Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial

Print version ISSN 1413-6538On-line version ISSN 1980-5470

Rev. bras. educ. espec. vol.26 no.4 Marília Oct./Dec 2020 Epub Dec 09, 2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-54702020v26e0062

Research Report

Attitudes Towards People with Disabilities: a Systematic Literature Review2

3Department of Economics, Management, Industrial Engineering and Tourism. University of Aveiro. Aveiro/Portugal. E-mail: cunha.leal@ua.pt.

4Department of Economics, Management, Industrial Engineering and Tourism. University of Aveiro. Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policy Research Unit (GOVCOPP). Aveiro/Portugal. E-mail: celeste.eusebio@ua.pt.

5Department of Economics, Management, Industrial Engineering and Tourism. University of Aveiro. Higher Education Policy Research Unit (CIPES). Aveiro/Portugal. E-mail: m.joao@ua.pt.

The investigation area of accessible tourism (AT) has a growing trend. However, most studies focus on physical accessibility, and only a few analyse the attitudes of students and professionals in this sector towards people with disabilities (PwD). This review aims to analyse the work carried out in other scientific areas on attitudes towards PwD. It is intended to map methodologies, measurement instruments and main variables and factors related with attitudes, to promote their inclusion in society. Research was carried out at Scopus and 492 records were obtained. Of these, 96 articles were selected for analysis. Results show that the assessment of attitudes towards PwD is a topic of great relevance in several scientific areas. Studies use several instruments to measure these attitudes. Previous experiences, quality, and frequency of contact with PwD and knowledge about disability have an influence on attitudes. However, results differ in the influence of the sociodemographic profile on attitudes towards PwD. There is a trend towards the use of quantitative methodologies, using the questionnaire as a tool for data collection. The article ends by identifying areas of research relevant to the increasing knowledge of the factors that influence these attitudes and, consequently, to the development of AT.

KEYWORDS: Accessible tourism; Attitudes scale; People with disabilities; Determinants of attitudes; Literature review

A área de investigação do turismo acessível (TA) apresenta uma tendência de crescimento. Contudo, a maioria dos estudos foca-se na acessibilidade física, havendo poucos que analisem as atitudes dos estudantes e profissionais desse setor relativamente às pessoas com deficiência (PcD). Assim sendo, esta revisão tem como objetivo analisar os trabalhos efetuados em outras áreas científicas sobre as atitudes relativamente às PcD. Pretende-se mapear metodologias, instrumentos de medição e principais variáveis e fatores associados às atitudes, para promover a sua inclusão na sociedade. Realizaram-se pesquisas na Scopus, tendo-se obtido 492 registos. Destes, foram selecionados 96 artigos para análise. Os resultados evidenciam que a avaliação das atitudes relativamente às PcD é uma temática de grande relevância em várias áreas científicas. Os estudos utilizam diversos instrumentos para medir essas atitudes. As experiências anteriores, qualidade e frequência do contato com PcD e conhecimento acerca da deficiência têm influência nas atitudes. Contudo, os resultados divergem na influência do perfil sociodemográfico nas atitudes face às PcD. Existe tendência para o recurso a metodologias quantitativas utilizando, como instrumento de recolha de dados, o questionário. O artigo termina identificando áreas de investigação relevantes para o aumento do conhecimento dos fatores que influenciam essas atitudes e, consequentemente, para o desenvolvimento do TA.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Turismo acessível; Escala de atitudes; Pessoas com deficiência; Determinantes das atitudes; Revisão bibliográfica

1 Introduction

The concept of accessible tourism concerns the collaborative process established between the most diverse actors in the tourism system, with the aim of promoting the adaptation of the tourist offer to all tourists, according to their access needs, whether permanent or temporary, visible or invisible, more or less severe, so that they can enjoy it in autonomy, equality and dignity, without physical barriers or related to services, products and environments (World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2013). Much of the scientific research work in this area focuses on physical accessibility. A limited number of studies analyze the interpersonal relationships between people with disabilities (PwD) and professionals in the tourism industry, more specifically the attitudes of the latter towards PwD (Shaw & Coles, 2004). This being a terrain where scientific production in the field of tourism is scarce, it makes perfect sense to investigate what is done in other scientific areas and sectors of activity, whose services involve permanent contact with PwD.

Disability is described as a multidimensional phenomenon that results from the interaction between people and the physical and social environment. Thus, disability and functionality are influenced by the interaction between health conditions and contextual factors, which can be human or environmental (World Health Organization [WHO], 2004). Attitudes towards PwD result from the interaction between them and other people, with or without disabilities, who are in the same social environment. According to Fazio and Olson (2003), these attitudes come from isolated action, or through a combination of three components: (i) the affective component (involves the person’s sentimental part); (ii) the cognitive component (involves personal beliefs and knowledge); and (iii) the behavioral component (the way the attitude influences the action or behavior).

The attitudes related to a given stimulus (object or social group) always assume an evaluative character that can be positive or negative (Allport, 1935), of greater or lesser intensity (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), serving certain functions that help the response of the person, and their adaptation, to the social environment that surrounds them (Katz, 1960).

Negative attitudes towards PwD represent one of the greatest barriers to their participation in social activities, such as, for example, access to public health, education, leisure, recreation and sports services, further contributing to the disabling effects of disability (Duckworth, 1988), reducing opportunities for social integration and promoting the worsening of their condition (Paris, 1993). The presence of positive attitudes unequivocally contributes to the integration and participation of PwD in the social activities mentioned previously, improves the quality of the services provided and reduces the stigma of PwD, and is currently one of the main concerns that society seeks to face and resolve (Fitzsimmons & Barr, 1997).

In 1928, Thurstone concluded that “attitudes can be measured” (1928, p. 529), which, inevitably, “opened doors to one of the most important constructs of Social Psychology” (Gawronski, 2007, p. 573). Since then, there have been countless attempts to design a model for measuring attitudes towards PwD, all based on the most diverse theories. However, the vast majority of these instruments have some problems related to their reliability (consistency in measurements), flexibility of use (they can be used at different times of data collection) or confidence in their use (frequency of use in studies) (Lam et al., 2010).

According to Findler, Vilchinsky and Werner (2007), there are two groups of measurement techniques: direct, self-describing or explicit, in which the person is asked directly what his/her attitude towards a given object is, and indirect or implicit, in which the attitude is measured based on an indicator other than the response (which implies the absence of control in the response, absence of intentionality, absence of awareness and efficiency of the cognitive processing that allows its occurrence with low cognitive resources).

In order to increase knowledge about the methodologies used to measure attitudes towards PwD, this systematic literature review study aims to collect the main instruments, and the methodologies used in several scientific areas, to measure attitudes towards PwD, as well as to identify the main variables that explain them. By mapping the findings already achieved by the investigations developed, especially in other areas of knowledge, and in other economic activities, this systematic review aims to identify gaps and opportunities in terms of scientific research on attitudinal barriers within the scope of accessible tourism.

2 Development

In this section, the methodology used in this research will be approached, which involves two steps described below.

2.1 Methodology

This systematic literature review aims to analyze the studies that have been published in the scientific literature related to the attitudes of students or professionals from various sectors towards PwD, in order to identify the scientific areas in which they have been carried out, the methodologies that have been used, as well as the factors that influence the attitudes of students and professionals towards PwD.

