Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 28-Abr-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046217318

SECTION: ARTICLES

The development of basic education in Amapá from 1991 to 2003: from rhetoric to action*

1- Universidade Federal do Amapá, Macapá, AP, Brasil. Contatos: sa-antonia@hotmail.com; zfcofer@gmail.com.

This article presents an analysis of the development of basic education in Amapá since its real inception as a state of the Federation – in 1991, when the first state governor-elect took office – until 2003, the last year foreseen for the Decennial Education Plan of the State. With almost a quarter of the population illiterate and a context of continuous population growth, one of the great demands at the beginning of the decade was for better indices in basic education. In this regard, it analyses the elaboration and implementation of the main proposals of the state public power for the development of basic education in the state, and measures the advances of these proposals. The research is quantitative and, methodologically, interacts with historical and statistical methods in order to rebuild a process and obtain historical generalizations, going directly to the primary sources, complementing with the statistical analysis of five educational indicators. The outcomes indicate that in Amapá, as in Brazil, in the 1990s, the official speech on eradicating illiteracy and providing good quality public education with democratic management was common. However, the progress achieved was insufficient and did not necessarily mean qualitative outcomes, given the high rates of school failure and dropout. The public power of Amapá planned and determined the direction of public basic education, however, the results do not derive from a democratically participatory process, nor did they significantly alter the status quo of the social structure of Amapá.

Key words: Education policies; Basic education; Development; Decennial education plan; Amapá

Este artigo apresenta uma análise do desenvolvimento da educação básica no Amapá, desde a sua estadualização de fato – em 1991, quando tomou posse o primeiro governador eleito – até 2003, último ano previsto para a vigência do Plano Decenal de Educação do Estado. Com quase um quarto da população de analfabetos e um quadro de contínuo aumento populacional, uma das grandes demandas, no início da década, era a de melhores índices na educação básica. Neste encalço, são analisadas a elaboração e a implementação das principais propostas do poder público estadual para o desenvolvimento da educação básica no estado e mensurados os avanços destas propostas. A pesquisa é quali-quantitativa e, metodologicamente, interagem os métodos histórico e estatístico, mediante os quais se buscou reconstruir um processo para obter generalizações históricas, indo diretamente às fontes primárias, complementando com a análise estatística de cinco indicadores educacionais. Os resultados assinalam que no Amapá, assim como no Brasil, era comum, na década de ١٩٩٠, o discurso oficial sobre a erradicação do analfabetismo e a oferta de educação pública de qualidade com gestão democrática. Contudo, os avanços alcançados foram insuficientes e não significaram, necessariamente, resultados qualitativos, dados os altos índices de reprovação e evasão escolar. O poder público do Amapá planejou e determinou os rumos da educação básica pública, no entanto, os resultados não são decorrentes de processos democraticamente participativos, tampouco alteraram, significativamente, o status quo da estrutura social do Amapá.

Palavras-Chave: Políticas de educação; Educação básica; Desenvolvimento; Plano Decenal de Educação; Amapá

Introduction

The return to democracy and the elaboration of the Federal Constitution of 1988 (BRASIL, 2012) promoted a great political effervescence in Brazil in the 1980s, a fertile period in Brazilian history concerning the organization of education (GHIRALDELLI JÚNIOR, 1990; SAVIANI, 2007). In this period of restoring democracy, Brazil presented alarming rates of over 30% of illiterate adults and a large contingent of children and young people with no access to basic schooling.

Although the political circumstances have led to renewed expectations of significant advances in education, for Hermida Aveiro (2002), it is common in Brazilian history, in periods of economic and political crisis, to carry out constitutional reforms that imply new laws for education, given that they are inseparable. The reformulation of public policies and even a new constitution seem to be the common consequence of the crises of the superstructure, without, however, changing the status quo of the total social structure.

Among the plans and new regulations of national education in the 1990s, the main ones are: the Decennial Plan of Education for All (PDET2), from 1993 (BRASIL; MEC, 1993); the Education Law (LDB3), from 1996 (BRASIL, 2010); the Fund for Development and Maintenance of Elementary Education and Recognition of the Teaching (FUNDEF4), from 1997 (BRASIL; MEC, 2004) and the National Education Plan (PNE5), drawn up in the decade and approved in January 2001. In the ideological dispute between mobilized educators and the public power, to define the directions of national education, prevailed the proposals of the public power (BOLLMANN, 2010; SAVIANI, 2007).

Taking the political environment of the 1990s as an indication of advances possibility in public education policies at national and state level, this article aimed to analyze the development of basic education in the state of Amapá in that decade. The analysis focused on the actions of the government regarding public basic education, and on the quantitative educational results achieved in the decade, both in the public and in private sphere, thus demonstrating the quantitative development of education in both domains.

As a starting question, we sought to know, beyond the government rhetoric, what in fact progressed in basic education, what remained and possible new configurations of education in the state of Amapá. Methodologically, historical and statistical methods were used to rebuild a process and obtain historical generalizations, going directly to the primary documents, which are concerned to the planning and implementation of education policies, ending with the analysis of statistical synopses of basic education, from 1991 to 2003, released by the Ministry of Education (MEC6).

Selected internal documents of the state government that cover the 1990s and another three years of the following decade are considered as first-hand documents because, according to Gil (1989, p. 51), those documents “[…] have not received any analytical treatment’ [...]”. They report the description of the ideas or rhetoric which guided public education and, in theory, directed the education in Amapá: the Decennial Plan of Education for the State of Amapá (PDEEA7), elaborated during the state government of Anníbal Barcellos (1991-1994), with a validity forecast from 1994 to 2003, and the Sustainable Development Plan of Amapá (PDSA8), specifically the Curricular Guidelines for the state of Amapá, elaborated in the state government of João Alberto Capiberibe (1995-2002).

The outcomes of education between 1991 and 2003 were analyzed according to Coelho (2016, p. 80), whereby performance indicators of a public policy should be sought in the theoretical and normative literature. According to him, an evaluation of a public policy presents a judgment of performance, that is, a judgment about the adequacy of what was described taking into account parameters or criteria determined by indicators, without seeking to understand or describe relations and mechanisms, nor characterize processes.

The state education plans were used to support the descriptive analysis of what was planned in basic education in Amapá, while the analysis of what was done follows the parameters of Quality Indicators in Education established by Unicef (United Nations Children’s Fund), United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP9) (INEP; MEC, 2004). The Indicators are: number of schools (public and private); number of education professionals10(and their education); school enrollment; literacy rates, illiteracy and completion of basic education; access to special education and youth and adult education program (EJA11). To verify the educational attainment, basic education is analyzed trough results – passing, failure and dropout.

Statistical analysis allowed the evaluation of education policies in the state, in terms of achieving the desired results (COELHO, 2016). In order to demonstrate the results concerning the total quantum of the population under analysis, it was used the 1991 and 2000 demographic censuses from Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE12) and all the school censuses from 1993 to 2003, from INEP. The data analysis allows us to measure the progress or setbacks of basic education and to establish comparisons between the indices of public and private education.

This article begins by presenting education planning in Brazil, followed by the presentation of education planning in the state of Amapá, specifically the Decennial Education Plan, drawn up at the end of 1993, and the Amapá Sustainable Development Plan, government policy that started in 1995, and its curricular guidelines for the state of Amapá. In a subsequent topic, the results of basic education in the state of Amapá, between 1991 and 2003, are presented in Excel graphs and tables, considering literacy/illiteracy, the dynamics of public and private schools, professionals working in education, school enrollments and results from basic education. It ends up with final considerations and the documentary and bibliographic references consulted.

National education planning

In the early 1990s, the Ministry of Education declared that low National education indexes were interdependent on the living conditions of much of the Brazilian population, such as the large contingent of poor children and adolescents in rural areas and the problem resulting from migration dynamics of the poor to the urban centers (BRASIL; MEC, 1993).

Added to these factors are economic challenges of a long period of instability and recession that have produced and potentiated high levels of social and regional inequality, with over 39 million people living below poverty line and with minimal levels of social rights, such as access to health services and education, making it impossible to exercise complete citizenship. This proposition of MEC indicates that the main problem of national education was structural, that is, the precariousness of education was the result of the precarious social, economic and political conditions of the country (BRASIL; MEC, 1993).

