Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.47 São Paulo 2021 Epub 10-Mar-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202147237848

THEME SECTION: Childhood, Politics and Education

2- Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina. Contacto: axelcesarhorn@gmail.com.

This paper presents the ideas that boys and girls have about the right to privacy at school, emerging from research conducted in the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The boys and girls studied are between the ages of 7 and 12. The article shows which group of ideas were developed by these subjects. In this research, clinical-critical interviews were used as a methodological strategy, based on the presentation of narratives addressing the violation of the right to privacy in schools. The resulting ideas are divided into three main groups: one group of subjects does not recognize this right, another recognizes it, although limited to those situations where this right strains some school characteristic, and a smaller group of subjects recognizes the right independently of the characteristics of the school. The article postulates that the construction of childhood ideas about the right to privacy occurs through hard intellectual work while participating in institutional contexts that are not always careful of children’s personal information. The results exposed facilitate the discussion on the situated construction of social notions by the subjects and the characteristics assumed by development from a psychological constructivist perspective that puts the social context in which the subjects participate at the center. The questions ordering the discussion are as follows: Does conceptual development exist in this type of social ideas? If so, in what terms can it be raised?

Key words: Right to privacy; School; Social knowledge; Knowledge development

Se presentan las ideas infantiles de los niños y las niñas sobre el derecho a la intimidad en la escuela, surgidas de una investigación realizada en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires de la República Argentina. Los y las niñas estudiados/as tienen entre 7 y 12 años. El artículo muestra cuales son los grupos de ideas elaborados por estos sujetos. En la investigación se utilizó como estrategia metodológica entrevistas clínico-críticas a partir de la presentación de narrativas en las que se planteaba la vulneración del derecho a la intimidad en la escuela. Las ideas encontradas se dividen en tres grandes grupos: un grupo de sujetos no reconoce el derecho, otro lo reconoce, pero limitado en aquellas situaciones en las que dicho derecho tensiona alguna característica escolar, y un grupo menor de sujetos reconoce al derecho independiente de las características de la escuela. El artículo postula que la construcción de las ideas infantiles sobre el derecho a la intimidad se produce por una trabajosa labor intelectual mientras participan en contextos institucionales que no siempre son cuidadosos de la información personal de los y las niñas. Los resultados expuestos posibilitan una discusión acerca de las formas de construcción situada de nociones sociales por parte de los sujetos y las características que asume el desarrollo desde una perspectiva psicológica constructivista que pone en el centro el contexto social en el que los sujetos participan. Las preguntas que ordenan la discusión son las siguientes: ¿Existe desarrollo conceptual en este tipo de ideas sociales? De existir ¿En qué términos puede ser planteado?

Palabras-clave: Derecho a la intimidad; Escuela; Conocimiento social; Desarrollo cognoscitivo

Introduction

In the field of developmental psychology, there has been some research on the acquisition of social notions (KARMILOFF-SMITH, 1994; HIRSCHFEL, 2002; CASTORINA; FAIGENBAUM, 2000; CASTORINA; LENZI; FERNÁNDEZ, 2000). Not many of these studies describe the conceptual constructions of specific rights held by children, and fewer still refer to their ideas of the right to privacy.

This vacancy has some exceptions in the specific field of Piagetian-inspired psychology where research has been done on the ideas held by children about privacy, intimacy, secrecy, and their rights (HELMAN; CASTORINA, 2005, 2007; HELMAN, 2010; HORN; CASTORINA, 2010; FERREYRA; HORN; CASTORINA, 2012, 2018; LA TAILLE; BEDOIA; GIMÉNEZ, 1991; LA TAILLE, 1995, 1996, 1998).

However, far from being a compact and undifferentiated set of studies on a common theme, theoretical and methodological divergences abound. According to some -Helman and Castorina (2005, 2007), Helman (2010), Horn and Castorina (2010), Ferreyra, Horn and Castorina (2012)- the conceptual construction of notions about the right is inseparable from the participation of the subject in contexts where the right or the notion has a given place and fulfillment. Instead, other researchers, such as La Taille (1995, 1996), suggest that this type of notion is developed by boys and girls regardless of the social conditions under which the subject participates. In this way, an individual cognitive process that would be carried out in solitude is sustained.

The first purpose of this article is to present the results of an investigation describing the development of the conceptualizations that children hold concerning the right to privacy in school. Secondly, it aims to raise a discussion around the concept of development. More specifically, can the notion of the development of social notions that are strongly linked to child participation in specific contexts still be sustained? And if sustained, under what conditions can this be done?

Research about childhood ideas regarding privacy and its right

Researcher Yves de La Taille (1991, 1995, 1996; BATAGLIA; FERREIRA; SALADINI, 2020) has studied the genesis of the notion of secret and its right and other moral phenomena, as well as the construction of a moral boundary for intimacy.

From the perspective of the author, the consolidation of these notions is part of the constitution of psychism. Establishing that some aspects of our personal lives will be considered secret implies the recognition of a private space beyond the intervention of others. In this direction, the author interprets the construction of a boundary for intimacy, following Altman (1979), in terms of a “[...] frontier between one and others that guarantees a limit to the process of social interaction” (LA TAILLE; BEDOIA; GIMÉNEZ, 1991, p. 92). The author’s thesis supporting an intimate boundary as a universal fact, without considering its historicity, is debatable. Moreover, according to his proposal, this frontier is reached as a result of human nature:

[...] privacy seems to correspond to a human need, and while it is true that its forms vary in different times and cultures, it is also true that its presence is always identifiable. (LA TAILLE, 1998, p. 137).

