Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

versión impresa ISSN 1413-6538versión On-line ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.2 Marília abr./jun 2020 Epub 11-Mayo-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382620000100004

Research Report

Pomerisch Oder Portugiesisch Sprache?1Communicative Comprehension in Bilingual Pomeranian Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder2

3Psychologist, Specialist in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Neuropsychology, Master’s student in the Graduate Program in Psychology at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. Vitória/Espírito Santo/Brazil. E-mail: mayckhartwig@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4596-8245

4 PhD in Psychology, Professor at the Department of Social and Developmental Psychology and the Graduate Program in Psychology at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. Vitória/Espírito Santo/Brazil. E-mail: claudiapedroza@uol.com.br. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2342-1302

This is a study carried out with Pomeranian children diagnosed with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) living in the city of Santa Maria de Jetibá, in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, known as the most Pomeranian city in Brazil, where a large part of the population presents the characteristic of simultaneous bilingualism - Portuguese-Pomeranian, which has caused some challenges in the educational context. Therefore, the objective of this research was to describe behaviors that are communication indicators, based on structured interactions in Pomeranian and Portuguese Language, enabling the identification of differences in the interactions observed in L1 - Portuguese Language and L2 - Pomeranian Language. To reach the proposed goals, three male children were selected, two 9 year olds and one 10 year old, Pomeranian-Portuguese bilinguals, diagnosed with ASD at least a year before this research and accompanied by health professionals and inclusive education. This research adopts a descriptive methodology, of multiple case study type, whose data analysis method adopted was of a qualitative character, in order to comprehend the variable subjects involved in the process of communication and interaction of each case. The procedure of data collection included the presentation of Continued Storyboards), that had as the purpose to suit as visual stimulus for the child to elaborate a story. The results indicate that in the interactions performed in the Pomeranian language, the smiles, gestures, attention sharing and demonstrations of feelings were more frequent when compared to the interactions performed in the Portuguese language, which indicates that the child presents more non-verbal behavior in interactions performed in his mother tongue. Therefore, this data points to that mother tongue interactions (Pomeranian) may act in the fortification of Attention Shared abilities, a central competence for social interactions to happen.

KEYWORDS: Autism Spectrum Disorder; Communication; Bilingualism; Pomeranian language

Trata-se de um estudo realizado com crianças pomeranas diagnosticadas com Transtorno do Espectro Autista (TEA) residentes na cidade de Santa Maria de Jetibá, Espírito Santo, conhecida como a cidade mais pomerana do Brasil, onde grande parte da população apresenta característica de bilinguismo simultâneo - pomerano-português, o que tem ocasionado alguns desafios no contexto educacional. Assim sendo, o objetivo desta pesquisa foi de descrever comportamentos indicadores de comunicação, a partir de interações estruturadas em Língua Pomerana e Língua Portuguesa, possibilitando a identificação das diferenças nas interações observadas em L1 - Língua Portuguesa e L2 - Língua Pomerana. Para atingir os objetivos propostos, foram selecionadas três crianças do sexo masculino, sendo duas com 9 anos de idade e uma com 10 anos de idade, bilingues pomerano-português, diagnosticadas com TEA há pelo menos um ano antes desta pesquisa e acompanhadas por profissionais de saúde e educação inclusiva. Esta pesquisa adota uma metodologia descritiva, do tipo estudo de caso múltiplo, cujo método de análise de dados adotado foi de caráter qualitativo, a fim de compreender as variáveis subjetivas envolvidas no processo de comunicação e interação de cada caso. Os procedimentos de coleta de dados incluíram a apresentação de Pranchas de História Continuada, que tiveram como objetivo servir de estímulo visual para que a criança pudesse elaborar uma história. Os resultados indicam que, nas interações realizadas em Língua Pomerana, os sorrisos, as gesticulações, o compartilhamento da atenção e as demonstrações afetivas eram mais frequentes se comparados às interações realizadas em Língua Portuguesa, o que indica que a criança apresenta mais comportamentos não verbais nas interações realizadas em língua materna. Esse dado indica, por conseguinte, que as interações na língua materna (Pomerano), atuam no fortalecimento das habilidades de Atenção Compartilhada, competência central para que as interações sociais aconteçam.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Transtorno do Espectro Autista; Comunicação; Bilinguismo; Língua Pomerana

1 Introduction

The context of this study was with a Pomeranian population residing in the city of Santa Maria de Jetibá/Espírito Santo, Brazil, known as the most Pomeranian city in Brazil. Pomerananians descend from ancient Pomerania, located on the shores of the Baltic Sea, between the present-day Germany and Poland and the Scandinavian countries (Tressmann, 2005). The main economic activity developed in the country was agriculture (Röelke, 1996). However, the various wars and the industrial revolution had a strong impact on the work regime of the Germanic people, causing hunger, misery and unemployment (Martinuzzo, 2009), which led the Pomeranians to emigrate to other countries, including Brazil.

German immigration took place in several Brazilian regions. The first immigrants arrived in 1820 and settled in Rio Grande do Sul (Turbino, 2007). Cotrim (2005) reports the arrival of German, Swiss and Belgian immigrants to São Paulo between the years 1847 and 1857, almost at the same time that the Pomeranians came to the state of Espírito Santo. The first Pomeranian immigrants arrived in Espírito Santo in 1859 (Tressmann & Dadesky, 2015) and settled in the mountainous regions (Martinuzzo, 2009).

Pomeranian descendants are currently in several municipalities in the state of Espírito Santo and in other regions of Brazil such as Rondônia, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul. However, the largest proportion is found in Santa Maria de Jetibá, a city located in the mountainous central region of the State of Espírito Santo (Tressmann, 2005), with an estimated population of 39,928 (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [IBGE], 2017). The municipal economy is predominantly of horticulture and relies on family labor on small properties.

In the cultural sphere, Santa Maria de Jetibá is currently considered the most Pomeranian city in Brazil, in which a large part of this population communicates through the Pomeranian language, requiring, on certain occasions, the intermediation of an interpreter, especially the elderly population and those who live in the inner regions of the city. The same happens in schools in the city, as some children enter the school speaking only the Pomeranian language, which makes the literacy process a greater challenge.

In his research, Tressmann (2005) carried out a study on the predominance of the language among the members of the Pomeranian community of Santa Maria de Jetibá and points out that the bilingual group in Pomeranian and Portuguese is the most expressive, composed of more than 90% of the members of the community. He also identifies that Pomeranian is more spoken by women than by men; it is more present among the elderly than among young people, and the use of the Portuguese language depends on the higher level of education.

Bilingualism is defined for speakers who have linguistic competence in at least two languages, and can be acquired in different ways, ages and contexts (Almeida & Flores, 2017). In cases where the child is simultaneously exposed to two languages at the same time, it is called simultaneous bilingualism (Almeida & Flores, 2017). This is what happens with the Pomeranians: the Pomeranian language is learned in the family context. However, the Portuguese language ends up being more used, mainly by the younger ones, due to the influence of the school (Tressmann, 2005).

The Pomeranian Language started to have an official writing in Espírito Santo from the year 2000, and this recognition has been in effect since 2011, through Amendment no. 11/2009, which included, in article 182 of the State Constitution, the Pomeranian and German languages as cultural heritage of the state of Espírito Santo, being taught as a subject in the school curriculum in Santa Maria de Jetibá (Opinion no. 2/2011).

