Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 06-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046216262

SECTION: ARTICLES

Intercultural competences: conceptual dialogues and a reinterpretation proposal for higher education *

1- Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil . Contato: fabianecl@uol.com.br; fabianeclemente@ufam.edu.br.

2- Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil . Contato: marilia.morosini@pucrs.br.

Intercultural competences in higher education, especially in Brazil, is an incipient theme despite its long-lasting importance and its indisputably rich cultural framework. An environment with a predominance of the functional perspective of interculturality (CANDAU, 2012; WALSH, 2009) still lacks reflections on the development of knowledge about the themes that permeate it. This article sought out a conceptual dialogue about intercultural competences in higher education, based on qualitative and exploratory bibliographic research, incorporating the main national and international publications about the subject. Conceptual reflection stemmed from discussions about skills and interculturality, as well as the combination of the two concepts (intercultural skills) in higher education. Therefore, it was possible to perform a reinterpretation based on competences concepts from the perspective of inputs (predominant North American trend with focus on the set of characteristics of the subject) and outputs (predominant European trend with focus on results) and interculturality (interaction between cultures) with classification concepts as relational, functional and critical described by Walsh (2009). From this research, new discussions and perspectives on the subject have been presented, as well as empirical studies that will aggregate the results presented here, in addition to the search for didactics aimed to develop intercultural competences that can be implemented in Higher Education.

Key words: Intercultural competences; Competences; Interculturality; Higher education

Competências interculturais na educação superior, em especial brasileira, constitui um tema incipiente apesar de sua importância longínqua e de ser um espaço indiscutivelmente composto de um rico arcabouço cultural. Ambiente com a predominância da perspectiva funcional da interculturalidade (CANDAU, 2012; WALSH, 2009), ainda carece de reflexões acerca do desenvolvimento de saberes sobre as temáticas que a permeiam. Este artigo buscou uma interlocução conceitual acerca de competências interculturais na educação superior, a partir de uma pesquisa bibliográfica do tipo qualitativa e exploratória, apropriando-se das principais publicações nacionais e internacionais a respeito do tema. A reflexão conceitual partiu de discussões acerca de competências e interculturalidade , bem como a junção dos dois construtos (competências interculturais) na educação superior. Portanto, foi possível realizar uma releitura com base nos conceitos de competências na ótica de inputs (corrente predominante norte-americana com ênfase no conjunto de características do sujeito) e outputs (corrente predominante europeia com foco nos resultados) e da interculturalidade (interação entre culturas) com concepção de classificação como relacional, funcional e crítica de Walsh (2009). Entende-se que a partir desta pesquisa sejam incitadas novas discussões e olhares acerca do tema, bem como estudos empíricos que venham agregar os resultados aqui apresentados, além de incentivar a busca por didáticas a serem implementadas que visam ao desenvolvimento de competências interculturais na Educação Superior.

Palavras-Chave: Competências interculturais; Competências; Interculturalidade; Educação superior

Introduction

In a context full of languages, artifacts, races, religions, dialects, customs, distinct beliefs, the world is becoming increasingly globalized and the existence of cultural heterogeneity cannot be denied. Brazil alone presents an immense cultural framework as a place with unique experiences due to its extensive geographical boundaries. Such complexity is accompanied by issues that spring up daily in this context. Within this vision, interculturality is applied, which is the interaction (considered in different forms) between cultures.

Several questions bring to light interpretations and understandings of studies that are developed to answer the questions that arise within the intercultural context. Educational institutions, including universities, are places that focus on the formation of people. This involves competences that can be developed from a conceptual and practical medley that carries intercultural aspects within it, especially in the educational context where these skills are developed. “Education is not only a human right but also a right of peoples” ( CRES, 2018 , p. 8).

Therefore, this research aimed to propose a conceptual dialogue about intercultural competences (IC) in higher education (HE) based on a literature review. To meet this objective: a) we analyze the concepts of competences; b) we discuss the concepts of interculturality and; c) we reflect on the dialogue between concepts from the perspective of higher education, presenting a reinterpretation of the term intercultural competences.

The IC theme in higher education is considered a precise aspect when it comes to delimiting a theme, which is increasingly important due to the undeniable changes that have been occurring in Brazilian HE, such as: expansions of the internalization process; institutional diversification; globalization; internationalization; new members, among others ( MOROSINI, 2014 ).

Institutions in this context no longer prefer to study this theme. As Deardorff (2006) states, this is not a process that develops naturally, which is why it requires intentional actions within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Thus, the author argues that there needs to be an evolution in the concept and an effort for research and practice to remain up to date with studies and processes that are based on this concept.

Methodological path

The study was basic, qualitative, and exploratory with bibliographic research to construct the analysis that allowed the proposition of reinterpretation of IC in higher education. Basic research ( GIL, 1999 ) aims to discuss theories and develop new knowledge from a theoretical reflection. The qualitative study added to this process aimed to provide reflections that did not quantify data or meanings.

By analyzing publications (basic theorists, articles on the topic), the bibliographic research provided a perspective on the elaboration of propositions based on the theories and contributions published. For Gil (1999) , the documents establish the analysis of the research. Pizzani et al. (2012) point out that bibliographic research is an important technique that seeks to discuss the main theoretical themes that guide an area. The steps were based on Lima and Mioto (2007) , based on the parameters defined by the authors.

Regarding competences, we relied on the two main concept perspectives: input and output, based on Parry (1996) and Fleury, M.; Fleury, A. (2001) who discuss this classification, based on literature considered predominant in Europe (output) and the United States (input).

