Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 23-Fev-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248239142

ARTICLES

Deaf children and experiences with the written word*

1- Secretaria de Estado da Educação do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil. Contact: rofavoreto@yahoo.com.br

2- Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Contact: alessandra.seabra@mackenzie.br

This article presents part of an investigation into the process of appropriation of the written Portuguese language by deaf children, signers of Brazilian Sign Language (Língua Brasileira de Sinais [Libras]). It seeks to describe their sayings and analyze the induced productions during the research. Six collaborators participated who attended Kindergarten and early elementary school years in a deaf school. This is qualitative, descriptive and exploratory research. Interviews and activities based on telling a story in Libras were used. In these activities, the children wrote words and texts, completed stories, developed characters, and drew pictures. The interviews, conducted in Libras, were videotaped, translated and textualized in written Portuguese. Data analysis found no initial distinction between the Portuguese language appropriation process of deaf children and those who are hearing, as reported in the literature. However, there is a difference when hearing children relate sound to spelling, characterizing the “turning point” for understanding the writing mechanism. We question what can be taken as the “turning point” for deaf children in the apprehension of writing functioning. It has been found that they use visual clues and make conjectures for writing, which may be related to visual awareness. This “turning point” can be favored by a bilingual literacy that involves signwriting, deferred writing and bilingual writing from different bases than those used with hearing children.

Key words: Deaf education; Bilingual education for the deaf; Literacy; Written Portuguese language

Este artigo apresenta parte de uma investigação sobre o processo de apropriação da língua portuguesa escrita por crianças surdas, sinalizantes de Língua Brasileira de Sinais (Libras), e busca descrever os seus dizeres e analisar as produções induzidas durante a pesquisa. Trata-se de pesquisa qualitativa, descritiva e de cunho exploratório. Participaram seis colaboradores que cursavam a Educação Infantil e os anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental em uma escola de surdos. Foram utilizadas entrevistas e atividades realizadas a partir da contação de uma história em Libras. Nessas atividades, as crianças escreveram palavras, textos, completaram histórias, criaram personagens e fizeram desenhos. As entrevistas, realizadas em Libras, foram gravadas em vídeo, traduzidas e textualizadas na língua portuguesa escrita. Na análise dos dados, constatou-se que não há distinção inicial entre o processo de apropriação da língua portuguesa das crianças surdas em relação àquelas que são ouvintes, conforme relatado na literatura; entretanto, há diferenciação em relação ao momento em que as crianças ouvintes começam a relacionar o som com a grafia, caracterizando o “ponto de virada” para o entendimento do mecanismo da escrita. Problematiza-se o que pode ser tomado como o “ponto de virada” para as crianças surdas na apreensão do funcionamento da escrita. Verificou-se que elas utilizam pistas visuais e fazem conjecturas para a escrita, que podem estar relacionadas à consciência visual. Esse “ponto de virada” pode ser favorecido por um letramento bilíngue que envolva elementos como escrita de sinais, escrita diferida e escrita bilíngue, a partir de bases diferentes daquelas utilizadas com as crianças ouvintes.

Palavras-Chave: Educação de surdos; Educação bilíngue de surdos; Alfabetização e letramento; Língua portuguesa escrita

Introduction

The appropriation of the written Portuguese language by deaf people is still the subject of many debates and concerns, both in academia and schools. Despite this, it was found that the number of investigations whose object is the appropriation of the written Portuguese language by deaf children at the beginning of their school career is small.3 This article presents part of the result of an investigation (FAVORETO DA SILVA, 2020) that aimed to answer the following question: How do deaf children who are signers of Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) make records at the beginning of schooling, and what do they say about writing the Portuguese language?

As a presupposition for the investigation, the bilingual education of the deaf stands out - conducted in Libras and Portuguese -, in the perspective in which Libras is the first language of deaf people, which enables the constitution of world knowledge and the construction of meaning in the produced texts, playing a fundamental role in the acquisition of reading and writing (KARNOPP; PEREIRA, 2015).

The Portuguese language in deaf education is considered the second language of Brazilian deaf people who use sign language for communication. It is a language with a morphosyntactic structure distinct from Libras, factors that interfere in the writing process of the deaf. But there is a third aspect that is evident as a central part of this research: the Portuguese language is not the language that enables the organization and development of the thought processes of the deaf, a place occupied by sign language. Thus, it is worth reflecting: “is it possible to know the object of language (of thought) outside of language (of thought)?” (CARDOSO, 2003, p. 11). In other words, in the written Portuguese language, it is common for the deaf person not to use the referent of a concept expressed in the oral language, given the deaf person’s impediment to hearing the spoken word. The referent can be known, but it is not associated with the oral use of the word and, therefore, with the writing of the same word.

The linguistic and cultural differences of deaf students concerning hearing students are evident in learning situations in the school context. Understanding how these deaf students conceive the world through visual experiences is essential. Knowing what deaf children think about writing contributes to understanding the schooling process and creating sources that favor further research.

Writing: the word experience as (in)completeness of tongue

Writing, as a cultural invention, has been characterized in the educational sphere “[…] sometimes as a code, sometimes as the invention of a representation system, sometimes as the invention of a notational system” (SOARES, 2016, p. 46, emphasis added). For this author, writing is a representation system because the child, in her process of understanding the written language – which starts before formal instruction – “reconstructs” the process of inventing the act of writing as a representation. But, when understanding what writing represents (the sound chain of speech, not its semantic content), the child also needs to learn the notation with which, arbitrarily and conventionally, the speech sounds are represented (graphemes and their relationships with phonemes, as well as the position of these elements in the system), thus also characterizing itself as a notational system.

