Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

Print version ISSN 1413-6538On-line version ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.4 Marília Oct./Dec 2020 Epub Dec 09, 2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-54702020v26e0189

Research Report

Bidirectional Naming in Children with Autism: Effects of Stimulus Pairing Observation Procedure and Multiple Exemplar Instruction2

3Master’s in Behavior Theory and Research. Federal University of Pará. Belém/Pará/Brazil. E-mail: juliana.l.lobato@hotmail.com.

4PhD in Behavioral Sciences from the University of Guadalajara (Mexico). Full Professor at the Federal University of Pará and Researcher at the National Institute of Science and Technology on Behavior, Cognition and Teaching (ECCE). Belém/Pará/Brazil. E-mail: carlosouz@gmail.com.

This study compared the efficiency of Multiple Exemplar Instruction (MEI) and Stimulus Pairing Observation Procedure (SPOP) for establishing bidirectional naming (BiN) in four children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. A multiple probe design was used between pairs of participants. One participant showed emergence of complete BiN after having undergone the two experimental treatments (first SPOP, then MEI). Two participants demonstrated emergence of the listener component after undergoing SPOP treatment. During the final naming test, two participants demonstrated emergence only for the BiN listener component, and one participant showed an increase in both components in relation to the baseline. The efficiency of treatments in isolation, when presented in sequence, is discussed, in addition to the importance of using reinforcing stimuli in the BiN acquisition process.

KEYWORDS: Bidirectional naming; Multiple exemplar instruction; Stimulus pairing observation procedure; Autism Spectrum Disorder

Este estudo comparou a eficiência dos procedimentos de Instrução com Múltiplos Exemplares (MEI) e de Observação de Pareamento de Estímulos (SPOP) para estabelecer nomeação bidirecional (BiN) em quatro crianças com Transtorno do Espectro do Autismo. Foi utilizado um delineamento de sondas múltiplas entre pares de participantes. Um participante demonstrou emergência de BiN completa, após passar pelos dois tratamentos experimentais (primeiro SPOP, depois o MEI). Dois participantes demonstraram emergência somente do componente de ouvinte, após o SPOP. No teste final de nomeação, dois participantes demonstraram emergência somente do componente de ouvinte da BiN, e um participante apresentou aumento nos dois componentes em relação à linha de base. Discute-se a eficiência dos tratamentos de maneira isolada, quando apresentados em sequência, além da importância do uso de estímulos reforçadores no processo de aquisição da BiN.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Nomeação bidirecional; Instrução com múltiplos exemplares; Procedimento de observação de pareamento de estímulos; Transtorno do Espectro Autista

1 Introduction

The development of basic listening and speaking skills is critical for the individual to gain independence in his/her interactions with the world, since these are crucial for the acquisition of more complex repertoires, such as social skills, reading with understanding and problem solving (Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009). The integration of the skills of speaker and listener results in a higher-order operant called “naming” (Horne & Lowe, 1996), more recently characterized as bidirectional naming - BiN (Miguel, 2016). According to Horne and Lowe (1996), BiN is a behavioral relationship that combines the behaviors of speaker and listener in the same individual, so that the presence of one presupposes the presence of the other. This implies that, when acquiring a new listener response through direct training, the individual simultaneously acquires the tact response (verbal operant controlled by a non-verbal antecedent and maintained by social reinforcement - Skinner, 1992) in relation to the same stimulus, and vice versa.

According to Horne and Lowe (1996), the acquisition of BiN takes place from the child’s daily interactions with their caregivers and other people in his/her environment, in which the child initially learns, independently of each other, listener repertoires, echoic (verbal operant controlled by verbal antecedent, with point-to-point correspondence between antecedent and response, both in the vocal modality - Skinner, 1992) and tact. When these three repertoires are integrated, we have the emergence of BiN as a higher order operator. Based on this, according to Horne and Lowe (1996), contextual tips provided by caregivers, such as pointing at an object or speaking its name in the presence of it, will be sufficient to evoke all verbal components of BiN.

Greer and Ross (2008) called this phenomenon “full naming” when the individual is able to learn pure tact (with a non-verbal stimulus as background) or impure tact (with verbal and non-verbal stimuli as a background - Skinner, 1992) and listener responses after just watching another person groping a stimulus in its presence, without the need for direct training or reinforcement of these responses, allowing the acquisition of verbal repertoires incidentally in the natural environment (Greer & Longano, 2010; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009).

However, experiences in a natural environment may not be sufficient for the development of verbal repertoires, including BiN, in people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and other developmental disorders, requiring more structured teaching procedures (Olaff, Ona, & Holth, 2017; Smith, 2001). Greer and collaborators developed a procedure for establishing BiN in people who do not develop it naturally: the Multiple Exemplar Instruction (MEI) procedure. MEI implies “putting responses [...] initially independent under joint control of stimuli. This is done by rotating different responses to the same stimulus [...] so that students acquire the ability to learn multiple responses from the instruction of just one [...]” (Greer & Ross, 2008, p. 296).

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of MEI to induce BiN in children with typical development (Gilic & Greer, 2011) and atypical development (Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Greer, Stolfi, Chavez-Brown, & Rivera-Valdes, 2005; Greer, Stolfi, & Pistoljevic, 2007; Hawkins, Kingsdorf, Charnock, Szabo, & Gautreaux, 2009; Olaff, Ona, & Holth, 2017; Santos & Souza, 2016). These studies have shown that the MEI procedure has been effective in producing the emergence of BiN in most participants after one to three exposures to MEI training.

