Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 11-Fev-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046213265

THEME SECTION: Childhood, Politics and Education

The limits of toleration in an education for democracy: Camara Mirim Program – Plenarinho 1

2- Universidade de Brasília, Brasília-DF, Brasil . Contact: anamarusia@hotmail.com.

Democracy involves the political participation of citizens, which in turn requires the knowledge and practice obtained from education. When opening spaces for debate, however, the appearance of controversy should be expected, paradoxically including anti-democratic attitudes. For young audiences, the matter becomes even more problematic. What should and should not be tolerated in an education for democracy? To answer that question, this research does a literature review on the concept of tolerance in political theory and its need in recent democracies, along with the challenges for effective participation (with unpredictable effects) and the discussion of the educators’ role around what and how to work on for such apprenticeship. The empirical part focuses on the educational program Plenarinho (Little Plenary) from the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, in the action Camara Mirim (Chamber for Kids), which encourages the political participation of children through a bill contest. The contents of over 6k proposals sent between 2006 and 2016 were analyzed in search for intolerant ideas, to find out if they had grown in numbers over recent years, in which a greater political polarization in Brazil and a resurgence of intolerance have been observed. The results point to an occurrence of non-democratic ideas that was not significant, keeping the same level throughout 10 years of Camara Mirim. The most interesting number is, however, the considerable presence of propositions aiming precisely at countering intolerance. Thus, along with the recommendations present in the literature, the children themselves present the key to deal with the problem.

Key words: Education for democracy; Toleration; Children’s political participation

A democracia envolve participação política do cidadão, que, por sua vez, requer conhecimento e prática, obtidos com a educação. No entanto, ao abrirem-se os espaços de debate, deve-se esperar o surgimento de controvérsias, incluindo, paradoxalmente, atitudes antidemocráticas. Com públicos infantojuvenis, essa questão torna-se ainda mais problemática. O que deve ou não ser tolerado na educação para a democracia? Para responder a essa pergunta, a presente pesquisa faz a revisão bibliográfica dos conceitos de tolerância na teoria política e sua necessidade nas democracias recentes, com os desafios para a participação efetiva (cujos efeitos não são previsíveis) e a discussão do papel dos educadores acerca do que e como deve ser trabalhado na aprendizagem. A parte empírica foca o programa educativo Plenarinho, da Câmara dos Deputados, na ação Câmara Mirim, que incentiva a participação política de crianças e adolescentes por meio de um concurso de projetos de lei. É analisado o conteúdo de mais de 6 mil propostas enviadas entre 2006 e 2016, em busca de ideias intolerantes e se houve crescimento numérico nos anos mais recentes, em que se observa uma maior polarização política no Brasil e recrudescimento da intolerância. Os resultados apontam para a ocorrência pouco significativa de ideias não democráticas, que se mantiveram no patamar em 10 anos de Câmara Mirim. O dado mais interessante, contudo, está na presença considerável de propostas que visam justamente a combater a intolerância. Assim, junto com as recomendações da literatura, as próprias crianças apresentam a chave para lidar com o problema.

Palavras-Chave: Educação para a democracia; Tolerância; Participação política infantojuvenil

Introduction

For Dewey (1939) , democracy is a way of living conducted by our faith in the capacity of judgment and intelligent action of human beings, within appropriate conditions. By principle, in democracies, regular individuals should have the opportunity to develop their talents by voluntary, coercion-free means ( DEWEY, 1937 ) and thus become able to direct societal matters by participating in the political, social, cultural, and economic institutions that most affect them ( KOVACS, 2009 ). This free and critical participation requires knowledge and practice to deal with the diversity of conflicting opinions, worldviews, and proposals, especially when choosing one denies the other. In this constant clash, one concept arises as essential: tolerance.

The critical thinking demanded by the democratic process needs to deal with the rupture of common sense, diverse points of view, the subversive, which give subaltern groups a chance for democratic renewal ( KOVACS, 2009 ). Even if liberal democracy stands on the defense of equality between individuals, the fact is that they are not the same, which makes toleration a virtue ( CARTER, 2013 ).

In modern democratic societies, including Brazil, tolerance gains urgency ( COSTANDIUS; ROSOCHACKI, 2012 ) as citizens need to live alongside more and more diverse and conflicting claims from other individuals and social, cultural, ethnical, and religious groups ( WERLE, 2012 ). The contact with difference, without which there would be no need for tolerance, comes from processes of individualization, multiculturalism, globalization, among others ( MCKINNON; CASTIGLIONE, 2003 ). In this context, intolerance, discrimination, intimidation, violence, and other threats to democracy also emerge (DECLARATION, 1995).

There is no way of letting each citizen define separately and on her own what she will tolerate, under the risk of increasing intolerance ( VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ). Democracy itself should define the limits of what is tolerable or not ( WERLE, 2012 ). However, how to do that without limiting the very foundations of democracy? ( ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ).

In a legal scope, the installation of authoritarian regimes by leaders who had been democratically elected initiated a series of protective actions from European countries, in the beginning of the 20thcentury, characterizing what Loewenstein (1937) called militant democracy , that is, the one that actively fights for inhibiting the growth of despotism.

Simultaneously, education has been pointed as fundamental for the political literacy and civic engagement of citizens. Political attitudes and behaviors emerge in childhood and adolescence, in a personal and social construction. Children must be offered opportunities for engagement where they live, so that they have a voice and that they be heard. It is not about individual cognition or social skills in context. Participation should be effective, as to develop a sense of agency and responsibility indispensable for adult citizenship ( DIAS; MENEZES, 2014 ).

On the one hand, democratic values should be fostered in the child. On the other, the expression of their opinions should be encouraged. The opposition presented is that of the group versus the individual; security in the learning space versus freedom of speech; inclusion versus exclusion ( ORLENIUS, 2008 ). Education is therefore not a stalled process of transmission and passive reception of principles; it contains ambiguities and should be prepared to be the very object of questioning and salutary dispute as well as of manifestations of intolerance and hate.

The challenge imposed here is to understand the limits of toleration in an education for democracy. The work is divided in two parts: the literature review on tolerance and the analysis of a children’s political participation initiative with educational purpose – the action Camara Mirim , promoted by the Chamber of Deputies’ Plenarinho.

What is tolerance?

This section presents different conceptions of tolerance in the literature, the permanent tensions within democratic regimes and the limits of the intolerable.

Most analyses of tolerance identify three components: (1) objection, or the negative evaluation of the object of toleration ( CARTER, 2013 ): something is viewed as “wrong” in order to be tolerated ( HANSEN, 2013 ; ORLENIUS, 2008 ); (2) acceptance, in which the tolerant decides not to interfere; and (3) a power condition, in which tolerant and tolerated are in an asymmetry and the first refrains the action of the latter, with whom he disagrees ( CARTER, 2013 ; VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ).

Forst (2003 , 2007, 2014 ; WERLE, 2012 ) identifies four conceptions of toleration: the one of permissiveness and condescendence; coexistence; mutual respect; and appreciation and self-esteem. For him, toleration should be thought of alongside the idea of political justice (and public justification) and the concept of democracy.

Some authors believe that tolerance is a State’s duty, since it holds the monopoly of force, for citizens would not have the power to reject the practices of others with whom they interact horizontally. The State should thus promote spaces for citizens to participate in the making of laws regarding this. However, such laws can generate unpredictable damage to certain forms of life ( VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ) or just not be enough, since many coups d’état occurred within institutional order ( MONTEIRO, 2015 ).

Other authors disagree on the prevalence of tolerance in the vertical relationship between the State and its citizens when affirming that personal tolerance in day-to-day relations is much more frequent (see VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ). Heyd (2008) sees tolerance neither as a political virtue nor as impersonal judgment, but as a deliberate, rational choice of the individual in relation to others.

