Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 26-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046217820

SECTION: ARTICLES

University Collectives and the Detachment Discourse away from the Parliamentary Politics 1

2- Universidade Federal do Piauí (UFPI), Teresina, Piauí, Brasil. Contato: oliviacperez@yahoo.com.br.

3- Universidade Estadual do Piauí (UESPI), Teresina, Piauí, Brasil. Contato: bmellosouza@yahoo.com.br.

The first objective of this work is to present data and the discourse of university collectives. For such, sixteen qualitative interviews were carried out with all university collectives from the city of Teresina, state of Piauí, Brazil, as well as analyses of Facebook posts of 170 Brazilian university collectives. After critical analysis of these data, autonomy and novelty issues of these collectives were discussed, sometimes claimed by them, other times assigned to them by the literature. Empirical results show a discoursive distancing of collectives as regards parliamentary and party politics. For understanding such discourses, this work recalls data from Latinobarómetro on the trust in the Congress and political parties among Brazilian young students. In order to understand the increase of distrust in state politics, reflections were made on the consequences of neoliberal capitalism. These allow us to move forward in comprehending the discourses of young university students involved in political organizations, not losing sight of these positions as regards broader social and theoretical contexts.

Key words: Collectives; Social Movements; Youth; Political Participation

O primeiro objetivo do trabalho é apresentar dados e o discurso dos coletivos universitários. Para tanto, foram realizadas dezesseis entrevistas qualitativas com todos os coletivos universitários da cidade de Teresina/PI, bem como análises das postagens de 170 coletivos universitários brasileiros com páginas na rede social digital Facebook. Após a análise crítica desses dados, problematizam-se a autonomia e as novidades dos coletivos, por vezes reclamadas por eles, por vezes atribuídas pela literatura. Os resultados empíricos mostram um distanciamento discursivo dos coletivos em relação à política partidária e parlamentar. Para entender tais discursos, o trabalho retoma dados do Latinobarômetro acerca da confiança no Congresso e nos partidos entre jovens estudantes brasileiros. A fim de se entender o aumento da desconfiança na política estatal, foram retomadas reflexões acerca das consequências do capitalismo neoliberal. As reflexões apresentadas permitem avançar na compreensão dos discursos de jovens universitários envolvidos em organizações políticas, sem perder de vista a relação desses posicionamentos com contextos sociais e teóricos mais amplos.

Palavras-Chave: Coletivos; Movimentos Sociais; Juventude; Participação Política

Introduction

This article is focused on the practices and discourses of university collectives made up of university students who develop their actions chiefly in these places.

Although a widespread nomenclature, few are the studies dealing specifically with collectives. The existing works point out some of their characteristics, e.g., informality, multiple and opportune agendas, horizontality, fluidity and presence in digital media ( BORELLI; ABOBOREIRA, 2011 ; MAIA, 2013 ; GOHN, 2017 ). According to Maia (2013) , what distinguishes the collective from the other movements is the fact that it does not have a permanent agenda; it may add multiple demands so that priority questions be defined through recurrent debates.

In order to better comprehend this type of political organization, this work initially aims to exhibit data on the collectives composed of young university students and their opinions concerning politics and parliamentary institutions.

Aiming to name collectives and other organizations that took up the streets in June 2013 in Brazil, or who attended Occupy Wall Street (protest movement against economic and social inequality established in 2011, in New York), scholars have been using the term newest social movements ( DAY, 2005 ; AUGUSTO; ROSA; RESENDE, 2016; GOHN, 2017 , 2018 ). The newest social movements would be plural, autonomous, horizontal and nonpartisan (AUGUSTO; ROSA; RESENDE, 2016), characteristics which would move them away from other institutionalized structures ( GOHN, 2017 ).

Both autonomy and novelty assigned to collectives are discussed herein. Despite the defense that they are not novel and autonomous organizations, collectives reproduce this discourse so as to move away from the parliamentary political activity. In order to comprehend this discourse, data from the Latinobarómetro survey are reported upon, which contain data on the trust of young Brazilian students in political institutions, e.g., the Congress and political parties.

Likewise, for comprehending the disinterest in state institutions, some reflections from Dardot and Laval (2016) are analyzed; these authors explain how neoliberalism alters all dimensions of human existence, imposing its ‘world-reason’ based upon competition and enabling the State, in this new world-reason, not to be seen as the accomplisher of the usual.

The research results enable a comprehension of the discourse of young university students engaged in political organizations, not disregarding the relationship of these discourses with broader social and theoretical contexts.

Methodological procedures

As collectives have been little systematized in the literature, at first the choice was to carry out an exploratory investigation through semi-structured interviews with members of all collectives from the city of Teresina, capital of the state of Piauí, in the Northeast of Brazil. For selection of research objects, the starting point was the self-definition of organizations as collectives. Locating them occurred through snowball sampling: the interviewees were requested to indicate other collectives, until the indications did not reveal any new names. Sixteen university collectives were identified, which worked within two public universities. The interviews were authorized by the researchers’ University Ethics Board.

Although the names of organizations and their members are not mentioned, as agreed with the interviewees, these are the characteristics of such collectives: twelve of them had from three to fifteen members; whereas the other four had around forty to fifty. This size was not theme-related. In nearly all collectives, only one member was interviewed, generally that appointed by other collectives. One collective chose to have all members interviewed.

Aiming to broaden the understanding of the phenomenon, all collectives possessing pages on the most widely-used digital social networking website at present in Brazil, Facebook, were investigated. For this article’s search, at first the words ‘collectives’ and ‘collective’ were typed into the search bar, in June 2017.

The database had 725 pages of collectives. From all these, 23% (170) were categorized as university collectives, as they worked within a university, hence their choice for being analysis objects of this article. The following information was analyzed, retrieved from the pages of all university collectives registered on Facebook: establishment year, composition, objective, major theme, contents of most recent posts (observed from the last five ones), statement that there is horizontality, autonomy, nonpartisanship, absence of bureaucracy/formalization, opinion on parliamentary politics, whether the collective criticizes and, if so, who. The making of the database occurred in June 2017 by a trained team for that task.

After data collection, the contents were analyzed so as to gather their practices and the relationship of university collectives with parliamentary politics. Content analysis is a widely-used technique in qualitative researches, with the purpose of verifying the occurrence frequency of certain constructions in a text, enabling the systematization of gathered information ( BARDIN, 2006 ).

In addition to exhibiting, this work discusses the novelty and autonomy discourse of collectives, sometimes claimed by them, other times assigned to them by the literature, demonstrating how much this type of organization is of long standing as regards other institutions, including parties and the State.

