Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.47 São Paulo 2021 Epub 23-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202147228013

ARTICLES

Philosophy in the National Curriculum Guidelines (Ocem) and in the National High School Exam (Enem): temporal and conceptual gaps

1- Universidade de Brasília (UnB) / Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (INEP), Brasília, DF, Brazil. Contact: ester.macedo@inep.gov.br

This article analyses the correspondence between the philosophy questions administered in the Brazilian National High School Exam (Enem) and the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines (Ocem), published in 2006, as a case study of the relationship between curriculum document and large scale assessment, having as theoretical framework what Stephen Ball and Richard Bow call “policy cycle” (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE, BALL; GOLD, 1992; MAINARDES, 2006). This study becomes particularly relevant given, on the one hand, the intermittence of the offering of philosophy in Brazilian high schools, and, on the other, the imminent reformulation of the exam, to conform to the new National Common Core (BNCC). This study highlights Ball and Bowe´s thesis that the “implementation” of curricular documents is neither automatic nor certain. By analyzing the Ocem as part of a web of educational policies for high school, of which the Enem and the BNCC are also part, the present study aims to contribute towards strengthening the place of philosophy in high school, by highlighting points of continuity and points of tension between the preexisting nodes of this web. This article is divided in three parts: 1) a quantitative overview of how the philosophy contents proposed by the Ocem were covered in the exam in the last twenty years, pointing out gaps that still persist; 2) exploration of some factors that explain these gaps, in particular the difference in origin and purpose of each of these instruments; 3) qualitative analysis of how the conceptual differences between the Ocem and the Enem translate in how philosophy appears in the exam throughout the years. In conclusion, I present some points of reflection about the prospect for philosophy on the exam in this new horizon after the publication of the new BNCC.

Key words: High school philosophy; Large scale assessment; National curriculum

Este artigo analisa a adesão dos itens de filosofia do Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (Enem) às Orientações Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio (Ocem), de 2006, como um estudo de caso da relação entre referencial curricular e avaliação em larga escala, usando como referencial teórico o ciclo de políticas de Stephen Ball e Richard Bowe (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE, BALL; GOLD, 1992; MAINARDES, 2006). Este estudo torna-se particularmente relevante dada, por um lado, a intermitência da filosofia nessa etapa de ensino, e, por outro, a iminente reformulação do exame, a partir da publicação da Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Por meio dessa análise, reforça-se a tese de que a operacionalização dos documentos curriculares no exame não é automática, nem garantida. Ao analisar as Ocem como parte de uma rede de políticas educacionais para o ensino médio, da qual o Enem e a nova BNCC também são parte, este artigo visa contribuir para o fortalecimento da filosofia no ensino médio, ao destacar pontos de continuidade e pontos de tensão entre nodos anteriores desta rede. Este estudo é dividido em três partes: 1) um panorama quantitativo da cobertura dos conteúdos de filosofia das Ocem ao longo dos vinte anos do Enem, pontuando lacunas que ainda persistem; 2) apresentação de alguns fatores que explicam essas lacunas, em particular as diferenças nas origens e objetivos de cada um desses instrumentos; 3) análise qualitativa de como as diferenças conceituais entre as Ocem e o Enem se manifestam nas temáticas de filosofia abordadas na prova ao longo dos anos. Como conclusão, apresentam-se alguns pontos de reflexão acerca da perspectiva para a filosofia no exame nesse novo horizonte pós-BNCC.

Palavras-Chave: Filosofia; Enem; Ocem; BNCC; Referenciais curriculares

Introduction

This article analyses the correspondence between the philosophy questions administered in the Brazilian National High School Exam (Enem) and the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines (Ocem), published in 2006, as a case study of the relationship between curriculum document and large scale assessment, having as theoretical framework what Stephen Ball and Richard Bow call “policy cycle” (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE, BALL; GOLD, 1992; MAINARDES, 2006). This study becomes particularly relevant given, on the one hand, the intermittence of the offering of philosophy in Brazilian high schools (cf. BENJAMIN, 1990; GARRET, 1967; HEGEL, 1822; MOORE, 1967; BRASIL, 1999, 2006; ALVES, 2002; MACEDO, 2011; GALLO, 2013), and, on the other, the imminent reformulation of the exam, to conform to the new National Common Core (BNCC) (BRASIL, 2018b). Because it deals with high school philosophy as educational policy, this article is situated in the intersection of philosophy, education and public policy.

But why examine the presence of philosophy in the Brazilian High School Exam in terms of previous curriculum documents? And how does Ball and Bowe´s policy cycle contribute to this discussion?

Curriculum documents do not arise in a vacuum, but are fruits of debates and sociopolitical struggle in a dynamic that Ball and Bowe call “policy cycle” (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE; BALL; GOLD, 1992; MAINARDES, 2006). From this theoretical point of view, that elaboration and “implementation” of educational policy does not happen in a linear and static fashion, but rather from a countless variety of interactions among micro and macro spheres (political, educational and social, in local, national and global levels), in a continuous never-ending fashion. Having this theoretical framework as a backdrop, this article analyses philosophy as public policy for high school in Brazil in the last couple of decades, with special attention to the interactional between the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines (Ocem), published in 2006, and the Brazilian National High School Exam (Enem).

Despite the stipulation present in the Law of Guidelines and Foundations (LDB) that the “contents, methodologies and forms of assessment be organized in such a way that at the end of high school the student demonstrate [...] mastery of the knowledge of Philosophy and Sociology necessary to the exercise of citizenship” (BRASIL, 1996, art. 36), in the almost twenty five years since the publication of LDB in 1996, the introduction of philosophy in Brazilian high schools has not been neither linear nor guaranteed, be it in the legislation, in curriculum documents, (ALVES, 2002; GALLO, 2013) or in large scale assessment, the Enem in particular (MACEDO, 2015, 2021a, 2021b).

On the one hand, the curriculum documents published in the first ten years since the publication of LDB resonate and bring more detail to the stipulated in article 36 regarding the offering of philosophy in high school. This is the case, for instance, of the Resolution number 3 of the National Council of Education/Chamber of Basic Education (CEB/CNE), published on 26 June 1998, that establishes National Curriculum Guidelines for High School, in turn detailed by the Decision CEB/CNE nº 15, approved on 1 June 1998. It is also the case with later documents, which bring specific chapters for each curricular component, including philosophy. There belong to this group: the National Curricular Parametres (PCNs), published in 1999; the Complementary Educational Guidelines to the National Curricular Parametres (PCN+), published in 2002; and the National Curriculum Guidelines (Ocem), published in 2006. The valorization of high school philosophy in this period follows international initiatives promoted by UNESCO (DROIT, 1995; JOPLIN, 2000; UNESCO, 2005, 2007; MCDONOUGH; BOYD, 2009).

