Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

versão impressa ISSN 1413-6538versão On-line ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.3 Marília jul./set 2020 Epub 12-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-54702020v26e0143

Research Report

Analysis of Requests to the Public Ministry on the Right of People with Disabilities to Education

2Mestre em Educação pela Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo (USP). São Paulo/São Paulo/Brasil. E-mail: larissa.pedott@gmail.com.

3Doutora em Psicologia Social. Professora no Departamento de Filosofia da Educação e Ciências da Educação. Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo (USP). São Paulo/São Paulo/Brasil. E-mail: b.angelucci@usp.br.

This paper analyzes the requests regarding the right to education of the Special Education target population that reach the Special Education Action Group (Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação - GEDUC) of the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo, from its creation in 2011 until the end of 2017, totaling 163 procedures. It seeks to understand with what purpose, in what manner and by which sectors of society such an instance is triggered. The following categories were used: proponents, types of claims, education network to which they refer and variation in the number of requests over the years. It is noticed that most of the requests addressed to the Public Ministry are proposed by family members of people with disabilities, referring to claims involving support for schooling in common classes of regular schools, especially in the state school system of São Paulo. As for the variation in requests, there is a large number of requests in the first years after the creation of GEDUC, with a decrease in recent years, which could be related to the way this Group has been operating. There is a reconfiguration of GEDUC’s actions over the period from 2011 to 2017, with the presence of elements representative of the willingness to act in the transposition of the initial complaint to the underlying effective demand. Thus, instead of direct responses requiring the execution of the request by the represented parties, more time-consuming actions are found to promote dialogue on the problem posed. It is understood, therefore, that requests can be used as a tool to expand and qualify the dialogue between the Public Ministry, civil society and the Executive Branch, aiming at the universalization of the right to education.

KEYWORDS: Special Education; Inclusive Education; Public policies; Public Ministry; Disability

Este trabalho analisa as solicitações referentes ao direito à educação do público-alvo da Educação Especial que chegam ao Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação - Geduc - do Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo, desde sua criação em 2011 até o final de 2017, totalizando 163 procedimentos. Busca-se depreender com que intuito, de que maneira e por quais setores da sociedade tal instância é acionada. Utilizaram-se as seguintes categorias: proponentes das solicitações, tipos de reivindicações, rede de ensino a que se referem e variação na quantidade de solicitações ao longo dos anos. Percebe-se que a maior parte das solicitações endereçadas ao Ministério Público são propostas por familiares das pessoas com deficiência, referindo-se a pleitos envolvendo suportes para escolarização em classes comuns de escolas regulares, sobretudo, na rede estadual de ensino de São Paulo. Quanto à variação de solicitações, nota-se um grande número de solicitações nos primeiros anos após a criação do Geduc, com um decréscimo nos últimos anos, o que poderia relacionar-se à maneira como este Grupo vem atuando. Verifica-se a reconfiguração das atuações do Geduc ao longo do período de 2011 a 2017, com a presença de elementos representativos da disposição para atuar na transposição da queixa inicial para a demanda efetiva subjacente. Assim, em vez de respostas diretas requerendo a execução da solicitação por parte das/os representadas/os, são encontradas ações mais demoradas de promoção de diálogo sobre o problema posto. Entende-se, portanto, que as solicitações podem ser utilizadas como ferramenta de ampliação e de qualificação do diálogo entre Ministério Público, sociedade civil e Poder Executivo, visando à universalização do direito à educação.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Educação Especial; Educação Inclusiva; Políticas públicas; Ministério Público; Deficiência

1 Introduction

This research deals with the Education and Justice interface, in the context of guaranteeing the right to education for the target population of Special Education, namely: people with disabilities, global developmental disorders or giftedness (National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education [Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva - PNEEPEI], 2008). The object of analysis consisted of procedures instituted by the Special Education Action Group (Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação - GEDUC) of the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo, composed of prosecutors, acting in partnership with professionals from Social Service and Psychology, the latter being the members of the Psychosocial Technical Advisory Center (Núcleo de Assessoria Técnica Psicossocial - NAT). It must be considered that GEDUC’s work is to identify, prevent and suppress acts or omissions corresponding to the violation or threat to diffuse interests , related to the right to education, in particular to the principles enshrined in the Federal Constitution of 1988.

Thus, the general objective of this work was to analyze the requests received by GEDUC regarding the guarantee of the right to education for the target population of Special Education, since its creation in 2011 until the end of 2017, in order to understand with what purpose and how this instance is triggered by the different sectors of society. To this end, 163 requests made by various social agents to the Public Ministry in the period between the years 2011 and 2017 were systematically addressed, related to the guarantee of the right to education by the target population of Special Education.

The specific objectives were: a) to characterize the requests received by GEDUC regarding its proponents, the types of claims, the education network to which it refers and how the variation in the number of requests per subject has been occurred over the years; b) to characterize the way GEDUC has acted since receiving the request, listing the main articulations undertaken since the initial complaint.

1.1 Special education

In 2006, the United Nations (UN) approved the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Decree no. 6,949, of July 9, 2009), systematizing the studies and movements resulting from the last decade of the 20th century, affirming the need for public policy designs based on Human Rights principles. As Palacios (2008) points out, when discussing the history of the Convention’s elaboration:

El objeto, en principio, no fue crear nuevos derechos, sino asegurar el uso del principio de no discriminación en cada uno de los derechos, para que puedan ser ejercidos en igualdad de oportunidades por las personas con discapacidad. Para ello, se debió identificar, a la hora de regular cada derecho, cuales eran las necesidades extra que debían garantizarse, para lograr adaptar dichos derechos al contexto específico de la discapacidad. (p. 269).