The methodology used comprises two stages: (i) identification of the studies to be analyzed and (ii) description of the process to be used to analyze the content of the identified studies.

2.1.1 First stage - identification of studies to be analyzed

In this systematic literature review, we favored the Scopus database, one of the largest in the world, which houses articles previously reviewed by other researchers (Elsevier, 2019), having used, as a research protocol, the process described in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of the research protocol, criteria and filters for selecting documents

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("attitudes") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("disabled people") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("people with disabilit*") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("people with special needs") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("training") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("education") | ||

| Database | Scopus | |

| Search fields | Articles and article reviews | |

| Results | 492 | |

| Period | 1973-2019 | |

| Search date | 09/05/2019 | |

| Criteria | Filter | Result |

| Language | English, French, Spanish and Portuguese | 492 |

| Type of document | Articles and reviews | 492 |

| Thematic analyzed | Title and abstract | 148 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

As can be seen in Table 1, data collection was carried out on May 9, 2019. The results obtained allow us to observe that the first document identified was published in 1973. In order to capture all types of documents related to the subject under study, the following words were used in the research: “attitudes”, “disabled people”, “people with disabilit*”, “people with special needs” associated with “Education”, “training” and “undergraduate*” and “graduate*”. The investigation includes all areas, since, as previously exposed, scientific production with a focus on this theme is relatively scarce.

Subsequently, and as shown in Table 1, the criteria for inclusion or exclusion of documents were defined. Thus, as a filter, the search was restricted to documents whose language was English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, a content analysis was carried out based on the title and summary of each document, eliminating all those that did not correspond to the main theme of this investigation.

As an example of reasons for the exclusion of articles, those that address topics that do not fit the objectives of the present review should be highlighted, such as articles whose focus of analysis is on measuring the impacts of public inclusion policies (Fisher & Purcal, 2017), evaluating the satisfaction and quality of care provided, identifying barriers or their impacts on the community. All those whose objects of study were different from what was established for this review were also excluded.

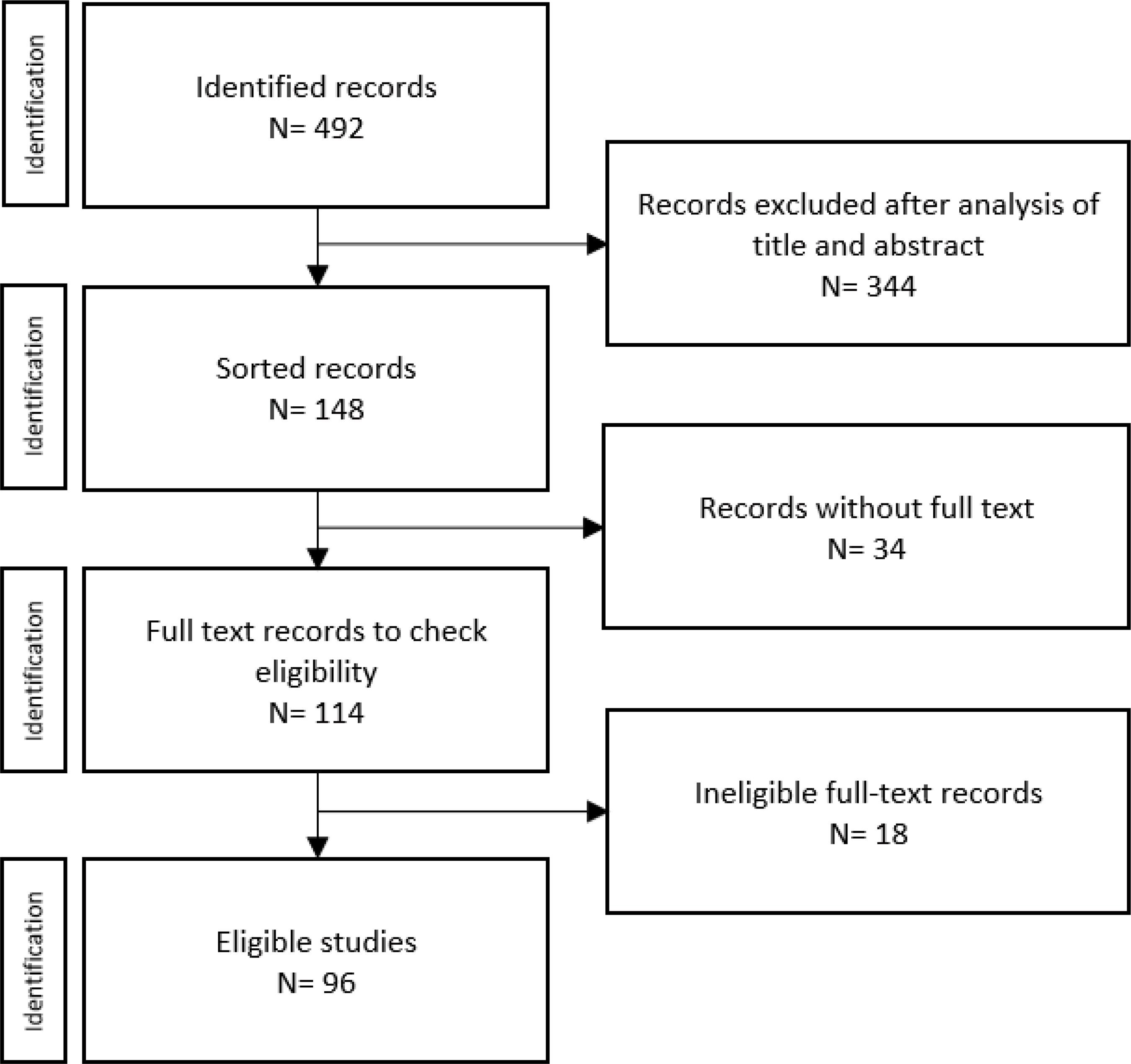

As can be seen in Figure 1, of the 148 articles previously selected, 114 were obtained with full text, of which 18 were excluded, as they presented themes that did not fit the objective of the present review: evaluation of inclusive policies, associated themes to religion or with another thematic approach not relevant to this study. Thus, for this systematic literature review, 96 records were selected.

2.1.2 Second step - content analysis

A qualitative analysis of the content of the 96 scientific articles selected was carried out according to the procedure described in the first stage. The information extracted from each one was cataloged in summary tables taking into account the main concepts, variables, scales and methodologies used in terms of data collection and analysis.

3 Results and discussion

In this section, the study areas of the scientific production analyzed are presented, the scientific journals in which the articles were published, the geographical distribution of the samples, the themes of the articles analyzed, the typologies of disabilities addressed, the methodology used for data collection, the instruments for measuring attitudes towards PwD and, finally, the factors that influence attitudes.

3.1 Areas of study

As can be seen in Table 2, the publications of scientific articles related to the attitudes of students and professionals towards PwD are, for the most part, linked to the areas of Health and Education, concentrating their production in the last two decades.

