Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

Print version ISSN 1413-6538On-line version ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.24 no.3 Marília July/Sept 2018 Epub July 01, 2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382418000300004

Research Report

Social Representations and Special Education Teacher’s Epistemological Conceptions of Learning2

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the teacher’s epistemological conceptions of learning (n = 12) during the continuing teacher education program of a Basic Education School, Special modality, from Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. The qualitative research was developed from the hermeneutic phenomenological perspective, drawing from the Theory of Social Representations as a theoretical and methodological resource for data analysis. The IRAMUTEQ software was used for statistical analysis data obtained through the protocol of the observation of the meetings. The continuing teacher education program took place over eight meetings lasting two hours each. For each meeting, one researcher registered the speeches of the participants (theme registration) and another one registered the movements of the group (dynamics registration). The register of the teachers’ statements during the meetings formed a textual body which was submitted to similarity analysis and the graphic representation of word clouds by IRAMUTEQ software, giving rise to the categories of analysis. The innate and empirical epistemological conceptions of learning coexisted in the teachers’ social representations. The conceptions were anchored in the organicist view of disability and ideas that reinforce the handicaps of children with disabilities and not their potentialities. As a consequence, teachers work on the preparation of children with disabilities for their integration into society, and not on educational actions aimed at their effective inclusion in society. The results refer to the teacher’s continuing education, the promotion of reflective discussions with the pedagogical team about the role of the special school and the encouragement of interdisciplinary work in the institution.

KEYWORDS: Epistemology of learning; Special Education; Continuing Education

O propósito deste artigo foi investigar as concepções epistemológicas de aprendizagem de professores (n = 12) no decorrer do programa de formação continuada de uma Escola de Educação Básica Modalidade Especial de Curitiba/PR. A pesquisa qualitativa desenvolveu-se a partir da perspectiva fenomenológica hermenêutica, apoiando-se na Teoria das Representações Sociais como um recurso teórico e metodológico para a análise dos dados. Foi utilizado o software IRAMUTEQ para análise estatística dos dados obtidos por meio do protocolo de observação dos encontros. O programa de formação continuada aconteceu em oito encontros com duração de duas horas cada. A cada encontro, um pesquisador registrava as falas dos participantes (registro da temática), e outro, os movimentos do grupo (registro da dinâmica). Os registros das falas dos professores no decorrer dos encontros formaram um corpo textual que foi submetido à análise de similitude e a representação gráfica nuvem de palavras pelo software IRAMUTEQ, dando origem às categorias de análise. As concepções epistemológicas de aprendizagem inatista e empirista coexistiram nas representações sociais dos professores. As concepções estavam ancoradas na visão organicista da deficiência e em ideias que reforçam a falta e não as potencialidades das crianças com deficiência. Em consequência, os professores atuam no preparo da criança com deficiência para sua integração na sociedade, e não em ações educativas voltadas a sua inclusão efetiva na sociedade. Os resultados remetem à formação continuada do professor, ao fomento de discussões reflexivas junto à equipe pedagógica sobre o papel da escola especial e ao incentivo do trabalho interdisciplinar na instituição.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Epistemologia da Aprendizagem; Educação Especial; Formação Continuada

1 INTRODUCTION

There was a time when the special school was understood to be a substitute to the regular school for the assistance of students with disabilities. With school inclusion, Special Education begins to act in an articulated way with the integrated pedagogical proposal of the regular school (Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva, 2008). One of the objectives of specialized educational services is to promote actions that better meet the specific needs of students with disabilities, complementing school education and supporting student development (Batista, 2006). This is also one of the objectives of the school where this research took place. This study originated from a continuing education program for teachers of a school of Basic Education - Early Childhood Education/Special Modality in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, which was developed by the research group Aprendizagem e Conhecimento na Formação Continuada (Learning and Knowledge in Continuing Education) at the Stricto Sensu Program in Education at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR). This school is linked to the State Secretariat of Education (SEED) for the provision of Basic Education in the Special Education modality for students with disabilities and global developmental disorders.

From the meetings with the students, the following question arose: What are the epistemological conceptions about learning that permeate the speeches of the teachers from the school of Special Education? The definition for epistemological conceptions is close in the sense proposed by Tardif (2013), in which they express models of educational thinking about the understanding of learning, which, in turn, effectively underpin teachers’ practice. This concept has an epistemological status for the representations that teachers have about learning. These representations act as prior knowledge that regulates actions and results in the daily work space. In this sense, the Theory of Social Representations, as proposed by Moscovici (1978), acts as a theoretical and methodological resource that assists the analysis of this work.