Although, in general, MEI proves to be effective in establishing the listener repertoires, tact and BiN, it is characterized by being a procedure that requires a long teaching process. In the search for more efficient procedures that are closer to the natural conditions of language acquisition, in recent years, some researchers have been evaluating the effectiveness of the Stimuli Pairing Observation Procedure (SPOP) to induce listener repertoires, tact and BiN, in people with typical development (Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2015; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Huffman, 2012) and atypical development (Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Vallinger-Brown & Rosales, 2014). SPOP consists of the pairing of two stimuli, without any response being required from the individual, in addition to the observation of this pairing, with subsequent evaluation of the emergence of relationships between these stimuli. For example, a visual stimulus (object or picture) is named (auditory stimulus) a few times (pairings) in front of an individual, and then it is assessed whether the individual has learned tact and listener responses to that object-picture (Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Huffman, 2012).

In a study carried out with four children and adolescents diagnosed with ASD, Carnerero and Pérez-González (2014) evaluated whether responses of tact and selection of pictures would emerge after the pairing observation procedure of the picture with its name and, in addition, tested whether BiN could be induced in children who did not present it, through SPOP. All participants demonstrated emergence of tact repertoires and picture selection after being exposed to pairing cycles and touch probes, indicating that SPOP was effective in producing BiN repertoire in people with autism.

Byrne, Rehfeldt and Aguirre (2014) also conducted a study to evaluate the effectiveness of the SPOP procedure in the emergence of tact and listener responses for children with ASD. The results showed that, although multiple exposures to SPOP sessions produced an increase in the tact and listener responses of the three participants, only one participant reached the learning criterion for tact and listener with the original set of stimuli. This result suggested that SPOP might not be efficient in producing the two components of BiN.

One aspect that deserves to be highlighted in the studies conducted by Carnerero and Pérez-González (2014) and Byrne, Rehfeldt and Aguirre (2014) is the participants’ initial repertoire. While in Carnerero and Pérez-González (2014) the participants already had a broad repertoire of tact and listener, and three of them even had basic BiN skills, the participants of Byrne, Rehfeldt and Aguirre (2014) were assessed at level 1 of the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP - Sundberg, 2014), as they had tactile and listening skills at a basic level and their repertoires were restricted to tactile and listening responses that had been taught through direct training. This difference between the participants’ initial repertoires may have influenced the results obtained.

Longano and Greer (2015) used a procedure to induce BiN in children with and without a diagnosis of ASD similar to SPOP. Pairing cycles between auditory and visual stimuli were presented, followed by touch probes until the participant reached the learning criterion, and, subsequently, BiN was tested with new sets of stimuli. The difference is that the stimuli used in the pairings were previously conditioned with reinforcers. In this study, all participants had complete nomination after being exposed to SPOP with at least two sets of stimuli.

It is observed, then, that while MEI is a procedure that has already been tested by several studies that have proved its effectiveness in the production of the two components of BiN in people with ASD or with developmental delay, SPOP is an alternative that still has few studies that tested and proved its effectiveness in producing speaker and listener behavior in this same population. However, SPOP has the advantage of getting closer to the way children acquire a repertoire of speaker and listener in the natural environment, bringing the teaching context of the natural contingencies of the individual’s life closer (Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014). SPOP, if it is effective, can therefore be an alternative for the establishment of BiN, with a lower degree of application complexity and less discriminatory demand for individuals, since the only response required is the pairing observation.

Studies already conducted show that both procedures can produce positive results with respect to teaching tact and listening responses to people with ASD, although there is more consistent evidence about the effectiveness of MEI. However, no studies were found that compare the two procedures in relation to their efficiency in this type of teaching. Other variables, in addition to effectiveness, should be considered when evaluating the efficiency of a teaching procedure, such as the time required for the individual to start presenting the target repertoires of the intervention, as well as the generalization of these repertoires. Thus, this study aimed to compare the efficiency of MEI and SPOP in the production of BiN, considering the number of sessions necessary for the participant to reach learning criteria and the generalization of the behaviors acquired with each procedure.

2 Method

In this section, we characterize the research participants, the environment in which the data collection took place and the materials used, the set of stimuli used, the experimental design and the stages for the data collection procedure, data recording and analysis and, finally, the agreement between observers and the integrity of the procedure.

2.1 Participants

Four boys with a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) participated in this study: P1, P3 and P4, all 5 years old, and P2, 9 years old. Before the beginning of the study, the verbal repertoire of each participant was assessed using the VB-MAPP (Sundberg, 2014). All presented performances compatible with Level 1 of the VB-MAPP in the domains of touch, listener response and skills of visual perception and matching to the model (P1 - reached 29 points out of a possible 45, P2 - 25.5, P3 - 25 and P4 - 25.5). The participants had an echo repertoire of words or short phrases, although with some pronunciation difficulties. None of the participants presented BiN, as assessed in the initial probe of this repertoire. All participants were attended by the specialized service to TEA at the Specialized Center for Rehabilitation and Health Promotion of the government of Maranhão (CER-MA), Brazil, with a frequency of five times a week and sessions lasting one and a half hours, where they received intervention based on Applied Behavior Analysis.

The legal guardians of the participants signed an Informed Consent Form authorizing their participation in the study. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Nucleus of Tropical Medicine at the Federal University of Pará - UFPA (Opinion 2,749,780).

2.2 Environment and materials

The research was carried out at the Specialized Center for Rehabilitation and Health Promotion of the government of Maranhão facilities, in an individualized care room or a reserved space in a room used for group care at times when activities were not taking place. For the record and data collection, pencils, record sheets designed specifically for the study and a digital video camera were used. To present the tasks, dummies and stimuli identified as potentially reinforcing for children were used, as described below.

2.3 Stimuli

Experimental stimuli: five sets of stimuli (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5) were used, each with three stimuli, which consisted of anthropomorphic dummies (ranging between 10 and 30 cm in height), unknown to the participants. Each set of stimuli was used in different stages of the procedure, as described in the Procedure. The stimulus names were dissyllable words (ex: BIPE, MAKE, DEDE), built from simple syllables that the participants were able to pronounce (which was evaluated in the first stage of the Procedure).

