Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.47 São Paulo 2021 Epub 19-Nov-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202147244510

THEME SECTION: Justice and Education: a necessary debate

Human rights education in the curricula of undergraduate courses at federal higher education institutions *

1 - Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA). Salvador, Bahia – Brasil . Contacts: daiane@ufba.br; caputo@ufba.br; renata.veras@ufba.br

The Brazilian law provides for the need of human rights education in both basic and higher education. To this end, it is necessary to include it in basic teacher training, since these professionals are responsible for developing and implementing actions and programs of formal and non-formal education at different levels. In view of this fact, this study aims to analyze the curricula of undergraduate courses offered by federal higher education institutions in order to identify how Human Rights Education plays its role in these curricula according to Resolution n. 01/2012 of the National Board of Education (CNE). This is a descriptive-evaluative documental study which analyzed syllabi of the 38 top-rank undergraduate curricula in 21 federal higher education institutions according to the Preliminary Course Evaluation framework of 2017. It included 11 areas: Mathematics, Physics, Computer Science and Chemistry, Biological Sciences, Physical Education, Philosophy and Pedagogy, Languages, Visual Arts and Music. The analysis conducted showed that the institutions are not neglectful in this regard, considering that 36 curricula examined address Human Rights and can be found in at least one course of each area. However, only 21% of the curricula of the fields investigated offer a specific mandatory course in the area, contrary to what is determined by the CNE. Thus, conclusion is that Human Rights related themes should not be restricted to a single course or treated in an isolate manner, but included in a wider array of undergraduate courses in order to make curriculum more interdisciplinary and inclusive.

Key words: Human rights; Fair school; Curricula; Undergraduate courses; Basic teacher education; University

A legislação brasileira contempla a necessidade da inclusão da Educação em direitos humanos na educação básica e superior. Para tanto, faz-se necessário que ela esteja presente na formação de professores, pois estes profissionais são responsáveis por desenvolver e implementar ações e programas de educação formal e não formal em todos os níveis de ensino. O objetivo deste estudo é analisar os currículos dos cursos de licenciatura ofertados por instituições federais de ensino superior, para identificar como a Educação em direitos humanos está inserida nesses currículos, tendo por referência a Resolução n. 01/2012 do Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE). Trata-se de uma pesquisa descritiva-avaliativa, do tipo documental, que incidiu sobre as ementas de 38 currículos de licenciaturas com melhor avaliação no Conceito Preliminar de Cursos 2017, distribuídos em 21 instituições federais de educação e relacionados a 11 áreas: Matemática, Física, Computação e Química, Ciências Biológicas, Educação Física, Filosofia e Pedagogia, Letras, Artes Visuais e Música. Como resultado, foi possível identificar que as instituições não são omissas, considerando que 36 currículos abordam direitos humanos com conteúdos distribuídos em uma ou mais disciplinas, porém apenas 21% dos cursos ofertam componente curricular obrigatório específico para o tema, contrariando o que determina o CNE. Conclui-se que é preciso ampliar a inserção da educação em direitos humanos nas licenciaturas e que não se restrinja apenas a uma disciplina ou conteúdos isolados, mas que seja uma formação transversalizada em todo o currículo.

Palavras-Chave: Direitos humanos; Escola justa; Currículos; Licenciaturas; Formação inicial docente; Universidade

Introduction

Basic teacher training in Human Rights has reached the status of public policy since the publication of the National Curricular Guidelines for Human Rights Education (BRASIL, 2012a). This law is a consequence of the actions predicted in international agreements in order to promote Human Rights that Brazil has signed in recent decades (ONU, 1948a, 1948b, 1993, 1994, 1997, 2011; UNESCO, 2006, 2012, 2015). The inclusion of training courses in the curricula for basic education professionals is one of these actions to be implemented by training institutions.

Currently, teacher development for basic education is obtained through an undergraduate degree in Brazil. Undergraduate degrees are offered at public and private higher education institutions, duly accredited by the Ministry of Education. The curricula for these courses are established under the autonomy and responsibility of the institutions, provided that they comply with the educational laws in force.

The curriculum, understood in this study as a socio-educational artifact 2 (GOODSON, 2007), is constituted by means of a myriad of social, political, cultural, ethical, aesthetic implications, which encompass the cultural institutions of education 3 . These implications are not always explicit; they are not always coherent or absolute, within the contradictions, dilemmas and transgressions (MACEDO, 2017). For Sacristán (2013), the curriculum is not something neutral, universal and unchangeable, but a controversial and conflicting territory, the result of traditions that can and should be reviewed and modified.

In view of this fact, the act of becoming a teacher is a complex process, since it is deeply associated with the official curriculum goals, educational legislations as well as the experiences of the different social realities found in the school setting. Therefore, it is necessary to think of the undergraduate’s path as a progressive process of acquiring a professional dimension (NÓVOA, 2019). In this sense, as basic teachers education, it is crucial that they learn concepts and pedagogical strategies in order to be able to deal with social issues that impact daily life in and out of the classroom, such as those arising from human rights violations. It is essential that Human Rights Education be present in the teachers’ training, especially because they will share such knowledge eventually.

This study is part of a Master’s research and aims to analyze the curricula of the most highly ranked basic teacher training courses offered by Higher Education Federal Institutions in order to identify how Human Rights Education is inserted in these curricula, with reference to Resolution No. 01/2012 of the National board of Education (CNE).

Public policies and their implications for the training of educators in human rights

Brazil is by constitutional definition a Democratic State of Law. It is in the Federal Constitution that Brazil assumes as its duty the protection and guarantee of Rights, based on a fair, fraternal, pluralistic, unbiased, peaceful, and equal society, whether individual and/or social, in order to improve social welfare (BRASIL, 1988).

Consequently, awareness about these rights is essential in order to guarantee its protection; education is the means whereby such awareness become possible (NOLETO, 2018). According to Boaventura (1996), education is a subjective, social and universal public right, other than being a state and family duty. it is compulsory for the individual, it is charges and material and legislative powers for the state, duties of assistance and solidarity for the family. However, education is, above all, a collective right, considering that it connects with life in society, with political engagement, with national development, with the promotion of human rights and peace; it connects with the person «inserted in a given social and political context,» which means to dissociate the right to education be from the right to democracy (RANIERI, 2013, p. 78). It is also related to ethical and ecosystem determinants in order to restructure a society in which human beings coexist among themselves and with nature (GUDYNAS; ACOSTA, 2011).

As it is a right for all, it dynamizes and conjugates commitments in relation to Human Rights Education, considering that Human Rights are an essential part of the right to education (SILVEIRA et al ., 2007),

The school has a social function in this process, as it constributes for the development of people’s thought and critical sense enabling them to intervene in collective and public matters (PARASKEVA; GANDIN; HYPOLITO, 2004). Professionals in education must, therefore, be prepared to deal with and contribute to the adversities which are inherent to the the pedagogical process. Thus, teachers need to be trained in order to become sociocultural and political agents so that they can understand and problematize social reality and promote human rights (CANDAU et al ., 2013). As reflecting on the moment that basic teacher training starts, Candau et al . (2013) assert that teacher training begins long before they start higher education courses. This happens because undergraduate students, when they arrive at the University, have at least 11 years of schooling whereby they have experienced several kinds of traning, generally homogeneous and centered on traditional educational models. This is because homogeneity and the search for equality without considering the differences was believed to be the criterion for ensuring learning at the school setting for a long time (TRAVERSINI, 2013). For this reason, Candau et al. (2013) state that in policies promoting Human Rights in Education it is essential to overcome the emphasis on equality that denies people’s uniqueness and differences for a dialectical relationship, in which equality is not opposed to difference, but to inequality. In this perspectictive, fighting for equality means fighting to recognize each individual’s right, being the recognition of the difference for the construction of equality with social justice an essential element.

In the Brazilian context, educational policies have been implemented according to the interests of the State (GIROUX, 1997), which has, consequently, privileged the elite over the less favored population and deepened social inequalities. According to Ball (2002), in addition to providing technical and structural changes in organizations, policies aimed at reforming education have also focused on mechanisms to «reform» teachers, i.e., by changing not only what the teacher does, but also what they are, (re)shaping their identity and what it means to be a teacher. Macedo (2014, p. 1549) points out that, «the construction of a new architecture of regulation is underway,» in which «the hegemonized meanings for quality education are related to the possibility of controlling what will be taught and learned» (MACEDO, 2014, p. 1549). Among these control alternatives is the performative discourse that broadly attempts to disqualify the University and basic teacher training by labeling them as unqualified and poorly trained (MACEDO, 2014).

