Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 13-Jan-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046215311

SECTION: ARTICLES

Middle school, youth work, and hegemony in neo-developmentist Argentina: a structural approach

1- Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (UNICEN), Buenos Aires, Argentina. Contacto: marcelaleivas81@gmail.com.

The following article presents a series of findings that arise from statistical analysis of enrollment data originated in Argentina’s Secondary Education system, which is then linked to youth employment indicators for the same period. Those are interpreted making use of theoretical approaches provided by critical currents of Sociology of Education. By recovering the analysis of the Argentinian State as a neo-developmental government in the post-2001 period, and considering its characteristics from a Gramscian perspective, we try to interpret the educational system as a tool in the configuration of hegemony processes. For some authors those processes develop a weak hegemony, due to a government that adapts pragmatically to juncture demands, and ends up reproducing the management of contradictions which are also expressed, as stated in the conclusions, in Education. Therefore, the reader is invited to deepen the analysis of the educational system from a critical perspective given by the Sociology of Education, specifically in its contributions on educational inequality. This perspective allows us to establish the relationship between the hegemony of State, hegemony and education, which seems disconnected from the education system according to several analysis. This will be achieved by observing the structural behavior of population in age to formally attend secondary school: the youth.

Key words: Middle school; Youth work; Sociology of education; Hegemony

Este artículo presenta una serie de hallazgos que surgen del análisis de datos estadísticos sobre matrícula en la Educación Secundaria argentina, datos que son puestos en relación con indicadores sobre empleo joven para el mismo período. Los mismos se interpretan a la luz de los enfoques teóricos de las corrientes críticas de la Sociología de la Educación. A partir de recuperar análisis del Estado argentino para el período pos 2001, como un gobierno neodesarrollista, y de considerar sus características desde perspectivas gramscianas, se intenta interpretar al sistema educativo en tanto herramienta en la configuración de procesos de hegemonía. Procesos que para algunos autores configuran una hegemonía debil, debido a estar conducida por un gobierno que se adapta pragmáticamente a las exigencias de la coyuntura, y que termina reproduciendo una gestión de contradicciones las cuales se expresan, como se plantea en las conclusiones, también en la educación. Siendo así, se invita al lector a profundizar en el análisis del sistema educativo desde una perspectiva crítica proveniente de la Sociología de la Educación. Ésta permite vincular aquello que en numerosos análisis sobre el sistema educativo aparece desvinculadado, la relación Estado-hegemonía-educación. En este caso lo hace observando el comportamiento estructural de la población en edad formal de asistir a la educación secundaria: la juventud.

Palabras-clave: Escuela media; Trabajo joven; Sociología de la educación; Hegemonía

Presentation

This work uses as a reference the research entitled “Educational Inequality in Secondary Education Mandatory Contexts. A study about enrollment and internal efficiency indicators in the country and Buenos Aires province, during the 2001/2015 period”, which would accredit the Educational Sciences PhD of its authors.

On this occasion, an analysis of the macrostructural relationship between Middle Education, the adolescent work and the forms of government from 2001 until 2015 is presented. The young population of the country and Buenos Aires province of age to formally attend secondary level – between 12 and 17 years – was taken as a reference for this analysis.

After recovering some findings about the intercensal behavior of high-school age population, a crosscheck was made using youth employment data, which was later interpreted using critical perspectives of the Sociology of Education. This resulted in a series of findings which enabled approximations and hypotheses of what is the institutionally predetermined destiny for the country’s youth, whether the educational institution or the labor market, and what are the relationships between those destinies and the configuration of government forms deployed from 2001 onwards.

Below, the reader will find four sections. The first one presents the interpretative framework from which all the data is theoretically read, the second one includes a brief reference to the governmental period post 2001, the third section contains specific presentation of statistical data and the final section details the conclusions established by relating the educational, state, and youth aspects from the interpretation framework presented at the beginning.

Interpretive framework. Education and youth work according to the critical currents of the Sociology of Education

As many investigations prove, in the national-capitalist states, the possibilities for the youth to transit through social spaces are pre-established. There is a predetermined path, the (formal) educational system. There, the entire population aged 3 to 17 years is ranked and classified, and then embarks on a second predefined course, the labor market. The school plays a fundamental role in the construction of the “social division of labor”, its role as distributor of titles (legitimate knowledge) selects the population within a certain social space and with a certain labor access.

The relationship between the educational system and the labor market is the empirical evidence of the regulation power which emanates from unequal access to education. The educational system does not only have the capacity to rank and regulate, but also to legitimize this hierarchy and order. That is, to be the device which produces social consensus.

Already in the early twentieth century, Antonio Gramsci assured that school is, along with church, one of the material structures of ideology; its pedagogical practice is a practice of hegemony. It is currently the main institution that reproduces the legitimate distribution of cultural capital, and with it, the reproduction of the social space structure, its task is to order and institute a social difference of rank, of classification, a definitory original relation ( BOURDIEU, 2008 , p. 108-113).

According to Gramsci, hegemony is a form of social consensus organization, different from what the notion of domination, as coercion, could mean. This perspective raises the existence of a synthesis between consensus and coercion, of political direction of a society whose procedure can be determined through the conformation of an ideological, cultural and moral consensus promoted from a social class to the whole civil society. (Corbiere Emilio, in Torcuato Di Tella Dictionary ).