The document is considered the great symbol of international recognition of the importance of the topic, involving a worldwide discussion, with its Optional Protocol signed on March 30, 2007 by Brazil, deciding to adhere to the Convention, promulgating Decree nº 6,949, of 25 August 2009, which was approved by the National Congress, becoming this way a Constitutional Amendment.

In the same period, the Ministry of Education (MEC) released the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education (2008), known in Brazil as PNEEPEI. As Kassar (2011) states:

The impact of international agreements and commitments on the formulation of policies, programs and actions is undeniable. The very conception of human rights is the formatting of a man’s ideas, which historically corresponds to the Western-liberal idea of justice and equality. However, in the complexity of the formulation of public policies, the interference relationships are not one-sided nor are they mechanical. (p. 54).

The 2008 Policy, result of tension and disputes that remain until today, affirms schooling in common classes of regular schools as a principle of guaranteeing the right to education, with full access to the curriculum through the removal of barriers and provisions of supports.

On July 6, 2015, the Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities was instituted, which, inspired by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, represented an important advance in the promotion of rights, aiming at guaranteeing rights fundamental to this population segment. The Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities considers a person with a disability to be one who has a long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment, which, in interaction with one or more barriers, can obstruct a full and effective participation in the society on equal terms with other people.

The Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities dedicated a specific chapter to educational provision, ratifying, for example, the illegality of charging extra fees by private and public educational institutions for enrolling students with disabilities or providing the necessary support. Regarding the offer of supports, it is recommended that it should be organized based on the recognition of and coping with barriers that prevent the student from being in the common classroom. The barriers are of the most distinct natures: urban, architectural, attitudinal, technological, in transport, communication and information (Law no. 13,146, of July 6, 2015). The work focuses on the planning of intra-school and intersectoral actions to face these impediments, present in the social environment.

1.2 Public ministry

According to the National Organic Law of the Public Ministry, which provides for general rules for the organization of the Public Ministry of the States, the Public Ministry is an autonomous public institution, which, not belonging to any of the so-called three Brazilian Powers (Judiciary, Executive and Legislative), is configured as an essential body to justice (Law no. 8,625, of February 12, 1993).

The 1988 Federal Constitution is a major milestone in the history of the Public Ministry as it promotes important changes in the role played by the institution in the system of guaranteeing rights, giving it the role of defender of the democratic and rights state and the protection of citizenship and citizens’ social interests. The concept of citizenship adopted by the 1988 Federal Constitution is that of a set of basic rights and obligations of all those who are subject to the laws that organize life in society. Thus, the Public Ministry must ensure the defense of the constitutional rights of citizens as the defender of the people, and may, for this purpose, turn against any power of the Republic or entity that provides public service or public relevance.

In the city of São Paulo, the Public Ministry acts through the Public Prosecutor’s Office and Special Groups working in the following areas: consumer, criminal, Human Rights, education, electoral, elderly, childhood and youth, public heritage, public health, urbanism and environment. The Action Groups are bodies created with the specific purpose of improving the performance of the Public Ministry in some area of its function, especially by the election of a prosecutor who will concentrate his/her performance so that it does not happen in a diffused way. The existence of the Action Groups needs to be linked to criteria and objectives and to the other Public Ministry enforcement bodies. It is worth mentioning that, as it is not a Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Action Group may have a finite term of existence, and may be dissolved if its existence is evaluated as unnecessary (Law no. 8,625, of February 12, 1993). Among the Special Action Groups created in the Public Ministry is the Special Education Action Group (Normative Act no. 700, of May 31, 2011).

The Normative Act nº 724/2012, of January 2012, created the Psychosocial Technical Assistance Center, inaugurating the professional performance of psychologists and social workers in a different perspective, not only referring to individual cases, but with a broader look at the implementation of public policies. According to Arruda and Santos (2012), the Center has as premise for its creation

[...] achieve a comprehensive and in-depth knowledge of the social reality of the State of São Paulo, subsidizing actions and decisions within the institution. Thus, it also strives for technical action aimed at analyzing the implementation and functioning of public policies, always with a more collective look at the demands of individual service. (p. 3).

The Center is composed of social workers and psychologists, organized in the areas of: childhood and youth; education; housing; urbanism and Human Rights (Normative Act no. 724 of January 13, 2012).

GEDUC started its activities in 2011 with the objective of enhancing and contributing to the implementation of public education policies, with claims that deal with collective educational rights, not acting in cases of strictly individual violations of rights, according to the Normative Act no. 672, of December 21, 2010. The birth of such an action group in the Public Ministry, aimed at a specific agenda, corresponded to a new model of action, which had a specialized prosecutor, working with a specific area and in continuous dialogue with city and state managers. In the context of interdisciplinary action between the Psychosocial Technical Advisory Center and GEDUC, a work proposal has been designed with the intention of overcoming a legalistic view of social reality, considering the country’s socio-historical issues and seeking to respect the life history of those with whom the Public Ministry acts in the realization of the fundamental right to education (Silva, Silva, & Pedott, 2017).

GEDUC works with issues related to the violation of the right to education, either by spontaneous demand (when it is triggered by any member or association of civil society) or by purposeful action (in case it becomes aware of any violation through the media or through visits to the Municipal and State Education Departments and their bodies). Numerous spontaneous requests to GEDUC, through public service channels, are linked to violations in the provision of Special Education from the perspective of inclusive education.

2 Method

This research used documentary analysis. Initially, a survey of the requests related to Special Education was made, forwarded to GEDUC from the creation of the group, in 2011, until December 2017, and which have already been archived (there was, therefore, the understanding that the reason for the request found its possible outcome). The documents were obtained through access to the physical file of the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo (available in the headquarters building of the Public Ministry in the city of São Paulo) and the Integrated System of the Public Ministry (known as SIS MP). The permission for access was requested by the researcher to the prosecutors of GEDUC, and the reading of the procedures in full was authorized, provided that they were carried out on site . It was also possible to have contact with the procedure registration sheet, prepared by GEDUC employees. All physical files of the procedures are available for public access at the headquarters of the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo, except for procedures that are confidentially processed for the protection of the parties involved.