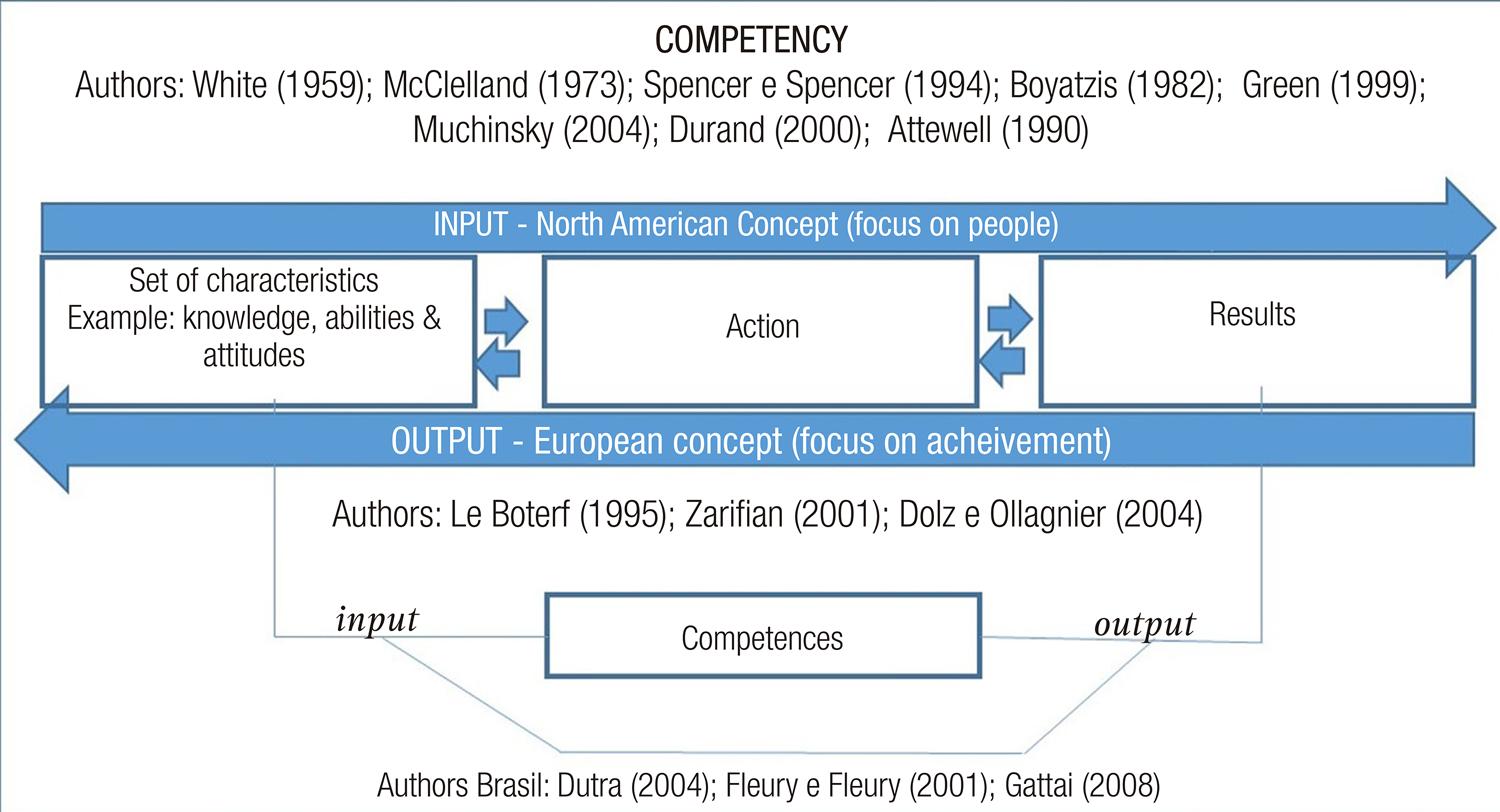

In both concepts, we used bibliographies that discuss competences in the Brazilian context, the main ones being: Dutra (2004) ; Fleury, M.; Fleury, A. (2001 , 2004 , 2004a ); Fernandes; Fleury (2007) . The two predominant themes were also analyzed using the international literature of White (1959) ; McClelland (1973) ; Spencer; Spencer (1994); Le Boterf (2005) ; Zarifian (2001) , Dolz and Ollagnier (2004) , considered classical authors of the two themes discussed. The discussions about competences constructed Figure 1 , which provides better visualization of epistemological themes involving this concept, with the two perspectives that guide the research. We also cite some education authors taken from Morosini, Cabrera and Felicetti (2011) .

Source: Created by the Authors (2018).

