Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 06-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046220336

SECTION: ARTICLES

2- Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, SP, Brasil. Contact: claudiaprioste@gmail.com

Academic failure in Brazil is chronic and complex, therefore it is significant to listen carefully to those who deal with everyday challenges in public schools. The purpose of this research was to identify the teachers´ hypotheses concerning the difficulties in learning at school and to analyze some aspects underlying the explanations provided by those teachers. Information was collected by means of 133 questionnaires and focus groups with teachers working on Elementary School level. Thematic analysis of contents and the frequencies of words were used in order to systematize and interpret the results. Most teachers, 88 percent, explain that difficulties in learning are related mainly to the lack of support and encouragement by the student`s families; 69 percent highlight aspects associated with students, such as lack of interest, of attention, of preconditions, in addition to indiscipline and emotional problems. They also emphasize issues pertaining to public policies: reduced age for registration in Elementary School without the corresponding structural adaptations in the school, inadequate teaching materials, and continued academic progression without supporting the children with learning difficulties. We have concluded that even if such explanations, at a first look, indicate prejudices against families and students, upon careful examination, they reveal contemporary symptoms of the consumerist society, dissonances in the family-school relationship, and depreciation of education. What teachers say is an denounce of a market of handouts and workbooks, beside some types of training which dismiss their knowledge. The training courses, nicknamed teacher deformations by teachers, seem to be out of the context of the concrete problems faced by the public schools. Finally, what teachers say also bespeak the universe of mediatic manipulations towards the interests and values of families and students.

Key words: Academic failure; Learning difficulties; Literacy; Teacher training; Media and childhood

O fracasso escolar no Brasil é crônico e complexo, portanto, torna-se relevante uma escuta atenta daqueles que lidam com os desafios cotidianos das escolas públicas. Esta pesquisa teve o objetivo de identificar as hipóteses docentes sobre as dificuldades na aprendizagem escolar e analisar alguns aspectos subjacentes às explicações dadas por eles. A coleta de informações foi realizada por meio de 133 questionários e grupos focais com professores do Ensino Fundamental I. Utilizou-se a análise temática de conteúdo e frequências de palavras para sistematização e interpretação dos resultados. A maioria dos professores, 88%, afirma que as dificuldades de aprendizagem estão relacionadas principalmente à falta de apoio e de estímulo das famílias; 69% destacam os aspectos relacionados aos alunos, como falta de interesse, de atenção, de pré-requisitos, além de problemas emocionais e de indisciplina. Ressaltam, ainda, questões pertinentes às políticas públicas: redução da idade para matrícula no EF sem as devidas adaptações estruturais na escola, material didático inadequado e a progressão continuada sem apoio às crianças com dificuldades. Concluímos que tais explicações se, em um primeiro momento, sugerem preconceitos quanto às famílias e alunos, em uma análise criteriosa, revelam sintomáticas contemporâneas da sociedade de consumo, dissonâncias na relação família-escola e desvalorização da educação. As falas dos professores denunciam um mercado de apostilas e de formações que desqualificam seus saberes. Os cursos formativos, apelidados de deformações docentes, parecem descontextualizados das problemáticas concretas enfrentadas pelas instituições públicas. Por fim, as falas também evidenciam o universo de manipulações midiáticas dos interesses e valores das famílias e dos alunos.

Palavras-Chave: Fracasso escolar; Dificuldades na aprendizagem; Alfabetização; Formação docente; Mídia e infância

Introduction

The difficulties in the school learning process in Brazil have been explained as a result of physical or psychological deficiencies of children and their families. In the 1980s, Patto’s studies about academic failure open a new perspective in order to understand the effects of social inequalities on Brazilian basic education. The research results showed an educational system that produces obstacles to its own goals, especially, the technical pedagogical work, the dehumanization of personal contacts, and ultra-generalizations that are easily seen in prejudices. Patto (2000, p. 414) concludes that academic failure would be “managed by a scientific discourse that, shielded in its competence, naturalizes this failure in the eyes of all those involved in the process.”

Academic failure has also been explained by sociological theories, mainly by the lack of cultural capital by poor families, which is another version of class bias. Charlot (2005) considers that Bourdieu’s research on cultural capital has been used in inappropriate ways. He argues that it is not enough to be the child of someone inherit such capital, because cultural heritage isn’t automatically transmitted, “it is important to study, making an intellectual effort. So, to ‘transfer’ this ‘cultural capital’ to your children, you have to work hard” (CHARLOT, 2005, p. 39).

One major criticism of Charlot is the media use of the term academic failure, usually applied in a broad and simplistic way. According to Charlot (2008, p. 16) “Academic failure does not exist; what do exist are students who fail, situations of failure, school histories that end badly.” In his analysis, school failure can be understood, at first, as the difference expectations regarding the results of student performance, however, it is not a mere difference: « it is an experience that the student lives and interprets and that can become an object of research” (CHARLOT, 2008, p. 17).

Generic and simplistic explanations have also been adopted by psychologists. In general, psychologists tend to consider learning difficulties as a result of family issues, or as intrapsychic and psychodynamic problems, thus missing others factors concerning the child›s schooling process (SOUZA, 2000; SOUZA, 2010). This is a “psychologism” that reinforces the feeling of guilt in students and their families.

A literature review about school failure was conducted by Angelucci et al. (2004) to study the publications from 1991 through 2002 and they identified that the explanations were similar to those highlighted by Patto (2000), which blamed children and their relatives. However, there was an increase in researches which saw teachers as the cause of academic failure due mainly to their formative gaps and prejudices.

Souza (2010) draws our attention to several factors concerning Brazilian educational public policies that have resulted in failed teachers and students. Regarding the way schools operate which produces failed teachers, the author highlights: authoritarianism in implementing education polices; high teacher turnover along the school year; unorganized school routine; low salaries; absence of systematic teacher training and discussion of pedagogical practices; teachers´ knowledge being disqualified, and scarce supporting infrastructure. According to Prioste (2011) the lack of support for teachers makes them feel lonely and the expectancy of having their student´s problems explained by psychological reports.

Specifically in relation to difficulties in learning how to read and write, Mortatti (2013) considers that the child´s inability to learn and the teacher´s inability to teach prevail among the explanations, as well as the fact that families do not really get involved with their children’s schooling. These explanations are very limited as argues the author. Mortatti (2016) emphasizes that, over the last three decades, constructivist approaches have become hegemonic in teacher training policies as a promise to overcome illiteracy. But these promises are far from being fulfilled: “...good political-pedagogical intentions, initially announced by the advocates of constructivism, have been left behind due to functional illiteracy of Brazilian generations (MORTATTI, 2016, p. 763). She has severely criticizes the teacher training model oriented by a procedural perspective, especially when the teacher’s role is reduced to being a “facilitator”, some who “diagnoses/evaluates” or “promotes” education focusing on “how to do” or on “learn to learn”.