The dynamic performance of consensus and coercion allows hegemony to become a political practice that articulates fragments of the social totality ( LACLAU, 1987 ), and enables the construction of ideological and cultural consensus, responding to the strategy of a social group that aims at turning their interests into the interest of all people. Thus, the hegemony refers to a political relationship and, therefore, an unequal relationship between social groups. This fact is, among others, the one that prevents the immediate irruption of contradictions that are configured in the economic base of the social structure, because the “discovery” of the main contradiction in the economic-social realm does not imply finding the same contradiction, simultaneously, in the political-social realm (Protentiero JC 1972).

The Educational System, in its role of articulating the hegemony system, occupies a super structural place in the social order, it articulates both in institutional and social dimensions the political society with civil society. Also, it succeeds, along with an array of private institutions, in holding back the “structural” conflict situation, becoming a shield against the immediate irruption of the economic element.

According to Adriana Puiggrós, the school system, at least in Latin America, contains all public and private institutions whose explicit purpose is to educate. The school system can be located in the interrelation between the political society and civil society, becoming a battlefield in which the dispute for hegemony is very intense, fundamentally because the State needs to keep control of the processes that take place there (PUIGGRÓS, 1980, p. 32). The educational system constructs hegemony from a rationality that adapts consensus and coercion. Namely, it absorbs “everything that is a simple differential particularity, and suppresses those elements that tend to transform a particularity into a symbol of antagonism”. ( PUIGGROS, 1990 , p. 255).

Within our social organization, the school has the capacity to determine, in a political and ideological sense, the production and reproduction of social relations. This capacity of determination – or imposition – has been configured historically from the educational institutions, institutionalized as legitimate spaces for the production and reproduction of the Cultural Social Capital. They articulate a political relationship and, therefore, hegemonic, between the political society and civil society,

[...] manages to impose meanings and to impose them as legitimate by concealing the power relations which are the basis of its force, adds its own especially symbolic force to those power relations. ( BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 1972 , p. 44).

However, regarding the characteristics taken by this articulation, Adriana Puiggrós presents a hypothesis in which she refers to all Latin America. According to her, this articulation implies the dissociation of the educational process from the social whole to which it belongs.

Namely,

[...] socio-pedagogy is constituted by imported models that dissociate the educational process from the social whole in which this process is inserted, and shreds it by transforming particular aspects into isolated facts. The object is reconstructed by the sum of the fragments, and partial relations are then lost as an expression of the totality. (...) The relationship Man and Society (...) will try to classify intelligence, creativity, ways of thinking on a scale that justifies marginalization. (...) Education becomes ahistorical and educational processes freeze, adapting to functionalist categories. ( PUIGGRÓS, 1980 , p. 16-17).

If such was the case, we would be in the presence of an educational system that forges the practices of its institutional agents by establishing partial relationships with the social totality, making one part of reality invisible and showing another. Such functionalist thinking explains school failure as a problem of individual nature, whereas social issue of this nature is explained by broader and more complex structural social processes (see KAPLAN; LLOMOVATE, 2005 ).

In general terms, social theory has proposed that this process is established by naturalizing the existing contradiction between practice and its meaning. For instance, in discourses the State is presented highlighting individual freedom, but it is actually supported by collective social processes such as economic and cultural production.

In On the Jewish Question, Marx puts it this way:

Where the political state has attained to its full development, man leads, not only in thought, in consciousness, but in reality, in life, a double existence—celestial and terrestrial. He lives in the political community, where he regards himself as a communal being, and in civil society where he acts simply as a private individual. ( MARX, 1992 , p. 55).

During the 1970s, critical authors of the educational field discovered this mechanism, by identifying that school appears spontaneously as a unit, but actually school is not the same for all. The school can be presented in one way and operate in a different one, thanks to a “fetishization” mechanism.

This conception has allowed the development of critical perspectives within the field of the Sociology of Education, mainly based on producing knowledge about the educational inequality phenomena. For critical approaches of Sociology of Education – those belonging to Theories of Reproduction and / or the Theories of Resistance – the “educational inequality” phenomena actually represents a crisis of education as a knowledge redistributive mechanism.

Boudelot and Establet, well-known authors of the Reproductivist Theories, consider that school “divides” the school population in two quantitatively unequal masses, distributed in two types of schooling: “a long schooling reserved for the minority and a short schooling for the majority “( BOUDELOT; ESTABLET, 1971 , p. 7). They prove, through their research, that there are juxtaposed and different school “networks” within the school.

According to them,

[...] far from being “unevenly” schooled in one school, these two great masses are actually divided into two separate school ramifications. We establish that these two ramifications are: hermetic, heterogeneous by their ideological contents and the inculcation forms in which these contents are made, opposed to what has been called their purpose. Clearly, they lead to tendentially antagonistic positions in social division of labor; heterogeneous by their recruitment, they are directed massively to antagonistic social classes. ( BOUDELOT; ESTABLET, 1971 , p. 41).

As announced above, also Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron (1972) identify the same process of fetishization, specifically in school, and conceptualize it as “symbolic violence”. According to the authors, the school system is a “relatively autonomous institution, claiming the monopoly of the legitimate exercise of symbolic violence” ( BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 1972 , p. 108) which, translated into scholarly work and pedagogical authority, legitimates differential, arbitrary processes, achieving “to serve, in the guise of neutrality, groups or classes that reproduce cultural arbitrariness” ( BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 1972 , p. 108).

