Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 10-Sep-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945197016

SECTION: ARTICLES

2- Federal Farroupilha, São Borja, RS, Brasil. Contato: carol.lacerda.ped@gmail.com.

3- Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, Brasil. Contato: lenirasepel@gmail.com.

This article reports an investigation on curriculum perceptions of a group of 65 educators working in a public school. The importance to understand the view of the educators on this topic is associated with the need to develop strategies for training and dialogue, which, based on the thought of the education actors, are useful to the discussions that involve curriculum changes. It is a field research conducted with an opinion questionnaire about statements related to the concept of curriculum. Results showed that the post-critical theories are more accepted and that critical theories were more rejected, although they were largely accepted under certain aspects. Traditional theories had the highest number of opinions classified as uncertainty or indifference, but are recognized as the organizing element of classroom practices. In the group, no educator revealed an exclusive agreement with the ideas of only one of the theories. It was found that the three curriculum conceptions guide the opinions of the investigated group. The simultaneous presence of ideas that reflect such different curriculum conceptions is interpreted as reflecting a period of ideological transformation in the educational field. Pondering and learning about curricular theories may help the educator to clarify the conceptions of curriculum that guide their pedagogical practice and to favor the critical participation in educational reforms.

Key words: Perceptions; Educators; School curriculum

Este artigo relata uma pesquisa sobre percepções de currículo de um grupo de 65 educadores atuando em escola pública. A importância de compreender a visão dos educadores sobre esse tema é associada à necessidade de desenvolvimento de estratégias para formação e diálogo que, baseadas no pensamento dos atores da educação, sejam úteis para as discussões que envolvem mudanças curriculares. Trata-se de uma pesquisa de campo realizada por meio de um questionário de opinião sobre afirmativas relacionadas ao conceito de currículo. Os resultados demonstram que as teorias pós-críticas têm mais aceitação e que as teorias críticas foram as mais rejeitadas, embora tenham, sob alguns aspectos, grande aceitação. As teorias tradicionais tiveram o maior número de opiniões classificadas como incerteza ou indiferença, mas são reconhecidas como o elemento organizador das práticas em sala de aula. Não houve no grupo um educador que manifestasse concordância exclusiva com apenas uma das teorias. Verificou-se que as três concepções de currículo balizam as opiniões do grupo investigado. A presença simultânea de ideias que refletem concepções de currículo tão diferentes é interpretada como reflexo de um período de transformação ideológica na área educacional. Refletir e aprender sobre as teorias curriculares pode ajudar o educador a ter maior clareza sobre as concepções de currículo que orientam sua prática pedagógica e favorecer a participação crítica nas reformas educacionais.

Palavras-Chave: Percepções; Educadores; Currículo escolar

Introduction

The proposal to investigate the educators’ conceptions about curriculum arises from the need to promote reflections on the topic in the school space, given the changes required by the new configuration of the Basic Education. Approval of the reforms in High School and the National Curriculum Common Core (NCCC) – mandatory national references for curricula and pedagogical proposals ( BRASIL, 2018 ) – demands urgent discussions in the educational field. Research into curriculum conceptions that are accepted and practiced in the school environment involves two contexts that can be convergent: one is associated with the transformations, ideologies, and dilemmas that emerge with the creation of the NCCC; the other context, older and with more developed analyzes, corresponds to the set of problems identified in education during the last decades, such as inadequate school programs, dropout, repetition, etc., which can be overcome with curricular reforms.

As they are instruments capable of establishing new educational models, curriculum reforms must be perceived by educators as valid, positive and executable, regardless of the agency that is promoting them. One of the necessary elements for the success of an educational reform is the harmony with the conceptions of the educators. Therefore, it is important to understand the views of this group about the school curriculum. By understanding the beliefs, values, ideologies and pedagogical theories that organize educators’ curriculum conceptions, it is possible to understand how their educational practices occur and how they may be affected by the reforms that are imposed on the national scene. Consequently, this research is related to the development of strategies for training and dialogue that consider the thinking of the teachers aiming at the necessary curriculum changes.

Thus, this study aims to identify the curriculum conceptions in the pedagogical thinking of educators working in Basic Education and to analyze the role of these conceptions in the current educational scenario. The concepts of what the curriculum is and what the functions of this structuring element are, as well as the opinions of how it should be organized and managed in schools, become the current teaching practices in the classroom. Understanding these conceptions is a way of creating ways to articulate the discussions and implementations that are presented in the reform scenario and also to organize activities of continuing education. In this study of the understanding of the curriculum, the designations and concepts proposed by Tomaz Tadeu da Silva (2013) were used. In the work entitled Identity documents: an introduction of the curriculum theories (in Portuguese, “Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo”).

The present paper describes the results of a field research following a qualitative approach, conducted with 65 educators from six public schools in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. In the first segment, the text organizes the theoretical framework about curriculum throughout the history of education, highlighting the main views that permeate the formation of educators. The second section of the text exposes the development and methodology of the research. Finally, the results and discussions are presented, followed by the final considerations of the study.

The theoretical path of curriculum conceptions

Traditional curriculum theories have ancient roots, but what is more present today relates to late 19th-century curriculum theories in the United States, represented by John Franklin Bobbitt, Ralph Tyler, and John Dewey. It was Bobbitt who inaugurated the beginning of curriculum studies with The curriculum in 1918, based on the conservatism and the business model. The first systematization of curriculum concepts and curriculum recommendations produced in the last century is described based on technicist ideals, on the search for the adaptation of individuals to the industrial order, and on the expectation of precision in the results ( BOBBITT, 2004 ).

The traditional teaching model, which stands out for its emphasis on learning content and objectives, was also highly influenced by Ralph Tyler’s work Basic principles of curriculum and instruction , published in 1949. Moreover, Tyler contributed to the ideals of curriculum organization and development that manifested clearly defined objectives and the division of curricular educational activity in two fields: teaching/instruction and assessment. Ralph Tyler’s thinking about school curriculum competed with that of John Franklin Bobbitt, who similarly proposed education along the lines of a company, which influenced curriculum organization in several countries, such as the United States and Brazil ( SILVA, 2013 ).

