1 Introduction

The multiple challenges related to financial independence have motivated fundamental changes within education, investigation and policies. Several milestones mark the progressive attention to financial literacy. With the beginning of the Project of Financial Education, by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the later inclusion of financial literacy in the Programme for International Student Assessment (OECD, 2013) and the current updated Recommendation of the Council on Financial Literacy, which takes into account the needs of groups “with physical or mental disabilities”, financial education has been universally recognised as a key element in financial and economic development and stability (OECD, 2021).

Several factors still limit the access and development of financial literacy, however, especially in vulnerable groups, as people with disabilities. One of the key factors is linked to poverty and low opportunities for employment, which limits options and access to financial products (Maroto & Pettinicchio, 2020). Moreover, complex information and procedures, alongside a deficit of easy and accessible information, seem to increase the need for help and support from a third person, which further reduces the ability of such groups to control their own finances (Abbott & Marriott, 2013).

These inequalities require multiple actions in the services of support, social security, employment or financial and educational systems. Within education, teaching financial competencies is becoming central to support post-school transition (Clark, 2016), as well as a target of continuous learning throughout adulthood (Henning & Johnston-Rodriguez, 2018). Indeed, financial literacy is associated with a sense of ownership, community interaction and social roles that drive the support services for inclusion (Fundação Dr. António Cupertino de Miranda, 2021). Low financial literacy has been linked to financial and social exclusion, while the contrary leads to better financial decisions and consequently to social engagement (Williams et al., 2007).

Despite this consensus, a holistic and transversal framework for financial education programmes for people with disabilities is still needed. The development of the Core Competencies Framework on Financial Literacy for Youth (OECD, 2015) laid the foundation of the core skills for youth transitioning to adult life, but the four content areas need to be adapted to meet the specific needs of people with disabilities, either by being too complex or not fully covered, such as social justice or self-advocacy skills (Williams et al., 2007). Overall, there is an extensive bibliography on this subject that stretches for decades. Available information includes multiple approaches and sources of diverse entities and scopes, from the implementation of specific inclusive pedagogy approaches – like Universal Design Learning and culturally responsive curriculum principles (Henning & Johnston-Rodriguez, 2018) – to the training of very specific financial-related skills – like purchasing skills (Xin et al., 2005). An analysis of science-based full programmes that include goals, contents and teaching strategies covering or combining the focus on different core competencies of financial literacy is still missing. That advance is of critical importance to inform the development of structured approaches to financial literacy in inclusive education systems or services. In this study, the meaning of full programmes is aligned with the complexity of the construct of financial literacy acknowledging a wide range of knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours as target-outcomes.

A comprehensive and systematic search targeting at full financial education programmes for youths and adults with disabilities – that is, not recommendations, resources or exercises that are either generic or specific to a topic – would provide a first step to identify how the extensive literature has been translated into programmes that are currently available through scientific search methods and that are ready to be used and empirically replicated, hence contributing to the advance of such programmes. To our knowledge, no comprehensive search aimed at finding the gaps in this evidence has been conducted. For these reasons, we conducted a scoping review, with a systematic search to maximise results, that sought to identify: What are the core goals, contents, approaches, gaps and limitations currently found in evidence-based full financial education programmes for youths and adults with disabilities?

2 Methods

Given the exploratory nature needed to retrieve intervention programmes, we conducted a scoping review (Sutton et al., 2019), following previous recommendations (Colquhoun et al., 2014) and criteria from “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews” (Tricco et al., 2018). We performed a three-step systematic search (Khalil et al., 2016) to minimise exclusion of relevant publications and improve comprehensiveness, following Joanna Briggs Institute and Cochrane recommendations (Aromataris & Munn, 2020; Higgins et al., 2022). No protocol was found or developed for this scoping review.

