Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 01-Set-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046219733

SECTION: ARTICLES

Curriculum and space – a conversation to be done?*

1 - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. Contacts: ana_angelita@ufrj.br; ricardoscofano@ufrj.br.

The following pages attempt a cartography (multiple, as inspired by Doreen Massey (2004) and Deleuze; Guattari (2011)), proposing to trace possible associations between curriculum and space. The intention of this paper is to check whether the spatialization of the relationship between curriculum and knowledge matters in the field of curriculum. Such objective implies a project of questioning a supposed universal knowledge without necessarily discarding the category of knowledge as a whole. For this reason, the argument, as from curriculum and geography thinkers, allows the perception of an encounter among epistemology, ontology, and space. However, our assumption is that the field of curriculum has devoted little to the spatial debate despite it being an emerging analytical category within its studies. Although there is a reading of space thinkers, we suspect that conversations have been banned. Nevertheless, our reading allows envisioning a convergence that seems to point space as an ontological category of curriculum. Such movements were triggered by a question that leads the text to its unfolding: what can the combination of curriculum and space do?

Key words: Theories of curriculum; Space; Knowledge

As páginas a seguir ensaiam uma cartografia (múltipla, nas inspirações de Doreen Massey (2004) e Deleuze; Guattari (2011)) propondo traçar possíveis associações entre currículo e espaço. A intenção deste artigo é especular que, ao campo curricular, importa o ato de espacializar a relação entre currículo e conhecimento. Tal objetivo implica um projeto de interrogar um pretenso conhecimento universal, sem que, necessariamente, a categoria conhecimento seja desprezada como um todo. Por esse motivo, a argumentação, a partir de teóricos do currículo e da geografia, permite perceber um encontro entre a epistemologia, a ontologia e o espaço. Contudo, nossa hipótese é a de que o campo curricular pouco se dedica ao debate espacial, ainda que seja uma categoria analítica emergente nos seus estudos. Embora haja uma leitura de teóricos do espaço, suspeitamos que tenham sido conversas interditadas. Não obstante, nossa leitura permite vislumbrar uma convergência que parece indicar o espaço como uma categoria ontológica do currículo. Tais movimentos foram disparados por uma pergunta que guia o texto em seus desdobramentos: o que pode a composição currículo e espaço?

Palavras-Chave: Teorias de currículo; Espaço; Conhecimento

Introduction

The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space.

Michel Foucault (2001, p. 411).

In 2002, Alfredo Veiga-Neto borrowed Foucault´s diagnosis (presented at Other spaces conference, Berlin, 1967) and turned it into an epigraph, a subject of discussion of a most recent work on curriculum theory. With the title About geometries, curriculum and differences, Alfredo Veiga-Neto wrote perhaps the most geographical text on curriculum interpretation (or theory), inviting interlocutions from geographers, like David Harvey and Edward Soja. From our point of view, that work – by encouraging Foucault´s spatial reading – made way for a discussion to be done: the relationship between space and curriculum.

A conversation to be done since we suspect that the field has already dedicated hard-hitting debates about curriculum and time, and the interconnection between curriculum and culture. Just like Veiga-Neto in 2002, agreeing with the Foucault from the 1967s, we reaffirm the proposition that it is time to think about space. In this regard, our intention passes through the problematization of curriculum thinking to, in our point of view, probe the potentialities of space being thought as an ontological category of curriculum.

In the course of this paper, we will see the dense interface that lies between curriculum and knowledge as an adjacent topic. From the start, we understand that questions such as – Know what? Know how? Or what should be that which is, commonly, called knowledge, and sometimes, reified as a common base? – are triggers that may initially arise the curiosity of our readers. Our writing suspects that among those questions crossed by curriculum purposes there is a space-time implication.

In line with this suspicion, we envisage cartography (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 2011; RANNIERY, 2012) as a non-metrical, not quantitative investigative path that allows us to draw with more nuances the intense space that we intend to work with. In other words, cartography as a research method manages evidences of different power fields (geography, philosophy, education), generators of multiple relationships that may contribute to point to the inter-relational character of space – space is more than a mere surface where stories unfold. Therefore, our suspicion of space as an ontological category is due to curriculum cartography.

For the interests of this paper, our argument is developed in two parts. We then begin with a question Curriculum, knowledge, and space: a powerful combination?, developed on a section which questions the place of space within curriculum theories. This section, based on a panel about the proposition curriculum-space-knowledge, implies that the repositioning of this debate passes through a review of knowledge characterization. For that reason, it seems to us a dear strategy to establish dialogues with post-structuralist tendency thinkers to read the relationship between space and power, present in Foucault, for example.

In the second section, Knowledge-transport and knowledge-pilgrim: another binarism?, we require space as an ontological category for the curriculum thought when we test, with our theoretical interlocutors, other inspirations about curriculum debate which interrogate binarisms and reductions from space to surface, recorded in attempts to define knowledge.