The decision to work only with archived procedures is due to the fact that the archiving of a procedure happens when there is an understanding of the outcome given to the requested object. Thus, the archived procedures bring together a set of information throughout their processing, which allows to raise more information for the purpose of qualifying the performance of the Public Ministry.

The systematized information was analyzed from a socio-analytical and, thus, qualitative reading, guided by the action research methodology. The starting point of the intention in the production of knowledge is the insertion of the researcher as a component part of the institution to be researched. In this way, the research, as outlined, produced and produces action on the field, with direct impacts on the activity in which the researcher participates, considering the field as a dynamic set and not as a watertight object (Thiollent, 1986).

2.1 Procedures

The analysis initially involved the universe of 1,223 procedures archived by GEDUC from its creation (2011) until the end of 2017, involving various objects related to the right to education. Of the total number of procedures, 173 were identified as referring to the right to Special Education for having as a key element the possible violation of quality assurance and access to education by the target population of Special Education. However, it was not possible to access ten procedures, which were not available for consultation during the research period, reaching the number of 163 procedures analyzed.

For the characterization, all documents referring to the 163 procedures mentioned above were read, in order to understand with what purpose and in what way the GEDUC has been activated by the different sectors of society. The categories listed for analysis of the set of 163 files were chosen in order to approximate the type of request that reaches the Public Ministry. The category “proponent” aimed to investigate and identify the individuals that seek this resource to guarantee rights. Then, the category “type of request” was intended to investigate which requests are directed to the Justice System. The “education network” category was intended to categorize whether requests refer to public municipal and state networks or private ones. Finally, the category “variation in the number of requests per year” had as main objective to locate the number of requests according to their object over the studied years.

The analysis of the material was linked to the literature on the subject, as well as to current legal frameworks on Special Education and the rights of people with disabilities. It also had a dialogue with documents related to the legal frameworks of Special Education and the performance of GEDUC regarding requests involving the provision of Special Education in the perspective of inclusive education. To this end, it considered the analysis of: a) policies, legislation and texts dealing with the right to education for all, discussing the role of the Public Ministry in this area; b) GEDUC documentation, since its creation, consisting of the mapping of requests received regarding the Special Education area, with a purpose of knowing: the agents of the representations; the request(s) made to the Public Ministry; the forwarding given from that receipt.

3 Results and discussion

It was observed that the average time for processing requests at GEDUC has been two and a half years. From the study of the procedures, it was found that such time was not related to the delay of the Public Ministry to start acting since the presentation of a complaint, but with the development of activities to monitor the situations. This means that, during these two and a half years, several interventions were carried out, such as requesting information from the parties involved in the alleged violation of rights, meetings with management professionals from the education networks involved, visits to educational units, hearings, public hearings, opening spaces for discussions, consulting researchers in the area of Special Education, among other activities.

The archived requests usually referred to the exhaustion of all requests made during the process at GEDUC, for example: the accessibility of the space with the execution of reforms and the allocation of supports to attend students in regular classes. It was also possible to investigate situations in which the archiving of a one-off procedure occurred due to the opening of another broader procedure, covering the entire education network, such as the opening of a Civil Inquiry (CI) designed to ascertain and guarantee, within the Municipal Education Secretariat, the architectural accessibility of all educational units. In addition, a Civil Inquiry was installed to verify the physical accessibility of all buildings on all campuses of the University of São Paulo (USP) and a Conduct Adjustment Term for the State Department of Education to present a physical accessibility schedule of all educational units.

As for the proponents of requests to the Public Ministry, it was apprehended that 64.4% are family members and students, 27% are State institutions, including, in this category, above all, the Public Ministry and the Ombudsman, from the carrying out of inspections in tutelary institutions and councils. Thus, the Public Ministry’s main interlocutor has been the family, with low representation of the students themselves, which corresponded to only two of the 105 requests from the group of family members and students.

The history of social movements representing people with disabilities can be divided into two distinct phases. Initially, the leadership of these movements was occupied by families and professionals, and then, in a second moment, counted on the direct participation of people with disabilities. However, the advance from the first to the second, in addition to being very recent, did not mean overcoming the initial moment (Maior, 2015). This aspect helps us to understand the incipient presence of social movements of people with disabilities who present requests to the Public Ministry.

Most of the requests analyzed referred to Early Childhood Education and Elementary Education, with few involving other stages of Education. In this sense, the information from the 2018 Census (Table 1) points to a progressive decrease in the number of enrollments throughout the schooling cycle of the target students of Special Education in the city of São Paulo.

Table 1 Number of enrollments of the municipality of São Paulo in the State and Municipal Network in 2018 in Special Education.

| Early Childhood Education | Elementary School | High School | On-campus Youth and Adult Education | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day care center | Pre-school | Early grades | Final grades | Elementary | High School | |||

| State | 0 | 0 | 4.163 | 4.201 | 5.234 | 4 | 426 | 14.028 |

| Municipal | 318 | 2.837 | 7.158 | 6.640 | 100 | 1.284 | 0 | 18.337 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira ([INEP], 2018).

Such a framework can guide two non-exclusive hypotheses, about the low number of requests to GEDUC in the final stages of schooling processes: the first would be that the number of requests is a direct reflection of the decrease in the number of students with disabilities in the High School, Youth and Adult Education, Vocational Education and Higher Education. The second refers to the lack of access of the young target students of Special Education to the Public Ministry. As for the second hypothesis, it is important to resume that the initial years of the schooling path are directed to childhood, while the final grades of Basic Education (High School and subsequent stages) are addressed to young people and adults.

