These situations highlight aspects of the process of racial identity construction in children, and have also been found in studies with youth (Paulino and Mattos, 2021). Considering, therefore, that these attempts to come closer to the socially valued white racial identity can occur in different periods of an individual's life, in this study we consider individuals from different generations.

Although the elderly, preadolescents and children involved in this study live in the same community and experience daily events in common, it should be emphasized that the identity and racial construction of each one is particular and also permeated by other social markers, such as generation/age, class, gender, and level of education. Given the generational factor, the way children experience the reality of racism in which they are inserted is different from the experiences of youth, adults and the elderly regarding this same reality. These factors are therefore essential in racial construction, since talking about identity involves the way each individual perceives him/herself and is perceived in a given sociocultural context (Oliveira, 2017) during life.

The racial dimension reflects a concrete example of this construction, since race is a social category (Munanga, 2003) experienced through collective influences, to which different representations and meanings can be attributed. Based on the structural racism of our society, the historically shared representations about the Black race are mostly negative. This can thus produce a subjectively arduous process for the Black and brown population, which makes it difficult for individuals to positively affirm their own racial identity.

Thus, the research presented here is important, given that the racist context imposes violence on the construction of Black identity; violence that must be denounced. Based on the convergences and divergences presented by the participants — children, preadolescents and elderly quilombolas —, we were able to identify important generational elements of the racial self-affirmation process.

This is a qualitative study, whose methodology included workshops based on focus groups. The workshops initiated some activities carried out with the participants. In the following section we will present our encounters, as a university team, with the participating community and the method adopted in the research.

TO BE IN THE QUILOMBO: PROMOTING ENCOUNTERS

Being in the quilombo enabled an encounter of alterities, between us, non-quilombola adults, researchers and extension workers, and the quilombo residents, children, preadolescents and elderly. Our research-extension team included Black and white people, undergraduate students and a university professor. The racial issue obviously permeated the encounter and marked our view of it. In addition, the generational position of all those involved was also important and had to be considered in all research contexts, especially in research with children (Pereira and Nascimento, 2011).

Although all of the researchers were adults, the relationship that the children and preadolescents developed with the second author of this paper was affected by hierarchical issues related to teaching, which resulted in less interaction. Because she was a university professor, it was evident that some participants considered her to be in a position of authority in relation to the other researchers, despite our best efforts to minimize this hierarchy by using horizontal practices. In contrast, some participants felt comfortable to exchange more with the first author and other team members (non-teachers) in the proposed activities and to build ties that went beyond what was proposed in our meetings, such as invitations to dance. Some of the girls participating in the project, who were preadolescents, brought up more intimate subjects in informal conversations, such as dating, and aspects related to sexual orientation and sexuality.

For each researcher, the racial issue is present in our relationship with the research carried out from the places we occupy. For the first author, a Black woman, this work touches on reflections regarding her relationship with herself, since it discusses issues she experienced herself throughout her personal life, which were also perceived in some experiences of the participating children and preadolescents — such as straightening the hair and other subtle actions related to the image of young Black women in Brazil. For the second author, a white woman and supervisor of the study, approximation to the racial theme has introduced her to racial literacy, to white privileges due to color, and has encouraged her to pay attention to the role of whites in the problematic of race relations.

The older residents who participated in the research explicitly identified themselves as Black during our interactions, and in their conversations with the children and preadolescents during the field activities. The racial self-identification of the younger participants was contemplated in a way that would not steer responses — and which is presented below — in an effort to listen to their perceptions of themselves at that time in their lives.

We were always careful to avoid reproducing in the fieldwork possible symbolic violence to which these quilombola populations are already exposed to in their daily lives, and to use research strategies and procedures to develop a positive sense of Black identity and image among the young. These aspects must be increasingly problematized in childhood studies, and are also important for thinking about ethics, in a broader sense, in research with children (Prado and Freitas, 2020).

ABOUT THE TERRITORY AND FIELD ACTIVITIES

The study was conducted in the alto sertão region of the state of Alagoas. In general, the quilombola communities in this region of the state are still experiencing the impact of the historical processes of colonization and deterritorialization (Farias, Nascimento, and Botelho, 2007) that affected their ancestors. This means that they are poor and working class communities that seek formal social recognition — the vast majority of communities in the region are not legally recognized as quilombos — and gain little attention from the state and a minimal provision of the basic services to which they are entitled.

The quilombola community Serra das Viúvas is a rural Black community (Souza, 2015) located in the rural portion of the city of Água Branca, approximately 3 km from the urban area. Due to its location, in the hill region of the municipality, there is a certain difficulty of access (Figure 1), especially in rainy periods.

This community was certified and legally recognized by the federal government's Fundação Cultural Palmares as a quilombola community in 2009, and now has about 226 inhabitants, in 86 families (Souza, 2020). The income of these families comes from the sale of products from family farming, animal husbandry, social programs that benefit the community, such as the Bolsa Família [Family Grant] Program and the National Program for Strengthening Family Farming (Pronaf), as well as the social security pensions of elderly residents (Alagoas, 2015).

Many male youth and adults from the community migrate seasonally to the South and Southeast of the country in search of employment, mainly in construction, to provide income for their families. Another source of income in the community is related to handicrafts (Figure 2), an activity in which women are engaged to provide a source of non-fixed income (Pérez et al., 2020).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2 Children and an older resident of the community making crafts with licuri.

The handicrafts are made from raw material extracted from the community itself: the licuri (or ouricuri) thatch. The making and sale of handicraft products — hair bands, hats, bags, table decorations, puffs, napkin holders, among others — is managed by the Association of Quilombola Women Artisans of the Serra das Viúvas (AMAQUI), which was registered in 2010.

