Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 06-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046212749

SECTION: ARTICLES

Strategies, resources and interactions in class: contributions for postgraduate training in administration and related fields

1 - Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia . Contacto: ci.carreno49@uniandes.edu.co.

2 - Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia . Contactos: cielo.mancera@urosario.edu.co; armando.duran@urosario.edu.co; clara.garcia@urosario.edu.co.

The article presents a reflection on pedagogical strategies, resources for teaching and interactions in class from the perspective of training, with the aim of encouraging and exalting transformative pedagogical practices, inspired by reflective dialogue, collaborative work and meaningful learning in postgraduate studies and, particularly, in the case of administration and related subjects. Theoretically, it starts from two main notions. The first refers to training, understood as a permanent and dynamic process of creation, and whose main purpose is to continuously and consciously shape the potential of the person in complex and changing environments. The second refers to the pedagogical practice, understood as the deliberate and reflexive experience of teachers and students around the training act, that is, it gives an account of the ways in which educational actors produce, experience, reflect and appropriate particular pedagogical strategies, resources and class interactions. The methodological approach used is qualitative, and it privileges consultation techniques and documentary analysis, fundamentally. With these devices we seek to guide present and future educational efforts for postgraduate programs in administration and related fields. As main findings, pedagogical and didactic openings for training work are identified; patterns of reflection on teaching activity and observations accompanied by a feedback exercise that invites managers to think about administration and related teachings with a cognitive, social and ethical significance, as well as incorporating and strengthening teacher training as a generating environment for innovative pedagogical practices.

Key words: Training; Pedagogical practices; Postgraduate education; Administration and related fields

El artículo presenta una reflexión sobre las estrategias pedagógicas, recursos para la enseñanza e interacciones en clase desde la perspectiva de la formación, con la inquietud de animar y enaltecer prácticas pedagógicas transformadoras, inspiradas en el diálogo reflexivo, el trabajo colaborativo y el aprendizaje significativo en posgrados y, particularmente, para el caso de la administración y afines. Teóricamente se parte de dos nociones principales. La primera refiere a la formación, comprendida como un proceso permanente y dinámico de creación, y que tiene como propósito fundamental el dar forma de manera continua y consciente a la potencialidad de la persona en entornos complejos y cambiantes. La segunda alude a la práctica pedagógica, entendida como la experiencia deliberada y reflexiva de profesores y estudiantes alrededor del acto formativo, esto es, da cuenta de los modos en que los actores educativos producen, experimentan, reflexionan y apropian particulares estrategias pedagógicas, recursos e interacciones en clase. El abordaje metodológico utilizado es cualitativo y privilegia las técnicas de consulta y análisis documental, fundamentalmente. Con estos dispositivos se busca orientar presentes y futuras apuestas pedagógicas para programas posgraduales en administración y campos afines. Como principales hallazgos se identifican aperturas pedagógicas y didácticas para el trabajo formativo; pautas de reflexión sobre la actividad docente y observaciones acompañadas de un ejercicio de retroalimentación que invita a los directivos a pensar la enseñanza de la administración y afines con una trascendencia cognitiva, social y ética, además de incorporar y fortalecer la formación docente como ámbito generador de prácticas pedagógicas innovadoras.

Palabras-clave: Formación; Prácticas pedagógicas; Enseñanza posgradual; Administración y afines

Introduction

This article emphasizes the contributions that pedagogy and didactics make to the training processes at the graduate level, in particular, when teachers as artists (EUSSE; BRACHT; ALMEIDA, 2016) or artisans (ALLIAUD, 2017) create, innovate, program and execute new strategies, resources and interaction in class. It is based on considering that by being an expert and a researcher on a subject or a content, one does not necessarily have the power to know how to teach it and that having mastery over a content does not necessarily make it possible to distinguish, in a formative perspective, what it is necessary to learn and how it should be taught (GRISALES-FRANCO; GONZÁLEZ-AGUDELO, 2009). In this context, this article calls to attention educational administrators and other educational community about the importance of promoting and appropriating a reflective and permanent attitude towards the training act. Specifically, the following question is answered: What kind of strategies, resources and class interactions strengthen the transformative pedagogical, exchange, collaboration and relevance practices in postgraduate courses, particularly in administration and related fields?

Conceptual starting references

This article considers the institutionalized, contextualized and educational purposes as necessary to activate and strengthen permanent processes of transformation and sustainable human development. Recognizes the importance of organizing reflective and critical pedagogical and didactic pedagogical processes of cognitive, emotional and social change, in which the various actors of the educational community, especially the students and teachers, participate actively. The educators have a leading role in the training exercise, first of all, they are a source of example, they are guarantors of the motivation and the pleasure to learn how to learn, that is, and in terms of Mistral (1948 apud PFEIFFER, 2017), they are the triggers of the spark towards deliberate, self-regulated and meaningful learning. Likewise, it is deemed essential that pedagogical practices, in their programming, implementation and completion, be reflexively assumed based on authentic, democratic and cooperative experiences. This is the perspective that guides this section on training and pedagogical practices.

Training

In ancient times the training focused on sharing with young people the values and techniques of the civilizations in which they lived; in introducing children and young people to the world of privileged classes; in instructing them in the know-how; and in forming them in character (MARROU, 1985). Over time, training privileges rural activities, seeks to promote government skills and generate skills for political performance and, above all, seeks to train the new citizen (LUNDGREN, 1991). In general terms, training was characterized as a space that brought individuals closer to historically accumulated knowledge.

Following Maturana and Nisis (1997), the notion of human formation requires revision and understanding beyond the transition to adult life or, in terms of Dewey (1920), of being the preparation for a remote future. It needs to be understood in a manner consistent with everyday life and to reassess two central elements: know-how and inner training. From this perspective, training has to do with the development of people in terms of having the capacities to “[…] be co-creators with others of a human space of desirable social coexistence” (MATURANA; NISIS, 1997, p. 15).

In some educational institutions it is common to find that the training process is exclusively aimed at the student acquiring the body of knowledge essential for professional performance. This situation, in perspective with the aforementioned, is problematic, since it does not address training as a process that goes beyond a transmission of existing knowledge and a transit to, which in the case of higher education intends to form a professional in a particular discipline or field. In this sense it is necessary to rethink the notion, for example, overcoming pedagogical orientations anchored in the “transfer of neutral knowledge” (FREIRE, 1993, p. 74). What in other words would mean, to conceive training as an act in which “[…] ethics practitioners and citizens [that focus] on social cohesion and not just competitiveness” are produced, reproduced and appropriated (VILCHES; FERNÁNDEZ; MARTÍNEZ, 2016, p. 85). Knowledge that builds life ethics, that respects and enhances students’ prior knowledge, that guides their own view but contextualized in relation to that of others.