So as to contextualize the collectives’ discourse, data from Latinobarómetro are shown on the trust in the Congress and in political parties in the years 2010, 2013 and 2015. Latinobarómetro collects a broad study on public opinion in Latin America.4 The year of 2010 was the starting point for the temporal analysis, as the search on Facebook showed that the majority of collectives was created from 2012 to 2016, reaching a peak in 2016.

Even though the data collected are from Latin America, this research shows information of the survey applied by Latinobarómetro only in Brazil. Replies were collected from 1,204 Brazilians in 2010; 1,204 in 2013; whereas, in 2015, 1,250 Brazilians were interviewed.

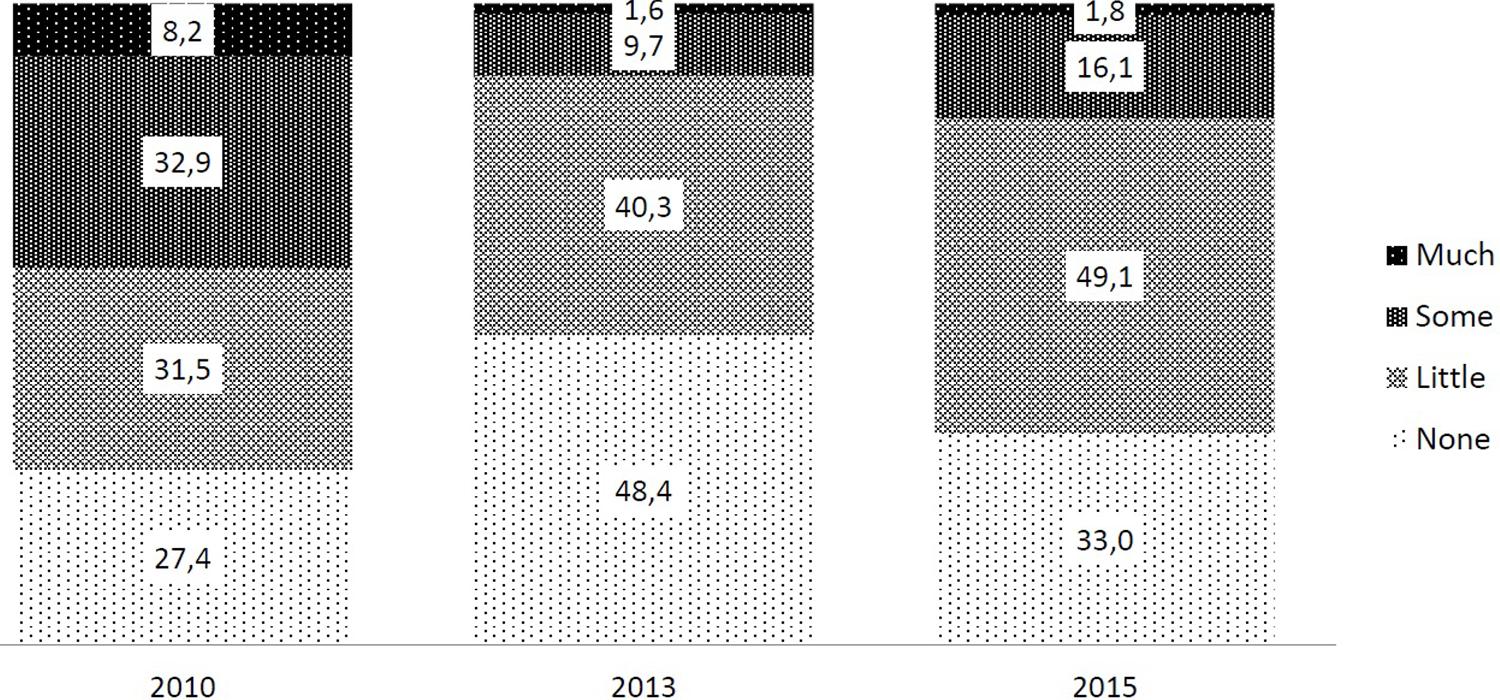

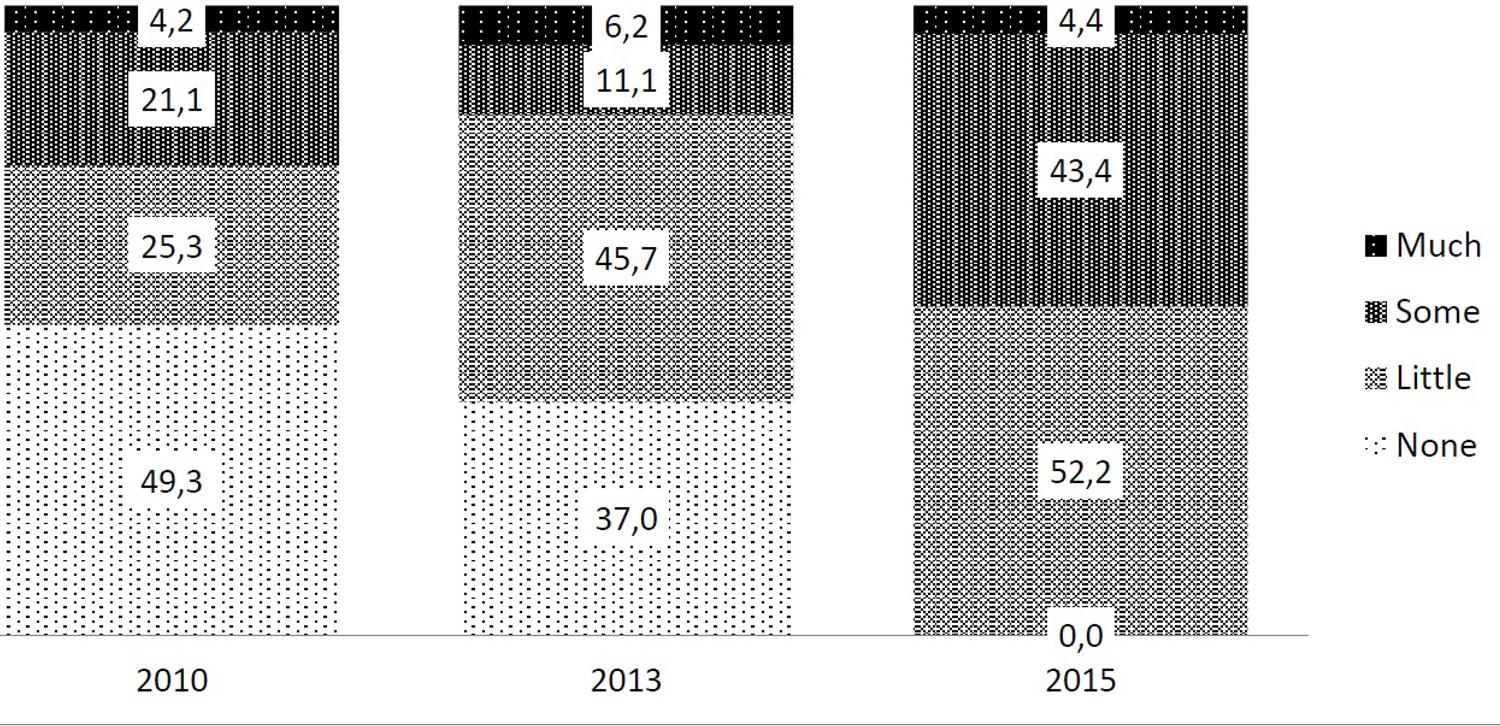

As the research focus are the young university students, replies from the young students (16-25 years old) were selected5 , but from those who have not finished academic studies yet. Although such criteria do not assure that these young adults are university students, it was the closest to a selection of young university students. The sub-sample of young students was made up of 152 interviewees in 2010, 172 in 2013 and 236 interviewees in 2015. The trust of these young adults in the Congress ( Graph 2 ) and in parties ( Graph 3 ) was systematized with more specificity. The graphs show how the discourse of collectives is related to distrust from the young adults in the Congress and in parties.

Source: The authors, from Latinobarómetro data (2010, 2013, 2015).

Graph 2 – Trust in the Congress among young students (%)

Source: The authors, from Latinobarómetro data (2010, 2013, 2015).

Graph 3 – Trust in the parties among young students (%).

As a way to analyze these data and aiming to broaden the understanding on distrust in the political and party institutions, this work then proceeds to resume certain reflections concerning the consequences of neoliberalism for the relationship of the subjects and the State.