In the decade of 1990, some plans and new regulations to develop national education stand out: the Decennial Plan of Education for All (PDET), from 1993 (BRASIL; MEC, 1993); the Education Law (LDB), from 1996; Fund for Development and Maintenance of Elementary Education and Recognition of the Teaching (Fundef), established by Law No. 9,424 of December 24, 1996, beginning in 1997; and the National Education Plan (PNE), approved by Law no. 10,172, of January 9, 2001. The school and education model in the country was the subject of dispute between educators mobilized at national level and the public power, but for both the LDB/96 and the PNE/2001, the proposals of the public power prevailed (BOLLMANN, 2010; BRASIL, 2001; SAVIANI, 2007).

The PDET, with a ten-year validity, starting in 1993, aimed at eradicating illiteracy and universalizing elementary school13 in Brazil. In this regard, the federal entities were invited to covenant on the goals of the Plan and to prepare their own 10-year plans, following the national premises consolidated in the National Week of Education for All, held by MEC in Brasilia, from May 10 to 14 of 1993. Like the other entities of the Federation, the state of Amapá was present at the event (BRASIL; MEC, 1993).

The PDET establishes goals, measures and instruments to address obstacles and propose strategies to eradicate illiteracy and universalize basic education. However, it does not refer to possible political strategies to tackle and overcome the socioeconomic challenges of Brazil, although it emphasizes that the development of education is interdependent of the economic and social development of the country. Among others, Furtado (2004) proposes that real development must be followed by changes in the country’s economic, political, social and institutional structures; therefore, he ratifies this interdependence between the model of economic development and the development of education. Nevertheless, it has not been the Brazilian model of development.

One of the plan›s premises to overcome one of the great obstacles of public education – the corporatist and clientelist politics that permeated education both by the public administration and the unions – would be to establish favorable instruments to the continuity and sustainability of educational policies and the management of systems and school units, independent of changes in government (BRASIL; MEC, 1993).

Gadotti (2000), analyzing the results of the Plan, found that the discussion of national education was cyclical, that is, only when big conferences appear, the discussion reappears. This discontinuity may result in loss not only of the work carried out as an outcome of the Plan, but also of the discussion and movement that took place in all Brazilian states and resulted in the respective state decennial plans.

Gadotti (2000) proposed that the State should go beyond rhetoric and the signing of documents, it should be articulated at the federal, state and municipal level to mobilize civil society, especially schools, towards education for all (emphasis added), proposed in the World Declaration on Education for All, the outcome of the World Conference on Education for All, held in 1990, in Jomtien, Thailand. Saviani (2002) also reinforced this statement.

Considering that illiteracy fell from 25%, in 1991, to 15%. in 2000, there have been considerable quantitative advances in national education. However, despite great access to elementary school14, the problem of illiteracy and social and regional inequalities of access and success in basic education was not completely solved. Carneiro (2012) points out the precariousness of the final stage of basic education (High School), calling it “the bottleneck of education in Brazil”, for this level of education continued to present insufficient opportunities for access and success, even after all education regulations in the decade. All plans and laws so far focused only on the universalization of elementary education, leaving out preschool, high school, youth and adult education and special education.

Education planning in Amapá

In 1991, Amapá had a population of 289,397 inhabitants, with more than 80% living in the urban area. The capital, Macapá, and the neighboring city Santana concentrated 80% of the population. In the year 2000, the population of the state was of 477,032 inhabitants, representing the highest geometric average annual growth rate in Brazil (5.77). Only in the population of Macapá and Santana there was an increase of more than 144 thousand new inhabitants in the decade, reaching the end of this decade with only 10% of the population living in the rural zone (BRASIL; IBGE, 1991; 2000).

The accelerated population growth of the new state was boosted by specific events such as the installation of the Industry and Trade of Ores (ICOMI15) in 1953; the implementation of the Jari Project, in 1968; becoming a state of the Federation, in 1988; and the establishment of the Free Trade Area of Macapá and Santana (ALCMS16), in December 1991. The demographic growth and the disorderly urbanization process of the state, mainly of its capital – Macapá – occurred mainly due to the disorderly arrival of immigrants from Pará, Maranhão and Ceará. Because of this model of growth and urbanization, there was a bottleneck in the supply of employment and basic services, such as treated water, sanitation and public transportation, since investments in infrastructure did not grow at the same ratio (ABRANTES, 2014).

At the beginning of the 1990s, Amapá had the lowest inequality index among the states in the North, lower than the indexes of all the major regions and lower than the general index of Brazil. During the decade, however, while Rondônia and Roraima had a reduction in the inequality index, Amapá increased to the fifth highest index among the states of the region, higher than the indexes of the South and Southeast regions, as shown in Table 1, where the Gini Index17 is presented:

Table 1 Gini index of per capita household income of Brazil, regions and federative units of the North region in 1991 and 2000

| País, regiões e unidades federativas | 1991 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 0,6383 | 0,6460 |

| North region | 0,6257 | 0,6545 |

| Acre | 0,6259 | 0,6477 |

| Amapá | 0,5850 | 0,6318 |

| Amazonas | 0,6282 | 0,6823 |

| Pará | 0,6206 | 0,6512 |

| Rondônia | 0,6155 | 0,6110 |

| Roraima | 0,6216 | 0,6202 |

| Tocantins | 0,6331 | 0,6550 |

| Northeast region | 0,6593 | 0,6682 |

| Southeast region | 0,5984 | 0,6093 |

| South region | 0,5857 | 0,5893 |

| Midwest region | 0,6244 | 0,6420 |

Source: Datasus (BRASIL; MS; DATASUS, 1991, 2000).

Analyzing the state’s action for the development of Amapá, Chelala (2008) notes the inability or omission of public power to mitigate the negative direct or indirect impacts resulting from the liberal enterprises in the state. Although the major economic enterprises in the region have occurred with the government endorsement and assistance, the human factor – the local people and the ones which came in search of opportunities – was mostly neglected by the State.

According to Chelala (2008), although in Amapá public policies could have greater power of reaching the population, given the greater magnitude of the local state apparatus, this did not lead to positive results for the local population. According to that author, the State often proved to be hesitant and ineffective in terms of planning and execution of public policies to compensate for the negative impacts of enterprises in the region, as the people’s social rights were not effectively provided.

The Decennial Education Plan for the state of Amapá

The Decennial Education Plan for the State of Amapá (PDEEA) was elaborated at the end of 1993, following the request of MEC and the premises of the PDET, presented to the states and municipalities at the National Education for All Week, held in May 1993, in Brasília. The Secretary of Education of Amapá, present at the event, endorsed the National Commitment to Education for All, which established criteria and commitments to be followed by the federated entities in order to implement the National Decennial Plan at state and municipal level (BRASIL: MEC, 1993; AMAPÁ, 1993).

On November 9, 10 and 11, 1993, the State Education Department of Amapá (SEED18) held the First State Forum on Education in Macapá. The debates were analyzed by the current Secretary of Education and a team consisting of a eight educational technicians central committee, 29 Education Department members, 5 representatives of school units19, operational support staff from the Education Department, participants from educational institutions, trade unions, representatives of neighborhood associations and representatives of the Federal University of Amapá. The result of that work originated the PDEEA, with period of validity from January of 1994 to December of 2003 (AMAPÁ, 1993).

The PDEEA was presented as a reference the Decennial Plan (national). It is a proposal for a literacy policy developed by SEED, a proposal for resizing high school, the statute of the magisterium, the Federal Constitution of 1988, the State Constitution of Amapá and the proposal of Amapá for the new LDB that would be the culmination of the Regional Technical Meeting on the new LDB, held in Belém, PA, in the year 1989 (AMAPÁ, 1993). This variety of meetings and documents concerning education in the state corroborated Ferreira’s (2005) observation that in the 1990s there was, like the national environment demonstrated by Saviani (2002, 2007), an euphoria in the educational environment of Amapá due to political autonomy conferred by the Federal Constitution of 1988.

In explaining the state’s high illiteracy rate, more concentrated in rural areas, the PDEEA indicated that the low income of the majority of the population was the main cause of the educational and social problem in the state. Poverty ended up leading the school-age people early to the labor market as a survival option and, consequently, provoked a grade retention and school dropout high rate, further exacerbating the problem of socioeconomic development of a state that was largely composed of young people (AMAPÁ, 1993).

Education in the state was diagnosed with structural and organizational problems, due to a distancing of the public system from political-social commitments to education. Following the premise that education is one of the processes responsible for the socioeconomic development of a society, the plan was presented as a proposal to reverse the precarious situation of education in the state of Amapá, which implied a “political decision” to operationalize the changes in the education system (AMAPÁ, 1993).