In particular, this training includes the training offered by teachers as a transformative process that focuses on the realization of the contextualized being , where dialogue, knowledge and meaningful experiences are the primary drivers of this agency. In short, training will be understood as a continuous process where the subject seeks to display his potential, seeks to be autonomous and responsible in relation to others, that is, seeks the deployment of cognitive skills, the mastery of emotions and the cultivation of skills, that contribute to the development and personal, social and environmental realization from a fair and sustainable perspective.

Pedagogical practices

In the institutionalized educational context this constant improvement of being has been configured primarily through pedagogical-didactic processes that are specified in teaching, understood in a double movement (CARREÑO, 2012). First, as a deliberative, critical and heuristic intervention that contains and promotes integral development, which in other terms would mean a commitment to strengthen the political dimension of training. And, second, as a dynamic process that is fundamentally based on relational learning, that is, of oneself, of others and of the environment. These processes are possible thanks to the pedagogical practices that, first and foremost, constitute learning devices where teachers and students experience and appropriately and differentially adopt strategies, resources and class interactions.

Pedagogical practices allow the teacher to create training environments that favor the understanding of differential ways of learning: How do you learn?; How do you face the challenges that emerge from the training process and the context in which you are immersed? Reflections involved in the previous questions, no doubt, contribute to the teacher becoming a real companion to the process of personal and professional achievement of the student. For example, by creating interdependence and monitoring between the contents of the class and the stories, memories and personal and social expectations that underlie the group; in planning and evaluating the modalities of interaction and dialogue that characterize the classroom environment; by designing teaching strategies that allow the search for overcoming and improvement of the knowledge achieved.

According to Eusse, Bracht and Almeida (2016), the pedagogical practice is much more than a rational, technical and instrumental process, given that it constitutes a work in which the teacher is an “[…] artist who seeks that the other [the student] is transformed ”(p. 14), that acquires the skills to self-regulate and thus can properly conduct his own formative process. One way of synthesizing some of the most significant topics of pedagogical practices has to do with assuming the classes at three main moments: programming, passing and culminating (LITWIN, 2008; JACKSON, 2002). Over time the conception and deployment of pedagogical practices are a matter of debate and reflection, in particular for this article it is considered central:

That as a human practice, it requires not losing its ethical purpose, facilitating and promoting exchanges in the classroom that make it possible to experience values that are considered essential for communities (ELLIOT, 1990).

That although it invites the student to approach historically produced knowledge, it also demands that it be enriched and transformed with a critical, contextual and scientific spirit (PÉREZ; GIMENO SACRISTÁN, 1992).

That is not limited to “[…] immersing students in a worldview, thus limiting the critical awareness of their [own history] and its historical, cultural, political or ideological dimensions” (MACLEOD; GOLBY, 2003, p. 355, faucets authors).

That the educational organization, assumed as a learning community, needs to be oriented towards the understanding and transformation of the being and the society , within the framework of a commitment decided to assess the coexistence between human beings and other species with which they live (VILCHES; FERNÁNDEZ; MARTÍNEZ, 2016, authors griffin).

Aspects such as those mentioned above urge to investigate prioritized pedagogical practices in different contexts, disciplines or fields of training, as well as to maintain the invitation to teachers and teacher trainers to deliberate on what it means, among other aspects: the learning ; the essence and educational value (KLAFKI, sf ); and the results of his intervention (FREIRE, 1993; ELLIOT, 1990).

Methodological aspects

The research underpinning this article favored a qualitative methodology (CRESWELL; POTH, 2018; GUBER, 2001) that describes, analyzes and interprets in a situated way to contribute to the transformations necessary for the construction of more inclusive and deliberative societies. In particular, documentary analysis is prioritized (COOPER, 2010 apud CRESWELL, 2014; BARDIN, 1986), understood as the process of discovery and systematic study that the researcher deliberately performs around a documentary corpus. The execution was conducted based on the tracking of new knowledge documents (primary) that were identified in specialized databases between July and August 2015 3 and between November 2017 and January 2018, having as central descriptors: strategies, resources and classroom environment in perspective of postgraduate education, in particular, reflections on administration and related fields were privileged. Then, we proceeded to examine and systematize the information based on specialized summaries (secondary documents), for this the proposal of Bardin (1986) was used, privileging the orientation of the manifest content. This documentary corpus was coded from categories and subcategories seeking encounters and divergences between authors and research results (STRAUSS; CORBIN, 2002). The textual fragments of the primary and secondary documents, in the work of bricoleur (DENZIN; LINCOLN, 2005) were combined and put into dialogue seeking to answer the central question that guides this article. Finally, and retaking the doctoral thesis and productions of new knowledge of one of the authors of this paper, some bridges were created between the various contributions of the experts against teaching in general and the administration and its related fields in particular.

In summary, the methodological approach of the study was eminently inductive and qualitative. Inductive for the interest in individual meanings and for generating meanings from the findings and the representation of the complexity of the situations analyzed (CRESWELL, 2014). And qualitative because of its accent in the understanding of “[…] the social phenomena from the perspective of those who live immersed in them” (TRIGOS-CARRILLO, 2013, p. 4). Specifically, the search for answers to the research question is achieved by examining production of new knowledge related to administration and related teaching (TSEKLEVES; COSMAS; AGGOUN, 2016; QUIROGA; SHUSTER, 2013; BAILEY; FORD, 1996; MONTENEGRO-VELANDIA et al., 2016; GORBANEV, 2012; TEJADA et al., 2012; LÓPEZ; PÉREZ, 2012; MORENO; SIERRA, 2011; ALONSO et al., 2012; CAÑEDO et al., 2008; HIDALGO, 2007; AKTOUF, 2005; WASWERMAN, 1994). This panorama enriches the view that is offered from the pedagogical, didactic and other disciplines or fields (WILLS, 2017; CARREÑO; DURÁN, 2017; MORALES; CARREÑO, 2017; VILCHES; FERNÁNDEZ; MARTÍNEZ, 2016; GONZÁLEZ, 2016; FLACSO ARGENTINA, 2015; BROOKS; HERSHOCK, 2015; WORTHEN, 2015; CARREÑO; DURÁN, 2015; MOREIRA, 2013; POOT-DELGADO, 2013; REPKO, 2012; ALLIAUD, 2017; DOMÍNGUEZ, 2011; VENTURA, 2011; MORENO; SIERRA, 2011; MALDONADO, 2007; ELDER; PAUL, 2002; DÍAZ, 1999; FREIRE, 1993, 1997, 1999; SHÖN, 1987).