The university collectives and the detachment discourse away from political parties and parliamentary politics

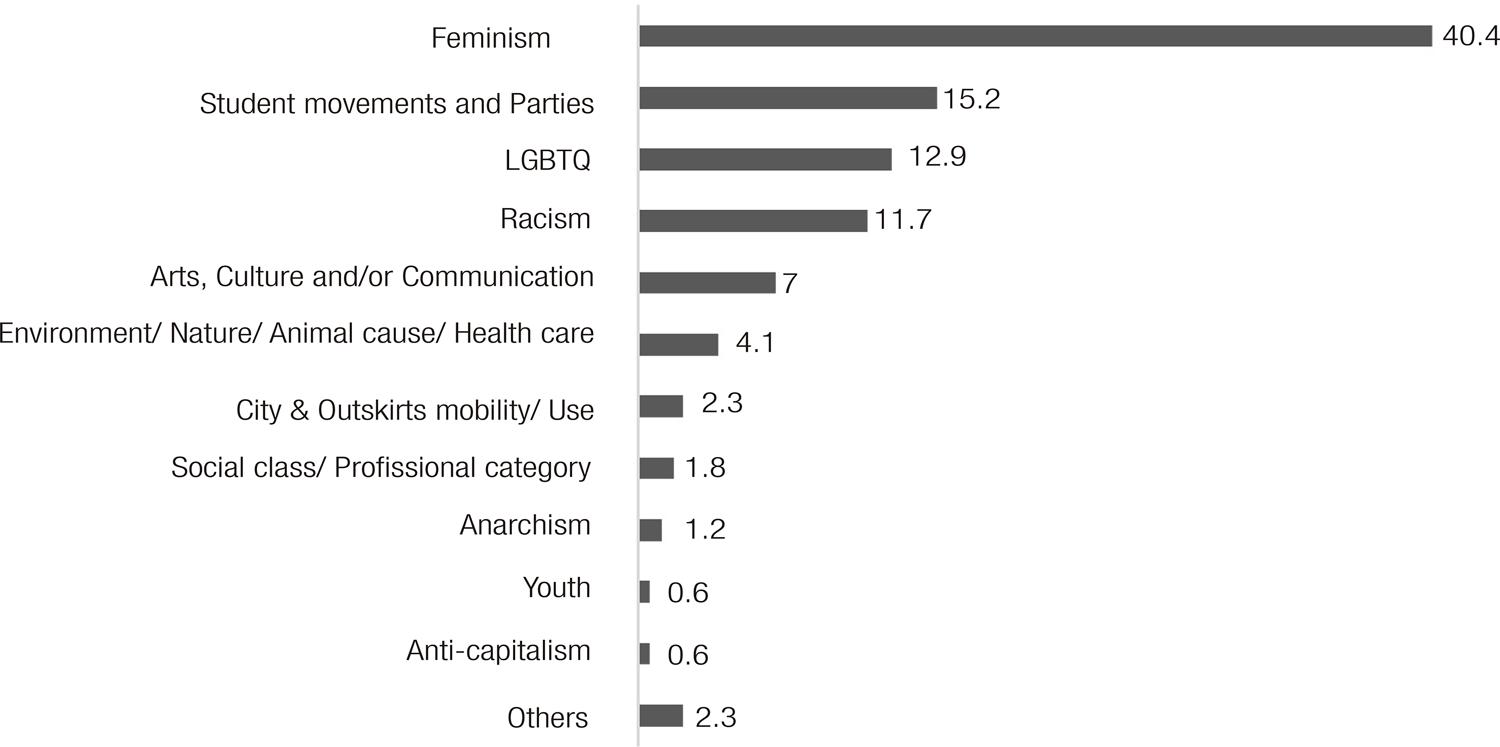

The university collectives are composed of Higher Education students who act within the university. They discuss and propose actions that deconstruct prejudices, encouraging thus the inclusion of groups facing more difficulties in accessing their rights, e.g., women and black people, as well as Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transgenders and Queers (or LGBTQ). Such discussions occur at their own universities/colleges and on digital social networking websites, such as Facebook. By accessing all pages of collectives formed by university students on Facebook (170), a systematization was accomplished with their major agendas in Graph 1:

The major agenda of university collectives is feminism (40.4%). The discussion concerning the category gender as a social construction and the struggle for women empowerment is one the most repercussive themes nowadays. Collectives also fight for well-known themes among students, such as the student agenda and political party organization (a theme of 15.2% of collectives). The student movements and political party-related groups are under the same category, as the student movement is mostly linked to political parties (in general, to the left in the political-ideological spectrum). Likewise, but conversely, university students involved with political parties also work in favor of students rights within universities/colleges. This is why dissociating the student movement from political orientation by means of information from Facebook is not possible (although student movements may have been moving away from political parties). In any case, from the sixteen interviews herein, the collectives supporting students rights were also connected to political parties.

