Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.45 São Paulo 2019 Epub 29-Oct-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945201975

SECTION: ARTICLES

Assessment of the competency profile of the head of pedagogy in Chilean educational centers in vulnerable contexts1 *

2- Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. Barcelona, España. Contactos: contacto@danielvillarroel.cl; joaquin.gairin@uab.es.

3- Universidad de Atacama, Copayapu, Chile. Contacto: jose.garces@uda.cl.

This study focuses on the professional competency profile of the head of pedagogy in Chilean schools in vulnerable contexts, identifying its specific competencies associated with domains of fundamental competencies, contextualized within these type of centers and according to the profile that the employer sees fit. This is a qualitative research study of a single case that employs mixed methodology and ethnographic design—including the analysis of three official documents from the Pedagogical Management Committee—a focus group consisting of sostenedores—as well as three questionnaires answered by experts on the topic, and five working sessions with the aforementioned Committee. The results identify four domains: a) pedagogical leadership, referring to guiding and promoting teaching/learning processes for teachers; b) pedagogical-administrative support, as pertaining to coordinating, monitoring, and supporting teachers; c) curricular management of learning processes, as pertaining to monitoring school processes; and d) innovation project management, meaning directing and organizing innovation projects proposed by teachers. The study provides the identification of sixteen professional competencies pertaining to four domains applicable to vulnerable contexts, which were validated by higher education experts and sostenedores. The final profile is rated very high and high by the management entities that participated as a pilot sample during the application of the profile model.

Key words: Head of pedagogy; Subsidized education; Vulnerability

La investigación se centra en el perfil de competencias profesionales del jefe pedagógico en centros escolares chilenos situados en contextos vulnerables, identificando sus competencias específicas asociadas a dominios de competencia esenciales, contextualizado a este tipo de centros y según el perfil que considera el empleador. Se trata de una investigación cualitativa de caso único, con metodología mixta y diseño etnográfico, incluyendo el análisis de tres documentos oficiales por el Comité de Jefatura Pedagógica, un grupo focal con sostenedores, así como tres cuestionarios a expertos en el tema y cinco reuniones de trabajo con dicho Comité. Los resultados identifican cuatro dominios: a) Liderazgo pedagógico, referido a guiar e impulsar procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje de los docentes; b) Acompañamiento pedagógico–administrativo, que se relaciona con coordinar, monitorear y apoyar a los profesores; c) la Gestión curricular de los aprendizajes, que guarda relación con monitorear los procesos escolares; y d) la Gestión de proyectos de innovación, asociada a dirigir y organizar proyectos de innovación propuestos por los profesores. El estudio aporta la identificación de dieciséis competencias profesionales según cuatro dominios aplicables a contextos vulnerables, que fueron sometidas a validación por sostenedores y expertos de Educación Superior. El perfil final elaborado es calificado de Muy Alto y Alto por los estamentos directivos que participaron como muestra piloto durante su aplicación.

Palabras-clave: Jefe pedagógico; Educación subvencionada; Vulnerabilidad

Contextualizing the problem

Twenty-first century society has delved into a never-ending process of reassessing education and, more specifically, the government and management of educational centers. It is currently considered a given that, among the internal factors in a school, and after the teacher’s work in the classroom, leadership is the second-most influential factor for learning (HALLINGER; WANG, 2015; DAY et al., 2010; ROBINSON; HOHEPA; LLOYD, 2009; ROBINSON; LLOYD; ROWE, 2008).

In many studies, the head of pedagogy consists of the technical manager of the pedagogical-curricular area, with interventions that include:

[…] Ensuring the existence of useful information for decision-making, managing the resources available to the establishment (both material and human), supervising and supporting the teachers’ work, ensuring the implementation of pedagogical methodologies and practices in the classroom , tracking curricular processes, etc. (CARBONE et al., 2008, p. 17).

This professional must practice leadership aimed at promoting the professional development of teachers as well as students’ learning, working against a single type of administrative and control logic (MANSILLA; TAPIA; BECERRA, 2012). Through leadership roles distributed among other members of the management team, this figure also shares responsibilities related to improving student learning through better processes of school organization.

In this regard, Montecinos, Aravena and Tagle suggest that in networks dedicated to school improvement, both directors and heads of the Technical Pedagogical Unit (UTP in Spanish) are involved where this “[…] management pair could better involve their communities in developing the network’s projects. In turn, according to his or her role, each actor can contribute to the network in a unique way” (2016, p. 62).

Given this panorama, several studies stand out in the international field, such as those of Pont, Nusche, and Moorman (2008); Gairín and Castro (2012) and Villa (2013), among others, that examine the management processes focused on curricular improvement.

We can also find research contributions that specifically focus on the problems facing Chilean high schools that exist within vulnerable contexts (MANSILLA; TAPIA; BECERRA, 2012) as well as on the problems that technical unit heads must navigate in terms of pedagogical management (BELTRÁN, 2014). Likewise, we can identify studies conducted by Fundación Chile that focus on management competency profiles (CEPPE, 2006) and a proposal to evaluate the management team’s performance (AHUMADA; MONTECINOS; SISTO, 2008).

Nevertheless, the contributions that we have indicated, although relevant, do not illustrate the particular traits that the interventions of the Chilean Heads of Technical Units (heads of study or academic managers in other contexts) should possess when we take into consideration the reality of schools that serve significant percentages of students in vulnerable situations.

To this effect, we Gairín and Suárez’s study (2013) delineates the link between serving vulnerable groups with social justice and the need to create specific models of intervention based on the following components: philosophy of action, methodology for intervention, and specific strategies for transformative action.

Faced with this panorama, Morduchowicz, Aylwin and Wolff point out that “[…] the Ministries have a complex and vertical structure. The belief is that those above give orders and those below obey” (2008, p. 20); this structure tends to generalize normative and operational processes and disregard the contextualization needed when focusing on vulnerable groups.

