Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 20-Jul-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046219377

SECTION: ARTICLES

Teacher´s empathy in preschool education: a study on Mexican educators

1- Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, Puebla, México. Contacts: magovital@hotmail.com; marthaleticia.gaeta@upaep.mx.

2- Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, España. Contact: valenmop@edu.ucm.es.

Empathy, considered here as a teaching cognitive-emotional competence, is the ability to understand and share the emotional state of other people and constitutes a fundamental process for establishing positive personal interactions. In the school context, empathy allows teachers to improve their relationships with students in the classroom, and also to prevent situations of bullying and school violence starting with young children. The objective of the research that gave rise to this article was to analyze teachers´ empathy in preschool education, from a multidimensional perspective. Participants were 110 educators from four preschool-level centers located in different cities of the State of Puebla, Mexico. Cognitive and Affective Empathy Test (TECA) was used as it integrates two major dimensions: cognitive and emotional. Results show that most educators present average levels of empathy, characterized by flexible thinking, adaptability to different situations, tolerance, and ability to establish positive interactions with others. There are differences in dimensions of empathy depending on the school the professional belongs to, mainly in the way they see and understand empathy. Based on these data, training initiatives should be proposed to further develop empathy skill in preschool teachers in the Mexican context.

Key words: Emotional competences; Empathy; Teacher; Child education

La empatía, considerada aquí como una competencia cognitivo-emocional docente, es la capacidad de entender y compartir el estado emocional de otras personas y constituye un proceso fundamental para establecer interacciones personales positivas. En el ámbito escolar, la empatía puede permitir a los docentes mejorar las relaciones con sus alumnos en el aula, además de prevenir situaciones de acoso y violencia escolar desde edades tempranas. El objetivo de la investigación que dio origen a este artículo fue analizar la empatía docente en educación preescolar, desde una visión multidimensional. Participaron 110 educadores de cuatro centros de nivel preescolar, ubicados en distintas ciudades del Estado de Puebla, México. Se utilizó el Test de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva (TECA) que integra dos dimensiones principales: cognitiva y emocional. Los resultados muestran que los educadores en su mayoría presentan niveles medios de empatía, caracterizada por un pensamiento flexible, adaptabilidad a diferentes situaciones, tolerancia y capacidad para establecer interacciones positivas con los otros. Existen diferencias en las dimensiones de empatía en relación al centro escolar de pertenencia; principalmente en adopción de perspectivas y comprensión empática. A partir de estos datos, se considera necesario plantear medidas formativas para un mayor desarrollo de la empatía en docentes de preescolar, en el contexto mexicano.

Palabras-clave: Competencias emocionales; Empatía; Docente; Educación infantil

Introduction

Empathy has been seen as the ability to understand and share the moods of others (COHEN; STAYLER, 1996), as well as to respond to them correctly. It assumes deep intellectual and emotional understanding of someone else’ circumstances. From this, it is a fundamental precursor of many forms of adaptive social interaction (MESTRE; SAMPER; FRÍAS, 2002; MOYA-ABIOL; HERRERO; BERNAL, 2010; RICHAUD, 2014).

Empathy allows one to get closer to another, to be more attuned to him and, therefore, it is a key aspect in an interpersonal relationship. We are faced with the notion of great importance in human relations upon dealing with the starting point of positive relations whose implications are felt in all environments, even, of course, in school.

In the concrete environment of the educational professions, it is undeniable that teachers of all levels need to demonstrate a sufficient empathic level to allow them to have the sensitivity necessary to understand the students with whom they work, as well as with family and co-workers, toward those who have shown a mindset for dialogue and attunement, keys in relationships between people and in the educational process. Let us remember, in this regard, the importance that Rogers (1972), a classic reference, gave to empathic understanding, characterized by the possibility of experiencing what the other felt as if he or she were in the other’s place, a fundamental aspect in all relationships and especially in teacher communication.

Understanding the formation of teacher personality as an ever-changing process (ROGERS, 1972), we believe that the development of an optimum empathic level will give teachers soundness in the management of their interpersonal relations, harmony in interactions with their students and, therefore, better professional performance.

In Mexico, the relevance of the study on empathy in the educational field has increased due to the increase in violence and bullying (MUÑOZ, 2008), together with other problems such as academic desertion and failure (MEXICO, 2016) and poor relationships, among others. Thus, for example, in the brief published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2015) regarding bullying, Mexico occupied first place at an international level.

Likewise, in the most recent brief from the Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (INEE, 2018), it was reported that scholastic population had reached 30.9 million students enrolled in primary education, of which 38.5% affirmed to have received insults from classmates at the primary school level and 46.5% at secondary school level.

For its part, the Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición survey warned that the prevalence of attempted suicide among teens between 10-19 years of age has increased in Mexico (ENSANUT, 2012). For this reason, every day the emotional abilities in teachers and students that promote healthier relationships during the educational process are more highly valued. However, research is still needed regarding teacher empathy and the concrete benefits it gives to the educational process.