We are particularly interested in the study by La Taille, Bedoia, and Giménez (1991) on the genesis of the right to secrecy. Their research finds that from the age of four, boys and girls recognize they may have secrets, although they do not consider this to be a right. It is constructed later: eight-year-old boys and girls may recognize their right to withhold certain personal information when requested by another child, but they only assert such a right with adults at the age of 12 or 13, while considering it more convenient to provide them with this information if requested.

How does the author explain this evolution of the notion of a right to secrecy? He is inspired by Piagetian theory and holds that the consolidation of the idea of this right at the age of eight years is due, at the individual level, to the construction of operational reversibility enabling the establishment of intellectual autonomy. At the social level, this is the moment when the decentralization of the actions of the self takes place, together with coordination with the actions and communications of others. Piaget (1971) referred to this social relationship as cooperation, claiming that it leads to the construction of moral autonomy. This is seen in La Taille:

Age 8 is a “turning point” in many psychological development areas. It is the time for the first achievements in operational reversibility, consequently of intellectual autonomy (Inhelder and Piaget, 1953). In terms of social relations, it is also a period in which mutual coordination of actions and verbal exchanges begin, something Mead (1934-1972) called stage theater, and Piaget ([1932] 1971), cooperation. (1995, p. 448).

Among the problems presented in the cited fragment is the fact that it transfers an unmodified proposal used by Piaget to explain the elaboration of logical-mathematical concepts to the elaboration of social notions. In this way, a cognitive elaboration concerning the right to secrecy is understood as an individual construction, dependent on intellectual operations, unrelated to the specific social context the subject participates in and becomes aware of his or her rights. The author goes on to say:

In short, it is not surprising that, at the genesis of the secret, the same age marks the beginning of the moral conception of a new law and, let us remember, a new duty: keeping a secret confided by others. However, the age of 8 years in itself is not important (the age can certainly vary according to culture and personal experiences), but the fact that a moment of evolution can be verified when new psychological instruments and new values take place. If our analyses are correct, then the origins of secrecy are linked to other psychological conquests, particularly cognitive and moral ones. (p. 448).

In the preceding paragraph, the author derives the construction of social knowledge from a progression necessarily linked to age but fails to make it independent of general intellectual development regardless of the specific context where knowledge is produced. From other perspectives that we will work on next, the context of knowledge production contributes far more than merely the time in which a certain notion dependent on intellectual development appears, functioning as a constraint that enables a certain elaboration of ideas and makes others unfeasible.

Differing from these studies about conceptual construction of personal spaces, we find research undertaken by Helman and Castorina (2005, 2007) about children’s ideas of rights at school, which includes the right to privacy.

According to the results of this research, all interviewed subjects (boys and girls between 8 and 12 years old) recognize the right to privacy when they consider that the intervention of the teacher in their personal space is incorrect. In the author’s opinion, it is possible to think of a legal norm that regulates, for example, behaviors tending to preserve child privacy, only if the existence of a private field of acts is first recognized. The author defines the right to privacy as the recognition of a set of personal environments that the child can think of as a right. This research also shows that children who recognize the right to privacy generally understand it conditionally. Critical to a proper understanding of this theoretical perspective is the nature of these conditions. They are requirements that children think must be met before they can enjoy their right to privacy and are related to some guidelines for school practices. Thus, we find a recognition of the rights of the good student (HELMAN; CASTORINA, 2007), while those subjects of the sample who acknowledge the right to privacy understand that only those who do not transgress school rules will be able to enjoy it.

This research opens up the possibility to investigate and deepen the study of the characteristics of the ideas children have about their right to privacy. That is, to expand the sample to younger subjects and to explore whether other conditions exist that children consider must be met to gain the right in question.

Problems and aims of the study

To study the ideas that boys and girls have concerning the right to privacy at school is to bring up the following question: on the one hand, schools are one of the contexts where subjects become aware of their rights as children; on the other hand, educational institutions intervene in their personal lives and promote other social norms that may contradict their intimate sphere, such as the construction of public space.

A discussion related to the legal attributions of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1989) is underway, presenting different perspectives that were being debated when it was elaborated (ROSENBERG; SUSSEL MARIANO, 2010). While promoting rights related to individual freedom, on the one hand, it establishes rights that protect children (such as those associated with child labor) on the other.

Authors Rosemberg and Sussel Mariano (2010) claim that this coexistence of two perspectives within the Convention expresses the political-ideological conflicts that are present in discussions between country representatives who were part of the working groups and the drafting of the Convention. According to this interpretation, if the Convention is the product of a political agreement between opposing parties, then the text might present certain conflicts between these different versions of childhood. From our point of view, it is indisputable that children are involved in dependant relationships and are clearly vulnerable. This must be considered. Otherwise, boys and girls - with their recognized rights to autonomy - run the risk of becoming dissociated from the necessary construction alongside adults of the conditions protecting their rights, given their responsibility towards generating conditions that fully comply with them.

This tension is transferred into school space. Although the International Convention on the Rights of the Child attributes children the right to privacy, attention must be drawn to a certain difficulty to ensure this right is implemented without tension in the school environment.

Regarding the school environment, in the words of Le Gal: “Just by reading a certain number of the central principles held in the Convention, it seems necessary to create another educational system for schools to become the school of the rights of children, freedom, and participatory citizenship” (2005, p. 44).

The recognition of the right to privacy conflicts with some aspects and characteristics of the school. In the first place, there is a set of institutional norms that can strain the respect for personal space, for example, the fact that a teacher is responsible for the care and protection of children makes him/her strongly involved in their lives. Secondly, we must not forget that if an intimate space alien to the school’s intervention is recognized by boys and girls, it might limit disciplinary aspects and surveillance.