An alternative view represented by Franklin Bobbitt was developed concurrently in the early 20th century, which brought together progressive theoretical approaches driven by John Dewey’s conceptions. Such a view considered education in a more democratic way, and the principles of respect and tolerance were associated with the subject’s experiences, emphasizing the historical and social context in which education occurred ( CUNHA, 1994 ). In the view of traditional theories, the curriculum is an instrument used by the school to perform the mission of adjusting education to the needs and transformations of the economy of the beginning of the last century ( MOREIRA; SILVA, 2002 ).

Between the 1920s and 1930s, conceptions based on American capitalism influenced the technicist curriculum in Brazil. It was a time when the country was undergoing important social and economic transformations that culminated in educational reforms ( MOREIRA, 2001 ). The curriculum changes, inspired by John Dewey’s thinking, were carried out in Brazil by Anísio Teixeira and other educators who were committed to the reformulation of educational policies at the time.

The 1932 Manifesto entitled The educational reconstruction of Brazil: New Education Pioneers Manifesto (in Portuguese, “A reconstrução educacional do Brasil: Manifesto dos Pioneiros da Educação Nova”), presented the principles of the reform movement of the 1930s, notably the state’s commitment to public education and secularity of education. Due to the character of the proposals, the manifesto was associated with the term “New School” (in Portuguese, “Escola Nova”) ( PILETTI, 1997 ).

The Manifesto of the Pioneers was encouraged by international movements and advocated the creation of schools with a tendency towards an integral, active education and the exercise of autonomy. Although the New School Movement aimed to fight against the elitism in education and to break with the traditional curriculum, the curriculum proposals of this period were still characterized by the development of encyclopedic programs and rigid evaluations focused on numerical results ( ARANHA, 2006 ).

The technicist curriculum associated with the traditional school prevailed throughout the first half of the 20th century. It began to be questioned when educators, sociologists, and philosophers assumed that school should be considered as a means of expanding the human capacities, considering the subjectivities. In this context, from the 1960s, with strong criticism of the capitalist and elitist schools, movements emerged proposing changes in the traditional educational structure. In the United States, they were called reconceptualization movements , opposing the technicist and industrial base. This current had several representatives: in the United States, Michel Apple and Henry Giroux stood out; in England, under the influence of Michael Young, the philosophical presuppositions of the New Educational Sociology were organized; in France, Louis Althusser, Pierre Bourdieu, Jean Claude Passeron, Christian Baudelot, and Roger Establet develop analyzes of how the school is an ideological apparatus of the state; In Brazil, Paulo Freire is the most notable representative, who will defend educators’ awareness of their commitment to the liberation of the oppressed people through popular education proposals ( SILVA, 2013 ; MACEDO, 2013 ).

In the second half of the 20th century, the focus of thinkers who questioned the epistemological basis of the traditional theories shifted to questions about ideology, knowledge and power, issues that would need to be mainly discussed by the school, as highlighted by Moreira e Silva (2002 , p. 8, our translation):

The curriculum is implicated in power relationships; it conveys particular and interested social views; it produces specific individual and social identities. The curriculum is not a transcendent and timeless element – it has a history linked to specific and contingent forms of societal organization and education.

The new approach to curricula aimed to work in favor of oppressed groups and social classes, supporting the concern with the formation of critical thinking, not just teaching to read and write. The denunciation of social inequalities, racism, sexism and the search for a more democratic school that would become a space for the liberation of the oppressed classes became part of the teacher education. These questions served as a reference for the beginning of a new perception about school practices, the critical theories of the curriculum, which target changes in society, as expressed by Apple (2002 , p. 54; APPLE, 2004, p. xxvi-xxvii):

This advance requires that the system of meanings and values that this society has generated – one increasingly dominated by an “ethic’ of privatization, unconnected individualism, greed, and profit – has to be challenged in a variety of ways. Among the most important is by sustained and detailed intellectual and educational work.

The movements associated with critical theories aimed to give a voice to the student, incorporating the daily experiences into the curriculum content, bringing to the classroom the proposal of thinking about current problems, in which debates, solutions, and discussions were based on the interests of the people ( FREIRE, 1991 ). In this regard, Giroux and Simon (2002) point to the need for reflections on school curriculum that address social injustices and everyday experiences, as educators cannot only abide by dominant discourses. This question is also claimed in Freire’s view (2006). For the author, education needs to free, to make the subjects critical, so that they can build themselves as people, and not to domesticate.

Moreover, Freire (1991) argues that the teaching and learning process needs to be reformulated to meet popular culture while incorporating the experiences and different knowledge of minority groups in the school curriculum. This critical logic is also highlighted by Silva (2013) when states that the culture of silence should not be accepted and that the school needs to practice a critical pedagogy that denounces situations that devalue life.

For Silva (2013) , the most complex part of critical theories includes the analysis of implicit aspects that legitimize learning, the so-called hidden curriculum described by Apple (1982 /2004) in Ideology and curriculum . The manifestation of this hidden part depends on situations in which attitudes, behaviors, values, and orientations are learned in keeping with the conveniences of the dominant social structures, in line with the conveniences of the dominant social structures. In this regard, the role of the critical conception of the curriculum is to unhide what is hidden, to make explicit what is implicit.

When analyzing the current trends in curriculum discourses, Macedo (2013) mentions new questions posed by the social sciences and cultural studies that contribute to the construction of the thinking of post-critical curriculum theories. Rodrigues and Abramowicz (2013) point out that the 1990s were considered a reference for the elaboration of these theories, as it was marked by claims and social movements against the various forms of discrimination, which contributed to increase the educational discussions about culture and diversity and fostered the multiculturalism, the latter being considered by Moreira and Candau (2008) as a culture crossing.

In Brazil, this vision spread with the work of Tomaz Tadeu da Silva and other publications related to post-modern and post-structural matrices. Professor and researcher Antônio Flávio Moreira also played a key role in the process of disseminating post-critical theories to the school curriculum, as it presented the perception of crisis of the critical theories, which subsequently contributed to the post-critical thinking ( MACEDO, 2013 ).