Pedagogical strategies, teaching resources and classroom interactions

Who teaches and forms, requires deliberately transit through a “[…] dynamic, dialectical movement between doing and thinking about doing” (FREIRE, 1997, p. 40). This reflective process on educational praxis encourages lifelong learning, involving not only the experiences of the actors directly involved in the educational act but also the educational community and the institutional culture that serves it as sustenance and context. From this horizon of meaning, some contributions on strategies, resources and interactions in class are presented below, with the concern of encouraging and exalting transformative pedagogical practices, inspired by reflective dialogue, collaborative work and meaningful learning in postgraduate courses and , particularly, in the case of administration and related matters.

Pedagogical strategies

Pedagogical strategies transcend the rational and technical mastery of knowledge by including fundamental purposes of the educational act, namely: autonomy (FREIRE, 1999); deliberation (GIROUX, 1997); and transformation (EUSSE; BRACHT; ALMEIDA, 2016). They are understood as reflections and formative actions with a deliberate and critical sense that are guided by artisan professors (ALLIAUD, 2017) that structure creative spaces and forgers of multiple agencies where students approach knowledge to challenge and co-produce it. In terms of what has been proposed or could be suggested for the administration and related teaching, three modalities of formative work are identified: programming and management of participatory activities; interdisciplinary learning; and collaborative learning.

Programming and management of participatory activities

From the point of view of what a teacher requires so that students approach in a significan manner the real context of their training, Quiroga and Schuster (2013) propose linking professional workshops in teacher programming. In particular according to four dimensions of learning: learning to know; learn to do; learn to be; and learn to live together. They identify that incorporating professional workshops in the classroom, inspired by action research methodologies, generates significant changes and excellent results for the teacher and the students.

The authors Quiroga and Schuster believe that this process has to be encouraged by research, checking and constant change to make innovation effective. The professional workshop strengthens the creative, collaborative and reflective work of both teachers and students. The former requires, among other aspects, organization and design of questions that provoke critical and proactive thoughts in dialogic, dynamic and horizontal educational environments. The latter are challenged to examine texts and contexts with relevance and insight. In addition, it invites them to sponsor analysis with critical argumentation, in spaces marked by collaboration, the designation of challenges and the understanding in terms of solving specific problems. Perhaps, here it is important to highlight that this type of collaborative work and social coexistence deployed in professional workshops, reinforces the personal confidence and identity of educational actors, to the point that the participants cooperate and work together without having to “[…] fear of disappearing in the relationship” (MATURANA; NISIS, 1997, p. 15).

On the other hand, Freire (1993) asserts that the reflective dialogue between teachers and students marks a democratic position in the classroom, unlike the usual classes in which knowledge is transferred from the first to the second. He considers as deeply valid the small presentation that the teacher makes on a subject and that, followed by questions, generates participation among the students. The democratic orientation in the formative process leads to forging the character of political subject of the educational actors and, in particular, to make the classroom experience an exercise in deepening participatory democracy, that is, of democracy anchored in everyday training life.

For his part Worthen (2015) adds that a good cycle of conferences combined with small sections of weekly discussion produces in students, especially in the fields of the humanities, basic skills that are related to “[…] understanding and reasoning, skills whose value extends beyond the classroom […] a good master class […] teaches a rare skill in our ´Smartphone´ culture: the art of attention, the first crucial step in ´critical thinking” (s. p).

And critical thinking (GIROUX, 1997; PÉREZ; GIMENO SACRISTÁN, 1992) breaks into the traditional discourses of teaching, which confer to the pedagogical practices the status of instruments of control and reinforcement of the heteronomy of the subjects, by enabling recognition of the relationships between knowledge, power and domination, that is, by understanding educational strategies as virtual carriers of change, possibility and the power of the human.

Likewise, Tejada and other authors (2012) consider that collaborative works in the form of debate and individual practices allow us to reflect on everyday issues, carry out an autonomous learning process and use conceptual and methodological tools according to the objectives set. From the pedagogical practice, they recommend didactics that encourage students to search for new bibliographies, case studies, resources and learning activities that stimulate the exchange and argumentation of their own thesis. In this context, it is important to emphasize that one of the main topics of autonomous learning is related to the generation of self-thinking, which results from an interdependent process of triadic formation, namely: formation of historical sensitivity (FREIRE, 1993); formation of critical sensitivity (GIROUX, 1997); and formation of ethical sensitivity (ELLIOT, 1990).

Interdisciplinary learning

In practice, interdisciplinary learning encourages markedly active, reflective, collaborative and deliberative pedagogical processes, since it promotes: the comprehensive understanding of complex problems of reality from the debate; the negotiation and argumentation of plural ideas; the search for answers to questions that overflow the study objects of the disciplines; and the generation of alternatives from transdisciplinary thematic fields (MORALES; CARREÑO, 2017).

Interdisciplinarity is a perspective of tax knowledge of the cooperation between diverse theories, concepts and methods, which comes from the experience of multiple disciplines centered on the understanding and collaborative intervention around a specific phenomenon. This experience becomes significant (MOREIRA, 2013) when it allows that in the dialogue between student-colleagues, which would be the case of postgraduates, the contents and debates are substantially and intentionally related, similarities and differences are established and the organization is reorganized. knowledge to create your own.

Interdisciplinary teaching creates bets and training strategies common to various fields of knowledge or disciplines. For this, it redefines, extends and transforms (REPKO, 2012) the pedagogical practices from the experiences and learnings located in relational and interdependent contexts and fields. The deliberate approach to the formative processes from the specificities of the objects of knowledge, which have been co-produced with the participation of different disciplines, implies making evident the need to think of the formative acts as a synergistic encounter where the fields of knowledge involved they constitute the foundations and the power of a particular commitment to interdisciplinary teaching. For example, the origin and implementation of postgraduate studies on Development studies, from the experience of Wills (2017), has shown that it is possible to create spaces inspired by the formative debate and horizontal dialogue between disciplines; in the joint work between the different actors that, although formed in different disciplinary fields of knowledge, converge in the educational act; and in learning the different ways of knowing, appropriating and experiencing social reality, that is, in “[...] fostering the understanding of other cultures, ways of life, values and beliefs” (p. 39).

Pedagogical practices oriented from interdisciplinary teaching can be assumed as formative processes tending to energize integrating fields of knowledge or integrating areas of learning, which urge knowledge, doing and knowing-doing in contexts characterized by otherness. Hence, topics such as: active listening, de-learning, humility, creativity and curiosity (FREIRE, 1997) become structuring sources of interdisciplinary training processes.