This led us to elaborate on the following research questions: What ideas do children have about privacy? What characteristics do these ideas assume at school? Can any relationship be expected between school practices and ideas about the right to privacy? Which ones? How is this visualized in the ideas of children? Can we talk about the development of ideas about the right to privacy? In what terms?

These questions imply an interest in elucidating the relationships between children’s conceptual elaboration of the right to privacy at school and the school practices they participate in.

Specific aims of the study

To identify ideas about the right to privacy in elementary school for boys and girls from urban poverty contexts attending a public school in the city of Buenos Aires.

To establish whether a distinction can be made between levels of conceptual development in the arguments of the boys and girls interviewed.

To reconsider institutional restrictions concerning the formation of children’s ideas in the moral field.

Type of study

The present research proposes an investigation with an evolutional cross-sectional design of a qualitative and exploratory character.

Sample

The sample consisted of 30 subjects from ages 7 to 12 from urban poverty contexts (BATALLÁN; VARAS, 2002) who attend a public school in CABA (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), inhabitants of settlements and poor neighborhoods of La Boca area whose parents or guardians are low wage earners. This information was provided by the school’s Principal. The sample was selected to meet an initial research goal: to compare the ideas of middle-class children ideas, generically described in previous studies (HELMAN; CASTORINA, 2007, 2010; HORN; CASTORINA, 2010) with those emerging from this research. However, potential differences with previous investigations were not noted, and we found that specifying the characteristics of children’s ideas was of greater interest. The selection was intentional and non-probabilistic because a quota sampling method was used (HERNÁNDEZ SAMPIERI; FERNÁNDEZ COLLADO; BAPTISTA LUCIO, 1991).

When selecting the boys and girls, we prioritized those belonging to the same class group. Therefore, girls and boys are grouped by grade. The assumption behind this grouping is that school practices within a given group may influence that group’s ideas around the right. Subjects attending 2nd grade are between 7 and 8 years old, those attending 4th grade are between 9 and 10 years old, and those attending 6th grade are between 11 and 12 years old. The final layout is presented:

Table 1 distribution of boys and girls

| Grade | Girls | Boys |

|---|---|---|

| 2° | 5 | 5 |

| 4° | 5 | 5 |

| 6° | 5 | 5 |

Source: Elaborated by the author.

All interviews required prior informed consent from the respondents and the authorization of the accountable adult references.

Instruments for information gathering

To carry out the research objectives, personal interviews were conducted based on the Piagetian clinical-critical method guidelines (PIAGET, 1973; DELVAL, 2001). Such interviews enable the reconstruction of the children’s viewpoints and their particularities from a dialogue with the subject guided by the answers of the latter. Three stories were presented where a school authority violated a personal space.

We transcribed the three stories presented to the sample subjects around which the interview revolved3:

Narrative 1

A girl is sad because she has a problem at home. The teacher knows what is happening to her and decides to tell the rest of her classmates.

Narrative 2 -Taken from Helman (2007)

In the classroom, during class time, a girl writes a note and passes it to a classmate while the teacher is explaining. When the teacher finds out, she tells her to hand over the paper. The girl refuses to give her the paper with her writing on it. She tells her teacher she promises to put it away, but the teacher keeps telling her to hand it over. Then, the girl turns it in, and the teacher walks to one side of the room, unfolds the paper, and silently reads it.

Narrative 3

Juan leaves the classroom with his teacher’s permission. The teacher stays in the room with the remaining classmates. The teacher takes advantage by telling all the children that Juan has many conduct problems and behaves very badly. The teacher asks everyone to help him out.

Clinical-critical interviews imply a two-way interviewer activity: on the one hand, an expectation for the voice of childood to be expressed so that it can be reconstructed by the researcher (DUVEEN; GILLIGAN, 2013). Giving children a voice in child knowledge construction research provides an opportunity to promote their right to be heard (LEE, 2010).

On the other hand, there is the place given to theory during methodological activities to gather information, permitting their interpretation while being produced and cross-examination under the theoretical inquiries guiding the questions (CASTORINA; LENZI; FERNÁNDEZ, 1984; DELVAL, 2001).

Data analysis

Qualitative procedures were used to analyze the data obtained in the interviews. In this way, the categories were made based on recurrences and convergences of responses given by the subjects (DELVAL, 2001) and interpreted based on the theoretical framework.

Critical-clinical interview analysis involves constructing categories to be validated by other researchers. This is called an inter-rater agreement and aims to ensure its validity. The empirical material was submitted to two expert judges with 95% agreement, implying there was consensus in that percentage on the categories used to analyze the sample.

The ideas of children about the right to privacy

The following categories were developed as a product of the data analysis. It is worth noting that children’s rights, as sanctioned in the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, are understood by some legal scholars (LEIRAS, 1994) as a historically constructed expectation of desirable treatment. That is to say, that a social group understands and supports symbolically how subjects should be treated, even though this only implies the dimension of must be and is not always consistent with what actually happens. When we study the ideas that children have about some rights, we find that boys and girls have certain expectations of desirable adult treatment. This expectation may not always include respect for privacy. Thus, the categories reviewed here reflect different treatment expectations found in the sample.

A. Expectation of Benefit

The expectation of benefit is a set of children’s ideas that recognize that the actions of school authorities must be oriented to produce well-being in the child and prevent him/her from being harmed. Since it is a treatment expectation, we can consider it a recognition of certain legal reality (KOHEN, 2003). However, since we have not studied child ideas about rights that can be grouped within this expectation, we are unable to describe the richness of their ideas around them. However, we can consider the way this recognition may or may not be prioritized regarding the right to privacy. In many cases, when boys and girls were confronted with a narrative that violated the right to privacy, they understood that intrusion into their personal lives was facilitated by the teacher’s beneficent intention or the benefits that followed the intervention.