According to the French social psychologist Moscovici (1978, p. 26), ‘[...] social representation is a particular form of knowledge whose job is the elaboration of behavior and communication between individuals’. To him, social representations are elaborated from two processes, objectification and anchoring; two fundamental concepts for the understanding of his theory. The process of objectification, according to the author, unites what is not familiar to the reality of the person. To do so, one goes on to discover the iconic quality of an idea or to reproduce a concept in an image. Objectivation is a representative activity that builds the form of a knowledge (Alves-Mazzotti, 2008). Anchoring is the process by which the subject classifies and names something; thus, he/she chooses one of the paradigms stored in his/her memory and establishes a positive or negative relation with it (Moscovici, 2003).

Jodelet (2001) explains that social representations form a system, with versions of reality incarnated by images or condensed by words, which are full of meanings. Their job is to interpret aspects of daily reality, allowing the subject to make decisions, to take action and eventually to position him/herself in relation to a situation in a defensive way. Social representations surpass the scope of the individual, and at the same time is a representation of someone and something. It is always a relation between the subject and the object (S↔O) (Moscovici, 1978). Thus, according to the theory of social representations, the system of interpretation of reality by teachers will determine their behaviors and practices in school. And it is through the processes of objectification and anchoring that one intends to have access to this system of pre-coding of reality (Abric, 2000), composed of anticipations and expectations of actions by teachers.

In relation to the construction of theories about human knowledge, it is possible to distinguish between three epistemological conceptions involved in the understanding of the learning process: innatism, empiricism and interactionism. Each one is influenced by a philosophical thought originating from theories about learning. However, in order to elucidate the meanings of the words ‘knowledge’ and ‘learning’ in this text, knowledge is understood as the act or effect of knowing, from the Latin cognoscere. Knowledge is the result of learning, it is what one learns. According to Pozo (2002), it is what changes as a consequence of learning from the previous characteristics of the subject - for instance, knowledge about the three physical states of water in nature or the knowledge that comes from perceptual experiences, such as emotions associated with listening to a song. Learning, according to Pozo (2002), is understood to be how changes occur from the previous characteristics of the subject, through cognitive mechanisms - learning is the mental activity of the person while in action, such as attention, reasoning or perception.

Knowledge was initially discussed by philosophers in the search for true explanations of things, and these philosophical theories had repercussions on the evolution of theories about learning, resulting in three epistemological conceptions of learning that permeate teachers’ discourses. The first conception, innatist, according to Porto (2006), originates in philosophical idealism, founded by Plato5 and later influencing Saint Augustine (1996) 6, a medieval philosopher and theologian. Idealism argues that knowledge is not based on sensitive experiences, which are transient and, therefore, do not offer certainty about knowledge. To Plato (1997), access to reality occurs by ideas and not by the sensible character of things. These explanations underlie the innatist conception of learning, which asserts that individuals naturally carry skills, abilities, knowledge, and qualities in their biological and hereditary constitution. As an example of this conception, the discourse of a teacher who participated in the research, is when he says that he learned the knowledge for his work by himself, or that he was born a teacher, is based on an innatist conception to justify his practice or career choice.

Becker (1993) points out that the epistemological foundation in support of this conception is the idea of apriorism - that the individual brings with him/her the conditions of learning and knowledge, independent of his/her experience. This epistemological relation can be represented by S ? O, where ‘S’ is the subject and ‘O’ is the object of knowledge. The arrow starting from the subject towards the object represents the action to reach knowledge, which is exclusive of the subject, therefore the environment does not participate. As a consequence of the innatist conception, a teacher can attribute school success or failure to the biological or hereditary condition of a student, and may argue that he/she does not learn because of his/her medical report, because he/she was born with a disability or disorder. Arguments of this type make it impossible for the student to develop due to the passive attitude of the teacher who sees him/herself with his/her hands tied to the previous condition for the child’s learning.

The conception contrary to innatism is empiricism. According to Porto (2006), empiricism proposes a rule to differentiate the imaginary conception to that of the real world, hence, the test of the sensitive experience. To the empiricists, all knowledge comes from experience, through information captured by the senses in the outer environment. Among modern philosophers, Locke (1999) states that there are no innate ideas, since there is no universal consensus on them, nor are they present in children. By the empiricist conception, the mind is defined as a blank slate, an empty space to be filled, which, according to Becker (1993), nullifies the creative ability of individuals who are understood as mere recipients of knowledge. As an example of this conception: the statements from the research participants (teachers) when they claimed that what they know was learned from life, or learned because they had a teacher who explained the concepts well to the classroom, or even learned by observing. These statements translate the empiricist conception to reach knowledge, applied to the way of understanding their own learning. We can represent this relation by: S ? O, in which the arrow changes direction, goes from the object to the subject. Knowledge would come from the world of the object (material or social) determining the subject. This conception, applied to the teacher’s practice, considers the student a passive subject in the pedagogical relation, receiver of the contents transmitted by the teacher or by the environment. The teacher does not consider the action of the subject as the generator of changes in the environment or able to change it for learning, the teacher nullifies the child in this pedagogical relation.