The children of Serra have access to a municipal school located in the community itself, which was inaugurated in 2002. The school is a multigrade elementary school, which requires children and adolescents to move to other schools in neighboring communities or to the urban area as they advance in their education. In the Serra region there is also a Catholic church, several fields for planting and two community manioc flour mills. According to the participating children and pre-teens, residents divide themselves geographically for the use of these flour mills. In addition, the community has several cisterns for capturing and storing rainwater. Since there was no piped water in the community until that moment, the water consumed came from the cisterns, water tankers and local springs (Vieira et al., 2019).

The first formal contact of the research project with the community took place during an AMAQUI meeting. Our trip to the meeting was scheduled in advance with the community leaders. We took advantage of the date of the Association's regular meeting to present our objectives to the mothers and grandmothers responsible for the children and adolescents living there.

At the time, we observed a decision-making process by the women about the choice of color for the Association's new T-shirt. We noticed that the arguments presented were based on their skin colors, since the understanding was that the choice of color for the T-shirt should consider, in some way, the skin color of those who wore them. The yellow color, suggested during the meeting, was not well accepted by some members, who claimed it was not a color favorable to morena [brown] skin. Some of the women there felt certain colors would not be welcome because, when associated with their skin tone — some have dark black skin — they would not be appropriate and/or pretty; they would look good only when worn by white people. Other colors were suggested for the T-shirt, and the debate about its contrast with skin tones expanded beyond the initial task of choosing the color for the Association's new T-shirt.

In the dialog, some participants described themselves as morena [brown], negra [black], and white, among other terms, and this information was viewed as important for the aesthetic decision of the group. After some time in discussion about skin tone and what would or would not be pretty, it was very interesting to notice that the issue was concluded with an attitude of self-valorization by one of the members, who said that the color of the shirt was secondary, claiming that any color “would look beautiful” on her and minimizing the importance of the debate about skin color. She was applauded by her companions. This discussion was related to the tension that pervades the process of racial self-identification for Black people, including among adults — and how this can reverberate in the construction of children's racial identity.

In the remainder of the meeting, we suggested that the children be invited to participate in biweekly meetings in the form of group workshops, during which we would carry out activities that addressed the quilombo and specific aspects of childhood and adolescence in that community. We made the schedule considering available days and times to fulfill the formalities of the project.2

In addition to consent from the guardians, we were mainly concerned with the acceptance of the children and preadolescents themselves, and whether they would be interested and engaged in the proposed activities — as discussed by Prado and Freitas (2020), who warn that their consent should be attained with care through the procedures adopted at the beginning of and throughout the intervention. When they were invited, they were duly informed about the objectives of the project, which were further detailed on our first day of group activity with them.

Children and pre-teens aged between four and 12 years participated in the 11 workshops, totaling 37 young people involved in the activities carried out, 25 girls and 12 boys. On average, 15 children and/or preadolescents participated regularly in each workshop. Irregularity in attendance was due to the times of the activities. Although the plans were based on the participants’ and project executors’ availability, our trip to Serra depended on transportation provided by the university, which limited the flexibility of scheduling.

Thus, depending on the time, some children and/or preadolescents could not participate, either because they were in class at school or because they were involved in personal demands. In addition, on the days when we held workshops in the morning, the community school teacher released the class to participate in our activities; at first, at the request of the community leadership, later, at the request of the children themselves — according to the teacher. Thus, the number of participants in the workshops varied. This data illustrates engagement in the workshops, although we know that the number of participants does not necessarily guarantee qualified participation.

The meetings took place at the AMAQUI office, a place provided by the community leaders. However, a few times we were invited by children and/or preadolescents to outdoor activities, such as walks (Figure 3), for example. We adopted a flexible approach to our planning and activities, so that the interests of the participants were given priority regarding games, customs, places where they wanted to be and/or show us, etc.

The planning of each workshop was based on a written program. As mentioned, this planned script was always subject to changes and improvisations, depending on the demands raised by the participants. Each script addressed a central theme — the focus of the meeting — and suggested specific activities, a list of materials needed and the time allotted for each activity. Conversation circles, reading and textual production, drawing, and games were carried out and dialogues with the older subjects (initiated as interviews) were mediated by the children and preadolescent participants themselves. The type of focus group helped guide the workshops, with the aim of hearing and registering the participants’ views on the topics discussed. These activities are detailed in the following section, where we present them together with the participants’ discourses in these research contexts.

During the 11 meetings, the activities carried out in the workshops allowed us to:

get to know the children, preadolescents and their families;

get to know some older people in the community and stories they told about their childhood;

understand the sense/significance of quilombola identity grasped by the children, preadolescents and the elders;

promote intergenerational dialogues about childhood experiences of the past and present;

discuss stories that thematize racial identity; and

create a dialogue between quilombola children and preadolescents from different communities.

The theme of Black/quilombola identity appeared specifically in the workshops where older residents were present. We noticed that their comments were directly related to the discourse of the young participants. Thus, the intergenerational character of the research grew in importance, so that the dialogue between generations revealed similarities and disparities between the perspectives of the elderly, the preadolescents and the children. Among the elders, two residents participated, a man and a woman, who were the grandparents of four children who were frequent participants in the workshops.

At the end of each workshop, we prepared a field report containing a detailed description of the activities conducted in the community and, mainly, of the participants’ voices and opinions on the topics covered.

In the following section we describe the most important situations that occurred in the group, either only with the children and/or preadolescents, or involving the elder participants. The most pertinent excerpts and situations presented in the reports were selected to promote a reflection on the construction of racial identity from a generational perspective.