The guiding axis of state education policy would be

[...] the universalization of education, through improvement of the quality of educational action, expansion and maintenance of the physical network (schools), democratic management, based on a work philosophy based on the principles of credibility of its applicants; integration at the various levels of competence, from the social, pedagogical and administrative angle, based on the philosophical political aspects; sociological principle of interdependence – where all segments of society are responsible for the educational process; epistemological principle of the construction of the reality – meaning the reconciliation between what might be done and what can be done [...] principle of legitimacy with the participation of organized civil society in the formulation of educational policies, plans and programs. (AMAPÁ, 1993, p. 21).

The PDEEA proposed seven goals to be achieved in ten years: to expand and improve the physical, technical and organizational infrastructure of education systems; to reduce, by 50%, the rate of dropout and repetition in elementary school, mainly from 1st to 5th grade; ensure full assistance to 30% of low-income children and adolescents; to increase by 50% attendance to High School, with courses focused on the local reality; to train a 100% of the public schools network staff; to increase by 60% the technical and administrative staff of the public school network and improve the education planning system through the use of modern technology.

The Plan did not present the necessary budget (nor its availability) for the operationalization of the proposed goals and actions and, although its prediction of operationalization was for the period from 1994 to 2003, in the 1994 elections Governor Barcellos did not run for reelection, João Alberto Capiberibe was elected and assumed the state government in January 1995. Therefore, as informed by some education technicians at the Education Department in the year of writing the Plan, with the new government, professionals (in theory) committed to the Decennial Plan (which also held positions of political expression in that department) were replaced and the Decennial Plan was proscribed and forgotten.

The Sustainable Development Plan of Amapá

When João Alberto Capiberibe took over the first term as governor of Amapá, in 1995, he presented the Amapá Sustainable Development Plan (PDSA20) as a government plan, inspired by the principles of Agenda 2121. In order to make sustainable development strategies feasible in the state, external technical-scientific teams were brought in to assist in the elaboration and execution of these strategies and, in a second moment, to create a local capacity for knowledge production around the theme of development with environmental protection (AMAPÁ, 1995).

In 1995, Capiberibe’s government initiated activities within SEED to restructure the public education system, according to the PDSA premises, and consolidate its vision through the state education system. An internal document of the Education Department, found in the exploratory phase of this research, entitled “Curriculum Guidelines for Basic School Education in the State of Amapá”, contains information on political and institutional actions in the area of public education during the PDSA period (AMAPÁ, 2002).

The curricular guidelines for the state of Amapá

In 1999, the Education Department established a partnership with the Special Studies Institute of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC22). The consultants from PUC promoted successive meetings with the technicians of that department, and workshops for other groups involved in the project, intending to present a “curricular proposal” for the state schools network of Amapá and to adjust public education to the premises of the PDSA. In 2000, a three-stage process was initiated: the first and second consisted in the mobilization of SEED technicians on theoretical and methodological assumptions which should guide the curricular proposal, and the third included teachers from the state schools network to discuss “the role of school subjects, teaching practice and evaluation” (AMAPÁ, 2002, p. 12).

The work of PUC resulted in four books published and sent to the schools in 2000. They are: 1st to 4th grade teaching: the subjects, the skills; 5th to 8th grade and High School teaching: the subjects, the skills. Volumes 1 and 2; Childhood education: a project under construction. In 2001, the work of PUC ended up when they consolidated the Curriculum Guidelines for Basic School Education in the State of Amapá. They proposed to support the schools to begin “a new phase of education in Amapá, in sustainability and therefore in socio-environmental education, in the valuation of prior knowledge, in the autonomy of the school and in the construction of citizenship by those who participate in it” (AMAPÁ, 2002, p. 13).

To feature the Guidelines problematized the urban-rural issue, regarding the restricted curricular and pedagogical models in force, which did not corroborate the idea of inclusion of different communities. Therefore, one of the goals of PDSA in reordering rural, urban and indigenous schools was to overcome the globalized profile of traditional school and encourage the specific culture peoples to participate in the educational process with the right to maintain their own identity. According to the new proposal, indigenous education should be taught in mother tongue and local knowledge should dialogue with the knowledge of the common national base, in order to produce appropriate contents for a socio-environmental education (AMAPÁ, 2002).

Another focus of the guidelines was the unsatisfactory special education service, as it did not constitute an integrating model of special public to regular educational activities of the schools. Another critical point indicated was the unsatisfactory level of students entering elementary school. The most part of them had no mastery of Portuguese (reading, interpretation and composition of texts) and had low logical-mathematical reasoning.

The guidelines are structured in three axes: how is the public school in Amapá; how it should be; the role of educators (teachers and other education professionals) in the achievement of a socio-environmental education as a principle for the construction of sustainable society projected by the PDSA. They were presented as a formal systematization of the fragmented experience of education professionals, to which were added conceptual elements to systematize the various themes, within legal, technical, administrative and pedagogical aspects.

The guidelines presented normative and innovative proposals and, although this new standard established for the school model seemed paradoxical to the idea of school autonomy, the authors claimed a democratic feature, stating they were the result of a wide debate with the state education network, and were made in consonance with the political identity of the current state government elected by the people (AMAPÁ, 2002).

For Moulin (2000), educational advances along the lines of the PDSA could be discernible in the indigenous literacy program in his own language and in the determination of the French language as the first foreign language in High School, whose purpose would be to facilitate relations between Amapá and French Guiana23. The author pointed out that 96% of children from Amapá were studying in good material and pedagogical conditions, and called on the entire population of Amapá to assume the responsibility of building the “world of tomorrow” in the sustainable model proposed by the PDSA (MOULIN, 2000, p. 113-114).

Leonelli (2000, p. 214), however, in an analysis of teachers engagement in the PDSA education model, stated that they presented a corporatist stance towards the public power, whose result was “a conservative pedagogical attitude toward the curricular structure and a resistance to pedagogical innovations and changes in general”. This author’s critique of teachers’ attitude and the prevalence of administrative contracts24 to provide teachers to more remote regions of the state may indicate that the draft Curriculum Guidelines did not correspond exactly to what was proposed and education in Amapá was not fully a PDSA tool.

Results of basic education in Amapá (1991-2003)

The progress of education in Amapá was measured according to “5 Education Quality Indicators” (BRASIL; INEP; MEC, 2004) and arranged in triennia, except for some data that occurred in the interval of each triennium and that deserved prominence.

Literacy (illiteracy)

In 2000, 17% of the population of 409,312 individuals residing in Amapá, over 5 years of age, were still illiterate, a higher rate than the national one (15.7%). If we consider the age groups 5 to 9 years old, 10 to 14 and 15 to 19, among children from 5 to 9, while Brazil presented a slight reduction in this rate, in Amapá it increased from 49.3% to 54%, which points to the absence of effective solutions for the rapid demographic growth and the greater need to provide kindergarten. The illiteracy rate among adolescents from 10 to 14 years old fell to 5.4%, which is lower than the national rate and that of 15 to 19 year olds was considerably reduced, remaining below the national level. However, in general, there was considerable progress in the decade regarding population literacy, as shown in table 2:

Table 2 Illiteracy rate in Amapá and Brazil (1991-2000)

| Age | Population AP – 1991 | Illiteracy rate in 1991 (%) | Population AP – 2000 | Illiteracy rate in 2000 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | BR | AP | BR | |||

| >5 | 243 855 | 24 | 25 | 409 312 | 17 | 15,7 |

| 5 to 9 | 45 170 | 49,3 | 48 | 61 320 | 54 | 45,9 |

| 7 to 9 | 26 848 | 51,6 | 39,8 | 35 491 | 31,3 | 23,8 |

| 10 to 14 | 40 641 | 16 | 18 | 58 785 | 5,4 | 5,9 |

| 15 to 19 | 33 465 | 10 | 12 | 57 436 | 3,5 | 4 |

Source: Demographic census (BRASIL; IBGE, 1991, 2000).

In 2000, the illiteracy rate in the rural area was still higher than in the urban area (32% of the rural population and 15.5% of the urban population), which suggests that the lack of education remained predominant in rural areas. At the beginning of the decade, the illiteracy rate, if calculated from the age group of 5 to 9 years or from 7 to 9 years, is similar, which means the insufficiency of vacancies for kindergarten and first cycle of elementary school.

In 2000, there was a significant reduction in illiteracy among children aged 7 to 9 years (age group funded by Fundef), but children in early childhood education (5 to 6 years) had an even higher illiteracy rate, with a growth, which corresponds to the fact that the provision of early childhood education (level that did not receive funds from Fundef) was insufficient.

