Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 20-Jan-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248234239

ARTICLES

Anthropology of education: mapping the origins of a research field1

2- Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brasil. Contacts: brunolaa@hotmail.com; fcarniel@uem.br

The purpose of this article is to describe the practice through which the foreign network of studies on anthropology of education acquired credibility for its writings, using literary inscription. The literary inscription is a methodological principle that allows the analysis of intellectual networks in educational research about learning and knowledge acquisition processes. The threads connecting the components of these networks are explored through the analysis of a seminal book for anthropology of education in the United States and Europe, but which was and continues to be disregarded by Brazilian academia. The book Education and anthropology, edited by George D. Spindler, in 1955, seminally described the main ideas, approaches and theoretical-methodological affiliations that began to organize research on anthropology and education abroad. The work is analyzed to offer Brazilian academia an agenda for uses and interpretations of the anthropology of education outside the country. From the analyzed book, it was possible to perceive the construction of a polysemic agenda of uses and interpretations of the term culture by the field of education studies. In this way, a partial narrative of the conception of the scientific field of anthropology of education is offered, which can be connected to other local, state and national versions.

Key words: Anthropology; Education; Anthropology of education; School organization; Literary inscription

O objetivo deste artigo é descrever a prática por meio da qual a rede estrangeira de estudos sobre antropologia da educação adquiriu credibilidade para as suas escritas, utilizando a inscrição literária. A inscrição literária é um princípio metodológico que permite analisar redes intelectuais nas pesquisas educacionais acerca dos processos de aquisição de aprendizagem e conhecimentos. Os fios que conectam os componentes dessas redes são explorados por meio da análise de um livro seminal para o campo da antropologia da educação nos Estados Unidos e na Europa, mas que foi e segue sendo desconsiderado pela academia brasileira. Trata-se do livro Education and anthropology, editado por George D. Spindler, no ano de 1955, que descreveu de forma seminal as principais ideias, abordagens e filiações teórico-metodológicas que passaram a organizar as investigações sobre antropologia e educação no exterior. A obra é analisada para oferecer à academia brasileira a agenda de usos e interpretações da antropologia da educação fora do país. A partir do livro analisado, foi factível perceber a construção de uma agenda polissêmica de usos e interpretações do termo cultura pelo campo de estudos da educação. Desse modo, uma narrativa parcial da concepção do campo científico da antropologia da educação é oferecida, podendo ser conectada a outras versões locais, estaduais e/ou nacionais.

Palavras-Chave: Antropologia; Educação; Antropologia da educação; Organização escolar; Inscrição literária

Introduction

Who said that anthropology would have nothing to offer to the understanding of school life? The long history of disagreements between anthropological perspectives and educational research no longer seems to conceal the enormous interest that the field has aroused in the academic world. Currently, there are numerous works and collections dedicated to education. New forums for specialized debate are opened every year to analyze different aspects of education systems. More and more students appear at universities with the desire to carry out fieldwork in schools. Even the discipline of anthropology of education was able to consolidate itself in specific undergraduate and graduate courses with the ambition of qualifying teacher education. However, what motivates all this movement? What is expected of this area today that was not expected nearly a century ago?

When discussing the origins of these dialogues between anthropology and education, Gusmão (1997) observes that the apparent novelty that would have been established in the last decades of the 20th century regarding the discovery of alterity, relativism and differences, by the educational debates, makes a denser and richer tradition between the two areas invisible. This tradition dates back to the very constitution of modern projects of human formation. A meeting that began at the end of the 19th century, with the first attempts to understand the interfaces between childhood and educational systems (GALLI, 1993), developed in different countries during the first decades of the 20th century through offices of pedagogical anthropology. In these and other movements of the period, anthropology was present as an area capable of putting into perspective the supposed universality with which formal educational models are usually presented.

One of the episodes of these attempts to articulate the fields of work of anthropology and school organization occurred during the 1930s and 1940s, in the context of curriculum reforms promoted in the United States. Under the strong influence of Franz Boas’ culturalism, several anthropologists participated in the creation of curriculum plans, teaching materials and developed numerous reports and comparative analyzes between education systems in different realities. Among the known consequences of this performance are the works of Margareth Mead. In her body of work, Mead (1951) converted education into a privileged object for anthropology by arguing that it was precisely through educational processes that people could experience cultural patterns.

With such concerns in mind, George Spindler managed to assemble a working group willing to discuss the construction of the then-emerging disciplinary field of anthropology of education in the United States. Thus, in 1954 he organized the first conference dedicated to debating advances in studies carried out in school organizations. Gathered at Stanford, eminent American anthropologists of the time, such Margaret Mead, David Baerreis and John Whiting, spoke to a heterogeneous audience of professionals linked to education. The objective was to explore the borders between the areas and the potentialities of the ethnographic method, its concepts, and the research problems presented by the different fields of work. To synthesize and disseminate the results of these exhibitions, Spindler also coordinated the editing of a work that became one of the seminal landmarks in the anthropology of North American education: the handbook Education and anthropology, published in 1955.

Each intellectual generation that followed the efforts made by the group coordinated by Spindler perceived and attributed particular meanings to this history and the meanings of anthropology of school life. However, in different intellectual contexts, the apparent silence regarding the dialogues between anthropology and education at Stanford reveals how far removed from school life were the concerns of several anthropologists. In this text, it is not interesting to reify Spindler’s work or transform it into a kind of founding myth of a disciplinary field that is beginning to consolidate itself in the present. We only intend to assume a classic handbook as a historical document capable of revealing sensitive aspects of the web of associations and interests that moved North American anthropology in the 1950s. Based on the collection organized by Spindler (1984), the purpose of this article is to describe the practice through which the network of studies on anthropology of education acquired a credibility for its writings, using the notion of literary inscription.

