Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.47 São Paulo 2021 Epub 16-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202147227795

ARTICLES

The expansion of public and private schools in the outskirts of São Paulo (1900-1964)*

1- Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil. Contact: novadrica@gmail.com.

This article deals with the expansion of public and private schools in the East periphery of the city of São Paulo in the first decades of the 20th century. The original research, which resulted in this text, studied the expansion of private school in the East region of the city. Our initial hypothesis was that this expansion was not a phenomenon from the new millennium, but that would have been happening since the 20th century. The hypothesis was proved; as data has shown that the private expansion was concomitant with the formation of the East periphery. We used georeferencing to create maps of this expansion in time and space from quantitative data of public and private schools in the East region of São Paulo provided by the State Secretary of Education. Our analysis was based on the literature about education and peripheries, considering racial relations to discuss the growth of public and private schools. We concluded that the expansion of private schools was always present during the formation of the East periphery. We also confirm the popular participation in contributing for the expansion of public school in the region.

Key words: Private schools; Public schools; Periphery; School expansion; Racial relations

Este artigo tem como tema a expansão das escolas públicas e privadas da periferia leste de São Paulo nas primeiras décadas do século XX. A pesquisa originária que resultou neste texto teve como objeto a expansão da escola privada na Zona Leste de São Paulo, cuja hipótese inicial era de que tal expansão não era um fenômeno recente do novo milênio, mas que aconteceria desde o século XX. Hipótese comprovada, os dados demonstram que a expansão privada foi concomitante com a formação da periferia leste. Para tanto foram produzidos mapas desta expansão no tempo e no espaço, a partir de dados quantitativos das escolas públicas e privadas da Zona Leste de São Paulo fornecidos pela Secretaria Estadual de Educação (SEE). A técnica utilizada para a elaboração dos mapas foi o georreferenciamento. A análise foi realizada a partir da releitura da literatura sobre educação e periferia, considerando as relações raciais para discutir o crescimento das escolas públicas e privadas. A investigação permitiu concluir que a expansão da escola privada esteve presente durante a formação da periferia leste, além de confirmar a participação popular na contribuição da expansão da escola pública na região.

Palavras-Chave: Escolas privadas; Escolas públicas; Periferia; Expansão escolar; Relações raciais

Introduction2

Nosso tema é o óbvio. Acho mesmo que os cientistas trabalham é com o óbvio. O negócio deles – nosso negócio – é lidar com o óbvio.

Darcy Ribeiro (“Sobre o óbvio”).

Our theme is obvious. I do think that scientists work with the obvious. Their thing – our thing – is to deal with the obvious.

Darcy Ribeiro (“Sobre o óbvio”).

Brazilian education system is established by public and private schools according to Law 9.393/1996 of the National Educational Bases and Guidelines Law (BRASIL, 1996). Despite the obviousness of this statement, it is unusual to consider this system as an object of study in its totality, i.e, comparing the two administrative systems, in the area of sociology of education3. A first implication is the lack of analyses on the system, which consider the deep social contradictions that separates the schools by their publics, according to their economic condition, which characterizes the educational inequalities in Brazil.

Another implication is that not studying the educational system in its entirety blurs the naturalization of tha the model of quality school in Brazil is the private one4, with no criticism to what it represents in in social conflict5. It is said that Brazilian education has no quality, overshadowing the fact that there is an education that “works” and attends a very specific group that can afford this education. Consequently, the best job positions are occupied by those who did their school trajectory in private K-12 schools (ALMEIDA; NOGUEIRA, 2003; ALMEIDA, 2009; MENEZES FILHO, KIRSCHBAUM, 2015; SETTON; MARTUCCELLI, 2015). However, we highlight the neoliberal argument of quality of the private to the detriment of the public as a justification to increase the State, so well analyzed by critics, such as Fonseca (1992); Gentili (1995), and Oliveira (2009). Nevertheless, this will not be the bias discussed in this text, as it is interested on the naturalization of the social construction of the argument of private school quality.

The complexity is deepened when associating the intersection of racial relations to the problem of educational inequalities, through the economic perspective, as poverty has a color in Brazil: it is black. Classic studies in the end of the 20th century, such as Hasenbalg and Silva (1999), have shown that the racial component has been ignored or minimized in the analyzes on social stratification, when not portraying the role of racial discrimination in the social structure competition process, in which black people are in disadvantage. A process given by structural racism (ALMEIDA, 2018) that results in the inequality of opportunities between whites and non-whites as, for the later, their trajectories have a “deficit of ascending social mobility” and a “process of accumulating disadvantages” (HASENBALG; SILVA, 1999, p. 218). These are associated to the educational discrepancy that separates white people from black and mixed-race, those with an educational deficit, as corroborated by Lima (1999), in the same collection. More recent studies in the 21st century indicate that white people are overrepresented in private school and black people in the public schools (MENEZES FILHO; KIRSCHBAUM, 2015, p. 123-124). The racial factor is one of the most persistent in educational and professional inequalities (LIMA; PRATES, 2015). In general terms, the school for those who can pay is mainly white, while the public one, with less quality, is mostly black.

Recent studies have shown that low-income classes have opted for private school (CAMELO, 2014; SIQUEIRA; NOGUEIRA, 2017). They have mainly associated this phenomenon to the income increase during the Labor Party governments since the 2000s (NOGUEIRA, 2013). However, other studies show that the private expansion already took place in the 1980s in the city of São Paulo (DANTAS, 2013, 2018; MEDEIROS; JANUÁRIO, 2014). On its turn, this article wants to show that the growth of private schooling happened before that, together with the formation of the East periphery of São Paulo (DANTAS, 2018).

This text presents the results of a PhD research, whose main concern was to converge the urban history on the formation of the East periphery of São Paulo and the expansion on public and private schools in the region. The initial hypotheses was that it was not a recent phenomenon, from the new millennium, but that would have happened since the 20th century. The problem raised was related to the question: what would be the meaning of having private schools since the early 20th century, in a region considered a periphery? If private periphery school was not a recent phenomenon, why was it “hidden” in the studies and analysis on the region? What type of relation would it have with the expansion of the public school in the periphery, a phenomenon studied by Sposito (2002)? I present part of the theoretical conclusions in this text.

Methodologically, I used quantitative data of public and private schools in the East region of São Paulo, provided by the Secretaria Estadual de Educação (SEE- State Secretary of Education), which were crossed with georeferencing data on São Paulo school of Centro de Estudo da Metrópole (CEM- Centre for Metropolitan Studies (CEM))6, producing expansion maps in time and space. The data from SEE consisted on still-active private schools (those who were closed during this time were not available, thus are not in the maps), indicating that the number of these institutions might have been bigger. The results show that, since 1918, private establishment, especially denominational schools, were been created in the East region of São Paulo.

Besides this introduction, the article is divided into four parts. The first discusses the scope of the research, the East area of São Paulo and its formation. Later, I present the data on the schools between 1900 and 1945, corresponding to European immigration. The third part presents data regarding the internal migration that took place in the region, establishing as a limit the 1960s, during the military dictatorship, whose educational processes brought some other dynamics that would not fit in this article. The text ends with the final remarks.

The formation of the East region in São Paulo (1900-1960)

The city of São Paulo has 11,704,613 inhabitants according to the official estimates of São Paulo city hall. It is divided into five regions: Center (473,798 inhabitants), East (4,015,583), West (1,093,020), North (2,274,465), and South (3,847,747)7.