To improve comprehensiveness, we included all publications describing the content or approaches of a full financial education programme for youths and adults with disabilities (i.e. we did not restrict our search to any specific disability), regardless of time or methodology (e.g. review, trial or “grey” literature), if they were found in scientific databases, peer-review journals or entities involved in financial education (e.g. government institutions, foundations, universities or national task forces). We included publications written in English, as well as in Portuguese for the authors’ convenience and to maximise results. We excluded all publications that were developed by non-official scientific or government entities, were focused on specific areas of financial-related skills, did not clearly described any intervention contents or methods, did not target youths and adults with disabilities or were not accessible to the authors upon request.

2.1 Search strategy

In the first stage, we conducted a limited online search in Scopus (in English) and B-On (in Portuguese) to screen for key terms used in the title and abstract. We sought terms that could be representative of the two key concepts of this review scope: financial education and people with disabilities. Although some terms are currently deprecated, they were included so as not to exclude older publications. Specific search terms were used only to maximise results.

In the second stage, the three authors agreed with the search strategy described below. The first author conducted an online systematic search in December 2020 using the previously selected search terms in B-On, Cochrane Library, EBSCOhost, Scopus and Web of Science. Search terms were aggregated in a query with the following structure: “(“cognitive impairment*” OR “cognitive problem*” OR “developmental disability” OR “general learning disability” OR “intellectual disability” OR “learning disability” OR “mental retardation” OR “people with disabilit*” OR “special need*” OR “youth with disabilit*”) AND (“budgeting skill*” OR “financial behavi*” OR “financial capabilit*” OR “financial capacit*” OR “financial education” OR “financial knowledge” OR “financial literacy” OR “financial skill*” OR “financial wellness” OR “foney skill*”)”. The query was adapted to match the syntax for each database and wild card characters were used if possible. The query was applied in “any fields” (i.e. keywords, topic terms, MeSH terms or filters were not used) to better conform to the multiple terminology changes. All search results were imported to Mendeley Desktop (version 1.19.8) and duplicates were excluded.

In the third stage, results were screened by title and abstract for full-text analysis. The three authors included additional results identified in full-text analysis, exploratory Google searches and full-text requests. The final list of results was agreed by consensus.

2.2 Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Full-text analysis for data extraction was conducted independently by the first and second authors and later discussed by all authors with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Extracted data were organised for presentation in narrative form and in Table 1 as a summary of the characteristics of the included studies, which included: author and year, report type, objective, participants and programme evaluation. Major goals and contents are distributed in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, which for presentation purposes were consistently brought closer to the OECD’s Core Competencies Framework (OECD, 2015). Approaches and strategies are organised in Table 5, as inferred from the programme implementation methods, rather than being clearly stated. Considering the high variability of the methods and the preliminary mapping of the nature and extent of the research evidence, no formal quality assessment was conducted.

Table 1 Summary of the characteristics of included studies

| Author and year | Report type | Objective | Participants | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartmeyer (2015) | Thesis | To create, apply and evaluate the programme “Conhecer e Utilizar o Dinheiro” [Know and Use Money]. |

Programme for intellectual disabilities. Programme implemented with 8 students (19–29 years) with disabilities in an institution. |

Results and content were assessed by 5 field teachers. |

| Caniglia and Michali (2018) | Article | To describe a financial literacy course for transition-aged persons with intellectual disabilities. |

Programme for intellectual disabilities. Programme implemented with 25 students in a four-year transition programme. |

Teacher assessments after every unit for self-determination and financial skills. Participants’ portfolios and surveys. Parent focus groups. |

| Hordacre (2016) | Grey | To identify the key issues, approaches and competencies for a financial literacy programme for youth with disabilities. | Young people with disabilities. |

Multiple entities engagement in the assessment, such as students, family, teachers. Analytic: focused on a competency to be achieved. Holistic: overall satisfaction and quality. |

| National Disability Institute (2020) | Website | To provide free tools that can help individuals, families, financial institutions and community partners improve the financial future of people with disabilities. | People with disabilities. | Not applicable. Self-assessment as alternative. |

| Neves (2016) | Thesis | To create and implement a programme to promote mathematics skills (money, mass, time and capacity) for independent living. | Programme for intellectual and developmental disabilities. Programme implemented with one participant with intellectual and developmental disabilities (19 years) in school setting. |