There is therefore a knowledge gap and a need to generate research contributions on the profile of the head of pedagogy in Chile in the context of private subsidized vulnerable schools, while taking into consideration the following questions: Is there a specific profile for the head of pedagogy in the Chilean subsidized private sector in vulnerable contexts? What profile does the sostenedor consider when hiring this professional?

The need to examine this reality at greater depth is also justified by the discovery of certain particularities in the activity of management teams (VILLARROEL; GAIRÍN; BUSTAMANTE, 2014).

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to define the competency profile of the head of pedagogy in vulnerable subsidized educational centers. The study also considers the following specific secondary objectives:

To perform a technical documentary analysis of the head of pedagogy role on an international and national level, as applicable to the subsidized school subsystem.

To prepare a proposal of the competency profile of the head of pedagogy in the subsystem of private subsidized schools in vulnerable contexts.

To identify the prevailing opinions of the sostenedores4 on the head of pedagogy profile in vulnerable subsidized centers.

To validate the proposals of the elaborated profile.

To rate the level of achievement of the head of pedagogy’s competency profile in vulnerable contexts.

Contextual and theoretical framework

In this section, we explore the main concepts related to the role of the head of pedagogy and his or her interventions in the realities of school vulnerability.

The head of pedagogy and his or her competencies

Carbone et al. suggest that the head of pedagogy focuses on the “[…] monitoring of learning outcomes, the management of pedagogical interventions, and other actions associated with the technical field. This is complemented by innovations in curricular material, whether at the level of methodologies, content or other” (2008, p. 18). In addition to this description, there are other pedagogical practices such as supervising and giving feedback to teachers, as well as coordinating, together with the teachers, the progressive improvement in lesson planning methodologies (BELLEI et al., 2014).

In terms of pedagogical curriculum management, Beltrán emphasizes that this educational professional collaborates with the school rector/director in various activities; he or she “[…] supervises the work of teachers, plans and coordinates teaching activities, ensures curriculum implementation, provides pedagogical support, among other [tasks]. Therefore, the outcomes of these activities would, to a large extent, be the result of his or her management and coordination” (2014, p. 943).

In this context, Sepúlveda (2005) identifies different stages, modes and actions pertaining to pedagogical coordination, which are specified in Table 1. The professional figure we are describing is therefore situated within the context of pedagogical leadership, of which the fundamental responsibility is to support the educational practices of teachers and, above all, the students’ learning, according to the proposals declared in the OECD’s report (PONT; NUSCHE; MOORMAN, 2008).

Table 1 – Categories of Pedagogical Coordination

| The Technical Pedagogical Unit’s (UTP in Spanish) stages of the development | Types or modes of coordination | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Control stage | Bureaucratic: focused on instructions: on requirements, forms, and requests for teachers’ reports | • Reviewing teaching plans • Reviewing tests • Reviewing lessons |

| Level 2 Destabilization stage/ transactions | Occasional and emergent Event organization | • Meetings about guidelines and external forms • Organization of work groups designed according to external regulations. • Various unspecified tasks |

Source: Sepúlveda (2005).