Consequential stimuli: a survey of possible reinforcers was made based on the indications of the caregivers and therapists who already attended the children. During the sessions, several options of possible reinforcing stimuli were available so that the child could have access during breaks or between teaching attempts. In addition, there were consequences in the form of praise and approval.

2.4 Experimental design

A single-subject design of multiple baselines was used with multiple probe technique among participants (Horner & Baer, 1978). In this study, the multiple baseline design was applied between pairs of participants (P1 and P2; P3 and P4). The order of application of the two experimental treatments tested in this study (MEI and SPOP) varied between the participants of each pair. For participants P1 and P3, MEI treatment was applied initially and, later, SPOP. For the participants P2 and P4, the order of application of the treatments was reversed. Thus, it was possible to evaluate the isolated effect of each of the treatments and also the effect of their order of application, in addition to replicating them between two participants.

2.5 Procedure

The study was developed in nine stages shown in Figure 1, in general, and described in more detail below. All participants went through all stages of the procedure, but the moment of starting the baseline and implementing the first experimental treatment (Stages 4 and 5) varied according to the multiple baseline design with the multiple probe technique. Initially, all participants went through stages 1 to 3. Subsequently, the baseline of participants P1 and P3 was measured, followed by the implementation of the other stages of the procedure described above. When participants P1 and P3 reached the criterion in the first experimental treatment implemented, participants P2 and P4 went through another BiN probe, followed by the baseline and the other stages of the procedure.

Initial assessment of the pronunciation of syllables (Stage 1): this stage aimed to select a set of syllables that all participants were able to pronounce correctly to compose the names of the stimuli. The assessment was made based on the observation of words vocalized by the children during the service composed of the evaluated syllables or in echoic attempts, in which the experimenter asked the child to repeat the syllable spoken by him/her (e.g. “repeat BA”), without consequence for hit or miss. One to two assessment sessions were carried out for each child until 23 syllables that all participants correctly pronounced were identified.

Initial tests of tact and listener selection (Stage 2): the objective of this stage was to verify whether the stimuli that were used in the study were, in fact, unknown to the participants. Any stimulus to which the participant responded correctly in attempts to listen more than once and in attempts to touch at least once would be replaced. Stimuli that the participant named more than once with the same name were also excluded, even though this was not the name assigned by the experimenter.

In this stage, a tact block (composed of nine attempts, three for each stimulus) and a listener selection block were performed for each set of stimuli that was used in the study. Tactile attempts consisted of presenting a stimulus to the participant (the experimenter held the stimulus in front of the participant), followed by the question “Who is it?” or “What’s his name?”. The order of presentation of the stimuli was randomized by the experimenter at the time of application. A response was considered correct when the participant said the name of the stimulus correctly pronounced. If the participant emitted a vocal response that did not correspond to the stimulus name or did not respond within 5 seconds, the response was considered incorrect. For participant P4, the tact test attempts consisted only of presenting the stimulus, without any instructions, which was done to prevent the participant from just repeating the instruction given by the therapist, since this was his frequent behavioral pattern.

Listener attempts consisted of presenting three stimuli on the table in front of the participant, followed by the instruction “Show me (name of the stimulus)”. Both the order of presentation of the model stimuli and the position of the paring stimuli presented on the table were randomized by the experimenter at each attempt. An answer was considered correct if the participant pointed, touched or took the stimulus named by the experimenter. Any response other than that or if the participant did not respond within 5 seconds was considered an error. Correct or wrong answers were followed by an interval between attempts of approximately three seconds. Tact tests were always performed before listener tests to ensure that the fact that the participant heard the names of stimuli in listener attempts did not interfere with his/her performance in the tact tests.

BiN Probes with Set C1 (Stages 3, 6 and 8): the probe was based on the BiN test proposed by Greer and Ross (2008). Initially, the training of paring the model by identity (Identity Matching to Sample - IDMTS) with the participant was carried out, with tact of the model stimulus by the experimenter. The training was performed in blocks of nine attempts (three per stimulus) per session. The task consisted of presenting a model stimulus, while the experimenter said its name in the instruction given, for example: “Put together (name of the stimulus)”. At the same time, three comparison stimuli were presented, one of which was identical to the model. The correct answer consisted of placing the model stimulus superimposed on the corresponding comparison stimulus or selecting the corresponding stimulus among the three comparison stimuli. Correct responses were followed by praise and approval and/or tangible reinforcing stimuli. When confirming correct answers, the experimenter said again the name of the model stimulus, for example: “Very well! This is the (name of the stimulus)”. In this way, the participant had the opportunity to hear the name of each stimulus in its presence, six times in each block of IDMTS.

This training was performed until the participant reached the criterion of two sessions with 89% correct answers or one with 100%. After the participant reached the learning criterion in the IDMTS task, tact probes and listener selection was performed, identical to the initial tests of these repertoires (only with C1). It was considered a demonstration of the BiN repertoire performances above 78% of correct answers in each tested repertoire, and the participant could not commit more than one error per stimulus. Participants who underperformed this were exposed to Stage 4 of the study (baseline).

Baseline (Stage 4): consisted of performing at least three sessions of tact tests and listener selection (identical to the initial tests) with C1 stimuli, until the participant demonstrated stability in the performance of the two repertoires or one decreasing trend.

MEI treatment (Stage 5 or 7): this experimental treatment consisted of training the IDMTS repertoires with the tact of the model stimulus by the experimenter, selection listener and tact, with C2 and C3. The order of the operants requested in each attempt was randomized, as well as the stimuli presented, for example, a sequence of three attempts could be: IDMTS with the CADU stimulus, tact with the BOBI stimulus and listener with PEPE.

