Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

versão impressa ISSN 1413-6538versão On-line ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.1 Marília jan./mar. 2020 Epub 12-Fev-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382620000100008

Research Report

High Abilities/Giftedness: Social Skills Intervention with Students, Parents/Guardians and Teachers2

3PhD student and Master’s in Developmental Psychology and Learning from the Faculty of Sciences. Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho - UNESP. Bauru/São Paulo/Brazil. Email: ana_paula_apo@hotmail.com.

4Adjunct Professor at the Department of Education, Graduate Program in Developmental Psychology and Learning, and at the Teaching Program for Education. Faculty of Sciences, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho (UNESP). Bauru/São Paulo/Brazil. Email: vera.capellini@unesp.br.

5Adjunct Professor at the Department of Psychology and at the Graduate Program in Developmental Psychology and Learning. Faculty of Sciences. Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho - UNESP. Bauru/São Paulo/Brazil. Email: olgarolim@ fc.unesp.br.

The aim of this study was to describe and compare the social skills, behavioral problems, and academic competence of students with High Abilities/Giftedness (HA/G): 1) according to their own account, before and after a program on social skills; and 2) according to the report of their parents/guardians and teachers, before and after guidance on HA/G and social skills. The participants were nine children from a public school, nine parents/guardians and eight teachers. The participants answered the Social Skills Rating System Questionnaire (SSRS) version for parents, teachers and students. The intervention with the students occurred in eight weekly meetings and the parents/guardians and teachers, in three fortnightly meetings. The results showed that the students’ social repertoire improved from their point of view, and their teachers and parents, probably due to the intervention procedure used, involving more than one segment.

KEYWORDS: Student with High Abilities; Giftedness; Social skills; Special Education

O objetivo deste estudo foi descrever e comparar o repertório de habilidades sociais, problemas de comportamento e competência acadêmica de estudantes com Altas Habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): 1) segundo o relato deles mesmos, antes e depois de um programa sobre habilidades sociais; e 2) segundo o relato de seus pais/responsáveis e professoras, antes e depois de orientações sobre AH/SD e habilidades sociais. Participaram nove estudantes de uma escola pública, nove pais/responsáveis e oito professoras. Os participantes responderam ao questionário Sistema de Avaliação de Habilidades Sociais (SSRS) versão para pais, professores e alunos. A intervenção com os estudantes ocorreu em oito encontros semanais e dos pais/responsáveis e professores, em três encontros quinzenais. Os resultados apontaram que o repertório social dos estudantes melhorou no ponto de vista deles, de suas professoras e de seus pais, provavelmente devido ao procedimento de intervenção utilizado, que envolveu mais de um segmento.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Aluno com Altas Habilidades; Superdotação; Habilidades sociais; Educação Especial

1 Introduction

High Abilities/Giftedness (HA/G) is characterized by the high potential of aptitudes, talents and skills, evidenced in the high performance in the various areas of human activities including academic, demonstrated since childhood. Such areas include the intellectual, academic, leadership, psychomotor and arts fields, among others (National Policy for Special Education from the Perspective of Inclusive Education [PNEEPEI], 2008; Law no. 12,796, April 4, 2013).

The identification of children with HA/G has been based on the theoretical perspective of the Three Ring Model (Renzulli, 1998, 2011). In this conception, HA/G is due to the confluence of three factors: above average intellectual ability, task involvement and creativity. The current definition of HA/G proposed in the PNEEPEI (2008) document is strongly influenced by this model. The HA/G is covered by the Special Education guidelines (Law no. 9,394, of December 20, 1996; Decree no. 7,611, of November 17, 2011), with the aim of guaranteeing children access to specialized services. This means that it is the school’s role to prepare to meet their needs and particularities.

Regarding inclusion policies, it is understood that interpersonal development (specifically empathy skills and prosocial behaviors) is an indispensable component of this inclusive process. The goal is to improve the quality of social relationships by promoting attitudes of understanding and acceptance of differences by peers, teachers and school staff. Considering, then, the importance of acquiring and maintaining these skillful behaviors, the school needs to invest in the interpersonal development of students, and even of teachers, as they mediate classroom relationships and conflicts (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2013).

Castro and Bolsoni-Silva (2008) state that, in fulfilling this role, teachers can maintain, strengthen or even discourage behaviors related to child-child and child-teacher interaction, influencing both academic and social aspects. According to Bandeira and Quaglia (2006), to be successful, children need to have assertive behaviors, as this contributes to improve interpersonal communication, expressing feelings and needs. However, it is up to the teacher to identify such behaviors, seeking to stimulate them in different situations.

From this perspective, it is undeniable that educational systems should equally prioritize the development of social skills of all their students, whether or not this target population is from the Special Education area. From the beginning of schooling, the educational environment should favor and enhance the social and academic development of students in view of an adequate formation for life in all its unfolding.

Assuming that child behavior is the result of the child’s behavioral history in the environments in which he/she lives and is also maintained by family environmental contingencies, in addition to teachers, it is essential to work with parents and/or guardians (Silvares, 1993). In this sense, Bolsoni-Silva and Loureiro (2011) compared the parenting practices and child behavior of two groups of children, clinical and non-clinical, for behavioral problems. The results showed that the behaviors that differentiated the groups were, above all, those related to positive parenting practices and children’s social skills, confirming the influence of family environmental contingencies pointed out by Silvares (1993). Family support acts as a protective factor and a promoter of resilience and with children with HA/G is no different, as it is fundamental for the development of talent (Chagas, 2008; Chagas & Fleith, 2009; Dessen, 2007).

There are authors who suggest that talented young people, especially those with extreme abilities, are more vulnerable to emotional and social problems and higher risks for depression, anxiety and suicide (Alencar, 2007; Antipoff & Campos, 2010; Cassady & Cross, 2006; Chagas & Fleith, 2010; Mirnics, Kovia, & Bagdy, 2015; Peterson, 2009). The development of their skills, quality of life, success or self-realization therefore depends on a complex set of individual and environmental variables (Chagas & Fleith, 2010). Therefore, an intervention focused on this area can help to prevent or reduce these deficits and mismatches (Matos & Maciel, 2016) and ideally this should be done as early as possible.