For example, in response to the presentation of Narrative 1, we find what Oriana said (7; 64) (Interview 2, p. 3):

Interviewer: Oriana, what do you think about what the teacher does?

Oriana: It’s okay

Interviewer: Why?

Oriana: Because afterward, they can help that girl in some way.

[…]

Interviewer: Why do you think the teacher can say that?

Oriana: Because in that way everyone helps her.

On this occasion (which is relevant to us), the subjects do not consider the violation of the right to privacy. The teacher’s action is interpreted as a legitimate intervention because she is a benefactor. In these cases, the subjects seem to focus their attention on the protection of children and the avoidance of harm to the detriment of respect for personal information. They are not balancing rights, an attitude one might attribute to boys and girls as jurists, making decisions about which right they feel is most relevant to respect. The situations presented are interpreted by a childhood conceptualization of benefaction expectation rather than the right to privacy involved.

For the subject, the violation of privacy rights is not considered observable. Instead, the situation is interpreted in the light of other treatment expectations that, according to Turiel (1984), arise early, associated with damage avoidance. Therefore, these ideas are relevant to the extent they may be interpreted as the first approaches to a conceptual elaboration of treatment expectation. However, this does not yet include the consideration of a right studied by us.

B. Respect for Privacy Expectations

We enter into the first acknowledgments of respect for privacy expectation. It can be conditioned or unconditioned. This marks a break with the preceding treatment expectation where respect for a boy or girl’s personal space was not recognized as part of it. Let us see an example (Interview 6, p. 4):

The interviewer shares narrative 1 and seeks the opinion of the interviewee on what the teacher is doing.

Brandon (7, 11): It is wrong.

Interviewee: Is it wrong? Why is it wrong?

Brandon: Because she told everyone, and the girl might get upset.

Interviewee: And why would she be upset?

Brandon: Because she doesn’t have to tell.

Interviewee: Why not?

Brandon: Because it belongs to her...

The relevance of these arguments is that they represent the first acknowledgments of personal space (LA TAILLE, 1996). The arguments grouped into this category reflect a recognition of the fact that teachers are not granted free access to students’ personal information.

B.1. Alternation of focus between respect for privacy expectation and benefaction expectation

We speak of focus alternation when the boy or girl alternately goes through recognition of their right to privacy and, other times, on the same narrative, they stop considering an expectation of respect for privacy to only consider a benefaction expectation. In these cases, there is no conditioning as no conditions have been conceived that limit the recognized right to privacy. Depending on the cognitive focus of the subject, he or she acknowledges the right to privacy or other treatment expectation. An example (Interview 22, p. 7):

After sharing the first narrative, the interviewer asks: And how do you feel about what the teacher did?

Gonzalo (10; 2): It’s okay.

Interviewer: Why?

Gonzalo: Because when you are in a class you shouldn’t play, you shouldn’t run, you shouldn’t pass papers, anything. That’s for recess.

[…]

Interviewer: Okay. Let me tell you: a boy your age said that maybe it was not ok for the teacher to take it and read it since it was a girl’s thing and she had no need to read it and get involved in girls’ things.

Gonzalo: That’s fine too.

Interviewer: How is that so?

Gonzalo: Because she has no business messing with the girls’ stuff

Interviewer: And how about what you said before that it was okay for her to read it since they were in class?

Gonzalo: Sure, both are fine.

B. 2. Respect for conditional privacy expectation

This classification implies the first level of distinction linked to our object of inquiry. However, this first recognition supposes the acknowledged expectation may be subject to different conditions. Within these categories, on the one hand, we find the child has a treatment expectation implying that his/her personal information should not be accessed. Nevertheless, this limit for accessing their personal space is bound to certain conditions the child or the situation must meet.

There are different conditions that subjects consider must be met to enjoy the right to privacy. It is for that reason that we group these conditions into three subcategories. However, this does not mean these subcategories are exclusive of each other. For a single subject, the right to privacy may be limited by more than one condition to be detailed in the subcategories. From a knowledgeable point of view, the distinction between an expectation of respect for privacy and the conditions that constrain it is relevant (Interview 13, p. 9).

Interviewer presents Narrative 2 and asks: What do you think about the teacher taking the note and reading it?

Jazmín (11; 02): On the one hand, it doesn’t seem fair to me because it could be telling something personal they don’t want anyone to know, and the teacher takes it...

Interviewer: So, you were saying, on the one hand, it seems unfair to me, does it seem unfair to you?

Jazmín: And yes, unfair teacher because she also has no reason to take that paper and read it without her knowing what it is.

Interviewer: What do you think the teacher should do?

Jazmín: Uh... call them both and talk to them.

Interviewer: And can she read the paper?

Jazmín: No.

Up to this point, there is a recognition of an expectation of respect for personal space. The interview continues (Interview 13, p. 9):

Interviewer: Now, suppose the girl is a girl who misbehaved, always passed papers in class, didn’t pay attention in class, and spent all her time passing papers in class. And the first time, the teacher didn’t read it, nor did the second time, but this third time, the teacher grabs it and reads it. What do you think about what this teacher does?

Jazmín: I think it’s because the girl disturbs others, and the others want to listen. It seems to me that the teacher has to grab the paper and read it to see what it’s all about that they’re passing papers around every day.

However, the recognition of an expectation of respect for privacy is conditioned by the girl’s school behavior.