The Chilean subsidized subsystem

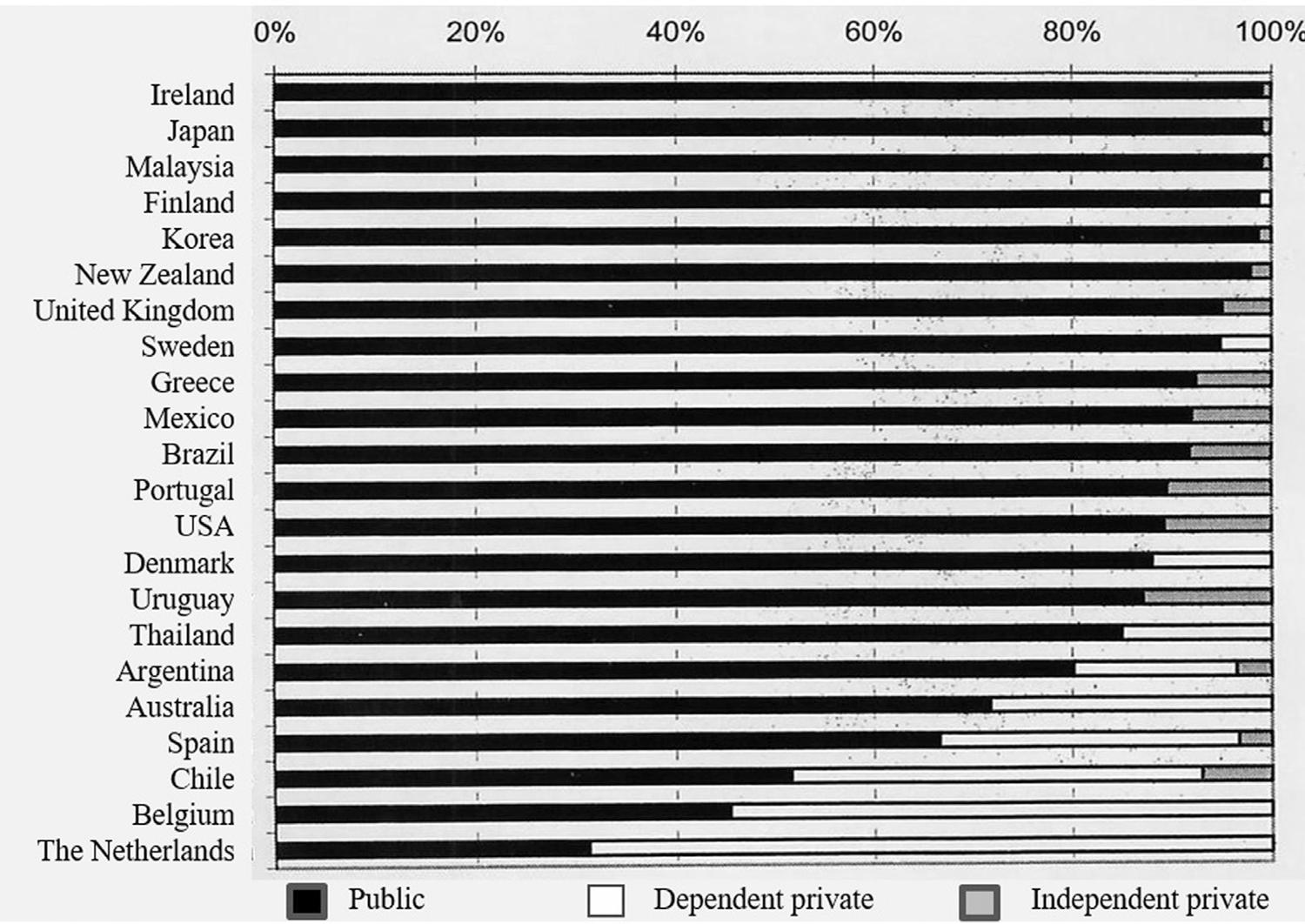

According to Brunner (2006), Chile’s education system is divided among different institutions (corresponding to international criteria) such as: public schools, which correspond to municipal centers; dependent private schools, which are similar to private subsidized centers; and independent private schools, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: OECD (2005).

Figure 1 Distribution of Primary School Enrollment by Type of Provider (percentage)

According to preliminary data from the Centro de Estudios (CHILE, 2017) in the Chilean education system’s 2016 school enrollment, subsidized private educational institutions took in 1,942,222 students, equivalent to 54.6% of the total possible student population. This subsystem comes from the dawn of the Republic, and its nexus is much older than is believed, seeing that the predominant changes that have taken place over the last three decades are nothing more than a continuation of a long historical process (OSSA, 2007).

Elacqua (2009 apud LIBERTAD; DESARROLLO, 2011) defines the subsidized private subsystem within this framework, pointing out that non-profit schools (Catholic, Protestant or non-religious) and for-profit (independent) schools coexist, the former representing 80% of the private subsystem and consisting of schools that were mostly founded by teachers. Accordingly, Anand, Mizala, and Repetto provide the following reflection:

The tendency in recent years has been for families to send their children to subsidized private schools at the expense of municipal ones. This is partly because, as empirical evidence illustrates, the former demonstrate better school performance, a factor that has influenced the parents’ preference. (2009, p. 372).

School vulnerability in the context of the educational subsystem

Vulnerability corresponds to “[…] the situation in which some social groups find and/or may find themselves according to different periods of time and contexts” (GAIRÍN; SUÁREZ, 2013, p. 26); the authors are referring to social groups that are less represented in the school system than what corresponds to them demographically. To describe the situation, today, the School Vulnerability Index (IVE in Spanish) is used, which is an indicator prepared each year by the National School Aid and Scholarship Board (JUNAEB in Spanish), following the implementation of a survey that categorizes the first year primary school and first year secondary school students in order to target the allocation of rations in the School Feeding Program.

It is important to add that, in order to serve the most under-resourced population in terms of socio-economic and cultural capital, the Ley de Subvención Escolar (Preferential School Subsidy Law), otherwise known as the SEP in Spanish, was created (CHILE, 2008). Thus, two normative references coexist: the SEP law, which was created to solve the problem of vulnerability, and the JUNAEB, which allocates food rations and other aid according to students’ social and economic conditions.

The previous targeted contributions are complemented by Decree 196, which establishes that in order for educational establishments to receive the subsidy for school institutions affiliated with the Ministry of Education, at least 15% of their student population must consist of socioeconomically vulnerable students.

Methodological framework

In this section, we explore the research design process, which came into fruition by concretely specifying how to achieve the goals of the study within a given context.

Design and type of research

The research conducted for this study is “[…] flexible and navigates between events and their interpretation, between answers and developing theory. Its purpose lies in reconstructing reality as observed by the actors of a previously defined social system” (ALBERT, 2007, p. 171). The study follows a sequential design: during the first stage, “quantitative or qualitative data is collected and analyzed, and during the second phase, data from the remaining method is collected and analyzed” (HERNÁNDEZ; FERNÁNDEZ; BAPTISTA, 2010, p. 559).

In addition, the study employs an ethnographic approach in that it seeks to analytically and interpretatively reconstruct the culture, ways of life, and social structure of the group in question (RODRÍGUEZ; GIL; GARCÍA, 1999) using a single case study which is explored in depth, and engaging with different perspectives and research methods framed within a natural and complex context.

Key informants

The sample used focuses on the head of pedagogy in the private subsidized subsystem within the context of vulnerability in the eighth region. On this topic, Rodríguez, Gil and García state that “[… heads of pedagogy] have access to the most important information about the activities of an educational community, group or institution; with enough experience and knowledge on the subject addressed in the research” (1999, p. 127). Four heads of pedagogy were therefore considered, as specified in Table 2.

Table 2 Description of Key Informants

| Subject | School | Commune | IVE* |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | Montaner | Hualpén | 64,68 |

| O2 | Edward | Concepción | 41,37 |

| O3 | San Patricio | Chiguayante | 57,92 |

| O4 | Eliecer | Talcahuano | 63,23 |

* School Vulnerability Index

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The participant sample constituted a Pedagogical Management Committee (Comité de Jefatura Pedagógica in Spanish and hereinafter referred to as CJP), which met over five work sessions of two and a half hours each, in addition to the individual and group work conducted outside of normal working hours in order to supplement the proposal’s contributions; the amount of work invested thus reached a complementary total of more than 15 hours of dedication per participant. Meeting minutes were recorded during these sessions, with the support of self-explanatory guides and short recordings.

