1 Introduction

The Salamanca Statement, although signed a quarter of a century ago, contains many revolutionary provisions that have not yet been implemented in social practice. The most important of them is the postulate to organize high-quality education for all students, preferably in mainstream schools, close to the child’s home. The document indicates this strategy of action as the most effective in reducing discrimination and building social cohesion. It describes the most important elements, the realization of which is crucial to the implementation of the described idea of inclusion, including: changing thinking about special educational needs (SEN), using flexible curricula, providing appropriate human and material resources, building local partnerships and cooperating closely with parents, and promoting good practices based on scientific research. Poland undertakes intense activities aimed at implementing the provisions of the Salamanca Statement. However, in order to reliably describe the status quo, we should take into account the history of SEN and disability policies in Poland (to see the effort already made), and then identify the most important challenges that Poland will face while continuing the implementation of the document’s guidelines.

The article shows a systemic approach to the implementation of the idea of inclusion not only as an assumption of high-quality education for all students, but also as a principle of functioning of a society of equal opportunities. Inclusive education in Poland, based on a continuous process of functional diagnosis, in which the potential of each student is recognized and conditions for their optimal development are created - may be an example of an effective strategy for changing social mentality and educational practices. School may be perceived as an environment conducive to learning, and not as an oppressive space limiting an individual (and such connotations are still very strong in Poland - a post-communist country). The presentation of functional diagnosis in a new, broad paradigm of assessment of subject’s behavior (significantly exceeding the framework of social adjustment assessment) is an attempt to implement good practices in the field of special pedagogy and clinical psychology into the mainstream of education.

2 Path to inclusion - review of achievements

The education of students with SEN in Poland has a long and exceptionally well-established tradition. Though the first schools for children with disabilities were founded in the late 19th century (e.g. the Deaf-Blind Institute in Warsaw - 1818), the real groundbreaking changes appeared after regaining independence, in the 1910s and 1920s. On the 7th of February 1919, a Decree on compulsory schooling was announced which stated that education is free and obligatory to all children up to the age of 14 (7th grade). Children and adolescents with disabilities might have attended special schools - if they were available in a given area - or could have been waived from compulsory schooling due to the severity of their disability. A serious problem of that time was a lack of educational institutions for children with disabilities, and a lack of qualified teachers. This call for action was answered by Maria Grzegorzewska - regarded as a founder of Polish SEN pedagogy - who opened the State Institute of Special Education in Warsaw (PIPS, 1922), where professional teachers were prepared for work in new state special schools for students with disabilities which were established all over the quickly developing country. Starting from 8 schools in 1921, in 1939 there were about 104 such schools (Lipkowski, 1981, p. 74), led by both state and charity organizations, mainly connected with the Catholic Church.

Though such segregated institutions might be regarded as discriminatory today, at that time they were a sign of enlightenment and sophisticated care for children with SEN. Grzegorzewska was a leading humanist of her time and her belief that there is not an invalid; there is a human being has been the guiding principle of thousands of PIPS graduates. In the 1930s, a less segregated school environment emerged. In mainstream schools, classes for “less able” children were established so that they did not have to live in faraway boarding schools. Unfortunately, WWII (1939-1945) destroyed a vast amount of Poland’s human capital and historical records. But it was also a time of great heroism of teachers and pedagogues, among them Janusz Korczak, who assisted ill and orphaned children until a Nazi gas chamber ended his life.

The next decades brought more development in SEN education. The number of special schools was systematically growing and the first kindergartens for children with disabilities appeared (Marcinkowska, 2015). Modern teaching methods were introduced, like Decroly’s method of “work centers”, Freinet or Montessori’s model of teaching. Alongside these, Polish pedagogues continued their work directed at disabled and disadvantaged children (Radlińska, Obuchowska and Sękowska among them). General education in special schools and centers was typically available for students with mild, moderate and severe levels of disability (those with profound levels were still excluded from the educational system, receiving only medical and social care either at their homes or in special care homes). Lipkowski (1981) reported that in 1975 there were 664 special schools in Poland which provided education for 88,692 students. However, many more children needed provision, and especially in the rural areas, children with disabilities were still waived and received no support other than basic care from their family members.