Public and private schools

In 1991, the network of basic education schools had 407 educational establishments; of these, 25 units were private, accounting for 6.7% of enrollments in basic education. In 1994, when Amapá was already a consolidated state of the federation, the network of schools, once federal, became state, therefore, there were two networks of public basic education schools: state and municipal.

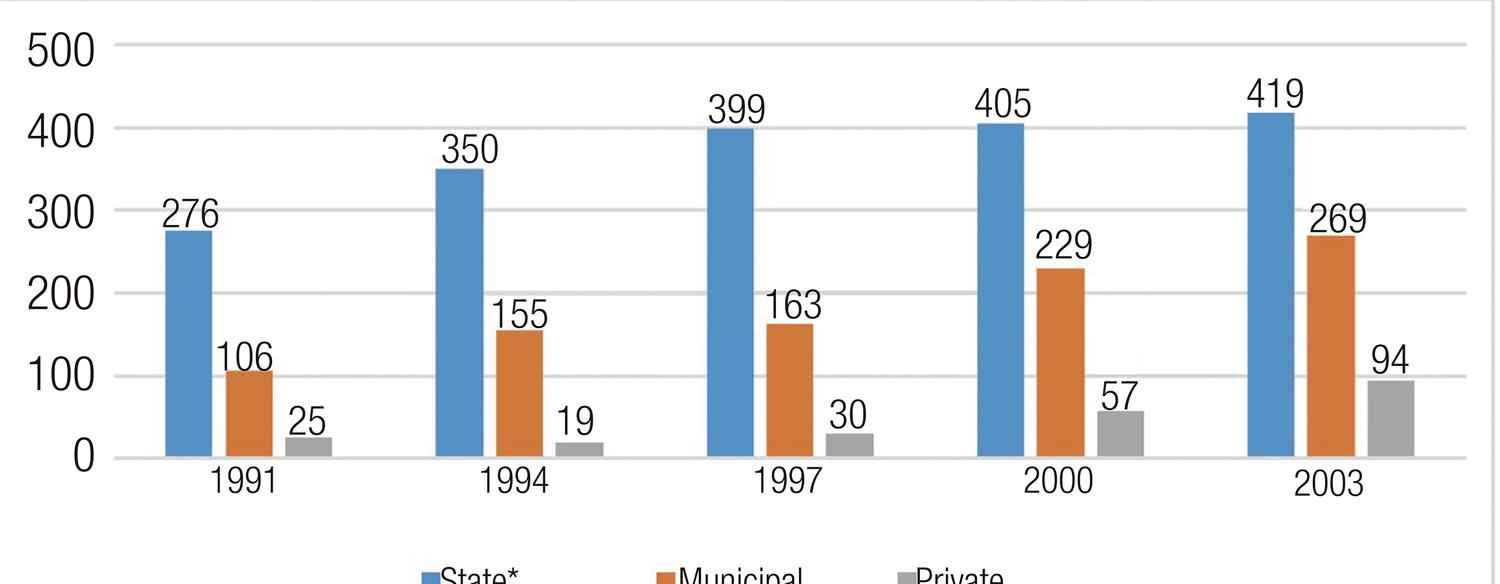

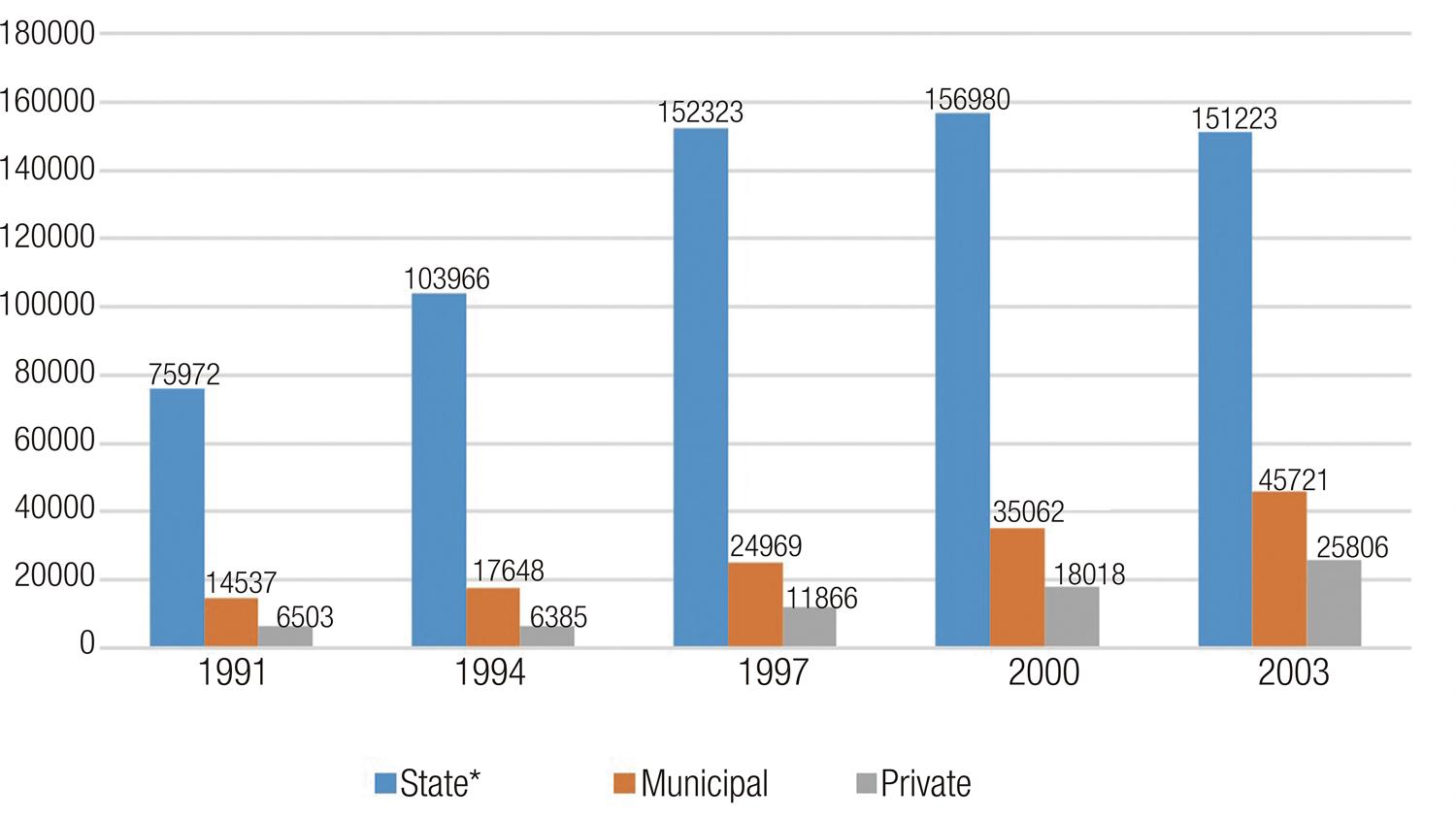

In the analysis of educational advances in the 1990s, there was a relative growth decline of the state education network, although it has been the subject of both education plans. The network that grew the most was the private one (128%), second one was the municipal (116%), and the one that had the least growth was the state network (47%). In the following triennium, the same growth disparities between private, municipal and state networks are accentuated, with, respectively, 276%, 154% and 52%, as shown in Graph 1.

Education professionals

Between 1991 and 1997, the growth of the educational personnel was constant, but between 1998 and 1999, there was a reduction of more than 300 teachers. The reduction occurred in the state administrative body, which comprised a large number of federal civil servants in its teaching staff, reaching 2000 with a negative difference of 225 teachers compared to 1998.

Among the possible factors that led to the reduction of the number of teachers in the state administrative body, we can cite the enactment of Federal Law Nº 9,468 of July 10, 1997, which established the Voluntary Dismissal Program (PDV25) of Federal Executive body workers – because many of these servers were part of the state personnel of Amapá (BRASIL, 1997). The municipalization of elementary school – fomented by Fundef – could also have been a changing factor of the teachers’ distribution between the state and municipal networks in the mentioned period, as well as of the smaller growth of the state schools network.

