Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 17-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046219060

SECTION: ARTICLES

2- Rede Municipal de Ensino de São José dos Pinhais, São José dos Pinhais, Paraná, Brasil. Contact: margrochoska@yahoo.com.br.

3- Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Contact: andreabg@ufpr.br.

The article starts from the definition of the concept of teacher valuation articulated with the quality of teaching and teachers’ quality of life. It problematizes, specifically, the second dimension, analyzing the career from the perspective of teachers’ perception of professional valuation and quality of life in two municipal education systems in the state of Paraná (Brazil): Piraquara and São José dos Pinhais. It is a double case study of two cities with different economic contexts, one with greater resources for education and the other with less. The study consists of a documental analysis of the Planos de Carreira e Remuneração [Career and Remuneration Plans] and a survey on teachers’ perception of the conditions of their career and quality of life. It is noteworthy that the survey had a statistically meaningful sample of teachers from each municipal school system. Among the conclusions, it was confirmed that the perception concerning the valuation of teachers is related to remuneration increase, valuation of qualifications, significant starting salary and work conditions, highlighting the number of students assisted. A new element observed is the need of a valuation policy that has clear objective and agile career procedures as conditions for safety and predictability for building a perception of quality of life conditions.

Key words: Education Policies; Teaching Valuation; Career and teachers’ quality of life

O artigo parte da definição do conceito de valorização docente articulada à qualidade de ensino e à qualidade de vida dos professores. Dedica-se a problematizar, especificamente, a segunda dimensão, tomando a carreira a partir da percepção dos professores acerca da valorização profissional e da qualidade de vida em duas redes municipais de ensino do Estado do Paraná: Piraquara e São José dos Pinhais (PR). Trata-se de estudo de dois casos em municípios com diferentes contextos econômicos, um com maior aporte de recursos para educação e outro com menor. O estudo compõe-se de análise documental dos Planos de Carreira e Remuneração e de um survey a respeito da percepção dos professores acerca das condições de sua carreira e qualidade de vida. Destaca-se que o survey contou com uma amostra estatisticamente significativa de professores em cada rede municipal. Entre as conclusões, confirma-se que a percepção acerca da valorização docente está relacionada a avanços remuneratórios, valorização das titulações, significativo vencimento inicial e condições de trabalho, dando destaque ao número de alunos atendidos. Como elemento novo, evidencia-se a necessidade de a política de valorização sustentar-se em clareza, objetividade e agilidade dos procedimentos de carreira como condições de segurança e previsibilidade para a construção da percepção de condições de qualidade de vida.

Palavras-Chave: Políticas educacionais; Valorização docente; Carreira e Qualidade de vida dos professores

Introduction

The theme of this article is the investigation of elementary teachers’ valuation, having as its object of study their career. Considering the debates concerning valuation and career, the study focused specifically on reflections concerning the perception of these teachers in respect to their quality of life. We base the debate of these elements on the understanding that the valuation of teachers should be understood not only as a principle for the quality of education, but also as a principle for the quality of the worker’s life.

The methodology chosen for the elaboration of reflections concerning teachers’ valuation and quality of life was a double case study of two Brazilian cities, São José dos Pinhais and Piraquara. Each municipality has its own economic condition; while the first has a favorable context for the implementation of valuation policies, the latter, Piraquara, does not have the same conditions to guarantee these policies. Data collection was obtained through documentary analysis and the application of a closed questionnaire to a statistically representative sample of teachers from both municipal education systems. The sample of teachers comprised elementary education professionals – pre-school and initial years of elementary school – from both municipalities.

This article will initially present a brief theoretical framework of the concept of teaching valuation; then, it will address the context of the municipalities and teachers that work in these education systems; finally, it will present data that aim to understand the elements that make teachers of both municipalities acknowledge that their work provide them with quality of life. With this approach, we intend to contribute to reflect on the possibilities of the effectiveness of the constitutional principle of valuation of teaching professionals in a context of resistance to the dismantling of education policies.

The valuation of education professionals: is there consensuses regarding this theme?

There is great consensus regarding the need to value educational professionals, however, there are several ways of approaching this issue. We can identify at least three different directions for this discussion: 1) an approach concerning the process of teacher proletarianization (FERREIRA; BITTAR, 2006) that questions the quantitative expansion of teaching professionals in conjunction with the expansion of the teaching system itself, which implies understanding changes on the profile of these professionals in Brazil, particularly after the 70s; 2) a more international debate regarding the challenges of the professionalization of teachers (NÓVOA, 1995; DARLING-HAMMOND, 2017), implying initial and in-service training conditions, professional insertion and autonomy in the exercise of their work; 3) studies that indicate as central categories the ideas of tension between valuation, devaluation and intensification of teachers’ work (OLIVEIRA, 2010), placing the work of these professionals within the context of education policies and changes on the organization of the contemporary school.

These paths for debate build, as a consensus, the centrality of the teaching profession in education policy and the urgency of valuation, but they also contain nuances of how to look at the profession in this moment of organization of the contemporary society. It can be affirmed that this debate reveals the meaning of professionalization as a social construct that results from two processes: one related to the set of public policies for teachers (attraction for the career, permanence conditions and teacher substitution conditions) and education financing policies. The other process refers to the set of collective actions of struggle for professional recognition that happen, among others, through union struggle.

The existence of a constitutional principle of valuation of school education professionals in the text of the 1988 Constitution is the result of a historical process of organization and dispute on the part of the workers, but it is also a mark of a cognitive reference (LEFORT, 1983) of both public policies and new struggles to put the principle into effect. Therefore, to understand valuation in elements that allow the comprehension and evaluation of current policies requires the ability to specify these elements. In this sense, valuation is defined as:

A constitutional principle that takes effect through a legal mechanism called career, which developed through three elements: a) education, b) work conditions and c) remuneration, having as its objectives the quality of education and the quality of worker’s life. (GROCHOSKA, 2015, p. 28).