Tolerance does not have, as seen, a consensual definition. For Saulius (2013) it is a notion reliant on context that does not hold any criteria to evaluate (our own or other’s) actions. Thus, any argument on a general acceptation of tolerance would bring about ambiguity and disinformation.

Besides, tolerance holds many paradoxes: how can a person, who tolerates what he thinks is wrong, be right? ( ALMOND, 2010 ; HANSEN, 2013 ; MCKINNON; CASTIGLIONE, 2003 ). How can tolerance be compatible with respect, if it implies evaluating something as negative or inferior? If an intolerant person abstains from attacking another, does her tolerance hold even more virtue? ( CARTER, 2013 ; HANSEN, 2013 ).

According to Williams (1996) , tolerance seems to be at once necessary and impossible. Necessary for resolving disputes without weapons. Impossible, because if there’s a threat of violence and rupture of social cooperation in certain circumstances, then the parts are already not willing to accept each other.

In the case of democracy, there are other paradoxes: if democracy does not tolerate the intolerant, it contradicts itself by becoming intolerant; if it tolerates, it risks being destroyed, which means a victory for intolerance (MANFREDI apud CABRAL, 1994 ; POPPER, 1966 ).

If prejudice is born of the ignorance and fear in relation to what is different, the free debate of ideas is a way of putting the cards on the table. However, there are many critiques to the deliberative processes that, under neutral façades, maintain or make political inequalities and intolerances invisible ( COSTANDIUS; ROSOCHACKI, 2012 ; ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ), or, when holding on to the public and political aspects of social living, leave untouched the private matters of religious, philosophical, and moral doctrines ( WERLE, 2012 ), precisely the ones that demand tolerance.

In practice, the asymmetry in forces may make it easier for a speech that is wrong to prevail ( COSTANDIUS; ROSOCHACKI, 2012 ; ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). In fact, it is possible to find rational justifications for any behavior (see CARTER, 2013 ; MONTEIRO, 2015 ; VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ). Even in participation arenas, minorities keep on being discriminated against and marginalized ( COSTANDIUS; ROSOCHACKI, 2012 ) as if they claimed for privileges ( SAULIUS, 2013 ). If they have an unpopular point of view, they are not even taken into account. And if the decision of the majority contradicts those views, it is difficult to find the frontier between legitimacy and the anti-democratic character of contestation ( CEVA, 2012 ).

However, if the public participative sphere presents problems, what could be another solution? What is the advantage of abstaining from debate? Other questions emerge: How can the State intervene without bumping on authoritarian censorship ( MONTEIRO, 2015 )? Who will finally define the limits of toleration ( FORST, 2014 )?

The answers may be in a comprehension of tolerance that encompasses both horizontal and vertical vectors. In the concept of mutuality, openness to others is fundamental to understanding them, admitting the value of different experiences in which tolerance gives way to respect ( ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). At the same time, according to Creppell (2008) , toleration is a political-social relationship and not an individual duty; it needs to be sustained (vertically) through institutions and political norms. The author defines mutuality as “a will to relationship”, which initiates tolerance and should also be its goal, allowing for continuous adjustments and negotiations, without expectations of consensus without conflict.

According to the Declaration on the Principles of Tolerance (1995):

Tolerance is not concession, condescension or indulgence. […] [It] is, above all, an active attitude prompted by recognition of the universal human rights and fundamental freedoms of others. […] [It] is to be exercised by individuals, groups and States […] is the responsibility that upholds human rights, […], democracy and the rule of law.

How would the action of the State take place? In the midst of militant democracy, Pedahzur (2004) identifies four controls to deal with intolerance: (1) administrative and intelligence; (2) legal and judicial; (3) social; and (4) educational. Their combination can follow a militant (individualized attack to the threats) or an immunized (more long-lasting, facing the roots of anti-democratic behaviors with less restrictive and more tolerant measures) route.

What would call forth one route or the other would be the level of threat. According to the literature, some practices simply cannot be tolerated: abuse, hate ( DEWEY, 1939 ), disrespect ( CARTER, 2013 ), discrimination ( CEVA, 2012 ), inciting or supporting violence, racism ( MONTEIRO, 2015 ), sexism, homophobia ( ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ), kidnaping, enslaving ( POPPER, 1966 ), murder, torture, rape, fraud ( WALDRON, 2003 ), terrorism ( ORLENIUS, 2008 ). These are behaviors that oppose human rights and the Rule of Law, essential to democracy ( MONTEIRO, 2015 ).

Intolerants must not be tolerated. The State can and should intervene in individual freedom and stop actions that could potentially cause harm ( MILL, 2001 ; WERLE, 2012 ; ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). Freedom of consciousness can be limited by the general interest for order and public security ( WERLE, 2012 ), for the continuity of democracy, and for the good of future generations ( NIESEN, 2002 ). Those who reject tolerance must not be tolerated ( MCKINNON; CASTIGLIONE, 2003 ), neither should those who threaten democracy and freedom, because the democratic methods must not be used to suppress democracy itself (PARDO, 1985 apud MONTEIRO, 2015 ).

The following section presents a few applications of educational controls in the immunized route, considering that the others are also involved with the educational process that aims at making young people apt to understand and tolerate diversity.

Tolerance and education

According to the Declaration of Principles on Tolerance (1995), “Education is the most effective means of preventing intolerance”, constituting an imperative priority. Once values are learned in childhood and solidified in adolescence, the teaching of tolerance aims at preparing students for life in a society that is more and more diverse because of demographic changes ( TITUS, 1998 ). This intent, however, involves challenges and risks, such as the tension between the duties and limits of the State in education and the paradox between the protection and the participation of youth.

The basic concept of education for tolerance consists in the rights and freedoms of students to ensure their respect and stimulate the will to protect rights and freedoms of others. The root is in the very definition of citizenship as the exercise of rights and duties: by extension, tolerance encompasses the right to be tolerated and the duty to tolerate. The educational goal, in this case, is the development of autonomous judgment, critical reflection, and ethical thinking. The methods need to be conscious of the cultural, social, economic, political, and religious sources of intolerance, that lead to fear, to exclusion, and to violence (DECLARATION, 1995).

Tolerance refers to a system of ethical values, but knowing or having such values does not mean to be tolerant. It is possible that a person easily tolerates ideas, but it is different – and difficult – to tolerate actions in others, especially those related to it ( SAULIUS, 2013 ).

One only learns to be tolerant by dealing with situations that demand it, that is, through experience ( DEWEY, 1939 ), even if within the protected environment of the school ( DIAS; MENEZES, 2014 ; ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). It should be a regular practice, and not occasional, in activities that widen the contact and interaction between groups, such as cooperative learning, to create understanding of others and empathy ( KLEIN, 1992 ; RICE, 2009 ).

School councils are an option to promote to children and young adults a first experience in the democratic and decision-making processes. The students debate questions concerning themselves and the school ( CRICK, 1998 ). It is fundamental that the environment inspires trust and respect, as well as promotes the interaction between free individuals, guaranteeing the balance between teachers and students, as adults and youngsters recognize one another as moral equals ( KLEIN, 1992 ; SAULIUS, 2013 ).

It is admitted that the exercise of citizenship (and toleration) involves the discussion of controversial matters. But how to deal with those? What to do with a student who demonstrates intolerance in these situations? To what extent can the youngster, with a forming identity, account for their own opinions? What if disobedience is indispensable for the reflection on laws that really need change ( CRICK, 1998 ), or to address manipulation, oppression, and cultural imperialism ( FREIRE, 1987 ; KOVACS, 2009 )?

Mill (2001) highlights that children and young adults require assistance and protection against the actions of others as well as their own. However, it is not only the maturity of the students that is at stake in the teaching of tolerance.

In the face of a notion of education as a duty of the State, disagreements appear on how far it can go. Generally speaking, the educational system, because of its great responsibility, is intolerant and authoritarian, making use of policing, disciplining, and punishing ( KOVACS, 2009 ). There also arise clashes with the conception of families around certain themes ( ALMOND, 2010 ; ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ; VAN WAARDEN, 2014 ), and the personal issues of each educator in the classroom. Added to that is the difficulty to include tolerance in the scholarly objectives ( HANSEN, 2013 ).

