Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.44 São Paulo 2018 Epub 31-Jan-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201712170308

Articles

The research on young people in Brazil: setting new challenges from quantitative data1

2- Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Contacts: sposito@usp.br; raqsou@usp.br; fernandarantes@usp.br

Based on an analysis of data from the National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) covering two periods (2004 and 2014), this article explores changes and continuities in the situation of youths in the fields of education, labor and family life. At the same time, it attempts to clarify how these dimensions of life are experienced in different manners by young males and females, and according to criteria such as age, race/color and family income. This exercise is taken into consideration so that this study may outline, even if preliminarily and exploratorily, new challenges for the research on what it is like to be a young person in Brazil today. This agenda includes an effort to understand how socio-economic changes brought about during the last decade, as well as their more recent reversal, unfold into the experiences of the current young generation, both in terms of a whole set of new expectations and in challenges to fulfill such aspirations. Another highlight is the need for a wary way of understanding these individuals in their life paths, their lifestyles, the challenges they share and how they react to them at this specific moment of their lives.

Key words: Youth; Social change; Education; Labor; Family life

A partir de análise da Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra Domiciliar (PNAD), abrangendo dois períodos (2004 e 2014), este artigo explora mudanças e permanências na situação de jovens nos campos da educação, do trabalho e da vida familiar. Ao mesmo tempo, explicita como essas dimensões são experimentadas de modo variado por moças e rapazes e segundo clivagens como idade, raça/cor e renda familiar. É considerando esse exercício que se busca delinear, ainda que em caráter preliminar e exploratório, novos desafios para a pesquisa sobre a condição juvenil e os jovens brasileiros. Faz parte dessa agenda a compreensão sobre como as mudanças socioeconômicas experimentadas na última década, bem como sua recente inflexão, declinam na experiência da atual geração de jovens, seja em termos de um conjunto de novas expectativas, seja em desafios para satisfação de tais aspirações. Por outro lado, destaca-se a necessidade de uma perspectiva atenta à compreensão desses indivíduos em suas trajetórias, de seus modos de vida, dos desafios comuns que lhes são propostos e do modo como são por eles respondidos nesse momento do percurso de vida.

Palavras-Chave: Juventude; Mudança social; Educação; Trabalho; Vida familiar

The contribution to the production of new knowledge about youths in Brazil constitutes a collective effort involving a wide array of researchers, as well as varied strategies. A prolific path has been the production of works on the state-of-the-art, and also literature surveys, because they contribute both to the emergence and to the structuring of fields of knowledge (SIROTA, 2006; SPOSITO, 2009, 2002). This article, however, takes a different route, presenting in a preliminary and exploratory manner themes and possible problems for research based on a descriptive analysis of results of the National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) related to two moments (2004 and 2014) of the population of youths in Brazil situated within the age bracket of 15 to 29 years.23

An important debate about educational research in Brazil took place from the 1980s around the so-called qualitative methods (case studies, ethnographies, life histories, among others). It had to do with finding ways that would lead to alternatives to the hegemony of quantitative approaches based on statistical procedures. That was a productive debate because from the attitude of open opposition between those two perspectives there arose a growing consensus about the importance of both, and about their mutual complementarity in the production of new knowledge, which tended to see them as a matter of scales (BRANDÃO, 2008).

The approach we put forward here is inspired in a perspective presented by Robert Stake – one of the pioneers of qualitative studies in education – in a seminar given in Brazil in 1982. He situated in the original and in the first studies that made use of a qualitative approach the importance of case studies as a preliminary moment to the large surveys. The localized investigations examined in depth different realities that could engender new anxieties and problems to be incorporated in the assessments carried out by the large-scale national surveys (STAKE, 1982).

Conducting a brief exercise of sociological imagination (MILLS, 1965), we have inverted such strategy in the present article, resorting to statistical data to problematize and open up a range of questions that demand new investigations. We consider that these quantitative data present a set of themes capable of stimulating reflection, so as to feed qualitative research with new problems and, above all, to widen the production of knowledge about youths in Brazil.

Even recognizing the limits of the longitudinal dimension of the data presented here, which covers a period of only 10 years, we notice that there is a group of change-signaling events whose intensity remains to be gauged, and that deserve to be carefully investigated. Only a few of the variables have been selected – labor, education, and family life –, to line up new challenges for the research taking into account that a panoramic view of Brazil certainly presents limitations due to social and regional inequalities, to the varying degrees of urbanization, and to the different living conditions in the countryside and in the cities.

Singularities in the studies about youth in Brazil

Regarding the studies about youth conducted in Brazil, it was necessary to establish at the outset certain dialogue with the international production in order to identify some singularities. Hence the use of the expression youths as a metaphor to denote diversities and inequalities.

Within this wide range of specificities, we find as relevant to the discussion proposed here the intricate relationships that youths maintain with their schooling and with the world of labor in Brazil. Although Emilio Fanfani (2000) already pointed out in the early 2000’s that school constituted youth, both in its withdrawal from the world of labor and in the creation of a relatively autonomous world that contemplated specific forms of sociability among peers, of consumption, leisure and use of free time, these characteristics alone could not possibly account for the juvenile condition in Brazil.

Without denying the important spaces for life management among youths afforded by the school, it would be important to retain the notion that, by offering a more recent process of extension of schooling, the school world received during the last years countless students that had already experienced juvenile life in spaces of leisure and consumption outside the school environment. In other words, in Brazil school “did not make youth” (DAYRELL, 2007).

Other issues have always been present in the relationship between youths and school, a relationship that was characterized as intermittent by Felícia Madeira (1986) still in the 1980s. The processes of early exclusion from the school system, particularly among the popular segments, have not brought about in the last 50 years an irreversible situation for part of those who had access to the school. Comings and goings, delaying of schooling until later moments in life, including adult age, have always been present in Brazilian society, making it difficult to establish, under a process point of view, definite markers for the end of schooling.

Alongside this situation, another important piece of dynamics shows our singularities, and is present in the relationship of youths with the world of labor, to the extent that it was possible to say that in Brazil “labor makes youth” (SPOSITO, 2005), considering the inescapably early presence of this category in the experience of children and youths from the popular segments of society.

Scholars have agreed that during the last 15 years important changes have been observed in Brazil concerning the expansion of access to school, particularly to higher education, intensified by affirmative actions both in public schooling and in the private sector following policies such as PROUNI and FIES (ALMEIDA, 2014). On the other hand, a rejuvenation of the population attending secondary education is being recognized (SPOSITO; SOUZA, 2014), as well as their progressive separation from the world of labor associated to the increase in employment rates and family income (MENEZES FILHO, 2015).

Other changes will be observed, both in marriage rates and in the constitution of progeny within the youth segment, but also covering other lifestyles, and leisure and consumption habits.

We have to admit, nevertheless, that the brief period of growth was succeeded by an unprecedented economic and political crisis in Brazil, especially since 2013 (FLEURY, 2013). Although the depth of the reversal of some of the social conquests is still unclear, we have to consider that the youth segment will bear an important part of the effects of such adverse situations. Faced with the attitudinal inconsistency that has plagued a large part of society (ARAUJO; MARTUCCELLI, 2011), intensified in moments of political and economic crisis, and translated into the fear of losing recently acquired positions, it is not reasonable to suppose that the observed changes will necessarily mean a return to previous levels. Alterations in the access to the school system will not be totally reversed, despite the deep inequalities to be observed in the world of labor and occupations. The production of new expectations of consumption, changes in gender relationships, the search for the recognition of race-ethnic identities and sexual-affective orientations, the increment in more egalitarian forms of social interaction in the public space in order to establish the acceptance of differences, all these changes will not be easily eliminated and may be translated into new demands and social conflicts.

In view of this complex picture, and seeking directions for the studies about youths in Brazil, we chose to establish a few age marks in order to delve into the singularities that affect the different moments of the life trajectory, rescuing their process dimension. The data collected are situated mainly in the dimensions of schooling, labor, marriage and children, explored in three moments: questions related to adolescence (15 to 17 years old); major axes that mark the life trajectory in the age group between 18 and 24; and questions that arise closer to the age group between 25 and 29, including challenges related to the transition into adult life.

The changes within the young population in Brazil, in the periods investigated here, are important indicators to the understanding of alterations in the demographic structure of the country. In 2004, the age group between 15 and 29 years of age had 49.6 million Brazilians, whereas ten years later there had been a decrease of a little over 700,000, resulting in 48.9 million youths.

The youths between 15 and 17: the growing centrality of school

Researchers in education hardly disagree among themselves about the fact that since the latter half of the 20th century one of the most noticeable characteristics of the Brazilian educational system consisted in its rapid expansion. Throughout Brazil the period witnessed the expansion of opportunities of schooling for the whole of Brazilian population, notably for the younger segments of society, which gained access to what are today identified as stages of basic education. There followed the universalization of access to fundamental education, the massification of the offer of secondary education, and an expressive increase in the overall number of students in the country (HASENBALG, 2003; RIBEIRO; CENEVIVA; BRITO, 2015).