From the previous data, in this research, teacher empathy in the classroom is analyzed as a suitable pedagogical means to improve the relationships teachers establish with their students, to promote integral education and to prevent unwanted situations, among which are school violence and bullying. It is held in the study that empathy, in general, acts as a facilitating variable of interpersonal relations.

Empathy in the teacher

Empathy is a notion of great pedagogical value. Etymologically, it comes from the Greek εμπαθεια (εν, inside and πάθoς, suffering, what one feels). In sympathy, there is an interpersonal affective inclination, generally spontaneous and mutual, while in empathy, there is an emotional understanding of the other, but it need not be reciprocal nor spontaneous.

It should be mentioned that empathy has received extensive attention from different fields of study, such as philosophy, theology, psychology, ethology, among others. However, there has been a lack of agreement regarding its nature (MOYA-ALBIOL; HERRERO; BERNAL, 2010; MUÑOZ-ZAPATA; CHAVES, 2013). Authors such as Dymond (1949 apud DAVIS, 1983) have placed it as a cognitive process, while others such as Hoffman (2000) and Eisenberg (2000) see it as mainly affective. Davis (1983) proposes an integrative approach in which he conceives empathy from its cognitive nature and links it to the emotional dimension, arguing that both aspects, although independent, are part of the same phenomenon.

From a multidimensional perspective, which includes cognitive and emotional factors, which we adopt in this research, several studies have been done with university students from different areas (COSTA; ACEVEDO, 2010; FLORES, 2017; RUIZ, 2016), and particularly with student teachers (HERRERA; BUITRAGO; AVILA, 2016; MARTINEZ OTERO, 2011; SEGARRA; MUÑOZ; SEGARRA, 2016). However, the study on empathy in the in-service teachers, from a cognitive-affective system, has not been sufficiently fostered.

In teachers, empathy is fundamental for a greater approach, rapport and acceptance of the other and, therefore, for a better educational relationship. Therefore, empathy may be relevant in aspects such as the promotion of personal development of the group under study (QUINLAN, 2016), teamwork (RODRIGUEZ-GARCIA et al., 2017), preventing bullying (MURPHY; TUBRITT; NORMAN, 2018; VAN NOORDEN et al., 2017) and even in teacher performance (PLATSIDOU; AGALIOTIS, 2017). Years ago, Professor Repetto (1992) took an interest in the importance of empathic understanding in the educational process.

The research carried out by Rodrigues and Miguel da Silva (2012) reveals the importance of the promotion of empathy as a factor of protection of childhood development. Concretely, it emphasizes that the deployment of socioemotional skills, such as empathy, from childhood education promotes resilience and the establishment of healthier interpersonal relations in school, as well as in other scenarios in which children develop.

Of course, in all educational relationships, empathy assumes a relevant role since it is a decisive factor in the interpersonal forum and facilitating dimension of the improvement of personality. As asserted by Pavarini and Souza (2010), empathy may be seen as an evolutionarily relevant and essential skill for the maintenance of human communities.

Goleman (1998) has said that the lack of attunement in childhood may have a higher emotional cost, perceivable even in adulthood. Among other aspects, the lack of empathic ability is related to serious antisocial acts, abusive behavior, the absence of feelings of guilt and indifference in violent acts committed against others (CALVO; GONZALEZ; MARTORELL, 2001; SANCHEZ; ORTEGA; MENESINI, 2012).

There are teachers who unnecessarily problematize the students, implying that they cannot improve or they have committed a transgression so serious that there is no possibility for solution. From this perspective, very negative judgment which may impede or halt personal development should be avoided, without this assuming acceptance of all behavior.

The insufficiently empathic teacher remains distant from the student, shows little understanding and has serious difficulties showing a genuinely educational attitude. Another risk is that of excessive empathic involvement, which may hurt the interpersonal relationship, the educational process and even the mental health of the professional, making him or her more susceptible to burn-out. Therefore, empathic balance is needed.

On the need to maintain empathic balance, previous research carried out from the TECA test (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ; FERNÁNDEZ-PINTO; ABAD, 2008), instrument also used in this research, reports the existence of various empathic styles of pedagogical scope. On one hand, an objective empathic style (externalized, cognitive), mainly concerned with how rationality pervades in the emotional reality of others and the significant affective autonomy regarding others’ moods. As per this empathic style, the attunement with the teachers or with other members of the educational community will be more intellectual than emotional. Accordingly, although they include the moods of others, they are not necessarily experienced.

On the other hand, a subjective empathic style has been found (internalized, affective), that is, an intellectual and emotional way of approaching others and interacting with them with a tendency to be emotionally influenced by others. Such empathic style concerns the ability to identify and understand the affective conditions of the teachers or other members of the educational community, as well as the willingness to share their positive or negative emotions.

Finally, a third style, which in a certain way brings together and exceeds the previous two, is the intersubjective empathic style, characterized by the balanced cognitive and affective approach to others’ emotional reality, which impedes the dysfunctional or distressing introjection and makes healthy resonance between people possible.