In Brazil, only after the publication of Law nº 11.684/08, which altered the article 36 of the LDB so as to make philosophy and sociology mandatory in high school, and the publication of the 2012 National Curricular Directives for High School (CNE Resolution nº 02/12), that philosophy started appearing in a more consistent manner in the National High School Exam (MACEDO, 2015). However, this law was revoked eight years after its publication by the Provisional Measure nº 746, issued on 22 September 2016, which altered LDB once again to introduced the so-called “New High School”. This Provisional Measure, in turn, when converted into Law number nº 13.415, issued on 16 February 2017, reinstated the mandatory status of philosophy (art. 35, paragraph nº 2), after protest of various sectors of civil society.

The 2018 National Curricular Directives for High School (CNE Resolution nº 03/18), and the National Curriculum Common Core (BNCC), published on 04 December 2018, reaffirm the mandatory status of philosophy in the Brazilian high school system. the BNCC presents philosophy as belonging to the area of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences (BRASIL, 2018b, p. 547). The CNE Resolution nº 03/2018, in turn, establishes that “the matrices of the National High School Exam (Enem) and other selective processes for higher education admission must necessarily be elaborated in accordance to the National Curriculum Common Core (BNCC)” (BRASIL, 2018a, article 32). Thus, given the publication of the BNCC, an important question is the discussion of how this document with be “implemented”, in particular as regards the Enem, and especially the presence of philosophy in the exam.

In this sense, it is fruitful to examine previous experience. Among the curricular documents produced since the publication of the LDB, the Ocem were selected for the present study for a few reasons. This article is part of a wider study of the presence of philosophy in the Enem and its relations with the curriculum documents published since the beginning of the exam, and this particular article is the part that examines the Ocem more specifically. This document deserves a dedicated examination for other reasons. First, although other curricular documents were published afterwards, the Ocem are still the most recent official documents in Brazil among those which devote a specific chapter to high school philosophy, thus allowing for a more detailed analysis of the expectations for the area at this stage of learning.

Furthermore, although the Ocem do not have normative value over Enem, they propose contents for high school, so that it would be reasonable to expect a certain level of convergence between the two instruments, even when allowing for gaps arising from the fact they were created independently of each other. As the Ocem themselves state: “in order that the student may develop the skills expected by the end of high school, there must not be a separation between content, methodology and forms of assessment” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 36). However, not only did it take a few years for the Ocem to start to reflect on the Enem, but even today, over twelve years later, there are gaps in the articulation between the two instruments, and these gaps go both ways: both in terms of Ocem philosophy contents which have not appeared on the exam as well as questions on exam that do not correspond to any of the philosophy topics recommended by the Ocem.

The discrepancies between the Ocem and the Enem in the area of philosophy reveal limitations of both as regards this field of knowledge, as well as a conceptual mismatch between curriculum document and large scale assessment. The reservations that the Ocem expresses in relationship to its precedents in the lineage of curriculum documents, on the hand, as well as well its origin in the 2005 National University Student Exams (Enade), on the other, constitute good examples of how educational policies are interrelated, influencing and conflicting with each other, as theorized by Ball and Bowe (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE; BALL; GOLD, 1992; BALL, 1998; MAINARDES, 2006).

This article presents an analysis of the Humanities questions in Enem between 1998 and 2018 in terms of the philosophy contents recommended by the Ocem. It is divided in three parts. In the first part, I present a quantitative panorama of the coverage of the philosophy contents recommended by Ocem throughout twenty years of Enem, identifying the gaps that still persist. In the second part, I examine some of the reasons that give rise to these gaps, in particular the differences in the origins and purposes of these two instruments, which in turn reveal conceptual discrepancies as regards to what is expected of pre-college education and the role of philosophy in it. In the third part, I present a qualitative analysis of how these conceptual discrepancies between Ocem and Enem translate in how philosophy appears in the exam throughout the years. In conclusion, I present some points of reflection about the prospects and challenges that the new BNCC posit as regards the gaps identified in the body of this article and the continuing presence of philosophy in the exam in this new scenario.

Quantitative Analysis

Following Ball and Bowe (1992), one of the theses supported by this article is that curriculum documents do not translate immediately nor necessarily into practice, be it in schools or large scale assessment. In this sense, it is symptomatic that the first question dealing with philosophy in the Enem after the publication of the Ocem appeared only three years later, in 2009, the year that the exam was reformulated. In the five years after that, the exam brought only eight questions dealing with philosophy: there was only one philosophy question in the exam in 2009; in 2010, there were six; and in 2011 there was once again only one question related to the area, and superficially at that (MACEDO, 2015).

Part of the reason why it took a long time for philosophy to appear in the exam can be traced to the fact that it only became mandatory in the Brazilian high school system in 2008. Thus, even in the original version of the exam, from 1998, philosophy was not very present in Enem. In fact, in the seven years between the publication of the PCN+ in 2002, for example, and the reformulation of the exam in 2009, there was only one question associated with philosophy in the exam, in 2003 (MACEDO, 2015).

Only after 2012 can one notice a more consistent presence of philosophy in the exam. From this year on, the number of philosophy questions stabilizes between six and eight each year, and the themes become more diverse (MACEDO, 2021a, 2021b). Beyond the quantitative issue, therefore, there are also qualitative improvements, encompassing a greater diversity of themes and approaches characteristic to philosophy, mobilizing at the same time a greater range of abilities and skills of the Humanities matrix of the exam itself. From the point of view of sources used, there was a perceptible effort to increase the number of texts from the western philosophy canon and to characterize a philosophical approach, which is significant, not simply to return to the classics for the mere fact that they are classic, but also to demarcate an area never fully incorporated in high school (MACEDO, 2015).