According to Porto (2006), the attempt to overcome the dichotomy of innatism/empiricism appears in Kantian philosophy and in St. Thomas Aquinas, influenced by Aristotle’s thinking. The author adopts the transcendental term to designate philosophical ideas that offer an alternative to Platonic idealism and to empiricism, the transcendental conception understands that the foundation for the knowledge is in principles that coordinate the acquisition of knowledge, accepting the evidence of the senses and, at the same time, establishing the conditions required by experience. In the 20th century, Piaget (1987) developed genetic epistemology, a theory of knowledge based on the study of the psychological genesis of human thought, overcoming earlier conceptions of the origin of knowledge (innatist and empiricist). In his studies, Piaget (1987, p. 389) concludes that:

[...] assimilation and accommodation, at first antagonistic to the extent that the first remains egocentric and the second is simply imposed by the external environment, complete each other to the extent they are differentiated, the coordination of the schemata of assimilation favoring the progress of accomodation and vice versa. So it is that, from the sensorimotor plane on intelligence presupposes an increasingly close union of which the exactitude and the fecundity of reason will one day be the dual product.

Thus the author explains the origin of knowledge in a double sense: the world of the object provides content (assimilation), and the subject creates new forms of organization (accommodation) of that content. The structures of knowledge are the result of a process of interaction between the world of the subject and the world of the object. Becker (1993) represents this epistemological model by S ? O, in which the arrow represents a dual meaning in the relation between subject/object. This relation is intended as an interaction between the subject, who in his/her action to know ends up altering the environment, and between the object of knowledge, which, when apprehended by the subject, causes changes and also changes the way the subject understands the world. This dialectic relation between subject and object of knowledge provides the interactionist conception of learning, which when applied to the teacher’s performance leads to understanding the student as an active subject, acting in his/her knowledge process, and the teacher as the mediator of this process, who intervenes at opportune moments to stimulate the learning potential of his/her students.

The three conceptions of learning, namely: innatism, empiricism and interactionism, coexist in contemporary society, especially at school, in the way knowledge is presented, in the methodology adopted in the classroom and in the learning assessment. These three conceptions can be organized in different ways of social representations and effectively support the teacher’s practice.

When reviewing the literature on the social representations of teachers about the learning of students with disabilities, few studies were found. The criteria adopted in the review were the terms: social representations, teachers, learning and disability. The researches, theses and dissertations published over the last ten years in the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) and in the Portal of Journals of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) - Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - were taken into account. Only research conducted in the Portuguese language were included, since it is a symbolic system, the language can be a differentiator of the social representations of the participants.

Barbosa’s study (2014) relates to the objectives of this research, as it analyzed the social representations of teachers on the learning of students with disabilities in the final years of inclusive Elementary School. The author concluded that the social representations of teachers were anchored in conceptions about the disability, understood as something limiting, associated with the idea of ‘lack’ and ‘absence’ of something/capacity. However, teachers also addressed learning as a process, highlighting the potential of the student with disability.

This coexistence and alternation of conceptions about learning can also be verified in a study by Fragoso and Casal (2012). In Portugal, the authors investigated the social representations of childhood educators regarding the inclusion of children with disabilities in regular schools and concluded that, in general, teachers are in favor of the inclusion process, with ideals of promoting equal opportunities and mutual help. However, they also observed discrimination of children with disabilities due to a lack of information, education, social class and economic level, hygiene issues, difficulties in accepting the difference and the physical limitations of schools.

Finally, Musis and Carvalho’s study (2010), as well as Fragoso and Casal’s (2012), aimed to investigate the social representations of teachers regarding the inclusion of students with disabilities in regular education, and found that the perception of the teacher regarding a student with a disability is anchored in a hegemonic representation of normality. Thus, the teacher’s practice is influenced by the desire that the students correspond to a physical configuration and to an intellectual behavior pre-established by society as average standard.

Barbosa (2014), Fragoso and Casal (2012) and Musis and Carvalho’s (2010) researches present ideas or thoughts about the disability that refer to the conceptions of learning by the teachers. Through the speeches of the teachers from the School of Special Education, this paper sought a deeper analysis and aimed to highlight the social representations on learning and to identify the epistemological conceptions in which they are anchored.

2 METHOD

2.1 PARTICIPANTS

A non-probabilistic sample of 12 teachers of a continuing education program from a Basic Education School in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, took part in the research. All participants were women, with a mean age of 44 years, ranging from 23 to 58 years old. The average length of time in the profession (taking into account the pre-work period at the school where the research was carried out) was 16 years, but the total service of these teachers just at the school where the research was developed ranged from 10 months to 16 years.

As for their education, the majority were graduated in Pedagogy, with the exception of three teachers, T2, T3 and T7, who graduated in History, Physical Education and Literature, respectively. Almost all the teachers reported having a course or being enrolled in a Post-Graduate Special Education course, only two of them did not specialize in this area: T6 and T12.

