Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 17-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046224676

SECTION ARTICLES

National Territorialization of Rural Education: Historical landmarks in Southeast Pará *

1- Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará, Marabá, PA, Brasil. Contacts: evandromedeiros1973@gmail.com; gs.moreno1@gmail.com.

2- Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil. Contact: socorroxbatista@gmail.com.

This article discusses the national territorialization of Education in Brazilian rural areas. The focus here is on the implementation of a Degree in Rural Education (LEDoC), especially in Federal Institutions of Superior Education (IFES). This paper is looking for the understanding of the national policy of expansion and territorialization of these courses by reflecting on actions and implementation of programs in this kind of Education from the protagonism of social movements and the national territorialization of the Teaching Degree in Rural Education (LEDoC). The privileged source of research is the Superior Education Census, published in 2017 by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP). The process of constitution of actions and programs in Education in rural areas was historicized, highlighting the effects of the national policy of expansion of LEDoC in Southeast Pará, where the first Brazilian Faculty of Rural Education, linked to the Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará (UNIFESSPA), was created. Nationally, this faculty has the largest number of students enrolled in the course. Data from 40 courses, run by 27 Federal Institutions of Superior Education (IFES), distributed between capitals and cities in the interior of 17 Brazilian states, plus the Federal District, had been analyzed.

Key words: Rural Education; Public policies; Training of educators

O artigo aborda a territorialização nacional da Educação do Campo no Brasil com foco na implementação dos cursos de Licenciatura em Educação do Campo (LEDoC), em especial nas Instituições Federais de Ensino Superior (IFES). Buscou-se compreender a política nacional de expansão e territorialização desses cursos, refletindo acerca de ações e implementação de programas em Educação do Campo desde o protagonismo dos movimentos sociais e da territorialização nacional dos cursos de Licenciatura em Educação do Campo (LEDoC). A fonte privilegiada da pesquisa é o Censo da Educação Superior, publicado em 2017 pelo Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais (INEP). Historicizou-se o processo de constituição das ações e programas em Educação do Campo, destacando-se os efeitos da política nacional de expansão da LEDoC no Sudeste do Pará, onde foi criada a primeira Faculdade de Educação do Campo do país, vinculada à Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará (UNIFESSPA) e que, nacionalmente, tem o maior número de alunos matriculados no curso. Foram analisados dados dos 40 cursos, executados por 27 Instituições Federais de Ensino Superior (IFES), distribuídos entre capitais e municípios do interior de 17 estados brasileiros, mais o Distrito Federal.

Palavras-Chave: Educação do campo; Políticas públicas; Formação de educadores

Introduction

This article has been elaborated in order to overcome contradictions caused by the use of data in recent publications and several Teaching Degrees in Rural Education that are at work in the country. The contradictions are manifested in the attempts of different authors to configure the national description of the course based on the Superior Education Census, published in 2017 by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP). The analysis of academic articles produced from such data allowed the verification of the use of different numbers to represent the same universe of LEDoC courses held within the same period. The characterization of LEDoC in these projects is always restricted to courses linked to the National Rural Education Program (PRONACAMPO), created through a Public Notice in 2012, which allowed the implementation of 40 courses, run by 27 Federal Institutions of Superior Education (IFES ). In some articles, the figures presented differ from this total.

There is also the omission of data regarding the LEDoC courses created in 2008 and 2009 by the Public Notices of the Support Program for Superior Education at Teaching in Rural Areas3 (PROCAMPO), which are in operation and offering continuous classes that are not linked to PRONACAMPO. In addition, these articles do not make explicit the existence of classes of the LEDoC course implemented in the Education on Correspondence modality and of courses created by HEI initiatives with their own resources and / or by the University Restructuring and Expansion Program (REUNI).

In this context, in addition to seeking to socialize data about the different forms of course offerings as a landmark of the national territorialization of the political-pedagogical network that shapes the Rural Education Movement, the present work also aims to present data about the LEDoC course, carried out since 2009 in southeastern Pará. Thus, it seeks to contribute to the systematization, analysis and reflection on the historical trajectory of the course and the achievements that are consolidated from its local implementation.

The article is organized in three sections. The first brings reflections on the emergence of the National Movement in Rural Education to consolidate the LEDoC course; the second deals with the policy of expanding LEDoC courses in Brazil; while the third presents the LEDoC course of the Faculty of Rural Education, at the Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará.

The national movement for Rural Education

The Rural Education Movement was born in the late 1990s during the First National Meeting of Agrarian Reform Educators (ENERA), held in Brasília, in July 1997. The event was the result of a partnership between the Working Group to Support Agrarian Reform at the University of Brasília (GT-RA / UnB), the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), represented by its Education Sector, in addition to the Fund provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Fund for Science and Culture (UNESCO) and the National Confederation of Bishops of Brazil (CNBB). Another important event that boosted the movement was organized by the National Articulation for Basic Education in the Countryside in Luziânia, Goiás, in July 1998 called the First National Conference for Basic Education in the Countryside.

These events affirmed the comprehension of the struggle for land and Agrarian Reform in a broader sense by integrating the struggle for the guarantee of right to education for peoples. The debate on Rural Education brought the discussion about historical contradictions arising from the agrarian issue in Brazil into the Education world. Nonetheless, these events also brought the advertisement of the countryside as a territory of possibilities in which different subjects daily build, in their own way, the knowledge and strategies of material and non-material production necessary for the maintenance of collective, family, community life, and as a territory of existences and social, cultural and political riches. The countryside as a territory for life, production, knowledge and cultures is expressed in a diversity of communities of family farmers, fishermen, indigenous people, quilombolas and also in the existence of small cities, whose social dynamics are not opposed to rural communities, but with it dialectically maintains inter-relationship, triggering processes of mutual cultural, political and economic influence.

It was argued that school education as an achievement conquered from the fights for rights cannot be for the people, but with and from the people in the countryside, where the pedagogical role and dialogue with the educators’ cultural knowledge and practices are assured. Students and peasant communities, considered a collective person-place of knowledge production. Something already foreseen in the pedagogical ruralism movement decades ago that the education that is exclusive to rural people should be as a means to fixate the rural to the rural person that goes beyond merely adapting the school to the need to educate rural workers and / or ensuring legal forms of curricular adaptation to contents and methodologies to local specificities.

In this regard, one of the main achievements of rural social movements in the late 1990s was the creation of the National Education Program on Agrarian Reform (PRONERA), the result of proposals made during the First National Meeting of Agrarian Reform Educators (ENERA). Created in April 1998, PRONERA, as a federal program, under the management of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), was proposed to be implemented by a wide interinstitutional articulation, which involves the State, universities and social movements, having a general objective to strengthen education in the settlements in order to stimulate, propose, create, develop and coordinate educational projects, using specific methodologies for the countryside ( SILVA, 2006 , p. 86).

The proposition and execution of course projects via PRONERA reinvigorated the partnership that had allowed the making of ENERA and the National Conference on Basic Education in rural areas. By doing this, it has strengthened and expanded the relationship between social movements in the countryside, at universities, in non-governmental organizations and in progressive religious sectors. Thus, inaugurating a national network of pedagogical initiatives at different levels of education and educational modalities that would inspire the creation of other actions of Education in rural areas and programs across the country.

An important characteristic in the process of constituting the Movement of Rural Education is how the different educational practices are articulated and making different “political and learning networks” resulting in a conceptual basis for the practice from the experiences that had been developed in school education and non-school. ( SILVA, 2009 , p. 144).