Therefore, the empathic educational style should be conceptualized as a cognitive and affective process of approaching the emotional reality of the students. This style, as seen, may be subjective, objective or intersubjective, and it conditions and characterizes how one knows and feels the moods of others. The empathic style depends on the person him/herself. Also, its suitability will depend on the age and on the personality of the students, of their situation, etc, but, in general, the intersubjective empathic educational style is preferable.

Whatever the predominant empathic style in the teacher, what is important is that he/she maintains a balance between the cognitive and the affective side, and pays attention to the optimum educational distance. Sometimes an alternation will even proceed or, better yet, an enhanced synthesis of the two styles- subjective and objective, this is, a kind of intersubjective empathic educational style as previously defined, Therefore, for example, in especially critical situations in the classroom, the teacher, while cognitively and affectively engaging others’ emotional reality, should put enough distance between others’ reality and his or her own in order to be able to make wiser decisions.

With these precautions, communication, understanding and attunement are much easier, as is the educational process. In view of the importance of the humanistic aspects, not only technical factors, have in teaching, the teacher training curriculum must be worked on at both a theoretical and practical level (SEGARRA; MUÑOZ; SEGARRA, 2016). Empathy, in particular, occupies a central place in the relationship among people, and since its use may facilitate the students’ intellectual and emotional development, if insufficient attention is paid, or if it is inadequate, it may negatively impact his or her development.

The research carried out

This research was carried out with the objective of contributing knowledge about teacher empathy at preschool level in schools from the state of Puebla, Mexico. Concretely, teacher empathy was assessed according to the TECA, or the Test of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ; FERNÁNDEZ-PINTO; ABAD, 2008), both globally and in its four dimensions. The first two refer to the measurement of cognitive empathy and the other two related to affective empathy- Adoption of Perspectives (AP), Empathic Understanding (EU), Empathic Stress (ES) and Empathic Joy (EJ).

Method

The study was carried out by exploratory type cross-sectional quantitative methodology. Quantitative research in the field of pedagogy has as its objective to approach the knowledge of the educational reality with greater objectivity in order to give reliable and structured information, as well as the possibility for comparison and replica (HERNÁNDEZ; FERNÁNDEZ; BAPTISTA, 2006). Even when it is the only possible methodological path, here it is considered the most suitable, from the application of a standardized instrument and through data analysis with support from the statistics (COOK; REICHARDT, 1986).

Participants

One-hundred ten educators at preschool level (108 women and 2 men) participated, specialists in working with kindergarten children, both in government and private schools, with teaching experience from 3 to 36 years and an age ranging from 22-55 years, who work in four cities-- Puebla, Cholula, San Martin and Tepeaca- all from the state of Puebla.

It is an intentional sample in which the teachers called through an invitation participated voluntarily. The invitation was made by the area of teacher training from the Centros de Atencion Psicopedagogica de Educación Preescolar (CAPEP) in the annual meeting for in-service teacher training carried out by such organism. The sample was constituted as follows:

Instrument

To measure teacher empathy, the Test of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (TECA), a standardized instrument with suitable psychometric properties (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ; FERNÁNDEZ-PINTO; ABAD, 2008), was applied. The TECA consists of 33 items which give information on the cognitive and affective components of empathy through four scales: 1) Adoption of Perspectives, 2) Emotional Understanding, 3) Empathic Stress, and 4) Empathic Joy. Each has specific scoring, to which a global empathy scale is added.

Each dimension and sub-dimension of the instrument, taken from the test manual (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ; FERNÁNDEZ-PINTO; ABAD, 2008) is described below:

Adoption of Perspectives (AP)

This includes the cognitive dimension and refers to the intellectual or imaginative capacity to put oneself in another’s shoes. High scores on this scale indicate flexible thinking which is adaptable to different situations. Likewise, they reveal greater capacity for tolerance and human relations, although high scores may affect the capacity for decision-making due to the cognitive load the consideration of all points of view represents. Meanwhile, low scores indicate less cognitive flexibility and ability to understand others’ moods. In turn, extremely low scores may indicate difficulties in communication and relation skills due to a very rigid thinking style.

Emotional Understanding (UE, or CE in original instrument)

This also includes the cognitive dimension and is understood as the ability to recognize and is understood as the ability to recognize and understand others’ moods, intentions and impressions. The high score may correspond to persons who have great ease in making an emotional reading of the verbal and non-verbal behavior of others, which has a positive impact on communication, relations and emotional control. But very high scores may reflect excessive attention to the moods of others at the expense of their own. Low scores, on the other hand, may be associated to poor quality in interpersonal relations and less development of social skills. Very low scores indicate considerable emotional difficulties as well as difficulties relating with others.

Empathic Stress (ES, or EE in original instrument)

This includes the affective dimension and refers to the ability to share negative emotions of others. High scores indicate people who are characterized by having good quality social networks, by being emotive and warm in their relationships, although they may be excessively involved in the problems of others. Excessively high scores may indicate elevated neuroticism, negatively affecting the person’s life, since he/she may see someone else’ suffering is greater than his/her own. Low scores may correspond to people who are not very emotive and have difficulties distinguishing their own emotions and those of others. Extremely low scores are related to people with excessive emotional coldness with difficulty feeling what happens to others and they may have a lower-quality social network.