The third most discussed theme among university collectives is the LGBTQ issue, focusing on combating discrimination that lesbians, gays, bisexuals, travesties and queers face within and without universities. Fourthly, 11.7% of university collectives discuss and fight racism. Collectives seek to call this debate upon themselves and demand the universities to recognize the color/race/ethnicity-related difficulties in Brazil, as well as inclusion and permanency policies of black students.

At a smaller proportion, 7% of collectives act in favor of the arts (theater, music and dance, for example); 4.1% of university collectives debate issues such as the environment, nature, the animal cause and healthcare access, as defined by themselves; 2.3% deal with city mobility; 1.8% are connected to labor unions and professional categories (and still define themselves as collectives); the anarchist agenda showed up in 1.2% of them and the anti-capitalist, in 0.6%.

These agendas are not isolated. One of the great novelties of collectives is the fight for more than one social cleavage — which leads to the creation of one black feminist collective, for example. The collectives discussing feminism add more than one agenda to their fights, which is perceived by the fact that their posts defend different cleavages from their main flags. The most common cases are the collectives adding, beyond their major agenda, the fight for the end of racial discrimination (23%), followed by the defense of rights for LGBTQ population (16.4%).

As for the creation of university collectives, the interviews with sixteen collectives from the city of Teresina, state of Piauí, revealed a discontentment of young adults concerning the absence of discussions on prejudice and rights for women, black and LGBTQ people at universities, hence the need for promoting debates and inclusion actions. The realization that the problem is the inaction regarding prejudice, right and inclusion-related issues also appear on their virtual pages. As per one of the pages searched, “the kickoff of the collective was the voice” to debate and combat these situations deemed unjust.

Although not shared by all university collectives, 3% of them declare on their Facebook pages the absence of hierarchies or leaderships in their organizations, as well as nonpartisanship. These features also show up in the interviews: more than half of the sixteen interviewees pointed out the absence of leadership in their decision-making and the detachment from political parties. The refusal discourse to political parties reveals anti-party and nonpartisan views.

The anti-party supporters refuse their own affiliation to political parties, as such institutions take away the individuals’ autonomy, hampering their thinking and acting freedoms. Therefore, one collective points out that “[...] we got no political party, we got nothing. So our place is for the people and that be better for us all”.

In turn, the nonpartisans admit members of the organization to be affiliated to parties, but party orientations must not stand out in the decision-making. For example, when one of the interviewees was asked whether members of the collective were part of any political party, he answered: “Man, if they are, this is an inner circle, but outside the association”. This means that the participants of that collective do not show off their party affiliations and this must not guide their decisions, even though affiliation is admitted.

Detachment from political parties can also be seen in one of the collective’s description from the Facebook page:

The Feminist Collective [...] came to light in 2012 through the initiative of students of the Federal University of Piauí […], who, realizing the lack of space and debate on women’s situation at the institution and so many other sexist situations to which we are daily exposed, started a chat/debate group to discuss women’s condition at the university (and all other related issues) under the feminist perspective. We are organized in a horizontal and self-managed manner, that is, nonhierarchical with no job assignment, only task assignment. Autonomous, the Collective is not affiliated to other party organizations, which does not exclude people from other areas to help us build the collective and, thus, present an open dialogue with any ideologies. We understand that the feminist fight is intersectional and necessary for denaturalizing, combating and overcoming the existing sexist relations in society. Therefore, our agenda is also for cross-sectional discussions of class and race.

The description of this collective is an example of various characteristics shown as typical of university collectives: the fight for feminism, the importance of the fight for other agendas besides the major one, the statement that the debates and decisions are horizontal and autonomous, and the detachment concerning political parties.

The detachment discourse against political parties also shows up when interviewees discuss what is to do politics: interviewee members of eight collectives reject the statement that they do politics. For example, when asked about the political practice of collectives, one of the interviewees replied: “No, we don’t mess with politics”.

The negative association that young people have with the term politics has been pointed out by Baquero, Baquero & Morais (2016), in the context of a research with young people from Porto Alegre-RS and Curitiba-PR. According to the research, youngsters correlate politics with expressions such as corruption, thievery and opportunism, whereas politicians are correlated with the terms alienation, corruption, falsehood and uselessness.

Politics is rejected because young people correlate it with party politics. Another example: when asked about the paradox of doing politics, but with no politics, an interviewee replied: “We talk about politics, yeah. But when we’re talking about party politics and supporting a party, no!”. Realize the associations herein to party politics; therefore, by rejecting politics, young people would be moving away from politics via parties in parliamentary institutions — these being sources of distrust. But it does not mean immobility; after all, according to one interviewee: “We don’t want any of these parties out there, but we’re fighting”.

Detachment from political parties would even assure more horizontal decisions, as party orientation would establish a hierarchy among members and their positions, as attested by part of the interviewees. In this sense, the collective would only be free and egalitarian if they decided independently concerning party guidelines. The same reason justifies the rejection to establishing declared leaderships, even knowing who they are: taking over leadership means going against the egalitarian character of collectives.

One of the interviewees points out the need for a direct political action, saying the following: “There’s another way we can build a plural form, independent, not depending on parties, not depending on those guys. There’s another path, a third path. Even not electoral, it’s a more direct way”. As reported by another study ( VOMMARO, 2015 ), collectives demand a direct democracy by rejecting intermediaries, hierarchies and leaders in the political practice.

By advocating this, the discourses of collectives recall theoretical debates on how democracy should include citizens into public decisions. The debate on the population inclusion directly into public decisions goes back to the direct Greek democracy, regime in which citizens would gather in assemblies to discuss and decide upon issues concerning the polis , even though not all were regarded citizens (excluded from this were women, foreigners and slaves). Jean Jacques Rousseau with his classical work The social contract ([1762] 2014) is a source of inspiration for various theories that advocate that the people themselves must author the laws to which they are subject, without the need for representation (cf. PATEMAN, 1992 ).

Besides the possibility of greater population inclusion into public decisions, within the collectives’ discourse there is also a concern with the decision-making process — reflection theme of deliberative democracy. As per the conception of deliberative democracy, having Habermas as a major author, elected representatives cannot make public decisions alone, nor citizens should only be included by means of another election: citizens must indispensably influence on how decisions are made. For this theory, decisions must be made after a wide discussion process in which all can take part equally. Opinions must be, additionally, justified so that a general agreement can be reached. Furthermore, the reformulation process of decisions must be continuous ( GUTMANN; THOMPSON, 2007 ).

