Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 09-Dez-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046225576

SECTION: ARTICLES

An analysis of guidelines on revision and rewriting of scientific texts in the digital universe*

1- Universidade do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte – Campus de Pau dos Ferros, Pau dos Ferros, Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Contact: cezinaldobessauern@gmail.com

Considering the wide reach and ease of access that the digital universe allows in the propagation of ideas and content, as well as the need to examine the credibility and quality of content with an educational and / or instructive bias that are conveyed in the communicative practices of that universe, this study investigates the treatment given to text revision and rewriting of scientific texts on national websites and blogs that address academic-scientific writing. Based on a sociointeractionist perspective of articulated language to the teaching of writing (GERALDI, 1997; ANTUNES, 2003; GARCEZ, 2010; SUASSUNA, 2011) and in studies that address the writing of academic-scientific texts (RUSSEL, 2009 ; NAVARRO, 2014; CARLINO, 2017), this article carries out an interpretative and qualitative analysis of a corpus consisting of 40 texts with content on the writing of scientific articles and monographs extrated from websites and blogs such as enago, Ciência prática, Lendo.org, Monografia urgente and TCC Pronto. The analysis points out that most of the investigated sites and blogs contemplate, in a precarious and restricted way, aspects involved in the practice of writing and rewriting of scientific texts, thus contributing to produce a fragmented image of what academic text writing activity actually is.

Key words: Text revision and rewriting; Teaching; Academic-scientific writing; Digital universe; Blogs and websites

Ao considerar o amplo alcance e a facilidade do acesso que o universo digital possibilita na propagação de ideias e conteúdos, bem como a necessidade de examinar a credibilidade e a qualidade de conteúdos com viés educativo e/ou instrutivo que são veiculados nas práticas comunicativas desse universo, este trabalho investiga o tratamento dado à revisão e à reescrita de textos científicos em sites e blogs nacionais que abordam a escrita acadêmico-científica. Fundamentado em trabalhos situados dentro de uma perspectiva sociointeracionista da linguagem articulada ao ensino da produção textual (GERALDI, 1997; ANTUNES, 2003; GARCEZ, 2010; SUASSUNA, 2011) e em estudos que abordam a escrita de textos acadêmico-científicos (RUSSEL, 2009; NAVARRO, 2014; CARLINO, 2017), este artigo realiza uma análise de natureza interpretativa e de base qualitativa de um corpus constituído por 40 textos com conteúdo a respeito da produção de artigos científicos e monografias coletados em sites e blogs como enago, Ciência prática, Lendo.org, Monografia urgente e TCC pronto. A análise aponta que a maioria dos sites e blogs investigados contemplam, de maneira precária e restrita, aspectos implicados na prática de escrever e reescrever textos científicos, contribuindo, assim, para produzir uma imagem fragmentada do que é efetivamente a atividade de produção de textos acadêmico-científicos.

Palavras-Chave: Revisão e reescrita; Ensino; Escrita acadêmico-científica; Universo digital; Blogs e sites

Introduction

The text revision and rewriting of texts occupy a privilege position in the context of the investigations conducted in the area of theoretical Linguistic, applied linguistics and education (ALVES; BESSA, 2018a; 2018b; MAFRA; BARROS, 2017; PEREIRA; LEITÃO, 2017; FERREIRA; LINO, 2014; GASPAROTTO; MENEGASSI, 2013; PINTON, 2012; MENEGASSI; FUZA, 2012; among others), in Brazil, today. Particularly, it has been a subject of constant debates in the field of language teaching, especially when the focus is on working with text-writing in mother tongue classes in basic education (BELOTI; MENEGASSI, 2017; SCHALKOSKI-DIAS; NICOLA, 2017; SUASSUNA, 2011; MARQUESI, 2011; ANTUNES, 2003, among others).

In the heart of these investigations and discussions, there is, as a rule, the understanding that the work with the text written by the student can no longer be conceived as a finished product in a single version (SUASSUNA, 2011; RUIZ, 2010; ANTUNES, 2003), although facing a wrtiting practice conceived in a procedural way is still a barrier (almost insurmountable!) and a huge challenge for many teachers, especially when considering the difficulties related to working conditions, the solid theoretical training of the teacher, the students’ lack of interest when asked to write, the rooted text teaching practices, etc.

It seems evident to us that, even though they are so desirable and necessary, the activities of revision and rewriting of texts are still not so common practices in the exercise of writing texts at school at different levels of education, despite the theoretical advances supporting the writing of texts as interactive, procedural and dialogical work, the emergence of several didactic-pedagogical proposals (including didactic work with writing) and improving the quality of activities present in Portuguese textbooks.

These reflections raised in the previous paragraphs encouraged us to think about the activities of revision and rewriting of texts in higher education, focusing our attention specifically in relation to the work with the production of scientific texts. If we understand that text revision and rewriting are inseparable from every act of producing texts, it becomes imperative when we conceive the production of scientific texts in times of productivity. In other words: when we deal with the writing of texts for publication in more qualified journals, in which the demanding criteria for submission of papers raise the quality of writing as a decisive criterion for the publication’s acceptance (PAGLIARUSSI, 2017).

It is considering this context and starting from the understanding that students and researchers at the beginning of their careers, in undergraduate and graduate courses, do not reveal much clarity about the functioning and conventions of the scientific sphere (NAVARRO, 2014). As a consequence, we believe it is fundamental to contemplate in books, scientific writing manuals and instructional educational materials, available in libraries, classrooms and virtual spaces, the presentation of guidelines and suggestions aimed at revising and rewriting scientific texts. Otherwise, it may compromise the understanding of nature process that characterizes the activity of producing texts.

