Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 14-Oct-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945217129

THEMATIC SECTION: SPECIAL EDUCATION

Repercussion of the national policy in Special education in the state of Espírito Santo in the past ten years *

1-Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. Contacts: mlalmeida.ufes@gmail.com; dochris.ferrari@gmail.com; leidemary8@gmail.com.

This text aims at reflecting on the Brazilian National Policy in Special Education in the inclusive perspective, its implications on the public policies and actions aimed at special education students, in the context of the Espírito Santo state (ES), Brazil. It focuses on the dimensions of politics, offer and management from 2008 to 2018. It is a case study which has as its initial goal of historicizing special education in the state, through the investigation of laws, resolutions, decrees and other documents, cross-linked with reports from public administrators in special education, in the search for grasping the implications of the national policy towards this population in the state of Espírito Santo. Finally, this study questions the enrolment process in the education system by analyzing the records of the School census concerning special education. The analysis suggests that the national policies for special education in Brazil and in the state of Espírito Santo, are the result of disputes, negotiations and connections with political forces from different social groups in the state context. In this respect, there are nuances and contradictions, for, at the same time that they ensure the inclusion of special education pupils in regular school, they also offer technical and financial support to non-profit private institutions performing in the special education area.

Key words: Public Policies; Inclusion in Schools; Espírito Santo

Este texto objetiva refletir acerca da Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva Inclusiva, suas implicações nas políticas públicas e ações voltadas aos alunos da educação especial, a partir do contexto do Espírito Santo (ES). Focaliza as dimensões da política, da oferta e da gestão no período de 2008 a 2018. Trata-se de um estudo de caso com o propósito inicial de historicizar a educação especial no estado, por meio da consulta a leis, resoluções, decretos e outros documentos, entrecruzados com os relatos dos gestores públicos de educação especial, na busca por captar as implicações da política nacional nas ações voltadas a essa população no ES. Por último, o estudo problematiza a trajetória da matrícula nas redes de ensino por meio de análise de matrículas do censo escolar relativas à educação especial. A análise aponta que as políticas de educação especial, no Brasil e no ES, são resultado de disputas, negociações e correlações de forças políticas de diferentes grupos sociais no âmbito do estado. Nesse sentido, revelam nuances e contradições, pois, ao mesmo tempo que asseguram a inclusão dos alunos da educação especial no ensino regular, também estabelecem apoio técnico e financeiro às instituições privadas sem fins lucrativos com atuação em educação especial.

Palavras-Chave: Políticas públicas; Inclusão escolar; Espírito Santo

Introduction

School inclusion, as part of a battle for social rights, has produced intense debates, reflection and public policy in attempting to guarantee access, continuity and learning to all students at schools. The understanding of the expression school inclusion is rooted in the contributions of Garcia (2004 , p. 2), who defines them as

[...] a complex and contradictory practice, with a sense of battle, of confrontation, which necessarily lives together with its opposite — exclusion — however, it is established in the direction of questioning and overcoming the social practices based on inequality.

It is assumed that these words may undertake different ideological designs in discourses from different spheres. Thus, they might be used for the statement and universalization of rights, as well as for neglecting the differences existing in the teaching institution, creating exclusion processes from/in the school, as long as, under the neoliberal2logic, inclusion presupposes an adaptation to the existing school model.

In the past decade, there was an enactment of the National Policy in Special Education under the Inclusive Education perspective (PNEE-EI) (BRAZIL, 2008), which began to guide the Brazilian educational systems in the process of implementing actions regarding the work with special education students in the school context. This policy implementation process took place within a contradictory historical-political scenario of inclusion/exclusion, in which there was the attempt the meet the needs of the individuals who were at school, and also meet the demands presented under the logic of neoliberal policies of education to all. It is within this dialectic process that the social policies are formed and their practices are developed. In this context, it becomes necessary to reflect on public policy, as well as on the role of the State as society.

We use, then, Gramsci’s concept of State. Gramsci promotes an expansion in the Marxist theory concerning the concept of State, which corresponds to the union of political society and civil society. As Gramsci himself summarizes in the (Prision) Notebooks, “State = political society + civil society, that is, hegemony armed by coercion” (GRAMSCI, 2004, p. 244). The State is found in the superstructure in dialectic relation to the structure. When performing this change, as Mendonça states (2007), Gramsci performs a redefinition and rebuilds a concept of State, which moves forward through incorporation. According to Gramsci, the State is an educator in the sense that it holds social control through domination as well as through guiding society, by consensus. The goal is adjusting the grass-roots to the development of the economy’s productive apparatus, having the public policies, such as education, as an example for this mechanism.

Gramsci conceived civil society as part of the State. In civil society, the balance of powers is formed in dispute. The hegemonic action takes place essentially inside civil society, which is defined as private apparatuses of hegemony. Such relations are the ones responsible for the creation, organization and dissemination of ideologies. Hegemony consists of the political pair of the civil society concept, for it is the civil society’s articulation factor. In the Gramscian realm, hegemony finds the material basis of its social function as mediation between economical structure and the legal-political relations, which are no longer a mere reflex of the structure. Civil society is not only the context where consensus is created, it is also the place where conflicts and competitions for conquering hegemony are. It is a place of fight of hegemonies for hegemony. Thus, special education policies are created in this field of balance of power of different social groups. This way, the fights permeate the structure of the State and interfere in the creation of policies, in turn, “[...] resulting from the class contradictions integrated in the very structure of the State” ( POULANTZAS, 2000 , p. 134).

This text aims at reflecting on the PNEE-EI ( BRASIL, 2008 ), its implications in the public policies and actions toward special education target audience (PAEE), in the context of Espírito Santo (ES), in the past decade. In order to do so, we focus on the dimensions of politics, offering and management in the period from 2008 to 2018.