Latour and Woolgar (1997) used the notion of literary inscription to organize their fieldwork at the Salk Institute. Literary inscription allowed these authors to demonstrate how statements were turned into facts in a laboratory designed to conduct biological research. In this case, the literary inscription is an organizing principle that systematically classified and reported the book’s observations organized by Spindler (1955). Therefore, this article assumes Spindler (1955) as a system of literary inscription “whose purpose is, sometimes, to convince that a statement is a fact” (LATOUR; WOOLGAR, 1997, p. 101). For this, the focus of the analysis was directed to the handbook (written document) and the inscription devices (meta-research, bibliographical research, analysis of other articles) that extended the work and were used by other works in the exploration of anthropology of education.

Anthropology of education is a delicate field to be investigated, as academic texts are usually perceived by the ideas they convey rather than the material operations they establish (CARNIEL; AMÉRICO, 2018; AMÉRICO; CARNIEL; CLEGG, 2019). We understand that by ‘entering’ this text, we can also access public aspects of the relationships favouring the postulation of legitimate and stable ways to investigate the modern educational universe. This research does not intend to reconstruct the history of the formation of the anthropology of education. We only intend to present an alternative view to the one that specialists in the field already offer about their work.

Opening the handbook

Even without knowing what we would find in this collection of texts from 1955, we started reading. In Foreword, George Spindler reveals that the book brings together articles that systematize four days of a conference on the interrelationships between education and anthropology. Eddy (1985, p. 84) argues that the Conference on Anthropology and Education, convened at Stanford in 1954, represented a historic shift for the anthropology of education. As Spindler (1955) reports, such a conference had been initially conceived and planned in conjunction with Margaret Mead, David Baerreis, and John Whiting at the 1952 annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association.

After the 1952 meeting, the ideas shared by anthropologists and educators prompted responses and suggestions that served to support the request for funding to the Carnegie Foundation for a conference and the elaboration of a later handbook with the results. With the resource, it proceeded to the planning phase, which involved members of the School of Education and the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Stanford University and the University of Chicago. A final discussion of the conference, which was convened in 1954, was held by different anthropologists at the 1953 meeting of the American Anthropological Association. The sum of efforts, meetings, and discussions generated contributions from more than ten universities and people involved in education and anthropology prior to the conference. The exploratory format of the conference and the organization of its results, as reported by George Spindler, is due to the interest in understanding the boundaries of the relationships between the disciplines of anthropology and education and the weak and vital aspects of its concepts, data, methods, problems.

George Spindler states that the topics and areas defined for the conference, which would organize the book’s structure, served as a springboard to open discussions around the field of studies. However, more than the construction of an integrated/privileged perspective for the (ethnographic) study of schools and educational systems (networks) where they are inserted, the first contact with Spindler (1955) aroused concern in understanding how the texts narrated the academic territory they had just invented and in which they found themselves.

So, we started to read the “Preface” of the work, which Lawrence K. Frank wrote to continue the “Foreword”. Based on the reading of this preface, we understand that to understand how the texts that compose Spindler’s work (1955) narrate the field of anthropology of education, and it would be necessary to “recall what has been taken place during the past fifty years in education” (FRANK, 1955, p. 7). Moreover, since “ideas and knowledge can extend in all directions in space and time” (LATOUR, 1994, p. 116), the book confirmed the initial instinct that an artefact – even presenting the purified form of a book – has the power to offer an exciting starting point for retracing the genesis of such a chain of associations.

For Lawrence K. Frank, the comparison with education studies began in the nineteenth century with psychologists studying learning processes through laboratory animals and training transfer and developing standardized tests to assess and measure education and various experimental learning programs. Sociologists and psychiatrists supplemented these contributions. For Lawrence K. Frank, this happened when extracurricular variables, mainly linked to the students’ families, were assumed as significant factors for community studies and schoolchildren’s clinical investigations. For Frank (1955), this recognition produced guidance programs and the diagnosis of children with low school performance. Thus, the responsibility of schools for students’ difficulties began. Finally, Lawrence K. Frank follows his chronological account for studies on child development and growth in the 1930s, when committees were created and funded to develop - longitudinal and quantitative, despite the pioneering participation of anthropologists - studies which began to question the need for a set of strict requirements imposed on students. Instead, it focused on developing the personality of students and improving the teaching conditions of teachers, given the inclusion of new educational topics.

The study of personality, individuality and culture, including questions about the acculturation and socialization of children to reveal patterns and relationships existing in organizations and educational systems, are, for Lawrence K. Frank, the main contributions of anthropology to education in the 1930s – at least until the beginning of World War II. The seminars on the Impact of Culture on Personality (Yale, 1930, under the direction of Edward Sapir) and on Human Relations (Hanover, 1934) deserve to be highlighted. During this period, in the perception of Lawrence K. Frank, numerous studies showed that each child learns in a way while striving to assert his individuality as part of a social group. It is evident that the school – and especially the universities responsible for training teachers – must contribute to the development of each child, not just socially adjusting and adapting them.

In his reflections, the author points out that the results of the studies demand greater responsibility from the school as a service provider for students and families. The family is no longer considered the primary institution responsible for teaching academic skills and a predetermined set of knowledge. In order to conceive this new meaning attributed to school organization, which must operate more effectively and be aware of its achievements in our society, Lawrence K. Frank points out that anthropology can contribute through its accumulated studies. Studies that describe the educational process from early learning in different cultures and beyond formal education.

Before we present the analysis of the first of the ten sections that make up Spindler’s work (1955), Eddy’s text (1985) is analyzed. The aim is to examine the historical development of the anthropology of education within the limits of the growth and expansion of the discipline of anthropology as a whole. According to Eddy (1985, p. 83), the historical roots of (one of many) the anthropology of education interest group can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, “when anthropology emerged as a science”. Eddy (1985), Barnes and Barnes (2012), Chamberlain (1896), Fletcher (1888), Stevenson (1887) and Vanderwalker (1898) were the first to recognize that anthropology could contribute to pedagogy, the school curriculum and with the understanding of childhood culture. Considering that contemporary educational anthropology is responsible for the growth and development of social and cultural anthropology in the 1920s, Eddy (1985) argues that she starts the analysis based on 1925 to 1954. Within her proposal, the formative years, they articulate the professionalization of anthropology with the development of the anthropology of education as a specialized area. Next, we review the bibliography cited by Eddy (1985) for this period that precedes Spindler (1955).

