Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 12-Abr-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945186330

SECTION: ARTICLES

2 - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil . Contact: soniacarbonell@terra.com.br.

This article is the result of my researches on the cultural heritage of traditional ceramics and the artisan pedagogy. The main problem faced was the educational praxis of the ceramics craft in a traditional community and the ways of teaching and learning handicraft work in artisanal communities. The study comprised a phenomenological investigation of the daily life of this society, and its aims were to reveal and understand how the knowledge of pottery is shared by successive generations; which are the methodologies that contribute to perpetuating the ancient secrets of the craft; how manual forms of artistic creation coexist with contemporary technologies. The ethnographic basis of the research was the traditional community of Maragogipinho, a small district in the city of Aratuípe, in Bahia, a genuine environment of ceramics handicraft, where, since the 17th century, men and women are daily engaged in the production of clay objects. The data were collected from direct observation, field diary entries, recorded interviews and photographic records between 2012 and 2015. The results obtained evidenced the immensely immaterial collection of individual and collective knowledge that coexist in this village of masters and guardians of the ceramics craft. The pedagogy of master craftsmen, or artisanal pedagogy, based on ancestral values, is effective in practice, transcending it towards the spheres of ethics and aesthetics, in the sense of fostering in the subjects the sense of belonging to a recognized social body, by means of an artistic craft that constantly converses with the tradition and the emergence of modernity.

Key words: Ceramics; Artisanal Education; Artisan Pedagogy; Mastery; Popular Cultures

Este artigo é fruto de uma pesquisa sobre o patrimônio cultural da cerâmica tradicional e a pedagogia artesã. O principal problema que se buscou enfrentar diz respeito à práxis educativa do ofício cerâmico em uma comunidade tradicional e os modos de ensino e aprendizagem em territórios de trabalho artesanal. O estudo compreendeu uma investigação fenomenológica do dia a dia dessa sociedade, teve por objetivos descortinar e compreender como os conhecimentos da cerâmica são partilhados pelas gerações, as metodologias que contribuem para perpetuar os antigos segredos de ofício, de que modo formas manuais de criação artística convivem com tecnologias contemporâneas. A base etnográfica da pesquisa localiza-se na comunidade tradicional de Maragogipinho, pequeno distrito da cidade de Aratuípe, na Bahia, ambiente genuíno da cerâmica, onde, desde o século XVII, homens e mulheres dedicam-se cotidianamente à produção de objetos de barro. Os dados foram coletados a partir de observação direta, diário de campo, entrevistas gravadas e registros fotográficos entre 2012 e 2015. Os resultados obtidos evidenciam o incomensurável acervo imaterial de conhecimentos individuais e coletivos que coexistem nessa aldeia de mestres, de guardiões da cerâmica. A pedagogia dos mestres-artesãos, ou pedagogia artesã, fundada em valores ancestrais, se efetiva na prática, transcendendo-a para as esferas da ética e da estética, no sentido de alimentar nos sujeitos o senso de pertencimento a um corpo social reconhecido, por meio de um ofício artístico que dialoga constantemente com a tradição e a emergência da modernidade.

Palavras-Chave: Cerâmica; Educação Artesanal; Pedagogia Artesã; Mestria; Culturas Populares

Introduction

The artist that cuts the wood, hammers the metal, molds the clay, carves the stone block, he brings to us the past of man, an ancient man, without whom we would not be here. Is it not admirable to see him standing, among us, in the midst of a mechanical age, this obstinate survivor of the age of the hands? Centuries have passed by him without altering his deep life, without making him renounce his ancient ways of discovering the world and inventing it.

Henri Focillon. (2012 , p. 19).

In the vast Latin American territory, since the conquest until the present day, a great diversity of cultures spread out, giving rise to a multifaceted symbolic reality, rich in artistic expressions, transmitted especially by oral tradition. Of these manifestations, we highlight handicraft as an activity that carries values that mark and distinguish identity traits in traditional societies, in which it plays an important role in ensuring cohesion in the social fabric.

The handicraft commonly practiced in the small villages ensures and consecrates the sharing of knowledge between the generations; the manual activity strengthens the social relations, engendering principles of solidarity. From the mainstay of the family and from neighborhood cooperation to the sense of belonging to the community as a whole, craft practices are woven into the constitution of life itself.

However, the urban-industrial model of contemporary society, centered on the consumption of goods and services, predatory of natural resources, avid for technological progress, endangers the ways of life that remain dependent exclusively on the work made with one’s own hands. Sometimes valued, sometimes despised, handicraft occupies an unstable position between tourism, consumption of the underprivileged classes and the tastes of the elite.

Artisans 3 are simple people who, without having any active part in economic policy decisions, end up being swallowed by the economic disarrays that separate them from their own roots and from the socio-cultural meanings of their work. In order to survive and serve the market, many of them abandon their ancestral practices, cease to create to produce instead empty, extrinsic objects, without personality, as was so well expressed by the Brazilian craftsman Zé do Carmo:

Today there is this craze to make everything equal. Back then, people said, ‘choose the best that you have and bring it.’ Now, you stop being an author to be a machine. (LIMA, B; LIMA, V, 2008, p. 173).

The impoverished, the artisans work tirelessly to obtain an exiguous income, which barely ensures the sustenance of their families. For those who depend on handicrafts today, in Brazil and in globalized Latin America, the ways of survival rest in a hazy, uncertain horizon; artisanal production still penetrates timidly into the niches of the global market, competing with industrial products.

Among the handicraft modalities, pottery is an immemorial trade, always present in the daily activities of societies. Entire civilizations in all parts of the world have produced and are still producing ceramic artifacts for the most varied functions, from the simple to the complex ones: the construction of walls, floor and roof of the dwellings; containment and storage of water; food cooking; offerings to the god; burial of the dead. In addition to functionality, ceramic handicraft gives humanity nourishment from the most elemental dreams of earth, water, fire and air. To shape forms in the clay revive and satisfy the inexorable earthly desire of original creation ( BACHELARD, 2003 ).

This article reflects on the collection of artistic knowledge related to ceramics of a traditional Brazilian community and how this knowledge is perpetuated through informal teaching and learning processes. It highlights and appreciates the production of knowledge through non-conventional pedagogical practices, in order to recognize its relevance and value and ensure its continuity. It also intends to bring elements to contribute to the debate on the safeguarding of immaterial cultural heritage, especially concerning handcraft education and, more specifically, the pedagogical processes relating to traditional pottery.