For this purpose, a case study has been carried out. Chizzotti (2008) highlights that this type of research has as its goal the search for extensive knowledge from a particular context, from data collection and registers from different sources, in order to apprehend a single experience, analyzing it carefully and connecting it to historical, political and social relations. Therefore, we intend to investigate the process of implementation of the special education policy in the state of Espírito Santo2, connected to PNEE-EI ( BRASIL, 2008 ).

Initially, we attempted to historicize and analyze the special education policies in Brazil and in the state of Espírito Santo addressed to the education of the Target Audience For Special Education (PAEE), through documental investigation in laws, resolutions, decrees and other documents. In order to capture the procedures implemented from legal guidelines in the municipalities of Espírito Santo, a semi-structured interview was carried out. It was sent through the Internet (Google Form) for public administrators in Special Education of the 78 municipal education networks in Espírito Santo, containing twelve questions which comprehended the organization of the special education field in the municipality, its structure, PAEE students’ schooling, the type of Specialized Educational Service (SES AEE), the connection with specialized agencies and the funding for this type of education. We got 58 questionnaires back, which represents a sample of 74, 35% of the public administrators’ answers. It is worth considering that in all regions3 of the state we got answers back, reaching an average of 50% of the municipalities.

In a second moment, aiming at analyzing the path of the enrolment at special education in Brazil and in Espírito Santo, we searched the database of the Anisio Teixeira National Institute of Study and research in Education (INEP). The school census data, concerning special education were analyzed afterwards, taking into consideration the quantity of enrolment in special education in the context of primary education and its articulation with policies implemented in the period from 2008 to 2018.

The paper is organized in two sections, besides the introduction, in which we have pointed out the theoretical and methodological background. Initially, we analyzed the legal documents and the answers provided by the public administrators in special education from three periods of time. Finally, we conducted an analysis about the relationship between special education policies, in the federal and State contexts, and the offer of this type of education in Brazil and in Espírito Santo. We conclude this paper with considerations that summarize our thoughts.

In this Item, we discuss the special education policy in ES, in a dialogue with the background of PNEE-EI ( BRASIL, 2008 ), from 2008 to 2018. The Special education policy in Espírito Santo has had three different moments throughout this decade. In the first moment, from 2008 to 2013, the state attempted to implement actions, following, in general, the national guidelines. In the second moment, there was the promulgation of Decree number 92-R, on May 21st, 2014 ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014c ), which stipulated, through a registration public notice, changes in the way of funding the Specialized Educational Service (AEE). The third moment lasted from 2017 to 2018, it was characterized by a technical cooperation term between the state government and municipalities, transferring Specialized Educational Service from public schools to private special education, including resources from second enrolment in the schools and of the Fund for the Development and Maintenance of Elementary Education and Recognition of the Teaching Profession (Fundeb).

Espírito Santo in conjunction with the national policy of special education (2008-2013)

In 2008, the Ministry of Education and Culture released the National Policy in Special Education under the Inclusive Education perspective (PNEE-EI), with the objective of “[...] creating public policies which promote quality education to all students” ( BRASIL, 2008 ). Within this context, the target audience for special education (PAEE) has also been defined: student with disabilities, PDD and high abilities/giftedness. This way, PNEE-EI has been established as public policy for the creation of an inclusive school, emphasizing the role of the educational management and system in this process. As performance space of special education, this very document has suggested teacher training with general knowledge to perform in common classes of mainstream education, in resourceful classrooms, in specialized special education service centers, in accessibility centers in higher education, among other areas ( BRASIL, 2008 ).

Those guidelines appear in the public administrators’ answers, when questioned about how PNEE-EI has been implemented in their municipalities, regarding actions connected to enrolment assurance, teacher training and the process of school inclusion. One of them states that:

Special education policy — Inclusive Education — Has been gradually implemented at the municipality since 2008, promoting training for educators, hiring teachers with specific training, offering tutors/ trainees at schools, hiring bilingual teachers and Brazilian Sign Language interpreters, making sure students will have access to school and that they will remain in it throughout primary school and assuring support to after-school shift students at the resource classrooms (Public Administrator A).

We have highlighted, in this report, that special education policy has been understood as a State intervention, making sure that PAEE’s rights, based on the principles oriented by the national policy, in the attempt to assure access, continuity and learning to students.

In this regard, PNEE-EI is a policy that is still being implemented in the municipalities, as public administrators state: “[…] we are organizing ourselves so that in 2019 we might have AEE in all schools that have students with disabilities” (Public administrator C); “[…] in our municipality we have been trying to align the [Brazilian National Common Curricular Base] BNCC” (public administrator D).

Resolution no 4, October 2nd 2009 ( Brasil, 2011 ) and Decree No. 7.611, from November 17th, 2011 ( BRASIL, 2011 ), point out that AEE has the function of complementing or supplementing students’ education, by providing services, accessibility resources and strategies that tear down the barriers to their full participation in society and to their learning progress. Therefore, PAEE, in order to attend the AEE, has to be enrolled in a regular class. AEE must be performed, primarily, in the resource room of the regular school, or, in the Specialized Educational Service Center (CAEE) of the public school system or the community, religious or philanthropic institutions. AEE must be attended in the opposite shift students go to school, they are not a substitute for regular classes.

In 2010, the Government of the state of Espírito Santo approved the Resolution of Educational State Council (CEE) no. 2,152, from January 7th 2010, which provides on special education in the state educational system, besides the guidelines of this type of education in primary and professional education for the state educational system through decree no 974-S4. Article 2 of this resolution assures enrollment in regular classes in regular education as well as in CAEE in the public educational system or community, religious or nonprofit philanthropic institutions. It also assures that these classes must be attended in the opposite shift students go to their regular schools, and that these classes are not a “substitute to regular classes” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010a ).

Article 3 sees special education as transversal to all levels, stages and types of education, which must interact with the Pedagogical Proposal of the school. In order to do so, and in order to institutionalize AEE offer, the school or the CAEE has to provide resource room, students enrolment at the AEE, trained teachers, other educational professionals, and support network in the context of professional education through partnerships and agreements ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010a ).