Figure 1 – Concept of competency from the input and output perspective

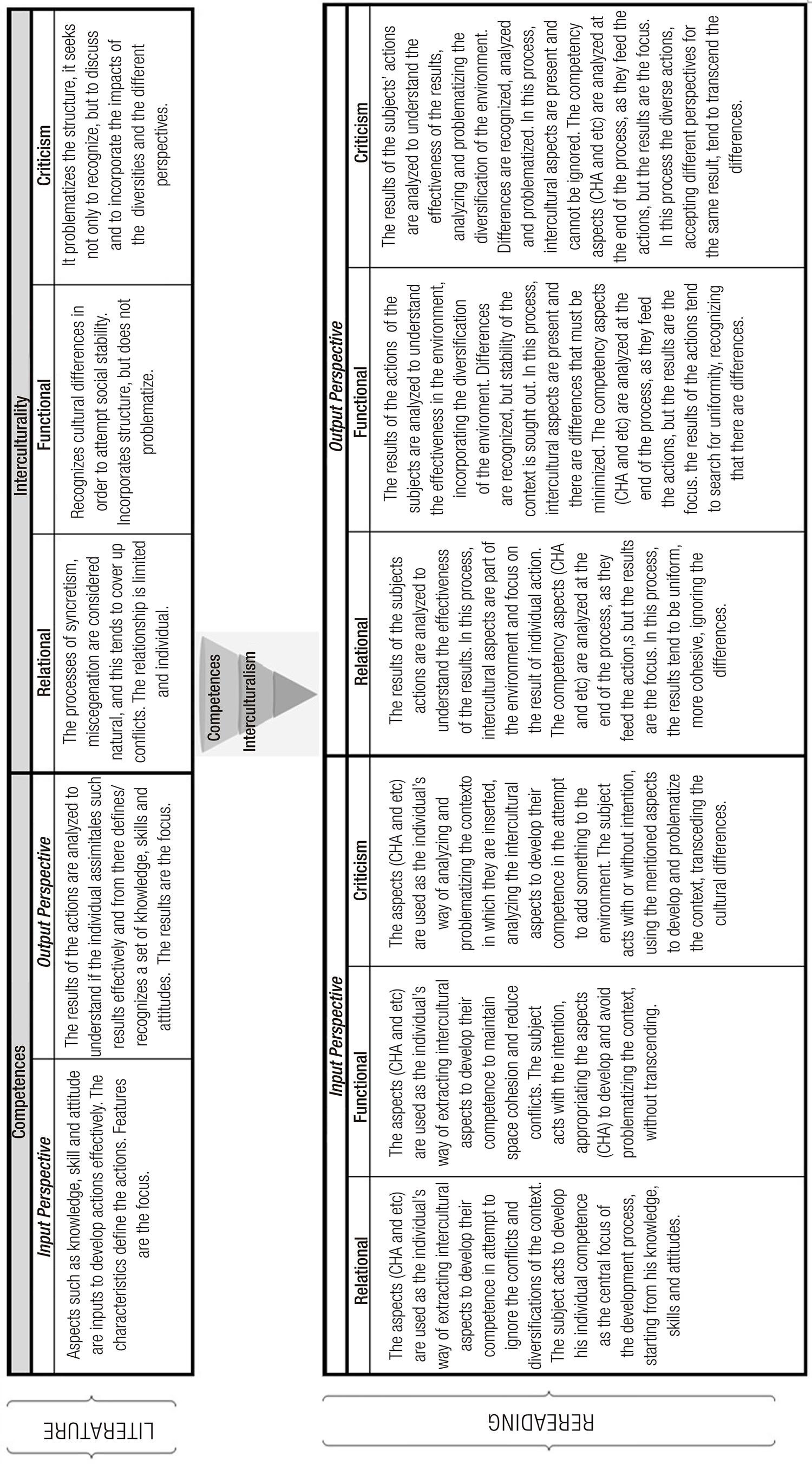

For discussions about interculturality, the main references associated with the Brazilian context that we adopted were Candau (2012 , 2016 ); Candau; Koff (2006) , Coppete, Fleuri and Stoltz (2012) , with the conceptual reference in Walsh’s Latin America vision (2009, 2009a) complementing Mato’s perspective (2008, 2016). Walsh was the key reference for discussing the perspectives of interculturality used here, which focuses on the three types: relational, functional and critical, being an axis of analysis associated with the themes of input and output perspectives, which make up Figure 2 .

Source: Created by the Authors 2018.

Figure 2 – Reinterpretation of intercultural competences in higher education

Given the scant amount of Brazilian literature on IC in higher education, we relied on the discussions of Deardorff (2004 , 2006 , 2009 ); Freeman et al. (2009) , Unesco (2002 , 2009 ), Dervin (2010) , Berardo; Deardorff (2012) , Huber; Reynolds (2014) . These works were chosen because they present current analyses on the subject and discuss both the historical concept of the theme, applications and methods, models, as well as studies aimed at education and higher education.

However, we sought epistemological surveillance, as defended by Lima; Mioto (2007 , p. 37), to “carry out a tireless movement to apprehend the objectives”. We also understand that research does not exhaust a particular concept. Since the methods used here are limited, empirical research that will further explore the proposal presented is needed.

Results & discussions

To present the reinterpretation and conceptual reflections, we chose to discuss intercultural competences by dividing it up. As Huber; Reynolds (2014) point out, to understand CI it is necessary to understand the related concepts. First, we debate the concept of competences, then interculturality and, finally, intercultural skills, thus providing a conceptual reflection with a reinterpretation for higher education.

Competences

McClelland (1973) was the first to start to elaborate the concept of competence in a structured way, searching for a more concrete approximation to select people for organizations compared to the previously used intelligence tests ( DUTRA, 2004 ).

Basically, at the individual level, competence encompasses the three basic pillars: knowledge, skill and attitudes (CHA). Durand (2000) points out that these three vertices must be interconnected, related to a certain purpose. He also argues that the values and beliefs shared by a team influence an individual’s behavior. This conceptual approach is apparently the most accepted when it comes to analyzing the work environment ( BRANDÃO; GUIMARÃES, 2001 ).

The French debate on the theme of competences arose in the 1970s, “precisely from questioning the concept of qualification and the process of professional training, mainly technical” ( FLEURY, M.; FLEURY, A., 2001 , p. 186), which did not satisfy the need of the market and the formation of these, thus, they took the debate to the educational field. One of the authors who sought to extrapolate the concept was Zarifian (2001) , who analyzed competence from various organizational perspectives by discussing technical, service, process and social skills.

Sá & Paixão (2013) discussed the polysemy of the concept from behaviorist and integrated approaches. Historically, White (1959) describes competence as personal characteristics and McClelland (1973) conceptualizes it as a characteristic underlying the subject, the latter being a reference of the concept as input (behaviorist). In the integrated approach (systemic and complex), authors such as Le Boterf (2005) describe the concept with a multidimensional vision. Authors of this theme as Zarifian (2001) and Dolz; Ollagnier (2004) also fit into this approach ( FERNANDES, FLEURY, 2007 , p. 106). The authors of the integrated approach are also considered advocates of the conceptual perspective of output.

Dutra (2004) and Fleury, M.; Fleury, A. (2001) sought to balance both perspectives. In the 1980s, in Brazil, the theme received relevance in studies that discussed competence of the individual and organization. Research was elaborated differentiating several concepts of competences (individual, professional, organizational, managerial), matrices, and management by competences. Such scenario is initially based on thinking about competence as input ( FERNANDES; FLEURY, 2007 ), which has become a predominant trend in Brazil. Therefore, competence is a knowing how to act responsibly and recognized, which implies “mobilizing, integrating, transferring knowledge, resources and skills, which add economic value to the organization and social value to the individual” ( FLEURY, M.; FLEURY, A., 2001 , p. 188).

The literature can also be assessed through the prevailing trends, either by approaches or in a territorial space such as the division of debates into “American and European”. Parry (1996) points out that in the United States, competence is considered input, treated as a set of characteristics that affect the actions of the subjects, while in Europe competence is considered output, that is, the individual demonstrates competence from the moment he/she can assimilate and overcome the results of his/her actions.

This classification in its conceptual essence (input and output) was adopted here as a reference to analyze the Intercultural Competences (IC) concept. Figure 1 seeks to demonstrate how the two perspectives (input and output) operate.

In the educational sphere, discussions about the theme are perceived as mainly individual competences, whether from the student’s, teacher’s or manager’s perspective. Morosini, Cabrera and Felicetti (2011) highlight some of the main authors who discuss competence in the education context: Delors (1996) , Sugumar (2009) , Rios (2001) , Braslavsky (1999) , Perrenoud (1999) , Goergen (2000) who discuss competences in regards to teaching competence, emphasizing that such approaches basically include two sides: “the unfolding (planning) and implementation (execution) of professional knowledge, as well as ideas and skills that the teacher possesses” ( MOROSINI, CABRERA; FELICETTI, 2011 , p. 232).