Therefore, we intend to ask ourselves about the treatment given to the text revision and rewriting of texts in materials of an educational and / or instructive nature, which circulate in the universe of the internet, intended to present guidelines for the development of a successful writing of scientific texts. Specifically, we will examine the extent to which the corpus excerpts contemplate guidelines about the activities of revision and rewriting of scientific texts and how they conceive and conduct the development of these activities, seeking, finally, to evaluate the possible contributions of such guidelines to a scientific writing adequately and communicatively relevant.

We will focus more specifically on guidelines for writing scientific articles and monographs, given the importance of these genres of discourse in the scientific field, as well as our interest in researching genres that are commonly involved in the writing practices of researchers at the beginning of their careers. Our choice of material extracted from the internet is justified by the wide reach and the ease of access that the digital universe allows in the propagation of ideas and content, as well as by the need to critically examine the credibility and quality of the contents with educational bias that are conveyed in the communicative practices of this universe. Such choices highlight, therefore, the relevance of this work, be it in the theoretical-reflective plane, or in the dimension of the teaching of written (scientific) production that has characterized our research interests.

To support this research, we seek theoretical support in works in the area of socio-interactionist perspective of language articulated to teaching. Therefore, we refer, especially, to studies that discuss textual production as an interlocutive, procedural, dialogic activity. In addition, we seek to establish dialogues with works that address the writing of academic-scientific texts considering the specificities that characterize the ways of producing and socializing knowledge in the scientific universe.

The activity of writing and rewriting of texts: from basic education to higher education

For a long time, more pronouncedly since the 1980s, the textual production conceived as an interlocutive and procedural activity is issued in the fields of linguistic studies, notably Applied Linguistics and Education. Thus, this question starts to occupy an expressive space in the debates about language teaching, especially mother tongue, in Brazil, inserting itself in a context in which the text is framed with the objective of teaching languages, which is conceptualized in an interactional perspective (GERALDI, 1997; ANTUNES, 2003), which is its central theoretical anchorage.

Focused, initially, on the context of working with the practice of texts production in basic education, the revision and textual rewriting started to be faced and problematized also in the practices of text production in the University. That happened either in undergraduate or graduate courses, as Gehrke’s works demonstrate; Cabral (2017), Ferreira; Lino (2014), Bernardino et al. (2014), Pinton (2012), Martins; Araújo (2012), among others.

Today, therefore, there seems to be a consensus understanding that the activity of texts production, at any level of education / training, does not correspond to a tight, punctual activity, climited to a single act of the relationship between the subject of writing and paper and / or the computer / laptop screen. On the contrary, the production of texts is conceived as an interactive process, resulting from successive versions, which imply, according to Antunes (2003), distinct and integrated stages, comprising planning, execution and revision. Thus, in addition to the act of operating the initial version, the activity of producing texts at the school / university implies considering a previous planning stage and the subsequent stages of revising and rewriting. Therefore, producing texts, under these conditions, comprises a cooperative / collaborative work between at least two subjects placed in a concrete interlocutive relationship (GARCEZ, 2010) for the production of meanings.

In the field of methodology for teaching writing in the school environment, in which the discussion about text rewriting and revision is very well established, researchers like Pasquier and Dolz (1996) understand revision as an integral activity of writing. In this sense, they propose that, when learning to write a certain textual genre, a time between the writing of the first version and the time of the revision-rewriting should be taken into account, in order to allow the necessary distance for the student to reflect on his production and, in it, make changes.

Pasquier and Dolz’s (1996) understanding that the revision constitutes one of the strong moments in relation to the learning of textual production found fertile ground in proposals for teaching mother tongue. An example of this are the concepts expressed in the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN), in instructional materials and in the debate agenda of researchers and teaching professionals at scientific events, in such a way that it seems indisputable that we think of writing in a procedural way, although, in the practice of classroom, this proposal has not been fully materialized.

Despite this, we cannot fail to consider that, if the work with revision constitutes one of the most relevant moments in the learning of textual production, the mediation activity of the teacher, via intervention, as, for example, in the terms proposed by Ruiz (2010), and monitoring the process, in its successive stages and versions, is essential for the student to progress in learning to write. When dealing with the importance of the dialogical form of pedagogical mediation and emphasizing the role of the most developed pair in this process, Suassuna (2011) emphasizes that, in mediation work, the role of the teacher is not a mere identifier of textual problems, but being:

[...] an enabler and facilitator of reflection, in that it allows the writer (student) to be exposed to the interpretation of the other, starting to better understand how his/her speech is being read and how this reading was constructed. (SUASSUNA, 2011, p. 119).

In the academic-scientific universe, the work with textual revision and rewriting is not less challenging, especially when we consider that some students come from high school without the experience of writing successive versions of a text, demonstrating, often, little willingness to produce texts, when requested. In addition, it is necessary to consider that, when entering the academic-scientific universe, the student becomes part of a new context, in which “much more specialized writing” is implied (RUSSEL, 2009, p. 242):

[...] students must learn to use specialized vocabularies [...]. However, they also need to learn new genres or forms, those that are appropriate for researching in a given field, at least at more advanced levels of higher education. (RUSSEL, 2009, p. 242).

Thus, much more than simply mobilizing the reading and writing skills acquired in previous stages of school education, the conventions typical from disciplinary cultures and the requirements inherent in the activity of producing texts for the socialization of knowledge play, according to what we infer from the words de Navarro (2014) and Carlino (2017), crucial roles in the social practices of reading and writing carried out in the academic-scientific context, including, of course, the practices of revision and rewriting of scientific texts.