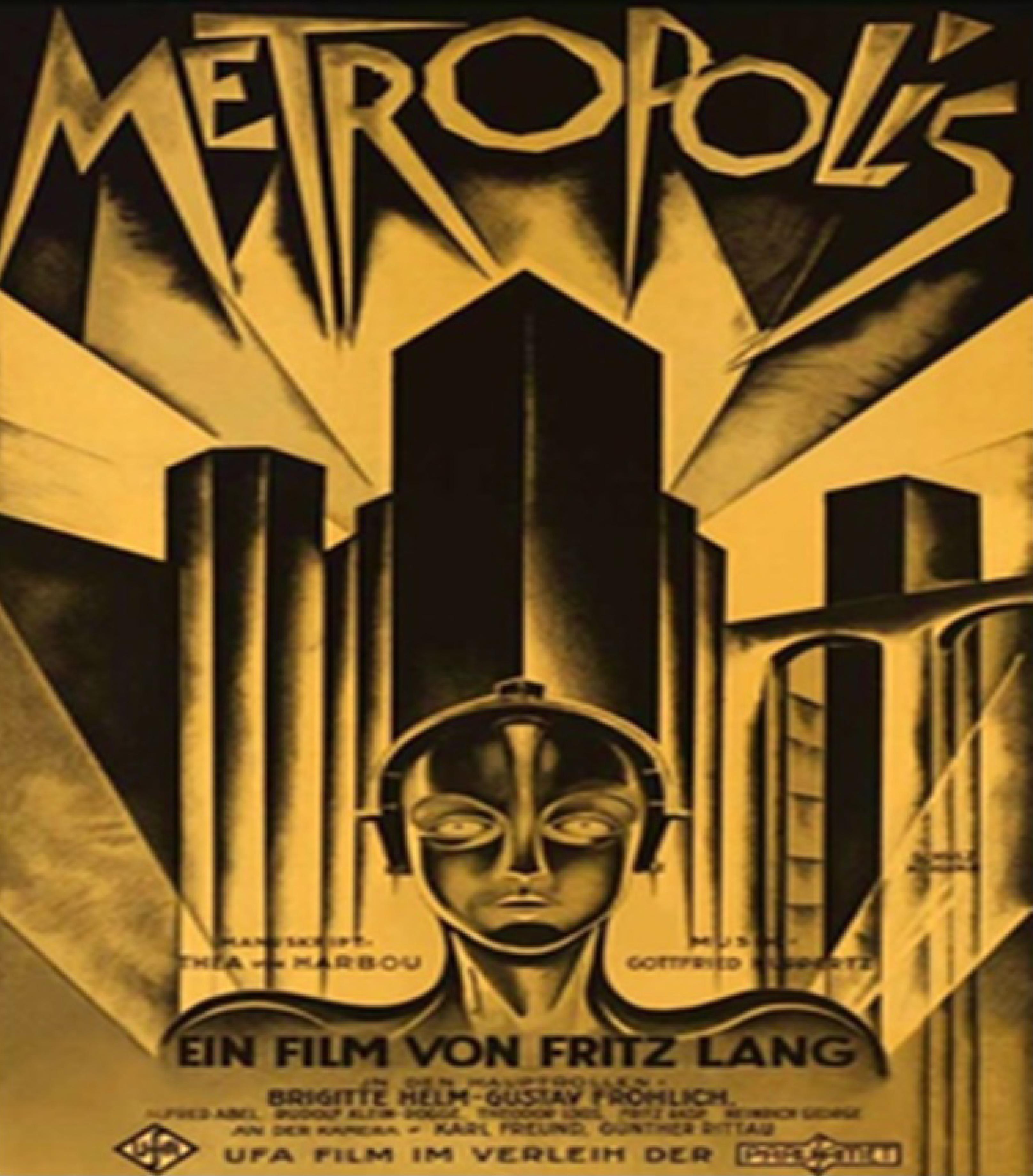

Perhaps also motivated by the power of this relationship, we consider that a metaphor, or according to Doreen Massey’s words (2017), a geographical imagination causes a provisional synthesis about what we consider as the association of curriculum theory with space, in a more intense way. Our metaphor here is to place space as the protagonist like in Fritz Lang´s films, especially in Metropolis (FRITZ LANG, 1927). In this scientific fiction, with a film´s narrative settled in 2026, a city divided between the workers and the privileged class, urban segregation speaks, acts, diverges, and therefore produces geographic imaginations. Metropolis is seminal for our discussion since space-time leads the commissioning. In Metropolis, space is ontological. This reading is in line with Byrne’s reflection (2003) to whom: “Metropolis, just like the film´s title indicates, is a film portrait of a city; the social relations within it are represented in their architecture and in their shapes”. (BYRNE, 2003, p. 5).

Our assumption is that curriculum theory attempts, however, a discussion in which space-time leads our readings. In other words, we recognize Fritz Lang’s power in converting the setting space into a character. The image, therefore, enhanced a spatial reading by proposing the inseparability of the relationship between subject and space. This contribution allows us to attempt a suspicion with this paper: the one that we need to do more frequently a conversation about the relationship between curriculum and space.

Curriculum, knowledge and space: a powerful combination?

The motto of this section, it seems, can be expressed in what is conventionally called power. If we agree that the word powerful is a derivation from power, there are paths that can be opened in the course of this paper. With a step back, it would be immediately necessary to suspend or, at least to translate with some adaptations, the immediate correlation that the powerful derivation of the word can trigger. Pursuing the trail of the words power and powerful, depending on which writing lines shall be mapped, or which authors will be mobilized, contributes to the opening of a real gap between one and the other. But let us keep calm. Let us not throw ourselves into the abyss if, when we look at it, it looks back at us2. Without the obligation to use the dictionary, it can be seen that the meaning of the word powerful is linked to someone who obviously holds the power.

Our objective in this section, when questioning knowledge, in particular, the recent proposals for reviewing Michael Young’s curriculum theory (2007, 2014), intends how modernity operates in space terms with curriculum, as from a knowledge conception. To support this intention, Veiga-Neto’s dialogue (2002) is again appropriate:

In space terms, curriculum has worked – and, certainly, still works – as the major pedagogical device which has replaced, in modern terms, the Greek invention of boundary as a limitation from where others begin; not exactly the limit at which point we get lost, but the limit from which others come into existence for us, the limit from which difference begins to become a problem for us. In summary, curriculum has contributed – and still contributes – to make the other different and, therefore, a problem or a danger for us. (VEIGA-NETO, 2002, p. 165, emphasis by the author).

Veiga-Neto’s above statement (2002) helps us to problematize the limits/dangers of knowledge characterization, sometimes a binary operation of localization, present, for example, in the antagonism interpreted by Michael Young by offering a distinction between powerful knowledge and from the powerful (YOUNG, 2013, 2014).

In another moment (GABRIEL; ROCHA, 2017), we question Michael Young’s trajectory in his ways to differentiate powerful knowledge from the powerful ones, criticizing the very writings that dealt with the “stratification of knowledge” (YOUNG, 1971). The observation we make here is that the attempt to signify the relationship between knowledge and curriculum involves a translation of the spatial perspective.

Our argument, when differentiating knowledge, considers, above all, a relationship of localization of the production and uses of curriculum, which necessarily implies the conception of power that emerges in the exercise of curriculum interpretation. For this reason, it is convenient to us, at this moment, a dialogue with Foucault (2014) to highlight one of the many analysis proposed by him about the relationship between power and space:

Power must be analyzed as something that circulates, or rather, as something that only functions in a chain. It is never localized here or there, never in anybody´s hands, never appropriated as a commodity or a piece of wealth. Power functions and is exercised through networks. In its meshes, individuals do not simply circulate, but they are always in a position to both exercise this power and suffer its effects; they are never the inert or consenting target of power, they are always transmission centers. In other terms, power does not apply to individuals, it passes through them. (FOUCAULT, 2014, p. 284).

But, for what reason, in curricular territories, is it strategic to think of a branched, capillary power? After all, when it comes to curriculum as State policy, are the decisions made not always heteronomous? Would it not be up to curriculum thinkers to occupy the decision centers in the search for a better curriculum? Far from mapping the processes of how a curriculum has been established as an official document (ultimate and undisputed) and if such constitution is heteronomous or not, the view that sees power from its inter-relational ties tends to suspend the presupposed powerful power, determinant, of a specific action.

Assuming that power only exists in operation is to accept, too, that it only exists in transformation (BUTLER, 2017) and, above all, it is to accept that there are spatial processes involved there, i.e.: moving rhizomes of power. A powerful knowledge that is intended regardless of the contexts where it is forged seems, at the outset, to ignore foucauldian formulations of power. At the same time, it allows for a determined logic of space that, in our view, ignores the constitutive multiplicity of spatial at the expense of a displaced knowledge, although universal, and, for that very reason, invariable.

Ultimately, the so-called powerful knowledge, when it does not reach its goal, ends up launching the curricular experience into a fatalistic arena. In Young’s words: “education is concerned, first of all, in enabling people to acquire knowledge that would take them beyond their personal experience, and that they probably could not acquire it if they had not been to school” (YOUNG, 2014, p. 196). Here it is the association between knowledge and personal experience that begins not only to entangle, but also to highlight the entanglement between epistemology and ontology.