Chagas and Fleith (2010) have highlighted the need for broadly planned and employed activities aimed at the development of social skills in schools, especially in programs that serve this audience. To the authors, the activities should be systematically planned, aiming to help: in the strengthening and construction of positive self-image, self-esteem and selfconcept; in building an integrated identity; in developing nonviolent bullying strategies; and maintaining a positive interpersonal relationship without, however, relinquishing their skills and interests or even denying talent.

According to Del Prette and Del Prette (2013, 2017), social skills are behaviors that, in a given situational-cultural context, are highly likely to produce reinforcers for the individual and minimize aversive stimulation, contributing to the quality and effectiveness of the relationship with others. Therefore, they constitute a specific class of behaviors that an individual issues to successfully complete a social task, such as joining a group of classmates, making friends, initiating and maintaining conversation, among others.

These skills can be implemented or developed in Social Skills Training (SST) programs, which correspond to the set of planned activities that structure learning processes for social behaviors, mediated and conducted by a therapist or coordinator. In this type of program, the goal is to increase the frequency and/or improve the proficiency of already learned but impaired social skills, and to teach new and significant social skills by diminishing or extinguishing competing behaviors with such skills (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017).

Among the characteristics of people with HA/G, there are contradictions in the literature regarding the presence or absence of social skills. Some studies indicate that children with HA/G have deficits in social and emotional areas, as mentioned earlier, while other studies indicate that this population has a good repertoire of social and emotional skills (Bain & Bell, 2004; França-Freitas, Del Prette, & Del Prette, 2014, 2017; Freitas & Del Prette, 2013; Galloway & Porath, 1997; Loos-Sant’Ana & Trancoso, 2014; Prieto, Ferrándiz, Ferrando, Sánchez, & Bermejo, 2016; Versteynen, 2001).

In research conducted in national scientific databases with the keywords “social skills”, “high abilities”, “giftedness”, “high abilities or giftedness” and “talent”, no studies of social skill interventions with students with HA/G, with parents or teachers were found. The studies found describe the social skills of children with HA/G from their own reports (França-Freitas, Del Prette, & Del Prette, 2014; Loos-Sant’Ana & Trancoso, 2014) and according to the evaluation of the teachers (Freitas & Del Prette, 2013). In the international literature, studies relating the two themes were identified: social skills interventions with children with HA/G (Calero-García & García-Martín, 2005; Gómez-Pérez et al., 2014) and intervention with parents of children with HA/G on parental skills (Morawska & Sanders, 2009). Thus, this work presents unprecedented data as it was worked with three groups of participants: students, parents and teachers.

Calero-García and García-Martín (2005) performed an intervention with nine children, between 6 and 10 years old, with intellectual giftedness who, according to their parents, presented relationship problems with their peers and characteristics of introversion, distancing, critical posture and coldness. There were 10 sessions of 60 minutes each, in which the following topics were addressed: communication techniques; identification of situations of interpersonal problems; perceptions of feelings of others; empathy; ability to respond to failure; consideration of all factors present in situations of social interaction; analysis of conflict resolution options; delimitation of the consequences of actions; and planning and decision making. The results showed that children’s interpersonal skills improved significantly after the intervention.

Gómez-Pérez et al. (2014) evaluated the effectiveness of an interpersonal problem solving skills program conducted with 40 gifted children aged 7 to 13 years old divided into experimental and control groups. According to parents, children had interpersonal, behavioral and peer problems, and emotional difficulties. The program was conducted in groups in 10 sessions, using the same themes of the study conducted by Calero-García and García-Martín (2005). According to the authors, after the program, the interpersonal problem-solving skills of children in the experimental group increased, demonstrating the positive effects of the program.

Morawska and Sanders (2009) evaluated the effects of a behavioral intervention with 75 parents (divided into experimental and control group) of children aged 3 to 10 years old with HA/G. The purpose of the intervention was to improve parenting skills and to evaluate the effect of these changes on children’s social and emotional behavior. The program, developed in nine meetings, involved management skills in the areas of child development promotion, misbehavior management, and planned activities and routines to improve the generalization and maintenance of parenting skills. The results indicated significant effects of the intervention for parents of the experimental group who reported behavioral problems and hyperactivity of their children, but had no effects on the emotional environment. Parents also pointed to significant improvements in their own parenting style. The follow up, after six months, pointed to the maintenance of the positive effects of the intervention. However, according to the teachers, there were no changes in children’s behavior, except for hyperactivity. However, they had evaluated children with few behavioral problems before the intervention.

Although the subjects were not children with HA/G, Pereira (2013) coordinated a study with seven municipal schools in a city in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, with 28 teachers and approximately 700 Elementary School students, aiming to develop social skills and prevent behavior problems. Each teacher indicated up to three students with behavioral problems and three with socially accepted behaviors, who were academically evaluated. Twenty 50-minute sessions were held weekly with each class and their teachers. The themes of the intervention were: socialization, communication, expression of feelings, knowing how to defend oneself and collaboration. After the intervention, teachers reported positive points of the intervention, such as: rule making, improvement in the development of group activities and more frequent student participation. Regarding the academic performance of previously evaluated students, there was improvement after the intervention for both groups.

According to Del Prette and Del Prette (2013), comparative studies between different data sources, such as parents and teachers, can broaden the categorization and understanding of the social skills repertoire, helping to identify these behaviors in children with HA/G in different social contexts, such as school and family. The authors advocate investing in SST programs in two strands: the first as an alternative to prevention through integrated action between school and family; and the second associated with clinical interventions with the child, aimed at overcoming interpersonal difficulties and associated problems. In this work, the SST will be done considering the first strand.

Studies on the repertoire of social skills of children with HA/G are inconclusive, which justifies studies that investigate this theme with this population, in order to collect information from multiple informants: themselves; their parents and teachers. Also, there were few studies found related to interventions with this population as well as significant adults from their immediate contexts, such as family and school. It is important to test effectiveness (assessing whether or not the proposed objectives have been achieved) and efficiency (quick and least cost-effective procedure) of interventions with the child, parents and teachers, considering that they make up contexts of face-to-face interaction and extended time, which can mean a consistent improvement in the child’s development environment.

This study aimed to describe and compare the repertoire of social skills, behavioral problems and academic competence of students with HA/G: 1) according to their own account, before and after a program on social skills; and 2) according to the report of their parents/ guardians and teachers, before and after guidance on HA/G and social skills.