The PhD study ( ALVARES, 2015 ) that underlies this discussion presented a qualitative research, guided by the assumptions of Phenomenology ( BACHELARD, 2001 ; MERLEAU-PONTY, 1999 ) and Ethnography ( GEERTZ, 1989 ), based on a field study and a bibliographic investigation in the areas of Art ( ANDRADE, 1938 ; PAZ, 1991 ; YANAGI, 1972 ), Social Sciences ( CANCLINI, 2003 ; LIMA, 2010 ; TUROK, 1988 ) and Education ( DEWEY, 1976 ; FERREIRA-SANTOS; ALMEIDA, 2011 ; FREIRE, 2001 ; GUSDORF, 2003 ; RUGIU, 1998 ).

Although the research focused on only one social group, Maragogipinho can be considered as an emblematic case of a traditional community that constitutes itself through the work with ceramics. The village has about three thousand inhabitants and 150 potteries, that is, about one pottery for every 20 people. A distinctive aspect of this artisanal production is that the pieces are created by at least four hands: the ceramic activity is totally shared between men and women. Men extract the clay, knead it, make the artifacts on century-old wood-turners, moved with the feet, and burn them in wood-burning ovens; while women produce the finish, polishing and painting the pieces.

The historical records of ceramic activity in the region of Maragogipinho go back to the seventeenth century when potteries began to be installed near the sugar mills and the Jesuit schools of the Recôncavo Baiano for the provision of crockery, bricks and tiles ( PEREIRA, 1957 , p. 12). Nowadays, artisans are proud to proclaim that Maragogipinho was considered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as one of the most expressive centers of ceramic production in Latin America.

Maragogipinho, ceramics cultural heritage

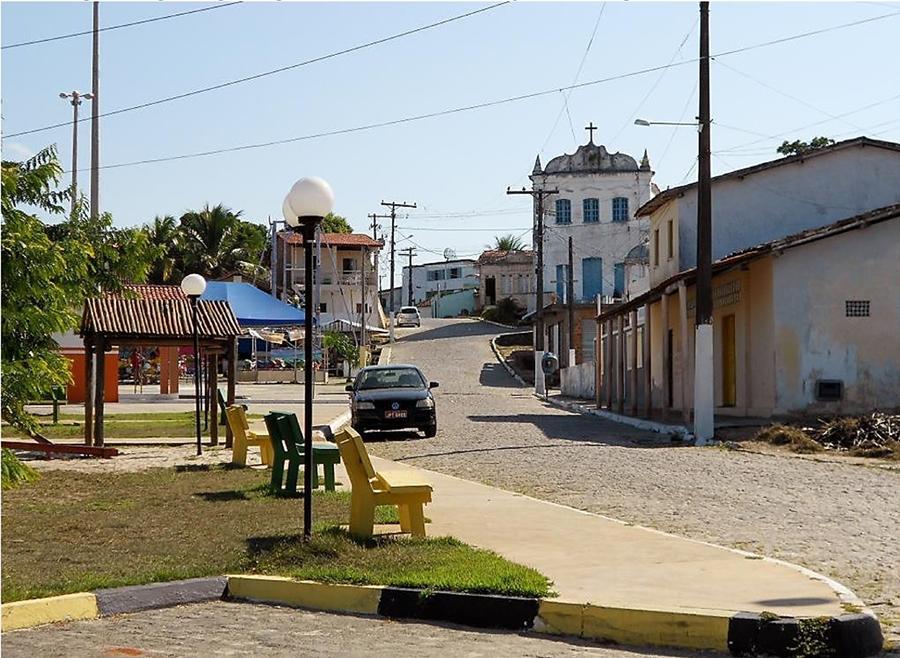

Maragogipinho is a neighborhood somewhat away from the urban center municipality of Aratuípe ( fig.2 ), in Bahia, located 130 kilometers from Salvador. It is located in the Recôncavo Baiano, a region of great cultural wealth and traditions. The Recôncavo comprises an extensive area around the Baía de Todos os Santos, including the capital Salvador and the coastal and hinterland regions around the bay. The term Recôncavo was referred to in dictionaries as idiomatic to Brazil and refers to an extensive and fertile region of Bahia. On its soil of massapê - a black clay earth -, there once flourished stately farms of sugarcane plantations, where the landlord class put down deep roots. For the sugar production, the Recôncavo received thousands of slaves, originating a high degree of African ancestry in the region.

Source: Author’s photo, 2014.

Figure 2 Outdoor sign at the entrance of the village of Maragogipinho (BA)

Maragogipinho is close to Nazaré das Farinhas, an important city of the region, with which it communicates intensely by river or land routes. The settlement began at the edge of an arm of the Jaguaripe River, the Maragogipinho River, where small winding streams run alongside mangroves and forests, still conserving a native aspect. The village preserves typical rural characteristics. Irregular streets, some already paved, converge to the main square of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Church ( fig.3 ), built at the highest point of the site in 1710, and renovated in 1930.

Source: Author’s photo, 2013.

Figure 3 View of the Nossa Senhora da Conceição Church from the main square

In the process of colonization of Brazil, the social representation and the worldview of Native Brazilians, Africans, the Portuguese and, subsequently, the mestizo, will appear significantly in the symbolic production during the following centuries. In the ceramics of Maragogipinho, the painted forms and themes refer explicitly to the hybridization 4 of the Brazilian people.