Chapter III of the resolution is completely dedicated to the regulation of the centers which offer AEE. The CAEE must require from the State Council of Education (CEE) the institutional accreditation, a regulatory note which does not characterize authorization for the formation of levels and/or types of primary education or higher education. For this accreditation, some legal documents are required, such as certificate of good standing, no debts to the institution “[…] offering equal conditions for having access and continuity” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010a ) to all students, forbidding any type of charges; proving nonprofit goals and meeting minimal quality standards required from regulatory body of the educational system, including its pedagogical proposals.

As for students supported by special education, we take into consideration the same target audience of the national policy. Regarding AEE, we highlight that its activities must be different from the ones performed in the regular class and that it must occur in the opposite shift the regular classes do, thus, it is not a substitute for regular education. The goal of special education is “to provide students with conditions for access, participation and learning in regular education” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010b ).

Based on the pieces of information provided by public administrators, AEE performed at school stands out as municipal suplementary/complementary support to the education networks in Espírito Santo. Thirteen out of 58 municipalities perform AEE only in the multi-functional resource rooms of the municipal network itself. Lots of the municipal networks (34) offer mixed AEE (institution and school), as public administrators in special education describe: “Only three schools offer AEE in the extracurricular shift; however we intend to regulate this situation in 2019. APAE also offers AEE and receives financial support from the City Government of R.B” (public administrator F). “In extracurricular shift serving one student per hour. Individual service or in groups of up to four students. We have a partnership with the APAE from B.J.I. where our students are supported in schooling/ CAEE/ Medical Clinic and screening with a multidisciplinary team (public administrator G)

It is important to emphasize that eight municipalities offer AEE only though partnerships with specialized institutions: “We have a partnership with APAE. Our municipality performs this type of support in the Educational Units with specialized professionals who receive support and training from the pedagogical body of SEME – Special Education Management (public administrator H).

It is worth pointing out that three municipalities have not answered the questions concerning AEE offer. In this context, it is the municipality that searches in an integrated way the collaboration among areas of the community to enlarge AEE, characterizing the cooperation among sectors in the actions:

PAEE students attend on a daily basis regular classes in regular education and in the extracurricular shift, twice a week AEE in SRM inside the very school, motivating inclusion from daycare up to the end of elementary school, always in articulation with families and other areas such as Health and Social Action (Public Administrator I).

The pieces of information concerning the policies implemented in the education networks in Espírito Santo, in this first moment, are articulated according to the national guidelines. Thus, they suggest that “special education will be performed along with regular school in order to ensure students’ access and continuity in regular education” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010b ).

Besides that, PNEE-EI, in 2008, in Brazil and, in 2010, in Espírito Santo, have generated a movement from the specialized institutions, with the closing of special schools and their change to CAEE. Between 2011 and 2013, the actions developed in the municipal and state networks were an attempt to make the guidelines stablished by the state resolution in articulation with PNEE-EI come true ( BRASIL, 2008 ).

The accreditation notice (2014-2016)

With the proclamation of Decree no. 7.611/2011 ( BRASIL, 2011 ), which provides on special education and AEE, we may observe an inflection on behalf of technical and financial support to the specialized institutions, in accordance with article 1, line VIII. The return of the term “preferably” expresses the pressures from groups from the National Congress and the Federal Government on behalf of the specialized institutions, as pointed out by Garcia Michels (2011), concerning the current special education policy.

This way, at the same time this new law moves forward in defining PAEE or in affirming of the political proposition in favor of school inclusion of this target audience, in a transversal and articulated way with regular education, it also goes back, when it opens space for the acting of specialized institutions in the educational context, especially in AEE.

In 2014, with Decree no. 92-R, there was one change in the way AEE is financed and its relation with specialized institutions in Espírito Santo. By this Decree, it has been stablished the accreditation of community institutions, religious or philanthropic nonprofit institutions, which would be responsible for AEE, in the extracurricular shift of the regular school, offered to students with disabilities and PDD from the state and municipal school networks ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014c ). The municipality that signed the technical cooperation term would not have the obligation of such offering.

In the Accreditation Notice, item 5 along with item 11, draw our attention,— Budget and price—, which informs the price (R$ 325,77 per student/a month) and from which source the funds for the expenses would come, that is, from “work plan: support to the institutions for specialized educational service” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014a ). This way, the resources would come from a separate budget in the education fund for the public financing of the activities in the community, religious, philanthropic or nonprofit institutions which perform in this type of teaching.

Annex I establishes that this notice and the subsequent signature of the technical cooperation term aim at “improving the conditions of the support to students who are the target-audience of special education” searching for a collaborative action that “aligns the institutional interests of the parties” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014a ). In brief: the public authorities transfer financial resources, outsourcing services, to the specialized institutions, which continue to keep their pre-eminence on PAEE education, diminishing, then, families concern regarding the lack of public services compatible to these individuals’ needs. It is the pact established behind closed doors, which affects the person with disability, transferring to the private sector his/her public right to education.

The excuse for this pact, disguised as accreditation and as pedagogical support, according to Resolution CEE/ES no. 2.152/10 ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010a ), is the need for hiring those institutions through their CAEE for the expansion of AEE offer, after the analysis reality needs by the Espírito Santo Educational Department (SEDU). It is possible to notice that it was necessary to establish requirements for hiring the specialized institutions, without prejudice to other partnerships that the state could establish with other public bodies (health and social care). In order to understand this context, it is necessary to go back in history a little, in the initiatives from the state government in its relationship with the private institutions in special education. Before that resolution, the support from the state government was characterized by the transfer of public funds in cash for the maintenance of the institutions, besides hiring the services of special education teachers, through annual recruitment process for temporary teachers, who were brought for teaching in those institutions. Because of this, concerning teachers, the social obligations, insurance and all direct and indirect taxes that used to be under SEDU’s responsibility, after the accreditation, became the institutions’ responsibility. At first, this accreditation notice came to standardize this public/private or, as mentioned previously, make a new pact behind closed doors. Such condition is more evident when Annex I of the accreditation notice states that the institutions do not have to worry about competing among themselves, once “hiring is assured to all” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2010a ).

