Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 14-Oct-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945217423

THEMATIC SECTION: SPECIAL EDUCATION

Public policy, Special Education and schooling in Brazil *

1- Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Contact: baptistacaronti@yahoo.com.br.

The text aims to analyze the schooling of people with disabilities in Brazil, considering the period 2008-2018 as a priority and based on a public policy that assumes school inclusion as a guideline for action in the different spaces of educational management. The National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008 is understood as part of a historical moment that brings together Brazilian initiatives and guidelines with international propositions that announce a resignification of the concept of disability – affirmation of the social perspective –, as indicated by a new institutional design to guarantee the right to education. Who are the social actors with a relevant role in this process? What are the main achievements and main challenges? How to analyze the possibilities of reconfiguration in terms of pedagogical instruments and educational spaces? Such questions are part of the qualitative study performed based on documentary analysis, which considers the normative plan and the review of specialized literature. The analysis indicates that there was increase of enrollment of students with disabilities in ordinary education, besides the approval of great number of normative instruments on the subject. There was also the establishment of programs aimed at various forms of specialized support, showing a locus shift focused on these students’ schooling, prioritizing the ordinary education. Nevertheless, there are coexisting trends that reaffirm and contradict the perspective proposed by the guidelines analyzed, especially when considering the qualitative dimensions of the formative processes.

Key words: Special Education; Public policies; School inclusion; Person with disability

O texto tem como objetivo a análise da escolarização das pessoas com deficiência no Brasil, considerando prioritariamente o período 2008 a 2018, em função de uma política pública que assume a inclusão escolar como diretriz para a ação nos diferentes espaços da gestão educacional. A Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva de 2008 é compreendida como parte de um momento histórico que aproxima as iniciativas e as diretrizes brasileiras de proposições internacionais que anunciam uma ressignificação do conceito de deficiência – afirmação da perspectiva social -, assim como indicam um novo desenho institucional para a garantia do direito à educação. Quem são os atores sociais com papel preponderante nesse processo? Quais são as principais conquistas e os principais desafios? Como analisar as possibilidades de reconfiguração em termos de dispositivos pedagógicos e de espaços educativos? Tais interrogações integram o estudo de natureza qualitativa, realizado com base na análise documental, que considera o plano normativo e a revisão de literatura especializada. A análise indica que houve ampliação das matrículas de alunos com deficiência no ensino comum e a aprovação de elevado número de dispositivos normativos sobre a temática. Houve também a instituição de programas dirigidos a formas variadas de apoio especializado, mostrando um deslocamento do lócus destinado à escolarização desses alunos, com prioridade para o ensino comum. Apesar disso, coexistem tendências que reafirmam e que contradizem a perspectiva proposta pelas diretrizes analisadas, principalmente quando são consideradas as dimensões qualitativas dos processos formativos.

Palavras-Chave: Educação especial; Políticas públicas; Inclusão escolar; Pessoa com deficiência

Introduction

Over the past decades, the international debate on the schooling of people with disabilities has become visible in the sphere of social policies, generally as an extension of schooling in a broad and compulsory process for all children. This paper aims to analyze the schooling of people with disabilities in Brazil, considering the period 2008-2018 as priority and based on a public policy that assumes school inclusion as an educational guideline.

In the Brazilian context, we can say that the last 50 years have produced changes that, depending on the analysis perspective, seem to evoke major ruptures with the established practices, or show that, despite superficial changes, what exists is the continuity of the usual ways to conceive the person with disabilities2 and to propose, for these subjects, educational paths that are essentially the same as those offered in previous decades. This polarization is easily recognized when we analyze the specialized literature on special education in Brazil. How to evaluate this historical process in our country? What evidence can be considered to identify if any production of the new occurs or if there is only different varnish for old approaches? How to understand the different historical moments that mark the Brazilian special education? Are there times when this education was associated with effective schooling processes?

If we take schooling as an analytical principle, which signs should be valued to identify the occurrence of changes? It is a broad universe of questions that could not be fully answered in a brief set of reflections that characterize this academic text. However, these are triggering questions, considered important to affirm the initial understanding that both continuity and rupture are marks present in Brazilian special education. I consider that the phenomena that could be associated with the idea of rupture, and of affirmation of the new, have advanced in an oscillating mode and have been permeated by challenges arising from continuous struggle as a feature of public policy decision-making processes. It is essential to remember that, despite the historical precariousness of services and the predominance of welfare and philanthropy, special education is a field of mobilization and gain for social groups which announce themselves as their advocates. Such gains translate into occupation of public space, mastery of alternatives of formation and freedom in the search for economic resources that are not always the target of public control due to the institutional autonomy of the proposers. It is a process that also ensures the expansion of political power through action of elective representativeness in different communities. We can identify the existence of actions directed to complementarity, with reciprocal advantages for private-philanthropic institutions and public agencies. It is important to recognize that this convenient complementarity allowed the State to save – as it did not assume the schooling of this portion of the population – and the other responsible institutions to strengthen their centralizing role in the process.

In order to discuss the potential elements of novelty and disruption in Brazilian special education, I intend to initially recover a brief historical route, identifying the phases that mark the progress of state initiatives in the provision of services. Subsequently, the period related to the last ten years will be analyzed in order to identify possible challenges for the future of this area of knowledge.

Throughout the text, and according to Muller and Surel (2002) , public policy is understood as a continuous process associated with public action, contemplating, in a predominant way, a production flow of “public action programs, that is, political-administrative instruments at first coordinated around explicit objectives” ( MULLER; SUREL, 2002 , p. 10). As stated by these scholars, public policy is not intended to solve problems.