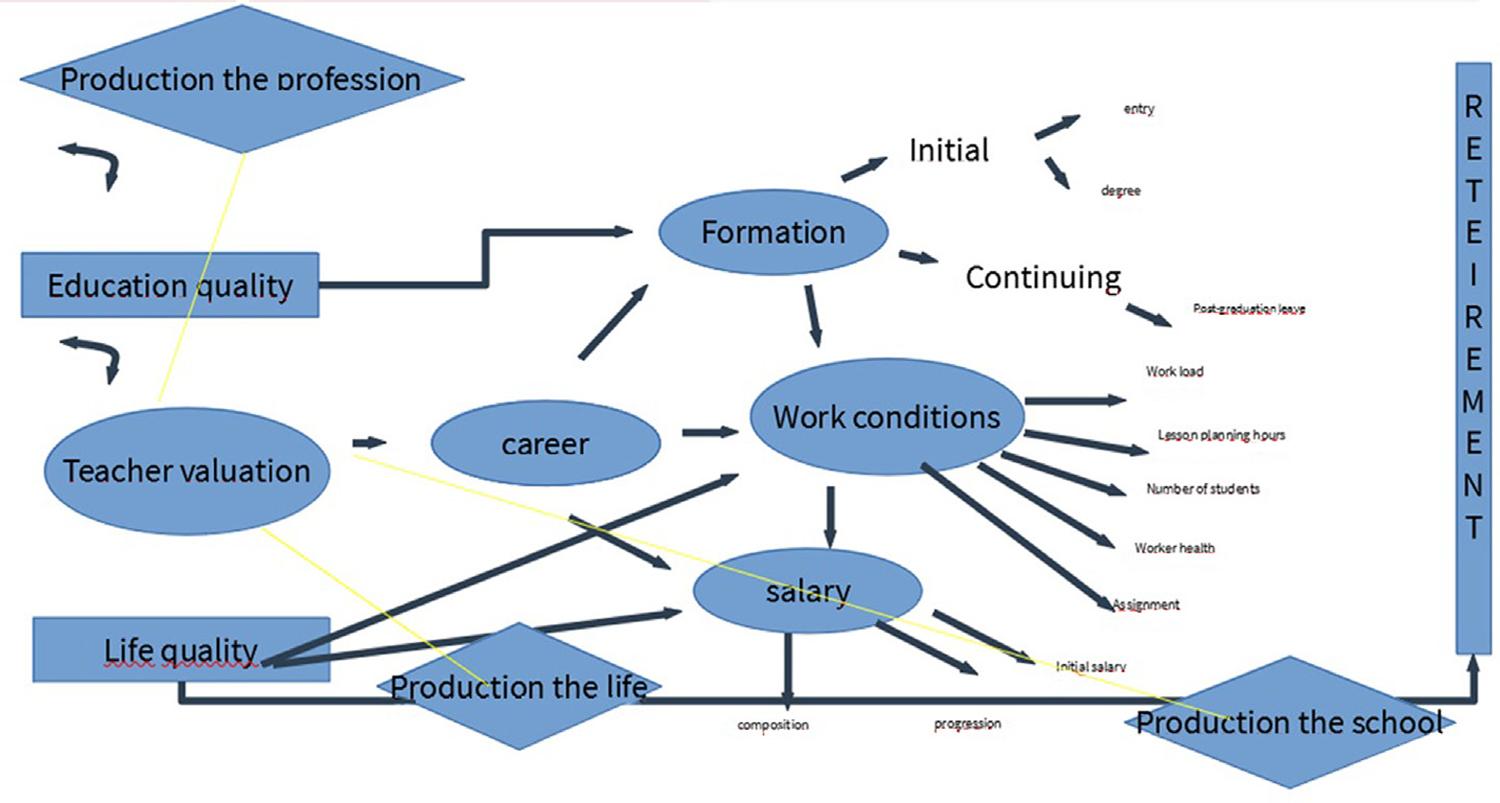

This concept of career results from the understanding that it is a legally instituted mechanism, which defines norms and rules that enable the development of teachers’ functional life (promoting or not their valuation), aiming to reach teachers’ retirement age. Figure 1 shows the movement that such concept seeks to capture between education quality, defined by the author as conditions to produce the school and quality of life of the worker, defined in the sense that it is through teaching that the teachers produce their own lives.

The need to value teachers so that they have quality of life is sustained in a proposal by Nóvoa (1995) who points out the importance of teachers consolidating three dimensions: personal development—production of teacher’s life, professional development—production of the teaching profession; and organizational development—production of the school. These concepts are used in the author’s work to reflect on teachers’ education; however, given the range of reflections that the concepts might represent, we chose to insert them in the reflections related to valuation and quality of life, considering that, in order for teachers to be able to produce their lives, their profession and the school, three elements are necessary: education, work conditions and remuneration.

The teacher is a person. And an important part of the person is a teacher (Nias, 1991). Therefore, there is an urgent need to find spaces of interaction between the personal and professional dimensions, allowing teachers to appropriate their education processes and give them meaning in the context of their life stories. (NÓVOA, 1995, p. 25).

It is in this sense that the valuation elements are related to the way teachers produce their lives (with or without quality) and interfere in their work and vice versa. Here is the reasoning:

The valuation of the teacher is the principle to reach two objectives: the first, quality of national education, and the second, quality of life for the worker. These two objectives are necessary for teachers to produce their lives, the school and their profession, as pointed out by Nóvoa (1995). In order to reach these two objectives, there is a legal mechanism that is the career. For this career to be a mechanism of valuation, three elements are necessary: education, work conditions and remuneration. These primary elements are composed of the other dimensions, seeking greater objectivity in the realization of the policy. (GROCHOSKA, 2015, p. 99).

Therefore, in this context, it is understood that quality of life can be represented differently by each teacher, according to their context, experiences and habitus (BOURDIEU, 2002), but always related to their well-being.