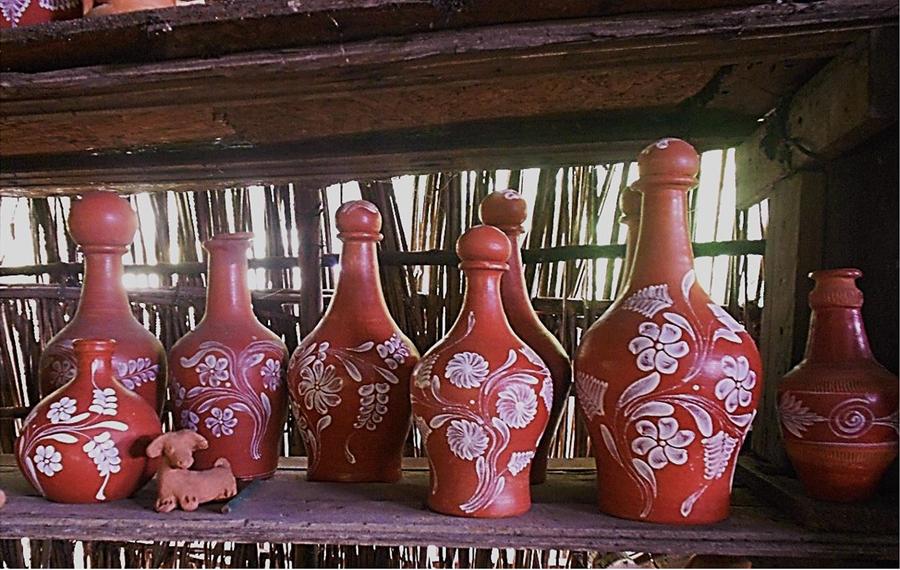

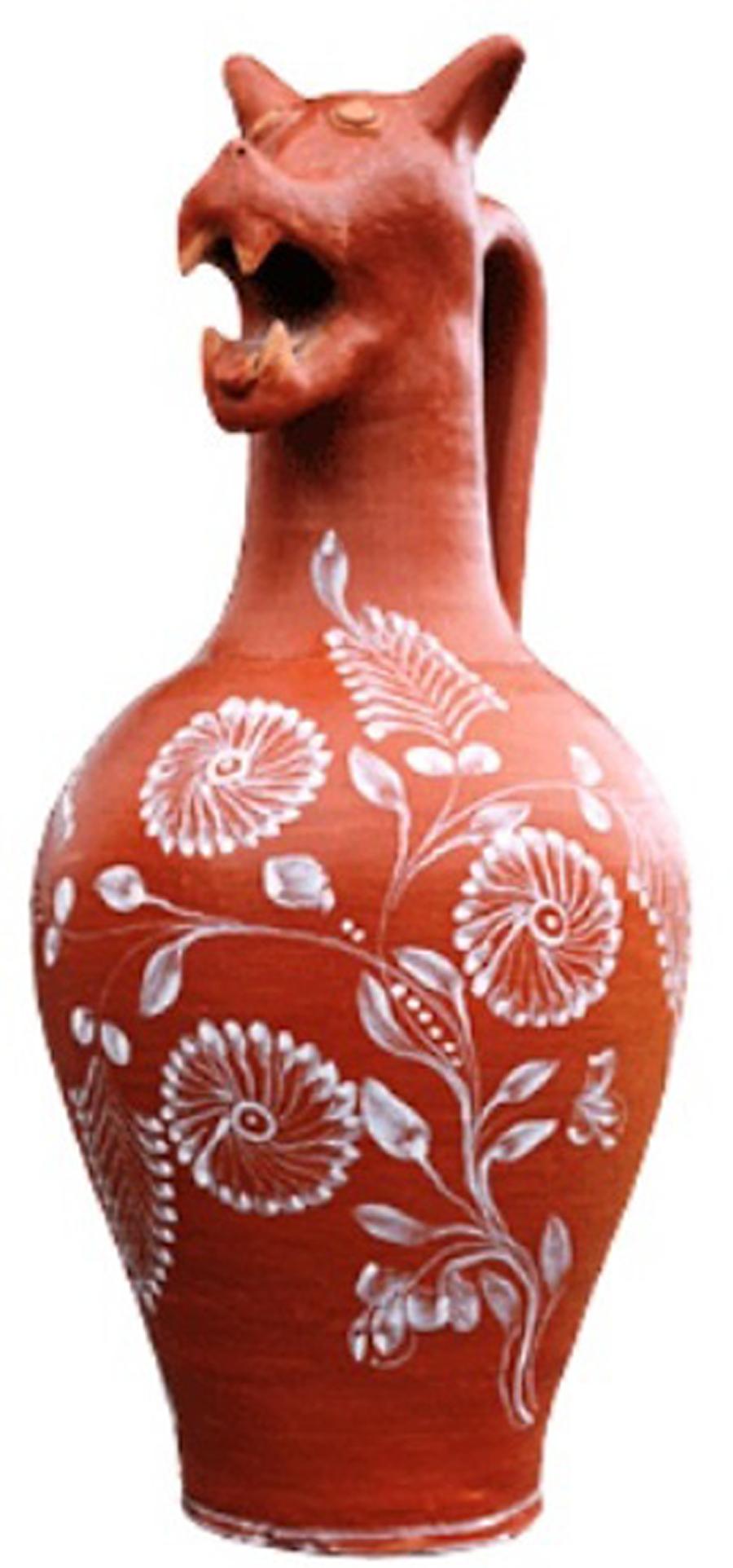

In the aesthetic care of the handicraft, in the beauty of the turned forms and in the delicacy of the paintings, the meticulousness and wisdom of the craftsmen and artisans are evident. Most of the production is of small and large utility items ( fig. 4 ), which serve for domestic, decorative and religious purposes, but anthropomorphic and zoomorphic objects are also produced ( Figure 5 ).

Photograph available at <https://br.pinterest.com/pin/484066659918092981/>.

Figure 5 Boi-bilha (Bull-jug), an emblematic piece of Maragogipinho, originally created by Mestre Vitorino, now 96 years old. The boi-bilha received an Honorable Mention from the United Nations (UN) at the Handicrafts Festival of Latin America and the Caribbean Countries in 2004

The pottery of Maragogipinho is traditionally painted with pigments made from the clay itself. Tabatinga and tauá are used as paint. The tabatinga is a white engobe 5 and the tauá is a red engobe. This meticulous technique of painting white markings in a red background, or vice versa, refers to indigenous representations, as well as floral motifs to Portuguese representations. The brushes used by the older painters are still made with the hair of a cat’s back, tied to a thin stem of palm. They are true instruments of precision, in which the trim of the hair gradually attenuates to the point, to guarantee a fine and meticulous brushstroke.

In the streets and alleys of Maragogipinho, everywhere one walks by, traces of ceramic activity can be seen. The culture of the clay is impregnated in the landscape of the village. The sight of ceramic objects everywhere, the smoke from ovens and the smell of damp clay transport the visitor to another dimension. In the squares, in front of potteries and houses, women polish and paint clay pieces, old habits that still remain in the 21st century.

The oldest potteries are located next to the river, in a wide mangrove terrain. Potteries are traditional sheds constructed with wood structure, piaçava palm straw walls and tile roofing. This ancestral architectural design facilitates air circulation and natural lighting of the space, essential aspects for the drying of the pieces and the environmental comfort of the workers, in a region of tropical heat. In the winding paths between the potteries, you can see objects drying in the sun and stacks of wood, foretelling the future fire that will lick the pieces.