The next section reflects upon culture, multiculturalism and interculturality, with intercultural dialogues focusing on education as its central objective. We understand that discussions about culture, provided here in a broader sense, reinforce the complexity of the concept and intentionally do not focus on the minutiae of discussions about this topic in order to explain its main conceptual configuration, as the central focus is intercultural skills.

Culture, multiculturality & interculturality

Studies about culture are already comprehensive in the literature and increasingly subdivided. Hofstede (1980) is a prominent author in the study of national cultures. He defines culture as a collective phenomenon that is learned and not inherited. Some authors focus on studies about culture, its concepts, aspects and differences that permeate this context ( CLIFFORD; MARCUS, 1986 ; GEERTZ, 1973 ; KRAMSCH, 1998 ). Much cited in Brazil, Hofestde (1980) says culture is the collective programming of spirits that distinguishes the members of one human group from another. Other research on communication ( CRICHTON; SCARINO, 2007 ) and linguistic studies focus on the need for a shared understanding of language and its meaning(s) in use ( KRAMSCH, 1998 ).

Sousa Santos and Nunes (2003 , p. 3) highlight that the concept of culture can be seen from two perspectives: from the area of humanities, which deals with the term “in terms of value, aesthetic, moral or cognitive criteria, which, defining itself as universal, eliminates the cultural difference or historical specificity of the objects they classify.” The other perspective from the Social Sciences area, “recognizes the plurality of cultures, defining them as complex pluralities that are confused with societies”. ( SOUSA SANTOS; NUNES, 2003 , p. 3).

Tylor (1871) , who is considered a classical author and was one of the first to work on the concept of culture, highlights that Culture or Civilization, taken in its broad ethnographic sense, is a complex whole that includes knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, laws, customs or any other capacity or habits acquired by man as a member of a society. This concept was refuted by Franz Boas (anthropologist) ( MORGADO, 2014 ). Boas (1922) stressed that instead of a simple line of evolution, there appears to be multiple lines (convergent and divergent) that are difficult to join in a system. Instead of uniformity, its remarkable feature seems to be diversity.

Culture is not a power, but something to which social events, behaviors, institutions or processes can be casually attributed to. It is a context, something within which they (the symbols) can be intelligibly described – that is, described with weight. Understanding the culture of a group of people exposes their normality without reducing their particularity ( GEERTZ, 1973 ). The concept by UNESCO (2002) is also worth highlighting, which considers culture as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and affective traits that characterizes a society or a social group.

From various perspectives, culture bring an indescribable and singular complexity as it permeates a certain context. This includes values, beliefs, knowledge, symbols that emerge in a given space and that are recognized by individuals within that space. Conceptual polysemy is driven by the ideas of multiculturalism and interculturality that are also found in a tangle of diverse discussions and understandings.

Multiculturalism and interculturality can be considered distinct concepts, but with similar characteristics. Backes (2013 , p. 53) points out that:

[...] doubts persist about whether the most productive concept is interculturality or multiculturalism and the recognition that these are polysemic and multipurpose concepts is accompanied by an effort to reduce polysemy, using different types of multiculturalism.

Therefore, in the literature there are many debates that approach and differentiate these concepts, as seen in Candau; Koff (2006) , who cite Jordan (1996) , McLaren (2000) , Banks (1999) , Forquin (2000) , among others.

There are also different views on multiculturalism, multiculturality, interculturalism and interculturality. In an attempt at a more generalized concept, multiculturalism can be defined as a set of cultures in a given society ( KREUTZ, 1999 ). Sousa Santos and Nunes (2003) also highlight that the term was initially designated as the coexistence of groups characterized by different cultures. Since it is a polysemic term, it can also be interpreted from different perspectives, providing discussions about cultural diversity, assimilation, even as the perspectives considered as critical called critical multiculturalism and critical interculturality ( McLAREN, 2000 ). Therefore, multiculturality can be understood as a contemporary expression of the way of thinking about cultural multiplicity, which is a complex entity that has been marked by power relations ( ROJAS, 2008 ).

Despite the various trends of theoretical discussions, an approximate concept of interculturalism was described by Reyna (2007 , p. 435). For the author, interculturalism can have two meanings, one being the “theoretical theme of the phenomenon of interculturality, indicating a field of study” and another refers to the “possibility of being a political project of relations between different cultures”.

Interculturality, however, in addition to the set of cultures, requires interaction, interrelationship and dialogue between them. It offers the basic concept of interaction between cultures or cultural aspects, as well as emphasizes Kreutz (1999) . This concept guided the discussion of this research, understanding that interaction can be understood in several ways.

In the context of education, also called intercultural education, which is a theme that has been expanding in Latin American, based on reflections and studies by some authors, including Walsh (2009 , 2009a ), there are three basic concepts: relational, functional and critical. The relational concept considers the processes of syncretism and miscegenation as natural, which tends to cover up conflicts and the relationship is limited and individual. The functional view recognizes cultural differences in order to reach social stability.

Critical interculturality problematizes the structure. Walsh (2009 , p. 03) emphasizes that a critical perspective of interculturality is like a tool that “points out and requires the transformation of structures, institutions and social relations, and the construction of conditions of being, knowing, learning, feeling and living differently.”To be possible, it must be a project of society. For the author, when we talk about the Latin American context, we are evolving and for that, it is not enough to recognize the different. This is the trend that assumes diversity as the central axis, starting from the problem of power, seeking a discussion from the decolonial perspective.

We frame the concepts discussed and analyze IC from both the input and output competences perspective, as well as in the discussions of relational, functional and critical interculturality. Next, we present discussions about IC and our reinterpretation about the concepts from the adopted definitions.

Intercultural competences

Within the various ways of analyzing competences or their variations that incorporate particular perspectives such as interculturality, it is understood that Intercultural Competences merges the two concepts and that the literature has been discussing and evolving to incorporate new variables such as internationalization since the 1950s (USA).

Among the various conceptual interpretations, the first project to document consensus among experts in Intercultural studies in the United States (USA), with regard to intercultural competence, sought an interactive process used to obtain consensus among a panel of experts. The beneficial aspects were categorized and placed in a model that is based on the evaluation and development of detailed measurable learning outcomes. Specifically, this model was based on the development of specific attitudes, knowledge and skills inherent to IC learning ( DEARDORFF, 2009 ).