We conclude, thus, that the concept of quality of life is constituted from complex elements and innumerable variables, since what is considered quality of life for one teacher, might not be for another. Understanding that this representation is built in a municipality with a positive financial situation and in another with less economic possibilities will contribute to the reflections on what elements are important and consolidate the principles of valuing elementary education teachers.

Similar concerns arise in the international debate about public policies for teaching. A reflection in this direction can be found, for example, in the work by Darling-Hammond (2017) about policy systems for the education and development of teachers in different countries, as summarized by the author:

The systems in these nations [Finland, Singapore, Canada and The United States] encompass the full range of policies that affect the development and support for teachers and school leaders, including the recruitment of qualified individuals into the profession; their preparation; their induction; their professional development; their evaluation and career development; and their retention over time. Leaders in these jurisdictions recognize that all of these policies need to work in harmony or the systems will become unbalanced. For example, placing too strong an emphasis on recruitment without concomitant attention on development and retention could result in a continual churn within the teaching profession. (DARILING-HAMMOND, 2017, p. 294).

This contextual element of the conditions of teacher insertion shapes the perception of quality of life and, therefore, allows us to consider that the subjective dimension of the relationship with work is articulated with an objective dimension that supports the perception. In other words, the study observes, in two different municipal contexts, which objective elements are noticed by the teachers subjectively as conditions of valuation. This movement seeks to analyze the policy in order to reflect on what challenges the legislation and policy practices for teachers need to face so that these professionals can be happy in their work.

The municipal contexts under debate

São José dos Pinhais, as mentioned before, is a city with favorable economic conditions for the development of teacher valuation policies. It is characterized as an automotive hub with several companies in this production chain, contributing to the highest tax collection in the state of Paraná (Brazil). It has a population of 302.759 inhabitants with a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.758 (IBGE, 2010) and a GINI index of 0.4599.

Concerning the education context, the city has its own education system since 2004. It has pre-school and elementary education (initial years) students, with 30.290 enrollments in 2016 (INEP, 2016). The city has a total of 1.213 (INEP, 2016) teachers in the municipal system, with a 20-hour workload and higher education, all of whom entered through public examinations. There are some teachers in the municipality who have extended their working hours to 40 hours through a work contract called Jornada Integral de Serviço (JIS) [Integral Service Day]. It is important to highlight, however, that this kind of contract is considered harmful to teachers’ career, since it depends on the appointment of the principal of the work unit, it lasts 6 months, there is no payment for vacation, 13th salary, the month of January nor retirement contribution. Concerning teachers’ careers, the municipality of São José dos Pinhais has one of the best starting salaries for teachers of the Metropolitan Area of Curitiba, which is R$ 2,149.72 (2016).

However, some aspects need to be considered to understand the conditions of teachers’ work. One of them, for example, is that teachers do not have their own teaching career plan, but are part of the São José dos Pinhais’ public servant statute, Law 525/2004. This is not a problem in itself, but this plan is outdated in view of the new national legislation of the last decades, especially regarding the aspects of the PSPN [National Professional Salary] Law (BRASIL, 2008).

Besides this, in the process of implementing the plan in 2004, there were many salary distortions among the different positions due to problems in the qualification of education professionals. In the transition between the previous and the new career plan, only the salary floor was considered, incorporating gratifications and allowances that some public servants already received. Criteria such as qualification and length of service were left out, causing a huge salary distortion to the point that in the year 2005, in the first public examination held in the municipality, after the implementation of the new career plan, the new teachers started their career with salaries much higher than those of the professionals who had been working in the municipality for a long time.

This generated discontentment, triggering many mobilizations to change this scenario. Only in 2009 did this situation ease, with a reframing of the professionals who were earning much less than the starting salary proposed in the new plan, that is, teachers who had been teaching before the new career plan had salaries around 50% lower than the salaries of teachers who entered with the new public examinations. At the end of 2016, after a group of teachers won the case in court, all others managed to re-qualify, however, a great portion is still in disadvantage in relation to current remuneration.

We can say that clear and objective framing criteria, such as qualification, length of service and basic salary are important elements of valuation in the process of transition from one career law to another, but, in the case of São José do Pinhais, even being an economically favored municipality, this change did not bring advances in the valuation, on the contrary, it created a lot of dissatisfaction among these professionals.

The second municipality for analysis is Piraquara, also located in the Metropolitan area of Curitiba. It is a municipality with 106,132 inhabitants (IBGE, 2020). As it is located in a watershed area, the legislation prohibits the installation of industries, which hinders the growth of tax collection, generating great difficulty for investments in social policies, including education. It has an HDI of 0.700 (IBGE, 2010) and a GINI Index of 0.4307.

Regarding its education context, Piraquara has 22 schools and 15 primary education centers, with 10,792 (INEP, 2016) enrollments in pre-school and elementary school. The city has 710 permanent teachers, with a workload of 20 hours. Many of these professionals increase their number of teaching hours, which happens as regulated in the career legislation, called Supplementary Regime.

The Supplementary Regime is a fixed-term contract, that is, a temporary employment contract. The difference in relation to São José dos Pinhais is that Piraquara has all the regulation of the choice of these professionals determined in the career legislation itself.

The Teaching Career Plan was approved in its first version in 1998 and, since then, it has gone through three regulations, being the last one in 2012, aiming at respecting the principles of democratic management and the current legislation. The discussions on the career plan had the consultancy of teacher Milton Canuto, representative of the Confederação Nacional de Trabalhadores da Educação – CNTE [National Confederation of Education Workers], which supported the work from the discussions to the approval of the legislation.

The classification was based on length of service and qualification, also considering the workload, and was supported by a permanent commission to monitor the plan, taking care to adjust teachers’ salaries and avoiding losses to the professionals. With this classification criteria, salary distortions hardly ever happened, avoiding dissatisfaction among these professionals as it happened in São José dos Pinhais, where salary was the only criterion used.

The entry in the Piraquara education system is possible with a course called normal, which is a high-school level teacher preparation course, with a starting salary of R$ 1,067.00 (2016) for a 20-hour workload. The starting salary for a teacher with higher education is R$ 1,822.43 (2016). Therefore, considering the same workload and education level, the starting salaries in Piraquara are almost 20% lower than in São José dos Pinhais.