2.2 MATERIAL

At each meeting of the continuing education program, two observers/researchers carried out the registration of the theme and the dynamics of the group during the proposed tasks. In order to do so, they used the Observation Protocol of the meetings, where they registered the theme (what was said in the group) and the dynamics (the movement of the group). The records were a production of texts from the statements of the teachers during the course of continuing education.

For the analysis of the texts produced from the records of the meetings, the software IRAMUTEQ (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) was used, a free software that is supported in software R and allows different forms of statistical analyzes on textual corpus.

2.3 PROCEDURES

The epistemological conceptions of the teachers’ learning were apprehended through their narratives in the eight reflective meetings of the continuing education program developed in the school of Basic Education, Special modality. It was based on ethical considerations guaranteed by the approval of the Committee of Ethics in Research with Human Beings under number 205.177, report date February 20, 2013. The information collected at the meetings had the consent of all participants and all data that allowed the identification of the participants were changed.

The continuing education program for the school of Basic Education, Special modality, was developed over eight meetings lasting two hours each. These meetings took place on Saturday mornings in the school library. The structure and organization of the meetings were based on the theory of Operative Groups proposed by Pichon-Rivière (2009), whose objective was to mobilize groups of teachers to solve tasks. The themes of the meetings were: 1) presentation of the proposal of the continuing education program to the group; 2) teacher professionalization and continuing teacher education; 3) intervene and interfere; 4) to learn and teach in a special way; 5) learning styles and strategies; 6) teaching styles; 7) educational environment; 8) assessment and registration of the teacher’s performance. All the meetings were registered by two observers/researchers (thematic and dynamic) during the tasks and the conversation circle.

The qualitative method adopted, phenomenological hermeneutic, had five stages: 1) collection of verbal and non-verbal data; 2) data reading; 3) division of data into categories - for that, we counted on the aid of the IRAMUTEQ software. The data analyzed by the software were the records of the transcriptions of the teachers’ statements during the program; 4) organization of raw data in the language of the research, that is to say, from the vocabulary of the learning theories that base the research; and 5) synthesis of results for communication to the scientific community (Giorgi, 2008).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

From the records of the theme held in the eight meetings of the continuing education program, a textual body was constructed, composed of all the records of the teachers’ statements during the meetings. After organizing all the records of the eight meetings, each teacher’s statement was identified with a command line so that the IRAMUTEQ software could identify its issuer. The statements of the coordinator of the group were withdrawn in order to include only the data referring to the subjects of the research.

Firstly, this textual body was submitted to the analysis of similarity, based on the graph theory. This analysis identifies the vectorized parts of discourses that share the same vocabulary and interprets them semantically close to each other (Chartier & Meunier, 2011). The similarity analysis of the eight encounters identified the word ‘GENTE’7 as having the greatest relevance in the textual body, showing up in 168 segments of the text. Turning to the original records of the meetings, it was found that in the segments where the word ‘GENTE’ (we) was used, the teachers were referring to themselves, like in the translated excerpts: ‘We do not skip any stages. We look for other alternatives. We learn much more’ (T7). ‘We are learning. We do what we can’ (T3). Thus, all the words ‘GENTE’ (we) have been replaced by the word ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher), giving rise to a new textual body. The substitution of the words was used as a strategy to identify the statements in which the teachers referred to themselves.