Given the historical context, some issues have been presented in a challenging way in the educational context in this city, two of the biggest challenges in relation to Pomeranian education being bilingualism and the considerable increase of students with disabilities in the last 10 years. Among the most striking difficulties in relation to the schooling of Pomeranian students, the following stand out: the high failure rate, teachers who do not speak Pomeranian, underestimation of the learning capacity of Pomeranian students, exclusion of students from school practices because they are not understood at school in their language (Küster, 2015).

The second challenging aspect for formal education in the city is the increase in the number of children with intellectual, multiple disabilities and ASD in recent years (National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira [INEP], 2017). From 2010 to 2016, there was an increase of 52.45% of cases, considering only those whose enrollments were carried out in common classrooms, with the largest increase in children with intellectual disabilities, followed by Multiple Disabilities and Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Of these, about 70% are from Pomeranian families (Centre of Inclusive Education [CREI], 2017).

Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, which appears in the early years of life and is manifested by: a) impairments in communication and social interaction, and b) restrictive and repetitive behaviors, interests and activities (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Sensory changes have also been emphasized for understanding and identifying the disorder (Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, 2006).

One of the most striking symptoms in children with ASD is the way in which social and affective relationships happen (Corrêa, 2014), to the point that one of the first observable signs in children with ASD is a significant impairment in behaviors linked to early social communication, that can be related to the social skills that emerge in the child’s first year of life: social orientation and Shared Attention skills (Ozonoff, Williams, & Landa, 2005; Corrêa, 2014; Fiore-Correia, 2005). Such a concept defines the ability to share attention with a social partner, an object and an event in a triadic relationship that emerges between 9 and 14 months and reaches stability around 18 months of life (Carpenter, Nagell, & Tomasello, 1998).

Shared Attention involves looking for the child by other people through vocalizations, gestures and eye contact, in order to share experiences, objects, among others (Campos, 2008; Corrêa, 2014; Lampreia, 2007). Thus, if there is a compromise in shared attention, the socio-affective reciprocity skills would be impaired, affecting the ability of social interaction of the person with ASD.

We will consider here as a theoretical bias to explain the aspects related to interactive communication in ASD, the developmentalist view, based mainly on research by Fiore-Correia (2005), Lampreia (2007) and Corrêa (2014), who understand that social interaction is a precursor of communicative intention, with the communication deficit in the ASD being a type of social deficit, prior to the development of language, related to the deficit of shared attention.

Corroborating the developmental approach, Stone, Ousley, Yoder, Hogan and Hepburn (1997) state that, in the first year of life, babies with atypical development learn to communicate non-verbally through eye contact, vocalizations and pre-linguistic gestures, that is, social interactions. Autistic people would present a disordered pattern of communication development with deficits in the use and understanding of non-verbal forms of communication, as well as a limited range of non-verbal communicative behaviors, that is, less frequent use of eye contact, pointing and showing objects which, consequently, would affect social responses (Lampreia, 2007).

Due to the deficit in communication, it was believed that bilingualism could be totally harmful to the development of the autistic child (Kremer-Sadlik, 2005). However, research indicates the existence of a beneficial effect in several areas, including better performance of executive functions, in particular the ability to be flexible (Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, 2018) and greater propensity to vocalize and use gestures (Petersen, Marinova-Todd, & Mirenda, 2012). Other researchers also point out beneficial effects of bilingualism in children with typical development, with better performance in cognitive tasks (Bialystock, 2001), in linguistic awareness tasks (Genesee, Paradis, & Crago, 2004) and superior reading skills (Pearson, 2009).

Kremer-Sadlik (2005) studied the relationship between doctors’ recommendations on Spanish-English bilingualism in children whose mother tongue was Spanish. Doctors and educators recommended that parents of bilingual Spanish-English children with ASD use only the English language when communicating with the child. The study noted that bilingual families who chose to use only English with their children had greater difficulty in making affective connections and affective interactions with them. The study concluded that using the dominant language (English) would be detrimental to the development of children with ASD, since the emotional connection with parents is extremely important to maintain engagement in social interaction.

Considering the context presented, the objective of this research was to describe behavior indicators of communication, based on structured interactions in Pomeranian and Portuguese, enabling the identification of differences in the interactions observed in both languages.

2 Method

The theoretical-methodological model adopted in this research was of a qualitative approach, of a descriptive character with a multiple case study design, which is characterized by the interest in individual cases (Stake, 2000). In view of the heterogeneity of the disorder, the qualitative model with multiple case study designs becomes a tool for in-depth analysis that corresponds to the objectives of this research.

2.1 Participants

Participated in this study: a) three bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese children, two with 9 years of age and one with 10 years of age, diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder of mild/moderate degree, diagnosed by a multidisciplinary team at least one year before data collection; b) the children’s mothers, one of them monolingual-Pomeranian and two bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese; c) the head teacher of the Elementary School class of the Municipal Education Network where the child studies; d) two pedagogues from the Center of Inclusive Education; e) two pedagogues from the Pomeranian School Education Program (PROEPO).

The children participating in the research were identified through contact with the Centre of Inclusive Education, the sector that monitors and guides the team of inclusive education teachers from the municipal schools of Santa Maria de Jetibá/ES. The research participants were selected jointly with the team of pedagogues from the inclusive education sector, following the inclusion criteria of this research, which were: being aged between 6 and 12 years old, being bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese, having a diagnosis of ASD performed by a multidisciplinary team at least one year before data collection, and be classified on the Autistic Spectrum by the Childhood Autism Rating Scale - CARS (Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1986).

Thus, after evaluation by the CARS scale (Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1986), the following participants were included in this research: a) Marcos, 10 years old, diagnosed with Moderate ASD, classified with a score of 36 on the CARS Scale, son of Pomeranian farmers, from the lower middle class - according to the classification proposed by Paes de Barros et al. (2012) and according to the Brazilian Association of Research Enterprises (Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa - ABEP)5 as class D (10 points) -, 4th grade Elementary School student in the municipal public school system, bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese, who had difficulty having a conversation in Portuguese, as the family usually communicated only in Pomeranian; b) Francisco, 10 years old, diagnosed with Mild ASD, classified with a score of 32 on the CARS Scale, son of Pomeranian farmers, of lower middle class - classified as class C1 (18 points) -, 4th grade Elementary School student in the municipal public school system, bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese, who tended to use mainly the Portuguese language in his conversations; c) Cadu, 9 years old, diagnosed with Mild ASD, classified with a score of 32 on the CARS Scale, son of Pomeranian farmers, of lower middle class - classified as class C2 (16 points) -, student of the 3rd year of Elementary School in the public municipal network of teaching, bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese and tended to use the two languages alternately in his conversations.

2.2 Instruments

To collect research data, we used: 1) Childhood Autism Rating Scale - CARS (Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1986); 2) Semi-structured interview with the mothers, along with the teachers and pedagogues (Hartwig, 2019); 3) Continued Storyboards (Hartwig, 2019) with the children.