Besides this general context, to contextualize the perception of the teachers interviewed about their work conditions, it is necessary to systematize the elements present in the Teaching Career Plan in the period that the survey4was carried out.

Table 1 – Analysis of the Teaching Career Legislation, São José dos Pinhais and Piraquara, 2017.

| Themes | Subthemes | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal Public Servants of São José dos Pinhais Statute Act 525\2004 | Teaching professionals Statute Act 1.192\2012 | |||

| Qualification | Initial Education | Entry | Public Examination | Public Examination |

| Degree | Higher education | High-School | ||

| Continuing Education | Qualification leave | At the principal’s will | It is provided for in the legislation, but it defines the need for its own regulation. | |

| Working conditions | Number of Students | Not defined | Not defined | |

| Workload | 20 hours | 20 hours | ||

| Lesson planning | 33%* | 35%** | ||

| Health of the worker | It defines that there should be health prevention programs. | It defines regulations for changes in work activities. | ||

| Work unit | Assigned to municipal department of education. | Assigned to education units and there are criteria for this element. | ||

| Remuneration | Salary | |||

| Progression | ||||

| Composition of the remuneration | ||||

| Other information: | ||||

Source: Grochoska (2017)

* The implementation was gradual, starting in 2015

** Starting in 2016 (the implementation was gradual).

The initial finding is that there is already difference in the nature and, therefore, in the denomination of the laws in the two municipalities. In general, Piraquara’s career plan seems to potentially have more elements related to the valuation of teachers, in particular, it makes more reference to the conditions provided for under the national legislation, such as the floor salary, a monitoring commission, the high school level entry and a higher number of lesson planning hours. The same plan also offers several regulations on how, for example, assignment, performance assessment, change on work activities, increase of workload, will happen, elements that are not covered in the legislation of São José dos Pinhais.

In terms of the law, it can be said that Piraquara has a career plan that can potentially value professionals more than the one proposed in São José dos Pinhais. With this scenario in mind, we can move on to the results of the survey.

The survey: who are the teachers of both municipal systems?

In order to present the results of the research, the design we propose here starts with a presentation of the teachers in both education systems, considering the categories: age, length of service, workload and number of students per teacher. After that, we will direct the debate to data specifically related to the elements that provide quality of life in both municipalities. Finally, our choice was to identify specifically who are those teachers, in both municipalities, that indicate that they have quality of life, allowing an understanding into what objective elements compose this subjective representation of quality of life and teacher valuation. It should also be noted that the questionnaires were applied in 2014, in São José dos Pinhais, and in 2017, in Piraquara.

Table 1 presents specific data about the teachers’ age in both education systems. Analyzing the representation of quality of life, it was observed that age is a meaningful element since these representations vary depending on the teachers being younger or older, which serves as a basis for other necessary crossings, such as, for example, age and length of service.

Table 1 – Age range of the teachers in the municipal education systems of São José dos Pinhais and Piraquara

| Age range | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 25 | 3 | 1,1% | 22 | 12,4% |

| 26 to 35 | 79 | 27,8% | 53 | 29,9% |

| 36 to 45 | 126 | 44,4% | 64 | 36,2% |

| 46 to 55 | 61 | 21,5% | 34 | 19,2% |

| More than 56 | 15 | 21,5% | 4 | 2,3% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In both school systems, the number of teachers between 36 and 45 years of age is greater. However, in São José dos Pinhais, the number of younger teachers is significantly lower than in Piraquara. This fact can influence the perceptions of quality of life in each context, considering that older teachers can have more health problems, for example, in contrast with younger teachers, whose health conditions are normally more stable.

The item age, when crossed with length of service, shows more objectively an important difference between the two school systems, characterizing the group of teachers that work in São José dos Pinhais and in Piraquara. It is noticeable that in Piraquara there is a group of teachers that is much younger, and in São José dos Pinhais, teachers who are older and have been longer in this career, as shown in the table below.

Table 2 – Career length in both education systems

| How long have you been a teacher? | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am on probational period | 30 | 10,6% | 25 | 14,5% |

| 4 to 10 years | 65 | 22,9% | 75 | 43,6% |

| 11 to 15 years | 35 | 12,3% | 17 | 9,9% |

| 16 to 20 years | 51 | 18,0% | 23 | 13,4% |

| More than 20 years | 84 | 29,6% | 27 | 15,7% |

| I am about to retire | 19 | 6,7% | 5 | 2,9% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

Just as in the analysis of age, São José dos Pinhais has a larger number of teachers who have been working for more than 15 years (54%) in the municipal education system, while in Piraquara, most of its teachers (68%) have been working for less than 15 years.

Young age and short length of service (Piraquara) might represent other conditions of perception of quality of life. For example, since younger teachers do not usually have kids (therefore, there is not as much need of dedication to the family), the remuneration is not as necessary for expenses with others. This finding is reinforced in table 3, below:

Table 3 – Number of children per teacher in the municipal system.

| City | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| São José dos Pinhais Piraquara | |||||

| Number | Percentage | Percentage | Number | ||

| Do you have children? | no | 116 | 41.10% | 58 | 33.30% |

| 1 | 94 | 33.30% | 52 | 29.90% | |

| 2 | 54 | 19.10% | 52 | 29.90% | |

| 3 | 16 | 5.70% | 12 | 6.90% | |

| More than 3 | 2 | 0.70% | 0 | 0.00% | |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

The table shows that, in both education systems, most teachers do not have children or have just one. Younger teachers with no kids might have different perceptions of quality of life compared to those who are older. In this sense, we conclude that the variable child is an important element in the representation of teachers’ quality of life.

Another important element to understand the aspects of quality of life is to identify the workload of the teachers in both school systems. In this respect, data shows that in both, São José dos Pinhais or Piraquara, most teachers have a workload of 40 hours. However, while in Piraquara there are more teachers with a 20-hour workload, in São José dos Pinhais there are more teachers with a 60-hour workload.

