Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.44 São Paulo 2018 Epub 24-Nov-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201844175560

Articles

Effects of socialization on scout youth participation behaviors

2Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal. Contatos: mrodrigues@fpce.up.pt; imenezes@fpce.up.pt; pferreira@fpce.up.pt

This paper assumes the premise that youth political socialization in contemporary society is based on dynamic processes, which emerge from the simultaneous actions and interactions of different social agents and contexts, constituting opportunities of civic learning and democratic living that influence the youth experiences of civic and political participation. This study explores the longitudinal effects of the interaction between family, peers, media, and the scout association in political activism, civic participation and online civic participation of young people. Through a longitudinal study design, the same cohort of 473 Portuguese scout youth, aged between 14 and 22, were observed in three separate moments during six months, between January 2014 and March 2015. A series of analyses of latent growth models allowed the analysis of the effects of the combination of agents of political socialization, both at inicial levels and at the trajectories of changes in forms of participation. The results demonstrate not only the interdependence between the various agents of socialization with which young people relate in everyday life, but also the influences that these exert vary according to the type of participation. Political activism is significantly influenced by peers and the scout association. The development of civic participation is enabled by the scout association and by the media (television and radio). Online participation is essentially exerted by the media (Internet, television and radio) and by the interpersonal discussions about political issues.

Key words: Political socialization; Civic and political participation; Longitudinal study; Youth

Este artigo parte da premissa de que a socialização política juvenil na contemporaneidade se baseia em processos dinâmicos que emergem da ação e interação simultâneas de diferentes contextos e agentes sociais, constituindo oportunidades de aprendizagem cívica e vivência democrática que influenciam as experiências juvenis de participação cívica e política. Assim, este estudo explora os efeitos longitudinais da interação entre a família, pares, mídia e associação escoteira no ativismo político, participação cívica e participação cívica online de jovens. Recorrendo a um estudo longitudinal de painel, o mesmo coorte de 473 jovens escoteiros(as) portugueses(as), com idades entre os 14 e os 22 anos, foram observados em três momentos separados por seis meses, entre janeiro de 2014 e março de 2015. Uma série de análises de modelos de crescimento latente permitiram analisar os efeitos da combinação dos agentes de socialização política quer nos níveis iniciais quer nas trajetórias de mudança das formas de participação. Os resultados obtidos demonstram não só a interdependência entre os vários agentes de socialização com que os(as) jovens se relacionam no cotidiano, mas também as influências que estes exercem variam consoante o tipo de participação. O ativismo político é influenciado significativamente pelos pares e pela associação escoteira. O desenvolvimento da participação cívica é potenciado pela associação escoteira e pela mídia (televisão e rádio). A participaçãoonlineé essencialmente fomentada pela mídia (internet, televisão e rádio) e pelas discussões interpessoais sobre assuntos políticos.

Palavras-Chave: política; Participação cívica e política; Estudo longitudinal; Jovens

INTRODUCTION

Education, independently of context where it happens, has always had a function of socialization, that manifests in the diverse experiences through which we become active members and participants of specific social, economic, cultural, and political orders ( BIESTA, 2009 ). During the transition of youth to adulthood, particularly from the age of 14 ( AMADEO et al., 2002 ), young people develop their political identities and behavior patterns that sustain the political culture through processes that are usually classified as political socialization (e.g., EASTON; DENNIS, 1969 ; GUTMANN, 2003 ). After some time of absence in the scientific production, those processes acquired a new standing, in part, triggered by the transformations in the democratic political culture, which have occured in the last decades, at the level of civic and political participation of younger citizens (AMNÅ et al., 2009). First of all, both participation behaviors should be distinguished. In summary, while political participation concerns the actions that aim to influence directly or indirectly the political processes and institutions on various levels, the civic participation relates to the actions that seek to contribute to problem solving and community well-being ( VERBA et al., 1995 ).

The studies that simultaneously combine the effects of different agents of political socialization in participation behaviors show that the influence of each context can change over time, depending on the interaction with other contexts in which young people find themselves (WILKENFELD; LAUCKHARDT; TORNEY-PURTA, 2010; AMNÅ et al., 2009). For example, the interpersonal conversations and discussions on political subjects in different contexts (family, peers, Internet and organizations) may exert mutual influences in the processes of political socialization ( McLEOD, 2000 ).