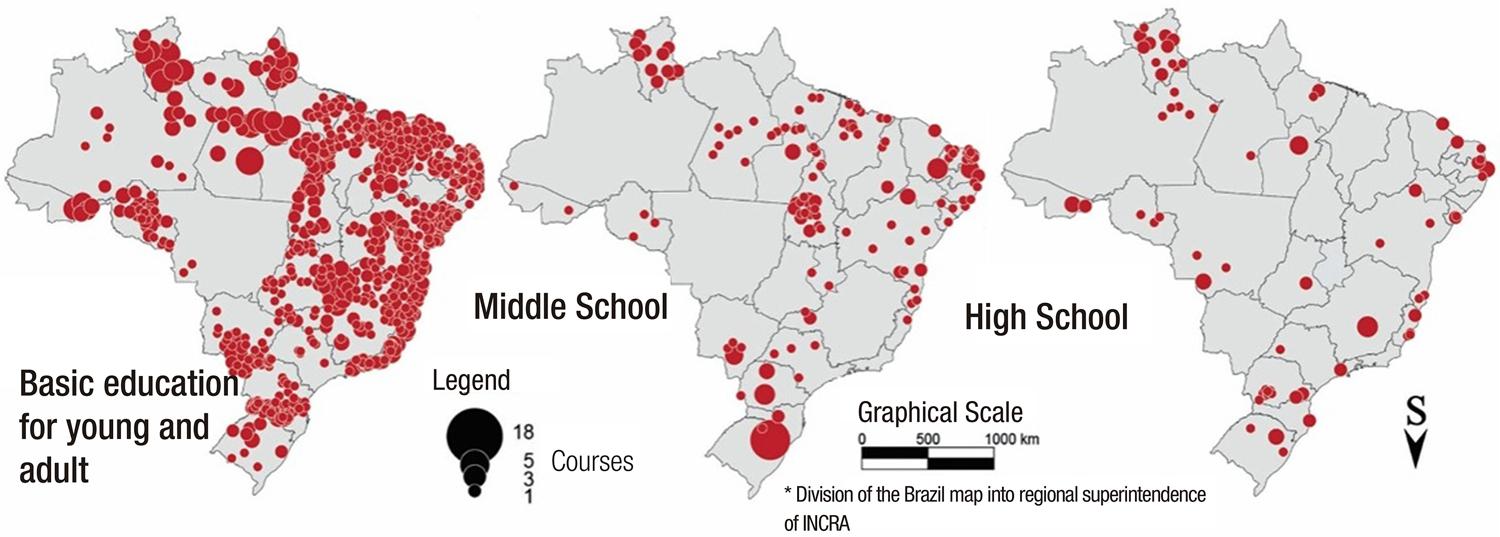

The execution of PRONERA fostered the constitution of a “national network for the realization of courses” (IPEA, 2015), leading to a closer relationship between rural social movements and universities, which would act as partner institutions proposing the projects. From 1998 to 2011, PRONERA promoted 320 courses in the country, 167 of which were by EJA (Youth and Adult Education), 99 of secondary education and 54 of superior education. The project involved 13,276 educators, 82 educational institutions, 38 demanding organizations and 244 partners and it was able to assist 164,894 students (154,192 of whom through EJA), 7,379 students were in high school and 3,323 graduated from superior education (IPEA, 2015).

Source: IPEA, 2015.

Figure 1 Municipalities where PRONERA courses are held by degree level (1998-2011)

As an organized civil society, social movements in the countryside began to lead the development and implementation of educational projects at different levels and modalities with universities through PRONERA. These movements triggered the national territorialization of Rural Education and the movement that constitutes it, which soon after established itself as a powerful political network of dialogue with the State and the formulation of proposals for transforming Rural Education into a public policy.

Between 2004 and 2010 academic and pedagogical events focused on the debate on Rural Education multiplied in municipalities, states and in the nation. Among these, the State Rural Education Seminars organized by the partnership between universities, social movements and the General Coordination of Rural Education (SECAD / MEC), which aimed to discuss and raise proposals for the bases of a public policy on Rural Education in Brazil, drew more attention than the others. In the same period, the creation of the General Coordination of Rural Education within the scope of the Secretariat for Education, Continued, Literacy and Diversity (SECAD / MEC) are expressions of the achievements of the processes and debates carried out by the National Movement of Rural Education in 2004, and the elaboration and approval of the Operational Guidelines for Basic Education in Rural Schools (Resolution CNE / CEB nº 1, of April 3, 2002), which presupposes the responsibility of the education systems in relation to the provision of schooling to subjects of the countryside from the perspective of law; respect for differences and diversity as a strategy for an equality policy; and the practical routing of measures to adapt the school to the life and demands of rural people.

The creation of the National Commission for Rural Education, within the Ministry of Education (Ordinance 1258, December 19, 2007) is also a reflection of the achievements of the National Movement for Rural Education through the establishment of spaces for dialogue and influence on public policies.

During two years, the rural education movement gained effective national capillarity of a process to build proposals for public policies, government programs, etc., in an interaction between the three spheres of the State and the organizations and social movements of the countryside located in the states and municipalities. ( MUNARIM, 2008 , p. 12).

However, the consolidation of the figure of a national collective subject that is represented in institutional relations and policies before the State and which defend proposals for the elaboration and implementation of a public policy in Rural Education was only achieved through the National Forum of Rural Education (FONEC), in 2010 by the rearticulation and expansion of the front involved in the National Articulation for Rural Education.

[FONEC has as objective] the exercise of constant, severe and independent critical analysis about public policies of Rural Education; as well as the corresponding political action considering the implantation, consolidation and, even, the elaboration of public policy proposals for this type of Education. (FONEC, 2010, p. 1).

To meet the demands of rural social movements for the expansion of governmental actions in Rural Education, the General Coordination of Rural Education (SECAD / MEC) created programs inspired by the experiences of PRONERA, such as the Saberes da Terra Program (2005) and the Full Degree Courses in Rural Education (2008), both serving the rural population widely and not only beneficiaries of the agrarian reform, as it is the case of PRONERA. The first, Saberes da Terra - National Youth and Adult Education Program for Farmers or Family Members integrated with Social and Professional Qualification aims to provide comprehensive training, primarily to young people in the countryside, by increasing their education focusing the completion of elementary school ( BRASIL, 2005 , p. 10). LEDoC, on the other hand, aimed at training teachers at a higher level, qualified by area of knowledge to work in the final years of elementary school and high school and in the management of school and community educational processes.

Through the pressure and demands presented to the State by social movements, a Decree No. 7,352 / 2010 has been achieved and instituted the National Policy for Rural Education ( MOLINA; HAGE, 2016 , p. 804) from 2012 on. As a result, the degree courses in Rural Education - LEDoC began to be implemented within the scope of the Support Program for Superior Education at Teaching in Rural Education (PROCAMPO). In other words, this constitutes a policy for educating educators.

The Teaching Degree in Rural Education – LEDoC

The creation of the Teaching Degree in Rural Education (LEDoC) in 2003 is part of a broader action by the Ministry of Education (MEC) to promote the National Rural Education Policy. This policy had been formulated by the Secretariat for Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion (SECADI) until the year 2018, through the General Coordination of Rural Education (CGED) and the Permanent Working Group on Rural Education (GPT).

In general, the proposal to create LEDoC aims at academically and professionally qualifying teachers to work in basic education at schools in the countryside so that will, in turn, guarantee educational training for rural populations across the country: family farmers, extractivists, artisanal fishermen, riverside populations, people settled and encamped by the agrarian reform, rural-waged workers, quilombolas, caiçaras, indigenous people, caboclos and others who make their living from working in rural areas. The term school in the countryside is that one located in a rural area, as defined by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), or one located in an urban area, as long as it predominantly serves rural populations ( BRASIL, 2010 ).