In the 1980s, Patto (2000) conducted studies that analyzed the histories of retention and saw them as indicators of school failure. Sometimes later, public policies of continued progression were implemented and the retention practically was banned, which resulted in academic failure becoming more and more disguised. In teachers’ reports, we have frequently found complaints about a great deal of kids that advance in the school grades who are barely literate; some of them complete Middle School but can barely read and write.

Considering this failure, the market takes advantage in creating profitable mechanisms. Profit comes from teacher training, courses, handouts and the medicalization of the unsuccessful, especially teachers and students. As Collares and Moisés (2010) see it, although learning problems could have to do with biological factors, the pharmaceutical industry takes an interest in expanding its business to include children, so a great deal of what has been called learning disorders is related to difficulties faced by normal and healthy children.

In compliance with this perspective, in the questionnaires I chose to use the expression “learning difficulties,” as schooling involves transitory difficulties that should not be treated, a priori, as either diseases or psychological disorders, nor as failures. Assumption is that most learning difficulties could be overcome by dealing more carefully with families and children; greater support for teachers; changes in the educational context and pedagogical strategies. This does not mean to deny that some cases can benefit from psychological, medical or other health care professionals. In this regard, the importance of understanding the school contexts and the problems daily faced by teachers must be stressed.

According to Souza (2010), prejudice against public school teachers has increased: “these professionals have been held responsible for all kinds of problems and seen as incompetent, poorly trained, selfish, and scarcely committed to their students” (SOUZA, 2010, p. 241-242). A biased view does not contribute towards an in-depth view of how complex teaching and learning are, especially in public schools. Thus, this study prioritized to attentively listen to teachers in order to understand how they see and explain the school difficulties their students experience, as well as to analyze some factors underlying the main points they make.

Development

This paper presents part of a broader research, named The televisual prostheses and school learning3, whose objective was to identify possible effects of children’s televisual habits on their educative processes. The results showed here are limited to the first stage of the study aimed to investigate the teachers´ assumptions in regard of learning difficulties

Imbued in a heuristic perspective, before questioning whether children’s television habits could impair or improve school performance, I tried to understand which factors teachers deemed most relevant. Inspiration came from the Grounded Theory, which starts with the interpretations given by those involved in a problem, and then investigate the processes underlying the statements and explanations provided (TAROZZI, 2011). Although the study was not intended to produce a theory of its own, a qualitative exploratory-explanatory approach guided the weaving of more detailed explanations. I see knowledge “as a process that is socially constructed by the subjects in their daily interactions, while acting in a reality which they transform and are transformed by it” (ANDRÉ, 2013). Hence, the investigative procedures not only have sought to explore the teachers´ assumptions on learning difficulties, but also to further analyze their arguments by unveiling some crucial aspects of the issue.

This research was conducted with Elementary School teachers, from municipal public schools in the city of Araraquara. Information was collected in two stages: first, questionnaires were applied during a teacher training event. In the second stage, focus groups were held in two schools, where 10 elementary school teachers participated in each group, 20 teachers in total. The purpose of the talk was to define what reasons teachers saw as the causes school learning difficulties; each focus group took an hour. Notes were taken in research diary to record the conversation in the focus groups.

Preparing the questionnaire included a pre-test with three teachers who contributed with suggestions to clarify the questions. The first part of the questionnaire was meant to identify how long the professionals had been teaching, how many classes each teacher taught; the average number of students per class; and the number of children going having difficulties in their learning. Th second part focused assumptions guided by the question: “In your view, what would be the main causes of school learning difficulties? In addition, a question was included to look into the influence television devices had on school learning. This paper covers only the first question.

For the purpose of analysis, the open-ended questions were selected and then a floating reading of the answers was conducted. Next, questionnaires were selected to be included in the research sample, resulting in 133 participants: 30 first-grade teachers; 29 second-grade teachers; 27 third-grade teachers; 22 fourth-grade teachers, and 25 fifth-grade teachers. It is important to mention that the total number of teachers in that public Elementary School was 243. This means the sample represented 54.73 percent of the school teachers.

Questionnaires were selected based on the following exclusion criteria: incomplete forms; questionnaires answered by educators teaching more than one class, or those working in special education and physical activities. Moreover, teachers working as a principal, an educational counselor, or as a supervisor were also disregarded. The inclusion criteria were: teachers who had one class per year and questionnaires with most of items completed. The purpose was to have a more homogeneous sample, so that it would be possible to compare teaching views in different stages of schooling.

Information was systematized based on content analysis as used by Bardin (2009). This approach addresses the need for greater rigor in research. The starting point was an analysis of theme/category contents, structured by frequency of words in each topic.

Answers were organized in tables using Excel; teachers´ real names were replaced by alphanumeric codes: family-related aspects; student-related aspects; key aspects of educational system, school context, and methodological approach; socioeconomic and cultural aspects; lack of external support (e.g.: lack of diagnosis, need for psychological or medical support); and, finally, teachers do not feel that education or themselves are appreciated. The data categorization required an evaluation of the sentence context in order to identify its connotation. For that reason, some answers were divided to be included in more than one category, e.g. the response from teacher C17: “Lack of interest and commitment from parents to their children and the school. Students’ immaturity and indiscipline. Further social problems”. In breaking responses up, a portion was taken as family aspects; another student-related; and a third part as social aspects. Excel was used to make graphics and count word frequency; additionally Nvivo software was used to create illustrative images in word cloud format.

Results and discussions

Most teachers (64.66 percent) had been working in elementary school for 11 years or more. 39.10 percent had between 10 to 15 years of experience, and 25.56 percent, more than 16 years. Most teachers showed they had a satisfactory professional experience, and only 15 percent of them had worked for less than two years. Such experience may be considered an advantage, assuming that teachers, by now, should have overcome the early adaptation process and were able to see themselves producers of knowledge, as proposed by Nóvoa (1991). Nonetheless, results have demonstrated that both strict educational system and the depreciation of the teachers´ hands-on knowledge contributed to make teachers feel hampered in their pedagogical autonomy and frustrated with their profession.

In relation to learning difficulties, 96.24 percent of teachers mentioned they had students with such problems: 6.8 pupils in average per classroom with approximately 24 children. As shown in Table 1, 5,96 children out of first-graders showed learning difficulties, an average value that it inferior in fifth grade, where this was the case of 8.04 students per class.

Table 1 Estimation of students with learning difficulties per class

| Grade | Total estimate of students with learning difficulties | Average students with difficulty per class |

|---|---|---|

| 1º | 155 | 5,96 |

| 2º | 184 | 6,57 |

| 3º | 148 | 5,92 |

| 4º | 169 | 7,68 |

| 5º | 177 | 8,04 |

| Total | 833 | 6,834 |

Source: research data.

In the focus groups, the teachers were not clear about what they should expect from their students in terms of learning at each stage, because, despite the results verified in the evaluations, all students should be promoted to the next grade due to the policies of continued progression. As teachers see it, the obligation of teaching children to read and write by the age of 8, according to the Proper Age Literacy Pact [Pacto da Alfabetização na Idade Certa – PNAIC] (BRASIL, 2012), was incompatible with the proposed methodologies and teaching work conditions. Additionally, PNAIC had an ideal in mind, far from the reality of the poor-grass-roots areas. Therefore, PNAIC has not offered plausible learning parameters.