2.3 Procedures

The interviews with the mothers, teachers and pedagogues were carried out individually and aimed to collect data about the child’s developmental history and to understand, mainly, the child’s communication characteristics in different contexts. To meet the objectives, a semi-structured interview was developed based on the designation of previously prepared blocks, namely: a) Sociodemographic data; b) Language development; c) Verbal and non-verbal communication. The interviews were recorded in audio and transcribed in full, the data served as a basis for further analysis of this study.

Data collection with children occurred through semi-structured interaction, using the Continued Storyboard instrument (Hartwig, 2019), which aimed to serve as a visual stimulus for children to build a narrative from the image presented. The instrument, composed of four boards, was developed by Hartwig (2019) and the application of the instrument was performed by him, who is bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese. The presentation of the boards occurred alternately so that the children could build a story in L1 and L2 with all the boards.

In order for the child to build a narrative in both languages about each board presented, it was decided to divide the application into two moments, obeying the order of application shown in Table 1.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1 Continued Storyboard - Affective relationship between family members.

Table 1 Order of application of the Continued Storyboards.

| MOMENT 1 | Board of Affective bonding between pairs | Pomeranian Language (L2) |

| Board of Relationship with the object | Portuguese Language (L2) | |

| Board of Affective bonding between family members | Pomeranian language (L1) | |

| Board of School life | Portuguese Language (L2) | |

| MOMENT 2 | Board of Affective bonding between pairs | Portuguese Language (L2) |

| Board of Relationship with the object | Pomeranian language (L1) | |

| Board of Affective bonding between family members | Portuguese Language (L2) | |

| Board of School life | Pomeranian Language (L1) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The application script followed an order of questions previously prepared. After rapport performing, the first Continued Storyboard was presented (Hartwig, 2019) and the following command was given in L1: “I would like you to observe this image you are seeing very carefully. What do you see here?” 6. After the child’s response, the researcher gave the command for the child to start the story: “I would like you to tell a story from the figure you are seeing. What are these kids doing? Tell a story about them” 7. In addition, the participants were exposed to four other questions: 1) “Who is this person?”; 2) “What is she doing?”; 3) “How is he/she feeling?”; 4) “What else do you see?”. After the conclusion of the story, the next board was presented.

The interactions were recorded in audio, had an average duration of 30 minutes and were performed by Hartwig (2019) in bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese in a previously prepared room. Observations related to communication indicator behaviors were recorded by the observer-researcher, who positioned himself in front of the child, in the Indicative Communication Behaviors Registration Chart (Table 2). The instrument presents a list of communication indicators, divided into four categories: (1) Non-verbal, (2) Verbal, (3) Comprehension and (4) Non-comprehension. For the definition of the categories, the study conducted by Lopes (2016) carried out at the University of Algarve/Portugal served as a base, which aimed to raise the communicative difficulties of children with ASD in the school and family context, and to verify in which of the contexts communicative intentionality was greater, also identifying which strategies facilitate this process. The instrument was adapted to meet the objectives of this research, and the indicator behaviors of communication were categorized as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Communication indicator behaviors.

| Non-verbal |

| Uses facial expressions, displaying emotions (primary emotion indicators). Aids communication with gestures (pointing, shrugging, shaking head as a positive or negative sign, mimics). Draws attention to himself (draws the researcher's attention to something he will say). Performs eye contact. |

| Verbal |

| Make questions. Starts the story without stimulation. Starts the story with encouragement from the mediator. Develops the story fluently. Finishes the story. Responds verbally with phrases without fluently developing the story. Responds verbally with words without forming sentences and fluently develops the story. Narrates an already experienced event. |

| Comprehension |

| Understands commands and/or verbal requests. Correctly interprets emotional states of images. Understands implicit meanings. Reacts when is not understood. |

| Non-comprehension |

| Does not emit verbal behavior after being asked to start the story (after being asked twice). Emits verbal and non-verbal responses different from the question or command received. Reacts with negative expressions like "I didn't understand", "I don't know" and "repeat". Misinterprets emotional states explicit in the figure. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In relation to the first block - Non-verbal - facial expressions, understood in this study as non-verbal communicators, were considered those behaviors that indicate primary emotions (joy, anger, sadness, fear, disgust, love), considered universal expressions. In addition to the observations made throughout the application, the child was asked how the people in the images felt, performed once for each participant, in order to understand whether the child would identify the emotional states of the images.

The behavior “drawing attention to oneself” is understood, in this research, as behaviors of addressing the other, in a non-verbal way, so that this turns the attention to the child. It was considered as a variable “to draw the researcher’s attention” without the use of verbal resources.

In this research, gesticulation is understood as a verb with intentional communication. The gestures of pointing and shaking the head in a positive or negative sign were considered in the counting. In this study, gestures are understood as a noun with the intention of expressing an idea or feeling. In this sense, the behaviors of shrugging shoulders and/or miming with intentional communication were considered. The counts were carefully made from the recordings.

In the second block - Verbal -, story is understood as the act of systematically verbalizing facts or events invented from the visual stimulus presented. To configure a story, the narrative should contain a beginning, development and conclusion. A minimum of three to five sentences, elaborated in a systematic way, without pauses, hesitations, repetition of words and/or no response. All children were exposed to the continued storyboards for an average of 30 minutes and the verbal interventions performed by the researcher occurred in the same way in all cases, taking into account only previously prepared questions.

Regarding the topic Non-comprehension: “Does not emit verbal behavior after command”, means the absence of a response from the child, after the researcher asks him/her to tell a story. Command are the phrases spoken by the researcher, as described in Table 1 previously shown.

2.4 Data analysis

The data were analyzed to identify: 1) in the interviews, the reports referring to behaviors that indicate verbal and non-verbal communication observed in family and school interactions throughout the child’s development; and 2) in interactions with children, the content of the stories reported and the type and frequency of behaviors that indicate communication.

Communication indicator behaviors, observed in the interaction with children, were recorded in the instrument Indicating Communication Behavior Registration Chart for, according to the criteria previously described. For the frequency analysis, the sums of behavior observed in the categories (1) verbal communication, (2) non-verbal communication and (3) comprehension were considered. In order to carry out the analysis of the types of behaviors, all communication behaviors observed in all categories were accounted for, in the interactions in Pomeranian Language (L1) and Portuguese Language (L2).

2.5 Ethical aspects

This research is in accordance with the guidelines and regulatory standards for studies with human beings, established in Resolution no. 466/12 of the National Health Council (2012). The approval by the Ethics Committee was obtained under Opinion no. 1.534.339. The children only started their participation after parental consent and their own consent. In order to preserve the identity of the research participants, they will be named after fictitious names.

3 Results and discussion

In this section, firstly, the communication characteristics of the Pomeranian children are addressed and, then, the interactions based on the boards of Continued Storyboard.

3.1 Communication characteristics of pomeranian children

It was found from the interviews with the mothers that all children have interacted with the Pomeranian language since babies. Marcos’ mother, who spoke only in Pomeranian language, reported that the first words he said were “daddy”, “mommy” and “grandma”, and even before developing fluent speech, he perfectly understood the commands given by his mother: “He understood pomeranian before starting to speak”. Marcos learned to speak Portuguese at school and his interaction with his mother occurred only in the Pomeranian language, presenting difficulties in communicating in Portuguese. In the cases of Cadu and Francisco, the mothers reported that their exposure to the Pomeranian and Portuguese languages occurred simultaneously; so, at school and at home, they interact in both Portuguese and Pomeranian. Literature comprises cases in which the child is simultaneously exposed to two languages as “simultaneous bilingualism” (Almeida & Flores, 2017); and, in this case, the child has two mother tongues.