In addition to this model, others have been used to frame aspects of intercultural learning, such as Bennett’s Development Model for Intercultural Sensitivity (1993), the King’s Model and Baxter Magolda’s intercultural maturity model (2005), and the Cross Transcultural Continuum (1988). All of these models describe stages of growth ( BERARDO; DEARDORFF, 2012 ).

Several academic definitions of IC have been provided. For Dervin (2010) , the most comprehensive was presented by Byram (1997) who included five IC components and was thus characterized by Dervin for having clear objectives, but also for presenting difficulties in evaluation ( BYRAM, 1997 ; KRAMSCH, 1993 ). For UNESCO (2009) , IC’s are resources put in practice during intercultural dialogue.

Intercultural competence, especially in the teaching-learning process in formal education, can be seen as the ability to develop one’s tasks or functions efficiently in multicultural contexts ( ALVAREZ, 2005 ). This also provides us with a context that is not only professional but rethinks the proper exercise of citizenship. Intercultural learning is transformative and requires experiences (often beyond the classroom) that lead to this transformation ( DEARDORFF, 2009 ).

Authors who work with models such as Spitzberg; Changnon (2009) establish 5 types and discuss the concept of IC construction. Pascarella (1985) worked with a model focused on variables in the student’s learning process; Deardorff (2006) studied IC components; Fantini (2007) directed efforts to develop Intercultural Competence Assessment (ICA) and Schnabel et al. (2015) tried to create an instrument to measure IC.

In his study with academics and specialists, Deardorff (2006) identified 22 IC components, concluding that the interviewees prefer a more general concept and did not define competence in relation to specific aspects. Huber and Reynolds (2014) also provided a set of items, but was already classified in attitudes, knowledge and understanding, skills and actions.

Discussions of the American Council On Intercultural Education ( ACIE, 1996 ), which deals with global competence and being globally competent, considers competence as a skill, knowledge or an attitude that can be demonstrated, observed or measured. In this discussion, it is argued that the formation of competence is a continuum and should be developed in all stages of education, not just higher education. An individual may perform various degrees at each stage and progress may not be linear.

This directs the development of research towards a better understanding in the Brazilian academic context, within the perspective of the modus operandis of the discussion of practices that may develop IC in the student’s education.

It is important to note that learning intercultural skills is a cyclical process. To teach about something, you have to know and learn about it. However, IC learning is sought throughout its existence ( DEARDORFF, 2009 ; DERVIN, 2010 ). This emphasizes the importance of learning to live together within education, not exclusively in higher education. The development of IC in higher education cannot be limited to ensuring spaces for students and teachers but must also recognize the value of knowledge about various cultures ( MATO, 2008 , 2016 ).

The importance of discussing this topic in higher education also involves the need to expand the perspectives for the development of competences within this space. Subjects need to support each other’s codes or aspects, which learn to see things differently ( COPPETE; FLEURI; STOLTZ, 2012 ).

Therefore, we present a conceptual reinterpretation about IC and started the process with discussions about the main concepts of competences, interculturality and intercultural competences adopted by the literature. There are many concepts that are discussed about both construct and some parameters reoccur among the various ideas. Firstly, regarding the concept of competences, there seems to be a discourse that converges towards the association of knowledge, skill and attitudes joined as the central concept of competences. Combined with this, this concept transposes the IC concept that appropriates these three items, often without associating them or as a way to distinguish IC from Intercultural Communicative Competences (ICC).

As explained by Huber; Reynolds (2014) , language is a symbolic system that allows group members to share their cultural perspectives, and is an important component of IC, but not the only one. Discussions about interculturality permeate, among others, through aspects that contemplate beliefs, values, identity, customs of a certain set of individuals and their interactions. This presupposes a discussion about culture, which is characterized by a set of artifacts, aspects of a given society, and, without interaction, there is no discussion of interculturality.

Finally, regarding intercultural competences in education, especially in higher education, it is generally understood that Latin American Universities maintain archaic monocultural formats in this world of globalization and still reproduce various forms of hidden racism (cultural, social, economic, environmental, epistemological) ( MATO, 2016 ), which generates an even greater challenge when discussing this trend in the Brazilian context. Therefore, it is necessary to rethink education based on discussions about aspects that emerge from the context.

“Everything seems to contribute in reinforcing homogenization and standardization. We believe that we will only advance in building a quality appropriate to the current times if we question this logic” ( CANDAU, 2016 , p. 807). In view of this, Figure 2 provides a reinterpretation of IC in higher education. We aim to highlight a perspective that incites debates on the topic.

The proposal in Figure 2 is the reinterpretation that we present regarding the conceptual perspective of IC. The individual discussions in the theoretical framework sought to highlight the main concepts of competences and interculturality, thus visualizing the reinterpretation of IC. It was possible to develop an analysis including the main discussion points of the concepts competence, interculturality and intercultural competences.

Based on a premise about competences, which can have a perspective of both input and output and are so visible that they are the main theoretical discussions today, it is understood that this perspective can be associated with those of interculturality from the division between the concepts functional, critical and relational. The scope of these two theoretical choices are shown, based on the discussions of this research and more comprehensive literature, mainly applied in Latin America and Brazil.

The framework was built by uniting the competences perspectives (input and output) with each of the concepts of interculturality (relational, functional and critical), forming the set: 1) relational input Intercultural Competences (IC), 2) functional input IC; 3) critical input IC; 4) relational output IC; 5) functional output IC; 6) critical output IC described as follows:

For relational input IC, an individual can extract intercultural aspects to develop their competence, ignoring conflicts and diversifications of the context. The subject acts in order to develop his/her individual competence as a central focus of the development process. In light of input competences, it means developing individual aspects (CHA) with the objective of focusing on the characteristics of the subject, along with the perspective of interculturality limited to contact and relationship, often at the individual level which, for Walsh (2009) , will hide or ignore the structures of society that aim to position the cultural difference.

The functional input IC is also based on the characteristics of the individual to extract intercultural aspects to develop their competence in an attempt to maintain the cohesion of space and reduce conflicts. The subject acts with the intention, assuming such aspects in order to develop and avoid problematizing the context, without transcending. The perspective of competences as an input is the same as the previous concept, but interculturality is functional, in which the diversity and cultural differences of the space are recognized, seeking to control conflict. Walsh (2009) points out that it is a kind of perspective in which one has a false notion of equity and equality, becoming a new strategy of domination.