The statistics considered here point to a continuity of this movement which, at least as a trend, has led Brazilians between the ages of 15 and 17 to access and remain at school. In 2004, 81.8% of individuals within the age group attended an institution of education; ten years later, in 2014, this number had increased to 84.3%. In view of this situation, it is possible to say that the construction of knowledge about the juvenile situation and experiences of girls and boys between the ages of 15 and 17 is increasingly related to what they experienced at school and to the tensions of living in the situation of a student, which does not entail subsuming their experiences to the strictly school and schooling dimension.

The increase of the proportion of students among teenagers occurred for the whole of the population, but the period saw the more substantial incorporation of individuals whose profiles have appeared in studies as more strongly affected by phenomena that lead to school exclusion: poor, black male youths (DAYRELL; JESUS, 2013; UNICEF, 2014). During this decade, it was mainly among youths coming from the 20% poorest families that we observed the most expressive growth in the proportion of students, with a positive variation of 10.6 points. Although less intensely, a similar movement took place among the black population and among male youths, pointing towards the confronting of educational inequalities.

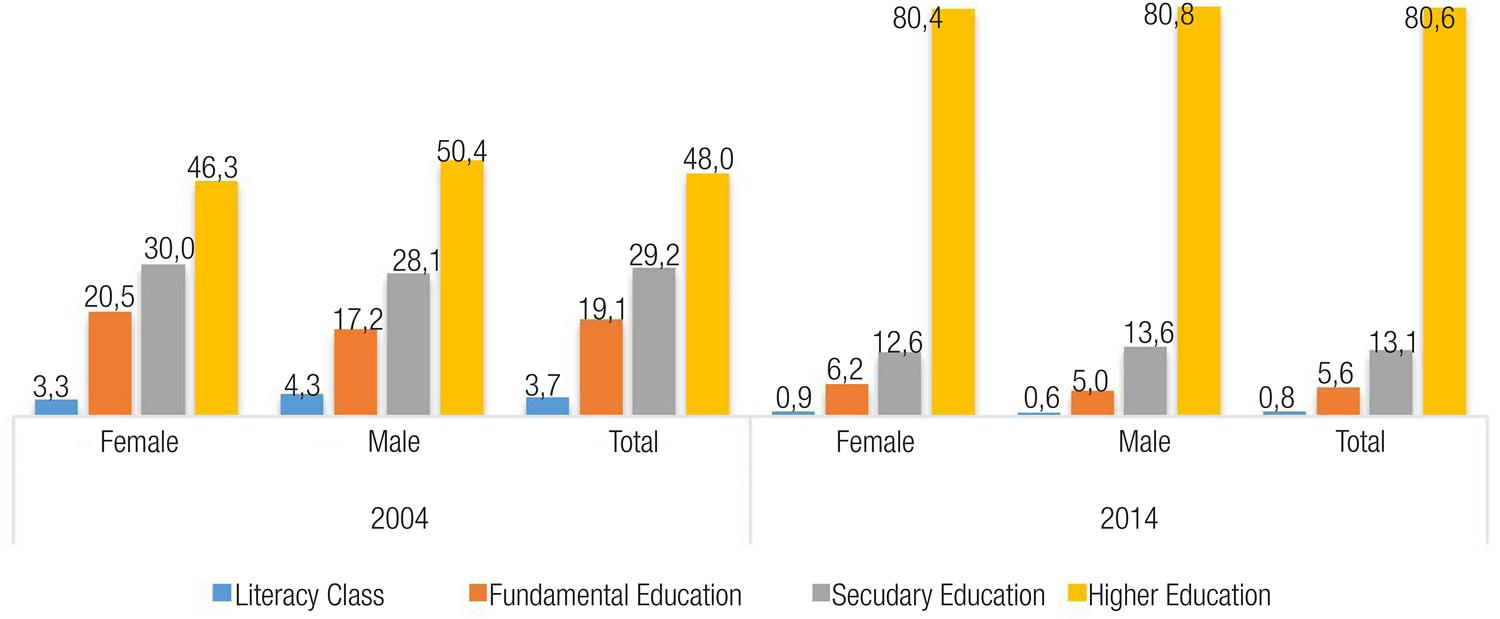

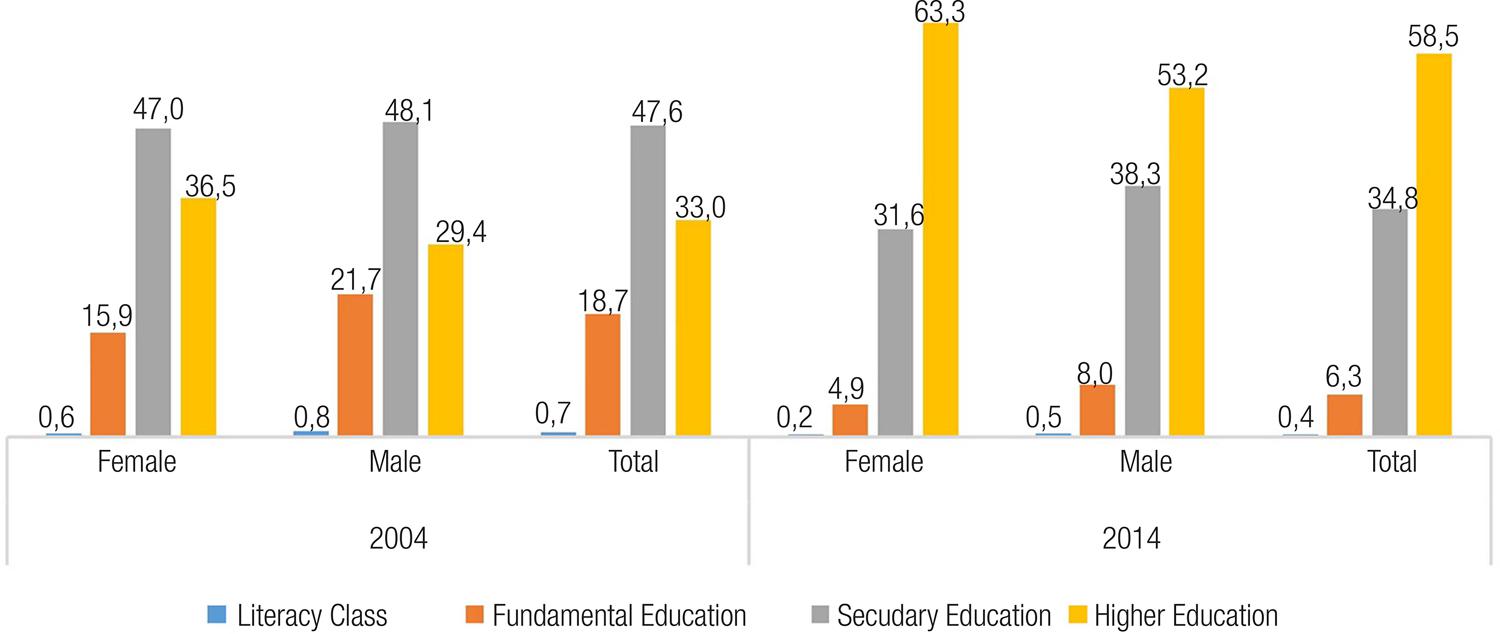

On the other hand, data from the PNDAs still display the existence of just over 1.6 million Brazilians between the ages of 15 and 17 (15.7%) who in 2014 did not attend school, among which only 20.3% had finished basic education. Also, in the case of students, one can still observe the persistence of uneven school trajectories, possibly marred by experiences of failure or marked by an intermittent relationship to the school. Notwithstanding the fact that the period displays an improvement in the indicators of school flow, at the end of the decade in question, only 67.2% of students within that age group were attending secondary education, the school level considered ideal for this population (Chart 1), a situation strongly characterized by asymmetries of income, race/color and sex.

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

Chart 1 – Percentage of students between the ages of 15 and 17 according to level of education they attended, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

The rates of dropout and of school flow constitute relevant indicators to understand the educational trajectory of youths. However, as more girls and boys managed to remain within the educational system, understanding their experiences and the inequalities they faced seems to demand more and more nuanced analyses. It is around this issue that Mariano Enguita (2011) calls attention to what he regards as a deeper and omnipresent reality: the generalized lack of commitment, albeit manifested in different degrees, of teenagers towards school and school knowledge. At the same time, he points out the effects of inequalities that warrant various ways of facing, interacting and sometimes overcoming such distancing from school daily lives and practices. Such considerations indicate a higher centrality of the relevance of the meanings attributed by youths to the school and to school knowledge and, also, to the unequal conditions they face when positioning themselves within an increasingly heterogeneous and stratified education system.

With regard to inequalities, within the sociology of youth and of education, the insertion of youths from the popular segments in the world of labor figured with relative centrality to apprehend the experiences of students in public schools. And, in this respect, there is no denying that work remains an important dimension in the lives of girls and boys within the ages of 15 and 17. In 2014, 16.4% of youths within this age group had to balance studying and working, and 5.7% dedicated themselves exclusively to work. In absolute numbers, they form a group of some 2.3 million workers, amongst which 50.4% worked without legal protection and 36.9% worked 40 hours a week or more.