Regarding the post-critical theories of curriculum, Silva (2013) stresses the importance of different cultural forms in this matrix of thought, as there is an opposition to the ideological structures that favor dominant traditional cultures. Such theories are concerned with topics such as class, gender, race and sexuality privileges, as well as inequalities and power relationships. They promote the integration of sociological and pedagogical aspects of the school curriculum, arguing that it is essential to consider the political, social, economic and cultural contexts in the educational process.

Therefore, a curriculum inspired by this conception would not be limited to teaching tolerance and respect, however desirable it may seem, but would instead insist on an analysis of the processes by which differences are produced through asymmetry and inequality relationships ( SILVA, 2013 , p. 88, our translation).

In the book entitled Identity documents: an introduction to the curriculum theories (in Portuguese, “Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo”), Silva (2013) presents post-critical theories as a broadening of the understanding of domination processes through problematization and questioning that leads to seeing beyond the traditional aspects. In this type of curriculum, the differences, besides being tolerated and respected, are problematized and put permanently in question.

The classification of curriculum theories adopted in this article is based on the organization of Tomaz da Silva, since it is believed that the structuring proposed by the author organizes the complexity surrounding the theoretical currents on curriculum and allows to analyze the theories comparatively, taking into account the expectations for the role of the school, educators, and students ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 – The different roles of social actors according to the theoretical currents on the curriculum proposed by Tomaz da Silva

Source: The authors.

Curriculum theories show the diversity of conceptions in pedagogical theories in recent times. The aspects highlighted in Table 1 summarize how the way the school curriculum is perceived has changed and destabilized the view of a static content curriculum.

Methodology

Research instrument

Data were collected through a questionnaire with open and closed questions. Each questionnaire was followed by a text presenting the research objectives and the research proponents, along with guarantees of anonymity for all participants and non-identification of the institutions. In the informed consent form signed by the participants, it was explicitly stated that the activity was totally voluntary and that at any time it was possible to give up answering the questions by simply returning the questionnaire along with the others.

The first part of the questionnaire was designed to build the profile of the educator, collecting information on gender, age, school performance, academic education and participation in continuing education activities. The second part consisted of nine statements about curriculum expressing ideas that represent different theories in simple language and directly.

In the questionnaire, the statements were presented in a random sequence and were not organized into groups, as shown in Table 2 . For each of them, the participant should choose the alternative that best represented his/her opinion: completely agree; agree; slightly agree; neither agree nor disagree; disagree; slightly disagree, and completely disagree.

Table 2 – Curriculum statements presented to the participants and organized according to the theories they represent

| Curriculum Theories | Statements |

|---|---|

| Traditional theories | 1. A curriculum is the organization of the contents to be transmitted to the students by the teachers. |

| 2. A curriculum is the school subjects to be taken by the students, with the sequenced activity programs and the learning outcomes intended. | |

| 3. A curriculum is the set of procedures, methods, and techniques that take place specifically in the school environment. | |

| Critical theories | 1. A curriculum is a political instrument that is linked to the ideology , the social structure, the culture , the power , and the interests of the ruling classes. |

| 2. A curriculum is an instrument that contributes to the maintenance of social inequality . | |

| 3. A curriculum reflects a view of the world , society, and education. | |

| 4. A curriculum is the set of procedures, methods, and techniques that organize the contents necessary for a critical and emancipatory formation . | |

| Post-Critical Theories | 1. A curriculum is a cultural construction that makes it possible to organize educational practices. |

| 2. A curriculum is the set of practices that contribute to the construction of social and cultural identities . |

Source: The authors.

Data analysis

It was previously established that only questionnaires with all questions answered would be part of the sample. Curriculum opinions were grouped into three classes or adherence levels, which were named as acceptance, uncertainty, and rejection ( Table 3 ) whose frequencies were expressed as percentages.

Participants in the research

The research participants were 65 educators, trained in different areas of knowledge and working in the classroom and/or school management with administrative and pedagogical activities in public schools in two municipalities (Santiago and Santa Maria) of the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Results and discussion

The answers from the first part of the questionnaires (personal data) allow describing the following profile as predominant in the research subjects: women (87%); between 30 and 40 years old (32%); with a specialization degree (71%); working exclusively in elementary school of the public municipal network (87%); with a workload of 40 hours per week (48%); at the beginning of their professional career, with an experience between 4 and 10 years (29%).

In the analysis of the answers, any kind of grouping of opinions determined by gender, age group, education, type of activity in school or time working in the teaching profession, municipality or school was detected. From this result, the sample was considered as a single group.