Observational rating scales per session objectives. Real context situation in a supermarket. |

| Oliveira (2018) | Thesis | To create and implement a programme to promote mathematics skills for money transactions. |

Programme for special educational needs. Programme implemented with one participant with Williams Syndrome (16 years) in school setting. |

Observational rating scales per session objectives. Real context situation in a supermarket. |

| The Money Advice Service (2013) | Grey | A toolkit for helping young people with learning disabilities to understand money. | Programme with materials adapted for young people with learning disabilities. |

Table 2 Major included goals and contents for money and transactions

| Financial literacy topics | Goal and contents of the included programmes | Bartmeyer (2015) | Caniglia and Michali (2018) | Hordacre (2016) | National Disability Institute (2020) | Neves (2016) | Oliveira (2018) | The Money Advice Service (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Money | The history of money. | X | ||||||

| Understanding the function and use of money. | X | X | ||||||

| Identifying real-life money situations. | X | X | X | |||||

| Solving real-life money situations. | X | |||||||

| Identifying things that cost money. | X | |||||||

| Identifying myths about money. | X | |||||||

| Self-determination towards more rewarding financial behaviour. | X | X | ||||||

| Euro symbol identification. | X | |||||||

| Number recognition. | X | |||||||

| Identification of coins and notes. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Matching coins, notes and values. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Matching coin and note sizes with their value. | X | |||||||

| Counting money. | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Counting available money. | X | |||||||

| Skip counting money. | X | X | ||||||

| Sorting coins, notes and values. | X | X | ||||||

| Zero, whole and decimal value recognition. | X | X | ||||||

| Zero, whole and decimal value calculation. | X | |||||||

| Addition and subtraction of coins, notes and values. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Price percentage calculation. | X | |||||||

| Understanding place value. | X | |||||||

| Value decomposition. | X | X | ||||||

| Missing value calculation. | X | |||||||

| Income | Identifying typical sources of income and expenses. | X | X | |||||

| Payment and purchases | Identifying different forms of payment methods. | X | X | |||||

| Self-awareness of own behaviours. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Confidence in making choices. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Purchasing procedures. | X | X | X | |||||

| Price identification in supermarket flyers. | X | X | ||||||

| Searching and registering prices of products. | X | |||||||

| Realistic knowledge of basic items. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Price comparison. | X | |||||||

| Selecting a list of products based on price, intention or available money. | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Change calculation. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Total and unit price calculation. | X | X | X | |||||

| Using supportive technology (calculator). | X | |||||||

| Purchasing from a shopping list. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Understanding receipts. | X | |||||||

| Identifying products on sale. | X | |||||||

| Applying discount to final price. | X | |||||||

| Finding cheapest product. | X | |||||||

| Calculating maximum quantity that can be purchased with available money. | X | |||||||

| Calculating remaining money after transaction. | X | |||||||

| Finding price per kilo. | X | |||||||

| Credit and debit card procedure. | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cheque procedure. | X | |||||||

| Financial records | Understanding card balance. | X | ||||||

| Reading bank account movements. | X | |||||||

| Depositing notes and coins. | X |

Table 3 Major Included Topics for Planning and Managing Finances

| Financial literacy topics | Goal and contents of the included programmes | Bartmeyer (2015) | Caniglia and Michali (2018) | Hordacre (2016) | National Disability Institute (2020) | Neves (2016) | Oliveira (2018) | The Money Advice Service (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budgeting | Understanding the relevance of budgeting. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Understanding budgeting as a tool and needed skill. | X | |||||||

| Planning a shopping list. | X | X | ||||||

| Managing income and expenditure | Knowing the difference between needs and wants. | X | X | X | ||||

| Knowing how to deal with not being able to get everything. | X | |||||||

| Decision making about where to spend and save. | X | |||||||

| Keeping a spending plan and diary. | X | |||||||

| Establishing priorities of where to save and spend money. | X | |||||||

| Saving | Understanding the importance of saving. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Identifying behaviours associated with saving. | X | |||||||