The subcategories that condition the right to privacy are presented below.

The first one, is what we have called conditioned by the result of the action of the teacher. Within this subcategory, we subsume those children’s ideas where boys and girls register a personal space and an expectation of respect.

However, the beneficial outcome or avoidance of harm that school authority intervention may have on the child’s personal space seems to be more fundamental.

The second one, is conditioned by the teacher’s beneficial intention. This subcategory bears some resemblance with the former: in this case, a certain benefaction in the teacher’s intentions restricts the right to privacy. However, the difference is that the teacher´s intervention in the children’s personal space is granted because she intends to produce a positive effect on the girl whose personal space is violated.

The third one, is conditioned by the student’s anti-normative actions. Within this, we subsume the limit to a recognized right to privacy in those situations where students fail to behave according to the school’s disciplinary expectations and good school performance. In any event, no sharp differentiation can be made with the aforementioned conditions. This legitimizes the fact that, from a child’s point of view, interfering in their personal affairs fulfills a beneficial purpose involving the re-establishment of school order.

B.3 Expectation of unconditional respect for privacy

We say that the right to privacy is unconditional when respect for the boy or girl’s personal and intimate space is not subject to any other condition besides being a child. This is empirically referred to by the fact that the interviewed subject considers throughout the clinical interrogation, around the same narrative, that personal space should not be violated in any of the circumstances presented (such as, for example, that the girl who passes the paper has poor grades or does so repeatedly). We should point out that none of the subjects sustained unconditionality throughout the narratives presented, and only four sustained it in their considerations concerning at least one of the situations presented. One example (Interview 19, p. 3):

The interviewer shares the first narrative and asks: Well, what do you think of the story I told you?

Fabián (11; 7): If the girl has family problems, the teacher doesn’t have to tell the rest because it is a family problem of just one person.

Interviewer: Okay. Suppose the teacher tells all her classmates and her classmates help her, she doesn’t feel embarrassed, but they actually help her, right, and she feels better. In that case, how do you feel about what the teacher did?

Fabian: It’s okay. […] Because... that’s like asking her classmates for help, maybe the classmates talk to her so that they can give her some encouragement, and maybe those family problems will make her feel... if it’s a serious family issue, she’s going to feel... embarrassed.

Interviewer: Okay, but is it okay what the teacher does, or is it okay what the kids do?

Fabian: What the kids do is fine. What the teacher does... - It’s like, sort of okay, but she doesn’t have to tell children what happened in that way.

In this case, the boy considers the unconditionality of the right to privacy, meaning that no matter how much the teacher helps the girl by intervening, the existence of the right to privacy is not annulled.

In this journey through the ideas of children, we find support for our hypothesis that these notions are channeled, enabled, and limited by the participation of boys and girls in school practices from which the object is cut out. Their responses showed that the right to privacy at school is limited by some characteristics typical of school practices. This occurs in the idea we have called conditioned expectation of respect for privacy, where the recognized right to privacy finds its limit in the teacher’s beneficial intention or the student’s school performance. In other words, the data suggest that the very elaboration of children’s notions of a given right includes aspects of the specific context where it is elaborated: from their perspective, the right is suspended when the beneficiary contradicts the standards of that particular institution.

Discussion

We have shown the major milestones we found in the ideas of children, from the non-recognition of an expectation of respect for privacy to its episodically unconditioned recognition. A discussion around the concept of idea development underlies this presentation (CHAPMAN, 1998).