According to part of the interviewees, contrary to parties and parliamentary institutions, which hinder people’s behavior by guiding their work through bureaucratic rules and through leadership authoritarian decisions, collectives enabled the participation of their members. From one of the interviewees:

There’s [sic] parties that instruct you so you have a way to express yourself more leadingly [sic]. But what we really have to do is to make this knowledge collective and make more people feel empowered to talk.

It is as if parties tainted discussions as they overlap their interests to those of the group. The ideal way of deciding, in accordance with the collectives, would be including all interested parties into some issue and decisions would come from egalitarian deliberation and free from external political party influences.

Problematizing the discourse of collectives

The literature on collectives, understood as newest social movements, regard them as new ways of political organization commenced at large mass meetings, e.g. Occupy Wall Street, in New York, or at those spreading throughout Brazil, last June 2013. Collectives would be new due to their contemporaneous character and some features marking them as different from old social movements or from more structured organizations, such as nongovernmental social movements and organizations. The latter would be formal, bureaucratic, hierarchical and impregnated with political party positions. Different from them, collectives would be autonomous and nonpartisan ( DAY, 2005 ; AUGUSTO; ROSA; RESENDE, 2016; GOHN, 2017 , 2018 ). The novelty idea, the autonomy and independence concerning political parties, reappears in the discourse of collectives, as we sought to show herein. Problematizing the discourse of collectives is necessary, however, and the categories assigned to them by the literature.

The novelty

Collectives are regarded as new ways of political organization, different from social movements, by their informal, punctual and fluid characteristics. In a recent book, Gohn (2017) analyzes three newest social movements created as of 2010: Free Fare Movement [ Passe Livre , in Portuguese], Come to the Street [ Vem Pra Rua , in Portuguese] and Free Brazil Movement [ Brasil Livre , in Portuguese]. The term newest social movements is used to distinguish their novelty concerning classic social movements (affiliated to the fight of working class and upended organizations) and the new social movements (which act with network identity agendas and at participation institutions).

The Canadian researcher Richard Day (2005) , for example, argues that movements rising after the 1980s (indigenous resistance movements, feminist organizations and anti-globalization activism) must be considered newest social movements, as they follow the logic of affinity and not hegemony. The projects of newest social movements would follow the affinity logic in the sense that they are rooted in autonomy and decolonization. For such, they develop new ways of self-organization that may work in parallel or as alternatives to the existing ways of social, political and economical organization. The logic of affinity was present in the libertarian anarchism as a refusal to the State and to hegemonic relationships, allowing thus each group to develop distinct sociability not obeying a common and only project ( DAY, 2005 ).

Novelty is pointed out by the collectives’ members, as verified from the interviews with sixteen university collectives from the city of Teresina, state of Piauí. According to one of the interviewees: “We’re different from everything out there. We want everything different, new”. The very term ‘collective’ recalls a distant novelty from the formalized, perennial and hierarchical organizations.

However, the nomenclature collective is not new, nor the organizations self-entitled as such. One of the most preeminent collectives, Combahee River, was a black feminist organization active in Boston, from 1974 to 1980, which drew attention to how much the white feminist movement did not include the needs of black women. In Brazil, the professor and activist Lélia Gonzalez founded, in 1983, with other black women, Nzinga, a Rio de Janeiro-based collective. Therefore, this is no novelty. Additionally, the feminist and anti-racist fights, typical of university collectives — as shown herein —, were already flags raised by older collectives.

Besides the novelty of being contemporaneous, collectives are considered new because they do not fit into the explanations on social movements; that is why they are called newest social movements. These would be horizontal, autonomous and nonpartisan ( DAY, 2005 ; AUGUSTO; ROSA; RESENDE, 2016; GOHN, 2017 ), which moves them away from classic social movements. These characteristics are also reported by collectives as they are self-defined as “[...] horizontal and self-managed, that is, nonhierarchical with no job assignment, only task assignment. Autonomous, the Collective is not affiliated to other party organizations [...]” (excerpt from a collective’s Facebook page).

By interpreting the irruption phenomena of the mid-2013 in Brazil and in the world with these criteria, there is a problem, however, in presupposing that the discourse or even some empirical characteristics of some organizations are valid for all universe of collectives. The idea of autonomous and nonpartisan movements starts chiefly from the analysis of Passe Livre (movement that led the cycle of protests started in June 2013, in Brazil) and collectives with an anarchist discourse. But protesters who took part of June Journeys were not only anarchist political organizations: the diversity of actors is one of the characteristics of June 2013. Therefore, assigning nonpartisanship or autonomy to all protesters is not possible based upon part of their discourse.

Secondly, characteristics such as horizontality, nonpartisanship and autonomy were also assigned to social movements of the 1960s and 1970s in Europe, and they became the new social movements. Melucci (1989) and Touraine (2006) , for example, explain that movements of that context expressed symbolic demands instead of those directly related to social class, major fight flag of classic social movements. As with collectives, the new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s fought for feminism and the end of racism.

In Brazil, the social movements sprung from the military dictatorship regime, especially in the 1970s, came to be known as the new social movements. From a referential study in this field ( SADER, 1988 ), the movements of that time brought forth collectives with agendas involving new more horizontal sociability patterns and aware of their rights. Different from pre-dictatorship regime social movements, the new social movements would be autonomous concerning the oppressor State as a feature and banner to fight for.

The disputes concerning categories denoting antinomies such as old vs. new or new vs. newest social movements have produced extensive discussions. Ruth Cardoso (1987) has explained that these disputes are moved by the researcher’s wager (who is related to the social context) on which organizations will be responsible for the social change. Doimo (1995) , complementarily, states that the literature on the 1970s’ social movements wagered on social change through civil society seizing back the State. In that context, social movements would be able to change social relations, thence the novelty and potentiality assigned to them.

Whereas in the current context, that of low trust in parliamentary institutions, the wager falls again to civil organizations. So as to reaffirm the importance of social actors, terms such as newest are coined, as well as characteristics recalling independence and capacity. However, these interpretations do not regard heterogeneity within organizations and among themselves, assigning to them excessive merits. This assignment of excessive merits makes studies in this field difficult, as they hinder analyses of this broad area (cf. GURZA LAVALLE, 2003 ).

Autonomy

Besides novelty, collectives are distinct from other political organizations, and even from social movements, due to autonomy. This would be decisive, especially to classify a social movement as newest, moving their practices closer to anarchism ( DAY, 2005 ).