Considering that it is within this group that we find the segment of the population for whom work can only be legal within rather specific and protected situations, these two aspects give us indications of labor relations marked by precariousness, whose features still have to be better understood by sociological research.

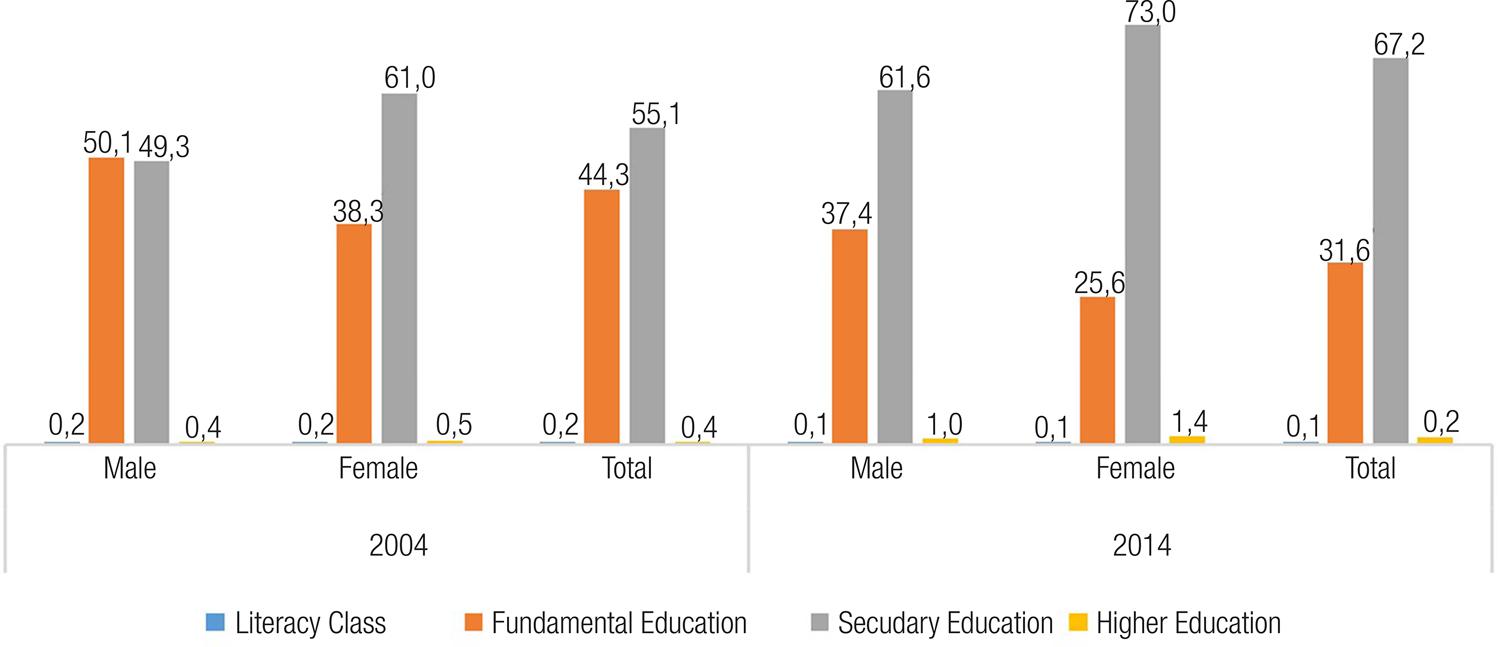

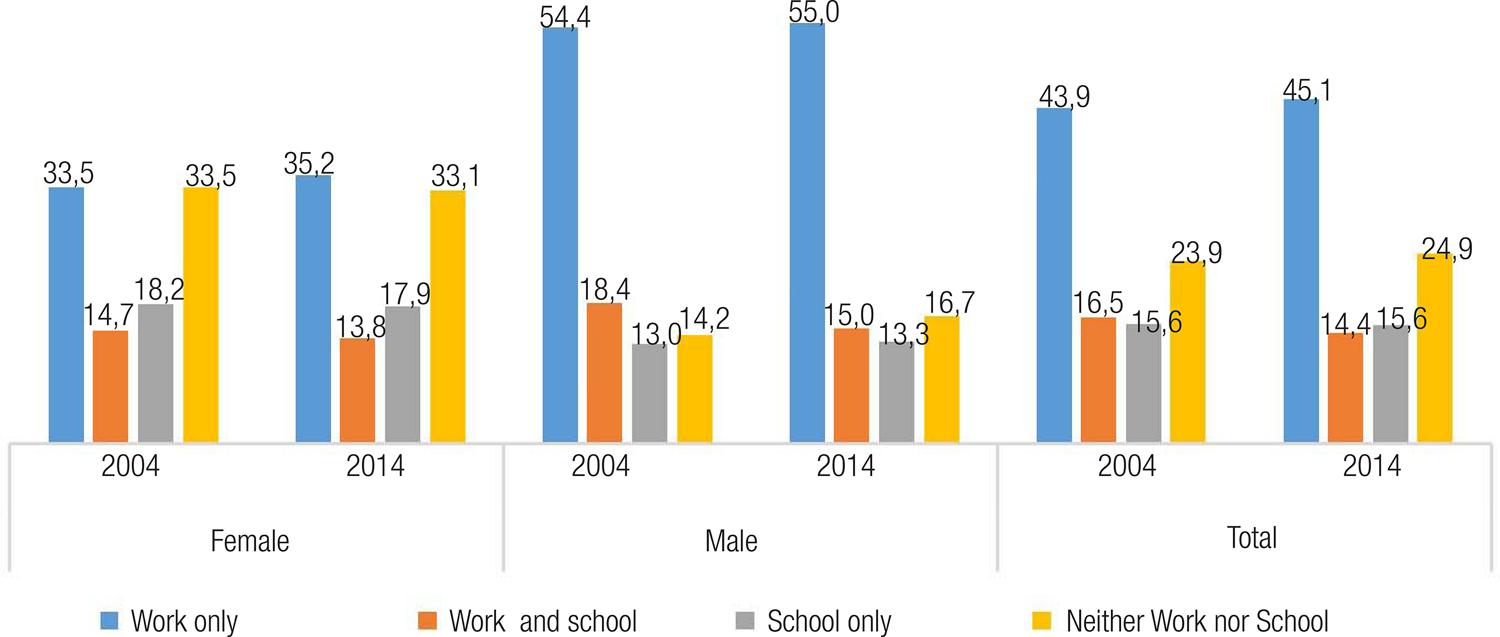

However, even if engaging in work activities is still a relevant dimension in the lives of teenagers, national statistics have for some time now pointed to a progressive distancing of youths between the ages of 15 and 17 from the world of labor. This movement is still marked by asymmetries but, compared to their older contemporaries or to youths from other generations, the current cohort of Brazilian teenagers have, at least as a trend, the school as their main institutional link. In 2004, 60.0% of them dedicated themselves exclusively to studying, a situation that in 2014 extended to 67.9% (Chart 2).

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

Chart 2 – Percentage of youths between the ages of 15 and 17 according to the activities they conducted, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