Similar to Frank (1955) and Eddy (1985), Robert and Akinsanya demonstrate that a remarkable number of anthropologists were dedicated to analyzing formal education systems and the acculturation of children between the 1930s and 1960s. Eddy (1985) points out that only Malinowski and Boas started their careers before anthropology broke with the nineteenth century. That is, with a unilinear evolutionism and theories that significantly emphasized the role of diffusion in the history of culture. Eddy (1985) states that the symbolic birth of social anthropology – practical/applied – can be given to Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown. However, the works of English anthropologists, or even “the scientific knowledge produced by this type of study”, dedicated to the contemporary study of human behaviour and institutions, could be applied to “practical problems of administrative planning and educational policies for native populations in the British colonies” (EDDY, 1985, p. 85). According to Eddy (1985), a similar transition took place in the United States through the work of Boas and Mead. These authors revealed the practical importance of the anthropologist’s work for educational problems. For Eddy (1985, p. 85), the writings of Margaret Mead, guided by Boas, argued in favour of the value of comparing “American civilizations with ‘simple’ societies in order to illuminate our methods of education”.

By offering a perspective on the terrain in which applied, practical and social anthropology emerged, and was subsequently translated into the understanding of educational issues and inquiries, Eddy (1985) describes the relationships between institutional changes in the discipline of anthropology after 1920 and the intellectual developments of modern social and cultural anthropology. The author narrates changes in the funding bases of anthropological work, investments by the United States of America and Europe in organizing education in Africa and indigenous populations worldwide and promoting the international exchange of scholars, encouraging interdisciplinary work in universities to understand problems related to race, immigration and the impact of social changes. An analysis of the life history of some anthropologists was included. However, the economic and institutional aspects, as well as the social/interdisciplinary relations evidenced by Eddy (1985), too hastily correlated with the definition of the social sciences as applied science, give the impression that anthropology is another of the countless sciences” whose ideal would be perverted by man, or deviated by industry, money and the century […]” (LATOUR; WOOLGAR, 1997, p. 19). Moreover, the author’s narrative lacks a synthesis between economic, institutional and psychological notions, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the production of problems, inquiries, doubts, certainties by anthropology. Thus, the mode of production of anthropological knowledge in the formative period remains obscure and arbitrary despite the effort.

We decided to start with the analysis developed by Eddy (1985) on the application of anthropology in education in this period from 1925 to 1954 to highlight the theoretical clash of anthropologists with the ideas of Freud, Piaget and Watson. More than a clash between authors, it was a challenge between two perspectives. One dedicated to understanding the generalization about behaviour and human development. The other was dedicated to mapping information about variations between cultures. Among the studies listed by the author, some have shown that there are different acculturations and participation in formal educational systems in American society concerning different races, ethnicities, and social classes. Examples are Davis, Gardner and Gardner (1941), Dollard (1937), Drake and Cayton (1945), Gillin (1948), Hollingshead (1949), Johnson (1941), Lynd and Lynd (1929), Warner (1942), Warner and Lunt (1941), Warner, Havighurst and Loeb (1944) and West (1945). Other authors have written ethnographic works for bilingual indigenous school texts and orthographies, as reported by Eddy (1985) based on Kennard and MacGregor (1953). In step with Frank (1955), Eddy (1985) points to the involvement of American anthropologists, funded by foundations and corporations, in revising the high school social studies curriculum, studying school life and the communities in which students were found, and organizing seminars on the Impact of Culture on Personality (Yale, 1930, under the direction of Edward Sapir) and Human Relations (Hanover, 1934). An example offered by Eddy (1985) was the interdisciplinary participation of psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians, and anthropologists in a six-year cooperative social action research program. Initiated in 1941 by the United States government and in partnership with the University of Chicago and the Society for Applied Anthropology, the study addressed Indian personality, education, and administration. Eddy (1985) reports that the study was carried out with approximately one thousand children in twelve reserves belonging to five tribes to collect scientific information supporting better public policies for the Indian administration and educational programs. The author also reports Malinowski’s participation in an international conference in South Africa (New Education Fellowship, 1934). The organization of a conference at the University of Hawaii to address issues of education and adjustment among people in the Pacific (KEESING, 1937). And a lecture at Teachers College in New York (The educational problems of special cultural groups, 1949).

Still on the application of anthropology in education, until 1954, we find Yon’s (2003) text among the studies that cite Spindler (1955). This author describes some seminal works that supported the emergence of the anthropology of education discipline as a legitimate field of study. Works such as Mead (1951), Pettitt (1946), Spindler (1955), Boas (1962). Yon, inclusively, departs from Eddy (1985) to characterize his second topic of study, called The formative years. The anthropology of education, in this period, increasingly claimed and defended the rights/interests of marginalized groups. For Yon (2003), British structural-functionalism influenced the anthropology of education in the United States in its formative period, presenting Pettitt’s study (1946) as one of the seminal researches of this holistic paradigm in anthropology studies of education in indigenous cultures of that country.

According to Yon (2003), culture was increasingly understood as dynamically changing in its transmission process in these formative years. And ethnography as a social and reflective enterprise. A work that reflects (and even evokes) the dynamic posture of research developed at the time, according to Yon (2003), is The School in American Culture (MEAD, 1951). Yon (2003) understands that this work by Margaret Mead juxtaposes the small red schoolhouse with the school in the modern city. For this reason, it favoured work with themes related to the pathology of North American culture, personalities (contrasts from schools) and cultural change. The themes of personalities and cultural change were predominant in the anthropology of education in this period, as Yon (2003) reported on Spindler (1955). Finally, Yon (2003) points out how some ideas of Boas (1962) influenced the concerns and questions that began to distinguish the anthropology of education at that time and in the coming decades. Through a method that emphasizes the social formation of the group, many studies have focused on analyzing how meanings until then considered innate – such as race – are culturally supported social constructions. As Eddy (1985) and Yon (2003) demonstrated, this formative period was marked by constant approximations between the European and North American anthropology and anthropology of education.