As Derrida (1973) argues, by proposing a break with linguistic universalism and opening the way for difference with the interpretation key that every translation is, rather, a betrayal, as it no longer promises an univocal and unquestionable meaning. And, as much as one is attentive to the non-universal, but locational3 character of knowledge, the risks of universalization are still lurking.

At this point, good intentions may be those that betray us. Why should we be surprised by a claiming idea of universal knowledge, such as that unquestionable knowledge, (un)located in an alleged totality? Is it not precisely this kind of knowledge that guarantees, so to speak, equality among all those who acquire it? Probably, it is from the intercession between these questions that it is possible to question the interrelationships between curriculum, knowledge, and space.

In other words, a sense of universal knowledge, sheltered in absolute totality, is to forbid any possibility of localization for those who know it. That is to say, the characterization of a universal knowledge would be a (un)located knowledge, for being applicable everywhere. Here is a trap of classifying the scale of knowledge as universal. That is, any escalating definition of knowledge, a national base, for example, harbors a universal will, of an absolute knowledge.

Should resorting to anthropology, philosophy, geography, and feminist studies, at this moment, be part of a weird movement? Or, in the words of Young (2014, p. 196), “why Derrida? No doubt, he is a brilliant philosopher, but does that mean he is also a curriculum theoretical thinker?” Michael Young’s answer to his own question is categorical: “I don’t believe” (YOUNG, 2014, p. 196).

Contradicting the assumption of the theoretical thinker from London, the permeability of the boundaries between the field of the theories of curriculum with other subjects can, surely, oxygenate the curriculum imaginary and, who knows, generate other visibilities for problems still secondary in the arena of the curriculum debate. A little daring: if space is an ontological category of curricular interpretation, then we can infer that the curricular imaginary resorts to geographic imagination. In other words, the inhabited, lived, and everyday space are integral to the inseparability of space-time-curriculum.

This inseparability implies an scale as a variable of the curricular making a complicated conversation (PINAR, 2016) also when it is determined by the spatial outline, because, after all, every full stop of the curricular text, every curricular decision is a selection producer, a producer of antagonisms also spatial. At the time of deep reforms (or curriculum intentions), it seems to us convenient to think that the curriculum scale is not an accidental adjective. Being national or local in curriculum decisions implies a selection of meanings that exclude other territorial arrangements. To put in another way: the scale of the curriculum is not a minor adjective. It is also a production of spatial speech to impose curriculum decision-making.

In this sense, it is interesting to make some pilgrimages (INGOLD, 2015) to other spaces (FOUCAULT, 2013). Starting from a distinction between transport and pilgrimage, the powerful knowledge, supposedly universal, is, as we shall see, doubly displaced.

The pilgrim is continually on the move. More strictly, he is his movement [...] it is a line that advances [...] in a continuous process of growth and development or self-renewal. As he goes on, however, the pilgrim has to support himself, both in perception and materially, through an active engagement [...] the pilgrim has no final destination, because wherever he is, and as long as his life lasts, there is some other place where he can go (INGOLD, 2015, p. 221, emphasis added).

What must mean to have another place to go when, curiously, we are faced with what is understood as universal? In other words, what must exist beyond the universal, or “from a universal reason, from a single subject, from a truth/knowledge valid for all, [which] still marks contemporary education, [and] especially the curriculum [?]” (TEDESCHI; PAVAN, 2017, p. 679). The developments will be diverse, making the powerful knowledge to become, perhaps, dangerous.

To relaunch an arrow shot by Nietzsche (2015), it is worth remembering that common good, just because it is common, has little value. But how can a common good or a powerful knowledge, capable of reorganizing personal experiences, become dangerous? In a simple and brief way, an answer can be traced through the writings of Arturo Escobar (2016).

Still in this direction, says Foucault (2014, p. 253): “the spatial description of discursive facts leads to the analysis of the effects of power that are linked to it.” Therefore, spatializing powerful knowledge means not only locating and situating its universality, but also understanding its functionality in the constitution of what Escobar (2016) called the Worldly World.

When writing about this idea, Arturo Escobar (2016, p. 22) states that:

[...] perhaps the core aspect of the Worldly World is the ontological division: a specific way of separating humanity from Nature (Nature/culture division) [...] establishing the basis of an institutional structure [...] through which the Worldly World is put into action.

Now, should it not be productive for researchers involved in the curriculum field to investigate the division between nature and culture? In a quick view, without the slightest intention of exhausting the fired binarisms, we can look at the myriad of dualisms related to such separation: civilized, wild; developed, underdeveloped; me, another one; good student, bad student; smart, dumb, etc. Thus, as defended by Tedeschi and Pavan (2017):

[...] we start from the understanding that curriculum, education need to problematize the prevalence of a universal way of existence that tends to frustrate the emergence of other ways; need to consider that we live in a world full of possibilities, and letting the other be another singular being, be something that has not been invented yet, enhances other ways of life. (TEDESCHI; PAVAN, 2017, p. 679).

And, with this same perspective, we hear the echoes of the question asked by Butler (2013, p. 161): “what relationship between knowledge and power makes that our epistemological certainties end up supporting a way of structuring the world that obliterates alternative arrangement possibilities?”.

We suspect that, as a backdrop, the conjunction of a Worldly World and the defense of a powerful knowledge acts in order to generate a specific conception of space that literally serves as a surface where it is possible to erode and exterminate other forms of life and, why not other worlds. That said, it is important to underline that “the understanding of the world is much broader than the western understanding of the world.” (ESCOBAR, 2016, p. 16). Thus, it is in the practice of a theoretical exercise, but no less material, that it is possible to map the appearance of dissonant voices and worlds that, by right, locate what is considered as universal.

What was developed within the modernity project, in other words, was the establishment and the (attempt to) universalizing a way of imagining space (and society/space relationship) that have affirmed the material constraint of certain ways of organizing the relationship between society and space. And that still remains today. (MASSEY, 2015, p. 103).

Indeed, our claim to a conversation between space and curriculum is crossed by conceptions of space that reject a sense of space as a surface. For this reason, it seems to us convenient to review the conception of space, which, according to Massey, involves the refusal of the ultimate foundation and the space–time split. Massey (2015) sought, thus, to praise the multiplicity, the contingency and, not by chance, questioned the perspectives that conceive space as absolute (especially those that see totality as a closed phenomenon) and with that, those that seek the definition of representation of space as an objective apprehension of the real. We understand that the space design project in Massey (2015) prioritizes the political-discursive debate, and here it can be characterized as a post-foundation4 approach to space.

Both in the essays of the 90’s/2000’s as well as his work translated as Pelo espaço (For Space), it is possible to identify a substantively political proposition in the approach of space/spatiality, terms used and defined by her as interchangeable (MASSEY, 2004, 2015). That is, textually, as noun and verb space/spatiality/spatialize are concepts that ritualize coevalness, which for the author would be the impossibility of representing life. We can read here that there is a strong suggestion to understand the effects of the sense of space, which in turn would escape any attempt or strategy of representation, capture or immobility. In the words of the author:

Space is the sphere of the possibility of multiplicity in which different trajectories coexist, i.e. it is the sphere of the possibility of the existence of more than one voice. Without space there is no multiplicity, without multiplicity there is no space. Whether space is undoubtedly the product of interrelations, then this must imply on the existence of plurality. Multiplicity and space coexist. (MASSEY, 2004, p. 8).