Thus, the “symbolic violence” is

Every power to exert symbolic violence, i.e. every power which manages to impose meanings and to impose them as legitimate by concealing the power relations which are the basis of its force, adds its own especially symbolic force to those power relations. ( BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 1972 , p. 44).

In the Argentine academic production these contributions are taken and made complex. Since the 1990s, research in the Sociology of National Education field, starting from the conception of hegemony that this research also intends to integrate, has contributed to a perspective called “neo-Gramscian”, which “emphasizes the moment of the resistance and tries to recover the actors involved in the educational process as subjects of historical action” ( KAPLAN, 1997 , p. 53-54).

These theoretical reflections have allowed academic productions in Argentina to incorporate and configure into their research the valuable category of “educational trajectories”. Its contribution lies in enabling to visualize differential routes through the system, considering those educational areas through which students’ journeys and their biographies are constituted. (...) These educational trajectories refer to all conditioning factors (...) that affect the path of subjects through institutions (BRACCI; GABBAI, 2013, p. 34).

Thus, the “differential historical time” variable gets incorporated – in addition to the hegemonically established – into the analysis of the unequal relationship between the State and population. According to Claudia Bracci and Inés Gabbai (2009), this conception of lived time considers the “assignment of people to social positions as a process related to the moment of their lives but, at the same time, with a certain perspective of historical time” (MAYER, 1987, p. 51, cited by DOMBOIS, 1998 , p. 449).

Based on these conceptualizations about the implication of the educational system in the social order, this article proposes to reason about how education, youth, and work are related in a determined historical context; in this case, the post-2001 period in Argentina. A context characterized by the reconfiguration of the hegemony process, a process called by some authors as “neo-developmentalist”, which implied, as we will see below, some political and institutional rearrangement of the national state, which necessarily affected the educational system.

A brief reference about the hegemonic reconfiguration of the Argentine State for the post-2001 years

In order to understand, even in general terms, the complexity of this State recompositing process in the post-2001 period, it is necessary to refer to the beginning of a process, a process of destruction, of weakening.

It was during the 1990s that a process of State Reform was carried out, legally framed in the State Reform Law N° 23,696 of 1989. This law authorized the State to transform its daily dynamics and promote “privatization”, “deregulation” and “decentralization” mechanisms, which affected the entire state bureaucracy, including the education bureaucracy. “Privatization” represented a central aspect of the capital and State restructuring in the 1990s. It meant the opening of new areas for capitalist accumulation, by the withdrawal of the State, in a very varied range of goods and services, in order to refocus and enhance it in other functions. The “deregulation” meant a policy where the State stopped arbitrating aspects related to the influence of private capital, that is, not regulating its operation and leaving markets submerged in a supposedly autonomous logic of value and capitalist accumulation. On the other hand, “decentralization” was a process in which the state management institutions / services that arose and got consolidated due to the promotion of the nation, such as educational policies or health policies, are transferred – in their funding responsibility – to province and municipal jurisdictions, respectively.

In educational matters, during this time the Educational Transformation Plan is implemented, proposing a change of missions and functions of the National Ministry of Culture and Education, which represented the culmination of the transferring process of primary, secondary levels and tertiary non-university to provinces due to the adoption of Laws 24,049 (1992), LFE N° 24,195 (1994), and the Higher Education Law N° 24,521 (2015). ( GIOVINE; MARTIGNIONI, 2016 , p. 73).

According to bibliography, in the year 2001 governments started undergoing a “political metamorphosis” rather than an economic one. This “political metamorphosis” is understood as a change of the State. The State changed its form, disrupting its essence, but it was not fully transformed or revolutionized.

According to Adrián Piva,

[...] if the essential feature of the accumulation model that was developed in the nineties persisted, the State form has tended to show transformation tendencies and symptoms of an unsolved crisis. ( PIVA, 2015 , p. 77).

2001 is the year when the crisis got synthesized, it is the moment when an important rise of class struggle developed, as a resistance to financial adjustment policies. Although, “sadly for our people, by the time hegemony underwent a deep crisis, its plans had already been fulfilled in the essential aspects” ( HAGMAN, 2014 , p. 15).

In our country, specialists understand that policies implemented after the 2001 crisis show the beginning of a stage in which the political game, due to the way in which social movements and the street protests in general, seized the public scene ( GAGO; SZTULWARK, 2014 ).

Thus, between 2002 and 2005 a new government strategy was formed in Argentina, which, given its economic and political program, was named by different authors as “neo-developmentalist”. According to Claudio Katz (2016) , “given the variety of perspectives that neo-developmentalism congregates, it is not easy to specify its central theses”, but he understands that

[...] five tracks can be inferred, through which its proposals transit. First, the intensification of state intervention without obstructing private investment and private management strengthening. Second, the importance of economic policy as a central instrument to reduce dependence and generate growth. The third element returns to industrialization in order to multiply urban employment. Fourth, reduction of the technological gap. Finally, subsidize industrialists by allowing them to compete and teaching them how to do it. ( KATZ, 2016 , p. 140-141).

According to Katz, the principal neo-developmentalist experience was implemented in Argentina in the last decade, and “the country lead the economic shifts of the region one more time, as it did in the late fifties and sixties with the imports substitution, and again in the nineties by applying extreme neoliberal policies” (KATZ, 2016, p. 159).

The neoliberal capitalist restructuring process, as it was able to recompose the general conditions needed for capital reproduction, appeared as a condition for the reproduction of society as a whole. On this basis, government actions could present capital offensive as an expression of the public interest translated into political hegemony.