The IDMTS training was identical to that performed in the initial BiN probe stage. Attempts to listen to selection and tact were as described in the initial testing stage of these repertoires, with the difference that correct attempts were reinforced, while incorrect attempts or omissions of response for more than 5 seconds were followed by a correction procedure, which consisted of re-presentation of instruction and help to perform the task (physical or gestural help for attempts at listening and vocal model help for tact attempts), followed by less enthusiastic verbal feedback (just confirmation that the participant had got it right, for example: “Yes, this is BOBI”) than that provided in attempts in which the participant responded correctly. In addition, during training, some types of help were used to facilitate the issue of correct answers by the participant, especially at the beginning of the training. In tactile training, immediate and delayed vocal model help was used (the experimenter waited an average of 3 seconds after instruction, if the participant did not respond, help was given), and in listener training, immediate and delayed gestural help. The tips were being withdrawn according to the performance of the participants in previous attempts. In cases where the participants looked away at the moment or shortly after the presentation of the stimuli, responded by selecting two stimuli simultaneously or in sequence, or showed resistance behavior to accomplish the task, the attempt was disregarded and presented again.

The sessions consisted of nine attempts (three per stimulus) for each repertoire, totaling 27 attempts. These were divided into smaller blocks of attempts (usually three blocks of nine attempts, but varying according to the child’s tolerance level), among which the child had an interval of 2 to 5 minutes in which he/she had access to reinforcing items.

The learning criterion for this treatment was 89% correct answers in each repertoire for two consecutive sessions or one with 100% for each repertoire. The treatment interruption criterion was 12 sessions without the child being able to reach the learning criterion.

After the participant reached one of the two criteria above with the first training set for the MEI treatment (C2), a BiN probe with C1 was performed. If the participant did not present the BiN, according to the criteria defined in this study (78% correct answer in both repertoires, not being able to present more than one error per stimulus), a second MEI training was performed with a new set of stimuli (C3), and after reaching the learning or interruption of treatment criteria, he/she was exposed to a new BiN probe with C1.

SPOP treatment (Stage 5 or 7): This treatment was performed with C4. Each SPOP session had a total number of 27 auditory-visual pairings, so that the number of pairings was matched with the number of attempts in an MEI session. These pairings consisted of the presentation of a stimulus followed by its name dictated by the experimenter, after he had guaranteed the child’s attention to the presented stimulus. No tact or listener responses were required from the child. The pairings were made in a context of play, in which the experimenter interacted with the child using stimuli (dummies) in different ways that could be interesting for the child and favor the directing of his/her attention to the target stimuli. If spontaneous responses of tact or listener selection occurred during the interaction, these were not differentially reinforced. If the experimenter presented the auditory stimulus, but noticed that the participant was not looking at the visual stimulus at that moment, the pairing was re-presented.

The pairings were divided into blocks (usually nine pairs, three per stimulus, but may vary according to the child’s momentary interest in the stimuli), presented in a random manner and/or following the participants’ interest in the stimuli. At the end of each block, the participant had an interval of 2 to 5 minutes, in which he/she had access to reinforcing items and could play freely.

After the third interval, the participant went through touch probes and listener selection with the stimuli of set C4, identical to the initial tests of these repertoires. The learning criterion in this treatment was 89% of correct answers in the tact and listener probes (for each repertoire) in two consecutive sessions or 100% in one, and the criterion for interrupting the treatment was the same adopted for the MEI. After reaching the learning criterion, the participant proceeded to a new appointment probe with C1.

Generalization test (Stage 9): It was identical to the initial BiN probe, performed, however, with C5.

2.6 Data recording and analysis

The accuracy of tact responses, listener selection and IDMTS was recorded at each attempt during testing sessions, BiN probes and MEI training. The data were analyzed considering the percentage of correct tact and listener responses in the BiN probes and in the generalization test, in addition to the number of sessions necessary to reach the learning criterion in each of the treatments.

2.7 Agreement between observers and integrity of the procedure

From the videos of the experimental sessions, another researcher recorded the performance of each participant in 30% of the sessions in each stage of the study to establish an index of agreement between observers ([Agreement/Agreement + Disagreement] x 100) and, in addition, a record was made via a protocol previously prepared for the integrity of the procedure, to verify that the procedures of each stage of the study were implemented correctly for each participant ([Correct implementations/Total implementations] x 100). The observer agreement rate for BiN probes, baseline, MEI treatment and SPOP treatment were 96%, 100%, 99% and 100%, respectively, for P1, 94%, 94%, 96% and 98% for P2, 98%, 100%, 94% and 100% for P3, and 97%, 100%, 97% and 89% for P4. And the percentages of procedure integrity in the BiN probes, baseline, MEI treatment and SPOP treatment were, respectively, 100%, 100%, 98% and 99% for P1, 99%, 100%, 99% and 99% for P2, 100%, 100%, 100% and 100% for P3 and 99%, 100%, 99% and 98% for P4.