Empathic Joy (EJ, or AE in original instrument)

This also includes the affective dimension and is the ability to share the positive emotions of others. People with a high score tend to have a good quality social network. An excessively high score may indicate that the person believes that their own happiness depends on the happiness of others. Low scores, on the other hand, reflect lower tendency to share the positive emotions of others. Very low scores indicate indifference toward the positive emotions of others, resulting in a very low quality social network. However, the significance of a high, average or low score will depend on the context of the situation for which one is assessed.

Procedure

The research was carried out with permission from the corresponding educational authorities. For the data collection, the teachers answered the TECA test collectively, at the same time, during a session called by the area of in-service teacher training of the CAPEP. It lasted from 20 to 30 minutes. The application of the test was carried out by the researchers. The participation of the teachers was voluntary and the confidentiality of the data given was maintained. The results of the study were given in writing to the participants at the end of the study.

For the analysis of the data, after considering the standards of test correction in the TECA manual, direct scores and the corresponding percentile were obtained. Later, to establish the teacher profiles, the cut points regarding the average of each scale were used. In general, an optimal profile is that which overall is located between percentiles 7 and 93 of the test. Therefore, according to the TECA manual in the selection of professional positions, an optimal profile for the teachers is between percentiles 69 and 93 for cognitive scales and between percentiles 7 and 93 for affective scales (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ; FERNÁNDEZ-PINTO; ABAD, 2008).

On that basis, several statistical calculations were carried out: univariate descriptive analysis (median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum), analysis of normality of the data and inferential analysis (comparison of more than two independent groups). The comparison between the groups was carried out from the non-parametric inferential statistic (Kruskal Wallis test), given that the normality of the data was rejected (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The analysis was carried out through the use of SPSS statistical software, version 22.

Results

Descriptive analyses

The one-hundred ten educators were distributed into five groups according to the school where they worked: 1) City of Puebla, 2) Cholula Morning session, 3) Cholula Afternoon session, 2) San Martín and 5) Tepeaca. The largest group was the morning session from Cholula (32.7%), followed by the groups from Tepeaca (20.9%), City of Puebla (20.9%), Cholula afternoon session (13.6 %) and San Martín (11.8%).

Of the total number of teachers, the majority is older than 40 years of age (44.5%), followed by those between 30 and 40 years of age (31.80%) and those who are between 20 and 30 years of age (23.6%). In the majority of the teachers, they have between one and ten years of teaching service (46.36%), followed by those who have twenty to thirty years of service. The majority of the educators have bachelor level studies in preschool education (78.18%), followed by those who have master-level studies (14.54%), and those with Normal school studies (Teacher training school in Mexico), corresponding to 7.2%.

Levels of teacher empathy

As shown in Table 1, the teachers have average scores of 42.07 in global empathy. In the analysis by scale, it was found that in Emotional Understanding (EU) they got an average score of 57.79, followed by Adoption of Perspectives (AP) with a score of 41.49, Empathic Stress (ES) of 38.15 and Empathic Joy (EJ) of 35.05. According to the scales of the TECA test (LÓPEZ-PÉREZ et al., 2008), the data correspond to average scores in the former two scales (EU and AP) and low scores in the latter two (ES and EJ), which indicates suitable levels of empathy. Likewise, an optimal level of empathy was seen at a global level, from the average obtained (42.07), located between the 7th and 93rdpercentiles of the test.

Table 1 Levels of teacher empathy

| Median | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Global Empathy (GE) | 42.07 | 19.927 |

| Adoption of Perspectives (AP) | 41.49 | 22.997 |

| Emotional Understanding (EU) | 57.79 | 26.566 |

| Empathic Stress (ES) | 38.15 | 20.526 |

| Empathic Joy (EJ) | 35.05 | 20.721 |

Source: Authors.

A closer analysis showed that regarding global empathy, resulting from the cognitive scales (AP and EU) and from the affective scales (ES and EJ), of the total teacher participants, 55% (n=61) have scores located at an average level and 11% (n=12) at a high level.

However, 34% have a low level of empathy (n=37).

Regarding the analysis by dimension, in Adoption of Perspectives (AP), the majority of the teachers (65%) got scores located in the average and high levels; 49% had their score at an average level and 16% at a high level. In the Empathic Understanding (EU) dimension, the majority of the teachers (82%) got scores located at average or high levels; 45% had their score at an average level, while 22% got theirs at a high level and 15% at the extremely high level.

In the dimension of Empathic Stress (ES), for their part, the majority of the teachers (90%) got average scores located at the average or low levels; 44% had their scores at the average level, while 46% had theirs at the low level. Likewise, in the Empathic Joy (EJ) dimension, 48% of the teachers got average scores located at the average level and 40% at the low level.