Considering the specificities and purposes that characterize the reading and writing practices of texts in the academic-scientific universe, especially when focused on the production and socialization of knowledge, as well as encouraging the production of the text, it’s essential a work that emphasizes the importance and the need of the other’s view on the text itself. Such a view, in order to be productive and effective, cannot, as Suassuna (2011) points out, be focused only on searching for errors and problems, but on making the student move from his position of enunciator to the position of reader and can, from the distance that this displacement implies, reflect on his choices and evaluate them in the reconstruction of his text.

We cannot fail to admit that, in the academic environment, especially among researchers at the beginning of their careers, the ability to understand the criticisms or rejections received in a work in the evaluation process as part of the writing and training process of the reseacher. Therefore, we think that an appropriate confrontation in relation to the difficulty of overcoming the fear of criticism and rejection, in the process of producing and publishing scientific texts, may be in the understanding and acceptance of what Munger (2016, p. 12) points out: “Nobody has good first drafts. The difference between a successful academic and a failure does not need to be better written. It is often more addiction”. It is, therefore, to demonstrate the capacity to assimilate and incorporate praise to criticism, making the writing of the text a movement of comings and goings (ANTUNES, 2003), that is, of permanent improvement, as a condition, therefore, of a significant improvement in quality of the manuscript.

Thus, it is evident that, while challenging, it is essential and necessary an effective work of intervention by the teacher, in an explicit and oriented way (NAVARRO, 2014), with a view to re-signifying practices with texts at school / university, in order to contribute to improvement of the student’s relationship with the rewriting of his own text. It is necessary, therefore, to think about the creation of effective conditions so that the student becomes a more autonomous producer and, therefore, enhances the quality of the production to be conveyed, especially in this context of increasingly growing demand for scientific texts qualified.

Methodology

Considering that our focus of concern, in this work, is on questions of language use in a specific context, of the communicative practices of the digital universe that (re) produce meanings about the activity of writing scientific texts, our investigation is located in the domain of Linguistics Applied (SIGNORINI; CAVALCANTI, 1998) in interface with the field of education.

In line with the direction of investigations in Applied Linguistics, our research is of interpretative-based nature, thus what essentially interests us is the dimension of the construction of meanings operated by the researcher - which cannot be understood, as highlighted by Laville and Dionne (1999), as a neutral subject, erased in the research process - in the dialogue established with the researched phenomena, which, in our case, are exerpts from websites and blogs. In this perspective, data analysis takes the bias of the qualitative research approach, even though the quantitative dimension is mobilized to some extent.

The corpus that constitutes the present work is composed of 40 texts with guidelines for writing scientific texts, more specifically scientific articles and monographs that deal with the practice of writing scientific texts. In particular, there are 20 texts with guidelines for writing scientific articles and 20 with guidelines for writing monographs, which were taken from blogs and websites, such as: enago, Ciência prática, Lendo.org, Pós-Graduando, Monografia urgente, Textuar, TCC pronto e Como escreve.

Considering our objectives and that, at first glance, we did not see any significant differences in the functioning of the guidelines circulating on websites and blogs, we chose not to make a distinction here between guidelines excerpts from these two circulation spaces. This also explains why we do not propose a study of a comparative nature.

The texts that make up the corpus of this work are part of a database of research on scientific writing developed within the Research Group on Production and Teaching of Text (GPET), of which we are part as researchers. Such texts were searched on the internet, from November 2017 to February 2018, using the Google search engine, using descriptors such as the following: How to make a monograph, How to make a scientific article, How to structure an article scientific. From this search, we were able to collect a variety of texts, some of which have titles such as: Step by step to make a grade 10 monograph; How to make a successful monograph; How to do a monograph on a weekend; 7 tips to speed up the writing of the scientific article; First steps to writing a scientific article; How to write a successful article.

After the corpus is collected, its coding2 and saving each text in a Word file, we moved on to the analysis of the excerpt material. The analysis procedures included, initially, a careful reading and rereading of all the collected texts, followed by identification of the occurrences of explicit mention, in the clipped material, the review and rewriting of scientific texts and, later, elaboration of analysis categories. After that, we proceeded to the description, analysis and interpretation of the data, as we propose to present in the next section.

Analysis of guidelines on text revision and rewriting of scientific texts in the digital universe

In this section, we will focus our attention on examining the 40 texts with guidelines regarding the review and rewriting of scientific texts taken from blogs and internet sites. Our purpose of investigating the treatment given to the revision and rewriting of texts in the clipped material aims, initially, to identify the presence of guidelines on revision and rewriting of scientific texts; and, then, to examine how the presented guidelines are conceived and sent, seeking, from there, to evaluate the possible contributions of such guidelines for an adequate and communicative scientific writing.