Once the CJP established the profile of the head of pedagogy and this profile was submitted to an external validation both by a body of sostenedores as well as by experts in higher education, it was then rated within the context of the subsystem under study using a pilot sample selected according to the following criteria:

Being a sostenedor and/or director of the subsidized private sector

Belonging to communes of one of the four provinces of the Biobío region

Having a level of vulnerability greater than 40%, thus fully complying with the current legislation that stipulates that schools must have at least 15% vulnerability in order to receive national subsidies

Belonging to a private school in Chile (FIDE, CONACEP or others)

The application of these criteria resulted in a group of ninety volunteer participants made up of directors and legal representatives (sostenedores) from subsidized private establishments in the region under study. The participants come from twenty-five subsidized private schools that function within a context of vulnerability and that meet the previously discussed requirements.

Information analysis techniques

The research process constituted sequential phases that combined both quantitative and qualitative methods in order to complement each other and thus improve the quality of the results and fulfill the research goals.

The Committee (CJP) first prepared a profile proposal, taking into account official documents, specifically those related to the pedagogical head of the management teams, the competencies outlined by the Fundación Chile, and the scale used to evaluate the performance of the management team of educational centers, with the help of a tax matrix, which allowed for their rating to be recorded, with any potential observations, in terms of: approval, modified approval, or rejection. In addition to these documents, the research also included the CJP meeting minutes and the group audiovisual resources.

Subsequently, the focus group, comprising sostenedores, was called upon in order to find out and contrast their opinion on the categories of analysis that had been proposed for the Head of Pedagogy Profile.

Finally, the questionnaire seeks to validate the content of the questions formed in the focus group, by electronically contacting four higher education experts to request their opinion on the professional competencies of the head of pedagogy in the vulnerable subsidized private sector. These experts worked under the Delphi methodology and satisfied the stipulated criteria of being professionals with: more than 20 years of professional experience, job training in subjects concerning management, and a specialization in educational administration. They were also asked to have experience in the national and foreign sphere, and to have held managerial positions.

Once the profile was validated, the Competency Profile Scale for the head of pedagogy was adjusted, reflecting the importance that professional competencies have and should have, based on the following four rating categories: limited, sufficient, high, and outstanding. The consultation was conducted with a pilot sample of managers and sostenedores, who were selected based on their representational background, specialization, and knowledge of the Chilean educational context. They also needed to have more than five years of experience in executive management and that they had postgraduate studies at the master and diploma level, and postgraduate degrees in school administration and management, vocational guidance, or learning assessment. In addition, the members of the pilot sample group worked in private subsidized schools in vulnerable contexts in different communes in the four provinces of the Biobío region.

Data analysis strategy

After determining the categories of analysis, the content analysis is performed, taking into account the various techniques implemented and seeking out methodological triangulation, where various techniques provide different knowledge about the object of study and increase the credibility of the information. In this case, holistic knowledge was acquired thanks to the contrasting of results, as can be demonstrated in the final proposal’s conclusions.

Results

As a result of the analysis of the information collected and the CJP experience, the following profile (see Table 3) of the professional competencies of the head of pedagogy is established, comprising the following domains, with their respective competencies: pedagogical leadership; pedagogical-administrative support; curricular management of learning; and innovation project management.

Table 3 Competencies of the Head of Pedagogy in Centers in Vulnerable Contexts

| HEAD OF TECHNICAL PEDAGOGICAL UNIT |

|---|

| DOMAIN I Competencies: Pedagogical Leadership • Planning the collaborative participation of the coordinators of each area of the pedagogical technical tasks derived from the Institutional Educational Project. • Managing, together with section coordinators and teachers, the innovation processes and strategic goals proposed in the Pedagogical Technical Project. • Coordinating the academic and administrative work of section coordinators and teachers. • Launching pedagogical strategies and strategic goals with section coordinators and teachers for the continuous improvement of the Technical Pedagogical area. |

| DOMAIN II Competencies: Pedagogical-Administrative Support • Offering guidance to section coordinators and teachers in the methodological approaches for learning achievements in accordance with the characteristics of students in vulnerable sectors. • Involving the different levels of the school community in familiarization with activities and projections for units and learning areas. • Supporting the state of progress towards the pedagogical goals of curricular management of vulnerable environments in accordance with the sociocultural reality of the students. • Monitoring pedagogical strategies based on results within vulnerable contexts. |

| Domain III Competencies: Curricular Management of Learning • Communicating procedures for curricular coverage and programming according to applicable plans. • Managing, together with the area coordinators and teachers, compliance with curricular proposals to be carried out in the classroom. • Training area coordinators and teachers in compliance with subject programs. • Evaluating the progress of the curricular management of vulnerable environments and the achievement of proposed learning-based goals. |

| Domain IV Competencies: Innovation Project Management • Establishing support networks with institutions for fulfilling the Institutional Educational Project’s strategic goals. • Satisfying the needs and projections of certain academic areas in conjunction with area coordinators and in accordance with the reality of vulnerable contexts. • Prioritizing pedagogical opportunities and resources based on school performance goals in vulnerable contexts. • Monitoring pedagogical strategies based on results within vulnerable contexts. |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

As we can see, the pedagogical leadership competency refers to promoting learning-teaching processes among section coordinators and teachers in accordance with applicable plans and programs. Meanwhile, the second domain concerns coordinating the processes of planning, monitoring and supporting teachers, while the domain of curricular management of learning refers to monitoring the curricular processes in accordance with applicable regulations and their evaluation. Lastly, the fourth domain refers to organizing innovation projects to meet the pedagogical needs of vulnerable contexts.

Table 4 outlines the main results obtained after the sequential process of collecting and validating the information; these results reveal the most significant opinions that were expressed throughout the research process.

