Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

versión impresa ISSN 1413-6538versión On-line ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.2 Marília abr./jun 2020 Epub 11-Mayo-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382620000100009

Research Report

Multifunctional Resource Room Teacher Training and Enactment With the Diversity of the Target Population of Special Education1, 2

3PhD with habilitation in Special Education, Department of Special Education, Faculty of Philosophy and Sciences - UniversidadeEstadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho (Unesp) - Marília campus. Marília/São Paulo/Brazil. E-mail: anna.augusta@unesp.br. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8675-967X

4PhD in Education, Department of School Administration and Economics of Education, Faculty of Education - University of São Paulo (USP). São Paulo/Brazil. E-mail: rosangel@usp.br. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4013-1163

The changes implemented in Brazil related to inclusive education and Specialized Educational Service (SES) have substantial effects on teacher performance in Multifunctional Resource Rooms (SRM), as it is now necessary to work with all categories of the target population of Special Education. Thus, this research aimed to analyze the training and enactment of teachers of the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo. As a data collection procedure, an electronic questionnaire was used through Google Docs, sent to 400 teachers of these classrooms, from which we obtained a return of 179 (45%). After the collection, data were analyzed through Atlas.ti 8.4-14 Software for Windows. The results indicated that 150 teachers (84%) did not feel able to work with all categories of the target population of Special Education and 29 (16%) said they did. In addition, teachers were invited to comment on their responses and of the 179 respondents, 81 (45%) provided justifications related to their work experience in their training areas, 61 (34%) mentioned the need for professional improvement, 28 (16%) commented that they have training in only one or a few of the categories they worked with, 5 (3%) referred to their work experience and 4 (2%) referred to intersectority. The analysis of the data allows us to affirm that there is a significant distance between training and enactment with all the diversity of the target population of Special Education, bringing substantial difficulties to the pedagogical practice.

KEYWORDS: Special Education; Inclusive education; Teacher training

As mudanças implementadas no Brasil, relacionadas à Educação Inclusiva e ao Atendimento Educacional Especializado (AEE), têm efeitos substanciais na atuação das(os) professora(es) em Sala de Recursos Multifuncionais (SRM), uma vez que passa a ser exigido o trabalho com todas as categorias do público-alvo da Educação Especial. Assim, esta pesquisa teve como objetivo analisar a formação e a atuação das(os) professoras(es) das SRM da Rede Municipal de Ensino de São Paulo. Como procedimento de coleta de dados, foi usado um questionário eletrônico por meio do Google Docs, o qual foi enviado para 400 professoras(es) dessas salas, dos quais foi obtida a devolutiva de 179 (45%). Após a coleta, os dados foram analisados por meio do Software Atlas.ti 8.4-14 for Windows. Os resultados indicaram que 150 professoras(es) (84%) não se sentem capacitadas(os) para atuação com todas as categorias do público-alvo da Educação Especial e 29 (16%) afirmaram que sim. Como complementação, foi solicitado às(aos) professoras(es) que comentassem suas respostas. Das(os) 179 respondentes, 81 (45%) apresentaram justificativas relacionadas à sua experiência de trabalho nas áreas de sua formação; 61 (34%) referiu-se à necessidade de aperfeiçoamento profissional; 28 (16%) comentaram que possuem formação apenas em uma ou poucas das categorias que atuavam; 5 (3%) remeteram à sua experiência de trabalho; e 4 (2%), à intersetoriedade. A análise dos dados permite afirmar que há distanciamento significativo entre a formação e a atuação com toda a diversidade do público-alvo da Educação Especial, de modo a interpor dificuldades substanciais à prática pedagógica.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Educação Especial; Educação Inclusiva; Formação de professoras(es)

1 Introduction

The right of all to school education and Specialized Educational Service (SES) - prescribed in the Federal Constitution of 1988, and, subsequently, the changes implemented in Brazil with the National Education Guidelines and Framework Law (Law no. 9,394, of December 20, 1996), in addition to the documents promulgated in the 2000s, such as the publication of the National Guidelines for Special Education in Basic Education, through Resolution no. 2, of September 11, 2001, the National Policy for Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education (PNEEPEI) of 2008, the Operational Guidelines for Specialized Educational Service (Resolution no. 4, of October 2, 2009), among others -, have implications for the organization of specialized pedagogical support services, understood as SES. These are almost exclusively offered in multifunctional resource rooms (MRR), in a simplistic understanding of the different needs of the Target Population of Special Education (TPSE) and pointed out by Mendes and Malheiros (2012) as a “one size service”, that is, a single specialized support model.

The organization of specialized support services, preferably in the form of MRR, brought with it the interpretation that its conductor must be a multicategorial teacher - that one who must act with all categories expressed in the concept of TPSE. Resolution no. 4/2009, which established the operational guidelines for the SES, in its article 13, when defining the attributions of the professor of the SES, in its item I, which points out that it is his talk to “identify, elaborate, produce and organize services, pedagogical resources, accessibility and strategies considering the specific needs of target students of Special Education” (p. 3), reaffirming an interpretation of the performance with all the diversity of the TPSE.

The 2010 Manual de Orientação: Programa de Implantação de Salas de Recursos Multifuncionais (Guidance Manual: Program for the Implementation of Multifunctional Resource Rooms), which aimed to provide equipment, furniture and teaching materials, among other guidelines, points to the possibility of constituting two types of MRR - I and II -, being MRR II made up of its own resources for blind or low vision students. This could lead to an interpretation of the need to differentiate the attendance to certain conditions of these students, which, in a way, characterizes the room to be multifunctional, that is, to have diverse resources and more specific training to work, for example, in visual impairment. However, in practice, the specialized teacher will be assigned to act with all the diversity of the different categories that make up the TPSE: those with disabilities, global developmental disorders and high skills/giftedness and, in addition, obviously, the internal diversity of each category.

This seems to be the keynote of the training and performance of the SES teacher, perhaps due to a relationship between MRR and multicategorial performance or the interpretation of the provisions in the guidelines that refer to the idea of planning with a focus on the needs of the TPSE. On the one hand, although it is not explicit, it seems to us that the legislation ends up leading to this more general view of the function to be performed by this professional. On the other hand, the course proposals made by the Ministry of Education and the guidelines of the advisory team that collaborated in the design of the ESA clarify that:

The first structuring that occurs in this training starts from the understanding that the teacher of the SES is not an expert in a given disability. His/Her objective is to get to know the student, identify his/her possibilities and needs, outline an SES plan so that he/she can organize the services, strategies and accessibility resources. (Machado, 2011, p. 5).