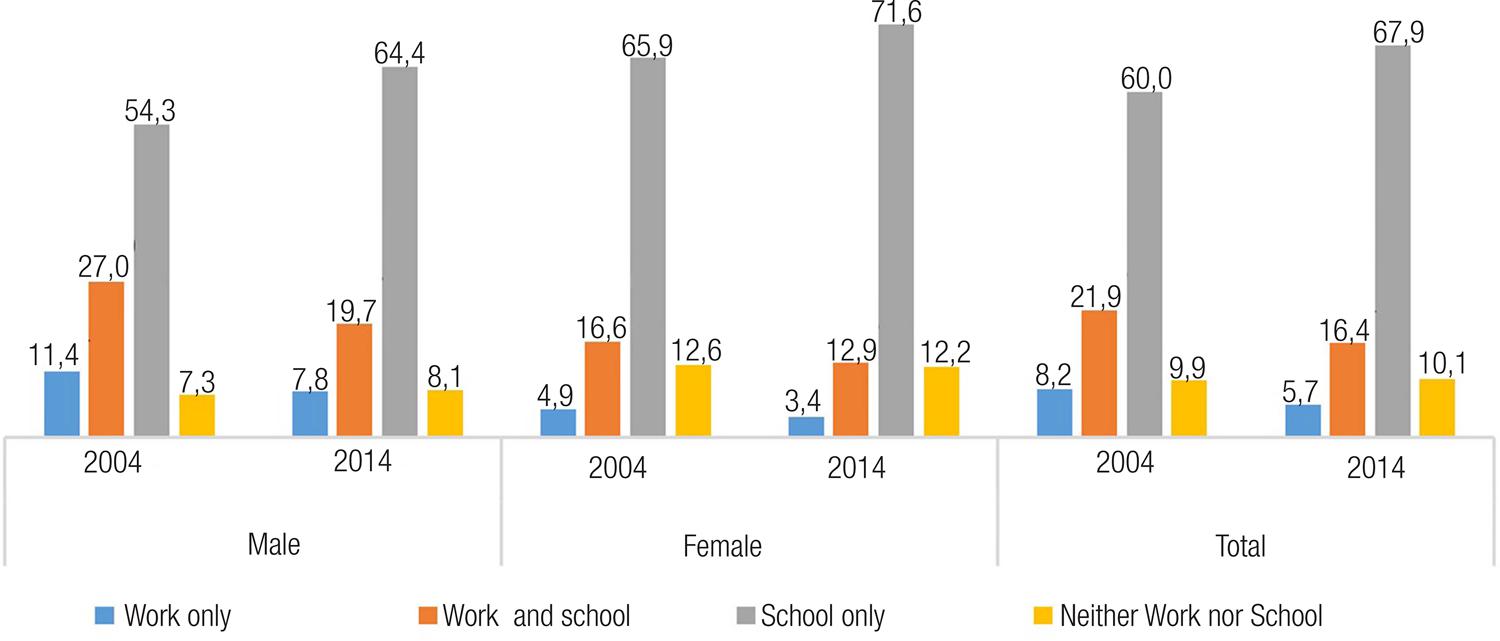

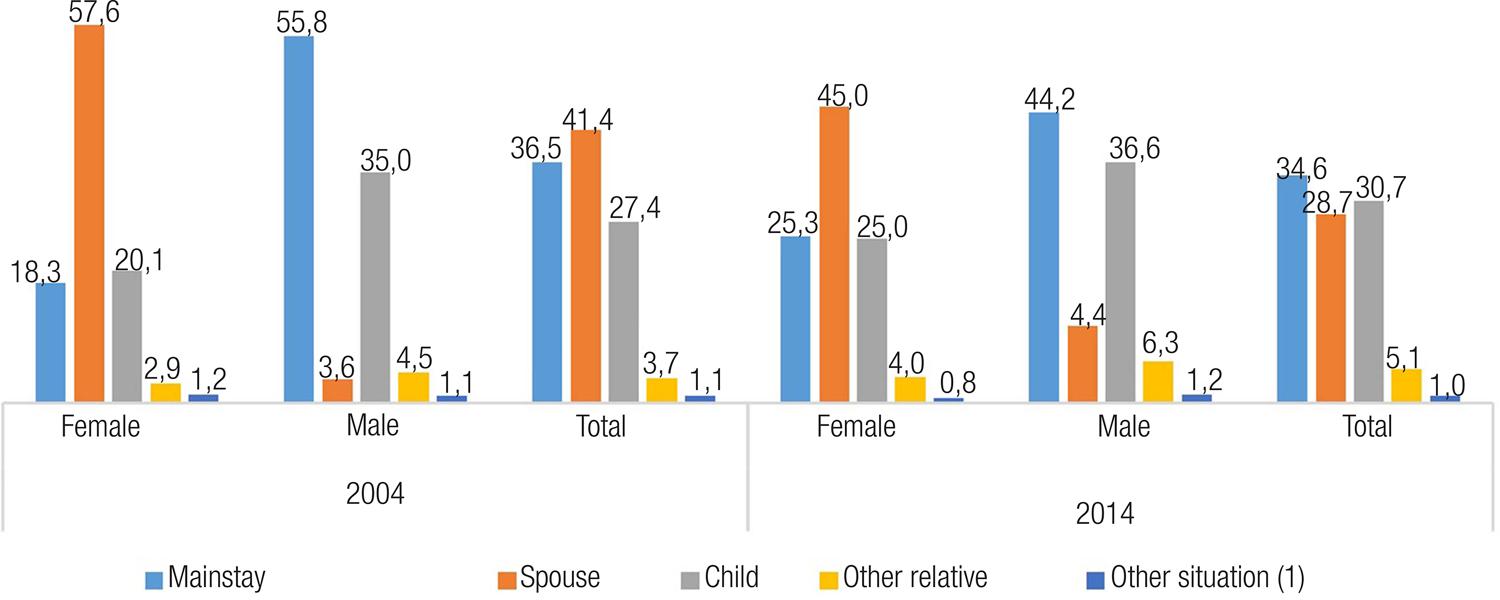

According to a study published by the Insper Institute, the economic changes during the first two decades of the 2000’s – recovery of growth, expansion of formal work posts throughout the country, policies to increase the real value of the minimum salary, greater access for the population to social programs, among others – guaranteed favorable conditions that allowed low income families to postpone the moment when there younger members, the teenagers, would enter the world of labor (CABANAS; KOMATSU; MENEZES FILHO, 2015). This correlation seems pertinent because it is particularly in this age group that youths occupied the position of children or of other relative4 in their families, positions that varied little during this decade or within different social strata (Chart 3). Faced with a relative improvement in the incomes of parents or responsible adults, it is possible to suppose that the dimension of help to the household economy, so emphasized in the studies about the generational relations in popular segments, could cease to linger about as a demand directed at the youths.

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

(1) Includes: non-relatives, pensioners, domestic workers and their relatives.

Chart 3 – Percentage of youths between the ages of 15 and 17 according to situation in the household, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

However, although the economic dimension is relevant in generational relations established within the families, it should not be taken as exclusive to the articulation between public and private spaces; nor, as argued by Robert Cabanes (2006), should families be thought outside a wider set of symbolic and cultural transformations that reconfigure the interactions established inside them. It is in this perspective that the author calls attention to the spreading, albeit in different levels, of a new regime of generational relations in families from the popular layers, less hierarchic and strongly oriented towards the schooling expectations of their younger members. It would therefore be opportune to understand how, within this context of greater horizontality of generational relations and of deep sociocultural and educational transformations, the dissonances between expectations and demands of adults and youths are being negotiated.

On the other hand, the predominant student situation among these teenagers requires an outlook that situates the dimension of the use of non-school time as a focus of new investigations. A set of practices and activities outside the school shift remains unknown, either related to occupations perceived as complementary to the school formation, often supported by the families, or relative to what youths do far and away from the control of adults; something that, in the expression of sociologist Anne Barrère, has as its regulators personal taste and choice, potentially becoming, therefore, an important arena of experimentation, of the exercise of autonomy and of learning. Navigating the Internet, exchanging ideas with friends, listening to music, dancing and singing, doing sports and engaging in different modalities of games (either in a spontaneous or planned way) are all activities that demand personal commitment, different according to each individual but, most of the times, extremely intense and characterized by a search for personal realization/revelation (BARRÈRE, 2011). The mobilization of teenagers around these activities indicates, according to that author, that they extrapolate what is usually considered as an area of life dedicated to leisure, to the search for fun or to non-productive idleness.

In this case, significant differences will be identified if we consider the experience of boys and girls from different social strata. Alongside these practices, the obligations issuing from the domestic work occupy in a differential way these individuals, depicting possible and persistent inequalities in gender relations, notwithstanding the growing commitment of youngsters to school activities. Apart from that, although we have followed since the early 2000’s a progressive decline in the percentage of mothers within this age bracket (BRASIL, 2015a), – in 2004, 6.9% of adolescents were mothers; in 2014 they were 6.2% – the taking on of responsibilities within the family group may have consequences that cannot be neglected to the fruition of free time on the part of adolescents.

Signs of this asymmetry can be identified in the data from the PNDAs. They point, for example, to a slight reduction in the average weekly time invested by girls in domestic activities during this decade – from 18 hours a week in 2004 to 16 in 2014 – whereas among boys this number remained virtually stabilized at nine hours a week. This means that female teenagers continue to dedicate almost twice as many hours to domestic chores, when compared to their male peers, and that there was no increase in the commitment of boys to these activities as a counterpart to the reduction of the time dedicated by girls.

Youths between the ages of 18 and 24: heterogeneity of experiences

The age bracket between 18 and 24 is that in which the heterogeneity of situations experienced by individuals in the areas of studies, work and family life is most accentuated. This feature seems to be an indication that, at that moment in their lives, boys and girls experience displacements and transitions without them indicating the end of young age. Also, we could speculate here that this heterogeneity is a result of tensions and dilemmas experienced unequally by teenagers in different domains of social life, making this age group a particularly interesting object for the observation of the driving forces behind the divergence of youngsters’ life trajectories.

To a certain extent, agreeing with the perspective put forward by Adalberto Cardoso, we can say that the analysis of the experiences and challenges of individuals within this age group is capable of producing knowledge about how teenagers accomplish crucial transitions in their biographical trajectories and, at the same time, it allows us to identify the way in which social and historical characteristics of our country unfold as possibilities, potentialities or dilemmas for their individual trajectories (CARDOSO, 2013).

To start with, we have to say that the condition as a student loses its statistical significance to the understanding of the situations of girls and boys within the ages of 18 and 24. In 2004, only 32.2% of youths in this age group were at school; in 2014, they were 30%. However, this observation should not obscure the educational changes for this population, whose outlines can be apprehended from the situation of youths that remained within the educational system. In 2004, most of the students in this age group (66.3%) attended fundamental or secondary education; a decade later, higher education became the level predominantly attended by students within this age group (58.5%). In other words, there was no increase in the percentage of students, but the period registered an upshift in the level of education they attended with the increase in the access to higher education. This increase occurred both among boys and girls, but it was sharper among the girls (Chart 4).