Critical input IC is about the individual aspects (e.g., knowledge, skills and attitudes), as in the two previous concepts, but is a way for the individual to analyze and problematize the context in which they are inserted, analyzing intercultural aspects to develop their competence in an attempt to add something to the environment. The subject does or does not act with the intention, assuming the aspects mentioned to develop and problematize the context, transcending cultural differences.

Thus far, the three types of IC have been explained in terms of input. For these, the perspective of competences is established from the set of characteristics that lead an individual to a result (focus on individual aspects). What distinguishes the three types is the dialogue with each perspective of interculturality concept from Walsh (2009) in conjunction with the concept of competences.

The three other perspectives focused on output skills all refer to the concept of competences based on the results. Parry (1996) highlights that competence is analyzed from the moment the individual manages to assimilate and overcome the results of his actions, without emphasizing the set of individual aspects. In all three views, the perspectives of interculturality change, herein based on Walsh (2009) .

For relational output IC, the results of the subjects’ actions are analyzed to understand the effectiveness of the results. In this process, intercultural aspects are part of the environment and the focus is the result of individual action. The characteristics of the individual feed the actions, but the results are the focus and the tendency in this process is that the results are uniform, more cohesive and ignore the differences from the perspective of interculturality.

As for functional output IC, the results of the subjects’ actions are analyzed to understand the effectiveness in the environment, incorporating the cultural diversities of the environment. Differences are recognized, but the stability of the context is sought out. In this process, intercultural aspects are present and there are differences that must be minimized. The tendency in this process is that the results of the actions search for uniformity, recognizing that there are differences, but that they do not seek to transcend.

From the perspective of critical output IC, the results of the subjects’ actions are considered to understand the effectiveness of the results, analyzing and problematizing the diversifications of the environment. In this process, intercultural aspects are present and cannot be ignored. The tendency in this process is that the various actions, with acceptance of different perspectives for the same result, transcend the differences, with a rethink according to Walsh (2009 , p. 4) of “reconceptualizing and re-discovering social, epistemic structures that seek logical, practical and culturally diverse forms of thinking, acting and living”.

Working IC necessarily includes a perspective of the subject and their interaction, whether with another subject, with space, artifacts, among others. Exchange or interaction is essential in the field of interculturality. If there is no interaction, it is understood here that it is not interculturality and could be multiculturalism, for example. From this, the framework aimed to include parameters for empirical research to seek the materialization of the conceptual aspects studied.

The nature of the theoretical framework presented corroborates the configuration of global competence provided by the American Council On Intercultural Education (ACIE, 1996) and Deardorff (2006 , 2009 ) with stages in the competence formation process, which are a continuum and must be developed at all stages of education. The individual can perform several degrees of each phase and their progress may not be linear. Although these are not stages as those mentioned in the discussions, the process was constructed on these premises.

It is clear that it was not necessary to create a concept, which, like Freeman et al. (2009) , could have several problems such as: first, that what discussions already exist about the concept cannot be ignored. Several researchers from various areas have been working on several perspectives to develop the concept. Second, because the various perspectives (areas of communication, culture, linguistics, administration, among others) provide the possibility of conceptual appropriation to each subject participating in the project.

Final considerations

During this research, we observed the latent need for discussions and search for reinterpretations and perspectives about intercultural competences in Higher Education, especially concerning the Global South. The general objective of this research was achieved: the proposal of a reinterpretation of IC that focused on two competency perspectives (input and output) and three aspects of interculturality in education (relational, functional and critical).

This reinterpretation starts from the premise that the subject is based on actions aimed at constantly questioning the latent parameters and the path to be followed. The individual will not be constantly developing intercultural competences (relational input, for example) or even all the time (critical output), and so on, being a continuum. A human being, with their complexity combined with different contexts and situations, will develop IC from different variables. Here, we did not intend to define the variables and future research is expected to seek such answers.

According to the literature, the critical perspective should be the most present in the context of education. For this, the search to develop IC (i.e. critical input or critical output) would be the focus of actions within the higher education environment. Walsh (2009 , p. 4) states that this type of interculturality is still being constructed, and it is important to understand it for the “construction and positioning as a political, social, ethical and epistemic project of knowledge”, which demands structural changes, most importantly within structures with power.

The importance of the reinterpretation is also confirmed in the constant need for revision, whether it be of concepts, aspects, or attributes that make up IC. Deardorff (2006 , p. 258) argues that “definitions and evaluation methods need to be continuously reevaluated [...]. It is important that research and practice remain up-to-date with research and thought processes on this concept”.

It would be a pretense to exhaust the discussion with a framework that could demonstrate all the universality and complexity of the theme and was not the objective. Presenting this proposal is an attempt to unite the authors’ perspectives on the various discussions, thus initiating a source of new perspectives and new theoretical models that encompass the theme.

This article also seeks to broaden the discussions about IC and the need to develop empirical actions to confirm and confront the ideas defended here from bibliographic research. The main idea is that intercultural skills can be developed through various intercultural experiences, as recommended by Huber and Reynolds (2014) .

The conceptual framework presented considers that intercultural competences are part of an interaction process. Following this view, herein it is treated as output, and sometimes as input. Action and results are parts of this framework and is a cyclical process.

Several questions arose during this research, including: Could we develop IC that meets the purposes of Brazilian Higher Education and how do we effectively learn and teach such skills? What is the real context of Brazilian Higher Education Institutions in the development of these competences? Are education professionals prepared to take on this role? What are the best tools to develop such skills? What is the importance of intercultural skills for the graduates of higher education? How do teachers perceive such skills and contexts to develop the topic? Along with these questions, this research tried to provide a framework for answers to be the target of future research.

The incessant search for these answers are topics of today’s debates about concepts and are more relevant everyday as we witness the institutional heterogeneity and teaching-learning processes of formal education.