Some authors defend that co-living with people and ideas should be optional, as to avoid conflict in the educational environment or with families (see ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). Other actions include ignoring, silencing, exemplary punishing, or excluding the intolerant student (see ORLENIUS, 2008 ).

One of the problems of overlooking controversial issues is losing the essence of education, transforming it in training, mere inculcation of knowledge and skills ( CRICK, 1998 ). Another serious problem of not discussing controversies such as prejudice is giving students the impression that this is acceptable or trivial ( KLEIN, 1992 ).

Exemplary punishments, such as the “zero-tolerance policies”3 , generally appear as cheaper, easy, and immediate. Suspensions and expulsions, however, have disastrous effects. In relation to the punished student, there is stigmatization, breaking of the scholarly pace, evasion, denial of rights, likelihood of contact with crime. For the other students, it creates an environment of fear, in which contradictorily the respect for the legal system – that appears arbitrary, exaggerated, irrational, unfair – is lost ( MITCHELL, 2014 ).

Adults and youngsters are placed as opponents, with the first modeling the intolerance of the latter without allowing them to ask why ( RICE, 2009 ). Besides, there is a disproportionate impact in relation to non-white and disabled students. This kind of policy that therefore focuses on the symptom and not the cause appears inefficient ( MITCHELL, 2014 ) and destroys the conditions that favored tolerance in schools ( RICE, 2009 ). To use the terms of Pedahzur (2004) , the use of force (militant route) within something of educational nature (immunized route) causes disastrous effects.

The apparent suppression of conflict, in these measures, will never lead to the suppression of ignorance and therefore of the fear of others. Tolerance creates a sense of unity and belonging to a common world, strengthening connections between individuals beyond their behaviors and opinions. Respect applies to the person and their rights, not their actions ( HEYD, 2008 ).

This goes beyond the classical view of a liberal society in stressing that members cannot only care about the terms separating and keeping them safe from one another, but must as strongly and directly care about what binds them together”. (CREPPEL, 2008, p. 333).

Being together becomes a value. When considering the perspective of others and the search for engagement even when facing conflict, the most fruitful conception of tolerance in an education for democracy is the one of mutuality ( ROSENBLITH; BINDEWALD, 2014 ). For this reason, it is the one adopted in this paper.

However, there is no use in merely offering environments for contact in naïve optimism, without understanding the dynamics of social dominance and intergroup relations ( HARDIN; BANAJI, 2012 ). If the political consciousness begins in childhood, that is also true for prejudice, which manifests early for those who are different ( KLEIN, 1992 ; TITUS, 1998 ).

School represents an opportunity to overcome barbarism, but it is also a promoter of prejudice when it carries the repressive moments of a culture, the division between intellectual and physical work, and the competition contrary to a truly human education ( ANTUNES; ZUIN, 2008 ). In the environment of the school, interaction with difference, when it is not questioned, happens through interpersonal relationships ruled by conflicts, confrontations, and violence ( SALLES; SILVA, 2008 ).

According to Hardin and Banaji (2012) , arguments around discrimination are ruled by an obsolete notion of prejudice, as if it is rooted in ignorance and perpetuated by individuals motivated by hatred. In this way of thinking, the remedy would be to change hearts and minds in an individualized and isolated manner. This vision, incomplete and dangerous, leads to inefficient (or worse) policies. Hardin and Banaji (2012) demonstrate that stereotyping and prejudice do not require animosity, hostility, or even a conscious choice of the individuals. Often prejudice is implicit – involuntary and not controllable – including among the well-intentioned. Thus, it remains stubbornly immune to individual efforts and can only be reduced or reversed through changes in the social environment.

The notion of implicit prejudice points to that any person is capable of holding it, whether or not he knows or wants it. Solutions should focus on identifying the conditions that originate and perpetuate prejudice and stereotyping. For Hardin and Banaji (2012) , it is not a question of “taking away the rotten apple”, because the problem of prejudice is not one of few, but of all. Returning to Creppell (2008) , tolerance as mutuality is a social and political task, not an individual one.

Prejudices and stereotypes have roots in social consensus; they are not random. Within a society, the appreciation, contempt, and beliefs that constrain some and privilege others happen in patterns that systematically oppress the dominated and praise the superiority of the dominant ( HARDIN; BANAJI, 2012 ).

According to Salles and Silva (2008) , it is necessary to pay attention and not neutralize, crystalize, or essentialize diversity and difference. Differences are also socially produced and their perpetuation can consist in a relation of power that does not allow inclusion, generating violence, not only physical but symbolic.

Before tolerating, respecting, and admitting a difference, it is necessary to explain how it is actively produced ( WOODWARD, 2012 ). When the conditions that create prejudice are identified, it is also possible to establish conditions to create egalitarian attitudes, healthy individuation, and mutuality. One of the strategies for this is reinforcing admirable behavior ( HARDIN; BANAJI, 2012 ).

This is a tack for pedagogical policy. Pedagogy that in fact is the very difference, in the opening to another world, instead of a mere reproduction of the world today ( WOODWARD, 2012 ). Thus, education can be fulfilled as a method for progress and social reform, primordial condition for democracy ( DEWEY 1897 [2007]).

Education, political participation of youth, and tolerance: The case of Camara Mirim (Chamber for Kids)

Methodology

The empirical part of this work focuses on the educational program Plenarinho (Little Plenary)4 of the Chamber of Deputies, in the annual action Camara Mirim , which stimulates political participation in children. The analysis of the content comprises over six thousand proposals sent between 2006 and 20165 , built on the comprehension of the context in which they were elaborated. In them, it searches for ideas that were intolerant or dissenting from the juridical order and if there was a numerical increase in recent years, when a greater political polarization was perceived in Brazil, alongside a resurgence of intolerance ( NONATO, 2015 ).

Plenarinho is a program for education for democracy and it integrates the efforts of approximation between the Chamber of Deputies and citizens. With the action Camara Mirim , it emphasizes the importance of laws by means of a simulation of the legislative process. The instructional value is in practice and participation. For that, it relies on partnerships with schools and children’s parliaments in the municipalities. It is a contest for bills open to students from 5thto 9thgrade. The three winners discuss their ideas in the Plenaries of the Chamber, with 400 other children from all over Brazil. From 2006 to 2016, seven children’s projects were adopted by representatives and are now in process.6

The first advantage of studying Camara Mirim is the extension of the database: numerical (six thousand projects), temporal (four presidential mandates), and spatial (contributions from all over Brazil). The second is that the content comes from the voluntary political participation of children and adolescents.

The chosen method, Content Analysis, consists in the selection of the unit of analysis, the coding of the contents, the conceptualization and creation of categories for coding, and evaluating contents ( BABBIE, 2000 ). This paper uses as units the children’s projects. They are used both in quantitative and qualitative approaches. The initial category of intolerance, with elements of hate-speech, was guided by the conception of Gagliardone et al. (2015 , p. 10):

Expressions that advocate incitement to harm (discrimination, hostility, or violence) based upon the target’s being identified with a certain social or demographical group;

Words that are insulting those who exercise power and/or have public visibility;

Antagonisms towards people, and not about abstract ideas (such as political ideologies, faiths, or beliefs).

To this category, were also added the ideas in dissonance with the law. Then, an effort was carried on, to identify the sources of such intolerance (DECLARATION, 1995) that originate and perpetuate prejudice, stereotyping, and relationships of domination ( HARDIN; BANAJI, 2012 ).

Along the analysis of the six thousand projects, it was verified the existence of others in an inverse tack, towards tolerance. Thus, the initially unexpected category of “respect” was added.