The first LEDoC class, considered a project class and installed via a partnership between the Faculty of Education at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (FaE / UFMG), MST, INCRA and PRONERA, was offered by the Federal University of Minas Gerais in 2005. Later in 2008, UFMG offered another class, through the 2008 SECAD / MEC Notice, cited below. As of 2009, the course was considered regular and received the support of REUNI to structure its topics of studies, offering 35 student’s vacancies annually. According to data from INEP (2017), the course is still in operation and in 2017 had 169 students enrolled among freshmen and graduates (INEP, 2017).

Through SECADI, the institution MEC created a Support Program for Superior Education in Rural Education (PROCAMPO) in 2007, whose main objective was to support the implementation of regular LEDoC courses in HEIs across the country and aiming to promote the training of teachers by area of knowledge to work in the final years of elementary school, high school and management of pedagogical processes in schools in the countryside. This program led to the elaboration of two public notices (SECAD / MEC / 2008 and SECAD / MEC / 2009), calling upon Superior Education Institutions (HEIs) to offer formal LEDoC courses, which resulted in the creation of 31 new courses in 2008 and 2009.

Of the institutions mentioned in Table 1 , some continued to offer LEDoC courses until 2017, including: Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Pampulha campus with 169 students enrolled, Regional University of Cariri (URCA), Crato campus with 38 students. It should be noted that the mentioned institutions offer a regular LEDoC course which started in 2009 via the PROCAMPO notice and had the support of REUNI to ensure the structuring of the personnel to work on the faculty. The Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Sumé campus, created LEDoC in 2009 through REUNI, and had 102 students enrolled in 2017 (INEP, 2017).

Table 1 Higher Education Institutions that offered a Degree in Rural Education, from public notices in 2008 and 2009 - SECADI / MEC - PROCAMPO

| Region | University | States |

|---|---|---|

| Midwest | UNB | Federal District |

| Northeast | UFS, UFPI, UNEB, UFBA, UECE, URCA UFPE, AESET, UNIVASP, CESA, UFMA, IFMA, UFCG, UNEAL | Sergipe, Piauí, Bahia, Ceará, Pernambuco, Maranhão, Paraíba e Alagoas |

| North | UFPA, IFPA, UNIR, UNIFAP, UFRR | Pará, Rondônia, Amapá e Roraima |

| Southeast | ISES, UFES, UNIMONTES, UFMG, UFVJM, INFNET, UNITAU | Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo |

| South | UNICENTRO, UNIOESTE, UFTPR, UFSC | Paraná e Santa Catarina |

Source: SECAD, 2012

Thus, in 2010, Decree No. 7,352, of November 4, 2010, which instituted the National Rural Education Policy was published, which to a certain extent led to the review of PROCAMPO and the creation of the National Rural Education Program. (PRONACAMPO), whose objective was to offer financial and technical support for the viability of policies in the countryside. The implementation of PRONACAMPO, in turn, made it possible to publish SECADI / MEC Public Notice 02/2012, which resulted in the selection of 44 LEDoC course proposals, even though four Superior Education Institutions contemplated by this notice (HEIs) - UFPB, IFMT (Vicente da Serra Campus), IFMG (Norte de Minas), IFSC (Canoinhas Campus) - did not implement the course.

The Notices performed in 2008 and 2009 did not contemplate the continuity of the LEDoC course offerings, therefore, many of the HEIs mentioned above that were participating authorized only one class for the course, whereas there are institutions that continued to offer the course to the present day. The 2012 Public Notice, on the contrary, foresaw the continuity of the course with financial support over three years and within a perspective of a structural policy for training the educators. PRONACAMPO also made available 600 permanent vacancies for teachers and 126 technicians for executing institutions of LEDOC program, hoping to formally train 15 thousand teachers to work in Basic Education in the first three years of the course, in schools in the countryside.

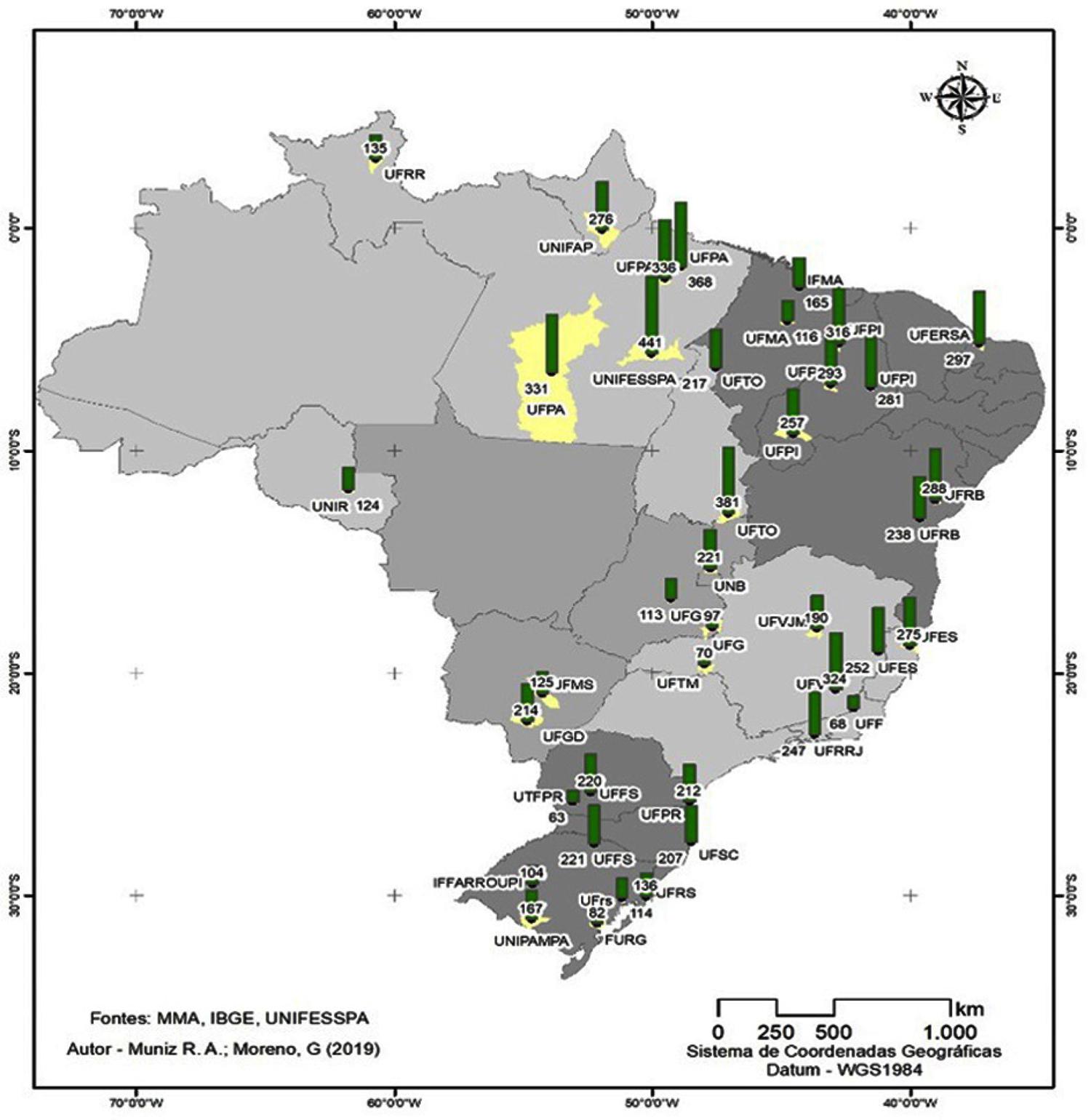

It can be said that there was a consolidation of the national expansion / territorialization of LEDoC courses through PRONACAMPO. There were the implementation of 40 courses, run by 27 Federal Superior Education Institutions (IFES), distributed between capitals and cities inland of 17 Brazilian states, plus the Federal District (INEP, 2017), reaching all five regions of the country.