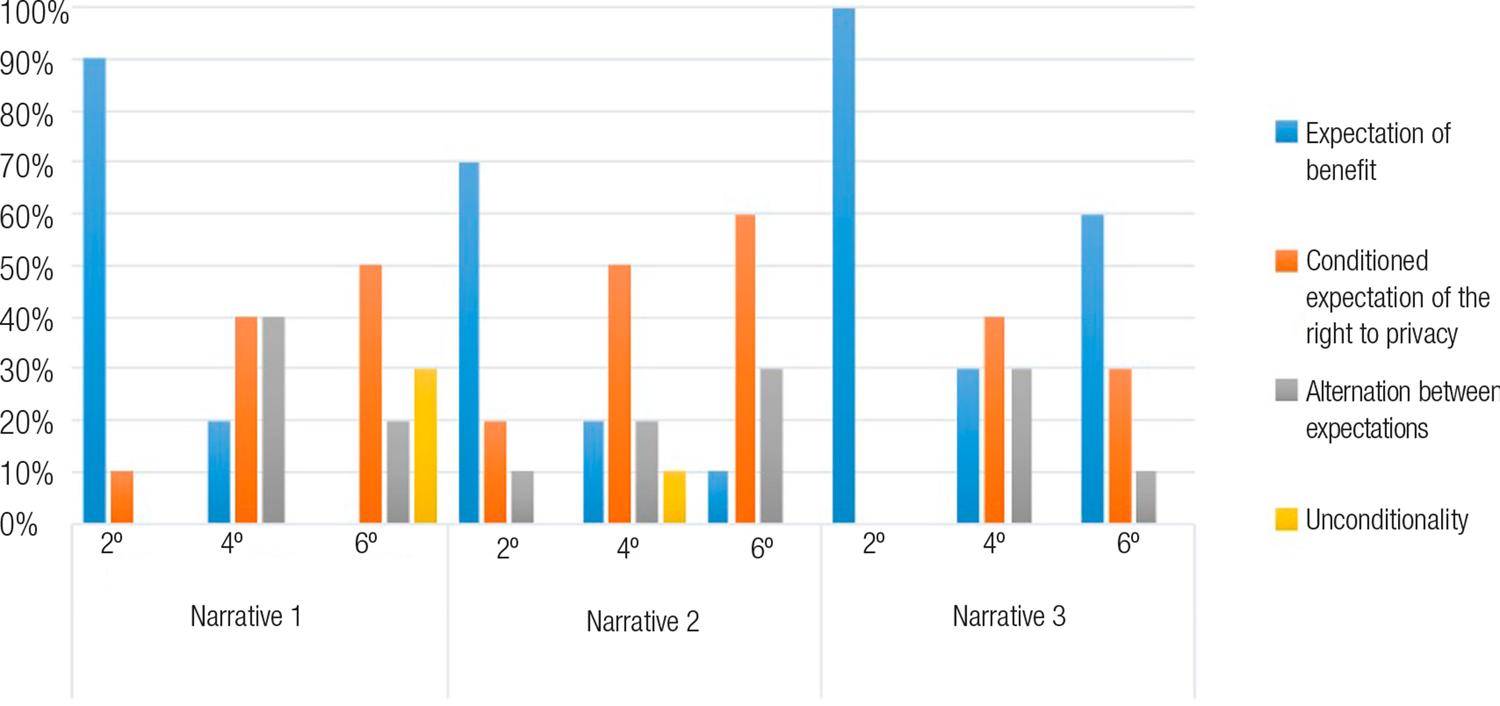

Our data provide some clues to understand the terms involved in the conceptual progression we have detailed above. The frequency of each of the groups of ideas described concerning age, by age, and by narrative will be presented in a graph:

The graph shows the distribution of categories by ages group, differentiated by the narrative. For exemple, in the group 2, Narrative 1 was explained from a benafaction expectation by 90% and only 10% from a conditioned expactation of the rigth to privacy. The same age group, in the 2nd, distributes their answers differently when faced with narrative 2, where 70% explain it from a benefaction expectation.

Source: elaborated by the author.

Graphic 1 Category distribution differentiating narratives and subject’s grade

First of all, there is no strict dependence on age, rather a conceptual development. Failure to recognize an expectation of respect for privacy is grouped in younger subjects. Recognition of this expectation of respect for privacy is distributed throughout the age range. This brings us back to a dialogue with the works of La Taille, Bedoia, and Giménez (1991) and La Taille (1998). Their studies refer to a strong correspondence between conceptual considerations and age. Our results question that statement.

Secondly, the construction of an unconditioned notion does not imply a general change in the considerations of children, but rather its partial recognition. Children who identified an unconditionality of the right did so in only one of the situations or narratives raised, not in all of them. This conceptual elaboration, far from being a final arrival point of childhood thinking, is tied to a variety of situations the subject must consider.

Our results bring us to think of an alternative version of cognitive progression in social notions to those behind other research studies we have commented on -La Taille, Bedoia y Giménez (1991) and La Taille (1998; BATAGLIA; FERREIRA; SALADINI, 2020)-, where progression was exclusively dependent on individual intellectual activity. The existence of less and more objective ideas is recognized. The latter is not something reached by all subjects or reached at the same age. Emilia Ferreiro is more than eloquent on this matter:

You do not get to concrete operations like you get to be six years old or to sit on a first-year bench. You arrive after multiple conflicts, partial compensations, failed attempts to solve problems. You do not arrive through a miraculous maturity process that would calmly take you from one stage to the next. (1999, p. 9).

We can contribute that regardless of the intellectual effort a boy or girl makes, not all subjects reach the most advanced conceptualizations as this is not merely an intellectual issue. Reaching the most objective ideas about privacy rights does not necessarily mean the subject will consider every situation from this perspective. One single subject can hold less objective versions of the right to privacy in another situation.

Which possible hypotheses can explain these particularities of children’s thinking? To interpret these results, we elaborated some provisional hypotheses that invite us to continue investigating and sustain them with greater validity. The evidence seems to show that children’s constructions concerning their right to privacy may not necessarily lead to unconditionality, something rarely recognized. From our perspective, the fact that children consider this right to be limited by the teacher’s beneficial actions may be an expression of a school situation that is conditioning their conceptual development.

This should not be thought of as if conceptual elaboration and social conditions or practices were external and limited to favoring or promoting thinking; one might rather speak of school practices as the constitutive conditions of conceptual elaboration. We differ in this respect from the perspective of La Taille (1995, 1996, 1998), where development was explained by an intellectual activity that pushed children towards more objective ideas about the right to privacy.

The presented study suggests that knowledge construction occurs in social practices and is within them that the subject cutouts his/her right to privacy. Among what we call social practices, we include direct institutional actions that restrict personal space, such as sanctions, surveillance, and asymmetries between children and teachers. Besides, a set of school rules that go beyond purely disciplinary actions, such as respect for the greater good over individual aspects, or the beneficent characteristics of institutional agents. The historical development that produced a personal and private space should also be considered, for without this, children’s elaborations on privacy and their rights would be unthinkable. In this manner, restrictions to knowledge arise with the complex institutional interactions involving power relations and rule interplay in a single institutional totality and imply a history of notion formation.

We are not the first to notice the ideas of children are usually subject to a kind of beneficial expectation, as pointed out, for example, by Barreiro (2012, 2018), Castorina, Lenzi, and Fernández (2000), Aisenberg and Kohen (2000), Lenzi and other authors (2005), who studied political ideas.