Against this background, this paper intends to fill three major gaps in the research: conceptualizing and measuring the construct of participation, attending the diversity of forms and contexts ( MENEZES et al., 2012 ); analysing the processes of political socialization in a longitudinal perspective; and simultaneously integrating different agents into the explanatory models of the political socialization processes (AMNÅ et al., 2009). Thus, this paper explores the effects of the interaction of various socialization agents (family, peers, media and scout association) in the development over time of political activism (e.g. participating in a protest), civic participation (e.g. volunteering) and online civic participation (e.g. discussing political issues on Facebook) of young people.

Research methodological design

Procedure and sample

This research adopted a longitudinal panel design, where the same cohort of participants was observed in three separate moments during six months, between January 2014 and March 2015. Included in the sample were only the young people who responded to inquiries through questionnaire in the three times, this was composed by 473 young scouts, aged between 14 and 22, members of the 122 scout groups of the Corpo Nacional de Escutas (Portuguese Catholic Scout Association), the most representative Portuguese voluntary association to operate in non-formal education. Knowing that the scout association presents an uneven distribution of groups and scouts throughout the national regions, a stratified probabilistic sample was used. Each region was considered as a stratum and, within each one, a random sample of scout groups was selected, taking into account their relative weight from the register of the 2012 CNE Census. Scout groups that did not have scouts within the age group were excluded from the study. After collecting the written and informed consent of each participant (or respective parents or legal representative in the case of being a minor), each one filled out the inquiry by questionnaire individually in paper format or online. Being a collective administration, standardized instructions for clarification were written for filling out the questionnaire, emphasizing both the anonymity and confidentiality of the answers and the voluntary nature of the participation in the study. Each questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Measures

Control variables . The questionnaire included the collection of sociodemographic data of participants, namely gender (0 = female; 62.6%), age group (0 = 14 - 17 years, 58.99%) and sociocultural status on time 1 (a composite variable that results from the aggregation of the average of four variables: the current school year of the participant, the level of education of the mother and father of the participant, and the number of books at home).

Civic and political participation . The youth participation behaviors were analysed through an adaptation of the civic and political action scale of Lyons (2008) . An exploratory factorial analysis was performed to examine the dimensionality of the 10-item scale, using the IBM SPSS Statistic 22.0 program. Given the results, three items - participate in political actions that might be considered illegal (e.g., painting walls, burning a flag, throwing stones, etc.); vote in elections; buy (or not buy) products for political, ethical, or environmental reasons - were excluded for not presenting correlations above 0.30 with the remaining items. The resulting 7-item scale shows a structure of three components, using the typology developed by Ekman and Amnå (2012): political activism (PA, sign a petition; attend a public meeting or demonstration dealing with political or social issues); civic participation [CP; volunteering; wear symbols or emblems to show support for a social or political cause (e.g., badges, t-shirts with a message, etc.); donate and collect money to a social or political cause or organization]; and online civic participation [hereinafter referred to as online participation (OP); write or send contents about politics or societal issues (e.g., emails, blogs, Facebook, Youtube, etc.); discuss social or political issues with other people on the Internet]. The participants reported the frequency with which they performed each one of those actions in the previous six months, using a Likert scale of five points, being 1 = never and 5 = very frequently. Looking at the Cronbach’s alpha, all these variables revealed acceptable reliability values along the three moments: time 1, AP α = 0.53, PC α = 0.62, PO α = 0.63; time 2, AP α = 0.72, PC α = 0.68, PO α = 0.79; and in time 3, AP α = 0.68, PC α = 0.69, PO α = 0.83.

Three indicators were selected from the literature to measure the effect of each agent of political socialization under analysis in this longitudinal study.

Scout association: i) duration of involvement in the association (open question; ranging from 0 to 17 years); ii) intensity of involvement in the association (single item; ranging from 1 = not very actively involved to 5 = very actively involved); and iii) quality of participation experiences (ranging from 1 = very low quality to 5 = very high quality). The Quality of Participation Experiences scale ( FERREIRA; MENEZES, 2001 ) was transformed into a composite variable that results from the calculation of the average of the eight items that represent the dimensions of action and reflection that characterize the participation experiences. The participants were asked about the frequency with which they performed a set of action activities (look for information in books, in the media or by asking to other people with more experience; participate in activities, such as collecting donations or food, environmental campaigns, petitions, protests, debates, etc.; organize activities, such as collecting donations or food, environmental campaigns, petitions, protests, debates, etc.; and take part in group decision-making or alone) and of reflection (different points of view were discussed; conflicting opinions gave rise to new ways of seeing the issues; real and/or everyday life problems were focus of discussion; and the participation was important to he/she). Focused on their experiences within the scope of the scout activities, the respondents indicated with what frequency they performed each one of those activities in the previous six months, using a 5-point scale, being 1 = never and 5 = very frequently. This variable had good internal consistency over time:: time 1 QEP α = 0.86; time 2 QEP α = 0.75; and time 3 QEP α = 0.83.