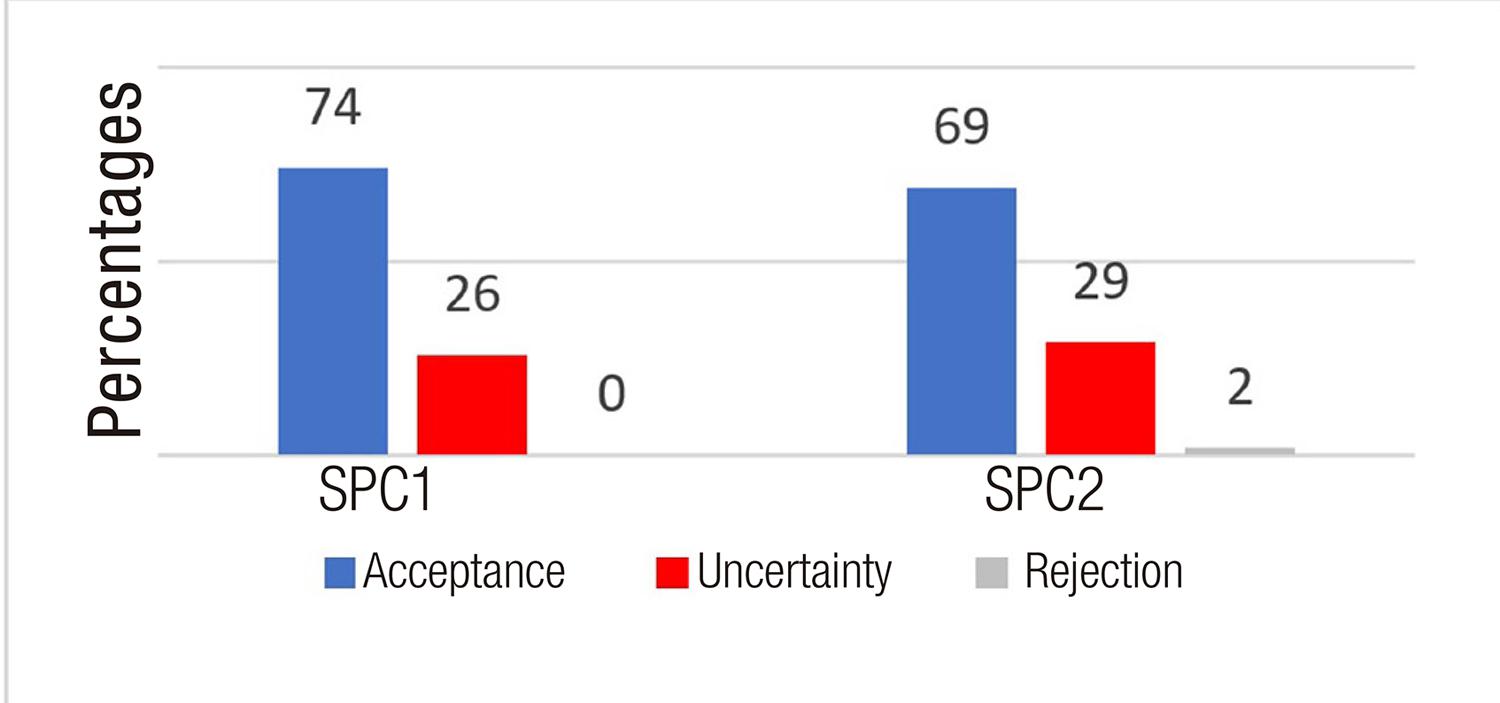

The frequencies of acceptance, uncertainty, and rejection in the statements that represented the ideas of the post-critical theories are presented in Figure 1 .

Source: Research data.

Figure 1 – Percentage of acceptance, uncertainty, and rejection regarding the statements related to post-critical theoriesSPC: Statement post-critical theories; SPC1: A curriculum is a cultural construction that makes it possible to organize educational practices; SPC2: A curriculum is the set of practices that contribute to the construction of social and cultural identities.

The results show that the two statements that represent post-critical theories have similar acceptance and uncertainty frequencies and low rejection, especially for the statement that defines curriculum as a cultural construction. When gathered together, this can be interpreted as a very favorable willing of educators to ideas linked to post-critical theories.

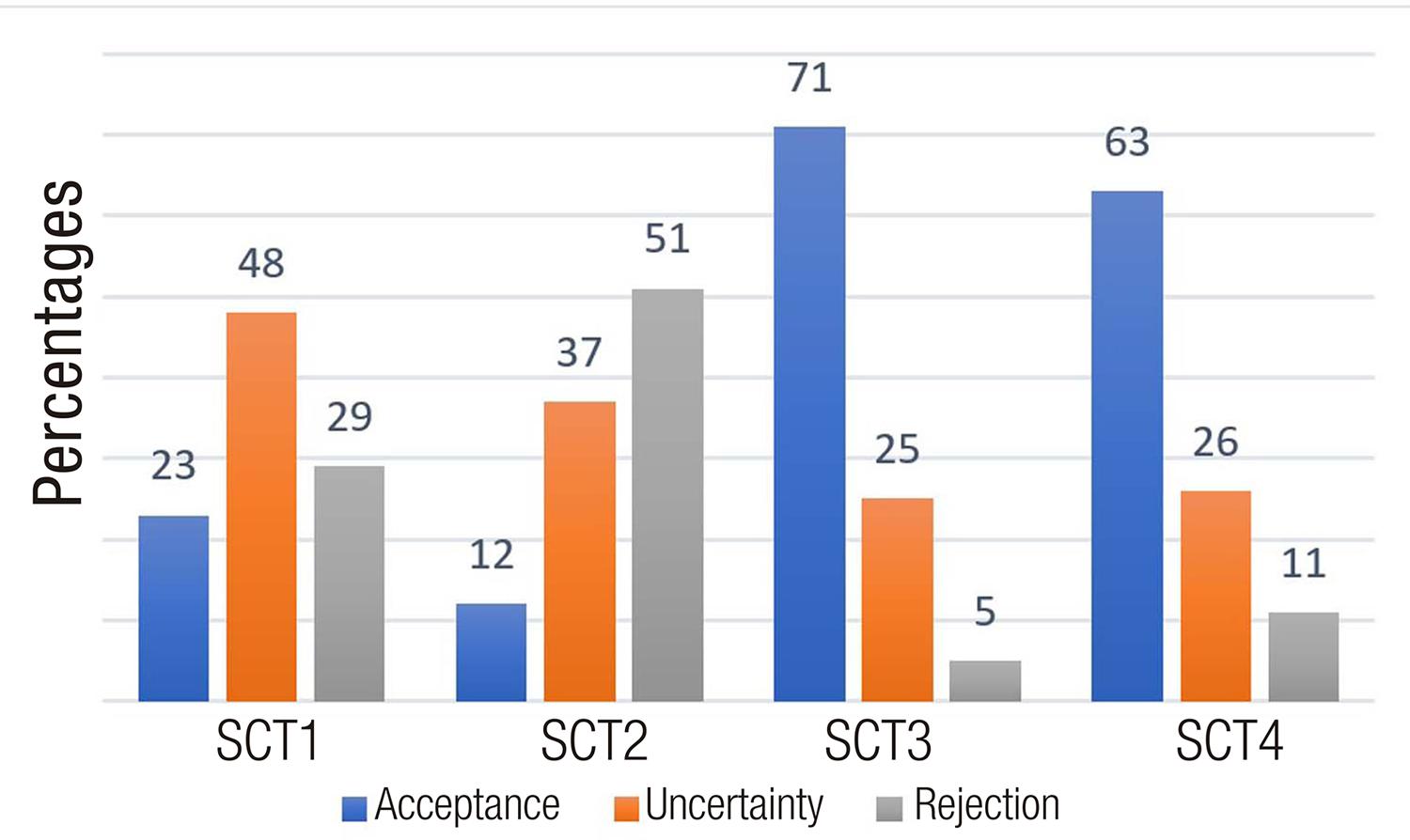

For the statements that represented the curriculum conception disseminated by critical theories, the results were more complex. The statements that relate the curriculum to the ideological interests of the ruling classes and the maintenance of social inequalities were the least accepted ( Figure 2 ). It is noteworthy that the statement “A curriculum is an instrument that contributes to the maintenance of social inequality” obtained the lowest acceptance rate in this research and the highest rejection rate (12% and 51%, respectively). From this set of responses, it is evident that educators do not accept that the school can collaborate in any way to promote or maintain social inequality. In theoretical terms, it can be understood that the concept of a hidden curriculum ( APPLE, 1982 ) is not part of the education of these educators or is formally rejected.