Regarding referrals for academic support activities or for a diagnosis by a special education team, there was a rule in schools that prevented from referring first- and second-graders. Most teachers disagreed as they believed that learning difficulties should be identified in the beginning of the literacy process because more likely that those problems would be properly overcome. In addition, there was a lack of teachers to offer support to difficult children. Consequently, in the following grades, the number of children with learning gaps increased to make the situation worse along the years.

The highest percentage of children with learning problems was concentrated among fourth- and fifth-graders, confirming other studies on academic failure in which referrals to psychology help were more frequent at this stage, when the children were approximately 9 years old (BRAGA; MORAIS, 2007).

Results of the analysis of the teachers’ responses are presented as follows, regarding the major causes of learning difficulties. It should be note that categories were created a posteriori, drawing from the questionnaires and supplemented with information obtained in the focus groups.

The explanations about difficulties in learning at school

The results show that teachers think the cause of the difficulties in learning are associated with the families and children themselves, in line with studies by Patto (2000), Mortatti (2013), and Prioste (2011). In counting the words “family” [família] or “familiar”, they appear 105 times in the responses to the questionnaires. Thus, 87.97 percent of teachers mention the family as the main factor related to the causes of difficulties in learning at school. Although most teachers added up other causes, 16.54 percent see only the families as the origin of the problem.

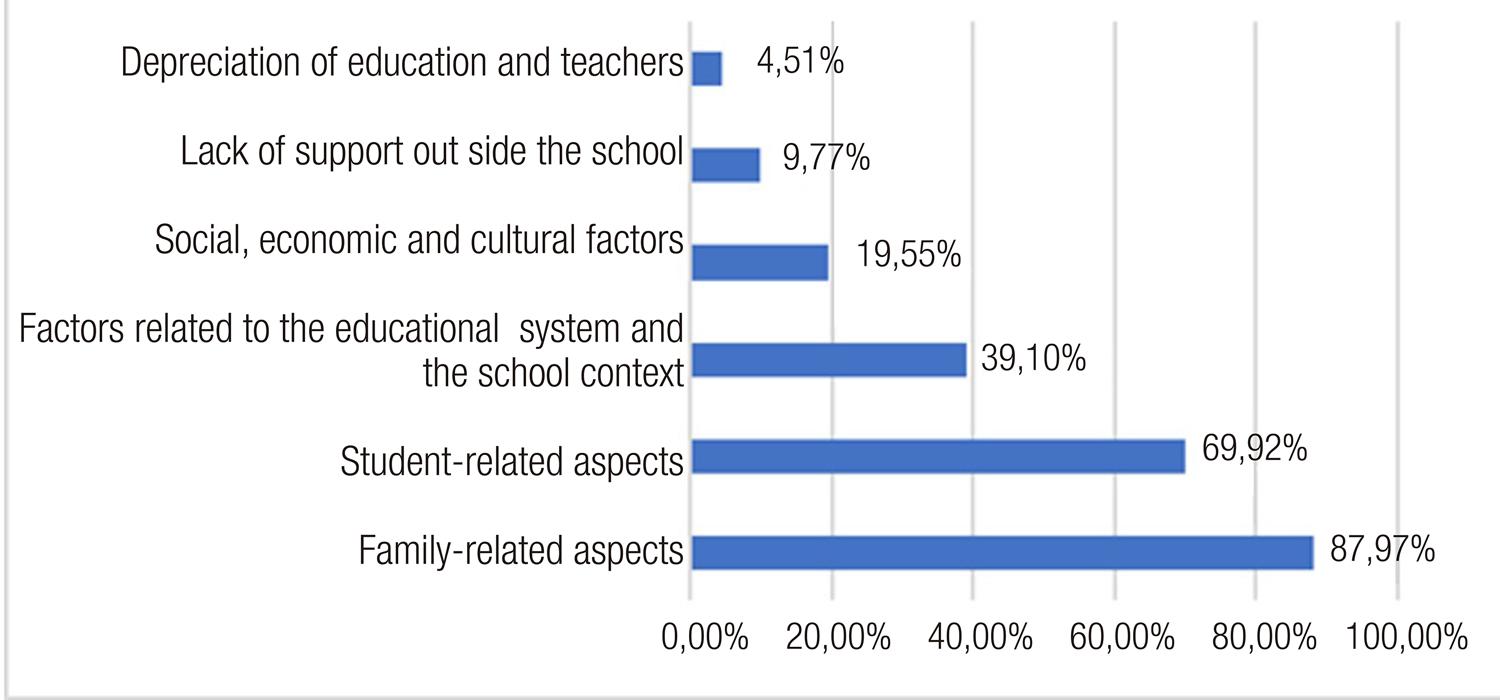

The second reason most cited by teachers involve aspects related to students, mentioned by 69.92 percent of them; the third cause concerns the educational system, the school context, and theoretical and didactic aspects, indicated by 39.10 percent; the fourth reason is associated with social factors, such as socioeconomic and cultural issues, marked by 19.55 percent; next, factors related to lack of support outside school, mentioned by 9.77 percent; and, finally, depreciation of education or teachers, in the response of 4.51 percent, as shown in graph 1.