Each one of the indicators, presented as follows, is constituted by a single item that was assessed by the participants using a 5-point scale, being 1 = I completely disagree and 5 = I completely agree.

Family: i) discussion of social problems and political issues with parents or close relatives; ii) volunteering of parents or close relatives; and iii) social, civic and political involvement of the parents or close relatives (for example, they are members of the City Council, local associations, political parties, etc.) ( PORTER, 2013 ).

Peers: i) discussion of social problems and political issues with friends; ii) volunteering of friends; and iii) participation of friends in social, civic or political activities (for example, they are members of an association for the defense of human or animal rights or youth parties, etc.) ( PORTER, 2013 ).

Media: i) reading political news in newspapers and magazines; ii) watching television or radio programs about political issues; and iii) following political information that circulates on the Internet ( MENEZES et al., 2012 ).

In terms of interpretation of results, higher scores on the items represent higher levels in the respective constructs under analysis.

Procedure and data statistical analysis

With the purpose of exploring the effect of the four political socialization agents in the three forms of participation, either in the inicial levels (time 1) and over time, a series of analyses of latent growth models were conducted using the IBM SPSS Amos 23.0 program. This type of model is an application of structural equation models that allow us to consider both intraindividual changes in behavior over time and interindividual differences in these changes. That statistical technique also makes it possible to analyze the influence of external predictors that may explain that variability, both at the initial levels (intercept) and at the rate of change or growth (slope) ( MARÔCO, 2010 ). The method of maximum likelihood was adopted to deal with missing data, because it is considered a pertinent approach in the modelling of latent growth ( MARÔCO, 2010 ).

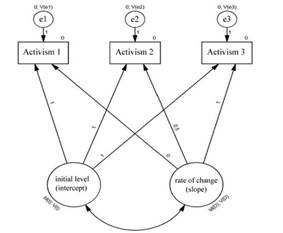

The data analysis was developed in two phases. In a first phase, to examine the variation both in group (fixed effects) and in individual level (random effects) in political activism, civic participation and online participation in the three times of observation, three unconditional latent growth models were used, as represented in Figure 1 . In terms of model identification ( MARÔCO, 2010 ), at the initial moment (time 1), it was assumed that the slope is null and that there was a tendency of linear growth in the following moments, therefore, the weights of the trajectories between the slope and the manifested variables were fixed at 0, 0.50 and 1, respectively. The latent intercept variable was included in the models to examine the average value of the three forms of participation in the three moments of observation. As such, all the trajectories that leave the intercept towards the manifested variables present the same weight, being set at 1.

Source: Authors’ elaboration

Figure 1 Scheme of the unconditional latent growth model of political activism

The intercept and slope means allowed the estimation of the initial means of the three forms of participation and their respective average rate of change over time. The intercept and slope variances were examined to assess the existence of individual differences both in the baseline values and the rate of change of the participation behaviours. In a second phase, three conditional models were estimated, in which were included the control variables and the indicators of each socialization agent observed in the three moments, as predictor variables of the intercept and the slope. The effects of the agents of political socialization observed in the second and third observation moments were not regressed in the initial values (time 1) of the forms of participation, since they could not have exerted any kind of influence.

The Chi-square test (Chi 2 /df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess model fit (MAÔCO, 2010).

RESULTS

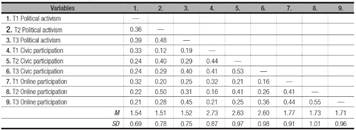

Preliminary analyses were accomplished, which showed that the manifested variables held, in the three moments of observation, absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis lower than 1.89 and 3.76, respectively, demonstrating the assumption of the multivariate normality ( FINNEY; DISTEFANO, 2006 ). Table 1 shows means (M), standard deviations (SD), and correlations between activism, civic participation and online participation in the three moments (T1, T2 and T3).