Source: Research data.

Figure 2 – Percentage of acceptance, uncertainty, and rejection regarding the statements related to critical theoriesSCT: Statements critical theories; SCT1: A curriculum is a political instrument that is linked to the ideology, the social structure, the culture, the power, and the interests of the ruling classes; SCT2: A curriculum is an instrument that contributes to the maintenance of social inequality; SCT3: A curriculum reflects a view of the world, society, and education; SCT4: A curriculum is the set of procedures, methods, and techniques that organize the contents necessary for a critical and emancipatory formation.

The other two statements that represent critical theories include curriculum ideas reflecting their world view and associated with a critical and emancipatory formation. Together they consisted of a tendency opposite to the previous statements: they are the most accepted, the least rejected and with the least frequency of uncertainty. The most expressive results involve the statement in which the expression “critical and emancipatory formation” appears, which in itself may have triggered its wide acceptance. The association of these terms refers directly to the works of Paulo Freire, who is undoubtedly the most valued thinker and whose ideas are the most widespread in Brazilian teacher education.

By identifying key terms or clichés often used in a simplified way to refer to Paulo Freire’s ideas, the research subjects tend to agree. This can be explained by the great acceptance of Paulo Freire’s theories ( STRECK, 2014 ); the simple evocation of this thinker’s name and his ideas make legitimate the educational practices associated with them.

It is important to stress that there is no formation of opinion groups for or against the ideas of critical theories. Most of the research subjects reject some elements of critical theories while being very supportive of other ideas typical of those theories. Several questions emerge from these results. The simultaneity of acceptance/rejection can be considered as a naive manifestation about the role of the teacher, the school, and the curriculum as agents for the critical and emancipatory formation.

The lack of more structured knowledge about curriculum theories and the little tradition of discussions in the school environment about curriculum dimensions and manifestations may be the reasons for the school’s rejection of contributing to the maintenance of social inequality through the curriculum. According to McLaren’s (1997) view, this situation can be understood as a difficulty of the group in perceiving the context as linked by practices of domination.

Given this data, there is a need for greater investments in the professional development of educators, whether they are initial or continuing, aiming to deepen the analysis of basic topics in education. Giroux (1997) mentions that, in order to teach critically, the educator needs to be critical and understand the ideological forces that are responsible for the dominant interests and inequality, or, as Freire (1979) pointed out, the educator needs to evolve from a naive consciousness to critical awareness.

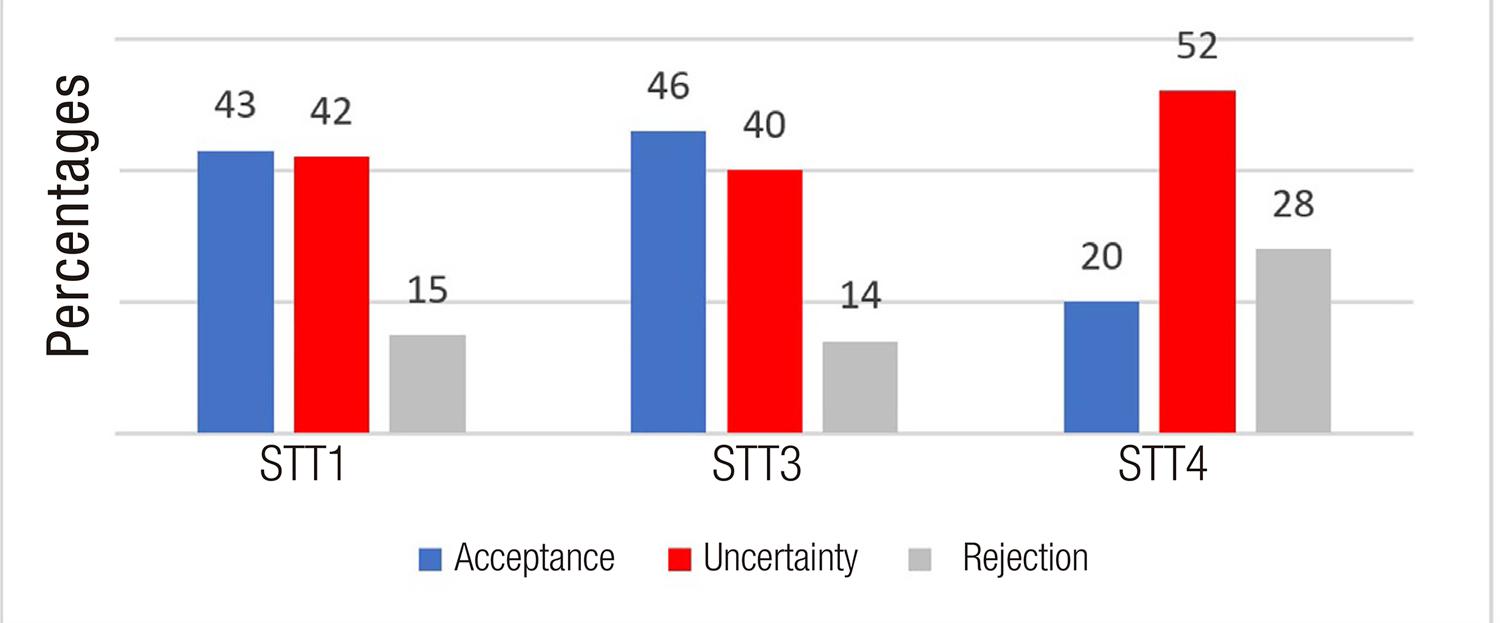

Regarding the first two statements that represented the traditional theories, very similar results were achieved for acceptance and uncertainty, with a low percentage of rejection of curriculum ideas considering content transmitted to students by teachers and subjects to be taken, with the activity programs and the intended results ( Figure 3 ).