Family-related aspects

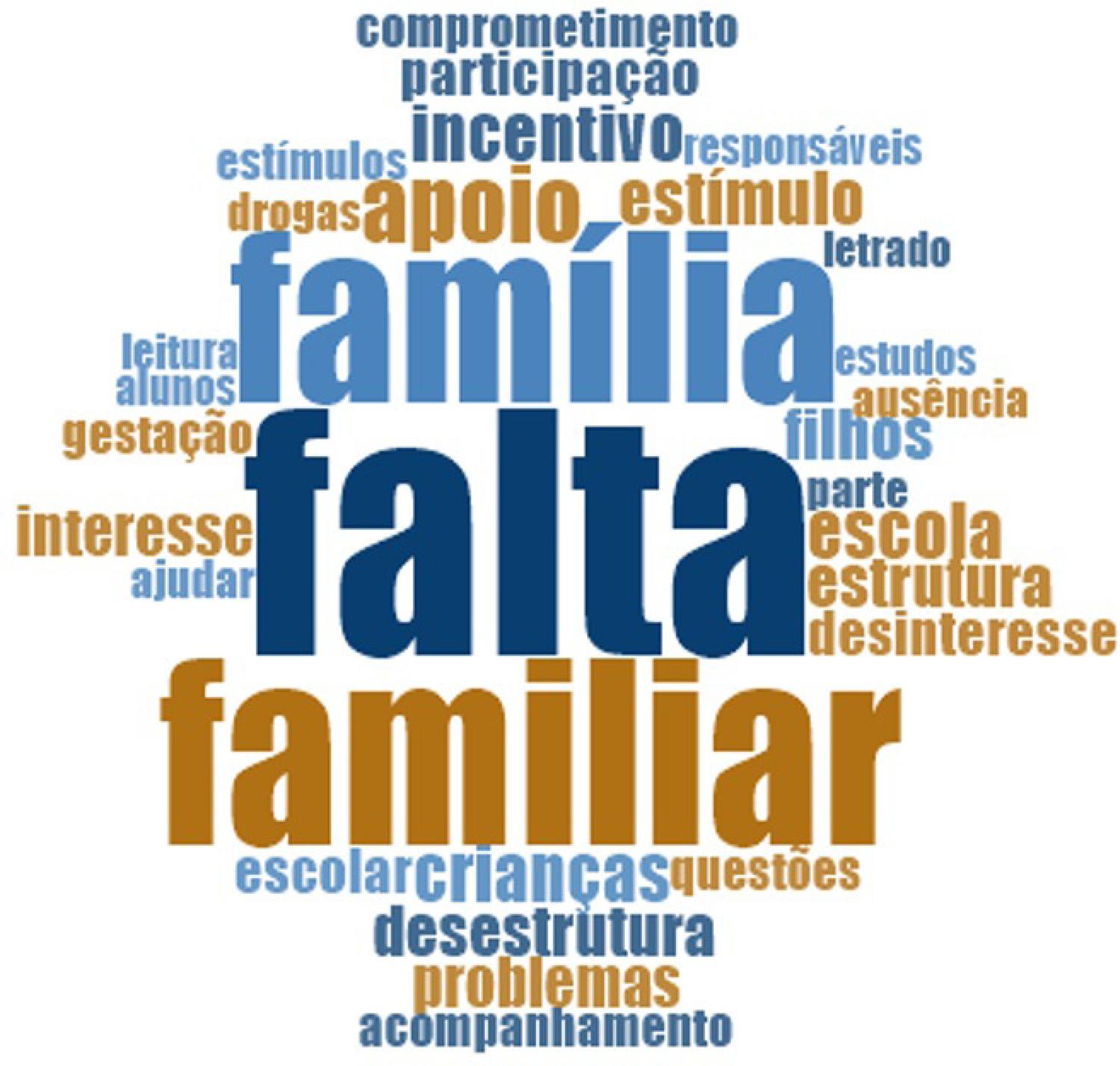

Teachers believe that learning difficulties result especially from the lack of interest and support by family members when dealing with school issues of their children; dysfunctional families are also mentioned. Absence [falta] is the key word to understand how teachers see their students´ parents, appearing 78 times. Both encouragement [incentive] and stimulus [estímulo], used interchangeably, came up 21 times. The word support [apoio] was mentioned 18 times. Both disorganized and dysfunctional families counted 18 mentions. Loss of interest [falta de interesse] and disinterest at all are highlights in 15 quotations, as well as the lack of commitment and monitoring. In the focus group, a second-grade teacher moaned: “the families don’t care. This year, I have been everything but not a teacher; I have served as a nanny and a rescuer. I have broken up fights all the time. How am I going to be able to teach in such reality?

Source: research data.

Figure 1 – Most frequent word cloud in the category of family-related aspects4

These results indicate that teachers raise some expectations: families should provide support and encourage their children; they should monitor school activities and commit themselves to the school. In other words, teachers expect parents to teach discipline rules and academic motivations which they possibly never received themselves. This denotes a romanticized view of the family, particularly when learning difficulties are seen as caused by family disruption. A study by Sarti (2007) involving families facing social vulnerability showed that “the first characteristic to emphasize concerning poor families is their network configuration, which contradicts the current notion of a core family” (SARTI, 2007, p. 29). This idealistic way of seeing the family as a separate unit makes it difficult projects with a network of child care services beyond the mother and the father.

Still talking about family involvement, nine teachers complained about students frequently skipping class: “absenteeism is a great nuisance”, wrote a teacher. In the focus groups, they said absenteeism was caused by the family being scarcely interested in the school life, by education being culturally depreciated and, especially, parent having alcohol and drugs abuse.

Why do teachers tend to blame families for academic failure? As Patto (2000) puts it, a racist scientific perspective may have contributed to teachers having a negative view of poor families, seeing in them the origin of all moral and psychic defects. In addition, blaming families would be a way for teachers to get away with their pedagogical responsibilities. According to Charlot (2005), the student’s academic failure leaves the teacher in narcissistic pain, which is intensified as failure happens again, despite the attempts and efforts to help the child overcome his or her difficulties. In the face of frustration, explanations focusing on the family´s sociocultural deficiency are emphasized. Prioste (2011) and Souza (2010) highlight the teacher’s feeling of powerlessness, the lack of support and spaces to rethink their practices and difficulties, as it might lead simplistic explanations.

However, it is necessary to be careful with generalizations so that teachers can now be targeted with prejudice. Getting close to teachers, I found teachers who were looking for greater involvement of parents in the educational process. There were teachers utilized different strategies to help children overcome their difficulties; some would even prepare learning materials with their own money, designed handouts and educational games, and also spend their planning hours to provide academic support.

In this regard, I will highlight some difficulties reported by teachers, which should be better examined in order to propose educational actions and public policies: the increased number of students whose parents are teenagers; more families facing alcohol and drug abuse, which may be related to domestic violence; many children have been raised by grandparents or relatives unwilling to play this role; a great deal of families seemingly more concerned with buying things than provided good education to their children; parents watching TV or engaged in cell phone apps most of the time, without talking to their children; families allowing children to be exposed to violent media content or sexuality; the school being seen not as a place for education but rather some a kind of place to keep children away. In addition to all that, it is also important to emphasize how teachers see the way public managers treat families, that is, with patronizing measures instead of holding them accountable for the rights and duties.

Dufour (2005) argues that the major problem for teachers is a different profile of children coming to school, which he calls homo zappiens, in reference to the habit of zapping, the difficulty of tolerating frustrations, and the exposure to a continuous flow of fast images. He says that “children who come to school today are often children stuffed with television since their earliest age. That is a new anthropological fact, whose comprehensives has not yet been assessed” (DUFOUR, 2005, p. 120). As he sees it, children spend more time in front of screens than with their family, which may have effects on the symbolic capacity. Furthermore, when they come to school, kids encounter a discursive environment of generational denial, that is, a laissez-faire pedagogy: the teacher´s authority becomes increasingly questionable on behalf of a allegedly democratic education based on an ideal of a happy child without frustration.

Therefore, if teachers see the cause of learning problems mainly in the families, it would be important to help them understand the forming of values and the community´s interests as a whole instead of looking at their arguments only as an issue of repetitive complaints; public policies to help the schools plan educational activities with families should also be proposed.