Levels of empathy by school in which they work

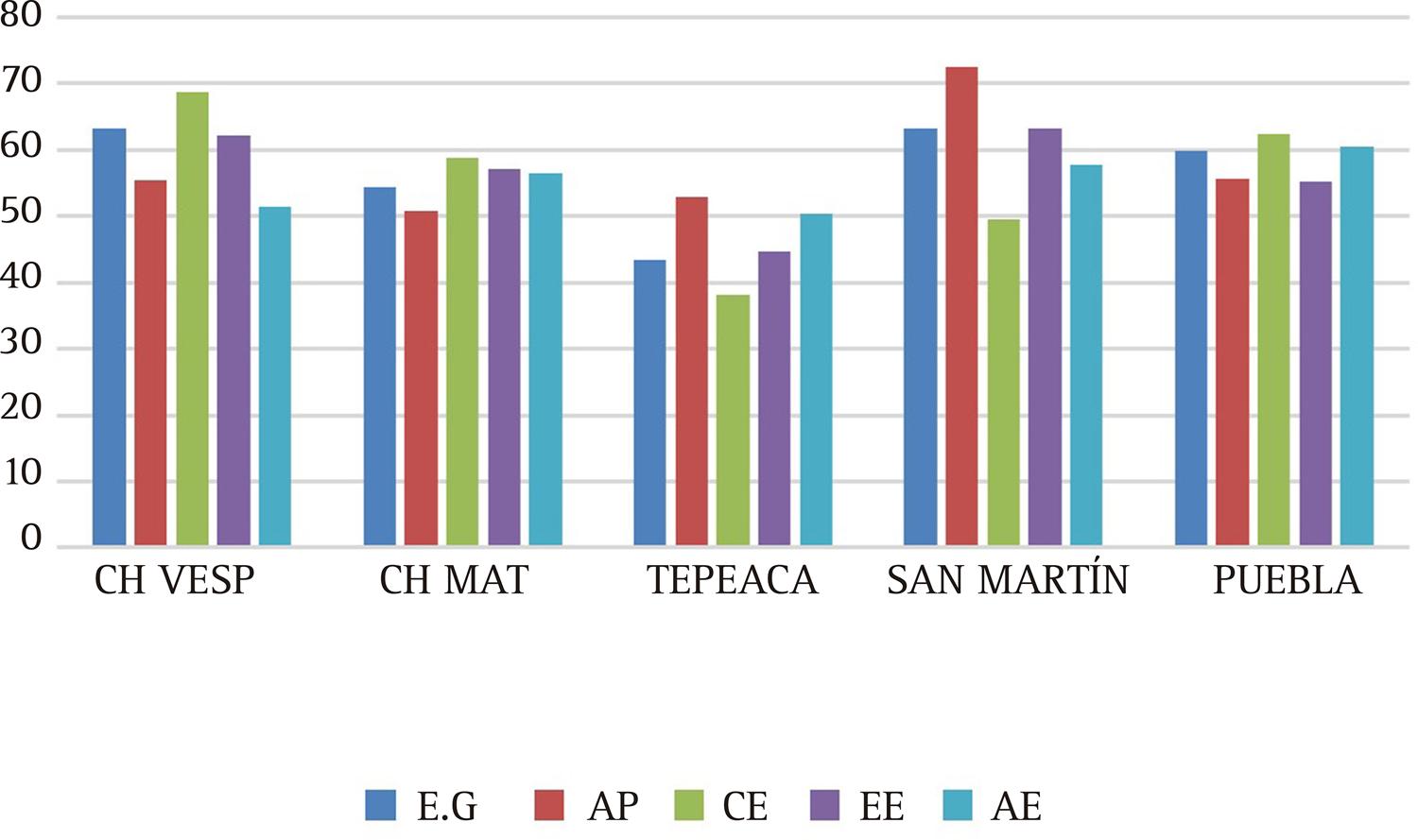

In this section, the levels of global empathy as well as empathy by school are shown. As seen in Figure 1, all the groups have average levels of global empathy above 50, except the group from Tepeaca (44.98).

Figure 1 Global Empathy and empathy by dimension regarding school to in which they workNote: CH VESP=Cholula Afternoon; CH MAT=Cholula Morning; EG=Global Empathy; AP=Adoption of Perspective; CE=Empathic Understanding; EE=Empathic Stress; AE=Empathic Joy;Source: Authors.

Regarding the Adoption of Perspective (AP) dimension, the group that had the highest average levels is that of San Martin (72.42) and the group with the lowest average levels is the morning session of Cholula (55.53).

Regarding Empathic Understanding (EU), the five groups got an average score higher than 38 points; however, the levels of empathic understanding vary among them. Specifically, the results range between 38.15 for the group from Tepeaca and 68.63 for the group from the afternoon session in Cholula.

Regarding the Empathic Stress (ES) dimension, the average values range from 44.61 for the group from Tepeaca to 63.19 for the group from San Martin, which correspond to low levels in the five groups.

Concerning the Empathic Joy (EJ) dimension, the average values range from 50.33, obtained by the group from Tepeaca, to 60.41, obtained by the group from Puebla, which indicate low levels in the five groups.

Afterwards, a comparison of the empathy levels by school in which they work was carried out through the Kruskal Wallis statistic, which showed significant differences only in the Emotional Understanding dimension (Chi-square=11.343; p=0.23), as can be seen in Table 2.