INTERGENERATIONAL DIALOGS OF SELF-AFFIRMATION

In this section, we present the reflections that emerged through the fieldwork in the quilombola community mentioned above. The data are grouped into two subsections, which deal with Black and quilombola identity, respectively, from the perspective of the participants. First, we highlight how the theme of racial identity was portrayed in the community by the children and preadolescents. Then, we present its relationship with quilombola identity, as defined by participants from different generations.

DISCUSSING BLACK IDENTITY

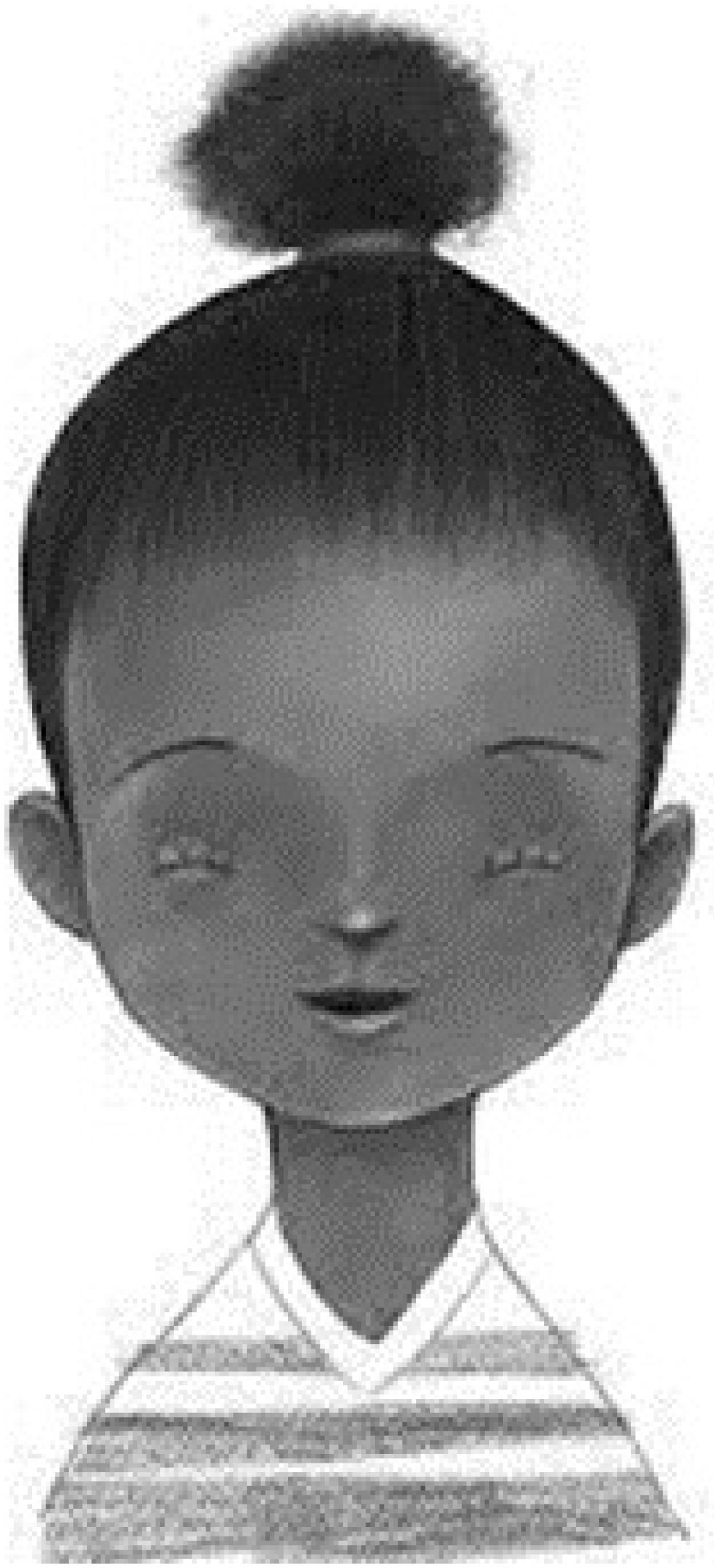

In one of the workshops, aimed at discussing stories that thematize racial identity, we had the participants read the book A Cor de Coraline [Coraline's Color], by Alexandre Rampazo (2017). The book problematizes “skin-colored” pencils, while simultaneously reflecting on racial identity and representativeness. Using illustrations, the book's content the is presented by developing suspense around Coraline's true skin color. The suspense worked to our advantage. At a strategic moment in the narrative, we paused the reading and proposed that the children and pre-teens try to discover the protagonist's skin color. We provided each of the children with pictures of the character (without color), as found in the book, as well as coloring materials — colored pencils, crayons, felt-tip pens — and watched as the activity unfolded.

While conducting the task, we noticed that the children and/or preadolescents changed their minds and had doubts about which color to use. At one point, one of the older children looked at the book cover (Figure 4) and, seeing Coraline's curly hair, said that the character should be brown, because “look at her Black person's hair” (excerpt from authors’ fieldwork report, 6th workshop).

We did not necessarily perceive a negative tone in the way the statement was made. For the participant, thinking about Coraline's skin color triggered another phenotypic factor: hair texture. Most of the women with whom the participants interact with in the community are Black and have kinky or frizzy hair, causing not only this girl, but also others, to associate Coraline's hair texture with her skin tone — which is also related to the complex social processes of racial identification in Brazil, where color, other factors of appearance and social markers are considered, composing aspects of discrimination in the complex social dynamics of racism (Gomes, 2020).