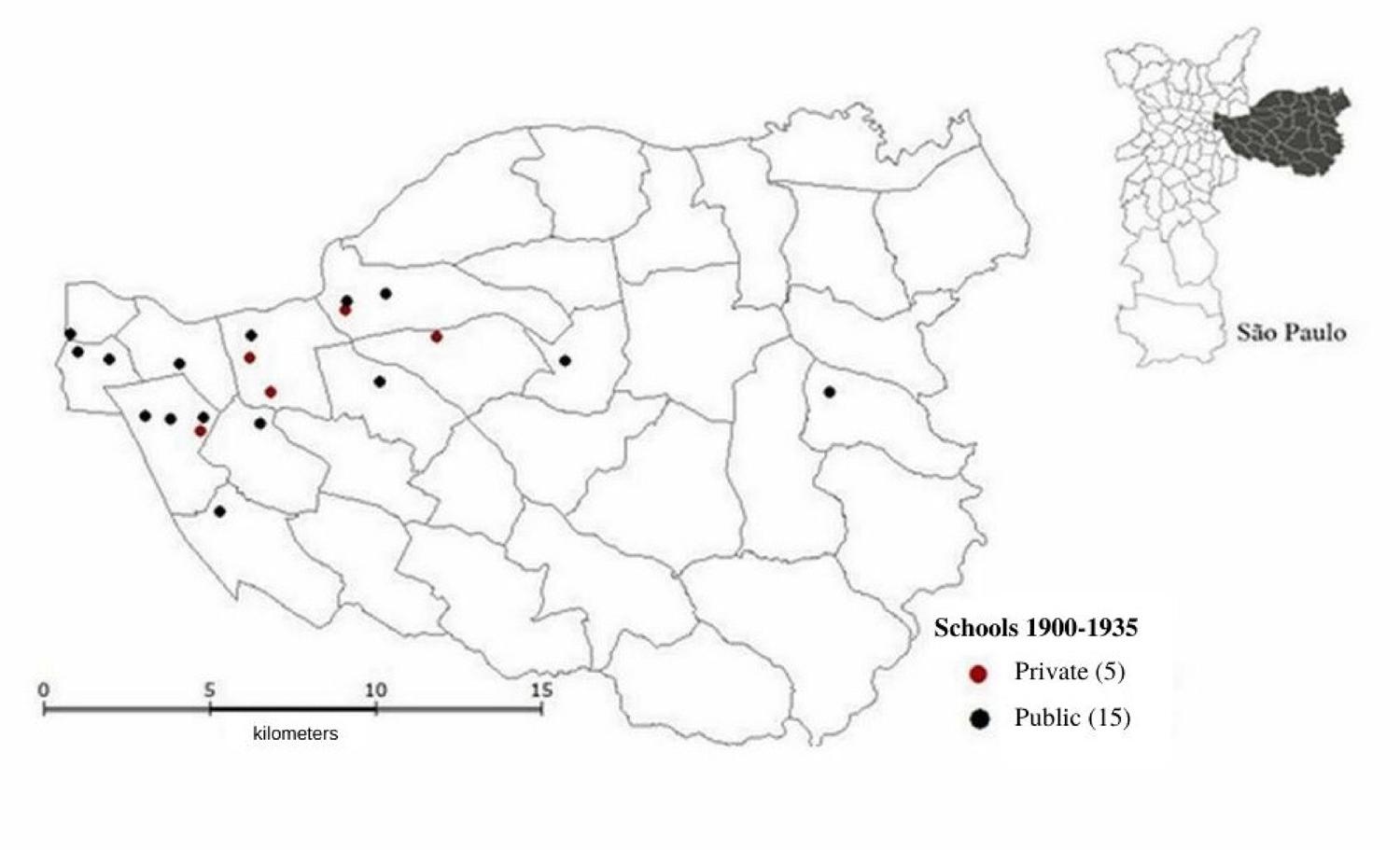

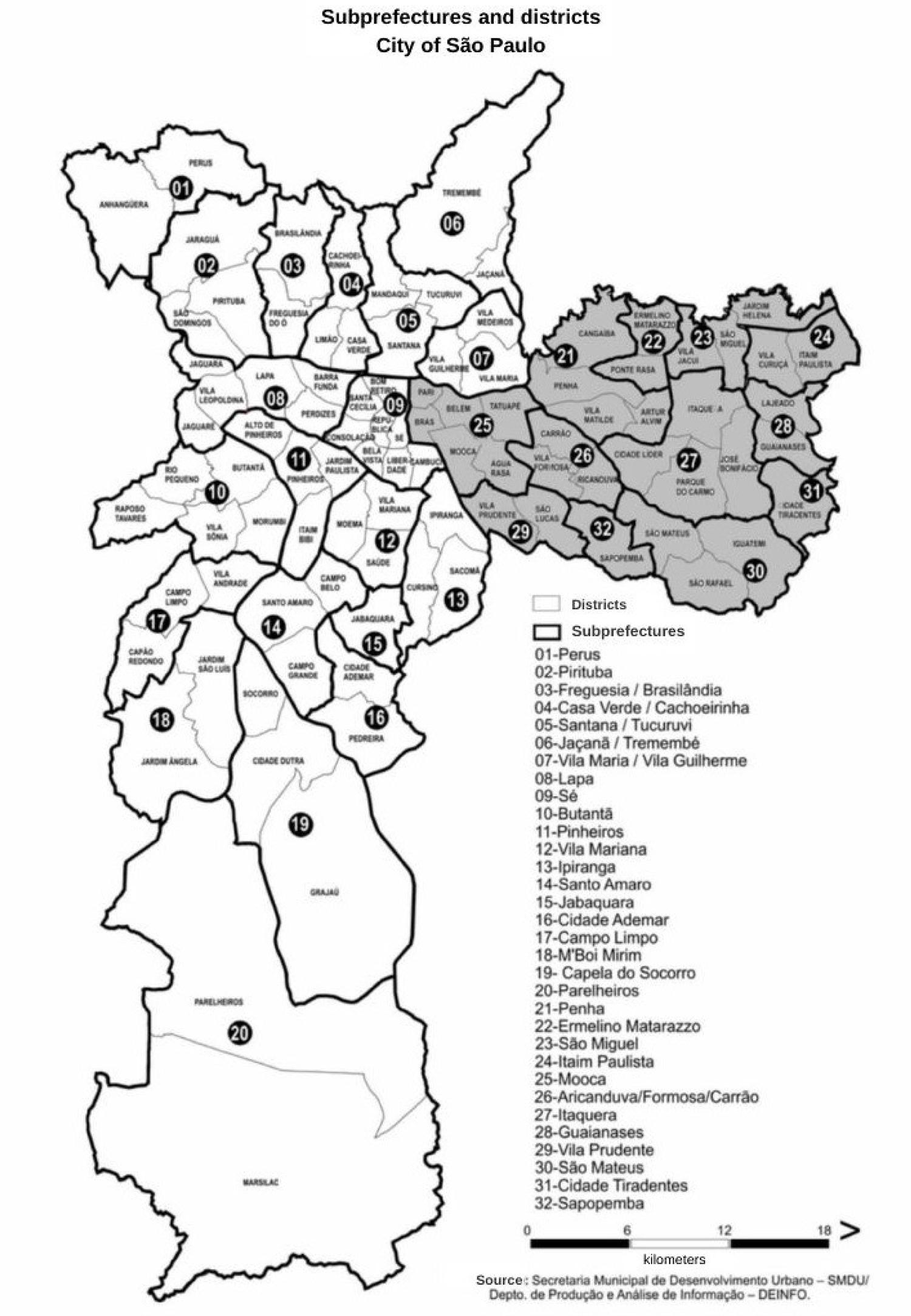

The city is also organized into 32 regional prefectures (former subprefectures), with 98 districts distributed among them. The scope of analysis chosen was the East region of São Paulo, for now on called ER, represented in grey in map 1 above. ER is the most populous of São Paulo, corresponding to 35.5% of São Paulo population, encompassing 12 regional prefectures and 33 districts (according to table 1).

Source: Infocidade - Regiões, Subprefeituras e Distritos. Available in: http://infocidade.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/mapas/3_regioes_subprefeituras_e_distritos_2014_10338.pdf> Accessed on: August 27, 2016. Treated by Alessandra Dantas.

