Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 07-Ago-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945194520

SECTION: ARTICLES

Early Childhood Education Service in the State of São Paulo: Ways Foreseen in Municipal Education Plans

1- Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Contato: sanzakia@usp.br.

2- Fundação Carlos Chagas (FCC), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Contato: claudiapimenta68@gmail.com.

Contrary to the legal framework in place, which establishes the need to increase the offer of early childhood education for children from zero to five years old, the State has not yet been able to operate in order to meet this social and educational demand. Offering this education level is mainly the responsibility of municipalities, and they have failed to reach the goal of universal preschool education by 2016 as set forth by the National Education Plan (PNE 2014/2024). With regard to day-care centers, the government does not fulfill its obligation to meet the existing demand, thus restricting the access to education for children from zero to three years old to nearly insignificant figures, with day-care service being often provided by private institutions alone or in partnership with municipalities. This situation led to the development of a study that analyzed proposals presented in the Municipal Education Plans of municipalities in the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo with regard to early childhood education expansion targets and the service modalities foreseen to meet them, thus allowing to assess the potential to reverse the insufficient offer for children at this level of Basic Education. Data collected from the Plans show a tendency of insufficient articulation between the context diagnosis, the expansion goals established and the respective strategies and resources indicated to achieve them, therefore not supporting the assumption that these plans have the potential to meet the demand for early childhood education, especially with regard to day-care centers.

Key words: Right to early childhood education; Early childhood education offer; Municipal education plans; Metropolitan area of São Paulo

À revelia do arcabouço legal existente que estabelece a necessidade do aumento da oferta e do atendimento das crianças de zero a cinco anos, na educação infantil, o Estado ainda não conseguiu operar no sentido de atender a essa demanda social e educacional. Os municípios, principais responsáveis pela oferta da etapa, não alcançaram a meta de universalização da pré-escola até 2016, prevista no Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE 2014/2024). Em relação às creches, o poder público não cumpre o dever de oferecer vagas para a demanda manifesta, o que restringe o acesso à educação para crianças de zero a três anos a percentuais quase irrisórios, cujo atendimento se dá, em muitos casos, por instituições privadas ou conveniadas com as prefeituras. Essa conjuntura motivou o desenvolvimento de estudo que analisou proposições presentes nos Planos Municipais de Educação dos municípios da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo, relativas às metas de expansão da educação infantil e às modalidades de atendimento previstas para o seu cumprimento, o que permite aquilatar o potencial de reversão da carência de vagas para atendimento das crianças nessa etapa da Educação Básica. Os elementos coletados nos Planos evidenciam, como tendência, insuficiente articulação entre o diagnóstico do contexto, as metas de expansão estabelecidas e as respectivas estratégias e recursos indicados para sua consecução, não apoiando a suposição de seu potencial de viabilizar o atendimento à demanda por educação infantil, em especial às creches.

Palavras-Chave: Direito à educação infantil; Oferta de educação infantil; Planos municipais de educação; Região Metropolitana de São Paulo

In Brazil, there is a legal apparatus that ensures the right to early childhood education as the first stage of Basic Education, which is organized in day-care centers for children from zero to three years old and in preschools for children aged four and five. The Federal Constitution of 1988 (CF/88) ( BRASIL, 1988 ) ensures workers the right to free care for their children and dependents, from birth to six years of age in day-care centers and preschools (article 7, XXV) to be provided by the government (article 208, item IV), and it is the municipalities’ duty to offer such services in technical and financial cooperation with the federal and state government levels (article 29, IV). Since then, a set of laws have been enacted which guides and supports the design and implementation of public policies, particularly the National Education Guidelines and Framework Law (BRASIL, LDBN No. 9394/1996), the National Education Plans (BRASIL, Law no. 10172/2001 and Law no. 13005/2014), the Legal Framework for Early Childhood (BRASIL, Law no. 13257/2016), among other regulations that establish parameters that must be met for ensuring young children’s education.

With CF/88, the government’s duty to guarantee access to day-care as a children’s right is recognized, and with the enactment of LDBN no. 9394/1996, the day-care stage is included into Basic Education, thus ceasing to be linked to the field of social work. As for preschool, the government is obliged to provide it free for all children aged four and five since the enactment of Constitutional Amendment No. 59/2009, pursuant to article 208, item I, which sets forth “compulsory basic education free for all from 4 (four) to 17 (seventeen) years of age, including its free offer for all who did not have access to it at proper age” ( BRASIL, 2009 ). Until 2005, the preschool stage comprehended six-year-old children, who then began to be served by basic education, as determined by Laws 11114/2005 and 11274/2006. 3

In accordance with the legislation, the National Education Plan (PNE) for the period from 2014 to 2024, approved through Law 13005 of June 24, 2014, established 2016 as the deadline for universal preschool for children from four to five years of age, and determined that the offer of early childhood education in day-care centers be expanded to cover at least 50% of children up to three years of age by the end of its period in effect.

Studies analyzing available data regarding early childhood education services show that despite the tendency of expansion, there is unmet demand, particularly in day-care centers; they also show unequal access conditions, whether in relation to Brazilian regions and states, or in relation to children’s socioeconomic, race and gender characteristics ( PINTO, 2009 ; FERNANDES; DOMINGUES, 2017 ).

Fulfilling the goals established in the PNE and fighting offer inequalities is mainly a responsibility of municipalities, which are the government level in charge of providing early childhood education, 4 although in most cases, that level lacks the necessary management and planning structure, according to data analyzed by Pinto (2014) .

Municipalities already have the largest number of enrollments, as evidenced by data on enrollment distribution by government level. According to the 2016 School Census, municipalities accounted for 64.2% of day-care center enrollments, although private institutions had a 41.0% share in the number of schools. With regard to preschool, the municipal system had 74.6% of enrollments, and private institutions had 24.3%. (INEP, School Census Summary, 2016).

Universal preschool for children aged four and five is an unfulfilled goal, and care for children up to three years old has been expanding at a pace that does not allow us to suppose that day-care centers will be provided for at least 50% of the population in this age group by 2024.

In 2015, considering IBGE/Pnad population data 5 and Inep/School Census enrollment data, the percentage of children served by pre-school was 93.93%, as shown in Table 1 , which reveals a gap of approximately 6%, which represented over 300,000 unserved children.

Table 1 – Number of children aged 4 and 5 and total preschool enrollments. Brazil: 2015

| Age Group | Number of Children | Total Enrollments | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 years old | 2,620,426 | 4,923,158 | 93.93 |

| 5 years old | 2,620,988 | ||

| Total | 5,241,414 |

Sources: IBGE/Pnad, 2015; INEP/School Census, 2015.