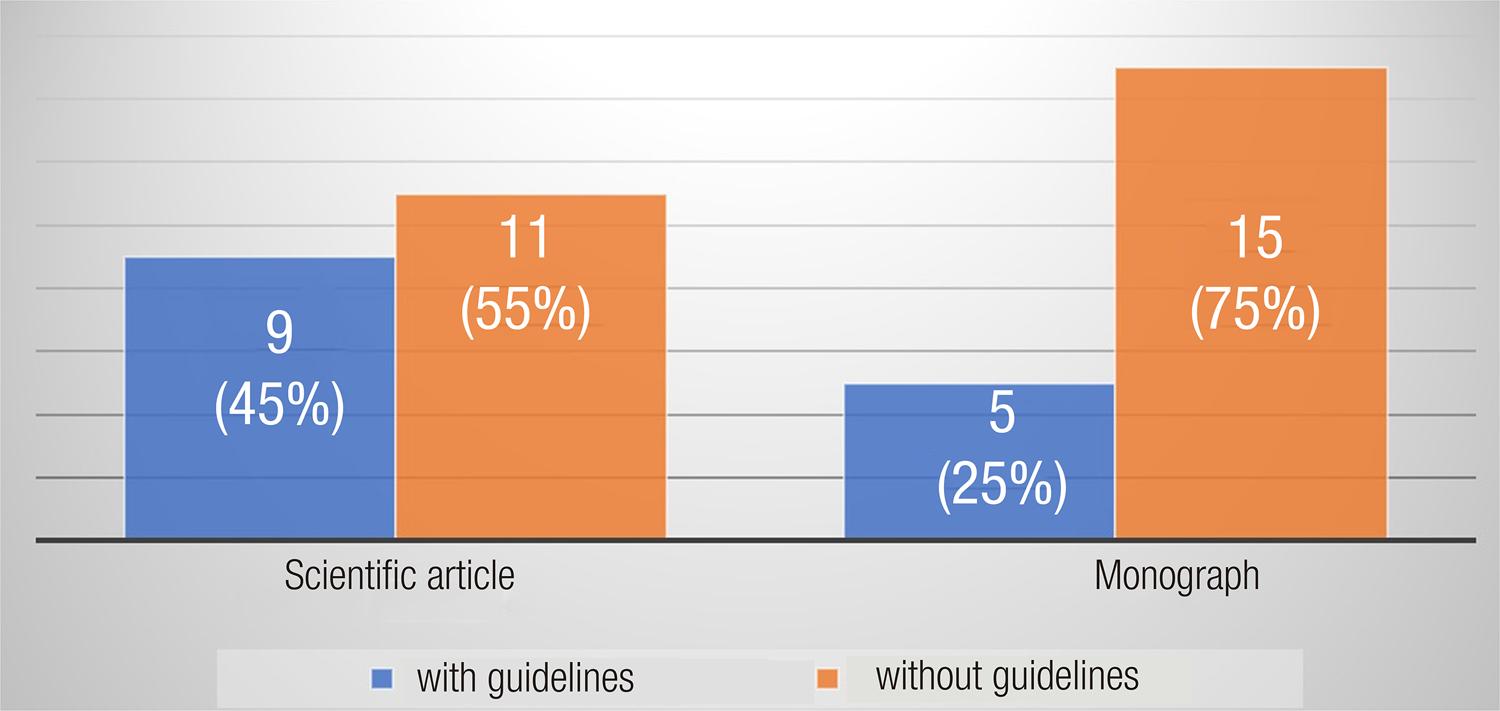

The understanding that has been established, at the theoretical level, that the production of texts is an interactive and procedural activity, in which successive stages and cooperative / collaborative work between subjects are involved (ANTUNES, 2003; SUASSUNA, 2011), it seems, as indicates our analysis, not yet having found the due and expected space on the examined sites and blogs. Given the recognized importance that revision and rewriting have for the improvement of writing, we found that the presence of guidelines on these stages of the textual production process is very timid and restricted, both due to the space / textual volume that is destined for them (at most of the times, restricted to, on average, 10 lines) and the recurrence of sites and blogs that bring some type of guidance. Our reading can be ratified by means of a quantitative survey of the recurrence of the presence of the guidelines on the websites and blogs examined, shown in the graph below:

Although the sites and blogs examined have guidelines on revision and textual rewriting, the data in the graph demonstrate the existence of a smaller number of sites and blogs, both in those dealing with the monograph genre (which corresponds to 75%) and in those that focus on genre scientific article (corresponding to 55%), which explicitly present guidelines with this focus. In both cases, the percentage of sites and blogs that do not have guidelines exceeds 50%, proving to be very expressive when it comes to the presentation of guidelines for the production of the monograph genre.

The higher percentage of websites and blogs that provide guidance on the review and rewriting of scientific articles may be an indicator that the focus on a broader audience and on publication in qualified journals tends to induce the emphasis that is given, in these guidelines, to crucial role of the act of text revision. As the monograph is a genre that, as a rule, is more restricted to the context of completion of undergraduate or graduate courses lato sensu, without a clearer perspective of publication in journals, and, furthermore, considering the condition of less experienced researcher or in the beginning of a graduate student’s own training, the value of revision and rewriting ends up, unfortunately, being minimized in this context.

In spite of this, realizing that these sites and blogs explicitly bring these guidelines is, in some ways, encouraging, although, of course, it cannot be denied that there is a necessary gap to be filled, if we think of disseminating, among undergraduate students and early career researchers, the value of reviewing and rewriting texts as inseparable from writing (ANTUNES, 2003; PASQUIER; DOLZ, 1996; SUASSUNA, 2011), given the need we face to invest a little more in training in and for scientific writing during graduation.

Considering that the analysis above points to the existence of a space, although still restricted, for the presentation of guidelines on revision and rewriting of scientific texts on the websites and blogs researched, we must examine how, in these guidelines, revision and rewriting are designed and adressed.

Analizing the corpus allowed us to identify some aspects related to the review and rewriting of scientific texts that are contemplated / focused on the guidelines of the analyzed websites and blogs. The contemplated / focused aspects that we identified were organized into 5 categories of analysis, namely: i) recognition of the importance and need for review and rewriting; ii) indication of participants / subjects involved; iii) delimitation of elements / aspects of the text to be revised; iv) delimitation of the number of revisions and / or rewrites; and v) indication of temporal distance.

i) recognition of the importance and need for revision and rewriting

Although not all sites and blogs give, in fact, due importance to the revision and rewriting of texts, judging by the space reserved for them, 03 (three) of them are very emphatic in highlighting the importance and need to practice the review and rewrite it, especially in the context of writing a scientific article for publication in journals.

(1)

It is worth mentioning that the two previous tips are related to a very important part of the elaboration of your work: the review. Don’t skimp on this step - it is crucial to the final result. (OAC8) (emphasis added).