Thus, we can conclude that there was an institutional and official conduct of the Ministry of Education for training and acting with all the diversity of the TPSE, despite the fact that we do not have legal provisions that prevent municipalities from adopting another type of organization. However, in addition to specific regulations for Inclusive Education and Special Education, the publication of the National Guidelines for Undergraduate Courses in Pedagogy (Resolution no. 1, of May 15, 2006), among other measures, establishes the extinction of qualifications and, as a consequence, it extinguishes the training in Special Education that had been occurring in most Brazil since the 1970s (Oliveira & Mendes, 2017). This has significant implications for thinking about how to train teachers to work in the SES, in the MRR model, contributing to the consolidation of the idea of training and multicategorial performance, driven, including by the proposals of SES training courses, promoted by the Secretariat for Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion.

Despite official proposals for teacher training courses for SES, the constitution of a training policy for specialized teachers was not observed. Oliveira (2009) already questioned this lack of guidelines and the need for national regulation to establish the guiding criteria for training in Special Education and a system of evaluation and monitoring with regard to the structure, organization and pedagogical proposal of course proposals that could guarantee the specificity of consistent training based on the new indications prescribed in national education regulations.

However, today, we still observe the absence of national guidelines for the training of this teacher in this new educational scenario - of inclusive education and SES - to act with the needs of the TPSE and offer them specific educational responses, such as: assistive technology, organization and systematization of structured teaching procedures to support learning, diversified strategies to guide reciprocal social interaction in the area of Autistic Spectrum Disorder, the cross-functional development of psychic functions and curriculum enrichment, among others (Barroco, 2012; Bersch, 2017; Galvão Filho, 2009; Hogan & Hogan, 2007; Renzulli, 2014; Special Education: Practice Support Manual [Educação Especial: Manual de apoio à prática], 2008).

Several authors (Hora & Miranda, 2017; Oliveira & Mendes, 2017; Oliveira, 2019; Otalara & Dall’acqua, 2016; Pagnez, Prieto, & Sofiato, 2015; Silva, Miranda, & Borda, 2017) have been dedicated to the study on the training of specialized teachers, since their performance in MRR changes substantially and has new characteristics, from the extension of their duties with all categories of TPSE, the organization of strategies, guidance and monitoring for use accessibility resources in the common class and/or at school, articulation with other teachers, with the school, the family, among others. Mendes (2009) points out that teachers have doubts about how to organize differentiated teaching, some of them demonstrate “uncertainty about what would be correct: equalize or differentiate [leading to the perception of] that there was little understanding of the concept of equalizing teaching conditions” (p. 29).

Training designs in Special Education or to work at SES (Jesus & Borges, 2018) do not seem to be able to consolidate specific knowledge that will guide the action of the teacher who works at MRR with the diversity of characteristics of the TPSE students. This was a point of our investigation, whose objective was to analyze the training and performance of teachers in these rooms of the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo. The research question that guided our investigation was: Which arguments are used by the teachers who evaluate having training to work with all TPSE categories and which justifications are used to affirm the opposite? Our focus was on MRR, since the city of São Paulo has other SES proposals.

2 The organization of the SES in the city of São Paulo

The Municipal Secretariat of Education, due to its dimension and for the better operationalization of its actions, is organized through 13 Regional Education Directorates (called DRE - Diretorias Regionais de Educação), each of which has a Center for Education and Support for Inclusion (called CEFAI - Centro de Formação e Apoio à Inclusão), which is responsible, among other duties, for the training of SES teachers (Ordinance no. 8,764, of December 23, 2016). CEFAI is made up of a coordinator and of Accompanying and Supporting Inclusion Teachers (called PAAI - Professores de Acompanhamento e Apoio à Inclusão) from different areas of disabilities5, who also play an itinerant role and have the responsibility of acting jointly with teachers of the common class and other school professionals to collaborate in the organization of practices related to meeting the special educational needs of TPSE.

The São Paulo Special Education Policy, in the Perspective of Inclusive Education, established by Decree no. 57,379, of October 13, 2016, and by Ordinance no. 8,764, of December 23, 2016, defines the target population to be served, aspects related to enrollment and schooling; clarifies the structure and organization of Special Education services, as well as those responsible for their implementation and monitoring, maintaining a CEFAI in each regional; and establishes the itinerant performance carried out by PAAIS and MRR conducted by teachers with training in Special Education, responsible for organizing and offering SES in educational units.

Decree no. 57,379/2016 defines, in article 5, the SES as “the set of educational and accessibility activities and resources institutionally organized, provided in a complementary or supplementary manner to school activities, intended for the target population of Special Education that needs it”; defines its function as provided for in the National Policy; establishes the articulation of the school’s educators with the teachers of the SES; and points out that “the SES offer will take place in different educational times and spaces, in the following forms: I - in the evening; II - through itinerant work; III - through collaborative work ”.

In article 9 of Ordinance no. 8,764/2016, there is a clarification that the SES in the school day will be held in MRR, not substituting the registration and frequency of the TPSE in common classes. The document therefore establishes its complementary or supplementary character, as defined in the National Policy for Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education (2008). This service in MRR can be extended to students enrolled in schools in the region and the performance will be exercised by the teacher of the SES.

Although this form of organization was foreseen by the documents (Decree no. 57,379/2016 and Ordinance no. 8,764/2016), there is no clarification or clear definition of differentiating criteria and functioning of each one, which could allow a better orientation to the regionals on its feasibility, the following description being found in the Ordinance:

collaborative: developed within the shift, articulated with professionals from all areas of knowledge, at all times and educational spaces, ensuring compliance with the specificities of each student, expressed in the SES Plan, through systematic monitoring of the target population of special education.

extra hour classes: meeting the specific needs of each student, expressed in the SES Plan, in the extra school hours, carried out by the TPSE, in the School Unit itself, in the surrounding School Unit or in a Specialized Educational Service Center in an accredited Special Education Institution with the Municipal Secretariat of Education.

Itinerant: within the shift, in an articulated and collaborative way with teachers of the class, the Management Team, PAAI and other professionals, ensuring compliance with the specificities of each student, expressed in the SES Plan. (Ordinance no. 8,764/2016).