Source: Research data.

Figure 3 – Percentage of acceptance, uncertainty, and rejection regarding the statements related to traditional theoriesSTT: Statements Traditional theories; STT1: A curriculum is the organization of the contents to be transmitted to the students by the teachers; STT2: A curriculum is the school subjects to be taken by students, with the sequenced activity programs and the learning outcomes intended; STT3: A curriculum is the set of procedures, methods, and techniques that take place specifically in the school environment.

The third statement that represented the traditional theories ( Figure 3 ) was among the most rejected in the research and was the one that caused the most uncertainty. Evidently, educators conceive curriculum as going beyond the school boundaries. There is a broader understanding of curricular practices, as situations and spaces not directly related to school are considered as educational possibilities.

The rejection of the definition of curriculum as something that occurs specifically in the school space shows that the social and cultural environment is part of the curricular thinking of this group, reassuring the consistency of acceptance of the statements that represent post-critical theories. In this regard, according to the perspective developed by Arroyo (2007) , educators would already be practicing a new logic in the structure of knowledge, by organizing what will be taught based on values, diversity, identities, classes, ethnicities, and genders.

The frequency of responses to statements having the expressions “content to be transmitted” and “school subjects to be taken” are in agreement with the results of the research conducted by Felício and Magalhães (2016) , which also identified a significant percentage of approvals (53%) for the curriculum described as goals, assessments, textbook, lessons. The very traditional perception of curriculum coexists with a high acceptance of some ideas from critical and post-critical theories. Arroyo (2007) points out that teachers are influenced by the market logic and dominated by the perspective of reaching competences, believing in the linear and segmented curriculum and that this influence compromises their role as social author and transformer.

The expressive presence of agreement and uncertainty about such traditional curriculum understandings deserves attention, as it is necessary to reflect on what validates these conceptions in school practice at different levels. The extent to which out-of-school assessments (whether the assessments in which the country needs to show a good performance or large-scale national assessments) modulate the curriculum conceptions is still an issue not conclusively approached. Bureaucratization in the organization and management of the school system should also be considered as influencing the maintenance of traditional conceptions. In this case, the curriculum would be just another form to be filled out and filed having a smaller dimension in the teachers’ activities.

In the search for explanations for the coexistence of conceptions about curriculum that derive from conflicting theories, initial teacher education cannot be ignored. Can the mismatch between the theories to which the teacher is exposed during graduation and the actions and decisions that will be carried out in the classroom professional activity distance the professionals from the discussions about curriculum, making this subject invisible within the school? If pragmatism, fueled by the immediate needs of classroom management, can encourage the teacher to take a traditional stance, what is the role of presenting the discussions of curriculum theories that take place in early education? And perhaps the most worrying question: What is the reception of educators in the face of continuing education involving curriculum and the necessary discussions in view of the changes that must be made in the short term in Basic Education to comply with the new legislation? These issues are complex and require a research and interpretation effort to better understand the origin, maintenance, and consequences of this mix of curriculum conceptions.

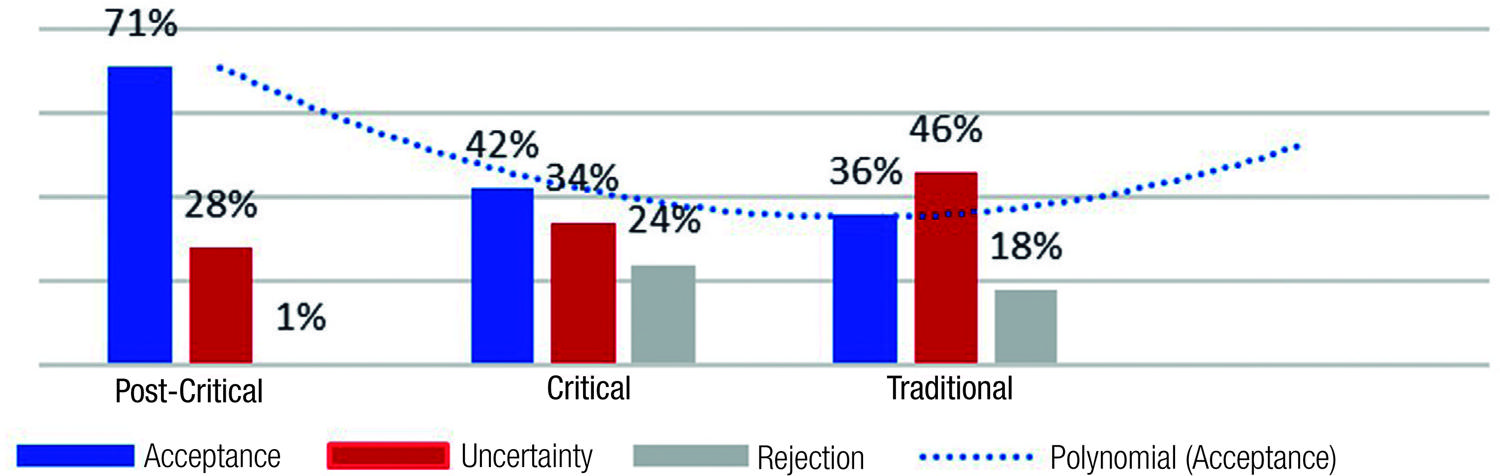

The analysis of the statements representing each of the theories ( Figure 4 ) shows the greater acceptance of post-critical theories. Critical and traditional theories are close in the results, but the former has a higher rejection level and the latter has the highest outcome for uncertainty.

Source: Research data.