(2)

One thing you will learn in the first few conversations with your monograph advisor is that text revision is extremely necessary to arrive at an appropriate final result. You will write the text, revise and forward it to your advisor. [...]. You may be irritated, your teacher may demand too much, the deadline may tighten a few times, but this is all part of university life. Take a deep breath, go back to the books, reopen your text editor and focus on the text some more. (OM9) (emphasis added).

It is possible to notice, in the two excerpts, that the textual revision / rewriting is conceived as a fundamental moment in the process of writing scientific texts, being valued as a crucial and extremely necessary step to obtain an appropriate, quality product. We observe there the idea that, however complex, costly and demanding the route from the first version to the final text may be, the producer should not save efforts to produce a quality scientific text and be successful in scientific publication (MUNGER, 2016).

In addition, we observe, especially in excerpt 2, a demonstration that, as far as it is necessary to practice text revision and rewriting, it is crucial that the producer, especially the one at the beginning of his/her career, learns / assimilates the essential role of revision and rewriting in qualification of the final version of a monograph or scientific article. This 0M9 orientation signals the understanding that it is still quite challenging to make the student, especially undergraduate, understand and accept the need to revise and rewrite their texts.

ii) indication of the participants / subjects involved in the text revision scene and rewriting

Not all guidelines analyzed by us mention and / or explicitly assume the writing of scientific texts as an interactive and collaborative process, which may involve the participation of interlocutors, especially in the path between the initial and final version of a text (GARCEZ, 2010; SUASSUNA, 2011). There are, however, 08 (eight) websites and blogs, among the 14 (fourteen) that present guidelines, mentioning the need for the producer, whether of the scientific article or the monograph, to consider an interlocutor to collaborate with the revision and rewriting of the text. .

In the passages that we reproduce below, there are explicit indications that the producer can count on different interlocutors in the process of review and textual rewriting:

(3)

If possible, it is very worthwhile to submit the article to another reader, who may be your professor, a colleague in the field or even a review professional - this detail will make all the difference. In any case, allow a few days for this review on your schedule. (OAC8) (emphasis added).

(4)

Don’t make banal mistakes. Checking spelling is the first step towards completing your monograph! Use computer programs that perform this task and / or get a friend or teacher to review for you. (OM19) (emphasis added).

In excerpts (3) and (4), the guidelines regarding the production of the scientific article and the monograph clearly indicate the possibility for the producer to dialogue, in the stages of revising and rewriting the texts, with at least four possible interlocutors: the teacher, a colleague, a friend and a specialized professional.

We can consider that, depending on the contacts network established, the writing producer can count on one or more interlocutors, a colleague and a teacher, for example, to contribute to the writing / revision of his text, working with a mediator in this process (SUASSUNA, 2011). When, for example, it is produced in a research team, and / or the text has more than one author, the work of revision and rewriting tends to be more exercised and, therefore, collaborate much more to improve the final version of the text, as the following excerpt proves: “Generally, scientific articles are produced by several authors, which allows the work to undergo reformulations based on the reading of others”. (OAC14).

It is interesting to note that, both in the excerpts (3) and (4) and in the other guidelines of the websites and blogs examined, there is no reference to the advisor as an interlocutor to collaborate with the review and rewriting work. This, in a way, explains to us that, although he may exercise this activity to some extent, revising and rewriting are not the duties of an advisor, as, mistakenly, many still make us think.

There are cases of guidelines that mention only the text producer himself as executing the review, stressing, however, that this activity should not be done immediately after the act of writing the first version of the text: few days before submitting it to the selected journal. After a few days without thinking about it, do a review of the article”. (OAC1). There are also, in the blogs and websites analyzed, guidelines that indicate that the producer should resort to an English proofreader, especially when publishing a scientific article in an international journal. However, this does not, of course, dispense with previous work of revising and rewriting the text, in the mother tongue, which includes other interlocutors.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the allusion, found in the excerpt (2), to the possibility of using computer programs in the work of revision and rewriting, whose indication suggests a rather narrow view of the revision and rewriting activity, since, as we know, a resource of this type, due to its automatic functioning, does not account for the complexity that covers the textual and discursive plot that constitutes a complex statement (BAKHTIN, 2016), such as a scientific article or a monograph, for example. Such a resource can be useful, at most, to account for more punctual aspects that cover spelling, lexicon, syntax and agreement in less complex sentence structures. However, it can never be the only alternative that should be used by a text producer concerned with the message (in its content and in its form) that he/she intends to convey to his/her interlocutors / readers.

As noted in some of these excerpts, the lack of indication made by an experienced and effective mediator (SUASSUNA, 2011), who guides and makes interventions, suggests the absence, in the activity of written production, of the judgment of another subject that favors, according to Antunes (2013), the identification of problems and the pointing out of necessary corrections to the adequacy of the text.

iii) delimitation of elements of the text to be revised

What to review? What elements should be pointed out in the review and considered in the rewriting of texts? Such inquiries, which are essential to the discussion on the theme in focus, were the object of our observation at the analyzed websites and blogs. As already indicated, a revision and rewriting work that takes into account the effectiveness of the practice of producing texts in concrete situations of interaction (GERALDI, 1997) and that considers the complex and multifaceted functioning of language in statements such as the discursive genres from Scientific sphere of research must contemplate multiple elements of the functioning of these genres, from those of a strictly linguistic order to those of a textual, discursive and / or enunciative order (PASQUIER; DOLZ, 1996). Therefore, it is necessary to consider the dimensions of the content, the compositional structure and the style, constitutive and typical of the statements of the scientific sphere (BAKHTIN, 2016).

The examination of blogs and websites points to a primacy of revision and rewriting guidelines focused on linguistic elements, with a very strong emphasis on grammatical aspects, spelling errors and punctuation problems, as we can see in the excerpts below:

5)

Eliminate as many grammar errors as possible.