Table 1: Means. standard deviations. and correlations between. civic participation and online participation in the moments* (N = 473)

Source: Survey data.

* All coefficients are significant at the ρ ≤ 0.01.

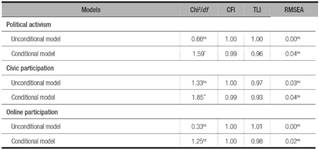

Unconditional latent growth models

The unconditional latent growth model presented in Figure 1 was estimated for the three participation forms, revealing good model fit ( Table 2 ). When analyzing the results ( Table 3 ). the unstandardized estimates of the three models indicated that both the mean value (fixed effect) and the variance (random effect) of the intercept are statistically significant. The participants displayed a mean of 1.54 (standard error [SE] = 0.03) of political activism. 2.73 (SE = 0.04) of civic participation. and 1.76 (SE = 0.04) of online participation at the baseline level. We can also affirm that there is interindividual heterogeneity in the initial levels of the three participation forms.

Table 2: Goodness of fit statistics for each of the univariate and multivariate models

Source: Survey data.

* ρ ≤ 0,05; ** ρ ≤ 0,01; *** ρ ≤ 0,001; ns = non significant ( ρ > 0,05).

Table 3: Unstandardized parameter estimates for the fixed and random intercept and slope for the non-conditional models of political activism and civic participation.

Source: survey data.

* ρ ≤ 0,05; ** ρ ≤ 0,01; *** ρ ≤ 0,001; ns = non significant ( ρ > 0,05).

The results also showed that the slope means of political activism and online participation are not statistically significant, revealing that there were no significant changes in these behaviors over time. Only civic participation presents a slope mean statistically significant, indicating that there occurred a small decrease in the mean of this participation form throughout the study. Simultaneously, it is important to highlight that the results provided evidence of the existence of intraindividual variability that did not manifest itself in the slope means of civic participation and online participation of the participants. Therefore, the participants are not homogeneous about their participation behaviors, manifesting different patterns of change in civic participation and online participation. As for political activism, the slope variance was not statistically significant, demonstrating that the participants did not differ in their individual trajectories of change. In the face of this scenario, it was pertinent to introduce into the models other predictor variables, namely the indicators of the agents of political socialization under study, capable of explaining the heterogeneity of the participants either in their starting values or in the different changes that occurred. All of the manifested variables presented positive correlations between the intercept and the slope, although statistically not significant (Est AP = 0,10 , z = 0,32, ρ = 0,75; Est PC = -0,18, z = -0,96, ρ = 0,34; Est PO = 0,00, z = 0,004, ρ = 0,10), revealing that young people with higher initial levels of civic and political participation tend to exhibit smaller changes over time compared to the young people who exhibited lower starting values.

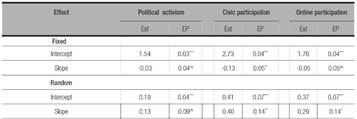

Conditional latent growth models

After unconditioned latent growth models were tested, the control variables and the indicators of the agents of political socialization in the three moments of observation were introduced into the models as predictors of the starting values and trajectories of change of participation behaviours, according to the description made in the previous section. To make the models more parsimonious, only the indicators that showed a statistically significant effect on the slope of the forms of participation were maintained in the models ( Table 4 ). The results revealed a good quality of adjustment to the proposed models ( Table 2 , conditional models).

Table 4 Latent growth models of the participation forms conditioned by the effect of the political socialization agents in the three moments

Source: Survey data. Note: the values correspond to the standardized estimates and their respective significance;

† These parameters were not estimated because the activism did not show significant variability around the slope;

n.i. = trajectories not included in the model because they were not significant;

“-” = these parameters were not estimated;

*p ≤ 0,05; ** p ≤ 0,01; *** p ≤ 0,001; ns = non significant (p > 0,05).

As Table 4 shows, gender revealed to be a statistically significant predictor of initial values of civic participation, indicating that, at the departing point, scores of female participants are significantly inferior to those of male participants. The age group also emerged as being a significant predictor of the intercepts of activism and online participation, especifically the older young people (18-22 years) reported higher starting levels than younger ones (14-17 years). About the slopes, significant differences only occurred in the case of online participation relative to the age group, in comparison with the older participants, younger participants exhibited a decrease of little significance in that form of participation over time. The sociocultural status of the participants did not reveal a direct effect neither at the starting values nor in the changes that occurred in participation behaviors. This contradicts results from other studies that verified that the scores of the various forms of participation increase significantly with the increase of the sociocultural status of the participants ( MENEZES et al., 2012 ).