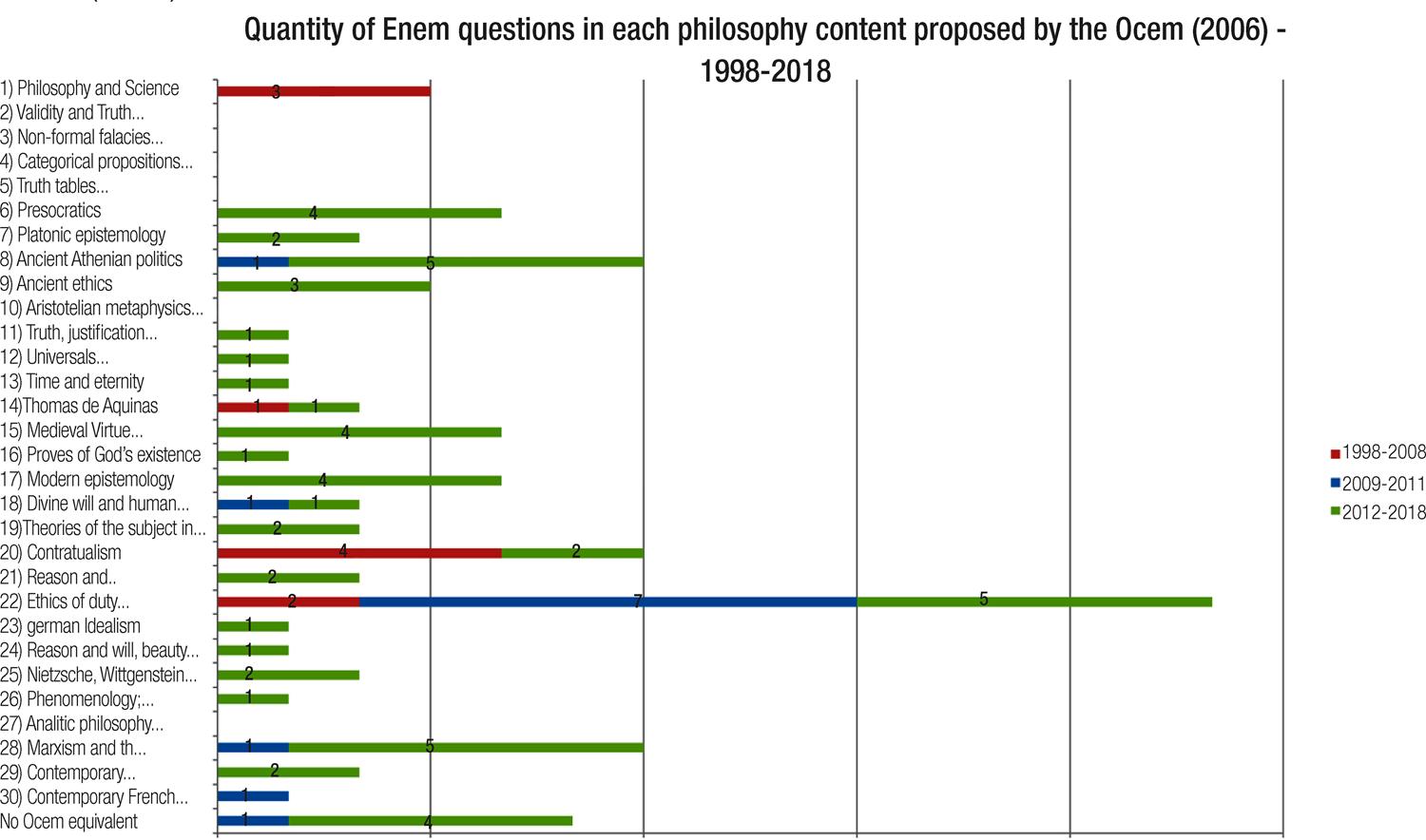

According to previous survey (MACEDO, 2021b, in press), the 70 philosophy questions administered in the exam between 1998 and 2018 cover 22 of the 30 contents the Ocem propose for high school philosophy, as shown in the following illustration:

Source: (MACEDO, 2021b, in press).

Figure 1 – Quantity of Humanities questions in the Enem in each philosophy content proposed by the Ocem (2006) - 1998-2018

As illustrated above, throughout the history of the exam covered in this study (1998-2018), the Ocem content that was demanded the most, by far, was content 22, about ethics, with twelve questions from 2009 onwards, plus two questions with compatible themes in the years preceding the Ocem and the new matrix of the exam. In second place, with six questions each, were content 8, “ancient Athenian politics” and content 28, “marxism and Frankfurt school”, all administered after 2009. Therefore, the three Ocem contents most demanded on the Enem involve issues related to citizenship, in the scope of political philosophy and ethics, in a total of twenty-six questions.

On the other hand, six out of the thirty philosophy contents proposed by the Ocem remain uncovered in the Enem in the twelve years since the Ocem were published and the 2018 edition of the exam (MACEDO, 2021b). They are the following:

2) validity and truth; proposition and argument;

3) non-formal fallacies; recognition of arguments; content and form;

4) chart of opposition between categorical propositions; immediate inferences in categorical context; existential content and categorical propositions;

5) truth tables; propositional operations;

10) central concepts in Aristotelian metaphysics; Aristotelian theory of science; and

27) analytical philosophy; Frege, Russell and Wittgenstein; the Vienna Circle.

This discrepancy brings some questions: how can this gap between curriculum document and large scale assessment be explained? Can this gap be bridged or mitigated in the transition between the new BNCC and the new Enem?

As argued above, part of the reason why it took so long for philosophy to start to appear in the exam is not a flaw of the documents themselves, but due to other contextual factors, such as the fact that philosophy did not become a mandatory subject in Brazilian high schools until 2008, as well as the fact that public policy need time to mature and produce effects. Nevertheless, after twelve years one would expect more convergence between these two instruments of public policy about high school education. However, as I argue in the next part, the gaps between Ocem and Enem are not only temporal, but also conceptual, arising from their different origins and purposes. In the next sections, I explore these aspects in more depth.

Back to the origins

Curriculum documents do not appear in a vacuum, nor are they “implemented” in an automatic fashion, as if by fiat, but are part of cyclical, contingent and intricately entangled processes, in which assessment has gained increased importance in the last few years (BALL; BOWE, 1992; BOWE; BALL; GOLD, 1992). For the sake of the argument, a common and simplified way of visualizing the interaction between curriculum documents and large scale assessment is what became known as the PDCA cycle: Plan, Do, Check, Act (DEMING, 1982). In this model, curriculum documents would correspond to the first stage (Plan); their “implementation” in schools would correspond to the second stage (Do); assessment, and Enem would enter here, would correspond to the third stage (Check), generating information so a new PDCA policy cycle could start.2 According to this model, the different curriculum documents written since the LDB could be considered as part of a lineage of documents which was cyclically transformed as years went by, not only influencing the exam, but also being influenced by it.