Table 4 – Teachers’ workload in São José dos Pinhais and Piraquara – 2017

| Workload | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 hours | 40 hours | 60 hours | ||

| Municipality | São José dos Pinhais | 13,02% | 79,22% | 6,33% |

| Piraquara | 16,94% | 81,35% | 1,69% | |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

Data shows that in both municipalities the perspective of a 40-hour workload is consolidating, unlike what happened in the previous decades in which most teachers worked 20 hours. In this sense, we can take as a hypothesis the fact that for teachers it is not a problem to work 40 hours nowadays, considering that most of them have this workload. Maybe, the issue to be discussed is how this number of hours is composed and what are the work conditions.

Another important element that composes the representation of quality of life is related to the specificities of teachers’ remuneration. In this study, the item remuneration emphasized specifically teachers’ basic salary, not considering bonuses, allowances or other benefits.

It is worth noting, however, that the way this question was raised in the questionnaire ended up making the comparison analysis more difficult, since the salary table of both municipalities is very different. In São José dos Pinhais, the variation happens in 25 levels of the career (from level 40 to level 65). In Piraquara’s table there are 136 levels with different salaries.

Another difficulty was that in Piraquara, due to the quantity of levels and categories, the questionnaire had an open question, which made the interpretation of the salaries very complex. Another factor is that some teachers did not answer in which level or category of their career they were in, maybe because they did not know it.

Faced with these challenges, it was decided to have the minimum salary of the year 2017 (R$ 880.00) as the reference to compare teachers’ salary data, and, in the case of Piraquara, deal with possible answers given in the questionnaire. In this scenario, it was possible to formulate the following tabulation:

Table 5 shows significant differences between the salaries in both education systems. One of them, in particular, is the fact that few teachers from Piraquara reach the same starting salaries of teachers in São José dos Pinhais. In view of this data, it is noticeable that São José dos Pinhais pays much better than Piraquara. In spite of being higher or lower, salaries are a highly representative aspect of teachers’ valuation and quality of life. This indicator will be further explored in the next analysis.

Table 5 – Teachers’ salary according to the minimum salary

| Salary | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | Correspondent salary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,5 minimum salary | 00.00 | 15.9% | Up to R$ 1,320.003 |

| From 1,5 minimum salary to 2 salaries | 00.00 | 8.8 | R$ 1,320.00 to R$ 1,760.00 |

| From 2 minimum salaries to 2,5 salaries | 00.00 | 18% | R$ 1,760.00 to R$ 2,200.00 |

| From 2,5 minimum salaries to 3 salaries | 61.60% | 3% | R$ 2,200.00 to R$ 2,640.00 |

| 3 minimum salaries or more | 38.4% | 0.6% | R$ 2,640.00 to R$ 3,520.00 |

| 4 minimum salaries or more | 00.00 | 00.00 | More than R$ 3,520.00 |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

As for working conditions, it was noted that Piraquara has a greater number of teachers with a smaller number of children in class. This indicator contributes to understand the amount of activities to be done at school: the more children, the more tests, notebooks to be checked, grades to be posted, and a more intense class dynamic.

Table 6 – Number of students per day for each teacher in the municipal system.

| Number of students per teacher per day | Municipality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Up to 20 | 42 | 15.3% | 55 | 32.4% |

| 21 to 40 | 72 | 26.2% | 43 | 25.3% |

| 41 to 60 | 75 | 27.3% | 41 | 24.1% |

| 61 to 80 | 26 | 9.5% | 11 | 6.5% |

| More than 81 students | 60 | 21.8% | 20 | 11.8% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

Considering this aspect, the number of students per teacher during the day can be an important element for the representation of teachers’ quality of life and might interfere in their health or on the time they dedicate to their family, leisure, sports or culture.

When all data is gathered in an analysis, we can say, in short, that in São José dos Pinhais there are older teachers, therefore, with more length of service, who have many students, however, their salaries are above the national average. On the other hand, in Piraquara, where there is a group of younger teachers, who, in average, have less students per day, in contrast with lower salaries. Having mentioned this, the next item aims to dive into specific aspects related to the quality of life of each teacher.

What do teachers say about quality of life?

After meeting the teachers of both education systems, the second step is to dive into specific analysis about representations of quality of life. The first general question tried to understand what elements the teachers consider important for a quality of life. In both municipalities, the teachers associated quality of life to good remuneration; leisure and culture; and time spent with the family. It is noteworthy that, in both cases, the variation between the elements highlighted in table 7, and which are related to quality of life, reach a similar percentage. However, in each education system, the most important elements that define quality of life are in a different order.

Table 7 – What are the elements related to quality of life?

| Municipality | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara |

|---|---|---|

| Good remuneration | 51.05% | 46.89% |

| Workload | 29.22% | 27.68% |

| Being healthy | 39.78% | 40.11% |

| Leisure and culture | 56.69% | 50.84% |

| Access to consumer goods | 9.85% | 17.7% |

| Time with the family | 51.76% | 58.19% |

| Access to housing | 13.38% | 14.12% |

| Professional satisfaction | 37.67% | 35.02% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

It is noteworthy that the three most frequent elements (good remuneration; leisure and culture; and time with family) are most likely related to the age profile discussed before and having or not children. It is important to highlight that both elements are interdependent with remuneration and workload, since, to have leisure and culture, you need time and good remuneration. From table 7 on, the questions asked to the teachers are in the tittle of the table.

Remuneration is an important element and was the main choice to define quality of life in both education systems. It is important to highlight that, even though the remuneration is different in each municipality (in some cases, almost half of the remuneration of the other municipality), both consider that quality of life is related to remuneration. In this sense, we reaffirm that teachers associate good remuneration to quality of life.

When asked if their profession provided them quality of life, most answered “partly”. However, in the Piraquara education system, there was a surprising number of teachers that answered positively.