On the other hand, Apple (2017) points out that strong democratic policies and practices still survive in many spaces because of the hard, continuous work and sacrifices made by teachers, community members, and social movements. The significant advances regarding Brazilian education were achieved through the efforts of these professionals and representatives of movements on behalf of the working class. Therefore, when refering to teacher education, it is important to consider the political forces in the national educational scenario which are not only strongly influenced by the neoliberalist global geopolitics, but also the result of counter-hegemonic struggles waged by those who do not accept the injustices arising from these forces of oppression (SANTOS, 2011).

The debates about the social demands that are concerned with teacher training linked to international political demands played a key role in the the creation of specific governmental measures in Brazil (SILVA; TAVARES, 2013). However, it was only after 2001 that the CNE devised the national curricular guidelines to regulate undergraduate courses for teacher education for the first time (BRASIL, 2020). Among these guidelines, it is worth highlighting those that gave greater emphasis to the knowledge concerning Human Rights as part of the undergraduates’ training: Resolution n. 01/2012 of CNE that established the National Curricular Guidelines for Human Rights Education; the Resolutions of CNE n. 01/2015 and n. 02/2015 that established the National Curricular Guidelines for the training of teaching professionals for basic education and, respectively, the training of indigenous teachers. The last two were given birth after the proposals set forth in the National Education Plan, Law n. 13.005/2014 (DOURADO, 2015; BRASIL, 2014), which are considered milestones of a more progressive stage of policies aimed at fostering teaching qualification. All of them comply with the requirement of Human Rights Education for the training of education professionals.

However, there have been significant political changes that have impacted the Brazilian educational system in recent years with particular emphasis on basic teacher traning for which «[...] a new configuration of power within the Ministry of Education (MEC) was designed with the consequent change in the joint forces of the CNE through the annulment of the ordinance of reappointment and appointment of new councilors» (AGUIAR, 2018, p. 8).

From then on, some political measures were adopted even by going against several representatives of civil society and educational institutions, such as the annulment of Resolution n. 02/2015 of CNE and the approval of the National Common Base (BNC) for teacher education (ANPED, 2019) as a replacing measure. This Base in comparison with the annuled Guidelines brought about setbacks for training, such as the emphasis on disciplinarity and training focused on the development of competences. Although it mentions Human Rights as content, it does not make explicit the conception of Human Rights which was drawn upon, nor does it indicate its implications for teaching profession training. Besides, it neglects themes dealing with human rights, such as diversity of gender, sexual, religious, generational group understanding and respect as well as the learning of the Brazilian Sign Language (Libras).

In view of such governmental actions, it can be observed that today the discredit of the teaching profession still prevails, aligned to a state-centered training, i.e., focused on the interests of the State (LOPES; MACEDO, 2011), which favors the maintenance of oppression and the denial of quality training in education, given its historical disregard for public education and disrespect for the debates and contributions of the representatives of the most diverse social sectors protest for quality education (ANPED, 2019).

Methodology

This is an exploratory and descriptive-evaluative qualitative study of documentary nature. This study focused more specifically on the most highly ranked undergraduate course (LEVEL 5), according to the Courses Preliminary Evaluation (CPC) 2017, offered at Federal Institutions of Higher Education (IFES). The CPC data were obtained on the MEC website, which are maintained for public access and categorized in a spreadsheet. The documents were available on the IFES’s institutional websites. The authors chose to resort to CPC because it is a framework used by MEC as a quality indicator of undergraduate courses. The courses are ranked based on the students’ grades in the National Examination of Student Performance (ENADE), the value added by the educational process offered by the course, the training and work regime of the faculty members as well as the students’ perception of the context of the educational process (BRASIL, 2018).

Research context

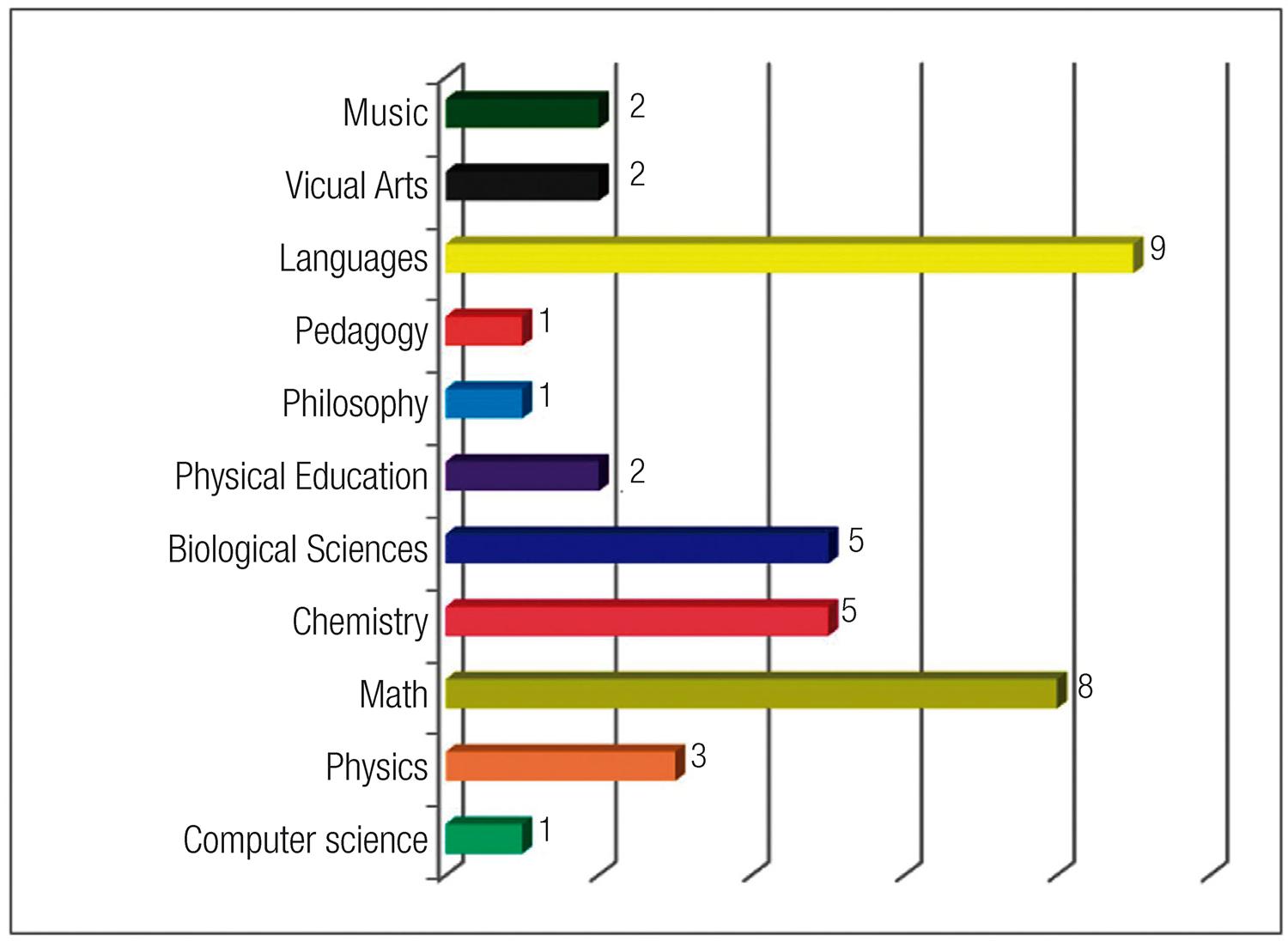

The 39 undergraduate degrees that were most highly ranked (Level 5) according to CPC 2017 are found in 21 IFES, 19 universities and 2 institutes. The quantitative representation by field of knowledge is shown in Figure 1 below:

Source: Designed by the authors (2020).