Massey, in fact, with this quote valued multiplicity as an agenda for interpreting space that incorporates contingency, moving away from the explanatory model of authorization of space and time dichotomy, which is certainly in favor of extreme democracy agenda (MASSEY, 1992). The guarantee that there is no multiplicity without spatiality, and vice versa, absorbs a quality of criticism to essentialist forms that propose the emptying of an approach of juxtaposition, rhizomes and incompleteness present in theoretical-methodological approaches “closer” to post-structuralism.

The double displacement of powerful knowledge, then, consists of a destitution of its universal status and, on the other hand, in bringing up to the surface, with the establishment of a map (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 2011), the bottomless (LAPOUJADE, 2017) of what seemed stable, consolidated and ready for “deliver[y] to the next generation” (YOUNG, 2013, p. 226). In other words, the task would consist of a cartography of:

[...] particular nexus between power and knowledge that create a field of intelligible objects, [tracking] the point where this field borders on collapse, the moments of their discontinuities, the places where the intelligibility that it supports so much threatens to expire. (BUTLER, 2013, p. 173).

So far, we have pointed out a different conception of power (FOUCAULT, 2014) that, rather than resonating deterministic airs that power acts engender, points to its productive dimension: power produces. Power produces and is produced by spaces and, from now on, the attention of this paper will turn more specifically to the spatial nexus previously signaled. In this sense, the distinction between pilgrimage and transportation will be valuable and more precisely developed. Or, in the words of Doreen Massey (2012, p. 134): “what is at issue, then, is not only the way of organizing space and controlling it but conceptualizing it as well”.

For this reason, our effort in this section is to understand space, knowledge, and curriculum as a powerful combination. In this sense, we test the limits of qualifying knowledge as a locational factor, by critically presenting the vision of reducing space to the absolute, to the metric representation. Betting on opening space, following Massey’s problematics (2004, 2015), we shall pursue in the next section to test the possibility of reconfiguring curriculum and space, as an ontological category.

Knowledge-transport and knowledge-pilgrim: another binarism?

One of the effects of modernity was the establishment of a particular power/knowledge relationship which reflected in a geography that was, in turn, a geography of power (colonial powers /colonized spaces). (MASSEY, 2012, p. 137).

In addition, the curriculum has contributed to time spatialization, i.e. for the understanding that time is reducible to space; it can be thought in terms of space, in the extent that it started being seen as folding to the space. (VEIGA-NETO, 2002, p. 165).

We begin this section with two quotations that should be read in conjunction with our suspicion: that (as curriculum and space interpreters) we need to talk. Doreen Massey (British geographer, deceased in 2016) used to alert us about the effects of modernity meaning on space: the construction of a (geographical) science that produced a relationship between knowledge and power subordinated to the colonial project5. Veiga-Neto (2002) denounces that (modernity) produced a curriculum that subordinated time to space, implying a binary relationship instead of inseparability, longed for the apprehension of Doreen Massey’s (2004) spatiality political philosophy.

It is interesting to note that Doreen Massey (2015) identified that the social sciences, especially anthropology operated space as an ontic category, measurable and subordinated to time. She developed this reflection by identifying the limits of Bergson’s, Laclau’s and Levis Straus’ appropriations among other icons of the humanities in the 20th century. This point in Massey’s spatial argument challenges us to (re)think:

[...] that what is needed is to pull the “space” out of that constellation of concepts in which it has been, so indisputably, so often, involved (stasis, closure, representation) and to establish it within another set of ideas (heterogeneity, coevalness, lived character, no doubt) where a more challenging political landscape is released. (MASSEY, 2015, p. 35).

This quote refers to both structuralism - recognized by Massey as the paradigm that favored the epistemological construction and the identification of the subject Geography - as well as the contribution of post-structuralism to turn the political into a spatial reference. This quote seeks to illustrate the challenge of thinking about space, so that we share the understanding that any exploration of space at school carries a commitment to problematize what Massey (2004) calls political landscape.

Here we exercise a convergence of thinking about the relationship between space and modernity, building a dialogue between Massey (2004) and Veiga-Neto (2002). In other words, the critical interpreters of modernity propose other lenses for the analysis of their respective objects beyond the production of binarisms and universal explanations. At this point, it is advisable to analyze another quote by Veiga-Neto, which lists agenda suggestions for the field of curriculum.

I am interested in discussing an issue that is more, shall we say, of a background. Instead of curriculum engineering, I am more interested in curriculum architecture or, perhaps better said, I am more interested in curriculum geometry. With this, I want to say that I am interested in describing, examining and problematizing the relationships between curriculum and space re-significations – and also time – that are happening in what some call Post-modernity, others call Advanced Modernity and others, still, Second Modernity, Liquid Modernity or Late Modernity. For me, the most interesting question posed here is as follows: “what does the curricular organization of school education have to do with space-time transformations that are taking place in the contemporary world?” (VEIGA-NETO, 2002, p. 167, emphasis by the author).

When proposing curriculum architecture, Veiga-Neto (2002) challenges his reader to claim other curriculum meanings and directly repositioning curriculum, space, and time relationship. Such seizure removes from the curriculum its fixity, the curriculum engineering of knowledge expiration. In addition, the agenda suggested by Veiga-Neto at the beginning of this millennium is convenient for the purposes of this essay: curriculum repositioning is to rethink space as an ontological category. Hence, therefore, the irony implicit in the title of this section: Knowledge-transport and knowledge-pilgrim: another binarism?

For us, the title of this section indicates the risk of updating and falling into a space, again, dual. More than that, because it is a complicated conversation (and, still undone), the danger lies in taking two steps forward, but also two steps back. In other words, stay in the same place. But is that possible? If, on one hand it is important to scrutinize the idea of powerful knowledge, on the other hand, how could we close our eyes to the curriculum seal of selection, legitimation, and organization of knowledge? The paradox lies in the perception that curriculum is a decision and, as Laclau (2000) points out, the contentions of the decision are contingently based. In other words, inspired by Derrida, the decision is a moment of madness.

After all, it is from the so-called powerful knowledge (or from the powerful individuals) that dwell the real statutes in which the evaluative delusions are disputed (VEIGA-NETO, 2012) transvestite in entrance exam vacancies, labor market, master’s degree and PhD studies. In other words, with an agenda where the curriculum is a (political) decision, how would it be possible to turn a blind eye to this (normative) function that regulates lives? Or yet, how can we not close our eyes to such functioning without updating the use of epistemic violence?