It is possible to observe an attempt to differentiate and point out specific aspects in the organization of the types of SES, however, as described, it does not allow us to have clarity on how to execute, in an equivalent way in the different regions of São Paulo, the proposition prescribed in terms of the outline of municipal policy, particularly in relation to collaborative and itinerant SES, as extra hour classes are the mark of the practice of specialized teachers linked to MRR. However, the own activities of the SES are defined in article 22, in full compliance with the National Policy for Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education (2008), such as the teaching of Braille, Soroban6, orientation and mobility; development of autonomy, independence and mental processes; teaching Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) and Portuguese as a second language; alternative and augmentative communication; accessible computing and assistive technology; and curriculum enrichment.

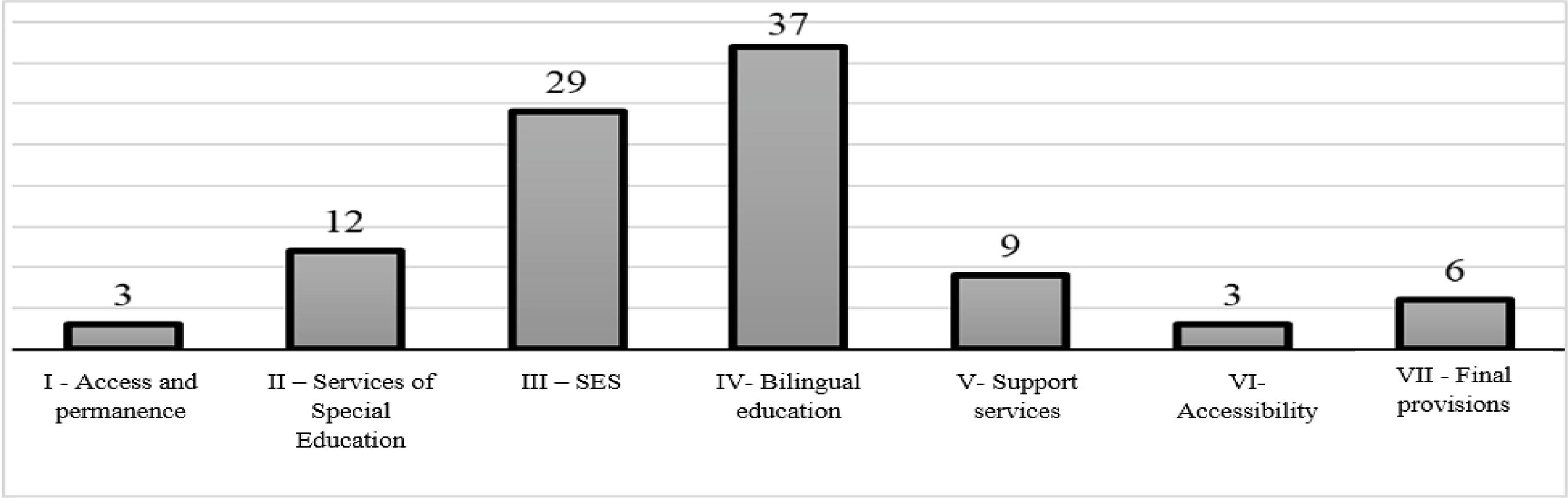

Ordinance no. 8,764/2016 is quite extensive, with 100 articles, distributed in different subjects that, combined, make up the municipality’s policy guidelines, which are distributed as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1 Distribution of articles in Ordinance no. 8,764/2016 in percentages.Legend: SES: Specialized Educational Service.

In the visualization of the graph, the set of devices referring to the education of the deaf stands out, conferring greater consolidation in the organization of this area, through bilingual schools, bilingual classes in school centers and in common classes, with access to SES in its three forms of organization. In these three different services, bilingual guidance requires investments in teacher training policies to ensure that the deaf are able to acquire Brazilian Sign Language and Portuguese language in written form as first and second languages, respectively.

In the item on SES, with 29% of the 100 articles of the Ordinance, various aspects are concentrated, from information on organization, assessment, referral, types of SES, training and assignment of teachers to act in the different possibilities of SES provision. In the other items, with 12% and 9%, the articles are related to special education and support services, respectively, which contain guidelines and specifications on the referred services.

We can affirm, based on Oliveira and Drago (2012), that “the trajectory in special education, in the municipal education system of São Paulo, has acted in the search for a significant growth in political-administrative actions” (p. 352), and that there are advances in the promulgation of laws, which may encourage the constitution of inclusive processes and more appropriate responses to the needs of the TPSE, despite the difficulty of executing the services under the terms recommended by law. In this sense, it is justified a study that seeks to explore the feasibility of Special Education actions, in this case, the extra hour class SES (MRR), having as reference the narrative of the specialized teacher who works in this space.

3 Methodological procedures

Four hundred teachers from SES were invited to participate in the study, working in the MRR of the 13 Regional Education Directorates of the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo, which corresponded to 95% of the total of 421 teachers, since 21 of them were excluded, whose e-mail addresses were not found and, despite our insistence, they were not corrected or updated so that we could contact them to invite them to participate in the research. This survey was carried out through contact with the coordinators of CEFAI (Center for Education and Support for Inclusion), after the São Paulo Municipal Secretariat of Education authorization for the research. Thus, 400 invitations to participate in the survey were sent out and 179 (45%) teachers responded, considering all the regional boards.

For data collection, an electronic questionnaire was applied, elaborated with the Google Docs tool, together with the MRR teachers. The questionnaire was sent by electronic message containing the e-mails of the teachers grouped by region and the follow-up of the responses was carried out constantly, for a period of three months, which allowed the gradual expansion of the participation of the teachers.

The questionnaire generated multiple choice and descriptive responses. The multiple choice ones were exported to Excel and allowed the generation of graphics by the Google program itself, and the descriptive ones were exported to the Atlas.ti software. We then performed the organization of the data with the tools available in the software itself, which allowed us to compose analytical categories, according to Table 1.

Table 1 Analysis categories on the education and performance of the MRR teacher.

| Categories | Definition |

|---|---|

| Specificity of areas | Highlight the specificities of each of the TPSE categories. |

| Professional Development | Highlight the need for training improvement in specific areas of TPSE to be attended at MRR. |

| Education | Emphasize that they have training in the area(s) they work. |

| Work experience | Emphasize the experience as a way to prepare them to perform with all TPSE. |

| Intersectoriality | Highlight the need or lack of performing with other sectors. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

These categories were constructed in an attempt to differentiate and refine the comments of the teachers. However, there is communicability between them, but we try to consider, in each narrative used as an illustration, which aspect stood out in their justifications.