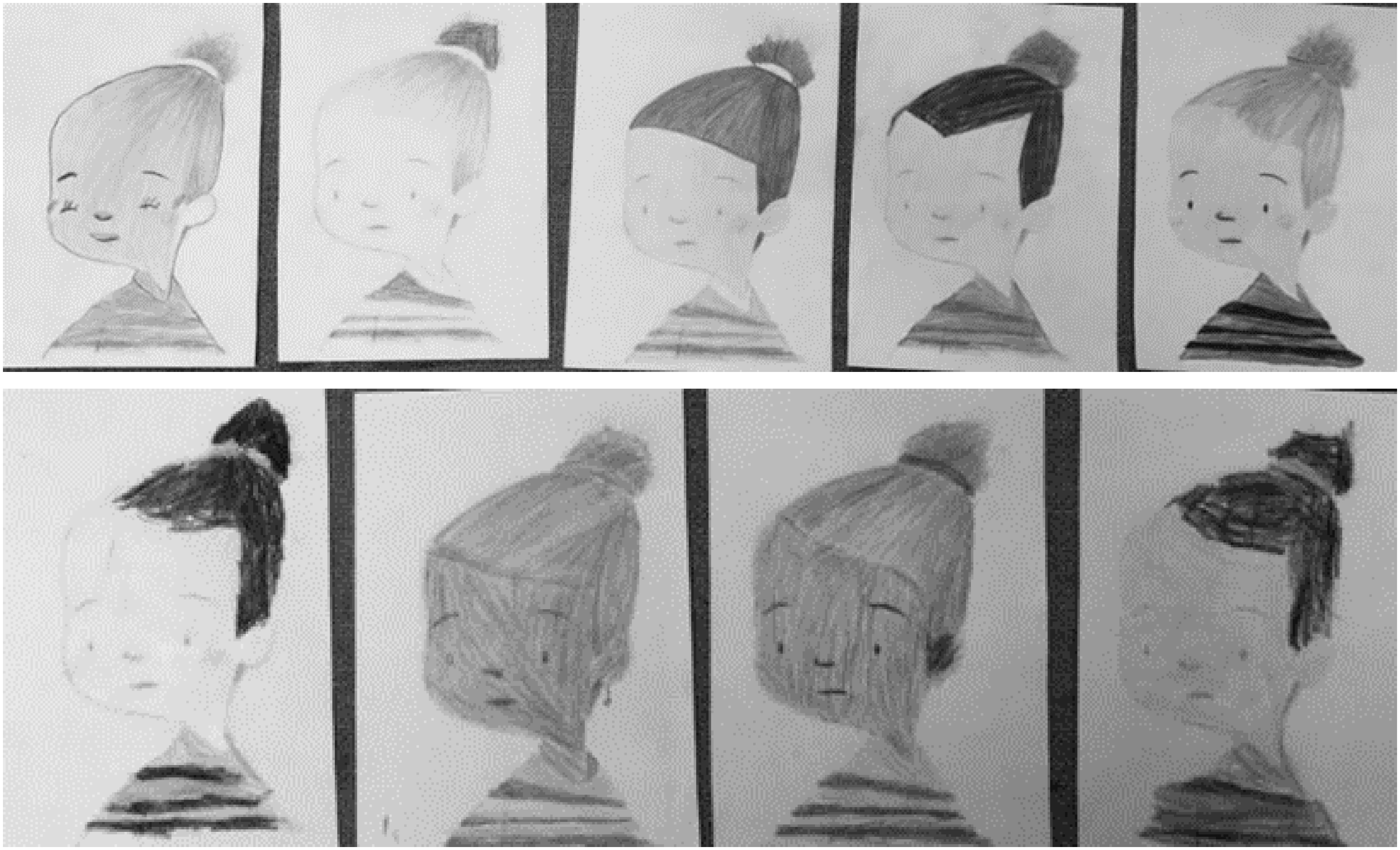

However, despite the association of hair and skin color, at the end of the activity we noticed that the children expected the protagonist to be white. We used guided drawing by the group to have them reveal what they believed to be the character's color: most painted Coraline with a very light skin tone (Figure 5). This may be due to the limited representation of Black people in children's books and stories (Sousa, 2001), and to lack of access by these children to literary works with Black characters. In addition, in the audiovisual productions to which children have more access — telenovelas, films, cartoons — Black people are mostly portrayed as supporting or secondary characters.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 5 Some of the assignments produced by the participating children and preadolescents.

The common use of colored pencils also interfered considerably in the outcome of the activity: the choice of color used by the children to paint Coraline was affected by their daily habits. Most of the children used a beige crayon, claiming that it was the “skin-colored” crayon, as described in the following excerpt:

L.3 looked at all the other children's drawings and began to color his own, coloring Coraline's skin in beige (with what is better known as a “skin-colored” pencil, the one the children used most often to paint her). A member of the university team, thinking that he [L] was using that color because he saw the other children using it, said his was also pretty and asked if he thought that was Coraline's color. He said yes, “because that's the color of skin”. Even though his own color is Black, he said that the crayon's beige was the color of skin (excerpt from the authors’ fieldwork report, 6th workshop).

We observed an absolute naturalization of the idea that there is only one skin color, and only one colored pencil to match it. This naturalization highlights the way whiteness came to be constituted in Brazil and how it continues to be represented and accepted socially as the standard of humanity (Bento, 2014). As a result of this standardization, there are phenotypes that are more or less valued in our society (Oliveira, 2017), so that whites enjoy the beneficial effects of the positive status associated with their color. This helps explain why, until recently, many Black Brazilians of different generations tried to neglect traits that showed their Blackness, so as to avoid the “other's” negative, racist gaze. Paulino and Mattos (2021) found similar results when conducting workshops at a school, where, in the context of a group of Black students, the “skin-colored” pencil was also more highly valued, as well as phenotypic traits, of the mouth, for example, associated with white people, who are seen to be “more beautiful”.