To consider that curriculum documents is neither “generated” nor “implemented” in a vacuum is to consider, on the one hand, on the influences that they exert on one another as part of a web of educational policies for high school philosophy, sometimes complementing each other, sometimes contradicting each other. What Ball and Bowe detect in terms of educational policy texts in general applies strongly to policies regarding high school philosophy in particular, their respective key terms and representations of policy:

But two key points have to be made about these ensembles of texts which represent policy. First, the ensembles and the individual texts are not necessarily internally coherent of clear. The expression of policy is fraught with the possibility of misunderstanding, texts are generalized, written in relation to idealizations of the ‘real world’, and can never be exhaustive, they cannot cover all eventualities. The texts can often be contradictory (compare National Curriculum statutory guidance with NCC produced Non-Statutory Guidance), they use key terms differently, and they are reactive as well as expository (that is to say, the representation of policy changes in the light of events and circumstances and feedback from arenas of practice). Policy is not done and finished at the legislative moment, it evolves in and through the texts that represent it, texts have to be read in relation to the time and the particular site of their production. They also have to be read in relation to the time and the particular site of their production. They also have to be read with and against one another – intertextuality is important. Second, the texts themselves are the outcome of struggle and compromise. The control of the representation of policy is problematic. Control over the timing of the publication of the texts is important. (…) Groups of actors working within different sites of text production are in competition for control of the representation of policy. (BOWE et al., 1992, p. 21).

Although they claim to give continuity to previous curricular documents, such as the PCNs and PCN+ (BRASIL, 2006, p. 8), in relation to these documents the Ocem bring, as Silvio Gallo argues, “perspectives which are distinct and at times irreconcilable” (GALLO, 2013, p. 426). Despite the centrality that Ocem attribute to the formation of the philosophy teacher in the chapter devoted to the subject, for the professional in the area, whether they be in it in the classroom, in the university, in the different spheres of the public and private sector, the transition between these documents demand a lot of effort to be seen as minimally complementary and to redirect their practice in other to maintain coherence with the documents as well as with their own professional formation. By analyzing the the Ocem as part of a web of educational policies for high school, of which the Enem and the BNCC are also part, the present study aims to contribute towards strengthening this web by taking highlighting points of continuity and points of tension between the preexisting nodes of this web.

Thus, a model such as Deming´s ubiquitous PDCA´s cycle can be considered a simplification for many reasons, among them the fact that no public policy is in isolation of other policies, or of people that act as writers and readers of these policies. Beyond the influences that Enem and afterwards the BNCC receive from their lineage of educational policies for high school, other influences must also be taken into consideration. This entails also taking into account the influences that these instruments receive from other educational policies, even if not specifically related to philosophy or to high school.

As each policy in theory would have their own PDCA cycle, with their various actors, political timing and areas of impact, the degree of influence they exert on one another undergo variations and interferences over time. Ball and Bowe´s policy cycle is therefore a more adequate theoretical model, among other reasons, for the emphasis they give to the various interactions, tensions and influences which different actors and policies exert on one another. They are like the different gravitational influences that different celestial bodies of different magnitudes and orbits exert on one another. As summarized by Mainardes:

These contexts are interrelated, do not have a temporal or sequential dimension, and are not linear stages. Each of these contexts represent arenas, places and interest groups and each of them involve disputes and struggles. (BOWE et al., 1992 apudMAINARDES, 2006, p. 50).

The comparison between the philosophy component of the Ocem with the coverage of philosophical themes in the Humanities section of Enem proves to be an interesting case study to reflect upon high school philosophy, because it provides a strong example of how curriculum policies are the result of processes that are ever-returning, messy and interdependent, and in which evaluation plays a crescent role. For example, the very text of the philosophy chapter of the Ocem describe in an explicit manner how its starting point and process of production derived from another evaluation process, namely, Enade (exam for senior university students):

The process of writing of this document coincided with a new institutional scenario for philosophy as a field of study. First, the undergraduate degrees in philosophy started to be subjected to institutional evaluation, with the nomination of a committee to elaborate the criteria for the future elaboration of the tests for the 2005 Enade in the area of philosophy. The works of the committee certainly contributed to the discussion about the composition of the area as a high school subject, in as much as it stated some positions regarding the undergraduate degree and the skills expected of the professional graduated with a teaching degree in philosophy. (BRASIL, 2006, p. 19)3.

The relationship between Ocem and the 2005 Enade illustrate how different policy cycles, in their various stages, intersect and influence one another. In this case, beyond exerting its primary assessment function within the policy cycle geared towards monitoring the quality of higher education, Enade also functions as a subsidy in the elaboration of curricular guidelines in another educational arena, namely, high school. The PDCA cycle that would in theory would begin with P) legal document (Ocem); D) implementation (philosophy taught in high schools) and C) assessment (Enem) is not only chronologically preceded, but also substantially influenced by the instrument of assessment of another cycle of public policy.

On the other hand, the current matrix of Enem, adopted in 2009, has its origin in the National Exam for Skill Certification for Young People and Adults (Encceja) (BRASIL, 2014, p. 7). Therefore, while the Ocem philosophy component, with its origin in Enade, has a more academic proposition, the Enem matrix, with its origin in Encceja, goes in the opposite direction. Because it inherits many characteristics from Encceja, which in turn aims at measuring skills from experience obtained outside of the school and university setting, the humanities matrix of Enem4 ends up not offering much space for philosophy questions (GALLO, 2013; MACEDO, 2021a).

In turn, the authors of the philosophy component of Ocem repeatedly emphasize notions such as the centrality of the History of Philosophy as “touching stone” (p. 31, p. 32); the “primacy of philosophical text” (p. 17, p. 37), which is the legacy of philosophy, “in content and in form” (p. 32); the need of appealing to “philosophical tradition” (p. 32); the “importance of an exegetic technique” (p. 32); the specificity of philosophy´s contribution to argumentation and reading (p. 30); having many reservations as regards any mention of the legislation and other documents with respect to basic education as preparation for the work (BRASIL, 2006, p. 19, p. 26, p. 29).