| Understanding saving as a way to reach objectives. | X | |||||||

| Longer-term planning | Knowing the importance of saving for retirement. | X | ||||||

| Establishing planning goals. | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Planning and saving according to income. | X | |||||||

| Planning and saving according to personal goals. | X | |||||||

| Managing money for future outcomes. | X | |||||||

| Taking informed investment decisions. | X | |||||||

| Credit | Understanding the concept of buying with credit. | X | ||||||

| Understanding the concept of debt. | X |

Table 4 Major included goals and contents for risk and reward and financial landscape

| Financial literacy topics | Goal and contents of the included programmes | Bartmeyer (2015) | Caniglia and Michali (2018) | Hordacre (2016) | National Disability Institute (2020) | Neves (2016) | Oliveira (2018) | The Money Advice Service (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk and reward | Identifying risky situations. | X | ||||||

| Understanding insurance and stocks. | X | |||||||

| Financial landscape | Knowing where to find trustworthy information. | X | ||||||

| Knowing where to find help for a range of problems. | X | |||||||

| Understanding rights and responsibilities. | X | |||||||

| Understanding information provided by institutions. | X | |||||||

| Identifying common financial scams and fraud. | X | |||||||

| Having the confidence to know and apply their rights. | X | |||||||

| Knowing how to find financial and support institutions. | X | X | ||||||

| Knowing how to choose a bank. | X | |||||||

| Managing life events as a foundation for financial autonomy (employment, career, education, health and community engagement). | X | X | X |

Table 5 Major included approaches and strategies used in financial education for people with disabilities

| Approach or strategy | Bartmeyer (2015) | Caniglia and Michali (2018) | Hordacre (2016) | National Disability Institute (2020) | Neves (2016) | Oliveira (2018) | The Money Advice Service (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall structure of 10–60 sessions; 45–240 min; once per week or no limit. | |||||||

| Multiple forms of engagement, representation, action and expression. | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Problem-based learning. | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Simulated and community-based instruction. | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Age, cultural and personal relevancy. | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Family and community engagement. | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Redundancy and repetition. | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Real money and objects. | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Continuous assessments. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Group activities. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Money-related activities. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Provide informative content. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Role-play. | X | X | X | X | |||

| Worksheets support. | X | X | X | ||||

| Identification and removal of community barriers. | X | X | |||||

| Technology support (e.g. calculator). | X | X | |||||

| Higher volume of exercises. | X |

3 Results and discussion

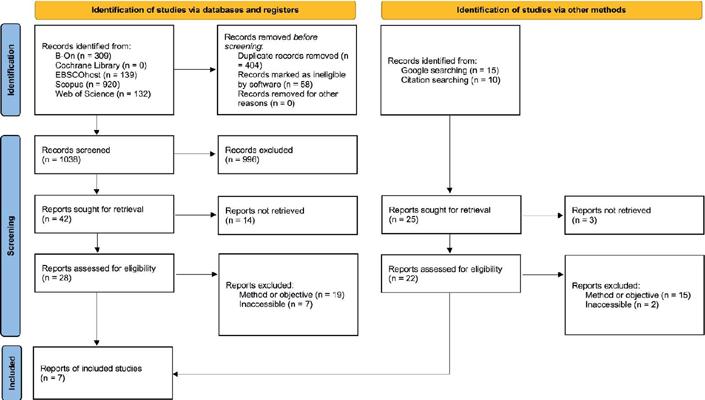

The search flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. The search strategy yielded 1,038 results. Title and abstract screening identified 42 reports for full-text analysis and citation searching, which, in parallel with a Google search, yielded 25 more reports. From the 50 eligible reports, 9 reports were excluded for being inaccessible online (e.g. upon request) and 34 reports were excluded for not clearly addressing the contents or approaches of a comprehensive intervention (e.g. having a specific approach, describing only the results but not the programme content or with participants not with disabilities).

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Adapted from “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews,” by Page et al. (2021).