The transformation of 1989 brought both qualitative and quantitative changes to Polish education. The Regulation of the Ministry of Education from 1993 on organizing care and education for disabled students in state schools (Dz. Urz. 15.11.1993) created a possibility - for the first time in Polish history - to design integrated classes. Integrated settings were possible in any school where 3 to 5 children with disabilities were placed in one group together with their non-disabled peers. Such integrated groups were smaller in size (e.g. 16-18 instead of 25-30 children in a group) and have an assistant teacher working mainly with this group of children with SEN. Wherever the number of SEN children in one group was smaller - e.g. 1-2 students per group -, it was not possible to hire an assistant teacher and reduce the number of children in a group. This solution was revolutionary for that time but nowadays is regarded as a subtle form of segregation, an injustice in educational opportunities, as students diagnosed as having SEN were not allowed to enter their local mainstream school but were forced to look for such a setting in different parts of their town or country.

However, the creation of integrated classes was a natural consequence of greater social awareness of disabled children’s rights to be educated with their peers in their local communities, not in special schools. Learning experience of disabled and non-disabled students up till 1990’s had been provided either voluntarily by some state schools (depending on the decision of the headmaster) or some private schools which had their own rules. The international trends also played a key role in these changes, among them the Salamanca Statement (1994) and a Polish document, the Charter of Rights of Disabled Persons (1997). Some older approaches, like normalization, which were known in the Western world since the 1950s, made their way into Poland at that time too and shaped the national research and education policy (Krause, 2005). Normalization in Poland of the last decade of XX century was an influential approach showing equal rights of people with disabilities for education of a high quality together with non-disabled peers and adult life opportunities, like having a job or right for independent living. Though it started from fighting for independent life possibilities of people with motor disability, this movement soon started to mean a fight for equal - normal - rights in every life domain for people with different SEN and disabilities, even the most complex ones. The year 1997 brought one more important milestone - a regulation that enabled children and adolescents with profound intellectual disability (who had only been offered medical and social care) to exercise their right to education and attend classes. This regulation lasted for more than a decade, which was characterized by a systematic growth in the numbers of SEN children in integrated and mainstream settings and a diminishing number in special institutions. Students with SEN (apart from those with moderate to severe learning disabilities who have their individual programs) have to follow the national core curriculum, with the necessary modifications and adaptations.

The Educational Reform of 1999 acknowledged the right of children with disabilities to be educated either in special settings or in integrated or mainstream ones. It brought forth Ministry of Education regulations that obliged special institutions to carry out a multi-disciplinary assessment of each child’s functioning which was to include specialist psycho-pedagogical support. Educational teams (e.g. psychologist, school counselor, class teacher) in integrated schools were obliged to design an individual plan for each child in which their special needs were identified and their integrated forms of support were written down in Educational and Therapeutic Individual Plans justified, monitored and evaluated.

Currently, there are 3 types of schools for SEN students in Poland:

special schools for children and youths with particular disabilities (e.g. schools for deaf and hard of hearing children and youths, schools for visually-impaired students, schools for students with moderate and severe intellectual disability, and schools for students with multiple disabilities);

integrated schools (or schools with integrated classes): classes are smaller than in mainstream schools. The maximum class size is 20 students, among which 3 to 5 may be students with disabilities. There is a support teacher in the classroom for several hours a week;

mainstream schools: children can attend them if it is their district school or if they choose it voluntarily, providing there is a formal possibility for enrolling children from outside the district.

Each of these institutions (special, integrated, and mainstream) is obliged to provide the student with necessary adjustment and modification detailed in the assessment documentation.

In 2010, the Ministry of Education issued a set of regulations for improving the quality of SEN education. They identified 11 categories (which are grouped into 2 main categories) of students who are entitled to psycho-pedagogical support. The first main category is for students with disabilities and students with potential or actual social maladjustment. Schools are obliged to design for such students a personalized individual educational and therapeutic program. The basis for such support is a multi-disciplinary assessment prepared by a team of professionals (psychologist, school pedagogical counselor, teachers and others as necessary), together with the parents. Students from the second main category include those with specific and non-specific learning difficulties, school failure, somatic illness, language problems connected with migration, and behavior and emotional disorders; it also encompasses students from minority groups and gifted and talented pupils. The educational needs of this group are to be assessed by their teachers and other professionals as needed, and the school is obliged to provide these students with the required support. These documents were amended and extended in 2013 and 2017, and the most significant change was the addition of a possibility to employ an educational assistant for children with complex needs.

Nowadays, it is more and more obvious that this type of assessment should be functional in its nature and support has to be offered to all children, not only to those with medical diagnoses, as the following sections highlight. Thus, an important element of inclusion is functional assessment that is understood less as a formalized diagnosis and resource allocation and more as a continuous, ongoing process provided at school as the basis for individualized educational planning. Such assessment does not single out any pupils but is an instrument of promoting the learning of all pupils as far as possible (Watkins, 2007). The aim of assessment in an inclusive approach is therefore to provide formative feedback for the learner to identify where he or she is on the way to achieving a particular educational goal. The assessment identifies current achievements in relation to the individual resources and capabilities of the subject and provides a starting point for designing further actions in the area under assessment. Therefore, it also has a designing function.