The youth occupy a leading role in the organization of student movements to claim rights, as a moment of transition from the children’s world, immersed in the particularism of kinship groups, to the adult world and full citizenship (Groppo, 2007). Thus, young people are important agents in claiming their rights. It is understood that a study on the barriers to access of this group of young target students of Special Education to the Public Ministry and, more specifically, to GEDUC, is necessary, taking into account that the very ignorance of this place of destination of requests regarding the violation of educational rights can be configured as a barrier.

With regard to the low expressiveness of requests made by education workers, it is possible to infer their relationship with the suffering processes experienced by education professionals due to the subjects’ immersion in contexts marked by work overload, scarcity of training work spaces and exchanges between peers, low remuneration and consequent accumulation of jobs (Thiele & Ahlert, 2007). As a result of this scenario, the workers would experience loneliness in the execution of their work practices, disconnecting their daily activity from the importance of participation in spaces of social control and the contribution of necessary resources for the consolidation of the public policy to guarantee the right to education.

Regarding the educational network to which the requests refer, there is a prevalence of requests related to the state network, corresponding to 42.59% against 29.01% of the municipal network, 22.22% of the private network and 6.17% of schools of exclusive education. Despite the reading that the high number of requests related to the state network could be related to the greater volume of the network in the city of São Paulo, when comparing the information only about enrollment of the Special Education target population, it was possible to apprehend that the number is lower in the state network than in the municipal. Thus, there is an indication of greater difficulty in the educational processes of this public in educational units in the state network. However, the motivation for this prominent difficulty is an element that lacks deepening, indicating the need for studies on the organization of the state educational network in the state of São Paulo to serve the target population of Special Education.

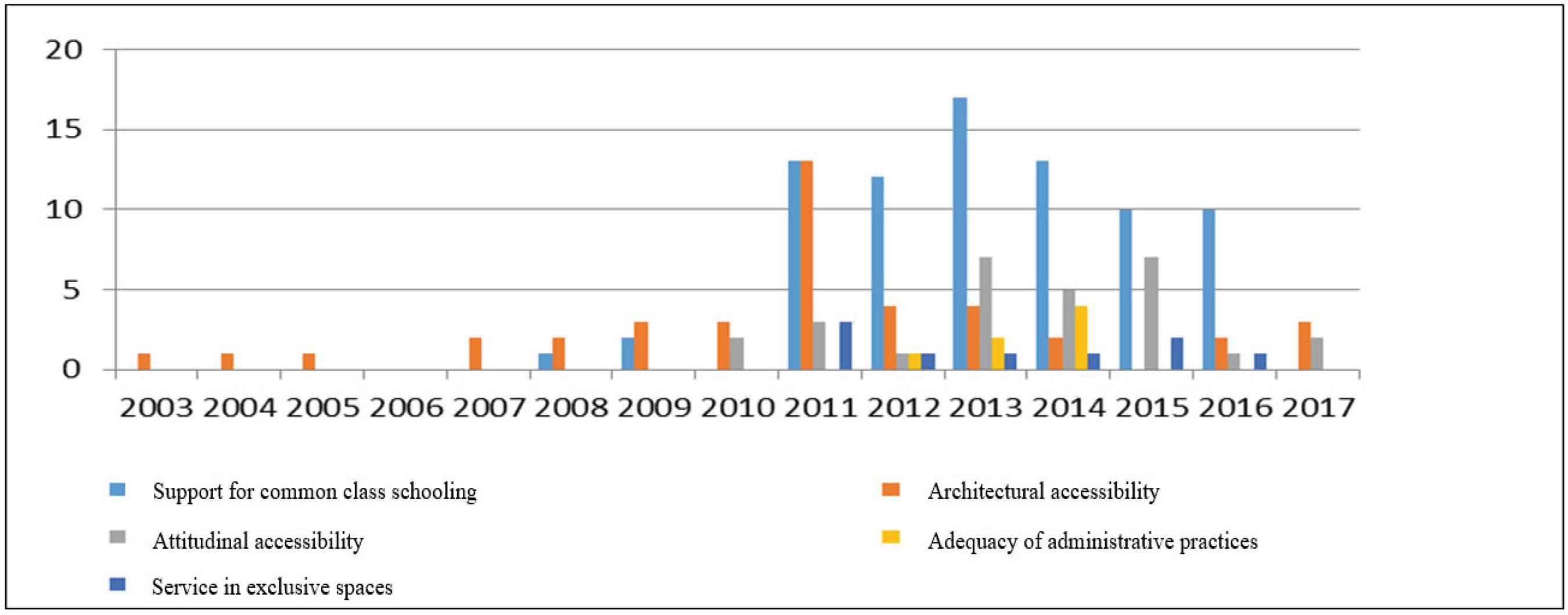

In the analysis of the number of requests per year of the research, a large concentration of requests received was noticed right after the creation of GEDUC (in 2011), when compared to the number of requests prior to the constitution of the Special Action Group, initially received by other Public Ministry prosecutors and later forwarded to GEDUC, as summarized in Figure 1.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1 Variation by type of requests to GEDUC between 2003 and 2017.