Analysis

It is important to contextualize children’s projects, especially the ones holding anti-democratic ideas. The motto of Camara Mirim is: Ideas to improve Brazil. In this intent, the children’s propositions follow two strands: (1) the ones coming from the general towards the particular, referring to practices, persons, and circumstances with which the child does not directly coexist, and in which cases the influence of the media is paramount; and (2) the ones that consider a context that is more immediate to the child, including experiences within families, the school, or the community.

Among the children’s projects, there are isolated examples of fat-shaming, xenophobia, and homophobia (expressions that incite damage on certain targets). Generalization around politicians (“ vagabundos ”, “ safados ”, which could be translated as “bastards” and “jerks”), and the direct attack to some of them (offense on those who exercise power) appear in very few propositions. Prejudice towards persons and groups (directed antagonisms) include the impossibility of rehabilitation of convicts; social hygiene toward drug use; and association of crime to factors such as age, poverty, unemployment, and street situation.

The projects including hate-speech are exceptions. On a wider scale, but still of low significance, are disproportionate and unconstitutional convictions. The elements of the punitive imaginary of some of the children’s projects are curious to note; many of them are derivative from fiction:

suspension of sunbathing and food, putting people on “bread and water”;

separation of inmates, prohibition of visits and contact with the outer world;

compulsory “manual” labor7: public service of cleaning and maintenance (asphalt roadbed), work in “coal mines”, “under the Sun in farming areas”;

use of “very thick chains” and “weights on feet” to avoid escaping; inclusion in a “blacklist”, banishment;

liberation of torture; impossibility of forgiveness; prohibition of the right to defense in heinous crimes; convictions that extend further than the person convicted, “eye for an eye”, “tit-for-tat” (for instance, the execution of a relative);

life sentence (as in “the advanced world”), prohibition of a second trial; use of the electric chair and the guillotine; death and beheading.

Other repressive proposals included irreducibility of conviction, denial of assistance to the convict’s family; extension of conviction: 40, 50, 80, 120 years; end of pardons.

Some projects presented justification for the unconstitutional measures, which reveals a preoccupation with the envisioned problem, some rationality, and even good intentions:

Compulsory work in prisons: Providing for themselves; use of the money meant for convict’s assistance for Bolsa Família 8 (and the surplus for school meals); labor force in the country; end of free time to run crime schemes from inside prisons;

Child labor: Responsibility as young as 14 years old; preparation for life; employability; “the dignifying of man”; contribution to the nation; occupation; distance from drugs.

Reduction of the defense of infancy: full rights and obligations; the right to vote and drive at the age of 16; “most crimes are undertaken by minors”; enticement by adults; rehabilitation so that they work and are productive; retrieval from society of someone with “criminal tendencies”; preserving the youth’s life; stopping crime recidivism; end of impunity; respect to the divine law of free will; prison for 16-year-old fathers who do not pay alimony. Depending on the argument, the defense of infancy is reduced to 7, 10, 12 or 16 years old.

Where does the inspiration for children’s anti-democratic projects come from? In the majority, the projects come from the general towards the particular and reflect a growing wave of violence and intolerance propagated by the media.

Media criminology is attractive because it makes a distinction between “us”, good, vulnerable people, and “them”, the evil mass of different persons, the “enemies” ( ZAFFARONI, 2012 ). Difference is seen as an obstacle, bearable only when it is hierarchized – some rule and others are subjected (ADORNO apud NONATO, 2015 ).

Thus, criminalization is selective towards social class ( BATISTA, 2003 ). Obsessed by the logic of the market, mass media imposes to society a decontextualized way of seeing social problems. Criminal reality is distorted, with its authors summarily pre-judged, generating willingness to punish at any cost ( CALLEGARI; WERMUTH, 2009 ; SILVEIRA, 2010 ; DIAS; DIAS; MENDONÇA, 2013). The prison appears as the only alternative for public security, putting “them” away from social living, from “us” (DIAS; DIAS; MENDONÇA, 2013). Conviction is a sacred rite of conflict solution ( BATISTA, 2003 ).

The media spreads that “the legal system is on the wrong side” ( SILVEIRA, 2010 , p. 31). In that sense, it influences legislators ( ZAFFARONI, 2012 ) to approve laws without the proper time for debate, with violation of the juridical order and the principles of the Democratic Rule of Law ( CALLEGARI; WERMUTH, 2009 ; MASCARENHAS, 2010 ; DIAS; DIAS; MENDONÇA, 2013).

Thus, bills with convictions that are heavier than the offense and that are in disagreement with the Constitution are not exclusive of Camara Mirim ; they are in process in the National Congress, which leaves Plenarinho , in the Chamber of Deputies, in a situation of unique tension.

In the political field, according to Brugnago and Chaia (2015), the dichotomy in citizen participation in Brazil, latent since the ideological centralization of parties with the election of the Labor Party ( Partido dos Trabalhadores , PT) in 2002, explodes in the manifestations of June 2013. From the election’s campaign in 2014, the division between “us” and “them” becomes more evident and the asymmetric polarization between left and right intensifies, with a radicalization of conservative forces, having social networks as enabler devices. In the midst of anti-corruption discourse, widely medialized, the defense of anti-democratic solutions such as military intervention emerged. A characteristic of this movement is a vision of violence as only towards others “who do not belong in the nation” – communists, minorities, users of Bolsa Família (BRUGNAGO; CHAIA, 2015). In the uncertainty of the future propelled by the political, institutional, and economic crisis, people hold on to religious, cultural and moral values, discarding what is different (ADORNO, in NONATO, 2015 ). In 2016, the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff did not smooth the spirits; quite on the contrary.

In the end, it is not necessarily the real and objective conditions that impact intolerance, prejudice, and hatred. Much more claiming are the subjective perceptions of threat ( HALPERIN; PEDAHZUR; CANETTI, 2007 ). But exactly because they are subjective, they can also generate a positive impact. It is the case for legislative advances such as the law combating torture and the Traffic Regulation, fruits of popular adherence amplified by the media ( MASCARENHAS, 2010 ). Add to that the productions that stimulate enlightenment and cooperation (ADORNO apud NONATO, 2015 ).

The study of Camara Mirim revealed this facet: the same media fact that aroused intolerant projects also made opportunities for others who aimed at combating violence, championing respect and the guarantee of rights.

In relation to general pro-tolerance practices, the children’s projects included the guarantee of the right to health, transportation, housing, culture; the fight against racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, and religious, ethnic, and cultural prejudice. There was a preoccupation with equality (such as the end of privileges for politicians and equality of rights in urban and rural areas).

The projects for people focused on members of vulnerable groups, in order to give them autonomy and guarantee their rights. Children do not necessarily identify themselves with those people. They namely cited disabled, obese, albino persons, and people living with HIV; domestic workers; pregnant women, convicts, and their families; child offenders; unemployed persons; low-income individuals; homeless persons; drug users; migratory workers; indigenous people; Northeastern people; quilombolas ; refugees; homosexual persons; elders; retirees; Evangelical people. Besides, it also included politicians (“to combat the prejudice that says they are all corrupt”).

In the other direction, from the particular to the general, there are projects referring to the environment and the protection of infancy, with the dilemmas each child faces in their daily lives. In school, the suggestions include the fight against disrespect (of teachers, students, servants); support aimed at children who are left-handed, stammering, disabled; healthy food suit for the diabetic and the allergic; classical music for concentration; religious freedom; pedagogical material and curricular inclusion of material on disabilities and sexuality (prevention of diseases, early pregnancy, femicide, and prejudice against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transvestite, and transgender – LGBT’s); visits to nursing homes and penitentiaries; end of multi-class schools; equality for students in the rural areas and education for “traveling children” (circus workers, military families, etc.).

Bullying represents the most prevailing practice of intolerance in school contexts. Therefore, many children’s projects aim at extinguishing it. They suggest caring for the victim – and the perpetrator – as well as ample participation and deliberation of students so that they themselves can solve the problem in school meetings, in the creation of groups for conflict mediation, non-violent communication, and education for peace in the curriculum.