Understanding what and how letters note and represent is a fundamental process for children to learn to write. However, for Faraco (2012), writing is not limited to notation; learning written practices requires diving into discursive traditions since it concerns not only the systems of graphic transcription of verbal language, but fundamentally the mobilization of various types of knowledge, such as grammatical, lexical, social, textual, etc., and of cognitive and socio-cultural practices that neither begin nor end with the mastery of basic literacy skills. These abilities are just the specific moment of learning the written notation system.

The idea that writing is not an oral language transcription code – but a system of representation of reality – and that the literacy process is the progressive domain of this system – which starts before the child goes to school –, and not the acquisition of mechanical skills, is among some of the similarities of approaches on writing from authors such as Vygotsky, Luria and Ferreiro, according to Oliveira (2000).

Vygotsky (1984) and Ferreiro (2001) postulate that children, immersed in a literate society, are exposed to the characteristics, functions, and modalities of written language and its different uses, which will allow them to develop assumptions about this cultural object. The child acquires notions about writing before going to school, which will be systematized in formal learning situations.

Even being part of a literate society, the child does not become literate alone. Unlike the spoken language, which the child can develop by herself, learning to write depends on formal teaching. Learning this complex cultural object depends on deliberate teaching processes, points out Vygotsky (1984). Thus, the author is concerned with an intentional pedagogical intervention so that the child learns to read and write because the mere contact with the object does not guarantee the learning process, requiring the mediation of other people - in this case, the teacher – for the development of the writing appropriation process. Luria (1988, p. 144) postulates that, unlike other psychological functions, “[…] writing can be defined as a function that is culturally carried out through mediation”. It is a tool that enables the expansion of the human capacity to record, transmit and retrieve ideas, concepts and information.

In the school phase, among specificities that involve the appropriation of alphabetic writing, is the fact that deaf children mobilize skills different from those used by hearing individuals; the correspondence between the word sounds and writing, for example, is essential for hearing children (FERREIRO; TEBEROSKY, 1999), but it is not used by deaf children (or is used poorly in the case of children with hearing residues and implants). This skill has been called phonological awareness by researchers (CAPOVILLA, 2000; MORAIS, 2012), being understood as a metalinguistic skill, therefore conscious and voluntary, which corresponds to the ability to analyze speech voluntarily, segment it into parts and manipulate these segments (CAPOVILLA, 2000).

Just as Vygotsky (1984) and Luria (1988) were interested in the path taken by children during their writing development process, Ferreiro (2001) also sought to investigate and demonstrate that children think about writing and that their thinking is coherent. From this perspective, children may formulate hypotheses and are creators of the instruments of their knowledge, as happens with those who are deaf, with the difference that, in this case, this process does not happen by the auditory pathway. Luria (1988) points out that the child follows a gradual path of symbol differentiation, noting in her analysis that she makes numerous attempts to develop primitive methods before understanding the meaning and mechanism of writing, emphasizing that it is the act that produces the understanding about the use of signs and not the other way around. Thus, considering that the path taken by the deaf for the appropriation of the written Portuguese language is not centered on the relation between writing and orality, according to Vygotskian assumptions, we sought to investigate and register what deaf children said about writing, describing how they used the letters and the words, and what they represented at that moment.

Deaf Literacy: offering the language

Basic literacy skills and literacy are terminologies of use linked to the context of teaching and the appropriation of the written language, even if they are given several meanings, sometimes in disagreement, but related to each other. The word literacy is currently used in different contexts, but it emerged in the educational field. Here, following researchers such as Rojo (2009), Street (2010) and Soares (2014), it is assumed that literacy is a set of social practices in connection with what people do and how they use reading and writing in different social, cultural and historical contexts, taking into account how these skills relate to values and needs in an assortment of literate practices. In this sense, literacy in deaf education is problematized, given the specificities of the deaf way of being and the linguistic and cultural issues that involve these subjects.

Literacy and the appropriation of the written language by deaf subjects have been a matter of concern for several researchers in the field – Gesueli (1998, 2015), Lebedeff (2010, 2017), Karnopp and Pereira (2015), Formagio and Lacerda (2016), among others –, provoking questions about strategies and methods to be used in the process of constructing Portuguese writing, considering that orality should not be a prerequisite for literacy of deaf people. For Gesueli (2015), in deaf education, the visual aspect is a fundamental factor for the appropriation of the written Portuguese language, requiring a distance from the notion of writing as representative of orality, moving away from a graphocentric conception of writing and considering the actions that take place with and about language as a discursive practice. From this perspective, visual literacy presents itself as a relevant factor in the educational process of deaf people, emphasize Gesueli and Moura (2006).

According to Lebedeff (2010), visual literacy is an area of study approached from various school subjects aiming to study the physical processes involved in visual perception, the use of technologies to represent the visual image and the development of strategies to understand what is seen. In this direction, and according to Gesueli (1998, 2015), Lebedeff (2010) points out that sign language, together with the production of a culture that is also visual and does not require sound, highlights the visual characteristic of the condition of deafness. In deaf education, experiences that favor visuality are part of the way of life and the deaf way of being, shared in the deaf community, enable access to visual strategies and understanding of the world based on practices that have visual literacy events as a starting point. By emphasizing that deaf people use different approaches from those used by hearers to learn the written language, practices that include visual literacy are suggested, which “needs to be understood, also, based on social and cultural practices of reading and image comprehension” (LEBEDEFF, 2010, p. 179).

Images are representations because they are created and produced by human beings in the societies in which they live, making it necessary to systematize and implement visual literacy for a greater understanding of information and experiences by the subjects, providing the skills for them to read the images and have a greater refinement of reading (DONDIS, 2015; SANTAELLA, 2012). In this context, Santaella (2012) emphasizes the need for the school to give the cognitive importance that the image deserves in the teaching and learning processes, as it is common for teachers to be still stuck with the idea that the verbal text is the great transmitter of knowledge, not considering the visual literacy of their students.