Map 1 City of São Paulo by regional prefectures (old subprefectures)8

Table 1 Regional prefecture and ER districts

| Regional Prefecture | Districts |

|---|---|

| Aricanduva | Aricanduva, Carrão, and Vila Formosa |

| Cidade Tiradentes | Cidade Tiradentes |

| Ermelino Matarazzo | Ermelino Matarazzo, Ponte Rasa |

| Guaianases | Guaianases, Lajeado |

| Itaim Paulista | Itaim Paulista, Vila Curuçá |

| Itaquera | Cidade Líder, Itaquera, José Bonifácio, and Parque do Carmo |

| Mooca | Água Rasa, Belém, Brás, Mooca, Pari, and Tatuapé |

| Penha | Artur Alvim, Cangaíba, Penha, Vila Matilde |

| São Mateus | Iguatemi, São Mateus, and São Rafael |

| São Miguel | Jardim Helena, São Miguel, and Vila Jacuí |

| Sapopemba | Sapopemba |

| Vila Prudente | São Lucas and Vila Prudente |

Source: Infocidade (2018). Made by the author

The ER has gone through an occupation process intertwined with racial issues; nonetheless, urban and historiographic studies do not traditionally discuss this aspect. However, since the early 20th century, this region has received an immigrant European occupation and a migrant internal occupation after the 1930s (DANTAS, 2013), whose racial component was present, as will be discussed later on. On the other hand, black people who lived in São Paulo since the 19th century were been dislocated to territories in the margins of the big centers (ROLNIK, 1989). Such dynamic has contributed to the demographic growth. In1900, São Paulo had 239,820 inhabitants and in 1920 the population more than doubled, reaching 579,033 inhabitants9.

The immigrant occupation was related to the transition of the abolition of slavery and free work. The state of São Paulo, in the 19th century, benefited from the construction of railroads that favored the beginning of several activities (agricultural, commercial, and industrial) deisolating the region (CARONE, 2001; DEAN, 1991; MORSE, 1970). In the context of industrial modernization, studies indicate that São Paulo substituted black workers, previously slaves, by Europeans, especially Italians (ANDRADE, 1994). The main racial component at that time was the whitening process, supported by eugenic theories, which incentivized European migration in the city (DOMINGUES, 2004; LARA, 1988; GÓES, 2015). Black people, who were been pushed away to less valued places (ROLNIK, 1989), were also been “erased” from history as not participating of the growth of a modernizing city, what is contested by recent studies (SANTOS, 2008).

In1877, the railroad passed by the neighborhood of Brás, in the ER, turning its surroundings and the region of Belém and Mooca one of the first popular outskirts, occupied by Italians, Spanish, and Portuguese people who worked in the factories along the railroad. The first industry of consumer goods were established in this region (ANDRADE, 1994; ROLNIK, 2003). Many immigrants became small industry owners and some became great owners, as the Italian family Matarazzo, the biggest representative of the textile industry in the 20th century, which gives its name to of the ER districts: Ermelino Matarazzo (DANTAS, 2013; MARTINS, 1974).

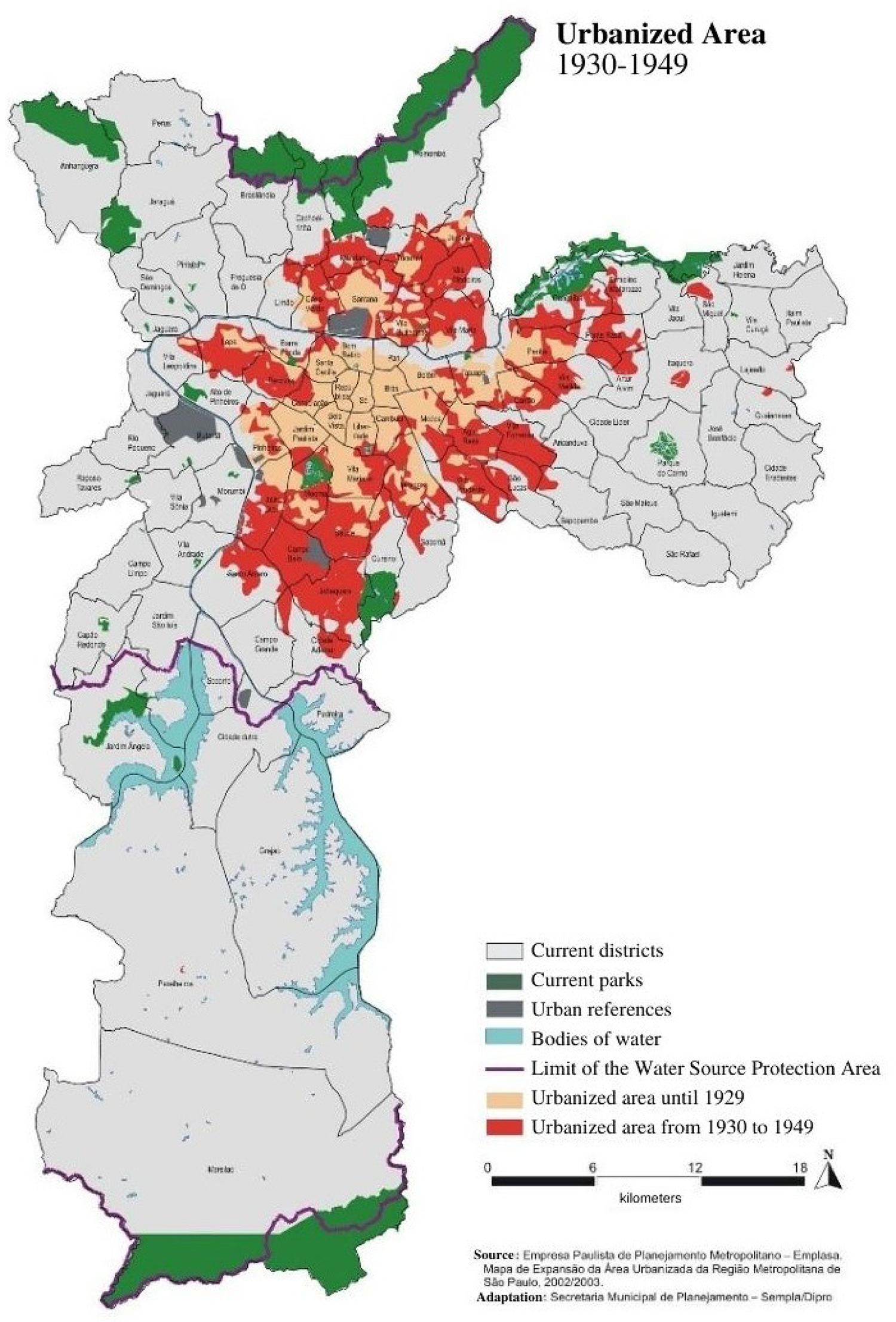

The urbanization of Mooca, Tatuapé, and Penha took place between 1915 and 1929, as can be seen in map 2. The immigrant occupation was socially discredited when compared to the great neighborhoods. It was part of the suburbs, more precarious, considered to be “another city” with an Italian accent (ANDRADE, 1994). After the gentrification process in the second half of the 20th century, it became the region with the most valued districts in the ER, mainly Mooca and Tatuapé.

Source: Histórico Demográfico do Município de São Paulo. Available in: http://smul.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/historico_demografico/1960.php. Accessed on September 25, 2018.

Map 2 Urbanized area (1930-1949)