Table 8 – Does your profession provide you with the conditions of quality of life?

| São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 11.61% | 26.55% |

| No | 7.04% | 7.34% |

| Partly | 80.28% | 66.10% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In São José dos Pinhais, quality of life is related to leisure and culture in a higher scale; in Piraquara, it is related to time with family. In Piraquara there are more teachers working 20 hours than in São José dos Pinhais. Therefore, that is why in Piraquara more teachers say that their profession provides quality of life, being the hypothesis that these teachers have a lower workload.

In line with the previous answer, in which a higher number of teachers in Piraquara stated that their profession provides them with quality of life, the following table reinforces teachers’ representation of how they feel in relation to their professional activity.

Table 9 – How do you feel about your workload?

| Municipality | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara |

|---|---|---|

| Happy | 16.54% | 22.03% |

| Satisfied with accomplishments | 16.19% | 27.68% |

| Tired | 51.40% | 46.89% |

| Exhausted | 10.56% | 9.03% |

| With no extra time | 33.09% | 20.33% |

| Irritated | 6.69% | 4.51% |

| Calm | 9.15% | 9.60% |

| Unhappy | 0.35% | 1.77% |

| Unmotivated | 7.04% | 7.90% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In the municipality of Piraquara, where there are more teachers with a lower workload, they feel happier and more satisfied with their accomplishments, in spite of feeling tired. So much so that, summing up the percentage of happy and satisfied teachers, the number obtained is higher than the number of those who feel tired.

This result is likely to be a consequence of the higher number of younger teachers with less length of service, who serve a smaller number of students per day. On the other hand, in São José dos Pinhais, the number of teachers with a higher workload is significant. Adding to this the fact that the teachers are older and have a higher length of service and assist a greater number of students.

It was observed, however, that even though the teachers of Piraquara show a more positive relation with their work, as it is a younger group that has less students in class, most of them said that, at some point, their health was affected.

The data in table 10 shows that in both education systems the number of teachers that at some point in their lives were ill due to their professional activity is high. This information indicates an important element for the valuation of teachers, which is thinking about health policies for these professionals. Both older and younger teachers have their health affected at some point.

Table 10 – Has your profession affected your health?

| Has your profession affected your health? | Municipality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| No | 70 | 25.2% | 47 | 27.2% |

| Yes | 51 | 18.3% | 40 | 23.1% |

| Sometimes | 157 | 56,5% | 86 | 49,7% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In the context of discussing remuneration and quality of life, and understanding retirement as a condition of valuation of teachers as a horizon of effective fulfillment of their professional trajectory (GOUVEIA, 2018), we aimed to identify what are teachers’ perception of this aspect.

Table 11 – Teachers’ perception of retirement

| How do you envision your retirement? | Municipality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| No answer | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 1.7% |

| I have never thought about my retirement | 22 | 7.8% | 13 | 7.5% |

| Good, with quality of life | 128 | 45.2% | 102 | 59.0% |

| Difficult, with low remuneration | 37 | 13.1% | 15 | 8.7% |

| Difficult, with health problems | 8 | 2.8% | 4 | 2.3% |

| Peaceful, I will travel a lot | 19 | 6.7% | 9 | 5.2% |

| Peaceful, going to cinemas, theaters and museums | 7 | 2.5% | 5 | 2.9% |

| I will continue working | 61 | 21.6% | 22 | 12.7% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

It is challenging, however, the fact that, even with non-positive statements about pay, health, how they feel at work, and differences in age and length of service, in both cases, a great number of professionals envision a retirement with quality of life. This indicator may be related to the fact that perception of retirement is associated to a distancing from school and the classroom.

In summary, data demonstrates that in Piraquara the teachers are more satisfied with their careers, even having much lower earnings, much lower than that in São José dos Pinhais. The elements that emerge as working conditions can be explanatory factors for this perception. In Piraquara, more teachers have a lower workload, with a smaller number of students per day, besides being a younger group. This indicator proposes a reflection that, throughout teachers’ career, there are some situations that intensify the work (OLIVEIRA, 2010) and contribute to a less positive perception of quality of life, as in the case of São José dos Pinhais.

In order to better understand this aspect, we selected the teachers who answered that “yes, the profession provides me with quality of life”, to analyze, in-depth, who were those happy and satisfied teachers, who were those who did not have their health affected; that said that their remuneration provided them with quality of life and those who envisioned a retirement with quality of life, that is, we decided to analyze what objective elements contribute to this perception and reflect on the challenges that this poses for public policies.

Initially, we thought of confronting the “yes” and the “no”, however, we noticed that the percentage of teachers who answered “no” was not significant, therefore, we prioritized those who indicated positive points.

The first step was to identify who were the teachers in both education systems that affirmed that the profession provided them with quality of life.

Grid 2 – Who are the teachers that answered that the profession provides them with quality of life?

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 | 36–45 |

| What is your length of service | More than 20 years | Between 4 and 10 years |

| Workload | 40 hours | 40 hours |

| Number of students per day | 41–60 students | Up to 20 students |

| Group that you teach | 1st grade | Pre-school |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

The elements that are similar in both municipalities are teachers’ age range, workload and the number of students in the groups (1st grade and pre-school), which is lower. This reinforces the importance of considering the number of students in education policies for teachers’ valuation concerning quality of life.

With regard to length of service, data suggests that those who have a positive perception of quality of life are at both ends of the career, in the beginning (Piraquara with a younger group) and at the end (São José dos Pinhais with an older group). Such fact can be sustained by the fact that the perception that those with recent career entries envision a trajectory ahead, have perception of development. On the other hand, those who have a 20-year length of service, already have a consolidated career, including in terms of earnings, since, they are likely to have acquired all possible benefits proposed in legislation.

In this regard, the construction of a career legislation that could be tracked (by the new teachers) and consolidated and concluded (for the older ones) becomes an important element for building the perception of teachers’ quality of life.

Many teachers, in special in the Piraquara’s education system, expressed that they feel happy and satisfied with their profession. Therefore, the grid below aims to identify who are these professionals.