The projects regarding infancy asked for celerity in judicial processes involving children; combat to sexual abuse; toys that represent diversity. They posed for the rights of orphans (“not being adopted for work purposes”); and for the social inclusion of farmer workers (“that children do not stop studying to help with the harvest”).

There are personal experiences that contradict the generalized sensation of fear. In these cases, children lived through real threats and maintained their democratic spirits. One example is the following account (translated from Portuguese):

544/2010 [...] Since I was 6 years old, I lived in an institution for rehabilitation of minors [...] and I left there when I was 12 years old. I’ve always had to handle it on my own, obeying orders and rules, and being escorted to school, church, and other places. I’ve always heard that politics was no good and grew up with this idea in my head. [...] children also need to understand, get to know, and experience political questions; and why not in school? [...] today I am the representative for my class.

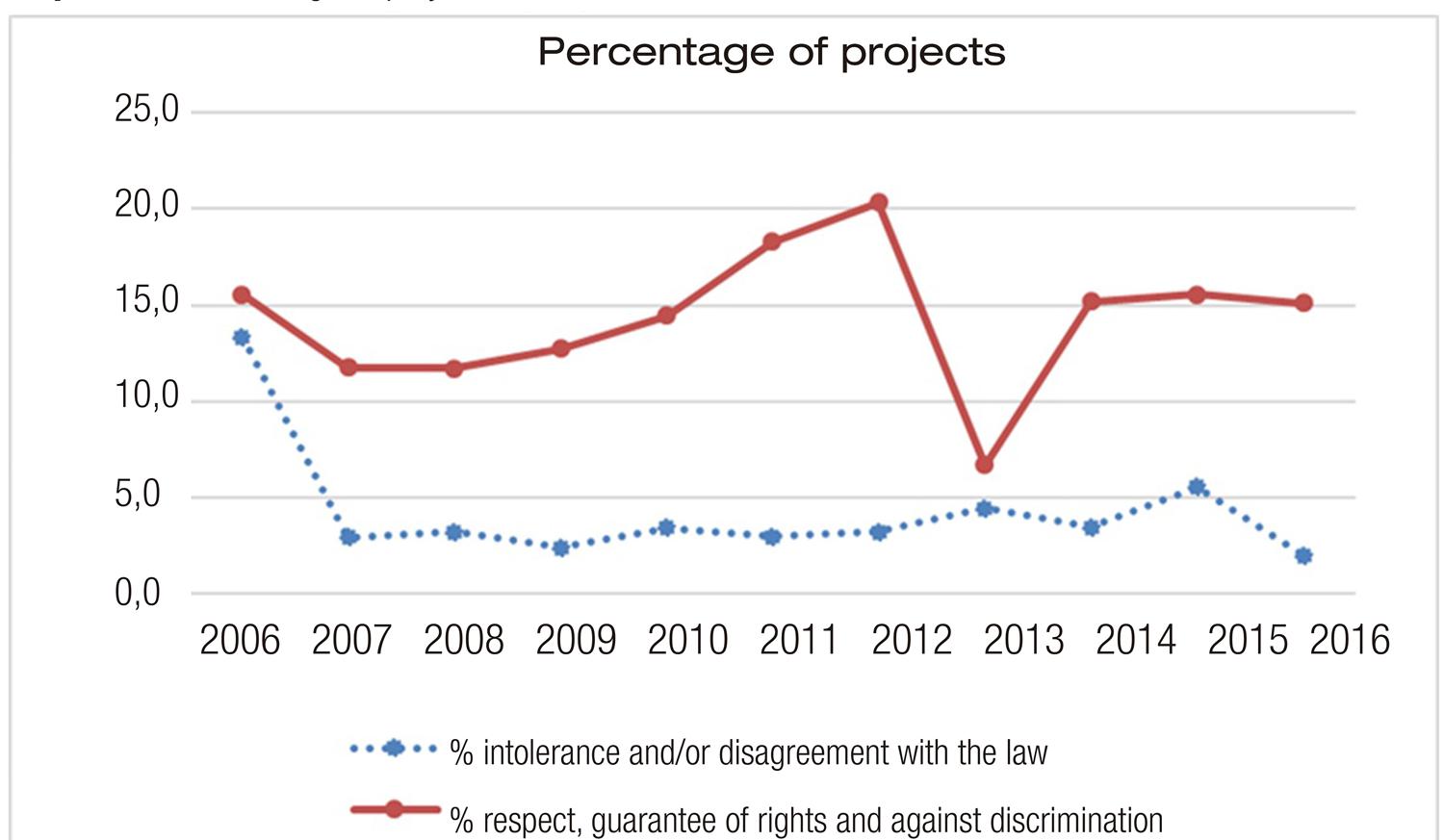

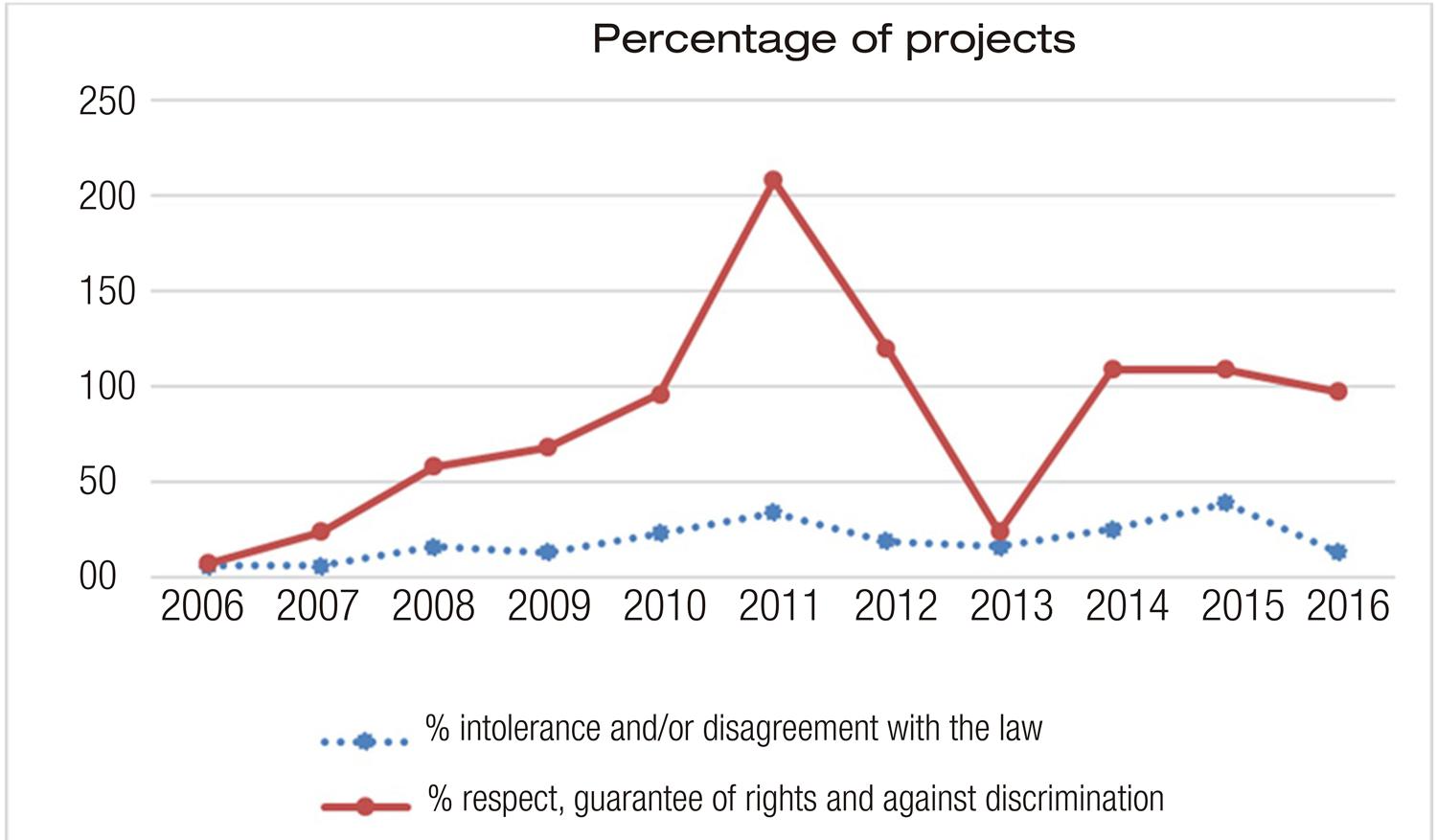

The findings of the research were consolidated in Table 1 and Graphics 1 and 2 , bellow.