Through the studies developed during this period of formation, the field of studies in the anthropology of education established itself as a fact progressively. In this process, as demonstrated by Wolcott (1987), Frank (1955), Eddy (1985), Yon (2003), the work organized and edited by Spindler (1955) summarized the discussions carried out during the first Educational Anthropology Conference at Stanford in the year of 1954. In this way, the handbook actively participated in how the area established under the anthropology of education stabilized itself as an unquestionable fact. The objective, therefore, will be from the discourse set by the handbook to understand through it how a particular set of scientific texts, organized to situate their research as anthropological and educational, managed to establish a network of material and symbolic associations that contribute to sustain and maintain a part of the theoretical propositions and empirical investments of the anthropology of education around the world.

The meanings of the field of anthropology of education

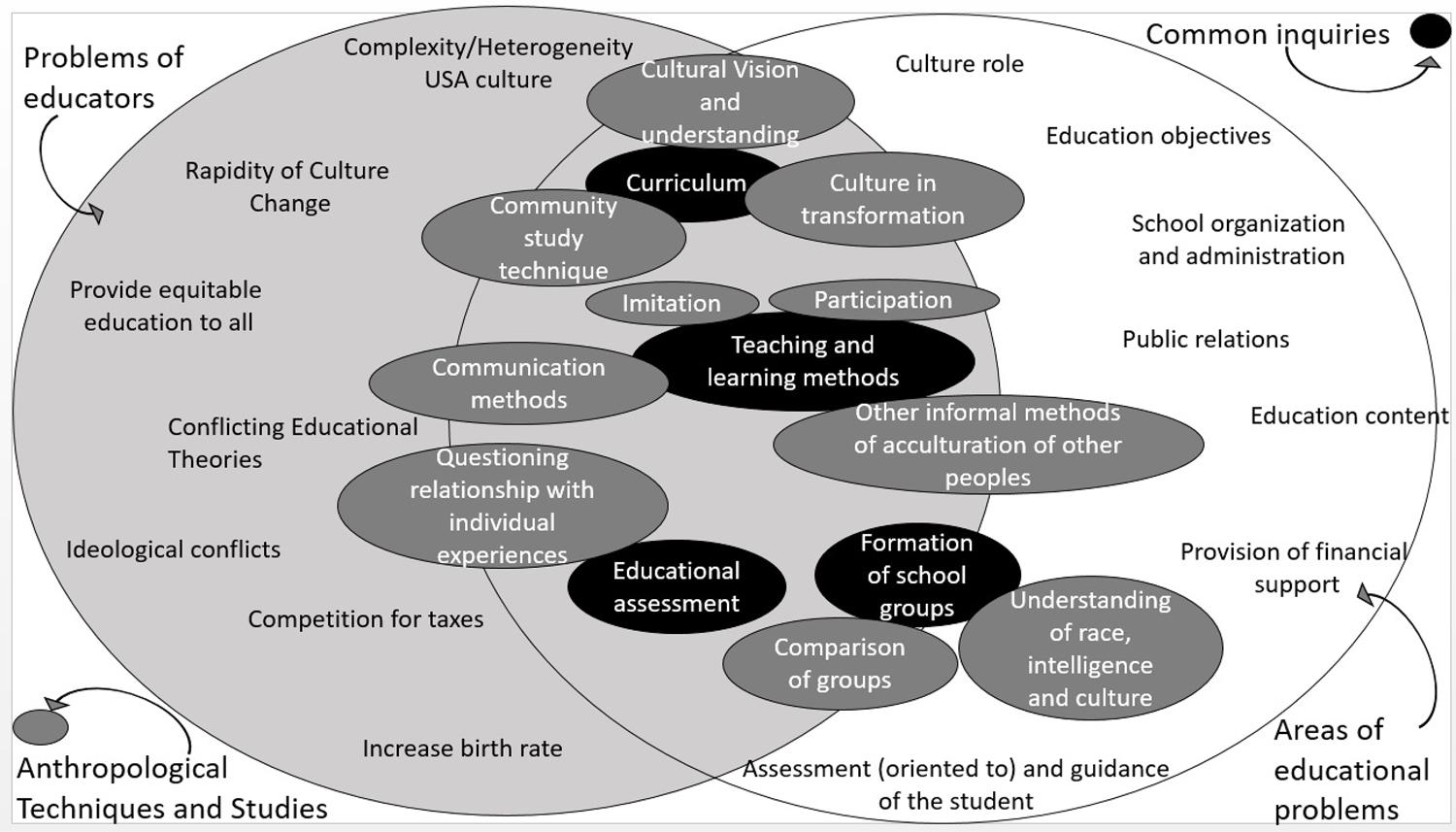

This topic covers the first of ten sections of the Introduction to anthropology and education. This first section was written by historian James Quillen, affiliated with the Stanford School of Education from 1936 to 1967 when he died. Quillen’s text (1955, p. 1) defines “some of the problem areas in education where anthropology can make a contribution”. For the author, based on the assumption that education is a cultural process, anthropologists can resolve the conflict about the school’s appropriate role, contributing to the efforts previously carried out by biologists, sociologists, psychologists, historians, and philosophers. When considering the conceptual knowledge and tools offered by the discipline, Quillen (1955) recognizes that the problems faced by educators go beyond the areas in which the interests of anthropologists and educators converge. Figure 1 seeks to make visual Quillen’s (1955) description of the problems faced by educators and the areas in which educational problems are centred, as well as the inquiries common to both areas about anthropological techniques/studies.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 – Anthropological/educational issues and the relationship with anthropology