Francisco’s mother also reported that, despite simultaneous exposure to languages, he was encouraged to speak in Pomeranian since birth. However, when the delay in language development was identified, the speech therapist advised that interactions in the Pomeranian language should be suspended and that the interactions should be carried out only in Portuguese for a better development of the child’s language: “When he was a baby, we talked to him in Pomeranian, but then the speech therapist at that time told us to stop talking in Pomeranian with him to see if he learned to speak faster”. Literature points out that the concept of bilingualism as a cause of pathological disorders that would affect the development of children with typical development is very common (Cruz-Ferreira, 2006). Macnamara (1966) points out, in his research, that bilingual children had inferior results of linguistic skills such as the ability of verbal intelligence, which, at the time, denoted, in general, that bilingualism would be detrimental to children’s development.

More recent studies refute this view (Bialistok & Martin, 2004; Bialystock, 2001; Bialystok & Viswanathan, 2009; Bialystok, 2009; Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008; Genesee, Paradis, & Crago, 2004; Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, 2018; Green, 2003; Kay-Raining, Genesee, & Verhoeven, 2016; Pearson, 2009; Prior & Macwhinney, 2010), showing methodological problems in the initial studies, as the researchers rarely took into account the children’s linguistic context and they often considered the performance of bilingual children in only one of the languages. In addition, they compared groups of non-homogeneous bilingual and monolingual children, with variation in many other aspects, mainly in the socioeconomic profile (Almeida & Flores, 2017).

Several studies published in recent years point to the positive effect of bilingualism on children with typical development, in various cognitive tasks (Bialystock, 2001); better performance in linguistic awareness tasks compared to monolingual children (Genesee, Paradis, & Crago, 2004); superior reading skills to children schooled in a single language in the second grade of schooling (Pearson, 2009); and, specifically, the effect of bilingualism in children with ASD, which, in a recent study, points to better performance of executive functions, especially the ability of flexibility (Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, 2018).

Francisco’s mother also reported that, due to the speech therapist’s guidance, interactions with children occurred in Portuguese, even though communication between family members occurred in Pomeranian language most of the time. She also affirmed that, today, Francisco would prefer to speak only in Portuguese: “He speaks more in Portuguese, Pomeranian only when I argue with him sometimes in Pomeranian, then he answers, sometimes he responds in Portuguese, sometimes in Pomeranian, what he can say he says. Then he thinks a little first, then he speaks. He speaks like this, mixed up, Portuguese and Pomeranian”.

The same characteristic of mixing linguistic systems was observed in the interview with Cadu’s mother: “Cadu says everything mixed up. One minute he’s speaking Portuguese, then he’s speaking Pomeranian. He speaks the two languages together, everything mixed”. The mixture or alternation of languages is known in literature as code-switching or code-mixing (Grosjean, 1982; Mello, 1999) defined as the “insertion or mixture of words, phrases or sentences of two different codes in the same speech act” (Grosjean, 1980 as quoted in Mello, 1999, p. 94). Mello (1999) describes that “code-switching” is a verbal behavior that must be considered as a linguistic performance skill, as it requires a high level of competence in two languages. Mozzillo (2005) understands that alternations are a means of negotiating changes in terms of distances and social approaches between bilingual interlocutors.

From the interviews with the teachers, it was found that the children come from classrooms whose pairs are bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese, and the interactions occur in both languages. It was also verified that, in all cases, there is difficulty in communication and social interaction at school, which, in addition to being a typical characteristic of children with ASD, also occurs with bilingual Pomeranian children in the early grades of Elementary School, due to the difficulty in the social use of the Portuguese language (Küster, 2015; Tressmann, 2005).

It was noted that Marcos had difficulties in having a conversation with other children when he entered school, as he did not know how to speak Portuguese, which can be observed in the teacher’s statement: “When he arrived at school he did not speak Portuguese, only Pomeranian, it was a teacher at the time who ran after the diagnosis, so he could do the exams and stuff ”. Cadu had communication difficulties, and, in the absence of speech, used artifices such as pointing and searching for the toys he would like to use, which can be seen in his mother’s statement: “The teacher talks about his difficulty in communicating with children and with her too, sometimes he would point, he wanted things”. Although the motor behavior of pointing is common in children with ASD, Petersen, Marinova-Todd and Mirenda (2012) found that, compared to monolinguals, bilingual children with ASD are more likely to vocalize and use gestures, although this is not a general characteristic of this population. However, in the case of Marcos, the use of non-verbal communicators as the gestures occurred because he did not have a verbal repertoire in Portuguese that favored his interaction with others, which distanced him from the social interaction with peers, enhancing the social isolation characteristic of ASD.

The behaviors of looking and pointing are also considered indicators of shared attention. According to the literature, the look is an important level for the development of other communicative behaviors, which develop in complexity. The look underlies the interactional dyad and alternating appears as a more complex variation of this behavior; then, motor actions are added (pointing, showing), forming an interactional triad and characterizing Shared Attention. In this way, even in the absence of verbal language, communicative intentionality is perceived in the research participants from the interviews with mothers, teachers and pedagogues.

In the interview with Cadu’s teacher, it was possible to verify the comprehension difficulties, which is understood by the teacher as a difficulty related to the language: “Maybe it can be something of the language like that, if, for example, it is a shorter sentence, it is easy, but if the command of an activity is a little bigger, sometimes he gets lost a little in the middle of the interpretation”. The same is observed by pedagogues in the inclusive education sector who followed his case: “Using a more elaborate vocabulary, he does not understand. If it’s more contextual, more simplified, then he can do it”. It appears that, in addition to the common communicative difficulties in ASD, Cadu also had difficulties in the social use of the Portuguese language, as well as Marcos.

Thus, it is noted that the difficulties of interaction in Portuguese can enhance the behaviors of social isolation, which was evidenced by Marcos’ teacher’s statement “He is more isolated, the greater contact he has is with his cousin that he always talks to in Pomeranian”. The same would happen in the classroom, when Marcos was unable to make simple requests in Portuguese, such as going to the bathroom: “No, he doesn’t ask. Only in case of going to the bathroom, then he says, he even says ‘banera’ [banheiro - bathroom] , he speaks very differently”. It is observed, here, that the difficulty in social communication, a common characteristic in ASD, is enhanced by his lack of mastery of the Portuguese language, which distances him from the possibilities of interaction with his non-bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese teacher.

Küster (2015) points out, in his research, carried out with the Pomeranian population, that the difficulty of the Pomeranian child with typical development to communicate at school increases his/her shyness, a characteristic common to this population, due to the difficulty of communicating correctly in Portuguese, which, in this study, is identified as a risk factor that potentiates social isolation behaviors in children with ASD. Now, the difficulty of interacting in Portuguese, associated with the ASD framework whose central axis is the difficulty in social communication, makes social interactions less frequent at school, making monolingual education a risk for the development of the Pomeranian child with ASD.

