1 Introduction

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) establishes in its policies to guarantee Physical Education of quality, that schools should focus on inclusive methodologies aimed at promoting and raising awareness of people with disabilities by promoting values during Physical Education class, and the values should be regulated for promotion among students, parents, and community members (McLennan & Thompson, 2015). The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in 2012, established a correlation between disability and child development in early childhood (covering prenatal age, up to eight years old), which is crucial for an optimal well-being and growth, being a key influence on the subsequent life cycle of an individual.

Hearing impairment is a total or partial lack of audio perception in each ear and is part of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, 2013). People with hearing impairment have damage in the vestibular system, either by a disease or a congenital disorder, which represents difficulties in learning their own language, continuing to study, participating in activities normal for their age, and from daily life (Franco & Panhoca, 2008; Manente, Rodrigues, & Palamin 2007). Meta-analysis shows that a person with hearing disabilities and poor development of motor skills has also poor language development and cognitive skills (Kitterick, Lucas, & Smith, 2015; Wang et al., 2019). Due to the damage to the vestibular system of people with hearing impairment, it has been observed that their coordination abilities show deficiencies in the dynamic and static balance (Suarez et al., 2007), as well as difficulties in learning motor skills associated with rhythm, synchronization, adaptation, spacetime recognition, laterality, orientation, and reaction speed compared to the general population (Jafarnezhadgero, Majlesi, & Azadian, 2017; Rajendran & Roy, 2011; Walicka-Cupryś et al., 2014).

For a special education of quality in students with disabilities, Physical Education teachers require adequate initial and permanent training (González López & Macías García, 2018; Rubinstein & Franco, 2020). Research shows that learning Physical Education requires specific methods according to the type of disability and support for the student to improve their learning (Cawthon, 2009; Hintermair, 2011). In the case of hearing impairment, pedagogical strategies are required to promote development of motor skills and student participation in physical activity, adapting communication and didactic tools that facilitate the curriculum in the teaching and learning process (Barboza, Ramos, Abreu, & Castro, 2019; Fiorini & Manzini, 2018; Kurkova, Scheetz, & Stelzer, 2010).

Studies that evaluate the development of motor skills variable in students using the Battelle Developmental Inventory (Newborg, Stock, & Wnek, 1996) as an instrument of diagnostic aid correlate that the students with development of motor skills suitable for their age present a greater cognitive development and language of the same level according to their age (Campo Ternera, 2010). However, studies that compare low development of motor skills score through the Battelle inventory of children with disabilities resulted in significantly lower values than of clinically healthy children (Moraleda-Barreno, Romero-López, & Cayetano-Menéndez, 2011; Moreno-Villagómez et al., 2014; Sanz Lopez, Guijarro Granados, & Sanchez Vazquez, 2007). When reviewing the state of the art research in people with disabilities, it has been showed that physical activity on a regular basis contributes to an improvement in coordination of motor skills (Pulzi & Rodrigues, 2015). A quasi-experimental study in adolescents with hearing impairment improves coordination motor skills when practicing physical activity in the dance modality (Montezuma, Rocha, Busto, & Fujisawa, 2011). Nonetheless, systematic reviews report that a small proportion of children and young people with hearing impairment (28%) comply with the amount recommended by the WHO (Chunxiao, Justin, & Lifang, 2019; Lobenius-Palmér, Sjöqvist, Hurtig-Wennlöf, & Lundqvist, 2018). Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effect of a program with pedagogical strategies for gross and fine motor skill learning through Physical Education in students with hearing impairment.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The research was registered and approved in the Coordination of Graduate Studies and Research of the Autonomous University of Baja California with the SICASPI protocol n. 149/1835 called Evaluación de un programa de desarrollo motor en escolares con capacidades diferentes (Evaluation of the development of motor skills program in students with different abilities), being performed between August 2018 and July 2019. To perform the intervention, approval from the principals, teachers and parents of a center than offers Basic Education to people with diagnosed hearing impairment, taking into account the ICF of disability and health established by the WHO (2013). The ethical principles of research involving human subjects of the declaration of Helsinki were followed, taking into account the participation of children and young people (Rupali, 2005), under a quasi-experimental methodological design, with non-probability sampling for convenience (Thomas, Nelson, & Silverman, 2015).