Figure 1 – Number of undergraduate degrees analyzed by field of knowledge

17 of these courses are related to Exact Sciences (Mathematics, Physics, Computer science and Chemistry), 05 to Biological Sciences, 04 to Humanities (Physical Education, Philosophy, and Pedagogy), 9 to Languages (Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, and English), and 4 to Arts (Visual Arts and Music).

Procedures

The research data come from official documents of open access available at the IFES: pedagogical projects and/or the respective syllabi of the undergraduate curricula. As for the document analysis procedure, for the data codification and categorization, some systematic steps taken (RICHARDSON, 2012), as follows: (1) preliminary analysis and categorization of the documents; (2) Document screening and the systematization of the data and organization into predefined categories; (3) results treatment of the previous steps by means of inductive and deductive interpretations (CELLARD, 2008). The pre-established category and subcategories were:

a. main category: curricula of undergraduate degrees offered at IFES ranked at level 5 according to CPC 2017;

After screening 39 courses’ pedagogical projects of the courses and/or their respective syllabi, it was possible to have access to the syllabi of 38 courses, pedagogical project of 32 courses, but only 6 syllabi. Only Physical Education at the Federal University of Ceará did not provide the information needed for the research. To help analyze the course syllabi, the free software Iramuteq was used. This software performs statistical analysis of texts through data processing and is widely used in qualitative research (CAMARGO; JUSTO, 2013a).

In addition to this tool, we also underwent a careful analysis of the syllabi, identifying objective and subjective data that were not possible to obtain with the software.

The word cloud was considered the most appropriate form of analysis for this type of study, as it allowed quick identification of the most frequent keywords in the written context (CAMARGO; JUSTO, 2013b; KAMI, 2016).

To identify the contents pertinent to the themes, we followed the classical categorization of Human Rights adopted by several authors, including the concepts presented by Ramos (2017) and Oliveira and Lazari (2018), starting from the first classifications by jurist Karel Vasak and the updates in dimensions by Paulo Bonavides (RAMOS, 2017). Based on these authors and the legal norms discussed in this study, we sought to systematize the themes in the following table :

Table 1 Dimensions of Human Rights and related themes

| Dimensões | Themes related to Human Rights |

|---|---|

| 1ª | Freedom, individual, civil, and political rights: right to life, liberty, personality, access to justice, criminal human rights, nationality, political rights. |

| 2ª | equality, economic, social, and cultural rights: education, health, culture, food, clothing and housing, leisure, security, family, work, |

| 3ª | fraternity and solidarity rights: community, peace, environmental, development, self-determination, conservation of historical and cultural heritage. |

| 4ª | political globalization: to democracy, pluralism, information, bioethics, genetic manipulation. |

| Outras | love, care, compassion, tolerance, drinking water, among others. |

Source: Designed by the authors (2020) based on studies by Ramos (2017) and Oliveira and Lazari (2018).

From the table above, it was possible to relate the Human Rights themes to the contents found in the curricula, which resulted in relevant data investigate the study main objective.

Discussion and results

Discussing the curriculum implies reflecting on several key elements in education, among these, the quality, the inclusion and the relevance of certain contents and their approaches. Studies on curriculum design help to better understand the goals, the social imaginary and the aspirations that are sought to achieve in an effective education system (OPERTTI; KANG; MAGNI, 2018). Similarly, such studies show that the curriculum is designed by choices of the knowledge that educational professionals consider relevant to the detriment of those they elect as irrelevant (SILVA, 2017). They also reveal that educational rules have a strong impact on curriculum design, considering they bring state impositions to this field (LOPES, 2006).

Therefore, it is believed that the institutions investigated that elected Human Rights Education as relevant content for the basic teacher training courses are positioning themselves politically. It is understood that such curricular tendency can contribute to fostering engaging citizens, socially committed and, consequently, capable of promoting continuous debates around the theme at work and everyday life. In this sense, it is considered necessary to initially present the mapping of the most highly ranked courses and, subsequently, how they insert the Human Rights theme in their curricula.

Mapping out the most highly undergraduate courses according to CPC 2017

The results demonstrated that 5,088 undergraduate courses were evaluated through the CPC 2017 conducted by MEC’s Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP). 4,652 out of these courses are in the offereced face-to-face, which corresponds to about 91% of the evaluated courses. Among the face-to-face courses, 2,317 (45.54%) are offered by Public Higher Education Institutions, with 1,298 belonging to the federal administrative category. Of the federal institutions, 39 obtained the maximum score, as shown in the chart below:

Table 2 Undergraduate courses by IFES socoring 5 according to CPC 2017

| Area | Undergraduate course | IFES | IFES acronym | City |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Computer Science | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Palotina |

| Physics | UF de Viçosa | UFV | Florestal | |

| UF de Juiz de Fora | UFJF | Juiz de Fora | ||

| UF de Santa Maria | UFSM | Santa Maria | ||

| Mathematic | UF de Ouro Preto | UFOP | Ouro Preto | |

| UF de Viçosa | UFV | Florestal | ||

| UF de Santa Maria | UFSM | Santa Maria | ||

| UF de Santa Catarina | UFSC | Blumenau | ||

| UF de Alfenas | UNIFAL-MG | Alfenas | ||

| IFECT 1 do Rio Grande do Sul | IFRS | Canoas | ||

| FUF 2 do Abc | UFABC | Santo André | ||

| UF da Fronteira Sul | UFFS | Chapecó | ||

| Chemistry | UF de Juiz de Fora | UFJF | Juiz de Fora | |

| UF do Rio Grande do Sul | UFRGS | Porto Alegre | ||

| UF de Santa Catarina | UFSC | Blumenau | ||

| IF de São Paulo | IFSP | Sertãozinho | ||

| FUF do Abc | UFABC | Santo André | ||

| II | Biological Sciences | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Palotina |

| UF de Goiás | UFG | Jataí | ||

| UTF 3 do Paraná | UTFPR | Santa Helena | ||

| IFECT de São Paulo | IFSP | Avaré | ||

| FUF do Abc | UFABC | Santo André | ||

| III | Physical Education | UF do Ceará | UFC | Fortaleza |

| UF de Lavras | UFLA | Lavras | ||

| Philosophy | UF de Santa Maria | UFSM | Santa Maria | |

| Education | UII 4 da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira | UNILAB | Redenção | |

| IV | Portuguese | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Curitiba |

| Portuguese/Italian | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Curitiba | |

| Portuguese/English | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Curitiba | |

| UF do Ceará | UFC | Fortaleza | ||

| FUF do Pampa | UNIPAMPA | Bagé | ||

| Portuguese/Spanish | UF 5 dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri | UFVJM | Diamantina | |

| UF da Fronteira Sul | UFFS | Realeza | ||

| English | UF do Paraná | UFPR | Curitiba | |

| UF de Santa Catarina | UFSC | Florianópolis | ||

| V | Visual arts | Universidade de Brasília | UNB | Brasília |

| UF de Juiz de Fora | UFJF | Juiz de Fora | ||

| Music | UF de Uberlândia | UFU | Uberlândia | |

| UF de Santa Maria | UFSM | Santa Maria |

Source: Designed by the authors (2020).

Table caption

1- IFECT = Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia (Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology).

2- FUF = Fundação Universidade Federal (Federal University Foundation).

3- UTF = Universidade Tecnológica Federal (Federal Technological University).

4- UII = Universidade da Integração Internacional (University of International Integration).

5-UF = Universidade Federal (Federal University).

According to Bittencourt et al . (2010), the CPC scores show the predominance of higher ranked courses offered by public universities compared to private institutions. A greater number of professors possessing a Ph.D. degree, working either part-time or full-time, and a better student performance in ENADE are two relevant factors showecased by public universities.