Rather than direct, the relationship between youth sociocultural status participation may be better understood as being mediated by personal variables (e.g. self-esteem, locus of control and political efficacy) (COHEN; VIGODA; SAMORLY, 2001).

When analyzing the effects of the socialization agents observed in the first moment on the intercepts, the results revealed that the peers and the scout association are the agents of socialization that predict higher starting levels of activism, specifically the existence of active civic and political peers and experiences of high quality participation in the scout association. As for civic participation, once again the scout association and the peers emerged as the main predictors of higher starting values. Although a positive effect is confirmed by the fact that peers performed volunteering, this is considerably more modest than the effect of the quality of participation experiences in the scout association. Finally, all the agents of socialization exerted influence on the starting values of online participation. As would be expected, reading political information that circulates on the Internet is the most significant predictor; however the active civic and political involvement of the family and peers in their communities also exhibited a positive effect on this form of participation. Overall, these indicators explained between 29% to 48% of the total variance in the initial levels of the participation forms, which can be considered reasonably satisfactory values.

Analysing the effects of the socialization agents in the development of participation behaviours, in the case of civic participation, the quality of participation experiences in the scout association emerged as the most impacting predictor over time. Although a negative effect was verified over the quality of the participation experiences in the scout association on the slope at the first moment, indicating that participants who reported higher values in this variable are less likely to increase their levels of civic participation, in the second and third moments of observation this indicator showed a positive effect on the slope. Therefore, with the increase in the quality of participation experiences in the scout association, the participants also tend to exhibit higher levels of civic participation ( Table 4 ). The media and peers had also shown to have an impact on civic participation over time. Although following programs on television and/or radio and discussions of a political nature with peers do not affect the behaviors of civic participation of the participants in the first moment, those indicators demonstrated a significant effect on the second moment. On the one hand, young people who consumed political contents through television and/or radio tended to reinforce that behavior, on the other hand, discussing more with their peers about political issues led to decreases in the way they were engaged civically.

Regarding online participation, we can confirm that media and family are the agents of socialization that predicted greater differences in the changes in that behavior over time. In the case of the media, although these indicators initially had presented a negative effect or had no effect on the online participation of the participants, the growing consumption of political content over the Internet, television and radio over time has led to increases in that form of participation. Given the influence of the family, in the initial moment having a family member civically or politically active in the community revealed a positive effect on online participation; however, the increase of the frequency of political discussions within the family potentiated an increase in this behavior over time. Finally, although high quality participation experiences in the scout association were associated with higher levels of online participation, these had a negative effect on the slope at the initial moment. When we introduce the effects of the agents of political socialization in the three moments, as predictors of the slopes, these parameters explain 30% and 21%, respectively, of the variability in the trajectories of change of civic participation and online participation.

FINAL REMARKS

Nowadays, young people can involve themselves and participate in a wide range of real and digital contexts, in which they develop different relationships and experience diverse situations, that allow them to “learn the value of democratic and non-democratic forms of action and interaction and it is also through these experiences that they learn about their own positions as citizens” ( BIESTA, 2008 , p. 174). Therefore, this article started on the assumption that the political socialization of contemporary young people is based on dynamic processes that emerge from the simultaneous action and interaction of different agents and socializing contexts, constituting opportunities for civic learning and a democratic living that influence the experiences of young people of civic and political participation.