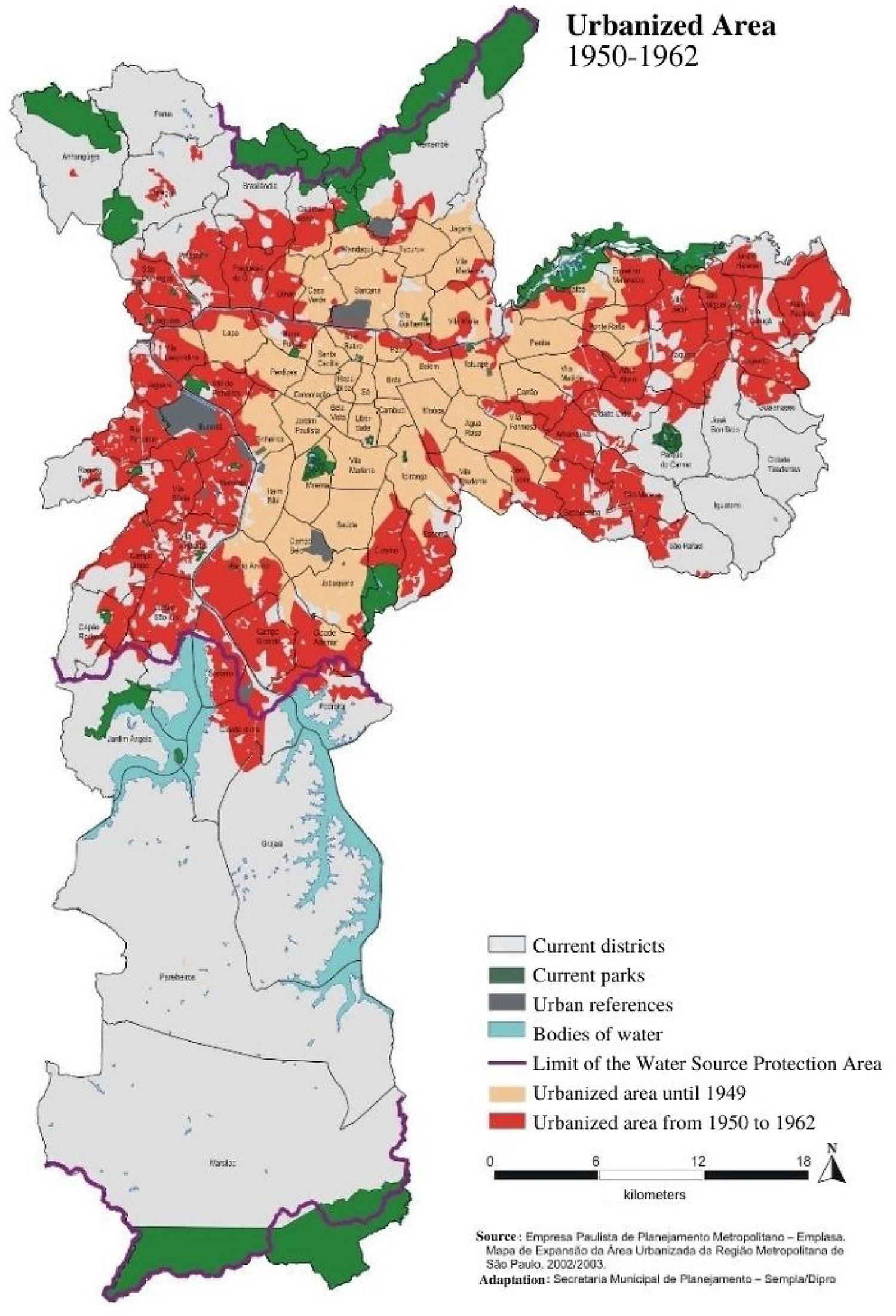

The migrant population derived from state policies of Getúlio Vargas’s government (1930-1945) aiming to change the workers profile by incentivizing national workforce in detriment of foreign one. According to Ribeiro (2001), the liberalism of the Old Republic did not fit the populist period, as the type of nation to be built needed a greater state intervention to face poverty through policies that valued work as a strategy of social climbing. In that context, São Paulo received national migrants from Brazil’s North and Northeast regions, tripling the population in 20 years. In 1940, the city had 1,326,261 inhabitants and 3,781,446 in 196010, increasing the urban area towards the East, as can be seen on map 3.

Source: Histórico Demográfico do Município de São Paulo. Available in: http://smul.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/historico_demografico/1960.php. Accessed on August 18, 2020.

Map 3 Urbanized area (1950-1960)

The arrival of the Nitro Química Industry in São Miguel Paulista in 1935 can be seen as a milestone of the migrant occupation in the ER. It was established in the valley of river Tietê and around the railroads, as the train would facilitate the machinery installation imported from the United States, which contributed to the implementation of this industry (FONTES, 1997, p. 29-30). The district of São Miguel Paulista and its surroundings became known as the “new Bahia” [a state in the Northeast of Brazil], due to the great number of Northeasterns who came to the city to work in the industry, changing the urban landscape of the region (FONTES, 2008, p. 92). The national migrants were stigmatized, known by the nickname of “baianos” [those from Bahia] as they were the majority. In this classification “[…] it is important not to ignore the racial component implicit by the term” (FONTES, 2008, p. 70), as most were black. The mostly white population of immigrant occupation had a significant change with the arrival of black migrants.

Besides the whitening or Europeanization process in the city of São Paulo, another phenomenon of social distinction took place: the “invention of Northeast” (Albuquerque Jr., 2009). According to the author, the modernizing South created a negative representation of the Northeast. In the social conflict established between these newly-arrived internal migrants and the immigrants, who came to establish a “more qualified” labor force, “[…] far from been developmental partners, the Northeast migrants were blamed and were eventual ‘scape goats’ to the hardships brought by the quick growth of the city” (FONTES, 2008, p. 72). A fact corroborated by Magalhães (2011), who indicated in her study that Northeasterns who moved to the ER suffered prejudiced from part of the older residents, immigrant descendants, in a symbolic separation between the established ones and the outsiders (ELIAS; SCOTSON, 2000).

Classic studies analyze this second occupation of the periphery, showing that various regions, including the ER, have gone through a process of urban spoliation, in which the working class was submitted to a super exploration by also being deprived of a basic infrastructure (CAMARGO et al., 1976; KOWARICK, 1993). While in the phase of immigrant occupation, there were ‘workers’ villages’ to this working class, in the period of migrant occupation the workers were responsible for their own housing, building it themselves and, later, forming the favelas (MARICATO, 1982; MAUTNER, 1999). To Dantas (2018), the migrants were more subject to this because they were submitted to rural spoliation in their places of origin, due to the abolition of slavery, which left a great number of black people with no land nor work in the rural areas.

Approaching the formation of the East region through the perspective of migrant and immigrant occupation aimed to converge the racial issue to re-read the urban and historic studies on the region with its implication in the expansion of public and private schools. Nowadays, we can see the result of this racial division in the population of the regional prefectures:

The regional prefectures of immigrant occupation (Mooca, Vila Prudente, Aricanduva, and Penha) have a high percentage of white residents, highlighting the three first one on table 2, with more than 74 %. In those 3, the percentage of black people is under 23%.

Table 2 Population by ethnicity by regional prefectures

| Population (2010) | % whites | % blacks* | % Asians | % Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mooca | 343980 | 80.1 | 16.9 | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| Vila Prudente | 246589 | 75.7 | 22.1 | 2.2 | 0.0 |

| Aricanduva | 267702 | 74.3 | 21.8 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

| Penha | 474659 | 66.7 | 31.3 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| Sapopemba | 284524 | 57.6 | 41.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Ermelino Matarazzo | 207509 | 58.8 | 39.4 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| São Mateus | 426794 | 53.9 | 45.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Itaquera | 523848 | 55.0 | 43.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| São Miguel | 369496 | 49.3 | 49.9 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Itaim Paulista | 373127 | 45.9 | 53.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Guaianases | 268508 | 45.1 | 54.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Cidade Tiradentes | 211501 | 43.4 | 56.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

Source: Data from IBGE aggregated by Infocidade (2016). *Black and mixed race. Made by the author.

On the other hand, we can see on table 2 that São Miguel, Itaim Paulista, Guaianases, and Cidade Tiradentes has a majority of black residents, with an average of 53% against 23% of the three first regional prefectures occupied by immigrants. Ermelino Matarazzo, São Mateus, and Itaquera have also had an occupation mostly composed by national migrants. It is difficult to cross these data with the enrollment of public and private students, as the information on racial declaration is not attached to the enrollment by administrative system. Therefore, due to this setback this analysis has limitations. In the next section, I will present the school expansion.

Schools of immigrant occupation (1900-1935)

In the period previous to the Republic, the secondary and higher education were in change of the General Power (Poder Geral) and the provinces were responsible for primary education. This first phase was mainly held by the private initiative since the colonial times and even after the Independence, according to Haidar (2008). In the province of São Paulo the official primary education was considered precarious: “The profession of primary teacher had little value not only in financial terms, but also in social recognition” (MARCÍLIO, 2005, p. 72).

During the first years of the Republic there were no significant changes regarding primary education, according to Nagle (1976). It was since the 1920s that the transformations started to be shaped in the scope of the states, the former provinces that were no longer responsible by initial public instruction. “In fact, during the decade, there was the substitution of the educational ideals held until then for the principles of a new educational theory represented by escola nova” (NAGLE, 1976, p. 190). 11

Denominational education had lost its power after the Proclamation of the Republic and the removal of religious education from the Constitution of 1891. However, Catholic Church influence in education restructured itself during Vargas’s government, materialized in 1931 by the legalization of optional religious education in public schools (Schwartzman, Bomeny, Costa, 2000). The great concern with school content aimed to stop the secularization of education proposed by Escola Nova thinkers, seen as a social threat, as it would open the way to a communist revolution. Generally, the State, even in an authoritarian regime such as Vargas, was not able to escape religious dominance, because it had to negotiate with this institution to fulfill its political objectives. For the author, the opposition of the Catholic Church against the Escola Nova movement led its precursors, such as Anísio Teixeira, to ostracism.