REFERENCES

ACIE. American Council on Intercultural Education. Educating for the global community: a framework for community colleges. Des Plaines: ACIE, 1996. [ Links ]

ALVAREZ, María Asunción Aneas. Competencia intercultural, concepto, efectos e implicaciones en el ejercicio de la ciudadanía. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación OEI, Madrid, n. 35, v. 5, p. 1-10, 2005. [ Links ]

BACKES, José Licínio. Os conceitos de multiculturalismo/interculturalidade e gênero e a ressignificação do currículo da educação básica. Quaestio, Sorocaba, v. 15, n. 1, p. 50-64, 2013. [ Links ]

BANKS, James Albert. An introduction to multicultural education. Boston: Ally & Bacon, 1999. [ Links ]

BERARDO, Kate; DEARDORFF, Darla (Org.). Building cultural competence: innovative activities and models. Virginia: Stylus, 2012. [ Links ]

BOAS, Franz. The mind of primitive man. New York: Bibliolife. 1922. [ Links ]

BRANDÃO, Hugo Pena; GUIMARÃES, Tomás De Aquino. Gestão de competências e gestão de desempenho: tecnologias distintas ou instrumentos de um mesmo construto? Revista de Administração de Empresas, São Paulo, v. 41, n. 1, p.8-15, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASLAVSKY, Cecilia. Bases, orientaciones y criterios para el diseño de programas de formación de profesores. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, Madrid, n. 19, p. 13-50, 1999. [ Links ]

BYRAM, Michael. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1997. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão. Diferenças culturais, interculturalidade e educação em direitos humanos. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 33, n. 118, p. 235-250, jan./mar. 2012. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão (Org). Interculturalizar, descolonizar, democratizar: uma educação “outra”? Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras, 2016. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão. Pluralismo cultural, cotidiano escolar e formação de professores. In: CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão (Org.). Magistério: construção cotidiana. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1997. p. 237-250. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão; KOFF, Adélia Maria Nehme Simão. Conversas com... sobre a didática e a perspectiva multi/intercultural. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 27, n. 95, p. 471-493, maio/ago. 2006. [ Links ]

CLIFFORD, James; MARCUS, George Emanuel. Writing culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986. [ Links ]

CRES. Conferência Regional de Educação Superior, 3., 2018, Córdoba. Declaração da.... Córdoba: CRES, 2018. Disponível em: < http://www.cres2018.org> . Acesso em: 12 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

COPPETE, Maria Conceição; FLEURI, Reinaldo Matias; STOLTZ, Tânia. Educação para a diversidade numa perspectiva intercultural. Revista Pedagógica Unochapecó, Chapecó, ano 15, v. 01, n. 28, p. 341-345, jan./jun, 2012. [ Links ]

CRICHTON, Jonathan; SCARINO, Angela. How are we to understand the intercultural dimension? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, Sidney, v. 30, n. 1, p. 04.1-04.21, 2007. [ Links ]

DEARDORFF, Darla K. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in Intercultural Education, Thousand Oaks, n. 10, p. 241-266, 2006. [ Links ]

DEARDORFF, Darla K. The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization at institutions of higher education in the United States. 2004. 337 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – North Carolina State University, Releigh, 2004. [ Links ]

DEARDORFF, Darla K. (Ed). The Sage handbook of intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009. [ Links ]

DELORS, Jacques. Educação: um tesouro a descobrir. São Paulo: Cortez; 1996. Relatório para a Unesco da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o século XXI. [ Links ]

DERVIN, Fred. Assessing intercultural competence in language learning and teaching: a critical review of current eff orts. In: DERVIN; Fred; SUOMELA-SALMI, Eija (Ed.). New approaches to assessing language and (inter)cultural comptences in higher education. Bern: Peter Lang, 2010. p. 157-174. [ Links ]

DOLZ, Joaquim; OLLAGNIER, Edmée. O enigma da competência. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. [ Links ]

DURAND, Thomas. L’alchimie de la compétence. Revue Française de Gestion, Paris, n. 127, p. 84-102, jan./fev. 2000. [ Links ]

DUTRA, Joel Souza. Competências: conceitos e instrumentos para a gestão de pessoas na empresa moderna. São Paulo: Atlas, 2004. [ Links ]

FANTINI, Alvino E. Assessment tools of intercultural communicative competence. Humphrey [s. n.], 2007. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Bruno Henrique Rocha; FLEURY, Maria Tereza Leme. Modelos de gestão por competência: evolução e teste de um Sistema. Análise, Porto Alegre, v. 18, n. 2, p. 103-122, jul./dez. 2007. [ Links ]

FLEURY, Maria Tereza Leme; FLEURY, Afonso Carlos Correa. Construindo o conceito de competência. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, Rio de Janeiro, v. 5, p. 183-196, 2001. [ Links ]

FLEURY, Maria Tereza Leme; FLEURY, Afonso Carlos Correa. Alinhando estratégia e competências. Revista de Administração de Empresas, São Paulo, v. 44, n. 1, p. 44-57, jan/mar, 2004. [ Links ]

FLEURY, Maria Tereza Leme; FLEURY, Afonso Carlos Correa. Estratégias empresariais e formação de competências: um quebra-cabeça caleidoscópico da indústria brasileira. São Paulo: Atlas, 2004a. p. 27-59. [ Links ]

FORQUIN, Jean-Claude. O currículo entre o relativismo e o universalismo. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 21, n. 73, p. 79-83, dez. 2000. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, Mark et al. Embedding the development of intercultural competence in business education. Sydney: Australian Learning and Teaching Council, 2009. Disponível em: < http://www.olt.gov.au/project-embedding-development-intercultural-sydney-2006> . Acesso em: 23 maio 2019. [ Links ]

GATTAI, Maria Cristina Pinto. A fragilidade da classificação das competências e a eficácia do perfil como instrumento de sua gestão. 2008. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia Social e do Trabalho) – Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

GEERTZ, Clifford. The Cerebral Savage: on the work of Claude LéviStrauss. In: GEERTZ, Clifford. The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books, 1973. p. 345-359. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 1999. [ Links ]

GOERGEN, Pedro L. Competências docentes na educação do futuro: anotações sobre a formação de professores. Nuances, Presidente Prudente, v. 6, n. 6, p. 1-9, out. 2000. [ Links ]

GREEN, Paul C. Desenvolvendo competências organizacionais consistentes: como vincular sistemas de recursos humanos a estratégias organizacionais. Tradução de Ana Paula Andrade. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark, 1999. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE, Geert. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1980. [ Links ]

HUBER, Josef; REYNOLDS, Christopher (Ed.). Developing intercultural competence through education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2014. (Pestalozzi series; n. 3). [ Links ]

JORDAN, José Antonio. Propuesta de educación intercultural para profesores. Barcelona: CEAC, 1996. [ Links ]

KRAMSCH, Claire. Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. [ Links ]

KRAMSCH, Claire. Language and culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

KREUTZ, Lúcio. Identidade étnica e processo escolar. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 107, p. 79-96, jul. 1999. [ Links ]