A way out, perhaps, is of spatial order. This must mean that there is no prescription ready to be followed. With that in mind, questions like “how does this apply, how do I put this into practice?” have little value. So, if the curriculum has a spatial and spatializing dimension (PINAR, 2009, 2016; ROY, 2002; VEIGA-NETO, 2002, 2007; ALVES, 2001) it is from this dimension that it is interesting to think about what can be called knowledge. With this in mind, we started from two words: method and currere. Although they do not refer immediately to each other, they share meanings, because, after all, “becomings are geography; they are orientations, directions, entrances and exits (DELEUZE; PARNET, 1998, p. 10). Senses, therefore, with at least three senses: sense as something that refers to meaning, sense as something related to direction and sense as something that is felt, that is sensitive6, something as a field of unremarkable intensities: “meaning is divergence, dissonance, disjunction” (ZOURABICHVILI, 2016, p. 67).

The etymology of the word method illustrates the possible interceptions between method and currere. Methodos, composed of met, which means through, by means of, and hodós, which means path (PESSANHA, 2013). In other words, the method could be thought as a path through which a space is traveled, and, at the end of that path, knowledge is obtained. While currere “indicates a focus on understanding the action of ‘running’” (MILLER, 2014, p. 2047), i.e. the walk itself (MILLER, 2014, p. 2047). As for method, what matters is not the trajectory, but the order of the path: contingencies are less encounters than accidents. Now “in currere, curriculum ceases to be a ‘thing’ and becomes more of a process, an action, an involvement with and within the world” (MILLER, 2014, p. 2047).

Deepening this distinction is more than mapping the differences between the idea of method and the idea of currere. On the contrary, such movement is designed to understand the possible correlations between both of them. After all, Pinar (2009; 2016) suggests: currere is a method. Geographical imaginations (MASSEY, 2015) that arise from there, but not yet explained, must also be checked. “The explanation is an implication in something else” (ZOURABICHVILI, 2016, p. 41).

In our case, what is involved, implicating, and complicated, is the space itself. Involved because the explanation of knowledge triggers a spatial narrative to establish itself, implicating because, we return to Massey’s assertion (2004, p. 8) for whom:

[...] without space there is no multiplicity [and] without multiplicity there is no space. [For] if space is undoubtedly a product of interrelations, then this must imply on the existence of plurality: multiplicity and space coexist.

It is complicated because space as a sphere implied within itself does not stop changing its nature - curriculum as space shows a variety of ways of expressing the spatial: disciplinary space (VEIGA-NETO, 2002), space for the production of identities (SILVA, 2005), cultural frontier space-time (MACEDO, 2006) and so on.

In time, it would be necessary to ask what happens to knowledge when it is taken by space, i.e., by the constant difference that keeps revolving and rearranging existence towards directions that do not point to a specific or ultimate end. With Nietzsche’s words (1978, p. 104), we believe that the power of difference reverberates, as if chanting an aphorism, when it comes to knowledge and curriculum. Because:

[...] whoever arrived, even if only to some extent, to the freedom of reason, cannot feel on Earth other than but a wanderer – although not as a traveler towards an ultimate target: for there is none.

Would not a wanderer be a way of existence intimately committed to the contingent multiplicity of space?

In this sense, we understand that the concern between knowledge and truth or, better saying, between thinking as a way to know a true world - and, for that reason, given - ends up erasing all the multiplicity of what can be understood and felt as curriculum or even forms of political action that not necessarily require language of knowledge/truth to establish themselves. In other words, if the curriculum itself is linked to knowledge, we end up not calling into question what establishes and attributes identity to the curriculum. In two questions: what establishes knowledge? Would we be facing a true will? It is not, however, a matter of saying that two plus two is five, even though, at this point literature could make its severe warnings:

And – who knows? – it cannot be guaranteed, but perhaps the only goal on earth, the one towards which mankind tends, lies solely in the constant process of achieving the goal, or, in other words, in life itself and not particularly in the goal, which, of course, must be nothing but two plus two is four, that is, a formula; but, in reality, two plus two is no longer life, gentlemen, but the beginning of death. (DOSTOYEVSKY, 2009, p. 47).

In this scenario, we refer to:

[...] politics of truth belong(ing) to power relations that mark in advance what will qualify and what will not qualify as truth, what will arrange the world according to regular and adjustable modes and what will or will not be acceptable within a given field of knowledge. (BUTLER, 2013, p. 171).

Questioning the normative horizons of knowledge, contrary to what it may seem, is not a way to play a game with ready rules. This because:

[...] if there are rules of recognition [...] and these rules are codes of power operations, then it can be concluded that the dispute over the future [...] will be a battle for the power that works within and through these rules. (BUTLER, 2004, p. 30).

In other words, questioning the normative horizons of knowledge makes it possible to dispute by the very rules of the game that define what counts as knowledge.

Such movement, when translated into the field of curriculum, allows us to shift, for instance, the language of measurements:

[...] that characterize the fields of finance and accounting - which include assessments compared to the ‘audit’ financial process—, [because] test creators and those who prescribe them disregard the nuances, the messy details of lives lived. (MILLER, 2014, p. 2051).

However, it can also displace the dual language of knowledge and failure, which, of course, has its spatial dimensions7 and implications for curriculum concepts with which we can operate. In short, this movement brings to light “the relationship between the limits of ontology, the link between the limits of what I can be and the limits of what I dare to know” (BUTLER, 2013, p. 171).

In this interrelation in which there is a double interception where the limits of what one can be are conditioned to the limits of what we dare to know, Michael Young’s concerns and nervous defenses (2007, 2013, 2014) towards the need for curriculum theories having knowledge as their preferred object are not only legitimate, but also make sense. Here, it is knowledge as a way of theorizing space that matters. That is because, in Haesbaert’s words: “deep down, nothing in this world is without space. The world is space. Our lives are space, they demand space, they fill space, they make space, and they make themselves as space. There is no way out without space.” (HAESBAERT, 2017, p. 286). To think of other spaces is to think of other worlds, in other lives, and that other lives can make other worlds completely different from a Worldly World.

Lives that, in turn, can think beyond space8. Or even where the distinction between life and world, correlates the idea that marks hard boundaries between subject and object; or knowledge as an object appropriated by a subject (MACEDO, 2017), does not work.

The social production of the non-existent clearly accounts for the disappearance of complete worlds, through epistemological operations related to knowledge, time, productivity, and ways of thinking about scales and differences. (ESCOBAR, 2016, p. 15).

To think about scales and differences is to think with space, and it is from an escalating problem that the discussion between knowledge, curriculum and space is again crossed.

This crossing, almost as if by magic, lets a question escape, or, in the same sense, makes a question arise: “what knowledge should compose the curriculum?” (YOUNG, 2014, p. 197). Now, even if such a question does not explicitly evoke space, would it be, for that reason, less spatial? If school time-space, for Nilda Alves (2001), can be thought as a material dimension of curriculum, then this dimension is already implicit and implied on the knowledge relationships that will be established in schools.

The problem, however, seems to be to say what knowledge will make up the curriculum. Bearing in mind that, at the same time that this is done, the space itself is not thought as knowledge, thus becoming a surface where knowledge is deposited: the school starts to function as a depository space for knowledge. In other words, the local scale is no longer seen as a living, pulsating dimension, in which knowledge is produced.