Figure 4 – 65 educators’ opinion about curriculum regarding the acceptance of, uncertainty of, and rejection to the set of statements that represent the three categories of curriculum theories: post-critical, critical, and traditional

The wide acceptance of post-critical conceptions indicates that there is a break with the static view of education. According to Macedo (2006) , it can be interpreted that this group of educators considers it valid to think of the curriculum as a space-time of knowledge and culture. The high frequency of acceptance of ideas that represent post-critical theories can be considered, as proposed by Silva (2013) , a sign of new understandings, as a favorable disposition to recognize multiculturalism as an instrument of struggle and equality. The result of the acceptance of post-critical theory also allows associations with consolidating social movements, the valorization of struggles for overcoming differences, as well as the dissemination of this thinking in textbooks, pedagogical materials, and teacher training courses, as pointed out by Gomes (2007) .

The result of uncertainty linked to the traditional theories (46%), however, has no simple explanation. The fact that most subjects cannot definitively position themselves against or in favor of this theory involves several possibilities. The clear identification of the premises of traditional theories and the theoretical notion that this should be an outdated perspective in education may have inhibited the answers of acceptance. The conflict between theory and classroom practices would also have stimulated the position of being neither against nor in favor of it. In the worst-case scenario, educators know the discourses of critical and post-critical theories, recognize these ideas as models validated by the intellectual community, but practice traditional theories in everyday life. Alternatively, the vagueness and maintenance of eclectic curriculum opinions, including components of all theories, may be viewed as attempts to adjust valid discourses to the needs of school and classroom management, which demand objectives, goals, content organization in the perception of the educators, in addition to social knowledge. Given this context, it is believed that the dilemma evidenced by the educators can be posed in terms of a search for balance: without prioritizing technical issues over social issues and vice versa.

Another analysis on the uncertainty responses relates to the conception of hybridism that addresses the articulation of different discourses within reality, a combination of different traditions, experiences and disciplinary movements ( MATOS; PAIVA, 2007 ). These issues are also addressed by the Brazilian researchers in the area of curriculum Lopes and Macedo (2006) , who perceive the curriculum as a hybrid place since it is always being defined according to the existing cultures.

The answers to the statements were also analyzed from the point of view of each individual. The results show the simultaneous acceptance of more than one theory for the entire investigated population. No participant in the sample had full acceptance of one set of ideas and rejection of the other statements. It was observed that 58% of participants who fully agreed or agreed with the statements of traditional theories agreed with at least one statement of critical and post-critical theories. In the same manner, 57% of the participants expressing acceptance for both statements of post-critical theories were also in favor of more than one statement of critical and traditional theories.

Thus, the analysis of responses per individual made it clear that it is not possible to describe participants according to an extremely supportive profile of post-critical, critical or traditional theories. The various combinations of acceptance and rejection responses revealed that there are no ideological associations between the choices, even between critical and post-critical theories, and that favorable responses to traditional theories are present in all questionnaires. This data set is close to the idea of discourse hybridization, as suggested by Lopes (2008) .

Sacristán (2003) approaches the multiplicity of curricular conceptions as a game of interests, in which beliefs, skills, values, and attitudes are articulated with the school knowledge.

[The] teachers’ conceptions of education, the value of content and processes or skills proposed by the curriculum, the perception of students’ needs, working conditions, etc. will undoubtedly lead them to interpret the curriculum personally. ( SACRISTÁN, 2003 , p. 172, our translation).

This makes the teaching and learning process marked by different knowledge and experiences, allowing the educator to adopt different curriculum theories.

The complexity of the curriculum conceptions scenario in schools needs to be considered and better understood, given the need for curriculum changes that emerge due to reforms in legislation and public policies associated with the advent of the Common National Curriculum Core. Without changes in the curriculum-related conceptual profile, the maintenance of some conceptions can strongly interfere with both the interpretation and application of educational changes, whether determined by public policies, such as the NCCC or derived from proposals based on the recognition that the classroom reality is distanced from the everyday context.

The data indicate that there is still a long way in search of the transformation of curricular conceptions. According to Roldão (1999) , it is necessary to keep in mind that the lessons, the workloads, the methodologies, the topics, and the evaluations are pieces of the curriculum, but the curriculum itself cannot be reduced to these components. According to Moreira and Candau (2008) , the awareness of the homogenizing and monocultural character of the school should be increasingly strong, as well as the awareness of the need to break with this standardizing tendency and to build educational practices in which difference and multiculturalism are present.

Thus, the possibility of bringing the curriculum closer to what is necessary for good human development in the current context requires changes in the teaching conceptions and practices. One of the solutions pointed out for these changes to occur is a new model for teacher education that, according to Nóvoa (2009) , values the practical component, the professional culture, the personal dimensions, the collective logic, and the effective social participation of teachers.

Conclusions and final considerations

The collective of teachers investigated believes in the post-critical view of curriculum, which involves a new teacher identity redefined by the multiculturalism, associated with the social and identity movements; that is, it is a group of educators who believe in the need to break with homogenizing and discriminatory practices, as well as in strengthening an education in which differences are more present.

This same group of educators accepts themselves as participating in critical education, but does not recognize the role of the school as a reproducer of inequalities. This set of ideas warns of the need for further reflection on the initial teacher education, as well as the incorporation of a critical awareness of dominant interests and the curriculum as an instrument of empowerment. The result also shows that it is necessary to advance the continuous education about the school curriculum, emphasizing the critical knowledge of the curricular policies with which teachers deal in their daily life.

Although agreeing with the post-critical theories, the group have as main reference the traditional theories. Even with more frequent uncertainty among educators, the answers lead us to realize that classroom practices are organized following the traditional conception, with priority to the prescribed contents.

Given this set of results, it can be said that there is not an only one conception of curriculum that base the educator’s thinking, which is understood as a hybridism related to the views on the school curriculum in a period of educational ideological transformation.

The current moment is conducive to pondering the curriculum and curriculum thinking of education professionals. The approval of the National Common Curriculum Core triggers a profound change in schools and creates unique situations in the Brazilian educational scenario. New investigations and follow-up of the NCCC implementation trajectories in schools, as well as the debate about the new curricular methodologies in progress, are urgent. Understanding what educators think about curriculum and how these conceptions can influence the implementation of reforms is still a challenge. It would not be desirable for changes to be practiced without a critical and analytical view from the participants about their curriculum thinking and their intentions of change, whatever they may be.