Based on the same sources, i.e., IBGE/Pnad and Inep/School Census, the percentage of children served by day-care in the country in 2015 was 29.54%, as shown in Table 2 , whose figures illustrate the size of the challenge to offer this stage of early childhood education, even if we consider that the real demand for day-care is lower than the total number of children in the 0-3 age group.

Table 2 – Number of children aged 0-3 and total day-care enrollments. Brazil: 2015

| Age Group | Number of Children | Total Enrolments | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below 1 year old | 2,514,012 | 3,049,072 | 29.54 |

| 1 year old | 2,588,944 | ||

| 2 years old | 2,622,680 | ||

| 3 years old | 2,595,396 | ||

| TOTAL | 10,321.032 |

Sources: IBGE/Pnad, 2015; Inep/School Census, 2015.

Although the figures for the state of São Paulo are higher than the national average, the overall offer conditions are the same. Considering the services provided for children in the state’s 645 municipalities in 2015, the percentage of children aged 4 and 5 in school was 93.8%, and for children aged 0 to 3 of 43.5% (Source: IBGE/Pnad, 2015), “which does not mean a positive scenario, given the existing regional disparities” ( FERNANDES; DOMINGUES, 2017 , p. 148).

In addition to the number of children who do not attend school, we must also consider that part of the services provided by municipalities is not through direct enrollment in the public system, but through contracts with private institutions, whether for profit or not, especially with regard to day-care centers, as shown by studies on early childhood education modalities provided through partnerships and/or contracts between municipalities and institutions external to government ( FLORES, 2007 ; SUSIN; PERONI, 2011 ; BORGHI; ADRIAO; GARCIA, 2011; CASAGRANDE, 2012 ; FLORES; SUSIN, 2013 ; SOARES; FLORES, 2014 ; ALMEIDA, 2014 ; FERNANDES; DOMINGUES, 2017 ).

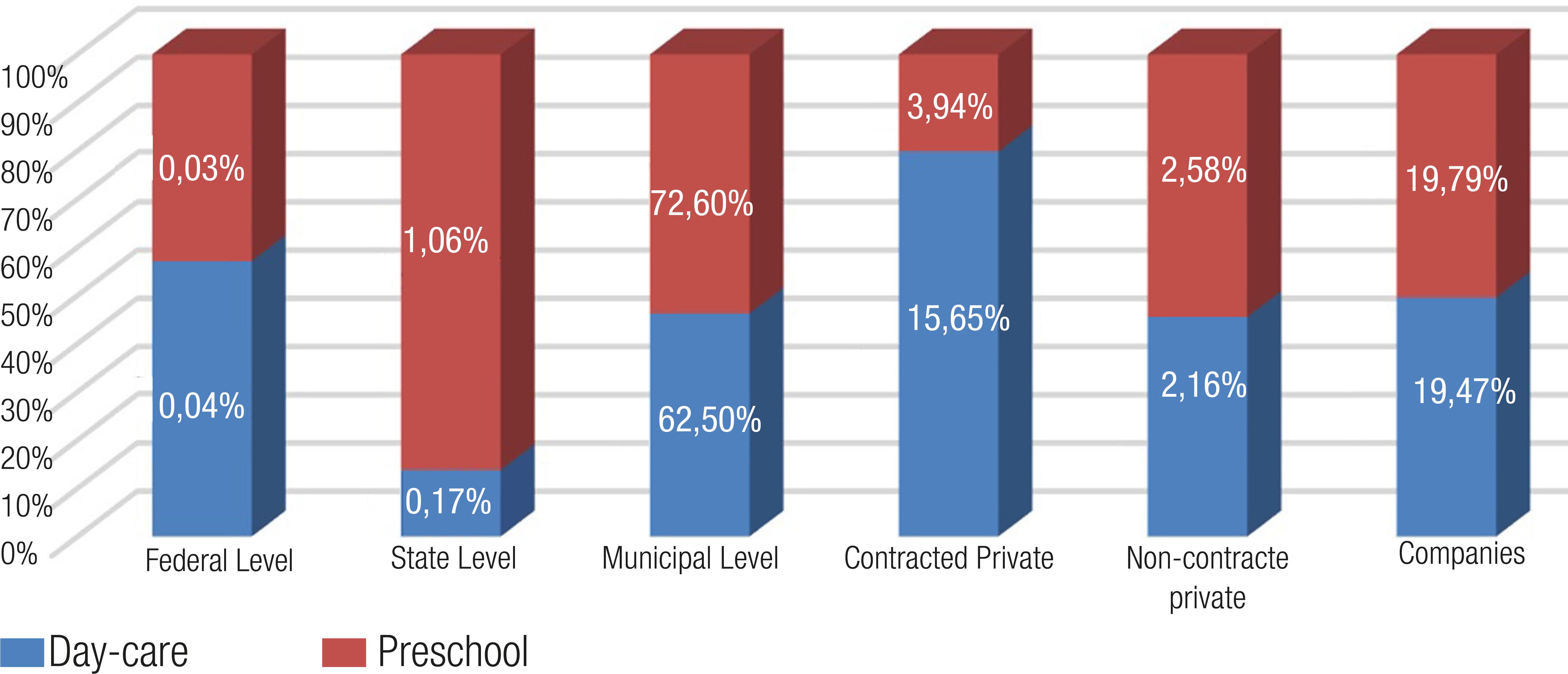

The predominance of non-public service regarding day-care centers for children from 0 to 3 years old can be seen in early childhood education enrollment data by government level in Brazil in 2014 (Inep/School Census 6 ), according to Chart 1 .

Source: Microdata from the School Census/INEP 2014.

Chart 1 – Brazil (2014): Profile of enrollment offer in Early Childhood Education according to government level/private school category