From then on, other questions could be asked: would the limits of what can be not also have spatial dimensions? In this sense, it should not be taken into consideration that “the simple possibility of any serious recognition of multiplicity and heterogeneity in itself depends on a recognition of spatiality [?]” (MASSEY, 2015 p. 31). Or yet, how to think of curriculum and knowledge without the space being excluded and rejected as an active dimension in this combination? What powers could space raise for thought to think the unthinkable? These are questions that, far from having answers, express the desire for paths to be opened.

In this way, we resume the thread trying to interweave different lines that made up this section of this paper. Thinking the unthinkable, more than signifying a voluntarism and willingness to go to the limit of thought, indicates a rearrangement in the way thought is conceived. It is no longer a thought that is intentionally generated by a thinking subject, but a relationship that is established with what is not yet thought. “Encounter is the name of an absolutely external relationship in which thought enters into connection with what does not depend on it.” (ZOURABICHVILI, 2016, p. 52). Surprisingly, the space appears as the privileged dimension for encounters to happen. Thus, getting to know oneself is associated with thinking, and knowledge associated with curriculum, when space is launched into this combination, both thinking and knowing become spatial processes.

A very generous passage from the article Philosophy and politics of spatiality: some considerations, by Doreen Massey (2004), while synthesizing the debate promotes an opening of what can be thought of as space:

The argument is that, for the conceptualization of space/spatiality, it is fundamental to recognize its essential relationship and its constitution through the coexistence of difference(s) – multiplicity, its ability to incorporate a coexistence of relatively independent trajectories. It is a proposal to recognize space as a sphere of encounter, or not, of these trajectories - where they coexist, affect, fight one another. Space, then, is a product of difficulties and complexities, relationship weaving and non-weaving, from unimaginably cosmic to intimately small. Space, to repeat again, is the product of interrelationships. Furthermore, because of this, and as has already been proposed here, space is always in process, in a process of being done, it is never completed. There are always loose ends in space. All this now leads to an additional conclusion. This related character of space, combined with its openness, means that space also always contains an unexpected, unpredictable degree. Thus, like loose ends space always also contains an element of “chaos” (not yet prescribed by the system) [...] Space, in other words, is inherently “disruptive”. Perhaps most surprisingly, given hegemonic conceptualizations, space is not a surface. (MASSEY, 2004, p. 17).

So, if curriculum has an undeniably spatial dimension and, space is an immediately uncontrollable and unpredictable dimension, what would then happen to knowledge? The distinction initially evoked between transport and pilgrimage can be, at last, unfolded. While “transportation [...] is essentially destination-oriented” (INGOLD, 2015, p. 221), “pilgrimage is our most fundamental way of being in the world” (INGOLD, 2015, p. 224). In the idea of knowledge-transport, the student “himself does not move. On the contrary, he is moved, becoming a passenger in his own body” (INGOLD, 2015, p. 221). As for pilgrimage, knowledge can be thought as “paths along which life is lived [...] precisely because knowledge, in this sense, is open and not closed, because it merges with life in an active process” (INGOLD, 2015, p. 224-237). The idea of knowledge transmission loses territory without necessarily, the knowledge itself is thrown away – since it is the outside of the thought that animates it. Learning becomes a continuous process of engagement, always unfinished and never totalizable. A nuisance, however, persists. So many lines to fall into another binarism?

Another annoyance: how to convert apparent binarism into potent ambivalence? This exercise, without pretending to exhaust space, had the intention that, in the neoconservative conjuncture of curricular propositions, it is necessary to write aspiring to the tactic of repositioning (curriculum) questions. For this reason, the pilgrim and transport metaphors in Ingold (2015) inspire us to identify, in fact, that it would be opportune to rethink binarism as an ambivalence that would reflect other approaches to the problem of curriculum scale, for example.

After all, how to deconstruct the speech of transportation in the current curriculum propositions and to re-signify the pilgrim’s power? This is not a replacement for the meaning of curriculum. Above all, is it about inscribing questions that bother the curriculum implementation process, or exclaiming about the infertility of curriculum engineering? Indeed, without the desire to accommodate the text, with an agenda or a proposal for a matrix to rethink the link between curriculum and space, our provocations signal a willingness to talk about this relationship.

Some considerations

In concluding, we are interested in (making) an escape from space and curriculum split. We would like this paper to draw attention to the poverty of reducing the relationship space and curriculum to localization (a closed system of positions, ignoring space as a non-totalizable, but disruptive, inter-relational plot). We dare to stress interpreters in the field of curriculum, by insisting that we do not occupy ourselves with space in theoretical exercises. For this reason, this essay operated with binarism insufficiency to problematize curriculum and space relationship, defending it as an ontological category for our studies.

For such reasons, Fritz Lang’s film metaphor still seems dear to us by making, still in 1927, from scene image the protagonist of space: screenwriters, director, actors, and photographers slid in the performances the becoming of space. Thus, being possible, to question the “space that grinds us”, as Foucault (1967, 2001) would say, because, after all:

The space which we live in, which takes us outside of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives, our time and our history takes place in a continuous way, the space that grinds us, is also, in itself, a heterogeneous space. In other words, we do not live in a kind of vacuum, in which individuals and things are placed, in a vacuum that can be filled by various shades of light. We do live in a series of relationships that outline places that are decidedly irreducible to each other and that cannot overlap. (FOUCAULT, 2001, p. 415, emphasis added).

To the audience of German architects, in 1967, Foucault warned about the impossibility of outlining space, as it was not possible to conceive it fixed, alienable. On the contrary, we live in decidedly irreducible places. This implies rethinking space as a multiple and no longer as a surface. It is interesting to note that Foucault’s geographical contribution took place in Berlin, Thea von Harbor’s, and Fritz Lang’s inspiring city for Metropolis, one of the icons of German expressionism. Urban segregation, spatial functions and processes spoke in their filmic imagery forms.

After all, if we still agree with Didi-Huberman (2012 p. 404) for whom “One of the great forces of the image is to create at the same time symptom (interruption of knowledge) and knowledge (interruption of chaos)”, we are inspired to think that there are crossings over the real between curriculum and space; and that symptom and knowledge operate simultaneously between curriculum and space.

Still in a dialogue with Didi-Huberman (2012), our space defense as an ontological category would be in transit between “symptom (interruption in knowledge) and knowledge (interruption in chaos)” (DIDI-HUBERMAN, 2012, p. 214), which made Metropolis’ geographical imagination a production in a sense of the future in which the city dictates and segregates into becoming. In other words, Metropolis converted the scenic space into a character, which invests in a meaning of space that does not reify us nor give us its relationships to say who we are.

Our bet on space as an ontological category is to give up space as a scenic surface and take it as a character. Such insinuations about space in this paper claim that our insurgencies about neo-conservative propositions of the curriculum require the act of mapping our geographical imaginations that support the validation of true knowledge. This is because it seems to us that rethinking space in the field of curriculum requires us to reflect on its relationship with knowledge.

It should be noted that our exercise did not propose a matrix for the curriculum and space relationship; on the contrary, we understand that there are multiple paths for a spatial reading of curriculum. For these reasons, Veiga-Neto’s (2002) distinction between curriculum engineering and architecture seems to us precious. That compels us to take seriously the fact that thought can only think the new in an unpredictable and totally contingent connection. In other words, to take on that the new cannot be voluntarily built.