4 Results7

When considering our objective of analyzing the relationship between the education and performance of the MRR teacher at the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo, which exercises one of the forms of organization of the SES, the attendance of the student in the extra hour classes, in face of the proposal of inclusive education, in our questionnaire, we organized a section of questions about the training and performance of the SES teacher, with an introduction that pointed out the following:

Ordinance no. 8,764/2016, in article 43, defines the duties of the SES Teacher and establishes that his/her performance involves all target students of Special Education, that is, those with disabilities, GDD and high skills/ giftedness. (Oliveira, 2018a, p. 7).

In view of this statement, we asked the respondent teachers: “Do you consider yourself trained/prepared to work in all areas related to the target population of special education (disability, GDD and high skills/giftedness)?” (Oliveira, 2018a, p. 7). The responses indicated that 150 of them (84%) replied that they did not feel prepared and 29 (16%) stated that they did, which shows a problem in relation to the training and performance of the MRR teacher with all the categories. As a complement, all teachers were asked to comment on their responses, those who responded positively and those who responded negatively in relation to the preparation for the exercise of work with the entire TPSE.

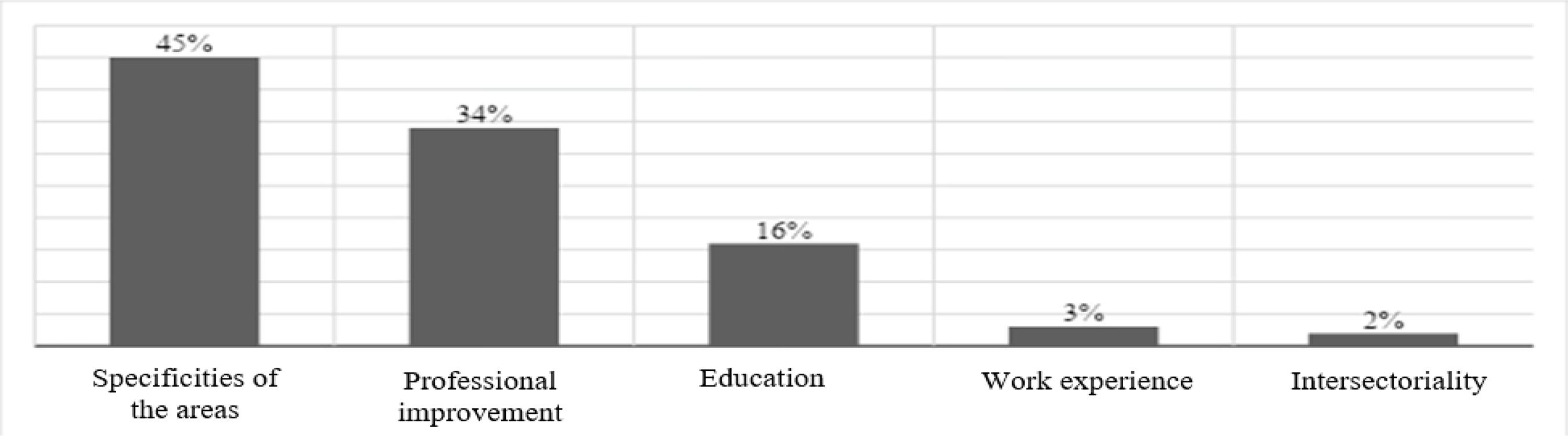

Of the 179 respondents, 81 (45%) presented justifications regarding the preparation for work with the entire target group of Special Education, due to their experience of working with all areas, 61 (34%) referred the need for professional improvement, that is, to expand areas of their training, 28 (16%) commented that they had training in the areas or categories with which they worked, 5 (3%) referred to their work experience as a way to become able to work with all the diversity of PAEE and 4 (2%) pointed out the absence of intersectoral action and the need for partnerships with the health area as a way to enable the exchange of knowledge and guidelines for action with the entire TPSE. In Figure 2, we can graphically observe the panorama of the teachers’ justifications in relation to their responses on preparation/training to work with all the diversity of the TPSE, according to requirements established in the national and São Paulo legislation.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2 Education and performance with all the diversity of the TPSE.

Eighty-one (45%) teachers justify that their difficulties in performing with all the diversity of the TPSE are related to the different specificities of each of the areas or categories of this population, which are complex and require varied skills to adequately answer the needs of each one of those students. As an example, we transcribed some of their answers:

As much as I always seek to specialize myself and take courses, I am not multifunctional nor do I believe that one day I will be. I may have basic knowledge about the different areas, but I don’t know about everything. GDD, for example, is an area with different studies and approaches. (P09)8.

The education of SES that I had was with deepening in deafness. When I took the course, I went deeper into deafness. Even so, it took another six years of specific courses to better understand Brazilian Sign Language and deaf culture. Therefore, other areas such as visual and intellectual disabilities were only seen at a glance. (P26).

The scope of Special Education is very broad and I do not consider myself apt, as I specialize in the area of intellectual disability. I don’t know Braille or Brazilian Sign Language, which would make it difficult for these students to attend. (P113).

I still feel unprepared to work with hearing, visual and multiple impairments. Despite having obtained a great formation in Special Education, I think it is necessary and urgent continuous training in this area. (P175).

As we can see, the teachers report being aware of the specificities of the areas as an issue of the greatest importance, because, if there is no knowledge on how to identify and eliminate or reduce the learning barriers, how to carry out an appropriate pedagogical work that meets the needs of the TPSE? Many of them mentioned, mainly, the lack of knowledge of Brazilian Sign Language and Braille as well as not having knowledge about the area of high skills/giftedness, or multiple disabilities.

When commenting on their difficulties in dealing with all the diversity of the TPSE, 61 (34%) teachers stated that, although they had training and work experience in some of the areas, they still felt the need for professional improvement to adequately adapt the training in order to respond to the specific needs of the TPSE. The teachers place on themselves the responsibility to seek improvement to carry out their didactic activity to their satisfaction, which, surely, is also part of the permanent education movement of those who work in the area of education. However, this individual professional action does not relieve the education networks of their obligation with the guarantee of continuing education for educational professionals, as established by Law no. 9,394/1996, in its article 62, sole paragraph.

In this direction, the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo has revealed itself as a network that has sought to enable its teachers to make this improvement, by proposing courses promoted by the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo, from the Division of Special Education, or even by CEFAI (Center for Education and Support for Inclusion). Despite this situation, they continue to seek professional improvement. The comments of the research participants revolve around the following arguments:

In addition to graduate school, I try to participate in all training offered by the Municipal Education Network and courses related to my students’ disabilities. (P06)

Although my training is specific in high skills/giftedness, I take courses in other areas and look for information to meet the demands related to the work I do at school. (P66).