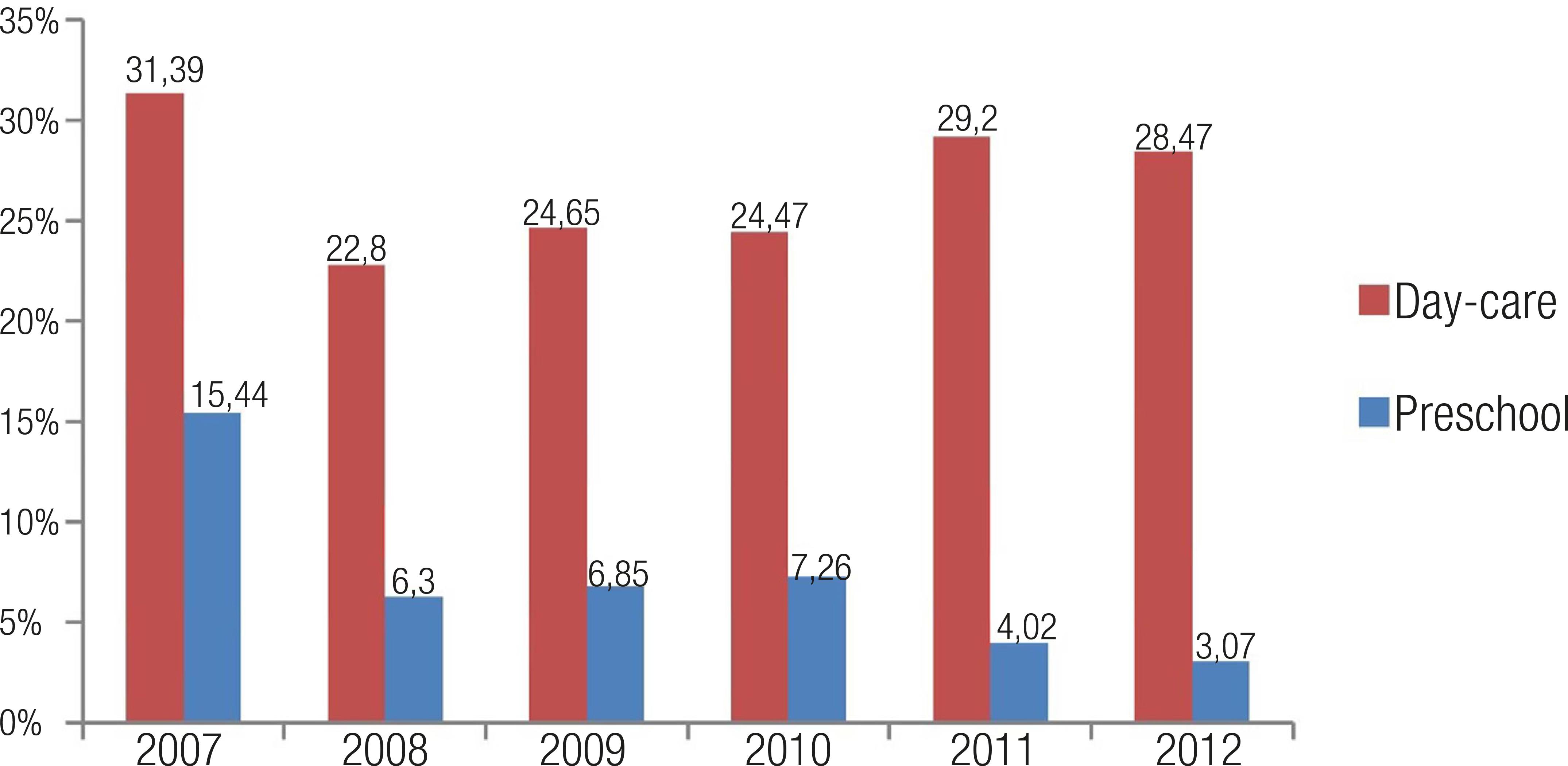

With regard to the state of São Paulo, Fernandes and Domingues (2017) , when dealing with the expansion of early childhood education, presented data for the 2007-2012 period which are reproduced in the chart below:

Source: The Seade Foundation (Ministry of Education – MEC/National Institute for Educational Studies and Research – Inep. School Census) – prepared by Fernandes and Domingues (2017) .

Chart 2 – Share of contracted private schools in the total initial day-care and preschool enrollments in the state of São Paulo in the 2007-2012 period, in percentage

With regard to PNE’s goals, Tripodi (2016) analyzes the tendency for early childhood education to be offered by the non-governmental public sector through contracts under the hypothesis below:

[...] that municipalities will tend to intensify some forms of governance which have been arising and which favor the way governments act in partnership with the non-governmental public sector under the terms defined by the Pdrae 7 (1995) to serve that stage of basic education. These are driven by three main factors, namely: i) an imprecise federalism of collaboration in which the bases of federal cooperation towards municipalities are not clearly defined; ii) bold early childhood education goals for municipalities in a context of scarce resources and less institutional capacity ; iii) the enactment of Law no. 13019 of July 31, 2014, one month after Law 13005/2014, which establishes the legal framework of voluntary partnerships that may or may not involve the transfer of funds between the government and civil society organizations on a mutual cooperation basis in order to achieve goals of public interest. ( TRIPODI, 2016 , p. 289).

Along with this hypothesis, it is also necessary to consider that the PNE itself allows partnerships between government and civil society organizations, e.g., when it defines as one of the strategies to achieve the expansion of early childhood education (Goal 1): “to combine the offer of free enrollments in day-care centers that are certified as social service entities in the education field with the expansion of the offer by the public school system” (BRASIL, PNE, 2014, p. 2).

Like Dourado (2016) notes in a study that analyzes the PNE 2014-2024,

Several strategies reflect the scope of the clash between public and private offers [...] as the emergence of partnerships between public institutions and community, denominational and philanthropic institutions that resulted from the main clashes occurring in the PNE enactment process. How will these policies be actually implemented? There is no doubt that the funds, i.e., the public funds, are a disputed field in the Plan’s materialization scenario. ( DOURADO, 2016 , p. 29).

This situation leads us to assume that in order for municipalities to respond to the demand for early children education, particularly in day-care centers, they will tend to keep or even increase the use of contracts with private institutions in the design of policies for the offer of that stage.

In this context, we identified the research opportunity for analyzing the proposals presented in the Municipal Education Plans (PME) of municipalities in the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo (RMSP) 8 regarding the early childhood education expansion goals and the proposed modalities for meeting these goals as set forth in the Plans.

The geographic scope was so defined because the RMSP concentrates the largest number of people in the state and is therefore the country’s largest population agglomeration, comprising 39 municipalities, namely: Arujá, Barueri, Biritiba-Mirim, Caieiras, Cajamar, Carapicuíba, Cotia, Diadema, Embu das Artes, Embu-Guaçu, Ferraz de Vasconcelos, Francisco Morato, Franco da Rocha, Guararema, Guarulhos, Itapecerica da Serra, Itapevi, Itaquaquecetuba, Jandira, Juquitiba, Mairiporã, Mauá, Mogi das Cruzes, Osasco, Pirapora do Bom Jesus, Poá, Ribeirão Pires, Rio Grande da Serra, Salesópolis, Santa Isabel, Santana de Parnaíba, Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, São Caetano do Sul, São Lourenço da Serra, São Paulo, Suzano, Taboão da Serra and Vargem Grande Paulista. Together, these municipalities totaled approximately 22 million inhabitants in 2015, which represented more than 10% of the Brazilian population in that year. In addition, propositions presented by large municipalities tend to be taken as a model of public policy design, including educational policies, which allows us to assume that other municipalities in the state tend to replicate alternatives adopted in the RMSP municipal education system.