In this context, what the Argentine government understood was that “it was impossible to manage this system without a protagonist of the state bureaucracy and private sector managers. What is always at stake is the predominant type of state intervention in each period” ( KATZ, 2016 , p. 143).

Under those conditions, along with general “metamorphosis” a second educational reform takes place. This allows the continuity of processes that began during the nineties, i.e. a division of public and private sectors but, nevertheless, also reforms aspects such as the non-mercantilization of education, incorporation of infants and teenagers as universal subjects of law, extension of the age group for which attending secondary education is mandatory and, also, a reformation of the Argentine Education System. Still, this neo-developmentalism does not abandon the principle of favoring hegemonic groups, even though it entails “navigating in the sea of contradictions”.

The strategy adopted by the government is to promote a pragmatic adaptation to the conjuncture demands. Therefore, it incorporates multiple elements without defining a visible primacy of any. It is devoted to strengthen both the market and the State, to reinforce centralization and decentralization, to promote public and private sectors, enhance industrialization and also agro-exportation of manufactures, etc. ( KATZ, 2016 , p. 143).

Similarly, in education, public and private aspects coexist in the legal structure; government programs that centralize and decentralize institutional policies, alternative policies aimed to access permanency and graduation in compulsory education especially for the public sector, among others.

The neo-developmental consensus reconstructed the recurring illusion of class conciliation, of creating a project capable of benefiting grass-roots and the economic power, and also to guarantee the “greater good” over the interests of each sector, the State being merely a referee (HATMAN, 2012).

Still, given the contradictions, the continuity of the accumulation process depended more and more on the effectiveness of the coercive mechanisms (hyperinflationary threat, fragmentation of the labor force, high unemployment) to produce what Adrián Piva (2015) calls a “negative consensus “, which leads to a “weak hegemony” ( PIVA, 2015 , ´p. 24).

According to him, this process consisted of

[...] the stabilization of the internalization mechanisms of social contradictions through state absorption of struggle processes, (...) that allowed to translate potentially antagonistic and disruptive demands regarding the political regime into a reformist logic of awarding concessions. ( PIVA, 2015 , p. 96).

For Itaí Hagman (2014) , the existence of a strong consensus in relation to this new model inspired by neo-developmentalist ideas is evidenced in the continuity of almost all the government cabinet between one term and another, and also in the explicit support of the main business associations linked to the industry ( HAGMAN, 2014 , p. 23).

It could be stated that the beginning of this new post-2001 crisis development model was in the 2003 presidential elections which took place in April, but it is understood that during the first quarter of 2003 there was already 5.4% interannual GDP growth, which expresses that the recovery basis was probably already established prior to the beginning of a new government ( HAGMAN, 2014 , p. 24).

In May 2003, Néstor Kirchner assumed the presidency. In this assumption he makes statements that, according to the Hagman, are historically accurate because he shows complete awareness about the implications of neoliberalism and the 2001 crisis. He explicitly intends to rebuild a national capitalism that could generate work and social inclusion, propping up a national bourgeoisie and formulating policies with a greater degree of autonomy in relation to international hegemonic powers; according to the authors, the exit from convertibility was fully supported by local economic power.

This process of hegemonic reconfiguration shows a concern about the necessity of associating the State with popular movements, specially related with human rights organizations, reparation of the violence generated by State terrorism, the annulment of “due obedience” and “final stop” laws, resumption of trials to genocides, and adding the policy of Latin American integration.

According to Adrián Piva, the “form of government” implemented after 2003 makes it possible to translate potentially antagonistic and disruptive demands regarding the political regime into a reformist logic of granting concessions (PIVA, 2012, p. 96).

During the first period of the government, economic growth reached unthinkable levels. Between 2003 and 2007, the Gross Domestic Product grew 9% annually, recovering, in just one government term, four million jobs and recomposing the workers’ income. To achieve this, the State intervened, maintaining a high exchange rate, and strongly interceding in the economy. This was not seen by the concentrated capitals as a hazard, reason why consensus was maintained, and private management chose to continue articulating Peronism and integrating different sectors.

Thus, the “transversality” criterion was born, a successful experiment that brought together a large number of organizations and references that had been part of the questioning of the neoliberal model. The government modified the composition and selection methods of Supreme Court members. There were also changes in the relationship between State and theunions. On the other hand, are re-established commitees (dialogue between businessmen, government officials and workers), with the objective of recomposing the salary and legitimacy lost in 2001 ( PIVA, 2015 ).

Returning to the proposed challenge at the beginning of this article, data is presented below in order to show the performance of two variables in the post-2001 period, the behavior of the Secondary Education Coverage Rate, and the Youth Employment Rate along with their precarious work register. Finally, some approaches to the possible causal relationships between their nature.

Analysis of statistical data. Secondary education coverage and youth employment

Secondary education gross coverage rate 2001-2010

Initially, secondary education coverage was compared for intercensal period 2001/2010, from there a subtle drop in the national Gross Coverage Rate was identified, from 88.72% in 2001 to 87.27% in 2010, but in the Buenos Aires Province a severe drop was detected, decaying from 97.46% to 87.97%.

Table 1 Secondary education gross coverage for the intercensal period 2001-2010, in Argentina and Buenos Aires Province

| Gross Coverage Rate Secondary Education | 2001 | 2010 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nation | 88.72% | 87.27% | - 1.45% |

| Province | 97.46% | 87.97% | -9.49% |

Source: Prepared by the author, based on data from the 2001-2010 Census of Indec.