Student-related aspects

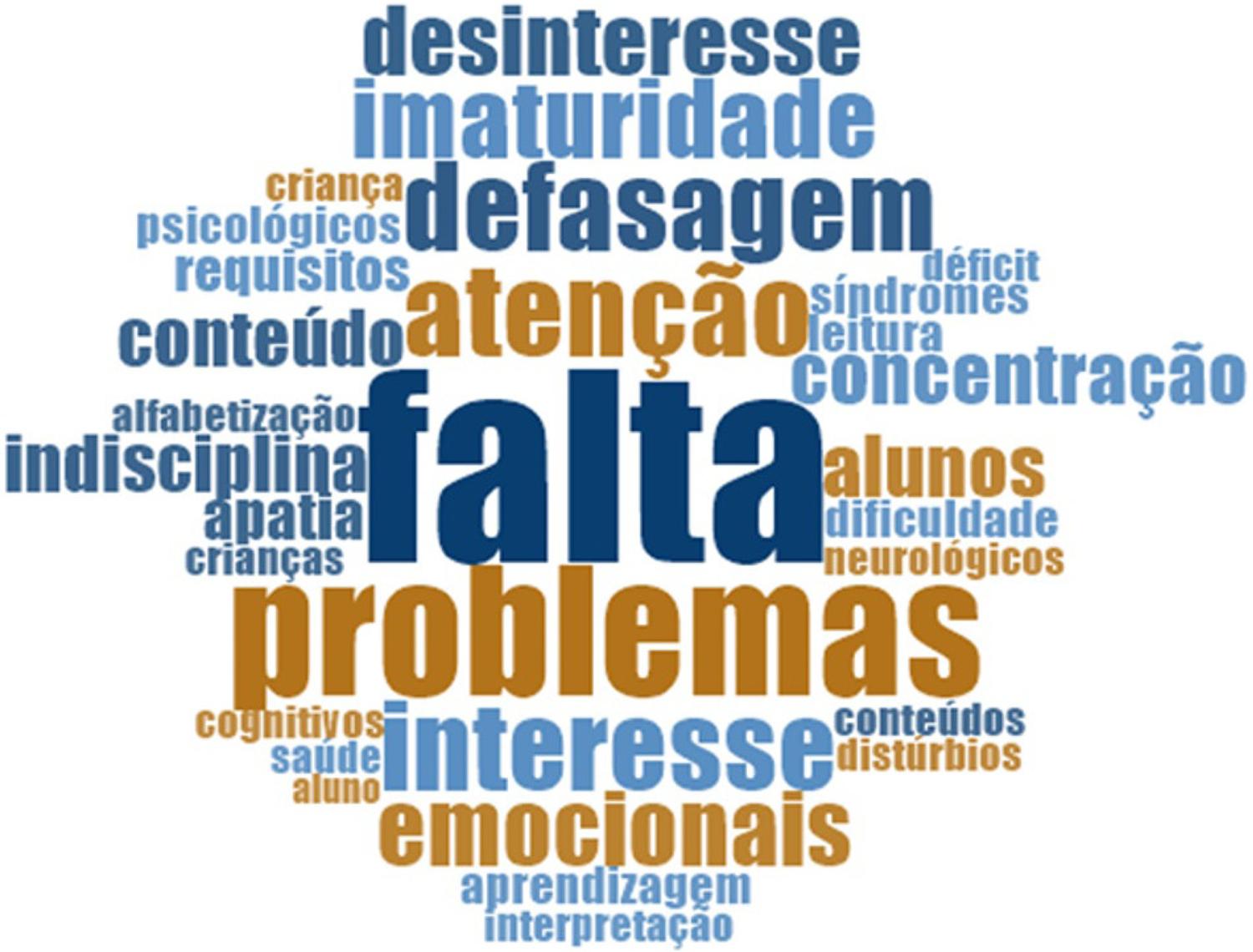

In addition to the scarce involvement of families towards the school, teachers also think children are deprived of preconditions and skills which prevent school learning or make it difficult. 69.92 percent of the participants in the study associate the causes of the learning obstacles with the students’ deficits, stressing the lack of interest, attention, concentration, discipline; as well as the loss of maturity, prerequisites, background, beside emotional problems. The cluster of words standing out has to do with lack of interest [falta de interesse] or desinterest, mentioned 36 times. These are some examples found in the questionnaires: “immaturity, lack of interest, absence of prerequisites” (a first-grade teacher); “no interest and apathy in school” (a second-grade teacher); “unmotivated child who has already a very specific discrepancy preventing him or her from advancing” (a fourth-grade teacher); “loss of interest, content-related discrepancy” (a fourth-grade teacher).

Source: research data.

Figure 2 Most frequent word cloud in the category of student-related aspects5

By carefully reading the questionnaires, it could be seen that first-grade teachers link the child’s loss of interest to immaturity, lack of attention and preconditions. In the focus groups, teachers complained about the families who treated their children as babies and about preschools which did not manage to develop the alleged children´s abilities necessary for literacy.

In the third place, the mostly mentioned word was problem [problemas] appearing 25 times and found in phrases like: “cognitive and emotional problems”; “speech problems”; “discipline problems”; “psychological problems” as well as health-related problems. Some expressions stood out too: the lack of attention mentioned 16 times; lack of concentration, nine times; indiscipline, eight times; and apathy, nine times. The prevailing idea in the focus groups was that these problems should be solved by families or by psychological help, speech therapy, or medical care.

A situation was reported about child M., a third-grade student who could not read or write, is an example. His teacher described M. as “a very aggressive child, especially outside the classroom. He had been prescribed with controlled psychiatric drugs, but the mother had discontinued the medication on her own”. Others similar cases were raised in the focus groups, revealing expectations that drug treatments would tackle learning difficulties, as shown by Collares and Moyses (2010). By reviewing M´s case in detail, it was found that the family had a history of academic failures, especially the father. There was also a context of domestic violence and, finally, it came up that the boy used to spend the night playing violent games. In addition, he switched schools a few times and, once, he did not attend class for half a year because the family had moved to another house. Obviously, M’s situation added up a set of complex and adverse factors affecting his academic success.

Based on what teachers had said in the questionnaires and in the focus groups, some considerations are brought here to help understand what teachers perceive as the loss of interest by their students. The first aspect has to do with the change in the law concerning the age children must start elementary school; according to them, kids aged 6 or less years old have been enrolled but the schools still have not had their infrastructure facilities adapted accordingly. One teacher said: “kids have their feet loose, swinging in the air, as they cannot reach the floor”. They also say that neither the curriculum nor the learning materials had been adapted.

The reduction in the age for enrollment of children in Elementary School was due to the publication of Law 11.274 (BRASIL, 2006). This change in the law has generated controversy and some studies indicate that its implementation occurred without guaranteeing structural changes in schools, without curricular adaptations, training of pedagogical teams and with little clarity of their purposes. All of these factors have contributed to the perpetuation of the failures of literacy process (PANSINI; MARIN, 2011).

The second aspect to be highlighted in the responses is related to a potential lack of preconditions, not properly developed either within the family environment or in preschool. Teachers mention the lack of attention, concentration, memorization, motor coordination, as well as speech difficulties and cognitive problems.