Table 2 Investigations by scientific area over time.

| Scientific area | No. of studies | 1973-1980 | 1981-1990 | 1991-2000 | 2001-2010 | 2011-2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 51 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 19 | 22 |

| Education | 31 | - | 1 | 3 | 7 | 20 |

| Engineering | 4 | - | - | - | 1 | 3 |

| Tourism | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Economics and Management | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Other | 7 | - | - | - | 2 | 5 |

| Total | 96 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 29 | 53 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Health-related areas have seen an increase in their scientific production on the subject under consideration, especially in the last two decades. On the one hand, this interest may be associated with the new paradigm that emerged with the biopsychosocial approach to disability in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), to the detriment of the medical model of disability prevalent in Western societies (Daruwalla & Darcy, 2005). On the other hand, it seems to indicate a greater awareness of the inclusion of PwD in society by identifying and responding to their specific needs (WHO, 2011).

With regard to Education, the main reason associated with this considerable increase in scientific production seems to be the greater awareness of the issue of the inclusion of PwD in the educational system, and the concern about the preparation of teachers and the acceptance of other students, as Cortés e Campos (2016) highlighted when referring to the concern of the Spanish education system with this matter.

Also in the area related to engineering and architecture, three studies were identified, whose main objective is to assess the predisposition of its students, and professionals, for the use of the principles of Universal Design in their work.

In relation to the area of tourism, only two articles were identified, which address the potential of education as an agent for changing attitudes towards PwD, which, obviously, indicates a clear gap in this area.

3.2 Journals

Table 3 shows the main scientific journals, as well as the number of articles published in each of them on the subject under consideration. It should be noted that these scientific journals seem to consider that investigating attitudes towards PwD and training actions, or changes to curricular programs, are a topic with high academic interest.

Table 3 Main journals of publication.

| Journal | No. of Studies | % per Journal |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Education | 5 | 5,2 |

| Nurse Education Today | 4 | 4,2 |

| Disability and Health Journal; Disability and Rehabilitation; European Journal of Dental Education; European Journal of Special Needs Education; International Journal of Rehabilitation Research; | 3 | 3,1 |

| Health and Social Care in the community; Journal of Applied Social Psychology; Rehabilitation Psychology; Revista Complutense de Educación; Medical Teacher; Rehabilitation Couselling Bulletin | 2 | 2,1 |

| Other | 60 | 62,5 |

| Total | 96 | 100,0 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

As can be seen on Table 3, the scientific journals identified are mostly linked to education, more specifically to the health area, or have objectives closely linked to disability, rehabilitation or social action.

3.3 Geographic distribution

Table 4 summarizes the geographic distribution of the samples used in the reported studies related to the articles under analysis. The most developed Western countries, such as the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia and Spain, were the ones where more studies were carried out on the subject. Of the total studies analyzed, 50% were carried out in these countries.

Table 4 Geographic distribution of the samples.

| Country | No. of studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 19 | 19,8 |

| United Kingdom | 14 | 14,6 |

| Australia | 10 | 10,4 |

| Spain | 6 | 6,3 |

| Israel; New Zeland | 5 | 5,2 |

| Turkey; Ireland | 4 | 4,2 |

| Hong Kong; Canada | 3 | 3,1 |

| Other | 23 | 23,9 |

| Total | 96 | 100,0 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

These results suggest that there is a growing awareness of the importance that this subject represents, in order to better understand the reality about the attitudes of students and professionals in each scientific area in relation to PwD in the most developed countries, as well as the most effective methodologies traditionally used, either for its mediation or for its amendment.

3.4 Themes analyzed

With regard to the thematic approach to investigation (Table 5), in this review, it was found that studies can be categorized into three groups: (i) studies that analyze only attitudes towards PwD; (ii) studies that analyze issues related to the training of students and professionals; and (iii) studies that analyze issues related to attitudes and training. The first group includes studies that analyze only the attitudes (of professionals or students) towards PwD. Forty-one of the analyzed articles are part of this group, which were produced essentially in the last 20 years. These studies are mainly related to the development or evaluation of instruments to measure attitudes towards PwD (Faulks et al., 2018; González, Martínez, Alonso, Avi, & Río, 2016; Holler & Werner, 2018; Lam et al., 2010; Smith & McCulloch, 1978) and with the analyses of factors which may influence them.

Table 5 Theme approach of the investigations.

| Thematic approach | Period | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973-1980 | 1981-1990 | 1991-2000 | 2001-2010 | 2011-2020 | N | % | |

| Attitude | 1 | - | 3 | 12 | 25 | 41 | 42,7 |

| Education | - | - | 6 | 13 | 19 | 38 | 39,6 |

| Attitude and education | - | 3 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 17 | 17,7 |

| Total | 1 | 3 | 10 | 29 | 53 | 96 | 100,0 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The second group of studies comprises 38 of the analyzed articles, dated between 1991 and 2020, whose main focus is training. These studies analyze mainly the impacts of intervention programs, curricula, or other training and awareness actions, on the attitudes of students and professionals in relation to PwD. Finally, the third group of studies simultaneously addresses issues related to attitudes towards PwD and the training of professionals, or future professionals (students), who contact people with these characteristics (Table 5).

3.5 Typologies of the disability addressed

Table 6 shows the types of disabilities focused on the investigations. In the 96 research studies selected, the vast majority (74.0%) do not specify which type of disability is being analyzed. Of the studies that clearly specify which type of disability is being analyzed, the segments that have received the most attention include cognitive/intellectual/learning PwD (15.6% of studies) and motor PwD (13.5% %).

3.6 Data collection methodology

Table 7 illustrates the methods used in the studies that are the object of analysis in this review article. As can be seen, the quantitative methodology, with data collection through questionnaires, is the one that has been most used in this type of studies (68.8% of those that were analyzed).

Table 7 Methods and approach of the studies.

| Method and approach | No. of studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 68 | 70,8 |

| Questionnaire | 66 | 68,8 |

| Secondary data analysis | 1 | 1,0 |

| Experimental | 1 | 1,0 |

| Qualitative | 11 | 11,4 |

| Interview | 5 | 5,2 |

| Mixed qualitative methods | 1 | 1,0 |

| Case studies | 4 | 4,2 |

| Narrative analysis | 1 | 1,0 |

| Mixed | 11 | 11,5 |

| Review | 6 | 6,3 |

| Total | 96 | 100,0 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Qualitative methodologies were used in only 11.4% of the studies analyzed, with interviews (5.2%) and case studies (4.2%) being the most used data collection techniques. On the other hand, 11.5% of the analyzed studies use mixed methods, and only 6.3% are theoretical studies, mostly literature review studies.

3.7 Attitude measurement instruments facing pwd

According to Fisher and Purcal (2016), personal attitudes and behavior are correlated, but they are not always identical: a person can think and feel in a certain way, but act in another way, sometimes the complete opposite. In the studies analyzed in this review article, several instruments were identified to measure attitudes towards PwD (Table 8).