2 Method

Nine students with HA/G participated in Mendonça’s (2015) study, who attended the 1st, 3rd, 4th and 5th grades of Elementary School of the São Paulo state school, as well as their respective parents/guardians and teachers. Among the students, there were six boys and three girls aged between 6 and 10 (average = 8.44 and SD = 1.42). The nine students were divided into two groups6 according to the school shift: Group 1 (G1), morning students of the 3rd, 4th and 5th grades composed of three boys and two girls; and Group 2 (G2), students of the afternoon of the 1st and 3rd grades composed of three boys and one girl.

Table 1 Structure of intervention meetings with students.

| Sessions and topics | Goals | Procedures and dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - Socialization | Teach and train greeting skills; talk, ask and answer questions; introduce oneself; Reflect on differences, own characteristics and similarities, and the need to respect each other. | Make posters with rules; Dynamics: "My name is"; "Fish in the aquarium"; "Guardian Angel" and "Task Box - Role Playing". |

| 2 - Communication | Introduce the different types of communication and train communicating with classmates, expose oneself and speak in public, take the floor, make requests and listen. | Dynamics: "Telephone"; "Circle of conversation"; "What we do to one another"; "Completing the story" and "Autographs". |

| 3 & 4 - Expression of feelings | Discriminate and express feelings; Express affection and frustration appropriately and praise. | Dynamics: "Image and action with emotion cards"; "Hot Potato of Emotions"; "Secret friend"; "Expression by drawing"; "Role play" and "Indicate characteristics". |

| 5 & 6 - Self-advocacy | Know how to defend oneself from violent children, express rights, desires, preferences and needs appropriately. | Read 1st Article of the Brazilian Federal Constitution; Make informative poster about bullying and present in school rooms. Dynamics: "Human Rights Hot Potato"; "Magic words"; and "What are you like to me". |

| 7 - Self-advocacy and assertiveness |

Present the differences in behaviors: aggressive, assertive and passive. Train the skills of giving help, express opinion, working in groups, receive and criticize. | Present differences in aggressive, assertive and passive behaviors. Dynamics: "Innocent or guilty"; "Give and receive criticism". |

| 8 - Collaboration | Train the skills to offer and help, participate in groups, work in groups and participate in discussion topics, make relevant contributions. | Read the text "Os porcos espinhos" - The porcupines; Video: "The disappearance of all mothers"; Dynamics: "Taking care of the bladder"; "Neither passive nor aggressive: assertive"; "3-Senses Game: Blind, Dumb and Crippled" and "What are you like to me". |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Regarding the teachers, the eight were aged between 28 and 63 years old (average = 43; SD = 11.43) and with different levels of education: teacher-training graduate (1), university undergraduates (5) and graduates (2), who worked in regular class. They were divided into two groups according to the students under their responsibility: Group 1 (G1), four teachers of the morning period; and Group 2 (G2), four teachers of the afternoon period.

Among those responsible for the child, five were mothers, one grandmother and two fathers, aged between 30 and 56 (mean = 39.75; SD = 9.93). Regarding the academic level, one mother had completed Elementary School, five with completed High School and two with completed Higher Education. The parents/guardians were divided into two groups according to their children’s groups: Group 1 (G1), five parents/guardians of the morning students; and Group 2 (G2), three parents/guardians of the afternoon students. The person responsible for student 4 did not participate in the intervention.

2.1 Locality

The interventions were carried out on the premises of the school, which attends students from the early grades of Elementary School, located in a suburb of a city in the hinterlands of São Paulo State.

2.2 Instrument

Social Skills Rating System (SSRS): It is a scale originally produced in the USA (Gresham & Elliott, 1990), which was adapted and validated for the Brazilian sample (Del Prette, Freitas, Bandeira, & Del Prette, 2016). It is presented in three versions: the teacher version assesses social skills, behavioral problems and academic competence; the parent version assesses social skills and behavior problems; and the child version assesses social skills. The results are found from the sum of the scores and transformed into percentile, according to the student’s gender.

2.3 Data collection procedure

After the research was approved by the Ethics Committee, a date was scheduled for presentation to the teachers at the time of the Collective Pedagogical Work Class (CPWC). With the parents/guardians, a meeting was scheduled in the evening. Those who expressed interest in participating ratified their consent by signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF) and the children signed the Informed Parental Consent Form (IPCF).

Data collection was conducted in four stages and had pre, posttest and followup measurements. In the first stage, after signing the informed consent forms, the teachers responded in group to the SSRS-BR version for teachers, at the CPWC time. Parents/guardians responded to the SSRS-BR group version for parents in the evening. Students responded in group, by grade and school shift, to the SSRS-BR student version. For 1st grade students, the application was individual and the researcher read the questions to the students. In the second stage, the intervention was carried out with the student groups in eight weekly meetings, and with the parents/guardians and teachers in three fortnightly meetings, with each group, separately, at times of interest of each group. In the 3rd stage, SSRS was reapplied for the three segments, students, parents/guardians and teachers. In the 4th stage, 10-12 months after the intervention, the SSRS was again applied to the students and parents/guardians. There was no application with teachers, because, with the change of year, students changed class and, consequently, teachers.

2.4 Intervention procedure with students

The SST program was offered to students in eight weekly group meetings with an average duration of 90 minutes each. The structure of the meetings was adapted from the book Habilidades Sociais e Desempenho Acadêmico: relatos, práticas e desafios atuais - Social skills and academic performance: current reports, practices, and challenges - (Pereira, 2013), as well as the proposed activities, as described in Table 1.

2.5 Intervention procedure with teachers

Three fortnight meetings lasting 90 minutes each were scheduled. The meetings took place at CPWC time. The intervention was structured based on the Illustrative Booklet: Social Skills and Education (De Oliveira, Costa, Chaves, & Souza, 2013) (Table 2). In addition to guidance, material was provided to participants on the topics.