It is important to note that Quillen’s (1955) description, represented in Figure 1, is structured around two central concepts: the school’s genuine concern and its expected function. On the one hand, the author attests to the importance of assuming the cultural transmission and formation of students’ personality as a school function, revealing anthropology’s potential in dealing with themes related to acculturation and socialization. On the other hand, Quillen presents other functions expected of the school but considered conflicting: cultural innovation and the extension and development of North American culture. Therefore, the author moves on to the recognition that the school’s educational agency competes with other organizations that are not necessarily formal (such as family, church, mass communication, friends), to demonstrate how the content of anthropology on the influence of unrelated educational experiences to school can help strengthen the school’s agency – whether expected or desired. However, Figure 1 should not indicate that the discipline of anthropology of education, through its toolbox and comparative cultural studies bank, depends solely on its potential to invigorate the capacity for action of the increasingly overloaded school organization and school system (FRANK, 1955; QUILLEN, 1955). The recognition that the scientific authority of a given discipline is inevitably mediated by claims of rhetoric and power (BLOOR, 1981; KNORR-CETINA, 1981; KNORR-CETINA; MULKAY, 1983; LATOUR, 1984) allows us to consider that the facticity of these postulations also needs to be seen as the cause and not the consequence of the practical school universe that they paradoxically claim to represent. Quillen (1955) introduces the problems and functions of the school and the objects of interest of research in the anthropology of education in a language that is sufficiently persuasive for both areas. Once Quillen (1955) does this, the school’s multiple and complex functions and problems move away from the countless controversies that would have allowed its postulation to be established as stable facts that would support the organization of a whole network of research.

Quillen (1955) persuades educators and anthropologists to argue that the framework mobilized by anthropology operated as the foundation of new studies in the emerging anthropology of education while representing a kind of synthesis of the efforts made by studies devoted to research interlocutors and prolonged participant observation. Thus, this author could generate a truth effect for the suggestion that anthropology can corroborate the definition of the ideal cultural man/woman and the preservation of society’s core values in the context of school practice. In this way, it was as if, once established as facts validated by a network of work, the anthropological categories used to investigate empirical phenomena were split into two distinct entities. On the one hand, they were still a string of words that would communicate something likely about a particular object. However, on the other hand, these same statements were transformed into phenomena independent of those previously studied, activating a grammar already consolidated by the study of other related issues.

Thus, Quillen (1955, p. 2) treated curriculum (Figure 1) as a problem shared by educators and anthropologists. He promoted the understanding that the selection of the school program from countless possibilities can only be undertaken based on “considerable cultural insight and understanding”. Through other operations in which the phenomenon and the interpretation of the phenomenon are mutually reinforcing, Quillen (1955) presents the teaching-learning methods (Figure 1) as another problem that belongs to anthropologists and educators. For this, the author promotes the understanding that studies on acculturation in other cultures allow educators to seek ways for the knowledge transmitted in the classroom to be effectively apprehended in the social life of students. Arguing those teaching methods could develop democratic citizens, moral and spiritual values, a healthy personality. In this way, Quillen (1955) creates an interpretation that demonstrates how other educational problems, being equally cultural, can be solved only through social anthropology. In other words, the resolution of these adversities can occur through anthropology compared to other peoples and cultures with formal and informal methods of knowledge and techniques and methods related to ethnographic writing. Again, from this perspective, it is impossible to discuss the formation of groups in schools (Figure 1) without dealing with the variety of cultural formations of peoples or the comparative (cultural) interpretation of these groups. Likewise, it would be difficult to talk about student assessment (Figure 1) without questioning whether these tests are culturally fair. Without the invention – enunciated by Roy Wagner – of these related problems, it would be impossible to legitimize the field of studies in the anthropology of education. For this author, “an outside perspective is as readily created as our most reliable ‘inside’ perspectives” (WAGNER, 2012, p. 19). The argument exemplifies this reasoning from cultural relativity, which, by denouncing other generalizing perspectives, presents culture as another illusion in the service of the ordering desires of anthropologists. This illusion, of course, participates in constructing this field, which is familiar to educators and anthropologists.

Although we are aware that the discipline of anthropology and its subdivisions, including the anthropology of education, have acquired validity and scientificity for their research over time, we realize that there is a lack of sufficient elements to enter into this controversy about the legitimacy of the problems evoked as homologous to the areas of education and anthropology. Lack of knowledge of the empirical content responsible for sustaining such interpretations and, otherwise, of alternative points of view that would compete with the history of the anthropology of education (theories, methods, techniques) made the following questioning possible: is there any similarity between the knowledge of educational problems of mutual interest to anthropologists and educators and the knowledge generated about the knowledge of educational problems shared by these professionals? This question was elaborated considering the existence of an educational problem - around the expected or due function of the school, the formation of groups, educational assessment, curriculum, teaching-learning methods - that produce a cultural and pedagogical response diverges from the knowledge produced about this educational problem by anthropologists and educators. Regardless of the mode of existence of science used to solve this paradox, it is not feasible to deny the existence of both pieces of knowledge, which seem to be conserved in the same network of meanings, a texture supported by the anthropology of education itself. We do not intend to offer the same tautological response as epistemologists (cf. LATOUR; WOOLGAR, 1997). In order to do so, we chose to promptly return to Spindler (1955) before the usual paths of scientific interpretation understood this object.