If at the same time, in the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1989), recognition of rights includes caring for people integrity (care for their food, decent housing, child abuse prevention) and the promotion of certain child citizenship, from the child’s perspective, what seems to regulate the right in schools are rights like the first ones. In other words, the child recognizes very early on that the school must protect him/her and not mistreat him/her, to the extent that the avoidance of personal harm, such as sadness caused by a private event, has more weight in children’s justifications than respect for privacy. These childhood considerations are preponderant and often imply the unawareness of an expectation of respect for privacy.

Conclusion

Throughout the article, we were able to suggest that boys and girls have different ideas and that some of them show a clearer recognition of an expectation of respect for privacy. This appears to support the idea that one can speak of the intellectual development of the notion. However, our findings also showed that some subjects failed to reach what we considered to be more advanced or objective levels of the notion, while the few who did, were unable to sustain it throughout all the situations that arose. This proposes that although children’s conceptions are progressing, this progress implies the reconstruction of social notions as they appear in collective life rather than being an abstraction of the notion as a content external to social practices. This suggests their construction of ideas is produced based on social experience. In the elaboration of social notions, we might argue we are witnessing a case of knowledge production involving the consideration of boys’ and girls’ social activity as they develop their ideas.

The latter implies a particular epistemic relationship between this type of object of knowledge and the constructive activity of an individual. Piaget (1971) conceived the epistemic relationship as a dialectic relationship between subject and object. The subject’s relationship with the objects of social knowledge possesses particularities that can be inferred from this study’s results. First of all, to be recognized by the subject, these objects of knowledge should have been socially and historically constructed. Secondly, as a social object, the subject cutouts it from the same social practices outlining it. In other words, if we find that the right to privacy is conditioned for most children, it is because the social practices where they know this right are little recognized or are subjected to institutional control. This suggests that boys and girls would not be able to develop ideas about their right to privacy if the western world had not historically developed a personal or private space. That is to say, the historical construction of that space is the starting point for law theory to declare a right to privacy for boys and girls. At the same time, such a right within school life assumes specific characteristics different from those expressed in the International Convention on the Rights of the Child. Boys and girls learn about their rights through social life. Thus, their ideas reflect the characteristics of the right at school, and not what ought to be from the legal viewpoint. In this way, one can speak of a radical dialectic between individual and society in social knowledge construction, where each cognitive breakthrough entails an unsplit relationship with the social practices where knowledge is produced.

Finally, we should stress our findings strongly suggest that school practices have effects on children’s cognitive elaborations regarding their right to privacy. This leads to the assumption that involvement in child rights-friendly school practices is likely to promote further considerations of their rights. This emphasizes the potential of schools as public institutions to politically educate students as citizens. This can generate situations regulated by the recognition of childhood rights that enable boys and girls to think about their rights, recognize them, and demand they be respected.

REFERENCES

AISENBERG, Beatriz; KOHEN, Raquel. Las hipótesis presidencialistas infantiles en la asimilación de contenidos escolares sobre el gobierno nacional. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio; LENZI, Alicia (comp.). La formación de los conocimientos sociales en los niños. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2000. p. 181-200. [ Links ]

ALTMAN, Irwin. Privacy as an interpersonal boundary process. In: VON CRANACH, Mario et al. (ed.). Human ethology: claims and limits as a new discipline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979. p. 95-132. [ Links ]

BARREIRO, Alicia. El desarrollo de las justificaciones del castigo: ¿conceptualización individual o apropiación de conocimientos colectivos? Estudios de Psicología, Madrid, v. 33, n. 1, p. 67-77, 2012. [ Links ]

BARREIRO, Alicia. El proceso de ontogénesis de las representaciones sociales de la justicia en niños y adolescentes. In: BARREIRO, Alicia (comp.). Representaciones sociales, prejuicio y relaciones con los otros: la construcción del conocimiento social y moral. Buenos Aires: Unipe, 2018. p. 129-154. [ Links ]

BATAGLIA, Patrícia U. R.; FERREIRA, Rafael R.; SALADINI, Ana Claudia. Entrevista prof. Dr. Yves de la Taille. Schème, Marília, v. 12, n. 1, p. 232-252, 2020. Disponible en: http://revistas.marilia.unesp.br/index.php/scheme/article/view/10754. Acceso en: mayo 2020. [ Links ]

BATALLÁN, Graciela; VARAS, Rene. Regalones, maldadosos, hiperkinéticos: la educación de niños y niñas de 4 años que viven en pobreza urbana. Santiago de Chile: LOM, 2002. [ Links ]

CASTORINA, José Antonio. Psicología genética y psicología social: ¿dos caras de una misma disciplina o dos programas de investigaciones compatibles? In: BARREIRO, Alicia (comp.). Representaciones sociales, prejuicio y relaciones con los otros: la construcción del conocimiento social y moral. Buenos Aires: Unipe, 2018. p. 33-54. [ Links ]

CASTORINA, José Antonio; FAIGENBAUM, Gustavo. Restricciones y conocimiento de dominio: hacia una diversidad de enfoques. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio; LENZI, Alicia (comp.). La formación de los conocimientos sociales en los niños: investigaciones psicológicas y perspectivas educativas. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2000. p. 155-177. [ Links ]

CASTORINA, José, Antonio; LENZI, Alicia; FERNÁNDEZ, Alicia. Algunas reflexiones sobre una investigación psicogenética en conocimientos sociales: la noción de autoridad escolar. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio; LENZI, Alicia (comp.) La formación de los conocimientos sociales en los niños. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2000. p. 41-58. [ Links ]

CASTORINA, José, Antonio; LENZI, Alicia; FERNÁNDEZ, Susana. Alcances del método de exploración crítica en psicología genética. In: CASTORINA, José, Antonio et al. (ed.). Psicología genética. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 1984. p. 83-118. [ Links ]