The combination of the effects of different agents of political socialization, both at the initial levels and in the development of forms of participation, revealed interesting results, reinforcing not only the interdependence of the various contexts and agents of socialization, but also the partial independence of the diverse forms of participation for evidencing different sources of influence. In the case of family, for example, the fact that parents or other family members volunteer has a positive, although modest, effect on how the young person not only volunteers, but also how he/she participates in demonstrations and petitions. Or, the existence of a family member who plays an active role in a particular political party affects how young people publish and discuss political content on the Internet. However, the promotion of discussions about social problems and political issues within the family has a favourable impact, in the long term, on increasing the online participation of young people. Recognizing that parental influence tends to decrease during the transition from youth to adulthood, not only because young people spend less time with their parents but also for wanting more autonomy, friends and peers gain a greater role in the process of political socialization (eg, Šerek, UMEMURA, 2015; SMETANA, 2011 ). Thus, having friends or family who are members of a political party or an association for the defence of animal rights significantly influences how young people participate in a protest or how they share and discuss political issues on Facebook. However, while the fact that peers volunteer positively affects civic participation, the political discussions with them tends to negatively influence this behavior over time. This seems to contradict the results of previous studies that emphasize the importance of peers in the political socialization of young people, particularly by showing that the political discussions between peers constitute an important and influential predictor of the increment of juvenile political participation ( QUINTELIER, 2015 ; ŠEREK; UMEMURA, 2015 ). This result can be interpreted as a cynical effect of the participation triggered by the political discussions between peers, negatively affecting young people’s behaviours of civic participation. This means that, during conversations with their friends, young people may not only share their participation experiences, but can also critically make these actions problematic, resulting in a withdrawal or disbelief in what concerns their impact in a transforming and emancipatory social change. In other words, although young people are concerned with public well-being, engaging with the needs and problems of their communities through their services and volunteer work, during moments in which they socialize with their peers, they may conclude that these forms of participation (i.e. volunteering, raising donations or using symbols to demonstrate support for certain social and political causes) do not have the desired effect on social reality and, thus, fail to invest in those actions because they have a palliative character of the symptoms of social problems, more than resolving structural inequality and social injustice that are at their origin ( BIESTA, 2008 ; PRIESTLEY; 2013 ). Either way, that relationship may be explored in future research. As for the impact of the media, despite the initial negative effect, young people who spend more of their time consuming political content on the Internet, television and radio tend to increase their levels of civic and online participation. Contrary to results from previous studies (e.g., SHAKER, 2014 ), reading newspapers and/or magazines did not have a significant effect on juvenile behaviours of participation. Perhaps the effect of reading newspapers and/or magazines on the proposed models had been mediated by the effect of Internet browsing. The Internet allows rapid access and sharing of a set of endless information, including political content of newspapers and online magazines ( SERRA, 2006 ). Therefore, contemporary young people, immersed in this technological and communicational reality, reveal a preference for reading by means of the computer screen, in detriment to reading printed format ( COUGHLAN, 2013 ). In relation to the scout association, the experiences of high quality participation in this associative context were shown to be influential in explaining higher initial levels of activism, but, above all, they proved to be the most significant predictor in the trajectories of change in civic participation over time. Therefore, in consonance with previous longitudinal studies (e.g. AZEVEDO, 2009 ), the fact that that associative context enables participation experiences in which young people effectively enjoy opportunities either of involvement in significant issues in their communities, simultaneously expressing their opinions in interaction with a plurality of others (peers and adults) and perspectives, or of a critical analysis and reflection of these experiences, has significantly affected levels of participation of young people, namely through volunteering and other actions of a civic character. In sum, the search for information gathered from different sources, the positive perception of civic and political participation of peers and the family, the participation in political discussions and the quality of participation experiences in associative contexts, constitute powerful predictors of the different trajectories of change of the juvenile behaviours of participation in the public sphere.

Like any empirical study, the present study should be analysed in the light of some limitations. Although longitudinal data was used, the causality of the relationship between the agents of political socialization and juvenile behaviors of civic and political participation was not determined, given the purpose of this article. Thus, future research should scrutinize the directionality of these relationships. Future studies that analyse the relationship between the processes of political socialization and the trajectories of participation of young people should integrate into the models either the effects of other agents of socialization, such as the neighborhood, the school or different types of associations, or other forms of participation that are utilized by contemporary young people.

Referencias

AMADEO, Jo-Ann et al. Civic knowledge and engagement: an IEA study for upper secondary students in sixteen countries. Amsterdã: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement - IEA, 2002. [ Links ]

AMNÅ , Eriket al. Political socialization and human agency: the development of civic engagement from adolescence to young adulthood. Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, Lund, v. 111, n. 1, p. 27-40, 2009. [ Links ]

AMNÅ, Erik; ZETTERBERG, Pär. A political science perspective on socialization research: young nordic citizens in a comparative light. In: SHERROD, Lonnie; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith; FLANAGAN, Constance (Org.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. Hoboken: New Jersey: John Wiley, 2010. p. 43-65. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, Cristina N. Experiências de participação dos jovens: um estudo longitudinal sobre a influência da qualidade da participação no desenvolvimento psicológico. Porto: Universidade do Porto, 2009. Manuscrito não publicado. [ Links ]