There is a broad discussion regarding the role of early childhood education in developing psychic functions, and this is not the aim of this paper, however, it should be noted that, in Brazil, there is a long-term distinction between the role of the private and public kindergarten. Roughly, private kindergartens prepare and develop children´s skills so that they can be successful in elementary school, while the public preschools just keep children safe while their mothers go to work. Research conducted in the city of Araraquara in public preschools found that pedagogical practices were aimed at providing relief, based on spontaneity and common sense, where pedagogical activities were poorly planned (SILVA; HAI, 2012; BARBOSA; SILVA , 2016). Possibly, the lack of systematic pedagogical planning kindergarten may adversely affect the development of some important skills needed to learn how to read and write. However, perhaps the term precondition is restraining and reductionist, and reveals that elementary school teachers idealize what would be a child ready to become literate.

In addition to the previously mentioned aspects related to preschool deficiencies, it is necessary to discuss the activities children perform within the family context, as they can impair the development of psychological functions. Over the last few years, there has been a great deal of studies on the excessive hours children spend in front of screens which affect their attention, concentration, and speech skills (DUFOUR, 2005; DESMURGET, 2012). The literature review concerning the impact of screens on child development, conducted by Esseily et al. (2017), highlights the toxic effects of televisual devices, especially on language development, attention span, and parent-child interaction. There is a correlation between attention disorders and how early a child begins watching television. In a previous study, I identified that the main activities children do at home were related to some screen device (PRIOSTE, 2016).

A third aspect to be emphasized is the child’s interest in school activities. According to Desmurget (2012), televisual devices can not only affect the development of psychic functions but also interfere with the child’s interest in activities which demand a cognitive effort. Teachers reported that the children’s interests were aimed at consumer objects, branded products, as well as TV soap operas, cartoons, and digital games.

Another highlight comes from something teachers had repeatedly stressed out in the discussions: the learning material being inadequate to meet the children´s needs. In general, teachers said the first- and second-grade handouts did not focus on literacy. All content basically assumed that the child had already acquired the ability to read, which brought a big problem for the teacher who, in addition to preparing the literacy materials, had to make students fill out the exercises in the handouts as if they were already literate. That was because educational management required that class contents had to be written down in the records. Such mandatory demands may have led to the fact some third-graders were said to be able to copy texts only (and not write by themselves).

In the next topic, problems concerning the handout system implemented by city´s education authority are examined together with the teachers feeling powerless because their pedagogical knowledge is disqualified.

Finally, still regarding to the student issues, teachers mentioned three types of disorders: emotional (15 times), psychological (5 times), and neurological (3 times), they also referred to indiscipline and lack of rules (11). Emotional problems or psychological disorders are nebulous expressions. However, one may assume teachers meant children who were raised by neglectful adults, and at the same time, in an individualistic and consumerist way without any sense of community or tolerance to frustration. Besides, it is important to consider traumatic experiences resulting from family and community violence.

Concerning indiscipline and lack of rules, one cannot say they are inevitably related to a child’s emotional problems, as it is necessary to take into account that the school context should focus on the meaning of what it to be a student, clarify the importance of civility in collective spaces, with rules that are clear shared by all. Freller’s (2001) studies on school indiscipline stress how important is to understand and meet some of the children´s psychological needs, including the need for belonging, acceptance, and putting down roots.

Factors related to the educational system and the school context

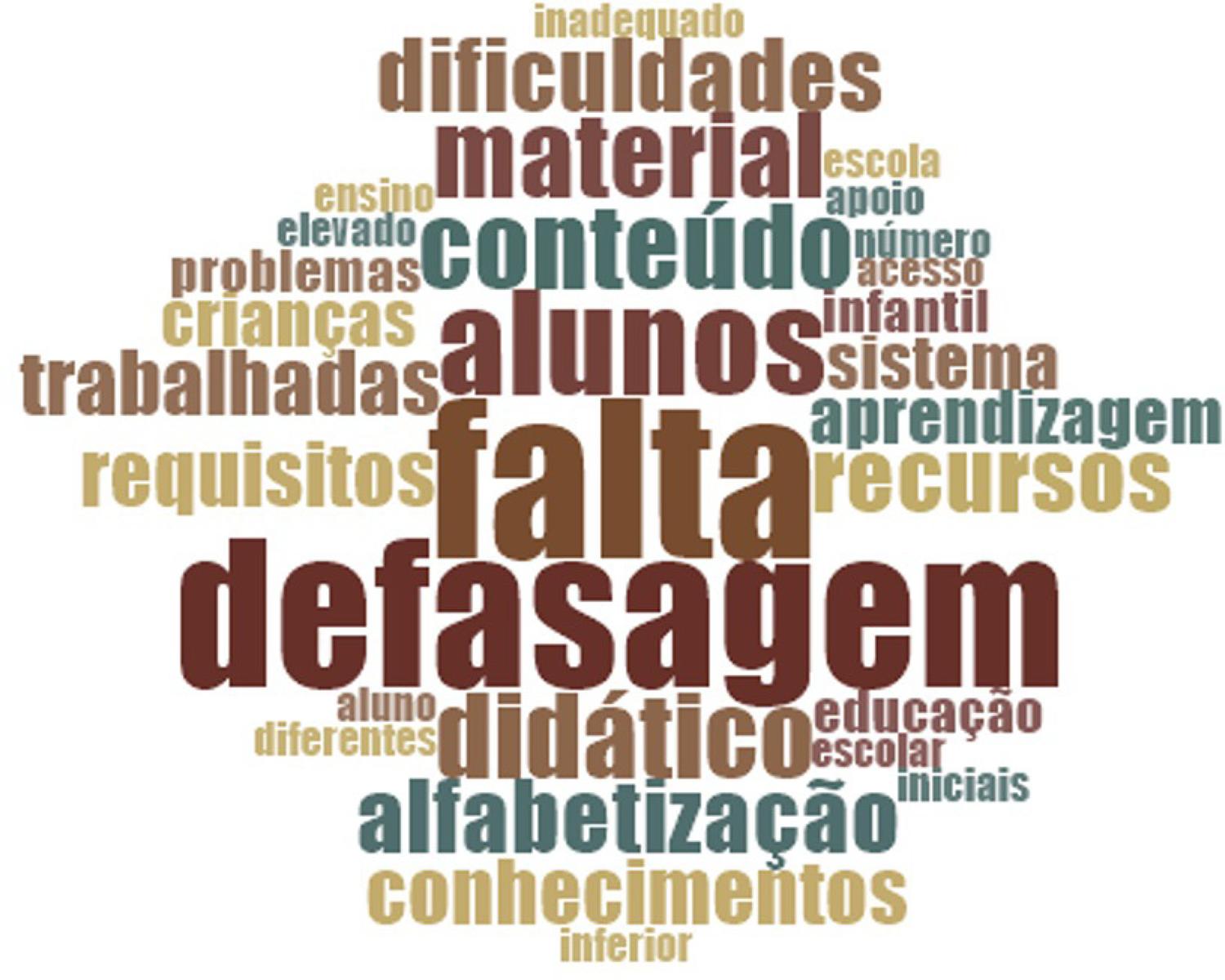

The questionnaires show that 39.10 percent of the teachers include the dimension of the educational system, the specific context of each school, teacher training, and the theoretical/methodological approach as factors that lead to learning difficulties. These aspects were widely discussed in the focus groups. More specifically, teachers complained they were not free to choose the pedagogical approach of their like. They also said that the training provided by the National Pact on Literacy at the Proper Age (BRASIL, 2012) brought no significant contributions to achieve an effective classroom practice; on the contrary, such trainings usually caused disturbance, and that was why they were called teacher deformation. The market for in-service ongoing training was disappointing for teachers because they were often out of contextualized, based on a Eurocentric and idealized child psychology, with nothing to do with today´s Brazilian children living in urban poor fringes, with a history of racism, exclusion, and deprivation. Such trainings usually ignored how complex are the factors involved in teacher/student relationships in public schools.