2 Inclusion - a principle, process and result

Last few years in Polish education have been marked by intensive social and educational changes and a search for new solutions to be offered to the growing number of students with diverse special needs. Among the most important changes are the following: 1. Growing awareness of the rights of children with SEN and disabilities to a good quality education; 2. Demographic changes that diminished the number of schoolchildren in general; 3. Better assessment procedures and strategies that made it possible to diagnose a child’s needs early4; 4. Early system of support for children at risk of disability5; and 5. Extensive system of in-service SEN/disability training for teachers and careers.

If the 1990s was a time for the emergence of children with disabilities from their homes and special schools and their regular appearance in integrated schools, the next decade was marked by the wider admission of children with disabilities into mainstream schools. This new situation started to be named “inclusion” or “educational inclusion”, understood as the process and state of including children with SEN/disabilities into regular classes with non-disabled children, without labeling them as integrated classes. The situation created a little confusion as to the meaning of “integrated” and “inclusion” settings6 and it is not always clear what forms of support should be provided for which groups of children.

Nowadays a deeper meaning of inclusion has been slowly discovered. In 2018, the Polish Ministry of Education (MEN) started preparations for introducing a new Educational Act which is going to be proclaimed in 2020. Several projects have been undertaken to facilitate this process, among them new standards for teacher education introduced in August 2019. The MEN also launched a project with the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE) called Improving the quality of inclusive education in Poland, which aims at diagnosing the strengths and weaknesses of the present system and formulation of the recommendations for future developments. Stronger collaboration with universities educating future teachers has been strongly advocated for (Domagała-Zyśk, 2018a; Deppler, 2006).

The key issue is to define educational inclusion, and inclusive schools and practices, precisely. Not diminishing the significance of the common notion of inclusion as a process of overcoming barriers and supporting disadvantaged students to access mainstream education, there is an argument for recognizing United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO, 2009) definition of inclusion:

a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all children, youth and adults through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities, and reducing and eliminating exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies, with a common vision that covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children. (UNESCO, 2009, p. 8-9).

Other definitions of inclusion: “[the] process of strengthening the capacity of the education system to reach out to each learner” (UNESCO, 2017a, p. 7) and designing good education for every student (Domagała-Zyśk, 2019b). In this way, inclusion can be differentiated from integration, which seems to be similar in its meaning to mainstreaming, understood as “the practice of educating students with learning challenges in regular classes during specific time periods based on their skills” (UNESCO 2017a, p. 7).

Inclusion is thus seen as being not only about special needs or disability, but also about overcoming barriers and searching for resources to support learning and participation (Ainscow & Cesar, 2006). Inclusion is also about all students vulnerable to exclusionary pressures which in the Polish context may mean e.g. students from poorer villages or immigrant families.

4 Functional diagnosis

Functional diagnosis appears in the psychological and pedagogical diagnosis in the context of functional behavioral assessment (FBA). Usually this assessment concerned maladaptive activities that are incompatible with the applicable group rules. That is why the FBA model refers to the risk of social maladjustment, usually omitting the analysis of positive behaviors. A comprehensive model of functional diagnosis, verified in longitudinal studies, was presented by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman and Richman (1994). This model includes information about: the reasons for the difficult behavior (A, antecedents); behavioral characteristics (B, behavior); and information on the effects of behavior (C, consequences) (Gresham, Quinn, & Restori, 1999). This ABC diagnosis is to determine the function that the given behavior serves in the overall operation of the person. It is worth emphasizing the dual meaning of the concept of “function”, understood as: a) the so-called “difficult behavior” that allows you to deal with a given problem in a short time (reasoning); and b) behavior that affects other structures and functions (inference about consequences).

The inclusive education model implemented in Poland has been based on such a multidimensional functional diagnosis, recognizing:

the state of the person’s functioning in the environment, regarding the description and identification of the sources of their current behavior (including manifested resources and deficits);

the possibilities for the integral and sustainable development of the person, both in terms of realizing their development potential and modifying the environment in which they operate (Domagała-Zyśk, Knopik, & Oszwa, 2018).