Grid 3 – Who are the teachers that feel happy?

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 | 36–45 |

| What is your length of service | 4–10 years | 4–10 years |

| workload | 40 hours 67.4% 20 hours 30.4% | 40 hours 66.7% 20 hours 33.3% |

| Number of students per day | 21–40 students | 21–40 students |

| Group that you teach | 1st grade | 1st grade |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In this case, we can observe that length of service is lower among those teachers who feel happy, since they are in the beginning of their career. This element might demonstrate that, throughout their professional life, they face some situations that do not contribute to a feeling of happiness.

Most of the teachers who feel happy work 40 hours, therefore it is noteworthy the significant number of teachers who work only 20 hours in both education systems. In this respect, a lower workload represents a contribution for the positive feeling.

In the same way, we consider the lower number of students per day. It is important to highlight that in both municipalities the elements that indicate who are the teachers that are satisfied are the same, an important fact to think quality of life.

Grid 4 – Who are the teachers that have a feeling of accomplishment

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 (37%) 46–55 (37%) | 36–45 |

| What is your length of service | More than 20 years | 4–10 years |

| Workload | 40 hours | 40 hours |

| Number of students per day | 21– 40 students | 20 students |

| Group that you teach | 1st grade | Pre-school |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

The analysis of the teachers who have a feeling of accomplishment is practically the same as those who say that their profession provides them with quality of life, differing the perceptions about being “happy” and having a “feeling of accomplishment” regarding their length of service. Teachers with a feeling of accomplishment acknowledge the possibility or the consolidation of a career.

Even though there is a significant number of teachers who state that they are ill or that, at some point, their career affected their health, others say that they have never had their health affected by their profession.

Grid 5 – Who are the teachers that do not have their health affected by the work

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 | 36–45 |

| What is your length of service | More than 20 years | 4–10 years |

| Workload | 40 hours | 40 hours |

| Number of students per day | 41– 60 students | 20 students |

| Group that you teach | 1st grade | Pre-school |

Source: SURVEY São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

The difference between the two education systems is number of students per day and the length of service, which again falls between two extremes. Healthy teachers work with smaller groups (1st grade and pre-school) or are either consolidating or starting their career. In Piraquara, the perception that the profession does not affect health appears mainly among those that have a lower length of service, therefore, envision a trajectory ahead, while in São José dos Pinhais, the teachers with a longer length of service are the ones who said that the profession does not affect their health.

The following grid aims to show reflections concerning the teachers’ remuneration, identifying who are the teachers that affirm that the financial aspect provides them with quality of life.

Grid 6 – Who are the teachers that affirm that the financial aspect provides them with quality of life

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 | 36–45 |

| What is your length of service | More than 20 years | 4–10 years |

| Workload | 40 hours | 40 hours |

| Number of students per day | 41–60 students | 20 students |

| Qualification | Specialization | Specialization |

Fonte: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

The elements in this grid practically do not change. In São José dos Pinhais, however, the analysis is less complex, considering that the teachers who think their remuneration provides them with quality of life are the ones who probably have included their qualification (specialization) in their career plan and, due to their length of service, have higher remuneration.

As for Piraquara, where the career plan is applied normally, enabling teachers to move ahead in their career as they finish their specialization, the hypothesis is that they are younger, unlike in São José dos Pinhais, where for teachers to progress it is necessary to wait at least two years.

Thus, in Piraquara, we have younger teachers earning more due to their qualifications. We can say that the possibility of a career that promotes advances creates expectations on the part of the teachers regarding the representation of valuation and quality of life. In São José dos Pinhais, on the other hand, teachers have a negative representation of teacher valuation since the career makes moving ahead difficult.

Grid 7 – Who are the teachers that envision a retirement with quality of life

| QUESTION | SÃO JOSÉ DOS PINHAIS | PIRAQUARA |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 36–45 | 18–25 |

| What is your length of service | More than 20 years | 4–10 years |

| Workload | 40 hours | 40 hours |

| What is quality of life related to? | Time with family | Time with family |

| Does your profession affect your health? | No (29.3%) Yes (18.7%) | No (24.8%) Yes (20.8%) |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

In São José dos Pinhais, where quality of life is related to leisure and culture, even having better earnings than in Piraquara, the perception of retirement is linked to better remuneration. Piraquara, on the other hand, indicates health care as an important factor, which can be related to the hypothesis that there is a larger number of teachers that say that their work affects their health. It is noteworthy, however, to observe that, in both municipalities, in spite of the different economic conditions, teachers’ perception of quality of life vary very little, relating to elements that indicate contexts focused on remuneration and workload.

Table 13 – What needs to be changed for a better quality of life in your retirement?

| Municipality | São José dos Pinhais | Piraquara |

|---|---|---|

| Nothing | 0.70% | 2.25% |

| Remuneration | 61.26% | 48.58% |

| Health care | 49.29% | 54.80% |

| Reduced workload | 35.56% | 26.55% |

| Change profession | 4.22% | 1.12% |

| Time with family | 19.71% | 22.03% |

| Work more to save money | 7.04% | 0% |

Source: Survey São José dos Pinhais (2014), Piraquara (2017).

When planning retirement, few teachers, even those who feel happy, think there is nothing to change. The order of demand for valuation seems to be related to problems faced in each education system and deals with objective and subjective matters. Especially in relation to remuneration, even higher earnings in São José dos Pinhais do not resolve the perception of devaluation. It calls the attention that in both cases the prospect of continuing in the profession, allows us to reflect that quality of life is a major issue to avoid teacher turnover.

Final Considerations

The confrontation of data between the municipalities of São José dos Pinhais and Piraquara brings many reflections concerning the elements of valuation, career and quality of life of primary school.

The first is that the perception of valuation is related to a career that enables remunerative growth and the valuation of qualifications. Piraquara has a career plan that is more favorable to valuation elements, unlike São José dos Pinhais that has already implemented a plan, which, in the qualification process, caused great remunerative distortions not resolved throughout its trajectory. Along with this perspective, data from Piraquara shows teachers with a more positive view of their career and quality of life, in spite of having lower earnings than those in São José dos Pinhais because they are given the opportunity to advance in their career, enabling recognition for their qualifications and merit.