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

Chart 4 – Student population between the ages of 18 and 24 according to level of education they attended, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

The change in the profile of students within this age group can be understood as a consequence of the massification of secondary education and of its effects upon the chances of girls and boys finishing basic education. It can also be seen to result from the various initiatives that fostered, since the early 2000’s, and intense expansion of enrolment in higher education.

In view of this process, we can observe a higher incorporation of the black population into higher education, as well as of youths coming from lower-income families (especially from those families situated within the intermediate quintiles). However, race and class inequalities were still expressive. In 2014, among white students 71.4% were enrolled in undergraduate courses, a reality for only 45.8% of mixed race students and 44.2% of black students. In that same year, among students coming from families of the first quintile (the 20% poorest), 28.3% were in higher education, whereas among those from the fifth quintile (20% richest) 81.8% attended higher education.

One is allowed to suppose that the access to this level of education will remain a challenge for the trajectories of a generation of youths that increasingly have expectations of continuing their studies after finishing basic education (SPOSITO; SOUZA, 2014). In this sense, understanding how they are positioned within a heterogeneous and segmented university field constitutes an important research agenda, capable of bringing to surface both the possibilities open to this population and the new facets of educational inequalities.

Having said that, we must not lose sight of the fact that a significant percentage of students within this age group remained in basic education in 2014, possibly in Education for Youths and Adults (EJA), and that among those who no longer remain within the educational system – the majority of youths within this age group –, a significant fraction (43.2% or, in absolute numbers, 6.5 million) had still not finished basic education. How do these youths live? What meanings did they attributed to the type of schooling they had access to? Faced with educational trajectories marked by failure and episodes of neglect, how do they signify the school in their lives? (DAYRELL et al., 2009).

At any rate, even if education is still a relevant theme to understand the experiences and trajectories of individuals within this age group, after they are 18 years old it is the world of labor that seems to constitute the central domain of social insertion and experimentation for a significant fraction of these individuals (Chart 5). In 2004, 60.4% of youths between the ages of 18 and 24 were at work, either combining this activity with their studies or otherwise. In 2014, despite a slight percentage reduction, the working situation continued to represent the situation of the majority (59.5%).

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

Chart 5 – Percentage of population between the ages of 18 and 24 according to activities, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

Data also confirm what Maria Carla Corrochano (2011) had already observed based on other studies: even if it is true that lower-income youths tend to enter the work market earlier in life, the age of 18 seems to be that in which the majority of this segment, even those in better situations, seek an occupation; from this moment on, social inequalities manifest themselves more sharply in the chances of individuals finding work and in the quality of labor they found. Among youths that worked in 2014, the poorer, the black and the women were subjected to works with lower wages and without legal ties. Independently of the period considered, it was among young black males and among females that the group of youths who did not work and did not study was more prominent.

Commonly referred to as neither nor, the youths that neither worked nor studied have acquired large visibility, particularly in the media, as a vulnerable and high social risk group. They are, undoubtedly, a clear index of the difficulties of work and educational insertion of youths. But we have to keep in mind the fact that this category includes individuals that experience rather heterogeneous situations. For example, youths that often dedicate themselves to domestic chores and to the education of their children or to the care of family elders are included in this group. Additionally, establishing one particular condition may be insufficient to apprehend a multiplicity of combinations that are flexible in time and that express the structural impossibility that individuals find to construct linear transitions or stable experiences in the areas of education and labor. Since it is not a longitudinal kind of study, the PNDAs do not offer data that allow us to foresee the duration and extension of this situation in the biography of an individual.

The studies centered on the work experiences of youths have shown how the meanings attributed by individuals in these age group to their work can be understood in the light of expectations that transcend the facing up to their economic hardship (TARTUCE, 2007). On this last aspect, we can suppose that, at that moment in their lives, the search for greater financial independence takes place within a context marked by changes in family relations that progressively compose a picture of living among adults. Youths continued to live under the same roof as their families of origin, but they experience a situation permeated by new responsibilities, obligations and commitments.

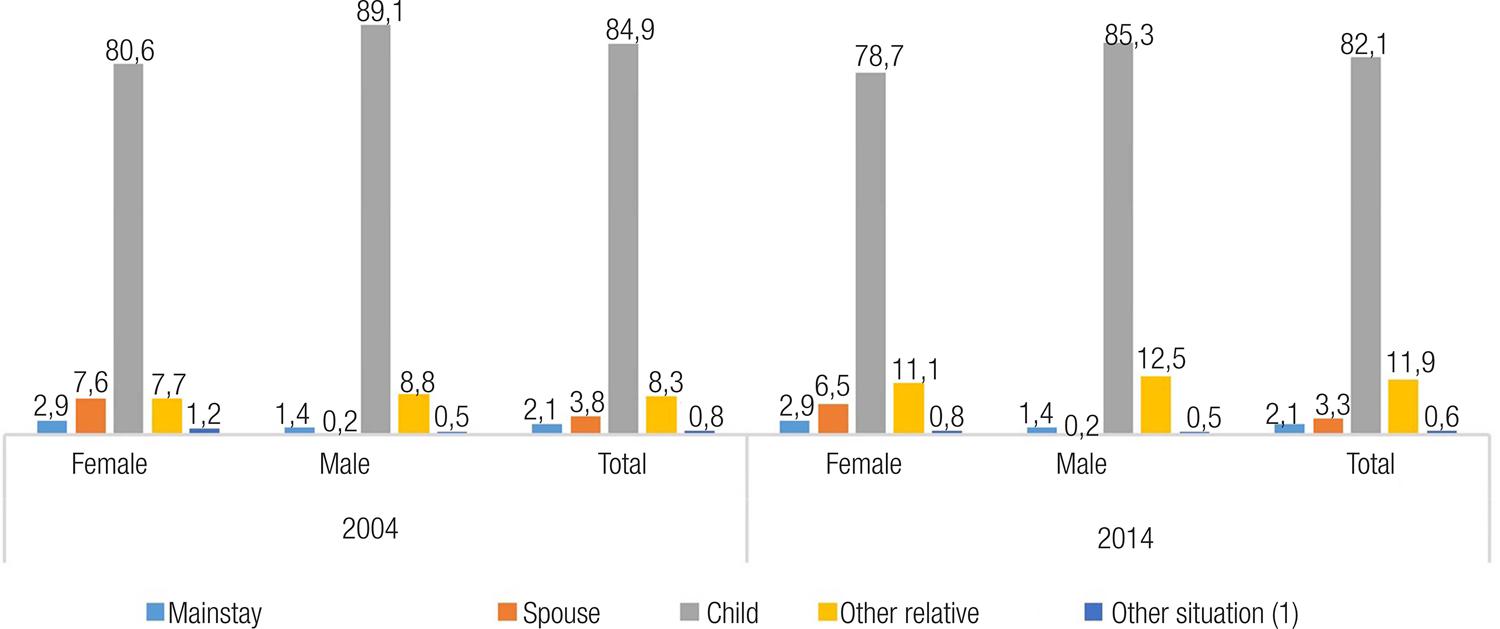

On the other hand, we should not neglect the fact that, within the family, the situation experienced by youths between the ages of 18 and 24 reveals a relative heterogeneity. Both in 2004 and in 2014 there was still a predominance of individuals that occupied the position of offspring but, within this age group, such position no longer enjoys the same hegemony verified in the 15 to 17 years-old cohort. In 2014, children represented 58.5% of youths within that age group, whereas 16% occupied position of mainstay and 14.7% were spouses within their families. Thus, at least for part of this population, the moment of youth was already marked by conjugal experiences and/or leaving their original home.

The change of position within the family is still permeated by gender nuances, despite a slight movement of convergence in the timelines of girls and boys during the period analyzed. Firstly, because in percentage terms young women, more than boys of this same age group, moved from the position of daughters to one of being responsible for the household or members of a couple. And, it was them that, when making this movement, generally occupied the position of spouses (Chart 6).

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

(1) Includes: non-relatives, pensioners, domestic workers and their relatives.

Chart 6 – Percentage of youths between the ages of 18 and 24 according to situation in the family, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

The most significant variations, however, are expressed when the family income variable is taken into account. In 2014, the lower the family income the larger the percentage of youths that found themselves in the position of mainstay or spouse. This information, however, must be taken cautiously, because it is not possible to establish from it a direct relationship between income, conjugality and leaving the parents’ home. Perhaps this number allows a hypothesis about the situation of sharper poverty of families led by youths, in other words, of groups in which individuals with ages between 18 and 24 take on positions as mainstay or as a spouse and that, being in this situation, are chiefly responsible for making up the domestic budget.

Parenthood, here apprehended exclusively through the information about the maternity of young girls, is equally indicative of experiences within the realm of family relations during this period of youth. In 2004, 36.8% of girls in this age bracket were mothers; in 2014, this number had fallen and now corresponded to the reality of only 31.1% of young women. Among young black women, the percentage of mothers is relatively higher than that of young white women, independently of the period analyzed; also, the decrease was less accentuated among them. This difference is still more pronounced when we consider the youths’ family income since, within this age group, it is among the poorest youths that the higher percentage of women that are mothers is to be found.