Table 1 Quantitative of categories of projects from Camara Mirim9

| Year | Projects sent through the website | Intolerance and/or disagreement with the law | Respect, guarantee of rights and against discrimination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolute number | percentage | absolute number | percentage | ||

| 2006 | 45 | 6 | 13,33 | 7 | 15,56% |

| 2007 | 204 | 6 | 2,94 | 24 | 11,76% |

| 2008 | 495 | 16 | 3,23 | 58 | 11,72% |

| 2009 | 534 | 13 | 2,43 | 68 | 12,73% |

| 2010 | 662 | 23 | 3,45 | 96 | 14,44% |

| 2011 | 1137 | 34 | 2,99 | 208 | 18,29% |

| 2012 | 590 | 19 | 3,22 | 120 | 20,34% |

| 2013 | 358 | 16 | 4,46 | 24 | 6,70% |

| 2014 | 718 | 25 | 3,48 | 109 | 15,18% |

| 2015 | 701 | 39 | 5,56 | 109 | 15,55% |

| 2016 | 643 | 13 | 2,02 | 97 | 15,09% |

| Average | 553,64 | 19,09 | 3,44 | 83,64 | 15,11% |

Source: Elaborated by the author.

The results of the analysis point to the low significance of the occurrence of non-democratic ideas, which maintained the same level within 10 years. On average, less than 1% hold manifestations of intolerance and 3% refer to unconstitutional punishments, adding up to 3,44%. The atmosphere of hate that usually surrounds political elections ( GAGLIARDONE et al. 2015 ) did not affect the numbers10 , 11 in this category.

The most interesting finding, however, is in the considerable number of propositions aiming precisely at fighting intolerance (15% on average). Following, Charts 1 to 312 compare examples of both categories (translated from Portuguese).

Chart 1 – Religious argument – fight against crime

| Intolerance | Respect |

|---|---|

| 68/2008 [...]. I would not invest in new JAILS, for the place of a man convicted for committing a crime is the CEMETERY. Jesus came to the Earth and was spat on. [...] those outcasts [...] committed crimes Jesus did not and he suffered much more for these kinds of people. ARRESTED? NO, highly dangerous perpetrators should be KILLED and BEHEADED. [...]. I am fit to be a politician, this is why I am here [...]. as a DEPUTY I would do all of that and much more for this Brazilian society that deserves so much good. | 121/2010 – In his visit to Brazil, Pope Francis said [...] that [...] we live in a world of “ globalization of indifference ” [...]. The school needs to act to form more solidary people. This does not take away the Government’s responsibility to guarantee citizenship rights to the people. But it certainly helps form better people [who] will help reduce crime [...] and end corruption [...]. |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the researched data.

Chart 2 – Politics

| Intolerance – scapegoating | Respect – shared responsibility |

|---|---|

| 95/2015 [...] Dilma and her comrades from PT have been stealing the money from people who work and fight hard to get it [...]. I don’t think the president [...] cares [...]. Rape and sexual violence; theft; stabbings [...] the culprits do it and know that the next day they’ll be free. | 7/2013 [...] Politics will be the name of an online social network in which the names and e-mails of all Brazilian politicians will be available. [...] Every person will [...] become “political” in this social network [...] being able to create laws, projects, vote for politicians [...] and talk to politicians. |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the researched data.

Chart 3 – Research arguments – defense of infancy

| Intolerance | Respect |

|---|---|

| 208/2010 [...]. Here I state my outrage [...] with the neglect of minors in this country, we have [...] an outdated law . [...] that the defense of infancy goes from 18 to 16 years of age, [...] at 16 one can drive [...] vote and chose the President of the Country [...] At 16 years old young people kill, steal, rape, and sell drugs. [...] it is not fair that young people who study, work, are responsible, respects the law, should pay [...] by being stolen, violated, or murdered by minors which in many cases did not even commit the crime , but take on it to clear for adults, [...] are not even held and on the following day to the crime are already found on the streets. [...] A child should be treated as a child, but a criminal should be treated as such , may they be 10 or 100 years old. [...] JEAN PIAGET [...] psychologist who studied the world of the child in depth, [...] said that a child from 7 to 11 years of age is capable of organizing socially, usually in groups , [...] can comprehend rules, being faithful to those and able to establish commitments. | 378/2010 [...] statistics show that only 0.2% of teenagers [...] are serving socio-educational measures in Brazil for having committed crimes. [...] prove that criminality is not greater in this age. [...] The discussion on the defense of infancy deviates the focus from the actual causes [...] of violence, placing the blame in the teenager. [...] in Brazil, violence is deeply connected to [...] social inequality (different from poverty!), social exclusion, impunity (laws [...] are not followed, regardless of how “light” or “heavy”), faults in education , be it in the family and/or school [...] in values or ethical behavior, and [...] exacerbated cultural processes [...] such as individualism, consumerism, and a culture of indulgence. [...] Emotional reactions motivated by “bad news” spread by the media. [...] we have a natural feeling of outrage [...]. only 2 in every 1000 teenagers get involved in crimes , we can ponder this outrage and not generalize it [...] barbaric crimes, although shocking, are isolated cases. [...] extremely rigid regimens in many countries [...] did not manage to reduce or solve [...] violence . [...] in Brazil it is very common to see injustice and prejudice in law enforcement. Poor and back people fill up the prisons [...]. If laws were stricter, [...] it would affect [...] the most excluded sector of society. [...] hardly a son of the elite will suffer the same punishment. |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the researched data.

In these examples, the key elements of the current Brazilian scenario are present: the growth of religion in politics, the anti-PT movement (BRUGNAGO; CHAIA, 2015), the debate surrounding the defense of infancy ( NONATO, 2015 ). The charts distinguish the segregating speech of intolerance (“us” x “them”, typical of media criminology, and political radicalization that is the backdrop for this attitude) and the empathetic and collective discourse befitting respect and the conception of tolerance as mutuality. The deepening of this analysis is compelling and could be the object of future works.

Conclusions

From the literature, one surmises that what should or should not be tolerated appears in the democratic process; it is not predetermined. However, some aspects are consensual: one should not cause damage to others; one should not tolerate intolerance to multiplicity and to the very rules of the democratic arena.

In the heart of education for democracy, the teaching of tolerance is held as an important instrument for the development of society and conviviality filled with information and creativity. The concept of tolerance that is most promising for education, and therefore adopted in the present paper, is that of mutuality. The aim is to create, recycle , and maintain the willingness to listen and respect, the “will to relationship” ( CREPPELL, 2008 ), holding the right to disagree.

The educational environment should not be a mirror of society or the adult world. The idea is to create a model of a place, an ideal laboratory in which attitudes of intolerance are worked on in its origins, in a safe way, contextualized, and with the clear objective of finding joint solutions, even (or mainly) in conflict.

Political institutions can also be educational spaces, as shows the example of the Parliament, with initiatives for children’s political participation. One of them is the Plenarinho Program, from the Chamber of Deputies. In its annual action Camara Mirim , since 2006, it brings children and adolescents to participate in the legislative process with the creation, discussion, and voting of bills of their own making. When encountering children’s manifestations of intolerance or disagreement with the law, Plenarinho limited itself to registering and ignoring them.