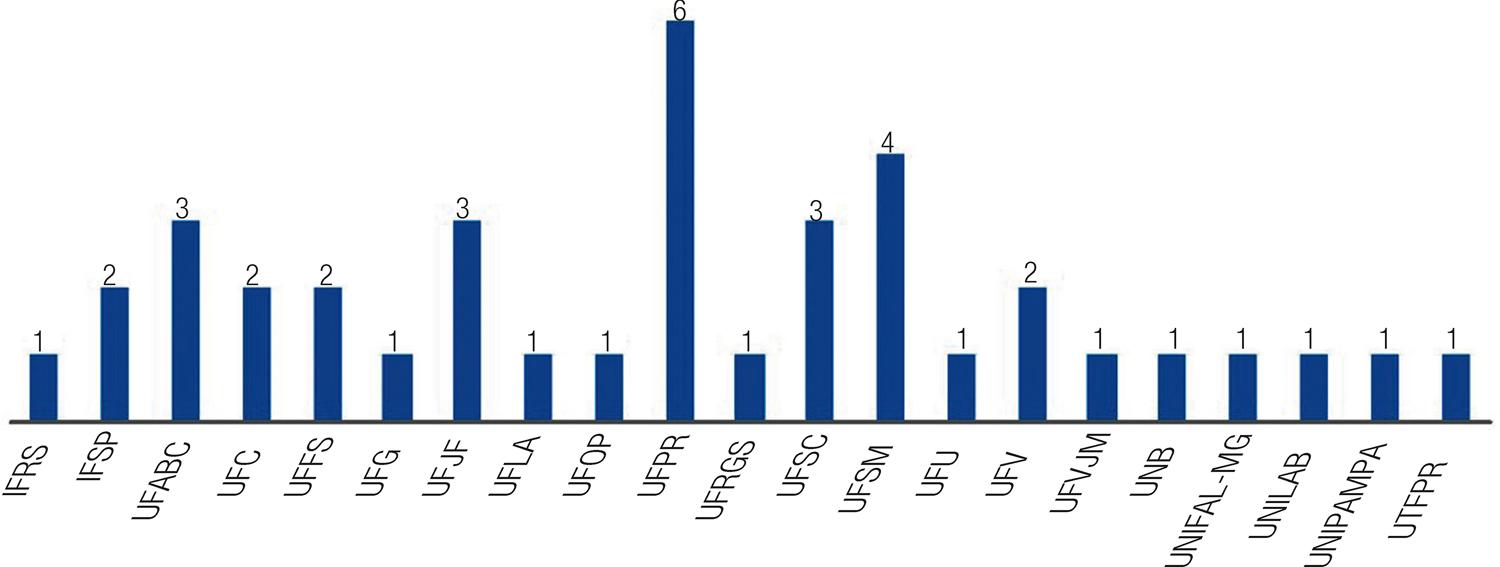

The IFES with the highest number of undergraduate courses given the highest score are offered at the Federal Universities of Paraná (6), Santa Maria (4), Santa Catarina (3), Juiz de Fora (3) and ABC (3). Figure 2 shows the number of courses per IFES:

Source: Designed by the authors (2020).

Figure 2 Undergraduate degrees with ranked 5 (CPC) in each IFES

It was also noted that there is a predominance of Area I courses (Exact Sciences), followed by Area IV (Languages). However, in order to better understand this result, it is important to consider numerous factors, including the context of insertion of the courses, observing the socioeconomic and regional indicators, course academic and institutional management, aligned with the evaluation criteria, administrative category, academic organization (BRASIL, 2015), among other factors. These could more more thoroughly investidated in a different study.

Human rights education in the most highly ranked undergraduate courses in CPC 2017

There are two important criteria to be considered in the analysis of undergraduate curricula: the first one refers to the possibilities Education in Human Rights content insertion in curriculm design of Basic Education and Higher Education according to Resolution n. 01/2012 of the CNE, which can be done as follows: by transversality and treated interdisciplinarily; as a specific content of one of the existing courses; combining transversality and disciplinarity; other forms of inclusion (BRASIL, 2012b, p. 2, art. 7, I, II, III). As for the preservice and continuing education, Human Rights Education must be a mandatory course (BRASIL, 2012b, p. 2, art. 8).

As for the second criterion, we must consider what the scores of undergraduate courses evaluation tools managed by INEP mean, specifically, score 1.5, in the dimension of didactic-pedagogical organization, which brings as an indicator the approach of relevant content to the policies of Human Rights Education (BRASIL, 2017).

One of the outcomes of this evaluation is that courses may receive a lower score in case of non-compliance with the quality indicators. In addition to subsidizing the regulatory decisions of the MEC, this score has an impact on authorization, recognition and renewal of recognition of undergraduate courses (BRASIL, 2017). Thus, when analyzing the curricula, it was possible to identify two forms of insertion: disciplinary and multidisciplinary. The latter has predominance over the former, i.e., human rights content present in existing disciplines in the curriculum, an option adopted in most of the analyzed curricula.

The courses’ outline, as it is presented nowadays, was designed during the XIX century, with the emergence of modern universities, gaining new colors from the XX century on, with the burgeoning of scientific research (MORIN, 2003). For Morin (2003) this means that the history of disciplinarity has its roots in the University, which, consequently, is inscribed in the history of society, by establishing work division and specializatio. Over time, this curricular model has been characterized by its fragmentation and hierarchization of knowledge (GALLO, 2000). As for the multidisciplinary organization, it is an group of disciplines dealing with common themes, sometimes articulating bibliography, teaching techniques and assessment procedures, but without showing a proper interrelation and connection among them, at least in the official curriculum (ALMEIDA FILHO, 1997).

According to Candau et al . (2013), the curricular desigh in Higher Education should focus on Human Rights based on a proposal of educational and plural bias, which is present throughout the curriculum. This discipline crossing should be materialized from concomitant, intercultural, interdiscursive and interdisciplinary pedagogical practices.

For Braga, Machado, and Guimarães-Iosif (2014), Brazil still maintains a tradition of taking interdisciplinary education for granted, which, according to them, is of vital importance to add knowledge that goes beyond traditional content, and should start from the principle of citizen education, with a human, social, and political apporach. However, the interdisciplinary curriculum model is nothing more than a disciplinary model, since interdisciplinarity cannot be done without courses; the transdisciplinary curriculum is considered a more evolved proposal (GALLO, 2000).

This way, Santos (2008) says that transdisciplinarity shows another way of thinking about contemporary problems by opposing the Cartesian principles of fragmentation of knowledge and dichotomy of dualities. The proposal of transversality in university and school curricula would imply new models, which are different from what is conceived today as a formal learning space. Above all, it would house, in a much broader way and without the limitation of previous formats, the contents for an Human Rights.

However, Candau et al . (2013) point out that developing a pedagogical project of a course that constitutes a proposal for teacher training in Human Rights that is crossdisciplinary, interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary, is a complex work. Most of the time, it is conditioned to the juxtaposition of disjointed disciplines. One possibility to foster a cohesive approach on the theme in the curriculum is to gather the main contents dealing with Human Rights Education in a course, as predicted by Resolution 01/2012 of the CNE, for the start of a traning, which eventually can result in the full insertion of the theme.

Based on these references, it was found that only 21% out of the 38 curricula are in conformity with article 8 of Resolution 01/2012 of the CNE: Chemistry at IFSP and UFSC; Music at UFU; Mathematics at UFSM, UNIFAL-MG, UFFS, UFSC and IFRGS. That notwithstanding, it was possible to identify that 36 of the 38 curricula have Human Rights contents inserted in mandatory courses that address other themes.

Other forms of insertion were also observed from the reading of the pedagogical projects available and the curriculum frameworks with their respective syllabi. However, the findings do not refer to the mandatory courses, but to electives, extracurricular and research group activities, which, being non mandatory, do not allow us to identify whether or not they will undergo this training. Even so, it is understood that Human Rights Education should be included in the curriculum as a shole, as it will possibly expand the students academic horizons.

Regarding to crossdiscipline isses, it was identified that the courses curricula courses follow the disciplinary and traditional structure, without showing methodologies that denote interdisciplinarity, that is, possibilities of establishing connections between the concepts and interpretations of each discipline (JORDELET, 2016), regarding the insertion of topics related to human rights and/or human rights content that encompass the entire curriculum.

According to Gatti (2010), this curricular conception has historical roots, because the curriculum of teacher education courses is characterized by being fragmentary. Even with partial adjustments due to the new guidelines, there is a predominance of the disciplinary character of the curricula of these undergraduate courses.