It is also worth highlighting the topic of eating that, in this accreditation notice is the institution’s duty and that it will search for partnership with the municipalities. Another aspect refers to the choice of the place for AEE enrolment, which must be in accordance with the interests of the student/family. The family will present an enrolment proof in a regular public school, state or municipal, which will proceed with subscription in the SEDU/ School census management system.

This new financing policy establishes, in practice, a third enrolment, creating a kind of student-monthly-amount of R$ 325.77 offered to students who attend those institutions. This way, the student receives a double calculation from Fundeb, for being enrolled in both, regular school class and AEE in the extracurricular shift, offered in the school they study or in the nearest school, besides the third enrolment, if he/she is supported by the specialized institution in different days (and in opposite shift) from the supported that he/she receives in some public school unit.

It was also in 2014 that CEE approved Resolution no. 3.777 ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014b ), on May 8th, which establishes norms for education within the educational system in the state of Espírito Santo. In primary education, it is included in the special education modality, highlighted at chapter II. Different from Resolution no. 2.152/10, which pointed special education as a modality of education, Resolution no. 3.777/14 understands it as a modality of education that has the objective of ensuring AEE. AEE is understood as a “set of activities, access and pedagogical resources institutionally organized” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014b ).

Therefore, there is a change concerning what is special education, seen only as a service, responsible for AEE offer. We have also identified this change at national level, in Resolution no 4/09 and in Decree no. 7.611/11. Even keeping the principles of transversality, complementarity and supplementary, when establishing the offer organization, article 290 from state resolution emphasizes that special education is enabled by AEE, in relation with other modalities, such as indigenous education and education for the young and adult ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014b ).

In this resolution, it is also granted the functioning of the public network CAEE or of community, religious or philanthropic nonprofit institutions, with the objective of promoting participation and learning of students in regular classes ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2014b ). Resolution no. 3.777/14 in no moment suggests the implementation of a contract among the state and those institutions, neither the offer for third enrolment. Resolution no. 2.152/10 regulates the accreditation, but it does not mention third enrolment, either. We have to highlight that both documents declare that they are only a regulatory action.

Due to the accreditation notice, it has been noticed a conflict of technical nature, when we refer to the fulfillment of School Census, as well as of political-pedagogical nature, when, the student, at AEE offer, is fought over by specialized institutions in the public schools, creating then, an enhancement of the public/private relation from the financialization/ commercialization of the PAEE individual. The solution adopted for solving this problem was the writing, for two consecutive years, of the technical cooperation term, led by the state government to the municipalities, which has favored even more the private domain.

The Technical Cooperation Term (2017-2018)

From the signature of the technical cooperation term, condition required by the accreditation notice, so that students from the municipal networks could receive support, we began to experience the third moment in the special education policy in Espírito Santo. Even though the technical cooperation term had been foreseen since 2014 and signed since 2015, it as from the turn from 2016 to 2017 and its repetition in 2017 to 2018 that SEDU and the specialized institutions started to demand from the municipalities the execution of the cooperation term. In this moment as well, teachers, in special those from the AEE municipal networks, noticed the absence of their students and looked for clarifications with the competent bodies and families concerning such situation.

Then, when public administrators were questioned whether or not they had signed any technical cooperation term with the state government, 37 of them answered that their respective municipalities had signed the term, however, most of them declared that they were not aware of the provisions presented by the document. Fourteen of them said that their municipalities had not signed the term: “Not that I know of, I looked for information, but I could not obtain any piece of information on this partnership”. The other administrators did not answer or declared not knowing anything about that matter: “I do not know. We would like to receive guidance about it” and “We do not have any information about it”. We highlight that four municipalities did not answer this question.

Therefore, we might consider that it is a political matter concerning the relationship between the city goverments and the state government, without discussing the matter with civil society, considering that the public administrators, families and the social movements did not take part in the process, nor have them debated the consequences of this type of partnership for AEE financing and quality in the educational public systems to PAEE.

At this point, we cannot forget the context of crisis in which the country is. For instance, the amount of R$ 325.77 has not undergone any monetary correction since 2014, in spite of the increased inputs. The resources transferred, thus, did not assure enough financial support to the institutions. Apart from that, with the same enrolment of the student in the specialized institution, the second enrolment was being charged in the public school, once he/she was also enrolled there, recorded in the school census. On this regard, it was necessary that the specialized institutions and the state government required other sources of funds in order to maintain the affiliation ensured in the accreditation notice. This way, in 2016 the 1st additive term came out, with the objective of changing the technical cooperation terms signed with the municipalities. According to this additive term, in the responsibilities section, the municipality

[...]will forfeit from the resources related to the 2nd enrolment of the students of the municipal education network, regarding AEE of students who choose to attend CAEE of the institutions, which will be passed and managed by the State. ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2016 ).

Thus, the municipality should expressly give up the resources of the second enrolment, in benefit of the private institution in special education. In 2018, the value of the second enrollment was fixed at R$4,124.03 per student/year for Espírito Santo, in accordance with the notice of the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC). Besides that, unlike the accreditation notice, the municipal government should also bear the costs derived from transportation and food for the students enrolled at CAEE. At last, the city governments should pay for the amounts over the monthly expenses. — second enrollment, plus 10% on that amount—, to be payed to the specialized institutions ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2016 ).

Due to the doubts and questions that have emerged, specially from the second enrollment abstention from the municipalities, the State Education Department (SEDU) has published Technical Note no. 001/18, explaining the 2nd additive term, which does not differ from the first one at all, mentioning, for this purpose, the New Joint Technical no. 01/17 (SEB– Basic Education Department, SECADI- Continuing Education; Literacy and Inclusion Department; SETEC/FNDE- Professional and Technological Education Department/ National Fund for Education Development), as far as special education is concerned: “When schooling is one or many in the same sphere in the government and AEE is affiliated to only one sphere in the government, it will be taken into account the enrollment in the government sphere of the agreement” ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2018 ). However, at the end of the explanation of the topic, the public body highlights that this guideline is valid for the student who is enrolled in the affiliated institution, but not in the resource room.