Therefore, a well-structured career plan, which enables an increase in earnings and valuation concerning qualification; that has clear and objective criteria in all processes related to qualification, assignments, work contract, is essential for the positive representation of teachers’ quality of life and creates a perception that they are being valued. A career plan that does not allow advances creates vague criteria, enabling biased sponsorship, resulting in a feeling of devaluation and unsatisfaction among the professionals.

A career plan is essential; however, an important element is a good starting salary in the beginning of the career. Let us have a look at Piraquara, which has a young group in terms of age and length of service and São José dos Pinhais, with a group that is older concerning the aspects aforementioned. This context can be linked to the fact that, to attract professionals to public examinations, the starting salary is what attracts them, also constituting an important element for their career fixation in that municipality. Even with an attractive career, the starting salary in Piraquara is much lower than in São José dos Pinhais. This means that teachers in Piraquara, who have gone through public examinations, will migrate to São José dos Pinhais whenever they have the opportunity since the starting salary is higher. This hypothesis justifies the fact that in Piraquara the teachers are much younger than in São José dos Pinhais, where it is unlikely that teachers will leave, since it has one of the best starting salaries of the Metropolitan Region of Curitiba. However, these teachers remain and, since there is not a career that enables more access to valuation elements, they feel less satisfied. Therefore, a good starting salary is essential for teachers to remain in the municipality.

Another issue is that in both education systems, in spite of the different salaries, the perception of remuneration and quality of life varies little, that is, even in the municipality with better remuneration, there is an indication that the earnings are still low. This argument justifies the need for matching teachers’ salaries with other higher education professional categories.

Something that calls the attention is that, even though a higher number of teachers in Piraquara work 20 hours per week, the idea that this could represent a better quality of life is not true, since the 40-hour workload does not seem to be a problem for teachers. Most of those who said they had quality of life, were happy and felt satisfied had a 40-hour workload. Therefore, besides the workload, it is more important to highlight the elements that compose the day-by-day scenario of development of their work, such as, for example, the number of students they have daily.

This element outstands in most data: in both municipalities, teachers with more quality of life work with smaller groups (1st grade and pre-school groups) and, consequently, have a lower number of students daily; generating a smaller workload, producing benefits in the life of the teacher, on the personal and professional level. Therefore, it is important to regulate the number of children in public schools.

In conclusion, the economic conditions of the municipalities are not the decisive element for the representation of the teachers’ valuation, most decisive is the way valuation policy is designed in these spaces, that is, if they are transparent, objective, of fast implementation, have the improvement of teachers’ work as their basis and acknowledge teachers’ qualifications. Even though Piraquara has many financial difficulties, the effort of the local policies to assure the payment of the salary floor, acknowledge the qualifications, make the progressions, regulate criteria for the processes that happen in the education system and promote debates make teachers with such low salaries have the sensation of valuation and quality of life!

What is the challenge? São José dos Pinhais needs to implement, on the short term, a career plan that creates on teachers the perception of valuation. On the other hand, in Piraquara, it would be important to implement for these young teachers, in the medium run, a career that keeps them in the municipality’s education system.

Concerning the question if there are teachers with quality of life? We can say that there are still some, but some elements are essential for building these representations, such as those discussed previously, and, unfortunately, as data shows, these teachers are not the majority!

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.738, de 16 de julho de 2008. Regulamenta a alínea “e” do inciso III do caput do art. 60 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, para instituir o piso salarial profissional nacional para os profissionais do magistério público da educação básica. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11738.htm. Acesso em: 25 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Coisas ditas. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2002. [ Links ]

DARLING- HAMMOND, Linda. Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, Bruxelles, v. 40, n. 3, p. 291-309, 2017. DOI: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399. [ Links ]

FERREIRA Jr., Amarílio; BITTAR, Mariluce. A ditadura militar e a proletarização dos professores. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 27, n. 97, p. 1159-1179, 2006. [ Links ]

GROCHOSKA. Marcia Andreia. Políticas educacionais e a valorização do professor: carreira e qualidade de vida dos professores de educação básica do município de São José dos Pinhais/PR. 2015. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2015. [ Links ]

GROCHOSKA, Marcia Andreia. Existem professores com qualidade de vida? Reflexões sobre valorização e carreira do magistério na educação básica. Curitiba: UFPR, 2017. Relatório de pós-doutorado apresentado à Universidade Federal do Paraná. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Cidades e estados: São José dos Pinhais, Paraná. Brasília, DF: IBGE, 2010. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pr/sao-jose-dos-pinhais.html Acesso em: 27 set. 2020. [ Links ]

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Cidades e estados: Piraquara. Brasília, DF: IBGE, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pr/piraquara.html. Acesso em: 27 set. 2020. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse estatística da educação básica 2016. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2019. Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/sinopses-estatisticas-da-educacao-basica. Acesso em: 25 set. 2020. [ Links ]

LEFORT, Claude. A invenção democrática: os limites do totalitarismo. São Paulo: Civilização Brasileira, 1983. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, Antonio (org.). Os professores e a sua formação. 2. ed. Lisboa: Dom Quixote, 1995. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. Os trabalhadores docentes e a construção política da profissão docente no Brasil. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. esp. 1, p. 17-36, 2010. [ Links ]

4- The survey was developed by one of the authors during her PhD (GROCHOSKA, 2015), focusing on aspects related to the valuation, career and quality of life for a group of teachers statistically representative of the municipal education system of São José dos Pinhais and was replicated in Piraquara. In São José dos Pinhais, the questionnaire was applied to 319 teachers and 284 answered them, and, in Piraquara, 285 questionnaires were applied, being 77 filled out. In both cases, the samples are representative of the respective population of teachers.

Received: January 25, 2019; Accepted: October 01, 2019

texto em

texto em