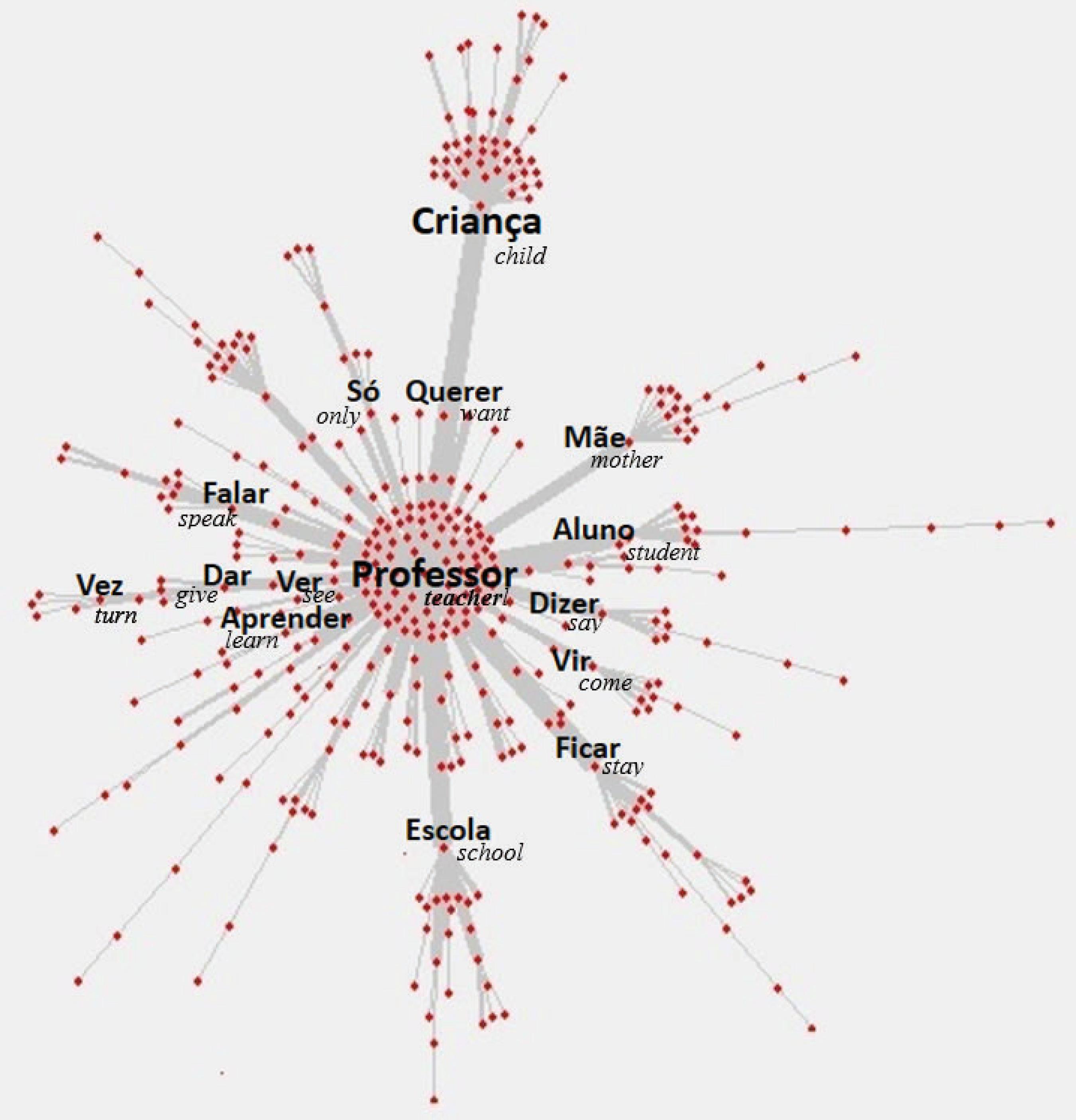

After replacing the word ‘GENTE’ (we) for the word ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher), there was an increase of 74 segments, making a total of 242 segments of the text in which the teachers referred to themselves in their narratives. The tree of similarity analysis (Figure 1) shows the word ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) as the nucleus of the discussions that occurred at the meetings. Around this nucleus, there are significant relations between the words8: ‘QUERER’ (want) (85 segments), ‘DAR’ (give) (76 segments), ‘FALAR’ (speak) (76 segments), ‘DIZER’ (say) (75 segments), ‘ALUNO’ (student) (73 segments), ‘VER’ (see) (67 segments), ‘ESCOLA’ (school) (58 segments), ‘FICAR’ (stay) (54 segments), ‘VEZ’ (turn) (49 segments), ‘APRENDER’ (learn) (47 segments), ‘VIR’ (come) (46 segments), ‘SÓ’ (only) (46 segments) and ‘MÃE’ (mother) (45 segments). There is, in particular, a strong relation with the word ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) (122 segments), belonging to a field farther from the ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) nucleus.

In agreement with the objective of this work, we chose to describe the words that presented total frequency (eff. total) equal or superior to 45 occurrences in the text and, from their meanings in the textual fields, those that had greater relevance for the social representations on learning, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Total frequency (total eff.) of each word

| Words | |

|---|---|

| Professor (teacher) | 242 |

| Criança (child) | 122 |

| Querer (want) | 85 |

| Dar (give) | 76 |

| Aluno (student) | 73 |

| Aprender (learn) | 47 |

| Mãe (mother) | 45 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The words in Table 1 generated categories of analysis, which assumed titles as the same words identified by the system.

Another way to analyze the textual body by IRAMUTEQ software is through the word cloud (Figure 2), an analysis that groups and organizes keywords according to their frequency.

Looking at Figure 2, it is possible to observe that the ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) category was at the center of the group’s discussions during the eight meetings of the education program. The other categories, which derive from the ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) category, refer to the subject teacher and his/her frame of reference. When teachers discussed the child, the student, the mother and learning, they spoke from their own perspective, showing little reciprocity (Claxton, 2005), and not making the move to put themselves in the shoes of the other to relativize their knowledge. In the teaching-learning relation, little reciprocity can also influence teacher-centered decisions.