BIESTA, Gert J. J. A school for citizens: civic learning and democratic action in the learning democracy. In: LINGARD, Bob; NIXON, Jon; RANSON, Stewart (Org.), Transforming learning in schools and communities: the remaking of education for a cosmopolitan society. London: Continuum, 2008. p. 170-183. [ Links ]

BIESTA, Gert J. J. Boa educação na era da mensuração. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 42, n. 147, p. 808-825, 2009. [ Links ]

BIESTA, Gert J. J. Learning democracy in school and society: education, lifelong learning and the politics of citizenship. Roterdã: Sense, 2011. [ Links ]

BRITES, Maria José. Jovens e culturas cívicas: por entre formas de consumo noticioso e de participação. Covilhã: Livros LabCom, 2015. [ Links ]

COHEN, Aaron; VIGODA, Eran; SAMORLY, Aliza. Analysis of the mediating effect of personal-psychological variables on the relationship between socioeconomic status and political participation: A structural equations framework. Political Psychology, Lund, v. 22, n. 4, p. 727-757, 2001. [ Links ]

COUGHLAN, Sean. Young people ‘prefer to read on screen’. BBC News Education and Family, United Kingdom, 16 maio 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.bbc.com/news/education-22540408 . Acesso em: 9 nov. 2016. [ Links ]

CRAMER, Duncan; HOWITT, Dennis. The SAGE dictionary of statistics: a practical resource for students in the social sciences. London: Sage, 2004. [ Links ]

DENAULT, Anne-Sophie; POULIN, François. Intensity and breadth of participation in organized activities during the adolescent years: multiple associations with youth outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, New York, v. 38, n. 9, p. 1199-1213, 2009. [ Links ]

EASTON, David; DENNIS, Jack. Children in the political system: origins of political legitimacy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969. [ Links ]

EKMAN, Joakim; AMNÅ, Erik. Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Human Affairs, Slovakia, v. 22, n. 3, p. 283-300, 2012. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Pedro D.; AZEVEDO, Cristina; MENEZES, Isabel. The developmental quality of participation experiences: beyond the rhetoric that “participation is always good!” Journal of Adolescence, Oxon, v. 35, n. 3, p. 599-610, 2012. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Pedro D.; MENEZES, Isabel. Questionário das experiências de participação. Porto: Universidade do Porto , 2001. Manuscrito não publicado. [ Links ]

FINNEY, Sara J.; DISTEFANO, Christine. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: HANCOCK, Gregory R.; MUELLER, Ralph O. (Org.). Structural equation modeling: a second course. Greenwich: Connecticut: Information Age, 2006. p. 269-314. [ Links ]

FLANAGAN, Constance. Volunteerism, leadership, political socialization, and civic engagement. In: LERNER, Richard; STEINBERG, Laurence (Org.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley, 2004. p. 721-746. [ Links ]

FLANAGAN, Constance; SHERROD, Lonnie. Youth political development: an introduction. Journal of Social Issues, Washington, v. 54, n. 3, p. 447-456, 1998. [ Links ]

GARDNER, Margo; ROTH, Jodie; BROOKS-GUNN, Jeanne. Adolescents’ participation in organized activities and developmental success 2 and 8 years after high school: do sponsorship, duration, and intensity matter? Developmental Psychology, Washington, v. 44, n. 3, 814-830, 2008. [ Links ]

GUTMANN, Amy. Identity in Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003. [ Links ]

HARRIS, Anita; WYN, Johanna; YOUNES, Salem. Beyond apathetic or activist youth: ‘ordinary’ young people and contemporary forms of participation. Young, Nordic Journal of Youth Research, Berlim, v. 18, n. 1, p. 9-32, 2010. [ Links ]

LYONS, Evanthia. Political trust and political participation amongst young people from ethnic minorities in the NIS and EU: a social psychological investigation. Belfast: University Belfast, 2008. Relatório Final. [ Links ]

MARÔCO, JOÃO. Análise de equações estruturais: fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações. Pêro Pinheiro: Report Number, 2010. [ Links ]