On the one hand, this result may be an indication that the configuration of a specialized space within an institution with the attribution of guaranteeing rights allows the population to address their requests related to the right to education by the target population of Special Education. On the other hand, the decrease in the number of requests over the years, in the studied period, may have a direct relationship with the way GEDUC has been working with issues involving the guarantee of the right to education of the Special Education target population, favoring the insertion of requests in procedures for monitoring an entire educational network (municipal and state) instead of introducing a new procedure for each request received. In addition, the procedures remain in progress for an average period of two and a half years, meaning that requests received in recent years should not appear in the survey, which took into account only archived procedures. Regarding the type of request addressed to GEDUC, the vast majority was related to accessibility and support for attending common classes of regular educational units, with only 5.5% requests relating to enrollment in exclusive educational spaces. Of these requests for assistance in common classes, 47.9% were related to support for the schooling process, followed by architectural accessibility with 25.2%, attitudinal accessibility with 17.2% and administrative practices with 4.3%.

Such results overturned the researcher’s initial hypothesis that the Public Ministry’s main object of action was the request for exclusive schools. As a worker in the field of education, attending spaces where, often, family members of people with disabilities, especially family members of students with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD), have manifested themselves publicly requesting - sometimes, demanding - exclusive schools for their children, the researcher inferred that requests to remove these children from regular education spaces are common. However, according to the results found, this request is not repeatedly addressed to GEDUC, and therefore to Public Ministry in the municipality of São Paulo. On the contrary, the research shows that the requests are almost always related to support for the school permanence of these children and adolescents.

Based on this complex scenario, in which combating violation of rights is closely related to inducing the Executive to build public policies to confront the ableism, the strategies and work tools used by GEDUC were analyzed and in dialogue with the professionals of the Psychosocial Technical Advisory Center. The analysis was based on the indication of the main agents involved in the performance of the Public Ministry during the course of a procedure. However, it is noteworthy that this study was only a cutoff of a whole research with a selection of specific categories, thus a series of other analyzes is still possible. The present research did not intend to exhaust the knowledge production that the reading of these procedures allows.

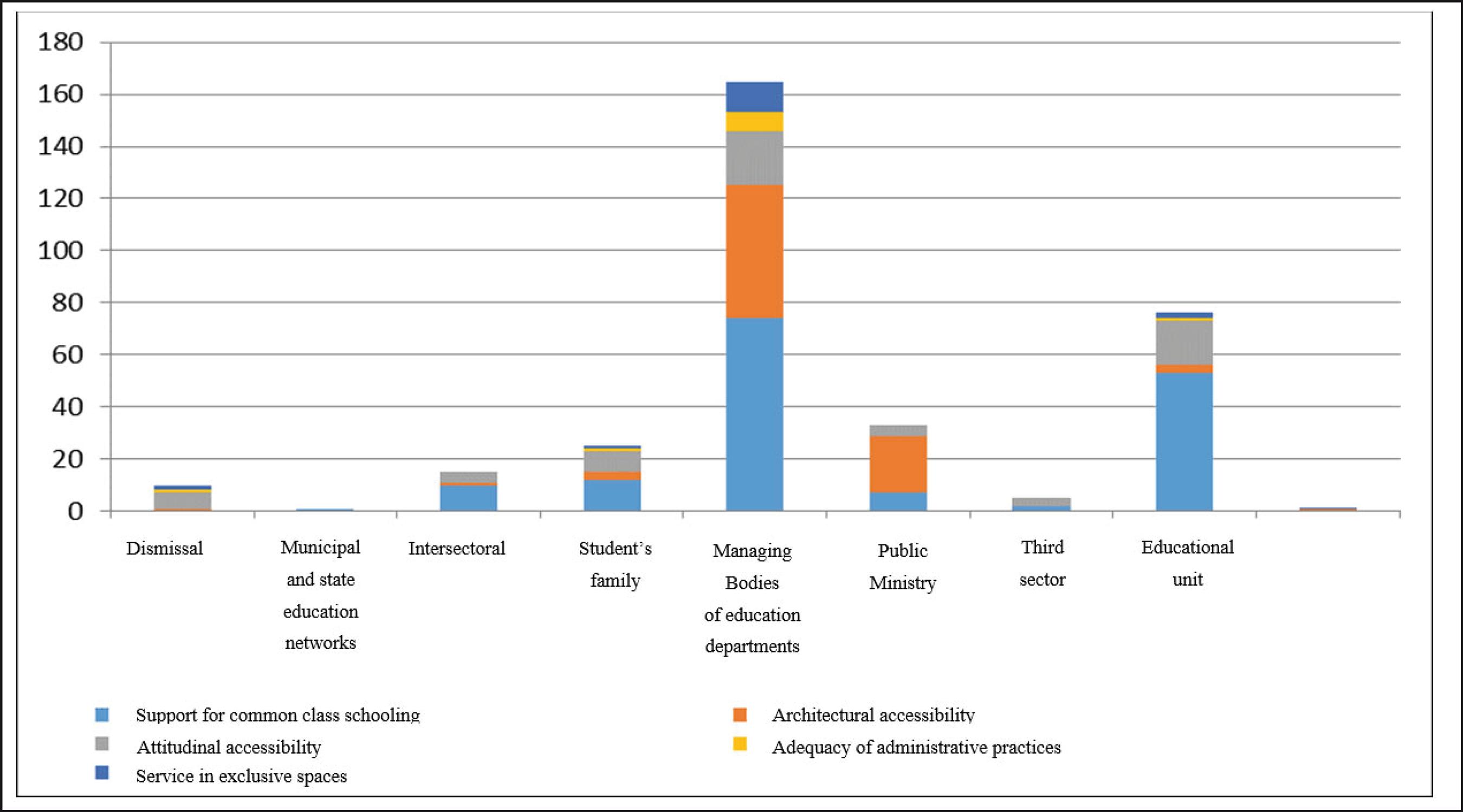

In order to explain how GEDUC deals with each of the situations, the following graph was elaborated (Figure 2) as a tool that condenses the two axes of analysis, correlating the effective articulations between the Public Ministry and the types of requests addressed.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2 Systematization of the Public Ministry’s actions by type of request.