Taveira (2014), in his doctoral thesis, sought to fill in the gaps pointed out by Lebedeff (2010), investigating what would be the pedagogical practices arising from the discursive needs of the visual experience of deafness and to which literacy events these discourses refer. Taveira (2014) found the imagery appeal and the use of visual artifacts present in the pedagogical practice of deaf teachers, which added other looks to literacy, reading, writing and literary production, highlighting the visual issue by the need to read the image as text, as well as the visual cues they present. The author observed, in the classroom of deaf teachers, the presence of equipment for recording images and organizing the space, which she calls body extensions, namely: camera, camcorders, notebooks, computers, mobile phones, tablets and internet.

Even if deaf teachers and bilingual hearers use visual resources and strategies, such as didactic and educational videos in sign language, videos for dissemination, photographs with informational purposes, among others, Taveira (2014) verifies that there is no search for literacy or visual literacy. Still, there are signs and intuitions about working with deaf students using such resources and a way of teaching that is still being built, with disordered productions, not cataloged, even with the interaction among these teachers in social networks and other spaces. The visual experience should not only consist of intuitions in the strategies used by teachers in deaf education. It should occupy a central role in the education organization for these children.

Pedagogical practices, added to technological artifacts, enable the expansion of literacy to image and other semiosis fields, not just writing. It points to visual literacy practices and digital technologies before multimodal and multisemiotic resources, using deferred texts that can be written or video recordings, as Peluso (2018) highlighted. Figueiredo and Guarinello (2013) suggest the use of multimodal texts in the literacy of deaf people, and multimodality can involve several elements, such as written texts, colors, images, graphics, among other semiotic resources. In this sense, in the wake of Rojo (2009), Figueiredo and Guarinello (2013) postulate that multimodality opens up possibilities for the teacher to incorporate visual aspects to his practices to ensure interactions that enable the insertion of their students in literate practices.

Gesueli and Moura (2006) highlight the importance of considering the socio-cultural aspects of the deaf individual, the specificity of sign language and the written function as a result of discursive practices, being relevant to conceive literacy in deaf education as a multimodal process characterized by the use of more than one semiotic code, crossed by multiple-meaning codes.

In this context, this study investigates how deaf children who are signers of Libras make records at the beginning of schooling and what do they say about writing the Portuguese language?

Method

The research collaborators were six deaf children, signers of Libras, who attended Kindergarten or the early years of Elementary School in a school for the deaf located in Paranaguá, state of Paraná. The children were between 3 and 12 years old. Interviews were carried out and recorded on video. The language used for communication was Libras, a speech in the visual, gestural and spatial modality, signaled with the hands and containing grammatical facial expressions. As Libras is part of the object of the research, the need for video recording was not restricted to a methodological issue. The recording was part of the content of the investigation itself. Another fundamental aspect of video interviews concerns privacy and confidentiality: the participation of collaborators in the research was authorized through the Term of Free and Informed Consent, and the use of the image was granted through the Term of Assignment and Use of Image. Even though the legal guardians of the children have chosen to use their real names, in this article, the six collaborators were identified as A, B, C, D, E and F.

According to Kramer (2002), the child’s consent to participate in the interview was also obtained. In this way, all the requirements outlined in Resolution No. 510/2016 of the National Health Council, which regulates ethics in research with human beings, were fulfilled, and the entire procedure was approved in the opinion of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education of the University of São Paulo under nº 082/2017.

This is qualitative, descriptive and exploratory research, with the development and adoption, besides the interviews, of a set of procedures to collect data on how and what children say about writing. The interview was semi-structured, approaching a conversation, using a script to conduct the researcher’s actions, as pointed out by Lankshear and Knobel (2008), since it was a data collection conducted with young children.

In addition to the semi-structured interview, the children organized a set of activities to be carried out to collect the written and verbal data produced by them. According to Luria (1988), for children to write, things must represent some interest, such as the things they play with. The objects involved have an instrumental role in helping obtain another object. Thus, considering that the use of instruments such as children’s stories brings the researcher and the child closer together and may involve them through playful proposals, the script started from the telling of a children’s story in Libras, adapting the book Polly jean pyjama queen (Viviana, a rainha do pijama), by Steve Webb, which makes up the collection of complementary works of the National Programme for Books and Teaching Materials (Programa Nacional do Livro e do Material Didático [PNLD]).

The activity script was created from the storytelling so that the children could write words and texts, complete stories, develop characters, and draw pictures. Some studies use similar methods, such as a story to be completed and drawing with stories, in works by Cruz (2009) and Correa and Bucci (2018) researchers. They consider that such methods constitute successful strategies for data collection in surveys with this target audience.

As for the materials and strategies that were part of this research, imagery and multimodal resources were used, observing the motivation and interest of deaf children in participating in activities and in the information made available. The storytelling in Libras, through video resources, was an important strategy due to two factors: a) it had the function of telling the story, characterized as deferred textuality (PELUSO, 2014), showing itself as an action that can be successful in the literacy of deaf children; and b) there was linguistic identification with a deaf adult as a reference.

The written productions presented in this text are part of the script of activities that the children performed. Vocabulary writing is related to the animals that are characters in the book and others chosen by the children. In the writing of the text, in the letter genre, they elaborated response to Polly Jean’s birthday invitation.

The interviews were conducted in Libras, videotaped, translated and transcribed into Portuguese, featuring an interlingual and intermodal translation, considering that this process involves two languages of different modalities.