The potteries ( Figure 6 ), with their peculiar architecture, represent a significant part of the ceramics cultural heritage of Maragogipinho. However, without the official recognition of the state, the assets that compose this heritage undergo constant transformations; some of them are being extinguished. In 2014, for example, I noticed that the paths had been paved and some wood and piaçava potteries gave way to masonry sheds.

The turning wheel ( fig.7 ) is the tool of excellence for the preparation of ceramics in Maragogipinho, usually located in the best place of the pottery so that the potter benefits from ventilation and natural light. As a rule, the pottery wheels are made of wood, moved by the feet. The learning of the craft is centered on the handling of this millenary instrument, which requires the use of both hands. Manual asymmetry is something to be overcome when working on the wheel.

Wood-fired ovens are also elementary instruments for the production of ceramics and are part of the cultural heritage of Maragogipinho. Basically, two types of furnaces are built: the caieira , with an opening on top (for small works or for a small number of pieces), and the capela , closed, with a vaulted top (for larger pieces and large quantities).

The transport of the pieces to Salvador and its surroundings is also another aspect that deserves attention because of the changes it underwent. For more than three centuries, the artifacts were transported on sailboats ( Figure 8 ). In these boats, the quality of the transport of the pieces is unparalleled because they are not subject to friction and thus not easily exposed to breakage. The sloop is a typical vessel, also part of Bahia’s cultural heritage, but they have been dwindling for some time. After the road that gives access to Maragogipinho was paved, the trucks practically replaced the sloops in the transportation of the pottery, which significantly increased the cost of selling the products.

Source: Photo by Ferraz (2009 , page 23).

Figure 8 Ceramic pieces being shipped on a sloop at Maragogipinho dock

The fairs where the Maragogipinho pieces are marketed also make up the intangible cultural heritage of ceramics. There are some of them in the vicinity, but the main one is the Feira dos Caxixis ( fig.10 ), in Nazaré das Farinhas, which, according to oral reports, takes place since over 200 years ago, always in the Holy Week. The Feira dos Caxixis is famous in the region; it functions as a kind of showcase for Maragogipinho. It is in it that the artisans of the community place high expectations of distributing their products.

Caxixis are the small ceramic objects that gave the fair its name. Their manufacture is originally related to the learning process of the children: the boys make caxixis in the wheel and the girls exercise their painting skills with these playful miniatures ( fig 9 ).

It is because of all this that Maragogipinho, a center of ceramics handicraft, holds an important Brazilian cultural heritage. The survival of this heritage is at serious risk. The traditional knowledge of pottery craft has been disappearing with the death of masters and teachers; those who remain working are getting older. The children and descendants of artisans have left the village in search of education and other job opportunities. There is a migration of people from outside to work with clay, but they are unaware of the secrets of the craft and the traditional techniques. The sources of raw materials, clay and wood, have been declining without a sustainable renovation plan. In the balance of time, the losses are gaining weight: the high prices for transporting the pieces by truck greatly affected the sale value; the disappearance of professions linked to the ceramics production chain, such as the kneader, the oven burner and even the painter, overload the artisans, who have to stop producing in the traditional way; the precarious conditions of economic subsistence, retirement and social security of the artisans do not stimulate the new generations to continue the craft. It is also important to note how the physical and cultural transformations of space, oriented predominantly by the hegemony of intermediaries, based on capitalistic principles, cause the decline of the artisanal production of ceramics.

We will next ascertain the need to recover and document the knowledge and pedagogical processes of the traditional pottery of Maragogipinho, in order to contribute to the preservation and safeguarding of this heritage.

Knowledge with the strength of springs

Old trees were almost all of them prepared for the exile of the cicadas. Salustiano, a Guató indian, taught me this. And taught me more: that the cicadas of the exile are the only beings that know by heart when the night is covered with abandon. I think we should give more room for this kind of knowledge. The knowledge that has the strength of springs. Manoel de Barros (1998 , p. 12).

Handmade ceramics brings together a set of non-institutional, illiterate knowledge related, on the one hand, to the processes of artistic creation and, on the other, to the cycles of nature; to the elements: air, water, fire and earth; to the states of matter. The knowledge of pottery circumscribes a cultural content and is maintained over time by oral tradition, but it is re-created in its contact with contemporary technologies and lifestyles.

In the singular universe of the craftsmen of Maragogipinho, we can understand the intrinsic aspects of the productive chain of the ceramics handicraft; of the foundations of the social division of labor between men and women; of the stages of production: extraction of clay, processing, kneading, turning and modeling of pieces, finishing, firing, and commercialization of the objects.

The singularity of each people, expressed through their artistic production, exhibits both the signs that identify it and those that distinguish it. Tião Rocha (2010) states that the making of embroidery, baskets and pots is a universal activity; but the ways of doing them, the materials with which they are made, and the forms or patterns used to make them are not universal. The distinctive features of making and teaching how to do, the tools, the constitutive properties of the materials used, the distinctions of style, are all aspects that confer identity marks to the pieces, the authors and their cultures.

The knowledge of these artisans has a concrete quality, and it originates in social practices, and in their work and daily activities. It is knowledge pertaining to the skin, to the bones and muscles, to the senses, to the mind. We emphasize here the experience of the body as a sense-creating field, because the nature of the artisan wisdom does not come from the exclusive action of the intellect, but derives from an event of corporeality.

To elucidate the concept of wisdom of the body, we turn to a passage from the novel The Cave, in which Saramago reflects on the wealth of knowledge possessed by a potter, in this case, the character Cipriano Algor:

[...] one can no longer work by eye or hand, by touching or sniffing, according to the backward technological procedures of Cipriano Algor, who has just communicated to his daughter with the most natural air in the world. The paste is good, moist and plastic like it should be, easy to work, now, we ask, how can he be so sure of what he says if he has just put his palm on it, if he has just squeezed and moved some paste between the thumb and the index and middle fingers, as if, with closed eyes, all immersed in the interrogating sense of touch, he was assessing, not a homogeneous mixture of red clay, kaolin, silica and water, but the warp and the weft of silk. More likely, [...] is that it’s his fingers that know, not him. ( SARAMAGO, 2000 , p. 148).