In spite of being aware of such guidelines, the specialized institutions have been alluring or even coercing families in order for them to take children to these institutions’ AEE, using the argument that they will not get the clinical treatment from specialists at public institutions, according to reports of the families during the National Popular Conference in Education (CONAPE), held in Espírito Santo, and in the meeting of the Permanent forum on Inclusive Education, of the Federal University in Espírito Santo. Considering the difficulties in finding specialized professional in the public network, families, even against their will and besides the distance from the institution to the AEE, sign the commitment term, giving up this service in the public school. It is worth remembering that specialized institutions already receive funds from public bodies of Health and social care. It is clear that the responsibility for the realization of a public right is transferred to the private sector sphere when the municipality not only gives up a significant amount of public money, but also takes away from its treasure an amount for input on transportation and food.

These additive terms completely change the characteristics of the technical cooperation term which had been previously signed between the state government and the municipalities for the payment of expenses concerning CAEE enrollment. Through this cooperation term, as for the obligations, the municipalities did not have to give up the second enrollment, despite being established they should bear the costs on transportation and food.

Thus in the State context, the policy on transferring resources to private institutions, affiliated and/or philanthropic have been implemented, exempting the public power from its responsibility on ensuring schooling in the regular school. This way, the state government decides to prioritize the outsourcing under a managerial5logic, which manages the demands under the logic of the lowest cost, while we see the precarious situation of the public services. In our specific case, there is an ongoing a process of significant decrease of AEE offer in the state public educational networks, articulated with the intentional and premeditated protagonism of the service by the affiliated and/or philanthropic private institutions.

Special Education Enrollments: Brazil and Espírito Santo (2008 to 2018)

For the analysis of the existing relation between the special education policies conducted in the state and federal spheres, as well as the offer of this type of education in Brazil and in Espírito Santo, we present the path of the enrollment in special education in the context of basic education, in the period from 2008 to 2018.

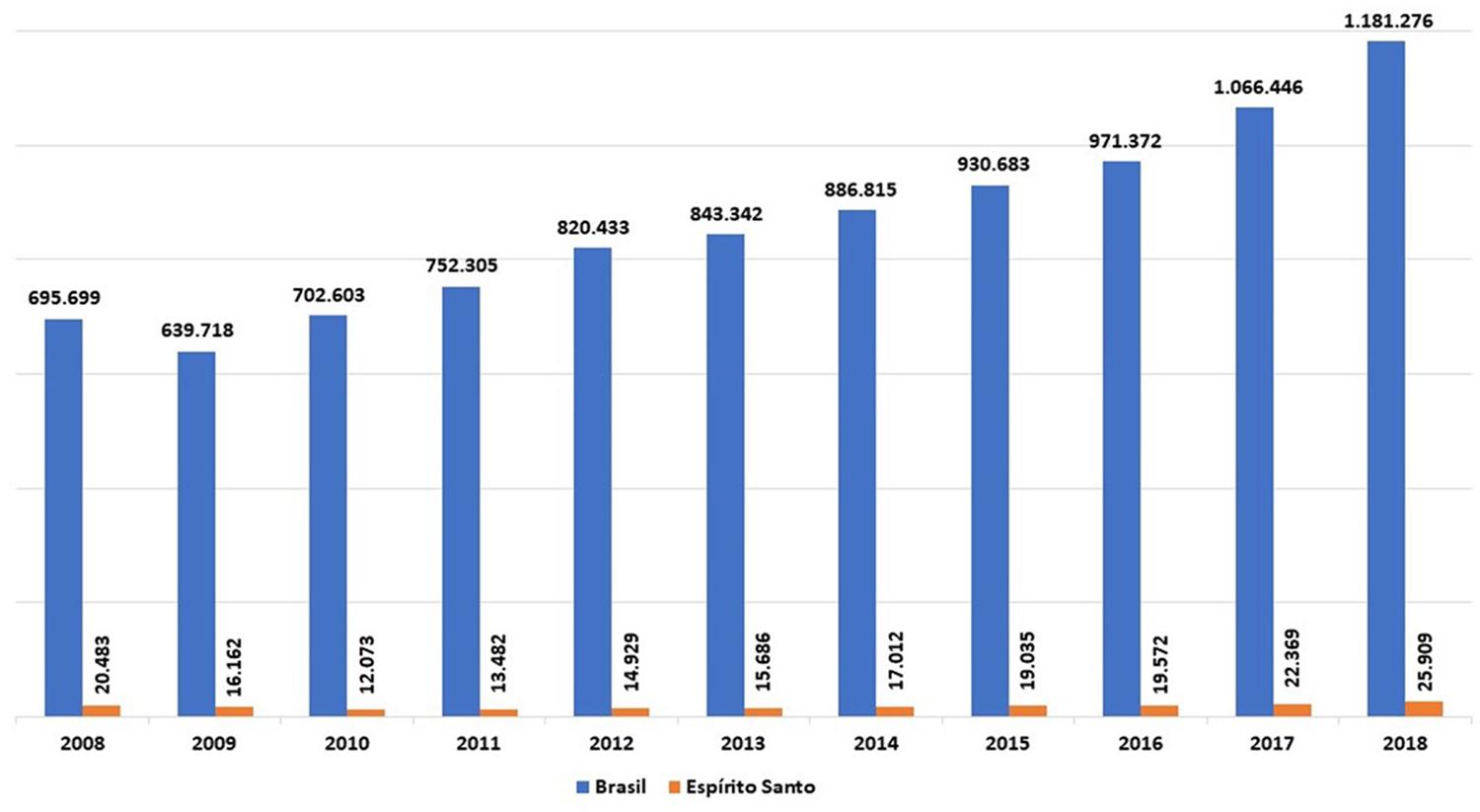

We note that, from 2008 to 2018, although the enrollments in special education in Espírito Santo and in Brazil match the year-after-year movement tendency, the percentages of increase are significantly different. While in Brazil this increase represents 53%, in Espírito Santo it corresponds to 9%. It is worth highlighting that the enrollment decrease in the year of 2009 might be understood from the changes for adjusting the methodology and data collection instrument f school census, whose effect has reached the school networks at the national level.