This research propitiated the systematization of children’s projects and now provides strategies to work with them, not censoring, but inviting the authors to reflect on the origins of their own ideas. Three complementary approaches can be useful for schools and other institutions and initiatives with participatory children’s projects: (1) how to deal with disagreement on laws/norms; (2) how to identify the causes of intolerance; and (3) how to encourage mutuality.

(1) It is important that children understand the need to respect the rule of law in any social order. At the same time, it is also necessary to differentiate law and justice. Laws can be questioned and changed – as long as citizens do it pacifically and responsibly, and education for democracy can help acquire political skills ( CRICK, 1998 ).

(2) Intolerance comes from the perception of fear, which contains a protective aspect. In fact, even with some proposals of highly repressive level, paradoxically, the candidates for young parliamentarians showed good intentions. They offered justifications for radical solutions in the fight against threats to infancy (for example, death penalty for pedophiles).

However, the media (including political propaganda) has contributed to creating exaggerated perceptions of fear and violence, fostering hate expressions. The strategy is not in stopping children from accessing the media, but giving them the ability to identify, question, and tackle hate content, through media literacy in an education for democracy ( GAGLIARDONE et al., 2015 ). It is also necessary to channel their good intentions in a more reflexive, tolerant, and democratic direction.

In Camara Mirim , this is exemplarily shown: the same fact generated diametrically opposed discourses – one followed the media criminology beliefs; the other searched for empathetic solutions in the root of the problem, with immunizing effects (according to PEDAHZUR, 2004 ).

In ten years, the average of children’s projects containing intolerance or in disagreement with Brazilian law was of less than 4%, while the average of projects in defense of rights and against discrimination was greater than 15%. The highlight goes to the 96% of projects not manifesting hate speech, despite the growing wave of anti-democratic messages in the media and social networks – and the Chamber of Deputies itself.

(3) Instead of a top-down perspective, from the adults to the children, to deal with hate speech and intolerance that comes from the political participation of children, the answers must be sought after within the very results of such participation. The right to a voice allows for recognizing the feelings of children in such a way that they become the origin and the basis for educational actions. That is mutuality – among themselves and between them and their educators, the researchers, congresspersons, and other adults.

The projects of Camara Mirim already claim for more participation (committees, boards, children’s parliaments, votes, debate arenas, development of leadership) and for teaching of politics, law, and citizenship. Instead of denying conflict, they admit it; instead of segregating it, they expose themselves to it; instead of eradicating it (considering it would be impossible), they aim to understand it. In this way, paradoxes are no longer excluding dichotomies and become complementary.

Even if (very few) children’s projects did manifest discriminatory characters, these are opportunities to open up to critical thinking and debating. In these cases, for the authors, more than recommendations of literature, the (admirable) solutions of their own peers in Camara Mirim are to be observed. Solutions that also apply to settle intolerance between adults.

REFERENCES

ALMOND, Brenda. Education for tolerance: cultural difference and family values. Journal of Moral Education, London, v. 39, n. 2, p. 131-143, Jun. 2010 . [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Deborah Christina; ZUIN, Antônio Álvaro Soares. Do bullying ao preconceito: os desafios da barbárie à educação. Psicologia & Sociedade, Belo Horizonte, v. 20, n. 1, p. 33-42, 2008 . [ Links ]

BABBIE, Earl. Fundamentos de la investigación social. Mexico, DF: Thompson, 2000 . [ Links ]

BATISTA, Nilo. Mídia e sistema penal no capitalismo tardio. Biblioteca On-line de Ciências da Comunicação, Rio de Janeiro, 2003. Disponível em: < http://www.bocc.uff.br/pag/batista-nilo-midia-sistema-penal.pdf> . Acesso em: 16 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

BRUGNAGO, Fabrício; CHAIA, Vera. A nova polarização política nas eleições de 2014: radicalização ideológica da direita no mundo contemporâneo do Facebook. Aurora, São Paulo, v. 7, n. 21, p. 99-129, out. 2014 - jan.2015. [ Links ]

CABRAL, Margarida Olazabal. Democracia e partidos políticos anti-democráticos. Revista do Ministério Público, Lisboa, n. 59, p. 32-56, jul./set. 1994 . [ Links ]

CALLEGARI, André Luis; WERMUTH, Maiquel Ângelo Dezordi. “Deu no jornal”: notas sobre a contribuição da mídia para a (ir)racionalidade da produção legislativa no bojo do processo de expansão do direito penal. Revista Liberdades, São Paulo, n. 2, p. 56-77, set./dez. 2009 . [ Links ]

CARTER, Ian. Are toleration and respect compatible? Journal of Applied Philosophy, Oxford, v. 30, n. 3, p. 195-208, 2013 . [ Links ]

CEVA, Emanuela. Why toleration is not the appropriate response to dissenting minorities’ claims. European Journal of Philosophy, Oxford, v. 23, n. 3, p. 633-651, 2012 . [ Links ]

COSTANDIUS, Elmarie; ROSOCHACKI, Sophia. Educating for a plural democracy and citizenship: a report on practice. Perspectives in Education, Bloemfontein, v. 30, n. 3, p. 13-20, set. 2012 . [ Links ]

CREPPELL, Ingrid. Toleration, politics, and the role of mutuality. Nomos, New York, v. 48, p. 315-359, 2008 . [ Links ]

CRICK, Bernard (Org.). Education for citizenship and the teaching of democracy in schools: final report of the Advisory Group on Citizenship. London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1998 . [ Links ]

DECLARAÇÃO de princípios sobre a tolerância. Brasília, DF: Unesco, 1997. Aprovada pela conferência geral da Unesco em sua 28. Reunião, Paris, 16 de novembro de 1996. Disponível em: < https://www.oas.org/dil/port/1995%20Declara%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20de%20Princ%C3%ADpios%20sobre%20a%20Toler%C3%A2ncia%20da%20UNESCO.pdf> . Acesso em: 11 nov. 2019. [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. My pedagogic creed. The School Journal, New York, v. 54, n. 3, p. 77-80, Jan. 16, 1897 [2007]. [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. A democracia é radical. Common Sense, Yale, 6 jan. 1937 . [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. Democracia criativa: a tarefa diante de nós. Progressive Education Booklet, Columbus, n. 14, p. 1-8, 1939. Publicado inicialmente em John Dewey and the Promise of America, Disponível em: < https://www.scribd.com/document/188468424/DEWEY-John-1939-Democracia-criativa-A-tarefa-diante-de-nos> . Acesso em: 11 nov. 2019. [ Links ]

DIAS, Fábio Freitas; DIAS, Felipe da Veiga; MENDONÇA, Tábata Cassenote. Criminologia midiática e a seletividade do sistema penal. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE DIREITO E CONTEMPORANEIDADE, 2013, Santa Maria. Anais eletrônicos… 2. ed. Santa Maria: UFSM, 2013. Disponível em < http://coral.ufsm.br/congressodireito/anais/2013/3-7.pdf > Acesso: 16 jul. 2017. [ Links ]

DIAS, Teresa Silva; MENEZES, Isabel. Children and adolescents as political actors: collective visions of politics and citizenship. Journal of Moral Education, London, v. 43, n. 3, p. 250-268, 2014 . [ Links ]

FORST, Rainer. Toleration. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford, 2017. Publicada primeiramente em 23 fev. 2007. [ Links ]

FORST, Rainer. Toleration and democracy. Journal of Social Philosophy, Medford, v. 45, n. 1, p. 65-75, 2014 . [ Links ]

FORST, Rainer. Toleration, justice and reason. In: MCKINNON, Catriona; CASTIGLIONE, Dario (Ed.). The culture of toleration in diverse societies: reasonable tolerance. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003 . p. 71-85. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. 17. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987 . [ Links ]