Table 4 Methodological Triangulation Matrix5

| Category | Subcategory | Focus group Sostenedores | Questionnaire Experts | Documentary analysis and focus group - CJP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional competencies of the head of pedagogy | Competency domains | - Pedagogical leadership for teachers. - It is important for the head of the UTP to get along very well with the management team. - He or she also has the responsibility to form part of the team of people that he or she is directing in this whole process. | - They are necessary for transforming the educational center into an environment for catalyzing the changes that influence what makes this context vulnerable and, therefore, requiring a distinct and quality education. -Effectiveness when facing school situations. | - The defined domains constitute an effective field of action for responding to the educational challenges of a vulnerable subsidized private school. - They demand demonstrating confidence and knowledge. |

| professional competencies | - They have to have the necessary competencies to be able to act and be an efficient adviser, right ... eh for the process that is ingrained with the Institutional Educational Project’s (PEI in Spanish) goals. - They demand teamwork and collaboration. - The job of forming networks - These are competencies that have to be developed both in vulnerable and non-vulnerable schools because it is the soul, it is the alma mater of success for students. | - Add “in vulnerable contexts,” because we know that there are frequent conflicts in this sector. - While a school that provided pedagogical support from the technical coordination team would be innovative, it seems like a good idea in vulnerable contexts. | - It implies the ability to be adaptive, communicative, and intuitive. - Being restrained and tempered. - Being attentive and collaborative. - In terms of professional competencies, there should be familiarity with the context, flexibility, adaptability, integration. - Being balanced in your group and individual performance. | |

| Assessment of professional competencies | -Should be able to interpret ... uh ... what direction says in to put it into practice. - It would be good to make a profile for each participant of the management team. - The job is not done right by people who are sitting at a desk . . . it is done with people are doing the actual work . . . this is my role within this school in a vulnerable context. - I think it’s a serious and responsible job. | -The profile constitutes a social commitment to education, to encouraging the social mobility and development of vulnerable social groups. - Establishing attributes would be a contribution. - Depending on the style and leadership competencies that he or she has and the commitment he or she makes with the families and networks. - A clear vocation for pedagogical work under difficult conditions. | - It’s a step towards determining the competencies required to lead educational processes in the sector. - Helps to perform an optimal job. - Requires, among other aspects, the exchange of good practices with managers; the creation of networks at different levels; contextual analyses; community engagement; and continuous training at different levels |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

We can thus highlight that the most characteristic findings of the validation, using Table 4 as a reference, are:

The informants consider the leadership profile to be relevant.

The importance of working on the pedagogical support of teachers.

The head of pedagogy is responsible for accompanying the pedagogical process of teachers and for taking effective action in a vulnerable subsidized private school.

Regarding the professional competencies established in the profile, it is worth mentioning the following:

Professional competencies are relevant.

The competencies entail collaborative teamwork with the management team.

The results highlight the importance of managing vulnerable contexts for the achievement of school learning.

The results emphasize pedagogical support to help students. Regarding the assessment of the competencies, informants indicate that: a. It is a step forward, a contribution and social commitment to education.

It should be done by people who work on the ground in schools in vulnerable contexts.

It involves the exchange of good practices, support networks, and community engagement.