For this you must read and reread as much as necessary. Spelling errors are unacceptable in scientific articles. Remember, too, to be careful with the punctuation! (OAC20) (emphasis added).

(6)

Text revision carried out by a third person is essential, as the writer has read the work many times and can miss some grammatical or syntax inconsistency that a third person detects at the time. Sometimes it is necessary to rewrite a sentence or adjust the tenses, or other details that the monograph does not even notice. (0M13) (emphasis added).

The concern with the presentation of guidelines centered, almost always, on elements such as those highlighted above is manifested in the guidelines on review and rewriting of both the monograph and scientific article genres, with a greater emphasis on those aimed at the production of the monograph genre. These guidelines, however, do not indicate, in most cases, which grammatical aspects should be focused, with the exception of OM13, in which we can verify the mention of the aspect of syntax and the use of verb tenses, without, however, presenting a better contextualization and exemplification of these issues.

Although the focus is on presenting revision and rewriting guidelines centered on elements of a linguistic nature, there is room for other elements, such as, for example, technical standardization (OM13, OAC3 and OAC15) and language translation (OAC3), mainly when it comes to the production of the scientific article genre for publication in specialized journals. There is also space for elements that cover the textual dimension involved in the functioning of language, when, in the guidelines, concern with “coherence of ideas”, “logical content” and “language” appears:

(7)

Look for spelling and / or grammatical errors. Make sure that all content is logical, consistent and noticeable. Following this crucial step, your monograph project will certainly be an impressive and professional job. (OM14) (emphasis added).

(8)

The ideal is to review your article at least twice. One to detect content problems (repeated ideas or loose ends in the text, for example), and another to assess language and grammar. (OAC8) (emphasis added).

Excerpts (5), (6), (7) and (8) confirm the reductionist and generic direction of the guidelines now analyzed in relation to the elements that must be considered in the stages of review and textual rewriting according to an interactional perspective (GERALDI, 1997; ANTUNES, 2003) of language. As we can see, any reference to the situation of enunciation, the dimension of the compositional structure of the text, as well as stylistic choices (which involve, among other aspects, the management of voices, the use of modalizers and the use of verbal people) that signal the enunciative-discursive functioning that characterizes every form of communicative interaction (BAKHTIN, 2016).

Thus, a representation is produced that textual revision and rewriting are much simpler activities than they actually are, even though grammatical cleaning and spelling and punctuation correction are not easy exercises for any writer. It is not by chance that, on the analyzed websites and blogs, we found the suggestion of delegating such tasks to grammar checkers and / or specialists in these activities.

iv) delimitation of the number of revisions and / or rewrites

When it is understood that writing is a procedural activity, the idea that writing and rewriting comprises an interactive movement of comings and goings over the text is necessarily implied (ANTUNES, 2003). In this sense, producing a text of a scientific nature tends to involve various and successive interventions, especially when it comes to improving a product. Such conception directs the understanding that the work of revision and rewriting may imply several interventions on the initial version of a text, after all, the look of one (or more) interlocutor opens infinite possibilities for improving the quality of a text.

In the guidelines of 3 (three) of the websites and blogs examined, the understanding of successive interventions in the writing of the scientific text appears emphasized in relation to the aspect of the amount of revisions / rewrites necessary for the production of scientific articles and monographs. Below, we illustrate two of these cases:

(9)

You will do the text, revise and forward it to your advisor. In turn, the teacher will look, suggest corrections, change some points and return the work to you. This dynamic will repeat itself dozens of times until the deadline and the final version of your monograph. (OM9). (Italics are ours).

(10)

Some people find it easier, while others demand more time and training to produce quality texts. The tip is: write and rewrite as many times as necessary. Don’t save on pencils and erasers or time typing and erasing. You can only learn to write by writing. (OAC10) (emphasis added).

We can observe that the guidelines seek to value the work of revising and rewriting the scientific text, emphasizing the need for the revision and rewriting to comprehend several moments of the producer’s return to his / her text. There is, therefore, an explicit indication that this practice is carried out from a minimum of twice to an undetermined quantity, the appropriate measure of which is defined by the producer’s need. In the other sites and blogs where there are guidelines for revision and rewriting, there is only an explanation of revising the text, without worrying about indicating any quantity.

It is not a matter, of course, of assuming an alleged existence of a prescription in relation to the need to carry out a certain number of revisions / rewrites or to support the idea that the more often it is practiced, the better the final product will be. After all, it is necessary to consider that the fundamental thing is “to write and rewrite as many times as necessary” due to the adequacy of the text to the purposes, the communicative situation and the interlocutors involved. It is clear that it does not concern a bureaucratic task, to fulfill a school requirement (GERALDI, 1997), but an activity designed with a view to a communicatively successful verbal performance (ANTUNES, 2003), for which the continuing revisions and as many times as necessary are a dynamic of the communicative action of the text-producing subject.

v) indication of temporal distance

The temporal dimension is conceived as an element that characterizes the activity of producing texts in a procedural, interactive perspective, as highlighted by the discussions undertaken in the fields of language and education, some of which are pointed out in the theoretical section of this work. These discussions propose to consider a time between the first version of a text and its final version, understanding that the temporal distance contributes so that the producer can look at his/her text as a reader and / or reviewer, allowing, as Pasquier and Dolz (1996), greater freedom of action in the final work. This aspect is emphasized in guidelines of 5 (five) of the investigated sites and blogs, of which we reproduce 2 (two) extracts by us considered more representative:

(11)

Throughout the process described above, it is important to always try to distance yourself from the manuscript and try to revise it with “reviewer’s eyes”. If that work had been submitted for publication by another group, what would be your criticisms of the work as a someone who revises texts? I often leave the article “in the drawer” for a few weeks before submitting it. (OAC6) (emphasis added).