GAGLIARDONE, Iginio et al. Countering online hate speech. Paris: Unesco, 2015 . [ Links ]

HALPERIN, Eran; PEDAHZUR, Ami; CANETTI-NISIM, Daphna. Psychoeconomic approaches to the study of hostile attitudes toward minority groups: a study among Israeli Jews. Social Science Quarterly, Medford, v. 88, n. 1, p. 177-198, mar. 2007 . [ Links ]

HANSEN, Ole Henrik Borchgrevink. Promoting classical tolerance in public education: what should we do with the objection condition? Ethics and Education, London, v. 8, n. 1, p. 65-76, 2013 . [ Links ]

HARDIN, Curtis D.; BANAJI, Mahzarin R. The nature of implicit prejudice: implications for personal and public policy. In: SHAFIR, Eldar (ed.) The behavioral foundations of public policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012 . p. 13-31. [ Links ]

HEYD, David. Is toleration a political virtue?. In: WILLIAMS, Melissa; WALDRON, Jeremy. Toleration and its limits. Nomos XLVIII. New York: New York University Press, 2008 . p. 171-194. [ Links ]

KLEIN, Tracy E. Teaching tolerance: prejudice awareness and reduction in secondary schools. 1992. (Master’s Thesis) – Dominican College, San Rafael, California, 1992. [ Links ]

KOVACS, Philip. Education for Democracy: It Is Not an Issue of Dare; It Is an Issue of Can. Teacher Education Quarterly, San Francisco /USA, p. 9-23, 2009 . [ Links ]

LOEWENSTEIN, Karl. Militant democracy and fundamental rights. The American Political Science Review, Cambridge, v. 31, n. 3, p. 417-432, 1937 . [ Links ]

MASCARENHAS, Oacir Silva. A influência da mídia na produção legislativa penal brasileira. Âmbito Jurídico, Rio Grande, v. 13, n. 83, dez 2010 . [ Links ]

MCKINNON, Catriona; CASTIGLIONE, Dario (Ed.). The culture of toleration in diverse societies: reasonable tolerance. Mancherster: Manchester University Press, 2003 . [ Links ]

MENEGUIN, Ana Marusia Pinheiro Lima. Plenarinho: novos paradigmas para novas gerações. E-Legis, Brasília, DF, n. 22, p. 99-128, jan./abr. 2017 . [ Links ]

MILL, John Stuart. On liberty. Kitchener: Batoche Books, 2001. Publicação original 1859. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, David. Zero tolerance policies: criminalizing childhood and disenfranchising the next generation of citizens. Washington University Law Review, Washington, DC, v. 92, n. 2, p. 271-323, 2014 . [ Links ]

MONTEIRO, Alessandra Pearce de Carvalho. Democracia militante na atualidade: o banimento dos novos partidos políticos antidemocráticos na Europa. 2015. 131 f. Dissertação (Especialização) – Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, 2015. [ Links ]

NIESEN, Peter. Anti-extremism, negative republicanism, civic society: three paradigms for banning political parties. German Law Journal, Lexington, v. 3, n. 7, 2002 . [ Links ]

NONATO, Cláudia. Sérgio Adorno: reflexões sobre a violência e a intolerância na sociedade brasileira. Comunicação & Educação, São Paulo, v. 20, n. 2, p. 93-100, jul./dez 2015 . [ Links ]

ORLENIUS, Kennert. Tolerance of intolerance: values and virtues at stake in education. Journal of Moral Education, London, v. 37, n. 4, p. 467-484, dez. 2008 . [ Links ]

PEDAHZUR, Ami. The defending democracy and the extreme right: a comparative analysis. In: EATWELL, Roger; MUDDE, Cas (Ed.). Western democracies and the new extreme right challenge. Oxon: Routledge, 2004 . p. 108-132. [ Links ]

PLENARINHO. Câmara dos Deputados. Disponível em: < www.plenarinho.leg.br > Acesso: 03 jan. 2017 . [ Links ]

POPPER, Karl R. The open society and its enemies. v. 1. London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1966 . [ Links ]

RICE, Suzanne. Education for toleration in an era of zero tolerance school policies: a deweyan analysis. Educational Studies, London, v. 45, n. 6, p. 556-571, 2009 . [ Links ]

ROSENBLITH, Suzanne; BINDEWALD, Benjamin. Between mere tolerance and robust respect: mutuality as a basis for civic education in pluralist democracies. Educational Theory, Illinois, v. 64, n. 6, p. 589-606, 2014 . [ Links ]

SALLES, Leila Maria Ferreira; SILVA, Joyce Mary Adam de Paula. Diferenças, preconceitos e violência no âmbito escolar: algumas reflexões. Cadernos de Educação, Pelotas, n. 30, p. 149-166, jan./jun. 2008 . [ Links ]

SAULIUS, Tomas. What is “tolerance” and “tolerance education”? Philosophical Perspectives, Kaunas, v. 2, n. 89, p. 49-56, 2013 . [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Fabiano Augusto Martins. A grande mídia e a produção legislativa em matéria penal. Senatus, Brasília, DF, v. 8, n. 2, p. 30-36, out. 2010 . [ Links ]

TITUS, Dale. Teaching tolerance and appreciation for diversity: applying the research on prejudice reduction. In: ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR SUPERVISION AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT, 53 rd ., 1998, San Antonio. Anais… San Antonio, 1998. p. 21-24. [ Links ]

VAN WAARDEN, Betto. Teaching for toleration in liberal democracy. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE, INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND PUBLIC POLICY, 10., 2014, Jerusalem. Annual… Jerusalem: [s. n.], 2014. p. 1-22. [ Links ]

WALDRON, Jeremy. Toleration and reasonableness. In: MCKINNON, Catriona; CASTIGLIONE, Dario (Ed.). The culture of toleration in diverse societies: reasonable tolerance. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003 . p. 13-37. [ Links ]

WERLE, Denilson. Os limites da tolerância: uma questão da justiça e da democracia. In: COLÓQUIO INTERNACIONAL DE TEORIA POLÍTICA E TEORIA POLÍTICA CONTEMPORÂNEA, 2., 2012, São Paulo. Anais... São Paulo: USP, 2012. p. 1-37. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, Bernard. Toleration: an impossible virtue? In: HEYD, David (Ed.). Toleration: an elusive virtue. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996 . p. 18-27. [ Links ]

WOODWARD, Kathryn. Identidade e diferença: uma introdução teórica e conceitual. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da (Org.). Identidade e diferença: a perspectiva dos estudos culturais. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012 . p. 7-72. [ Links ]

ZAFFARONI, Eugenio Raúl. A palavra dos mortos: conferências de criminologia cautelar. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2012 . [ Links ]

3- Policies adopted in the United States after mass shootings in schools. Harsh punishments are enforced independently on the severity of the infraction ( MITCHELL, 2014 ).

4- For a comprehensive description and analysis of the Plenarinho Program, see Meneguin (2017) .

5- According to regulation, the children’s projects are public and accessible through the Plenarinho’s website. Here, the names of proponents were not disclosed.

6- For more details on the children’s projects, see Meneguin (2017) .

7- Work that, seen as punishment (example: “they will lead the life of a street cleaner”), denotes prejudice.

8- Bolsa Família is a conditional cash transfer program introduced by the Government of Brazil in 2003. Under this program, poor families receive cash transfers on the condition that they, for example, send their children to school and ensure they are vaccinated.

10- In the ten years of this research, Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT - Workers’ Party) was in the Presidency of the Republic. In 2017, it was Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB - Brazilian Democratic Movement). Future studies can verify if this alters the pattern of children’s projects.projects.

11- 2006 falls off the curve, but the total of projects is lower than the average and does not allow inferences.

* Translator: Thays Ruas Prado.

Received: August 26, 2018; Revised: February 22, 2019; Accepted: April 23, 2019

texto em

texto em