In that scenario, the educational project of the Military Forces gained a new boost as “the content of that pedagogy was the inculcation of principles of discipline, obedience, organization, respect to the order and to the institutions” (SCHWARTZMAN; BOMENY; COSTA, 2000, p. 84). The authors affirm: “the connection of education with national security issues confirm the idea that, in Estado Novo, education should establish itself as a strategic project of controlled mobilization” (SCHWARTZMAN; BOMENY; COSTA, 2000, p. 86). The central role of the primary school, to which no attention was previously paid, was understood as a disseminator of governmental ideology. One of its objectives was to build a national identity as a counterpoint to the cultural plurality resulting from immigration, thus its approximation with the Church and the military.

In this sense, the change of primary education, started in the 1920s by Escola Nova, has an ideological shift in the 1930s. In the words of Schwartzman, Bomeny, Costa (2000, p. 194-195): “It is then explicit one of the greatest divergences with the Escola Nova movement: while the later saw in school a tool to neutralize social inequalities, the Church perceived it as aiming the adaptation of the ‘unequals’ to a naturally hierarchical social order”. Even after the reforms, primary education continued under the responsibility of the states and secondary education of the federal government, which implemented vocational-technical education.

In the transition between the 19th and the 20th centuries, the expansion of primary private and public schools was in full swing in São Paulo. The population growth due to immigration, the first phase of industrialization, and the political context composed the panorama for the immigrant occupation of the East area of the city.

To Perosa (2009, p. 48), there was a denial of the commercial dimension of denominational private schools, consolidating in the elite regions of the city. When these schools were been established there was already a school market with strategies of creation of demands, competition among school, a hierarchy of the diplomas, and different fees depending on the clientele. One of the strategies used to soften the commercial dimension and legitimize the philanthropic character of denominational schools was to establish schools in poorer regions. As the East periphery expanded itself, public and private schools were been established simultaneously to the formation of ER, since the beginning of the 20th century, as indicated on table 3.

Table 3 First public and private schools in ER (1900-1935)

| Year | School | System | District |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | E.E. Orestes Guimarães | Public | Pari |

| 1909 | E.E. Amadeu Amaral | Public | Belém |

| 1911 | E.E. Carlos de Campos | Public | Brás |

| 1913 | E.E. Anchieta Padre | Public | Brás |

| 1913 | E.E. Santos Dumont | Public | Penha |

| 1914 | E.E. Oswaldo Cruz | Public | Mooca |

| 1918 | Colégio Santa Catarina | Private | Mooca |

| 1925 | E.E. Visconde de Congonhas do Campo | Public | Tatuapé |

| 1926 | Colégio São Francisco de Assis | Private | Tatuapé |

| 1926 | Colégio São Vicente de Paulo | Private | Penha |

| 1928 | E.E. Doutor Antonio de Queiroz Telles | Public | Mooca |

| 1931 | Colégio Espirito Santo | Private | Tatuapé |

| 1932 | Escola São José | Private | Vila Matilde |

| 1932 | E.E. Republica do Paraguay | Public | Vila Prudente |

| 1932 | E.E. Professora Maria Augusta de Ávila | Public | Artur Alvim |

| 1933 | E.E. Professor Theodoro de Moraes | Public | Água Rasa |

| 1933 | E.E. Barão de Ramalho | Public | Penha |

| 1935 | E.E. Pedro Taques | Public | Guaianases |

Source: Cadastro de Escolas Secretaria da Educação. “Relação de Escolas Ativas com Data do Ato de Autorização/Criação”. Date: May 2, 2016. Made by the author.

The first public schools in the ER coincide with the urban area until 1929 (see map 2), corresponding to the population increase of the immigrants that establish themselves in the districts of Brás, Belém, and Mooca. All private schools were in the immigrant occupation. Despite the small number of establishments compared to the public, we can presume that the number was higher. As the official data of SEE only provided the information on currently active schools, the private schools that closed throughout the time could not be counted.

The first private schools dates of 1918 and, as other denominational schools, had a missionary character of a “Christian education”, according to their online official documents. The Catholic schools participated on the formation of São Paulo elites (ALMEIDA, 2009), but were also present in less prestigious places (PEROSA, 2009), as they are the continuity of a historic process in which the Catholic Church represented part of Brazilian formal education. The religious institutions restructured themselves in the Old Republic, according to Miceli (1985), expanding its domains even after the separation between State and Church in the Proclamation of the Republic.

The denominational private and public schools show that the process of peripheral expansion, or suburbs as it was known at the time, was more complex than what is been discussed on the works about this urban space, shown in map 4 below.

The schools of migrant occupation (1935-1964)

The migrant occupation coincides with the strong industrialization phase in Brazil, guided by the developmental policies of Getúlio Vargas, through which Brazilian State created several state companies, fomenting internal migration to answer the need of national workforce (CANO, 2015; PAIVA, 2004). The industries of ER were established along river Tietê, following the railroad, as well as in the city of Guarulhos, in the other side of the river (TOLEDO, 2011).

The periphery was not prepared to receive the new population contingent, which was submitted to urban spoliation, as previously mentioned. Contrary to what had happened when foreign workers arrived, neither the State nor the industries, took the responsibility for the necessary infrastructure to receive this people, reinforcing the stigma against Northeasterns as responsible for urban problems.