It was found, in the teachers’ statements, a repeated mention of the characteristics of Marcos and Cadu’s shyness, which literature also points out in relation to the Pomeranian population (Küster, 2015): “He has attitudes that even his peers have, right? Shyness, you know, fear remains”, reported Cadu’s teacher. The same is reported by pedagogues in the inclusive education sector: “He is shyer, he takes a while to open up” and “he is more close-mouthed, demure, he keeps his head down”. In another moment, the pedagogues reported shyness as one of Marcos’s characteristics: “He stays more isolated, he won’t open up so much, he is distrustful. He makes no eye contact, he blushes and lowers his head. He’s very shy”. Here, repeated mention is made of characteristics of shyness, frequent in the Pomeranian population; however, it must be considered that social isolation and little eye contact are common diagnostic characteristics in ASD, and their association with shyness behaviors may represent little knowledge by professionals regarding the characteristics of children with ASD, which may represent a risk factor for his/her development.

In Marcos’s case, the teacher reported that he interacts more when the conversation takes place in the Pomeranian language: “I feel that he feels more comfortable when it is in Pomeranian, you know, you feel that he understands. I, for example, explain it to him in Portuguese and Pomeranian”. Schweers (1999) believes that the student’s mother tongue is the main means of communication and cultural expression and that its use in the classroom has shown positive indicators regarding the learning process. Thus, in this study, it is considered that the bilingual educational context in the schools of the Pomeranian community is an important means for favoring social interactions in children with ASD, since most of the schools in the city are attended by the bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese population. In addition, a bilingual school environment enables cultural expression and the strengthening of the language of this population.

At the end of the interview, the teacher reported the affective relationship that Marcos would have with the Pomeranian language: “And in Pomeranian you see his excitement, he likes to talk about fish, you will observe, he talks about fishing, fish, his ox, the reality that lives around him”. Mozzillo (2005) refers to the emotional factor as one of the motivators to use the mother tongue, understanding that there are people who can only demonstrate their true feelings using the mother tongue. This was also observed in the interactions carried out with children, described below, when emotional expressions occurred more frequently in interactions carried out in the Pomeranian language, when compared to those carried out in Portuguese.