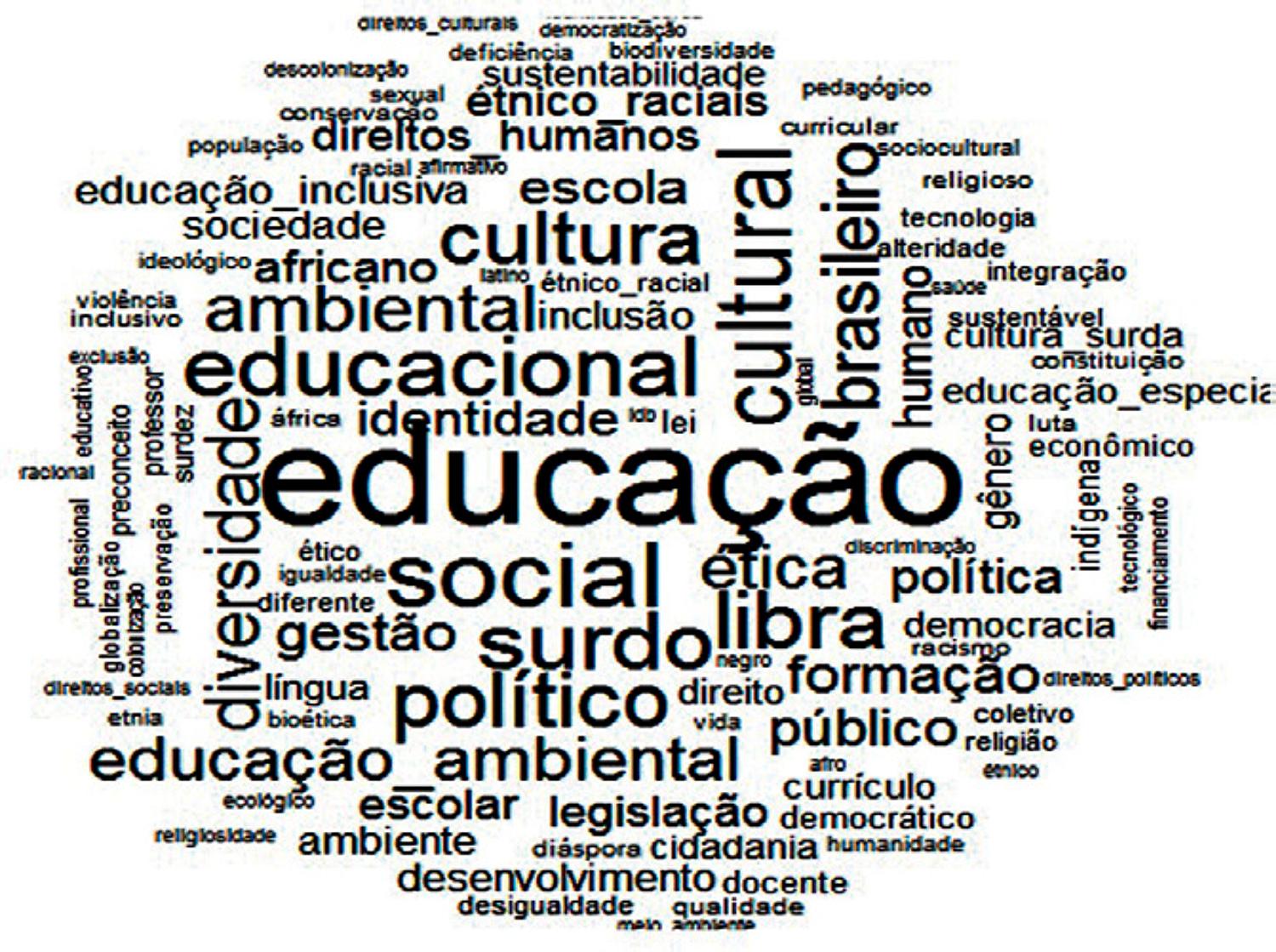

In order to identify the disciplinary insertion in specific courses in the curricular program and those contained in the existing ones, the use of Iramuteq allowed the visualization and arrangement of the most frequent terms in the text. The word cloud below illustrates the set of terms with greater evidence in the set of all curricula analyzed.

It was observed that the central axis is the term ‘Education’ (Educação), that is, the term that appears most often in the curricula. The terms libras ( Brazilian Sign Language ) / surdo (deaf), educação ambiental (environmental education), diversidade (diversity), cultura (culture), ética (ethics), direitos humanos (human rights), política (politics), étnico-racial (ethnic-racial) are considered of great relevance. Other themes, however, are less recurrent: inclusão (inclusion), gênero (gender), democratização (democratization), decolonização (decolonization), igualdade ( equality ), among others.

The similarity of the term Education related to the contents of Human Rights, through the diversified approach of themes in the curricula leads us to believe in the intentionality in designing curricula that aim at the teacher academic background fostering more engaged professionais with humanistic and politicized issue. According to Gadotti (2003), a politicized student is one who is motivated by the quality of what is taught, who demands explanations, who motivates the teacher and who is interested in the human relations established in the educational environment. As a consequence, they will be more aware of the fact that every educational practice is a political action (FREIRE, 2003) and that Educating in Human Rights is inherent to this practice.

The most recurrent themes found and of relevance to this study are the following:

Table 3 Most recurrent themes

| Themes | Themes related to the most recurring topics |

|---|---|

| Education | Environmental education, democratic management, globalization, generational, ethnical-racial, sexual, gender plurality focused on contents that approach discrimination and prejudice |

| Libras | Inclusive education, special education, deaf identity, deaf culture, citizenship |

| Culture/Cultural diversity | ethics, bioethics, african, indigenous, religion, ethnic and religious diversity, sustainable development, otherness, decolonization, among others |

| Politics | Social, politic rights and democratization |

Source: Designed by the authors (2020).

This last analysis allowed us to see a greater detailing of the most recurring themes. It was also identified that these themes are aligned with post-critical discourses on curriculum, that is, that contrast and question the emerging social and educational arrangements, challenge the status quo , including themes that discuss inequalities and social injustices in the curriculum such as, for example, otherness, difference, decolonization and plurality (SILVA, 2017). These are current contents and agendas demanded by the movements of underrepresented social groups in search of recognition and guarantees of their rights, which should not be hidden or neutral in teacher education. According to Gadotti (2003), the educator in this society cannot be neutral; either he educates in favor of the disadvantaged or against them. For this author, the school, which is the teacher’s arena, is not neutral, nor is it exempt from the influences and tensions generated by social, political, cultural, economic and ideological events.

From this perspective, it is understood that regardless the undergraduate course, it is essential that topics inherent to Human Rights Education be part of teacher traning in all areas (SILVA, et al. , 2013).

In the joint analysis of the curricula by field of knowledge, we also sought to identify the emphases, i.e., the most recurring contents in the written corpus. It was found that Visual Arts, Biological Sciences, Philosophy Pedagogy, Mathematics, Music, Literature and Physics are the undergraduate courses with denser content; those of Computer science, Physical Education and Physics are less content based. The courses of Physics at UFSM and Mathematics at UFOP are excluded from this analysis, which do not include Human Rights content in their curricula. It should be noted that the first curriculum program is dated from 2005. If it has not been updated since then, obsolescence may explain the non-compliance with the Guidelines for Human Rights Education, which was published in 2012. As for the second curriculum, it was not possible to access all the syllabi of the mandatory courses, a factor that impaired the analysis, since the IFES partially published the contents of these courses. On the other hand, UNB also makes the syllabi of few mandatory courses of the Visual Arts undergraduate course available. However, it was possible to identify the presence of Human Rights contents even in the few available ones.

Therefore, the inclusion of Human Rights Education is predicted by educational law. However, it is still optional, considering the autonomy of the IFES to meet such law, even if it is to the cost of being sanctioned by the governmental organs which evaluate and regulate Higher Education. This was the option of the actors involved in the curriculum design of the Biological Sciences undergraduate course at IFSP. Although the recognition of what determines the Resolution No. 01/2012 of the CNE is present in the pedagogical project of this course, they chose to implement a course related to the Human Rights field. Istead of maintaining it as mandatory according to art. 8 of this norm, they decided to include it among electives.