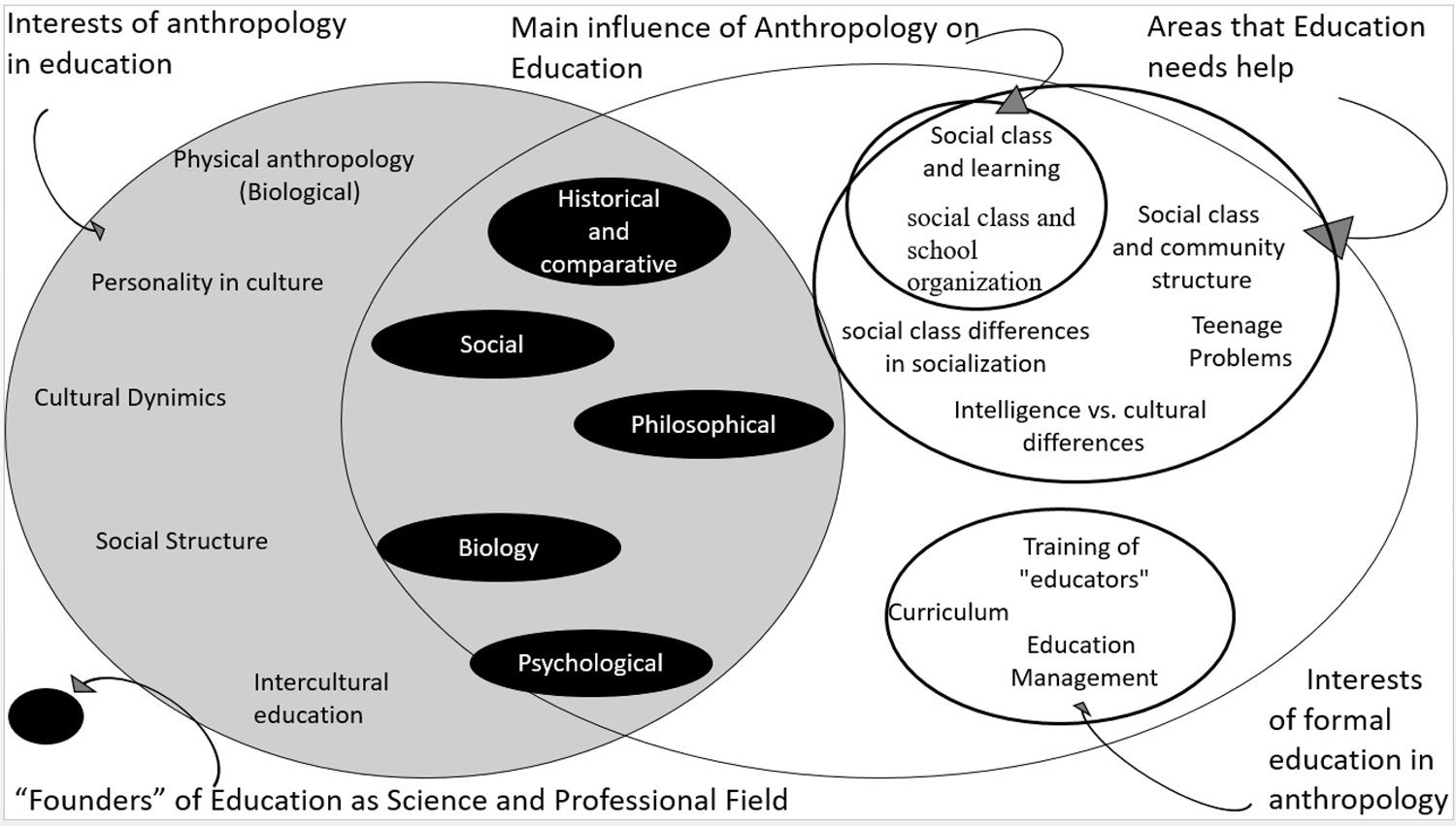

As we continue to read the first section of Education and Anthropology, we come across a chapter written by the editor of this 1955 work, George Spindler. We refer to Anthropology and education: an overview. Spindler (1955, p. 5) positions his general objective of “survey the articulation of these two fields” in opposition to the recognition that educational anthropology existed at the time of that writing. Figure 2 demonstrates the fields and interests considered relevant by the network mutually performed by educators and anthropologists (SPINDLER, 1955).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 – Relevant fields and interests by the network mutually performed by educators and anthropologists

In narrating the interests of anthropology in education, represented by Figure 2, Spindler (1955) relates physical (biological) anthropology to a text named Pedagogical anthropology by the author Montessori (1913). The author follows his reasoning, pointing out that the theme of race within physical (biological) anthropology was also a significant contribution to education, primarily through the works of Otto Klineberg on the relations between race, culture and IQ and Ethel Alpenfels about meanings of race and the myth of racial superiority. Therefore, the author points out that he perceived interest in the 1954 seminar in the emerging fields of personality in anthropology’s culture and cultural dynamics. Cross-cultural education is another field of anthropology of importance for education, according to Spindler (1955, p. 7), who endorses Pettitt’s (1946) work as “the kind of thing that needs to be done with more comparative cross-cultural data”. According to Spindler (1955), there are other areas of anthropology – more problematic and poorly defined, except for Herskovits (1943) – of benefit to education, such as cultural dynamics, which analyze processes of change and cultural stability based on the understanding that education operates amidst cultural demands. There is also the field of the social structure of anthropology, which contributes to the problems of education. Finally, when discussing the main influences of anthropology on education (Figure 2), Spindler (1955) states that it is necessary to know works that analyze educational processes and problems to a social class and the structure of the community. Furthermore, we also know more about non-literary societies (simple societies) to truly understand education as a sociocultural process.

Moving from the narrative about the interests of anthropology in education to the description of the main influences of anthropology on education, the author shows that, in order to carry out anthropology of education, it is essential that education be understood as a social and cultural process. As a sociocultural process, education – formal or informal – must be considered compared to realizing this process in other societies. In favour of an invention known as cultural relativity, which promotes the search for interrelationships between education networks, educational process and social structure (kinship or rank or complex political-social system) in non-Western societies, researchers’ attention is pushed out of school. With such an insight, how could education live without anthropology?

With this questioning, we would like to highlight what Latour and Woolgar (1997) have already called splitting and inversion in the meanings of scientific statements, a discursive strategy that attributes objectivity and reality to the research activity. In the previous paragraph, Spindler (1955) begins his narrative with the construction of an object of study that intended to say something about the areas of anthropology of interest to education. Such construction, however, would only gain credibility as it managed to translate the particular phenomenon of education problems from a set of categories and perspectives of analysis that, in turn, would allow the fabrication of tools and procedures that allow for the understanding of education - observe, describe, analyze – as a sociocultural process. Once this whole theoretical-methodological framework was produced, Spindler (1955) created a certain correspondence between the problems of education and the very perceptions that the Anthropological interpretation reveals, whether applied, compared, or relative.