These results point out the expansion of enrollments in special education in the Brazilian educational systems, motivated by the policies in special education throughout this decade. Thus, we agree with Garcia and Michels (2011 , p. 116) when they state that there is a clear movement for state intervention in the educational policy regarding PAEE education, through “the presence of the State in the creation of public education equipment for special education” in the state and municipal education networks, although the new law assures that AEE can also be performed by private nonprofit institutions

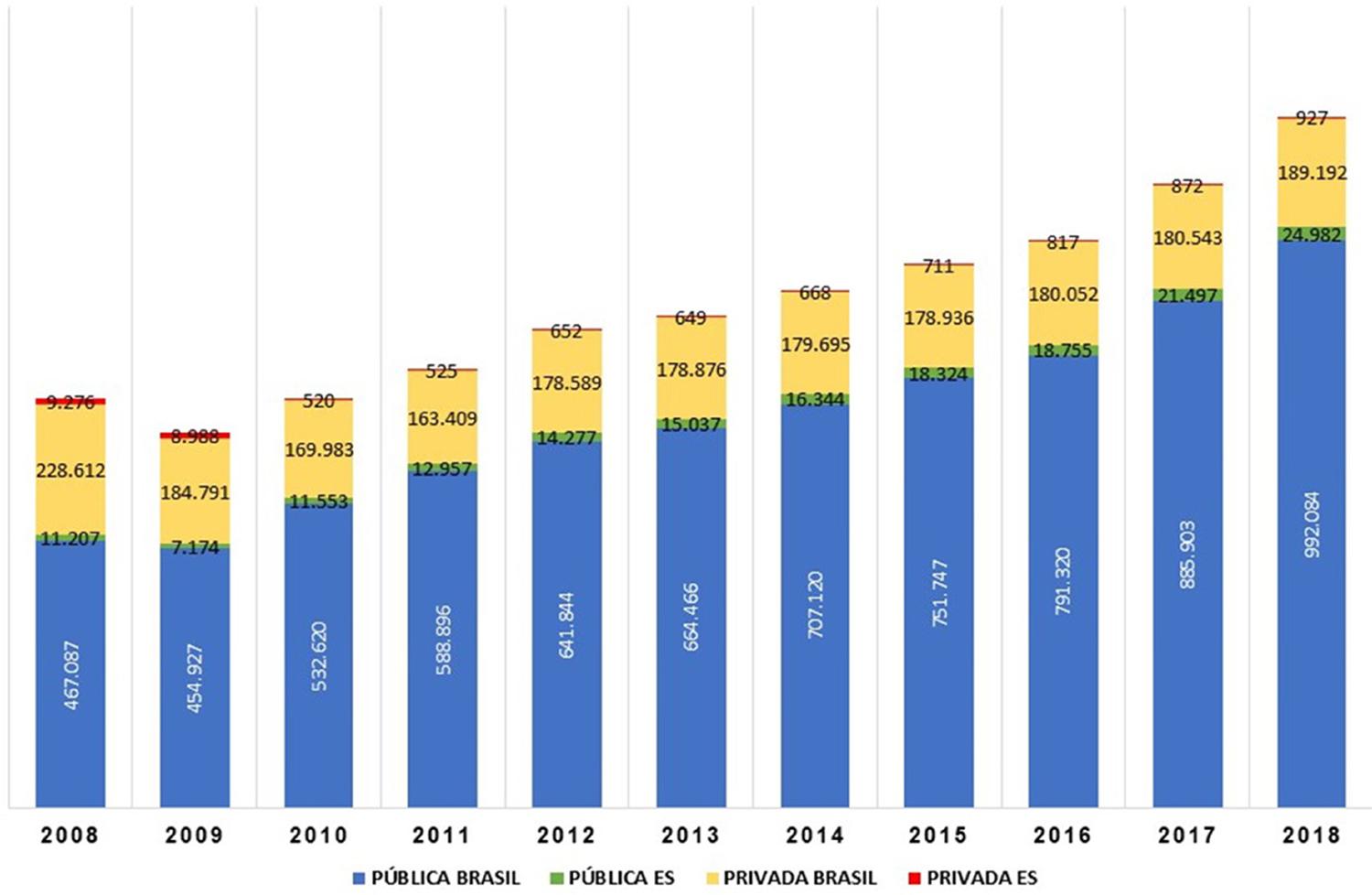

On that path, the structure of PAEE service in Brazil and in Espírito Santo in public and private school reflects significant changes. This scenario might be ratified when observing that the increase in the total number of enrollments in special education in Brazil and Espírito Santo, occurs, especially, in the public education network, as shown in Graph 2 .

Source: The National Institute for Educational Research and Study INEP/Sinopsys of statistics 2008 to 2018. Our own production (2018).

Graph 1 – Enrollments for special education in Brazil and Espírito Santo – 2008 to 2018

Source: The National Institute for Educational Research and Study INEP/Sinopsys of statistics 2008 to 2018. Our own production (2018).

Graph 2 – Enrollments in special education in public and private institutions– Brazil 2008-2018

If, in 2008, there is 33% of enrollments in special education in the private education network in Brazil and 45%, in Espírito Santo, in 2018 this percentage decreases to 16% and 4%, respectively. On the other hand, the percentage in the public education network, in 2008 is of 67% in Brazil and 55% in ES and in 2018 this percentage reaches 84% and 96%, respectively.