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram for included studies

Thus, 7 reports were included in the Results and Table 1 (Bartmeyer, 2015; Caniglia & Michali, 2018; Hordacre, 2016; National Disability Institute, 2020; Neves, 2016; Oliveira, 2018; The Money Advice Service, 2013). If relevant, reports excluded by “method or objective” were included in the following discussion.

3.1 Overall appreciation depicts the emergence of programmes

Four overall key points are expressed in these results. First, multiple financial programmes and resources can be found, which is consistent with previous reviews that addressed the importance of this topic (Henning & Johnston-Rodriguez, 2018; Social and Enterprise Development Innovations, 2008). However, although multiple resources are available, they tend not to include all of the relevant topics, with full programmes being associated with institutions.

Second, only three of the seven included studies (Caniglia & Michali, 2018; Neves, 2016; Oliveira, 2018) were retrieved directly from our search. This might be the result of being associated with specific institutions, as mentioned above, which leads such programmes to fall outside of the scope of scientific databases. Concurrently, due to the multiplicity of topics in financial education and the lack of consensus around some of the terms, even an extensive query and systematic search does not fully represent the existing programmes.

Third, the different types of reports – one practice brief, three master’s theses, two grey publications and one website – reflect how dispersed the information is, which further reinforces the relevancy of this review. The inclusion of the master’s theses might also indicate how emergent this topic is for evidence-based programmes.

Fourth, three of the included studies are in Portuguese, which coincidentally are the master’s theses. We included these reports for convenience (i.e. we declare no association), as the language and database search included national repositories. They significantly increased the content of this review, as they include the full rationale and content of the programmes discussed. National specificities should be considered when addressing this issue.

3.2 Covered goals and contents are asymmetrically distributed

Participants of the included studies were mentioned with the following descriptions: intellectual disability, intellectual and developmental disabilities, special education needs, learning disabilities and people with disabilities. Although we aimed for full programmes without specifying any type of limitation, all of the included studies tended to address mental functions and its limitations.

Known social, economic and physical barriers are mentioned and considered, but not as exhaustively as intellectual barriers. Indeed, intellectual access to financial literacy competencies, numeracy, functional mathematics (Faragher, 2019) and money skills (Browder & Grasso, 1999) are considered foundations for the complex acquisition of financial literacy, and are expressed as primary and more achievable objectives. As a result, the goals and contents for money and transactions are mentioned significantly more often than all of the remaining topics.

3.3 Goal and contents for money and transactions focus on money and pa yment skills

Money and transaction contents tended to focus on the function and symbolic meaning of money – understanding that notes and coins have financial value and can be exchanged by goods and services – and also on recognising and counting money for purchases (Table 2). This is the content most consistently found in the literature, with multiple adaptations (e.g. counting-on, next-dollar or one-more-than strategies), further reviewed by Browder and Grasso (1999) and Xin et al. (2005), which might represent an attempt to match the heterogenous learning and support needed. For example, for counting money, included activities can involve the concept and arithmetic procedure of counting money, how to use a calculator or even understanding that money is a way to get things (Browder et al., 2008).

Using real-life situations is a common characteristic that seems fundamental to the development of financial literacy independence at different levels of proficiency. Simulated and community-based instruction allowed participants to use an automated payment (Mechling et al., 2003) and teller machine (Cihak et al., 2006) or to make purchases using a debit card (Rowe & Test, 2013). Teaching functional mathematics should also include solving real-life problems using training, repetitive instructions and self-confidence (Butler et al., 2001), with possible generalisation (Xin et al., 2005).

3.4 Goals and contents for planning and managing finances are fundamental for independence and autonomy

The core contents of planning and managing finances are related to understanding its relevance according to personal goals, needs and desires (Table 3). This is consistent with the previous literature, where these topics represent key indicators for independence and autonomy in financial participation (Henning & Johnston-Rodriguez, 2018). Specific issues were also reported. Budgeting and saving concepts might be to complex when mathematics skills are not consistent (Root et al., 2017) and, as money management is frequently done by a third person, shopping or budgeting skills might represent a significant step forward to be acquired (Williams et al., 2007).