Results: the spoken word

Even though writing is a process that differs from speaking in many aspects, it is essential to emphasize that writing, when representing speech, represents the spoken language orally. Thus, for Soares (2016), the essence of alphabetic writing is this conversion of sounds into letters. The alphabetic writing system was created based on oral language to represent speech. In this context, the fact that the learning process of Portuguese language writing by the deaf person is established as the learning of a writing system that represents a language whose modality (oral) is not accessible or is little affordable. The research shows that the difficulties in the appropriation of writing by the deaf are not only related to the fact that the Portuguese language is configured as a second language but to the fact that there is an alphabetic writing system whose constitution and function are based on the representation of the oral language to be registered. Therefore, it is necessary to problematize what is used as a reference to teach Portuguese writing to deaf people.

Given the above, it is pertinent to reflect on the role of the linguistic sign and its referent in the use of language by deaf people. A reference, according to Cardoso (2003, p. 1), is “the relationship between language (a saying) and an exteriority (a non-saying), a necessary relationship for language to have its value and not end up in itself”.

On the other hand, according to Vygotsky (1984), writing is independent of speech development, and children can learn to write without this action being linked to speech. According to Silva (2008), the hearing child overcomes the abstract condition of the word when he appropriates the meaning present in the combination of sounds specific to each word. However, the deaf child, sign language signer, will only do so through visual perception, when (or if) she appropriates the meaning enabled by the combination of movements that make up each sign of Libras, converting to a writing system of an alphabetic language that has no structural relation with the language used by that child.

In this context, some forms of records were evidenced by the deaf children, which are arranged below, presenting the vocabulary (a) and texts (b) productions of each collaborator:

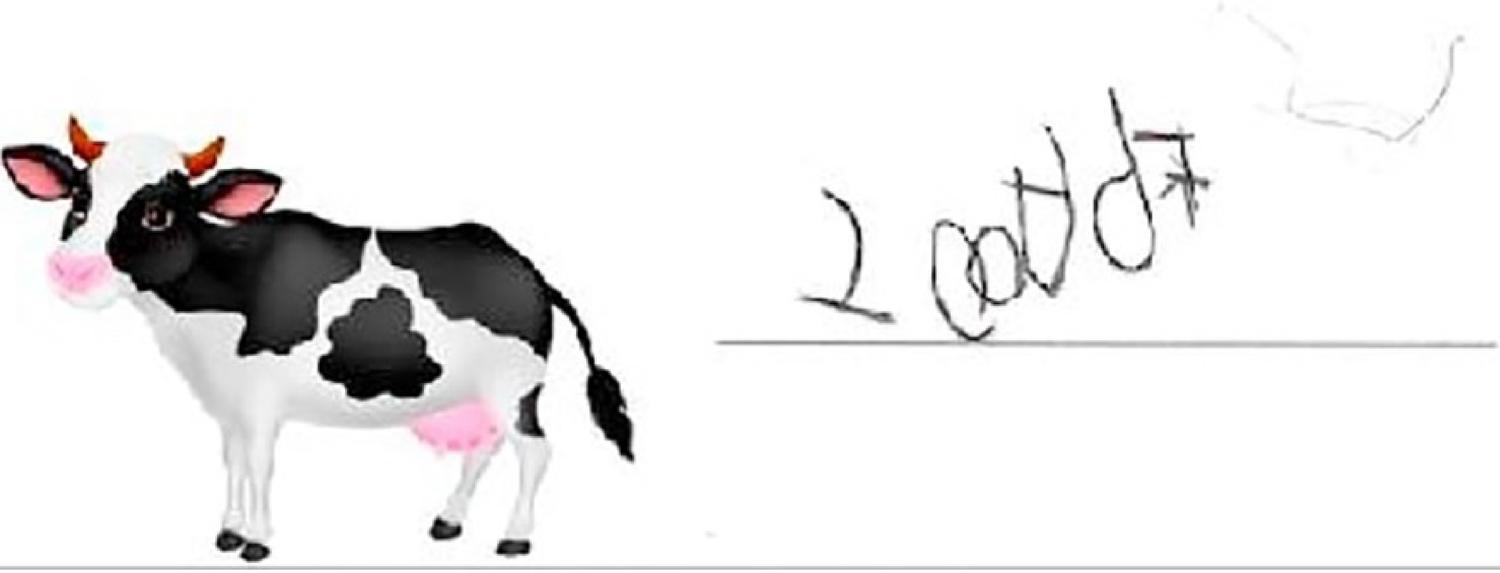

Child A, Kindergarten, 3 years old: a) She registered words containing letters mixed with numbers, with most of the letters being part of his name. In most vocabulary writing, she drew pictures, outlining the represented objects (Figure 1 illustrates a child’s production). b) In the writing of the text, she drew, as she had done in the vocabulary, making no distinction between the production of the text and the writing of words, mobilizing the same resources.

Such productions are age-appropriate for deaf and hearing children.