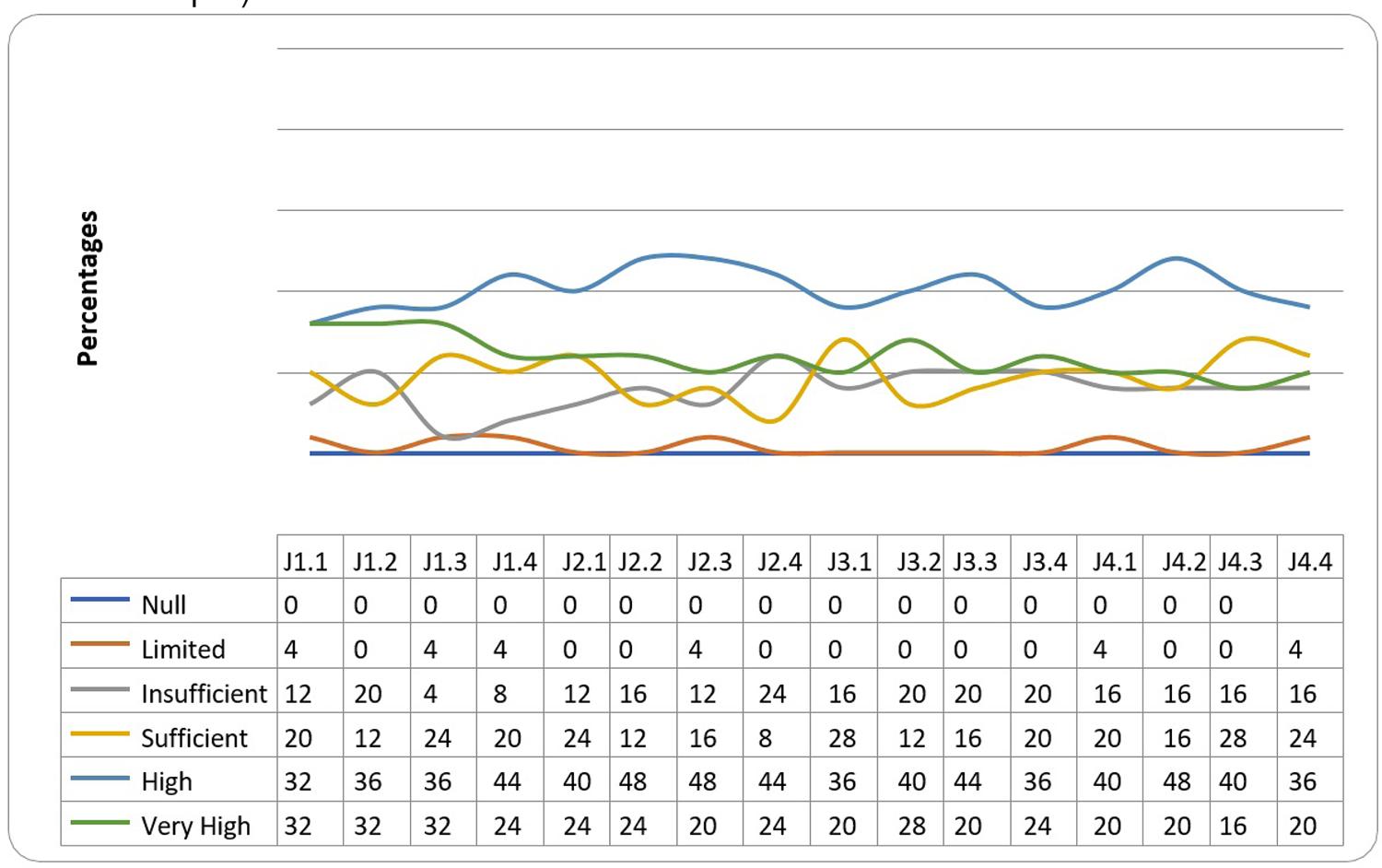

In addition to the above, the rating of the levels of achievement in the professional competencies of the head of UTP is also taken into account, in accordance with the sample (See Figure 2).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 Percentage Distribution of Levels of Achievement of the Professional Competencies of the Head of UTP (from the sample)

Figure 2 illustrates that the predominant levels of achievement of the population fall between high and very high. At the high level we see the competencies related to the involvement of different school sectors in activities, the state of progress of the pedagogical goals, and the Special Educational Needs (NEE in Spanish) services and their reach in academic areas. Meanwhile, at the very high level, the competencies that are highlighted are: coordinators’ collaborative planning, innovation process management, coordination of academic and administrative work, and management with area coordinators and teachers.

Some of the results obtained are similar to those identified in the analysis of the competencies of the guidance counselors (VILLARROEL; GAIRÍN; GARCÉS, 2017). Thus, both professional profiles (heads of pedagogy and guidance counselors) share: the importance of collaborative work with the management team, the particularity of working in vulnerable contexts, an approach focused on supporting students in their academic and life projects, and professional interventions that involve extra social commitment. In fact, the most important part, in practice, of the work of the technical pedagogical managers is to accompany and guide their students’ educational processes.

Discussion

The head of pedagogy in the private subsidized vulnerable sector in Chile is a professional whose main impact “[...] consists of putting their managerial focus on pedagogical outcomes, prioritizing them over administrative tasks” (CARBONE et al., 2008, p. 17).

Meanwhile, Montecinos, Aravena, and Tagle point out:

The greatest advantage of school networks involving both the director and the head of the UTP is that they can delegate tasks and responsibilities to among their communities, so that they can be actively present, and not just physically present, at network meetings. This entails developing distributed leadership capacities with these managers. (2016, p. 62).

In addition, the motivation and leadership of management—directors and heads of pedagogy—of these schools play a key role in persuading teachers of the usefulness of learning outcome assessments for the continuous improvement of their professional work and as learning opportunities for the students, while also helping to overcome resistance (BELLEI et al., 2014).

In turn, Beltrán suggest the following idea about head of pedagogy role:

It is their job to take on a central role in the standardization and consolidation of the Technical-Pedagogical Unit as a work structure within the organization—not only the role that they themselves play and in terms of their position, but also because with this intervention, they express what makes them who they are. (2014, p. 947).

The head of pedagogy’s focus on academic processes is not, therefore, only an activity related to the role they have been assigned, but is instead—in the case of vulnerable groups—also a necessity. We must consider that vulnerability affects, first of all, school attendance, and secondly, academic performance. From this, we can therefore deduce that the figure of the technical-pedagogical head takes on greater relevance in vulnerable contexts because they are the ones that can most influence the areas of weakness that go hand in hand with low school performance.

We must also clarify that the mere presence of these managers and their good professional practices can increase the chances of improving school performance among vulnerable groups, although they are not the direct cause of these improvements. The conditions that sometimes accompany vulnerability (such as dysfunctional families, low socioeconomic status, gender, among others) are external to the school effort and will not improve with educational intervention alone.

The assessment of the UTP head’s work takes on greater clout “[…] due to how much it can make teaching more predictable, improve coordination among teachers, and monitor curricular implementation” (BELLEI et al., 2014, p. 27). Thus, the school’s performance as a whole becomes a professional challenge mainly for the people (teachers) who are closest to the students’ learning goals. This phenomena is directly related to the work that the heads of pedagogy invest in leadership that is more focused on learning.

As noted by Du Four and Manzano (2009 apud GONZÁLEZ, 2013): “[...] If the fundamental purpose of schools is to ensure that all students learn at high levels, then schools do not need instructional leaders, they need leaders to focus on proof of learning.” (p. 119).

Undoubtedly, this statement is consistent with the results of the study that link learning outcomes in vulnerable communities with the visible work of the head of pedagogy. The takeaway is that the head of pedagogy, when working with third parties—that is, with the teachers who intervene in the classroom with the students—can make an impact in obtaining desired academic outcomes. Authors such as Leithwood et al. (2004, 2006) and Robinson et al. (2009 apud GONZÁLEZ, 2013), support this idea.

Conclusions

Regarding the main objective of this research concerning the profile of the head of pedagogy in subsidized educational centers within vulnerable contexts, our conclusions indicate that this profile is composed of four domains: pedagogical leadership, pedagogical-administrative support, curricular management of learning, and innovation project management; in turn, these four domains comprise four professional competencies each (sixteen competencies in total).