We believe that the school institution may be responsible for the understanding shared by children about the name and use of the “skin-colored” pencil. Many of us learned at school that the beige pencil refers to skin color, which shows that, although the school is a privileged environment where aspects related to racial identity can and should be discussed and problematized, it is possible to perceive that these same institutions often reproduce and highlight the valorization of a white, Eurocentric aesthetic standard (Cavalleiro, 2001).

This valorization can be seen in the practices that are adopted, or not, in schools. Romão (2001) points to the way in which the participation of children in Afro-Brazilian culture is affected, given the choice of the institution not to include in its curriculum practices that provide this participation, such as capoeira and dancing in samba circles. Not being culturally represented in the school environment can make Black children more vulnerable to having greater difficulties in accepting themselves as Black.

This reality also influences affective relationships in the classroom. White children often receive more praise, incentives, affection, and hugs; the opposite occurs with Black children, for whom manifestations of affection are not shown in the same proportion so as to make them feel as loved, accepted, and welcomed in the school environment (Cavalleiro, 2001). As a result of attitudes like this, the processes of self-acceptance, inclusion and, consequently, participation are more complex for Black children and/or adolescents, when compared to incentives and agency among whites (Abramowicz and Oliveira, 2012).

In addition, there is a culture of silencing on the part of teachers and other education workers — administrators, coordinators, food workers, security guards, among others — regarding discriminatory practices against Black people. Many educators still carry the conception that racism is non-existent in the school environment (Santos, 2001; Cavalleiro, 2020). Those educators who do consider it as a reality to be combated often reinforce the mistaken idea that racism is a problem that is exclusive to Black students. Thus, these young people are encouraged to be resistant to racism — which is important too — but not sufficient, nor effective in creating the means to combat racism and discriminatory practices in institutions (Santos, 2001).

Returning to the activity, at the end of the reading session we showed the children the book with the illustration of Coraline with her real skin color (Figure 6). Upon seeing the image, some of the children and pre-teens were surprised. One of the girls even said there is no one with Coraline's color. However, in the community where they live, there are people — including the children themselves — with a black skin tone even darker than that of the character. The questioning reveals, in our view, a sense of unfamiliarity that is felt by the children when encountering a Black protagonist; which reinforces the importance of representativeness for racial affirmation processes among children (Sousa, 2001).

The discussion about skin color was also present in other workshops. To create a space for dialog between the youngest and the oldest residents, we proposed an activity in which the children and preadolescents portrayed their grandparents by making puppets. The moment of handing over the dolls to the respective grandparents provided an opportunity to invite them to participate in future workshops. Among the elders, the children chose to represent those who had the most grandchildren participating in the workshops. We identified four grandmothers and two grandfathers. To make the dolls, the children were divided into subgroups; each made two dolls. We explained that the dolls should be as similar as possible to the people they represent and distributed the materials we had brought with us: plastic bottles, crepe paper, A4 sheets of paper, felt pens, pencils, scissors, glue, adhesive tape, painting materials, and others.

In one of the subgroups, a discussion about race emerged during the initial choice of color to represent the skin color of the grandparents’ dolls, as described in the following excerpt:

The workshop facilitator asked about the color of the grandparents, and they were categorical in stating that A. and N. are brown [pardo]. At that same moment of making the doll, A. passed by the front of the Association building and was soon pointed out by the group. A. is black, has very dark skin, but the children chose to say it was brown. Regarding the choice of the color of representation of Mrs. N., one of her grandchildren took the lead of the group and made a series of proposals, among them: to use white paper for the color of his grandmother and paint her eyes blue (excerpt from the authors’ fieldwork report, 2nd workshop).

Reflecting on what happened, we asked ourselves why the participants made such choices. The group represented the grandmother in a way that was clearly divergent from her real physical characteristics, portraying her with traits completely distant from a Black racial identity (similar to what occurred in the situation presented at the beginning of this article), always opting for light colors that do not correspond to reality, but to the socially valued whitening.

The same children and pre-teens represented the aforementioned grandfather with features that were faithful to his appearance. The puppet, in fact, represents the man who passed in front of the Association during the workshop. However, when naming the grandfather's color, the children used the term ‘brown’ [pardo]. They may not be aware of the formal categories used in Brazil to identify color, and used the terms embedded in the informal everyday discourses to which they have access. Moreover, because there are various racist terms that belittle Black racial identity, children and preadolescents may have used ‘pardo’ because they recognized it as an appropriate term to refer to Black people.

We noticed, at other times, that the children were careful not to express racist attitudes and speech, such as during the workshop in which we encouraged an exchange between them and children from a quilombola community located in Campos dos Goytacazes, Rio de Janeiro. They prepared a slide show for us with pictures of themselves and their community.

When the photo of some children from this community appeared on the slide, slightly positioned with their backs turned to the camera, one of the participants from Serra said with surprise: “Ohh, the hair…” (referring to the kinky hair of one of the girls in the photo), and did not finish the sentence, but we realized that she was going to say something negative about the girl's hair. The other children realized this and, when they heard their colleague, they immediately rebutted: “What prejudice!” (Field report no. 6). They spoke loudly, scolding her.

It was evident that the children were careful not to use pejorative terms when referring to Black people and/or Black phenotypic characteristics. This was either because they understood the negative and violent impact of racial discrimination, or because they were instructed in that sense by their school or family, or because they themselves had already experienced situations that placed them in a place of inferiority based on their color/race.