The next category, ‘CRIANÇA’ (child), refers to the child with a disability. The teachers refer to the children as being different from other schools, they talk about cleaning, clothing and feeding of children. As in the statements: ‘The child comes dirty, what a pity, or comes crying a lot’ (T3); ‘This week there was a child who screamed, beat himself, cried, and in the end he was hungry, but he could not speak’ (T7); ‘Schools do not accept our children’ (T3); ‘Naturalistic schools bring together one-year-olds, three-year-olds, six-year-olds, but they are normal children, and they deal with things themselves, our school is different, there is one who beats their head and one who bites’ (T7); ‘The special child is not ready, but he/she is happy and sometimes brings the answer that you needed in your class’ (T3); ‘To try to reach our children who are special’ - teacher (T3) when talking about teaching styles.

The ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) category in the tree of similitude (Figure 1) is located in an arrangement other than the one of the ‘ALUNO’ (student) category, and does not share the same meaning, as will be seen below. The ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) category has the meaning of a child with a disability. Teachers refer to the child as a failure, because they need special attention, have poor speech or do not even talk, need clean clothes and a wash, their learning capacity is deficient. To the teachers, the children of the school of Basic Education, Special modality, are different from the others, corresponding to the segregation process of the child with a disability.

The meanings attributed to the ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) category are linked to the idea of the subject as a blank slate to be filled by experience (empiric conception of learning), as in this teacher’s statement: ‘The special child is not ready, but is happy’ (T3), resulting in the process of educating the child with a disability. As Pozo (2002) states, all teaching is based on a conception of learning, most of the time implicitly. The empiricist conception of learning can trigger actions of integration and not of effective inclusion of children with disabilities in society (Aranha, 2003).

The category ‘QUERER’ (want) assumes more than one meaning in the teachers’ statements. When referring to the student’s family, ‘wanting’ appears as a desire to change the physical or special condition of the children, as the following excerpts show: ‘The mother wanted a diagnosis’ (T4); ‘Parents want a word of optimism’ (T3); ‘In fact she wanted them to say that he was not autistic’ (T12). These statements translate a request for help from parents to teachers in relation to the special condition of their children. However, this request was not understood by the teachers, who took the parents’ words as a complaint regarding the family. When teachers refer to the student or the child, the category ‘QUERER’ (want) is related to actions or physiological needs such as eating, biting, leaving, hugging. Teachers refer to the child with a disability as an organism with physiological needs, as in the excerpts: ‘You arrive in the classroom, prepare an activity and she (the child) comes crying, she does not want to know about activity, she wants to eat’ (T3); ‘There is a student who wants to bite, I call his attention’ (T5); ‘A., for example, is a CP [child with cerebral palsy], she wants to eat by herself, she gets very dirty, she takes long’ (T10); ‘He [the student] is very aggressive, he wants to hug, but he hurts the children’ (T3); ‘I don’t know what to do with this student, I have another twenty [students], and, when he arrives, students are afraid of him, his mother puts on a lot of activities, and when he arrives at four o’clock, he is unbearable, he wants to bite’ (T3). The organic, biological or medical view of children with disabilities present in the teachers’ statements seem to reinforce the empiricist conception of learning, causing the child to be annulled in the teacher/student pedagogical relationship.

The ‘DAR’ (give) category is related to the teacher’s performance in the classroom, as in the expression ‘dar aula’ (give class) in the sense of performing an action, or fulfilling/accomplishing the action of teaching. This can be seen in the excerpts that follow: ‘The teacher says: won’t you give activities?’ (T5); ‘It is not simply giving the content’ (T2); ‘There were teachers who gave classes out of interest, but there were also teachers who adapted their didactics according the students’ style’ (T8). The ‘DAR’ (give) category also appears in contexts about teachers’ complaints in relation to a lack of time, inability to complete or achieve goals and teacher’s emotional state regarding these situations. As in these excerpts: ‘(the child) has already taken the pen, has already bitten the other, there is no time’ (T3); ‘Because the teacher has to deal with the content, and the school management demands an explanation, because the student did not learn’ (T3); ‘At the end of the school year we have an assessment to deal with, everyone does, it is (our) role’ - teacher T3 when talking about the mandatory assessment that he/she applies to the students; ‘Sometimes the smell in the classroom is strong, I can hardly stand it, but let’s move forward anyway, I could not work in regular education, only with special children’ (T5); ‘He gives me a hard time in the playground’ - teacher when talking about the student when he goes to play. The teachers’ statements brought a lot of complaints about the work, but with few moments of group reflection or self-reflection that would make it possible to reduce the anguish experienced by the impossibilities of children and work, which refers to the teacher’s own difficulties.

In the ‘DAR’ (give) category, there were four references to student autonomy, in the excerpts: ‘We cannot be the only agents of knowledge, [we have to] see what the child is doing in order to give him/her autonomy’ (T8); ‘We should give the child an opportunity to show his/her potential’ (T2); ‘She [the teacher] is always giving the student a chance, she positions him on the chair or with a box so he feels comfortable’ (T2); ‘The teacher has to give him [student] the opportunity to show what he knows’ (T7). When they were instigated to reflect on the autonomy of the student, the teachers used the expression ‘dar oportunidade’ (give opportunity), keeping the teacher/student relationship centered on the teacher, because it is by the teacher’s deliberation that the child can act with a certain autonomy. The ‘DAR’ (give) category was strongly related to the ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) category in the sense of its practical action. The expressions of the ‘DAR’ (give) category have taken the conception of learning from the direction of the teacher towards the student, by transferring something in the educational action, based on the empiricist conception of learning.