Table 2 National Distribution of IFES offering LEDoC via PRONACAMPO (Notice 02/2012, SECADI / MEC)

| Region | Universities | States |

|---|---|---|

| Midwest | UNB, UFG, UFMS e UFGD | Federal District, Goiás, Mato Grosso do Sul |

| Northeast | UFPI, UFRB, IFMA, UFMA e UFERSA | Piauí, Bahia, Maranhão, Rio Grande do Norte |

| North | UFPA, UNIR, UFRR, UNIFAP, UFT e UNIFESSPA | Pará, Rondônia, Amapá, Roraima e Tocantins |

| Southeast | UFF, UFES, UFRRJ, UFVJM, UFTM | Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo e Minas Gerais |

| South | UFRGS, FURG, UFSC, UTFPR, UNIPAMPA, UFFS e IFFarroupilha | Paraná, Santa Catarina e Rio Grande do Sul |

Source: Superior Education Census - INEP, 2017.

According to the Superior Education Census carried out by INEP, in 2017 there were 8,582 students enrolled in the LEDOC courses, including the remaining students from previous years, students in their last semester (only in the preparation phase of the Course Completion Work - thesis) and students who had enrolled in 2017. The highest concentration of enrollments (446 students) is in the Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará, located in the northern region of the country. This is the university that concentrates the largest number of students enrolled in LEDOC nationally (INEP, 2017).

Table 3 National Distribution of Students Enrolled in LEdoC

| Region | Students enrolled | % |

|---|---|---|

| Midwest | 770 | 9% |

| Northeast | 2251 | 26% |

| North | 2609 | 30% |

| Southeast | 1426 | 17% |

| South | 1526 | 18% |

| Total | 8582 | 100% |

Source: Superior Education Census - INEP, 2017.

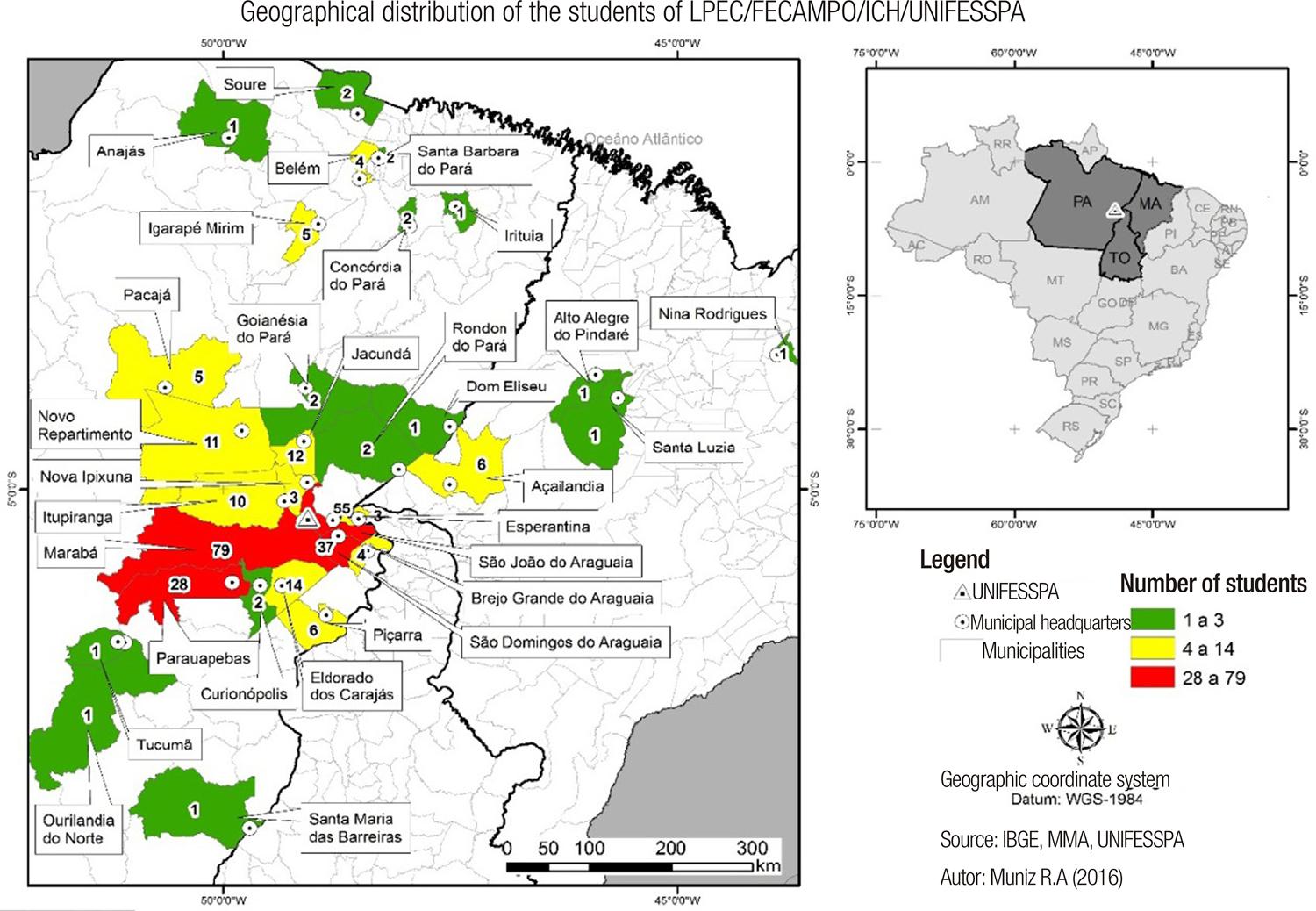

Source: MMA, IBGE, UNIFESSPA / Autor (MUNIZ, 2019).

Figure 2 National Distribution of Superior Education Institutions offering LEDoC

Moreover, according to INEP data (2017) in the Superior Education Census, there are LEDoC courses that function as Education on Correspondence modality. There are six courses operating in the state of Rio Grande do Sul at two different Superior Education Institutions (for more details see table 4 ).

Table 4 LEdoC courses functioning on correspondence

| Municipalities | Institutions | Number of students enrolled | Start year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seberi | UFSM | 28 | 2017 |

| Cerro Largo | UFSM | 38 | 2017 |

| São Sepé | UFSM | 30 | 2017 |

| Agudo | UFSM | 30 | 2017 |

| Itaqui | UFSM | 30 | 2017 |

| Sant´Ana do Livramento | UFPEL | 27 | 2009 |

Source: Superior Education Census - INEP, 2017.