DISCUSSING QUILOMBOLA IDENTITY

Regarding quilombola identity, it was possible to perceive a disparity in the discourses of the different generations. The older residents were interviewed in the workshops by the younger ones and by us, the university team. These were the intergenerational dialogues that took place in person in the context of the project. The focus was on quilombola identity and the experience of childhood, past and present.

We asked them what ‘being quilombola’ meant. One interviewee said that “to be a quilombola is to be Black” (excerpt from the authors’ fieldwork report, 5th workshop), revealing that she saw a great proximity between her racial identity and the quilombola identity. Another person related “being quilombola” to cultural elements, respect and traditions, not directly mentioning racial aspects.

B. stated that being quilombola is tradition, “it is having respect for what you are”, and that many people wanted to be quilombolas too, to also be respected. [He said] That only today does he recognize himself as such, because earlier he did not recognize himself in this way; today, with this culture, he affirms himself as a quilombola (excerpt from the authors’ fieldwork report, 7th workshop).

In other workshops, when we proposed that children and pre-teens list aspects related to “being quilombola”, they pointed out actions that were strictly linked to community tasks and handicrafts. At the end of the activity, we obtained the following list:

It is to be recognized in places. People from outside come to know the community; it is to work with vines;

it is to work with thatch, to weave products, brooms, hats, bags, straw wallets; it is to be recognized by law;

it is to dance Afro-dance, capoeira; because you learn a lot;

it is to value yourself. (Excerpt from the authors’ fieldwork report, 4th workshop)

Although the comments of the youngest participants refer to valorization and recognition, most of their responses are defined by what they do in the community. The discrepancy between these statements and those of older people may be due to the collective experiences of each generational group, among other factors.

The oldest participant shared with us his lifelong hesitation to call himself a quilombola. Having closely experienced their people's struggles and resistance — growth, the struggle for community recognition and subsequent access to specific public policies —, older people can more easily associate their quilombola identity with the local historical process, its advances and setbacks in recognition and access to public policies for quilombos. Although the children and preadolescents live with the consequences of these political struggles, and disputes in the territory are present today, they did not cite aspects of the collective struggle, but associated being a quilombola with the practical tasks they perform today in the community.

Meanwhile, we noticed from the list that, in some way, children and preadolescents also spoke of recognition, although they did not raise it as something to be sought. For them, recognition appears as something already given a priori. Similar results were found by Valentim and Trindade (2011). Children and preadolescents evoked the idea of recognition associated with a duly formalized recognition (through laws that guarantee their rights as a traditional community), or recognition that comes from the other — quilombola or not — when perceiving their people as quilombola.

We thus note that recognition is qualified differently by subjects of the older and younger generations. Despite this, both identify it as a central aspect of the definition of quilombola identity.

With regard to the list produced by the children and preadolescents, the girls were the protagonists in its elaboration. In the community, they are strongly engaged in artisanal work, unlike boys. Thus, their definition of themselves as quilombolas was influenced by their daily chores, which are socially organized in the locality based on a gender division.

The relationship between quilombola and racial identities is also revealed by both generational groups. As described above, one of the older residents directly associated race and culture, although we know that not all older residents claim to be Black. In the discourse of the children and preadolescents, we identified this association when, at the opening of a workshop, we asked them, as we commonly did, to recall the previous meeting, in which we had met quilombola children from another community. When describing them, they incisively affirmed that “they were Blacks” (field report no. 7). When they recalled the children from another quilombo, this was the signifier evoked by the children and preadolescents from Serra. When referring to themselves, during the months of our coexistence they did not use any term that directly defined them as a racially delimited people, but, when talking about other children, this marker was present. This does not necessarily indicate an attempt to distance themselves from their Black identity. Because they had seen the children from the other quilombo only once, in the photos, their physical appearance and, therefore, their skin color was one of the few references they had to describe them, since all the children who appeared in the photos had dark black skin. On the other hand, very few children and preadolescents from Serra have this skin tone. Thus, given the non-homogenization of the skin color of its population, it was reasonable for the younger ones to characterize themselves based on community activities. We understand that this points to a sense of collectivity involved in quilombola identity, and simultaneously situates cultural practices as being more preponderant in quilombola self-affirmation in the sertão than racial belonging.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The research described here focused on the belonging and affiliation of a quilombola population to their community. We approached this link considering racial and generational issues, to discover the constitutive elements of the process of racial construction and self-affirmation of children, preadolescents and elderly quilombolas. We believe that the study is important for the community in which it was carried out because it contributes to the construction of the collective identity of the quilombo residents. Concerning the field of childhood, we sought to contribute to the academic debate on racial issues in the context of non-formal educational processes.

We noticed that, when representing their grandparents, the children and preadolescents did not identify them as pretos or negros [both words meaning black]. Although they engaged in the exercise of identifying the Blackness of their elders in their speech, they hesitated to verbalize these terms. We understand the hesitation to be indicative of the difficulty they have to affirm aspects related to the racial identity of older adults. In the WhatsApp exchange — described at the beginning of this paper — the children carried out this same process with themselves, by claiming that they themselves are white.

The data presented in this text indicate that the children resorted to racial whitening in an attempt to distance their people from characteristics that embody their Blackness. Whitening is quite common in power relations in Brazil, and is related to social ascension (Bento, 2014), as it distances Black and brown people from Black phenotypic traits. It is therefore necessary to “[…] understand the whitening of Black people not as manipulation, but as the construction of a white identity that Black people in the process of ascension were coerced to desire” (Bento, 2014, p. 54). Thus, whitening is an effect of the racism present in our society (Lima and Vala, 2004), which imposes colonizing subjectivation processes on Black people, guided by whiteness as the standard of humanity (Schucman, 2010). Whitening, therefore, reverberates differently on the subjectivities of Black (black and brown) and white people in Brazil.