In the present article, we map the expansion goals and the strategies established in the plans of these municipalities by identifying the plans’ expected offer and the alternatives foreseen for meeting these expansion goals. This information is analyzed in the interface with data concerning the funds of each of them, in order to problematize the municipalities’ conditions to implement the early childhood expansion goal. To that end, we collected tax revenue data for 2014. Finally, we present considerations regarding the tendencies expressed in the analyzed plans.

Study Procedure

The PMEs were the source of information about the planning of early childhood education expansion in the RMSP municipalities and were collected by consulting the Ministry of Education’s PNE em Movimento portal. 9

In order to fulfill the purpose announced in this article, we initially collected from the Plans information concerning the existing enrollments for day-care and preschool in the municipal territories, in order to identify the municipal education system’s share in the coverage, the number of establishments that provide early childhood education, and the goals and strategies related to expanding the offer of this educational stage.

The 39 municipalities that make up the RMSP have some document available on the portal, 30 of which displayed the Law and the Annex on this website, five only the Law and four only the Annex, at the time of retrieval. In order to obtain the plans of all the municipalities that make up the Area, we consulted the websites of the city governments, municipal councils and/or education departments of the municipalities whose documents were not found in the PNE em Movimento portal. As a result, we included two more Annexes into the study’s corpus.

Consulting the Annexes was a fundamental procedure, since this document contains, in general lines, the diagnosis of municipal education, the municipal guidelines for education and the goals and strategies foreseen for each stage of basic education and for higher education. Therefore, in this article we analyze 36 plans whose Annexes were found.

The documents revealed a diversity of available information about municipal planning for early childhood education expansion, with different levels of coverage and detail. Therefore, the assessments presented in this article reveal tendencies for which more in-depth examination will require further studies that extend the consultation sources.

In order to present an overview of Brazil’s early childhood education services, we used information made available by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP) and the National Household Sample Survey (Pnad), in addition to information contained in the Municipal Plans of Education of the RMSP municipalities.

The Diagnosis that Founded the Extent of the Expansion Goal

Considering that one of the conditions for analyzing the Plans’ propositions is a diagnosis that allows the comparison between the situation at the time of its design and the prospects presented, it should be noted that this assessment cannot be made for all municipalities examined in the present study, since we have 36 Annexes out of 39 Municipal Plans. In addition, not all documents present a diagnosis of the educational situation in the municipality, or the diagnosis is poorly presented, as we will see below.

With regard to enrollments, of the 36 plans analyzed, only 21 recorded the number of children served by day-care and preschool, four of which do not indicate what year the data refer to (Biritiba-Mirim, Cajamar, Ferraz de Vasconcelos and Franco da Rocha), one presents data for 2010 (Cotia), four for 2013 (Arujá, Barueri, Jandira and São Caetano do Sul), seven for 2014 (Itapecerica da Serra, Mairiporã, Mogi das Cruzes, Rio Grande da Serra, Salesópolis, Santa Isabel and São Lourenço da Serra) and five for 2015 (Carapicuíba, Embu-Guaçu, Guararema, Santana de Parnaíba and Taboão da Serra). The sources the municipalities used to collect enrollment information varied: Inep/School Census; the Seade foundation; the São Paulo State Education Department’s Dynamic School Management Portal (GDAE); and also information organized by the municipality itself.

Also regarding enrollments, it should be noted that 16 of the 21 municipalities indicate the total number of children served by government level, and five report only the total number of enrollments in the municipality, with no mention to each level’s share.

Of the 21 municipalities, only three indicate the enrollments in institutions contracted by the government (Carapicuíba, Ferraz de Vasconcelos and Mogi das Cruzes). The number of contracted enrollments is unlikely to represent the real extent of this practice, considering that it has been usual for municipalities to record enrollments maintained by the government in private institutions as municipal enrollments.

Still with regard to these municipalities, only 13 report the percentage or the number of children served in early childhood education in relation to the total of children aged 0-5 in their territories, 10 of which refer to day care and preschool, two only to daycare and one does not separate the two stages.

Day care is the most hindered in terms of offer and provided services, with only three of the 13 municipalities serving more than 50% of children in this age group in 2013, 2014 and 2015, according to data from the diagnosis presented by PMEs. It is also worth noting that in the case of day-care centers, one should consider the manifest demand (when the family sought the service) and the potential demand (number of children in the municipality), which was seldom specified in the plans or dealt with incorrectly. This incorrect treatment is illustrated by the case of a municipality that establishes as one of its strategies for preschool offer expansion “to ensure the continuation of 100% of the manifest demand of students aged 4 and 5 – Preschool” (PME/Barueri). Since preschool is compulsory, it is the State’s duty to seek all unserved children in this age group, i.e., to meet only the manifest demand is the same as not to serve all children and therefore not to fulfill universal preschool.

These findings show that, in several municipalities, the planning document that is published and made available to society lacks elements that allow assessing the municipal government’s effort and commitment to fulfill the right to education in this stage of Basic Education, since such document lacks even data to found the examination of the relationship between offer, demand and expansion goals.

In a document prepared by the Ministry of Education/Secretariat of Articulation with the Education Systems (MEC/SASE, 2015), with a view to supporting the constitution of the National Education System (SNE), there is mention to the necessary articulation between the national, state and municipal education plans for fully implementing the SNE. However, it emphasizes the importance for subnational plans to include propositions based on local contexts, a fundamental requirement to ensure the realism and feasibility of plans and, ultimately, the realization of the right to education.

However, the analysis of PMEs with regard to planning the expansion of early childhood education has shown that the practice of reproducing the PNE 2014-2024 goals has been dominant, although some municipal plans show small differences in relation to the national document.

In addition to the tendency not to indicate expansion goals of their own, especially with regard to day-care centers, where there are data indicating a large unmet demand (FERNANDES, DOMINGUES, 2017), the Plans do not include, for this education stage, differentiated initiatives that take into account local inequalities in children’s access to early childhood education, whether due to their socioeconomic level or race and gender, except for the municipality of Cotia’s PME, which deals with ethnic-racial diversity and the guarantee of specific buildings for this educational stage, respecting diversity and the local context. Other 24 PMEs have strategies distributed over other goals, especially focusing on ethnic-racial issues and rural education, mostly related to building the curriculum for basic education as a whole and purchasing didactic-pedagogical material.