However, noteworthy is that the meaning of autonomy varies. For social movements autonomy does not mean the absence of contact with the State, but they must be free to choose their agendas and strategies. In this case, autonomy refers to:

[...] the ability of some actor to maintain relationships with other actors (allies, supporters and antagonists) from some freedom or moral independence that enable them to define forms, rules and the objectives of interaction from their interests and values ( TATAGIBA, 2010 , p. 68).

Whereas autonomy for collectives has another meaning. From the description of a university collective holding a Facebook page, autonomy refers to the distance concerning political parties.

The collective is totally autonomous as regards political parties, and the issue of political parties does not concern us […], but people [...] have freedom for a political organization, so they can organize themselves into a party if they wish so; then there are some people organizing as a party, but these are different instances. We try our best to keep our autonomy before these other organizations.

The same meaning of autonomy was revealed from the interviews with university collectives from Teresina, state of Piauí. According to the opinion of part of them, political parties guide their members’ decisions, which compromises the possibility of genuine active participation. Members need to, collectively, be able to decide their positions with no external interference from parties. This does not mean that members may not be affiliated to parties or that they will not be related with the State, but that parties must not determine decisions of the collectives. That is, if in anarchism autonomy refers to a distance from the State — and this autonomy would be a characteristic of the newest social movements ( DAY, 2005 ; AUGUSTO, ROSA; RESENDE, 2016; GOHN, 2017 ) —, for collectives, autonomy means distancing from political parties.

But this distancing does not always occur in practice. The name collective is even linked to groups belonging to the inner circle of some political parties. As examples, from among the major trends of the political party called Socialismo e Liberdade [Socialism and Freedom] (PSOL, which is a leftist party) these collectives are found: Resistência Socialista [Socialist Resistance], Primeiro de Maio [May 1st] (trend from another collective called Rosa do Povo [People’s Rose]), Rosa Zumbi and Liberdade Socialista [Socialist Freedom] (CSL), which merged with Socialismo Revolucionário [Revolutionary Socialism] to create the current Liberdade, Socialismo e Revolução [Freedom, Socialism and Revolution].

On the other hand, half of the university collectives interviewed in Teresina is affiliated to political parties. Still, instead of adopting the name of the acronyms to which they are affiliated or entities they belong to, these collectives prefer to call themselves thusly. Additionally, from the names of half of collectives interviewed herein, no recognition as to party affiliation was possible. Asking more than once was necessary during interviews, to inquire whether collectives were affiliated to any party whatsoever. The relationship with political parties, which has already been a politization show, today is hidden within collectives.

One of the problems of refusing this possible dirigisme of parties lies in the fact that it presupposes some neutrality, while a source of genuine decisions, as if free from external opinions to the collective, the subjects were able to better debate and decide. But neutrality is impossible: nobody opines without external influences. If in the past this seemed to be an outdated debate by Social Sciences, today the idea of independence has come to rise as a positive position, as well as among social-political organizations, e.g. collectives.

The low trust in parliamentary institutions

Collectives are shown and regarded as novelties as compared to other forms of political organization, specifically due to the distance they keep from parliamentary institutions. Nevertheless, besides reproducing such ideas, we should understand them. The low trust in parliamentary institutions, e.g. the Congress, is not exclusive from collectives: it permeates the opinion of Brazilian young students, as per data from Latinobarómetro exhibited in Graph 2 .

Data from Graph 2 summarize the trust of Brazilian young students (16 to 25 years old who attend school, but have not completed their studies yet) concerning the Congress. From the graph, 27.4% of them did not have any level of trust in the Congress in 2010, while 8.2% completely trusted in that institution. The year of 2013 expresses this distrust growth accurately: 48.4% of young students (almost twofold of 2010) did not have any level of trust in the Congress, while only 1.6% had some trust in it. In 2015, the percentage of those who had little trust in the Congress increased (49.1%). The data on the trust in the Congress are a portrait of the youngsters’ perception concerning parliamentary politics.

Similar results may be seen by analyzing the trust of Brazilian young students in political parties, according to data from Graph 3 .

Young students trust more in political parties than in the Congress, maybe due to being closer to political associations. Data from Graph 3 exhibit a larger variation among those with some trust in parties: the index decreased substantially in 2013 (11.1%), with a significant increase in 2015 (43.4%). Notable from the Graph is the fact that no one expressed that they did not have any level of trust at all in parties in 2015, very different from 2010, in which 49.3% of young university students manifested no trust in parties, or from 2013, with 37% of answers assigning no trust in parties.

Data from Latinobarómetro also show how in 2013 the distrust in parties and in the Congress was greater than other periods. This is explained by the large protest movements throughout the streets of Brazil in 2013. The wave of protest movements, or the cycle of protests started in June 2013, was sparked by the fight for a better public transportation, but protests gathered other flags: right to the city, defense of social and labor rights, improvement of public services, corruption fight, fight against ethnic-racial, gender and sex orientation discrimination etc. All these demands were present in June, but some of them stood out from one protest to another.

Related to this widespread dissatisfaction, the 2013 protest movements expressed the distancing from parliamentary politics: “[...] the masses on the streets affirm the desire of political exercise without institutional mediation [...]” ( TATAGIBA, 2014 , p. 41). The distancing concerning parties marked the movements of that time, with some protesters markedly coming to blows ( TATAGIBA, 2014 ). Following these positions, collectives sprouted in the 2013 Journeys.

On that subject, the growth of nonpartisan collectives, discoursively away from parliamentary and party politics, could point to the content and the consequences of these movements. According to Vommaro (2015 , p. 62):

[...] for beyond the surprise that these protest movements may have caused to some sectors and analysts, if we focus on what had been happening among youngster collectives in Brazil in the past, various elements come to rise that may contribute to their understanding.

In other words, the growth of collectives calling themselves nonpartisan have already expressed discontentment with politics and politicians, one of their mottoes. This dissatisfaction is also related to the economic deterioration process in the country. Put differently, while in the economic prosperity years of this century’s first decade there was an environment of greater optimism concerning the democratic regime, with the rise of economic crises and low popularity of governments related to them, this climate of optimism rapidly changed into pessimism and dissatisfaction ( BAQUERO; GONZÁLEZ, 2016 ). The dissatisfaction climate, therefore, is not exclusive of young Brazilians and it is in a broader context of economic, political and institutional crisis in the country.