This group of data signals to the importance of a deeper understanding of the motives behind early maternity or its postponement, based not only on economic situations, degree of schooling or undesirable experiences, but also on an analysis of how pregnancy happens in adolescence, (BRASIL, 2015b). An intriguing silence surrounds the absence of information about paternity, since there are no questions directed at young men and, somehow, the presupposition is reasserted that, as poet Caetano says, the boys are “pains and delights” of women only. The survey Agenda Brasil (NOVAES, 2016) indicates that “the declaration of paternity among young men is around 20% of the universe of those between the ages of 18 and 24”.

These themes, among other gaps, have still failed to raise the interest of researches from a qualitative point of view within the field of gender studies. New studies may contribute to understand how, at that point in their lives, youngsters experience objectively and subjectively maternity and paternity. The theme seems to be important, particularly in a society that tends to require more and more, especially from young women, the possibility of articulating this experience with a productive insertion, the commitment to domestic chores and the continuity of studies, without offering them institutional support sufficiently capable of guaranteeing such conciliation. This experience also affects boys faced with the expectations of the traditional role of provider that still marks their trajectories5.

Apart from that, and although a reduction in the average weekly workload among workers in this age group can be observed, they still imply a significant time of their lives in labor-related activities. The majority (51.7%) dedicated between 40 and 44 hours a week to work, but a non-negligible percentage (22.8%) were engaged in activities that extrapolated this number. A minority were engaged in part-time occupations: 11.2% had works with up to 20 hours a week dedication and 14.3% up to 39 hours a week. It is clear that long working shifts are not exclusive to young female workers. Actually, the boys dedicated longer hours to work-related activities. But we can estimate that this feature declines distinctively along the life of individuals, according to their commitments to other domains.

Data seem to point out, still, a movement in which, as a trend, young women work hours ever more similar to those of young men, with the persistence of salary inequalities. We can suppose that intense working hours have consequences to the family and affective experiences during this stage in their lives and, at the same time, offer a range of constraints to those youngsters who still seek continuity or resumption of their studies.

The youths between the ages of 25 and 29: profile of Brazilian young adults

The completion of studies, beginning of a professional life, the constitution of independent household, with or without a spouse, and the experience of parenthood have been traditionally mobilized to signal the transit of individuals towards adult life. In this respect, since the late 1990s, and particularly based on the European experience, studies recognize the process-like character of these changes, as well as the tenuous limits between the beginning and the end of moments in a life’s trajectory that are entangled and often fail to be signaled by clear rites of passage (GALLAND, 1997; PAIS, 2001; VAN DE VELD, 2008). These are paths marked by comings and goings, well characterized as yo-yo trajectories by José Machado Pais (2001), which certainly poses important challenges to the study of Brazilian youths.

In Brazil, the transition to adult life is still little investigated within the studies about youth. The few existing studies, conducted within the fields of demography and economy, are based on national statistics and give emphasis to the passage from school to labor and show little capacity to probe the social changes and phenomena related to the transition processes (PIMENTA, 2007; CAMARANO et al., 2006).

In the Brazilian case, the demographic criteria, currently situated in the population between the ages of 15 and 29, are important premises for the characterization of the young population, but they are insufficient for the development of investigations, particularly about the segments situated in the age group above 25. The national policies extended the demographic limits, considering as youths those who are in this third group, since until recently the accepted markers included those up to 24 years of age. However, as the results of the Agenda Juventude Brasil survey suggest, for the majority of the members of this age group the perception that they are already adults is predominant (ABRAMO, 2016)6.

One strategy to develop qualitative studies about the specificities of this group resides in the analysis of the situation of youths within their family arrangements, a signal of the inter-crossing of some of the boundaries in the transit to adult age. In 2014, 63.2% of youths between the ages of 25 and 29 no longer occupied the position of offspring, with 34.6% having become the mainstay of their households and 28.7% being spouses in their own families.

With respect to the situation of men and women, the data indicate that there was a decrease in the last 10 years of 12.6 points in the number of women that occupied the position of spouses: 57.5% were in this condition in 2004 and in 2014 they were 45%. Young men made a different movement, from 3.6% of youths declaring the situation of spouses in 2004, they were 11.1% in 2014 (Chart 7). In an interval of 10 years the number of young women that became the mainstay within their family groups increased (from 18.3% to 25.3%) and the proportion of young men in the situation decreased (from 55.8% to 44.2%).

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

(1) Includes: non-relatives, pensioners, domestic workers and their relatives.

Chart 7 – Percentage of youths between the ages of 25 and 29 according to situation in the family, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

Apart from the fact that these changes are related to a greater insertion of women into the work market, they also result, as some studies indicate, from new social configurations that have started to surround the unions established by individuals, in which the financial participation of women in the domestic budget becomes absolutely necessary, and hierarchies grounded in asymmetric gender relations give way to the emergence of conjugal unions marked by greater horizontality (LIMA, 2006). We can here conjecture that they follow equally from innovations and transformations in the family arrangements in this generation of youths, for example, the shaping of single-parent families, of homosexual unions, and of mothers in “solo flight”.

A fruitful set of questions requires new answers: how are gestated the decisions to leave the parents’ home and live alone or with a partner? What are the challenges present in the experience of building a new domestic or family unit? What forms of support are expected and mobilized by individuals with the aim of accomplishing this transit from home/family of origin to their own home/family? The individuals can be subjected to similar constraints, but how do they react to them when they cannot rely on the same resources to leave the parents’ home and/or build a new family unit?

Our attention is also drawn to the variations in the percentage of youths that remained in the condition of children when some other variables are considered. In 2004, 35% of men remained in the situation, a percentage that increased to 36.6% in 2014. Women in a similar situation were 20.1% in 2004 and moved up to 25% in 2014. There was an increase in this percentage in all economic levels, but it was the youths from the fifth quintile of family income (20% richest) that were more often found in this situation in 2014 (53.5%). Similarly, inequalities are found on the race/color aspect: in 2014, 31.4% of white youths were in the situation of children, whereas this percentage was of 28.4% among mixed race youths and 25.6% among black youths.

The data above point to the need to conduct qualitative studies that help understanding the motives that lead this group of youths to remain with their parents in the situation of children. Is it a procrastination of the beginning of conjugal life or is it a reversal of trajectory? The data do not allow us to verify if it is the youths that depend on their families, or if their families rely on their monthly contribution to the household’s income, or even if they are dependent on the emotional and affective support (CAMARANO et al., 2006; PIMENTA, 2007).

In the age group between 25 and 29 we find the largest number of young mothers, but this situation registered a fall during the decade: in 2004, 67.5% of young women were mothers; in 2014, this percentage was of 59.3%. As observed in the previous age group, the studies about fertility in Brazil have associated the procrastination of maternity to the expansion of the time dedicated by women to schooling, to commitments they assume in the world of labor, as well as the changes in the gender and affective-sexual relations. Although the fall in the percentage of mothers has occurred for the whole of them, young women belonging to lower-income families remained comparatively more representative within the group of mothers: in 2014, 52.1% of young mothers between the ages of 25 and 29 belonged to families of the first (29.5%) and second (22.6%) quintiles of income.

It is worth noting that this set of information is insufficient to draw a more comprehensive picture of these individuals and their life conditions within their families. Both maternity/paternity and conjugality do not mean necessarily exiting the household of origin, and perhaps here we find an important Brazilian peculiarity, especially in the lifestyles of popular segments.