I think we always have to learn more, acquiring knowledge and experiences. We don’t know everything about all the disabilities. (P135).

Undoubtedly, we cannot fail to discard the personal movement of each teacher so that he/she becomes more and more competent. This requires study and effort on a personal level, in addition to competence and creativity to seek resources and strategies that are consistent with the learning characteristics of each student. Furthermore, we must not forget that even students of similar conditions have different needs, because it is not the individual circumstance itself that determines the pedagogical work, but its implications for teaching that guarantees learning. It is important to note that the teacher’s own workday at the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo (Law no. 14,660, of December 26, 2007) provides for collective training meetings, which aim to enable the improvement of their training and, as a consequence, may include topics that creates conditions to improve the teacher’s performance with all the diversity that makes up the TPSE.

When commenting on the reasons why they do not feel prepared to act with all the diversity of the TPSE, 28 (16%) of them referred their comments to the training itself, that is, they specialized in a certain category and, in practice, they are faced with other situations that would require knowledge not acquired in the training course initially carried out, some in Special Education, in general, others in a specific category of the TPSE. As an example, we quote some of the answers:

Specializations in the area of Special Education are specific to a specific area of activity. Although my professional performance is based on the elimination of barriers, I realize that the quality of the SES is high when I work in the area in which I did the specialization, because I can see the necessary instruments for faster access to the common classroom and its preparation. (P31).

My graduate studies at the time were geared towards intellectual disabilities, so readings and internships were carried out with this target population, in addition to teaching at a special school for intellectual disabilities. (P70).

I did two graduate courses focused on deafness, so I feel more prepared to work with the Deaf. (P81).

The basis of my training is in intellectual disability and global disorders. To work in all areas, specific training is required for each area of activity. (P120).

I have no training for high abilities and I miss being better prepared to work with students with GDD. (P144).

We observed that the teachers refer to their training and the search to learn more; however, it is worth mentioning the statement of P31, who considers carrying out his work with a focus on eliminating barriers, but admits that even this becomes easier in the area of his education.

When commenting on the answer about the preparation to work with all TPSE categories, we found the reference of five teachers (3%) to work experience as a way of graduating, as we can see from the following narratives:

With years of practice, I manage to do my job well. I’m just inexperienced in high skills. (P15).

The area in which a teacher works provides experience and greater security and competence over time. (P130).

I consider that I have training/preparation to work with the students who I attend to, a lot of knowledge was actually acquired, with the exercise and the construction of practices. (P171).

Certainly, experience makes it possible for us to acquire more knowledge and security in carrying out pedagogical work, but it can also be dangerous if we sustain educational action only in this aspect of everyday action, as this distances us from scientific and reflective thinking, made possible by theoretical and its relationship with practice, in the sense of the educational praxis pointed out by Paulo Freire (Streck, Redin, & Zitkoski, 2008).

Another justification that can be identified in the teachers’ responses, about the difficulty in working with all the diversity of the TPSE, was the importance of partnerships, mentioned by four teachers (2%):

There are cases in which we need to act with the physical restraint of students with excessive psychomotor agitation, with associated autism, without any support from the mental health network, as it is an evident behavioral aspect, children, adolescents and young people without contour or intervention together with mental health services, including indicating emotional and psychological vulnerability on the part of their families who report fragility, including in the daily handling with their children, on issues such as daily living activities and commuting to medical appointments. (P43).

Although I have taken several courses, distance education in autism, high skills/giftedness ... we do not have sufficient and satisfactory training and practice. And, when we need to refer to speech therapy, occupational therapy, psychology, training centers for high skills, we fail. Lack of partnership with health. Families cannot afford it. (P44).

I am very dedicated, but I am not prepared to handle “all” cases. Each case has its complexity and requires us, the pedagogical team of the School Unit and SES teacher, to study hard ... We need the Team/ Basic Health Unit/Psychosocial Care Centers to make periodic/biweekly visits ... We need more training with psychiatrists, psychologists, neuropediatricians, physiatrists. (P71).

Teachers point out the absence of intersectoriality for their work, from the partnership in the educational unit itself, in a perspective of collaborative work and co-responsibility, as well as the partnership with other areas that could support the educational action with TPSE students, such as the family, mental health, or the social equipment that can enable collective thinking about the needs of some specific cases, which are often neither easy nor simple, so they can impose the prerogative of joint and collective actions, at school as well as with other sectors of the public administration, such as the health area to ensure their learning and well-being.

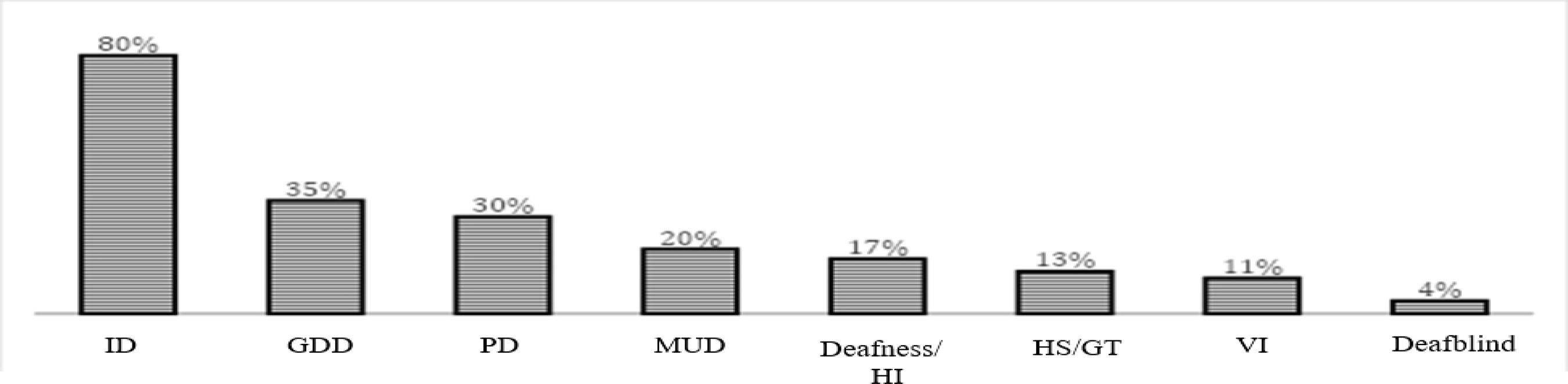

Still considering the preparation to act with all the diversity of the TPSE, we asked the participants in which areas they considered to have better training to act and we observes the situation systematized in Figure 3.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 3 TPSE category that the MRR teacher has the best training for.Legend: ID: intellectual disability; GDD: global developmental disorders; PD: physical disability; MUD: multiple disability; HI: hearing impairment; HS/GT: high skills/giftedness; VI: Visual impairment.