The loss of trust in the State is related to the political economic orientation called neoliberalism. Gentili and Sader (1995) explain the inception of this neoliberal current. For these authors, neoliberalism was born soon after World War II, in Europe and North America, where capitalism was supreme. It was a vehement theoretical and political reaction against the interventionist State and the social welfare. For this doctrine, competition is responsible for wealth distribution. Draibe (1989) also attributes to the State crisis in the 1980s the surge for the discussion on diminishing the State in social policies and service transfer to civil society organizations. The author calls this process privatization , in a broad sense; this argument would be defended both by the left, when they propose a larger participation of the nonprofit and nongovernmental sector, and by the right, when they propose the State reduction in social policies.

But the consequences of neoliberalism do not reach only the economic and social sphere, they also impact the individuals’ subjectivity and their conceptions about the State. According to Dardot and Laval (2006), the neoliberal rationality is based upon unrestricted competition in all areas. It acquires a pervasive dimension encompassing, in addition to the State, all human existence, translating into a world-reason. The neoliberal rationality would be a “set of discourses, practices and apparatuses that determine a new mode of government of human beings in accordance with the universal principle of competition” (DARDOT; LAVAL, 2006, p. 17).

Withdrawing the State and seeking the services in private media lead the individual to look down on state policy. Individuals start to share the conception of meritocracy as a way of ensuring survival, ceasing to identify state policy as a possibility of assurance of rights. More than that: as a consequence of the neoliberal world-reason, the very idea of politics is emptied.

The June Journeys expressed this discontentment concerning assurance of rights via State and, with that, they criticized the very state politics. From among collectives surveyed, all leftist, the disbelief of young students concerning politics is related to their disappointment at the Workers Party (PT). There had been a general belief that PT would structurally reform the country in favor of the workers’ interests, and this did not come to pass as expected from part of the left. In this sense, the criticism to PT is common among collectives. From one interviewee: “...[the] PT, it was that party we all know, we kind of felt betrayed by this government”. The Workers Party would have moved away from its allies and chosen to form new alliances with ideologically distant parties. For another interviewee, PT “[...] did not call the people to fight against the coup and against the current situation, and by the way there’s [sic] even alliances within higher sectors of the Workers Party to other parties”. Notable is that the repulsion discourse against PT, which had been an agenda of street manifestations in the last years, is also replicated by collectives – which could not even be different, since they are part of the same political context.

This discourse is in part explained, as neither leftist nor rightist governments were able to change the neoliberal State, which has a much more general function than reducing the State in economy. The State is no more a part of the collective life, the economy and the political power: its function is now to manage private services consumed by the subjects, now customers ( DARDOT; LAVAL, 2016 ). Additionally, from these authors, such consequences are felt by rightist and leftist governments, as neoliberalism is much more than a political party ideology: it has become a world-reason reaching all human existence.

Not fortuitously the protests of June 2013 and the following cycle in 2014, 2015 and 2016 expressed a discontentment with fiscal austerity measures promoted by President Dilma Rousseff administration, who was reelected in 2014. Youngsters realized that even leftist governments were not able to assure rights. Thence their disbelief in state policy institutions, e.g. the Congress and political parties, increased exactly at these times, as per Graphs 2 and 3 .

The discredit brought into parties, even leftist ones, is not from now and does not occur only in Brazil. Protests throughout the world occurred in 2011, with anti-capitalist, anti-globalization, anti-corruption flags and against autocratic political regimes. The wave of protests in 2011 started in Northern Africa, where dictatorships were overturned in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. Then, it spread to Europe, with sit-ins and strikes in Spain and Greece, and revolt in the suburbs of London. It emerged in Chile and occupied Wall Street, in the USA ( CARNEIRO, 2012 , p. 7-8). After these protest movements and the various criticism to the political system, many regions elected conservative politicians, such as Donald Trump, elected in 2017 in the United States, or Jair Bolsonaro, in 2018 in Brazil.

Although the work of Dardot and Laval The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society was released in Brazil in 2016, it was originally published in France in 2009, that is, during the gestation of the world financial crisis of 2008, from a time and a place where you could see the consequences of neoliberalism. According to the authors, the crisis was not enough to make neoliberalism vanish. On the contrary, it was an opportunity for the dominant classes to strengthen the nature of the social and political project of neoliberalism. In addition to political consequences, social mobilizations aiming at deep changes are weakened by the neoliberal system, as the individuals compete in many existential spheres. Individualism and social egotism, which deny solidarity, may open into – still according to Dardot and Laval (2016) – reactionary or even neofascist movements.

Concluding remarks

University collectives have been gaining ground at universities and on digital social networking websites based upon the gathering of people around a common goal. Their discourse expresses the novelty and the distancing concerning party parliamentary politics.

The novelty carried by the term collectives serves to move them away from parliamentary politics, regarded as old, restricted and inefficient. However, it is not possible to state that they are indeed newest and away from parliamentary politics. The old and the new live together, as reality is multiple and social movements are diverse and contradictory. Furthermore, contradiction is inherent to social movements and must not nullify their study. Collectives are similar to the new social movements as defined by Melucci (1989): heterogeneous, intertwining past heritages and contemporaneous flags. Additionally, related to one another, social movements lend one another ideas, people, rhetoric and action models (TILLY, 2010).

The novelty discourse and distancing concerning politics are related to the low trust in parliamentary institutions among young students and the general population. This low trust was expressed and fed by the cycle of protests begun in June 2013, in Brazil. The distance between collectives and traditional political organizations would comply with society’s expectations as to the way of societal organization. In a context of distrust concerning political parties and parliamentary institutions, collectives rise as more genuine ways of organization.

The distancing of young students as regards parliamentary politics, including parties and parliamentary institutions, may entail the strengthening of democratic institutions. Parliamentary institutions could be improved by the struggle of social movements, especially of young university students. However, when activists stand away from these institutions, they contribute to decrease the chances of an actual change. Inversely, distrust in parties and the Congress may increase the possibility of breaking away the population and these two central institutions for democracy.

The anti-partisan or nonpartisan positions may, additionally, boost projects such as the Nonpartisan School Movement [ Escola sem Partido , in Portuguese] and so many others that seek to ‘remove from the picture’ the ideological discussions and political practices. Even if this is not the objective of collectives, the discourse from all society and replicated/fed by collectives may lead to emptying the political fight linked to parties.

In view of this scenario, there is a need for, in the academic field, more researches to reflexively analyze protest movements organized by young people. It should be taken into account that through these analyses a better comprehension will be achieved concerning the current national crisis, as well action alternatives to be taken.

For the political praxis , the bets of Dardot and Laval (2017) are valid in the work of worldwide environmental and social movements which challenge the natural resources, knowledge, public space and service appropriation by some part of an oligarchy. Social fights must aim, according to the authors, at the institution of the common: material and immaterial means necessary to the collective activities, which would not be, therefore, private or state property. Once the neoliberal world-reason is introjected in the world, there would not be any negotiation with these capitalist models. For this reason, the common would be the revolution: a new political reason that must replace the neoliberal reason.