McINTOSH, Hugh; HART, Daniel; YOUNISS, James. The influence of family political discussion on youth civic development: which parent qualities matter? PS: Political Science and Politics, Washington, v. 40, n. 3, p. 495-499, 2007. [ Links ]

McLEOD, Jack M. Media and civic socialization of youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, San Francisco, v. 27, n. 2, p. 45-51, 2000. [ Links ]

McLEOD, Jack et al. Communication and education: creating competence for socialization into public life. In: SHERROD, Lonnie; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith; FLANAGAN, Constance (Org.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. Hoboken: John Wiley, 2010. p. 363-391. [ Links ]

MENEZES, Isabel et al. Agência e participação cívica e política: jovens e imigrantes na construção da democracia. Porto: Livpsic/Legis, 2012. [ Links ]

NORRIS, Pippa. Democratic phoenix. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [ Links ]

PORTER, Tenelle J. Moral and political identity and civic involvement in adolescents. Journal of Moral Education, Birmingham, v. 42, n. 2, p. 239-255, 2013. [ Links ]

PRIESTLEY, Mark. What kind of citizen, what kind of citizenship? Professor Mark Priestley’s blog, Stirling, 21 nov. 2013. Disponível em: http://mrpriestley.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/what-kind-of-citizen-what-kind-of-citizenship. Acesso em: 11 abr. 2014. [ Links ]

PROCTOR, Tammy. Introduction: building and empire of youth: scout and guide history in perspective. In: BLOCK, Nelson; PROCTOR, Tammy (Org.), Scouting frontiers: youth and the scout movement’s first century. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. p. xxvi-xxxviii. [ Links ]

PUTNAM, Robert. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American democracy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000. [ Links ]

QUINTELIER, Ellen. Engaging adolescents in politics: the longitudinal effect of political socialization agents. Youth and Society, Michigan, v. 47, n. 1, p. 51-69, 2015. [ Links ]

QUINTELIER, Ellen. Who is politically activist?: Young people, voluntary engagement and political participation who is politically active: the athlete, the scout member or the environmental. Acta Sociologica, Turku, v. 51, n. 4, p. 355-370, 2008. [ Links ]

ROKER, Debi; PLAYER, Katie; COLEMAN, John. Source Young People’s Voluntary and Campaigning Activities as Sources of Political Education. Oxford Review of Education, London, v. 25, n. 1/2, p. 185-198, 1999. [ Links ]

RUBIN, Kenneth et al. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: DAMON, William; LERNER, Richard (Org.). Developmental psychology: an advanced course. New York: Wiley , 2008. p. 1-82. [ Links ]

ŠEREK, Jan; UMEMURA, Tomo. Changes in late adolescents’ voting intentions during the election campaign: disentangling the effects of political communication with parents, peers and media. European Journal of Communication, Amsterdã, v. 30, n. 3, p. 285-300, 2015. [ Links ]

SERRA, Paulo. Internet e interactividade. Biblioteca Online de Ciências da Comunicação da Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, 2006. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.bocc.ubi.pt/pag/serra-paulo-internet-interactividade.pdf . Acesso em: 9 nov. 2016. [ Links ]

SHAKER, Lee. Dead newspapers and citizens’ civic engagement. Political Communication, Philadelphia, v. 31, n. 1, p. 131-148, 2014. [ Links ]

SHERROD, Lonnie; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith; FLANAGAN, Constance. Promoting research on youth civic engagement. In: SHERROD, Lonnie; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith; FLANAGAN, Constance (Org.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth . Hoboken: John Wiley , 2010. Preface. p. xi-xiv. [ Links ]

SMETANA, Judith G. Adolescents, families, and social development: how teens construct their worlds. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [ Links ]

VERBA, Sidney; SCHLOZMAN, Kay; BRADY, Henry. Voice and equality: civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

WILKENFELD, Britt; LAUCKHARDT, James; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith. The relation between developmental theory and measures of civic engagement in research on adolescents. In: SHERROD, Lonnie; TORNEY-PURTA, Judith; FLANAGAN, Constance (Org.). Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth . Hoboken: John Wiley , 2010. p. 193-219. [ Links ]

ZHOU, Yushu. The role of communication in political participation: exploring the social normative and cognitive processes related to political behaviors. Washington, DC: Washington University, 2009. Manuscrito não publicado. [ Links ]

Received: February 09, 2017; Revised: August 08, 2017; Accepted: September 12, 2017

texto en

texto en