In the course of our reading of Spindler (1955), it was possible to evidence the coexistence of different rhetorical strategies that supported and organized the content of its chapters around this necessary and interdependent relationship between education and anthropology. However, to avoid being accused of error, fantasy or falsehood, Spindler (1955) needed that his interpretations of reality and reality itself intertwine but not be confused. To this end, a rhetorical operation should enable the discourse about educational problems to be distinguished from the anthropological discourse. The immediate implication of this split was not only the separation between phenomenon and interpretation but, above all, the inversion in the order of their meanings. From an intellectual construct produced by the researchers, the problems of education came to be described tautologically through the reformulation or re-enunciation of the narratives that had generated them. It was precisely this inversion in the quality of utterances that created the illusion that, when writing about the meanings of the problems of education, they would also be writing about an independent fact: the problems of education, as they really would be.

This process by itself will not guarantee that certain statements will establish themselves in the universe of the anthropology of education. Mainly because, as we will understand in the continuation, numerous other works emerged until 2016, sustaining divergent perspectives and contesting the credibility of these enunciations paved around cultural relativity. However, since Spindler (1955) was able to formally establish the area of anthropology of education through texts that also promoted the split and inversion of statements around educational problems and anthropological research paths, this field can acquire certain independence about its objects of study and undergo a new transformation: what was an observation of the problems of education (particular reality or fact) became the indication of something more profound (episteme). At least, this was how Spindler (1955) managed to formalize a field of study dedicated to the relationships between education problems in anthropology. Reasoning that would only be revealed by examining the practices of school organizations and education systems. The interpretation managed to detach itself from the research context through deduction and generalisation to achieve a relatively autonomous existence and successfully support the theoretical-conceptual construction of several other particular realities.

Conclusion

According to Spindler (1955), the content presented so far is radically different from the rest of the research presented during the 1954 symposium. For this author, regardless of whether other texts extrapolate what is known as traditional anthropology, the research could “put into motion some applications of mutual relevance to both fields. They are experimental and question-raising, therefore, since no articulated education anthropology structures exists from which they could draw” (SPINDLER, 1955, p. 6). Thus, this text sought to debate the process of building ethnographies in school organizations from the stabilization of the anthropology of education as a fact. The construction of this field, or even this fact, stabilized countless safe and stable starting points for the production of new works.

Consequently, they also created an entire research network properly organized around certain concepts and perspectives of analysis. The intention is not to deny the idea that reality can exist independently of scientific activity. On the contrary, we only affirm that the objective existence of scientific objects is the consequence and not the cause of the research work (LATOUR; WOOLGAR, 1997).

Nowadays, the anthropology of education, which had its history and scope as a discipline and field defined by numerous works after Spindler (1955) (cf. BANKS, 1993; EDDY, 1985; FISHER, 1998; HESHUSIUS; BALLARD, 1996; LEVINSON; WINSTEAD; SUTTON, 2020; SPINDLER, 1982; WILCOX, 1982) can be understood as a fact. Although anthropology of education and anthropology, from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, did not demand a hypothetical scientificity of their texts, it was precisely the recognition of the multiple meanings of culture, the imposed reflexivity and the limits associated with ethnographic work, added together to an object of study – school organization and education networks – of multidisciplinary interest, which allowed an exponential increase in its publications (SPINDLER, 1984; 2000). Even so, the appeal to new representations of ethnographic research techniques formerly employed in schools remains open. In other words, we hope we have not left the impression that classical studies in the anthropology of education should be discarded. For example, Jackson’s (1968) work offers substantive inputs for considering transitional events at school, in the classroom, so that it is possible to provide information about school life (Life in classrooms). Alternatively, as indicated by Smith and Geoffrey (1968), it is relevant to pay attention to written forms that remain hidden from participant observation, within the students’ pockets, in the form of letters written by parents to schools (or vice versa) (Complexities of an urban classroom). On the one hand, culture can no longer be seen as “property of social groups, bounded, determined, and internally coherent, and the kinds of certainty that characterized ethnographic findings in earlier eras could no longer be guaranteed” (YON, 2003, p. 423). On the other hand, ethnographic writing continued as a form of writing and contested representation from which it is feasible to understand school organization in (and despite any) practice.

REFERENCES

AMÉRICO, Bruno Luiz; CARNIEL, Fagner; CLEGG, Stewart Roger. Accounting for the formation of scientific fields in organization studies. European Management Journal, Amsterdam, v. 37, n. 1, p. 18-28, 2019. [ Links ]

BANKS, James. Multicultural education: historical development, dimensions, and practice. Review of Research in Education, New York, v. 19, p. 3-49, 1993. [ Links ]

BARNES, Earl; BARNES, Mary Sheldon. Education among the Aztecs. In: BARNES, Earl. Studies in education: 1896-1902. v. 2. [S. l.]: General Books, 2012. p. 73-80. [ Links ]

BLOOR, David. The strengths of the strong programme. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, Thousand Oaks, v. 11, p. 199-213, 1981. [ Links ]

BOAS, Franz. Anthropology and modern life. New York: Norton, 1962. [ Links ]

CARNIEL, Fagner; AMÉRICO, Bruno Luiz. Rastreando os territórios da aprendizagem organizacional no Brasil. Sociologias, Porto Alegre, v. 20, n. 47, p. 392-423, 2018. [ Links ]

CHAMBERLAIN, Alexander Francis. Child and childhood in folk thought. New York: Macmillan, 1896. [ Links ]

DAVIS, Alisson; GARDNER, Burleigh Bradford; GARDNER, Mary. Deep south: a social anthropological study of caste and class. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1941. [ Links ]

DOLLARD, John. Caste and class in a southern town. London: Yale University, 1937. [ Links ]

DRAKE, St. Clair; CAYTON, Horace. Black metropolis: a study of negro life in a northern city. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1945. [ Links ]

EDDY, Elizabeth. Theory, research, and application in educational anthropology. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, New York, v. 16, n. 2, p. 83-104, 1985. [ Links ]