This relationship between Enem and Encceja, on the one hand, and Ocem and Enade, on the other, illustrate how different policy cycles, in their different stages, far from being linear, intersect, influence and contradict one another Beyond their different origins and purposes and lack of an articulate proposition between Ocem and Enem, there is also a conceptual gap between these two instruments. This gap involves key concepts such as ethics and citizenship; skills and abilities for work; and expectations regarding basic education in general and philosophy in particular and how it relates to the development of these characteristics in high school graduates or in what is expected of adults even if they have not finished school.

In the next section, I explore the tense relationship that the philosophy component of Ocem has with the lineage of curriculum documents which precede it, starting from LDB, as well as how these tensions contrast with the way philosophy has appeared in the Enem throughout the years.

Qualitative analysis

Among the criticisms that the authors of the philosophy component of the Ocem present towards the previous curriculum documents, in particular the PCNs, are their supposed ambiguity, on the one hand, and unilaterality, on the other:

The current PCNs for the subject, like the preceding ones, suffer from the ambiguity They intended to cure and often oscillate between enunciating too little or too much. Thus, side by side with an excessive caution, we can find steps that are excessively doctrinarian, which end up robbing philosophy of one of its richest aspects, namely, the multiplicity of perspectives, which must not be reduced to a unilateral voice. It was deemed necessary, therefore, to present a reformulation in such a way as to avoid doctrinarian impositions, even when resulting from the best intentions. (BRASIL, 2006, p. 18).

However, the Ocem themselves are not immune to these same problems. As regards the section dedicated to philosophy, the Ocem are ambiguous, not only in relation to the previous curriculum documents, such as the PCNs and the LDB itself, (p. 26, p. 28), but also because they are internally contradictory: concerning the concept of citizenship (p. 15, p. 18, p. 19), of skill (p. 19, p. 29, p. 30), and even concerning ambiguity itself (p. 16, p. 21). Concerning the notion of skill, for instance, the Ocem on the one hand see their importance over contents (p. 29). At the same time, they see the notion of skill with suspicion (p. 19, p. 29, p. 30) and end up proposing contents (p. 34), as illustrated in the first part of this article.

With respect to the notion of citizenship, although the humanities component mentions concepts such as politics, inclusion, dialogue, participative management, these elements are absent from the philosophy contents proposed in the document. To the authors of the philosophy component of the Ocem, to educate for citizenship is “a challenge” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 15, p. 24). In a brief overview of how this concept appears in the previous documents, the authors show reluctance about admitting ethics and citizenship as part of the scope of philosophical training, considering them as part of general education, and not of philosophy specifically (p. 25): “Given that it is possible to form citizens without the formal contribution of philosophy, it would certainly be a mistake to think that this role belonged to philosophy exclusively” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 26). This specific role of philosophy, according to the Ocem, is the argumentative skill— reading, language, logic:

The question here is: what is the specific contribution of Philosophy concerning the exercise of citizenship in this stage of schooling? The answer to this question highlights the peculiar role that philosophy plays in the general skill of speech, reading and writing – skill here understood in a very special manner, related to Philosophy´s argumentative nature and its historic tradition. Therefore, it belongs to Philosophy specifically the capacity of analysis, of rational reconstruction and of criticism, from the understanding that taking a stand towards proposed texts of any kind (whether philosophical or non-philosophical and discursive formations not explicit in texts) and issuing opinions about them is an indispensable prerequisite for the exercise of citizenship. (BRASIL, 2006, p. 26).

Therefore, although recognizing the centrality of ethical and political issues in everyday life5, concerning philosophical training in ethics and politics, the Ocem bring an explicit rejection:

[The] mere allusion to ethical questions is not ethics, no is political philosophy there mere mention of political questions, not being the desire of forming citizens enough for a philosophical reading, once that neither are critical thinking or preoccupation with the destiny of humanity exclusive prerogatives of Philosophy. (BRASIL, 2006, p. 18).

This reflection translates later in the recommended contents and reveal important gaps in the Ocem, especially in the field of political philosophy and ethics.6 Only two contents are dedicated to ethics: content 9) “ancient ethics; Plato, Aristotle and Helenistic philosophers;” and content 22) “ethics of duty; fundaments of morals; autonomy of the subject”. Political philosophy in turn finds space in four contents: 8) “ancient politics; Plato´s Republic; Aristotle´s Politics”; 20) “contratualism”; 28) “Marxism and Frankfurt School”; and 30) “contemporary French philosophy/ Foucault/ Deleuze”.

With respect to the coverage of Ocem philosophy contents in the Humanities section of Enem, the lack of suggestions on the part of the Ocem in the field of ethics explains in part the abundance of questions on the exam having as closest point of contact Ocem´s content 22, which becomes a generic umbrella for all ethics questions outside of the scope of ancient philosophy. Concerning political philosophy, this gap involves not only the entire discussion concerning democracy in modern and contemporary philosophy, but also questions regarding political philosophy outside antiquity.

Therefore, a question such as number 457 in the 2010 edition of the exam, that used a comic by Argentinian artist Quino to introduce the question of democracy and despotism find no place in the Ocem (MACEDO, 2015). There is also no space in the Ocem for questions such as number 17 in the 2015 edition, which brough a fragment by Thomas Aquinas about monarchy. In virtue of the absence of suggestions in the area of political philosophy, it is difficult to think which Ocem content would allow space for this type of question. Silvio Ricardo Gomes Carneiro, in his article “O Enem e a leitura de textos filosóficos: análise de alguns parâmetros para a sala de aula” (“Enem and the reading of philosophy texts: analysis of some parameters for highschool”) (2015), for example, considers that this question corresponds to content 18, “divine will and human freedom”, although there is not any mention to the question of the divine in the fragment presented. Because the question deals with human action and common good, central in ethics, in this study the Ocem content which was considered most appropriate for this type of question was the recurrent content 22. More recently, in the 2018 edition of the exam, another question which does not find correspondence with the Ocem conception was question 90, which brings a text by Nobert Bobbio about Hans Kelsen´s view of the individualistic character of contemporary democracies.

As examples of philosophy questions more aligned with the Ocem proposal is question 52 of the same year, which invites the student to compare the thoughts of Hobbes and Rousseau. This question corresponds to content 20 of Ocem, “contratualism”. In the 2017 edition, question 84, about Habermas, as it had done previously, in the 2012 edition, would correspond to content 28) “marxism e Escola de Frankfurt”, in the lack of a more adequate correspondence. Question 64, in turn, that invites the student to associate the thought of John Rawls to modern liberalism, does not fit with the Ocem proposal so easily. The content that would perhaps allow this type of exercise would be content 20, “contratualism”, because of its relation to liberalism.