This means that in the functional diagnosis (in accordance with the paradigm of the description of human functioning presented in the International Classification of Functioning [ICF]), the postulate of both therapeutic and developmental work aimed at enriching the resources and competences of the student, as well as implementation of modifications in the learning environment, is taken into account. For example: a student with dyscalculia works on mastering basic arithmetic skills. Alongside this, his/her teachers are simultaneously implementing supportive environmental adjustments, e.g. visualization of task content; integration of mathematical content into the natural space of the school, e.g. description of stairs, windows as geometric figures; visualization of angles by means of door tilt degrees, etc. The parents and teachers’ activities aim also at strengthening the child’s social and emotional competences, like efficacy, self-esteem, coping skills, interpersonal skills. These two paths should lead to positive consequences understood as the student’s integral development appropriate to his/her age and life situation.

This understanding of functional diagnosis underlines the importance of the person’s potential, which is in line with the trend of positive psychology that has been popularized for several decades. This is how Martin Seligman, a pioneer of positive psychology, refers to this tendency:

The new century challenges psychology to shift more of its intellectual energy to the study of the positive aspects of human experience. A science of positive subjective experience, of positive individual traits, and of positive institutions promises to improve the quality of life and also to prevent the various pathologies that arise when life is barren and meaningless. The exclusive focus on pathology that has dominated so much of our discipline results in a model of the human being lacking the positive features, which make life worth living. Hope, wisdom, creativity, future mindedness, courage, spirituality, responsibility, and perseverance are either ignored or explained as transformations of more authentic negative impulses. (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2001, p. 31).

Previous psychological and pedagogical support in Poland was focused mainly on deficits and disabilities, which almost completely removed the resources and abilities of students from the field of view (Knopik, 2018a).