It is inferred that the emphasis given to the theme in each curriculum reflects «what» the pedagogical professional involved in the selection of the contents consider relevant for the students education. These curricular options reveal that, «the curriculum is designed according to power relations», «conveys particular social views» and «produces particular individual social identities» (MOREIRA; SILVA, 2002, p. 8). It can be an instrument of alienation and denial of certain knowledge, as well as it can be politically engaged with the social demands. It is above all a proper means for the critical and intellectual emancipation of learners, as well as for the transformation of power relations (MOREIRA; SILVA, 2002).

For Arroyo (2003), when thinking about the curriculum, one should consider the diversity of social subjects and protagonists that are part of this construction. According to this author, each area of the curriculum sees knowledge from its own angle and often tends to leave out knowledge built and accumulated by the plurality and diversity of social actors, which are not recognized because they are considered marginal to the logic of knowledge traditionally considered important for scientific knowledge and to intervene politically, for example, «the right to have rights» (ARENDT, 1989, p. 332) and recognition of indigenous knowledge and marginalized ethnic groups and recognition of autochthonous knowledge and marginalized ethnicities such as indigenous, African, gypsies, among others. Santomé (2013) states that the explicit and emphasized curricula in most institutions’ curriculum proposals call attention to the massive presence of hegemonic cultures and the silencing of the cultures and voices of understimated social groups. When they appear, they are usually misrepresented or riddled with prejudice and discrimination.

In the investigated curricula, most of the content found addresses Human Rights issues related to minority groups through the content dealing with ethnic-racial relations and related issues (prejudice, discrimination, colonization, decolonization, diaspora, African and indigenous cultures and identities) and other diversities (sexual, generational, gender). These are relevant issues in the debates on the theme, considering that these are the groups that suffer the most from rights violations.

For Santos and Martins (2019), the global hegemonic conception of human rights as a language of human dignity and universal right coexists with the realization that the majority of the world’s population is not the subject of rights, but the object of its discourses, especially those who suffer systemic oppressions imposed by capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy.

According to Candau (2002), Brazilian history is marked by the elimination of the «other» and the violent denial of otherness. Therefore, it is necessary make society and the educational and curricular practices more democratic as well as the promotion of basic rights for all. However, not limited to the rights of individuals, but thinking of a society that acts in harmony with the environment and with all beings that dwell in it. It is an understanding of Human Rights that moves away from colonialist ideals, does not marginalize non-European peoples, such as the Afro-Amerindians in Brazil, and that is also aligned with the concept of Good living Human Rights (GARCIA, 2015). The Good living is an ethic, derived from Latin American epistemologies, which should guide state actions to promote Human Rights in order to finally be able to «build another society sustained in the community, in the coexistence of human beings in diversity and in harmony with nature, from the recognition of the diverse cultural values existing in each society, in particular throughout the planet. (GARCIA, 2015. p. 254). In the examined curricula, it is inferred that there is allusion to this problematization in the contents: environmental education and sustainable development (boxes 4 and 5), environment, biodiversity, preservation, ecological ( figure 3 ). In this view, educational institutions have an important mission when they position themselves with counter-hegemonic proposals and actions and articulate the denial of the monocultural standardization present in the curricula and fight against all forms of inequality present in our society and in education.

Educating within the parameters of a Human Rights culture is demanded by both the international and national communities, with an appeal to the strengthening of democracy in societies. However, it is understood that it is a great challenge for all fields of knowledge in Higher Education (SILVA; TAVARES, 2013), especially considering the public policies that often act against the full social and educational development (APPLE, 2005). However, educational institutions can and should stop being the place «where you learn only the basics and reproduce the dominant knowledge, to assume that it needs to be a manifestation of life in all its complexity,» such as teaching «the complexity of being a citizen and the various instances in which it materializes: democratic, social, solidarity, equality, intercultural and environmental» (IMBERNÓN, 2011, p. 8). In the meantime, the training of human rights educators is, nowadays, an additional path for the construction of an education that promotes empowerment and fosters the capacities of the curricular actors in the constitution of curricula focused on this theme, being aware that «training is the initial stage, but the educational process in human rights is continuous» (TAVARES, 2007, p. 487).

Conclusion

The design of pedagogical projects of courses to train professionals in education should prepare them to perform in society with social, ethical, and human responsibility.

It is understood that curricula are structured through a selection of knowledge considered relevant by their curriculum designers, based on their multiple cosmovision, culture and experience. they are also the result of normative frameworks often imposed by the managing executive power, in an arbitrary way and without respecting the full democratic debate and the university autonomy.

The omissions and curricular options in teacher education, whether they come from the legislator and/or from the educational institutions, show what kind of curriculum it is, which professional profile is intended to form. Thus, it was found that the undergraduate courses with the highest CPC score are offered by public federal institutions and that the vast majority of these institutions are universities.

In the analyzed curriculums, it was possible to identify two forms of insertion: disciplinary, in which there is a compulsory theme-related course; and multidisciplinary, in which the several contents related to the theme are inserted in disciplines that deal with other themes. Out of the 38 curricula, only 8 meet the requirements of article 8 of Resolution 01/2012 of the CNE. In other words, they have a mandatory course. However, the multidisciplinary form is predominant in 36 of the 38 curricula analyzed. It was also identified that 16 of these curricula were updated prior to the publication of Resolution 01/2012 of the CNE. Out of these, 15 have human rights content, even when the resolution did not exist. These curricula also address the theme beyond the compulsory requirement, with offers in electives, extracurricular courses and research group activies, among other non-mandatory academic events. However, the study did not stick to these features, since the objective is to investigate only the curricular options that denote the compulsory training on the human rights theme, since the other options are not possible to evaluate because they depend on the course offer and the students’ choices. Another pertinent observation is that all the curricula obtained the maximum score in the CPC. This result may mean that INEP only evaluates if the courses contain contents on the theme, because the evaluation instrument does not explicitly require the insertion of a specific course on the theme. We must also consider that the undergraduate courses that did not obtain a maximum score in the CPC may have Human Rights Education in their curriculum. However, because they did not meet any of the evaluation indicators, they did not achieve the maximum grade.

Furthermore, it was observed that there is a greater concentration of themes related to inclusion, ethno-racial diversity, environmental education, political and cultural rights, such as racism, prejudice and discrimination against Afro-descendants and indigenous people; gender diversity, including feminism and women’s rights; right to gender identity, sexual and generational, as well as sexism and homophobia, which were identified in the analysis. Among other relevant topics, such as the inclusion of people with disabilities, with a greater emphasis on the rights of the deaf. Although the curricula have a higher incidence in terms of topics related to individual rights, it was also found the presence of contents that imply decision making and collective participation in the processes and in the educational settings and social coexistence, as for example, the topics democratic management, democratization, sustainability and more generally social rights, such as: right to health and education, as well as political, environmental and cultural rights, mentioned above, which denotes the understanding that human rights should interconnect the human relationship with all species on the planet in an ethically sustainable way.

We must also take into consideration that the updating of an undergraduate pedagogical project is a complex process and requires the collective, democratic, and engaged participation of all those involved. Therefore, it requires time for elaboration, appreciation by the parties, discussion, revisions, debates and deliberation by all the administrative and pedagogical bodies of the IFES, which can take months or even years to finish. It is understood that, in recent years, the constant changes of government leaders, cuts in investments in education, financial constraints, and attacks on the social function of the Federal Universities, the dismissal of the counselors of the CNE in the midst of debates that involved a new National Curricular Base for basic education and teacher training, and, subsequently, the approval of these Bases, without the approval of the entities and the professionals of education, bring conflicts and uncertainties to the Brazilian educational scenario as to the directions that the state power has given to public policies dedicated to this area. However, it is also considered that federal public institutions can and should take a political stand against the above-mentioned governmental actions, and many have done so fiercely. Therefore, implementing curricula focused on Human Rights Education is part of this process of resistance and struggle against violations of rights, especially those generated by authoritarian governments that disregard education as a constitutional social right and insist on using it as a commodity.

In this understanding, it is considered that the IFES have been building curricula that are more engaged with social demands and with the training of future teachers directed towards Human Rights. However, it is emphasized that in face of so many violations of rights that occur daily in Brazilian society, including those coming from the government, it is necessary that the professionals involved in the construction of the curriculum are attentive to the demands of society and the training of teachers. Because to educate for Human Rights is also to educate for the recognition and claim of the right to quality education. Teacher training as an inseparable factor in the improvement of education quality standards cannot be dissociated from training for Human Rights Education.