Like money transactions, multiple adaptations are required to create a budget that considers individual competencies and objectives. Real problems allow for an understanding of fundamental concepts, such as when to save or spend money, register expenses, keep expenditures lower than income, consider unexpected expenses or consider priorities related to food, clothing, hygiene and housing. Participating in finance management develops decision-making and confidence, for both individual short and long-term objectives (Suto, Clare, Holland, et al., 2005).

The development of the planning and managing competencies was approached as a way to decrease the intensity of assistance of a third person (leading to greater independence in tasks such as making a shopping list or keeping a spending diary), and it was also closely linked with the notion of freedom of choice and control in terms of autonomy (through contents on decision making about where to spend and save or on the establishment of saving goals).

3.5 Goals and contents for risk and reward and financial landscape also focus on self-advocacy

Although less represented in Table 4 (together for presentation purposes only), self-determination, knowing where to get trustworthy information and help according to the problems, identifying risky situations and understanding rights and responsibilities are still fundamental. Money management requires multiple skills (e.g. counting money, budgeting or problem solving), concepts (e.g. money, needs or roles) and entities (e.g. organisations, banks or social services) that are overwhelming. For people with disabilities, the transition to adult life is associated with fewer opportunities, low income and higher risk of financial abuse that threat well-being and quality of life (Suto et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2007). Consistently, the included studies cover several aspects that are reported in the literature, such as active job search, decision-making when facing financial challenges and identifying different sources of income and support entities (Henning & Johnston-Rodriguez, 2018; Williams et al., 2007).

Special note should be made of the importance of self-determination, as expressed by Caniglia and Michali (2018). Maintaining competencies requires continuous use in everyday challenges. This is only possible if participants are self-aware, self-confident and resilient when advocating for their goals and rights. Therefore, the concept of self-advocacy – defined as “individuals’ ability to effectively communicate, convey, negotiate or assert his or her own interests, desires, needs and rights (…) making informed decisions and taking responsibility for those decisions” (VanReusen et al., 1994, p. 1) – is gaining an emergent importance in the design of financial literacy programmes. The emphasis on promoting the understanding of own rights and responsibilities to prevent financial abuse and exploitation is a clear example of a growing commitment of support groups to empower the disability community (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2019).

3.6 Approaches and strategies are consistently used

All of the included programmes take into consideration the broad spectrum of competencies and challenges (Table 5), following previous evidence-based recommendations (Browder et al., 2014). The most relevant example is the Universal Design for Learning (Center for Applied Special Technology, 2018), which the included studies take in account, although without clearly stating it. This represents how embedded these principles are in programmes for people with disabilities.

The Universal Design for Learning is supported by scientific research (Prais et al., 2020) and represents a methodological option for an inclusive education that recognises individual competencies, needs and limitations. Its principles with practical examples are related to multiple and flexible means for (a) engagement – for example, saving can be learned through interactive online games, choosing images that represent savings objectives or cooperative work between learners to map out and meet a personal savings goal; (b) representation – for example, contents about sources of income can be provided by exploring visual pictures or graphics, auditory and visual information by using videos or going out and visiting real work sites; and (c) action and expression – for example, learners can demonstrate their knowledge about budgeting by simulating an online budget, using interactive models and applications or making a video to teach their peers.

Problem-based learning is also considered in the included studies, particularly when focusing on the steps required to deal with open-ended solution to real problems (Servant-Miklos et al., 2019). This approach has showed positive results with young people with disabilities in academic progress – in a better integration of required knowledge into actions; personal development – in confidence, motivation, adaptability, critical thinking, creativity, leadership skills and self-empowerment; and social development – in teamwork, negotiation skills, friendship, understanding the other and community engagement (Belland et al., 2006). A practical example is buying a metro ticket at a coin-operated machine to go to school, where the learner should develop his or her knowledge of matching coin values, but also decision-making and confidence in planning the trip, where to ask to exchange money or whom to ask for help.