We will proceed to highlight the competencies that we consider most pertinent to the specific circumstances of vulnerable contexts, such as: 1) guiding section coordinators and teachers in methodological approaches to learning achievements according to the characteristics of students belonging vulnerable groups; 2) supporting progress towards the curriculum’s pedagogical goals within vulnerable environments based on the sociocultural reality of the students; and monitoring pedagogical strategies based on outcomes in vulnerable contexts; 3) observing classroom-support interventions, offering methodological guidance together with section coordinators and teachers, and taking advantage of the additional support of the head of UTP or more experienced teachers in lesson planning and designing teaching materials. All of these aspects have already been discussed by Bellei et al. (2014).

Regarding the first specific objective, the Pedagogical Management Committee deems fitting the use of the benchmarks implemented by the Fundación Chile and the scale to evaluate the performance of the Management Team of Educational Centers. In particular, we are referring to actions related to the following aspects: activity planning, supervising academic work, managing innovative projects and, possessing personal qualities for the position such as responsibility, assertiveness, and initiative. In contrast, the study revealed differences of opinion on the indicators related to the following: the Institutional Educational Project (PEI in Spanish); class programming, implementation, consolidation and evaluation; and negotiation and conflict resolution.

The four domains with four distinctive professional competencies for the particular subsidized sector located in a context of vulnerability are considered to be relevant. In addition, the study can conclude that the established profile consists of an efficient framework of action for responding to the educational challenges of a subsidized private school, helping to identify aspects to be assessed and promoted, to perform optimal work, and to lead educational processes in the sector.

The sostenedores consider the pedagogical competencies to be relevant in the head of pedagogy; for them, the highlighted competencies entail teamwork and they go hand in hand with the duty of distributed leadership focused on the creation of supporting strategies for achieving school learning.

Finally, the higher education experts who validated the proposal stress that the profile constitutes a social commitment to education; they also highlight the importance of the pedagogical competencies related to reducing the vulnerability of different groups and, more specifically, the competencies related to providing support for the students so that they acquire useful tools for social mobility that allow them to overcome their situation. It is important to remember that vulnerability is identified as a sociocultural-economic reality that is temporary and reversible; in addition, lack of intervention can enhance the development of worsening situations of discrimination, marginalization, and exclusion that can irreversibly impede the full process of integration as citizens into the given social reality.

In any case, the contextual reality of vulnerability and the variety of factors that enhance it suggest the need for new in-depth studies on:

Creating standards, indicators and competency-based tools stemming from the profile developed for the private subsidized subsystem.

Expanding the range of the study to not only focus on the private subsidized subsystem, but instead to conduct more cross-sectional studies concerning all subsystems—both municipal and private.

Developing studies that take into account the variables that may be involved in the investigation, such as: the type of establishment, number of students, involvement of other communes of the Biobío region and at national level, etc.

Understanding that the issue revolves around familiarizing ourselves more with the phenomenon of vulnerability and the pedagogical interventions that can mitigate its presence in the classroom.

As for future projects, it would be enriching to develop longitudinal studies that allow for monitoring the interventions carried out by the head of pedagogy, as well as using more complex techniques to calculate the causal effects of the variables involved.

REFERENCES

AHUMADA, Luis; SISTO, Vicente; MONTECINOS, Carmen. Desarrollo y Validación de una Escala para Evaluar el Funcionamiento del Equipo Directivo de los Centros Educativos. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, Glen Allen, v. 2, n. 42, p. 228-235, 2008. [ Links ]

ALBERT, Mª José. La investigación educativa: claves teóricas. Madrid: Mc Graw Hill, 2007. [ Links ]

ANAND, Priyanka; MIZALA, Alejandra; REPETTO, Andrea. Using school scholarships to estimate the effect of private education on the academic achievement of low-income students in Chile. Economics of Education Review, Berkelye, v. 28, p. 370-381, 2009. [ Links ]

BELLEI, Cristián et al. (Coord.). Lo aprendí en la escuela ¿Cómo se logran procesos de mejoramiento escolar? Santiago de Chile: LOM, 2014. [ Links ]

BELTRÁN, Juan Carlos. Factores que dificultan la gestión pedagógica curricular de los jefes de unidades técnico-pedagógicas. RMIE, México, D.F., v. 19, n. 62, p. 939-961, 2014. [ Links ]

BRUNNER, José Joaquín. Calidad de la educación: claves para el debate. La organización de los sistemas escolares en el mundo contemporáneo. Santiago de Chile: RIL: Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez, 2014. [ Links ]

CARBONE, Ricardo. Situación de liderazgo educativo en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Mineduc – UAH, 2008. [ Links ]

CEPPE. Centro de Estudios de Políticas y Prácticas en Educación. Manual de gestión de competencias para directivos, docentes y profesionales de apoyo en instituciones escolares. Santiago de Chile: Fundación Chile, 2006. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ministerio de Educación. Centro de estudios: datos abiertos 2017. Santiago de Chile: Mineduc, 2017. Disponible en: <http://datosabiertos.mineduc.cl/. Acceso en: 20 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ministerio de Educación. Ley subvención escolar preferencial n. 20.248, 01 de febrero de 2001. Santiago de Chile: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, 2008. Disponible en: <http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=269001. Acceso en: 20 dic. 2014. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ministerio de Educación. Reglamento sobre obligatoriedad de establecimientos educacionales de contar con a lo menos un 15% de alumnos en condiciones de vulnerabilidad socioeconómica como requisito para impetrar la subvención. Santiago de Chile: Mineduc, 2006. Disponible en: http://www.comunidadescolar.cl/marco_legal/Decretos/Decreto%20196%20Vulnerabilidad.pdf. Acceso en: 24 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

DAY, Christopher et al. Ten strong claims about successful school leadership. Nottingham: NCSL, 2010. [ Links ]

GAIRÍN, Joaquín; CASTRO, Diego (Coord.). Competencias para el ejercicio de la dirección de instituciones educativas: reflexiones y experiencias. Santiago de Chile: Santillana, 2012. [ Links ]