In a strong sense, thought is no longer linked to an abstract and universal will of truth, but it is related to “a new image of thought [which] initially means the following: truth is not an element of thought. The element of thought is meaning and value.” (DELEUZE, 1976, p. 49). Meaning, not by chance, refers not only to meaning, but also to direction and sensitive as well. “Truth concept is determined only in terms of a pluralist typology. And the typology starts with a topology” (DELEUZE, 1976, p. 50). Topology that makes an announcement: “thinking depends on certain coordinates.” (DELEUZE, 1976, p. 52). Variable coordinates which, at a constant process of change, indicate how much spatial thinking is involved.

It is from this spatial dimension that truth is rearranged. “We have truths that we deserve according to the place where we put our existence, the time we are awake, the element we attend.” (DELEUZE, 1976, p. 52). This situated or localized truth supports a difference that cannot be colonized. This is because, “there are different perspectives from different worlds – and not different views from the same world” (COSTA, 2014, p. 71).

This means to say that the relativity of truth is not the same as the truth of the relative. This is no longer a “relativism, i.e., the affirmation of the relativity of true, but a relationalism, through which one can affirm that the truth of the relative is the relation.” (VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, 2002, p. 129). And space, again, appears as an active element in this combination.

Therefore, if space can be thought as a product of interrelations (MASSEY, 2004, 2012, 2015), it appears as the privileged dimension in which ontology and epistemology are confused; as an indomitable, conceptual component (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 2010) which does not submit to the language of identity and representation – correlate to the ideas of model and copy.

Space is a difference in itself, which is constantly changing and, having, for this reason a disruptive excellence. In this respect, curriculum, knowledge and space are shown as a combination, literally, explosive. An explosion that generates an opening. It is an affirmation that knowledge, when it is thought from its inter-relational ties, does not require the copy to be identical to the model to be true.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Nilda. Imagens das escolas: sobre redes de conhecimentos e currículos escolares. Educar, Curitiba, n. 17, p. 53-62, 2001. [ Links ]

BIESTA, Gert. Boa educação na era da mensuração. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 27, n. 147, p. 808-825, set./dez. 2012. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. A vida psíquica do poder: teorias de sujeição. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2017. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Deshacer el género. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2004. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. O que é a crítica? Um ensaio sobrea virtude de Foucault. Cadernos de Ética e Filosofia Política, São Paulo, n. 22, p. 159-179, 2013. [ Links ]

BYRNE, Deirdre. The top, the bottom and the middle: space, class and gender in Metropolis. Literator, Johanesburgo, v. 24, n. 3, p. 1-14, nov. 2003. Disponível em: https://literator.org.za/index.php/literator/article/view/298/271. Acesso em: dez. 2018. [ Links ]

COSTA, Claudia Lima. Equivocação, tradução e interseccionalidade performativa: observações sobre ética e prática feministas descoloniais. In: BIDASECA, Karina et al. (org.). Legados, genealogías y memorias poscoloniales: escrituras fronterizas desde el Sur. Buenos Aires: Godot, 2014. p. 273-307. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. Bergsonismo. São Paulo: 34, 1999. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles. Nietzsche e a filosofia. Rio de Janeiro: Rio, 1976. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. Mil Platôs: capitalismo e esquizofrenia. v. 1. São Paulo: 34, 2011. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. O que é a filosofia? São Paulo: 34, 2010. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; PARNET, Claire. Diálogos. São Paulo: Escuta, 1998. [ Links ]

DERRIDA, Jacques. Gramatologia. Tradução de Miriam Chnaiderman e Renato Janine Ribeiro. São Paulo: Perspectiva. 1973. [ Links ]

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. Quando as imagens tocam o real. Revista da Pós EBA/UFMG, Belo Horizonte, v. 2, n. 4, p. 204-2019, nov. 2012. Disponível em: https://eba.ufmg.br/revistapos/index.php/pos/article/download/60/62. Acesso em: dez. 2018. [ Links ]

DOSTOIÉVSKI, Fiódor. Memórias do subsolo. Rio de Janeiro: 34, 2009. [ Links ]

ESCOBAR, Arturo. Sentipensar con la tierra: las luchas territoriales y la dimensión ontológica de las epistemologías del Sur. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, Madrid, v. 11, n. 1, p. 11-32, jan./abr. 2016. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Microfísica do poder. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2014. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. O corpo utópico, as heterotopias. São Paulo: n-1, 2013. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Outros espaços. In: FOUCAULT, Michel. Ditos e escritos IIII. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2001. p. 411-422. [ Links ]

FRITZ LANG (dir.). Metropolis. Produzido por: Erich Pommer. Berlim: Universum Film Aktien Gesellschaft, 1927. [ Links ]

GABRIEL, Carmen Teresa; ROCHA, Ana Angelita. Seleção do conhecimento como operação hegemônica. ETD, Campinas, v. 19, p. 844-863, 2017. [ Links ]

HAESBAERT, Rogério. Por amor aos lugares. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2017. [ Links ]

HARAWAY, Donna. Saberes localizados: a questão da ciência para o feminismo e o privilégio da perspectiva parcial. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, n. 5, p. 7-42, 1995. [ Links ]

INGOLD, Tim. Estar vivo: ensaios sobre movimento, conhecimento e descrição. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2015. [ Links ]

LACLAU, Ernesto. Misticismo, retorica y política. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2000. [ Links ]

LAPOUJADE, David. Deleuze, os movimentos aberrantes. São Paulo: n-1, 2017. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Currículo como espaço-tempo de fronteira cultural. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 11, n. 32, p. 285-286, maio/ago. 2006. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Mas a escola não tem que ensinar? Conhecimento, reconhecimento e alteridade na teoria do currículo. Currículo sem Fronteiras, Pelotas, v. 17, n. 3, p. 539-554, set./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

MARCHART, Olivier. El pensamiento político posfundacional: la diferencia política em Nancy, Lefort, Badiou y Laclau. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2009. [ Links ]

MASSEY, Doreen. Algunos tiempos de espacio. In: ALBET, Abel; BENACH, Núria. Doreen Massey: un sentido global del lugar. Barcelona: Icaria, 2012. p. 182-196. [ Links ]

MASSEY, Doreen. A mente geográfica. GEOgraphia, São Paulo, v. 19, n. 40, p. 36-40, 2017. [ Links ]

MASSEY, Doreen. Filosofia e política da espacialidade: algumas considerações. GEOgraphia, Niterói, v. 6, n. 12, p. 7-23, 2004. [ Links ]

MASSEY, Doreen. Pelo espaço: uma nova política da espacialidade. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2015. [ Links ]

MILLER, Janet. Teorização do currículo como antídoto contra a cultura da testagem. E-curriculum, Niterói, v. 12, n. 3, p. 2043-2063, ago./dez. 2014. [ Links ]

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich Willhelm. Obras incompletas. São Paulo: Abril, 1978. [ Links ]