Collaborative learning

Collaborative learning is based on the social character of learning (MALDONADO, 2007). Learning is seen as a process of interaction, responsibility and reciprocity between the actors that come together in the training. One of the primary postulates of this type of learning is that it is best learned when there is shared work, exchange, creation of meanings and collective argumentation in dissenting scenarios.

Unlike competitive learning, this type of learning intends for the training be generated between and for all, it is for this reason that it privileges work between colleagues-peers, tutorials in groups and plenaries. Montenegro-Velandia and other authors (2016) recommend visits and business practices as spaces to learn in collaboration because it is from “[…] contact with the problems of companies and their working methods” (p. 210) how Students can relate and understand the conceptualizations addressed from the reference readings and classrooms.

To encourage interdisciplinary and collaborative learning, two methods are mainly highlighted in the literature review carried out: case studies and Problem Based Learning - (PBL). Each bet makes sense when the teacher prepares himself in a scientific, physical, emotional and emotional way (FREIRE, 1997), evaluates and monitors all his pedagogical practice and imprints “[…] passion and hope around the contribution to the generation of a better world” (GIROUX, 1997, p. 49).

Case studies have been a widely used method of teaching administration. For Waswerman (1994) it is valuable to use it because it allows to: stimulate thinking; increase learning; strengthen communication; improve the ability to analyze complex problems; and make wise decisions. He adds that with this strategy “[…] students become more curious; their general interest in learning increases. It also increases their respect for opinions, attitudes and different occurrences of other students. They are more motivated to read materials not presented in class” (p. 10).

Aktouf (2005) disagrees with the previous position, for him the use of case studies in administration education reproduces an ideology centered on capital, individual enrichment, mathematization, impersonal and rapid actions. It is suggested from this article and considering these positions, that case study be linked to the perspective of illustration, exemplification, assessment and scrutiny of the different points of view of the actors that converge in the analyzed situation. In addition, the case study could lead to moments of critical reflection towards the purposes of the action, that is, cross-linking: knowledge, ethics and social justice.

The ABP or PBL is conceived as a didactic strategy that promotes self-directed learning and develops in students: holistic understanding of problems; cooperative work in small groups; communication skills and stimulation of independence; information search skills; and analytical, synthesis and knowledge building capabilities based on collective work (MORENO; SIERRA, 2011). The ABP or PBL, in agreement with Poot-Delgado (2013), requires the elaboration or sharing of problems, preferably real and difficult to solve, that start from a learning need detected by the teacher and that are interesting and motivating for students so that they locate information to solve them. For its effective application in administration and related fields it is recommended to have: knowledge of the real problem by the teacher and the student; a detailed characterization of the problem and a design of guiding questions by the teacher; student commitment to search information related to the case; and structuring the approach to the problem and its possible resolution in several pedagogical moments.

The presented strategies constitute pedagogical initiatives that pursue not only personal fulfillment, but, mainly, life ethics, professional and social commitment, all in perspective of the contexts, knowledge and related previous experiences. It is important for this article to recognize that these strategies are bets that link uncertainty and continuous challenge. As it was correctly expressed by Shön (1987), it is not applying theories and techniques that the professional solves the problems present in his practice; there will be moments of uncertainty or conflict of values in which the teacher will have to improvise and create. Here, teacher training and, in particular, learning by doing or tutorials, according to Shön, can be part of the solution.

Teaching resources

In the training process, teaching resources play an essential role, as they constitute the intended procedures that actors define and design for the promotion and achievement of meaningful learning (DÍAZ, 1999). These academic and sociocultural devices operate as central mediators between the training purposes and the interests and needs of the students. They imply a guide for decision-making and action on how to guide training in contexts where the modes of learning of the subjects are heterogeneous, changing and multiple.

From this perspective, the resources for teaching refer to the procedures, tools, instruments and materials that are created and used to stimulate, approach and guide the student in meaningful learning. In particular, the following resources are privileged from the review of the literature for administration and related subjects: teaching materials; game for pedagogical purposes; and movies, videos and images.

Teaching materials

Gorbanev (2012), taking up contributions from Ausubel, Novak and Hanexian, values for the administration and related fields, the teaching materials to promote meaningful learning. He proposes that all material express the learning objectives clearly and relates the new knowledge to the knowledge already existing in the student. In a cognitive structure from which he learns in a non-arbitrary or linear way, he proposes that the material be stimulating because motivation is the mechanism that allows the student to relate existing knowledge to new knowledge. It also states that the material should be of reasonable size because its size determines the difficulty of the task and the motivation of the student.

For its part, Ventura (2011) calls for a more equitable training based on introducing certain criteria and pedagogical actions. For this achievement he recommends rethinking the types of materials; the mode of presentation; the forms of communication and participation promoted; and the type of perspective of the exhibition (drawings, photos/words, active/reflective, sequential/sensitive styles). Moreira (2013) adds that the teacher should encourage learning from materials such as: stories, poems, works of art and all those materials other than conventional textbooks.

Games for pedagogical purposes

For Abt (1970 apud TSEKLEVES; COSMAS; AGGOUN, 2016), serious games are understood as games that are not intended for fun, but have been designed and used for eminently educational purposes. Tsekleves, Cosmas and Aggoun (2016) add that serious games have been used in different areas, including the corporate, and are associated with game-based learning (GBL) because both are aimed at generating learning processes. They differ by the type of games used. The former use the platforms of the new technologies, and the second varied gaming platforms, including traditional tabletops and videogames.

The authors mentioned above find potential in serious games in aspects such as: encouraging and facilitating effective learning; and generate problem solving skills. They propose that, given their potential for problem solving, it is necessary to establish a “[…] common policy for the adoption and use of the PBL methodology for the design and development of serious games” (p. 168), so that the educational value of the game is clearer for educators, managers and parents, differentiated from mere educational entertainment.

Movies, videos and images

Looking for a break between preconceptions and more conservative stereotypes that students may have on different topics related to administration and related fields, Aktouf (2005) uses and suggests films and excerpts from television news (also press clippings) to contradict and discuss aspects such as “[...] the leader exists to do good, that the company exists to create jobs, to meet needs” (p. 156). It specifies that teaching in specific fields needs to be for change and, in the future, should be integrated into a broader social project. Meanwhile Flacso Argentina (2015), from the Center for Studies on the School and Intergenerational Links, proposes the use of images by the “[…] border crossing and at the same time as an area of meetings between young people and adults, to interrogate (and interrogate ourselves) the plots and cracks that occur in these territories” (s. p). Pedagogically it is proposed as an exchange of ideas on the basis of certain approach criteria, each meeting has a specialist commentator that facilitates the analysis and joint debate between the participants.