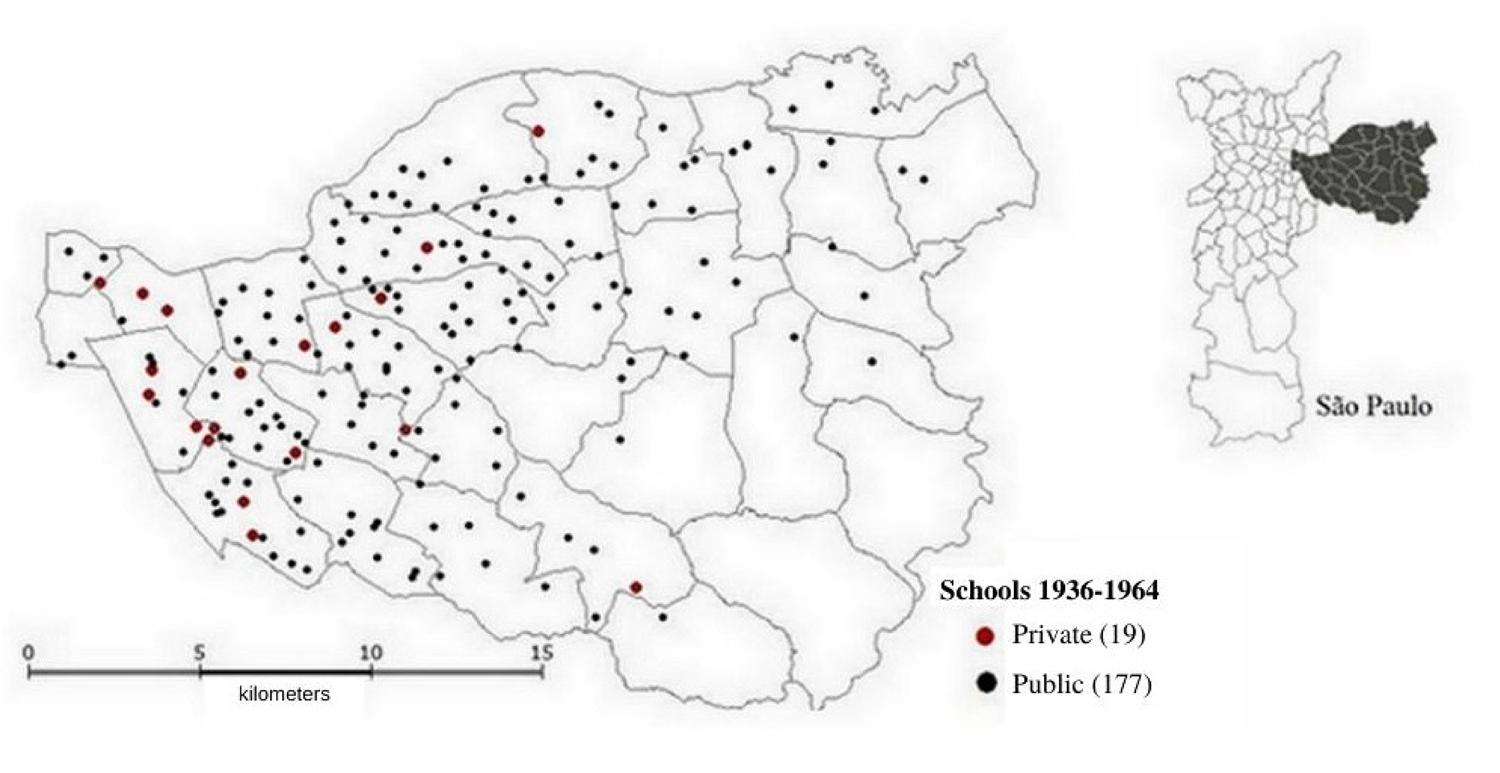

However, a great part of the migrant population arriving in the ER could not afford private education. Urban spoliation to the periphery regions foments social movements that exploded in the region demanding infrastructure and social rights, such as education (ANDRADE, 1989; IFFLY, 2010; SADER, 1988, SPOSITO, 2002). The actors of the social movements allowed the onset of populism12, which answered the demands of low-income classes to educate their children. The popular organization contributed to the change in urban landscape due to the intense demands that forced public power to open new public schools, as shown in map 5.

Source: CEM, 2012, 2013, 2016 (Censo 2013 INEP/MEC). Cadastro de Escolas da SEE, 2016” . Made by the author.

Map 5 Public and private schools of migrant occupation – East region

Since the 1950s, the pace of public school creation changes completely: 3 schools between 1936 and 1940; 18 between 1941 and 1950; 156 schools between 1951 and 1964, the year of the military coup d’état, which delimitates our data13. Due to the short budget for social areas, such as education, schools were created in an improvised fashion, for instance, in wooden warehouses.

Sposito’s (2002) work has shown that the 1950s was a milestone for public school because of the popular power that negotiated with the public power, which, on its turn, was sensible to the demands of the periphery. This promoted a singular enlargement of the public system in the history of São Paulo. Though this increase was precarious, it has crossed some barriers, as, besides the extension of elementary education, it demanded the creation of secondary school, a level that was still mainly restricted to the elite.

On the other hand, yet in Getulio Vargas’s period, the novelty of the private system was to prepare these new workers to join the workforce, as Vargas’s government delegated to the industries the professional qualification of their workers, through the organic laws (ROMANELLI, 2006, p. 155). Thus, the “Serviço Nacional Aprendizagem Industrial” (SENAI- National Service of Industrial Learning) was created in 1942 and the Serviço Social da Indústria (SESI- Social Service of the Industries) in1946. Despite being a private company, its financial resources came from the social security charges (REPAS, 2008), pointing out the tradition of using public resources in the private educational sector (OLIVEIRA, 2009).

In the period of migrant occupation, three vocational schools appeared in this educational system, the first was the SENAI School Felício Lanzara in the district of Mooca in 1942, as shown below on table 414.

Table 4 Private schools of migrant occupation (1936-1965)

| Year | School | District |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Colégio Mary Ward | Carrão |

| 1939 | Colégio Santo Antônio de Lisboa | Tatuapé |

| 1940 | Colégio Joao XXIII | Vila Prudente |

| 1941 | Colégio Nossa Senhora de Lourdes | Água Rasa |

| 1941 | Colégio Franciscano Nossa Senhora do Carmo | Vila Prudente |

| 1942 | Escola Senai Felício Lanzara | Mooca |

| 1943 | Colégio Bom Jesus - Vicente Pallotti | Vila Matilde |

| 1949 | Externato Nossa Senhora Sagrado Coração | Vila Formosa |

| 1953 | Escola Santa Izildinha | São Mateus |

| 1954 | Colégio Olivetano | Penha |

| 1955 | Instituto Nossa Senhora Auxiliadora | Belém |

| 1956 | Educandário Nossa Senhora Aparecida | Vila Prudente |

| 1956 | Colégio São Judas Tadeu | Mooca |

| 1958 | Externato Nossa Senhora Menina | Água Rasa |

| 1958 | Colégio Franciscano São Miguel Arcanjo | Vila Prudente |

| 1958 | Escola Santa Maria | Pari |

| 1962 | Colégio Parque Sevilha | São Lucas |

| 1964 | Centro Educacional Sesi 074 | Ermelino Matarazzo |

| 1964 | Externato São Rafael | Mooca |

| 1964 | Centro Educacional Sesi 032 | Belém |

Source: Cadastro de Escolas Secretaria da Educação. “Relação De Escolas Ativas Com Data Do Ato De Autorização/Criação” Date: May 2, 2016. Made by the author.

Among the schools still active, 19 private establishments, mostly denominational, corroborate with the perspective that religious education had a strong social appeal. These schools were concentrated in the older regional prefectures, such as Mooca, Penha, and Vila Prudente. Their creation history is similar to the previous period with the mission to attend the poor. Nowadays they are prestigious schools that use the appeal of Catholic education as an instrument of humanistic formation, presenting it as a criterion for parental school choice.

The second novelty on private schools was the establishment of institutions opened by regular people and not religious orders. However, two of them have religious names: Escola Santa Izildinha (1953- School Saint Izildinha) and Colégio São Judas Tadeu (1956- School Saint Jude)15.

Escola Santa Izildinha was founded in 1953 in São Mateus. Despite the name of the saint, it was founded by a believer and not by a Catholic order. On its turn, Escola São Judas Tadeu was created by a couple of teachers, from the countryside of São Paulo, who noticed an educational deficit in the region. It started as a preparatory course for the admission exam to the former ginásio (corresponding to the current middle school). The initiative was highly successful and other classrooms were opened to attend the demand.

The non-religious private educational agents perceived the lack of schools and opened their own establishments. As teachers, they had the cultural capital needed to fill the gap of the time to endeavor and enable the business. The third establishment founded by laic people, Colégio Sevilha, in1962, has a secular name, moving away from the Catholic tradition.

These initiatives show that, during the process of expanding the periphery, private agents saw in the educational sector an opportunity of offer a service to the population. They suggest that private school was the administrative system that allowed an education befitting to a class fraction that established these new urban spaces. Other qualitative studies need to be conducted to check these hypotheses. However, it is a fact that there was a demand to the offer, as these schools have become references in the region.

Thus, despite State’s role as a provider and regulator of education, the principle of plurality and families’ freedom of choice have allowed educational private offer. It is important to highlight that the enrollments in the private system were always smaller than in the public one. Its access, through monthly fees, financially separates students, therefore not constituting a choice (CURY, 2008).

Final remarks

This article shows that the presence of private schools in the East periphery of São Paulo dates to the beginning of the 20th century. Therefore, it is not a new phenomenon, but took place together with the formation of the area. It is important to highlight that the experience of school expansion in the ER is quite specific to São Paulo, hence it cannot be generalized. However, its configuration in the social and historical context can help think some senses of Brazilian education.

The thesis that the presence of private schools in the periphery is not recent points out towards a political and social power, especially in denominational education, in the educational system throughout time. There is a naturalization of the coexistence of private schools without questioning what it represents to the totality of the educational system, beyond commodification, so well discussed by various authors (FONSECA, 1992; GENTILI, 1995; OLIVEIRA, 2009) who denounce the neoliberal policies deepened since the 1990s. The primary education offered by private schools had its primacy even before Republican public elementary schools (DANTAS, 2018). Its political power was shown against the Escola Nova project and its participation in the education regulation, granting private education little state interference. Throughout time, according to Cury (2008), the influence of private sectors in education had its space secured in the Law of National Educational Bases and Guidelines, even in its current 1996 version, which allowed the transfer of public resources to denominational and philanthropic schools.

Since colonial times, there was a gap on the project of public and free primary school, championed by the precursors of Escola Nova in the 1920s-1930s, mainly opposed by the private and denominational school tradition. The expansion of primary public school was connected to the counter position of an education proposed by the immigrants, seen as a threat in Vargas’s period. This workforce, once incentivized to whiten the nation, was at that time substituted by national migrants, mainly from the Northeast region, racially recomposing the city of São Paulo, especially the East periphery.