(12)

But don’t even think about text revision right after writing! The text needs to “rest” for a few days (and so do you!). Especially because hurried readings are never able to detect flaws in the text well. (OAC8) (emphasis added).

We can verify, in the 2 (two) excerpts above, the aspect of temporal distance as an important posture to be taken by the producer of scientific texts, as a condition for the improvement of the product via the process of review and textual rewriting. The idea of the time gap necessary for the textual production process reiterates that it is not possible to revise and rewrite the text immediately upon the execution / operation of writing.

The guidelines examined indicate that the “failures”, “errors” and problems that may go unnoticed in a first version of the text can be remedied by assigning a moment / time when the text is left “in the drawer”, for “ rest”, before finishing it. On the websites and blogs, the defense of “one or two days”, “a few days” and “a few weeks” is made very clear as a necessary temporal measure for the producer to turn over his text.

This direction of temporal distance, even if it does not materialize in most of the blogs and websites analyzed, is fundamental as a possibility to conceive, according to Suassuna (2011), the displacement of the producer from his position of enunciator to the position of reader, allowing that he (producer) can, therefore, reflect on his choices and evaluate them in the reconstruction of his text, an essential posture, especially for those who intend to produce a scientific text for publication in specialized journals.

The analysis of the presence of guidelines on revision and rewriting of scientific texts and the way in which such guidelines conceive and guide these activities indicates that the websites and blogs examined pay little attention to these fundamental stages in the process of producing scientific texts of the genres monograph and scientific article. Given the emphasis placed on the production of scientific articles for publication in journals, we can perceive a greater focus on aspects of the revision and rewriting of this genre, which end up being explored without necessarily considering their constituent specificities, nor those that characterize disciplinary cultures (NAVARRO, 2014; CARLINO, 2017).

Our analysis confirms, moreover, that there are few sites and blogs in which a concern with textual revision and rewriting is evident as interdependent moments in the practice of textual production, understood as interlocutive, procedural, interactive activity, in which the action of the producing subject about his own text.

Conclusion

Encouged by the interest in understanding sayings and knowledge about the writing of scientific texts that are given to broadcast in the internet universe, we aim to ask ourselves about the treatment given to the revision and rewriting of texts in materials of an educational / instructive nature, taken from the internet, and intended to provide guidelines for the development of scientific text writing.

Based on researchers who discuss scientific writing, textual production and revision and rewriting of texts, and a corpus clipping consisting of 40 texts with guidelines on the production of scientific articles and monographs collected on websites and blogs, we seek to examine the extent to which the exerpts include guidelines and / or suggestions on the activities of revising and rewriting scientific texts and how they conceive and direct / direct the development of these activities.

The results of the analysis undertaken here confirm that, although they are widely discussed in the field of language studies and education, the review and rewriting of texts do not receive due attention in the guidelines presented in the examined texts. On the contrary, we were able to observe a very small presence of guidelines that explain the importance and the need to review and rewrite as steps inherent to the production of scientific texts.

In addition, it was possible to observe the existence of a very restricted space of guidelines that emphasize and value the interlocutive, interactive and procedural dimensions that constitute communicative practices. It is not by chance, even, that the more formal aspects of the language prevail when explaining the elements to be pointed out and considered in the process of revising and rewriting the texts. This reveals, therefore, a restricted view of the functioning of language in scientific writing, which is, considering the specificities and conventions of the academic-scientific sphere, complex and multifaceted by nature (BAKHTIN, 2016).

Therefore, these results demonstrate that, although they offer advantages inherent to the digital universe, such as, for example, facilitating access and considering the readiness of readers to learn in their time, most of the analyzed websites and blogs have a markedly commercial, focused, for the provision of text revision, translation and advisory services for the preparation of monographs, dissertations, among other genres of discourse. Thus, we understand that, although some of the guidelines analyzed are, to some extent, relevant and productive for readers, especially for those who practice faster reading of texts that circulate in the internet universe, the evaluation made of the set of texts in the corpus reveals that most of the analyzed websites and blogs contemplate, in a precarious and restricted way, aspects involved in the practice of writing and rewriting scientific texts, contributing, more often than not, to produce a fragmented image of what is effectively the practice of producing texts in the scientific sphere.

Therefore, it is prudent to consider and warn that a significant part of these sites and blogs does not constitute a source of information and / or research that is fully adequate and satisfactory, especially when considering the preparation / training of the reader / producer for a successful verbal performance in production of scientific texts. Thus, we realize the need that we have to train undergraduate students and researchers at the beginning of their careers capable of developing a critical reading of these materials available in the digital universe.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Wanderleya Magna; BESSA, José Cezinaldo Rocha. As orientações para escrita e reescrita de textos em livro didático de língua inglesa do ensino fundamental. Calidoscópio, São Leopoldo, v. 16, p. 369-379, 2018a. [ Links ]

ALVES, Wanderleya Magna; BESSA, José Cezinaldo Rocha. Orientações para escrita da redação do Enem em vídeos do Youtube. Hipertextos Revista Digital, Recife, v. 19, p. 1-23, 2018b. [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Irandé. Aula de Português: encontro & interação. São Paulo: Parábola, 2003. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Os gêneros do discurso. Organização, tradução, posfácio e notas de Paulo Bezerra. São Paulo: 34, 2016. [ Links ]

BELOTI. Adriana; MENEGASSI. Renilson José. A constituição teórica, metodológica e prática sobre revisão e reescrita na formação docente inicial-PIBID. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 06, n. 01, p. 9-32, jan./jun. 2017 [ Links ]