3 Results

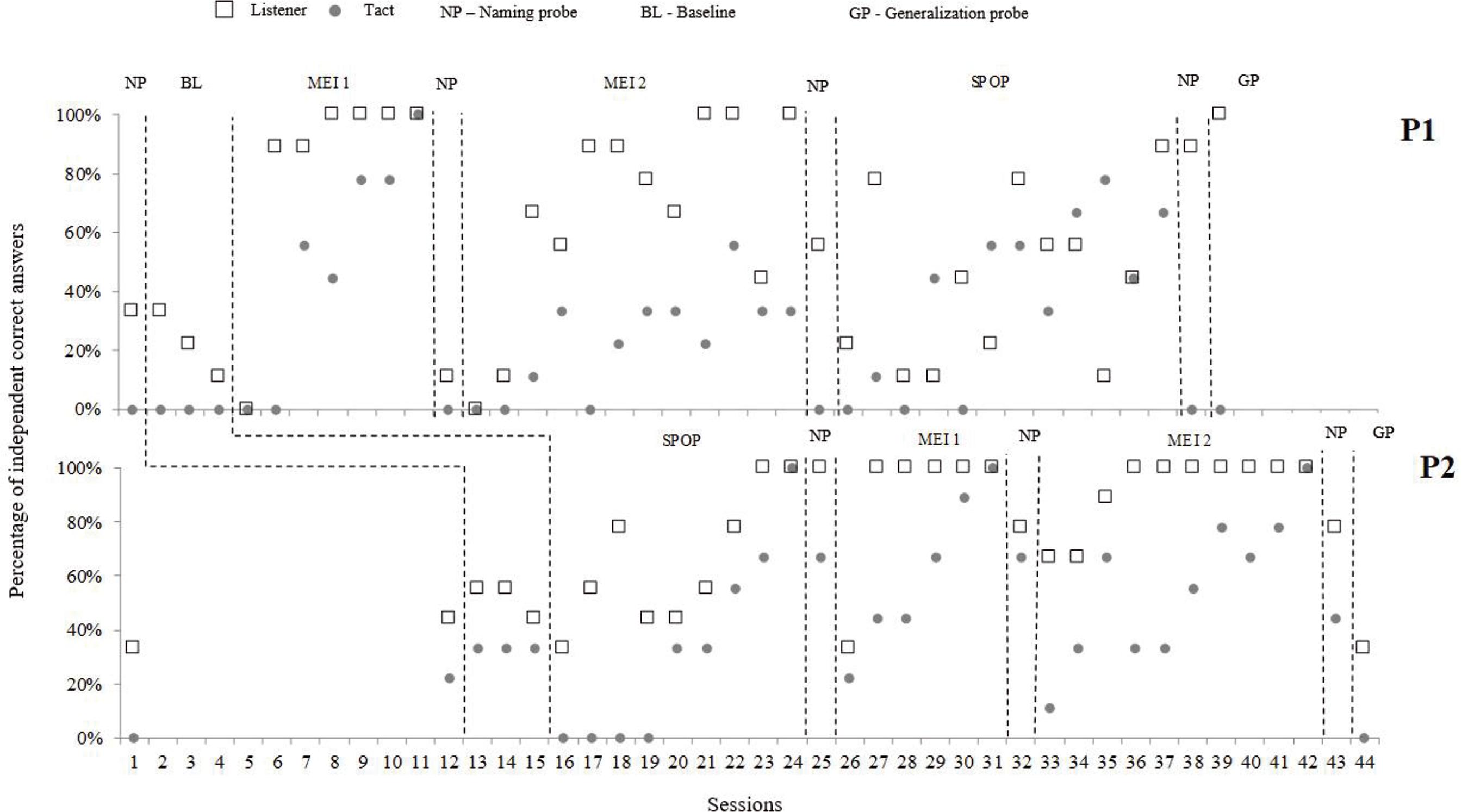

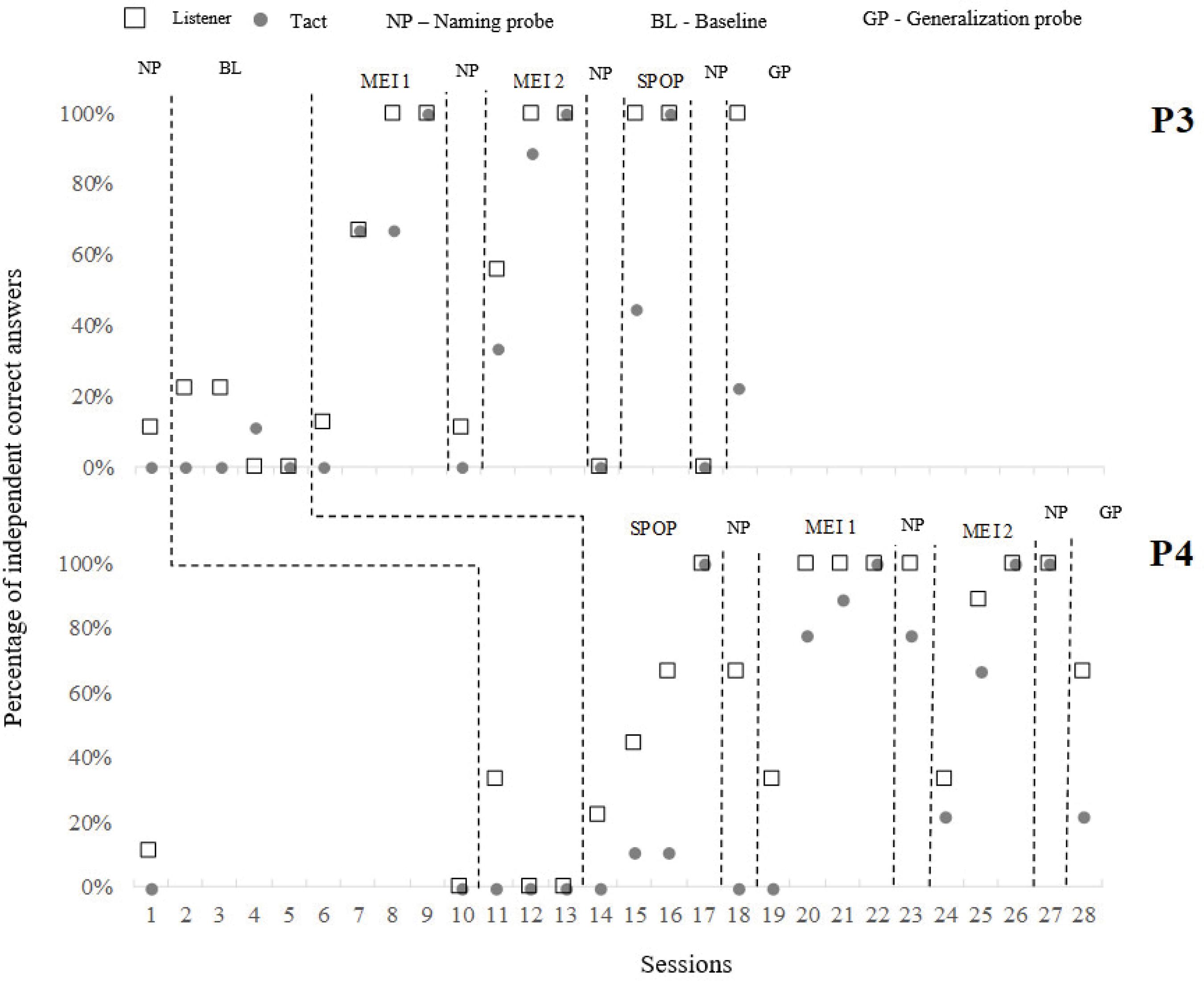

Figures 2 and 3 show the percentage of correct independent tact and listener responses throughout all stages of the procedure from the initial BiN probe. In the initial probes and baseline, no participant demonstrated the BiN repertoire. When analyzing the isolated effect of each treatment, it is observed that the participants submitted first to the MEI (P1 and P3) did not obtain any improvement in the tact and listener performances after the MEI 1 training in relation to their performance in the initial probes of BiN and baseline. It took seven sessions for P1 to reach the learning criteria in MEI 1 and four for P2.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the research data.

Figure 2 Percentage of independent correct responses in the tact and listener repertoires in the BiN probes with C1, in the MEI training sessions with C2 and C3, in the tact and listener probes with C4 performed at each SPOP session and in the generalization performed with C5, for P1 and P2.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the research data.

Figure 3 Percentage of independent correct responses in the tact and listener repertoires in the BiN probes with C1, in the MEI training sessions with C2 and C3, in the tact and listener probes with C4 performed at each SPOP session and in the generalization performed with C5, for P3 and P4.

In the MEI 2 training, participant P1 reached the criterion of interruption of treatment (12 sessions without reaching the learning criterion), even though he reached the criterion for the listener’s repertoire. In the probe after the MEI 2 training, P1 showed an increase in listener repertoire (56%), showing, for one of the stimuli, 100% correct response, but no gain in relation to the tact repertoire. P3 needed three sessions to achieve learning criteria in the MEI 2 training. In the post MEI 2 probe, however, he presented responses that indicated the formation of wrong relations between the auditory and visual stimuli of C1 (the participant named the visual BIPE stimulus “Dedé” and the DEDE stimulus “Make” consistently in all attempts). This happened in both tactile and listener attempts. Therefore, the performance of P3 was 0% for both repertoires in the post MEI 2 probe. Regarding the participants who started training with SPOP treatment, both had an increase in listener performance in relation to the baseline (100% - P2 and 67% - P4), but only P2 showed an increase in the tact repertoire (67%, with 100% correct answers for two stimuli in the set). Nine sessions were required for P2 to reach the SPOP learning criteria and four for P4.