The ‘ALUNO’ (student) category refers to the child who is in school or in the classroom. ‘ALUNO’ (student) is a recurring word that appears associated with the possessive pronouns, ‘my’, ‘your’, ‘our’, giving sense of belonging to a school, a class or a teacher. As in these excerpts: ‘You will assess your students all together, and they are not even yours’ - teacher T5 when referring to the difficulty in evaluating students; ‘From the moment you come to school you are not a student of the teacher, but of the institution’ (T12); ‘In spite of not being my student, but the student of another, perhaps what I teach will reflect in the other professional’s classroom’ (T2). The student is the one who receives instruction or education from the educational institution or from someone, it is different from the ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) category, since it does not show the characteristic of disability. The ‘ALUNO’ (student) category is less recurrent than the ‘CRIANÇA’ (child) category, resulting in fewer references to the formal teaching relation between teachers.

The ‘APRENDER’ (learning) category, when referring to the child or student, does not translate the idea of process, but the polarization into yes or no, learn or not learn, want or does not want to learn, and the need or importance of learning. As the excerpts from the following statements reveal: ‘You mediate the child and he/she learns or does not learn’ (T7); ‘It is necessary to divide the class, to separate the ones who want to learn from those who do not want, and who do not have any mental problems’ (T7); ‘It is different to a child who has potential, but does not want to learn’ (T7). The teachers’ statements reflect the innatist conception of learning that, according to Becker (1993), points out that the individual already brings with him/her the conditions of learning and knowledge, regardless of their experience, justifying school success or failure to the biological or hereditary condition of a student.

The ‘MÃE’ (mother) category translates to the mother/teacher relationship. As in these excerpts: ‘How will the teacher question the mother in relation to the child coming clean and having a welcoming environment?’ (T3); ‘The mother says that the teacher is crazy, how will you contradict this mother?’ (T3); ‘The mother says that the teacher is wrong’ (T3); ‘The mother asks the trainees: Do they treat the students well here?’ (T4); ‘The mother complained about the clothes being dirty with chocolate [...], but they want to dress well to show that children are well treated’ T3). The mother comes across as the one who distrusts, who does not understand the work of the teacher, who complains, does not have a partnership with the teacher to continue giving support outside of school, and does not take care of the hygiene of the child. The strong connection in the tree of similitude (Figure 1) between the categories ‘PROFESSOR’ (teacher) and ‘MÃE’ (mother) can be interpreted as a conflictual relation and, therefore, it is recurring in the group speeches. At times, parents seem to be deprived of their job, and are expected to be co-teachers of children or caregivers in the sense of assisting with hygiene, food and basic care. Parents would have to establish a positive and healthy bond with their children, loving them and accepting them for their differences (Schmidt, 2003). This category highlights the need for spaces for teachers’ reflection and preparation of the team to meet the subjective demands that the family presents.

In short, the social representations of the teachers of the school of Basic Education, Special modality, are firmly held in the innatist and empiricist conceptions of learning, which are conducted in the practical experiences of the teachers, causing the student to be annulled or held responsible for his/her success or failure in the process of learning.

4 CONCLUSION

The social representations and conceptions of learning by the teachers of the school of Basic Education, the Special modality researched, oppose the institution’s objective, which is to promote independence, socialization and social and educational inclusion of children. As in the studies of Barbosa (2014), Fragoso and Casal (2012) and Musis and Carvalho (2010), the social representations of the teachers investigated are full of meanings about the disability, conceived as limiting, negative, determinant; about absence, about the different (compared to a normal pattern), the one that nullifies the other and is conducted by medical explanations.

In conclusion, the conceptions of innatist and environmentalist learning coexist in the statements of the researched teachers and reinforce the actions of integration of the child with a disability in society, that is, the one that invests in the promotion of changes in the child, in the direction of his/her normalization. However, according to Aranha (2003), the actions of inclusion are those that invest in the process of child development, creating immediate conditions for access and participation in community life, enabling them to manifest themselves in relation to their desires and needs, through physical, psychological, social and instrumental supports.

Work integrated with the school’s therapeutic team seems to be an alternative for the teacher, who could discuss the cases in a group and elaborate a joint project aiming to assist in the educational needs of each child, to share knowledge and uncertainties. In addition, continuing education programs that question the domain of specific knowledge, such as courses and specializations in Special Education, would possibly help the teacher to be able to work adequately with the student with a disability. And also, to include spaces of constant reflection between teachers and pedagogical teams, in these continuing education programs seeking to reduce the anguish experienced in relation to the daily challenges of this work.