Table 8 Instruments for measuring the attitudes identified.

| Instrument | N | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes Toward Disabled Persons - ATDP | 1 | 24 | 34,8 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices Scale - TEIP | 1 | 5 | 7,3 |

| Scale of Attitudes Toward disabled Persons (SADP); Multidimensional Attitude Scale (MAS) | 2 | 4 | 5,8 |

| Sentiments, Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education Revised Scale (SACIE-R) | 1 | 3 | 4,4 |

| Attitudes to Disability Scale (ADS); Interaction with Disabled people (IDP); Modified Issues in Disabiliy Scale (MIDS); (Disability Attitudes in Health Care (DAHC) | 4 | 2 | 2,9 |

| Attitudes towards Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Physical Education (AISDPE); Actitudes hacia las Personas com Discapacidad (APD); Attitudes Toward Educational Inclusion (ATEI); Attitudes Toward Teaching Individuals with Disabilities in Physical education (ATIPDPE); Chedoke-McMaster Attitudes Towards Children with Handicaps (CATCH); Escala de Atctitudes hacia las Personas com Discapacidad (EAPD); Exercise Barriers Scale (EBS); Filtering Unconsciousness Matching of Implicit Emotions (FUMIE); Mental Retardation Attitude Inventory-Revised (MRAI-R); Physical Educators' Attitudes Toward Teaching the Handicapped (PEATTH); Perceived Physical Ability (PPA); Physical Self Presentation Confidence (PSPC); Rosenbers' Self-esteem Scale (RSES); Attitude Towards Inclusive Education Scale (ATIES); Contact with Disabled Persons (CDP); Community Living Attitudes Scale Mental Retardation (CLAS-MR); Disability Social Relationship Scale (DSRS); Implicit Association Test (IAT); Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS); Schwartz Value Survey (SVS); Community Living Attitudes Scale— Intellectual Disability (CLAS-ID) | 21 | 1 | 1,5 |

| Total | 30 | 69 | 100,0 |

The main instruments used to measure attitudes are, for the most part, scales of agreement or disagreement, in relation to certain situations or opinions. Table 8 summarizes the 30 instruments for measuring attitudes that were identified in the studies analyzed. Of these instruments, the Attitudes Toward Disabled Persons (ATDP) scale (in its 3 forms - O, A and B), developed by Yuker in the 1960s, brings together the preference of about 34.8% of authors, as the main instrument of measurement of attitudes, while others prefer to develop instruments adapted to the specific situation they intend to investigate.

Still as a (secondary) complementary instrument, or for validating the results obtained with the main instrument, some authors favored the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices Scale (TEIP) (specifically to measure the effectiveness of teachers’ inclusive practices), or to measure attitudes in relation to specific types of PwD such as, for example, the Community Living Attitudes Scale - Mental Retardation (CLAS-MR), which measures attitudes towards people with cognitive or intellectual development problems.

Furthermore, among the articles analyzed, six aimed to test and validate scales developed specifically to measure the attitudes of different populations towards PwD, or to test the adaptation of scales already developed and validated to other resident populations, at other geographic points.

3.8 Factors that influence attitudes

In the literature that analyzes attitudes towards PwD, several factors are identified that may influence them. The most mentioned factors are related to the knowledge that professionals and students have of the needs of this population group, the contact/interaction they have had with PwD, namely their previous experience, their sociodemographic profile and the fact that they have already attended training actions on the topic (Table 9).

Table 9 Categories of factors and variables that influence attitudes towards PwD.

| Factor/variable categories | There is association | There is no association | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Contact/interaction | 50 | 90,9 | 5 | 9,1 | 55 | 100,0 |

| Previous experience | 9 | 90,0 | 1 | 10,0 | 10 | 18,2 |

| Contact (quality and frequency) | 41 | 91,1 | 4 | 8,9 | 45 | 81,8 |

| Knowledge | 45 | 100,0 | - | - | 45 | 100,0 |

| Knowledge about the disability | 45 | 100,0 | - | - | 45 | 100,0 |

| Sociodemographic profile | 29 | 69,0 | 13 | 31,0 | 42 | 100,0 |

| Age | 8 | 66,7 | 4 | 33,3 | 12 | 28,6 |

| Gender | 11 | 61,1 | 7 | 38,9 | 18 | 42,8 |

| Academic qualifications | 10 | 83,3 | 2 | 16,7 | 12 | 28,6 |

| Training actions | 21 | 100,0 | - | - | 21 | 100,0 |

| Simulation /Recreation | 12 | 100,0 | - | - | 12 | 57,1 |

| Vídeo/Narratives | 6 | 100,0 | - | - | 6 | 28,6 |

| Other | 3 | 100,0 | - | - | 3 | 14,3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 9 also details the studies that address these associations. Regarding the studies that analyzed the association between previous experiences with PwD and attitudes towards them, a large part of these studies (90.0%) concluded that previous experiences can have a positive influence on attitudes, as stated by Wagner and Stewart (2001) and Seccombe (2007a, 2007b). However, according to Richard et al. (2005), this association is not statistically significant.

Of the studies analyzed, 41 suggest that the quality and frequency of contact with PwD has an association with attitudes towards them. According to Au and Man (2006), the frequency and intensity of contact promote positive attitudes towards PwD. However, others consider that this association is not statistically significant (Duckworth, 1988; Kurita & Kusumi, 2010; Sánchez & Puerta, 2018).

Regarding knowledge about disability, the totality of studies analyzed (45) point out that information is essential to promote positive attitudes towards PwD, as Di Nardo Kudlacek, Tafuri and Sklenarikova (2014) suggest.

In relation to the demographic profile, it appears that the most variables studied by the authors, with regard to the influence they may have on attitudes towards PwD, concern gender, age and academic qualifications. When it comes to gender, the authors who investigated this matter suggest that the fact of belonging to the female sex is directly associated with more positive attitudes towards PwD. However, seven studies were identified, whose results do not corroborate the previous conclusion.

With regard to age, it should be noted that 8 of the 12 studies that address this issue suggest that age has an association with attitudes; thus, as age increases, attitudes towards PwD become more positive. However, Parasuram (2006) warns that both young teachers with less years of service and older people have more positive attitudes than the group of middle-aged teachers. However, in four of the studies analyzed, the association between age and attitudes is not confirmed.

According to the results obtained, in 10 of the studies analyzed, it is observed that people with higher educational qualifications have more positive attitudes. However, there are two studies that claim that this variable does not influence attitudes towards PwD.

In relation to training actions, those with different types of approach were identified, which, in common, share the objective of sensitizing students or professionals and, consequently, promoting attitudinal changes. Among them, the simulations stand out, mainly based on sessions with a variable and predetermined time duration. These, when well designed, can promote increased knowledge about the needs of PwD, improve attitudes of trainees, as well as the acceptance of PwD (Lindsay & Edwards, 2013). However, French (1992) considers that an excessive focus on problems, difficulties and simulation exercises can provide misleading information and instill negative attitudes towards PwD instead of positive ones.

In Table 9, it can be seen that all identified interventions have a positive association with attitudes towards PwD. Regarding the resources used in the training actions, in this review, “simulation or recreation”, “videos and narratives” and “others” were identified. The first ones were referred to as having a positive association with attitudes in 12 studies, and involve situations in which the participants assume the role of a person with a disability, facing, themselves, the problems to which the latter are exposed daily. The second concerns videos, films and narratives of the problems experienced by PwD, having analyzed six studies that show that these types of training are effective in changing attitudes towards PwD. Finally, there are other training actions (3), based on the assumptions of “Self-image” (Cohen, Roth, York, & Neikrug, 2012) or “Self-efficacy” (Forlin, Cedillo, Romero-Contreras, Fletcher, & Rodriguez Hernández, 2010; Loreman, Sharma, & Forlin, 2013; Oswald & Swart, 2011; Van Boxtel, Napholz, & Gnewikow, 1995; Velonaki et al., 2015), used mainly in studies related to inclusive education, which revealed a positive association in relation to attitudes of inclusion of PwD.