2.2 Procedures

The Physical Education program focused on didactic and pedagogical strategies with tools and materials that promoted play through movement, addressing a series of tasks that emphasized coordination skills, primarily fine motor skills, gross motor skills, dynamic balance and static balance, following the guidelines for the educational care of deaf students who attend Basic Education established in Mexico by the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP, 2012); as well as the recommendations established to teach Physical Education to students with hearing impairment (Barboza et al., 2019; Fiorini & Manzini, 2018; Kurkova, Scheetz, & Stelzer, 2010).

In total, 15 students registered in the educational institution participated, with an average age of 7.7 ± .3 years old, (men n = 9 and women n = 6). The program was conducted in the facilities of the school center. The sessions were directed and supervised by a professional in Physical Culture trained in communicating with the Mexican Sign Language. Sessions were performed for 20 weeks of intervention, adapting 2 sessions each week, corresponding to a total of 40 Physical Education classes, which lasted 50 minutes, and were divided into 5 minutes of warm-up, 40 minutes of core phase and 5 minutes of rest. During the program, communication with students using the Mexican Sign Language was established to provide feedback and establish clear and simple instructions (Serafín De Fleischmann & González Pérez, 2011). The exclusion criteria was: presence of some type of acute or chronic pathology that could hinder physical activity. The inclusion criteria was: to attend to 90% of the program’s sessions, voluntary participation with the consent of parents or guardians, being a registered student (minimum 3 months of enrollment), not having systematically participated in a physical exercise program 3 months before of the intervention, and to perform daily life activities without the help of third parties.

2.3 Instruments

The Battelle® Developmental Inventory was utilized, in order to assess the gross and fine motor skills (Newborg, Stock, & Wnek, 1996), which is used to evaluate the fundamental skills of development in children from birth to eight years of age. Its application is individual and typified. It is an objective of the inventory, during its data collection procedures, the usage of observation and a structured examination. The items are presented in a standardized format that specifies the conduct to be evaluated, the necessary materials, administration procedures, and criteria for scoring responses. Its application is made up of 341 items for the total age range for which it is intended. It examines the areas of personal/social, adaptive, motor skills and communication development. For the purposes of the research, the motor skills area (82 items) consisting of 5 sub-areas was determined.

Muscle Control: It evaluates gross motor development and the students’ ability to establish and maintain control, mainly over the muscles used to sit, stand, pass objects from one hand to the other, and perform similar tasks (in the present research this variable will be ruled out due to the fact that it does not match the age of the sample).

Body Coordination: Evaluates aspects of gross motor skill development and the students’ ability to use the muscular system and to establish greater body control and coordination (e.g. changing body position, rolling on the ground, kicking, throwing and picking up objects, jumping, and doing push-ups).

Locomotion: Evaluates aspects of gross motor skill development and the students’ ability to use the muscular system in an integrated manner in order to move from one place to another (e.g. Crawling with the body touching the ground, crawling on knees, walking, running, jumping, or going up and down stairs), which together give the total score of gross motor skill.

Fine Motor Skill: Evaluates the development of the students’ muscular control and coordination, specifically of the muscles of the arms and hands that allow to perform increasingly complex tasks such as picking and dropping objects, opening and closing doors and drawers, stringing beads, turning pages, cutting, folding paper and using a pencil properly.

Perceptual Motor Skills: Evaluates aspects of fine motor skill development and the students’ ability to integrate muscular coordination and perceptual motor skills in concrete activities, such as: building towers, placing rings on a pole, copying circles and squares, drawing and writing, which together give the total score of fine motor skills.

The test was performed in between one hour to one hour and thirty minutes. In order to record the values in the items when evaluating, 0 was taken as never, 1 as sometimes and 2 always, making a sum that provides a total score whose results are compared with the summary table of scores and inventory profile, thus establishing the motor skill age in months, equivalent to the 82 items in the 5 sub areas, classified as: 1. High: Higher than expected for their age, 2. Normal: According to the normative patterns of age, and 3. Low: Below what was expected for its age.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, New York, USA), calculating the descriptive values of the variables and the percentage changes (Δ%) ([(Mediapost-Mediapre)/Mediapre] x 100 (Weir & Vincent, 2020). To verify the normality of the groups and homogeneity of the variance of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized due to the smaller number of 30 evaluations in the participants, presenting a degree of significance of P-Value ≥ 0.05. Taking into account the methodology utilized in the research, an alternative and null hypothesis test was established, for its verification, the students’ t-test was utilized for related samples in order to calculate the equality of the variance, determining a level of α≤ 0.05 , that is, 5% as a percentage of error of the statistical test.