GAIRÍN, Joaquín; SUÁREZ, Cecilia Inés. La vulnerabilidad en la educación superior. In: GAIRÍN, Joaquín; RODRÍGUEZ-GÓMEZ, David; CASTRO, Diego (Coord.). Éxito académico de colectivos vulnerables en entornos de riesgo en Latinoamérica. Madrid: Wolters Kluwer Educación, 2013. p. 135-138. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ, María Teresa. El liderazgo pedagógico: características y pautas para su desarrollo. En competencias de liderazgo en equipos directivos. In: VILLA, Aurelio (Ed.); CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE DIRECCIÓN DE CENTROS EDUCATIVOS, 6., 2013, Bilbao - Universidad de Deusto. Liderazgo pedagógico en los centros educativos: competencias de equipos directivos, profesorado y orientadores. Bilbao: Mensajero, 2013. p. 119-120. [ Links ]

HALLINGER, Philip; WANG, Wen Chung. Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management rating scale. Dordrecht: Springer, 2015. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ, Roberto; FERNÁNDEZ, Carlos; BAPTISTA, Pilar. Metodología de la investigación. México, D.F.: Mc Graw-Hill, 2010. [ Links ]

LIBERTAD; DESARROLLO. Desmitificando el Lucro de los Colegios, Santiago de Chile, n. 1.027, 2011. Disponible en: <https://www.yumpu.com/es/document/view/14096833/desmitificando-el-lucro-de-los-colegiospdf-libertad-y-desarrollo. Acceso en: 24 jun. 2016. [ Links ]

MANSILLA, Juan; TAPIA, Carmen Paz; BECERRA Sandra. Elementos obstaculizadores de la gestión pedagógica en liceos situados en contextos vulnerables. Educere, Mérida, v. 16, n. 53, p. 127-136, 2012. [ Links ]

MONTECINOS, Carmen; ARAVENA, Felipe; TAGLE, Romina. Liderazgo escolar en los distintos niveles del sistema: notas técnicas para orientar sus acciones. Líderes Educativos, Valparaíso, p. 9-10, 2016. Disponible en: https://www.lidereseducativos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Liderazgo-Escolar-en-los-Distintos-Niveles-del-Sistema-LIDERES-EDUCATIVOS.pdf. Acceso en: 20 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

MORDUCHOWICZ, Alejandro; AYLWIN, Marina; WOLFF, Laurence. Desarrollo de la capacidad institucional y de gestión de los ministerios de educación en centroamérica y República Dominicana: Programa de Promoción de la Reforma Educativa en América Latina y el Caribe. Preal, Santiago de Chile, n. 42, nov. 2008. Disponible en: <file:///C:/Documents%20and%20Settings/Usuario/Mis%20documentos/Downloads/documento_42_preal.pdf>. Acceso en: 20 jun. 2019. [ Links ]

OCDE. Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económico. Education trends in perspective: analysis of the World education indicators. París: OECD, 2005. [ Links ]

OSSA, Juan Luis. El estado y los particulares en la educación chilena, 1888-1920. [S.l.]: Centro de Estudios Públicos, 2007. Disponible en: https://www.cepchile.cl/el-estado-y-los- particulares-en-la-educacion-chilena-1888-1920/cep/2016-03-04/094217.html. Acceso en: 20 jul. 2012. [ Links ]

PONT, Beatriz; NUSCHE, Deborah; MOORMAN, Hunter. Mejorar el liderazgo escolar.Volumen 1: Políticas y Prácticas. París: OCDE: Dirección de Educación, 2008. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, Viviane; HOHEPA, Margie; LLOYD, Claire. School leadership and student outcomes: identifying what works and why. Best Evidence Syntheses Iteration (BES). New Zealand: Ministry of Education, 2009. Disponible en: <http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2515/60169/60170. Acceso en: 27 jul. 2018. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, Viviane; LLOYD, Claire; ROWE, Kenneth. The impact leadership on student outcomes: an analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quaerterly, Salt Lake City, v. 44, n. 5, p. 635-674, 2008. [ Links ]

RODRÍGUEZ, Gregorio; GIL, Javier; GARCÍA, Eduardo. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Málaga: Aljibe, 1999. [ Links ]

SEPÚLVEDA, Gabriela. La coordinación pedagógica. Temuco: Universidad de la Frontera: Grupo Innovat, 2005. [ Links ]

VILLA, Aurelio. Competencias de liderazgo en equipos directivos. In: VILLA, Aurelio (Ed.); CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE DIRECCIÓN DE CENTROS EDUCATIVOS, 6., 2013, Bilbao - Universidad de Deusto. Liderazgo pedagógico en los centros educativos: competencias de equipos directivos, profesorado y orientadores. Bilbao: Mensajero, 2013. p. 329-366. [ Links ]

VILLARROEL, Daniel; GAIRÍN, Joaquín; GARCÉS, José. Competencias del orientador de centros subvencionados vulnerables para la mejorar de la convivencia escolar. Revista de Orientación Educacional, Valparaíso, v. 31, n. 60, p. 100-114, 2017. [ Links ]

VILLARROEL, Daniel; GAIRÍN, Joaquín; GARCÉS, José. Competencias profesionales del director escolar en centros situados en contextos vulnerables. Educere, Mérida, v. 18, n. 60, p. 303-311, 2014. [ Links ]

1- This article is the product of the doctoral thesis Competencias profesionales del equipo directivo del sector particular subvencionado chileno en contextos vulnerables (VILLARROEL; GAIRÍN, 2014).

4- Name given to the school’s legal representative which, in the case of municipal schools, coincides with the Head of the Department of Municipal Education Administration (DAEM in Spanish).

Received: June 02, 2018; Accepted: February 12, 2019

texto en

texto en