It brings to the reflection, the experience of Brooks and Hershock (2015) that linked the video to their classes. They propose to use it as a preamble to introduce themes or as a provocateur of analysis and postures that set the trend in certain subjects and in the lives of students “[…] to have a brief discussion about what singers do in the videos, the messages that they try to get to the other side [...] in large groups we write a thesis statement that generalizes the persuasion that is sought with each video” (s. p).

It is proposed to think the resources for teaching, beyond focusing on its instrumental and technical use, that is, from its generative role of meaningful and transformative pedagogical practices of the subjects, the institutions and their contexts. From this perspective it becomes very important to think about the teaching materials, the game, the video, the photography, the story, the poetry, among others, as possibilities to represent life, to deliberate on it and, especially, to co-produce it from more democratic, fair and sustainable perspectives.

Interactions in class

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, the training process is primarily a transformative and relational act. In this process the educational subjects coexists, negotiates, builds and communicates by generating interactions that allow them to display their cognitive and emotional skills, as well as their personal skills with autonomy, always in situated and relational contexts. From this perspective, teachers and educational organizations are invited to reflect critically on the dynamics that occur within the classroom and that have to do, among other aspects, with the layout of the classroom and its relationship with participation, dialogue and collective work.

From the model of communicative interaction, attention is drawn to the need to be more interested in the interrelations established between teacher-student and student-student. For the first case, according to Domínguez (2011), these relationships must be based on joint collaboration and coordination, based on: question and answer exercises; motivation for qualified participation; and design and implementation of strategies that promote increasingly autonomous learning. In the case of student-student relations, joint work must be promoted; selfless help and cooperation; the confrontation of points of view; as well as controversies and dissent. In the case of this article, it is important to make special mention of the interactions that could be encouraged with: the question and the arrangement of the classroom.

The question

The authors Elder and Paul (2002) give importance to the use of the question as an aspect that drives thinking. Specifically they propose the analytical question as an activity to be incorporated into pedagogical practices emphasizing the need to promote it in students. As a procedure they propose to start from the following components of reason and question the purposes of thought: understand where the idea arises from; presume that the information that supports thought is not fully understood; question the conclusions, concepts and ideas, assumptions, implications and consequences, points of view and perspectives. For example, through the following questions: What is your data based on?; Can you explain your reasoning?; Have you considered the implications of your conclusions? What is sought here is to deconstruct thinking, to examine specific facts and understandings that allow the argument to be improved from analysis and evaluation.

As a result of previous research exercises (CARREÑO; DURÁN, 2017), the authors of this article have found that the questions generate motivation, reflection and contextualized and relevant participation for the students. The power of the questions is that it is a mechanism that aspires to provoke in the student astonishment, new interpretations and the ability to think differently from new experiential and conceptual references. In terms of Freire (1990 apud GIROUX, 1997) it would be the “[…] open attitude towards all issues, their curiosity, their doubts, their uncertainty regarding certainties, their value for taking the risk and their rigorous methodological and theoretical approaches applied to important issues”(p. 29).