The corporeal knowledge of a people constitutes its intangible cultural heritage. In Latin America and Brazil, knowledge based on manual crafts still remains little valued. Artistic practices, when recognized and renowned, receive a folkloric hue of exoticism, sometimes praised for their ancestral character, which certainly reconnects traditional societies with their roots but does not legitimize them in the present. Usually, these cultures are considered as old and subaltern when confronted with the cultural modernization that is imposed as a goal for Latin American societies.

The loss of prestige of the wisdom of the body is becoming more pronounced on our globalized planet. Everyday urban life, digital technologies, education processes and work activities are all increasingly occurring without the need to come into contact with raw materials, with the mutable phenomena of nature, and with the body itself. However, this is not the case in Maragogipinho:

Our work here is all-manual. We do not have that technology, it’s all muscular work, it’s a hard work, beginning with the preparation of the raw clay. We prepare the clay first with the foot, then kneading with the hand. [...] People here don’t need a gym to stay muscular, this job depends a lot on the body, the body needs to be well fit. (potter Nelinho).

In the contemporary world, several societies still rely exclusively on the body to perform productive work and on the spoken word to share knowledge. The bodies of people who work with clay are shaped by repetitive actions, by exposure to the sun and inclement weather, by direct contact with nature. In Maragogipinho, clay matter plays a structuring role in people. It acts as an extension of one’s own body, organizes time, articulates sociability, lends weight to family life. The dance of the feet and hands in the pottery wheel, the cadence of the body and of the foot stepping on clay, the tone of the arms in the kneading and the delicacy of the gestures of the hands painting constitute extremely expressive movements, aesthetic, that impart dignity and beauty to those who execute them.

Many Maragogipinians, while still little children, learned the craft of pottery with their mother, father, uncle, grandfather, or neighbor. Some of these craftsmen and artisans have the skill and readiness to teach; they expertly spread the legacy of their ancestors while forming disciples to take their place. The invaluable immaterial cultural heritage of the community has found in the educational processes of ceramics, in the pedagogy of master craftsmen, a methodological wealth that needs to be made evident in order to guarantee the continuity and sustainability of this traditional knowledge.

Artisan pedagogy

Education is the process of sharing and mediating the accumulated social experience between the older and younger generations, in which society constantly acts on the development of the human being.

In literate societies, the school represents the main agency in the promotion of human development. Conventional school education privileges intellectual activity and the mastery of written language, with a view to recording and preserving social memory. In general, in traditional school pedagogy, which has spread throughout the world since the eighteenth century aiming to universalize access to knowledge, teaching is divided into disciplines; teachers act as central figures: they master logically organized and structured contents and transmit it to the students, predominantly in oral expository form. The conventional school conceives the intervention of the teacher as indispensable to trigger and promote the mechanisms of learning in the students.

In popular cultures of oral tradition, knowledge is conceptualized and verbalized in reference, greater or lesser, to human experience. Society has a high regard for elder men and women, who specialize in safeguarding its history and knowledge. The education of the younger is basically conducted through the spoken (or silenced) word, and learning occurs through action.

Nowadays, a new kind of orality is being supported by electronic means such as cell phones, computers, television and others that depend, in part, on writing to exist and function. However, several contemporary illiterate societies still retain striking features of oral culture, essentially related to the function of memory, which has always been extremely developed in these social groups. In addition, they perpetuate a deep relationship between man and the word:

Where there is no writing, man is bound to the word he utters. He is committed to it. He is the word, and the word bears witness to what he is. The very cohesion of society rests on the value of and the respect for the word. By contrast, at the same time that it spreads, we see that writing is gradually replacing the spoken word, becoming the only proof and the only resource; we see the signature become the only acknowledged commitment, while the sacred and deep bond that united man to the word progressively disappears to give way to conventional university degrees. (HAMPÂTÉ BÂ, 1982, p. 2).

In artisan communities, “traditional crafts are the great vectors of oral tradition” (p.11). The very repertoire of gestures of craftsmen can be considered a language, the gestures of each craft symbolically reproduce the mystery of the first creation, linked, ineluctably, to the power of the word: “The blacksmith forges the Word, the weaver weaves it, the shoemaker softens it by tanning it” (p. 12).

The process of teaching and learning the craft takes place mainly in the workshop. Even though it brings together teachers and apprentices, the craft workshop does not constitute a school, it is a workplace where there is no separation between working and learning, or working and teaching, work is mixed with artistic practice. Handicraft education is eminently constituted in practice, through the manual work, by observing and imitating the master craftsman, and by the apprentice’s acquisition of a poetic course of his own.

As old as the first craftsmen, the artisan pedagogy has its origins in the Neolithic era. Later, it developed within the medieval guild corporations and encouraged thinkers and educators to seek and recover in the origins of craftwork the foundations of the education that was being developed in these workshops, through a long exercise of observation and practice.

The ideas of John Dewey (1859-1952), the respected American philosopher, convey an epistemological understanding of the artisan pedagogy. Dewey (1976) believed that teaching should be done more by action than by instruction, real learning occurs in practice; he talked about learning by doing , stressing the importance of active personal experience in educational processes. He argued that education represents a process of renewal of experience, in which there is no end to be achieved.

The notion that education should have the life-experience as its guiding principle influenced the new school of Progressive Education, an important movement for the renewal of education that was especially strong in Europe, America and Brazil in the first half of the twentieth century. However, later, the practice of learning by doing, so dear to Dewey, has been gradually abolished and replaced by the opposite notion that true knowledge is assimilated by the intellect.

Recently, other educators have been concerned with recovering the pedagogy of master craftsmen, such as the Italian Antonio Santoni Rugiu (1921-2011), who brought to light, in his work Nostalgia of the master craftsman , the formative importance of handicraft in culture and education. Rugiu (1998) affirms that in artisanal pieces rests, dormant, the germ of the educational phenomenon. He exalts the artisan as a worker who controls his own time and has the knowledge of the whole production process of his craft. The master craftsman can recognize himself and be recognized in the objects that are created by his skillful hands.

In the artisan pedagogy, the relationship of teaching and learning established between master and apprentice surpasses the mere transmission of techniques. Besides the assimilation of concepts and procedures related to the expressive potential of materials or the manipulation of tools, the disciple learns to relate to the handicraft piece through the possession of a repertoire whose sharing of knowledge implies the awareness of its way of being in the world. To learn to do a good job and to develop a style of his own depends, especially, on the degree of rapprochement and affinity between master and apprentice.