LE BOTERF, Guy. Construir as competências individuais e colectivas. Lisboa: ASA, 2005. [ Links ]

LIMA, Telma Cristiane Sasso; MIOTO, Regina Célia Tamaso. Procedimentos metodológicos na construção do conhecimento científico: a pesquisa bibliográfica. Revista Katálysis, Florianópolis, v. 10, n. esp, p. 37-45, 2007. [ Links ]

MATO, Daniel (Coord). Diversidad cultural e interculturalidad en educación superior: experiencias en América Latina. Caracas: Unesco-Iesalc, 2008. [ Links ]

MATO, Daniel. Universidades e diversidade cultural e epistêmica na América Latina: experiências, conflitos e desafios. In: CANDAU, Vera Maria. Interculturalizar, descolonizar e democratizar: uma educação “outra”? Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras, 2016. p. 38-63. [ Links ]

McLAREN, Peter. Multiculturalismo crítico. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez; Instituto Paulo Freire, 2000. [ Links ]

McCLELLAND, David Clarence. Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence”. American Psychologist, Washington, DC, v. 28, n. 1, p. 1-14, Jan. 1973. [ Links ]

MORGADO, Ana Cristina. As múltiplas concepções da cultura. Múltiplos Olhares em Ciência da Informação, Belo Horizonte, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-8, mar. 2014. [ Links ]

MOROSINI, Marília Costa. Qualidade da educação superior e contextos emergentes. Avaliação, Campinas, v. 19, n. 2, p. 385-405, jul. 2014. [ Links ]

MOROSINI, Marília Costa. CABRERA, Alberto F.; FELICETTI, Vera Lucia, Competências do pedagogo: uma perspectiva docente. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 34, n. 2, p. 230-240, maio/ago, 2011. [ Links ]

PARRY, Scott B. The quest for competencies. Training, New York, v. 33, n. 7, p. 48-56, jul. 1996. [ Links ]

PASCARELLA, Ernest T. College environmental influences on learning and cognitive development: a critical review and synthesis. In: SMART, John (Ed.). Higher education: handbook of theory and research. New York: Agathon, 1985. p. 1-64. [ Links ]

PERRENOUD, Philippe. Construir as competências desde a escola. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas Sul, 1999. [ Links ]

PIZZANI, Luciana et al. A arte da pesquisa bibliográfica na busca do conhecimento. Revista Digital de Bibliotecnia e Ciência da Informação, Campinas, v. 10, n. 1, p. 53-66, 2012. [ Links ]

REYNA, Miriam Hernández. Sobre los sentidos de “multiculturalismo” e “interculturalismo”. Ra Ximhai, Sinaloa, v. 3, n. 2, p. 429-442, maio/ago. 2007. [ Links ]

RIOS, Terezinha Azerêdo. Compreender e ensinar: por uma docência de melhor qualidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001. [ Links ]

ROJAS, Axel. ¿Etnoeducación o educación intercultural? Estudio de caso sobre la licenciatura en etnoeducación de la Universidad del Cauca. In: MATO, Daniel (Coord.). Diversidad cultural e interculturalidad en educación superior: experiencias en América Latina. Caracas: Unesco-Iesalc, 2008. p. 233-242. [ Links ]

SÁ, Patrícia; PAIXÃO, Fátima. Contributos para a clarificação do conceito de competência numa perspectiva integrada e sistémica. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, Braga, v. 1, n. 26, p. 87-114, 2013. [ Links ]

SCHNABEL, Deborah et al. Konstruktion und validierung eines multimethodalen berufsbezogenen tests zur messung interkultureller kompetenz = Development and validation of a job-related multimethod test to measure intercultural competence. Diagnostica, Göttingen, v. 61, n. 1, p. 3-21, 2015. [ Links ]

SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura de; NUNES, João Arriscado. Introdução: para ampliar o cânone do reconhecimento, da diferença e da igualdade. In: SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura de (Org.). Reconhecer para libertar: os caminhos do cosmopolitismo multicultural. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2003. p. 13-59. [ Links ]

SPENCER, Lyle Manly; SPENCER, Signe. Competency at work: models for superior performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993. [ Links ]

SPITZBERG, Brian H.; CHANGNON, Gabrielle. Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In: DEARDORFF, Darla K. (Ed.). The Sage handbook of intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009. p. 2-52. [ Links ]

SUGUMAR, V. Raji. Competency mapping of teachers in tertiary education. Chennai: Anna University, 2009. Disponível em: < http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/custom/portlets/recordDetails/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED506207&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED506207> . Acesso em: 15 jan. 2010. [ Links ]

TYLOR, Edward Burnett. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. London: John Murray; Albermale Street, 1871. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura. Declaração universal da Unesco sobre a diversidade cultural. Brasília, DF: Unesco, 2002. Disponível em: < http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001271/127160por.pdf> . Acesso em: 19 ago 2018. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura. Investir na diversidade cultural e no diálogo intercultural: direito humano à educação. Brasília, DF: Unesco, 2009. Disponível em: < http://www.dhescbrasil.org.br/index.php> . Acesso em: 20 ago 2018. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidad crítica y educación intercultural. In: SEMINÁRIO INTERCULTURALIDAD Y EDUCACIÓN INTERCULTURAL, 2009, La Paz. Seminário… La Paz: Instituto Internacional de Integración del Convenio Andrés Bello, 2009. Disponível em: < http://docplayer.es/13551165-Interculturalidad-critica-y-educacion-intercultural.html> . Acesso em: 20 ago 2018. Este artículo es una ampliación de la ponencia presentada en el Seminario “Interculturalidad y Educación Intercultural”, organizado por el Instituto Internacional de Integración del Convenio Andrés Bello, La Paz, 9-11 de marzo de 2009. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidad, estado, sociedad: luchas (de)coloniales de nuestra época. Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolivar; AbyaYala, 2009a. Disponível em < http://www.derecho.uach.cl/documentos/Interculturalidad-estado-ysociedad_Walsh.pdf> . Acesso em: 20 ago 2018. [ Links ]

WHITE, Leslie Alvin. The concept of culture. American Anthropologist, Virgínia, n. 6l, p. 227-251, 1959. [ Links ]

ZARIFIAN, Philippe. Objetivo competência: por uma nova lógica. São Paulo: Atlas, 2001. [ Links ]

Received: November 07, 2018; Revised: May 21, 2019; Accepted: June 04, 2019

texto em

texto em