By bringing migrant and immigrant occupation to the analysis of the schools, we can see that the ER has gone through its own processes in which the racial issue was present. Based on the studies about the periphery, I defended this analysis which considers the racial facts. Classic texts, some presented during this text, touch on the topic, indicating that most internal migrants were stigmatized for being Northeasterns and black, without focusing on this criterion to structure the relations.

By associating school expansion and periphery formation, it was possible to bring up Oliveira’s (2013) criticism on the lack of the racial factor in the analysis of urban segregation, electing the socioeconomic factor as the main analytical issues. This criticism can be expanded to the analysis of educational inequalities.

During the growth of the periphery, several actors assimilated that scenario as an opportunity to enter in the educational market, opening new schools due to the educational deficit. Not only the Catholic Church but also other agents, as, for instance, teachers, perceived an opportunity to offer their services to richer class fractions in the ER, who could afford the investment on private education. Such assimilation agents contributed to the transformation of the territory and, with time, these establishments became famous.

On its turn, the migrants who went to São Paulo had little or no formal education and, in the city, fought for their children to attend public school. This refers to the power of political participation, which contributed to strengthen the expansion of public education. Such context opened up space for politicians that escaped an elitist tradition, but that identified in the popular demand an opportunity in the political game. Populism was an inflection that allowed popular participation leading to changes in the scenario of public schools in the ER. These were agents of resistance, which organized themselves in social movements to demand improvements not only in the infrastructure but also in the educational field.

On the other hand, the popular participation of internal migrants is little associated to a demand of public schools in the periphery by black people. This provocation needs to be better developed and discussed in future studies, but data suggest this relation. Certainly, despite all this mobilization, which resulted in the increase of public schools in the region, as a social conflict, we can perceive that it was not established as a project aiming to qualitatively compete with private schools attending the population that historically had higher educational levels.

REFERENCES

ALBUQUERQUE JR, Durval. A invenção do nordeste e outras artes. 4. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2009. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Ana Maria. As escolas dos dirigentes paulistas: ensino médio, vestibular, desigualdade social. Belo Horizonte: Argvmentvm, 2009. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Ana Maria; NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice (org.). A escolarização das elites: um panorama internacional da pesquisa. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2003. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Silvio. O que é racismo estrutural? Belo Horizonte: Letramento, 2018. (Feminismos plurais). [ Links ]

ANDRADE, Cleide. As lutas sociais por moradia de São Paulo: a experiência de São Miguel Paulista e Ermelino Matarazzo. 1989. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Sociais) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1989. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, Margarida. Brás, Mooca e Belenzinho – “bairros italianos” na São Paulo Além-Tamanduateí. Revista do Departamento de Geografia, São Paulo, n. 8, p. 97-102, 1994. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Brasília, DF: [s. n.], 1996. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, Candido et al. São Paulo 1975: crescimento e pobreza. 5. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 1976. [ Links ]

CAMELO, Rafael. A educação privada em São Paulo: expansão e perspectivas. São Paulo: Fundação Seade. (1ª análise Seade; n. 19.out. 2014). [ Links ]

CANO, Wilson. Crise e industrialização no Brasil entre 1929 e 1954: a reconstrução do Estado Nacional e a política nacional de desenvolvimento. Revista de Economia Política, São Paulo, v. 35, n. 3, p. 444-460, set. 2015. [ Links ]

CARONE, Edgar. A evolução industrial de São Paulo (1889-1930). São Paulo: Senac, 2001. [ Links ]

CEM. Centro de Estudos da Metrópole. Base cartográfica digital georreferenciada das escolas da região metropolitana de São Paulo. São Paulo: CEM, 2013. [ Links ]

CEM. Centro de Estudos da Metrópole. Base de divisão territorial da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo (2010). São Paulo: CEM, 2012. [ Links ]

CEM. Centro de Estudos da Metrópole. Base de escolas georreferencidas na região metropolitana de São Paulo (2013). São Paulo: CEM, 2016. [ Links ]

COLLINS, Randall. Quatro tradições sociológicas. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2009. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Jamil. Um novo movimento da educação privada. In: ADRIÃO, Theresa; PERONI, Vera (org.). Público e privado na educação: novos elementos para o debate. São Paulo: Xamã, 2008. p. 17-26. [ Links ]

DANTAS, Adriana Santiago Rosa. As escolas privadas da periferia de São Paulo: uma análise desde a colonialidade do poder à brasileira. 2018. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018. [ Links ]

DANTAS, Adriana Santiago Rosa. Por dentro da quebrada: a heterogeneidade social de Ermelino Matarazzo e da periferia. 2013. Dissertação (Mestrado em Estudos Culturais) – Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2013. [ Links ]

DEAN, Warren. A industrialização de São Paulo (1880-1945). 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 1991. [ Links ]

DOMINGUES, Petrônio. Uma história não contada: negro, racismo e branqueamento em São Paulo no pós-abolição. São Paulo: Senac, 2004. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Norbert; SCOTSON, John. Os estabelecidos e os Outsiders: sociologia das relações de poder a partir de uma pequena comunidade. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2000. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Dirce. O pensamento privatista em educação. Campinas: Papirus, 1992. (Magistério: formação e trabalho pedagógico). [ Links ]

FONTES, Paulo. Trabalhadores e cidadãos: Nitro Química: a fábrica e as lutas operárias nos anos 50. São Paulo: Annablume, 1997. [ Links ]

FONTES, Paulo. Um nordeste em São Paulo: trabalhadores migrantes em São Miguel Paulista (1945-66). Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 2008. [ Links ]

GENTILI, Pablo (org). Pedagogia da exclusão: o neoliberalismo e a crise da escola pública. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995 [ Links ]

GÓES, Weber. Racismo, eugenia no pensamento conservador brasileiro: a proposta de povo em Renato Kehl. 2015. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Sociais) – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Marília, 2015. [ Links ]

GOMES, Lisandra Ogg; NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice. A excelência escolar em uma escola pública de ensino médio. Educação em Foco, Belo Horizonte, v. 20, n. 30, p. 189-208, Jan./abr. 2017. [ Links ]

HAIDAR, Maria de Lourdes Mariotto. O ensino secundário no Brasil Império. 2. ed. São Paulo: Edusp, 2008. [ Links ]

HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle. Educação e diferenças raciais na mobilidade ocupacional do Brasil. In: HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle; LIMA, Márcia. Cor e estratificação social. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 1999, p. 218-231. [ Links ]

IFFLY, Catherine. Transformar a metrópole: Igreja Católica, territórios e mobilizações sociais em São Paulo 1970-2000. São Paulo: Edunesp, 2010. [ Links ]

KOWARICK, Lúcio. A espoliação urbana. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1993. [ Links ]

LARA, Silvia. Escravidão, cidadania e história do trabalho no Brasil. Projeto História, São Paulo, v. 16, p. 25-38, fev. 1988. [ Links ]

LIMA, Márcia. O quadro das desigualdades. In: HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle; LIMA, Márcia. Cor e estratificação social. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 1999. p. 232-240. [ Links ]

LIMA, Márcia; PRATES, Ian. Desigualdades raciais no Brasil: um desafio persistente. In: ARRETCHE, Marta (org.). Trajetórias das desigualdades: como o Brasil mudou nos últimos cinquenta anos. São Paulo: Edunesp: CEM, 2015. p. 163-192. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Carlos Eduardo. População negra e escolarização na cidade de São Paulo nas décadas de 1920 e 1930. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, Valéria. Memória e história da Zona Leste de São Paulo: nota de pesquisa. In: SANTHIAGO, Ricardo; MAGALHÃES, Valéria Barbosa de (org.). Memória e diálogo: escutas da Zona Leste, visões sobre a história oral. São Paulo: Letra e Voz: Fapesp, 2011. p. 41-60. [ Links ]

MARCÍLO, Maria Luiza. História da escola em São Paulo e no Brasil. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo; Instituto Fernand Braudel, 2005. [ Links ]