Source: research data.

Figure 3 – Word cloud of most frequent word cloud of aspects related to the educational system and school context6

Another key aspect concerns the handout-based methods sold to the local education authorities with no careful examination by the teachers and lacking scientific evidence of being effectiveness to the students at stake. A first-grade teacher said: “the material provided by X7 was implemented due to political interference which killed off the teacher’s pedagogical work.” Teachers said that, before the handouts were adopted, they were excited to design their own literacy materials and, afterwards, they felt frustrated because their research had been interrupted and their favorite textbooks were taken away. A second-grade teacher criticized: “this material was forced on us and we could no longer utilize any alternate methodology”. A third-grade teacher said: “we had to keep our favorite textbooks in the kitchen cabinets to hide them from the management staff because they came by to collect all of our materials”; another teacher told that, after this event, she began hiding her books in her own car´s trunk.

On the literacy methodological aspects, most teachers told their experiences were not taken into account and that the lack of a teaching view going “from the parts to the whole” impaired the child´s learning. For Morais (2014), the literacy guidelines set forth by the Ministry of Education over decades have disregarded international research on how to be methodological effective in teaching how to read and write. It is a problem from an ideological perspective that prevails in public policies, which limit teacher autonomy. The accounts provided by the teachers also confirm studies by Mortatti (2016) by showing that the constructivist promises did not yield significant answers to the problem of academic failure affecting literacy, overshadowing the teacher as a mere supporting, facilitating, or diagnosing agent.

It should be underlined that in 2018 the city´s Education Department reopened the debate on learning materials, allowing teachers to choose the textbooks they would like to work with the following year. The importance the research I have being doing is clear to make teachers feel confident in fighting for greater pedagogical autonomy.

Other aspects

Social, economic and cultural factors came up in 19.55 percent of responses. Some were broad, such as “social problems” or “social factors”, others were more specific: “little experienced in cultural settings “, or “lack of a literacy environment”. This brings us back to Charlot (2005) and the mistake looking at school failure as exclusively the result of scarce cultural capital. Basic deprivations were also mentioned, as for example: “there are children who do not get enough [food], so they often go to school without having had lunch and breakfast.”

Concerning the lack of support outside the school, indicated by 9.77 percent of respondents, the highlight was “lack of a diagnostic”, “delay in referrals”, and the fact that children were not assisted by competent professionals. These aspects were stressed in the focus groups and reveal that teachers strongly expect most of the children’s problems can be treated by psychologists, speech therapists, and doctors.

The final issue was education being depreciated, appearing in the answers of 4.51 percent to the questionnaires. The most frequent phrases were: “depreciation of schooling”; “depreciation of the teacher and the role played by the school”; “schools have lost their meaning.” Less emphasized in the questionnaires, this perspective was constant in the focus groups. Some teachers repeated that the school had become “a warehouse to keep children away”, because the families did not prize education and educational managers did not see the school as an educative place. There were teachers who felt depreciated when they were prevented from using a teaching approach that they thought would work better for their students. Some literacy teachers felt undercover because they had to hide the work they were secretly doing to teach literacy using their own learning materials. They felt depreciated when their assessments were not taken into account, when they were not heard about the problems with their classes; when they had no support for inclusion cases; when they tried, on their own, to help a family with difficulties, ignored by the school or education managers. Finally, they felt depreciated due to their salaries and the need to take more classes, facing an overload of work and demands.

Conclusions

The debate about academic failure in Brazil is wide-ranging, complex and multifaceted, especially when it comes to public education. That is why it is essential to understand the perspective teachers have in experiencing complicated problems, keeping in mind that most of the time their perceptions and knowledge are disqualified by the educational management, by the academic research, and also by continued training.

The questionnaires revealed that 96 percent of respondents believed they had children with learning difficulties in their classrooms, an estimated average of 6.8 students per class. Around 88 percent of teachers said difficulties were caused by family issues, mainly due to loss of interest and lack of parental support. Secondly, there were student-related factors (69.92 percent), arising from lack of interest, attention, preconditions, in addition to emotional and discipline problems. The third cause included factors associated with the educational system, mentioned by 39 percent. In the fourth place, socioeconomic and cultural issues were mentioned by 19.55 percent of respondents. Other aspects concerned lack of support outside the school (9.77 percent) and, last but not least, depreciation of education or teachers (4.51 percent). The latter categories were significantly emphasized in the focus groups even though they barely appeared in the questionnaires.

Although, at first, the results of this research point to a repertoire of stereotyped explanations that mainly blame families and children for learning difficulties, a thorough and in-depth analysis of questionnaires and focus groups seems to show that teachers were not satisfied with the public education policies at the federal and local levels. At the federal level, three aspects were highlighted: the lowered age to enroll children in elementary school, dropping from 7 to 6 years old, without both structural adaptation of school facilities and neither methodological changes; discontentment with the so-called automatic promotion; and they also criticized the theoretical framework of and the trainings provided by National Plan for Literacy at the Proper Age, the latter being ironically called teacher deformations.

Regarding municipal public policies, teachers complained about not being free to choose the theoretical-methodological basis for their work, so that there was substantial dissatisfaction in relation to the learning handouts purchased by the local authorities. Lack of support for students with learning difficulties also came up, as students were automatically promoted to the next grade, adding up gaps year after year. Finally, they questioned the style of public management towards the families, as patronage prevailed and it did not help parents to be more committed to their children’s education.

Despite any prejudices teachers may have towards families and children, their explanations reveal structural problems in public policies being enforced with little recognition of teachers´ experience and knowledge; they denounce the existence of a market for handout materials and trainings that are out of context and do not meet the real needs of public schools. They also denounce the mainstream media of manipulating the taste and interest of children and their family members. Such manipulations are aimed at narcissistic satisfactions through consumerism as a way to guarantee some sense of belonging and social recognition.

Conclusion is that the diagnostic greatly expected by teachers should not focus on a specific student, but should rather include the whole school community. Who are the children beginning elementary school? What are their daily routines and habits? Who are their families, that is, whom can these children count on? What are their family interests and values? Are there any histories of academic failure in these families? What is the meaning of studying, going to school for these families?