After the second treatment implemented (SPOP for P1 and P3), P1 showed 89% of correct answers in the listener’s repertoire and 0% in the tact repertoire in the post-training probe, not having reached the learning criterion with C4 until the twelfth session. P3, on the other hand, presented in the post SPOP probe the same problem presented in the post MEI 2 probe (formation of the same wrong relations between the auditory and visual stimuli of C1), and thus the child’s performance was 0% for both repertoires. Due to this problem, and considering the excellent performance that P3 had in SPOP training (reaching criteria in just two sessions with the C4 Set), it was decided to perform the generalization probe with P3, even though this participant had not reached BiN criterion in any of the repertoires with an initial set.

As for P2, after MEI 1 (second treatment implemented), there was no difference in the tact repertoire in relation to the previous probe (67%), while the listener performance decreased (78%). This participant needed six sessions to reach the learning criterion in MEI 1. In the post MEI 2 probe, the performance of P2 in the tact test dropped to 44% and the listener remained in 78% (with only one error for two of the set stimuli), the child needed ten sessions to reach the learning criterion in MEI 2. P4, who followed the same training sequence as P2, showed an increase in tact performance (78%, with two errors for one of the stimuli in the set) and listener (100%) in the post MEI 1 probe, in which the child reached the learning criteria in four sessions. In the post MEI 2 probe, P4 showed 100% correct answers in both repertoires, the child took three sessions to reach the learning criteria in this training.

None of the participants gave correct tact responses in the initial tests with C5. As for the initial listener tests, the results were 11% for P1, 67% for P2, 44% for P3 and 0% for P4. In generalization probes (see Figures 2 and 3), P1 and P3 performed 100% in the listener test, but 0% and 22%, respectively, in the tact test. The result of P2 was 0% for tact and 33% for listener, indicating that the child’s high performance in the initial listener tests was by chance. While P4 showed an increase in relation to his initial performance in the BiN probes, with 22% in the tact test and 67% in the listener test.

4 Discussion

This study sought to compare the efficiency of MEI and SPOP procedures to induce BiN in children with ASD, since both procedures have been reported in scientific studies to be effective in producing this repertoire, or at least its components of tact or listener. The data indicate that SPOP was more efficient in relation to the increase in tact and listener performance of participants in post-training probes when this was the first treatment applied, as well as the number of sessions necessary for participants to reach learning criteria. However, the training sequence in which MEI was initially applied and, afterwards, the SPOP proved to be more efficient for the generalization of the BiN repertoire for a new set of stimuli.