BERNARDINO, Rosângela Alves dos Santos et al. Escrita e reescrita de textos acadêmicos: reflexão sobre os apontamentos de correção do professor. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 3, n. 2, p. 39-58, 2014. [ Links ]

CARLINO, Paula. Escrever, ler e aprender na universidade: uma introdução à alfabetização acadêmica. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Elisa Cristina Amorim; ARAÚJO, Denise Lino. O (não) funcionamento da reescrita em textos produzidos por licenciandos em letras. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, Campinas, v. 53, n. 1, p. 201-224, 2014. [ Links ]

GARCEZ, Lucília Helena do Carmo. A escrita e o outro: os modos de participação na construção do texto. Brasília, DF: Universidade de Brasília, 2010. [ Links ]

GASPAROTTO, Denise Moreira; MENEGASSI, Renilson José. A mediação do professor na revisão e reescrita de textos de aluno de ensino médio. Calidoscopio, São Leopoldo, v. 11, n. 1, p. 29-43, 2013. [ Links ]

GEHRKE, Nara Augustin; CABRAL, Sara Regina Scotta. A reescrita e a qualificação do processo de produção de microcrônicas verbo-visuais. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 06, n. 01, p. 127-149, jan./jun. 2017. [ Links ]

GERALDI, João Wanderley. Portos de passagem. 4. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1997. [ Links ]

LAVILLE, Christian; DIONNE, Jean. A construção do saber: manual de metodologia da pesquisa em ciências humanas. Tradução de Heloísa Monteiro e Francisco Settineri. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 1999. [ Links ]

MAFRA, Gabriela Martins; BARROS, Eliane Merlin Deganutti de. Revisão coletiva, correção do professor e autoavaliação: atividades mediadoras da aprendizagem da escrita. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 6, n. 1, p. 33-62, jan./jun. 2017. [ Links ]

MARQUESI, Sueli Cristina. Escrita e reescrita de textos no ensino médio. In: ELIAS, Vanda Maria (org.). Ensino de língua portuguesa: oralidade, escrita e leitura. São Paulo: Contexto, 2011. p. 135-143. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Cínthya da Silva; ARAÚJO, Nukácia Meyre Silva. A prática de revisão orientada de dissertações de mestrado: as sugestões do revisor-leitor, as estratégias do revisor-autor. Signum, Londrina, v. 15, n. 2, p. 257-287, 2012. [ Links ]

MENEGASSI, Renilson José; FUZA, Ângela Francine. Revisão e reescrita de textos a partir do gênero textual conto infantil. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 1, n. 1, p. 41-56, 2012. [ Links ]

MUNGER, Michael. 10 tips on how to write less badly. In: Focus Chronicle of Higler Education (ed.). A guide to writing good academic prose. Washington, DC: [s. n.], 2016. p. 11-12. Disponível em: https://www.chronicle.com/resource/a-guide-to-writing-good-academ/5877/. Acesso em: 30 fev. 2018. [ Links ]

NAVARRO, Frederico. Géneros discursivos e ingresso a las culturas disciplinares: aportes para uma didáctica de la lectura y la escritura en educación superior. In: NAVARRO, Frederico. (coord.), Manual de escritura para carreras de humanidades. Buenos Aires: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2014. p. 29-52. [ Links ]

PAGLIARUSSI, Marcelo Sanches. Estrutura e redação de artigos em contabilidade e organizações. Revista de Contabilidade e Organizações, Ribeirão Preto, v. 11, n 31, p. 5-10, 2017. [ Links ]

PASQUIER, Auguste; DOLZ, Joaquim. Um decálogo para ensinar a escrever. Cultura y Educación, Madrid, v. 2, p. 31-41, 1996. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Regina Celi Mendes; LEITÃO, Poliana Dayse Vasconcelos. Mediação formativa na prática de elaboração de artigos científicos. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 6, n.1, p. 63-88, 2017. [ Links ]

PINTON, Francieli Matzenbacher. A reescrita do bilhete orientador pelo licenciando em letras: uma prática reflexivo-crítica no processo de avaliar textos. Leia Escola, Campina Grande, v. 11, n. 2, p. 9-24, 2012. [ Links ]

RUIZ, Eliana. Como se corrige redação na escola. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2010. [ Links ]

RUSSEL, David. Letramento acadêmico: leitura e escrita na universidade. Conjectura, Caxias do Sul, v. 14, n. 2, p. 241-247, 2009. Entrevista realizada por Flávia Brocchetto Ramos Vânia Marta Espeiorin. [ Links ]

SCHALKOSKI-DIAS, Luzia; NICOLA, Rosane de Melo Santo. A perspectiva pragmática na avaliaçã formativa: caminhos para a formação do professor mediador na revisão textual. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 06, n. 01, p. 199-222, jan./jun. 2017. [ Links ]

SIGNORINI, Inês; CAVALCANTI, Marilda. Linguística aplicada e transdisciplinaridade: questões e perspectivas. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

SUASSUNA, Lívia. Avaliação e reescrita de textos escolares: a mediação do professor. In: ELIAS, Vanda Maria (org.). Ensino de língua portuguesa: oralidade, escrita e leitura. São Paulo: Contexto, 2011. p. 119-134. [ Links ]

2- The texts that make up the corpus were coded by us, observing the following identification: OAC1, OAC2, OAC3, and so on, where O corresponds to the Orientation, AC refer to the initial letters of the term Scientific Article, and the numerals cardinals 1, 2, 3 ... correspond to the numerical order, established randomly, of the texts in our corpus. When, instead of AC, we use M, it means that the encoding refers to the Monograph.

Received: June 24, 2019; Revised: October 08, 2019; Accepted: November 12, 2019

texto em

texto em