In fact, the problems are “solved” by the social actors themselves through the implementation of their strategies, the management of their conflicts and, above all, through the learning processes that mark the whole process of public action. In this context, public policies have as their fundamental characteristic the construction and transformation of spaces of meaning [...]. ( MULLER; SUREL, 2002 , p. 28, emphasis added).

It is an analytical perspective that differs from sequential approaches and can be associated with the cognitive approach to policies in order to conceive the implementation of policies as a collective learning process. When presenting this approach, Muller and Surel (2002) highlight the pursuit of understanding public policies as cognitive and normative matrices that constitute systems of interpretation involving social actors as subjects of a continuous process.

The study is developed based on the methodology of documentary analysis, performed from evaluation of normative instruments, guidelines expressed in public documents and academic studies resulting from research, which help us in the analysis of the phenomena in question. Regarding the analytical work, considering the importance given to the production of meaning, there is a clear proximity to the perspective of political discourse analysis proposed by Pinto (2006) , when the author discusses the relationship between social actors, the processes of interaction, and the delineation of historical flows. From the operational point of view, the documents chosen were read successively in order to identify the nodes of meaning that articulate with the general objectives of the investigation. Such procedures involved normative documents, guidelines and academic papers. I emphasize that some documents assumed a structuring role in the elaboration of the text, since they were explicitly related to our searches. I refer to normative documents as resolutions (BRASIL, 2009a) or decrees (BRASIL, 2009b, 2011); documents that make the guidelines explicit ( BRASIL, 1994 , 2008 ); or balance sheets and summaries proposed by managers ( BRASIL, 2002 , 2016 ).

As previously cited, a historical analysis will be presented in order to understand trends and priorities. It is worth mentioning that this historical rescue has played a major role in the investigative process, as the identification of these marks helped us discuss the most recent moments of Brazilian special education.

A brief look at history

It is possible to affirm that there was consolidation of special education in Brazil predominantly throughout the second half of the twentieth century. This process can be interpreted from different indications, such as the expansion of services, political initiatives at the various levels of public management, and the expansion of academic debate on the subject. When we think of the consolidation of special education in Brazil, it is possible to identify occurrences that are often presented as milestones throughout history. The first step is usually indicated by the founding of the first institutions aimed at people with hearing and visual impairment, in the nineteenth century ( BUENO, 1993 ). When we focus on other types of people with disabilities, there were moments of delineation of identification of the so-called “abnormal” children from their apparent incapacity for school learning, with initiatives of a clinical and highly selective pedagogy, marked, for example, by the arrival of the Italian doctor Ugo Pizzoli to train professionals in the municipality of São Paulo in the early twentieth century ( KASSAR, 2011 ). Between the 1930s and 1950s, there were important initiatives by private-care institutions that structured an action in which education was evoked as a goal, despite the predominance of a set of initiatives related to care and health care. It was a time of absence of public services for people with disabilities, and such institutions – Pestalozzi and Apaes – imposed themselves as a kind of substitute apparatus for state action. The history of these institutions is widely approached by the specialized literature and, in the case of Apaes, I highlight the work of Jannuzzi and Caiado (2013) , which allows us to know how this association became a network and a federation with power in different public management instances. Besides its growth in terms of care units, representation groups and branches with the political representatives, we can realize that this institution – Fenapaes – has great ability to change and fit the different moments of the history of Brazilian education, incorporating, when necessary, discourses defending the school or inclusion as long as these discourses maintain its hegemony as institution parallel to the state, identified as a priority partner and holder of knowledge of special education in Brazil.

The institutionalization of special education that has taken place in the country since the 1950s consolidates not only the detachment of the state with regard to the education of people considered to be disabled, but also the privatization of education, social assistance and health of this population, according as it adds global service to its specialty. ( MELETTI, 2008 , p. 2).

This global service tends to be one of the elements that help us understand the strength of these institutions, as they offer services – social assistance and health – that are added to those with educational characteristics, which are not always accessible in public initiatives. State support directed to these institutions, through the provision of professionals or transfer of resources, feeds this cycle, favoring the dynamics of offer responsibility by private institutions.

In his analysis of Brazilian special education, Kassar (2011) shows us that, after the 1964 military coup, there was a revision of the education guidelines, including the expansion of compulsory schooling to eight years, through Educational Law No. 5.692 of 1971. This law can be considered a milestone in the expansion of special education services because it broadens the scope of action in this area in terms of involving not only students with disabilities, but also including those with learning disabilities expressed in the idea of considerable delays regarding the regular age of enrollment. This understanding favors the expansion of special education classrooms and legitimates, through this instrument, a phenomenon that has remained in the constitution of special education services, since, for a larger numerical contingent of students in special education classrooms – students with intellectual disabilities –, there is a diagnostic inaccuracy associated with instrument typologies or with methodologies used. This phenomenon is not recent and was already analyzed by Ferreira and Nunes (1993) , who highlighted the complexity of the initial assessment of mental/intellectual disability. In fact, these scholars state that the issue of referral to special education services has been the subject of dissertations and theses, which allows us to conclude that: children from families with low socioeconomic status are overrepresented in special education classrooms; there are limitations of diagnostic instruments and referrals are arbitrary; students in special education classrooms are unlikely to return to ordinary education classrooms, despite the orientation in institutional plans and legal provisions. These are statements that, although made in 1993, remain extremely relevant.

The special education classrooms had the state systems as priority space, which indicated an expansion of public services, although subject to the reflections already presented. There was proliferation of criticism about this service, indicating that there was enrollment of students who did not present disabilities, but school difficulties ( SCHNEIDER, 1977 ), and that the school trajectory of students in these classrooms showed no connection with ordinary teaching, since there was a tendency of long years of permanence in this type of classrooms.