The Figure shows what GEDUC’s operating strategies are in relation to the type of request received. We highlight the fact that the same procedure was inserted in more than one articulation category. Thus, in the face of a request received, GEDUC used the following strategies: rejection (when the request has already been met or in situations where the initial claim was not part of GEDUC’s set of duties); articulation of municipal and state networks (fostering the partnership between municipal and state networks to resolve requests); intersectoral articulation (actions in the articulation between different areas, such as health, social assistance and education); articulation involving the families of students; action directly involving the managing bodies of the Education Secretariats; performance involving other sectors of the Public Ministry; performance involving third sector institutions; direct action with the school units involved in the requests.

Through the analysis of the sectors involved in GEDUC’s activities, the preponderance of actions with the central management bodies of the Education Secretariats (municipal and state) as well as in the extrajudicial sphere is verified. The work with the management bodies of the Education Secretariats may be related to the fact that this group of actions has a primary function at a level of collective protection and not of individual rights.

In the case of the study of GEDUC’s specific actions in matters involving Special Education, it was apprehended that, upon receiving a request, GEDUC’s professionals initially listened to the proponent. The educational units were required to provide information about their organization in order to serve the target students of Special Education. The request involved the indication of the services and supports that comprised the Specialized Educational Service (SES), as well as the preparation of the SES plans.

Therefore, GEDUC’s intervention focused on elements that, according to the current PNEEPEI - National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education (2008), should already be present in the school scene. The strategies used also contemplated the involvement of the workers of the Teaching Supervisions to provide GEDUC with information about the supports offered to the educational units for the structuring of the SES offer. When the existence of this apparatus was not found in the educational units, management instances of the Secretariats were contacted, in order to elect strategies for inspection.

Finally, it was observed that the performance of GEDUC was aimed at guaranteeing an educational offer in an inclusive perspective to all target students of Special Education, in line with the set of norms and educational guidelines in force. The guarantee of an inclusive education is also guided by academic production in the area, which has demonstrated the importance of implementing the educational right for all. A survey conducted by Alana Institute in partnership with ABT Associates shows that:

There is clear and consistent evidence that inclusive educational environments can offer significant short- and long-term benefits to students with and without disabilities. A large number of surveys indicate that included students develop stronger reading and math skills, have higher attendance rates and are less likely to have behavioral problems. (Instituto Alana & ABT Associates, 2016, p. 2).

4 Conclusion

The starting point of this research was the absence of systematization studies and analysis of the performance of the Public Ministry regarding its role in guaranteeing the right to education for the target population of Special Education, after conducting a review of the literature on the subject. Therefore, this is the first work on the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo Acting Group with a specific function in the area of education, which allowed a greater concentration of information and, consequently, greater possibility of systematization and analysis. With the concentration of information, the elements gathered in this research brought relevant indications for the qualification of requests addressed to the Public Ministry, as well as the characterization of the requesting subjects, their main requests, the forwardings made.

GEDUC’s action presents indicative elements of the commitment to replace the demanded Public Ministry model, which responds to requests addressed to prosecutors in a bureaucratic manner and without the involvement of the social agents involved in the issue, for the resolute Public Ministry, that seeks to create spaces for social control in order to guide its performance in the defense of social rights, as pointed out by Goulart (2013). When working under the premise that knowledge of reality, through dialogue with the various social agents, allows the qualification of work aimed at guaranteeing rights, strategies oriented to induce policies and not arbitrary and divergent decisions from what is provided for in them are chosen. The action is no longer centered on punctual responses, aiming to respond to requests in an immediate and instrumental way, without problematizing their origins and meanings. On the contrary, it seeks the articulation of different social agents involved in guaranteeing the right to education by the target population of Special Education, producing institutional implications for the construction of joint solutions, based on the parameters established by public policy and Human Rights.

Thus, from the research, it is understood that directing the work of the Public Ministry towards the induction of public policies and the promotion of Human Rights necessarily implies the differentiation between complaint and demand. Starting from the analysis of the objects of the requests to GEDUC, it is apprehended that the proponents of the requests mostly complain about the absence of materials, specialized workers and structure, being the requests for schooling support in common classes of students in regular schools and accessibility the most frequent. The Freudian theory is then used to make an important distinction between a complaint and an underlying demand (Quinet, 2011). The complaint will be addressed to a specific object of satisfaction (in this case, the hiring of a professional or a structure adjustment), while the demand will refer to the existing content in addition to the one already formulated. The demand is only constituted in the encounter of the one who complains with the other to whom he/she directs the request, having as precedent the non-fulfillment of something previously offered. Transposing this differentiation to the researched context, it is possible to consider that what can be materialized as a request to the Public Ministry refers to resources, infrastructure and professionals, in other words, to what presents a concrete dimension: the ramp, the multifunctional resource room, a school support professional.

It is up to the Public Ministry to guarantee spaces for dialogue, so that it can build an understanding of what barriers are acting in preventing the right to education, in order to create mediation situations in which the different institutional agents can understand the meanings of the requests, reinterpreting them in the light of barriers and different perspectives on the phenomenon in question, not acting in an instrumental and immediate manner. To illustrate the reading of GEDUC’s action in transposing the complaint, the content of some of the analyzed procedures is presented. There are procedures for investigating the violation of rights based on the narrative of family members about the absence of school support professionals during the class period. After GEDUC’s contact with the school, responses were found from the professionals of the educational units, arguing that there is no direct and constant adult supervision as a strategy adopted aiming at the student’s autonomy. In these cases, the members of GEDUC played a mediation role, creating spaces for dialogue between the subjects involved in the situation, but not necessarily in direct response to the request made.