FISHER, Anthony. Anthropology and education in Canada, the early years (1850-1970). Anthropology & Education Quarterly, New York, v. 29, n. 1, p. 89-102, 1998. [ Links ]

FLETCHER, Alice. Glimpses of child-life among the Omaha Indians. Journal of American Folklore, New York, v. 1, n. 2, p. 115-123, 1888. [ Links ]

FRANK, Lawrence. Preface. In: SPINDLER, George. Education and anthropology. Palo Alto: Stanford University, 1955. p. vii-xi. [ Links ]

GALLI, Amanda. Conceptos sobre educación contínua. Medicina Infantil, Buenos Aires, v. 1, n. 1, p. 37-39, 1993. [ Links ]

GILLIN, John. The old order amish of Pennsylvania. In: GILLIN, John. The ways of men: an introduction to anthropology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1948. p. 209-220. [ Links ]

GUSMÃO, Neusa Maria Mendes. Antropologia e educação: origens de um diálogo. Cadernos Cedes, Campinas, v. 18, n. 43, 1997. [ Links ]

HERSKOVITS, Melville. Education and cultural dynamics. American Journal of Sociology, Chicago, v. 48, n. 6, p. 737-749, 1943. [ Links ]

HESHUSIUS, Lous; BALLARD, Keith. From positivism to interpretivism and beyond: tales of transformation in educational and social research (the mind-body connection). New York: Teachers College, 1996. [ Links ]

HOLLINGSHEAD, August de Belmont. Elmtown’s youth. New York: John Wiley, 1949. [ Links ]

JACKSON, Philip. Life in classrooms. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, Charles. Growing up in the black belt: negro youth in the rural south. Washington, DC: American Council on Education, 1941. [ Links ]

KEESING, Felix. Education in Pacific countries. Shanghai: Kelley and Walsh, 1937. [ Links ]

KENNARD, Edward; MACGREGOR, Gordon. Applied Anthropology in government: United States. In: KROEBER, Alfred (ed.). Anthropology today. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1953. p. 832-840. [ Links ]

KNORR-CETINA, Karin; MULKAY, Michael. Science observed: perspectives on the social study of science. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1983. [ Links ]

KNORR-CETINA, Karin. The manufacture of knowledge: an essay on the constructivist and contextual nature of science. Oxford: Pergamon, 1981. [ Links ]

LATOUR, Bruno. Jamais fomos modernos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. 34, 1994. [ Links ]

LATOUR, Bruno. Les microbes: guerre et paix, suivi de irréductions. Paris: La Découverte, 1984. [ Links ]

LATOUR, Bruno; WOOLGAR, Steve. Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts. Princeton: Princeton University, 1997. [ Links ]

LEVINSON, Bradley; WINSTEAD, Teresa; SUTTON, Margaret. An anthropological approach to education policy as a practice of power: concepts and methods. In: POPKEWITZ, Thomas; FAN, Guorui. Handbook of education policy studies. New York: Springer, 2020. p. 363-379. [ Links ]

LYND, Robert Staughton; LYND, Helen Merrell. Middletown: a study in American culture. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1929. [ Links ]

MEAD, Margaret. The school in American culture. Cambridge: Harvard University, 1951. [ Links ]

MONTESSORI, Maria. Pedagogical anthropology. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1913. [ Links ]

PETTITT, George Albert. Primitive education in North America. Berkeley: University of California, 1946. [ Links ]

QUILLEN, James. An introduction to anthropology and education. In: SPINDLER, George. Education and anthropology. Palo Alto: Stanford University, 1955. p. 1-4. [ Links ]

SMITH, Louis; GEOFFREY, William. The complexities of an urban classroom: an analysis toward a general theory of teaching. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968. [ Links ]

SPINDLER, George. Education and anthropology. Palo Alto: Stanford University, 1955. [ Links ]

SPINDLER, George. Fifty years of anthropology and education 1950-2000: a Spindler anthology. New York: Psychology Press, 2000. [ Links ]

SPINDLER, George. Roots revisited: three decades of perspective. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, New York, v. 15, n. 1, p. 3-10, 1984. [ Links ]

SPINDLER, George; SPINDLER, Louise. Roger Harker and Schönhausen: from familiar to strange and back again. In: SPINDLER, George. Doing the ethnography of schooling: educational anthropology in action. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1982. p. 20-46. [ Links ]

STEVENSON, Matilda Coxe. Religious life of the Zuñi child. In: POWEL, John Wesley (ed.). Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1883-1884. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1887. v. 5, p. 533-555. [ Links ]

VANDEWALKER, Nina C. Some demands of education upon anthropology. American Journal of Sociology, Chicago, v. 4, n. 1, p. 69-78, 1898. [ Links ]

WAGNER, Roy. A invenção da cultura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2012. [ Links ]

WARNER, William Lloyd. Educative effects of social status. In: BURGESS, Ernest et al. Environment and education: a symposium. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1942. p. 16-28. [ Links ]

WARNER, William Lloyd; HAVIGHURST, Robert; LOEB, Martin. Who shall be educated? New York: Harper and Brothers, 1944. [ Links ]

WARNER, William Lloyd; LUNT, Paul. The social life of a modern community. New Haven: Yale University, 1941. [ Links ]

WEST, James. Plainville, U.S.A. New York: Columbia University, 1945. [ Links ]

WILCOX, Kathleen. Ethnography as a methodology and its application to the study of schooling: a review. In: SPINDLER, George. Doing the ethnography of schooling: educational anthropology in action. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1982. p. 456-488. [ Links ]

WOLCOTT, Harry. On ethnographic intent. In: SPINDLER, George; SPINDLER, Louise. Interpretive ethnography of education: at home and abroad. New York: Psychology Press, 1987. p. 37-57. [ Links ]

YON, Daniel. Highlights and overview of the history of educational ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, Palo Alto, v. 32, p. 411-429, 2003. [ Links ]

Received: February 19, 2020; Accepted: June 02, 2020

texto em

texto em