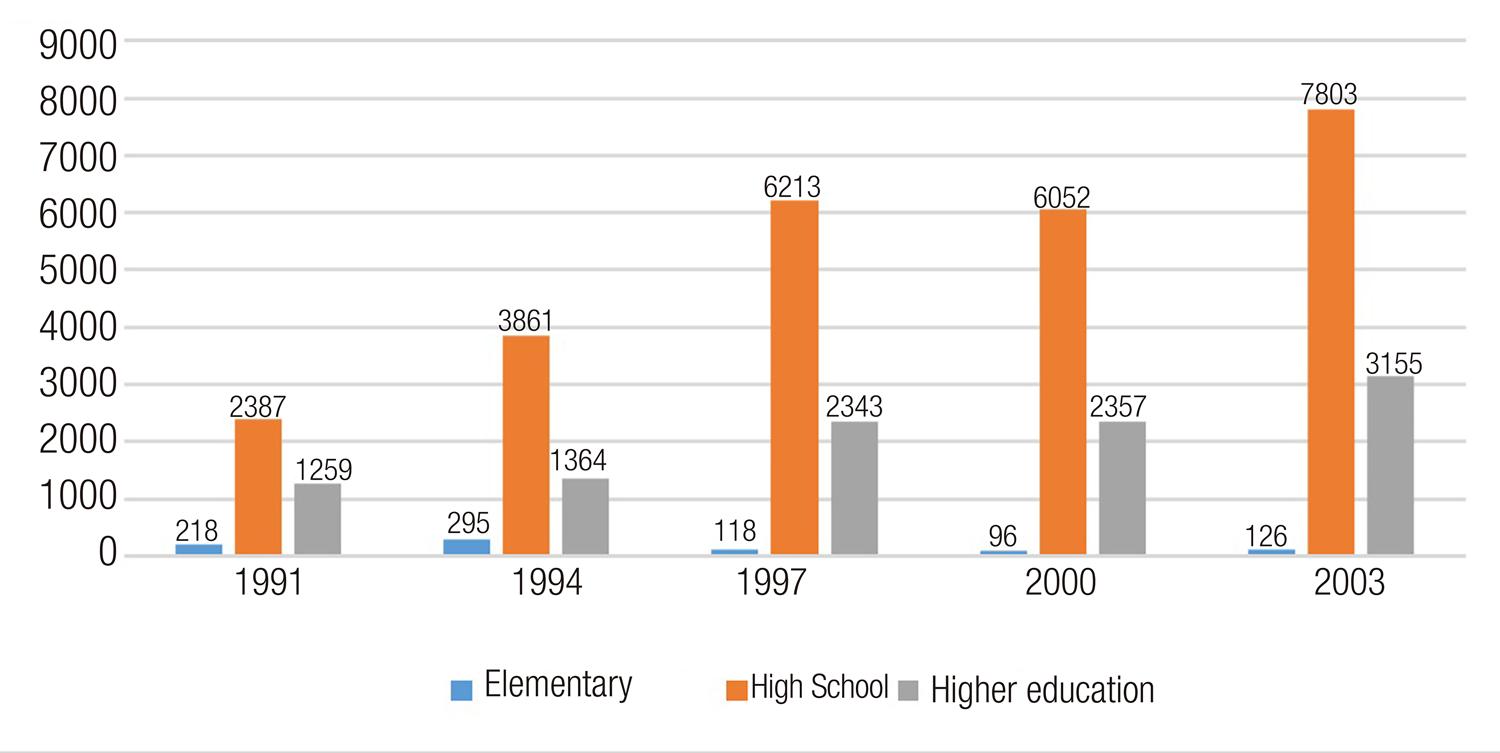

As shown in Graph 2, both the municipal network and the private school network had steadily increased in their teaching staff during the 1990s and maintained a similar growth rhythm in the following three years. The resumption of the growth of the state teachers’ cadre, noticeable since 2000, resulted from the process in which the approved personnel in the public tender of 1999 took office, whose contracting were carried out by the Institute for Research and Development in Public Administration (Ipesap26).

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Graph 2 – Evolution of the basic education teaching staff in Amapá, from 1991 to 2003

Regarding teachers’ education, the rate of teachers with higher education in the early 1990s was 32%, but fell to 28% by the end of the decade. The number of teachers with High School level increased throughout the decade, remaining between 72 and 70% of the total number of professionals. The number of lay teachers (elementary education) fell to 1%. As can be seen in graph 3, the growth trend in teacher education at the secondary level declined between 1998 and 2000, indicating that the proportion of exonerated teachers (voluntary dismissal), since 1998, had secondary education.

School enrolment

During the 1990s, the increase in basic education enrollments was higher than the population growth: the population increased by 65%, while enrollments (public and private network) increased by 116.6%. However, the efforts to cope with the educational demands of the decade were not enough, given the historic illiterate population and the national education system (and by extension state and municipal) not yet consolidated, without a program to attend the demands of early childhood and high school education, as well as attend the contingent of adults who did not have access to education at appropriate age.