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich Willhelm. Para além do bem e do mal. São Paulo: Martin Claret, 2015. [ Links ]

PESSANHA, Fábio Santana. A hermenêutica do mar: um estudo sobre a poética de Virgílio de Lemos. Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro, 2013. [ Links ]

PINAR, William. Estudos curriculares: ensaios selecionados. Seleção, organização e revisão técnica de Alice Casimiro Lopes e Elizabeth Macedo. São Paulo: Cortez, 2016. [ Links ]

PINAR, William. Multiculturalismo malicioso. Currículo sem Fronteiras, Pelotas, v. 9, n. 2, p. 149- 168, jul./dez. 2009. [ Links ]

RANNIERY, Thiago Moreira de Oliveira. Mapas, dança, desenhos: a cartografia como método de pesquisa em educação. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 23, n. 3, p. 159-178, set./dez. 2012. [ Links ]

ROY, Kaustuv. Gradientes de intensidade: o espaço háptico deleuziano e os três erres do currículo. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 27, n. 2, p. 89-109, 2002. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2005. [ Links ]

TEDESCHI, Sirley Lizott; PAVAN, Ruth. Currículo e espistemologia: a descriação da identidade/universalidade e a criação da diferença/multiplicidade. Currículo sem Fronteiras, Porto Alegre, v. 17, n. 3, p. 678-698, set./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO. Alfredo. As duas faces da mesma moeda: heterotopias e emplazamientos curriculares. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 45. p. 249-264, jun. 2007. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, Alfredo. Currículo: um desvio à direita ou delírios avaliatórios? [Conferência]. In: COLÓQUIO SOBRE QUESTÕES CURRICULARES, 10., 2002 e COLÓQUIO LUSO-BRASILEIRO DE CURRÍCULO, 6., 2002, Belo Horizonte. Anais... Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2002. p. 1-15. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, Alfredo. De geometrias, currículo e diferenças. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, n. 79, p. 163-186, ago. 2002. [ Links ]

VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo. O nativo relativo. Mana, Rio de Janeiro, v. 8. n. 1, p. 113-148, 2002. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Michael (org.). Knowledge and control: new directions in the sociology of education. London: Collier-Macmillan, 1971. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Michael. Para que servem as escolas? Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 101, p. 1287-1302, 2007. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Michael F. D. Superando a crise na teoria do currículo: uma abordagem baseada no conhecimento. Cadernos Cenpec, São Paulo, v. 3, n. 2, p. 225-250, 2013. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Michael. Teoria do currículo: o que é e por que é importante. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, n. 151, p. 190-202, 2014. [ Links ]

ZOURABICHVILI, François. Deleuze: uma filosofia do acontecimento. São Paulo: 34, 2016. [ Links ]

2- We refer here to a well-known aphorism by Nietzsche: “(2015, p. 85): “[...] He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.””.

3- About this localization, writes Haraway (1995, p. 23-24): “the alternative to relativism is partial, localizable, critical knowledge, supported by the possibility of connection networks, called solidarity in politics and shared conversations in epistemology. Relativism is a way of not being anywhere, but claiming that you are equally everywhere. The ‘equality’ of positioning is a denial of both responsibility and critical evaluation. In the ideologies of objectivity, relativism is the perfect mirror twin of totalization; both deny interest in location, embodiment and partial perspective; both make it impossible to see well.” I understand that being equally everywhere refers to the possibility of establishing some kind of universal knowledge, and also for this reason, disembodied knowledge. The end of this paper tries to distance itself from the tension between relativism and objectivity, rescuing another proposal so that knowledge can be thought as from inter-relational ties.

4- Post-foundationalism, according to Marchart (2009), can be understood as a theoretical perspective that defends the constitution of contingency and disputes of meanings in the interpretation of the political phenomenon. In short, post-foundational thinking challenges the foundation, but does not deny it, thus reinforcing the struggle for duration, for the contingency of the foundation “The dissolution of the frameworks of certainties” (LEFORT, apud MARCHART, 2009, p. 19) would be the epistemological project that links post-foundational theories. With this definition of post-foundationalist thinking, Marchart (2009) quotes Heidegger’s, Wittgenstein’s studies and, more in the second half of the 20th century, Ernesto Laclau’s proposal for the theory of hegemony, for instance.

5- For Massey (2004, p. 14), the school of French structuralism has influenced the conversion of space into time, particularly in the construction of classifications, or typologies of Anthropology, which usefulness of explanatory models was based on pairs of adjectives like “primitive-civilized”. In addition, according to the author, the exceptionality of structuralism would have been to promote non-temporal structures, such as spatiality, establishing the divorce between space and time.

6- Regarding the relationship between sensation and space, writes Deleuze (1999, p. 70): “there is no reason to ask if there are spatial sensations, which are and which are not: all our sensations are extensive, all are ‘voluminous’”.

7 - A temporal narrative of curriculum could contribute to the metrification and scanning of the curriculum space. Although it is not specifically speaking of a curriculum, this argument can be seen in Massey (2015, p. 107): “under modernity, not only was space conceived as divided into delimited places, but this differentiation system was also organized in a particular way. In short, the spatial difference was conceived in terms of temporal sequence. Different places were interpreted as distinct stages in a single temporal development. All stories of progress, unilinear, modernization, development, the sequence of modes of production ... represented this operation [...]. Requalifying euphemistically ‘backward’ as ‘in development’, and so on, does nothing to change the meaning, and the import of the fundamental maneuver: that of making spatial heterogeneity coexist in a single time series”. Now, if the key to thinking about the “backwardness” of nation-states is a temporal narrative of space, the process in curriculum territories does not seem to be very different. Students, when placed in the same time sequence, start to respond in a similar way about learning expectations. “Although this seems to be an attractive and emancipatory ambition, it is common to forget that, once the goal is reached” (BIESTA, 2012, p. 815), the space starts to be conceived as a surface, or even as the “promised land” which we should get to.

8 - About this, says anthropologist Tim Ingold: “I would like to argue [...] against the notion of space. Of all the terms we use to describe the world we live in, it is the most abstract, the emptiest, the most outstanding of the realities of life and experience. [...] Farmers plant their crops on land, not in space, and harvest them from the fields, not from space. Your animals graze pastures, not space. Travelers cross the country, not space. Painters set up their easels in the landscape, not in space. When we are at home, we are indoors, not in space, and when we go outdoors, we are in the open, not in space. Looking up, we see the sky, not space, and one windy day we feel the air, not space. Space is nothing, and because it is nothing it absolutely cannot be inhabited.” (INGOLD, 2015, p. 215 emphasis by the author). Such a conception certainly refers to the idea of space as an isotropic surface, an idea that associates space with a specific conceptual constellation of “stasis, closure [and] representation” (MASSEY, 2015, p. 34). Conceptual constellation that, in this article, is shifted as space is associated, according to Doreen Massey, to the ideas of “heterogeneity, relationality, coevalness [...] vivid character” (MASSEY, 2015, p. 35). In short, the defense of a world without space seems to ignore the very spatial character of the world.

Received: February 09, 2019; Accepted: May 08, 2019

texto em

texto em