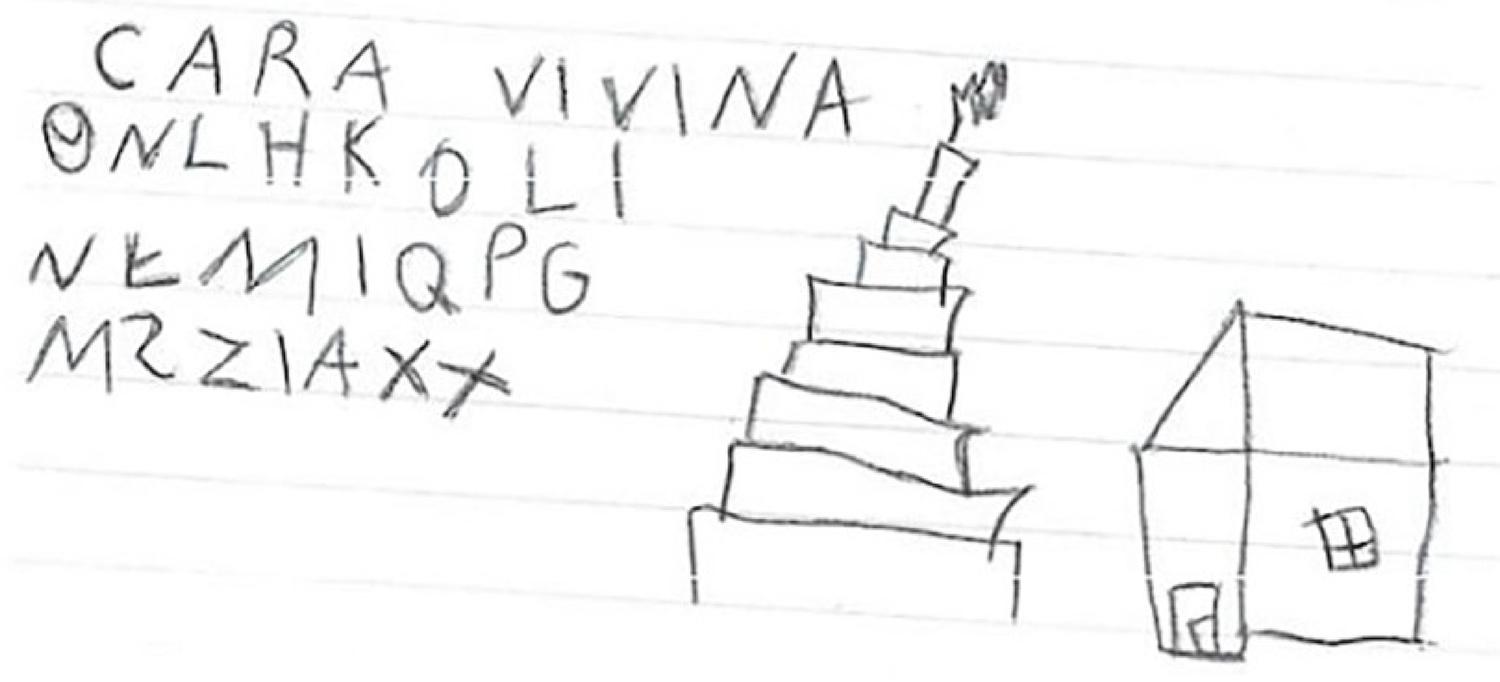

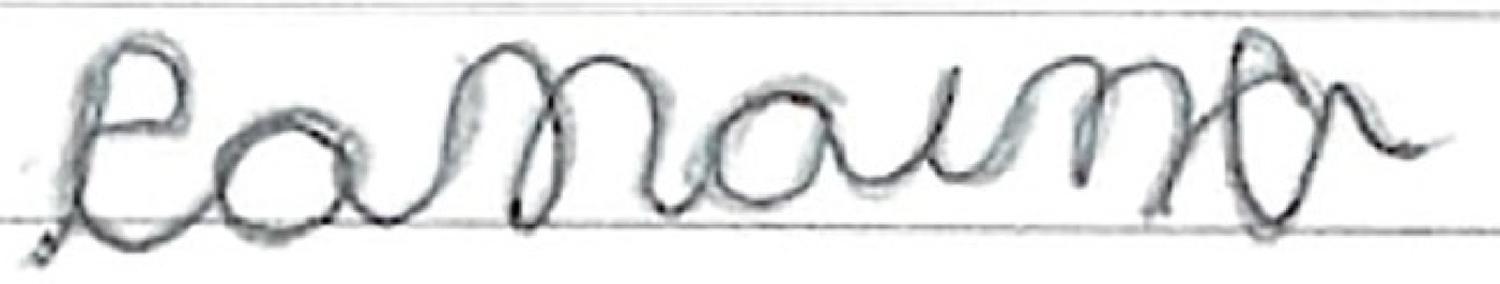

Child B, Kindergarten, 5 years old: a) She registered words using the letters of her name, sometimes adding other letters. The written words did not repeat the ordering and combination of letters, as shown in Figure 2. b) The text was produced by scribbling imitating the shapes of cursive letters, with pictographic features recorded differently from the vocabulary. The writing was used externally, not characterizing as a memory resource.

Source: Research data.

Figure 2 – Writing the names of animals, characters from the book, produced by child B

These productions are also consistent with the age group of deaf and hearing children.

Child C, 2nd degree, 9 years old: a) She registered words using randomly several letters of the alphabet, in capital letters, without making use of the properties of the alphabetic writing system. The writing was not used as a memory resource, from which the child could remember what he had already written. b) The text was produced with different letters, without using the properties of alphabetic writing, as performed in the writing of words. These productions failed to register ideas and concepts, characterized as the instrumental use of pictographic drawing to complete the information of the textual production (Figure 3). In vocabulary writing, the recording of drawings was not identified.