Distinguishing the Coverage Rate behavior according to the Basic or Higher Cycle categories, it is possible to corroborate that the previous fall is not registered for both cycles. Instead, it is only detected in the Oriented Cycle, falling from 74.48% in 2001 to 66.47% in 2010 nationally, and from 87.97% to 67.87% provincially. The Basic Cycle increases from 102.36% to 108.14% nationally, whereas the increment goes from 106.48% to 108.14% at the provincial level.

Table 2 Secondary education gross coverage rate, by cycle, for the period 2001-2010, in Argentina and Buenos Aires Province

| JURISDICTION | 2001 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic general education | Polymodal | Diference | Basic Cycle | Oriented cycle | Difference | |

| NATION | 102,36% | 74,48% | 27,88% | 108,14% | 66,47% | 41,67% |

| PROVINCE | 106,48% | 87,97% | 18,51% | 108,14% | 67,87% | 40,27% |

Source: Prepared by the author, based on data from the 2001-2010 Census of Indec, and Statistical Yearbooks of DINIECE.

The foregoing statement allows us to infer, on one hand, the existence of a “selection” process from one cycle to another, and on the other hand, it also allows us to infer the coexistence of this so called “selectivity” with other mechanisms, such as “retention”, since there is an increase in the Basic Cycle coverage that even exceeds the 100% of its possibilities for the same periods.

In the light of the previous findings, it could be thought that there is a secondary level confronting a clearly structural problem, the coexistence of structures with “retention” and consequent “selectivity” phenomena.

When considering the Coverage Rate according to public and private sectors, it can be observed that in one sector it decreases and in the other in increases. The first one is the public sector, the second one is the private sector. As shown in Table 3 , the public sector falls in the intercensal period, 0.77% nationally and 2.26% provincially. The private sector increases 0.76% in the whole nation, and 1.26% in the Buenos Aires province.

Table 3 Secondary education coverage rate, by sector, for the period 2001-2010

| Year | Secondary Education Coverage Rate, Public Sector | Secondary Education Coverage Rate, Private Sector |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 70,51 | 29,48 |

| 2010 | 68,25 | 31,74 |

Source: Prepared by the author, based on data from the 2001-2010 Census of Indec

In this regard, the arising hypothesis is that in a period of political and economic recompositing certain “segregation” ( VAZQUEZ, 2012 ) mechanisms seem to strengthen. “Selection” is then added to “segregation” and “retention”, which is another separation mechanism of the student population in establishments that in this case are differentiated by their management form.

In summary, this allows us to infer, on the one hand, the existence of a “selection” process of when moving from one cycle to another, with – as observed in the percentages – a significant loss of coverage, which is recorded for both jurisdictions and for both periods, and would allow inferring that this behavior is a structural tendency of the Argentina Education System and the Buenos Aires Education Province that is maintained during the 2001 crisis and subsequent to it.

However, compared to the previous findings, it could be thought that there is an education system, and specifically at secondary level, confronting structural problems, the coexistence of structures with tendencies to binding nature, with “retention” and consequent “selectivity” phenomena, that even intensify in a context of political and economic recovery.

A third feature that emanates from analyzing secondary education structures during the intercensal period is the continuity of a process already studied by Cecilia Braslavsky during the eighties; the “disarticulation” of this educational level, a phenomenon that generates vertical differences within the system, allowing each level – in this case each cycle – to function as a “closed shop”, isolated form the remaining levels. So what happens in the Basic Cycle cannot be defined accordingly to undergoing the Oriented Cycle.