Table 2 Structure of the intervention meetings with teachers.

| Intervention with teachers | |

|---|---|

| Themes of meetings | |

| 1st Meeting: High Abilities/Giftedness, what are they? | The concept, identification, behaviors of children with HA/G, main characteristics, curiosities, myths and truths, and schooling rights were presented. |

| 2nd Meeting: Social Skills and the importance of the environment - Strategies to develop social skills in students. | The concept and some classes and subclasses of Social Skills were presented. Skills of socialization and expression of feelings were addressed. For each of these skills, two dynamics that could be applied in the classroom with students to promote social skills in students were suggested. |

| 3rd Meeting: Social Skills and the importance of the environment - Strategies to develop social skills in students. | Skills of communication, self-advocacy and collaboration were addressed. For each of these skills, two dynamics that could be applied in the classroom with students to promote social skills in students were suggested. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

2.6 Intervention procedure with pa rents/guardians

Intervention with parents/guardians was adapted from the Father-Mother Information Handout (Bolsoni-Silva, Marturano, & Silveira, 2006). The structure of the intervention is illustrated in Table 3. There were three fortnight meetings in the evenings, lasting 90 minutes each.

Table 3 Structure of intervention meetings with parents/guardians.

| Intervention with parents and/or guardians | |

|---|---|

| Themes of meetings | |

| 1st Meeting: High Abilities/Giftedness, what are they? | The concept, behaviors of children with HA/G, main characteristics and curiosities. |

| 2nd Meeting: social skills and the importance of the environment - Strategies to develop social skills in children. | Communication skills were addressed: Start and maintain conversation, ask and answer questions; Expression of positive feelings: praise, give and receive positive feedback, thank, express and listen to opinions. |

| 3rd Meeting: social skills and the importance of the environment - strategies to develop social skills in children. | Skilled behaviors, non-skillful active and non-skillful passive skills were addressed; Negative feedback and negative feeling expression; Make and decline requests; How to deal with criticism; and Set boundaries. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

2.7 Data analysis procedure

The analyzes were conducted individually by participant and according to the instrument manual with data in percentiles. Data presentation in absolute and relative frequency refers to the two groups of students, parents/guardians and teachers, with pretest, posttest and follow-up analysis.

3 Results and discussion

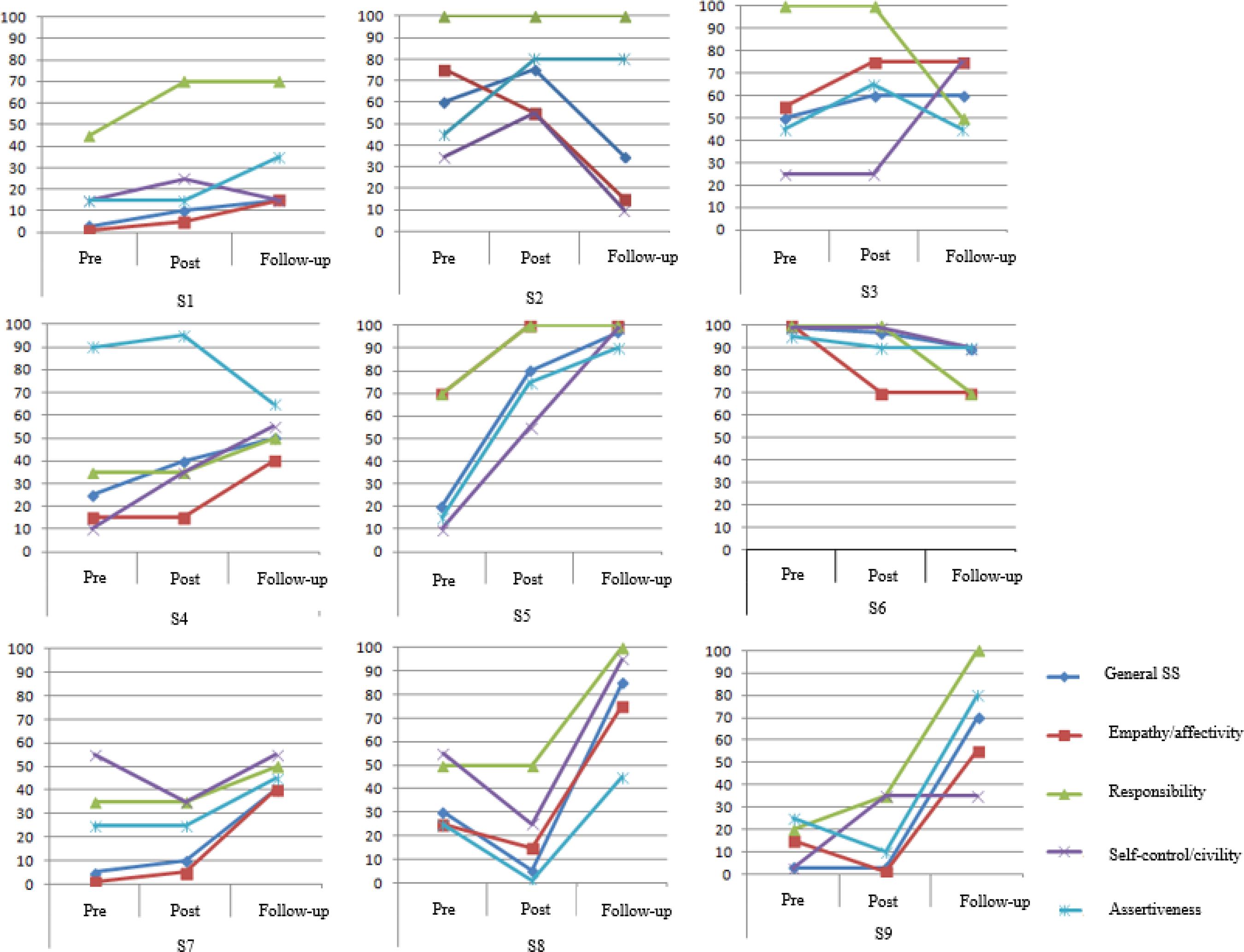

The data presented in Figure 1 show, for each Student (S), the percentiles of each factor of the SSRS-BR social skills scale according to themselves in the pre, posttest and follow-up.

Figure 1 Student Performance (S) in the three assessments (pre, posttest and follow-up) in the SSRS-BR, answered by them.Note - Social skills percentile: 0-25 = Below average repertoire; 26-35 = Average repertoire; 36-65 = Good repertoire; 66-75 = Elaborated repertoire; 76-100 = Highly elaborated repertoire.