Simulated and community-based instruction was also represented in the including studies. Consistently transferring knowledge and skills to everyday life problems is usually accompanied by external challenges (Rowe & Test, 2013). Both strategies have advantages: natural learning in a real context facilitates generalisation, but learning in a simulated context is more predictable and allows experimentation protected from immediate consequences. On the other hand, using real and near-real situations fosters independence and self-empowerment, promoting confidence, social skills and problem-solving skills (Barczak, 2019). Practical examples include using a simulated ATM terminal with images of the menus that allow testing several steps to insert the PIN code or to withdraw cash or using real materials in an identical layout of the supermarket to allow role-play of a shopping list.

Other interrelated strategies are consistent with previous studies. All of the included studies used contents that were age, culturally and personally relevant to ensure that all learners had meaningful learning. They used redundant and repetitive training exercises that focused on using real money and objects. Higher volumes of exercises with multiple methods were used, such as individual and group activities using worksheets, money-related activities and role-play. Moreover, they showed an effort to address real community issues by promoting family and community engagement, continuous assessments, identification and removal of barriers and providing informative content. The use of technology is also worth mentioning, although not extensively represented in the included studies, as it provides a viable support to develop financial competencies, such as the calculator (Reichle, 2011), computer simulation for money management (Davies et al., 2003), debit card procedure (Mechling et al., 2003), picture and video prompts for ATM procedures (Cihak et al., 2006), spreadsheets (Faragher, 2019) or mobile applications for specific techniques (Hsu et al., 2014) and simulation (Lee & Kwon, 2016).

Other relevant approaches are worth mentioning: task analysis and schema-based instruction. Task analysis is an evidence-based practice that breaks tasks into their simplest steps. New and complex financial education skills can be sequenced into progressively or regressively learned simpler steps (Snodgrass et al., 2017). A practical example is identifying all of the steps required to withdraw money from an ATM. Schema-based instruction allows identification of the meaning, relationship and structure by which problems can be solved (Clausen et al., 2021). A practical example is providing visual support about the similar steps required to identify the correct entity for a specific question, such as bank or hospital for money or health issues.

4 Conclusions

This review sought to identify the core goals, contents, approaches, gaps and limitations of full financial education programmes for youths and adults with disabilities. A multi-term query was used for a systematic search that sought to identify available scientific-based programmes. Multiple programmes and resources can be found online, but they do not address all of the relevant contents or are out of the scope of scientific databases. Providers of financial literacy to people with disabilities also tend not to have their programmes fully available online, with the result that extensive queries and systematic searches may not identify available programmes. Therefore, the information provided by national entities should be considered when covering this topic and a discrepancy in empirical support should be expected.

Although there is an asymmetrical distribution of contents towards mental skills and money and transactions, other contents are equally relevant and should not be disregarded – such as social and physical barriers, self-advocacy, self-determination and managing finances – using adaptations as needed.

Some approaches and strategies were found consistently throughout the programmes that stem from Universal Design Learning, problem-based learning, simulated and community-based instruction. This represents how fundamental these approaches currently are in practice with people with disabilities – so programmes should be viewed as a representation of these principles, and not as a collection of multiple replicable exercises.

Some limitations and recommendations should be highlighted. Although we used a comprehensive and systematic search that was extended to generic search engines and references, the number of studies included was limited. This is a reflection of the limited number of full programmes that are available. The inclusion of a website is also a reflection of the previous conclusion, but also of the relevance of the methods for this scoping review. Here, the same main criteria were used of considering only resources that were built to fully address financial literacy for this population. It also reflects the fact that providers of financial literacy use this platform to provide content and it is a common practice in reports on this subject to share available online resources.

Following on from this, the results that were out of the scope of scientific databases were likely excluded from the results. Future reviews should specifically aim to cover these institutional programmes to complement current reviews. Empirical studies should be developed to provide evidence-based suggestions for this field, as programmes and approaches are traced back for several decades.

Overall, this review sought to contribute towards evidence-based practice and address a key issue: how the extensive decades of scientific publications result in empirical intervention programmes that can be found by science-based practitioners in scientific databases.

Ultimately, financial education programmes should consider individual characteristics to promote participation in the family and community. The balance between respect, freedom and protection for people with disabilities should be the major goal of financial education programmes.