It is important to note that the data indicates that only P2 presented speaker responses (tact) after SPOP in the naming probes, this being the only participant who presented correct tact responses in the initial probes and in all baseline sessions. In addition, it presented the highest percentage of correct answers during the baseline. On the other hand, P4, who did not present any correct tact response in the initial and baseline probes, presented in the probes after MEI, indicating that MEI can be more effective when the individual does not yet have emergent relationships of tact with the listener before exposure to object-name pairings.

Data from participants P1 and P3, who had MEI as their first treatment applied, reveal that it was not effective in producing BiN, even after exposure to two MEI training sessions, with two different sets. This result is in line with the results found by other studies that used MEI to induce BiN (Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Greer et al., 2005; Greer, Stolfi, & Pistoljevic, 2007; Hawkins et al., 2009; Olaff, Ona, & Holth, 2017; Santos & Souza, 2016).

The divergence found in this study in relation to previous studies may have been influenced by specific problems that the participants had during the application of the procedure. P1 reached the learning criterion in MEI 1 in seven sessions, however, in the MEI 2 training, presented responses that indicated generalization of stimuli between two of the C3 stimuli (used in MEI 2) and one of the C2 stimuli (used in MEI 1), which presented formal similarities between them. Therefore, the participant made several mistakes by naming the C3 stimuli with the same name he learned for the C2 stimulus, and the correction procedure was not enough to solve this problem. In the case of P3, he presented rapid acquisition of the three trained repertoires, both in MEI 1 (four sessions to reach criteria) and in MEI 2 (three sessions), however, in the BiN probe after MEI 2, the participant presented training of wrong name-object relations with C1 stimuli, as described in the results. A possible explanation for this fact is that the task of IDMTS with touch of the model stimulus by the experimenter was not sufficient to guarantee the participant’s observation response to the relevant auditory and visual stimuli in each attempt, which prevented the correct relationship between them being established (Longano & Greer, 2015).

In the case of participants who were first submitted to SPOP, the data in the post-training probes show that one of the participants (P2) presented an emergence of the BiN listener component and an increase in the tact repertoire in relation to the baseline. P4, although he did not demonstrate the emergence of any of the components of BiN, showed an increase in the performance of the listener in relation to the baseline. The fact that the SPOP training configuration may be closer to the BiN probes than the MEI training configuration may have contributed to this result.

In addition, it must be remembered that SPOP alone already produces BiN with the set of stimuli used in this treatment (C4), since tact and listener responses were not taught directly, but they were tested after each cycle of pairings. Therefore, SPOP was effective in producing complete BiN with three of the participants (P2, P3 and P4), even with fewer sessions than those required for MEI training, if we add the sessions of MEI 1 and MEI 2. These data corroborate with studies that demonstrate that SPOP is an effective procedure to produce emergence of verbal repertoires without direct training, such as tact and listener (Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2015; Longano & Greer, 2015; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Huffman, 2012).

The fact that the participants did not meet the criteria for BiN with C1 after SPOP may be related to the fact that they were exposed to this treatment with only one set of stimuli. In the study conducted by Longano and Greer (2015), in which the participants reached the criterion for complete naming after the auditory-visual pairing observation procedure, all participants needed to be exposed to more than one set to acquire the complete BiN. In addition, in the study performed by Longano and Greer (2015), the stimuli used underwent a previous procedure for conditioning reinforcers, which was not done in this study. Future studies may investigate whether the SPOP procedure would be more efficient in inducing the BiN repertoire if previously conditioned auditory and visual stimuli were used as reinforcers.

Some participants even emitted spontaneous tones of C4 stimuli during SPOP sessions (P1 and P4), which could not be reinforced. This data, although not directly measured in this study, leads us to reflect on the role of reinforcement in the BiN acquisition process. Horne and Lowe (1996) describe that, at the beginning of this process, the occurrence of listener and tact responses are reinforced by caregivers, which leads us to question whether SPOP combined with reinforcement of spontaneous verbal responses could not be more effective. Future studies may investigate this issue.

A differential of this study in relation to previous studies that also applied SPOP (Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2015; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Huffman, 2012), is that, in this study, this treatment was applied in a more naturalistic context, as the pairings were presented to participants in a play situation during the interaction between child and experimenter. This context is similar to the daily situations experienced by children and the way they naturally learn name-object relationships, which may have favored learning via SPOP. However, further research is needed to investigate whether there is a difference in the effectiveness of SPOP for establishing BiN when it is applied in a more structured manner and when it is applied in a more naturalistic context.

Regarding the order of presentation of the experimental treatments, considering the results of the generalization test, the most effective sequence was the one that MEI was implemented first and then SPOP, applied to participants P1 and P3, as these participants demonstrated emergence of the component as a BiN listener in the test performed with a new stimulus set (C5), in which they were exposed only to an IDMTS session with a tact of the model stimulus by the experimenter. The results of P3 specifically suggest that MEI can function as a facilitator of learning BiN via incidental teaching, as occurs in SPOP, because, after having gone through the two MEI training sessions, the participant needed only two SPOP sessions to achieve learning criterion for tact and listener, with the listener component emerging in the first session. Participants P2 and P4, who were submitted to the reverse order of implementation of the experimental treatments, did not meet the criteria for BiN in the generalization test. A possible explanation for this result, considering that the SPOP treatment produced better results in this study, is that the performance of the participants was the product of recency in relation to the last treatment applied, since those participants who had the SPOP last had a better result in the generalization test.