Based on this scenario, the importance of teacher qualification is defended, because it allows expanding knowledge to critically understand the new education proposals. However, the qualification should start from reality and the needs of the school and the educators. It should help educators to be clearer about the curriculum conceptions that guide their pedagogical practice and that can significantly influence their role in the educational reforms.

REFERENCES

APPLE, Michael W. Ideologia e currículo. São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1982. [ Links ]

APPLE, Michael W. Repensando ideologia e currículo. In: MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B.; SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Currículo, cultura e sociedade . Trad. Maria Aparecida Baptista. 7. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. p. 49-70. [ Links ]

ARANHA, Maria Lúcia. História da educação e da pedagogia: geral e Brasil. São Paulo: Moderna, 2006. [ Links ]

ARROYO, Miguel González. Indagações sobre currículo: educandos e educadores: seus direitos e o currículo. Organização do documento: Jeanete Beauchamp, Sandra Denise Pagel, Aricélia Ribeiro do Nascimento. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica, 2007. Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/Ensfund/indag2.pdf> . Acesso em: 09 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

BOBBITT, John Franklin. O currículo. Porto: Didáctica, 2004. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular . Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018. Disponível em: < http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_EI_EF_110518_versaofinal_site.pdf> . Acesso em: 26 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Marcus Vinicius da. John Dewey: uma filosofia para educadores em sala de aula. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1994. [ Links ]

FELÍCIO, Helena M. dos Santos; MAGALHÃES, Amanda Chiaradia. A concepção dos professores dos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental a respeito de currículo escolar. Educação em Revista , Marília, v. 17, n. 2, p. 59-72, jul./dez. 2016. Disponível em: < http://www2.marilia.unesp.br/revistas/index.php/educacaoemrevista/article/viewFile/6237/4113> . Acesso em: 25 maio 2017. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. A educação na cidade . São Paulo: Cortez, 1991. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Educação e mudança . 30. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1979. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da esperança . 13. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2006. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. Os professores como intelectuais: rumo a uma pedagogia crítica da aprendizagem. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry; SIMON, Roger. Cultura popular e pedagogia crítica: a vida cotidiana como base para o conhecimento curricular. In: MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B.; SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Currículo, cultura e sociedade . Trad. Maria Aparecida Baptista. 7. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. p. 93-124. [ Links ]

GOMES, Nilma Lino. Indagações sobre currículo: diversidade e currículo. Organização do documento: Jeanete Beauchamp, Sandra Denise Pagel, Aricélia Ribeiro do Nascimento. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica, 2007. Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/Ensfund/indag4.pdf> . Acesso em: 09 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

LOPES, Alice Ribeiro Casimiro. Políticas de integração curricular. Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj, 2008. [ Links ]

LOPES, Alice Ribeiro Casimiro; MACEDO, Elizabeth (Org.). Políticas de currículo em múltiplos contextos. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. A noção de crise e a legitimação de discursos curriculares. Currículo sem Fronteiras , v. 13, n. 3, p. 436-450, set./dez. 2013. Disponível em: < http://www.curriculosemfronteiras.org/vol13iss3articles/emacedo.pdf> . Acesso em: 25 maio 2017. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Currículo como espaço-tempo de fronteira cultural. Revista Brasileira de Educação , Rio de Janeiro, v. 11, n. 32, p. 285-296, maio/ago. 2006. Disponível em: < http://stoa.usp.br/gepespp/files/3114/17448/Curriculo+como+espa%C3%A7o-tempo+de+fornteira+cultural.pdf> . Acesso em: 25 maio 2017. [ Links ]

MATOS, Maria do Carmo de; PAIVA, Edil Vasconcellos de. Hibridismo e currículo: ambivalências e possibilidades. Currículo sem Fronteiras , v. 7, n. 2, p. 185-201, jul./dez. 2007. Disponível em: < http://www.curriculosemfronteiras.org/vol7iss2articles/matos-paiva.pdf> . Acesso em: 14 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

MCLAREN, Peter. A vida nas escolas: uma introdução à pedagogia crítica nos fundamentos da educação. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B. A recente produção cientifica sobre currículo e multiculturalismo no Brasil (1995-2000): avanços, desafios e tensões. Revista Brasileira de Educação , Rio de Janeiro, n. 18, p. 65-81, set./dez. 2001. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B.; CANDAU, Vera Maria. Multiculturalismo: diferenças, culturas e práticas pedagógicas. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2008. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B.; SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Currículo, cultura e sociedade. 7. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, António Para uma formação de professores construída dentro da profissão. Revista Educación , Madrid, n. 350, set./dez. 2009. Disponível em < http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re350/re350_09.pdf> . Acesso em: 22 abr. 2017. [ Links ]

PILETTI, Claudino. Filosofia da educação . 7. ed. São Paulo: Ática, 1997. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Tatiane Cosentino; ABRAMOWICZ, Anete. O debate contemporâneo sobre a diversidade e a diferença nas políticas e pesquisas em educação. Educação e Pesquisa , São Paulo, v. 39, n. 1, p. 15-30, jan./mar. 2013. [ Links ]

ROLDÃO, Maria do Céu. Gestão curricular: fundamentos e práticas. Lisboa: ME-DEB, 1999. Disponível em: < http://www.ipb.pt/~mabel/documdisciplinas/gestaocurricu.pdf> . Acesso em: 12 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, José. O significado e a função da educação na sociedade e na cultura globalizada. In: GARCIA, Regina Leite; MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio B. (Org.). Currículo na contemporaneidade: incertezas e desafios. São Paulo: Cortez, 2003. p. 41-80. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2013. [ Links ]

STRECK, Danilo. Ecos de Angicos: temas freireanos e a pedagogia atual. ProPosições , Campinas, v. 25, n. 3 (75), p. 83-101, 2014. Disponível em: < http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pp/v25n3/v25n3a05.pdf> . Acesso em: 18 set. 2017. [ Links ]

Received: April 30, 2018; Revised: June 13, 2018; Accepted: August 08, 2018

texto en

texto en