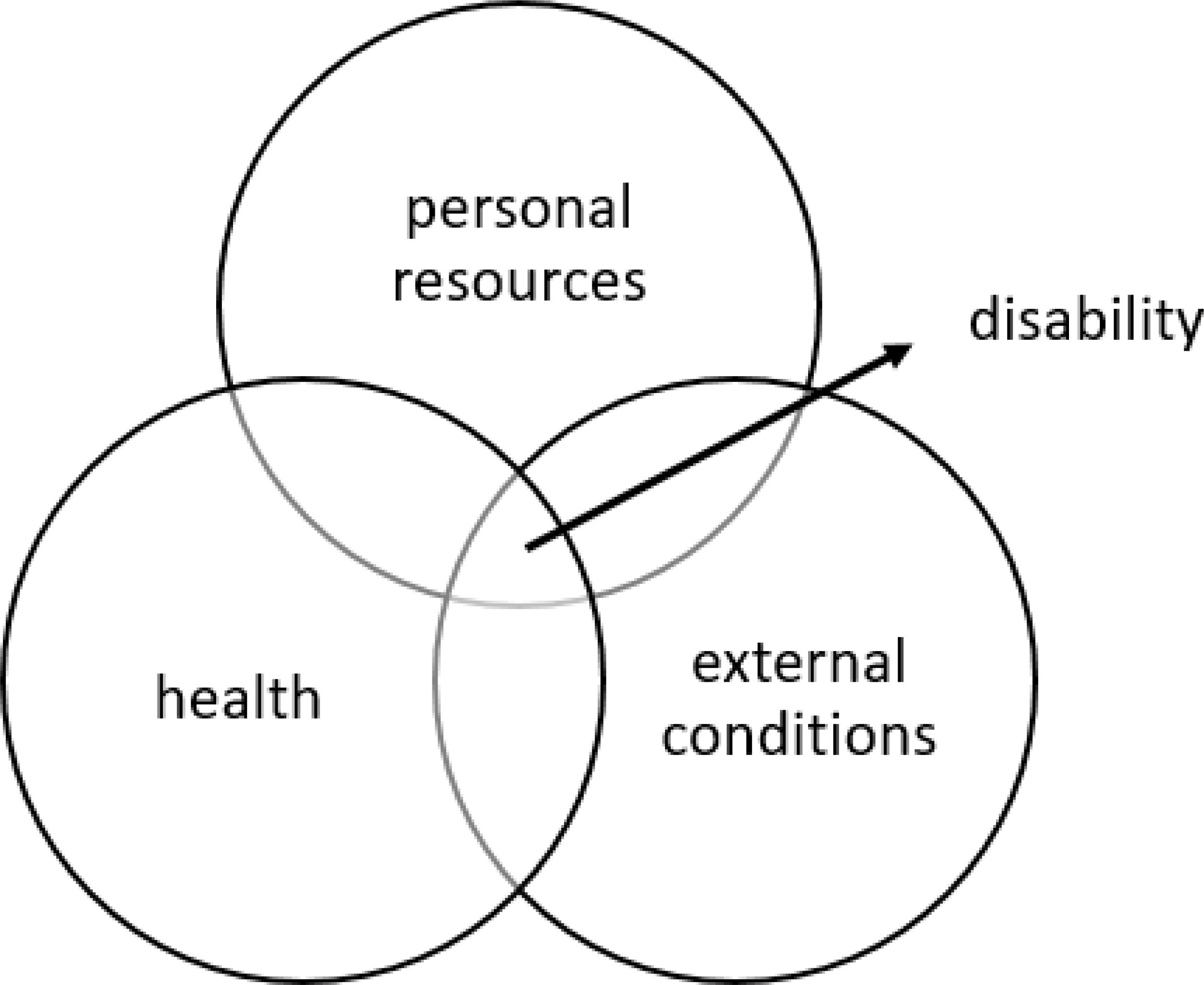

Such new understanding of functional diagnosis and pedagogical support for SEN/disabled students means not only a significant change in Polish educational practice, but is required in the process of implementation of the WHO relational definition of disability, which in the ICF was formulated as follows: “Disability is characterized as the outcome or result of a complex relationship between an individual’s health condition and personal factors, and of the external factors that represent the circumstances in which the individual lives” (ICF, 2009, p. 15).

As depicted in Figure 1, this biopsychosocial definition of disability (which is somewhat in opposition to the medical definition) articulates the following issues: a) it is not only human health that implies disability; b) important elements of the person’s resources regulating the degree of disability are, apart from the health status, personal factors including cognitive resources, values, interests, hobbies, and emotional and social competences; c) disability is a phenomenon that “happens” in the space of social relations; d) disability is not a chronic condition, because its dynamics and intensity depend on health, current resources, and the opportunities and barriers created by the environment.

The formal basis for the framework of functional diagnosis is the Regulation of the MEN of 9 August 2017 on the principles of psychological and pedagogical support, which defines the tasks of this intervention:

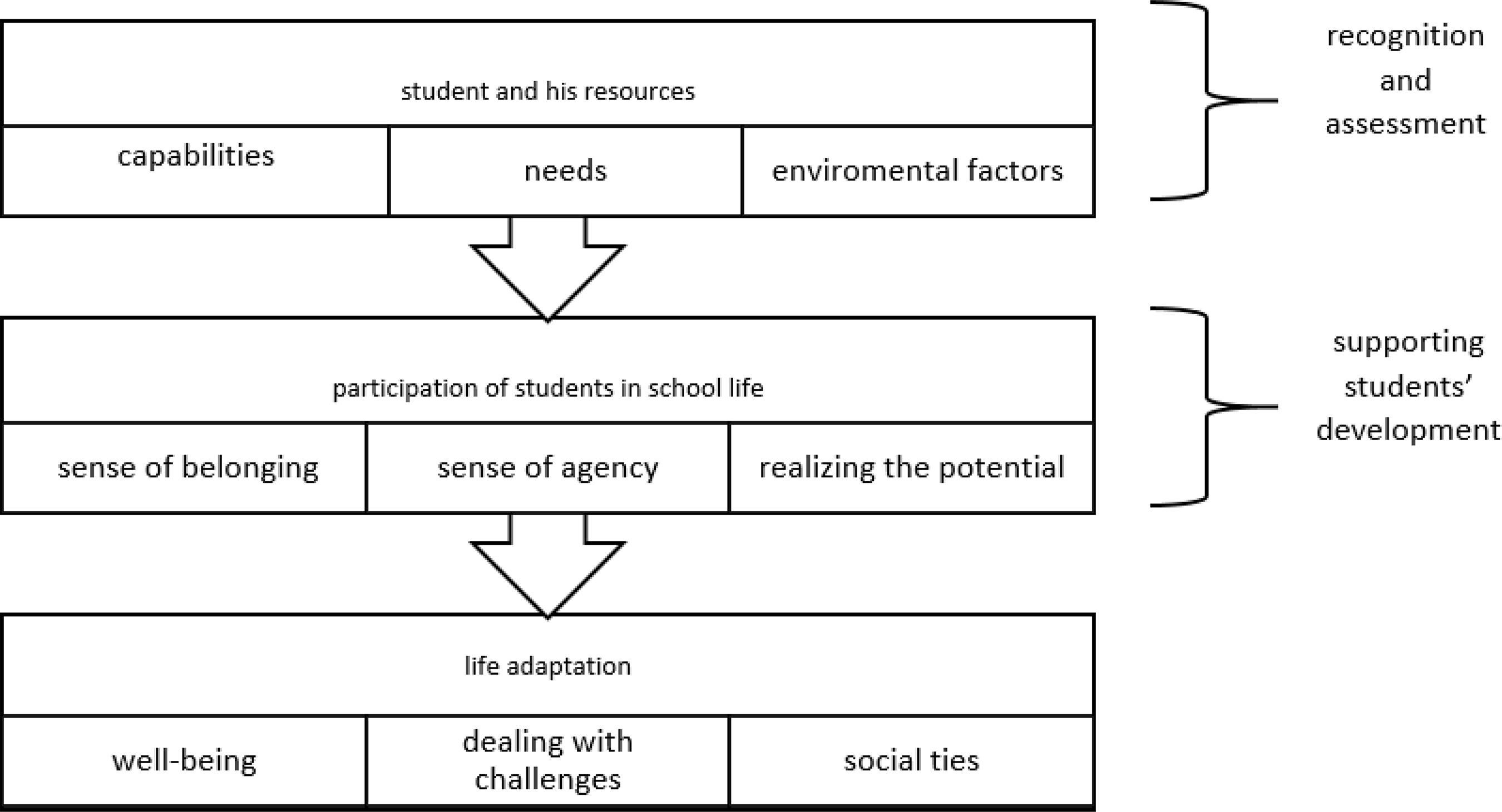

recognizing and satisfying the individual developmental and educational needs of a student and recognizing individual psycho-physical abilities and environmental factors influencing his functioning in kindergarten or school in order to support his development potential and create conditions for his active and full participation in the life of the kindergarten or school as well as in the social environment (MEN, 2017).

This definition emphasizes the following issues:

demarcation of developmental and educational needs;

demarcation of the student’s needs and abilities;

distinguishing personal factors (abilities, predispositions, and talents) from environmental factors (affecting the child’s functioning in school and at home);

the ultimate goal of support, which is active and full participation in the life of the institution as well as in the social environment.

The implementation of the provisions of this document in all educational institutions, although determined by law, is a process that requires systematic execution (Chrzanowska, 2018).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2 Model of psychological and pedagogical support in Poland.

Functional diagnosis is multidimensional and involves the assessment of the following areas: a) the physical and motor spheres (relating to the structural aspect of health); b) the cognitive sphere (including attention, perception, thinking, memory, imagination, speech and language); c) emotional and social sphere; d) the moral and spiritual spheres; and e) personality.

This approach allows one to interpret the function of a given behavior. For example, verbal aggression as a type of behavior should be analyzed and interpreted in the context of: biological functioning, including hormonal; cognitive efficiency; control and understanding of emotions; social support networks; preferred values and ways of spending free time; and the degree of personality and identity development.

In a functional diagnosis, the teacher or professional assumes that the student: a) is a person with an individual and unique psycho-physical structure; b) functions in a social group e.g. of family, peers, and society, and the social group that is the natural space of their development, which should be included in the assessment and support process; c) is autonomous, which is manifested, for example, by full participation in each stage of the diagnosis, with the possibility of regulating its shape and refusing further participation; d) has an individual tempo and rhythm of development (and deviation from standards does not necessarily mean pathology (Bird, 1999)); and e) is a dynamic individual who remains in a continuous development process, which means that the diagnosis itself is on-going (Knopik, 2018b).

A functional diagnosis has three stages. The first stage is called “stating diagnosis” and involves describing facts, including the student’s resources and challenges. This takes place through various measurement tools with the student’s own involvement as well as that of people representing the social context - teachers, parents, and peers (270 or 360 degrees analysis7). An important condition for this stage of diagnosis is to ensure equal access to diagnostic tools for all students, including those with sensory disabilities. Detailed guidelines have been developed in Poland for this (Krakowiak, 2017).

In order to obtain a broad view of the student’s functioning, school consultations are organized with the participation of professionals, teachers, parents and staff from psychological and pedagogical counseling centers. This stage may require a specialist diagnosis, which is performed in a counseling center.

The second stage is referred to as “guiding or designing diagnosis activities”, and includes the development of a program of remedial, preventive or pro-development activities, and then establishing a strategy for the gradual implementation of these measures in everyday school practice. At this stage, the cooperation of professionals from many fields is crucial: teachers, physiotherapists, vocational counselors, and psychologists and pedagogues from the counseling centers. It is also important to involve parents, peers and other people who are important in the student’s environment. Support corresponding to the individual needs and abilities of the student should take into account not only work in problem areas, but also general pro-development activities. Focusing on one sphere may result in lower efficiency in other areas - what was once a strength of the student may become a weakness.

The third stage is called the “verification diagnosis”, and requires an evaluation of the intervention to assess the effectiveness of the support. This stage of diagnostic work is the basis for the decision to continue it in either in the same or a modified form. It is assumed that anonymous data is collected in the central information processing system in order to conduct a continuous evaluation of the reliability and effectiveness of practices that have been used.