The early 1970s was also characterized by another public sector initiative that reaffirmed special education as part of Brazilian management: the creation of the National Center for Special Education – Cenesp –, in 1973 ( BUENO, 1993 ). It was an initiative, supported by US consultants, that inaugurated an institutional space for special education in the Ministry of Education, with the objective of “regulating, disseminating, fostering and accompanying Special Education in Brazil” ( KASSAR, 2011 , p. 68).

Therefore, the 1970s marked a time for expansion of public services, such as special education classrooms, and the insertion of special education in the sphere of public management through Cenesp, which will later be transformed into a Special Education Secretariat (SEESP).3 At this historical moment, there was predominance of a conception related to conditioned schooling, because, depending on the student’s limitations, the referral should indicate the service – special education classroom or special education school – generally substituting ordinary education.

In the case of NGOs, it is a question of bringing to the ordinary education schools those students who are able to attend them, even in special education classrooms . Thus, private and philanthropic schools would specialize in serving those students who, due to their characteristics, are unable to attend the government network. At least for now ... ( CARVALHO, 1993 , p. 95, emphasis added).

By highlighting students who “due to their characteristics, are unable,” the text above expresses a set of ideas still frequent today in special education, despite the international debate related to the social model of disability ( MAIOR, 2018 ). The understanding that the limitations are not in the people but in their encounter with a context that can intensify or minimize the perception of impediments that would be insurmountable is still an idea in process of affirmation.

The possibility of inserting students attending special education schools in special education classrooms of the public system was announced as a proposal to improve the system that should ensure that the special education schools – understood as those private and philanthropic – would take care of those students who “are unable to attend the government network” ( CARVALHO, 1993 , p. 95). These ideas are expressed in an Inep thematic magazine – Em aberto , no. 60, 1993 – published shortly before the approval and dissemination of the 1994 National Policy on Special Education ( BRASIL, 1994 ). This thematic magazine is an important historical record for bringing a set of texts that analyze special education, as a kind of synthesis of the 1970s and 1980s. Still on the special education classrooms, in this same magazine, a scholar who occupied the role of manager at that time refers to these services: “At least one Special Education classroom in each school is our motto” ( CARVALHO, 1993 , p. 95). Therefore, according to the then secretary of special education of the Ministry of Education, the advance would be the existence of special education classrooms in all ordinary education schools, although, at another point in the same text, the author states that “we are concerned about inappropriate referrals of students who not necessarily present some disability to special education classrooms” ( CARVALHO, 1993 , p. 95).

For a long time, as it still occurs today, there was widespread understanding that the problem of schooling of students with disabilities would be associated with their supposed lack of capacity, translating into one word: referral. This idea seems to be based on the assumption that, if appropriate care was taken, we would be protected from all that which was frequent: children referred to special education classrooms, early and without diagnosis. Similarly, reductionist and eternally preparatory tasks for schooling would be reduced to a referral issue. That is, the real disabled were not exactly those indicated. It would be necessary to better identify those students and then direct their education to the special education classrooms, which, in turn, should increase numerically. I consider this to be a fallacy, since there is no instrument dissociated from its history. The special education classroom, due to its existence, contributed to the configuration of a group destined for this service, because, from the existence of this type of classroom, the school has now a place to refer those who are not according to the condition of student considered ideal.

A similar reflection may be associated with special education schools. I consider it fundamental to admit that we have few productions that evaluate the effects of the school trajectories of the students of these schools, in terms of learning and social participation capacity (SILVA; ALMEIDA; CAIADO, 2017). The work that seeks to find elements for the analysis shows that there are long permanence times and large gaps in school learning for students of special education schools organized as private-philanthropic institutions, even when reading and writing are considered basic requirements ( ALMEIDA, 2017 ). The work of Silva Jr. (2013) analyzed the school trajectory of 427 students from special education municipal schools of Porto Alegre, enrolled in 2012. This study showed that these students stayed eight years, on average, in these schools, with no transit between specialized and ordinary education.

Returning to the historical dimension, what happens after the 1980s will be a progressive but moderate expansion of the schooling guarantee. It is the moment of political openness after the long 21-year period following the 1964 military coup. During this period, we also had the International Year of Disabled Persons, organized by the UN in 1981, and an intense movement in defense of the rights of people with disabilities ( MAIOR, 2018 ). In 1985, Cenesp was transformed into a Special Education Secretariat in the Ministry of Education. It is also worth highlighting the 1988 Federal Constitution, the citizen constitution, for its emphasis on democratic processes and the defense of the expansion of social rights. Internationally, there were conventions spreading an intensifying idea of the right to schooling of people with disabilities in ordinary education, such as the 1994 Salamanca World Conference on Special Needs Education. That same year, as noted earlier, the 1994 National Policy on Special Education was approved, which reaffirmed the principles of the so-called integration, maintaining the proposal for a wide range of services that reaffirmed the differentiation of paths and the maintenance of spaces substituting ordinary education – special education classrooms and schools.

The period from 1994 to 2002 can be analyzed through a document from the Ministry of Education ( BRASIL, 2002 ), entitled Special Education Policy and Results, 1995-2002. It is a very enlightening text, because it makes a kind of analysis of the period, indicating the dimensions that were presented as advances. In addition to a brief history, the text presents a set of evaluations and assumptions that indicate a predominant trend, expressed, for example, in the following statement:

Inclusive education demanded a radical change in educational policy and required a complete restructuring of management and educational actions throughout the system. Special education is no longer a parallel system of education and is definitely inserted in the general context of education. ( BRASIL, 2002 , p. 12).