The category that 143 of the teachers (80%) most indicated was that of intellectual disability, followed by 63 of them (35%) who considered it to be GDD. This data draws our attention, since they are the two most complex categories for defining their needs and, even if we consider the diagnostic issue, because, we know, it is difficult to assess due to the difficulty of establishing criteria and resorting to more subjective aspects.

In the area of physical disability, 54 teachers (30%) considered to be better prepared, 36 (20%) in multiple disabilities, 30 (17%) in deafness/hearing impairment, 23 (13%) in high skills/giftedness, 19 (11%) in visual impairment and 8 (4%) of them in deafblindness. We observed that, in the areas in which, in general, more pedagogical resources or even assistive technology (AT) are used, we have a variation of 4% to 30% of the teachers who feel qualified to work with these students, which may indicate that, when mentioning the areas of intellectual disability or GDD, they considered to be aware of the fact that, apparently, very specific pedagogical resources are not needed, although this is not the case, since students with ASD need a more systematic teaching structure and may need AT resources, such as that of Alternative and Supplementary Communication, as well as in the area of physical disability; however, the teachers perceive themselves to be better prepared.

It also draws attention that 17% of them considered themselves prepared to work with multiple disabilities, although they do not detail the characteristics of the students they assist; however, this indicates their presence at the Municipal Education Network of São Paulo. The fact that they consider themselves qualified may indicate the occurrence of the offer of training courses by the network itself, internally, or the fact that São Paulo is characterized as a municipality in which there are specialized institutions that promote training courses, which can being sought after by the teachers from São Paulo.

Regarding deafness/hearing impairment, on the one hand, although we have to consider that there is a very particular issue that is the domain of the Brazilian Sign Language, we were surprised by the fact that 13% only consider themselves qualified to work with deaf students, since, as we have previously presented, Ordinance no. 8,764/2016 dedicates 37% of its articles to dealing with bilingual education; on the other hand, perhaps the focus is more on bilingual schools or polo schools, than on the training of the SES teacher, who works in MRR with the deaf student.

The preparation to work in the area of high skills/giftedness was considered by 13% of the teachers, but this is an area that still presents some invisibility and difficulty in identifying the student as well as the offering of curricular enrichment, especially if we think about the Triadic Model of Enrichment (Renzull, 2014)9.

Working with visually impaired and deafblind students requires technical knowledge, such as the development of tactile or kinesthetic resources, use of AT10, guidance and mobility to facilitate or provide full access to the knowledge conveyed by the school curriculum for these students, so it is expected that only 11% and 4% of the teachers consider themselves prepared to work with these categories, respectively.

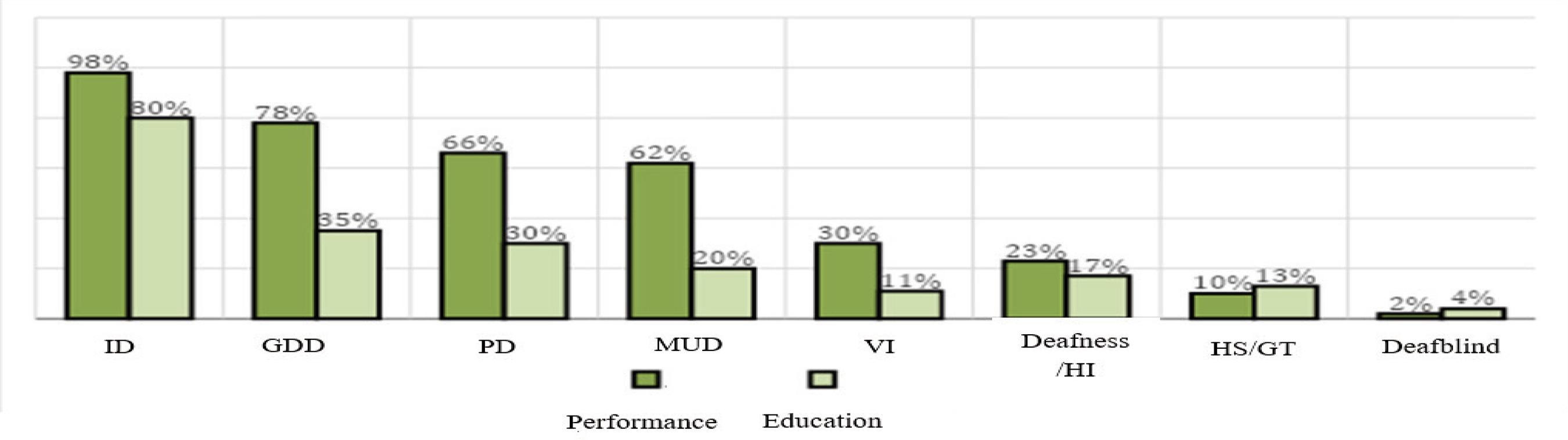

When observing this scenario about teacher preparation or training to work better with certain areas than with others, we raise doubts: could it be due to the fact that they do not dominate the more specific resources of the other categories, as we discussed? Or would it be linked to their training in certain areas? To elucidate such inquiries, we cross-referenced the available data on the areas of training and those of performance, the results of which were recorded using Figure 4.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 4 Relationship between training and performance of the MRR teachers.Legend: ID: intellectual disability; GDD: global developmental disorders; PD: physical disability; MUD: multiple disability; HI: hearing impairment; HS/GT: high skills/giftedness; VI: Visual impairment.

Figure 4 allows us to realize that the performance of the teachers does not correspond to their training, that is, they work with some areas for which they have no training. There is a greater approximation in the areas of high skills/giftedness and deafblindness, with a gap between training and performance of 3%, with more graduates in these categories than working with these students. Regarding intellectual disability and deafness/hearing impairment, approximately 18% and 17% of the teachers, respectively, do not have specific training for their work, which is quite worrying, since, in the education of the deaf, it is necessary to deal with the constitution of a language and the teaching of Portuguese as a second language, which requires, among other knowledge, mastery of the specificities of that area and mastery of Brazilian Sign Language. Obviously we are not disregarding the knowledge necessary to deal with the condition of intellectual or hearing impairment, but constitution of language is a fundamental factor for intra and interpsychic development, therefore an unquestionable relationship between language and thinking (Vygotsky, 2001).