In addition to these examples, there are other questions on political philosophy in Enem which relate to the Ocem only tangentially. For example, question 7 in the 2012 test, about Montesquieu´s vision on political liberty. Montesquieu is a central author in political philosophy, having a subtheme of his own in the previous curriculum, the PCN+, under theme I.2, “contemporary democracy”. In the Ocem, other hand, it is difficult to see which content would cover this author´s contribution. Carneiro (2015), for example, considers that none of the Ocem contents applies to this question. For the purposes of this study, because of the theoretical current of the author and the theme explored in the question, it corresponds to content 20, “contratualism”. Question 09 on the same test, about Habermas, would be a question about “democracy” if there were such a content, but in the lack thereof, it was considered in this study as corresponding to content 28, “Marxism and the Frankfurt School”.

Concerning content 22, “ethics of duty, fundaments of morals, autonomy of the subject”, of all the twelve questions on Enem between 2006 and 2018 that relate to this content in any way, the ones which do so most adequately are question 2 of the 2012 edition, about the concept of coming of age in Kant, and question 85 in the 2017 edition, about the categorical imperative. Other questions about the modern and contemporary periods that deal with aspects of ethics or autonomy find in this content the closest correspondence in the Ocem, even though they are not a perfect fit. This content ends up being the closest correspondence to questions such as number 10 in the 2013 edition about human motivations in Machiavelli; question 3 in 2017 about the role of autonomous thinking in Paulo Freire´s philosophy and question 48 in the same test about Bentham´s utilitarianism.

Thus, despite the efforts of the authors of the Ocem´s philosophy component to distance high school philosophy from issues about ethics, politics and citizenship (BRASIL, 2006, p. 18, p. 19, p. 24, p. 32), these exam questions deal with themes that are central to philosophy and in ways that, arguably, are relevant to high school students. In addition, far from materializing the Ocem´s concern about indoctrination or “naive demand of univocity” (p. 21), these questions prove to be varied enough to satisfy the Ocem´s own requirement concerning the multiplicity of perspectives.

To conclude this article, in the next section I present some prospects and challenges that the new BNCC present to philosophy in Enem, taking into consideration the questions raised in the body of this paper.

Conclusion

This article identified some limitations and gaps between the Ocem and the Enem in the area of philosophy. I argued that, although many of these limitations and gaps are internal to each of these instruments, much of the discrepancy between the two is due to a lack of articulation between them. This lack of articulation is due, in part, to their different origins and purposes, and, in part, to the dynamics that Stephen Ball and Richard Bowe call policy cycle.

But what contribution can an analysis such as this, about the correspondence of philosophy questions in Enem to the Ocem bring to the reflection about the spaces dedicated to philosophy in the new BNCC and the perspectives for the area in this new scenario?

As part of the lineage of curriculum documents of which the BNCC too is part, an analysis of the Ocem contributes as a benchmark to evaluate advancements and points of attention, both internal to how each of these instruments approach philosophy, and as well as the articulation between them as educational policies for high school.

To exclude from the high school curriculum issues of ethics and citizenship, as the Ocem do, is to reserve this type of discussion to an extremely restrict group, consisting in people that: 1) have successfully finished high school; 2) have secured a place in university; and 3) have chosen to study philosophy. But from the moment that philosophy becomes mandatory in high school, as it is now after the BNCC and the high school reform, with its emphasis on youth protagonism (cf. BRASIL, 2018b, p. 465, p. 468, p. 471-472, p. 478-479, p. 562), nothing more fitting than that issues about choice, autonomy and forms of political organization be also debated by those in the centre of this policy. By minimizing the importance of issues of ethics and citizenship in high school philosophy, this type of policy also rejects the opportunity of expanding this debate precisely with the people most involved in pre-college education, namely, high school students and teachers (BANDMAN, 1982; GEHRETT, 2000; PINTO; McDONOUGH; BOYD, 2009; BALL, BOWE & GOULD, 1992; SILVA, 2020; SÜSSEKIND; MASKE, 2020).

Fortunately, when compared to the Ocem, the new BNCC offers more space for philosophy themes, especially in the areas of ethics and of political philosophy. Ethics finds a special place in skill 5: “To identify and to fight the various forms of injustice, prejudice and violence, adopting ethical, democratic, inclusive and empathic principles, and respecting Human Rights.” The themes related to political philosophy, in turn, find a place in skill 6: “To participate in the public debate in a critical manner, respecting different positions and making choices aligned to the exercise of citizenship and their own life project, with liberty, autonomy, critical consciousness and responsibility.

The abilities proposed for each of these skills provide margin to expand the space for ethics and political philosophy, which in Enem´s current humanities matrix have been represented by ability H12, “To analyse the role of justice as an institution in the organization of societies”; H23, “To analyse the importance of ethical values in the political structure of societies”, H24, “To identify the relationship between citizenship and democracy in the organization of societies” and H25, “To identify strategies which promote forms of social inclusion”. Here it is possible to identify a closer conceptual alignment between Enem and BNCC than there is between the exam and the Ocem. This correspondence reflects another point raised in this study, namely, the issue of the origins and objectives of each of these instruments of educational policy.

The proximity between BNCC and Enem can be traced back to their respective origins, in two ways. On the one hand, while the Ocem do not mention the Enem, and do not have a normative character over the curricular strategies adopted by schools, the BNCC is published together with the CNE resolution that “the matrices of the National High School Exam must necessarily be elaborated in consonance with the National Common Core (BNCC)” (CNE Resolution nº 03/2018). Furthermore, as I argue elsewhere (MACEDO, 2021a, in print), many of the abilities proposed for the humanities in the BNCC are close in content and in form to the abilities of the Enem´s humanities´ matrix, which reinforce that thesis that not do curriculum documents influence the exam, but they are also influenced by it.

On the one hand, this convergence between Enem and BNCC from the beginning can contribute to minimize the gaps between these two instruments, whether temporal or conceptual. On the other hand, the analysis presented here identifies some points worthy of attention, both internally to the area of philosophy in this new context, as well as in relationship to the articulation between curricular document and large scale assessment more generally.