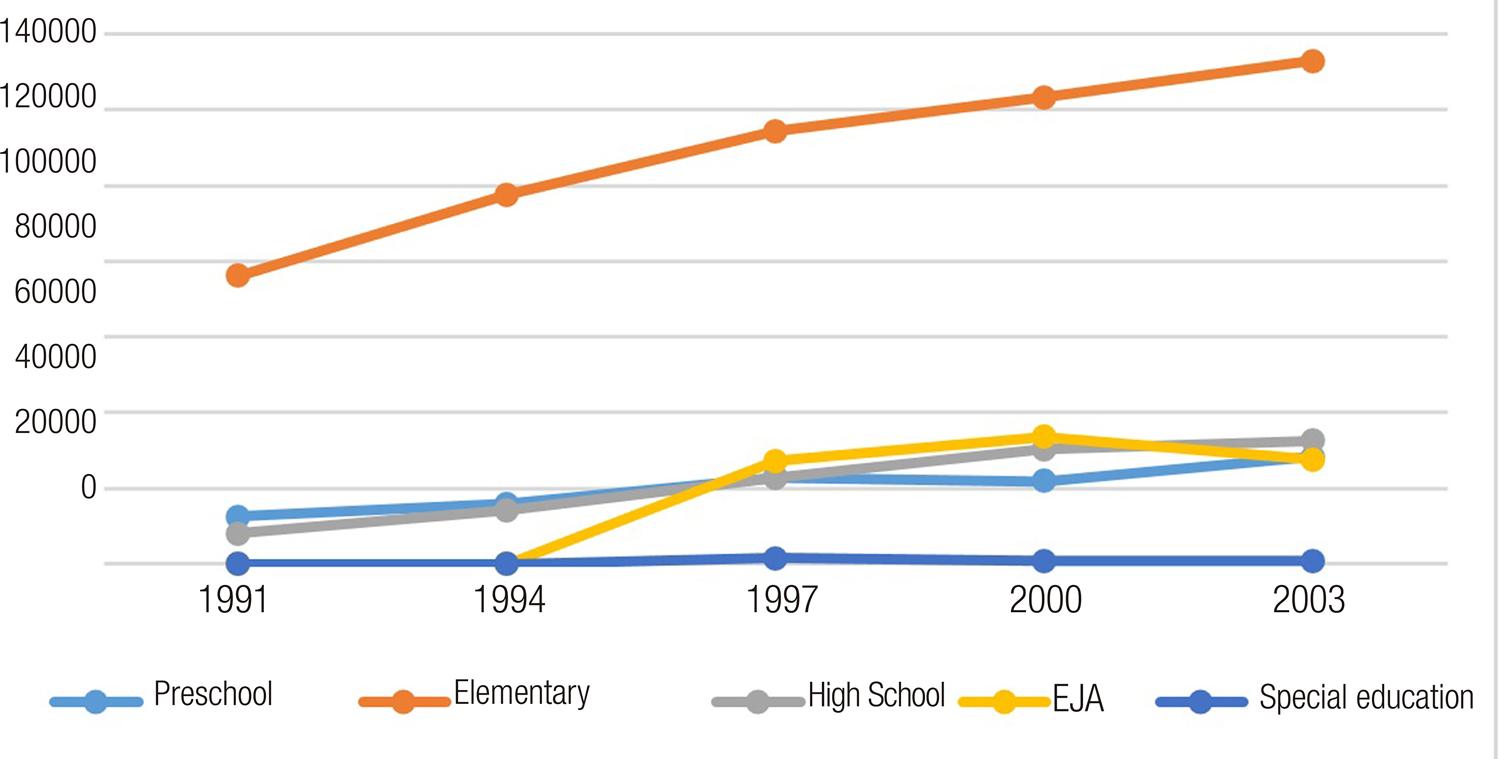

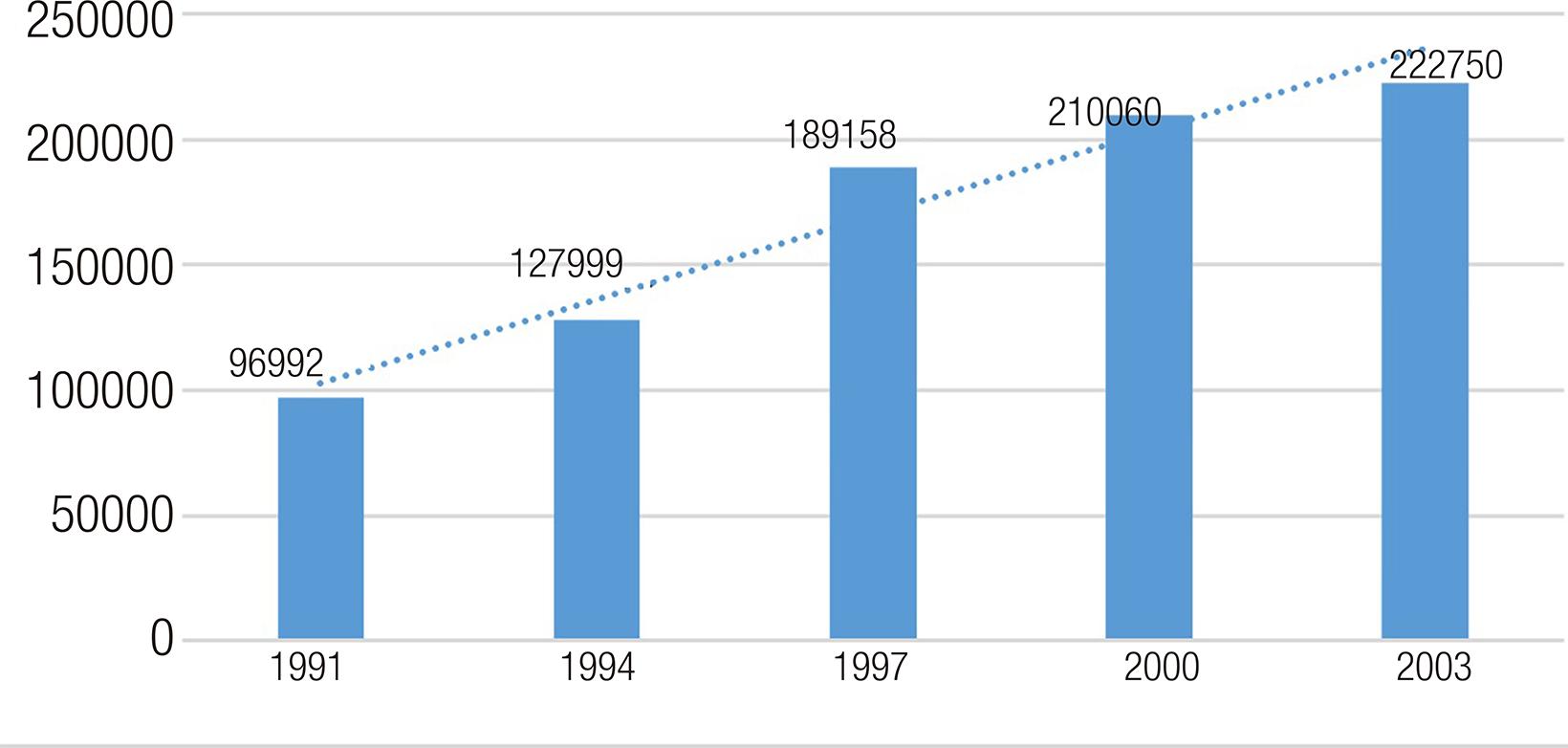

Extending another three years until 2003, the education growth was 130%. As Graph 4 shows, there was a steady increase in the number of enrollments, with the largest amount in the period from 1997 to 2000, and the lowest between 2000 and 2003, which marked a stagnation at the end of the decade. In percentage terms, in the three-year analysis, the highest growth rate (47.8%) occurred in the period from 1994 to 1997 and the lowest (6%) in the period from 2000 to 200327.

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Graph 4 – Growth in access to basic education in Amapá, from 1991 to 2003

The comparison of national and state data shows that Amapá increased access to basic education far above national indices, as shown in Table 3. At both the state and national levels, the highest growth happened between 1994 and 1997, although the period from 1991 to 1994 was significant, followed by the period from 1997 to 2000, when growth happened at a slower rate than the beginning of the decade.

Table 3 Percentage growth of enrollments in basic education - AP / BR, from 1991 to 2003

| Period | Amapá (%) | Brazil (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 to 1994 | 32 | 11 |

| 1994 to 1997 | 48 | 17 |

| 1997 to 2000 | 11 | 8 |

| 2000 to 2003 | 6 | 3 |

| 1991 to 2003 | 130 | 45 |

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

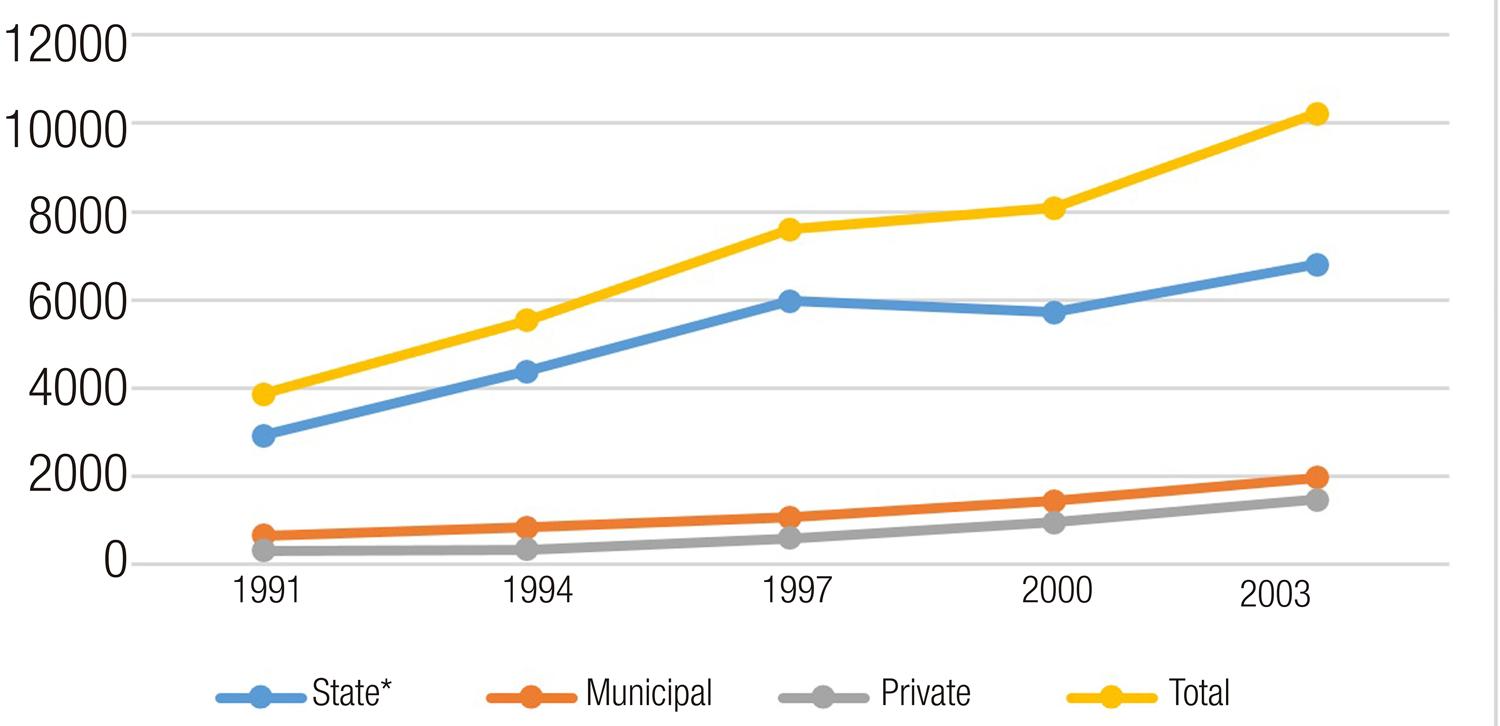

Regarding the number of students per school network, although the state network had the largest number of students, in the 1990s, its growth occurred to a lesser extent than the municipal and private networks, which had the highest growth rate of the decade: 177%. The municipal network increased its enrollment by 141% and the state by 107%.