We still believe in the importance of a curricular emphasis on Human Rights so that it is not offered as an isolated subject or through isolated contents, but accordinbg to a transversal approach guiding the whole as a while throughout the undergraduate student education. Consequently, it is understood that this transversalization must be carried out based on methodologies that enable interdisciplinarity among academic knowledge. And, finally, that public policies for teacher education cease to be a government policy and become an educational policy, built in a collective and democratic way.

As for research limitations, we must consider that in the documentary approach of the prescribed curricula is not possible to identify how these same curricula are translated into the pedagogical daily routine, nor how the actors will conduct this theme in the curriculum in action by also considering that the curriculum is built in the educational daily routine, in the translation of its actors of the prescribed curricula, being made at every moment in the classrooms, in the relationships between students and teachers and in many other places of life.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, Márcia Ângela da Silva. Relato da resistência à instituição da BNCC pelo conselho nacional de educação mediante pedido de vista e declarações de votos. In: AGUIAR, Márcia Ângela da Silva; DOURADO, Luiz Fernandes (org.). BNCC na contramão do PNE 2014-2024: avaliação e perspectivas. Recife: Anpae, 2018. p. 8-22. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA FILHO, Naomar de. Transdisciplinaridade e saúde coletiva. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva , Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 1/2, p. 5-20, 1997. [ Links ]

ANPED. Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação. Uma formação formatada . [S. l.]: Anped, 2019. Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/news/posicao-da-anped-sobre-texto-referencia-dcn-e-bncc-para-formacao-inicial-e-continuada-de . Acesso em: 27 jan. 2020. p. 1-14. [ Links ]

APPLE, Michael Whitman. A luta pela democracia na educação crítica. Revista e-Curriculum , São Paulo, v.15, n. 4, p. 894- 926, out./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

APPLE, Michael Whitman. Para além da lógica de mercado: compreendendo e opondo-se ao neoliberalismo. Tradução de Gilka Leite Garcia e Luciana Ache. Rio de janeiro: DP & A, 2005. [ Links ]

ARENDT, Hannah. As origens do totalitarismo . Tradução de Roberto Raposo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras: 1989. [ Links ]

ARROYO, Miguel González. Pedagogias em movimento: o que temos a aprender dos movimentos sociais? Currículo sem Fronteiras , v. 3, n. 1, p. 28-49, jan./jun. 2003. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen John. Reformar escolas: reformar professores e os terrores da performatividade. Revista Portuguesa de Educação , Braga, v. 15, n. 2, p. 3-23, 2002. [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, Hélio Radke et al. Mudanças nos pesos do CPC e seu impacto nos resultados de avaliação em universidades federais e privadas. Avaliação , Campinas; Sorocaba, v. 15, n. 3, p. 147-166, 2010. [ Links ]

BOAVENTURA, Edivaldo Machado. Um ensaio de sistematização do direito educacional. Revista de Informação Legislativa , Brasília, DF, v. 33, n. 131, p. 31-57, jul./set. 1996. [ Links ]

BRAGA, Isabela Cristina Marins; MACHADO, Juliana Lacerda; GUIMARÃES-IOSIF, Ranilce Mascarenhas. A política educacional no contexto neoliberal e suas implicações na profissionalização docente da educação básica. In: CUNHA, Célio da; JESUS, Wellington Ferreira de; GUIMARÃES-IOSIF, Ralnice (org.). A educação em novas arenas: políticas, pesquisas e perspectivas. Brasília, DF: Liber Livro: Unesco, 2014. p.151-168. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988 . Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, 1988. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm . Acesso em: 15 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parecer CNE/CP, n. 8/2012, homologado em 30 de maio de 2012. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para Educação em Direitos Humanos. Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF, seção I, p. 33, maio 2012a. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=10389-pcp008-12-pdf&category_slug=marco-2012-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 8 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Resolução nº 1, de 30 de maio de 2012. Estabelece as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para Educação em Direitos Humanos. Diário Oficial [da] União , Brasília, DF, seção I, p. 48, maio 2012b. Disponível em: portal.mec.gov.br/docman/maio-2012-pdf/10889-rcp001-12. Acesso em: 11 dez. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Casa Civil. Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. Lei n. 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014 . Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação. Brasília, DF: Casa Civil, 2014. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm . Acesso em: 15 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Superior. Caracterização dos cursos de graduação: análise do Conceito Preliminar de Curso (CPC) obtidos em 2008. v. 2. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Formação superior para a docência na educação básica . Brasília, DF: MEC, 2020. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/pet/323-secretarias-112877938/orgaos-vinculados-82187207/12861-formacao-superior-para-a-docencia-na-educacao-basica . Acesso em: 19 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Instrumentos de avaliação de cursos de graduação presencial e a distância: reconhecimento e renovação de reconhecimento. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2017. Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/avaliacao_cursos_graduacao/instrumentos/2017/curso_reconhecimento.pdf . Acesso em: 8 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Portaria n. 515, 14 de junho de 2018 . Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018. Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/indicadores/legislacao/2018/portaria_n515_de_14062018_define_indicadores_qualidade_2017.pdf . Acesso em: 2 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, Brigido Vizeu; JUSTO, Ana Maria. Iramuteq: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia , Ribeirão Preto, v. 21, n. 2, p. 513-518, dez. 2013b. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, Brigido Vizeu; JUSTO, Ana Maria. Tutorial para uso do software de análise textual Iramuteq. Florianópolis: UFSC, 2013a. Disponível em: http://www.iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/tutoriel-en-portugais . Acesso em: 2 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão. Ênfases e omissões no currículo. Educação & Sociedade , Campinss, v. 23, n. 78, p. 296-29, abr. 2002. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria Ferrão et al. Educação em direitos humanos e formação de professores(as). São Paulo: Cortez, 2013. (Docência em formação: saberes pedagógicos). [ Links ]

CELLARD, André. Análise documental. In: POUPART, Jean et al. A pesquisa qualitativa: enfoques epistemológicos e metodológicos. Tradução de Ana Cristina Nasser. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2008. p. 295-316 [ Links ]

DOURADO, Luiz Fernandes. Diretrizes curriculares nacionais para a formação inicial e continuada dos profissionais do magistério da educação básica: concepções e desafios. Educação & Sociedade , Campinas, v. 36, n. 131, p. 299-324, 2015. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. El grito manso . Buenos Aires: Siglo XIX, 2003. [ Links ]

GADOTTI, Moacir. Educação e poder: introdução à pedagogia do conflito. 13. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2003. [ Links ]

GALLO, Sílvio. Transversalidade e educação: pensando uma educação não-disciplinar. In: ALVES, Nilda; GARCIA, Regina Leite (org.). O sentido da escola . Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2000. p. 16-40. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Marcos Leite. Direitos humanos do bem viver: entre o conceito de bem viver e o novo constitucionalismo latino-americano. Revista de Direito e Sustentabilidade , Florianópolis, v. 1, n. 2, p. 246-265, jul./dez. 2015. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernardete Angelina. Formação de professores no Brasil: características e problemas. Educação & Sociedade , Campinas, v. 31, n. 113, p. 1355-1379, dez. 2010. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. Os professores como intelectuais: rumo a uma pedagogia crítica da aprendizagem. Trad. Daniel Bueno. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997. [ Links ]

GOODSON, Ivor. A construção social do currículo . Tradução Maria João Carvalho. Lisboa: Educa, 1997. [ Links ]

GOODSON, Ivor. Currículo, narrativa e o futuro social. Revista Brasileira de Educação , Rio de Janeiro, v. 12, n. 35, p. 241-252, 2007. [ Links ]

GUDYNAS, Eduardo; ACOSTA, Alberto. El buen vivir más allá del desarrollo. Revista Quéhacer , Lima, n. 181, p. 70-81, Feb./Mar. 2011. [ Links ]

IMBERNÓN, Francisco. Formação docente e profissional: formar-se para a mudança e incerteza. Trad. Silvana Cobucci Leite. 9. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. (Questões da nossa época). [ Links ]