There are other problems in the relationship between training and performance listed by the respondents. The areas of GDD and multiple disability have a lag of 43% and 42% respectively; in physical disabilities, 36%; and visually, 19%. These are important differences, whose meaning lies precisely in how to act in response to the needs of these students if there is no training that can guide the planning and action of the MRR teacher.

Several aspects about the performance in MRR were considered by the teachers and brought to the center of the discussion the need for a multidisciplinary team of professionals from different areas for joint action, improvements in the special education policy, constitution of centers and support and, even, the question of the demand or lack of interest of ordinary teachers, referring to the inclusive education policy itself and its implications for the daily life of the school and the interior of the classroom. Assisting diversity in the classroom and the needs of TPSE requires a change in the way of teaching and organizing pedagogical work; otherwise, full responsibility for ensuring the permanence of these students in the common class and for their access to higher levels of education, with the right to learning, is shifted to SRM. This is a fact and it would not be an exaggeration to say that, in Brazil, an inclusive education policy has not yet been established (Oliveira, 2018b), as if the opening of services was sufficient to drive the changes resulting from a policy that calls for a school for everyone.

5 Final considerations

There are many challenges to public education systems or networks in the implementation of the school inclusion policy in Brazil, which guarantees the registration of the TPSE in the common class. However, it is certainly with the generation of favorable conditions for their access to higher levels of education, with learning, that the concern has fallen, since the admission does not exhaust the commitment to guarantee the right to quality education for all.

On this basis, it has been established, since the Federal Constitution of 1988, as an equity factor, that this student should be guaranteed the SES, regulated in later regulations (Resolution no. 4/2009), organized based, predominantly, on offer in the extra hour classes in MRR, under the guidance of teachers with some level of training in Special Education. However, the association between the room being multifunctional and the requirement for a multi-category teacher was established without, in fact, national guidelines and training policies for this professional being defined and implemented.

This scenario motivated the realization of the research on screen and, from the analysis of the answers to the questionnaire applied to teachers working in MRR in the São Paulo school network, we could infer that the majority (84%) believes that they have insufficient training to meet the demands of the student enrolled in the SES of the MRR, who receive enrollments from students classified in the various categories that make up the TPSE.

The training courses administered in this education network with the objective of training teachers of its staff in the area of Special Education were based on the focus model in a given category of TPSE. This results in the gap identified between training in Special Education and the requirements of MRR practice.

Part of them affirms that the deepening of knowledge about a given category gives greater quality to their work, as this makes it possible to recognize the specific needs of students and plan more assertive pedagogical responses. Faced with this challenge, the teachers registered that they sought to carry out further training on topics that could assist them in the SES. Part of these courses, workshops, lectures, among other modalities, were offered by the education network itself and the others are attributed to their own initiatives, which is also expected of a professional of the educational area.

Another highlight is the fact that they attribute to the experience in the Special Education area the acquisition of knowledge to meet the diversity of conditions manifested by the MRR students. It is undeniable that professionals perfect their practice and also their knowledge in the years of experience in education, in this case in MRR, but it is also unquestionable that theoretical-practical training shortens this process of approximation between theoretical foundations and pedagogical practice. The risk that must be avoided is that the school inclusion policy remains provisional and precarious, always waiting to reach the levels of quality required by the commitment to quality education for all.

A strong indication of this research is to provoke questions about the training of teachers to work in Special Education with inclusive guidance adopted in recent years, since the respondents to the questionnaire problematized the insufficiency of knowledge to guarantee the SES, considering the specificities of each TPSE category and brought with conviction the highest quality assessment when their knowledge coincides with the specific needs of the student or group they assist. Despite the subterfuges they declared to use to fill the gaps in their training, the teachers considered that these subterfuges are insufficient, which compromises the Special Education area to be involved in the debate and in the construction of new and other training proposals.

5Theoretically, in each CEFAI, there should be at least four PAAI, one for each of the areas: deafness, physical, intellectual and visual disabilities, but this is not always the case, as it depends on the region, the attributions and the staff of trained specialists and available to assume the role.

7Some of the data described here were partially presented at the 18th Meeting of Núcleo de Marília (2019).

8Teachers’ narratives will be identified with a capital letter P, followed by the teacher’s numeric indication, in accordance with our data records.

9Triadic Enrichment Model, according to Renzulli (2014), consists of three types of enrichment. Type I aims at collective actions and projects that involve all students; Type II proposes greater involvement with certain areas of knowledge and, therefore, can be targeted at certain groups of students, although it can also be developed in the context of the common classroom or in the MRR; and Type III is directed towards more advanced studies, which certainly go beyond the possibilities of the school system and, many times, will require external partnerships in order to really deepen knowledge in certain specific areas or themes.

10AT is characterized by being a very broad area of knowledge, classified in certain categories and directly related to objectives of functionality, autonomy and participation (Bersch, 2017). Obviously, not all are specific to the areas of visual impairment and deafblindness, as this is a proposal for knowledge and interdisciplinary action, but certainly many of its resources contribute very closely to students’ visual and hearing access.

REFERENCES

Barroco, S. M. S. (2012). Sala de recursos e linguagem verbal: em defesa do desenvolvimento do aluno. In M. G. D. Facci, M. E. M. Meira, &, S. C. Tuleski (Orgs.), A Exclusão dos “incluídos”: uma crítica da Psicologia da Educação à patologização e medicalização dos processos educativos (pp. 277-298). Maringá: EDUEM. [ Links ]

Bersch, R. (2017). Introdução à Tecnologia Assistiva. Recuperado 14 de abril de 2018 de https://www.assistiva.com.br/Introducao_Tecnologia_Assistiva.pdf [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Recuperado em 14 de abril de 2018 de 2018 http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicaocompilado.htm [ Links ]

Decreto nº 57.379, de 13 de outubro de 2016. Institui, no âmbito da Secretaria Municipal de Educação, a Política Paulistana de Educação Especial, na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de http://legislacao.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/leis/decreto-57379-de-13-de-outubro-de-2016 [ Links ]