Despite the forcefulness of these statements, when we analyze the effective actions and indicators proposed by the document, we can identify that the changes were present, but still in the process of establishing a public policy. For example, a project that develops actions related to inclusion in five schools in Mato Grosso do Sul is approached. The document lists actions such as those involving universities – Proesp/Capes Special Education Support Program – as well as training initiatives for professionals in the areas of hearing and visual impairments in different municipalities. By listing the actions related to training, the document highlights the partnership with non-governmental organizations “representative of the various segments” ( BRASIL, 2002 , p. 16). This emphasis on private-philanthropic institutions emerges as the reaffirmation of assumptions that strongly characterized the 1994 National Policy on Special Education ( BRASIL, 1994 ), as it is a perspective of public action present in much of the goals and guidelines proposed by that historical document. Therefore, the expansion evoked in this analysis in 2002 would be centered on the combination of efforts between public and private sectors, as historically occurred until that moment.

It is important to remember that this is a moment governed by the guidelines of the 1994 National Policy on Special Education, which clearly indicates in its goals that there will be the “participation of students with disabilities and typical behaviors in classes of ordinary education whenever possible” ( BRASIL, 1994 , p. 49). When referring to special education, at a conceptual level, the text indicates that this area “is based on theoretical and practical references compatible with the specific needs of its students” ( BRASIL, 1994 , p. 17). Therefore, there was prevalence of the ideas of processuality, partnership with the private sector and propositions that were based on the limitations of students with disabilities.

The analysis of the educational indexes shows us that the changes occurred in the period were discrete. According to Inep’s data, the increase in enrollment of students with special educational needs varied from 337,004 in 1998 to 404,747 in 2001. This contingent would continue to be distributed between two parallel education systems – ordinary education and exclusively specialized education – despite the changes in enrollment distribution. The document analyzed shows the relation between the enrollment in the ordinary education and those of the special classrooms and special schools by comparing percentages relative to 1998 and 2001. In 1998, there were 87% of enrollments in exclusively specialized education, and 13% in ordinary education. In 2001, these percentages were 80% and 20%, respectively. Therefore, changes can be identified, but we could hardly say that special education was no longer a parallel education system, since exclusive services – special schools and special classrooms – brought together the vast majority of students with disabilities.

When considering enrollment rates and their distribution in educational services, we can take into account a broad period, based on the analysis by Rebelo and Kassar (2018) , which uses the period from 1974 to 2014 to analyze this phenomenon, identifying that the number of enrollments has increased significantly throughout this time frame. Referring to the enrollment of students with disabilities, they state:

Overall, it is interesting to note that, in 40 years, enrollments of Special Education students increased nine times, while enrollments of the general population in Basic Education increased only 2.67 times. On the other hand, the proportion of the first in relation to the total enrollments in basic education did not reach 2% of the registrations. ( REBELO; KASSAR, 2018 , p. 288).

Moreover, these authors point out that there has been greater concentration of these enrollments in ordinary education in the last decade. They also affirm that the country has a “remarkable data set” ( REBELO; KASSAR, 2018 , p. 281), emphasizing that, although there may be methodological issues in their production, such accessible data emerge as an element of public policy evaluation.