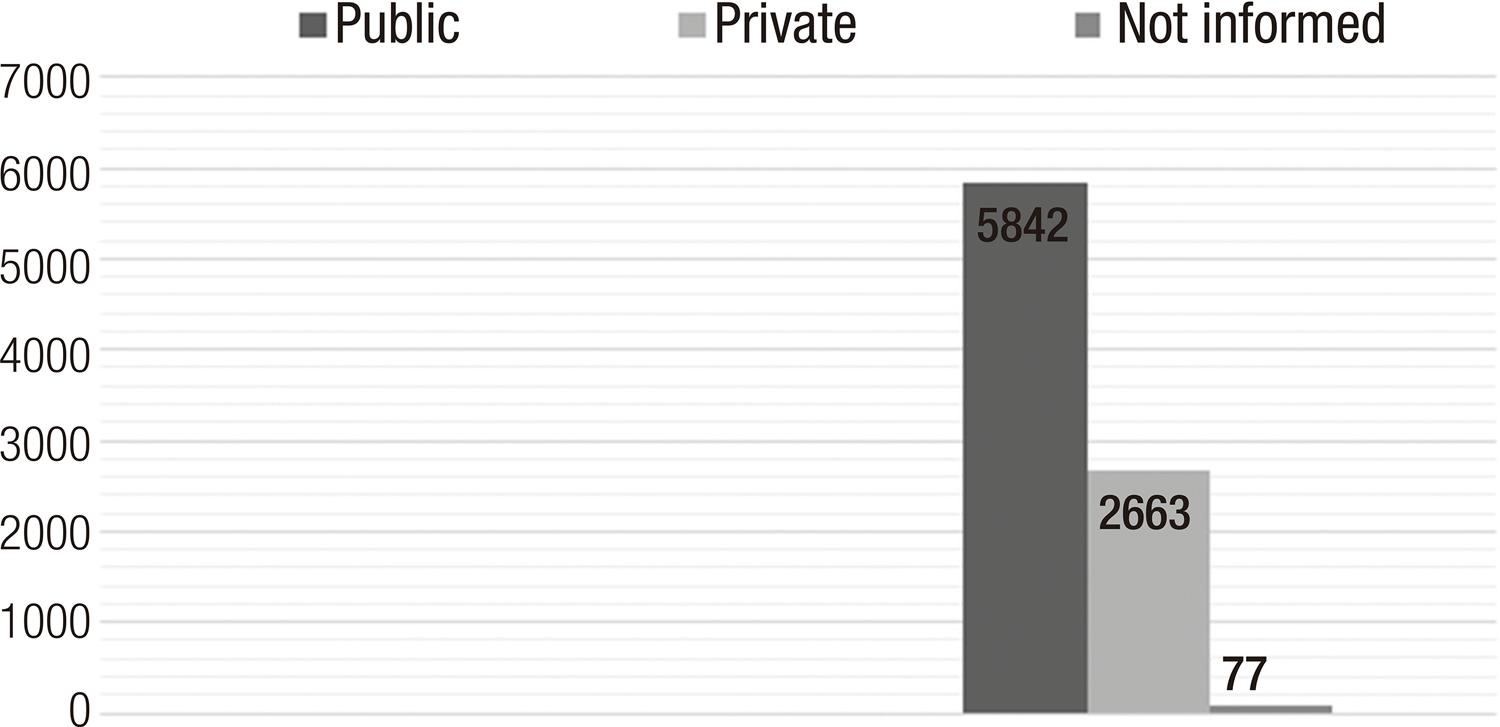

The origin of school education in High School for students who are enrolled in the 40 LEDoC courses in operation created by PRONACAMPO deserves to be cited as well. According to the data published by INEP (2017), it appears that of the total of 8,505 students in the courses, most come from public schools, 5,842 (55%), but there is an expressive number of students adding up to 2,663 (45%) students who come from private education.

The data presented may justify the reasons why LEDoC courses, in some universities, carry out a Special Selection Process (PSE) in two stages, in order to enroll the students.

The first is a test with 40 multiple-choice questions about general knowledge regarding high school syllabus content plus an essay, while the second stage is qualitative and includes face-to-face interviews in which the candidate’s relationship with the course is verified or also via the candidate’s descriptive memorial. This process is designed to avoid the entrance of students who have no connection with the countryside and / or who attended high school in a private school.

It can be said that to a certain extent the data in table 4 and in chart 1 contradict the concern and need for analysis and debate about the course offers according to baseline points for the execution of the objectives that originated them in the first place due to the scenario of massive expansion of LEDoC courses. Such data represent a reality that differs from that established by article 1 of Decree 7.352 / 2010, which provides for the Rural Education policy and the National Education Program in Agrarian Reform:

Source: Census of Higher Education - INEP, 2017.

Chart 1 LEDoC student’s origin – PRONACAMPO courses

Art. 1o The rural education policy is aimed at expanding and qualifying the offer of basic and superior education to rural populations, and will be developed by the Union in collaboration with the States, the Federal District and the Municipalities, in accordance with the guidelines and goals established in the National Education Plan and the provisions of this Decree.

§ 1o For the purposes of this Decree:

I - rural populations: family farmers, extractivists, artisanal fishermen, riverside dwellers, agrarian reform settlers and workers, rural wage workers, quilombolas, caiçaras, forest peoples, caboclos and others who produce their way of existence from working in rural areas; and

II - Rural school: one located in a rural area, as defined by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBGE, or one located in an urban area, as long as it predominantly serves rural populations. ( BRASIL, 2010 ).

Finally, by bringing together secretariats and bodies of municipal and state governments, constituting a fundamental element to the configuration and execution of public policies in education more consistent with the reality and guarantee of the social rights of the rural population, the national materialization of the regular offer of LEDoC courses further increased the political-pedagogical network of Rural Education involving universities, social movements and NGOs.

Thus, the materialization of LEDoC courses, nationally territorialized, helps to advance the affirmation of social policies that guarantee the universalization of rights as a fundamental element of the consolidation of the democratic State ( ROCHA, 2013 ) by enabling and guaranteeing the population of the countryside access to higher education, as the training of teachers to work in rural schools occurs according to the philosophical, political and pedagogical principles of Rural Education and considering the different subjects and the different ways of organizing life and struggles in the country.

The Teaching Degree in Rural Education in Southeast Pará

Regarding the origin of this Degree in Rural Education at the Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará (UNIFESSPA) and the teacher training proposal developed through it, it is necessary to understand the social context in which the history of the program is inserted, to recognize the importance in the process of the National Education Program in Agrarian Reform - PRONERA and to consider the role of the political-pedagogical network in Rural Education that is engendered with the execution in the region.

PRONERA was fundamental in the emergence and mobilization of the Political-Pedagogical Network in Education in the countryside of Pará. Nationally, among the higher education institutions with the largest number of available courses via PRONERA, in the period 1998-2011, the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) appears as the university with the largest number of projects (31 projects) carried out, followed by the Technical Institute for Training and Research on Agrarian Reform (ITERRA) in Rio Grande do Sul (18 courses); the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), (14 courses); and, the State University of Bahia - UNEB, and the Fundação Universidade do Tocantins – UNITINS, (10 courses each) (BRASIL, II Pnera, 2015, p. 46).

As for PRONERA courses held in Pará at UFPA, teacher training concentrates 32% while higher education and secondary level (teaching technician) both have 16%. With 20% of the total courses offered by the program in the state, the technical vocational courses in agriculture integrated with high school stands as second (BRASIL, II Pnera, 2015). Most of these projects were carried out in the South and Southeast of the state, one of the regions with the highest concentration of the population who received land by the agrarian reform in the north of Brazil.

The South and Southeast of Pará was the frontier to which between 1970 and 1990, large enterprises of livestock, mining and construction of hydroelectric plants established themselves. This region was considered by the military in power after the 1964 coup d’état as “land without men for landless men” and a region with great potential in natural resources that should be fully integrated into the national territory. Nonetheless, large waves of landless migrants also moved to the region. Over the years, the Eastern Amazon has become an immense scenario of territorial occupation marked by a history of destruction, but also one of resistance, rebellion, protest and dreams in the midst of the fight for land ( MARTINS, 1996 ).

According to INCRA (2018), Brazil has 9,478 land reform settlement projects, totalizing 1,349,689 settled families. Pará state alone concentrates 308,173 of these families (22.8%), of which 99,256 families are in 515 settlements in the South and Southeast of the state (INCRA, 2018).

The PRONERA projects were designed to serve the population in the microregion of Marabá and its surrounding municipalities, who were being benefited from the agrarian reform policy. Initially, the project was proposed by University Campus of Marabá at UFPA, which later in 2013 became the headquarters of Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará.