3.2 Interactions from the continued storyboards

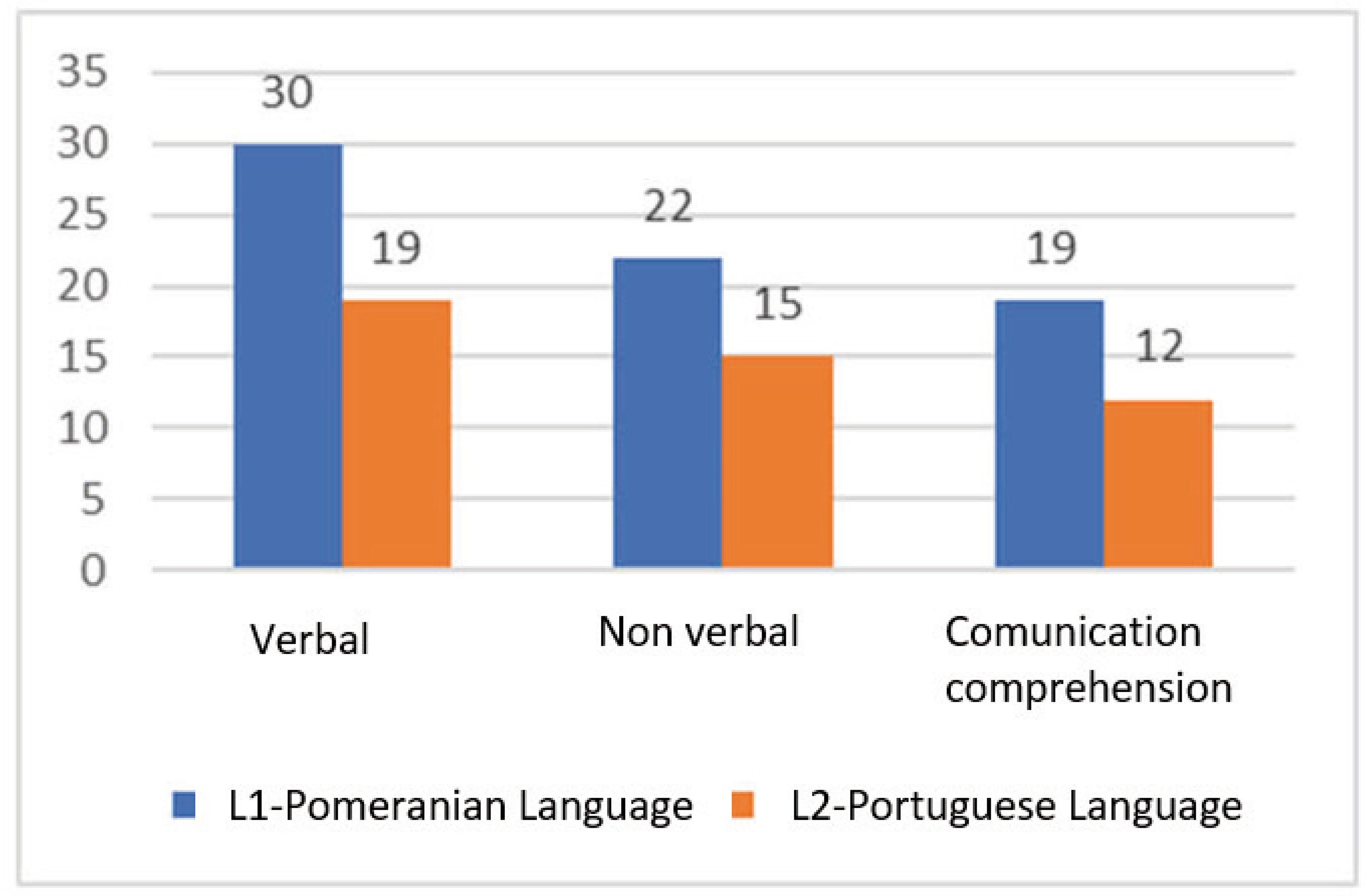

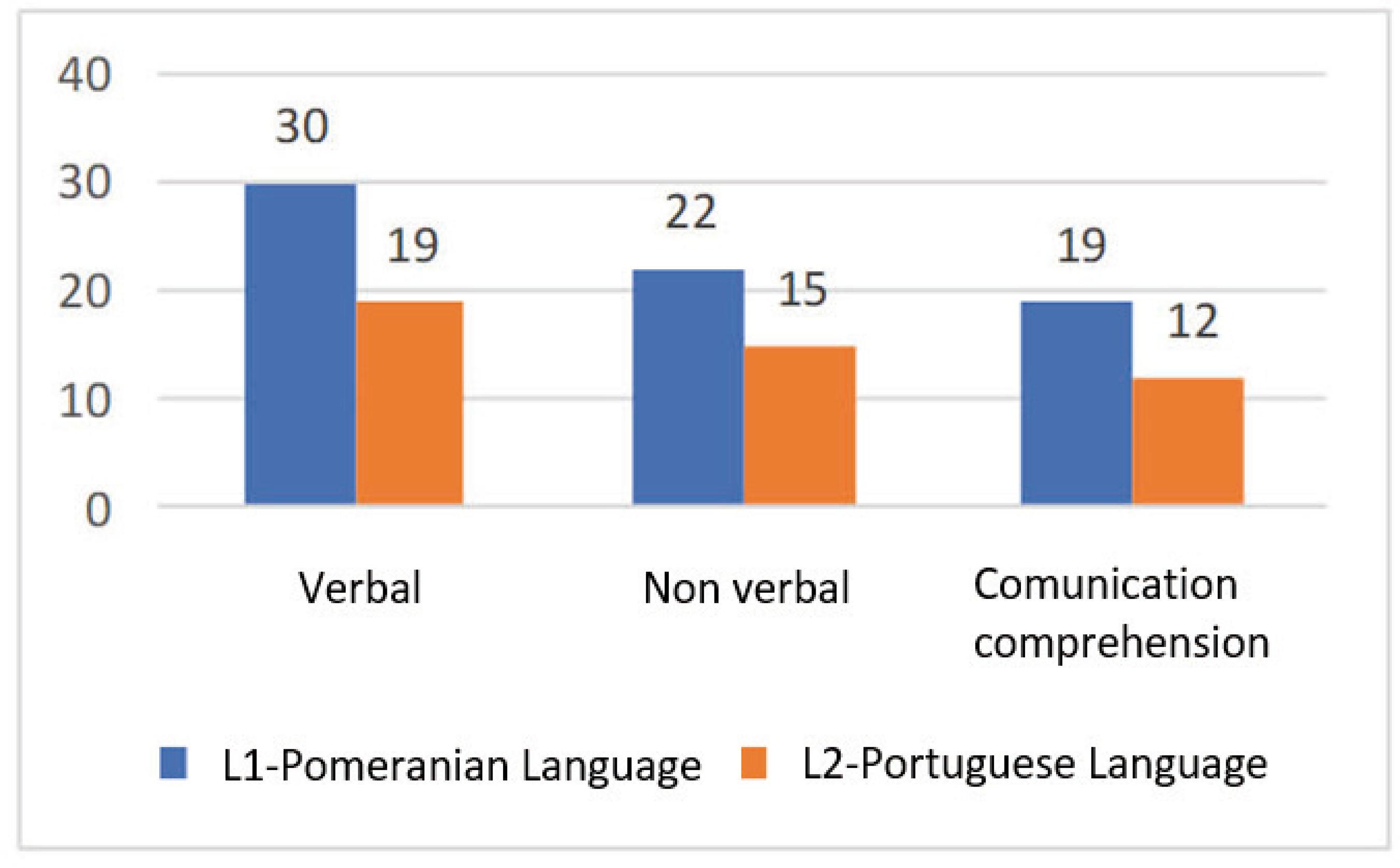

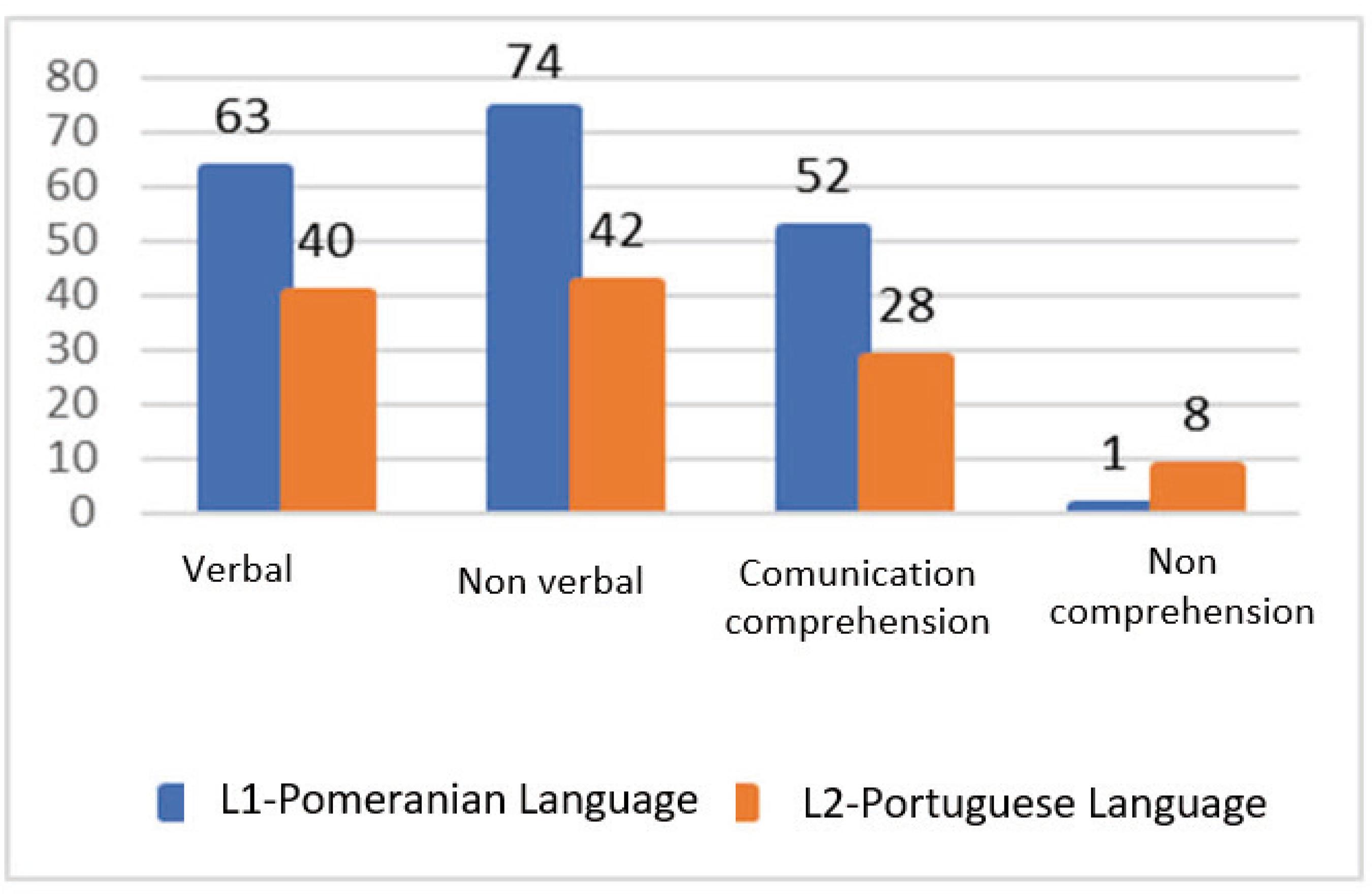

In the interactions carried out with the Continued Storyboard, it was observed that the communication behaviors were more frequent, in all cases, in the interactions performed in Pomeranian Language (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Cadu alternated the linguistic system according to mediation, although he tended to tell his stories in Portuguese, mixing words, phrases and expressions from the Pomeranian language. He also tended to contextualize the boards with his reality, for example, when he mentions his animals, in Portuguese, on the Affective relationship board among family members: “The child has a dog, I have too, they call themselves Feroz [ferocious] and Girafa [giraffe]”. Cadu showed the ability to start, develop and build his stories without the help of the mediator; with just one command given, whether in Pomeranian or Portuguese, he started the narrative.