Discussion

According to the main objective of this research, which was to analyze teacher empathy in teachers at the preschool level, the most prominent results are recalled.

Regarding the assessment of the levels of global empathy in teachers, we highlight that the data obtained correspond to an optimum profile, according to the scales of the instrument (located between the 7th and 93rd percentile). Likewise, the results by scale, with average scores in the two cognitive scales (EU and AP) and low scores in the two emotional scales (ES and EJ), show suitable levels of empathy.

In the teaching profession, it is fundamental to have high levels of cognitive empathy (HERRERA; BUITRAGO; AVILA, 2016) since teaching profession implies the understanding of the students’ needs, which allows him or her to offer quality attention (GIORDANI, 1997; REPETTO, 1992). Therefore, the only way to promote the personal development of the students is to create an environment of warmth and trust which facilitates their feelings of acceptance, value and safety. Cognitive empathy includes the scales of Adoption of Perspectives (AP) and Empathic Understanding (EU). In this respect, it is known that it is not positive to get high scores in affective empathy (Martinez-Otero, 2011), which includes the scales of Empathic Stress (ES) and Empathic Joy (EJ), which may be related to excessive involvement in the students’ problems and compromise the emotional balance of the teacher.

This may be complemented and fine-tuned with the data presented in this section. Of the total participating teachers, the majority (66%) shows a level of Global Empathy from average to high. Regarding the analysis by dimension, in Adoption of Perspectives (AP), the majority of the teachers have characteristics such as flexible thinking, adaptability to different situations, tolerance and the ability to establish human relations. The remaining 35% of the teachers that got low and extremely low scores apparently have lesser cognitive flexibility and even have difficulties understanding the moods of others.

In the Empathic Understanding (EU) dimension, the majority of teachers (more than 82%) got average, high or extremely high levels, which concern characteristics such as ease for reading one’s emotions, communication and human relations. The remaining 18% of teachers had difficulty identifying the emotions of others and in controlling their own emotions.

In the Empathic Stress (ES) dimension, the majority of teachers (90%) showed average to low levels, which shows that the great majority of the participants keep and emotional distance in their interpersonal relationships. This is thought to be favorable since this also allows proper handling of stress in the teaching profession; that is, they do not show excessive involvement in the problems of their students, parents or colleagues. Likewise, in the Empathic Joy (EJ) dimension, the majority (88%) of teachers got average to low levels, which shows that they do not excessively get involved in the positive emotions of others; however, 12% does do such.

The foregoing results confirm, in general, that the majority of the teachers have the optimum empathic profile required to properly carry on in their profession, which coincides to the findings of previous research on this topic (HERRERA; BUITRAGO; AVILA, 2016; PALOMERO, 2009). Approach, attunement and consideration of others, from an empathic point of view, therefore constitute a key aspect in the educational relationship. Empathy is of vital importance in the construction of shared meaning, as well as in working together, understanding and personal development.

On the other hand, regarding empathy of teachers by school in which they work, the group from San Martin stands out with high levels in the Adoption of Perspectives (AP) dimension. This indicates that the teachers from this group have characteristics of cognitive empathy, such as understanding the moods of others and cognitive flexibility, above the other four groups. The Cholula morning session, Cholula afternoon session and Puebla groups show high levels in the Empathic Understanding (EU) dimension, which implies the ease for reading the emotions of others as its main characteristic. Regarding the dimensions Empathic Stress (ES) and Empathic Joy (EJ), the average values obtained indicate that the teachers from the five groups keeps appropriate emotional distance in their interpersonal relationships.

Conclusions

From our findings, we can conclude that the teachers have high levels of Adoption of Perspectives (AP) and Empathic Understanding (EU), which together represent the optimum cognitive empathic response required to teach. This is an empathic response based on the others’ understanding and in the authentic understanding of their mood.

Likewise, low levels in the Empathic Stress (ES) and Empathic Joy (EJ) scales stand out, which also show optimum levels of empathy required for teaching, remembering that getting low scores in ES and EJ contribute to maintaining professional objectivity, since others’ emotions are not attuned to the point in which they are considered more important than their own, that is they keep a proper emotional distance.

The results previously given are encouraging regarding the percentages of teachers, who in their majority reach optimum levels of teaching empathy, both in global empathy as in its dimensions. However, despite these good results, there is a percentage (7%) of teachers who obtained extremely low levels of empathy and other teachers (between 13% and 20%) with low levels, which leads us to propose the need to give resources to the teachers who are in these ranges so they may optimize their levels of empathy through technical and humanistic professional preparation (HERRERA; BUITRAGO; AVILA, 2016). Predictably, their capacity for interpersonal relations and student learning will benefit.

Likewise, it is necessary to point out the importance of implementing programs for the development of emotional competences in which empathy occupies a central place, particularly directed toward the teachers who have not reached optimal levels of empathy (SEGARRA; MUÑOZ; SEGARRA, 2016). With that in mind, we cite, for example, the emotional program of Bisquerra (2005) and the affective intelligence development program (MARTINEZ-OTERO, 2007), and we convey the need to have new contextualized curricula that respond to the teachers’ needs and the reality they face in the different environments and levels of formation.