The functional diagnosis designed to support the model of inclusive education in Poland allows us to determine the standards of psychological and pedagogical support in the school system at the level of the individual relationship between the teacher or specialist and the student (Skidmore, 2004) and at the national level, including funding rules and policy procedures). Implementation of the idea of functional diagnosis into mainstream educational practices will not be possible without appropriate legislative changes. It is assumed that these changes will also have a positive impact on the attitudes of educational staff towards inclusion (formal facilitation will certainly provide broader opportunities in the field of practical solutions), and in the long run will improve the quality of education in general. Functional diagnosis defines “educational task” as including every kind of student (not only those with SEN or disability) and in this respect constitutes an optimal strategy for the implementation of inclusion (Armstrong, Armstrong, & Spandagou, 2011).

5 Directions of changes - challenges facing the Polish school

In creating a new Polish model of inclusion it would be worthwhile to follow the recommendations worked out in the above-mentioned project supported in 2018 by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE, 2018), which were also discussed widely with all stakeholders. The project implemented by EASNIE and MEN has been implemented in two phases:

Phase I (2017-2018) - consisted of analysis of educational law documents, interviews with stakeholders of the psychological and pedagogical support system, with the students themselves, analysis of changes in Poland’s educational policy over the last two decades, analysis of data from the Educational Information System showing quantitative characteristics of the needs of SEN or disabled students and the scope of support offered to them; this phase ended with the formulation of recommendations for the inclusive education model developed by the Ministry of Education experts.

Phase II (2019- 2020) - includes analysis performed by EASNIE experts of the draft version of the inclusive education model in Poland with the use of mapping; public consultations and small group pilot studies of effectiveness of solutions adopted in the model; the stage should end with the development of a revised model of inclusive education in 2020.

The challenges and recommendations following the first phase of the project were grouped into 5 blocks: 1. Legislation and policy; 2. System capacity building; 3. Governance and funding; 4. Monitoring, quality assurance and accountability; 5. Initial and continuing professional development opportunities; 6. Learning and teaching environments; and 7. Continuance of support. There were several challenges discussed in detail, the most important of which being the lack of a clear definition of the concept of inclusion in Polish legislation; insufficient cross-sectoral and cross-ministerial cooperation; uneven access to quality education for students with disabilities from rural and disadvantaged areas, especially for young children (Educational Research Institute [ERI], 2015); resistance to inclusive education expressed by some teachers and the necessity of including universal design for learning (Domagała-Zyśk, 2018a, 2018b). There is also much concern about the need to rationalize expenditures. Despite relatively high support from the state budget and local government unit budgets, not all needs relevant to educational outcomes are met. This is connected with a lack of clear monitoring and evaluation rules, and an absence of accountability principles and efficiency indicators with regard to SEN/disabled students (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2015; UNESCO, 2017b).

The work of the MEN on a new model of supporting SEN students has allowed them to formulate specific recommendations for changes to the psychological and pedagogical support system in order to prepare it for the implementation of inclusion. The difficulty concerns, as has been pointed out in many previous discussions (Florian, 2014; McLeskey, Waldron, Spooner, & Algozzine 2014; Qvortrup & Qvortrup, 2018), the ambiguity of the term “inclusion”. In expert work coordinated by MEN, it was assumed that “inclusion” specifies the scope of participation in education for pupils, teachers, and parents as well as local communities and other stakeholders (Booth & Ainscow, 2002). This is, therefore, a fairly broad understanding of the term, but it falls within the main recommendation of the Salamanca Conference to create a high-quality school for all. Directions of changes were determined on the basis of the Recommendation of EASNIE, formulated as Five Key Messages for Inclusive Education (2014):

As early as possible: the positive impact of early detection and intervention as well as of pro-active measures.

Inclusive education benefits all: the positive educational and social impact of inclusive education.

Highly qualified professionals: the importance of having highly qualified professionals in general, and teachers in particular.

Support systems and funding mechanisms: the need for well-established support systems and related funding mechanisms.

Reliable data: the important role played by data as well as the benefits and limitations of its use.

The following are the most important recommendations formulated as a result of the project, which will be included in the education policy after social and interministerial consultations are concluded:

Describing inclusive education standards implemented by units of the school system.

Integrating the activities of the MEN and Ministry of Health aimed at children not involved in pre-school education in order to provide diagnoses and support as early as possible.

Extending the obligatory pre-school education from one to two years, to improve the child’s preparation for school.