4 Conclusion

The main objective of this systematic literature review was to map the main trends in methodological approaches in the scientific areas that have been studying the theme the most, the factors that may be associated with attitudes (positive or negative) towards PwD and the instruments used for its measurement. The scientific literature, with a focus on the attitudes of Higher Education students and professionals in the field of tourism towards PwD is sparse, so there was a need to search for relevant information in other scientific areas, whose activity sectors, by their nature, imply contact with PwD.

It became clear that the topic under consideration is relevant, in a transversal way, to most scientific areas that aim to promote positive attitudes of students and professionals towards PwD and, consequently, to improve the quality of the services provided, as well as to promote the social inclusion of these people. This is an important element, since the presence of positive attitudes towards PwD is perceived as a crucial element in the social integration of these people, increasing the opportunities of this group of the population, contributing to their valorization (Fitzsimmons & Barr, 1997).

This review allowed us to conclude that the vast majority of studies on attitudes towards PwD are in the scientific areas related to health, especially in the areas of nursing and medicine, and also education. Studies in the health field indicate the objective of improving the quality of the service provided and promoting the integration of PwD in society. In the area of education, the intention is, above all, to promote the inclusion of students with disabilities. Studies have had a special temporal impact over the past two decades.

Regarding the geographic distribution of the samples included in the analyzed studies, it appears that they are concentrated mainly in the more developed countries, headed by the USA, United Kingdom, Australia and Spain, but also have a global expression, which may indicate that this field research is becoming a new trend of interest for academics.

With regard to the approach method, it was clear that the vast majority make use of quantitative methods, tending to use one or more questionnaires for data collection. On the other hand, the thematic approach of investigations covers both the assessment of attitudes towards PwD, as well as the training of students and professionals to deal with PwD, or even in both themes.

Most of the scientific articles analyzed conclude that knowledge about the topic, as well as the quality and frequency of contact with PwD, influence attitudes towards the latter, in the sense that the greater the exposure to these factors, the more positive the attitudes are.

As Findler, Vilchinsky and Werner (2007) had suggested, this review showed that there are two groups of techniques for measuring attitudes towards PwD: direct, self-describing or explicit and indirect or implicit. However, this review made it possible to identify thirty instruments for measuring attitudes, with the vast majority of studies showing a preference for the use of ATDP. However, most studies do not specify a type of disability, so it is assumed that these are assessed in general. This review also serves as an alert for the tourism sector by bringing to the debate the importance of studying attitudes towards PwD, on the part of Higher Education students (future professionals in the sector), which has been so neglected.

This systematic literature review faced some limitations that may interfere with the conclusions. Mainly with the inability to obtain all the articles identified in the first selection phase, which could add relevant data. However, the differences between the populations under study may skew the results when applying to similar studies in the tourism sector, since, despite the contact between professionals in each area and the PwD is a common point of their services, their nature may vary due to the individual need of each person.

REFERENCES

Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (v. 1, pp. 798-844). Clark University Press. [ Links ]

Au, K. W., & Man, D. W. K. (2006). Attitudes toward people with disabilities: a comparison between health care professionals and students. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29(2), 155-160. [ Links ]

Cohen, R., Roth, D., York, A., & Neikrug, S. (2012). Youth leadership program for changing self-image and attitude toward people with disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation, 11(3), 197-218. [ Links ]

Cortés, E. G., & Campos, S. R. (2016). ¿Barreras invisibles? Actitudes de los estudiantes universitarios ante sus compañeros con discapacidad. Revista Complutense de Educación, 27(1), 219-235. [ Links ]

Daruwalla, P., & Darcy, S. (2005). Personal and societal attitudes to disability. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 549-570. [ Links ]

Di Nardo, M., Kudlacek, M., Tafuri, D., & Sklenarikova, J. (2014). Attitudes of preservice physical educators toward individuals with disabilities at University Parthenope of Napoli. Acta Gymnica, 44(4), 211-221. [ Links ]

Duckworth, S. C. (1988). The effect of medical education on the attitudes of medical students towards disabled people. Medical Education, 22(6), 501-505. [ Links ]

Elsevier. (2019). The largest database of peer-reviewed literature. Scopus: Elsevier Solutions. [ Links ]

Faulks, D., Dougall, A., Ting, G., Ari, T., Nunn, J., Friedman, C. … Newton, J. T. (2018). Development of a battery of tests to measure attitudes and intended behaviours of dental students towards people with disability or those in marginalised groups. European Journal of Dental Education, 22(2), e278-e290. [ Links ]

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Attitudes: foundations, functions, and consequences. In M. A. Hogg, & J. Cooper (Eds.), The sage handbook of Social Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 139-160). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Findler, L., Vilchinsky, N., & Werner, S. (2007). The multidimensional attitudes scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS). Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50(3), 166-176. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Attitude Formation. In M. Fishbein, & I. Ajzen (Eds.), Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introdution to theory and research (pp. 216-287). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. [ Links ]

Fisher, K. R., & Purcal, C. (2017). Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(2), 161-174. [ Links ]

Fitzsimmons, J., & Barr, O. (1997). A review of the reported attitudes of health and social care professionals towards people with learning disabilities: Implications for education and further research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1(2), 57-64. [ Links ]

Forlin, C., Cedillo, I. G., Romero-Contreras, S., Fletcher, T., & Rodriguez Hernández, H. J. (2010). Inclusion in Mexico: Ensuring supportive attitudes by newly graduated teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(7), 723-739. [ Links ]

French, S. (1992). Simulation exercises in disability awareness training: a critique. Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(3), 257-266. [ Links ]

Gawronski, B. (2007). Editorial: attitudes can be measured! But what is an attitude?. Social Cognition, 25(5), 573-581. [ Links ]

González, V. A., Martínez, B. A., Alonso, M. A. V., Avi, M. R., & Rio, C. J. (2016). Evaluación de actitudes de los profesionales hacia las personas con discapacidad. Siglo Cero. Revista Española Sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 47(2), 7-41. [ Links ]

Holler, R., & Werner, S. (2018). Perceptions towards disability among social work students in Israel: Development and validation of a new scale. Health and Social Care in the Community, 26(3), 423-432. [ Links ]

Katz, D. (1960). The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 163. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/266945 [ Links ]

Kurita, T., & Kusumi, T. (2010). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward people with disabilities and effects of the internal and external sources of motivation to moderating prejudice. Psychologia, 52(4), 253-260. [ Links ]

Lam, W. Y., Gunukula, S. K., McGuigan, D., Isaiah, N., Symons, A. B., & Akl, E. A. (2010). Validated instruments used to measure attitudes of healthcare students and professionals towards patients with physical disability: A systematic review. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 7(1), 1-7. [ Links ]

Lindsay, S., & Edwards, A. (2013). A systematic review of disability awareness interventions for children and youth. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(8), 623-646. [ Links ]