The classroom layout

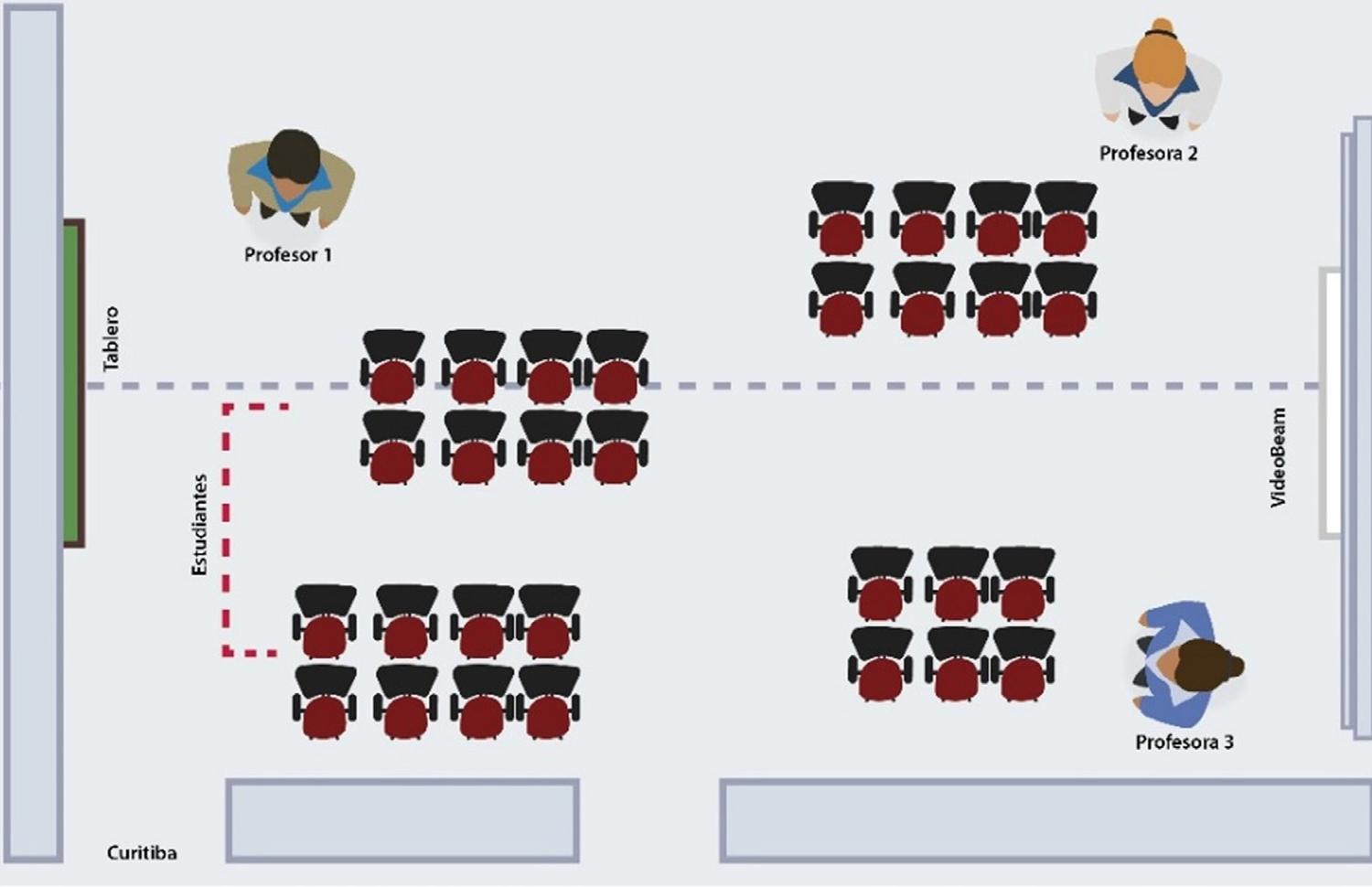

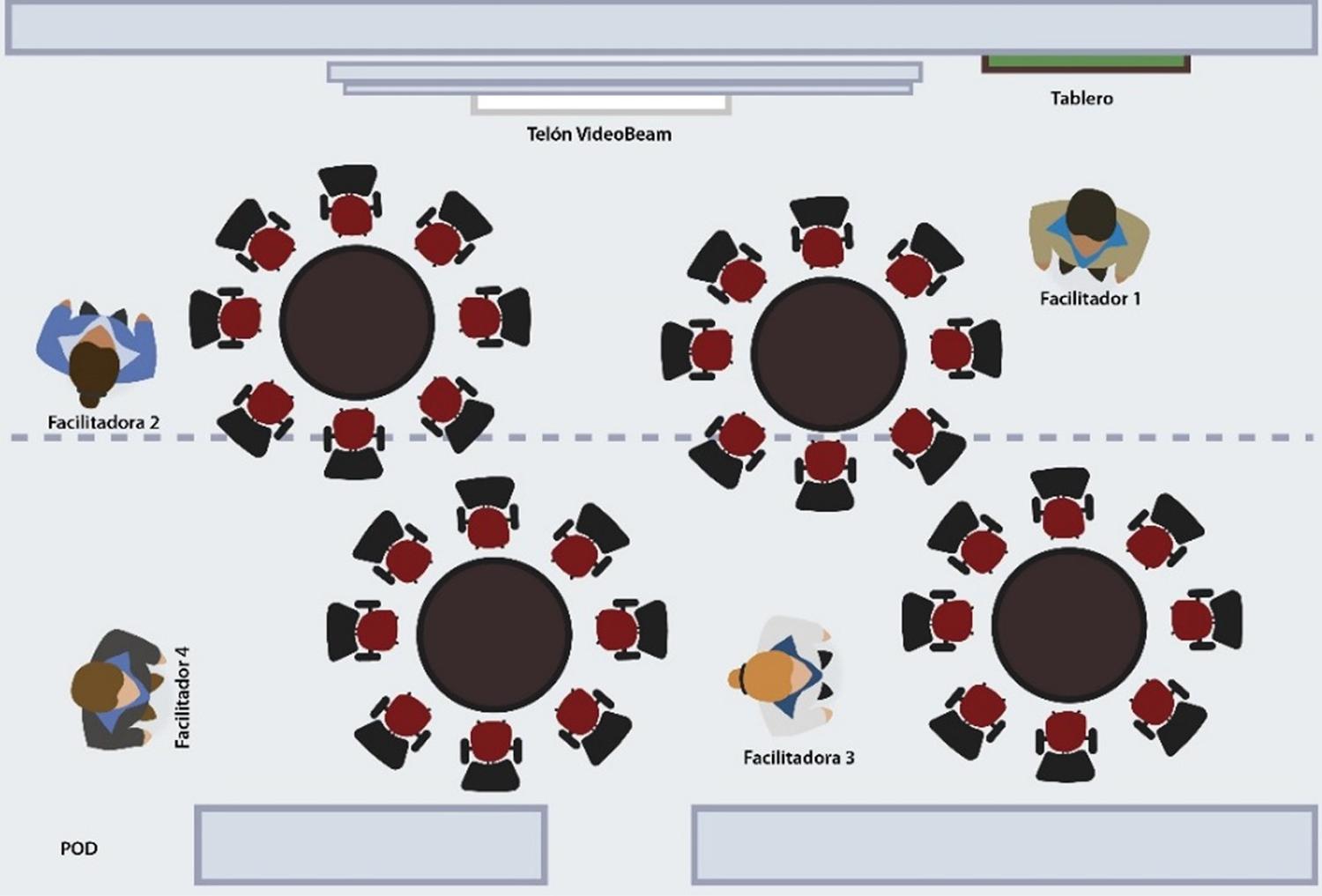

An investigation not published so far by the authors identified some important elements in the perspective of generating quality training processes in postgraduate and related postgraduate courses. This is how, after observing a series of classes in Curitiba and San Francisco (see figures 1 and 2), classrooms designed for teamwork, among equals, in collaboration to develop joint tasks were identified. Unlike the layout of a regular class (narrow classrooms with fixed chairs), these, due to their large space, location of teachers and layout of chairs and resources, predisposes the group for collaborative work and interaction.

In terms of activities and resources (see figures 1 and 2) the following characteristics are identified. Figure 1: introduction to the topic with presentation of the session and video; presentation of the subject by video beam; use of research tools; work in groups; and a closing with questions and conclusions. Figure 2: introduction with a short intervention; presentation of the topic with video; work in subgroups with specific roles; discussion on the central subject in the groups and with teachers/counselors; and a closing with a plenary and conclusions by participants and counselors.

What is analyzed in these classes is that they are programmed as a team by two or more teachers with a high level of training as a product of research exercises that are also carried out together. In the course of the classes they mix the group proposal and the creation of each teacher, facilitator or counselor based on their teaching style. In this way, content, strategies, resources and environments are conducive to put into dialogue those referents and theoretical debates that motivate the relevant and critical learning, which ultimately allow them to grow professionally. In this sense it is important for the teacher, by asking about what and why he teaches what he teaches, to set the conditions for that achievement. Aspects such as interest in students; the selection, use and delivery of materials; the arrangement of the chairs; the provocation of the encounters and the conversation between the students; among others, are essential decisions because it will be a learning that the graduate will apply in his personal and professional activity.

Conclusions and closing

This article presents some contributions on pedagogical strategies, teaching resources and classroom interactions from the perspective of a training process anchored in pedagogical practices inspired by meaningful, self-regulated and deliberate learning in postgraduate courses and particularly, in administration and related fields. Three main findings are revealed: pedagogical and didactic openness for training work; patterns of reflection on teaching activity; and observations and invitation to managers to think about the administration and related teachings with a cognitive, social and ethical transcendence and, in this perspective, teacher training is incorporated and strengthened as a generating environment for new and innovative pedagogical practices.