From 1998 through 2011, the projects executed via PRONERA by the University Campus of Marabá – UFPA were the following: Literacy of Youth and Adults (1999-2000); Schooling of Literacy Monitors in the course of raising the basic education level with Elementary School, 5th to 8th grades (1999-2000); teacher training with a high school teaching course (2001-2004); increase in School level for Youth and Adult Education, early years of Elementary School (2003-2006); two classes of Technical-Professional High School degree in Agriculture with Emphasis in Agroecology (2003-2007 and 2005-2009); Academic Education in Superior Education, with an undergraduate degree in Agronomy (2003-2009), an undergraduate course in Letters (2005-2011), an undergraduate degree in Pedagogy (2005-2011) and a specialization degree in peasant family farming and Rural Education - Agrarian Residence (2005-2007). These are projects related to basic education and superior education carried out through a partnership between the University and the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), the Federation of Agricultural Workers (FETAGRI), the Agricultural Family School of Marabá (EFA) and the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT).

The Regional Education Forum of Campo do Sul and Southeast of Pará (FREC), an entity composed of social movements, NGOs, universities, municipal education departments and governmental bodies related to environmental and agronomic issues, was born amid the experiences of PRONERA projects with a tradition of combining and creating a network to strengthen social struggles that will expand access to rights. The forum’s existence materialized through the formation of a general coordination composed of university professors and members of social movements; the activities from working groups focused on thematic discussions involving education and agrarian and environmental issues; general plenary meetings to debate emerging agendas on the same themes; and in the biennial annual regional conferences of Rural Education - like events held with the participation of representatives of social movements, municipal education networks, universities and FREC partner entities.

In 2008, UFPA was invited by the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC) to participate in the first call for bachelor’s degree in Rural Education. In the midst of the experiences engendered via PRONERA, two occurrences were fundamental for the constitution and maturation of the course proposal originally presented as Full Degree in Rural Education (LPEC) by Southeast Pará institutions. The first occurrence was the experience in basic education and the Pedagogy of Alternation experienced through the first two classes of the Technical and Professional High School Course in Agriculture with an Emphasis in Agroecology, which had been developed with the Agricultural Family School of Marabá (EFA) and the Federation of Agricultural Workers of Pará (FETAGRI) and coordinated by teachers from the collegiate courses of Pedagogy and Agronomy, at the University Campus of Marabá (UFPA). This experience was important for the configuration of the LPEC not only in relation to the learning derived from pedagogical-curricular praxis with elementary and high school that was developed through Pedagogy of Alternation, but mainly regarding its realization through a political-pedagogical network involving social movements, universities, NGOs and government agencies and bodies. By expanding our perspective, this network materialized the creation and functioning of the Regional Education Forum of Campo do Sul and Southeast of Pará (FREC) in the region and constituted the second determinant occurrence for the elaboration of the proposal, creation of the course and composition of the teaching staff at LPEC and what later became the Faculty of Rural Education.

The course proposal was prepared by an interdisciplinary team that included forum members and university professors, especially those who had served as educators and coordinators of the projects carried out via PRONERA. Later, the course proposal was presented to FREC and, in 2008, submitted to and approved by the higher levels of UFPA as a regular course of the permanent offer framework of the University Campus of Marabá – UFPA.

Initially, the Degree Course in Rural Education of Marabá Campus began to be implemented in 2009, with a team of collaborating professors from the Faculties involved in the development of projects linked to PRONERA such as Agronomy, Pedagogy and Letters.

In the same year, through Decree No. 6.096 / 2007 and the articulation and dialogue of FREC, claiming vacancies from the university administration for the course, the UFPA rectory included the LEDoC course in the Program to Support Federal University Restructuring and Expansion Plans (REUNI), created by the Ministry of Education (MEC). REUNI aimed to promote the expansion for superior education, expanding the number of places for students and promoting competitions for teachers. The university professors involved with the new course publicly criticized REUNI by claiming that the program proposed access expansion without ensuring the expansion of resources which would, in turn, ensure the proper and consistent maintenance of the student-year cost and the infrastructure of universities. However, members of social movements, through a forum debate, argued that there were elements of reality that suggested the urgent need to ensure the training of Basic Education teachers to meet the demands of schools in rural communities in the region.

From the point of view of our regional reality, when looking at the situation of education in the countryside, the asymmetries are intensified, since rural schools registered in the last INEP census (2009), only 3% of schools from 1st to 5th grade had teachers with superior education and / or degrees, in relation to high school 45% of schools have teachers with superior education and / or degrees, reinforcing the immense demand for the education of rural educators. (…) training teachers-educators able to work in these schools, given the absence of minimally trained professionals. (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 5).

The decision to join REUNI was also influenced by the consideration of forum members in seeking alternatives to continue the historical process of development of Rural Education in the region. Through REUNI, the first public tender vacancies were guaranteed to train the staff of permanent teachers in the Degree Course in Rural Education at the Marabá Campus, which along with the Pedagogy Course became part of the Faculty of Education.

Through Law No. 12,824 / in 2013 amidst the federal policy of expansion for superior education, the Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará (UNIFESSPA) was created from the dissolution of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). As a result of this process, the Faculty of Rural Education (FECAMPO) was developed through the evaluation and strategic decision carried out by the Professors of Rural Education. In addition to the Degree in Rural Education, the faculty started to house two classes of specialization courses in Rural Education and Curriculum and Rural Education and Agroecology , both linked to the Agrarian Residency Program (PRONERA / INCRA / MDA).

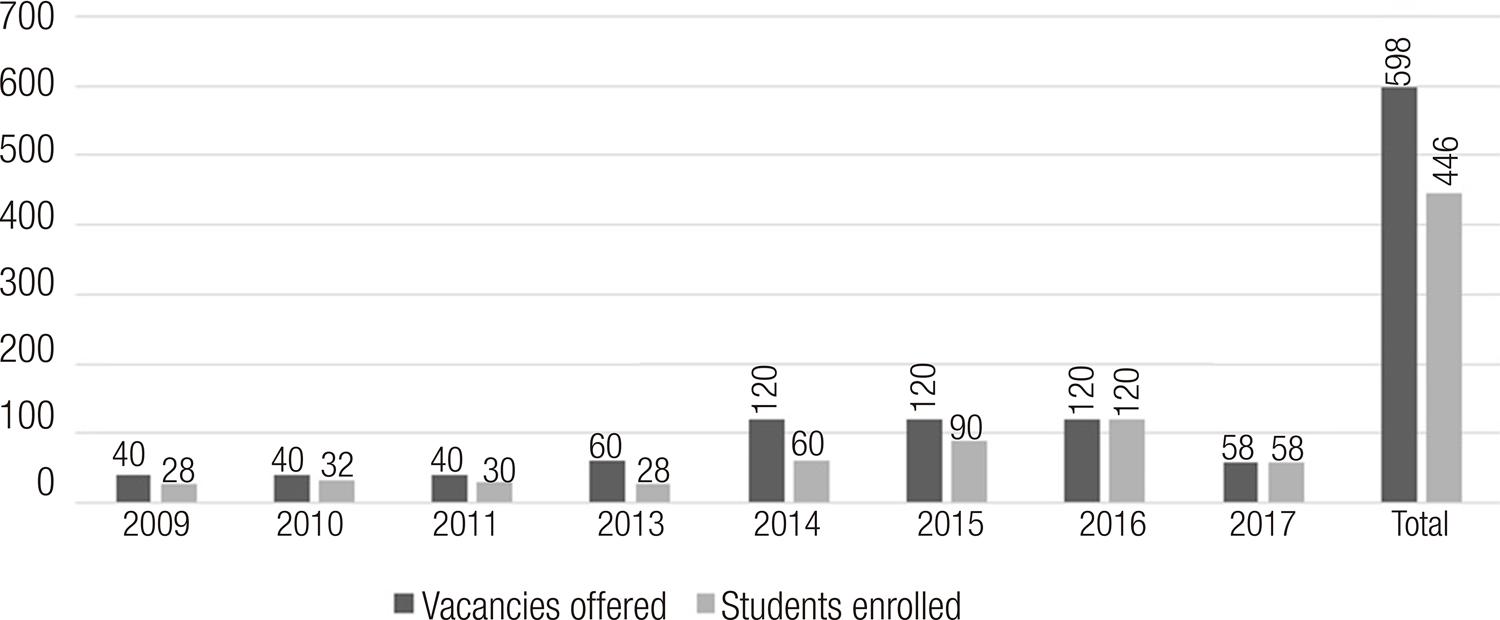

That same year, UNIFESSPA adhered to the public notice of the Support Program for Superior Education in Rural Education (PROCAMPO), thus the Degree in Rural Education of FECAMPO started to perform a selective process three years in a row to select 120 students to join the classes (2014, 2015 and 2016). The resources from the program helped to guarantee accommodation, educational material and food for students in these classes until January and February of 2017.