Inclusive perspective and special education between 2008 and 2018

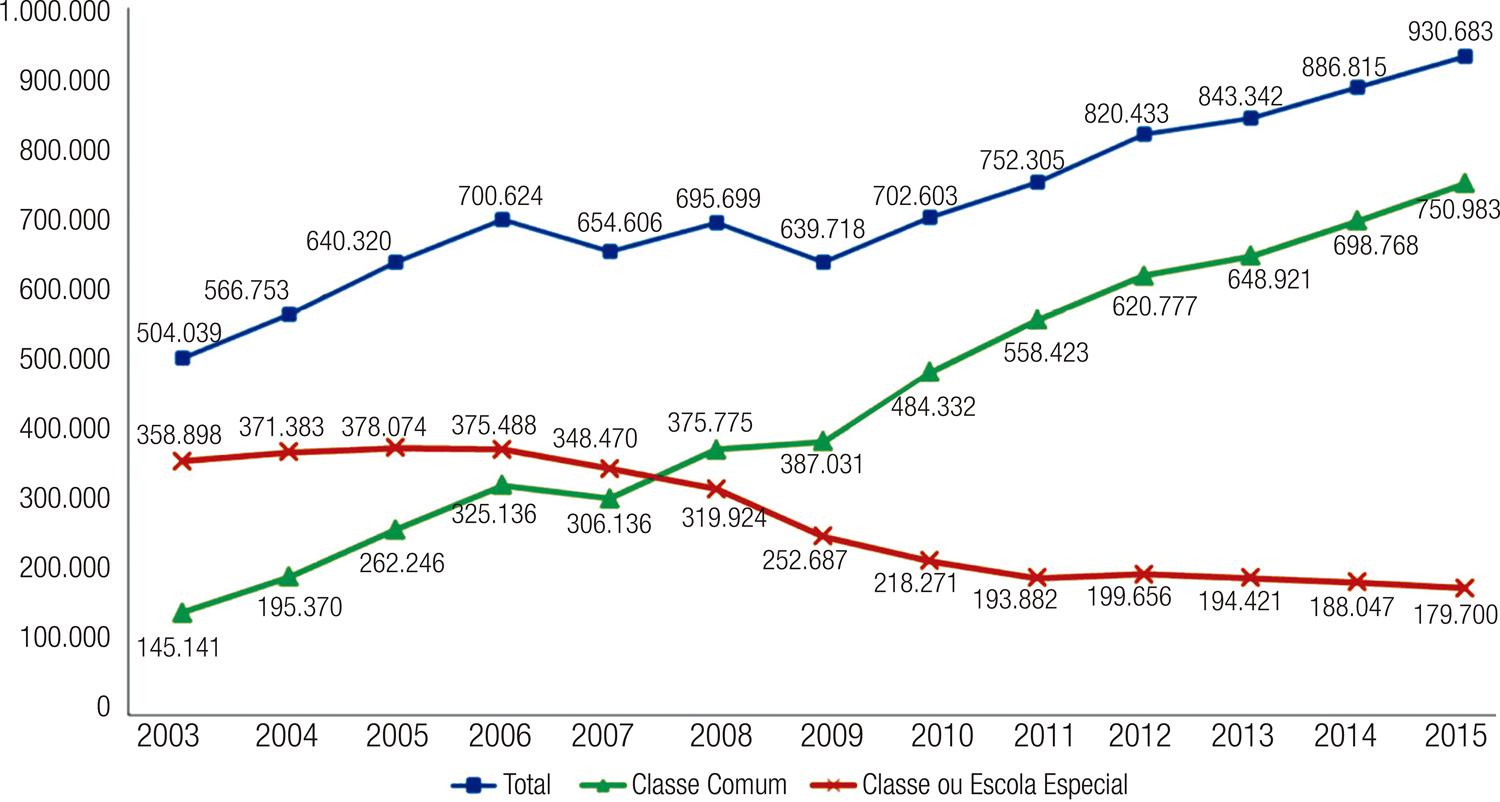

The first decade of the new millennium is undoubtedly a moment of intensification of the guidelines that link the expansion of schooling of students with disabilities and the valuation of ordinary education in Brazil. We can identify that such guidelines gained organicity with the approval of the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008 ( BRASIL, 2008 ). In the foreground, this intensification had noticeable effects on enrollment rates of students with disabilities, which progressively became more present in the ordinary education classrooms. According to the Inep School Census, these students were 145,141 in 2003, and totaled 750,983 in 2015. In procedural mode, enrollment in special education classrooms and schools decreased from 358,898 (2003) to 179,700 (2015). As we can see in the graph below, the reversal of enrollment flow trend occurred between 2007 and 2008, the moment of debate and approval of the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008.

Source: School Census data ( BRASIL, 2016 ).

Graph 1 – Enrollment of special education target audience in Basic Education

Rebelo and Kassar (2018 , p. 291) state that “enrollment of Special Education students increased in all regions from 2007 to 2014.” These rates continued showing enrollment increase in subsequent years. According to the 2017 INEP School Census ( BRASIL, 2017 ), considering primary education, there was predominance of schooling in municipal schools (almost 50% of total enrollment), and the percentage of students enrolled in ordinary education was 90%. Thus, we can identify effects of an educational policy that maintained the focus on the universalization of education in the country, which should be recognized as a promising aspect. However, it is important to analyze the conditions of schooling, including dimensions such as participation, support and school performance.

The significant changes in the educational indexes regarding the schooling of people with disabilities must be analyzed from a management change, initiated with the first government of President Lula da Silva, in 2003. The goal of school inclusion became part of an action plan that tended to seek effectiveness for social rights, involving different groups with history of disadvantage, as occurs with people with disabilities.

It is at a historical moment with these characteristics that the debate that instituted the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008 emerges, as a set of guidelines that would later demand operational dynamics instituted through ministerial programs and normative instruments. For the discussion and the elaboration of this document of guidelines, a working group4 was constituted composed of members of the then MEC Special Education Secretariat – SEESP –, and consultants invited in function of academic experience in the work as researchers and trainers in the area of special education. These consultants were members of Graduate Programs in Education at public universities in different regions of the country. The actions related to the discussion work were developed throughout 2007, in Working Group meetings and open activities, such as expanded meetings with researchers and representatives of institutions dealing with the rights of people with disabilities, including specialized institutions. Throughout 2007, there were many public hearings in various Brazilian capitals to discuss these guidelines, including based on a prospectus released in September of that year. Seminars involving public school managers and teachers within the Inclusive Education Program: Right to Diversity5 represented one the main spaces for discussion of the guidelines, with emphasis on seminars organized by macroregions, as in Natal-RN and Florianópolis-SC, both in August 2007. The final text was published in January 2008, with the presentation of the then Minister of Education – Fernando Haddad – in the Inclusão Magazine. The text of the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008 indicates as objective:

[...] to ensure school inclusion for students with disabilities, global developmental disorders and great skills/giftedness, guiding education systems to ensure: access to ordinary education , with participation, learning and continuity at the highest levels of education; transversality of the special education modality from early childhood education to higher education; provision of specialized educational assistance; teacher training for specialized educational care and other education professionals [...] and intersectoral articulation in the implementation of public policies. ( BRASIL, 2008 , emphasis added).

Ordinary education as a guideline is added to the affirmation of the transversality of special education, already highlighted in the 1996 LDB. And, the most importantly, from my point of view: no mention is made of exception conditions in the inclusion process – this is a novelty in terms of guidelines. With regard to students, after a long debate about the advantages and risks of a broad concept as special educational or educative needs, which marked the Brazilian special education in the early 2000s, the policy defines a more specific group of subjects, rescuing the triad already emphasized by the 1994 National Policy on Special Education: people with disabilities, global developmental disabilities, and great skills.6

The teacher training theme has been one of the most uncertain, in the sense of defining the spaces and configurations indicated for the training of teachers qualified or specialized in special education. Regarding this theme, the text of the policy remains broad and indicates need, in the initial and continuing formation, of:

[...] general knowledge for teaching and specific knowledge of the area. This training enables their performance in specialized educational services and should deepen the interactive and interdisciplinary character of the performance in the common classrooms of ordinary education, in resource rooms, in specialized educational services centers, in the accessibility centers of higher education institutions [...]. ( BRASIL, 2008 ).