The easy switching between the two language systems denotes the ability to be flexible, in addition to being an indicator of communicative intentionality with the interlocutor (Mello, 1999). It was observed that Cadu’s verbal repertoire was more varied in the Portuguese language, which is possibly related to his literacy process and the social relationships experienced at school (Tressmann, 2005).

Francisco and Marcos were not able to develop a story fluently; however, they communicated in a non-systematic way. Francisco took the initiative to communicate only in Portuguese, emitting words and phrases that did not constitute a story. The words were related to what he visualized on the boards, and his tendency was to correlate them with his personal experiences. The fact that he only interacts in Portuguese may have occurred because he identified the researcher as a teacher. The same was observed in Marcos; however, he communicated only in the Pomeranian language, even when the linguistic system was changed by the researcher. In addition to his narratives being based on the characteristics of the visualized image, his communication occurred only in the Pomeranian language.

Although Francisco and Marcos did not build a story in a fluent way, both were able to report what they observed in the visualized images and showed more behaviors indicating non-verbal communication in the mediations performed in Pomeranian language, mainly on the Affective relationship board among family members, in which it was identified the greatest indicator of non-verbal behaviors of both. They smiled, made eye contact and showed that they were motivated to say what they saw on the board. In addition, in all participants, expressions of joy, eye contact and attention sharing were more frequent in interactions conducted in the Pomeranian language, compared to those performed in Portuguese, which demonstrates greater satisfaction in the use of the mother tongue.

It was also found that the highest frequency of non-comprehension indicator behaviors occurred when the interaction was performed in Portuguese, indicating that, for these participants, understanding is more effective when communication is performed in the Pomeranian language.

4 Final considerations

This research sought to describe behaviors that indicate communication, based on the analysis of the behaviors presented by Pomeranian children with ASD, whose language development occurred in a bilingual Pomeranian-Portuguese context. We sought to understand whether there are differences in communication based on interactions carried out in Portuguese and Pomeranian, since social communication is a universal diagnostic criterion for people with ASD.

The first finding is that, throughout the interactions with the children in this research, one of them often tended to alternate the linguistic systems used to communicate, which indicates the ability of cognitive flexibility, competence of executive functions, a finding that corroborates the recent research conducted by Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig (2018), who predicted the positive impact of bilingualism on executive functions. Since bilingualism acts on the executive function of flexibility, it can be suggested that it can act in a positive way on difficulties related to task changes. In addition, the alternation between the linguistic systems makes it possible to expand the child’s interaction possibilities (e.g. grandparents who speak Pomeranian, classmates who are bilingual), which expands their interactional repertoire.

Another important finding points out that the participants presented more indicators of verbal and non-verbal behaviors in the interactions performed in the Pomeranian Language (L1), when compared to the behaviors presented in Portuguese (L2). The data indicate that, in addition to communicating more, children tended to share attention with the mediator more frequently in interactions carried out in their mother tongue, that is, in interactions carried out in the Pomeranian language. Smiles, gestures, sharing attention from the use of the object and affective demonstrations - actions that set the stage for the development of other more complex communicative behaviors and act as predictors of linguistic development - were more evident and frequent when compared to interactions in Portuguese. It is evident, therefore, that interactions in the mother tongue (Pomeranian) can act to strengthen the child’s emotional connections with the others, which facilitates the development of Shared Attention skills, a central competence for strengthening social interactions.

Thus, we recognize here the importance of the child’s parental and social relationships taking place in the mother tongue throughout early childhood, since its use seems to strengthen affective connections, essential aspects for the child to maintain engagement in social interaction, as it was observed, throughout the research, that the social interactions that take place in the homes of these children are in Pomeranian language and that, even, one of the participating mothers did not speak Portuguese. In addition, we point out that bilingual education in schools is an important factor for strengthening affective connections with peers, considering that the participants in this research come from bilingual classrooms and speak more in Pomeranian than in Portuguese, both at school and away from it. In the Pomeranian community, it is precisely the mastery of the Pomeranian language that makes it possible for the child to be integrated amongst his/her peers. It is also considered that the child’s mother tongue is the main means of communication and cultural expression, and its use in the classroom has shown positive indicators regarding the learning process, as indicated by literature on the subject (Schweers, 1999).

Furthermore, we are facing a population from a traditional community in which language is an important cultural artifact and, at the same time, a tool that guarantees access to cultural elements. In this way, the use of the mother tongue among Pomeranian children provides opportunities for them to become active members in the cultural communities in which they belong, strengthening the feeling of belonging, in addition to contributing to the child’s ethnic and identity formation, which increases the possibilities of social interactions inside and outside of the home, strengthening once again the affective connections and bringing them closer to their bilingual peers.

It was verified that in all cases of this research the children had the mediation of a bilingual teacher during the first years of Elementary School, which, according to the teachers’ report, seems to have contributed to the adaptation regarding linguistic differences, an aspect that configures great difficulty in the beginning of the child’s school life and that can be enhanced by hegemonic linguistic environments that do not consider the child’s specific communicative needs. The interaction in their mother tongue seems to provide children with a more comfortable feeling in the classroom through more effective communication with the teacher and to be able to express their needs and emotions in their mother tongue, and, concomitantly, strengthen the affective connection with the teacher, a necessary aspect to maintain engagement in the interaction, which literature has pointed out as an important element for the learning process.

Another aspect to be highlighted in this research is the clinical diagnosis of the Pomeranian child with ASD, which occurs mainly through behavioral observation. One of the universal diagnostic criteria for ASD is the impairment of non-verbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction (DSM 5); however, the expectations and manifestations of these communicative and expressive skills can vary from one culture to another, although the diagnostic criteria do not vary. For example, in the Pomeranian population, there is some difficulty in expressing their affections, which makes this population less expansive and socially shyer. By associating these characteristics to the difficulty of social use of the Portuguese language, there is a risk of generating inconsistencies in the clinical diagnosis of Pomeranian children, with the possibility of underdiagnosing ASD in children of this population. The opposite can also occur, as observed in this research, when the deficits common to the Autistic Spectrum are understood as characteristics of shyness. Thus, it is considered extremely important that children from this population are evaluated by multidisciplinary teams, with at least one of the Pomeranian-Portuguese bilingual professionals, so that the child is exposed to interactions in both languages.

Finally, we hope that these findings may further contribute to the development of bilingual children with ASD from other traditional cultures and/or bilingual populations and that prospective studies may expand the discussion related to the effect of the mother tongue on the development of children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder.

5Brazil Economic Classification Criterion. Retrieved on May 28, 2019 from http://www.abep.org/novo/Content.aspx?SectionID=84

7In L1: “Ik wul gern dat duu ain geschicht fortelst oiwer dat buld wat duu hur süüst. Wat make der kiner hür? Fortel ain geschicht oiwer eer”.