3 Results

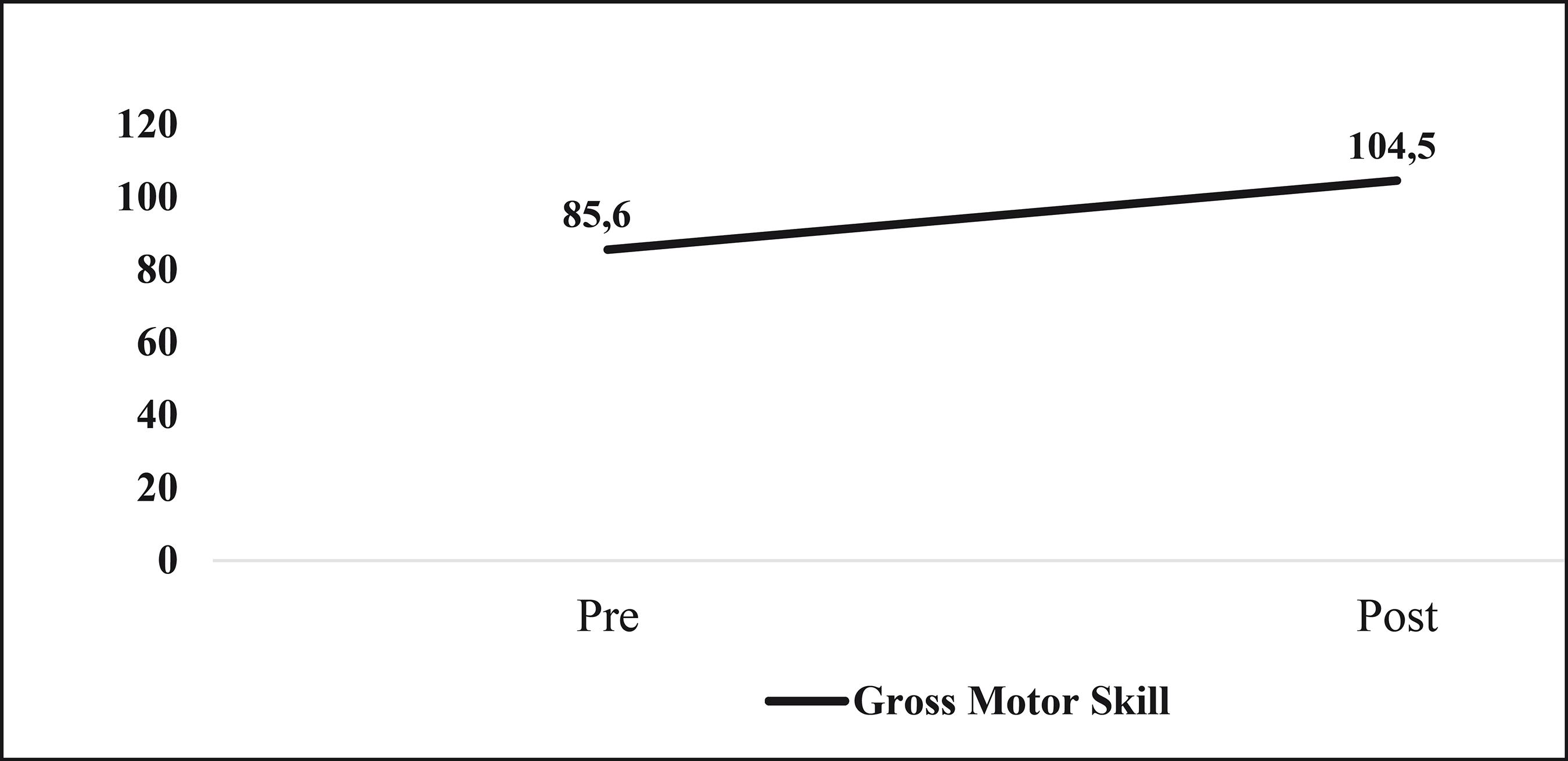

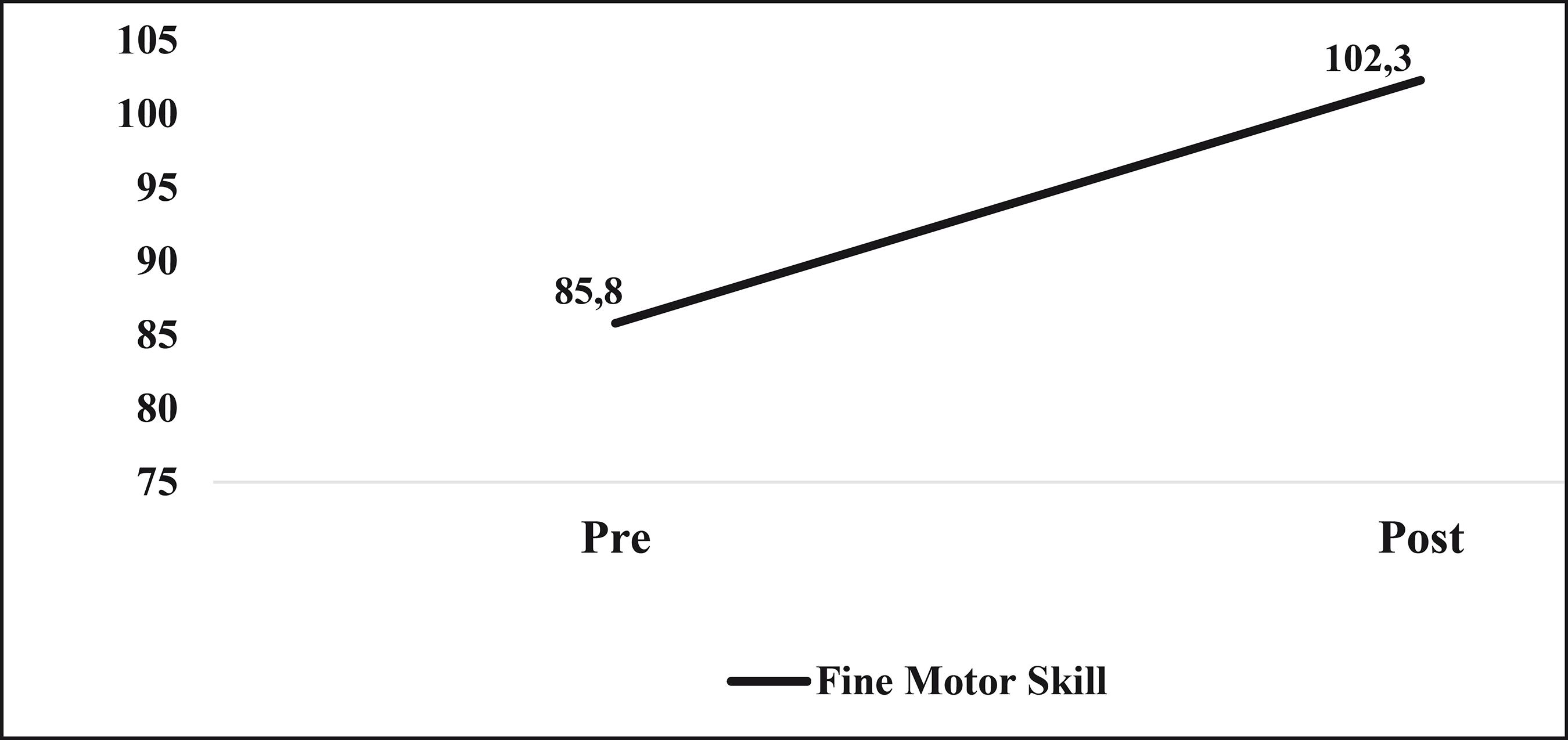

The results of inferential statistics through the students’ t-test statistical analysis for related samples, reported significant differences in the gross motor skill score (p = 0.001) and fine motor skill score (p = 0.001), Graph 1 and 2 respectively. The percentage change values (Δ%) for the initial and final study [(Mediapost - Mediapre) / Mediapre] x 100; were of 21.1 Δ% for gross motor skill and of 19.2 Δ% for fine motor skill.

Table 1 This table shows the descriptive statistics of the variables studied by the Batelle® developmental inventory (N = 15).

| Variables | Mean and Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Body Coordination: | 89.7±9.3 | 112.2±6.3 |

| Locomotion: | 81.6±9.1 | 96.9±7.3 |

| Gross Motor Skill | 85.6±8.1 | 104.5±6.7 |

| Fine Motor Skill | 82.09±6.2 | 97.9±5.2 |

| Perceptual Motor Skills | 89.7±9.7 | 106.8±11 |

| Total Fine Motor Skill | 85.8±7.3 | 102.3±7.2 |

Source: Elaborated by the author.