In the pretest, eight of the nine participants had deficits (0-25 percentile) in some of the social skills factors (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S9). This data contradicts the findings of Loos-Sant’Ana and Trancoso (2014), whose minority of participants reported having belowaverage social repertoire. Still in the pretest, all presented deficits in at least three social skills factors, different from the data found by França-Freitas, Del Prette and Del Prette (2014). Their participants presented more elaborate repertoires of social skills in the factors of responsibility, assertiveness, self-control, civility and expression of positive feeling.

In the posttest that corresponds to the evaluation following the intervention, the frequency of percentile skills increased or remained in all factors for students S1, S3, S4 and S5. Six presented deficits (S1, S3, S4, S7, S8, S9) in some ability and, in the follow-up, three presented deficits in some ability (S1, S2, S9). For the other students the frequencies varied. The position of the behavioral percentile that corresponded to good to highly elaborated repertoire (36 to 100 percentile) in the posttest were: in general social skills for S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6; in Empathy/affectivity for S2, S3, S5 and S6; in Responsibility for S1, S2, S3, S5, S6 and S8; Self-control/civility for S2, S5 and S6; and in Assertiveness for S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6.

In the follow-up, it is observed that the position of the percentile of behaviors that corresponds to good to highly elaborated repertoire (36 to 100 percentile) were in general social skills for S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 and S9. Empathy/affectivity for S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 and S9. Responsibility for all students. Self-control/civility increased for students S3, S4, S5, S6, S7 and S8. Assertiveness increased for S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, and S9.

It can be considered that the intervention was relevant for some participants considering the posttest. However, considering the follow-up, some results were not maintained. With the exception of S1 and S2, it was pertinent for all participants, since the frequency of social skills increased and, consequently, the percentile position as well. This means that, after the intervention program, students presented between good and highly elaborated repertoire in social skills according to self-report, not staying at the same level for two of the participants in the follow-up.

As students had very low pretest scores, it is possible that the results observed in the posttest and follow-up may be due to the intervention with them and possibly with their teachers. According to França-Freitas, Del Prette and Del Prette (2014), responsibility was one of the most scored skills by students with HA/G. In this research, this was the ability that students reported to be more frequent in the pretest and also the one that had the most gains with the intervention, observed in the posttest and follow-up. This result is in line with the studies conducted by Bain and Bell (2004) and Chagas (2008), in which gifted and talented adolescents reported a higher frequency of behaviors indicative of responsibility in performing activities.

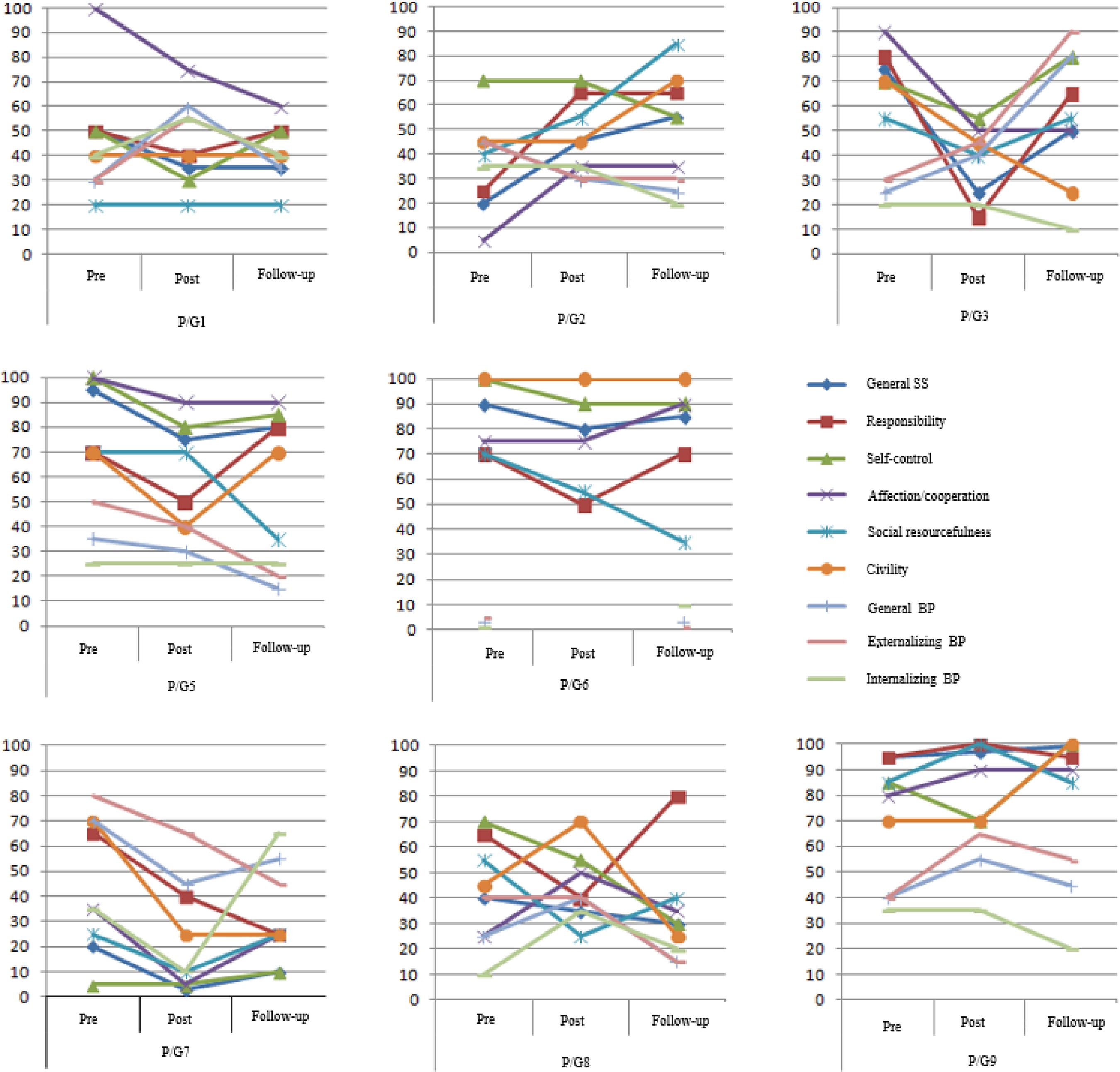

Figure 2 shows the percentile position on each factor of the students’ SSRS-BR social skills scale and behavioral problems according to their parents/guardians (P/G) in the pre, posttest, and follow-up.