In other cases, also involving requests by school support professionals, actions were found with a different direction, involving charges to central bodies in the management of education networks regarding the hiring of more professionals. This direction often came from reports produced in meetings and/or visits in which the professionals from the educational units pointed out the existence of the school support professional as, in that case, a determining factor for the frequency of the student in the institution. Thus, an action that privileged only an instrumental and immediate response to the complaint made would disregard the need for dialogue to clarify the real demand, which necessarily involves dialogue and reformulation of the way of operating in educational spaces, incorporating contributions from family members, students, educators and Public Ministry. According to Chaui (1980):

There is, therefore, a discourse of power that pronounces on education defining its meaning, its purpose, form and content. Who, therefore, is excluded from the educational discourse? Precisely those who could speak of education as an experience that is of their own: teachers and students. (p. 27).

Instead of immediate responses, requiring the execution of the request by the represented parties, more time-consuming actions were found to promote dialogue on the problem presented. Therefore, there seems to be a predominance of the use of democratic and participatory strategies, involving different agents implicated in the process. As an example, we can cite the establishment of public policy monitoring procedures, in order to verify the organization of the special education modality in an inclusive perspective for the entire education network. In order to promote articulation with social movements, professionals and students, social listening and public hearings were held, with the elaboration of the GEDUC Action Program for the 2018-2020 biennium, with the presentation of six priority executive programs in the group’s action, among them, one related to Special Education, with the objective of guaranteeing the offer of a quality special inclusive education (São Paulo, 2018, p. 95).

Based on the above, it is possible to affirm that GEDUC is configured as an advance achieved in the promotion and expansion of the qualified performance of the Public Ministry in the induction of public policies, since the knowledge of the field of action allowed the formulation of strategies based on the achievements arising from the struggles undertaken by social movements and based on the existence of an actual normative body. It is noticed that the advance of the Public Ministry’s performance from the level of the request to the level of the underlying demand is possible, above all, through the construction of a closer work between the Public Ministry and the agents involved in the guarantee of rights.

However, there are some considerations, with the intention of stirring up the debate on important elements and which, if faced, could result in the further qualification of GEDUC and, consequently, of the Public Ministry, in the induction of public policies for this educational modality. GEDUC’s work is aimed at guaranteeing the right to education, according to the Normative Act that constitutes it (Normative Act no. 700, of May 31, 2011). In this sense, few activities were found involving the promotion of intersectoral articulation, with managers of health, assistance, urban mobility, culture policies, among others. The fragmentation of action with policies involving social rights is a characteristic of the Public Ministry’s own organization, since the prosecutors act separately with issues of health, childhood and youth, human rights, housing and urbanism, public heritage, as previously pointed out in the first chapter of this research, in which an exposition of the institutional organization of the body was made.

With regard specifically to the subject of this research, the guarantee of the enjoyment of the rights of people with disabilities needs to move towards the construction of action strategies among the various prosecutors of the Public Ministry, as access to health promotion spaces, assistance programs, mobility and urban locomotion, for example, is a fundamental element for the realization of the right to education.

Another aspect understood as a priority for the performance of the Public Ministry refers to the realization of the offer of spaces for social control and claiming rights from the education services, to be occupied by the target population of Special Education, and not just by family members. The advance in the organization of an education policy based on the social model of disability must guarantee autonomy in order to discuss, evaluate and claim resources to guarantee the right to education. This includes, for example, studies and discussions on the participation of the target students of Special Education in instances of schools democratic management, as a student union, among other possible spaces.

Silva (2018) affirms the need to consider that, in the matter of public policies with a focus on extra-procedural action, the actions of the Public Ministry members should not focus on individual and isolated desires, in order not to run the risk of a disarticulated, or even divergent, action, which would be extremely detrimental to the guarantee of social rights. The author also states that the responsibility for the transformation of the Brazilian reality, as stated in the 1988 Federal Constitution, cannot be carried out by privileging a tutored action by society, with actions for or on behalf of, but, rather, with the society and in the perspective of strengthening citizenship, hence the importance of the Public Ministry intensifying its set of dialogue actions directly with people with disabilities.

Considering the very low enrollment of the target population of Special Education in Secondary Education, Youth and Adult Education, Vocational Education and Higher Education, the need to build work processes that act directly on the serious problem of discontinuity of schooling in the final grades of Elementary Education is highlighted.

The need for the Public Ministry to act in the face of demands for the organization of supports for accessibility in the various spheres involved in school life is explained, implying the assumption of the premise that everyone has the right to education, based on inclusive processes (Decree no. 6,949, of July 9, 2009), requiring collective mobilization to face the barriers acting to prevent or hinder the enjoyment of this right.

Finally, the importance of conducting short, medium and long-term research on the impacts produced by GEDUC’s performance in the search for the solution of issues involving violations of the right to education is emphasized. This work had as an outline the analysis of the performance of one of the agencies that operate the Justice System, however, it is necessary to offer spaces to those directly involved in the Public Ministry interventions to analyze, from their perspective, the effects of the actions produced by the Public Ministry. It is also suggested to carry out studies in order to monitor how those who experience situations of violations of the right to education have perceived the performance of the Public Ministry.

5Those that do not belong to a single individual, serving a group of people or the community affected by a given situation.

6Translation: The purpose, in principle, was not to create new rights, but to ensure the use of the principle of non-discrimination in each of the rights, so that they can be exercised on equal opportunities by people with disabilities. For this, it was necessary to identify, when regulating each right, what were the extra needs that should be guaranteed, in order to adapt these rights to the specific context of the disability (Palacios, 2008, p. 269).

7The full text of the material studied and the categorization process are available in Pedott (2019).