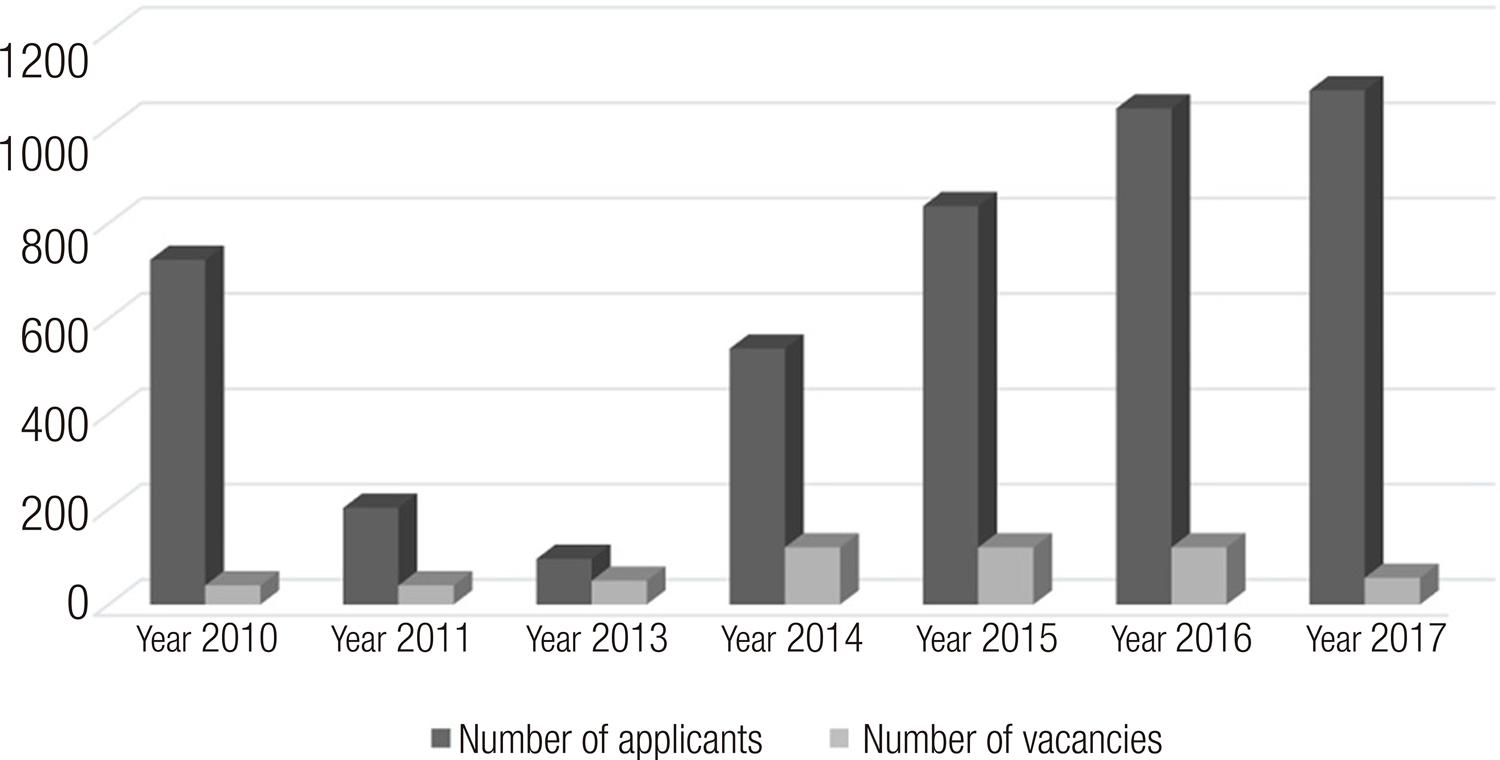

The way students were admitted to the UNIFESSPA LEDoC course has been carried out since 2009 via the Special Selection Process (PSE), which took place in two stages, the first is a test with forty multiple-choice questions about general knowledge regarding high school syllabus plus an essay; and the second stage is qualitative and includes face-to-face interviews in which the relationship between the student and the course is verified. Between 2009 and 2015, the LEDoC UNIFESSPA PSE was coordinated by the Center for Selective Processes (CEPS), an organ belonging to the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). As of 2016, the selection process started to be coordinated by the course Professors themselves, with the process planned and executed under the responsibility of an interdisciplinary committee. It is possible to observe the demand for applicants in the PSE LEDOC in the period from 2010 to 2017 in the chart below.

Annually, the course has the possibility to offer up to 60 vacancies respecting the institution’s graduation regulations. Exceptionally, between 2014 and 2016, 120 vacancies were offered to attend the PROCAMPO public notice (Notice nº 02/2012), which envisaged the entry of 120 students per year over three years (see chart 2 ). As the course had already been institutionalized since 2009, the UNIFESSPA resumed the selection process (with 60 places) for the admission of students in 2017.

The course held in southeastern Pará serves students from rural communities in different municipalities in Pará and in the state of Maranhão. Among them are the municipalities located very far from the headquarters of the course, such as Belém, Irituia, Santa Barbara do Pará, Concordia do Pará and Igarapé Mirim, in the northeast of the state, and Soure and Anajás (located more than 500km away from Marabá), of the Marajó Mesoregion.

The FECAMPO / UNIFESSPA Teaching Degree in Rural Education is structured in four areas of knowledge, by exercising the search for interdisciplinarity as principles for the training of students and assuming interdisciplinarity as the foundation of its curricular proposal. The four specific areas are Human and Social Sciences (CHS), Agrarian and Nature Sciences (CAN); Letters and Languages (LL) and Mathematics (MAT), with Geography, History and Sociology as reference subjects. As for Human and Social Sciences knowledge area; Physics, Chemistry and Biology, for Agricultural and Nature Sciences; Portuguese, Literature and Writing, for Letters and Languages and Mathematics for the area of Mathematics. Thus, aiming that students are able to work on the contents and build a curriculum that covers the 3rd and 4th Cycles of Elementary and Secondary Education (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 5).

Therefore, the curricular organization of the course seeks to account for “contemplating all areas of knowledge provided for multidisciplinary teaching, ensuring basic studies of each discipline for all students”, in accordance with the requirements of SECADI / MEC Notices. (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 21). Similarly, the academic formation:

[...] it is done through study centers that try to contemplate and articulate these teaching pillars, [...] so that student-educators can experience in their studies the methodological logic for which they are being prepared. (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 20).