Figure 2 Student Performance on Social Skills (SS) and Behavioral Problems (BP) in the three SSRS-BR assessments, answered by parents/guardians (P/G).Note - SS Percentile: 0-25 = Below average repertoire; 26-35 = Average repertoire; 36-65 = Good repertoire; 66-75 = Elaborated repertoire; 76-100 = Highly elaborated repertoire. BP percentile: 0-25 = Too low repertoire; 26-35 = Low repertoire; 36-65 = Median repertoire; 66-75 = Average repertoire; 76-100 = Above average repertoire.

Four students presented pretest deficits in some of the social ability factors (S1, S2, S7, S8), five presented deficits in the posttest (S1, S2, S3, S7, S8) and, in the follow-up, seven (S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S8). One student (S7) presented behavior problem in the pretest, considered as needing intervention. In the posttest, no student presented behavioral problems requiring intervention and, in the follow-up, one student (S3) presented it. One hypothesis for these results is that some parents/guardians became more critical of their children’s behavior after the intervention, taking as a model what or how they would like their children to behave.

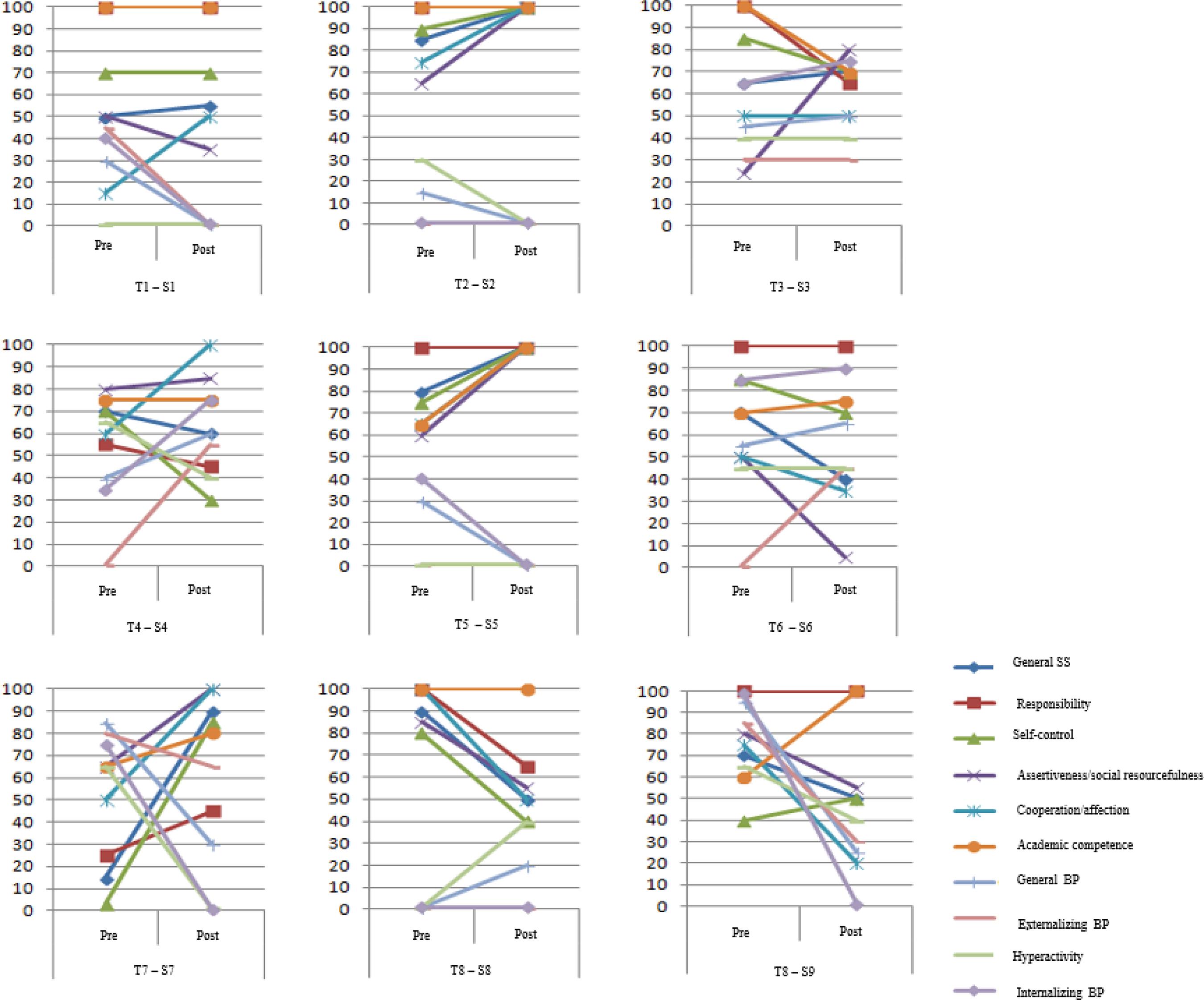

Considering behavioral problems, on the one hand, internalizers increased in the posttest and decreased in the follow-up, however, the score was still higher than in the pretest. On the other hand, according to the teachers, all student behavior problems decreased in the posttest, both internalizing and externalizing, as observed in Figure 3 further below.

Figure 3 Student Performance on Social Skills (SS), Academic Competency, and Behavioral Problems (BP) in the three SSRS-BR assessments, answered by the Teachers (T).Note - SS Percentile: 0-25 = Below average repertoire; 26-35 = Average repertoire; 36-65 = Good repertoire; 66-75 = Elaborated repertoire; 76-100 = Highly elaborated repertoire. BP percentile: 0-25 = Too low repertoire; 26-35 = Low repertoire; 36-65 = Median repertoire; 66-75 = Average repertoire; 76-100 = Above average repertoire. Academic competence percentile: 0-25 = Below average; 26-35 = Lower average; 36-65 = Median; 66-75 = High; 76-100 = Very high.

Figure 3 shows the percentile position in each factor of the students’ SSRS-BR social skills, academic competence, and behavioral problems according to their teachers (T) in the pre and posttest. Three students had pretest deficits in some of the social ability factors (S1, S3, S7), and three had pretest behavioral problems considered in need of intervention (S6, S7, S9). In the posttest, four presented deficits (S1, S4, S6, S9) and three presented behavioral problems requiring intervention (S3, S4, S6).