Loreman, T., Sharma, U., & Forlin, C. (2013). Do pre-service teachers feel ready to teach in inclusive classrooms? A Four Country Study of Teaching Self-efficacy. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 27-44. [ Links ]

Organização Mundial da Saúde (2004). Classificação Internacional de Funcionalidade, Incapacidade e Saúde. Lisboa: DGS. [ Links ]

Oswald, M., & Swart, E. (2011). Addressing South African pre-service teachers’ sentiments, attitudes and concerns regarding Inclusive Education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(4), 389-403. [ Links ]

Parasuram, K. (2006). Variables that affect teachers’ attitudes towards disability and inclusive education in Mumbai, India. Disability and Society, 21(3), 231-242. [ Links ]

Paris, M. (1993). Attitudes of medical students and health care professionals toward people with disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 74(8), 818-825. [ Links ]

Richard, I., Compain, V., Mouillie, J. M., Adès, F., Garnier, F., Dubas, F., & Saint-André, J. P. (2005). Évaluation de l’attitude vis-à-vis des personnes handicapées des étudiants en médecine de 3e et 4e année par le questionnaire «attitude towards disabled persons». Effets de l’enseignement théorique et de stages dans les services de médecine physique et ré. Annales de Readaptation et de Medecine Physique, 48(9), 662-667. [ Links ]

Sánchez, M. T. P., & Puerta, M. A. (2018). Primeros pasos hacia la inclusión: actitudes hacia la discapacidad de docentes en educación infantil. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 36(2), 365-379. [ Links ]

Seccombe, J. A. (2007a). Attitudes towards disability in an undergraduate nursing curriculum: A literature review. Nurse Education Today, 27(5), 459-465. [ Links ]

Seccombe, J. A. (2007b). Attitudes towards disability in an undergraduate nursing curriculum: The effects of a curriculum change. Nurse Education Today, 27(5), 445-451. [ Links ]

Shaw, G., & Coles, T. (2004). Disability, holiday making and the tourism industry in the UK: A preliminary survey. Tourism Management, 25(3), 397-403. [ Links ]

Smith, N. J., & McCulloch, J. W. (1978). Measuring attitudes towards the physically disabled: Testing the “Attitude Towards Disabled Persons” scale (A.T.D.P. Form O) on social work and non-social work students. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 1(2), 187-197. [ Links ]

Thurstone, L. L. (1928). Attitudes Can Be Measured. American Journal of Sociology 33, 529-554. [ Links ]

Van Boxtel, A. M., Napholz, L., & Gnewikow, D. (1995). Using a wheelchair activity as a learning experience for student nurses. Rehabilitation Nursing, 20(5), 265-272. [ Links ]

Velonaki, V. S., Kampouroglou, G., Velonaki, M., Dimakopoulou, K., Sourtzi, P., & Kalokerinou, A. (2015). Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and behavior toward deaf patients. Disability and Health Journal, 8(1), 109-117. [ Links ]

Wagner, A. K., & Stewart, P. J. B. (2001). An internship for college students in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation - effects on awareness, career choice, and disability perceptions. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 80, 459-465. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2011). World report on disability 2011. American Journal of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Association of Academic Physiatrists, 91, 549. [ Links ]

World Tourism Organization (2013). Recommendations on Accessible Tourism. Recuperado em 30 de março de 2020 de https://www.accessibletourism.org/resources/accesibilityen_2013_unwto.pdf [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Abellán, J., Sáez-Gallego, N., & Reina, R. (2018). Explorando el efecto del contacto y el deporte inclusivo en Educación Física en las actitudes hacia la discapacidad intelectual en estudiantes de secundaria. RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias Del Deporte, 14(53), 233-242. [ Links ]

Anderson, E. S., Smith, R., & Thorpe, L. N. (2010). Learning from lives together: Medical and social work students’ experiences of learning from people with disabilities in the community. Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(3), 229-240. [ Links ]

Au, K. W., & Man, D. W. K. (2006). Attitudes toward people with disabilities: a comparison between health care professionals and students. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29(2), 155-160. [ Links ]

Aulagnier, M., Verger, P., Ravaud, J. F., Souville, M., Lussault, P. Y., Garnier, J. P., & Paraponaris, A. (2005). General practitioners’ attitudes towards patients with disabilities: The need for training and support. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(22), 1343-1352. [ Links ]

Ay, P., Save, D., & Fidanoglu, O. (2006). Does stigma concerning mental disorders differ through medical education? A survey among medical students in Istanbul. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1), 63-67. [ Links ]

Bean, K. F., & Hedgpeth, J. (2014). The Effect of Social Work Education and Self-Esteem on Students’ Social Discrimination of People with Disabilities. Social Work Education, 33(1), 49-60. [ Links ]

Bizjak, B., Knežević, M., & Cvetrežnik, S. (2011). Attitude change towards guests with disabilities. Reflections from Tourism Students. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 842-857. [ Links ]

Brownlee, J., & Carrington, S. (2000). Opportunities for authentic experience and reflection: A teaching programme designed to change attitudes towards disability for pre-service teachers. Support for Learning, 15(3), 99-105. [ Links ]

Bu, P., Veloski, J. J., & Ankam, N. S. (2016). Effects of a brief curricular intervention on medical students’ attitudes toward people with disabilities in healthcare settings. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(12), 939-945. [ Links ]

Byron, M., Cockshott, Z., Brownett, H., & Ramkalawan, T. (2005). What does “disability” mean for medical students? An exploration of the words medical students associate with the term “disability”. Medical Education, 39(2), 176-183. [ Links ]

Campbell, J., Gilmore, L., & Cuskelly, M. (2003). Changing student teachers’ attitudes towards disability and inclusion. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 28(4), 369-379. [ Links ]

Carvalho-Freitas, M. N. de, & Stathi, S. (2017). Reducing workplace bias toward people with disabilities with the use of imagined contact. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(5), 256-266. [ Links ]

Castillo, J. L. Á., & Fernández, M. B. (2015). Predictors of attitudes toward inclusion of students with special educational needs in future education professionals. Revista Complutense de Educacion, 26(3), 627-645. [ Links ]

Chrysostomou, M., & Symeonidou, S. (2017). Education for disability equality through disabled people’s life stories and narratives: working and learning together in a school-based professional development programme for inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(4), 572-585. [ Links ]

Cohen, R., Roth, D., York, A., & Neikrug, S. (2012). Youth leadership program for changing self-image and attitude toward people with disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation, 11(3), 197-218. [ Links ]

Cortés, E. G., & Campos, S. R. (2016). ¿Barreras invisibles? Actitudes de los estudiantes universitarios ante sus compañeros con discapacidad. Revista Complutense de Educación, 27(1), 219-235. [ Links ]

Di Nardo, M., Kudlacek, M., Tafuri, D., & Sklenarikova, J. (2014). Attitudes of preservice physical educators toward individuals with disabilities at University Parthenope of Napoli. Acta Gymnica, 44(4), 211-221. [ Links ]

Dougall, A., Pani, S. C., Thompson, S., Faulks, D., Romer, M., & Nunn, J. (2012). Developing an undergraduate curriculum in Special Care Dentistry - by consensus. European Journal of Dental Education, 17(1), 46-56. [ Links ]