The academic formation is articulated between face-to-face activities (Time in School) characterized as a moment of theoretical studies and debates, and non-face-to-face activities (Time in community) marked by field research, independent studies and pedagogical practices planned collectively, and carried out by students when they return to their communities. The organization of the pedagogical process alternating on time-space between school and community aims to guarantee teacher training with “emphasis on research, as a process developed throughout the course and integrating other curricular components, culminating in the elaboration of a monographic work with public defense” and to ensure the field of curricular internships that include experiences of professional practice (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 20).

The academic formation triggered by this process tries to foster theoretical-methodological learning and a teaching posture guided by:

[...] necessary dialectics between education and experience, ensuring intellectual rigor and valorization of the knowledge already produced by educators (peasants) in their educational practices and in their socio-cultural experiences (sic) in a balance manner (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 20).

Rural Education initiatives in southeastern Pará makes it clear how the development of the PRONERA and LEDoC projects was not only a transformational process for the university itself with the creation of new courses and new institutional structures, but also a way to ensure the right of access to superior education for people living in rural areas. In the case of UNIFESSPA, the creation of the Faculty of Rural Education.

In addition to the creation of LEDoC at the University Campus of Marabá (UFPA), the political-pedagogical network constituted through the Regional Education Forum of Campo do Sul and Southeast of Pará (FREC) was also responsible for the mobilization and debates that resulted in the creation of the Rural Campus of Marabá in the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Pará (CRMB-IFPA), created in 2007 and installed within the Agrarian Reform Settlement “26 de Março”, linked to the Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST). CRMB-IFPA (also linked to PROCAMPO) would offer the LEDoC course as well (Publications SECAD / MEC / 2008 and SECAD / MEC / 2009).

Inspired by the curricular pedagogical project and the experience of the course held in the Faculty of Rural Education (FECAMPO-UNIFESSPA) in Marabá, other LEDoC classes were created on the campus at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) in different municipalities. These classes also became a permanent part of the university’s courses and were the basis for the creation of new Rural Education Faculties at UFPA: The Faculty of Rural Education in Cametá Campus (2013) and the Faculty of Rural Education in Abaetetuba Campus (2017).

Conclusion

The actions triggered by the political-pedagogical network constituted by the Rural Education Movement and the creation and consolidation of the territorialization of LEDoC courses in Brazil and Pará, more than just discussing about the right to education, made possible the debate and expansion of the concept of law and education, the promotion of reinvented public policies and government programs according to the perspective and demands of rural populations.

These transformations affect the definitions of the role of school and school education, so that these are perceived as a person-space collective committed to the construction of knowledge that aims to understand and transform reality and that is open to social changes and able to accompany it by joining universal knowledge and local knowledge. At the same time, considering the students’ life experiences and investing in them to become critical, creative and supportive people. (UNIFESSPA, 2014, p. 13).

These transformations also reach the Professors. In southeastern Pará, this process manifests itself as an outcome of the time in community, when university Professors aiming to better understand the socio-environmental reality, the peasant culture and agrarian issues in the region, visit peasant communities and families and do the pedagogical monitoring of the activities carried out by students. This is a process that certainly contributes to the continuous training of the teachers, the movement ‘make school education happen’ and the fight for land, by and for teaching praxis. As a result, it can be seen the enrichment and deepening of the theoretical understanding of social reality, the requalification and expansion of pedagogical knowledge in education and in school, and constant improvement of professor’s jobs, which is fundamental for these professionals who help to qualify teachers.

On the other hand, the process of massive expansion of the offer of Teaching Degree Courses in Rural Education and institutionalization of actions in Rural Education, through its inclusion in the structure of the state and municipal education departments, has arisen concern to universities and social movements about how to ensure and consolidate the pedagogical, epistemic and academic achievements already achieved without losing their original political identity and distancing themselves from the fight for land and extinguishing the protagonism of social movements in the countryside.

Through verifying the existence of LEDoC classes in Education on Correspondence modality, based on the analysis of the Superior Education Census (INEP, 2017), it inevitably leads to questions about their proposals, activities and pedagogical practices, especially in what refers to the pedagogical alternation (time spent in community and time spend in school) that takes place in LEDoC courses not covered by this modality. Originally, the degree aims to promote a formation that is based on research and study of memory, knowledge, values, customs, as well as social and productive practices of the subjects in the countryside and the different people working in this environment. By valuing the different knowledge of the rural people and communities as a possibility to produce knowledge together, which requires full presence both in communities and in the university.

Finally, research that can support the elaboration of reflections about the processes of institutionalization of Rural Education in the country is gaining importance due to the political moment that Brazil is going through, in which the historical achievements of the National Movement for Rural Education are at risk. Research focusing on historical realities, established strategies, advances and contradictions that mark the existence of the various pedagogical initiatives scattered throughout the country is important because they allow the analyzation of the formative processes that this institutionalization materializes and how these have been developed to ensure the people of the countryside not only the right to school, but also the affirmation of the condition of rural people as holders of rights, policies, pedagogic and knowledgeable, according to what is defended by the fight and principles of the National Movement for Rural Education.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7.352 , de 04 de dezembro de 2010. Dispõe sobre a política de Educação do Campo e o Programa Nacional de Educação na Reforma Agrária. Brasília: Imprensa Nacional, 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Saberes da Terra. Programa Nacional de Educação de Jovens e Adultos integrada com qualificação social e profissional para agricultores (as) familiares . Brasília: Imprensa Nacional, 2005. [ Links ]

FECAMPO. Faculdade de Educação do Campo. Relatório técnico de prestação de contas projeto de ensino: implantação do curso de licenciatura em Educação do Campo 2014 a 2016. Marabá: FECAMPO-UNIFESSPA, 2017. 103 p. Não publicado. [ Links ]

FONEC. Fórum Nacional de Educação do Campo. Carta de criação do Fórum Nacional de Educação do Campo . Brasília: [s. n.], 2010. [ Links ]

INCRA. Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. Números da reforma agrária . Brasília: Incra, 2018. Disponível em: http://www.incra.gov.br/reforma-agraria/questao-agraria/reforma-agraria. Acesso em: 24 abr. 2019. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo da educação superior: notas estatísticas - 2017. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2017. [ Links ]

IPEA. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Relatório da II pesquisa nacional sobre a educação na reforma agrária . Brasília: IPEA, 2015. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. Fronteira: a degradação do Outro nos confins do humano. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1996. [ Links ]

MOLINA, Mônica Castagna; HAGE, Salomão Mufarrej. Riscos e potencialidades na expansão dos cursos de licenciatura em educação do campo. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação , Goiânia, v. 32, n. 3, p. 805-828, set./dez. 2016. [ Links ]

MUNARIM, Antônio. Movimento nacional de educação do campo: uma trajetória em construção. In: REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ANPED, 31., 2008, Caxambu., Anais... Caxambu: ANPEd, 2008. GT3 – Movimentos Sociais E Educação. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Eliene Novaes. Das práticas educativas às políticas públicas: tramas e artimanhas pela educação do campo. 2013. Tese (Doutorado em educação) – Faculdade de Educação, da Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2013. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maria do Socorro. As práticas pedagógicas das escolas do campo: a escola na vida e a vida como escola. 2009. Tese (Doutorado em educação). Centro de Educação, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, 2009. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maria do Socorro. Da raiz à flor: produção pedagógica dos movimentos sociais e a escola do campo. In: MOLINA, Mônica Castagna (Org.). Educação do campo e pesquisa: questões para reflexão. Brasília: Nead, 2006. p. 66-93. [ Links ]

UNIFESSPA. Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará. Projeto pedagógico do curso licenciatura em educação do campo . Marabá: Unifesspa, 2012. [ Links ]

UNIFESSPA. Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará. Projeto pedagógico do curso licenciatura em educação do campo . Marabá: Unifesspa, 2014. [ Links ]

Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: August 15, 2019

texto em

texto em