REFERENCES

AUGUSTO, Acácio; ROSA, Pablo Ornelas; RESENDE, Paulo Edgar da Rocha. Capturas e resistências nas democracias liberais: uma mirada sobre a participação dos jovens nos novíssimos movimentos. Revista Estudos de Sociologia , Araraquara, v. 21, n. 40, p. 21-37, 2016. [ Links ]

BAQUERO, Marcello; BAQUERO, Rute; MORAIS, Jennifer Azambuja de. Socialização política e internet na construção de uma cultura política juvenil no sul do Brasil. Educação & Sociedade , Campinas, v. 63037, n. 137, p. 989-1008, 2016. [ Links ]

BAQUERO, Marcello; GONZÁLEZ, Rodrigo Stumpf. Cultura política, mudanças econômicas e democracia inercial: uma análise pós-eleições de 2014. Opinião Pública , Campinas, v. 22, n. 3, p. 492-523, 2016. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo . Lisboa: Edições 70, 2006. [ Links ]

BORELLI, Silvia Helena Simões; ABOBOREIRA, Ariane. Teorias/metodologias: trajetos de investigação com coletivos juvenis em São Paulo/Brasil. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales , Manizales, v. 9, n. 1, p. 161-172, 2011. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, Ruth. Movimentos sociais na América Latina. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais , São Paulo, v. 1, n. 3, 1987. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, Henrique Soares. Apresentação. In: HARVEY, Davi et al. Occupy: movimentos de protesto que tomaram as ruas. São Paulo: Boitempo: Carta Maior, 2012. p. 4-14. [ Links ]

DARDOT, Pierre; LAVAL, Christian. A nova razão do mundo: ensaio sobre a sociedade neoliberal. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

DARDOT, Pierre; LAVAL, Christian. Comum: ensaio sobre a revolução no século XXI. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2017. [ Links ]

DAY, Richard. Gramsci is dead: anarchist currents in the newest social movements. London: Pluto Press, 2005. [ Links ]

DOIMO, Ana Maria. A vez e a voz do popular . Rio de Janeiro: Anpocs, 1995. [ Links ]

DRAIBE, Sônia Miriam. As políticas sociais brasileiras: diagnósticos e perspectivas. In: INSTITUTO DE PESQUISA ECONÔMICA APLICADA - IPEA. Para a década de 90: prioridades e perspectivas de políticas públicas. Brasília, DF: IPEA/IPLAN, 1989. p.1-66. [ Links ]

GENTILI, Pablo; SADER, Emir (org.). Pós-neoliberalismo: as políticas sociais e o Estado democrático. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1995. [ Links ]

GOHN, Maria da Glória. Jovens na política na atualidade: uma nova cultura de participação. Caderno CRH , Salvador, v. 31, n. 82, p. 117-133, 2018. [ Links ]

GOHN, Maria da Glória. Manifestações e protestos no Brasil . São Paulo: Cortez, 2017. [ Links ]

GURZA LAVALLE, Adrián. Sem pena nem gloria: o debate da sociedade civil nos anos 1990. Novos Estudos Cebrap , São Paulo, n. 66, p. 91-110, 2003. [ Links ]

GUTMANN, Amy; THOMPSON, Dennis. O que significa democracia deliberativa. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Constitucionais , Belo Horizonte, n. 1, p. 17-78, 2007. [ Links ]

LATINOBARÔMETRO. Banco de dados: Latinobarómetro . [S. l: s. n.], 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.latinobarometro.org>. Acesso em 4 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

LATINOBARÔMETRO. Banco de dados: Latinobarómetro. [S. l: s. n.], 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.latinobarometro.org>. Acesso em 4 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

LATINOBARÔMETRO. Banco de dados: Latinobarómetro . [S. l: s. n.], 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.latinobarometro.org>. Acesso em 4 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

MAIA, Gretha Leite. A juventude e os coletivos: como se articulam novas formas de expressão política. Revista Eletrônica do Curso de Direito da UFSM , Santa Maria, v. 8, n. 1, p. 58-73, 2013. [ Links ]

MELUCCI, Alberto. Um objetivo para os movimentos sociais? Lua Nova , São Paulo, n. 17, p. 49-66, 1989. [ Links ]

PATEMAN, Carole. Participação e teoria democrática . Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra,1992. [ Links ]

ROUSSEAU, Jean-Jacques. O contrato social . Porto Alegre: L&PM, [1762] 2014. [ Links ]

SADER, Eder. Quando novos personagens entram em cena: experiências, falas e lutas dos trabalhadores da Grande São Paulo (1970-80). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1988. [ Links ]

TATAGIBA, Luciana. 1984, 1992 e 2013: sobre ciclos de protestos e democracia no Brasil. Política & Sociedade , Florianópolis, v. 13, n. 28, p. 35-62, 2014. [ Links ]

TATAGIBA, Luciana. Desafios da relação entre movimentos sociais e instituições políticas: o caso do movimento de moradia da cidade de São Paulo – Primeiras reflexões. Colombia Internacional , Bogotá, n. 71, p. 63-83, 2010. [ Links ]

TILLY, Charles. Os movimentos sociais como política. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política , Brasília, DF, n. 3, p. 133-160, 2010. [ Links ]

TOURAINE, Alain. Na fronteira dos movimentos sociais. Sociedade e Estado , Brasília, DF, v. 21, n. 1, p. 17-28, 2006. [ Links ]

VOMMARO, Pablo. Juventudes y políticas en la Argentina y en América Latina: tendencias, conflictos y desafios. Buenos Aires: Universitario, 2015. [ Links ]

1- We are grateful to Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Piauí (FAPEPI) for the financial aid to the scientific research publication and to Universidade Federal do Piauí (UFPI) for the translation services. Responsible for translation: Universidade Federal do Piaui Translation Office.

4- Latinobarómetro Corporation is a private, non-profit organization, based in Chile. According to their website, it is multiply financed, with the participation of international organizations, governments and the private sector, e.g. the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Corporación Andina de Fomento (CAF). Organization of American States (OAS), United States Office of Research, IDEA International and UK Data Archive.

5- Age groups are in accordance with IBGE criteria – Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics –, although it is not possible to distinguish generations only by the age criterion, disregarding the cultural context and the subjects’ lives.

Translator: João Batista de O. Silva Jr.

Received: December 17, 2018; Revised: April 15, 2019; Accepted: September 11, 2019

texto em

texto em