Strategies Foreseen for Expanding Early Childhood Education Offer

With regard to offer expansion, 30 municipalities present in their Plans general strategies for early childhood education as a whole and/or specific to day-care and/or preschool. Analyzing the Plans of these 30 municipalities revealed that 24 of them foresee specific strategies for day-care, which suggests their concern in clarifying the measures they intend to take to fulfill the expansion of this segment. Six others specify strategies for preschool. It should be noted that five municipalities presented only general strategies involving that stage as a whole. ( Table 3 )

Table 3 Number of municipalities and type of strategy foreseen for early childhood education expansion

| Expansion Strategies | Municipalities |

|---|---|

| General strategies for ECE | 5 |

| General strategies for ECE and specific for day-care | 18 |

| General strategies for ECE and specific for preschool | 1 |

| General strategies for ECE and specific for day-care and preschool | 3 |

| Specific strategies for day-care and preschool | 2 |

| Strategies for day-care only | 1 |

| Total Municipalities | 30 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The strategies with most indications in the Plans, regardless of whether they were specifically defined for day-care or preschool, or whether there was no explicit mention to the stage they were intended for were: expanding the number of schools in collaboration with the federal and state governments/participating in federal and/or state government programs; and ii) expanding the offer by combining enrollments in the direct system with enrollments in contracted institutions. The strategy of building and/or expanding school units by using the municipalities’ own resources was indicated only a few times and was presented in combination with other strategies in some municipalities, which seems to stress the municipalities’ difficulties to autonomously fund the expansion of this education stage. Some Plans also mention the use of private resources to build and/or expand educational units. Table 4 shows the number of indications of these and other strategies related to the expansion of early childhood education offer in the analyzed Plans.

Table 4 Strategies foreseen for expanding early childhood education

| Strategies | Indications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-care only | Preschool only | Stage not specified | Total by type of strategy | |

| Expanding the number of schools in collaboration with the federal and state governments/participating in federal and/or state government programs | 8 | 3 | 19 | 30 |

| Expanding the offer by combining enrollments in the direct system with enrollments in contracted institutions | 17 | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| Building and/or expanding units, but funds for this are not mentioned | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Building and/or expanding with own funds | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Building and/or expanding funded by private sector | 1 | - | 2 | 3 |

| Building and/or expanding with government funds, but the source is not mentioned | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Expanding the offer with enrollments in day-care on evenings | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Expanding the offer in the direct public day-care system | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Prioritizing preschool | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Reducing ECE hours to expand the offer | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Total Indications | 34 | 8 | 29 | 71 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

As can be seen, the need for states and the federal government to collaborate with municipalities in order for them to meet their expansion goals is indicated in most municipal plans. Analyzing these documents did not allow us to specify the amount of funds foreseen by the municipalities to fulfill their goals and respective strategies, which would be indispensable to assess the extent to which the municipalities are actually capable of carrying them out.

For an exploratory consideration of this issue, we sought to infer the municipalities’ financial ability to fulfill their early childhood education expansion goals based on tax revenue data for 2014; we assume that the Municipal Education Departments relied on such data to design their educational strategies, since most of the Plans began their implementation in 2015. One must also bear in mind that the municipalities’ revenue is allocated to different areas, education being one of them.

Tax revenue data were collected from the meumunicipio.org.br portal and refer to: Tax Revenues (which refers to amounts collected by the municipality itself); Intergovernmental revenues (concerning transfers made by the state and federal levels to the municipality); and the Revenue Result Indicator (which “measures the percentage that the municipality has been able to save or that it has spent in excess of its total revenue” 10 ). Table 5 lists these data for each municipality, except for four of them, for which no information was available for 2014, the year prior to the enactments of the PMEs: Biritiba-Mirim, Itapevi, Taboão da Serra and Vargem Grande Paulista. 11

Table 5 – Tax revenue data for RMSP municipalities, 2014

| Municipalities | Tax Revenues | Intergovernmental Transfer Revenues | Municipality Revenue Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salesópolis | 6.57% | 89.10% | -12.40% |

| Francisco Morato | 9.49% | 78.86% | -5.85% |

| Rio Grande da Serra | 10.99% | 79.21% | -70.10% |

| Ferraz de Vasconcelos | 11.50% | 78.00% | -6.38% |

| Embu-Guaçu | 12.09% | 80.87% | -6.81% |

| Pirapora do Bom Jesus | 12.44% | 80.62% | -2.45% |

| Juquitiba | 12.68% | 70.32% | -6.24% |

| Embu das Artes | 13.49% | 63.84% | 2.70% |

| Guararema | 13.85% | 80.53% | 1.39% |

| Franco da Rocha | 13.96% | 72.10% | 3.11% |

| Itapecerica da Serra | 14.44% | 73.99% | 0.57% |

| Santa Isabel | 14.89% | 73.98% | -2.16% |

| Mauá | 16.67% | 60.81% | -0.87% |

| Jandira | 17.25% | 63.23% | 10.62% |

| São Lourenço da Serra | 18.38% | 71.14% | -5.43% |

| Suzano | 20.14% | 66.68% | 5.07% |

| Mairiporã | 20.75% | 62.65% | 0.55% |

| Ribeirão Pires | 21.40% | 64.90% | -6.53% |

| Diadema | 23.32% | 58.97% | -3.80% |

| Carapicuíba | 23.62% | 65.74% | -0.36% |

| Caieiras | 24.37% | 63.79% | 1.52% |

| Guarulhos | 25.01% | 57.55% | -4.66% |

| Mogi das Cruzes | 25.11% | 64.18% | 10.78% |

| Arujá | 25.76% | 65.64% | 0.14% |

| Cotia | 25.87% | 56.44% | 19.18% |

| Cajamar | 26.41% | 62.50% | 5.53% |

| São Bernardo do Campo | 27.50% | 57.60% | -2.34% |

| Itaquaquecetuba | 29.66% | 59.48% | 19.44% |

| São Caetano do Sul | 31.55% | 49.43% | -1.18% |

| Santo André | 32.26% | 41.99% | -5.30% |

| Santana de Parnaíba | 35.27% | 52.10% | 12.83% |

| Osasco | 36.88% | 49.34% | -6.25% |

| Barueri | 42.11% | 52.75% | 3.96% |

| São Paulo | 50.51% | 33.33% | -4.18% |

| Poá | 51.79% | 42.63% | 1.97% |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Of the 35 municipalities whose revenue data for 2014 were available at the time of retrieval, 33 (94.28%) had a lower percentage of own revenues than the percentage received from state and federal governments, which indicates their financial fragility to meet demands in the various areas. Only São Paulo and Poa had greater own revenues than the transfers made by the other government levels. Nevertheless, the former spent beyond its Total Revenue, as can be seen in its Revenue Result Indicator, which was negative for this municipality.

In addition to São Paulo, 18 other municipalities also had negative results by the end of 2014, with Salesopolis presenting the highest percentage of spending in excess of the amount it had. It is worth noting that this municipality has the lowest percentage of own resources, with 90% of its Total Revenues formed by federal and state funds.

It should be noted that the Fundeb is part of the so-called Intergovernmental Transfer Revenues. This Fund is dedicated to basic education only and it aims to complement municipal funds in order to meet education-related demands. However, it seems the amounts are still far from realizing that purpose. With regard to the municipalities analyzed, two did not receive Fundeb funds in 2014. In one, Fundeb accounts for less than 10% of the aforementioned revenues. In nine municipalities, the percentage ranges from 11% to 20%. In 17, the percentage varies slightly more than the 20-25% interval, and in the remaining five, from 30% to 39%.