REFERENCES

ANDRÉ, Marli. O que é um estudo de caso qualitativo em educação? Revista da FAEEBA – Educação e Contemporaneidade, Salvador, v. 22, n. 40, p. 95-103, jul./dez. 2013. [ Links ]

ANGELUCCI, Carla Biancha et al. O estado da arte da pesquisa sobre o fracasso escolar (1991-2002): um estudo introdutório. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 30, n. 1, p. 51-72, jan./abr. 2004. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Eliza Maria; SILVA, Janaína Cassiano. O programa cresça e apareça e a construção de uma proposta crítica para a educação infantil em Araraquara. In: CONGRESSO PEDAGOGIA HISTÓRICO-CRÍTICA: EDUCAÇÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO HUMANO, 1., 2015, Bauru. Anais... Bauru: Unesp, 2016. p. 1624-1636. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2009. [ Links ]

BRAGA, Sabrina Gasparetti; MORAIS, Maria de Lima Salum. Queixa escolar: atuação do psicólogo e interfaces com a educação. Psicologia USP, São Paulo, v. 18, n. 4, p. 35-51, out./dez. 2007. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.274, de 6 de fevereiro de 2006. Altera a redação dos arts. 29, 30, 32 e 87 da Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases para a educação nacional, dispondo sobre a duração de 9 (nove) anos para o ensino fundamental, com matrícula obrigatória a partir dos 6 (seis) anos de idade. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, Seção 1, v. 143, n. 27, p. 1-3, 7 fev. 2006. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria n.º 867, de 4 de julho de 2012. Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Pacto Nacional pela Alfabetização na Idade Certa. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, Seção 1, p. 22-23, 2012. [ Links ]

CHARLOT, Bernard. Da relação com o saber: elementos para uma teoria. São Paulo: Artmed, 2008. [ Links ]

CHARLOT, Bernard. O sociólogo, o psicanalista e o professor. In: MRECH, Leny. Magalhães (Org.). O impacto da psicanálise na educação. São Paulo: Avercamp, 2005. p. 33-56. [ Links ]

COLLARES, Cecília Azevedo Lima; MOYSÉS, Maria Aparecida Affonso. Dislexia e TDAH: uma análise a partir da ciência médica. In: CRP-SP. Conselho Regional de Psicologia de São Paulo. Grupo Interinstitucional Queixa Escolar. Medicalização de crianças e adolescentes: conflitos silenciados pela redução de questões sociais a doenças de indivíduos. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2010. p.71-110. [ Links ]

DESMURGET, Michel. TV lobotomie: la verité scientifique sur les effets de la télévision. Paris: Max Milo, 2012. [ Links ]

DUFOUR, Dany-Robert. A arte de reduzir cabeças. Rio de Janeiro: Companhia de Freud, 2005. [ Links ]

ESSEILY, Rana et al. L’écran est-il bon ou mauvais pour le jeune enfant? Spirale, Toulousse, v. 3, n. 83, p. 28-40, 2017. Dossiê: La grand aventure de Monsieur bébé: les bébés et les écrans. [ Links ]

FRELLER, Cintia Copit. Histórias de indisciplina escolar: o trabalho de um psicólogo numa perspectiva winnicottiana. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2001. [ Links ]

MORAIS, José. Alfabetizar para a democracia. Lisboa: Penso, 2014. [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Órfãos do construtivismo. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, Araraquara, v. 11, n. 4 (esp.), p. 2267-2286, 2016. Dossiê: Alfabetização: desafios atuais e novas abordagens. [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Um balanço crítico da “década de alfabetização” no Brasil. Cadernos Cedes, Campinas, v. 33, n. 89, p. 15-34, jan./abr. 2013. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, Antônio. O passado e o presente dos professores. In: NÓVOA, Antônio (Org.) A profissão professor. Porto: Porto Editora, 1991. p. 13-34. [ Links ]

PANSINI, Flávia; MARIN, Aline Paula. O ingresso de crianças de 6 anos no ensino fundamental: uma pesquisa em Rondônia. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 1, n. 1, p. 87-103, jan./abr. 2011. [ Links ]

PATTO, Maria Helena Souza. A produção do fracasso escolar: histórias de submissão e rebeldia. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2000. [ Links ]

PRIOSTE, Claudia Dias. Educação inclusiva: de que se queixam os professores de escola pública. In: GOMES, Mônica G. T.; SOUZA, Maria Cecília C. C. Educação pública nas metrópoles brasileiras. São Paulo: Edusp, 2011. p. 71-93. [ Links ]

PRIOSTE, Claudia. Tecnología, educación e innovación: riesgos y oportunidades. Journal of Engineering and Technology, Caldas, v. 4, n. 2, p. 72-83, 2016. [ Links ]

SARTI, Cynthia Andersen. Famílias enredadas. In: ACOSTA, Ana Rojas; VITALE, Maria Faller (Org.) Família, redes, laços e políticas públicas. São Paulo: Cortez: PUC/SP, 2007. p. 21-36. [ Links ]

SILVA, Janaína Cassiano; HAI, Alessandra Arce. O impacto das concepções de desenvolvimento infantil nas práticas pedagógicas em salas de aula para crianças menores de três anos. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 30, n. 3, p. 1099-1123, set./dez. 2012. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Beatriz de Paula. Funcionamentos escolares e produção de fracasso escolar e sofrimento. In: SOUZA, Beatriz de Paula (Org.) Orientação à queixa escolar. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2000. p. 241-278. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Marilene Proença Rebello de. A queixa escolar na formação de psicólogos: desafios e perspectivas. In: SOUZA, Marilene Proença Rebello de. Psicologia e educação: desafios teórico-práticos. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2000. p. 105-142. [ Links ]

TAROZZI, Massimiliano. O que é a Grounded Theory?: metodologia de pesquisa e de teoria fundamentada dos dados. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2011. [ Links ]

1- Part of this paper was presented during the XII Encuentro Iberoamericano de Educación, in the University of Alcalá, at Alcalá de Hernanes, Spain, in November 2017.

3 - The research complies with all ethical and confidentiality procedures towards participants, according to the guidelines of the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP). The project and the final report were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Science, Literature, and Languages - UNESP – Araraquara campus.

4- It was not possible to build a cloud in English as it would not feasible to translate the large amount of research data. However, in order to make it easy for the reader, the highlighted the most frequent words are referred to in brackets or footnotes. Some frequent words: lack, family, familiar, support, stimulation, incentive, interest, disinterest, commitment participation, disruption, problems and monitoring.

5- Some frequent words: lack, interest, disinterest, immaturity, lag, problems, attention, emotional, indiscipline students, apathy, concentration, and content.

6- Some frequent words: lack, lag, students, contents, didactic material, difficulties, requirements, system, literacy, knowledge, resource and learning.

Received: February 22, 2019; Revised: June 04, 2019; Accepted: August 14, 2019

texto em

texto em