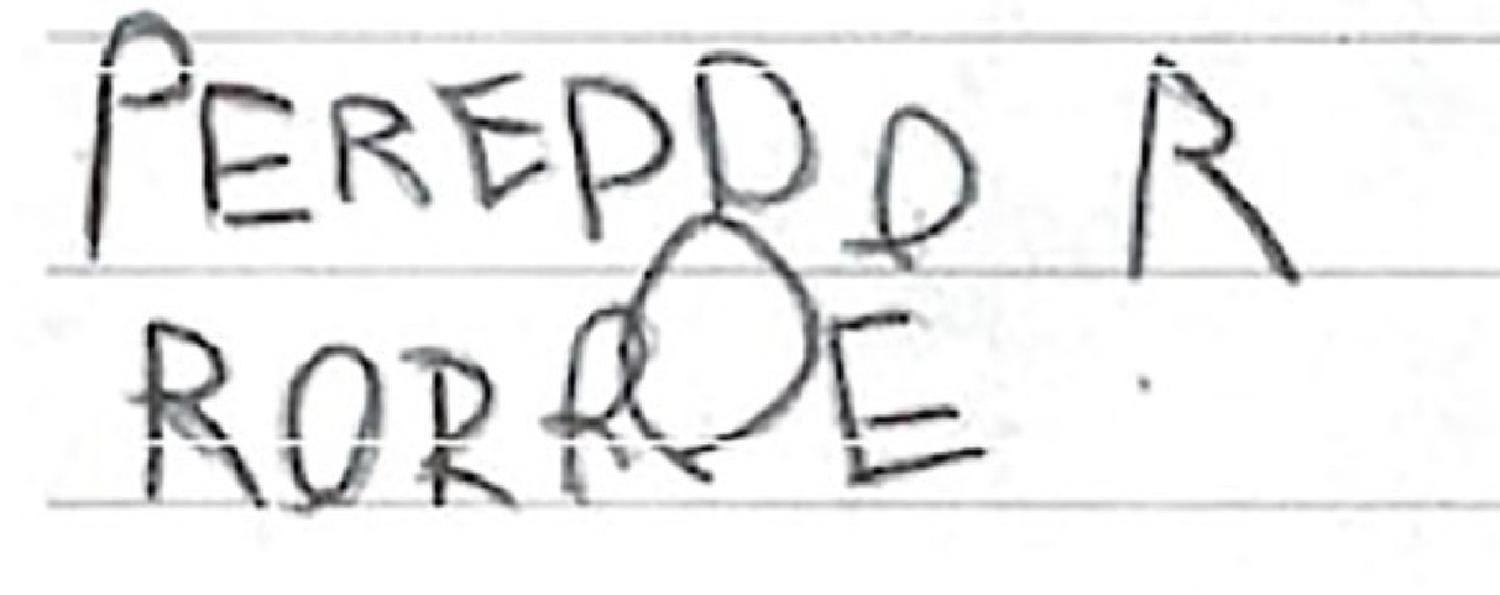

Child D, 5th degree, 12 years old: a) She evidenced the registration of stable words, with writing performed in cursive letters, even if in the learning phase of its shapes, as shown in Figure 4. b) Text produced through scribbles, imitating the forms of cursive letters, with elements similar to words that were stable for the collaborator.

Source: Survey data

Figure 4 – Writing the name of an animal, character from the book, produced by child D with stable words

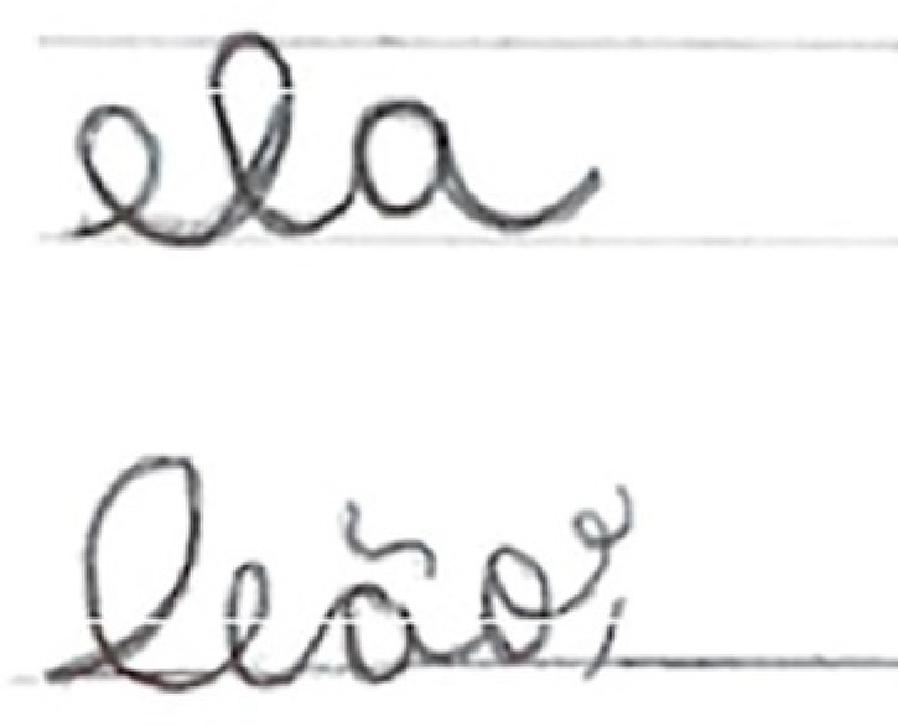

Child E, 3rd degree, 8 years old: a) She recorded some words in the cursive letter, using alphabetical properties and following visual cues for writing (Figure 5). b) The text was produced with several letters registered randomly in cursive, completing one or two sheet lines without spacing between them. Textual production performed differently from the vocabulary record.

Source: Research data.