The revenue data presented reveal the need to strengthen the collaboration between municipalities, states and the federal government in order to meet the goals set forth in PMEs, which explains the Plans’ mention of actions to expand the number of schools through collaboration with the other government levels and through participation in federal and/or state government programs. However, this reference is generic and suggests the fragility of the strategies foreseen to fulfill the goals of expanding early childhood education, since there are no stable mechanisms for carrying out collaborative actions involving the different levels of government, although indications in this respect can be found in Law 13005/2014.

This Law sets forth that the federal government, the Federal District, the states and municipalities are to cooperate in order to implement the PNE’s strategies and achieve its goals. In its Article 7, which deals with the form of collaboration, the Law prescribes a few initiatives that are conditions for that collaboration to take place. It is worth highlighting the contents of a few paragraphs in this Article:

Paragraph 5. A permanent body shall be created for negotiation and cooperation between the Federal Government, the States, the Federal District and the Municipalities.

Paragraph 6. The strengthening of the collaboration between the States and their respective Municipalities shall include the establishment of permanent bodies for negotiation, cooperation and agreement in each State. (BRASIL, Law 13005/2014, Article 7).

The same Article of the aforementioned Law says local initiatives are necessary in that direction:

Paragraph 2. The strategies defined in the Annex to this Law do not prevent the adoption of additional measures at the local level or of legal instruments that formalize cooperation between different government levels, and said strategies may be complemented by national and local mechanisms of coordination and reciprocal collaboration. (BRASIL, Law 13005/2014, Article 7).

Resuming the strategies indicated by municipalities to carry out the expansion of early childhood education, we should also point out that contracts with private philanthropic, denominational and/or community institutions were the second most mentioned strategy to meet service and offer expansion goals: 17 strategies specifically directed to day-care, two to preschool and two to early childhood education as a whole.

This course of action can result in offer expansion with a focus on quantity rather than on the quality of the service provided for young children. In dealing with the impact of this policy option on the part of municipal authorities, Flores and Susin (2013) emphasized that this type of alternative needs to be properly analyzed, since non-compliance with the constitutional precepts of gratuitousness, secularity and quality by the contracted institutions would not be a true democratization of the right to early childhood education.

Research has shown that the service indicators for contracted institutions are usually worse than those for public ones, as mentioned earlier in this article. This is illustrated by an audit conducted by the São Paulo Municipal Court of Auditors which compared the conditions in contracted day-care centers with units directly run by the municipal education department, the results of which were disclosed in the São Paulo Municipal Court of Auditors’ Audit Report (PROCEDURE No. 7200639016-71, of 2017), which highlights how this type of service is marked by precariousness. 12 The audit’s goal was “to evaluate how Early Childhood Education is operationalized towards education quality, and with a focus on contracted institutions”. ( SÃO PAULO, 2017 , p. 3).

Based on collected evidence, the Report notes that, on average, education is provided in worse conditions in contracted day-care centers than in establishments directly run by the municipal government, and it indicates, among others: an inadequate proportion of students per teacher, more teachers with inadequate training, lower wages, higher staff turnover and poor infrastructure in school buildings. In conclusion, it reports as follows:

In this context, we conclude that early childhood education in the city of São Paulo presents anomalies in the development of educational process actions, with operationalization differences between the direct and the contracted systems. (SÃO PAULO, 2017, p. 68).

The situation found in the municipality of São Paulo is possibly not peculiar of what tends to result from the decision to offer early childhood education, particularly day-care, by privatizing its offer. Hence the concern about the fact that this alternative of service for the child population is proposed in many municipal Plans, which points to prospects of permanence and expansion of this practice in public education.

Final Indications

The information presented in this article with regard to the proposals presented in the Municipal Education Plans of municipalities in the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo provide a panorama of how the expansion of early childhood education in these places has been laid out so far.

Based on elements collected from the Plans, one can say that, in general, they lack information to found themselves or to provide evidence of articulation between context diagnosis, the expansion goals established and the respective strategies to be mobilized to achieve them.

With regard to the expansion goals set out in the Plans, we showed that they converge to reproduce what is foreseen in the PNE, and that there are no sufficient elements to estimate what their accomplishment will represent in terms of ensuring the right to education for children living in these municipalities. There is a tendency for incomplete and/or inaccurate records of municipal demands, as well as precarious references to local contexts; this gap is also observed in the lack of information on unequal access conditions, whether in relation to geographical distribution or to children’s socioeconomic, race and gender characteristics.

The strategies listed to reach the goals established reinforce the perception of fragility about the proposals outlined to fulfill the expansion of this stage of Basic Education. Indications predominantly refer to building new educational units and/or refurbishing existing ones, however, the main – when not the only – way indicated to achieve this is by participating in federal and/or state government programs, on a collaboration basis between different government levels. Although we have verified, by means of municipal tax revenue data, the municipalities’ financial dependence on state and federal governments, Brazil still lacks clarity as to the responsibilities and limits of each government level in guaranteeing the right to education, i.e., in realizing the construction of the National Education System. And although Article 13 of Law 13005/2014 has attributed to the institution of this system the task of connecting the various education systems on a collaboration basis in order to achieve the PNE’s goals, it has not yet materialized.

The other strategy found in the Plans is the maintenance or expansion of contracts with private institutions, particularly concerning the expansion of enrollments in day-care centers, an option that is supported by current legislation. In this respect, the present article highlighted Law 13019/2014, which establishes the legal framework of voluntary partnerships between the government and civil society organizations, as well as PNE Strategy 1.7, which foresees the offer of free enrollments in day-care centers that are certified as social service entities in order to expand day-care offer. However, contributions of studies and research already published in Brazil, some of which were mentioned in this text, have revealed that this path ends up reinforcing social inequalities.