The teachers did pre and posttest evaluations only. The abilities with the highest posttest scores, in order of improvement, were: cooperation/affection, social assertiveness/social resourcefulness, general social skills, and self-control. Academic competence also increased posttest. Such improvements can be attributed to the intervention and also to the improved behaviors of the students who were under intervention.

Interestingly, for most participants - students, parents/guardians, and teachers - there were improvements in skillful behaviors and fewer problems in the posttest and follow-up. One hypothesis is that perhaps parents/guardians and teachers have changed their perception of students, and this may have been responsible for the improvement. Another possibility is habituation to the instrument, but after 10 and 12 months this possibility may be ruled out.

From the objectives of this study, it is observed that, in the pretest, students rated themselves worse than their parents/guardians and teachers assessed them. Also, it was observed that their parents/guardians rated them better in the pretest than in the posttest and at the follow-up. According to Skinner (1974), it is common to report that participants become more critical after an intervention.

The teachers were the ones that reported more social skills in the pretest and posttest, reporting more often than the parents/guardians, and especially more than the students themselves. The findings of Morawska and Sanders (2009) and Bolsoni-Silva and Loureiro (2016) also corroborate the fact that female teachers reported more student skills than the parents.

Considering behavioral problems, parents/guardians reported more general and externalizing behavioral problems than teachers, both in the pretest and posttest. This data corroborates the findings of Bandeira, Rocha, Freitas, Del Prette and Del Prette (2006) and Morawska and Sanders (2009) who pointed out that parents described more behavioral problems than teachers. Internalizing behaviors were more noted by teachers in the pretest and by parents/guardians in the posttest. To parents/guardians, externalizing factors decreased over time, less frequently in follow-up.

4 Final considerations

This study aimed to evaluate the repertoire of social skills, behavioral problems and academic competence of students with HA/G, before and after an intervention program on social skills, developed with the three segments. It was used a universal intervention, focused on age-related issues and common problems present in the relationships between the three segments. Changes were observed, especially in the students’ own reports; in the follow-up, to parents/guardians there was an improvement in responsibility and to teachers in general social skills, self-control, social assertiveness/social resourcefulness, cooperation/affection and academic competence, having the research thus achieved its objectives. A strong point of the research was to characterize the repertoire of social skills and behavioral problems of students with HA/G using, in addition to self-report, the report of their parents/guardians and teachers.

One of the limitations of the study was the small number of participants, which, although difficult to generalize the results, allows the survey and confirmation of new hypotheses. Investigating HA/G and social skills is still considered a challenge for researchers, with several gaps to be filled and deepened. In this sense, this study could contribute to the area as it points out that students with HA/G reported having social skills, but had deficits in some areas, which was also reported by their parents/guardians, justifying the intervention performed. A suggestion for future studies is, from initial data, to propose programs focused on social skills, thinking of practices that minimize problems and expand the skillful repertoire. The teacher’s participation proved indispensable in the process, as they need strategies to promote inclusive environments for this population.

Importantly, in PNEEPEI (2008), Specialized Educational Assistance (SEA) is foreseen for this population, intervention programs of this nature could be developed in the context of the articulation of Special Education with the other teachers of the common room, aiming at the development of general and/or specific skills, as needed and individual demands of each student.

The results indicated that, with the intervention, it was possible to improve the skillful repertoire of some participants in some factors. In terms of implications for interventions with teachers and parents/guardians, it can be pointed out the need for more encounters, both with the theme of HA/G, as with social skills.

Finally, in light of these findings, some suggestions for future research are listed to deepen the understanding of social skills in this population: 1) Assessment of children’s social skills repertoire by their peers (sociometric assessment); 2) Evaluation of social competence through research using observational methods of social behavior, such as self-records, cursive registration and video recording; and 3) Characterization of the repertoire of social skills and behavior problems in individuals with HA/G in another age group, such as adolescents and adults.

2This paper presents part of the results of the first author’s Master’s thesis, entitled Habilidades Sociais e Problemas de Comportamento de estudantes com Altas Habilidades/Superdotação: caracterização, aplicação e avaliação de um programa de intervenção (Social Skills and Behavior Problems of Students with High abilities/ giftedness: characterization, application and evaluation of an intervention program), with the collaboration of the other authors. The study was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP).

6Participants (students, parents/guardians and teachers) were divided into groups (G1 and G2) according to the schedule for participation in the interventions. Data were analyzed without this division of groups G1 and G2.

REFERENCES

Alencar, E. M. L. S. (2007). Características sócio-emocionais do superdotado: questões atuais. Psicologia em Estudo, 12(2), 371-378. [ Links ]

Antipoff, C. A., & Campos R. H. F. (2010). Superdotação e seus mitos. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 14(2), 301-309. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-85572010000200012 [ Links ]

Bain, S. K., & Bell, S. M. (2004). Social self-concept, social attributions, and peer relationships in fourth, fifth, and sixth graders who are gifted compared to high achievers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(3), 168-178. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620404800302 [ Links ]

Bandeira, M., & Quaglia, M. A. C. (2006). Comportamento assertivo: relações com ansiedade, lócus de controle e autoestima. In M. Bandeira, Z. A. P. Del Prette, & A. Del Prette (Eds.), Estudos sobre habilidades sociais e relacionamento interpessoal (pp. 17-46). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Bandeira, M., Rocha, S. S., Freitas, L. C., Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2006). Habilidades sociais e variáveis sociodemográficas em estudantes do ensino fundamental.Psicologia em Estudo, 11(3), 541-549. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722006000300010 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., & Loureiro, S. R. (2011). Práticas educativas parentais e repertório comportamental infantil: comparando crianças diferenciadas pelo comportamento.Paidéia, 21(48), 61-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2011000100008 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., & Loureiro, S. R. (2016). Simultaneous assessment of social skills and behavior problems: Education and gender. Estudos de Psicologia Campinas, 33(3), 453-464. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752016000300009 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., Marturano, E. M., & Silveira, F. F. (2006). Cartilha informativa. Orientação para pais e mães. São Carlos: Suprema Editora. [ Links ]