REFERENCES

Arruda, I. C. de, & Santos, R. F. M. (2012). Serviço Social no Ministério público: consolidação de uma nova proposta de trabalho - a experiência de trabalho do NAT - Núcleo de Assessoria Técnica Psicossocial. Artigo apresentado no 4º Encontro Nacional do Ministério Público, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [ Links ]

Ato Normativo nº 672, de 21 de dezembro de 2010. Cria o Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação (GEDUC) no âmbito do Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo e dá outras providências. São Paulo, Subprocuradoria-Geral de Justiça Jurídica. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://biblioteca.mpsp.mp.br/PHL_IMG/Atos/672.pdf [ Links ]

Ato Normativo nº 700, de 31 de maio de 2011. Altera as disposições do Ato Normativo nº 672/2010-PGJCPJ, de 21 de dezembro de 2010, que instituiu o Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação (GEDUC) no âmbito do Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2020 de http://biblioteca.mpsp.mp.br/PHL_IMG/Atos/700.pdf [ Links ]

Ato Normativo nº 724, de 13 de janeiro de 2012. Institui o Núcleo de Assessoria Técnica Psicossocial. Procuradoria Geral de Justiça. São Paulo, 2012. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://biblioteca.mpsp.mp.br/PHL_IMG/Atos/724.pdf [ Links ]

Chaui, M. (1980). Ideologia e Educação. Educação e Sociedade, 2(5), 245-257. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988 (1988). Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm [ Links ]

Decreto nº 6.949, de 25 de agosto de 2009. Promulga a Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência e seu Protocolo Facultativo, assinados em Nova York, em 30 de março de 2007. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/decreto/d6949.htm [ Links ]

Goulart, M. P. (2013). Elementos para uma teoria geral do Ministério Público. Belo Horizonte: Arraes Editores. [ Links ]

Groppo, L. A. (2000). Juventude: ensaios sobre sociologia e história das juventudes modernas. Rio de Janeiro: DIFEL. [ Links ]

Instituto Alana, & ABT Associates (2016). Os benefícios da educação inclusiva para estudantes com e sem deficiência. São Paulo. Recuperado em 20 de janeiro de 2020 de https://alana.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Os_Beneficios_da_Ed_Inclusiva_final.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (2018). Resultados finais do Censo escolar (redes estaduais e municipais). Recuperado em 22 de maio de 2019 de http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/resultados-e-resumos [ Links ]

Kassar, M. (2011). Percursos da constituição de uma política brasileira de educação especial inclusiva. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 17, 41-58. [ Links ]

Lei nº 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015. Institui a Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13146.htm [ Links ]

Lei nº 8.625, de 12 de fevereiro de 1993. Institui a Lei Orgânica Nacional do Ministério Público, dispõe sobre normas gerais para a organização do Ministério Público dos Estados e dá outras providências. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8625.htm [ Links ]

Maior, I. (2015). Breve trajetória histórica do movimento da pessoa com deficiência. Secretaria do Estado dos Direitos Humanos da Pessoa com Deficiência, São Paulo. Recuperado em 16 de junho de 2019 de http://violenciaedeficiencia.sedpcd.sp.gov.br/pdf/textosApoio/Texto2.pdf [ Links ]

Palacios, A. (2008). El modelo social de discapacidad: orígenes, caracterización y plasmación en la Convención internacional sobre los derechos de las personas con discapacidad. Madrid: Cermi, 2008. [ Links ]

Pedott, L. G. O. (2019). Possibilidades de construção de demandas sociais e indução de políticas públicas: análise de solicitações ao Ministério Público relativas ao direito das pessoas com deficiência à educação. Dissertação de Mestrado em Educação, Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva (2008). Recuperado em 10 de maio de 2019 de http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=16690-politica-nacional-de-educacao-especial-na-perspectiva-da-educacao-inclusiva-05122014&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

Quinet, A. (2011). A descoberta do inconsciente: do desejo ao sintoma. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar. [ Links ]

São Paulo (2018). Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo. Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação. Programa de Atuação 2018-2020. São Paulo. Recuperado em 5 de maio de 2019 em: http://www.mpsp.mp.br/portal/page/portal/GEDUC/PROGRAMA%20DE%20ATUA%C3%87%C3%83O%20GEDUC%202018%202020.pdf [ Links ]

Silva, C. A. da., Silva, J. P. F., & Pedott, L. G. O. (2017). A atuação do Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo na defesa da política de educação especial inclusiva: a construção do trabalho interdisciplinar entre Direito, Psicologia e Serviço Social no Grupo de Atuação Especial de Educação - GEDUC. In M. C. M. Kupfer, M. H. S. Patto, & R. Voltolini. (Eds.). Práticas inclusivas em escolas transformadoras: acolhendo o aluno-sujeito (pp. 249-276). São Paulo: Escuta. [ Links ]

Silva, J. P. F. (2018). Ministério Público e a defesa do direito à educação: subsídios teóricos e práticos para o necessário aperfeiçoamento institucional. Dissertação de Mestrado em Direito do Estado, Faculdade de Direito, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Thiele, M. E. B., & Ahlert, A. (2007). Condições de trabalho docente: um olhar na perspectiva do acolhimento. In Secretaria de Estado da Educação do Paraná. Superintendência de Educação. O professor PDE e os desafios da escola pública paranaense. Curitiba: SEED/PR, 1. Recuperado em 2 de julho de 2019 de http://www.diaadiaeducacao.pr.gov.br/portals/cadernospde/pdebusca/producoes_pde/2007_unioeste_ped_artigo_marisa_elizabetha_boll_thiele.pdf [ Links ]

Thiollent, M. (1986). Metodologia da pesquisa-ação. São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Received: September 30, 2019; Revised: February 04, 2020; Accepted: February 22, 2020

texto em

texto em