MARICATO, Ermínia (org.). A produção capitalista da casa e (da cidade) no Brasil industrial. 2. ed. São Paulo: Alfa-Omega, 1982. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. Conde Matarazzo, o empresário e a empresa: estudo da sociologia do desenvolvimento. 2. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1974. [ Links ]

MAUTNER, Yvonne. A periferia como fronteira de expansão do capital. In: DEÁK, Csaba; SCHIFFER, Sueli Ramos (org.). O processo de urbanização no Brasil. São Paulo: Edusp, 1999. p. 245-259. [ Links ]

MEDEIROS, Jonas; JANUÁRIO, Adriano. A nova classe trabalhadora e a expansão da escola privada nas periferias da cidade de São Paulo. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPOCS, 38., 2014, Caxambu. Anais... Caxambu: Anpocs, 2014. p. 1-30. [ Links ]

MENEZES FILHO, Naercio; KIRSCHBAUM, Charles. Educação e desigualdades no Brasil. In: ARRETCHE, Marta (org.). Trajetórias das desigualdades: como o Brasil mudou nos últimos cinquenta anos. São Paulo: Edunesp: CEM, 2015. p. 109-132. [ Links ]

MICELI, Sérgio. A elite eclesiástica brasileira (1890-1930). 1985. Tese (Livre Docência em Sociologia) – Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1985. [ Links ]

MORSE, Richard. Formação histórica de São Paulo (de comunidade a metrópole). São Paulo: Difel, 1970. [ Links ]

NAGLE, Jorge. Educação e sociedade na Primeira República. São Paulo: EPU; Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Nacional de Material Escolar, 1976. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice. No fio da navalha – A (nova) classe média brasileira e sua opção pela escola particular. In: ROMANELLI, Geraldo; NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice; ZAGO, Nadir (org.). Família & escola: novas perspectivas de análise. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2013. p. 109-130. [ Links ]

NUNES, Clarice. Anísio Teixeira: a poesia da ação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 16, p.5-18, 2001. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Reinaldo. Interfaces entre as desigualdades urbanas e as desigualdades raciais no Brasil: observações sobre o Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. In: OLIVEIRA, Reinaldo (org.). A cidade e o negro no Brasil: cidadania e território. 2. ed. São Paulo: Alameda, 2013. p. 43-94. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Romualdo. A transformação da educação em mercadoria no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 30, n. 108, p. 739-760, out. 2009. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Odair da Cruz. Caminhos cruzados: migração e construção do Brasil moderno (1930-1950). Bauru: Edusc, 2004. [ Links ]

PEROSA, Graziela Serroni. Escola e destinos femininos: São Paulo (1950/1960). Belo Horizonte: Argvmentvm, 2009. [ Links ]

PEROSA, Graziela Serroni; DANTAS, Adriana Santiago Rosa. A escolha da escola privada em famílias dos grupos popularesI. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 43, n. 4, p. 987-1004, dez. 2017. [ Links ]

PEROSA, Graziela Serroni, LEBARON, Frédéric, LEITE, Cristiane. O espaço das desigualdades educativas no município de São Paulo. Pro-Posições. Campinas, v. 26, n. 2 (77), p. 99-118, maio/ago. 2015. [ Links ]

PREFEITURA DE SÃO PAULO. Infocidade. São Paulo: Prefeitura, 2015. Disponível em http://infocidade.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/. Acesso em: 22 out. 2018. [ Links ]

REPAS, Marcos. Escola e mobilidade social: um estudo sobre os egressos do Sesi Vila Cisper. 2008. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação: História, Política, Sociedade) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Darcy. Sobre o óbvio. Marília: Lutas Anticapital, 2019. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Luiz. Transformação geofísica e explosão urbana. In: SACHS, Ignacy; WILHEIM, Jorge; PINHEIRO, Paulo Sérgio (org.). Brasil: um século de transformações. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2001. p. 132-161. [ Links ]

ROLNIK, Raquel. A cidade e a lei: legislação, política urbana e territórios na cidade de São Paulo. 3. ed. São Paulo: Studio Nobel: Fapesp, 2003. [ Links ]

ROLNIK, Raquel. Territórios negros nas cidades brasileiras (etnicidade e cidade em São Paulo e Rio de Janeiro). Revista de Estudos Afro-Asiáticos, Universidade Cândido Mendes, Rio de Janeiro, n. 17. p. 29-41, set. 1989. [ Links ]

ROMANELLI, Otaíza. História da educação no Brasil (1930/1973). 30. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2006. [ Links ]

SADER, Eder. Quando novos personagens entraram em cena: experiências, falas e lutas dos trabalhadores da Grande São Paulo, 1970-80. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1988. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Carlos José. Nem tudo era italiano: São Paulo e pobreza: 1890-1915 3. ed. São Paulo: Annablume: Fapesp, 2008. [ Links ]

SCHWARTZMAN, Simon; BOMENY, Helena Maria Bousquet; COSTA, Vanda Maria Ribeiro. Tempos de Capanema. 2. ed. São Paulo: Paz e Terra: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2000. [ Links ]

SETTON, Maria da Graça; MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. Apresentação: a escola entre o reconhecimento, o mérito e a excelência. Educação e Pesquisa. São Paulo, v. 41, n.esp., p.1385-1391, 2015. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, Ana Rita; NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice. Focalizando um segmento específico da rede privada de ensino: escolas particulares de baixo custo. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 43, n. 4, p. 1005-1022, 2017. [ Links ]

SPOSITO, Marília. O povo vai à escola: a luta popular pela expansão do ensino público em São Paulo. 4. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2002. [ Links ]

TOLEDO, Edilene. Guarulhos, cidade industrial: aspectos da história e do patrimônio da industrialização num município da Grande São Paulo. Revista Mundos do Trabalho, Florianópolis, v. 3, n. 5, p. 166-185, 2011. [ Links ]

WEFFORT, Francisco. O populismo na política brasileira. 5. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2003. [ Links ]

2- I thank Gabriela Valente and the referees for their careful reading which pointed crucial points to be modified. Surely, the persistent inaccuracies are of my responsibility. The PhD research that resulted in this article was supervised by Prof. Dr. Maria da Graça Jacintho Setton. Capes/Fapesp Funding (Process 2015/05846-0), to which I thank.

3- A study that aimed to compare the social space of public and private schools in São Paulo was done by Perosa, Lebaron and Leite (2015), which has shown the correlation between private education in richer areas, with the group of higher educational level and better professional positions.

4- The quality public schools are similar to those presented in Gomes and Nogueira’s (2017) study, as they have a selective admission process, teachers have different work schedule and salaries, among other factors that distinguish this excellence establishments, which are not available to all.

5- The sociological tradition of conflict can be seen in Collins (2009).

6- This is a research institution established at Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas of Universidade de São Paulo, composed by a multidisciplinary group of researchers in social sciences. I thank them for the course offered by the geographer Daniel Waldvogel, whose help allowed me to assemble and prepare the database to produce the maps.

7 - Source: Infocidade. Available in https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/upload/urbanismo/infocidade/htmls/7_populacao_censitaria_e_projecoes_populac_2008_10573.html. Accessed on July 29, 2019.

9- Source: IBGE and Demografic Censu. Available in: http://smul.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/historico_demografico/tabelas.php Accessed on August 25, 2018.

10 - Source: IBGE, Censos Demográficos. Available in: http://smul.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/historico_demografico/tabelas.php. Accessed on August 25, 2018.

11- One of the leaders of Escola Nova movement was Anísio Teixeira who broke away from the Catholic Church, defending a public laic school, following the ideas of Jonh Dewey after his studies in the United States (NUNES, 2001).

12 - To Weffort (2003), populism was characterized by a mobilization of urban roots, whose processes as migrations and the expansion of the means of communication allowed the political participation of an illiterate population from rural areas.

13- In Dantas’s (2018) thesis, the process of private school expansion in the following years was sustained without the comparison with public schools. Due to the limitations of this article, I could not discuss this issue.

15- Information from the official websites of the schools. Santa Izildinha, available in: http://staizildinha.com.br/iesi/historico-menina-izildinha-iesi/. Accessed September 27, 2016. São Judas Tadeu, available in: https://www.usjt.br/a-sao-judas/. Accessed September 29, 2018.

Received: August 22, 2019; Revised: April 28, 2020; Accepted: September 14, 2020

texto em

texto em