In general terms, the paths foreseen in the municipal education plans analyzed in this article seem to jeopardize the guarantee of every child’s right to early childhood education. They can also be interpreted as evidence that most municipalities lack sufficient planning and financial capacities ( PINTO, 2014 ) and that the framework of collaboration between different government levels needs further regulation as foreseen in the Federal Constitution of 1988 . Overcoming the public service gap in early childhood education necessarily presupposes cooperation and joint planning between the federal, state and municipal levels of government.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Volnei Bispo de. As parcerias público-privadas na educação infantil. 2014. 102 p. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Humanidades e Direitos, Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014. [ Links ]

ARUJÁ. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei n° 2.760 de 24 de junho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação – PME de Arujá e dá outras providências. Arujá: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

BARUERI. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 2.408, de 22 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação da Cidade de Barueri - PME. Diário Oficial de Barueri , ed. 674, 23 jun. 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

BIRITIBA MIRIM. Prefeitura. Lei nº 1.731, de 30 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a instituição do Plano Municipal de Educação de Biritiba Mirim e dá outras providências. Biritiba Mirim: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Senado Federal. Congresso Nacional. Lei nº 13.257, de 8 de março de 2016. Dispõe sobre as políticas públicas para a primeira infância e altera a Lei nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990 (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente), o Decreto Lei nº 3.689, de 3 de outubro de 1941 (Código de Processo Penal), a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT), aprovada pelo Decreto Lei nº 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, a Lei nº 11.770, de 9 de setembro de 2008, e a Lei nº 12.662, de 5 de junho de 2012. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF, n. 46, Seção 1, p. 1-4, 09 mar. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF, n. 120-A, Seção 1, ed. extra, p. 1-7, 26 jun. 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Congresso Nacional. Emenda Constitucional Nº 59, de 11 de novembro de 2009. Diário Oficial a União , Brasília, DF, n. 216, Seção I, p. 8, 12 nov. 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Congresso Nacional. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF, p. 27894, 23 dez. 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Congresso Nacional. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil . Brasília, DF: Senado Federal, 1988. [ Links ]

BORGHI, Raquel; ADRIÃO, Theresa; GARCIA, Teise. As parcerias público-privadas para a oferta de vagas na educação infantil: um estudo em municípios paulistas. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos , Brasília, DF, v. 231, p. 124, 2011. [ Links ]

CAIEIRAS. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 4.779, de 19 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação – PME do município de Caieiras, com vigência decenal, e dá outras providências. Caieiras: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

CAJAMAR. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 1.631, de 18 de dezembro de 2015. Dispõe sobre a aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Cajamar, para o período de 2015 a 2025. Cajamar: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em: <http://simec.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

CARAPICUÍBA. Prefeitura Municipal. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Plano Municipal de Educação. Carapicuíba: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

CASAGRANDE, Ana Lara. As parcerias entre o público e o privado na oferta da educação infantil em municípios médios paulistas. 2012. 203 p. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio De Mesquita Filho, Rio Claro, 2012. [ Links ]

COTIA. Prefeitura. Lei nº 1.895 de 23 de junho de 2.015. Atualiza o Plano Municipal de Educação, aprovado nos termos do Anexo Único da Lei nº 1.775, de 15 de agosto de 2013. Cotia: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

DIADEMA. Prefeitura do Município. Lei Ordinária nº 3584 de 12 de abril de 2016. Dispõe sobre a aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação – PME (Anexo Único). Diadema: Prefeitura, 2016. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

DOURADO, Luiz Fernandes. Plano Nacional de Educação: política de estado para a educação brasileira. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2016. [ Links ]

EMBU DAS ARTES. Prefeitura Municipal da Estância Turística. Lei nº 2.827, de 18 de junho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. Embu das Artes: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

EMBU GUAÇU. Câmara Municipal. Lei Municipal nº 2.826, de 13 de julho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação de Embu Guaçu. Embu Guaçu: Câmara Municipal, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Fabiana Silva; DOMINGUES, Juliana dos Reis. Educação infantil no estado de São Paulo: condições de atendimento e perfil das crianças. Educação e Pesquisa , São Paulo, v. 43, p. 145-160, 2017. [ Links ]

FERRAZ DE VASCONCELOS. Prefeitura Municipal. Plano Municipal de Educação. Ferraz de Vasconcelos: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

FLORES, Maria Luiza Rodrigues. Movimento e complexidade na garantia do direito à educação infantil: um estudo sobre políticas públicas em Porto Alegre (1989-2004). 2007. 292 p. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Educação da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2007. [ Links ]

FLORES, Maria Luiza Rodrigues; SUSIN, Maria Otília K. Expansão da educação infantil através de parcerias públicos-privada: algumas questões para o debate (quantidade versus qualidade no âmbito do direito à educação). In: PERONI, Vera Maria Vidal (Org.). Redefinições das fronteiras entre o público e o privado: implicações para a democratização da educação. Brasília, DF: Liber Livro, 2013. p. 220-244. [ Links ]

FRANCISCO MORATO. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 2.837/2015, de 23 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a implantação do Plano Municipal da Educação. Francisco Morato: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

FRANCO DA ROCHA. Prefeitura do Município. Plano Municipal da Educação Decênio 2014/2024 . Franco da Rocha: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

GUARAREMA. Câmara Municipal. Lei nº 3090, de 17 de Junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. Guararema: Câmara Municipal, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

GUARULHOS. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 7.598, de 01 de dezembro de 2017. Aprova o Plano de Educação da Cidade de Guarulhos – PME para o período 2017/2027. Guarulhos: Prefeitura, 2017. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. PNAD. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios. População de 0 a 3 anos em 2015 . Brasília, DF: IBGE/PNAD, 2015. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. PNAD. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios. População de 4 e 5 anos em 2015 . Brasília, DF: IBGE/PNAD, 2015. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Microdados do censo escolar. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2014. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse estatística da educação básica . Brasília, DF: INEP, 2015. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse estatística da educação básica . Brasília, DF: INEP, 2016. [ Links ]

ITAPECERICA DA SERRA. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 2.470, de 24 de junho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Itapecerica da Serra, e dá outras providências. Itapecerica da Serra: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

ITAPECERICA DA SERRA. Prefeitura do Município. Plano municipal de educação do município de Itapecerica da Serra . Itapecerica da Serra: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 23 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

ITAPEVI. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 2.404, de 29 de junho de 2016. Dispõe Sobre o Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Itapevi para o Decênio 2015-2025 e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial do Município de Itapevi, v. 8, n. 391, 01 jul. 2016. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

ITAQUAQUECETUBA. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 3.210, de 24 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação, para o decênio 2016-2025, na forma a seguir especificada, e adota outras providências. Itaquaquecetuba: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

JANDIRA. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 2.106 de 24 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação de Jandira. Jandira: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

JUQUITIBA. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 1.905, de 30, de junho de 2014. Dispõe sobre aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação para a década de 2014 a 2023. Juquitiba: Prefeitura, 2014. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

MAIRIPORÃ. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 3.522, de 24 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre aprovação do Plano Municipal da Educação do Município de Mairiporã e dá outras providências. Mairiporã: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

MAUÁ. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 5.097, de 16 de outubro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Mauá e dá outras providências. Mauá: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. SECRETARIA DE ARTICULAÇÃO COM OS SISTEMAS DE ENSINO. DIRETORIA DE ARTICULAÇÃO COM OS SISTEMAS DE ENSINO. Instituir um Sistema Nacional de Educação: agenda obrigatória para o país. Brasília: SASE/MEC/2015. Disponível em: < http://pne.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/SNE_junho_2015.pdf >. Acesso em 10 jun. 2018. [ Links ]