Downs, P., & Wiliams, T. (1994). Students attitudes toward integration of people with disabilities activity settings. Adapted Physical Activity Quartely, 11, 32-43. [ Links ]

Duckworth, S. C. (1988). The effect of medical education on the attitudes of medical students towards disabled people. Medical Education, 22(6), 501-505. [ Links ]

Dunn, D. S., Fisher, D. J., & Beard, B. M. (2012). Revisiting the mine/thine problem: A sensitizing exercise for clinic, classroom, and attributional research. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57(2), 113-123. [ Links ]

Edwards, D. M., Merry, A. J., & Pealing, R. (2002). Disability Part 3: Improving access to dental practices in Merseyside. British Dental Journal, 193(6), 317-319. [ Links ]

Evcil, N. (2010). Designers’ attitudes towards disabled people and the compliance of public open places: The case of Istanbul. European Planning Studies, 18(11), 1863-1880. [ Links ]

Faulks, D., Dougall, A., Ting, G., Ari, T., Nunn, J., Friedman, C. … Newton, J. T. (2018). Development of a battery of tests to measure attitudes and intended behaviours of dental students towards people with disability or those in marginalised groups. European Journal of Dental Education, 22(2), e278-e290. [ Links ]

Fisher, K. R., & Purcal, C. (2017). Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(2), 161-174. [ Links ]

Fitzsimmons, J., & Barr, O. (1997). A review of the reported attitudes of health and social care professionals towards people with learning disabilities: Implications for education and further research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1(2), 57-64. [ Links ]

Florian, V., & Kehat, D. (1987). Changing High School Students’ Attitudes Toward Disabled People. Health and Social Work, 12(1), 57-63. [ Links ]

Forlin, C., Cedillo, I. G., Romero-Contreras, S., Fletcher, T., & Rodriguez Hernández, H. J. (2010). Inclusion in Mexico: Ensuring supportive attitudes by newly graduated teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(7), 723-739 [ Links ]

Freeman, A. (1988). Students’ attitudes to disability. Journal of the British Institute of Mental Handicap (APEX), 16(3), 104-108. [ Links ]

French, S. (1992). Simulation Exercises in Disability Awareness Training: A critique. Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(3), 257-266. [ Links ]

French, S. (1994). Attitudes of Health Professionals towards Disabled People A Discussion and Review of the Literature. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom), 80(10), 687-693. [ Links ]

Galli, G., Lenggenhager, B., Scivoletto, G., Molinari, M., & Pazzaglia, M. (2015). Don’t look at my wheelchair! The plasticity of longlasting prejudice. Medical Education, 49(12), 1239-1247. [ Links ]

Girli, A., Sarı, H. Y., Kırkım, G., & Narin, S. (2016). University students’ attitudes towards disability and their views on discrimination. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 62(2), 98-107. [ Links ]

González, V. A., Martínez, B. A., Alonso, M. A. V., Avi, M. R., & Rio, C. J. (2016). Evaluación de actitudes de los profesionales hacia las personas con discapacidad. Siglo Cero. Revista Española Sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 47(2), 7-41. [ Links ]

Hassanein, E. E. A. (2015). Changing teachers’ negative attitudes toward persons with intellectual disabilities. Behavior Modification, 39(3), 367-389. [ Links ]

Hayashi, R., & Kimura, M. (2003). An Exploratory Study on Attitudes Toward Persons with Disabilities Among U.S. and Japanese Social Work Students. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 2(2-3), 65-85. [ Links ]

Hein, S., Grumm, M., & Fingerle, M. (2011). Is contact with people with disabilities a guarantee for positive implicit and explicit attitudes? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 26(4), 509-522. [ Links ]

Hitch, D., Dell, K., & Larkin, H. (2016). Does universal design education impact on the attitudes of architecture students towards people with disability? Journal of Accessibility and Design for All, 6(1), 26-48. [ Links ]

Holler, R., & Werner, S. (2018). Perceptions towards disability among social work students in Israel: Development and validation of a new scale. Health and Social Care in the Community, 26(3), 423-432. [ Links ]

Hsu, T. H., Huang, Y. T., Liu, Y. H., Ososkie, J., Fried, J., & Bezyak, J. (2015). Taiwanese attitudes and affective reactions toward individuals and coworkers who have intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120(2), 110-124. [ Links ]

Ison, N., McIntyre, S., Rothery, S., Smithers-Sheedy, H., Goldsmith, S., Parsonage, S., & Foy, L. (2010). “Just like you”: A disability awareness programme for children that enhanced knowledge, attitudes and acceptance: Pilot study findings. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(5), 360-368. [ Links ]

Keller, C., & Siegrist, M. (2010). Psychological Resources and Attitudes Toward People. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(2), 389-401. [ Links ]

Kritsotakis, G., Galanis, P., Papastefanakis, E., Meidani, F., Philalithis, A. E., Kalokairinou, A., & Sourtzi, P. (2017). Attitudes towards people with physical or intellectual disabilities among nursing, social work and medical students. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23-24), 4951-4963. [ Links ]

Kurita, T., & Kusumi, T. (2010). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward people with disabilities and effects of the internal and external sources of motivation to moderating prejudice. Psychologia, 52(4), 253-260. [ Links ]

Kwon, K. A., Hong, S. Y., & Jeon, H. J. (2017). Classroom readiness for successful inclusion: teacher factors and preschool children’s experience with and attitudes toward peers with disabilities. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(3), 360-378. [ Links ]

Lindsay, S., & Edwards, A. (2013). A systematic review of disability awareness interventions for children and youth. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(8), 623-646. [ Links ]

Loreman, T., Sharma, U., & Forlin, C. (2013). Do pre-service teachers feel ready to teach in inclusive classrooms? A Four Country Study of Teaching Self-efficacy. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 27-44. [ Links ]

Lu, J., Webber, W. B., Romero, D., & Chirino, C. (2017). Changing attitudes toward people with disabilities using public media: an experimental study. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 61(3), 175-186. [ Links ]

Lynch, J., Last, J., Dodd, P., Stancila, D., & Linehan, C. (2018). ‘Understanding Disability’: Evaluating a contact-based approach to enhancing attitudes and disability literacy of medical students. Disability and Health Journal, 12(1), 65-71. [ Links ]

Lyon, L., & Houser, R. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of the attitudes to disability scale for use with nurse educators. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 24(3), 465-476. [ Links ]

Mac Giolla Phadraig, C., Nunn, J. H., Tornsey, O., & Timms, M. (2015). Does special care dentistry undergraduate teaching improve dental student attitudes towards people with disabilities? European Journal of Dental Education, 19(2), 107-112. [ Links ]

Mamboleo, G. I., Diallo, A., Ocharo, R. M., Oire, S. N., & Kampfe, C. M. (2015). Socio-ecological influences of attitudes toward disability among Kenyan undergraduate students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(3), 216-223. [ Links ]

Mitchell, K. R., Hayes, M., Gordon, J., & Wallis, B. (1984). An investigation of the attitudes of medical students to physically disabled people. Medical Education, 18(1), 21-23. [ Links ]

Moroz, A., Gonzalez-Ramos, G., Festinger, T., Langer, K., Zefferino, S., & Kalet, A. (2010). Immediate and follow-up effects of a brief disability curriculum on disability knowledge and attitudes of PM&R residents: A comparison group trial. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 360-364. [ Links ]