Calero-García, M. D., & García-Martín, M. B. (2005). Habilidades interpersonales y afrontamiento al fracaso: un método de entrenamiento para niños superdotados. Revista electrónica mente y conducta en situación educative, 2(1), 1-10. [ Links ]

Cassady, J. C., & Cross, T, L. (2006). A factorial representation of suicidal ideation among academically gifted adolescents. The Journal of the Education of the Gifted, 29(3), 290-305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320602900303 [ Links ]

Castro, A. B., & Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2008). Habilidades sociais na educação: relação entre concepções e práticas docentes na educação infantil. In V. L. M. F. Capellini (Ed.), Políticas públicas, práticas pedagógicas e ensino-aprendizagem: diferentes olhares sobre o processo educacional (pp. 296-311). Ed. Bauru: Cultura Acadêmica. [ Links ]

Chagas, J. F. (2008). Adolescentes talentosos: características individuais e familiares (Tese de Doutorado). Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brasil. [ Links ]

Chagas, J. F., & Fleith, D. S. (2009). Estudo comparativo sobre superdotação com famílias em situação sócio-econômica desfavorecida. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 15(1), 155-170. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-65382009000100011 [ Links ]

Chagas, J. F., & Fleith, D. S. (2010). Habilidades, características pessoais, interesses e estilos de aprendizagem de adolescentes talentosos. Psico-USF, 15(1), 93-102. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712010000100010. [ Links ]

De Oliveira, A. P., Costa, L. A., Chaves, P. B., & Souza, S. S. de. (2013). Cartilha Ilustrativa: Habilidades Sociais e a Educação. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 7.611, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Recuperado em 20 de dezembro de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2011/Decreto/D7611.htm [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette A. (2013). Psicologia das habilidades sociais na infância: teoria e prática. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2017). Competência social e habilidades sociais: manual teóricoprático. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., Freitas, L. C., Bandeira, M., & Del Prette. A. (2016). Inventário de habilidades sociais, problemas de comportamento e competência acadêmica para crianças - SSRS: manual de aplicação, apuração e interpretação. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Dessen, M. A. (2007). A família como contexto de desenvolvimento. In D. S. Fleith (Ed.), A construção de práticas educacionais para alunos com altas habilidades/superdotação. O aluno e a família (pp. 13-28). Brasília: MEC/SEESP. [ Links ]

França-Freitas, M. L. P. de., Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2014). Social skills of gifted and talented children. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 19(4), 288-295. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2014000400006 [ Links ]

França-Freitas, M. L. P. de, Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2017). Habilidades Sociais e Bem-Estar Subjetivo de Crianças Dotadas e Talentosas. Psico-USF, 22(1), 1-12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712017220101 [ Links ]

Freitas, L. C., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2013). Habilidades sociais de crianças com diferentes necessidades educacionais especiais: Avaliação e implicações para intervenção. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 31(2), 344-362. [ Links ]

Galloway, B., & Porath, P. (1997). Parent and teacher views of gifted children’s social abilities, Roeper Review, 20(2), 118-121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02783199709553872 [ Links ]

Gómez-Pérez, M. M., Mata-Sierra, S., García-Martín, M. B., Calero-García, M. D., Molinero-Caparrós, C., & Bonete-Román, S. (2014). Valoración de un programa de habilidades interpersonales en niños superdotados. Revista Latinoamericna de Psicologia, 46(1), 59-69. [ Links ]

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [ Links ]

Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Recuperado em 20 de dezembro de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm [ Links ]

Lei nº 12.796, de 4 de abril de 2013. Altera a Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional (LDB), para dispor sobre a formação de profissionais da educação e dar outras providências. Recuperado em 20 de dezembro de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2013/Lei/L12796.htm [ Links ]

Loos-Sant’Ana, H., & Trancoso, B. S. (2014). Socio-Emotional Development of Brazilian Gifted Children: Self-Beliefs, Social Skills, and Academic Performance. Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies, 6(1), 54-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18085/llas.6.1.g438862334102t30 [ Links ]

Matos, B. C., & Maciel, C. E. (2016). Políticas Educacionais do Brasil e Estados Unidos para o Atendimento de Alunos com Altas Habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD).Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 22(2), 175-188. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-65382216000200003 [ Links ]

Mendonça, L. D. (2015). Identificação de alunos com altas habilidades ou superdotação a partir de uma avaliação multimodal (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Estadual Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Bauru, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Mirnics, Z., Kovia, Z., & Bagdy, E. (2015). Mental Health Promotion and Prevention Among Gifted Adolescents. Recuperado em 20 de dezembro de 2019 de https://www.futureacademy.org.uk/files/menu_items/other/v17.pdf [ Links ]

Morawska, A., & Sanders M. R. (2009). Parenting gifted and talented children: What are the key child behaviour and parenting issues? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(9), 819-827. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802277271 [ Links ]

Pereira, V. A. (2013). Habilidades sociais e desempenho acadêmico: relatos, práticas e desafios atuais. Dourados: UFGD. [ Links ]

Peterson, S. J. (2009). Myth 17: Gifted and talented individuals do not have unique social and emotional needs. Gifted Child Quarterly, 53(4), 280-282. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986209346946 [ Links ]

Política nacional de educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva. (2008). Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP. [ Links ]

Prieto, M. D., Ferrándiz, C., Ferrando, M., Sánchez, C., & Bermejo, R. (2016). Inteligencia emocional y alta habilidad. Sobredotação, 15(1), 35-56. [ Links ]

Renzulli, J. S. (1998). The three-ring conception of giftedness. In S. M. Baum, S. M. Reis, & L. R. Maxfield (Eds.), Nurturing the gifts and talents of primary grade students (pp. 50-72). Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press. [ Links ]

Renzulli, J. S. (2011). What Makes Giftedness?: Reexamining a Definition. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(8), 81-88. [ Links ]

Silvares, E. F. de M. (1993). Por que trabalhar com a família quando se promove terapia comportamental de uma criança. Artigo apresentado na 2ª Jornada Clínica Comportamental, Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1974). Sobre o Behaviorismo. São Paulo: Cultrix. [ Links ]

Versteynen, L. (2001). Issues in the social and emotional adjustment of gifted children: what does the literature say? The New Zealand Journal of Gifted Education, 13(1), 1-8. [ Links ]

Received: August 05, 2019; Revised: September 01, 2019; Accepted: September 08, 2019

texto em

texto em