Identifying the points of contact between Ocem and Enem help to find gaps not only on the part of the Ocem, but also of Enem and BNCC. As mentioned above, six of the thirty philosophy contents the Ocem suggests for high school philosophy remained uncovered by Enem until 2018 (contents 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 27). In broad terms, all of these contents have some relation with Aristotelian logic and proximity with mathematics. In this respect, the Ocem follow the 2005 Curricular Guidelines for Undergraduate Courses in Philosophy, which list logic as one of the five great areas of philosophy.8 This is an important addition of the Ocem to the PCN and PCN+, not fully incorporated by Enem. The situation as regards the BNCC is not much more conducive to these contents, having as closest points of contact abilities EM13CHS101 and EM13CHS103 (cf. MACEDO, 2021b).

Evidently, the issue of whether logic, analytic philosophy or Aristotelian philosophy of science belong in high school or not is far from consensus, which is one of the many reasons why debate with various sectors of society is so necessary. Defending and prescribing philosophical training of any kind for young people in high school should be accompanied by an expansion and strengthening of the intersection between philosophy, education and public policy. It requires discussions of many types: philosophical, epistemological, ethical, political, with people in various arenas and various kinds of background and training in each of those arenas. This opens an entire range of issues central to philosophy, concerning the type of education, knowledge and society we expect not only from young people, but also from us, citizens and participants of the various arenas of society. (MARTIN, 1981a, 1981b, 1985a, 1985/2001; McCOLL, 1994; MILLS, 1998; SIEGEL, 2008; YOUNG, 1990, 2002; POPKEWITZ, 2020).

According to Ball and Bowe, these interactions are crucial and are Always active, with a greater or lesser degree of cohesion, in one point or another of the entangling of micro and macro arenas that make up public policy and society as whole. However, as educational policies have cycles of various durations, there are some turning points in which this type of interaction between various sectors of society is particularly crucial. The present moment is one of those.

Although it is a truism to say that there is no way to make up for lost time, it is important to highlight that school years are particularly irrecoverable. The school year and the school years are very sensitive in terms of opportunities, expectations and choices. If someone were to start elementary school in Brazil in the year that the Ocem were published in 2006, and had a successful trajectory throughout, she would finish high school in 2018, they year the BNCC was published, which in turn was predicated in the 1988 Constitution and took thirty years to materialize (see also ALVES, 2002).

As illustrated, although far from exempt from its own gaps and limitations, as regards high school philosophy the new BNCC offers some possibilities, especially if compared with previous curriculum documents, such as the Ocem. Even comparing to the Enem matrix, with which it has many points of contact, the new BNCC brings some interesting improvements. If, however, there is not more space for reflection and debates concerning how the BNCC will translate into large scale assessments, especially in Enem, it is uncertain how this philosophical potential will flourish in this new context, despite the reinstatement of philosophy as a mandatory high school subject. The situation is more worrisome as regards the gaps, both those presented here as well as the various others that exist. Unless there is a real effort of interaction and debate between various arenas (academic, educational, philosophical, pedagogical, political and administrative) to think about these issues, such gaps will become uncovered until the next curriculum document comes along. Judging from previous documents, it may well take over a decade, which in educational terms is the equivalent of an entire generation of citizens.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Dalton José. A Filosofia no ensino médio: ambiguidade e contradições na LDB. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2002. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen J. Big policies/small world: an introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comparative Education, Abingdon, v. 34, n. 2, p. 119-130, 1998. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen J.; BOWE, Richard. Subject departments and the ‘implementation’ of national curriculum policy: an overview of the issues. Journal of Curriculum Studies, London, v. 24, n. 2, p. 97-115, 1992. [ Links ]

BANDMAN, Bertram. The adolescent’s rights to freedom, care and enlightenment. Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children, Montclair, v. 4, n. 1, p. 22-27, 1982. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, David. Philosophy in high school: what does it all mean? Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children, Montclair, v. 8, n.4, p. 43-44, 1990. [ Links ]

BOWE, Richard; BALL, Stephen J.; GOLD, Anne. Reforming education & changing schools: case studies in policy sociology. London: Routledge, 1992. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Lei de diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 23 dez. 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.415, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 16 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Parecer CNE/CEB 15/1998. Brasília, DF: CNE, 1998. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/Par1598.pdf. Acesso em: 30 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Resolução CNE/CEB 3/2018. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, Seção 1, p. 21-24, 22 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais (INEP). Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (Enem): relatório pedagógico 2009-2010. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais (INEP). Matrizes de referências do Enem. v. 4. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação (MEC). Base Nacional Comum Curricular para o Ensino Médio. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação (MEC). Orientações curriculares nacionais para o ensino médio: ciências humanas e suas tecnologias. v. 3. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2006. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação (MEC). Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução CNE nº 03, de 04 de dezembro de 2018. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação (MEC). Secretaria de Educação Média e Tecnológica (SEMTEC). Orientações educacionais complementares aos Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais. Brasília, DF: SEMTEC/MEC, 2002. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação (MEC). Secretaria de Educação Média e Tecnológica (SEMTEC). Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Brasília, DF: SEMTEC/MEC, 1999. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, Silvio Ricardo Gomes. O Enem e a leitura de textos filosóficos: análise de alguns parâmetros para a sala de aula. Revista do NESEF Filosofia e Ensino, Curitiba, v 6, n. 6, p. 26-42, jun./dez. 2015. [ Links ]

DEMING, William Edwards. Out of the crisis. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982. [ Links ]

DROIT, Roger-Pol. Philosophy and democracy in the world. Paris: Unesco, 1995. [ Links ]

GALLO, Sílvio. Filosofia e Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio: desafios e perspectivas da avaliação. In: AVALIAÇÕES da educação básica em debate: ensino e matrizes de referências das avaliações em larga escala. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2013. p. 413-429. [ Links ]

GARRET, Leroy. 10 years in high school philosophy. Educational Theory, Champaign, v. 17, n. 3, p. 241-247, 1967. [ Links ]

GEHRETT, Christine. Doing philosophy in high school: one teacher’s account. Inquiry, Huntsville, v. 19, n. 2, p. 27-35, 2000. [ Links ]

HEGEL, Georg. On teaching philosophy in the gymnasium. Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children, Montclair, v. 2, n. 2, p. 30-33, 1822/1980. [ Links ]

JANNUZZI, Paulo de Martino. Indicadores para diagnóstico, monitoramento e avaliação de programas sociais no Brasil. Revista do Serviço Público, Brasília, DF, v. 56, n. 2, p. 137-160, 2005. [ Links ]