In Espírito Santo, we observe a decrease in the number of enrollments in the private education network from 2008 to 2011 and an increase from 2012 on, except 2013. In accordance with Laplane, Caiado and Kassar (2016 , p. 48), “besides the decrease of absolute numbers of enrollment in exclusive schools in special education, the private sector has been increasing proportionally in this type of service.

The distributions of the total enrollments in special education per Administrative Dependence show that the federated entity to take on predominantly the offer of this modality in Brazil is the municipal sphere. It is worth highlighting the number of enrollments in special education in the private sphere, which showed a decrease in the period from 2008 to 2011, but an increase from 2012 on (from 178,589 to 189,192 in 2018).

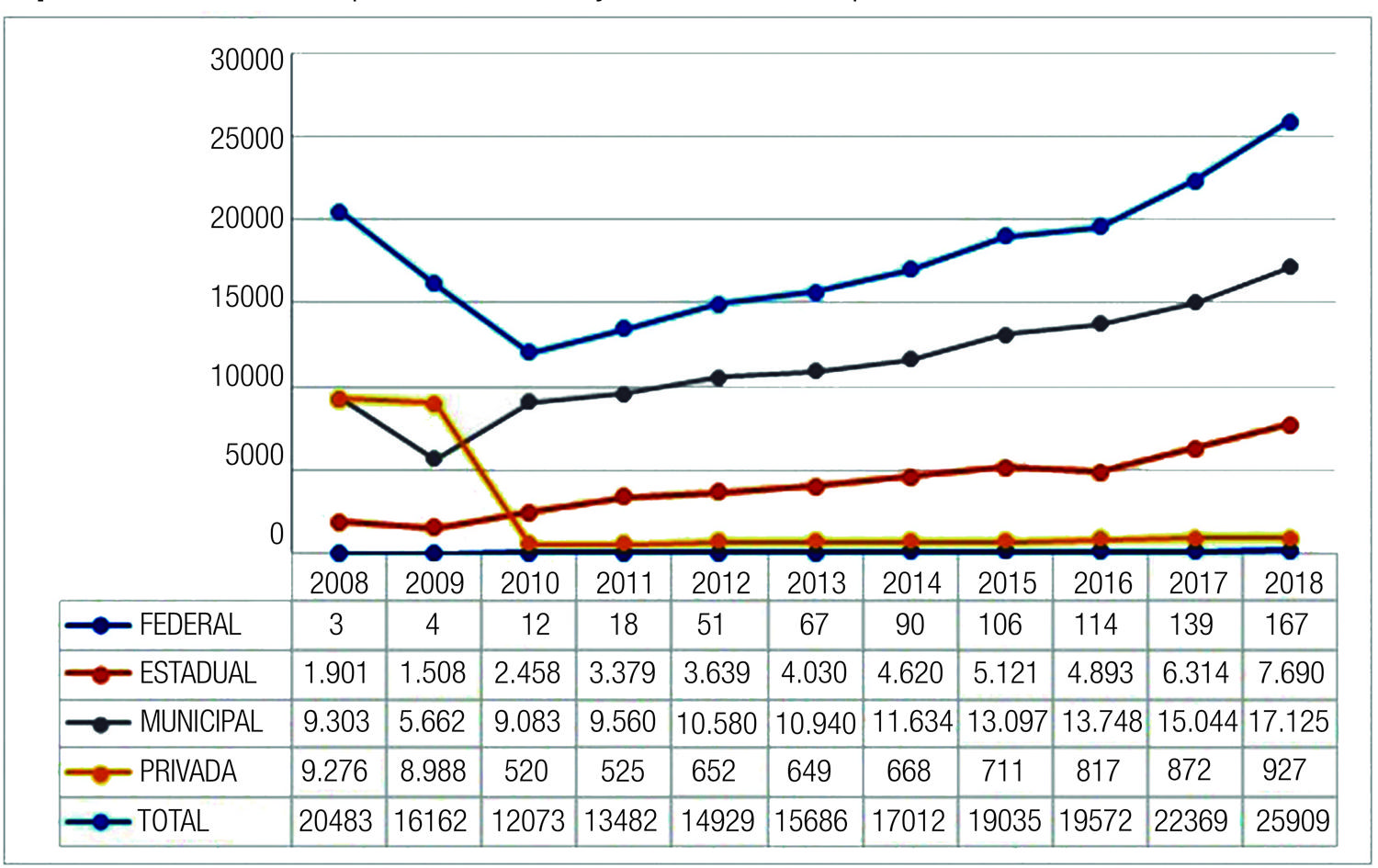

In Graph 3 , we conclude that, in general, the state, federal and municipal spheres of Espírito Santo present an upward trend of special education offer in this period, except for 2009, in the state and municipal networks case, which might be understood because of the changes in the census recording methodology by the Anisio Teixeira National Institute of Study and research in Education - INEP.

Source: The National Institute for Educational Research and Study INEP/Sinopsys of statistics 2008 to 2018. Our own production (2018).

Graph 3 – Enrollments in special education by Administrative Dependence – ES 2008-2018

The path of enrollments in special education in the private sphere presents two significant movements. From 2008 to 2010, it presents a decrease of 94%, which could represent the increase in PAEE enrollments in the public educational system. However, from 2011 to 2018, we identify an increase of 77%, which reveals a support expansion from the private systems for this modality of education in the state. Also, Oliveira (2016) emphasizes the increase in the number of enrollments in the private institutions for special education in Espírito Santo, with more emphasis from 2014 on, after the change in the relationship between the state and those institutions, through agreement for AEE service, which resulted in the increase of public resources destined to them as well. This result confirms the study of Laplane, Caiado and Kassar (2016) , according to which the private sector remains in the exclusive/special educational forms, with the need of public resources. From this perspective, it is clear that the enrollments for special education in Espírito Santo, per Administrative Dependence, follow the same trend of the national level, with the predominance of the municipal sphere.

Concerning the offer of this modality in Brazil and in Espírito Santo, it is possible to observe the expansion of PAEE enrollments in the Brazilian educational systems. However, this does not diminish the relevance of discussing the minimal quality conditions of the public educational network for supporting this population, which has been historically excluded from the schooling process. It is equally necessary to draw attention to the enrollment number in the private educational network.