Figure 5 – Attempts to write the word “leão” (lion) following visual cues produced by the child E

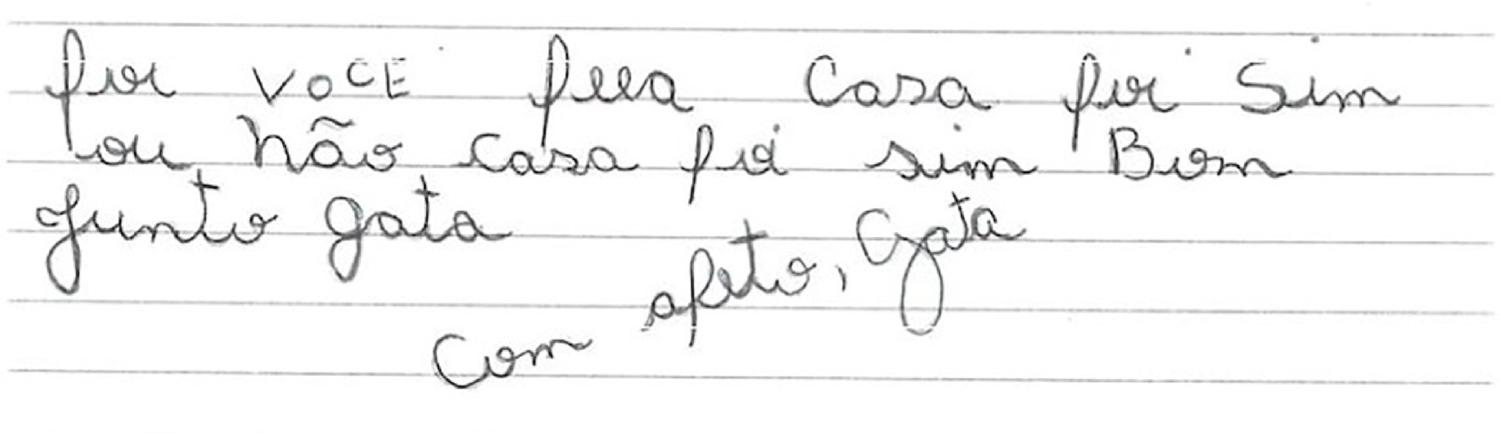

Child F, 5th degree, 11 years old: a) She registered writing symbolically and conventionally when she knew the word to be recorded, evidencing the use of writing as an instrument for memory. When she did not know the spelling of a particular word, she used visual cues to record it. b) The text was produced with conventional symbolic writing, recording ideas and concepts, however, with characteristics of writing in a second language, as is usual in texts produced by deaf people, as shown in Figure 6. The text was recorded with the linguistic structure of sign language, not containing the connectives and the nominal and verbal agreement, as presented in the syntax of the Portuguese language.

Discussion and conclusions

There are many challenging aspects in research involving young children, especially concerning data collection and generation involving written productions in Portuguese. The children excitedly told things in Libras, but when they were asked to write, there was a reaction of estrangement, denial or doubt, with lesser or greater intensity, depending on the collaborator.

When the written productions were analyzed, it became evident that there is a crucial point, a divider in the writing development process of deaf children in relation to hearing children, which was called in this work the “turning point”. First, it was found that deaf children, in the phase equivalent to what Luria (1988) calls the prehistory of writing, and at the beginning of its appropriation, record words and texts in the same way as hearing children, making use of primitive writing, so that the act of writing seems dissociated from the object, with the registration of pictographic drawings in a self-contained or instrumental way, using known letters and numbers and creating hypotheses about the writing they perform. Therefore, there is no initial distinction between the process of appropriation of the written Portuguese language for hearing and deaf children, even if this is not the language used by the deaf child as a language of interaction and instruction.

At this stage of writing development, deaf children used pictographic writing; recorded words using the letters of their names, with internal variations and different combinations; recorded words using randomly several letters of the alphabet, in capital letters, without making use of the properties of the alphabetic writing system; and also used stable words for them. Such strategies are found in the writing development process of hearing children (FERREIRO; TEBEROSKY, 1999, LURIA, 1988; MORAIS, 2012). However, these forms of writing start to differentiate from deaf children when hearing children begin to relate sound to spelling (FERREIRO; TEBEROSKY, 1999) and use instrumental writing (VYGOTSKY, 1984). This is the moment when the child begins to understand the mechanism of writing and records the denoted object, characterizing the “turning point” for the hearing children, but not for the deaf child, since the correspondence between speech and spelling is effected by the auditory pathway.

In the case of the hearing child, according to Ferreiro and Teberosky (1999), this moment emerges when the correspondence between the speech and the spelling is made, dissociating it from its meaning and segmenting it, in the domain of a metalinguistic skill; that is, phonological awareness is essential for the development of writing in the hearing child. Soares (2016, p. 166, emphasis added) emphasizes that the child’s insertion in the world of writing is constituted by the

[...] understanding writing as a visual representation of the sounds that make up the sound chain of speech - writing as the speech made visible - and learning the system and rules of relations between the phonemes that make up the spoken word and the graphemes that represent them.

In studies with hearing children, for Luria (1988), the turning point is evident in the use of instrumental writing, in its use as a support for intellectual functions as a requirement for the use of the conventional system. Likewise, Vygosty (1984) states that the child uses writing as a second-order symbolism when understanding the creation of written signs to represent the spoken symbols of words, understanding that speech can be “drawn”. However, it is worth remembering that signs change; they are not static.

As second-order symbols, written symbols function as designations for verbal ones. Understanding of written language is first effected through spoken language, but, gradually this pathway is curtailed, and spoken language disappears as an intermediary link. To judge from all available evidence, written language becomes direct symbolism that is perceived in the same way as spoken language. (VYGOSTY, 1984, p. 131-132).

Once the importance of understanding the written language through the spoken language is evidenced, either as a representation system or as an instrument to support memory, the “turning point” in writing development by deaf children in the appropriation of the written Portuguese language is questioned since for them learning does not depend on speech development. In the case of deaf people, it is noteworthy that the specificities are not only related to the development of speech but also the lack or impossibility of accessing the spoken language (to sounds). Besides, it is considered that the deaf are users of another language, which is neither oral nor auditory, classified as a modality different from that used by the hearing people.