JOPLIN, David. “The coolest subject on the planet”: how philosophy made its way in Ontario’s high school”. Analytic Teaching, La Crosse, v. 21, n. 2, p. 131-139, 2000. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Ester Pereira Neves. Debater para encontrar caminhos: a evolução da presença da filosofia ao longo dos vinte anos do Enem (1998-2018). Pro-Posições, Campinas, 2021a (no prelo). [ Links ]

MACEDO, Ester Pereira Neves. Filosofia no Enem: um estudo analítico dos conteúdos relativos à filosofia ao longo das edições do Enem entre 1998 e 2011. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2015. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Ester Pereira Neves. Filosofia no Enem: 2012-2018. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2021b (no prelo). [ Links ]

MACEDO, Ester Pereira Neves. Philosophy of the many: high school philosophy and a politics of difference. 2011. 154 f. PhD Thesis (Doctor of Philosophy) – Graduate Department of Theory and Policy Studies, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. University of Toronto, Toronto, 2011. [ Links ]

MAINARDES, Jefferson. Abordagem do ciclo de políticas: uma contribuição para a análise de políticas educacionais. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 27, n. 94, p. 47-69, jan./abr. 2006. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Jane Roland. Becoming educated: a journey of alienation or integration? In: HARE, William; PORTELLI, John Peter (ed.). Philosophy of education: introductory readings. 3. ed. Calgary; Alberta: Detselig Enterprises, 1985/2001. p. 69-82. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Jane Roland. Needed: a new paradigm for liberal education. In: SOLTIS, Jonas (ed.). Philosophy and education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981b. p. 37-59. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Jane Roland. Reclaiming a conversation: the ideal of the educated woman. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Jane Roland. The ideal of the educated person. Educational Theory, Champaing, v. 31, n. 2, 97-110, 1981a. [ Links ]

McCOLL, San. Opening philosophy. Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children, Montclair, v. 11, n. 3-4, p. 5-9, 1994. [ Links ]

McDONOUGH, Graham; BOYD, Dwight. Socrates seen in Ontario high schools (and he has not left the building!). Journal of Teaching and Learning, Richmond Hill, v. 6, n. 1, p. 55-67, 2009. [ Links ]

MILLS, Charles W. Alternative epistemologies. In: ALCOFF, Linda Martin (ed.). Epistemology: the big questions. Malden: Blackwell, 1998. p. 392-410. [ Links ]

MOORE, Willis. Philosophy in curriculum of high school: purpose and plan of this issue. Educational Theory, Champaign, v. 17, n. 3, p. 203-204, 1967. [ Links ]

PINTO, Laura Elizabeth; McDONOUGH, Graham; BOYD, Dwight. What would Socrates do? An exploratory study of methods, materials and pedagogies in high school philosophy. Journal of Teaching and Learning, Richmond Hill, v. 6, n. 1, p. 69-82, 2009. [ Links ]

POPKEWITZ, Thomas. Estudos curriculares, história do currículo e teoria curricular: a razão da razão. Em Aberto, Brasília, DF. v. 33, n. 107, p. 47-66. jan./abr. 2020. [ Links ]

SIEGEL, Harvey. Why teach epistemology in schools. In: HAND, Michel; WINSTANLEY, Carrie (ed.). Philosophy in schools. New York: Continuum International, 2008. p. 78-84. [ Links ]

SILVA, Francisco Thiago. O nacional e o comum no ensino médio: autonomia docente na organização do trabalho pedagógico. Em Aberto, Brasília, DF. v. 33, n. 107, p. 155-172. jan./abr. 2020. [ Links ]

SÜSSEKIND, Maria Luiza; MASKE, Jeferson. “Pendurando roupas nos varais”: Base Nacional Comum Curricular, trabalho docente e qualidade. Em Aberto, Brasília, DF. v. 33, n. 107, p. 155-172. jan./abr. 2020. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Intersectorial strategy for philosophy. Paris: Unesco, 2005. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Philosophy: a school of freedom. Paris: Unesco, 2007. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Iris Marion. Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Iris Marion. Inclusion and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. [ Links ]

2 - About the use of managerial models in Brazilian public policy, see, for example, Jannuzzi, 2005. About the appropriation of this type of business model in educational policies, see also Bowe; Ball; Gold (1992); Ball (1998).

3- “A clear indication of what is expected of the high school philosophy teacher can be found in the Curricular Guidelines to the Undergraduate Courses in Philosophy and in the Inep Document n° 171, issued on 24 August 2005, that instituted the National Exam of Student Performance (Enade) in Philosophy, which also presents the abilities and skills expected of the professional responsible for implementing the guidelines for high school.” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 31).

4- The 2009 reference matrix for the Humanities component of Enem is available at: http://download.inep.gov.br/download/Enem/matriz_referencia.pdf

5- “Also pressing are the worries of ethical nature, that raised by political episodes in the national and international scenario, as well as the debates around the criteria employed in scientific discoveries. Analogous situation was detected in other instances of public discussion and social mobilization, for example, the debates concerning the behavior of communication vehicles such as the television and the radio. Although, for the most part, one cannot speak of a rigorous conceptualization, one cannot ignore that these discussions involve themes, notions and criteria of philosophical nature.” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 15).

6- “We can detect, once again, a convergence between the educational role of Philosophy and education for citizenship that was postulated earlier. The knowledge necessary for citizenship, in as much as it is translated in skills, does not coincide, necessarily, in contents, let us say, of ethics and of political philosophy. On the contrary, it highlights what is, without doubt, the most important contribution of Philosophy: to make the student acquire a discursive-philosophical skill. It is expected from Philosophy, as previously noted, the general development of communicative skills, which imply a kind of reading, involving capacity for analysis, interpretation, rational reconstruction and criticism. With this, the possibility of taking a stand for yes or for no, for agreeing or not with the purposes of the text is a necessary and decisive prerequisite for the exercise of autonomy and, consequently, for citizenship”. (BRASIL, 2006, p. 30-31).

7- “In the examples below, each question is referred to by the number it appears on the blue version of that year´s Enem.

8- “[It] was decided that the assessment of the undergraduate courses in Philosophy should take as central axis the minimum curriculum composed of five basic areas: History of Philosophy, Theory of Knowledge, Ethics, Logic and General Philosophy: Problems in Metaphysics.” (BRASIL, 2006, p. 20).

Received: August 29, 2019; Revised: March 03, 2020; Accepted: June 02, 2020

texto em

texto em