Educação Especial:Manual de apoio à prática. (2008). Direção Geral de Inovação e Desenvolvimento Curricular. Direção Geral de Serviços de Educação Especial e Apoio sócio-educativo. Lisboa, Portugal: Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Galvão Filho, T. A. (2009).Tecnologia assistiva para uma escola inclusiva: apropriação, demanda e perspectivas (Tese de Doutorado). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. [ Links ]

Hodgan, W., & Hodgan, K. (2007). Modelo de Desenvolvimento do Programa Son-Rise - entendendo a importância do desenvolvimento social e criando um currículo para o crescimento social de sua criança. Recuperado em 14 de abril de 2018 de https://docplayer.com.br/51839473-Modelo-de-desenvolvimento-do-programa-son-rise.html. [ Links ]

Hora, G. S., & Miranda, T. G. (2017). Concepções pedagógicas de docentes da educação especial. Revista de Estudios e Investigación em Piscología y Educación, 11, 235-239. DOI: 10.17979/reipe.2017.0.11.2838 [ Links ]

Jesus, D. M., & Borges, C. S. (2018). Formação inicial de professores na perspectiva inclusiva: quais os desenhos?. In A. A. S. Oliveira, K. A. Fonseca, & M. R. Reis (Eds.), Formação de professores e práticas educacionais inclusivas (pp. 29-42). Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Lei nº 14.660, de 26 de dezembro de 2007. Dispõe sobre alterações das Leis nº 11.229, de 26 de junho de 1992, nº 11.434, de 12 de novembro de 1993 e legislação subseqüente, reorganiza o Quadro dos Profissionais de Educação, com as respectivas carreiras, criado pela Lei nº 11.434, de 1993, e consolida o Estatuto dos Profissionais da Educação Municipal. Recuperado em 14 de abril de 2018 de http://legislacao.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/leis/lei-14660-de-26-de-dezembro-de-2007 [ Links ]

Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Recuperado em 14 de abril de 2018 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L9394.htm [ Links ]

Machado, R. (2011). Formação de Professores. Inclusão: Revista da Educação Especial, 6(1), 4-7. [ Links ]

Manual de Orientação: Programa de Implantação de Salas de Recursos Multifuncionais. (2010). Secretaria da Educação Especial. Brasília: Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Mendes, E. G. (2009). Inclusão Escolar com colaboração: unindo conhecimentos, perspectivas e habilidades profissionais. In L. A. R. Martins, J. Pires, & G. N. L. Pires (Orgs.), Políticas e Práticas Educacionais Inclusivas (pp. 19-51). Natal: EDUFRN. [ Links ]

Mendes, E. G., & Malheiros, C. A. L. (2012). Sala de recursos multifuncionais: é possível um serviço “tamanho único” de atendimento educacional especializado?. In T. G. Miranda, & T. A. Galvão Filho (Orgs.), O professor e a educação inclusiva:formação, práticas e lugares (pp. 343-359). Salvador: EDUFBA. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. S.(2009). A política de formação de professores para educação especial: a ausência de diretrizes ou uma política anunciada? In S. Z. Pinho (Ed.), Formação de Professores: o papel do educador e sua formação (pp. 257-271). São Paulo: Editora UNESP. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. S.(2018a). Política Pública de Educação Especial: análise do Atendimento Educacional Especializado realizado em salas de recursos multifuncionais (Instrumento de coleta de dados - Questionário Google Docs- Pós-Doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. S.(2018b). Conhecimento escolar e deficiência intelectual. Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. S. (2019). Política Pública de Educação Especial: análise do Atendimento Educacional Especializado realizado em salas de recursos multifuncionais (Relatório Científico - Estágio Pós-doutoral). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. S., & Drago, S. L. S. (2012). A gestão da inclusão aluno na rede municipal de São Paulo: algumas considerações sobre o Programa Inclui. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 20(75), 347-372. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P. S., & Mendes, E. G. (2017). Análise do projeto pedagógico e da grade curricular dos cursos de licenciatura em educação especial. Educação e Pesquisa, 43(1), 263-279. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201605145723 [ Links ]

Otalara, A. P., & Dall’acqua, M. J. C. (2016). Formação de professores para alunos público-alvo da educação especial: algumas considerações sobre limites e perspectivas. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, 11(2), 1048-1058. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21723/riaee.v11.esp2.p1048-1058 [ Links ]

Pagnez, K. M., Prieto, R. G., & Sofiato, C. G. (2015). Formação de professora e educação especial: reflexões e possibilidades. Olh@res, 3(1), 32-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34024/olhares.2015.v3.320 [ Links ]

Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. (2008).Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=16690-politica-nacional-de-educacao-especial-na-perspectiva-da-educacao-inclusiva-05122014&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

Portaria nº 8.764, de 23 de dezembro de 2016. Regulamenta o Decreto nº 57.379, de 13 de outubro de 2016, que “Institui no Sistema Municipal de Ensino a Política Paulistana de Educação Especial, na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva”. Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de https://goo.gl/V36Lm8 [ Links ]

Renzulli, J. (2014). Modelo de enriquecimento para toda a escola: Um plano abrangente para o desenvolvimento de talentos e superdotação. Revista Educação Especial,27(50), 539-562. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/1984686X14676 [ Links ]

Resolução CNE/CP nº 1, de 15 de maio de 2006. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Curso de Graduação em Pedagogia, licenciatura. Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/rcp01_06.pdf [ Links ]

Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 11 de setembro de 2001. Institui Diretrizes Nacionais para a Educação Especial na Educação Básica. Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/CEB0201.pdf [ Links ]

Resolução nº 4, de 2 de outubro de 2009. Institui Diretrizes Operacionais do Atendimento Educacional Especializado na Educação Básica, modalidade Educação Especial. Recuperado em 10 de março de 2018 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/dmdocuments/rceb004_09.pdf [ Links ]

Silva, O. O. N., Miranda, T. G., & Borda, M. A. G. (2017). Trabalho docente e atendimento educacional especializado: uma análise da produção acadêmica no portal de teses e dissertações da capes - 2013 a 2016. Revista da FAEEBA - Educação e Contemporaneidade, 26(50), 225-239. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21879/faeeba2358-0194.2017.v26.n50.p225-239 [ Links ]

Streck, D. R., Redin, E., & Zitkoski, J. J. (2008). Dicionário Paulo Freire. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Vygotski, L. S. (2001). A Construção do Pensamento e Linguagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Received: December 04, 2019; Revised: January 22, 2020; Accepted: January 25, 2020

texto en

texto en