As indicated in Graph 5, the highest number of enrollments in the state network occurred in the three-year period 1994-1997, when it registered a slowdown in growth: only 3% in the three-year period 1997-2000. In the following triennium, there was a reduction in the number of enrollments, probably due to the progress of private enterprise and the process of municipalization of early childhood and elementary education, since the implementation of Fundef.

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Graph 5 – Evolution of enrollments by network of schools in Amapá, from 1991 to 2003

Private enterprise, while accounting for just over 11% of the student population enrolled in 2003, grew by 297 per cent between 1991 and 2003, while public education grew by 117 per cent over the same period, a reversal of what happened at the national level, in which the relative growth was smaller and inverse in relation to the public and private, as shown in Table 4:

Table 4 – Relative increase of enrollments in public and private education networks in Amapá, from 1991 to 2003

| 1991-2000 (%) | 1991-2003 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Brazil | 47 | 2 | 49,6 | 16,5 |

| Amapá | 112 | 177 | 117 | 297 |

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Elementary education (enrollment) in the early 1990s became the focus of the Decennial Education for All Plan in 1993, and in 1997, it received new mechanisms for universalization through Fundef, which took effect in 1998. Consequently, during the decade, this level of education showed higher growth than the other levels, triggering a bottleneck in education – high school.

In the three-year period 1997-2000, there was an enrollment decline in early childhood education, while high school and EJA continued to grow, EJA with a larger number of enrollments than high school, when enrollment declined in 2003, with a similar numbers to that in 1997. In the three-year period after the 1990s, high school continued to grow, but special education has a number of enrollments above a thousand only in the 1997, as shown in Graph 6:

Basic education results

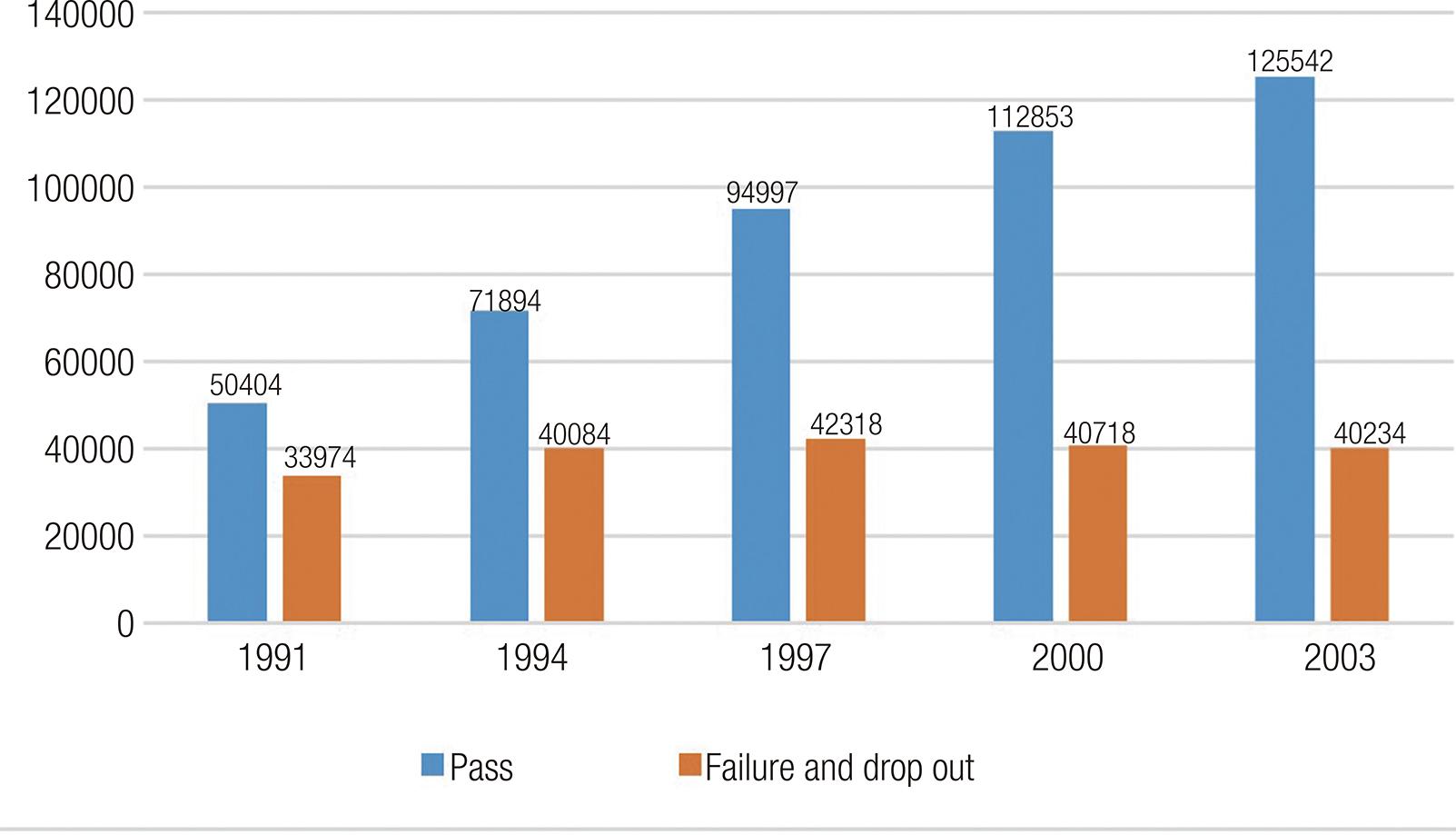

Only 60% of the 96,992 students enrolled in basic education in Amapá, in 1991, were successful (passed), therefore 40% of enrolments resulted in failure and drop out. The pass ratings showed a growing trend in the following triennia, reaching 64% in 1994, 69% in 1997, 73% in 2000 and 76% in 2003, as can be seen in graph 7:

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Graph 7 – School performance in Amapá, from 1991 to 2003

Despite the expressive increase in pass, school success rates in Amapá remained below national rates, as shown in Table 5:

Table 5 – Basic education pass rate - AP / BR, from 1991 to 2003

| Year | Brazil (%) | Amapá (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 64 | 60 |

| 1994 | 67 | 64 |

| 1997 | 77 | 69 |

| 2000 | 77 | 73 |

| 2003 | 78 | 76 |

Source: School census (BRASIL; INEP, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2004).

In the analysis of the study flow of students in Amapá in 11 years – normal duration of basic education in Brazil in the 90’s – it was found that only 31% of the students who entered elementary school, in 1991, completed the 3rd year of High School in 2001, an index similar to the national one. Since special the education and EJA data of the beginning of the decade are not available, its evolution cannot be accurately inferred in the decade under analysis. However, as shown in Graph 6, EJA showed a decreasing trend at the end of the decade, and children’s education presented unimpressive numbers during the analyzed period, with a decreasing trend.

Chart 1 summarizes the results of the indices mentioned above. Its line-by-line reading enables us to observe the performance of the indices in the studied period (1991-2003).

Chart 1 Summary of basic education progress in Amapá (1991-2003)

| Basic Education Progress | 1991 | 2000 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literate Population – 5 years old or above (%) | 76 | 83 | - | |

| Schools | Public network | 382 | 634 | 688 |

| Private network | 25 | 57 | 94 | |

| Education Professionals | 3864 | 8081 | 10224 | |

| Teachers’ education | Elementary | 218 | 96 | 126 |

| High school | 2387 | 6052 | 7803 | |

| Higher education | 1259 | 2357 | 3155 | |

| School enrolments | Public network | 90488 | 192042 | 196944 |

| Private network | 6503 | 18018 | 25806 | |

| Education outcomes (%) | Pass | 60 | 73 | 76 |

| Failure and drop out | 40 | 27 | 24 | |

Source: Demographic census (BRASIL; IBGE, 1991, 2000). School Census (BRASIL; INEP, 2001, 2003, 2004).

Final remarks

The analysis of the proposals and results of education in Amapá in the 1990s and the following three years until 2003 showed that there was a quantitative growth in basic education in the number of schools, education professionals and enrollment. However, the results were unsatisfactory, since the goal of eradicating illiteracy and universal elementary education were not fully achieved. In addition, the precarious situation of children’s education and high school is still outstanding; this is a bottleneck for the next decade and perhaps for an indefinite period.

Considering that education and economic development are interdependent for full development, the presented data from the Gini index – an important indicator of income concentration and, therefore, a measure of inequality – point out to possible impeding factors for full development of education in Amapá: poverty and need for subsistence at the expense of education in the grassroots classes, as warned in the Decennial Education Plan of the State of Amapá.