In his study of the pedagogy of two master craftswomen in pottery, Mattar (2010) shows that the educational processes related to pottery alternate between observing the master, doing together and doing it alone:

Before beginning to do actual work, the apprentice apprehends with the eyes the procedures to be carried out to accomplish a given technical procedure, that is, he learns by observing the masters. Learning by doing alone occurs when the observation of potters occurs concurrently with the apprentice’s work, serving as a practical example for actions developed simultaneously. And in this case, not only does the apprentice observe the masters but they also observe him and make minor corrections to his pieces, if necessary. After having had experiences of producing together with the masters and having observed them work, the apprentice is put in a situation in which he has to apply the knowledge he has acquired, doing one piece alone, when he tests his knowledge and acquires new ones. ( MATTAR, 2010 , p. 154).

Another hallmark of the artisan pedagogy is repetitive action. Repetition is the driving force behind the teaching and learning of handicraft and, in this case, ceramics. To repeat infinite times the same gestures on clay does not entail, absolutely, mindless execution. On the contrary, relentless repetition provides a state of transcendence, a surrender of the body, which in its aesthetic pursuit thinks through form creation. Through repetition and, consequently, the mastery of technique, the apprentice reaches maturity and consolidates a style of his own.

It is in this way, therefore, that the artisan pedagogy, articulated in the oral transmission, aims at helping the emergence of what is singular in the person, referring to the very etymology of the word education, which originates from the Latin educare, educere: “to take out.” Artisanal education promotes the structuring of the personal and social spheres of the subject’s identity; anchored in Dewey’s learning by doing (1976), it enables a formative experience that is an end in itself, to wit, it helps the person to meet his essence and to recognize his place in the community. In this journey, the role of the master is decisive.

The mastery in artisanal communities

Artisans are the true teachers of a class education, and when they educate themselves in the practice of which they are part, they advance the culture and the awareness of which they are the guides. Carlos Rodrigues Brandão (2002 , s/p.).

In the pedagogical processes of traditional popular communities, mastery does not require diplomas or certificates. “The affirmation of the power of the master is inscribed in an ontological hierarchy, outside of any administrative sanction” ( GUSDORF, 2003 , p.103). The legitimization of the master occurs in the daily life, in the recognition of the quality of his work, in his experience, in his ethical conduct. The master is usually someone older, who has been practicing the craft for quite some time. Since his practice begins at a young age, at maturity he has amassed significant knowledge, becoming the keeper of ancestral practices. Another quality of the master is that he does his work with pleasure and care. A person can become a master without having desired or sought to be one.

Gusdorf highlights the difference between the pedagogy of the master and that of the teacher:

The pedagogy of the master thus develops into a kind of counterpoint to the teacher’s pedagogy. The teacher teaches everyone the same thing; the master announces to each one a particular truth and, if he is worthy of his work, expects from each one a particular response, a singular response and an achievement. The highest function of mastery seems to be the announcement of a revelation that goes beyond the mere exposition of knowledge. ( GUSDORF, 2003 , p. 70).

The work and teachings of the master craftsman merge; amalgamated, they mobilize values and materialize part of the intangible knowledge of his society. The master guards, recreates and spreads knowledge that crosses generations and gathers the identity marks of his people. In addition, he is endowed with an excellent skill in his craft; he is disciplined and, above all, profoundly knowledgeable about his environment.

In Quechua culture, the figure of the master is known as el amauta , a kind of philosopher-poet responsible for keeping history alive through an oral recollection of memories. The amauta himself is already the teaching, in the way he lives and in how he relates to the world and to the community. The master’s actions are guided by the pursuit of coherence ( FERREIRA-SANTOS; ALMEIDA, 2011 ).

In Maragogipinho, we find several craftsmen and craftswomen recognized and legitimized as masters by their peers. Vitorino, Padre, Nené, Almerentino, Nelinho, Rosalvo, Miro, Zé Curu, Seu Zé ( Figure 11 ), as well as Rosalina ( Figure 12 ), Dona Santa and Zelita are among the masters we interviewed. Caring, polite, they are people who emanate dignity and integrity. The curious thing is that all of these interviewees, without exception, revealed a special delicacy in personal interactions. The characteristic gentleness of the ceramist is well delineated by Bachelard when referring to the work with the clay:

Soft matter softens our anger. As fury has no object in the work of this splendid softness, the subject becomes a subject of softness. ( BACHELARD, 2001 , p. 67).

The candor found in clay masters confirms the idea that they act as amautas in this community. Most of them express a constant concern for the continuity of the pottery craft, denoting their inexorable debt to tradition, a true legacy they share with their apprentices.

During field research, we did not see children working in potteries. The few we saw were babies or small boys with their mothers who polished or painted the pieces. Nowadays, actions against child labor have been preventing the presence of children in workplaces. This was not what happened in ancient times. Some artisans told us that as children they practically lived in the potteries, even though they were not allowed to touch the materials. They had to wait patiently for the right time for initiation. They felt so keen to learn that they often practiced in hiding when the adults walked away. Gusdorf (2003) confirms that the desiring structure supports the educational process.

This is the case of the master Rosalina Motta, now 87 years old. Rosalina no longer paints because she became blind, but she is an important reference in the community. Her delicate and firm brushstroke marked her mastery of Maragogipinho’s traditional painting and brought to her many disciples.

Rosalina recalls that when she was a little girl, she was curious and nosy and had a great desire to learn to paint:

I’d take the broken pieces: moringa, stove, and I’d begin to train hidden from my mother, because she’d soon say, “Look, don’t go ruining my brush.” But I was disobedient; every time she left, I’d take the brush and I’d begin to work! ( FERRAZ; TEIXEIRA, 2011 , p. 22).

The archetypical apprentice searches where it is least expected until he finds something that allows a symbiosis with the master, so that the master becomes an apprentice even at the height of his mastery ( FERREIRA-SANTOS; ALMEIDA, 2011 ).

Another interviewee, Master Nelinho, also remembers that when he began making pottery at age ten, he enjoyed the moments when his father left the wheel. The master craftsman feeds in the disciple the curiosity and the capacity for observation:

My father never forced me to work. He just wanted me to be there, under his eyes. And I was always curious, leaning here and there I’d begin to touch things, I wanted to do things and such, and he was always watching. When he’d leave the wheel, I’d then sit at his wheel. But that my legs were short and didn’t reach the tripod, the support of the feet. So I’d stay perched there. And sometimes I’d fall on the wheel, and it’d throw me away and I’d have to come out from under it. (Nelinho).