Mulligan, K., Calder, A., & Mulligan, H. (2017). Inclusive design in architectural practice: Experiential learning of disability in architectural education. Disability and Health Journal, 11(2), 237-242. [ Links ]

Novo Corti, I., Calvo Babío, N., & Muñoz Cantero, J. M. (2015). Una perspectiva de género Introducción. Anales de Psicología, 31, 155-171. [ Links ]

Novo Corti, I., & Muñoz Cantero, J. M. (2015). Los estudiantes universitarios ante la inclusión de sus compañeros con discapacidad: indicadores basados en la teoría de la acción razonada para los estudios de economía y empresa en la Universidad de A Coruña = University students facing inclusión. REOP - Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 23(2), 105. [ Links ]

Oermann, M. H., & Lindgren, C. L. (1995). An educational program’s effects on student’s attitudes toward people with disabilities: A 1-Year Follow-Up. Rehabilitation Nursing, 20(1), 6-10. [ Links ]

Oswald, M., & Swart, E. (2011). Addressing South African pre-service teachers’ sentiments, attitudes and concerns regarding Inclusive Education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(4), 389-403. [ Links ]

Parasuram, K. (2006). Variables that affect teachers’ attitudes towards disability and inclusive education in Mumbai, India. Disability and Society, 21(3), 231-242. [ Links ]

Parkinson, G. (2006). “Counsellors” attitudes towards Disability Equality Training (DET). British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 34(1), 93-105. [ Links ]

Pernice, R., & Lys, K. (1996). Interventions for attitude change towards people with disabilities: how successful are they? International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 19, 171-174. [ Links ]

Richard, I., Compain, V., Mouillie, J. M., Adès, F., Garnier, F., Dubas, F., & Saint-André, J. P. (2005). Évaluation de l’attitude vis-à-vis des personnes handicapées des étudiants en médecine de 3e et 4e année par le questionnaire «attitude towards disabled persons». Effets de l’enseignement théorique et de stages dans les services de médecine physique et ré. Annales de Readaptation et de Medecine Physique, 48(9), 662-667. [ Links ]

Romero-Contreras, S., Garcia-Cedillo, I., Forlin, C., & Lomelí-Hernández, K. A. (2013). Preparing teachers for inclusion in Mexico: how effective is this process? Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(5), 509-522. [ Links ]

Ryan, J. (2011). Access and participation in higher education of students with disabilities: Access to what? Australian Educational Researcher, 38(1), 73-93. [ Links ]

Sánchez, M. T. P., & Puerta, M. A. (2018). Primeros pasos hacia la inclusión: actitudes hacia la discapacidad de docentes en educación infantil. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 36(2), 365-379. [ Links ]

Schitko, D., & Simpson, K. (2012). Hospitality staff attitudes to guests with impaired mobility: the potential of education as an agent of attitudinal change. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 17(3), 326-337. [ Links ]

Seccombe, J. A. (2007a). Attitudes towards disability in an undergraduate nursing curriculum: A literature review. Nurse Education Today, 27(5), 459-465. [ Links ]

Seccombe, J. A. (2007b). Attitudes towards disability in an undergraduate nursing curriculum: The effects of a curriculum change. Nurse Education Today, 27(5), 445-451. [ Links ]

Shields, N., Bruder, A., Taylor, N., & Angelo, T. (2011). Influencing physiotherapy student attitudes toward exercise for adolescents with Down syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(4), 360-366. [ Links ]

Smith, N. J., & McCulloch, J. W. (1978). Measuring attitudes towards the physically disabled: Testing the “Attitude Towards Disabled Persons” scale (A.T.D.P. Form O) on social work and non-social work students. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 1(2), 187-197. [ Links ]

Ståhl, C. (2016). Placing people in the same room is not enough: An interprofessional education intervention to improve collaborative knowledge of people with disabilities. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 331-337. [ Links ]

Stevens, L. F., Getachew, M. A., Perrin, P. B., Rivera, D., Plaza, S. L. O., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2013). Factor analysis of the spanish multidimensional attitudes scale toward persons with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 58(4), 396-404. [ Links ]

Symons, A. B., McGuigan, D., & Akl, E. A. (2009). A curriculum to teach medical students to care for people with disabilities: Development and initial implementation. BMC Medical Education, 9(1), 1-7. [ Links ]

Ten Klooster, P. M., Dannenberg, J. W., Taal, E., Burger, G., & Rasker, J. J. (2009). Attitudes towards people with physical or intellectual disabilities: Nursing students and non-nursing peers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(12), 2562-2573. [ Links ]

Tindall, D. (2013). Creating disability awareness through sport: exploring the participation, attitudes and perceptions of post-primary female students in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 32(4), 457-475. [ Links ]

Tracy, J., & Graves, P. (1996). Medical students and people with disabilities: A teaching unit for medical students exploring the impact of disability on the individual and the family. Medical Teacher, 18(2), 119-124. [ Links ]

Tracy, J., & McDonald, R. (2015). Health and disability : Partnerships in action. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28, 22-32. [ Links ]

Tur-Kaspa, H., Weisel, A., & Most, T. (2000). A multidimensional study of special education students’ attitudes towards people with disabilities: A focus on deafness. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 15(1), 13-23. [ Links ]

Uysal, A., Albayrak, B., Koçulu, B., Kan, F., & Aydin, T. (2014). Attitudes of nursing students toward people with disabilities. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 878-884. [ Links ]

Van Boxtel, A. M., Napholz, L., & Gnewikow, D. (1995). Using a wheelchair activity as a learning experience for student nurses. Rehabilitation Nursing, 20(5), 265-272. [ Links ]

VanPuymbrouck, L., & Friedman, C. (2019). Relationships between occupational therapy students’ understandings of disability and disability attitudes. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 27(2), 1-11. [ Links ]

Velonaki, V. S., Kampouroglou, G., Velonaki, M., Dimakopoulou, K., Sourtzi, P., & Kalokerinou, A. (2015). Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and behavior toward deaf patients. Disability and Health Journal, 8(1), 109-117. [ Links ]

Vignes, C., Godeau, E., Sentenac, M., Coley, N., Navarro, F., Grandjean, H., & Arnaud, C. (2009). Determinants of students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 51(6), 473-479. [ Links ]

Wagner, A. K., & Stewart, P. J. B. (2001). An internship for college students in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation - effects on awareness, career choice, and disability perceptions. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 80, 459-465. [ Links ]

Westbrook, M. T., & Adamson, B. J. (1989). Knowledge and attitudes: aspects of occupational therapy students’ perceptions of the handicapped. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 36(3), 120-130. [ Links ]

Whiteley, A. D., Kurtz, D. L. M., & Cash, P. A. (2016). Stigma and developmental disabilities in nursing practice and education. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(1), 26-33. [ Links ]

Willis, D. S., & Thurston, M. (2015). Working with the disabled patient: Exploring student nurses views for curriculum development using a swot analysis. Nurse Education Today, 35(2), 383-387. [ Links ]

Received: April 09, 2020; Revised: July 14, 2020; Accepted: July 24, 2020

text in

text in