Final considerations

The analysis carried out in this study points out that the policies in special education in Brazil and in Espírito Santo derived from disputes, negotiations and correlations of political forces from different social groups within the state context. In this respect, they show nuances and contradictions, considering that, at the same time that they assure inclusion to PAEE in regular education, they also establish technical and financial support to private nonprofit institutions that work with special education. According to Gramisci’s perspective, it is possible to include such policies in the liberal and instrumentalist reading of civil society, private institutions in special education have gained relevance throughout history and now have a decisive role in the relationship between the state, PAEE and the public educational policies.

Going back to the Gramsci (2004) equation, “State = political society + civil society”, we observe that specialized institutions are part of the State, for they form civil society as well in dialectic relationship with political society. They do not act apart from the State, but within the State and with the consent of groups inserted in the government. Because of this, it is easier to understand the reason why those institutions are given certain centrality in PAEE education They are many times associated to the poor conditions of the public finances and to the precarious situation of the public education networks. This way, seeking to dialog with the neoliberal capitalist ways, the neoliberal State is minimum concerning financing public school, with commercialization and decentralization actions, discharging itself from social issues. Concerning the increase of public administration action in PAEE, specialized institutions continue to be focused on, while we watch the precarious situation of public services. On the other hand, this reality makes us sure that there still is a lot to be done concerning special education in Brazil and in Espírito Santo.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Decreto nº. 7.611, de 17 de novembro de 2011 . Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: [s. n.], 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2011/Decreto/D7611.htm>. Acesso em: 7 set. 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução nº 4, de 2 de outubro de 2009 . Institui Diretrizes Operacionais para o Atendimento Educacional Especializado na Educação Básica, modalidade Educação Especial. Brasília, DF: CNE, 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva . Brasília, DF: MEC, 2008. [ Links ]

CHIZZOTTI. Antônio. Pesquisa em ciências humanas e sociais . 9 ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Diretrizes da educação especial na educação básica e profissional para a rede estadual de ensino . Vitória: SEDU, 2010b. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Edital de credenciamento nº 001/2014 . Vitória: SEDU, 2014a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Nota técnica nº 001/2018 . Vitória: SEDU, 2018. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Resolução nº 2.152, de 7 de janeiro de 2010 . Dispõe sobre a Educação Especial no Sistema Estadual de Ensino do Estado do ES. Vitória: SEDU, 2010a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Resolução nº 3.777, de 8 de maio de 2014 . Fixa normas para a Educação no Sistema de Ensino do Estado do ES, e dá outras providências. Vitória: SEDU, 2014b. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Termo aditivo nº 011/2016 . Vitória, SEDU, 2016. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Instituto Jones dos Santos Neves. Divisão regional do Espírito Santo: microrregiões de planejamento. 1 mapa, color. Escala 1:200.000. 2019. Disponível em: <http://www.ijsn.es.gov.br/mapas/#inicioPagina>. Acesso em: 2 maio 2019. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação. Portaria nº 92-R, de 21 de maio de 2014 . Estabelece o credenciamento de instituições comunitárias, confessionais ou filantrópicas sem fins lucrativos para o Atendimento Educacional Especializado, no contraturno do ensino regular, aos alunos com deficiência, transtorno global do desenvolvimento, altas habilidades/superdotação. Vitória: SEE, 2014c. [ Links ]

FEIJÓO, José Carlos. O estado neoliberal e o caso mexicano. In: LAURELL, Asa Cristina (Org.). Estado e políticas sociais no neoliberalismo . São Paulo: Cortez, 1995. p. 11-52. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Rosalba Maria Cardoso. Discursos políticos sobre inclusão: questões para as políticas públicas de educação especial no Brasil. In: REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO E PESQUISA EM EDUCAÇÃO, ANPED, 27., 2004, Caxambu. Anais eletrônicos... Caxambu: Anped, 2004. Minicurso – GT15. 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/t1510.pdf>. Acesso em: 21 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Rosalba Maria Cardoso; MICHELS, Maria Helena. A política de educação especial no Brasil (1991-2011): uma análise da produção do GT15 – educação especial na ANPED. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial , Marília, v. 17, p. 105-124, maio/ago. 2011. [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, Antônio. Cadernos de cárcere . v. 3. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2004. [ Links ]

LAPLANE, Adriana Lia Friszman de; CAIADO, Katia Regina Moreno; KASSAR, Mônica de Carvalho Magalhães. As relações público-privado na educação especial: tendências atuais no Brasil. Revista Teias , Rio de Janeiro, v. 17, n. 46, p. 40-55, jul./set. 2016. [ Links ]

MENDONÇA, Sônia Regina de. Estado e políticas públicas: considerações político-conceituais. Outros Tempos , São Luís, v. 1, p. 1-12, 2007. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Gildásio Macedo de. Financiamento das instituições especializadas na política de educação especial no Estado do ES . 2016. 144 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2016. [ Links ]

POULANTZAS, Nicos. O Estado, o poder, o socialismo . 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 2000. [ Links ]

2- The state of Espirito Santo comprises an area of 46.078km2 where a population of 3.512.672 inhabitants is concentrated, according to the 2010 IBGE Census (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics).

3- The regional area of Espirito Santo comprises the following micro- regions: Metropolitan region, Região Metropolitana, Central montaneous, Southwest Montaneous, South Litoranean, South Central, Caparaó, Rio Doce, Central- West, Northeast, Northwest. ( ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2019 ).

5- We understand outsourcing as a process of transferring of the public services, special education, in this particular case, which should be performed by the governments to the specialized institutions that focus on the support to people with disabilities. This model exempts the State from the obligation of performing the role assigned to it, being assigned only the duties of management and supervision.

Received: November 30, 2018; Revised: April 09, 2019; Accepted: May 08, 2019

texto en

texto en