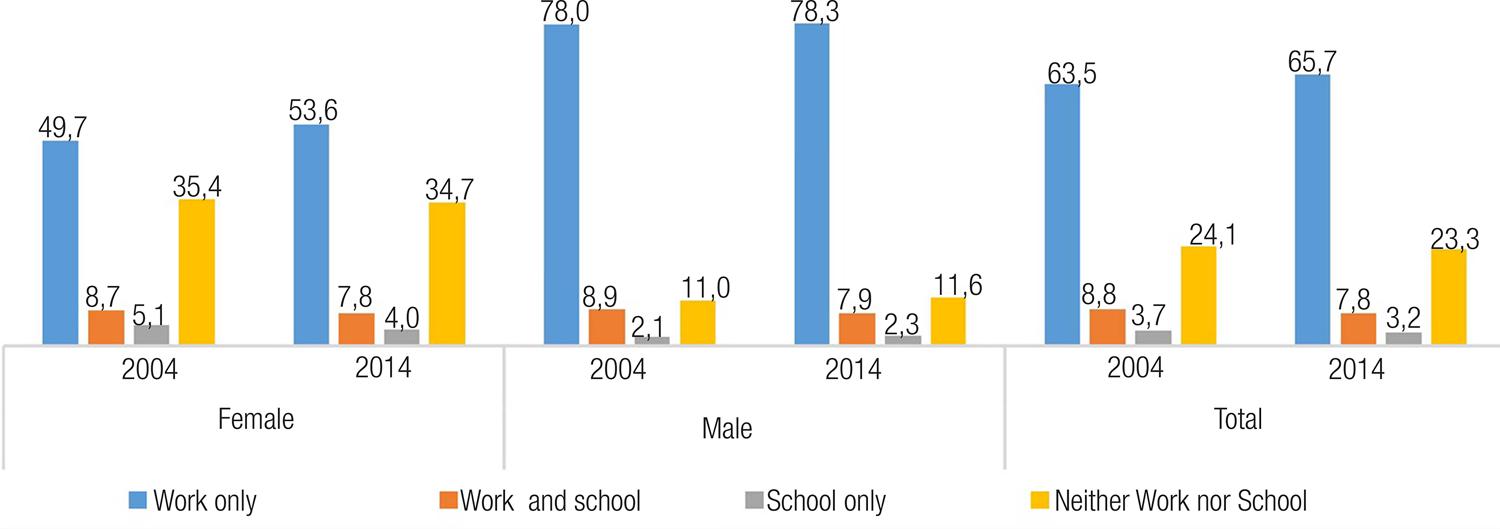

As already pointed out, work represents an experience present in the lives of young Brazilian men and women, often in a premature fashion. However, among youths with ages between 25 and 29, this dimension of life takes on rather incisive features: in 2004, 72.2% of individuals in these age group worked, among which only 8.8% balanced work activities and studies; in 2014, these percentages were of 73.5% and 7.8%, respectively (Chart 8). It is also noticeable within this age group the high percentage of youths that neither studied nor worked, and of indicators that show this to be a more common situation among women. In 2014, 33.1% of young women did not study and did not have any activities in the labor market, whereas among young men 11.6% were in this situation, which means a difference of 23.1 points.

Source: National Survey of Household Sampling (PNDA) / IBGE.

Chart 8 – Percentage of youths between the ages of 25 and 29 according to type of activity, by sex (Brasil, 2004 and 2014).

During the decade, there was an increase in the percentage of workers in regular employment, from 48.3% to 60.1%. More formal work relations spread to the whole of the population in this age group, but certain segments of youths remained more affected by irregular work in 2014. Among white male youths, for example, 15.5% were in irregular employment, a percentage that among black male youths was of 21.8%, and of 22.9% among mixed race male youths. Similarly, youths coming from lower-income families were more often found in irregular work.

Independently of the period in question, the majority of youths between the ages of 25 and 29 no longer studied, either in 2004 (85%) or in 2014 (89%). These percentages vary slightly according to the sex of the individuals, and tend to acquire some differentiation when markers such as family income and race/color are considered. Among youngsters from the first quintile of income (20% poorest), 94.3% did not study, whereas among those of the fifth quintile (20% richest) this number was 82.2% – a difference of 12.1 points. In a similar way, among white youths in 2014 87.1% did not study, the reality of 90% of blacks and 90.7% of mixed race youths.

It would be a mistake to consider, however, that the more expressive features of educational inequalities among individuals in this age group are related to their permanence within the educational system, because the most significant variations are to be found in the level of schooling they achieve, particularly in the chances of having finished basic education and carried on studying. Firstly, we must say that in 2014, among youths that no longer studied, there was a predominance of those who had finished secondary education, a fraction of 45.2%. This group was closely followed by youths who had left school before finishing basic education, the case of 37.8% of them. Youths who completed higher education, including those with master or doctorate studies (complete or incomplete) represented only 17% of individuals in this cohort.

Following the same pattern, income and race/color inequalities are also present. Among youths on the first quintile of income (20% poorest), 64.2% had not finished basic education, which occurred only to 11.3% of youths belonging to the fifth quintile of income (20% richest). In 2014, among white youths that were no longer students, 28.2% had left school before finishing basic education, a number that represented the reality of 42% of young blacks and 45.7% of mixed race youths. Young women showed more favorable schooling indexes, with higher rates of completion of basic education and, particularly, of higher education.

These differences carry implications to the present situation of young women and men. The fact that they interrupted (either definitely or temporarily) their studies does not mean the end of the challenges mobilized around schooling, notably in a society historically known as the Land of the Bachelors where individuals are increasingly pressured by demands of schooling in the world of labor.

Having said that, and although educational improvements do translate in an increase of income for workers (OECD, 2016), one should be cautious when dealing with the relations between schooling, work insertion and socioeconomic improvement, since studies reveal income inequalities between sexes and the stratification of careers and courses in higher education (BRASIL, 2016; RIBEIRO; SCHLEGEL, 2015).

Finally, although the percentages of young students in this age group was relatively small in 2014, it is important to consider that the majority of them (80%) attended higher education, a reality relatively distinct from that found 10 years earlier in 2004, when a higher percentage of students in this age group were still in basic education (Chart 9). In other words, we observe that older individuals, including those with low income, began to have access to this level of schooling, possibly attending evening courses and in private institutions.

Final considerations

It has been emphasized both in the debate about different stages of life and about the processes of transition into adult life that one of the main features of contemporaneity is a process of dechronologization and deinstitutionalization of society, in which individuals’ ages no longer constitute markers signaling differences and positions occupied by individuals in the social structure. But, as Guita Grin Debert (1999) puts it, it would be a mistake to suppose that peoples’ ages no longer represent a fundamental dimension in the social organization. She says: “the incorporation of changes could hardly be done without a new chronologization of life” (DEBERT, 1999, p. 75). The exercise conducted in this article seems to corroborate the argument of that anthropologist, without neglecting the heterogeneity and inequality that surrounds the experience of individuals situated in the different juvenile cohorts.

Each moment in the life’s trajectory reveals a set of constraints, challenges and possibilities in the domains presented here that cannot be known without an investigation of a qualitative nature about the young individuals and their paths. The recognition of certain centrality in these dimensions does not preclude the pertinence of a plurality of domains and experiences that can be converted into fruitful and important themes of research. Within the present picture, in October 2016, clear signs of economic crisis are present, indicating that the reduction in the number of working posts has affected particularly the youths (PERRIN, 2016). The difficulties to continue in their studies can also acquire more significant proportions in recessive scenarios, considering, for example, in the case of higher education, the strong predominance of private institutions, and the government’s turnabout regarding programs of expansion of public places and of inclusion in this level of schooling. The reduction in the number of new enrolments in higher education, notably in the private school system, which was already visible in the 2015 School Census (INEP, 2016), seems to be a sharp indicator of a new moment.

Without disregarding conjunctural aspects that define the dimension of the political-economic crisis, we have to enlarge the universe of concerns of the research so as to include the analyses considering the set of dimensions that affect the lifestyle of youths, and that intercross at the challenges with which this segment of the population is faced. The search for independence and autonomy, and the increasing load of responsibilities unfold in various ways according to the stage in life’s trajectory. For each of the stages analyzed here, the challenges are proposed and faced in different ways, in which the structural positions indicate the constraints, but do not explain, by themselves, all trajectories.

This exercise does not carry as a presupposition the idea that qualitative approximations are mere operators to illustrate the evidence constituted by quantitative data. It is all about facing the challenge proposed more than 50 years ago by Wright Mills (1965), and seeking to understand the relations between biography and history. It is all about investigating, based on individuals – in this particular case, the youths – the structural constraints that unfold differently in each moment of life’s trajectory, and faced with which individuals are no longer just characters that respond to previously established positions (MARTUCCELLI, 2010).

Danilo Martuccelli, when proposing the study of individuation as a fruitful approximation within his historical sociology, points out for suggestive directions for new investigations:

One, we have to preserve a link between the individual and the structural dimensions of society – lest we reduce sociology to an endless gallery of individual portraits. Two, it is indispensable that in the study of the singularity the socio-historically situated and incarnate character of every individual is underlined. Three, it is important to account for the existence of certain stability proper to individuals. Four, it is fundamental to account, based on a renewed conception of agency, for the work of one on oneself carried out by each individual. (MARTUCCELLI, 2013, s/p).

REFERENCES

ABRAMO, Helena Wendel. Identidades juvenis: estudo, trabalho e conjugalidade em trajetórias reversíveis. In: NOVAES, Regina et al. Agenda Juventude Brasil: leituras sobre uma década de mudanças. Rio de Janeiro: Unirio, 2016. p. 19-60. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Wilson Mesquita de. Prouni e o ensino superior privado lucrativo em São Paulo: uma análise sociológica. São Paulo: Musa, 2014. [ Links ]

ARAUJO, Kathya; MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. La inconsistencia posicional: un nuevo concepto sobre la estratificación social. Revista CEPAL, Santiago de Chile, n. 103, p. 165-178, abr. 2011. Disponível em: <http://repositorio.cepal.org. Acesso em: 16 set. 2016. [ Links ]

BARRÈRE, Anne. L’education buissonniere: quand les adolescents se forment par eux-mêmes. Paris: Armand Colin, 2011. [ Links ]

BRANDÃO, Zaia. Os jogos de escalas na sociologia da educação. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 29, n. 103, p. 607-620, ago. 2008. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v29n103/15.pdf. Acesso em: 10 set. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Coordenação de população e indicadores sociais. IBGE. Síntese de indicadores sociais: uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira 2015. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2015a. Disponível em: <http://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br. Acesso em: 16 set. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Panorama da educação: destaques do Education at a Glance 2016. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.inep.gov.br/. Acesso em: 16 set. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Ministério da Saúde. Saúde Brasil 2014: uma análise da situação de saúde e causas externas. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde, 2015b. 464 p. Disponível em: <http://bvsms.saude.gov.br. Acesso em: 16 set. 2016. [ Links ]