MOGI DAS CRUZES. Prefeitura. Lei nº 7.039, de 27 de março de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação para o biênio 2015/2016, elaborado pelo Conselho Municipal de Educação. Mogi das Cruzes: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

OSASCO. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 4.701, de 02 de julho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. Osasco: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

PINTO, José Marcelino de Rezende. Perfil da Educação Infantil no Brasil: indicadores de acesso e condições de oferta. In: BRASIL. MEC. SEB. Política de educação infantil no Brasil: Relatório de avaliação. Brasília: MEC/SEB; Unesco, 2009, p. 121-168. [ Links ]

PINTO, José Marcelino de Rezende. Federalismo, descentralização e planejamento da educação: desafios aos municípios. Cadernos de Pesquisa , São Paulo, v. 44, n. 153, p. 624-644, 2014. [ Links ]

PIRAPORA DO BOM JESUS. Prefeitura. Lei nº 1.082, de 24 de julho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação (PME) de Pirapora do Bom Jesus – 2015/2025. Pirapora do Bom Jesus: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

POÁ. Prefeitura. Lei nº 3.806, de 23 de junho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. Poá: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

RIBEIRÃO PIRES. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei Municipal nº 5.995, de 30 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação da Estância Turística de Ribeirão Pires, e dá outras providências. Ribeirão Pires: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DA SERRA. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei Municipal nº 2.134, de 23 de setembro de 2015. Altera o Anexo Único da Lei Municipal nº 2.130, de 30 de junho de 2015, que aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Rio Grande da Serra. Rio Grande da Serra: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SALESÓPOLIS. Prefeitura. Lei nº 1.716, de 13 de outubro de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação da Estância Turística de Salesópolis, na conformidade do artigo 8º da Lei Federal nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014, e dá outras providências. Salesópolis: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SANTA ISABEL. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 2.802, de 20 de outubro de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação – PME no Município de Santa Isabel e dá outras providências. Santa Isabel: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SANTANA DE PARNAÍBA. Prefeitura Municipal. Plano Municipal de Educação de Santana de Parnaíba. Santana de Parnaíba: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SANTO ANDRÉ. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 9.723, de 20 de julho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação do Município de Santo André – PME para o decênio de 2015-2025 e dá outras providências. Santo André: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SÃO BERNARDO DO CAMPO. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 6.447, de 28 de dezembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação de São Bernardo do Campo, revoga a Lei Municipal nº 5.224, de 25 de novembro de 2003, e dá outras providências. São Bernardo do Campo: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SÃO CAETANO DO SUL. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 5.316, de 18 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. São Caetano do Sul: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SÃO LOURENÇO DA SERRA. Prefeitura. Lei nº 1.054, de 22 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a criação do Plano Municipal de Educação e dá outras providências. São Lourenço da Serra: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: <http://simec.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Prefeitura do Município. Lei nº 16.271, de 17 de setembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Municipal de Educação de São Paulo (Anexo Único). Diário Oficial da Cidade de São Paulo, v. 60, n. 74, 18 set. 2015. Disponível em: <http://simec.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Tribunal de Contas do Município. Relatório de auditoria extraplano: Processo nº 72.006.390.16-71. São Paulo: TCM, 2017. [ Links ]

SOARES, Gisele Rodrigues; FLORES Maria Luiza Rodrigues. Expansão da educação infantil no Brasil: contexto recente e desafios atuais. Políticas Educativas , Porto Alegre, v. 8, n. 1, p. 85-106, 2014. [ Links ]

SUSIN, Maria Otília Kroeff; PERONI, Vera Maria Vidal. A parceria entre o poder público municipal e as creches comunitárias: a educação infantil em Porto Alegre. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação , Goiânia, v. 27, n. 2, maio/ago. 2011. [ Links ]

SUZANO. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei Complementar nº 275 de 23 de junho de 2015. Institui o Plano Municipal de Educação 2015/2025, e dá outras providências. Suzano: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

TABOÃO DA SERRA. Prefeitura Municipal. Lei nº 2.223, de 25 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre aprovação do Plano Municipal de Educação (Anexo Único). Imprensa Oficial do Município de Taboão da Serra, v. 8, ed. 614, 26 Jun. 2015. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

TRIPODI, Zara Figueiredo. Educação infantil: da diversidade de oferta aos novos locais de governança. Educação , Porto Alegre, v. 39, n. 3, p. 383-392, set./dez. 2016. [ Links ]

VARGEM GRANDE PAULISTA. Prefeitura. Lei nº 885, de 24 de junho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a instituição do Plano Municipal de Educação 2015-2025 e dá outras providências Vargem Grande Paulista: Prefeitura, 2015. Anexo único. Disponível em: < http://simec.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

3- Law No. 11114, of May 16, 2005, makes the beginning of elementary education at the age of 6 compulsory, and Law 11274, of February 6, 2006, provides for the 9-year period for basic education, with compulsory enrolment from the age of 6.

4- Although municipalities are the government level that is primarily in charge of providing early childhood education, the legislation in effect sets forth that in the Brazilian federation system, the federal, state and municipal government levels and the Federal District should cooperate in order to ensure children’s rights.

5- Data from IBGE/Pnad referring to the number of children aged 0 to 5 in Brazil in 2015 were treated by Amélia Artes, a researcher at the Carlos Chagas Foundation (FCC).

6- The data used to make Graph 1 were collected and treated by Thiago Alves, a faculty member and researcher at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR).

7- The Master Plan for Reform of the State Apparatus of 1995, designed by the Ministry of Federal Administration and State Reform, which introduces the concept of non-governmental public entities.

8- The state of São Paulo has six metropolitan areas, RMSP being the largest in the state and in Brazil, and also the largest wealth concentration area in the country. Almost 50% of the state’s population live in this territory according to IBGE estimates for 2015. Available at: < https://www.emplasa.sp.gov.br/RMSP> , accessed on Sep. 2017 (Adapted text).

9- Available at: < http://pne.mec.gov.br/planos-de-educacao/situacao-dos-planos-de-educacao> . Accessed on: Jan 20, 2017.

10- Available at: < https://meumunicipio.org.br/indicadores> . Accessed on Feb. 04, 2018.

11- Data listed in the Table refer to Tax Revenues, starting with the municipality with the lowest percentage in relation to those Revenues.

12- Available at: < http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/educacao/2017/05/1885963-aposta-da-gestao-doria-creche-por-convenio-tem-qualidade-em-xeque.shtml> , accessed on April 11, 2017.

Received: April 13, 2018; Accepted: August 22, 2018

texto en

texto en