There are multiple benefits to having teachers with optimum levels of empathy; in general, they tend to have inclusive practices in the classroom, while they also contribute to the optimum development of the students’ personality. Inclusion implies that all students have sufficient sense of belonging to feel valued, safe and welcomed.

We also believe that promoting empathy in teachers who work with children may prevent future coexistence problems in schools. Childhood education is an exceptional stage for the development of empathy (RODRIGUES; MIGUEL, 2012), which has a stable characteristic at this age (CHACON; ROMERO, 2014). Having the children exposed to empathic acts by the teacher may help them display similar behavior, favoring scholastic and social adaptation of the student.

All teachers must value their students’ feelings and respect the family system, with which we must enhance communication, showing acceptance of the children, whatever their characteristics may be. This requires the development of emotional skills such as those researched herein, which allow the doors to discussion, participation and warmth to be opened, since as Pavarini and Souza (2010) warn, empathy is fundamental for maintaining human communities. Obviously, in the participating teachers, one can recognize different empathic annex and realization, in some cases, of certain lacks encourages us to demand teacher training that takes into account the development of empathic competences necessary in heterogeneous environments and in complex situations such as those found in schools.

In synthesis, we believe it is necessary to include subjects related to the development of affective intelligence in teacher training, as well as subjects that improve socioemotional skills, specifically teacher empathy, since an optimum level of empathic skill is required to effectively work as a teacher. Empathy in which the balance between the cognitive and affective aspect is maintained, as which contributes to maintaining optimum interpersonal distance in educational situations.

Likewise, in future research we think it is pertinent to apply the TECA test to larger groups of teachers and to teachers from other levels, which would allow the generalization of the results. They may also include other socio-cultural variables which would allow the analysis of certain conditioning factors of the educational processes to be attuned.

Referencias

BISQUERRA, Rafael. La educación emocional en la formación del profesorado. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Barcelona, v. 19, n. 3, p. 93-112, 2005. [ Links ]

CALVO, Ana José; GONZÁLEZ, Remedios; MARTORELL, Maria del Carmen. Variables relacionadas con la conducta prosocial en la infancia y adolescencia: personalidad, autoconcepto y género. Infancia y Aprendizaje, Barcelona, v. 24, n. 1, p. 95-111, 2001. [ Links ]

CHACÓN, Liliana; ROMERO, Juliana. Aprendizaje de las conductas empáticas en un grupo de preescolares. 2014. 42 p. Tesis (Grado en Psicología) – Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de la Sabana, Chía, 2014. [ Links ]

COHEN, Douglas; STAYER, Janet. Empathy in conduct-disordered and non-offending adolescent males. Developmental Psychology, Washington, DC, v. 32, n. 6, p. 988-998, 1996. [ Links ]

COOK, Thomas; REICHARDT, Charles. Métodos cualitativos y cuantitativos en investigación evaluativa. Madrid: Morata, 1986. [ Links ]

COSTA, Fabricio; ACEVEDO, Renata. Empatia, Relação médico-paciente e formação em medicina: um olhar qualitativo. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, Brasília, DF, v. 34, n. 2, p. 261-269, 2010. [ Links ]

DAVIS, Mark. Meausuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Washington, DC, v. 44, n. 1, p. 113-126, 1983. [ Links ]

EISENBERG, Nancy. Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, California, n. 51, p. 665-697, 2000. [ Links ]

ENSANUT. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición. Aspectos metodológicos. México, DF: INSP, 2012. Disponible en: https://ensanut.insp.mx/doctos/ENSANUT2012_AspectosMetodologicos_08Nov2012.pdf(2018). Acceso en: 25 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

FLORES, Liz. Propiedades psicométricas del test de empatía cognitiva y afectiva en estudiantes de institutos y universidades de Huamachuco. Revista de Investigación de Estudiantes de Psicología “JANG”, Lima, v. 6, n. 1, p. 17-28, 2017. [ Links ]

GIORDANI, Bruno. La relación de ayuda: de Rogers a Carkhuff. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer, 1997. [ Links ]

GOLEMAN, Daniel. La práctica de la inteligencia emocional. Barcelona: Kairós, 1998. [ Links ]

HERNANDEZ, Roberto; FERNANDEZ, Carlos; BAPTISTA, Maria. Metodología de la investigación. México, DF: McGraw-Hill, 2006. [ Links ]

HERRERA; Lucía; BUITRAGO, Rafael; AVILA, Aida. Empatía en futuros docentes de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. New Approaches in Educational Research, Alicante, v. 5, n. 1, p. 31-38, 2016. [ Links ]

HOFFMAN, Martin. Empathy and moral development: implications for caring and justice. New York: Cambirdge University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

INEE. Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa. La educación obligatoria en México: informe México, DF: INEE, 2018. Disponible en: <https://www.inee.edu.mx/portalweb/informe2018/04_informe/index.html>. Acceso en: 25 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