With regard to pedagogical and didactic openness for formative work, attention is drawn to the need to transcend the rational and technical domain of knowledge, in order to include autonomy (FREIRE, 1999), deliberation (GIROUX, 1997) and transformation (EUSSE; BRACHT; ALMEDIDA, 2016) as foundations of the educational act. A special mention is made in valuing the teacher as a teacher-craftsman (ALLIAUD, 2017) and in this context three modes of meaningful learning are suggested, namely: the programming and management of participatory activities; interdisciplinary learning; and collaborative learning.

With regard to the guidelines for reflection on teaching work, emphasis is placed on conceiving teaching resources as academic and sociocultural devices (DÍAZ, 1999), with the particularity of operating as central mediators between the interests and needs of the students and the specific training purposes of the classes. It is emphasized that the teaching materials are designed and executed taking into account that the subjects who participate in the training process have history, values and have autonomy. In the same way, it is valued to conceive and use the games, movies, videos and images from and with pedagogical purpose, that is, recognizing their formative, democratic and deliberative force. Finally, you are invited to reflect critically on the interactions that energize the classes, this from a transformative and relational sense horizon. In particular, resorting to the majesty or art of the question; the educational connections or plurality of relationships that converge in the formative act; and the layout of the classroom.

Finally, managers, teaching and learning centers and teachers are invited to prioritize policies and plans in teacher training or teacher development projects aimed at reflecting on teaching, as well as strengthening a much deeper understanding of what their teaching work means for their individuality, and in their relationship with their peers and other actors involved, in their interdependence with the environment. It is shared with Hidalgo (2007) that organizations must accompany, propose and put into programs for the improvement of teacher performance, a “[...] policy for teacher training, updating and training and evaluation of teacher performance” (p. 9) that has a budget and makes possible the purposes devised by the educational community.

REFERENCES

ALLIAUD, Andrea. Los artesanos de la enseñanza: acerca de la formación de maestros con oficio. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2017. [ Links ]

ALONSO, Cristina et al. De las propuestas de la administración a las prácticas del aula. Revista de Educación, Madrid, v. 12, n. 35, p. 53-76, 2012. [ Links ]

AKTOUF, Omar. Ensino de administração: por uma pedagogia para a mudança. Organizações & Sociedade, Salvador, v. 12, n. 35, p. 151-159, 2005. [ Links ]

BAILEY, James; FORD, Cameron. Management as science versus management as practice in postgraduate business education. Business Strategy Review, London, v. 7, n. 4, p. 7-12, 1996. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análisis de contenido. Madrid: Akal Universitaria, 1986. [ Links ]

BROOKS, Judy; HERSHOCK, Chad. Creating instructional videos that actually work… 2015. San Francisco: [s. n.], 2015. Conferencia impartida en la 40TH Annual Pod Conference. San Francisco, California, noviembre 4-8, 2015. [ Links ]

CAÑEDO, Teresa et al. Evaluando la enseñanza en el posgrado. Reencuentro, México, DF, n. 53, p. 63-74, 2008. [ Links ]

CARREÑO, Claudia Inés. Lo pedagógico en los posgrados sobre desarrollo: dos estudios de caso. 2012. (Tesis Doctorado en Ciencias de la Educación) – Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata, 2012. [ Links ]

CARREÑO, Claudia Inés; DURÁN, Armando. Desafíos de la enseñanza en los estudios del desarrollo. In: PINEDA DUQUE, Javier A; HELMSING, Berth; SALDÍAS, Carmenza. Universidad y desarrollo regional: aportes del CIDER en sus 40 años. Bogotá: Uniandes, 2017. p. 243-262. [ Links ]

CARREÑO, Claudia Inés; DURÁN, Armando. Reflexiones sobre la enseñanza de la gestión urbana: un ejercicio necesario para construir la ciudad. Urbe, Curitiba, v. 7, n. 1, p. 136-147, 2015. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, Jhon. Research desing: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4. ed. London: Sage, 2014. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, Jhon; POTH, Cheryl. Qualitative inquiry research desing: choosing among five approaches. London: Sage, 2018. [ Links ]

DENZIN, Norman; LINCOLN, Yvonna. The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: DENZIN, Norman; LINCOLN, Yvonna (Ed.). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage, 2005. Introduction. [ Links ]

DEWEY, Jhon. Democracia y educación: una introducción a la filosofía de la educación. Madrid: Morata, 1920. [ Links ]

DÍAZ, Frida. Estrategias docentes para un aprendizaje significativo: una interpretación constructiva. México, DF: McGraw-Hill, 1999. [ Links ]

DOMÍNGUEZ, María Alejandra A. Los modos de intercambios de significados en clases de física secundaria: procesos de negociación. 2011. (Tesis Doctorado en Ciencias de la Educación) – Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 2011. [ Links ]

ELDER, Linda; PAUL, Richard. El arte de formular preguntas esenciales. Boston: Foundation for Critical Thinking. 2002. [ Links ]

ELLIOT, Jhon. La investigación-acción en educación. Madrid: Morata, 1990. [ Links ]

EUSSE, Karen; BRACHT, Valter; ALMEIDA, Felipe. A prática pedagógica como obra de arte: aproximações à estética do professor‐artista. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, Brasília, DF, v. 38, n. 1., p. 1-104, 2016. [ Links ]

FLACSO ARGENTINA. Ciclo de cine: el cine como metáfora pedagógica. Buenos Aires: Flacso, 2015. Disponible en: < http://plyse.flacso.org.ar/agenda/ciclo-de-cine-el-cine-como-metafora-pedagogica-1> . Acceso en: 3 dic. 2015. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Cartas a quien pretende enseñar. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno, 1997. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogía de la autonomía. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno, 1999. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogía de la esperanza. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno, 1993. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. Los profesores como intelectuales. Barcelona: Paidós, 1997. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ, Marleny. Formación docente en competencias TIC para la mediación de aprendizajes en el proyecto Canaima Educativo. Telos, Maracaibo, v. 18, n. 3, p. 492-507, 2016. [ Links ]

GORBANEV, Iouri. Una tipología de casos para enseñar la Administración. Semestre Económico, Medellín, v. 15, n. 32, p. 185-196, 2012. [ Links ]

GRISALES-FRANCO, Lina María; GONZÁLEZ-AGUDELO, Elvira María. El saber sabio y el saber enseñado: un problema para la didáctica universitaria. Educación y Educadores, Bogotá, v. 12, n. 2, p.77-86, 2009. [ Links ]