When the boy expressed a desire to become an apprentice, the master ordered a small wooden pottery wheel for him:

He then asked, “Do you want to learn?” I said, “I want to,” I was curious. Then he had a smaller wheel made for me. I was still a little boy; I had no idea what I wanted out of life. I was nine or ten years old. Then he began to teach me. I learned to center the clay, I started everything then. (Nelinho).

The mark of the master manifests itself in a relentless demand: “If the master can demand everything from the disciples, it is because he never ceased to demand everything from himself, without ever reaching full satisfaction” ( GUSDORF, 2003 , 109). Master Nené learned pottery with his grandfather, Cláudio Manuel Nazaré, a demanding teacher. Grandfather’s method was radical:

He’d tell us to break it. He’d say, “Break it, it’s badly done!” He’d come with that calmness of his: break it, it’s badly done, it’s like that, it’s like this...” and he’d show the defect. (Nené).

And despite his dismay, Nené broke his own pieces, practicing detachment, an essential lesson in learning pottery. The loss of objects can happen at various points in the artisanal process: during modeling, drying or firing. The potter learns to live with a feeling of detachment towards his work. He begins to understand that the ceramic piece is not immortal, it is constantly exposed to the weather and the adversities of the production process.

Like in the medieval guilds, pottery disciples learn by imitating the master craftsman, whose focus is to teach them how to do a good job. The masters usually pride themselves on the quality that is apparent in their pieces.

What was always important to him [the father] was qua-li-ty. Quality for him was seeing that the pieces were perfect, with a good finish. (Nelinho).

However, simple imitation does not generate lasting satisfaction in the disciple. The investment in the maturing of skills is a slow process, and this unhurriedness of artisanal time is a source of satisfaction because it opens wide spaces for imagination and reflection. “Mature means lengthy; the subject appropriates the skill in a lasting way” (SENNET, 2009, p. 328). When learning the art of ceramics, the knowledge is apprehended without haste, perennially inhabiting the body of the apprentice.

During the artisanal educational process, it is important to be a good apprentice to become a good master.

Both [master and disciple] live, together, the same adventure. The master once was, in fact, a disciple; and the disciple, if he is worthy of the master, will be a master in turn. The education of mankind, at its best, continues in each epoch according to the renewed demand of this culture of man for man, from teachers to disciples and from disciples to teachers. That is why, in spite of the opposition that technical specializations seem to make, every authentic master is a master of humanity. ( GUSDORF, 2003 , p. 193).

Aside from learning all aspects of the craft, the apprentice of pottery develops resilience. To become rooted in his native land is an unavoidable aspect of his mission. This statement is exemplified by the history of Nelinho. Born in Maragogipinho, with four sisters, he is the only son in the family. He learned the art of the pottery wheel as a child from his father. In his youth, he made an attempt to pursue a career in another profession, and moved to the capital, Salvador, to work in an accounting office:

When I finished high school, I said, “I’m leaving.” I told my father, “I’m going to live in Salvador.” And he said, “ What are you going to do there?” I went there, started working in an accounting office. I even liked it; I was about eighteen to nineteen years old. (Nelinho).

However, his father fell ill and Nelinho had to return to Maragogipinho to fulfill the professional commitments of the old master:

He had a lot of orders to deliver here. My boss said, “Go solve your family’s problem and, if you want, you can come back; your job will be here for you.” (Nelinho).

Nelinho never went to work as an accountant again. He anchored himself to his community of origin and continued his father’s work. Nelinho is a potter today. The word potter, in Maragogipinho, has a broad meaning, not confined to professional activity. Besides being a means of earning a living, being a potter in this community means occupying a position of reference, of social leadership.

Nelinho became a potter, which may mean that he chose to be a potter. We can say that he fulfilled his destiny, in the sense of authentic historicity , according to Heidegger. For the philosopher, destiny is the authentic decision of man to return to himself, to transmit his own self and to assume the inheritance of past possibilities. To exist authentically is to exist in the mode of destiny, which designates an existence based on the choice of an inherited contingency (Heidegger, 1999 apud ABBAGNANO, 2007 , p. 286). Nelinho was educated to choose to be himself.

In Maragogipinho and other traditional communities, as the young leave, the elders remain rooted. They accept the inexorability of the dispersion of their original group, but they are fixed to the place of origin, carrying out the resistance of their culture. Achieving a sense of rootedness is one of the most vital human needs:

To put down roots is perhaps the most important and the least known need of the human soul. It is one of the most difficult to define. The human being has roots because of his actual, active and natural participation in the existence of a collectivity that preserves certain treasures of the past and certain forebodings of the future. (WEIL, 2001, apud FROCHTENGARTEN, 2009 , p. 96).

In this perspective, the artisan education is of inestimable value. The traditional master-craftsman lives, in our days, a territory of ambiguities. He is aware of the historical and social value of his craft without, however, being able to ensure the continuity of the knowledge of which he is a keeper. In the face of the dispersal of the original community, the sharing and transmission of the ceramics craft consolidate an educational process aimed at both the constitution of the person and at a greater identity issue: the sense of belonging to a social body in the process of vanishing.

Final considerations

This article presented reflections on the cultural heritage of handicraft ceramics, the pedagogy of master craftsmen and the teaching and learning processes of the pottery craft in Maragogipinho, Bahia, a traditional Brazilian popular community.

I have shown that the pedagogy of master craftsmen is based on ancestral knowledge, but it does not look only at the past and at its preservation, within a linear and univocal notion of time. As in the Quechua tradition, in which the past is ahead of the person because it shapes his worldview and the future is behind because it is unknown ( FERREIRA-SANTOS; ALMEIDA, 2011 ), the artisan pedagogy nurtures the constant dialogue between tradition and the emergence of the new. In the universe of handicrafts, in their ways of teaching and learning, layers of memory accumulate from daily activities, past and present, while opening itself to glimpses of the future.

In the XXI century, ceramics artisans inhabit an increasingly individualistic world, which has lost the sense of community ( BAUMAN, 2005 ); nevertheless, their existence is based on cooperation with its peers. The pedagogy of master craftsmen consolidates a process of ethical and aesthetic education, which promotes teaching and learning experiences based on ancestral knowledge, cooperation, brotherhood, and on values that emerge from the artistic praxis, from the constant action on matter, from the aesthetic encounter with the very creation and, consequently, with themselves. “Decency and beauty go hand in hand” was how Paulo Freire called the fusion between ethics and aesthetics in education. (Freire, 2001).