CABANAS, Pedro; KOMATSU, Bruno; MENEZES FILHO, Naercio. O crescimento da renda dos adultos e as escolhas dos jovens entre estudo e trabalho. São Paulo: Insper: Centro de Políticas Públicas, 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.insper.edu.br. Acesso em: 21 jun. 2016. [ Links ]

CABANES, Robert. Espaço privado e espaço público: o jogo de suas relações. In: TELLES, Vera da Silva; CABANES, Robert (Org.). Nas tramas da cidade: trajetórias urbanas e seus territórios. São Paulo: Humanitas, 2006. p. 389-432. [ Links ]

CAMARANO, Ana Amélia et al. O processo de constituição de família entre os jovens: novos e velhos arranjos. In: CAMARANO, Ana Amélia (Org.). Transição para a vida adulta ou vida adulta em transição? Rio de Janeiro: IPEA, 2006. p. 199-224. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, Adalberto. Juventude, trabalho e desenvolvimento: elementos para uma agenda de investigação. Caderno CRH, Salvador, v. 26, n. 68, p. 293-314, ago. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ccrh/v26n68/a06v26n68.pdf. Acesso em: 5 abr. 2016. [ Links ]

CORROCHANO, Maria Carla. Trabalho e educação no tempo da juventude: entre dados e ações públicas no Brasil. In: PAPA, Fernanda de Carvalho; FREITAS, Maria Virginia de (Org.). Juventude em pauta: políticas públicas no Brasil. São Paulo: Peirópolis, 2011. p. 45-72. [ Links ]

DAYRELL, Juarez. A escola faz as juventudes? Reflexões em torno da socialização juvenil. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, p. 1105-1128, 2007. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v28n100/a2228100. Acesso em: 5 abr. 2016. [ Links ]

DAYRELL, Juarez et al. Juventude e escola. In: SPOSITO, Marilia Pontes (Coord.). O estado da arte sobre juventude na pós-graduação brasileira: educação, ciências sociais e serviço social (1999-2006). v. 1. Belo Horizonte: Argvmentvm, 2009. p. 57-126. [ Links ]

DAYRELL, Juarez; JESUS, Rodrigo Ednilson de. Relatório de pesquisa: a exclusão de jovens de 15 a 17 anos no ensino médio no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Observatório da Juventude, 2013. [ Links ]

DEBERT, Guita Grin. Velhice e o curso da vida pós-moderno. Revista USP, São Paulo, n. 42, p. 70-83, ago. 1999. Disponível em: <http://www.revistas.usp.br/revusp/article/view/28456. Acesso em: 16 set. 2016. [ Links ]

ENGUITA, Mariano Fernández. Del desapego al desenganche y de este al fracaso escolar. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 41, n. 144, p. 732-751, set. 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/cp/v41n144/v41n144a05.pdf. Acesso em: 12 maio 2014. [ Links ]

FANFANI, Emilio. Culturas jovens e cultura escolar. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2000. Documento apresentado no seminário “Escola Jovem: um novo olhar sobre o ensino médio”. [ Links ]

FLEURY, Sonia. Do welfare state ao warfare state. Conjuntura Política Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Dossiê n. 2, jun. 2013. [ Links ]

GALLAND, Olivier. L’entrée des jeunes dans la vie adulte. Problèmes Politiques et Sociaux, Paris, n. 794, dez. 1997. [ Links ]

HASENBALG, Carlos. A transição da escola ao mercado de trabalho. In: HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle (Org.). Origens e destinos: desigualdades sociais ao longo da vida. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2003. p. 147-172. [ Links ]

INEP. INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Sinopse estatística da educação superior 2015. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2016. Disponível em: <http://portal.inep.gov.br. Acesso em: 07 out. 2016. [ Links ]

LIMA, Márcia. A participação das mulheres na família e no mercado de trabalho: conquistas e desafios futuros. diverCIDADE: Revista Eletrônica do Centro de Estudos da Metrópole, São Paulo, n. 10-11, jul./dez. 2006. Disponível em: <http://www.fflch.usp.br/centrodametropole/antigo/v1/divercidade/numero10/7.html. Acesso em: 01 set. 2016. [ Links ]

MADEIRA, Felícia Reicher. Os jovens e as mudanças estruturais na década de 70: questionando pressupostos e sugerindo pistas. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 58, p. 15-48, ago. 1986. [ Links ]

MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. La société singulariste. Paris: Armand Colin, 2010. [ Links ]

MARTUCCELLI, Danilo A individuação, estratégia central no estudo do individuo. In: CHARRY, Carlos Andrés; PEDEMONTE, Nicolás (Ed.). La era de los indivíduos: actores, política y teoria en la sociedad actual. Santiago de Chile: LOM, 2013. s/p. [ Links ]

MENEZES FILHO, Naercio. Renda dos pais e trabalho dos jovens. 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.valor.com.br/colunistas/NaércioMenezesFilho >. Acesso em: 16 fev. 2015. [ Links ]

MILLS, Wright. A imaginação sociológica. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1965. [ Links ]

NOVAES, Regina et al. Agenda Juventude Brasil: leituras sobre uma década de mudanças. Rio de Janeiro: Unirio, 2016. [ Links ]

OECD. Education at a Glance 2016: OCDE indicators. Paris: OECD, 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2016_eag-2016-en. Acesso em: 1 set. 2016. [ Links ]

PAIS, José Machado. Ganchos, tachos e biscates: jovens, trabalho e futuro. Lisboa: Ambar, 2001. [ Links ]

PERRIN, Fernanda. Trabalhador jovem foi o mais afetado pelos cortes de vagas em 2015. Folha de S. Paulo, São Paulo, 17 set. 2016. Disponível em: <http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2016/09/1814193-trabalhador-jovem-foi-o-mais-afetado-pelos-cortes-de-vagas-em-2015.shtml. Acesso em: 25 set. 2016. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, Melissa de Mattos. Ser jovem e ser adulto: identidades, representações e trajetórias. 2007. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Carlos Costa; CENEVIVA, Ricardo; BRITO, Murillo Marschner Alves de. Estratificação educacional entre jovens no Brasil: 1960 a 2010. In: ARRETCHE, Marta (Org.). Trajetórias das desigualdades: como o Brasil mudou nos últimos cinquenta anos. São Paulo: Edunesp, 2015. p. 79-108. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Carlos Antônio Costa, SCHLEGEL, Rogério. Estratificação horizontal da educação superior no Brasil (1960 a 2010). In: ARRETCHE, Marta (Org.). Trajetórias das desigualdades: como o Brasil mudou nos últimos cinquenta anos. São Paulo: Edunesp, 2015. p. 133-162. [ Links ]

SIROTA, Régine. Élements pour une sociologie de l´enfance. Paris: PUF: 2006. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marilia Pontes. Algumas reflexões e muitas indagações sobre as relações entre juventude e escola no Brasil. In: ABRAMO, Helena Wendel; BRANCO, Pedro Paulo Martoni (Org.). Retratos da juventude brasileira: análises de uma pesquisa nacional. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo, 2005. p. 87-127. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marilia Pontes (Coord.). Juventude e escolarização (1980/1998). Brasília, DF: MEC/INEP/Comped, 2002. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marilia Pontes (Coord.). O estado da arte sobre juventude na pós-graduação brasileira: educação, ciências sociais e serviço social (1999-2006). V. 1. Belo Horizonte: Argvmentvm, 2009. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marilia Pontes; SOUZA, Raquel. Desafios da reflexão sociológica para análise do ensino médio no Brasil. In: KRAWCZYK, Nora (Org.). Sociologia do ensino médio: crítica ao economicismo na política educacional. São Paulo: Cortez, 2014. p. 33-62. [ Links ]

STAKE, Robert. Estudos de caso em pesquisa e avaliação educacional. Rio de Janeiro: PUC, 1982. Comunicação apresentada no seminário sobre Avaliação em Debate promovido pelo departamento de Educação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (PUC/RJ), ago. 1982. [ Links ]

TARTUCE, Gisela Lobo Baptista Pereira. Tensões e intenções na transição escola-trabalho. 2007. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 10 desafios do ensino médio no Brasil para garantir o direito de aprender de adolescentes de 15 a 17 anos. Brasília, DF: Unicef, 2014. [ Links ]

VAN DE VELDE, Cécile. Devenir adulte: sociologie comparée de la jeunesse en Europe. Paris: PUF, 2008. [ Links ]

3- We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Rafael Serrao and Rogério Limonti in the design and production of the tables and charts in this article.

4- This position must be understood as an expression of the heterogeneity of family arrangements that could exist in the country and, at the same time, of the role played by the family networks in their strategies to care for their younger members.

5- Also within this age group, between 2004 and 2014, there was a reduction of the average time spent by young women in domestic chores, but a stagnation of this indicator among young men: in 2014 young women dedicated an average of 20 hours a week to these activities; young man dedicated 9.4 hours a week.

Received: October 07, 2016; Accepted: April 04, 2017

texto em

texto em