GUBER, Rosana. El salvaje metropolitano: reconstrucción del conocimiento social en el trabajo de campo. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2001. [ Links ]

HIDALGO, Laura. Escenario posible del desempeño profesoral en la enseñanza en una institución de formación docente. Revista Electrónica Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, Costa Rica, v. 7, n. 2, p. 1-16, 2007. [ Links ]

JACKSON, Philip. Práctica de la enseñanza. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2002. [ Links ]

KLAFKI, Wolfgang. El análisis didáctico como el alma de la formación para la enseñanza. Traducción de Stella Cols como material para la enseñanza. Buenos Aires. (s.f.). No publicada. [ Links ]

LITWIN, Edith. El oficio de enseñar: condiciones y contextos. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2008. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ, María del Mar; PÉREZ, Rosario. La valoración del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en los grados de economía y administración de empresas. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, Salamanca, v. 13, n. 3, p. 190-219, 2012. [ Links ]

LUNDGREN, Ulf. Between education and schooling: outlines of a diachronic curriculum theory. Geelong: Deakin University Press, 1991. [ Links ]

MACLEOD, Flora; GOLBY, Michael. Theories of learning and pedagogy: issues for teacher development. Teacher Development, London, v. 7, n. 3, p. 345-362, 2003. [ Links ]

MALDONADO, Marisabel. El trabajo colaborativo en el aula universitaria. Laurus, Caracas, v. 13, n. 23, p. 263-278, 2007. [ Links ]

MARROU, Henry-Irenee. Historia de la educación en la antigüedad. Madrid: Akal, 1985. [ Links ]

MATURANA, Humberto; NISIS, Sima. Formación humana y capacitación. Palma de Mallorca: Dolmen y Tercer Mundo, 1997. [ Links ]

MONTENEGRO-VELANDIA, Wilson et al. Estrategias y metodologías didácticas, una mirada desde su aplicación en los programas de administración. Educación y Educadores, Bogotá, v. 19, n. 2, p. 205-220, 2016. [ Links ]

MORALES, Juliana; CARREÑO, Esmith. CIDER: una historia de cooperación internacional y de estudios interdisciplinarios. In: PINEDA DUQUE, Javier A; HELMSING, Berth; SALDÍAS, Carmenza. Universidad y desarrollo regional: aportes del CIDER en sus 40 años. Bogotá: Uniandes, 2017. p. 243-262. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Marco Antonio. Aprendizagem significativa subversiva. Série-Estudos, Campo Grande, n. 21, p. 15-32, jun. 2013. [ Links ]

MORENO, Manuel Antonio; SIERRA Alvaro. Uso del aprendizaje basado en problemas en administración: análisis del uso de aprendizaje basado en problemas en el programa de administración de empresas de la Fundación Universitaria Sanitas. 2011. (Trabajo de Grado) – Universidad de la Sabana, Sabana. 2011. [ Links ]

PÉREZ, Ángel; GIMENO SACRISTÁN, José. Comprender y transformar la enseñanza. 7. ed. Madrid. Morata. 1992. [ Links ]

PFEIFFER, Ernesto. Gabriela Mistral, pasión de enseñar: pensamiento pedagógico. Valparaiso: Universidad de Valparaiso, 2017. [ Links ]

POOT-DELGADO, Carlos Antonio. Retos del aprendizaje basado en problemas. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología, Zalapa, v. 18, p. 307-314, 2013. [ Links ]

QUIROGA, Francisca; SHUSTER, Sofía. Innovación en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje en la carrera de administración pública: la experiencia de los talleres profesionales, Revista Didasc@lia , Las Tunas, v. 1, n. 1, p. 139-154, 2013. [ Links ]

REPKO, Allen. Interdisciplinary research: process and theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2012. [ Links ]

SHÖN, Donald. La preparación de profesionales para las demandas de la práctica. In: SHÖN, Donald (Org.). La formación de profesionales reflexivos: hacia un nuevo diseño de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje en las profesiones. Barcelona: Paidós, 1987. p. 1-15. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, Anselm; CORBIN, Juliet. Bases de la investigación cualitativa: técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, 2002. [ Links ]

TEJADA, Ángel et al. Análisis de la tasa de éxito en la asignatura de contabilidad de costes. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, Valencia, v. 10, n. 3, p. 347-377, 2012. [ Links ]

TRIGOS-CARRILLO, Lina. El uso de métodos etnográficos como herramienta de apoyo… Bogotá: Red Innova Cesal, 2013. Conferencia impartida en el Foro internacional de innovación docente. [ Links ]

TSEKLEVES, Emmanuel; COSMAS, John; AGGOUN, Amar. Benefits, barriers and guideline recommendations for the implementation of serious games in education for stakeholders and policymakers. British Journal Of Educational Technology, Kingdom, v. 47, n. 1, p. 164-183, 2016. [ Links ]

VENTURA, Ana Clara. Estilos de aprendizaje y prácticas de enseñanza en la universidad: un binomio que sustenta la calidad educativa. Perfiles Educativos, México, DF, v. 33, p. 142-154, 2011. [ Links ]

VILCHES, María de los Ángeles; FERNÁNDEZ, Alfonso; MARTÍNEZ, Francisco. Ecopedagogy: a movement between critical dialogue and complexity: proposal for a categories system. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, London, v. 10, n. 1, p. 178-195, 2016. [ Links ]

WASSERMANN, Selma. El estudio de casos como método de enseñanza. Buenos Aires: Amarrou, 1994. [ Links ]

WILLS, Eduardo. El CIDER y el Plan Nacional de Rehabilitación: dos emprendimientos institucionales entrelazados. In: PINEDA DUQUE, Javier A; HELMSING, Berth; SALDÍAS, Carmenza. Universidad y desarrollo regional: aportes del CIDER en sus 40 años. Bogotá: Uniandes, 2017. p. 243-262. [ Links ]

WORTHEN, Molly. Lecture me. Really. New York Times, Nueva York, Oct. 18, 2015. Disponible en: < https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/18/opinion/sunday/lecture-me-really.html?mwrsm=Facebook&_r=1> . Acceso en: 18 oct. 2015. [ Links ]

3- The results achieved at that moment were obtained in the first phase of the research . Postgraduate education at the School of Administration of the ‘Universidad del Rosario’. An approach from their pedagogical practices. Special thanks to Stéphanie Lavaux and José Alejandro Cheyne who for that time were, respectively, the Vice Chancellor of the ‘Universidad del Rosario’ and Dean at the School of Administration at the same university

Received: August 22, 2018; Revised: May 08, 2019; Accepted: August 20, 2019

texto em

texto em