Upgrading the efficiency of diagnosis by developing new tools based on the assumptions of functional diagnosis and dissemination of screening tests. Currently, three teams of experts are developing batteries of standardized tests to assess the current level of students’ cognitive, emotional, social and personality development. These tests will enable the creation of an individual profile of the student’s functioning and analysis in the development process supported by therapeutic activities. The possibility of such a personalized approach reduces the risk of dictatorship of norms and subordination of each student to a statistical standard (which is often the case in the biomedical approach). From 2021, these tools will be available free of charge in psychological and pedagogical counseling centers, kindergartens, and schools.

Providing flexible support and financing without the need to apply for a ruling or opinion specifying the SEN category (as so far a ruling or opinion has been a condition for starting the support).

Developing and implementing diagnostic and post diagnostic standards at all stages of education.

Establishing SEN teams in each school, which will include professionals (e.g. special educator, speech therapist, psychologist, physiotherapist, and vocational counselor). Currently, only slightly more than 40% of schools employ a psychologist (MEN, 2018).

Promoting inclusion, encouragement and openness to differences in school curricula and textbooks, and admitting textbooks for use by the MEN on condition that they are compatible with the idea of universal design.

Launching the services of mobile professionals who will provide support to students (which is especially important for small institutions not employing specialists).

Introducing mechanisms to support the graduate’s transition to the labor market.

Implementing teacher education standards for conducting inclusive education (in agreement with the Ministry of Science responsible for Higher Education).

Introducing the possibility of employing students with SEN in educational institutions.

Organizing in every province an “exercise (experimental) school” for practical testing and implementation of innovations in the field of inclusive education.

Creating a qualification path for psychologists prepared to provide psychological and pedagogical support in the education system.

Preparing a digital platform that allows access to free diagnostic tools and the creation and updating of the student’s functional profile (based on the ICF). This platform, thanks to the continuous recording of data, will allow one to update test norms and verify psychometric properties. The system will also collect data on the effectiveness of support, which will shed light on the evidence-based best practices of inclusive education.

The proposed changes require detailed legislative solutions that are currently being developed as part of the work of several ministries. This allows us to hope for the implementation of a comprehensive system of actions, and not ad hoc, fragmented practices with too narrow a range of impact.

6 Conclusion

The transition from the medical to the biopsychosocial model in the diagnostic-therapeutic procedure represents the evolution of thinking about disability and special educational needs: from perceiving it as a permanent feature of a person to seeing it as a dynamic property of the environment that blocks the optimal functioning of a person. One of the catalysts of this process is to increase the flexibility of psychological and pedagogical support. Flexibility, as a manifestation of autonomy, requires very high competences of both professionals and teachers. Each act of autonomy, if unsupported by knowledge and skills, causes chaos and leads to mistakes and abuse. When implementing the functional diagnosis model, this key issue cannot be ignored. It should be emphasized that the rise in freedom of action should result in the increased responsibility and competence of the educational staff.

The implementation of the above recommendations is not possible without the adoption of clear diagnostic criteria, which imply not only a psychometric assessment of the student’s cognitive potential, but also an ongoing functional diagnosis of their home and school environment, potential and needs in different spheres (physical, intellectual, social-emotional, spiritual, cf no. 2, 3, 4, 6, 15), provides access to a reliable diagnosis not only for a small group of children entitled to a specialist diagnosis, but also thanks to the involvement in the diagnostic process of parents and qualified teachers - it means a diagnosis for every child (no. 5, 8 and 11), facilitates the transition to the next stages of education and to the labor market (no. 10). In addition, recommendations point to the need for cross-sectoral and cross-entity cooperation for the effective development of inclusive education. This coincides with the assumptions of functional diagnosis.

Future challenges involve following Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) in securing reasonable accommodation, individualized learning curricula, and inclusive classroom teaching in accessible learning environments for every child. Poland signed the Convention in 2012 and defended it in 2018, but there are still some areas to be improved, mainly disability and inclusion awareness among all stakeholders, especially parents of non-disabled children (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [CRPD], 2018). An important issue is also to create new teacher education programs (Forlin, 2006) that should incorporate inclusion, disability and SEN issues into every teacher training program, not only those for SEN teachers. Teachers in the context of inclusion are to be viewed not as “subject teachers”, but as “the child’s teachers”, which makes them responsible for functionally assessing the child’s needs, designing the teaching and support scheme, and evaluating its effectiveness (Domagała-Zyśk, 2019b).

In the light of the 25th anniversary of the Salamanca Statement it can be concluded that the document and the internationally recognized activities following its implementation strongly influenced attitudinal shifts in Poland and created a climate for ongoing legislative changes which should lead to creating a system of education that works for every child.