It is worth emphasizing that, by mentioning the spaces of operation, the specialized centers are cited, which had already been named as centers of complementary care, and at no time are reaffirmed as relating to exclusive care that could replace schooling in ordinary education.

It is evident that there were changes in the guidelines for special education, but it was essential the occurrence of initiatives in line with these goals and that contemplated investments in the construction of devices that stimulated more pragmatic effects. These initiatives involved two priority dimensions: the normative plan, and the management of education systems. With regard to the first, there was the approval of provisions that now indicate the obligation to offer specialized support, such as CNE Resolution No. 04/2009 (BRASIL, 2009a), which ensured the right of access to the ordinary school for students with disabilities, such as Decree No. 6949/2009 (BRASIL, 2009b), which has constitutional amendment effects.

In order to change systems management, a network of ministerial programs has been intensified as an articulated set involving continuing teacher education, social assistance, accessibility, access to higher education, and the implementation of support services. These programs are highlighted by Kassar (2011) and Bueno (2016) , when analyzing the special education policy management plan. Among these ministerial programs, I highlight two that became structurally important in management, as they involved training and awareness – Inclusive Education Program: Right to Diversity –, and the implementation of support that had a priority dimension – Multifunctional Resource Rooms Implementation Program.

The Multifunctional Resource Room Implementation Program was proposed under the Education Development Plan (PDE) in 2007 to support education systems in the organization and provision of Specialized Educational Care (ESA). Between 2005 and 2012, 37,801 multifunctional resource rooms were made available in Brazil, covering 90% of the municipalities of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District ( BRASIL, 2015 ). This program introduces a pact dynamic between the federal government, which provides the material resources for the constitution of the resource room, and the local managers who should offer physical space and hire specialized teachers to carry out the pedagogical work. Resource rooms were valued as a space and as a pedagogical instrument, as this service is now associated with specialized care work that should no longer replace schooling in ordinary education, but support it in a complementary or supplementary way ( JESUS, 2013 ). This initiative generated an important movement to improve a service that already existed in some municipalities, such as São Paulo and Porto Alegre ( BAPTISTA, 2011 ), but that started to be now identified as support priority. The guidelines were that the attendance in the resource room should occur in a period different from that of access to the ordinary classroom, which showed an effort to prevent these services from becoming the only school space attended by students with disabilities.

The Inclusive Education Program: Right to Diversity started in 2003. Its goal was to disseminate the policy of building inclusive education systems. This program was organized to institute a dynamic of multiplication of the formation paths, involving the action of polo-municipalities, stimulating a broad process of formation of managers and educators in order to intensify schooling, offer specialized educational attendance, and guarantee accessibility.

The institutionalization of the program had MEC/SEESP technical-financial support for the municipal education systems, so that each polo-municipality was responsible for a group of other municipalities in its area, seeking to reach all the municipalities of the country by training trainers and multipliers in regional seminars lasting 40 hours. The program had different stages, but in 2011 it had 166 polo-municipalities, providing continuing education courses for managers and educators in the municipalities attended. Between 2004 and 2015, this program trained 183,815 teachers and managers ( BRASIL, 2016 ) and was the focus of different studies, as occurred with Brizolla (2007) , in an analysis that involved all the polo-municipalities of Rio Grande do Sul throughout 2006 and 2007.

I consider that two elements deserve to be highlighted: the sense of a strategic action that reaches all the municipalities of the country through the direct involvement of a part of the public administration represented by federated entities – which were not, until then, frequently triggered by the federal government; and the effects of building a new set of widespread assumptions about what public investment should be. These are complex and nonconsensual dimensions. Soares (2010) , when analyzing this program in Bahia’s municipalities, criticizes the effectiveness of this multiplier action, which is not confirmed by the ideas of Santos (2013) , in the sense that, in the same state of the federation, the effects of the program in terms of change by studying management and service dynamics are reaffirmed. Although we do not yet have the elements to evaluate these effects more consistently, it seems clear that the spread of the inclusive perspective favored the full knowledge of the 2008 National Policy guidelines and indicated the actions that would be supported by central management. In this sense, the changes start involving areas such as hiring of professionals – specialized teachers, interpreters, school support professionals – and the transformation of services that help us understand the enrollment changes already highlighted. There was a large reduction in students enrolled in special education classrooms; public schools of specialized education were transformed into support centers ( VIEGAS, 2014 ).

Research that analyzes the changes associated with this program, focusing on different regions of the country, has highlighted the criterion of access to school and the predominance of enrollment of students with disabilities in ordinary education ( CASTRO, 2015 ). They highlight the singularities and challenges present in different plans of the specific action developed by local managers, with emphasis on the tendency of enrollment concentration in the early years of schooling and the insufficient supply of specialized educational assistance, despite the large numerical increase of resource rooms. Phenomena such as professional turnover due to different forms of hiring by education systems are also evoked ( REBELO; KASSAR, 2018 ). A warning about the proliferation of professional profiles of specialized support is also the target of the reflections of Prieto, Pagnez and Gonzalez (2014) when analyzing the context of the municipality of São Paulo.

An important dimension is related to the priority social actors or partners in implementing public policy actions: instead of private-philanthropic institutions, as occurred until the 1990s, they became public managers of other federated entities, especially the municipalities. In fact, private-philanthropic institutions start being associated with a new institutional role – the provision of complementary specialized educational assistance, as established by Decree No. 7,611 of 2011 ( BRASIL, 2011 ).