One of the limitations of this study was the use of the same set of stimuli (C1) in all BiN probes. It is possible that the results obtained in the last probes are the result of the accumulation of pairings that the participants went through during the IDMTS sessions that preceded the tact and listener tests in each probe, and not only the implemented treatments. For example, the number of matches that P4 needed to reach the SPOP learning criterion (36 per stimulus) was similar to the number of matches that he was exposed to by adding all the IDMTS sessions of the BiN probes with C1 (30 by stimulus). However, P4’s performance in the generalization test was considerably better compared to the initial probe of the repertoire with C1, which suggests a learning set effect, since the number of pairings necessary for the emergence of BiN with new sets of stimuli may decrease as the child is exposed to pairing cycles with new sets, which is in accordance with the results of Carnerero and Pérez-Gonzaléz (2014) that show that the number of pairings necessary for the emergence of the tact repertoire decreased as new sets of stimuli were presented.

Nonetheless, the results obtained in the generalization test are not subject to this limitation, since a new set of stimuli was used, and, therefore, represent reliable data on the acquisition of naming after the implemented treatments. In future studies, we recommend the use of different sets of stimuli for each nomination probe. In addition, a control group could be used that is exposed only to the naming probes (with IDMTS) and does not undergo treatments.

5 Conclusion

This study suggested that SPOP may be effective in inducing BiN in children with ASD, and that a combination of MEI and SPOP favors the generalization of BiN. Considering that BiN is seen as a milestone in development that enables a rapid growth of the verbal repertoire, allowing the child to establish more effective relationships with the world (Horne & Lowe, 1996; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009; Greer & Longano, 2010), these results can assist in the choice of procedures when planning effective and efficient behavioral interventions for teaching verbal skills to individuals with atypical development.

2The research from which this article resulted was funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) (Process 88887091031201401) and by the National Institute of Science and Technology on Behavior, Cognition and Teaching (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq - Process 573972/2008-7, and São Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP - Process 2008/57705-8). The first author received a master’s scholarship from CAPES and the second author is a CNPq Productivity fellow.

REFERENCES

Byrne, B. L., Rehfeldt, R. A., & Aguirre, A. A. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of the stimulus pairing observation procedure and multiple exemplar instruction on tact and listener responses in children with autism.The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 30, 160-169. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-014-0020-0 [ Links ]

Carnerero, J. J., & Pérez-Gozález, L. A. (2014). Induction of naming after observing visual stimuli and their names in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35, 2514-2526. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.004 [ Links ]

Carnerero, J. J., & Pérez-Gozález, L. A. (2015). Emergence of naming relations and intraverbals after auditory stimulus pairing. Psychological Record, 65, 509-522. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40732-015-0127-2 [ Links ]

Fiorile, C. A., & Greer, R. D. (2007). The induction of naming in children with no prior tact responses as a function of multiple exemplar histories of instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 23, 71-87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393048 [ Links ]

Gilic, L., & Greer, R. D. (2011). Establishing naming in typically developing two-year-old children as a function of multiple exemplar speaker and listener experiences. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 157-177. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393099 [ Links ]

Greer, R. D., & Longano, J. (2010). A rose by naming: How we may learn how to do it. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 26, 73-06. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393085 [ Links ]

Greer, R. D., & Ross, D. E. (2008). Verbal Behavior Analysis: Inducing and expanding new verbal capabilities in children with language delays. Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Greer, R. D., & Speckman, J. (2009). The integration of speaker and listener responses: A theory of verbal development. The Psychological Record, 54, 449-488. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395674 [ Links ]

Greer, R. D., Stolfi, L., Chavez-Brown, M., & Rivera-Valdes, C. (2005). The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21, 123-134. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393014 [ Links ]

Greer, R. D., Stolfi, L., & Pistoljevic, N. (2007). Emergence of Naming in preschoolers: A comparison of multiple and single exemplar instruction. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 8, 119-131. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15021149.2007.11434278 [ Links ]

Hawkins, E., Kingsdorf, S., Charnock, J., Szabo, M., & Gautreaux, G. (2009). Effects of multiple exemplar instruction on naming. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 10, 95-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15021149.2009.11434324 [ Links ]

Horne, P. J., & Lowe, C. F. (1996). On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 65, 185-241. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1901%2Fjeab.1996.65-185 [ Links ]

Horner, R. D., & Baer, D. M. (1978). Multiple-probe technique: A variation on the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11, 189-196. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11 [ Links ]

Longano, J. M., & Greer, R. D. (2015). Is the source of reinforcement for naming multiple conditioned reinforcers for observing responses? The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 31, 96-117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-014-0022-y [ Links ]

Miguel, C. F. (2016). Common and intraverbal bidirectional naming. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32(2), 125-138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0066-2. [ Links ]

Olaff, H. S., Ona, H. N., & Holth, P. (2017). Establishment of naming in children with autism through multiple response-exemplar training. Behavioral Development Bulletin, 22(1), 67-85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bdb0000044 [ Links ]

Rosales, R., Rehfeldt, R. A., & Huffman, N. (2012). Examining the utility of the stimulus pairing observation procedure with preschool children learning a second language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45, 173-175. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1901%2Fjaba.2012.45-173 [ Links ]

Santos, E. L. N., & Souza, C. B. A. (2016). Ensino de nomeação com objetos e figuras para crianças com autismo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(3), 1-10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-3772 e 32329 [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1992). Verbal Behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group and The B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Smith, T. (2001). Discrete trial training in the treatment of autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16, 86-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/108835760101600204 [ Links ]

Sundberg, M. L. (2014). Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program. Concord, CA: AVB Press. [ Links ]

Vallinger-Brown, M., & Rosales, R. (2014). An investigation of stimulus pairing and listener training to establish emergent intraverbals in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 30, 148-159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-014-0014-y [ Links ]

Received: December 07, 2019; Revised: April 23, 2020; Accepted: July 06, 2020

text in

text in