JORDELET, Denise. A representação: noção transversal, ferramenta da transdisciplinaridade. Cadernos de Pesquisa , São Paulo, v. 46, n. 162, p. 1258-1271, out./dez. 2016. [ Links ]

KAMI, Maria Terumi Maruyam et al. Trabalho no consultório na rua: uso do software Iramuteq no apoio à pesquisa qualitativa. Escola Anna Nery , Rio de Janeiro, v. 20, n. 3, p. 1-5, 2016. [ Links ]

LOPES, Alice Casimiro. Discursos nas políticas de currículo. Currículo sem Fronteiras , Rio de Janeiro, v.6, n. 2, p. 33-52, jul./dez. 2006. [ Links ]

LOPES, Alice Casimiro; MACEDO, Elizabeth. Contribuições de Stephen Ball para o estudo de políticas de currículo. In: BALL, Stephen John; MAINARDES, Jefferson. Políticas educacionais: questões e dilemas. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. p. 248-282. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Elizabeth. Base Nacional Curricular Comum: novas formas de sociabilidade produzindo sentidos para educação. Revista e-Curriculum , São Paulo, v. 12, n. 03, p.1530-1555, out./dez. 2014. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Roberto Sidnei. Currículo: campo, conceito e pesquisa. 7. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017. [ Links ]

MOREIRA; Antonio Flavio Barbosa; SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da (org.). Currículo, cultura e sociedade . Tradução Maria Aparecida Baptista. 7. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. [ Links ]

MORIN, Edgar. A cabeça bem-feita: repensar a reforma, reformar o pensamento. Tradução Eloá Jacobina. 8. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2003. [ Links ]

NOLETO, Marlova Jovchelovitch. Prefácio. In: RANIERI, Nina Beatriz Stocco; ALVES, Ângela Limongi Alvarenga. Direito à educação e direitos na educação em perspectiva interdisciplinar . São Paulo: Cátedra Unesco de Direto à Educação: Universidade de São Paulo, 2018. p.5-6. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, Antonio. Entre a formação e a profissão: ensaio sobre o modo como nos tornamos professores. Currículo sem Fronteiras , Rio de Janeiro, v. 19, n. 1, p. 198-208, jan./abr. 2019. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Bruna Pinotti Garcia; LAZARI, Rafael de. Manual de direitos humanos . 4. ed. Salvador: JusPodvim, 2018. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. Carta internacional dos direitos humanos . [S. l.]: ONU, 1948a. Disponível em: https://nacoesunidas.org/direitoshumanos/declaracao/ . Acesso em: 26 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. Conferência Mundial dos Direitos Humanos, Declaração e Programa de Ação de Viena . [S. l.]: ONU, 1993. Disponível em: http://www.direitoshumanos.usp.br/index.php/Sistema-Global.-Declara%C3%A7%C3%B5es-e-Tratados-Internacionais-de-rote%C3%A7%C3%A3o/declaracao-e-programa-de-acao-de-viena.html . Acesso em: 26 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. Declaração Universal dos Direitos Humanos de 10 de dezembro de 1948 . [S. l.]: ONU, 1948b. Disponível em: https://nacoesunidas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DUDH.pdf . Acesso em: 26 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. Diretrizes para planos nacionais de ação para educação em direitos humanos. Resolução A/52/469/Add, 1 D, 20 out. 1997 . Disponível em: 1997. http://www.dhnet.org.br/dados/pp/edh/mundo/onu_diretrizes_planos_nac.pdf . Acesso em: 01 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. Resolução n. 49/18 . Década das Nações Unidas para a educação em matéria de direitos humanos. 94ª reunião plenária 23 de dezembro de 1994. Disponível em: http://gddc.ministeriopublico.pt/sites/default/files/documentos/pdf/serie_decada_1_b_nacoes_unidas_educacao_dh_.pdf . Acesso em: 01 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

ONU. Organização das Nações Unidas. R esolución 66/137 aprobada el 19 de diciembre de 2011 . Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre educación y formación en materia de derechos humanos. [S. l.]: ONU, 2011. Disponível em: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/467/07/PDF/N1146707.pdf?OpenElement . Acesso em: 26 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

OPERTTI, Renato; KANG, Hyekyung; MAGNI, Giorgia. Comparative analysis of the national curriculum frameworks of five countries: Brazil, Cambodia, Finland, Kenya and Peru. [S. l.]: ONU: Unesco, 2018. [ Links ]

PARASKEVA, João Menelau; GANDIN, Luis Armando; HYPOLITO, Álvaro Moreira. Imperiosa necessidade de uma teoria e prática pedagógica radical crítica: diálogo com Jurjo Torres Santomé. Currículo sem Fronteiras , Rio de Janerio, v. 4, n. 2, p. 5-32, jul./dez. 2004. [ Links ]

RAMOS, André de Carvalho. Curso de direitos humanos . 4. ed. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2017. [ Links ]

RANIERI, Nina Beatriz Stocco. O direito educacional no sistema jurídico brasileiro. In: Justiça pela qualidade na educação: Associação Brasileira de Magistrados, Promotores de Justiça e Defensores Públicos da Infância e da Juventude. Todos pela Educação. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2013. p. 55-103. [ Links ]

RICHARDSON, Roberto Jarry. Pesquisa social: métodos e técnicas. 3. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2012. Colaboradores José Augusto de Souza Peres et al. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, José Gimeno (org.). Saberes e incertezas sobre o currículo . Porto Alegre: Penso, 2013. [ Links ]

SANTOMÉ, Jurjo Torres. As culturas negadas e silenciadas no currículo. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Alienígenas na sala de aula . Petropólis: Vozes, 2013. p. 159-177. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Akiko. Complexidade e transdisciplinaridade em educação: cinco princípios para resgatar o elo perdido. Revista Brasileira de Educação , Rio de Janeiro, v. 13, n. 37, p. 71-83, abr. 2008. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. A universidade do século XXI: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da universidade. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa; MARTINS, Bruno Sena (org.). O pluriverso dos direitos humanos: a diversidade das lutas por dignidade. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2019. p. 514 (Epistemologias do sul; 2). [ Links ]

SILVA, Aida Maria Monteiro; TAVARES, Celma. Educação em direitos humanos no Brasil: contexto, processo de desenvolvimento, conquistas e limites. Revista Educação , Porto Alegre, v. 36, n. 1, p. 50-58, jan./abr. 2013. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da. Documentos de identidad e: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2017. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, Rosa Maria Godoy et al. Educação em direitos humanos: fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. João Pessoa: Universitária, 2007. [ Links ]

TAVARES, Celma. Educar em direitos humanos, o desafio da formação dos educadores numa perspectiva interdisciplinar. In: SILVEIRA, Rosa Maria Godoy et al. Educação em direitos humanos: fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. João Pessoa: Universitária, 2007. p. 487-503. [ Links ]

TRAVERSINI, Clarice Salete. Currículo e avaliação na contemporaneidade: há lugar para a diferença em tempos imperativos dos números? In: FAVACHO, André Márcio Picanço; PACHECO, José Augusto; SALES, Shirlei Rezende. Currículo, conhecimento e avaliação: divergências e tensões. Curitiba: CRV, 2013. p. 117-190. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Plano de ação do Programa Mundial para Educação em Direitos Humanos: primeira fase. Nova York; Genebra, Unesco, 2006. Disponível em: http://www.dhnet.org.br/dados/textos/edh/br/plano_acao_programa_mundial_edh_pt.pdf . Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Plano de ação do Programa Mundial para Educação em Direitos Humanos: segunda fase. Brasília, DF: Unesco, 2012. Disponível em: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002173/217350por.pdf . Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Plano de ação do Programa Mundial para Educação em Direitos Humanos: terceira fase. Brasília, DF: Unesco, 2015. Disponível em: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002329/232922POR.pdf . Acesso em: 25 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

2- It is a social construction for specific educational purposes, which aims at a training coupled with pedagogical processes and procedures, in the relationship with the knowledge that is elected as educational (GOODSON, 1997; MACEDO, 2017).

3- “Cultural references whereby the curriculum is understood, proposed and daily constructed” (MACEDO, 2017, p. 84).

Received: June 02, 2020; Revised: November 24, 2020; Accepted: December 10, 2021

texto em

texto em