LOPEZ-PEREZ, Belén; FERNANDEZ-PINTO, Irene; ABAD, Francisco José. Test de Empatía Cognitiva TECA. Madrid: TEA, 2008. [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ-OTERO, Valentín. La empatía en la educación: una muestra de alumnos universitarios. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, Ciudad de México, v. 14, n. 4, p. 174-190, 2011. [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ-OTERO, Valentín. La inteligencia afectiva: teoría, práctica y programa. Madrid: CSS, 2007. [ Links ]

MESTRE, Vicenta; SAMPER, Paula; FRIAS, Dolores. Procesos cognitivos y emocionales predictores de la conducta prosocial y agresiva: la empatía como factor modulador. Psicothema, Oviedo, v. 14, n. 2, p. 227-232, 2002. [ Links ]

MÉXICO. Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP). Principales cifras del sistema educativo nacional 2015-2016 - México. México, DF: SEP, 2016. Disponible en: http://www.planeacion.sep.gob.mx/Doc/estadistica_e_indicadores/principales_cifras/principales_cifras_2015_2016_bolsillo_preliminar.pàginas11-17. Acceso en: 26 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

MOYA-ABIOL, Luis; HERRERO, Neus; BERNAL, María Consuelo. Bases neuronales de la empatía. Revista de Neurología, Barcelona, v. 50, n. 2, p. 89-100, 2010. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, Gustavo. Violencia escolar en México y en otros países: comparaciones a partir de los resultados del Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, Ciudad de México, v. 13, n. 39, p. 1195-1228, 2008. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ-ZAPATA, Adriana; CHAVES, Liliana. La empatía: ¿un concepto unívoco? Katharsis, Envigado, n. 16, p. 123-143, 2013. [ Links ]

MURPHY, Helena; TUBRITT, John; NORMAN, James O’Higgins. The role of empathy in preparing teachers to tackle bullying. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, Alicante, v. 7, n. 1, p. 17-23, 2018. [ Links ]

OCDE. Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económico. Informe de la Organización y Cooperación del Desarrollo Económico. [S. l.]: OCDE, 2015. Disponible en: <http://www.oecd.org/education>. Acceso en: 26 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

PALOMERO, Pablo. Desarrollo de la competencia social y emocional del profesorado: una aproximación desde la psicología humanista. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Zaragoza, v. 12, n. 2, p. 145-153, 2009. [ Links ]

PAVARINI, Gabriela; SOUZA, Débora de Hollanda. Teoria da mente, empatia e motivação pró-social em crianças pré-escolares. Psicologia em Estudo, Maringá, v. 15, n. 3, p. 613-622, 2010. [ Links ]

PLATSIDOU, María; AGALIOTIS, Ioannis. Does empathy predict instructional assignment-related stress? A study in special and general education teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, Queensland, v. 64, n. 1, p. 57-75, 2017. [ Links ]

QUINLAN, Kathleen. Developing student character through disciplinary curricula: an analysis of UK QAA subject benchmark statements. Studies in Higher Education, Melbourne, v. 41, n. 6, p. 1041-1054, 2016. [ Links ]

REPPETO, Elvira. Fundamentos de orientación: la empatía en el proceso orientador. Madrid: Morata, 1992. [ Links ]

RICHAUD, María. Algunos aportes sobre la importancia de la empatía y la prosocialidad en el desarrollo humano. Revista Mexicana de Investigación en Psicología, Ciudad de México, v. 6, n. 2, p. 171-176, 2014. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Marisa Cosenza; MIGUEL DA SILVA, Renata de Lourdes. Avaliação de um programa de promoção da empatía implementado na educação infantil. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 12, n. 1, p. 59-75, 2012. [ Links ]

RODRÍGUEZ-GARCÍA, Gustavo Adolfo et al. Impact of the Intensive Program of Emotional Intelligence (IPEI) on work supervisors. Psicothema, Oviedo, v. 29, n. 4, 508-513, 2017. [ Links ]

ROGERS, Carl Ransom. El proceso de convertirse en persona. Barcelona: Paidós, 1972. [ Links ]

RUIZ, Paola. Propiedades psicométricas del test de empatía cognitiva y afectiva en estudiantes no universitarios. Cátedra Villarreal Psicología, Lima, v. 1, n. 1, p. 99-116, 2016. [ Links ]

SANCHEZ, Virginia; ORTEGA, Rosario; MENESINI, Ersilia. La competencia emocional de agresores y víctimas de bullying. Anales de Psicología, Murcia, v. 28, n. 1, p. 71-82, 2012. [ Links ]

SEGARRA-MUÑOZ, Lola; MUÑOZ-VALLEJO, María Dolores; SEGARRA-MUÑOZ, Juana. Empatía y educación: implicaciones del rendimiento en empatía de profesores en formación. Análisis comparativo Universidad de Castilla la Mancha y Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Zaragoza, v. 19, n. 3, p. 173-183, 2016. [ Links ]

VAN NOORDEN, Tirza et al. Bullying involvement and empathy: child and target characteristics. Social Development, Kentucky, v. 26, n. 2, p. 248-262, 2017. [ Links ]

Received: January 31, 2019; Revised: June 25, 2019; Accepted: August 14, 2019

texto em

texto em