REFERENCES

Almeida, L., & Flores, C. (2017). Bilinguismo. In M. J. Freitas, & A. L. Santos (Eds.), Aquisição de língua materna e não materna: Questões gerais e dados do português (pp. 275-304). Berlin: Language Science Press. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, FifthEdition (DSM-V). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [ Links ]

Baranek, G. T., David, F. J., Poe, M. D., Stone, W. L., & Watson, L. R. (2006). Sensory experiences questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in Young children with autism, developmental delays and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(6), 591-601. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x [ Links ]

Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bialystok, E. (2009). Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12(1), 2009, 3-11. DOI: 10.1017/S1366728908003477 [ Links ]

Bialystok, E., & Martin, M. M. (2004). Attention and inhibition in bilingual children: Evidence from the dimensional change card sort task. Developmental Science,7(3), 325-339. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00351.x [ Links ]

Bialystok, E., & Viswanathan, M. (2009). Components of executive control with advantages for bilingual children in twocultures. Cognition, 112(3), 494-500. DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.06.014 [ Links ]

Campos, A. P. S. (2008). Atenção psicológica clínica: encontros terapêuticos com crianças em uma creche (Dissertação de Mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas - PUC Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2008). Bilingual Experience and Executive Functioning in Young Children. Developmental Science, 11, 282-298. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x [ Links ]

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K., & Tomasello, M. (1998). Social cognition, joint attention and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development,63(4), 1-143. [ Links ]

Centro de Educação Inclusiva. (2017). Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Santa Maria de Jetibá. Santa Maria de Jetibá, Espírito Santo. [ Links ]

Corrêa, M. C. C. B. (2014). Atenção Compartilhada e Interação Social: Análises de Trocas Sociais de Crianças com Diagnóstico de Transtorno do Espectro Autista em um Programa de Intervenção Precoce (Tese de Doutorado em Psicologia). Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo - UFES, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Cotrim, G. (2005). História Global. São Paulo: Saraiva. [ Links ]

Cruz-Ferreira, M. (2006). Threeis a Crowd? Acquiring Portuguese in a Trilingual Environment. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters LTD. [ Links ]

Fiore-Correia, O. B. (2005). A aplicabilidade de um programa de intervenção precoce em crianças com possível risco autístico (Dissertação de Mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro - PUC RIO, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [ Links ]

Genesee, F., Paradis, J., & Crago, M. B. (2004). Dual language development and disorder: a handbook on bilingualism and second language learning. Baltimore, MD: Paul Brookes. [ Links ]

Gonzalez-Barrero, A. M., & Nadig, A. (2018). Bilingual children with autism spectrum disorders: The impact of amount of language exposure on vocabulary and morphological skills at school age. Autism Research, 11(12), 1667-1678. DOI: 10.1002/aur.2023 [ Links ]

Green, D. W. (2003). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: language and cognition,1(2), 67-81. [ Links ]

Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with Two Languages: Na Introduction to Bilingualism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Hartwig, M. D. (2019). Pomerisch Oder Portugiesisch Sprache? Interação Comunicativa Em Crianças Pomeranas Bilingues Com Transtorno Do Espectro Autista (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. IBGE. (2018). Censo Demográfico 2017. Brasília: IBGE. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. INEP. (2017). Censo da Educação Básica. Brasília: INEP. [ Links ]

Kay-Raining, B. E., Genesee, F., & Verhoeven, L. (2016). Bilingualism in children with developmental disorders: a narrative review. Journal of Communication Disorder, 63, 1-14. [ Links ]

Kremer-Sadlik, T. (2005). To be or not to be bilingual: Autistic children from multilingual families. In J. Cohen, K. T. McAlister, K. Rolstad, & J. MacSwan (Eds.). Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism (pp. 1225-1234). SomerVille, MA: Cascadilla Press. [ Links ]

Küster, S. B. (2015). Cultura e língua pomeranas: um estudo de caso em uma escola do ensino fundamental no município de Santa Maria de Jetibá - Espírito Santo - Brasil (Dissertação de Mestrado) Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo - UFES, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Lampreia, C. (2007). A perspectiva desenvolvimentista para a intervenção precoce no autismo. Estudos de psicologia, 24(1), 105-114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2007000100012 [ Links ]

Lopes, S. A. de J. B. (2016). A Comunicação em contexto escolar e familiar da criança autista: estudo de caso (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade do Algarve, Escola Superior de Educação e Comunicação, Faro, Portugal. [ Links ]

Macnamara, J. (1966). Bilingualism and primary education: a study of Irish experience. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Martinuzzo, J. A. (2009). Palácio Anchieta: Patrimônio capixaba. Vitória: Governo do Estado do Espírito Santo. [ Links ]

Mello, H. A. B. de. (1999). O Falar Bilíngüe. Goiânia: Ed. da UFG. [ Links ]

Mozzillo, I. (2005). La interlengua: producto Del contacto lingüístico em clase de lengua extranjera. Caderno de Letras (UFPEL), 11(11), 65-75. [ Links ]

Ozonoff, S., Williams, B. J., & Landa R. (2005). Parental report of the early development of children with regressive autism: The delays-plus-regression phenotype. Autism, 9(5), 461-486. [ Links ]

Paes de Barros, R., Portela, A., Junior, A. B. L., Caillaux, E., Veras, F., Quiroga, J..., Braga, R. W. (2012). Relatório de definição da classe média. Recuperado em 3 de setembro de 2018 de http://www.sae.gov.br/vozesdaclassemedia/wp-content/uploads/Relat%C3%B3rioDefini%C3%A7%C3%A3o-da-Classe-M%C3%A9dia-no-Brasil.pdf [ Links ]

Parecer nº 2/2011. Inclui inciso VI, ao artigo 182 da Constituição Estadual, que trata do Patrimônio Cultural do Estado. Recuperado em 20 de fevereiro de 2020 de https://claudiovereza.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/pec-11-de-2009_1.pdf [ Links ]

Pearson, B. (2009). Children with two languages. In E. L. Bavin (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language (pp. 380-382). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Petersen, J. M., Marinova-Todd, S. H., & Mirenda, P. (2012). Brief report: an exploratory study of lexical skills in bilingual children with Autism Spectrum. Journal of Autism and developmental disordes, 42(7), 1499-1503. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-011-1366-y [ Links ]

Prior, A., & MacWhinney, B. (2010). A bilingual advantage in task switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13, 253-262. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728909990526 [ Links ]

Resolução nº 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Retrieved on September 3, 2017 from https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html [ Links ]

Röelke, H. (1996). Descobrindo raízes: aspectos geográficos, históricos e culturais da Pomerânia. Vitória: UFES. [ Links ]

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1986). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) for diagnostic screening and classification in autism. New York: Irvington. [ Links ]

Schweers, W. Jr. (1999). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. English Teaching Forum, 37(2), 6-9. [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (2000). Case studies. In: N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 435-454). Londres: Sage. [ Links ]

Stone, W. L., Ousley, O. Y, Yoder, P. J., Hogan, K. L., & Hepburn, S. L. (1997). Nonverbal communication in two- and three-year-old children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 27(6), 677-696. [ Links ]

Tressmann, I. (2005). Da sala de estar à sala de baile: estudo etnolingüístico de comunidades camponesas pomeranas do Estado do Espírito Santo (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [ Links ]

Tressmann, I., & Dadesky, J. O pomerano-brasileiro: quem é ele? A língua pomerana na identidade de Santa Maria de Jetibá. 2015 (Tese de Doutorado em Sociologia). Universidade Candido Mendes, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [ Links ]

Turbino, N. (2007). A germanidade no Brasil. Porto Alegre: Sociedade Germânia. [ Links ]

Received: June 26, 2019; Revised: December 06, 2019; Accepted: January 02, 2020

texto en

texto en