We can identify that, between 2007 and 2009, there was an intensification of inclusion as a goal, with the support of existing ministerial programs and the debate on the guidelines that would govern the Brazilian policy on the education of people with disabilities. This is a very different perspective from the so-called 1900s instructional integration. This historic moment is also that of the approval of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – UN / 2006 –, which becomes part of the Brazilian legal system, with constitutional status, defining that “the right of the person with disabilities to education is only effective in an inclusive educational system, at all levels, stages and modalities” ( BRASIL, 2016 , p. 53).

Final considerations

Throughout this text, an analysis was presented about the schooling of people with disabilities in Brazil, considering the period 2008-2018 as a priority. This temporal emphasis was motivated by the initial identification of a public policy that assumed school inclusion as an educational guideline. The triggering questions highlighted the importance of seeking to understand to what extent this process effectively instituted new perspectives and new dynamics to ensure the schooling of these students.

It was possible to identify a progressive movement of Brazilian special education towards schooling as a right, integrating a public policy that is shown in a recent mode, and after the 1970s – an oscillating process marked by ruptures and continuities. Although the initial focus was on the scenario of the last ten years, there was option of a historic rescue to operate by contrasting the goals, social actors and words that marked Brazilian special education as a public policy initiative in different decades.

The most evident changes occur from the 2000s, particularly after 2003, with the affirmation of school inclusion as a guideline that integrated a policy for the Brazilian State to minimize the mechanisms of school selectivity and precariousness of schooling directed to people with disabilities. These guidelines, present in several ministerial programs of the period, gained organicity through the National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008, as this text reaffirms inclusion as an axis for Brazilian education and indicates a targeted audience more restricted in relation to special needs, to reaffirm that the ordinary school becomes the locus of schooling for all students. In addition, it presents specialized educational assistance as a pedagogical action related to special education, indicating that it should not replace ordinary education. The text of these guidelines does not refer to spaces for exclusive educational services, such as special schools, and these spaces are no longer foreseen as a goal. This is not little. The ambivalences associated with teacher education, the configuration of complementary specialized educational services and the role of private-care institutions are part of that historical moment that is expressed in a possible text, with effects that continue to be present in the contemporary debate.

In the normative plan, there was a wide production of instruments that, in line with the ministerial programs, indicate what should be the organizing lines of the managers’ action. One of the major challenges concerns specialized educational care and its relation with the resource room, in the sense of recognizing that our normative plan does not impose this service as a single model of action, but opens possibilities for such care to be an action articulated with the teaching work in general. Academic production on this theme has highlighted the need for qualification of the support associated with the work of specialized educators, the guarantee of learning processes based on adaptations that do not impoverish the curriculum, and the attention to the role of non-school institutions that are often confused with schools.

As I tried to present in the analysis of documents and academic productions, the obligation of schooling in common education was affirmed through normative instruments, such as Decree No. 6949/2009 (BRASIL, 2009b), with a wide change in the configuration of services expressed in the resource room as a priority. Changes in legislation have been substantial, but there have been insistent divergent interpretations that integrate the complexity of the political process. Paying attention to the effects and risks of these interpretations is a way to continue the fight for the right to education.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Míriam Elena Cesar. Jovens e adultos em escola especial para pessoas com deficiência intelectual: escolarização em debate. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Sorocaba, 2017. [ Links ]

BAPTISTA, Claudio Roberto. Ação pedagógica e educação especial: a sala de recursos como prioridade na oferta de serviços especializados. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial , Marília, v. 17, n. esp. p. 59-76, 2011. [ Links ]

BRASIL. A consolidação da inclusão escolar no Brasil: 2003 a 2016. Brasília, DF: DPEE/SECADI/MEC, 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 6.949, de 25 de agosto de 2009. Promulga a Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência e seu Protocolo Facultativo, assinados em Nova York, em 30 de março de 2007. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF, n. 163, ago. 2009b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto no 7.611, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: [s. n.], 2011. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Notas estatísticas do Censo Escolar 2017. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Orientações para implementação da política de educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva . Brasília, DF: DPEE/SECADI/MEC, 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Política nacional de educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva. Revista Inclusão , Brasília, DF, v. 4, n. 1, p. 7-17, jan./jun. 2008. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução CNE/CEB nº 4, de 2 de outubro de 2009, que institui Diretrizes Operacionais para o Atendimento Educacional Especializado na Educação Básica, modalidade Educação Especial. Brasília, DF: Conselho Nacional de Educação. Câmara de Educação, 2009a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Política e resultados educação especial (1995 – 2002). Brasília, DF: MEC, 2002. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Política nacional de educação especial. Brasília, DF: MEC, 1994. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Programa Educação Inclusiva: direito à diversidade. Documento Orientador. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2005. [ Links ]

BRIZOLLA, Francéli. Políticas públicas de inclusão escolar: negociação sem fim. 2007. 221 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2007. [ Links ]

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. Educação especial brasileira: integração/segregação do aluno diferente. São Paulo: EDUC, 1993. [ Links ]

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. O Atendimento Educacional Especializado (AEE) como programa nuclear das políticas de educação especial para a inclusão escolar. Tópicos Educacionais , Recife, v. 22, n. 1, p. 68-86, jan./jun. 2016. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Rosita Edler. A política de educação especial no Brasil. Em Aberto, Brasília, DF, n. 60, p. 93-102, out./dez. 1993. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Vanessa Bueno. Inclusão escolar no período de 2009 a 2013 sob a perspectiva das matrículas no censo escolar no Brasil . 2015. 184 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Escolar) – Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho (Unesp), Araraquara, 2015. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Júlio; NUNES, Leila. Deficiência mental: o que as pesquisas brasileiras têm revelado. Em Aberto, Brasília, DF, n. 60, p. 37-60, out./dez. 1993. [ Links ]