Youth employment rate, 2003/2010 period

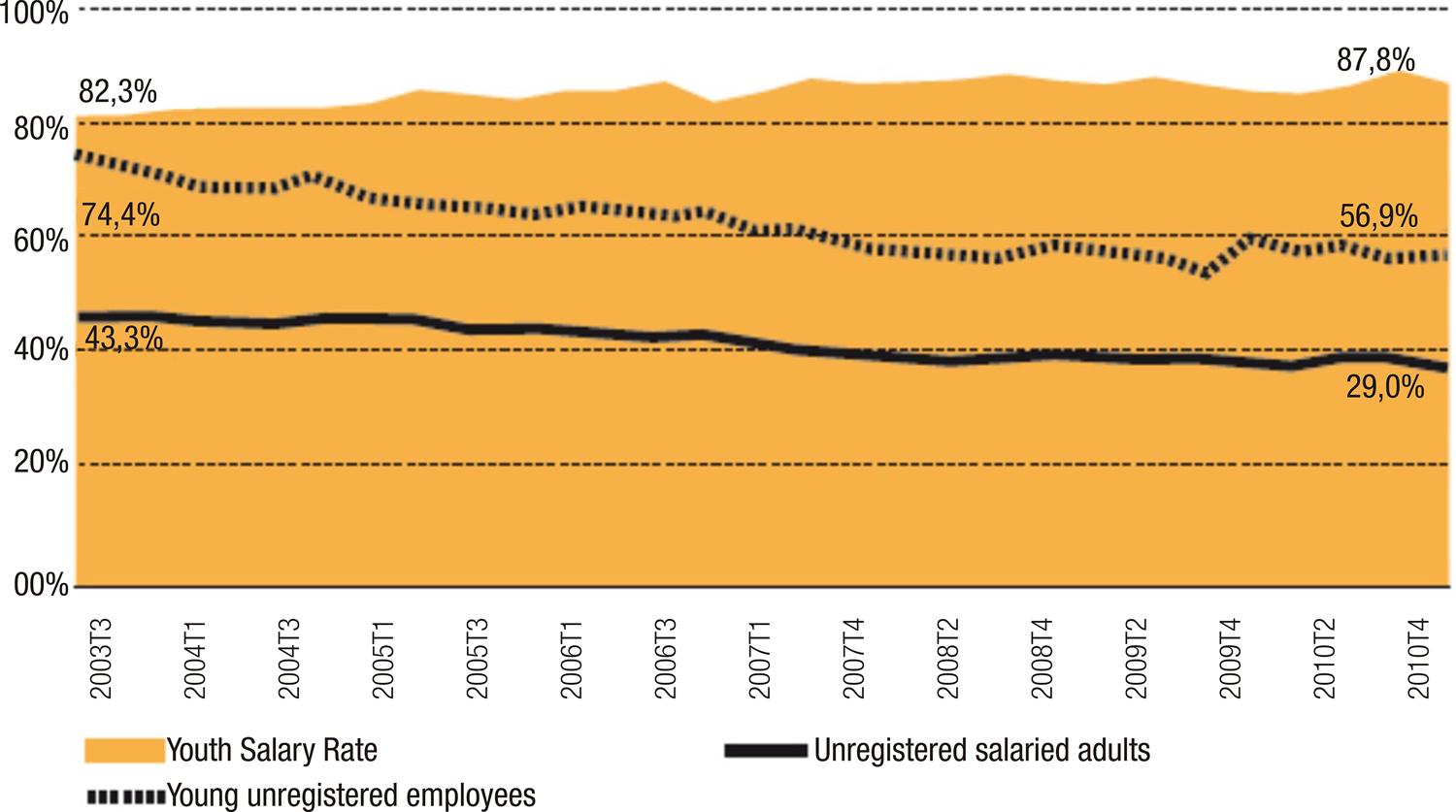

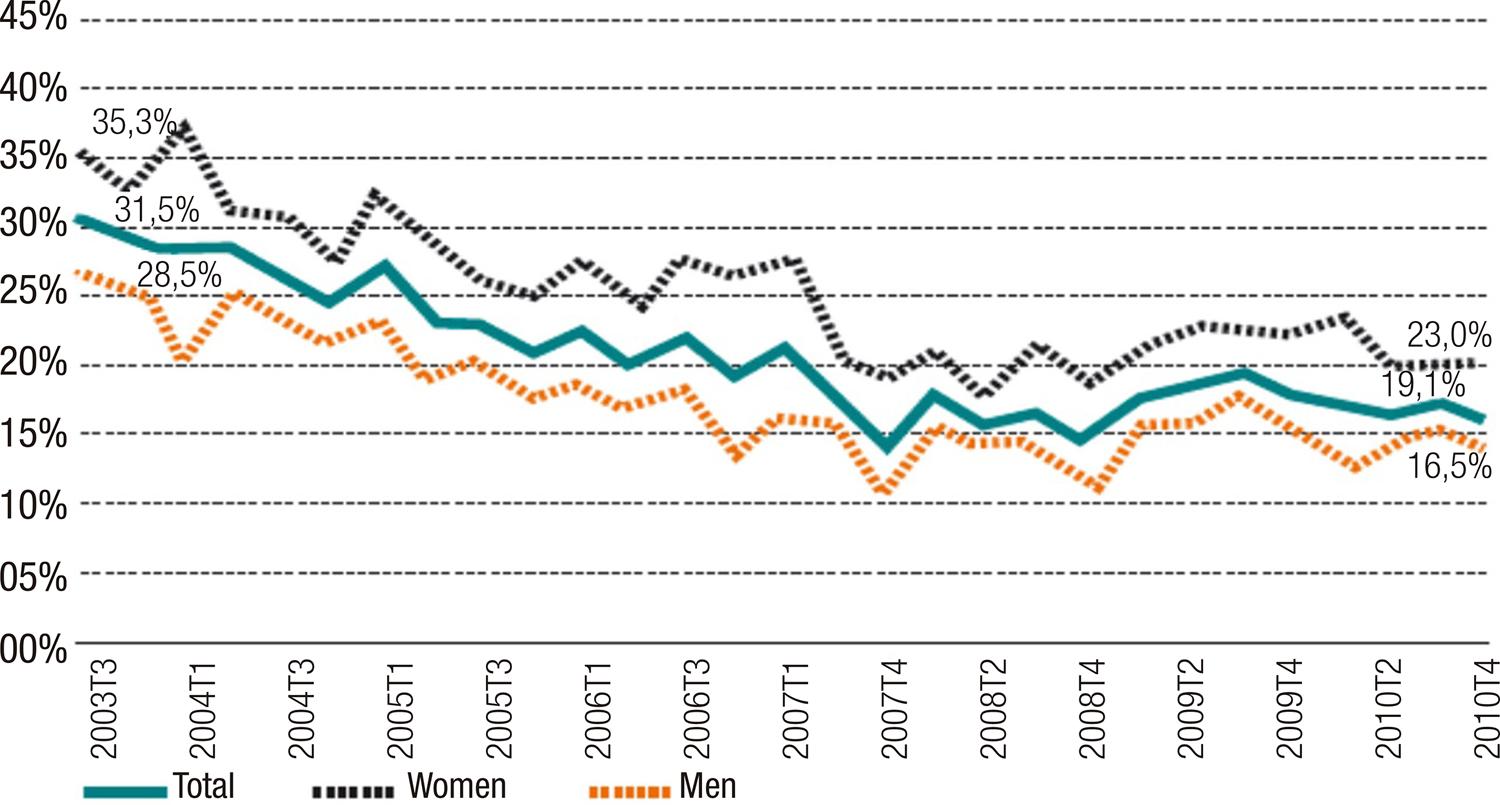

According to a report by the Organización Internacional de Trabajo (hereafter OIT), from 2003 to 2010 youth employment increases, or, likewise, unemployment rate for young people between 16 and 24 years of age decreases. In percentage, it falls from 31.5% in 2003 to 19.1% in 20102 .

Source: Prepared by the author, based on data from EPHC, 2010.

Graph 1 Youth employment increases, total and by genre, 2003-2010Note: people by 16 - 24 years old.

When relating these data with those referring to the Secondary Education Coverage Rate, the hidden rationality seems to suggest that less education system coverage grants greater access of young people to the labor market.

When characterizing the quality of youth work, it can be observed that it becomes an increasingly precarious labor market.

Although the share of young people between the ages of 16 and 24 that participates in the precarious labor market has declined since 2003, 56.9% of salaried young people (both men and women) had an unregistered job during the last quarter of 2010, while the non-registration rate for the adult population reached 29%. Bearing in mind that, considering the economically active population, the percentage rate of young population that earns a salary exceeds 85%, it can be observed in Figure 2 that non-registration greatly affects the employed young people.

Conclusions: Possible causal links which explain the relationships between youth, education and work in the neo-developmentalist Argentina

Until here, a series of conclusions are established that, interpreted from the theoretical frameworks proposed by the Sociology of Education, especially in their critical approaches, allows us approximations to answers about what is the hegemony relation between the educational system, the strategies of State governability, and the labor market for young people.

The first concern that evidently arises when analyzing these data is: Is there a relationship between the fall of the secondary education coverage rate and the increase of young employment rate?

However, considering the political context in which this phenomenon is manifested, it is striking that under circumstances of recovery of social consensus from the right perspectives, the number of young people who “leave” their schooling to enter the labor market grows. So why, in a context of political and economic recovery, is the young population retained in the first cycle of their secondary education, selected in the second cycle, and segregated according to the sector where young people, whether public or private, transit?

The relationship between systematic education offered by the State and access to the labor market in young people varies according to the conjunctural configuration of the labor market. In this case, it is observed that, in a period of economic and political recovery, of institutional recovery which is also expressed in educational policy that, for example, extends the compulsory nature of secondary education, young employment increases.

It seems as if the social system, in a neo-developmentalist context, does not only need young people schooled and ranked within the education system, but also young population not attending to school in order to get incorporated to the labor market. In some way, here we can see the permanence of a structural characteristic of the national State, the distribution of the young population in differentiated circuits. In this case what we see is the existence of two circuits, the education system to educate (in both public and private modalities), and the labor market.