5See The republic, by Plato. Available on http://www.idph.net/conteudos/ebooks/republic.pdf

6See Augustine: Confessions. Available on http://www.idph.net/conteudos/ebooks/republic.pdf

8Note of translation: in this paper, we kept the words in Portuguese with its translations in parentheses as the terms generated by IRAMUTEQ software were in Portuguese, as also presented in Figure 1.

9Note of translation: the highlighted words are those previously presented: ‘professor’ (teacher), ‘criança’ (child) ‘querer’ (want), ‘dar’ (give), ‘falar’ (speak), ‘dizer’ (say), ‘aluno’ (student), ‘ver’ (see), ‘escola’ (school), ‘ficar’ (stay), ‘vez’ (turn), ‘aprender’ (learn), ‘vir’ (come), ‘só’ (only), ‘mãe’ (mother), among others.

REFERENCES

Abric, J. (2000). O estudo experimental das representações sociais. In D. Jodelet (Org.), Representações sociais (pp. 155-171). Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ. [ Links ]

Alves-Mazzotti, A. J. (2008). Representações sociais: Aspectos teóricos e aplicações à educação. Revista Multiplas Leituras, São Paulo, 1(1), 18-43. [ Links ]

Aranha, M. S. F. (2003). Inclusão Social da Criança Especial. In A. M. C. de Souza (Org.), A criança especial: Temas médicos, educativos e sociais (pp. 307-322). São Paulo: Roca. [ Links ]

Barbosa, K. A. M. (2014). Representações sociais de professores dos anos finais do ensino fundamental sobre a aprendizagem de estudantes com deficiência em escolas inclusivas (Dissertação de Mestrado). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brasil. [ Links ]

Batista, C. A. M. (2006). Educação inclusiva: Atendimento educacional especializado para a deficiência mental (2a ed.). Brasília, DF: MEC, SEESP. Recuperado em 09 de Novembro de 2016 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/defmental.pdf. [ Links ]

Becker, F. (1993). A epistemologia do professor: O cotidiano da escola. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Chartier, J., & Meunier, J. (2011). Text mining methods for social representation analysis in Large Corpora. Papers on Social Representations, 20(37), 1-47. [ Links ]

Claxton, G. (2005). O desafio de aprender ao longo da vida. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Fragoso, F. M. R. A., & Casal, J. (2012). Representações sociais dos educadores de infância e a inclusão de alunos com necessidades educativas especiais. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, Marília, 18(3), 527-546. [ Links ]

Giorgi, A. (2008). Sobre o método fenomenológico utilizado como modo de pesquisa qualitativa nas ciências humanas: Teoria, prática e avaliação. In J. Paupart, J. P. Deslauriers, L. H. Groulx, A. Laperrière, R. Mayer, & A. P. Pires (Orgs.), A pesquisa qualitativa: Enfoques epistemológicos e metodológicos (pp. 386-409). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (2001). As representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ . [ Links ]

Locke, J. (1999). Ensaio acerca do entendimento humano. São Paulo: Nova Cultural. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1978). A representação social da psicanálise. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2003). Representações sociais: Investigações em psicologia social. Petrópolis: Vozes . [ Links ]

Musis, C. R. de, & Carvalho, S. P. de (2010). Representações sociais de professores acerca do aluno com deficiência: A prática educacional e o ideal do ajuste à normalidade. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, 31(110), 201-217. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. (1987). O nascimento da inteligência na criança (4a ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara. [ Links ]

Pichon-Rivière, E. (2009). O processo grupal (8a ed.). São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Platão (1997). A república. São Paulo: Nova Cultural . [ Links ]

Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva (2008). [Documento elaborado pelo Grupo de Trabalho nomeado pela portaria n. 555/2007, prorrogada pela portaria n. 948/2007, entregue ao ministro da Educação em 7 de janeiro de 2008]. Recuperado em 18 de Julho de 2017 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/politicaeducespecial.pdf. [ Links ]

Porto, L. S. (2006). Filosofia da educação. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar. [ Links ]

Pozo, J. I. (2002). Aprendizes e mestres: A nova cultura da aprendizagem. Porto Alegre: Artmed . [ Links ]

Santo Agostinho. (1996). Confissões. São Paulo: Nova Cultural. [ Links ]

Schmidt, A. P. (2003). A Equipe Terapêutica e a Criança Especial. In A. M. C. de Souza (Org.), A criança especial: Temas médicos, educativos e sociais (pp. 35-40). São Paulo: Roca . [ Links ]

Tardif, M. (2013). Saberes Docentes e Formação Profissional (15a ed.). Petrópolis: Vozes . [ Links ]

Received: August 03, 2017; Revised: February 24, 2018; Accepted: March 27, 2018

text in

text in