JANNUZZI, Gilberta de Martino; CAIADO, Kátia Regina Moreno. APAE: 1954-2011. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2013. [ Links ]

JESUS, Denise Meyrelles. Atendimento educacional especializado e seus sentidos: pela narrativa das professoras. In: JESUS, Denise M.; BAPTISTA, Claudio R.; CAIADO, Katia (Org.). Prática pedagógica na educação especial: multiplicidade do atendimento educacional especializado. v. 1000. 1. ed. Araraquara: Junqueira & Marin, 2013. p. 127-150. [ Links ]

KASSAR, Monica Magalhães. Educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva: desafios da implantação de uma política nacional. Educar em Revista , Curitiba, v. 41, p. 61-79, 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/n41/05.pdf>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MAIOR, Izabel Maria Madeira. A Política de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência como Questão de Direitos Humanos. Revista Científica de Direitos Humanos , Brasília, DF, v. 1, n. 1, p. 105-131, 2018. Disponível em: <https://revistadh.mdh.gov.br/index.php/RCDH/article/view/21?fbclid=IwAR3OyAMxXiLdDQlu-iRiazQXpuRWPAX6joCPJdd4NQDXv8GjjMcq5XQCsZc>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MELETTI, Silvia. APAE educadora e a organização do trabalho pedagógico em instituições especiais. In: REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO E PESQUISA EM EDUCAÇÃO (ANPED), 31., 2008, Caxambu. Anais... Caxambu: Anped, 2008. Disponível em: <http://31reuniao.anped.org.br/1trabalho/trabalho15.htm>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MULLER, Pierre; SUREL, Ives. Análise das políticas públicas. Pelotas, Educat, 2002. [ Links ]

PINTO, Céli Jardim. Elementos para uma análise de discurso político. Barbarói , Santa Cruz do Sul, n. 24, p. 78-108, 2006. [ Links ]

PRIETO, Rosângela Gavioli; PAGNEZ, Karina Soledade; GONZALEZ, Roseli Kubo. Educação especial e inclusão escolar: tramas de uma política em implantação. Educação & Realidade , Porto Alegre, v. 39, n. 3, p. 725-743, jul./set. 2014. Disponível em: <https://seer.ufrgs.br/educacaoerealidade/article/view/45570>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

REBELO, Andressa Santos; KASSAR, Mônica Magalhães. Indicadores educacionais de matriculas de alunos com deficiência no Brasil (1974-2014). Estudos em Avaliação Educacional , São Paulo, v. 29, n. 70, p. 276-307, jan./abr. 2018. Disponível em: <http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/ojs/index.php/eae/article/view/3989/3576>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Kátia Silva. A política de educação especial, a perspectiva inclusiva e a centralidade das salas de recursos multifuncionais: a tessitura na rede municipal de educação de Vitória da Conquista. 2012. 203 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2013. [ Links ]

SCHNEIDER, Doroth. Alunos excepcionais: um estudo de caso de desvio. In: VELHO, Gilberto (Org.). Desvio e divergência . 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1977. [ Links ]

SILVA, João Henrique; ALMEIDA, Míriam Elena Cesar; CAIADO, Kátia Regina Moreno. Produção do conhecimento sobre as instituições sobre as instituições especializadas para a pessoa com deficiência intelectual (1996-2015). Revista Perspectiva , Florianópolis, v. 35, n. 3, p. 859-886, jul./set. 2017. [ Links ]

SILVA Junior, Edson Mendes da. Alunos de escolas especiais: trajetórias na rede municipal de ensino de Porto Alegre. 2013. 150 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Faculdade de Educação, Porto Alegre, 2013. [ Links ]

SOARES, Márcia Neri. Programa educação inclusiva direito à diversidade: estudo de caso sobre estratégia de multiplicação de políticas públicas. 2010. 137 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, 2010. [ Links ]

VIEGAS, Luciane Torezan. A reconfiguração da educação especial e os espaços de atendimento educacional especializado: análise da constituição de um centro de atendimento em Cachoeirinha/RS. 2014. 335 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Faculdade de Educação, Porto Alegre, 2014. [ Links ]

2- Throughout the text, I will predominantly use the concept people with disabilities to refer to a group that has been given different designations in the specialized literature. The National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education of 2008 ( BRASIL, 2008 ) refers to students who are targeted by special education as those with disabilities, global developmental disabilities, and great skills/giftedness. The concept of people with disabilities is reaffirmed in the 2006 UN International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and refers to the largest number of students also designated as special education target audiences.

3- The Special Education Secretariat was extinguished in 2011, and thereafter its actions and duties became the responsibility of the Secretariat for Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion (Secadi), through the Directorate for Special Education Policies.

4- The working group was established by Ordinance 555/2007 and extended by Ordinance 948/2007. The group was constituted as follows: Secretary of Special Education; Director of Special Education Policies; General Coordinator of Articulation of the Policy of Inclusion in Education Systems; General Coordinator of the Pedagogical Policy of Special Education, in addition to teachers from higher education institutions (UFMS, UFRGS, UNB, Unesp, UFSCar, Unicamp, UFC, UFSC and UFSM).

Received: December 16, 2018; Revised: April 09, 2019; Accepted: May 21, 2019

texto en

texto en