The educational system continues to be a regulator, hierarchizing and classifying the population, being functional to the requirements of a labor market that needs, as it seems, of precarious young people. This function is a function of hegemony. It is the hegemony function that the educational system fulfills in this period. Its task is to dam up the population in the first years of secondary education and to classify the students of the level’s second cycle.

Every function of hegemony uses, according to the circumstances, coercion or consensus. Such behavior involves a strong coercive process, as observed by the selection mechanism, which does not integrate differences, but expels what is presented as an insurmountable antagonism.

After analyzing the state situation, and specifically what refers to the educational policy, it becomes evident that, thanks to its regulations, these processes become invisible.

When regulation (National Education Law) is considered and compared with the exposed data, it is evident that it was not constructed based on an accurate diagnosis of what happens in the system structure.

Given the fact that the diagnosis made explicit in regulations is not established based on statistical data, it could be considered, from the theoretical framework proposed, that a process of symbolic violence has taken place, which occults the struggle that leads to a characterization of the educational system. Moreover, it can be thought that, what appears as structural in population “selection”, that is explained from an individual conception, which depends on the trajectories of the subjects, while this present study allows us to verify that it is due to a social process.

That is, the norm differentiates the subject from the social totality, considering these processes individually, which implies relating the subject with its particularity, and not with its social origin, with his links with the social totality.

This process, which the authors propose as the exercise of a “fetishism” power of, deepens and complicates the “myth of equality”. Equality is clearly a phenomenon to which we aspire, but which is unattainable, at least as long as the educational system structure ends up “selecting” population that is then absorbed by the labor market. In short, within the sea of contradictions that characterizes the Argentine state during this stage, it also expresses a contradictory process in youth, equality / inequality.

Now, how is this contradiction expressed? In structural terms, a part of its source should be sought in the phenomena occurred since the 1990s in Argentina, such as privatization, deregulation, and privatization of the State. In this post-2001 context, we observe a secondary education divided into networks, a network where the level is completed and another one that is cut in its first half, a phenomenon to which, if we incorporate the public / private variable, we add two sub networks, the differentiated trajectories according to public sector and / or private sector. It is necessary to consider that in non-structural but conjunctural terms, an increase of population that completes the secondary education level is observed. Although this does not “revolutionize” the system, at least it quantitatively cushions the “selection”.