The problematic of whitening complexifies the processes of constructing the racial identity of Black people, while simultaneously giving whites a comfortable condition of subjectivation precisely because they are not racially confronted, but, to the contrary, are seen positively because of their whiteness (Abramowicz and Oliveira, 2012). The privileges granted to whites are broad, from those conditions of subjectivation to the doors that open concretely in their life trajectory because of their color.

Thus, Black children and preadolescents are more vulnerable to having greater difficulties in accepting themselves as Black, which can lead them to resort to efforts at whitening available in society. This is different from what happens with white children, who do not go through this, in addition to the fact that, simultaneously, there is an affirmation of positivities regarding racial self-acceptance. For this reason, it is important to include whites in racial debates (Bento, 2014), given that it is also their responsibility to understand the racial position reserved for whites in the structure of racism.

Considering the reality of quilombos in the sertão region of Alagoas, where there are many Black residents with lighter skin tones, the construction of quilombola racial identities is necessarily related to the culture shared by the community — as the children and preadolescents also indicated. Based on the data presented, the quilombola identity — through its collective character of necessary community militancy and political engagement — is a signifier shared by all, children and elders. In our view, it is essential to invest in actions that significantly contribute to strengthening the quilombola identity, which also engenders the valorization of blackness by different generations.

1Funding: Pro-rectory of Extension of the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL). We would like to express our gratitude to the leaders of the quilombola community Serra das Viúvas, Alagoas; and to the undergraduate student Lisa Victória Lopes Gonzaga de Souza, on behalf of the entire team of the Reading Group in Childhood Studies (GLEI), subgroup of the Center for Studies, Extension and Research in Diversity and Education of the Sertão Alagoano (NUDES), UFAL.

1Project entitled “Reading Group in Childhood Studies (GLEI): the look of children of traditional peoples and communities”, coordinated by the second author and executed within the scope of the Center for Studies and Research on Diversity and Education of the Sertão Alagoano (NUDES), UFAL — Campus do Sertão.

2At the time, we agreed that we would go to their homes to conduct a household survey and use the Free and Informed Consent Terms (FICT), which maintains the identity and personal data of research participants anonynous and protects their image throughout the fieldwork carried out in the community, and in the data later disseminated in papers based on our intervention.

3The researchers responsible for the fieldwork kept the identity of the research participants anonymous, as determined by the consent agreement. Therefore, we here use only initials to identify the children, pre-adolescents, adults and elderly of the community and their respective comments.

Funding: The study received funding from the extension department of the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL).

REFERENCES

ABRAMOWICZ, A. OLIVEIRA, F. As relações étnico-raciais e a sociologia da infância no Brasil: alguns aportes. In: BENTO, M. A. S. (org.). Educação infantil, igualdade racial e diversidade: aspectos jurídicos, políticos e conceituais. São Paulo: Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades, 2012. p. 47-64. [ Links ]

ALAGOAS. Secretaria de Estado do Planejamento, Gestão e Patrimônio. Secretaria Executiva de Planejamento e Gestão. Núcleo de Estudos e Projetos. Estudos sobre as comunidades Quilombolas de Alagoas. Maceió: SEPLAG, 2015. [ Links ]

BENTO, M. A. S. Branqueamento e branquitude no Brasil. In: CARONE, I.; BENTO, M. A. S. (org.). Psicologia social do racismo: estudos sobre branquitude e branqueamento no Brasil. 6. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 2014. p. 25-57. [ Links ]

CAVALLEIRO, E. Educação anti-racista: compromisso indispensável para um mundo melhor. In: CAVALLEIRO, E. (org.). Racismo e anti-racismo na educação: repensando nossa escola. São Paulo: Selo Negro, 2001. p. 141-160. [ Links ]

CAVALLEIRO, E. Do silêncio do lar ao silêncio escolar: racismo, preconceito e discriminação na educação infantil. 6. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2020. [ Links ]

FARIAS, A. M. F.; NASCIMENTO, E. L. G.; BOTELHO, M. S. Q. Quilombos alagoanos contemporâneos: uma releitura da história. Recife: Editora Bagaço, 2007. [ Links ]

FAZZI, R. C. O drama racial de crianças brasileiras: socialização entre pares e preconceito. 2. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2012. [ Links ]

FREITAS, G. C. S. Cabelo crespo e mulher negra: a relação entre cabelo e a construção da identidade negra. Idealogando, v. 2, p. 65-87, 2019. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/idealogando/article/view/238062/Freitas. Acesso em: 5 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. L. Sem perder a raiz: corpo e cabelo como símbolos da identidade negra. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2020. [ Links ]

LIMA, M. E. O. VALA J. As novas formas de expressão do preconceito e do racismo. Estudos de Psicologia, Natal, v. 9, n. 3, p. 401-411, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2004000300002 [ Links ]

MÁXIMO, T. A. C. O.; LARRAIN, L. F. C. R.; NUNES, A. V. L.; LINS, S. L. B. Processos de identidade social e exclusão racial na infância. Psicologia em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 18, n. 3, p. 507-526, dez. 2012. Disponível em: http://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/psicologiaemrevista/article/view/P.1678-9563.2012v18n3p507/5272. Acesso em: 11 out. 2021. [ Links ]