To conclude this article, we evoke Octavio Paz’s poetry to express the formative value of handicrafts:

Handicraft runs along with time, and does not want to beat it. [...] Handicraft does not want to last for millennia nor is possessed by the urge to die soon. It flows day by day, it flows with us, it wears itself little by little, it does not seek death or deny it: but accept it. Existing between the time without a time of the museum and the accelerated time of the technique, the handicraft is the palpitation of human time. It is a useful object, but it is also beautiful; an object that lasts but ends and is resigned to its own end; an object that is not unique, like the work of art, and that can be replaced by another object similar but not identical. The handicraft teaches us to die and thus teaches us to live. ( PAZ, 1991 , p. 57).

The history of education says little about handicrafts and their formative importance. However, the pedagogy of the master craftsman is a mirror of traditional cultures. The artisan pedagogy reflects the metamorphoses of these communities in their quest to update themselves and sustain their permanence. To recognize and revive the artisan pedagogy and its values of human formation, therefore, is to face up to the complexity of a historical situation that puts at risk the survival of societies, of cultures that refuse to die.

REFERENCES

ABBAGNANO , Nicola . Dicionário de filosofia . São Paulo : Martins Fontes , 2007 . [ Links ]

ALVARES , Sonia Carbonell . Maragogipinho – as vozes do barro: práxis educativa em culturas populares . 2015 . 375 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação: Cultura e Educação) . Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo , São Paulo , 2015 . [ Links ]

ANDRADE , Mário . Obras completas . São Paulo : Livraria Martins , 1938 . [ Links ]

BACHELARD , Gaston . A terra e os devaneios da vontade . São Paulo : Martins Fontes , 2001 . [ Links ]

BACHELARD , Gaston . A terra e os devaneios do repouso . São Paulo : Martins Fontes , 2003 . [ Links ]

BARROS , Manoel de . Retrato do artista quando coisa . Rio de Janeiro : Record , 1998 . [ Links ]

BAUMAN , Zygmunt . Identidade . Rio de Janeiro : Jorge Zahar , 2005 . [ Links ]

BRANDÃO , Carlos Rodrigues . A Educação como cultura . Campinas : Mercado de Letras , 2002 . [ Links ]

CANCLINI , Nestor G . Culturas híbridas . São Paulo : Edusp , 2003 . [ Links ]

DEWEY , John . Experiência e educação . São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional , 1976 . [ Links ]

FERRAZ , Iara ( Org .) . Maragogipinho e a tradição do barro . Rio de Janeiro : Iphan; Cnfcp , 2009 . [ Links ]

FERRAZ , Iara ; Teixeira , Nádia B. M. A decoração da cerâmica tradicional de Maragogipinho . Rio de Janeiro : Iphan; Cnfcp , 2011 . [ Links ]

FERREIRA-SANTOS , Marcos ; ALMEIDA , Rogério de . Antropolíticas da educação . São Paulo : Képos , 2011 . [ Links ]

FOCILLON , Henri . Elogio da mão . São Paulo : Instituto Moreira Salles , 2012 . Livro eletrônico . [ Links ]

FREIRE , Paulo . Pedagogia do oprimido . Rio de Janeiro : Paz e Terra , 2001 . [ Links ]

FROCHTENGARTEN , Fernando . Caminhando sobre fronteiras: o papel da educação na vida de adultos migrantes . São Paulo : Summus , 2009 . [ Links ]

GEERTZ , Clifford . A interpretação das culturas . Rio de Janeiro : LTC , 1989 . [ Links ]

GUSDORF , Georges . Professores para quê? São Paulo : Martins Fontes , 2003 . [ Links ]

HAMPÂTÉ BÂ , Amadou . A tradição viva: história geral da África . v. 1 . São Paulo : Ática; Unesco , 1982 . [ Links ]

LIMA , Beth ; LIMA , Valfrido . Em nome do autor: artistas artesãos do Brasil . São Paulo : Proposta , 2008 . [ Links ]

LIMA , Ricardo Gomes . Objetos: percursos e escritas culturais . São José dos Campos : Centro de Estudos da Cultura Popular; Fundação Cultural Cassiano Ricardo , 2010 . [ Links ]

MATTAR , Sumaya . Sobre arte e educação: entre a oficina artesanal e a sala de aula . Campinas : Papirus . 2010 . [ Links ]

MERLEAU-PONTY , Maurice . Fenomenologia da percepção . São Paulo : Martins Fontes , 1999 . [ Links ]

PAZ , Octávio . Ver e usar: arte e artesanato . In: PAZ , Octávio . Convergências: ensaios sobre arte e literatura . Rio de Janeiro : Rocco , 1991 . p. 45 - 57 . [ Links ]

PEREIRA , Carlos José da Costa . A cerâmica popular da Bahia . Salvador : Progresso , 1957 . [ Links ]

ROCHA , Sebastião . Artesão: sujeito e objeto de seu trabalho . [ S. l. : s. n. ], 2010 . Disponível em: < http://www.scribd.com/word/full/2974453?access_key=key-an47z40hvbij1sqfhq8> . Acesso em: 18 jul. 2010 . [ Links ]

RUGIU , Antonio Santoni . Nostalgia do mestre artesão . Campinas : Autores Associados , 1998 . [ Links ]

SARAMAGO , José . A caverna . São Paulo : Companhia das Letras , 2000 . [ Links ]

SENNET , Richard . O artífice . Rio de Janeiro : Record , 2009 . [ Links ]

TUROK , Marta . Como acercarse a la artesanía . México : Plaza y Valdés , 1988 . [ Links ]

YANAGI , Sõetsu . The unknown craftsman: a Japanese insight into beauty . Tranlation by Bernard Leach . Tokyo : Kodansha International , 1972 . [ Links ]

3- In several sections of the text, I use the expression craftsman to also refer to the female artisan, master and teacher.

4- The concept was broadly developed by Canclini (2003 , p. XXVII) to encompass intercultural relationships originating from ethnic or racial fusions, from syncretism of religious beliefs and also from other contemporary mixtures between the artisanal and the industrial, the erudite and the popular, the written and the visual in media messages.

5- Engobe consists of an ink made from the clay itself; it is the mixture of clay with water, of a creamy consistency (like that of a liquid yogurt), to which color oxides and/or other pigments can be added to produce various hues.

Received: October 08, 2017; Revised: April 24, 2018; Accepted: June 13, 2018

texto en

texto en