Thus, in a “neo-developmentalist” period, the strategy of hegemony, the pragmatic adaptation to the demands of the conjuncture, the coexistence of contradictions such as the coexistence between public and private realms, between centralization and decentralization, between conservative and progressive, the educational system is placed in a situation where the “containment” and “selection” is a functional strategy to establish a young social order which characteristic is the economy recovery of the economy, but within the framework of an increase in youth demand by the labor market.

REFERENCES

BOUDELOT, Christian; ESTABLET, Roger. La escuela capitalista en Francia. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 1971. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. El nuevo capital, introducción a una lectura japonesa de la nobleza de estado. In: BOURDIEU, Pierre. Escuela y espacio social. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2008. p. 3-8. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU Pierre; PASSERON Jean Claude. La reproducción: elementos para una teoría del sistema de enseñanza. Barcelona: Laila, 1972. [ Links ]

BRACCHI, Claudia; GABBAI, María Inés. Estudiantes secundarios: un análisis de las trayectorias sociales y escolares en relación con las dimensiones de las violencias. In: KAPLAN, Carina V. (Dir.) Violencia escolar bajo sospecha. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2009. p. 55-80. [ Links ]

BRACCHI, Claudia; GABBAY, María Inés. Subjetividades juveniles y trayectorias educativas: tensiones y desafíos para la escuela secundaria en clave de derecho. In: KAPLAN, Carina V. (Dir.). Culturas estudiantiles: sociología de los vínculos en la escuela. Buenos Aires. Miño y Dávila, 2013. p. 23-44. [ Links ]

BRASLAVSKY, Cecilia. La discriminación educativa en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Flacso, 1985. [ Links ]

CORBIERE Emilio. Hegemonía. In: DI TELLA, Torcuato (Dir.). Diccionario de ciencias sociales y políticas. Buenos Aires, Emecé, 2001. p. 326-327. [ Links ]

DOMBOIS, Rainer. Trayectorias laborales en la perspectiva comparativa de obreros de la industria colombiana y la industria alemana: cuadernos de desigualdad educativa en contextos de obligatoriedad de la educación secundaria. In: ZAMUDIO CÁRDENAS, Lucero; LULLE, Thierry; VARGAS, Pilar (Coord.). Los usos de la historia de vida en las ciencias sociales. v. 1. Madrid: Anthropos, 1998. p. 171-212. [ Links ]

GAGO, Maria Veronica; SZTULWARK, Diego. La vanguardia latinoamericana: cinco hipótesis para discutir con Laclau. In: GAGO, Maria Veronica; SZTULWARK, Diego. Hegemonía y populismo en el cono sur: debates en torno a la teoría de Ernesto Laclau. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Arcis: Akhilleus, 2014. p. 49-58. [ Links ]

GIOVINE, Renata; MARTIGNIONI, Lililana. Políticas educativas e instituciones escolares en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Unicen: Tandil, 2016. [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, Antonio. Notas sobre Maquiavelo, sobre la política y sobre el estado moderno. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión. 1981. [ Links ]

HAGMAN, Itai. La Argentina kirchnerista en tres etapas: una mirada crítica desde la izquierda popular. Buenos Aires: Patria Grande, 2014. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, Viviana Carina. La inteligencia escolarizada: representaciones sociales de los maestros sobre la inteligencia de los alumnos y su eficacia simbólica. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 1997. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, Viviana Carina; LLOMOVATE, Silvia. Desigualdad educativa: la naturaleza como pretexto. Buenos Aires: Noveduc, 2005. [ Links ]

KATZ, Claudio. Neoliberalismo, neodesarrollismo y socialismo: batalla de ideas. Buenos Aires: Alba, 2016. [ Links ]

LACLAU, Ernesto. Hegemonía y estrategia socialista. México, DC: Siglo XXI, 1987. [ Links ]

MARX, Karl. La cuestión judía. Barcelona: Planeta Agostini, 1992. [ Links ]

OIT. Oficina Internacional del Trabajo. Trabajo decente para los jóvenes el desafío de las políticas de mercado de trabajo en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: OIT, 2011. Disponible en: <http://www.ctabsas.org.ar/IMG/pdf/trabajo_decente_para_los_jovenes_el_desafio_de_las_politicas_de_mercado_de_trabajo_en_argentina_.pdf>. Acceso en: 5 oct. 2018. [ Links ]

PIVA, Andrés. Economía y política en la Argentina kirchnerista. Buenos Aires: Batalla de Ideas, 2015. [ Links ]

PORTANTIERO, Juan Carlos. Clases dominantes y crisis política en la argentina actual. [S. l.: s. n.], 1972. [ Links ]

PUIGGRÓS, Adriana. Imperialismo y educación en América Latina. Veracruz Llave: Nueva Imagen, 1980. [ Links ]

PUIGGRÓS, Adriana. Sujetos, disciplina y currículo: en los orígenes del sistema educativo argentino. tomo I. Buenos Aires: Galerna, 1990. [ Links ]

VAZQUEZ Emanuel. Segregación escolar por nivel socioeconómico: midiendo el fenómeno y explorando sus determinantes. Documento de Trabajo, n. 128, ene. 2012. Provided in cooperation with: Centro de Estudios Distributivos, Laborales y Sociales (CEDLAS), Universidad Nacional de La Plata. [ Links ]

Received: October 13, 2018; Revised: March 20, 2019; Accepted: May 21, 2019

texto em

texto em