CHAPMAN, Michael. Contextualidad y direccionalidad del desarrollo cognitivo. Human Development, California, v. 31, p. 92-106, 1998. [ Links ]

DELVAL, Juan. Descubrir el pensamiento de los niños. Introducción a la práctica del método clínico. Barcelona: Paidós, 2001. [ Links ]

DUVEEN, Gerard; GILLIAN, Carol. On interviews: a conversation with Carol Gilligian. In: JOVCHELOVITCH; Sandrea; WAGONER, Brady (ed.). Development as social process. London: Routledge, 2013. p. 124-132. [ Links ]

FERREYRA, Julián; HORN, Axel; CASTORINA, José Antonio. Las ideas infantiles sobre el derecho a la intimidad: sus particularidades desde el medio virtual. Revista Investigaciones en Psicología, Buenos Aires, v. 17, n. 3, p. 25-43, 2012. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, Emilia. Vigencia de Jean Piaget. México, DC: Siglo XXI, 1999. [ Links ]

HELMAN, Mariela. Los derechos en el contexto escolar: relaciones entre ideas infantiles y prácticas educativas. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio (coord.). Desarrollo del conocimiento social: prácticas, discursos y teoría. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2010. p. 215-235. [ Links ]

HELMAN, Mariela; CASTORINA, José Antonio. La institución escolar y las ideas de los niños sobre sus derechos. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio (ed.). Cultura y conocimientos sociales: desafíos a la psicología del desarrollo. Buenos Aires: Aiqué, 2007. p 219-242. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ SAMPIERI, Roberto; FERNÁNDEZ CALLADO, Carlos; BAPTISTA LUCIO, Pilar. Metodología de la Investigación. México, DC: MacGraw-Hill, 1991. [ Links ]

HIRSCHFEL, Lawrence. ¿La adquisición de categorías sociales se basa en una competencia dominio-específica o en transferencias de conocimientos? In: HIRSCHFEL, Lawrence; GELMAN, Susan (ed.). Cartografía de la mente: la especificidad de dominio en la cognición y en la cultura: orígenes, procesos y conceptos. v. 1. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2002. p. 285-328. [ Links ]

HORN, Axel; CASTORINA, José Antonio. Las ideas infantiles sobre la privacidad: una construcción conceptual en contextos institucionales. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio (coord.). Desarrollo del conocimiento social: prácticas, discursos y teoría. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2010. p. 191-214. [ Links ]

KARMILOF-SMITH, Annette. Más allá de la modularidad de la mente. Madrid: Alianza, 1994. [ Links ]

KOHEN, Raquel. La construcción infantil de la realidad jurídica. 2003. Tesis (Doctorado) – Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, 2003. [ Links ]

LA TAILLE, Yves de. A gênese da noção de segredo na criança. Psicología, Brasilia, DF, v. 12, n. 3, p. 245-251, 1996. [ Links ]

LA TAILLE, Yves de. La genèse de la conception du droit au secret chez l’enfant. Enfance, Montpellier, v. 48, n. 4, p. 443-450, 1995. [ Links ]

LA TAILLE, Yves de. Limites: três dimensões educacionais. São Paulo: Ática, 1998. [ Links ]

LA TAILLE, Yves de; BEDOIA, Graziela; GIMENEZ, Patricia. A construção da fronteira moral da intimidade: o lugar da confissão na hierarquia de valores morais em sujeitos de 6 a 14 años. Psicologia, Brasilia, DF, v. 7, n. 2, p. 91-110, 1991. [ Links ]

LE GAL, Jean. Los derechos del niño en la escuela: una educación para la ciudadanía. Barcelona: Graó, 2005. [ Links ]

LEE, Nick. Vozes das crianças, tomada de decisão e mudança. In: MÜLLER, Fernanda (org.). Infância em perspectiva: políticas, pesquisas e instituições. São Paulo: Cortez, 2010. p. 42-64. [ Links ]

LEIRAS, Marcelo. Los derechos del niño en la escuela. Buenos Aires: UNESCO, 1994. [ Links ]

LENZI, Alicia et al. La construcción de conocimientos políticos en niños y adolescentes. Un desafío para la educación ciudadana. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio (coord.). Construcción conceptual y representaciones sociales: el conocimiento de la sociedad. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2005. p. 71-97. [ Links ]

ONU - Organización de la Naciones Unidas. Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño. [S. l.]: ONU, 1989. Asamblea general. [ Links ]

PIAGET, Jean. El criterio moral en el niño. Barcelona: Fontanella, [1932] 1971. [ Links ]

PIAGET, Jean. La representación del mundo en el niño. Madrid: Morata, 1973. [ Links ]

PIAGET, Jean. Psicología y epistemología. Barcelona: Ariel, 1971. [ Links ]

ROSEMBERG, Fúlvia; MARIANO, Carmen Lucia. A Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos da Criança: debates e tensões. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 40, n. 141, p. 693-728, dez. 2010. [ Links ]

TURIEL, Elliot. El desarrollo del conocimiento social. Moralidad y convención. Madrid: Debate, 1984. [ Links ]

4- The numbers correspond to the subjects’ age. First number corresponds to years and second number to months. In the indicated case it is 7 years and 6 months.

1- The article is part of the Research Project UBACYT 2018-2021 20020170100222BA: Restricciones a los procesos de construcción conceptual en el dominio de conocimiento social: posibilidades y obstáculos para el programa de investigación constructivista. Director: Dr. José Antonio Castorina; Co-director: Dr. Alicia Barreiro. Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Received: May 08, 2020; Revised: July 21, 2020; Accepted: September 29, 2020

texto em

texto em