Note: The subjects' reported values are the mean and standard deviation (±) of the typical score obtained from students with hearing impairment using tests from the Batelle® Developmental Inventory (Newborg, Stock, & Wnek, 1996).

Source: Elaborated by the author

Note: Calculation of the variance of the variable of Gross Motor Skill by means of the students’ t-test of related samples (p = .001), evaluated before and after the intervention with the Battelle® Developmental Inventory (n = 15) (Newborg, Stock, & Wnek, 1996).

Figure 1 Changes in the typical score in the Gross Motor Skill variable (n = 15).

Source: Elaborated by the author.

Note: Calculation of the variance of the variable of Total Fine Motor Skill by means of the students’ t-test of related samples (p = .001), evaluated before and after the intervention with the Battelle® Developmental Inventory (n = 15) (Newborg, Stock, & Wnek, 1996).

Figure 2 Changes in the typical score in the Total Fine Motor Skill variable (n = 15).

4 Discussion

The main result of this research was that participation for 20 weeks in 40 Physical Education classes significantly improved fine and gross motor skill coordination in students with hearing impairment diagnosed according to the ICF of disability and health established by the WHO (2013).

Although different assessment instruments were utilized to assess motor coordination, the results of this research is consistent with research on people with disabilities who participated in physical activity in the dance modality (Montezuma et al., 2011).

Regarding the motor skill age reported by the Battelle Developmental Inventory before starting the program, the values were of 77 months (equivalent to 6.5 years old) ending after participation in the program with a motor skill age of 86 months (equivalent to 7.1 years old), representing a percentage change (Δ%) of 9.2. Which is positive due to the fact that when comparing our results with research that used the Battelle Developmental Inventory as an evaluation instrument, a lower motor skill pattern is reported in children with different disabilities than clinically healthy children (Moraleda-Barreno, RomeroLópez, & Cayetano-Menéndez, 2011; Moreno-Villagómez et al., 2014; Sanz Lopez, Guijarro Granados, & Sanchez Vazquez, 2007).

A comparative reference with an educational intervention design that evaluated motor coordination in children with disabilities using the Battelle developmental inventory applied a 10-week psychomotor program to children with disabilities diagnosed with Down Syndrome, delayed maturation in developmental, and autism spectrum disorder showed significant improvements, but lower values than this study (Rodríguez et al., 2017).

Motor skills tests for people with disabilities require specificity due to the characteristics of people and the type of disability (Hernández Nieves & Sáez-Gallego, 2014). The Battelle Developmental Inventory is inexpensive, easy to apply, and provides information related to motor coordination that can help us diagnose children with movement difficulties, as well as to design activities appropriate to their condition, and after being used in people with disabilities, it is reported as a valid and reliable instrument (Batya, Gattamorta, & Penfield, 2010).

Therefore, within the context of Physical Education, it has been widely recommended that teachers have competencies in students’ evaluation based on the curriculum (SEP, 2012). In this research, didactic strategies and pedagogical elements focused on motor coordination were emphasized, taking into consideration students’ characteristics with communication using Sign Language, and successful teaching practices reported in physical education studies in students with hearing impairment (Barboza et al., 2019; Ochoa-Martínez et al., 2018; Ochoa-Martínez et al., 2019), and at the same time being consistent with the policies established by UNESCO, which mentions that to guarantee Physical Education of quality schools must focus on inclusive methodologies (McLennan & Thompson, 2015). We added the discussion segment, which does present limitations, since we lacked a control group, we did not divide the subjects of the study by gender, and nor it was a research with non-probability sampling to extrapolate the results. However, it is expressed that the percentage of people with this type of disability is little compared with the total population; in the same way, there are few schools specialized in educational care for people with hearing impairment.

5 Conclusions

In this research, significant differences were found in gross and fine motor coordination in students with hearing impairment when participating in a five-month physical education program. Consequently, in the future, it would be important to perform a greater number of studies that clarify the effects of different variables as age, gender, family and school context on motor coordination in children with hearing impairment. This study is a reference that help in the teaching and learning process in order to develop educational interventions to improve coordination skills in children with disabilities but mainly to expand the information for Health and Physical Education professionals who work around people with hearing impairment, so they understand pedagogical and curricular processes in optimal manner.

![Transtorno do Espectro Autista e Práticas Educativas na Educação Profissional[1]](/img/es/prev.gif)