At the end of this analysis, we can assume that the education plans and policies of the new state showed little operational consistency and project discontinuity, due to, among other factors, political-parties interference in the state. In other words, Amapá followed the cycle of debates and national proposals and the signing of documents, but did not make the necessary efforts for the education for all proposed in the World Declaration of Education for All, since much of what was planned was not operationalized or achieved, pointing to an institutional fragility, pointed out by several authors.

In that sense remarked, to paraphrase Leonelli (2000, p. 214), the proposal of education to “overcome conservative resistance with the beauty of ideas” unfortunately didn’t go far beyond the stage of the beauty of ideas.

REFERENCES

ABRANTES, Joselito Santos. (Des)envolvimento Local em Regiões Periféricas do Capitalismo: limites e perspectivas no caso do estado do Amapá (1966 a 2006). Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2014. [ Links ]

AMAPÁ. Governo do Estado do Amapá. Amapá programa de desenvolvimento sustentável. Macapá: GEA, 1995. [ Links ]

AMAPÁ. Governo do Estado do Amapá. Bases do desenvolvimento sustentável: coletânea de textos. Macapá: GEA, 1999. [ Links ]

AMAPÁ. Secretaria de Estado da Educação. Diretrizes curriculares da educação escolar básica do estado do Amapá. Macapá: Mimeo, 2002. [ Links ]

AMAPÁ. Secretaria de Estado da Educação. Plano decenal de educação do estado do Amapá. Macapá: Mimeo, 1993. [ Links ]

BOLLMANN, Maria da Graça Nóbrega. Revendo o plano nacional de educação: proposta da sociedade brasileira. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 31, n. 112, p. 657-676, jul./set. 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei de Diretrizes e Base da Educação Nacional. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. LEI Nº 9.468, de 10 de julho de 1997. Institui o Programa de Desligamento Voluntário de servidores civis do Poder Executivo Federal e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF, 1997. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9468.htm >. Acesso em: 20 de jan. de 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N° 10.172, de 9 de janeiro de 2001. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo demográfico 1991: características gerais da população e instrução: resultados da amostra. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 1991. [ Links ]

BRASIL. IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo demográfico 2000: características gerais da população e instrução: resultados da amostra. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2000.BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 1997. Brasília, DF: Inep, 1998. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 1998. Brasília, DF: Inep, 1999. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 1999. Brasília, DF: Inep, 2000. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 2000. Brasília, DF: Inep, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 1991-1995. Brasília, DF: Inep, 2003. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Sinopse estatística da educação básica: censo escolar 2003. Brasília, DF: Inep, 2004. [ Links ]

BRASIL. INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. MEC. Ministério da Educação. Indicadores da qualidade na educação. São Paulo: Ação Educativa, 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.portal.mec.gov.br >. Acesso em: 3 maio 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MEC. Ministério da Educação. Fundef: manual de orientação. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2004. Disponível em: <http://mecsrv04.mec.gov.br/sef/fundef/pdf/manual2.pdf >. Acesso em: 12 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MEC. Ministério da Educação. Plano Decenal de Educação para Todos. Brasília, DF: MEC, 1993. Versão acrescida. 136 p. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MMA. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Agenda 21 Global. Brasília, DF: MMA, 1992. Disponível em: <http://www.mma.gov.br/responsabilidade-socioambiental/agenda-21/agenda-21-global >. Acesso em: 02 maio 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MS. Ministério da Saúde. Datasus. Índice de Gini da renda domiciliar per capita segundo região, UF e região metropolitana/período: 1991-2000. In: BRASIL. Datasus. Índice de Gini da renda domiciliar per capita – Brasil. Brasília, DF: MS, 1991. Disponível em: <http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/ibge/censo/cnv/giniuf.def >. Acesso em: 21 abr. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MS. Ministério da Saúde. Datasus. Índice de Gini da renda domiciliar per capita segundo região, UF e região metropolitana/período: 1991-2000. In: BRASIL. Datasus. Índice de Gini da renda domiciliar per capita – Brasil. Brasília, DF: MS, 2000. Disponível em: <http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/ibge/censo/cnv/giniuf.def >. Acesso em: 21 abr. 2018. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, Moaci Alves. O nó do ensino médio. 3. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

CHELALA, Charles. A magnitude do estado na socioeconomia amapaense. 2008. 178 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Desenvolvimento Regional) – Universidade Federal do Amapá: Macapá, 2008. [ Links ]

COELHO, Vera Schattan Ruas Pereira. Abordagens qualitativas e quantitativas na avaliação de políticas públicas. In: CEBRAP. Métodos de pesquisa em ciências sociais: bloco quantitativo. São Paulo: Sesc: Cebrap, 2016. p.179-99. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Norma Iracema de Barros. Política e educação no Amapá: de território a Estado. 2005. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, 2005. [ Links ]

FURTADO, Celso. Os desafios da nova geração. Revista de Economia Política, São Paulo, v. 24, n. 4 (96), p. 483-48, out./dez. 2004. [ Links ]

GADOTTI, Moacir. Da palavra à ação. In: BRASIL. MEC. Ministério da Educação. Educação para Todos: avaliação da década. Brasília, DF: MEC/INEP, 2000. p. 27-32. [ Links ]

GHIRALDELLI JÚNIOR, Paulo. História da educação. São Paulo: Cortez, 1990. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. São Paulo: Atlas, 1989. [ Links ]

HERMIDA AVEIRO, Jorge Fernando. A reforma educacional no Brasil (1988-2001): processos legislativos, projetos em conflito e sujeitos históricos. 2002. 355 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2002. Disponível em: <http://www.repositorio.unicamp.br/handle/REPOSIP/251752>. Acesso em: 2 jan. 2018. [ Links ]

LEONELLI, Domingos. Uma sustentável revolução na floresta. São Paulo: Viramundo, 2000. [ Links ]

MOULIN, Nilson (Org.). Amapá: um norte para o Brasil. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. História das ideias pedagógicas no Brasil. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2007. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. Política e educação no Brasil: o papel do Congresso Nacional na legislação do ensino. 5. ed. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2002. [ Links ]

WOLFFENBÜTTEL, Andréa. Indicadores. Desafios do Desenvolvimento, Brasília, DF, v. 1. n. 4, p. 80-82, 1 nov. 2004. [ Links ]

4- FUNDEF – Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento do Ensino Fundamental e de Valorização do Magistério.

10- The terms “education professionals” mean teachers, educators and other professionals that work in education but not teaching.

13- The translation uses the term “elementary education” or “elementary school” to designate the 8 years of education that start just after early childhood education (kindergarten) and precede high school, according to the structure of the regular educational system in Brazil that divides basic education into: educação infantil (early childhood education), ensino fundamental (elementary school) and ensino médio (high school).

14- Although the Jomtien Conference discussed the universalization of basic education (from early childhood education to high school) in the countries that signed the World Declaration on Education for All, the Ten-Year Plan restricted its focus to the universalization of elementary school (BRASIL; MEC, 1993).

17- “The Gini Index [...] is an instrument to measure the degree of concentration of income in a given group. It points out the difference between the income of the poorest and the richest” varying between zero (equality situation) and one (income concentration) (WOLFFENBÜTTEL, 2004, p. 80).

19- Escola Estadual Augusto Antunes, Escola Estadual José de Anchieta, Escola Estadual. Irineu da Gama Paes, Escola Comercial Gabriel de Almeida Café and Colégio Amapaense (AMAPÁ, 1993).

21- Agenda 21 is a forty-chapter document that resulted from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held in Rio de Janeiro, in 1992, being considered as “[...] a planning instrument for the construction of sustainable societies, in different geographical bases, that reconciles methods of environmental protection, social justice and economic efficiency. ” (BRASIL; MMA, 1992).

23- In 1996, the governments of Brazil and France signed the Agreement of French-Brazil Cooperation that made possible the expansion of the teaching of the French language in Amapá. In 2003, it was inaugurated the State Center of French Language and Culture Danielle Mitterrand, in the city of Macapá.

24- Administrative contracts is a model of employment whose employees are not public servants in its full rights.

27- The growth rate of the 1994-1997 triennium would be reduced to 35% if enrollment in the supplementary and special education were included in the 1994 census. Special education and EJA (former supplementary) only appear in the 1997 school census. In 1996, there were 12,089 supplementary education enrollments.

Received: December 04, 2018; Revised: April 15, 2019; Accepted: June 05, 2019

texto em

texto em