MUNANGA, K. Uma abordagem conceitual das noções de raça, racismo, identidade e etnia. Seminário Nacional: relações raciais e educação. PENESB. Rio de Janeiro. 2003. Disponível em: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4275201/mod_resource/content/1/Uma-abordagem-conceitual-das-nocoes-de-raca-racismo-dentidade-e-etnia.pdf. Acesso em: 13 mai. 2021. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, A. P. O. Que experiências seu cabelo te traz? 2017. 45 f. Trabalho de conclusão de curso (Bacharelado em Psicologia) — Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2017. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, A. P. O.; MATTOS, A. R. Identidades em transição: narrativas de mulheres negras sobre cabelos, técnicas de embranquecimento e racismo. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, v. 19, n. 2, p. 445-463, mai.-ago. 2019. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1808-42812019000200007. Acesso em: 29 set. 2021. [ Links ]

PAULINO, B. S.; MATTOS, A. R. Processos de subjetivação e racialização: reflexões acerca do cotidiano escolar. REBEH: Revista Brasileira de Estudos da Homocultura, Cuiabá, v. 4, n. 13, p. 178-200, 2021. https://doi.org/10.31560/2595-3206.2021.13.11427 [ Links ]

PEREIRA, B. E.; NASCIMENTO, M. L. B. P. De objetos a sujeitos de pesquisa: contribuições da sociologia da infância no desenvolvimento de uma etnografia da Educação de crianças de populações tradicionais. Educação: teoria e prática, v. 21, n. 36, p. 138-156, jan.-jun. 2011. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279478167_De_objetos_a_sujeitos_de_pesquisa_contribuicoes_da_Sociologia_da_Infancia_ao_desenvolvimento_de_uma_etnografia_da_educacao_de_criancas_caicaras. Acesso em: 23 mai. 2021. [ Links ]

PÉREZ, B. C.; SILVA, G. B.; SILVA, L. S. P.; FERNANDES, S. L.; LIBARDI, S. S. Jovens mulheres e expressões da identidade política quilombola em três comunidades diferentes. In: FALEIRO, W. ALVES, M. Z. VIEIRA, L. F. (org.). Vozes e viesses de jovens estudantes. Goiânia: Kelps, 2020. p. 99-126. [ Links ]

PIZA, E.; ROSEMBERG, F. Cor nos censos brasileiros. In: CARONE, I.; BENTO, M. A. S. (org.) Psicologia social do racismo: estudos sobre branquitude e branqueamento no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 2014. p. 91-120. [ Links ]

PRADO, R. L. C.; FREITAS, M. C. Normas éticas traduzem-se em ética na pesquisa? Pesquisas com crianças em instituições e nas cidades. Práxis Educacional, Vitória da Conquista, v. 16, n. 40, p. 25-46, 2020. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v16i40.6879 [ Links ]

RAMPAZO, A. A cor de Coraline. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Lendo e Aprendendo, 2018. [ Links ]

ROMÃO, J. O educador, a educação e a construção de uma auto-estima positiva no educando negro. In: CAVALLEIRO, E. (org.). Racismo e anti-racismo na educação: repensando nossa escola. São Paulo: Selo Negro, 2001. p. 161-178. [ Links ]

SANTOS, I. A. A responsabilidade da escola na eliminação do preconceito racial: alguns caminhos. In: CAVALLEIRO, E. (org.). Racismo e anti-racismo na educação: repensando nossa escola. São Paulo: Selo Negro, 2001. p. 97-113. [ Links ]

SCHUCMAN, L. V. Racismo e Antirracismo: a categoria raça em questão. Revista Psicologia Política, São Paulo, v. 10, n. 19, p. 41-55, jan. 2010. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1519-549X2010000100005. Acesso em: 20 set. 2021. [ Links ]

SILVA, S. S.; FEIJO, L. P.; FARIAS, T. M.; POLETTO, M. Parecer branco para não ser discriminado? Revisão sistemática sobre estratégias de embranquecimento. PSI UNISC, v. 4, n. 2, p. 114-130, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17058/psiunisc.v4i2.14829 [ Links ]

SILVA, N. B.; VIEIRA, R. F. Além da cor da pele: uma análise psicossocial acerca da formação da identidade negra no Brasil. Pretextos: Revista da Graduação em Psicologia da PUC Minas, v. 3, n. 6, p. 259-278, 2018. Disponível em: http://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/pretextos/article/view/15999. Acesso em: 27 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

SOUSA, A. L. Personagens negros na literatura infanto-juvenil: rompendo estereótipos. In: CAVALLEIRO, E. (org.). Racismo e anti-racismo na educação: repensando nossa escola. São Paulo: Selo Negro, 2001. p. 195-213. [ Links ]

SOUZA, M. L. A. “Ser quilombola”: identidade, território e educação na cultura infantil. 2015. [s.n.]. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) — Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2015. [ Links ]

SOUZA, M. H. M. A variação nós e a gente na posição de sujeito da comunidade quilombola Serra das Viúvas/Água Branca-AL. 2020. 91 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística e Literatura) — Universidade Federal de Alagoas, Maceió, 2020. [ Links ]

VALENTIM, R. P. F.; TRINDADE, Z. A. Modernidade e Comunidades Tradicionais: memória, identidade e transmissão em território quilombola. Psicologia Política, v. 11, n. 22, p. 295-308, dez. 2011. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1519-549X2011000200008. Acesso em: 21 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, M. C.; TOMÁS, P. V.; ACCIOLY, A. C.; SOUZA, A. L. O. P. Projeto Renascendo: nascentes vivas no sertão. Aracaju: J. Andrade Editora, 2019. [ Links ]

Received: December 27, 2021; Accepted: November 04, 2022

text in

text in