However, in the data produced in this investigation, it was found that there is a period in which the deaf child begins to realize that writing records a specific denoted object. However, she still does not understand the logic of the alphabetic writing mechanism, unlike the child who begins to establish a relation between the sounds and words. It was demonstrated that the child perceives or assumes a logic to write, but she does not know what it is and is insecure when making his records, as seen in interviews with most children. It is important to emphasize that, even in this context, they began to use strategies that pointed out visual clues in writing; for example, when one of the collaborators already knew how to register some animal names but had doubts about how to write others, recording LEIO instead of “leão” (lion), JOUOVOPO for “jacaré” (alligator), MACOCOCA instead of “macaco” (monkey) and UREO for “urso” (bear). In these situations, it is possible to say that the collaborator used the visual cues of the spelling of the words. Her attempts are not related to the syllabic hypothesis, as she does not use the auditory pathway but rather the visuality of the words. The use of words they already know, which contain letters in common with the object to be denoted and/or the registration of pseudowords (PEREIRA, 2015), are some of the visual clues used by the collaborators of this research.

This is considered an essential point in developing deaf subjects’ writing. One of the hypotheses is that children begin to perceive the visual clues in the spelling of the word and then start to copy the words, make conjectures and attempts of writing through mental activities related to visual awareness (OLIVEIRA, 2009). The concept of visual awareness, proposed by Oliveira (2009), seeks to establish a relation between the idea conveyed and the written record. Children build knowledge from the internal representation in sign language and, later, in writing, using the alphabetical base by appropriating graphical images. Thus, visual awareness can be understood as a mechanism that aims at: “[…] visual representation of the object - the image; the abstraction of the object as a unit made up of parts, resulting in the symbolic representation of the object, through sign language and subsequent alphabetic writing” (OLIVEIRA, 2009, p. 196).

In the textual productions of children involving the letter genre, it was found that some of these records were carried out in a very different way from the way they wrote the words in the vocabulary activity. It was evident that, based on the assumption witnessed in the productions of children B, D and E, the text presents itself as something distinct, larger and more complex, as a tangle of letters together, without separation. In the textual production of child F, it was found that the collaborator made use of writing to record ideas and concepts. However, there were still characteristics of the deaf text; that is, the text was written using a Libras syntactic structure, with the omission of articles and prepositions, inadequate use or absence of connectives in Portuguese and not in Libras, among others, as presented by Brochado (2003).

However, a novel fact emerged: the recording in SignWriting4 by collaborator F, indicating that this way is more manageable for her, relating it to Libras as a language that gives meaning to things. Silva (2008) found in his research that the attempt to graphically represent the signs that make up Libras can be seen as a creative and sophisticated manifestation of the higher psychological functions of deaf children, considering that the graphic recording of signs, visually captured by these children in sign language, is characterized as the representation of the sound rhythm, evidenced by the hearing child in her writing appropriation process.

In deaf education, from the perspective of the language in use, in the teaching of language as knowledge and production, according to Lebedeff (2010), deafness exists and involves the use of a language that is visual and spatial and, therefore, needs a pedagogical proposal designed for its linguistic and cultural singularities that is not a mere adaptation of practices for hearers, but practices that involve visual literacy for learning a second language and another linguistic modality. For Machado (2000), the image is an essential symbolic system in the lexical-semantic comprehension process of the written language by deaf people. Still, the need to understand the child’s relation between text and image is highlighted. Recalling that, according to Dondis (2015), the visual mode constitutes a data body that can be used to compose and understand messages for various purposes at various levels.

The strategies and conjectures that children make alone to write are important. However, unlike sign language acquisition – which happens naturally in contact with their peers – writing is only learned through systematic teaching and, culturally, through mediation (LURIA 1988; VYGOTSKY, 1984). In activities involving visual literacy, following Dondis (2015), Taveira (2014) and Lebedeff (2017), the perception of the visual representation of the image should not be understood as an innate ability of subjects, regardless of whether they are deaf or hearing and, therefore, in carrying out a pedagogical work, the visual experience should not only be part of the intuitions of teaching practices. There is a need to organize the work involving visual literacy for a greater understanding of information and experiences by the subjects, providing skills so that they can read the images and have a greater refinement of reading. Given the above, the mediation of the teacher becomes essential.

In addition to different strategies that contemplate the visuality of deaf children, Gesueli (1998) already pointed out the importance of the narrative construction process so that the deaf child learns to use language, assuming active roles in the dialogue, mainly because the majority came from a family of hearers, not having a favorable linguistic context for this to happen in the family environment.

This way reflects the possibilities of actions contributing to the “turning point” in the appropriation of writing by deaf children. Initially, it is considered important to conceive that these children’s literacy is constituted on different bases from those used in teaching the written language to hearing children. These differences must be related to experiences based on bilingual and visual assumptions, imposing the need to use strategies that problematize the following question: how can a deaf person understand the writing system without constructing phonological awareness through the auditory pathway?

If the same conceptual apparatus of hearing children is used in the literacy of deaf people - things that they are already used to in teaching other children -, there will be a comparison of the writing appropriation of deaf and hearing children, and there will undoubtedly be a distortion of the reality. From this perspective, it is pertinent to have an “ex-position” (LARROSA, 2015), leaving behind assumptions and writing practices that guided and continue to guide the deaf textual productions and, according to Veiga-Neto and Lopes (2010), to think differently about the literacy of the deaf, thinking outside of what is given and has already been thought of, in the sense of not assuming the bases on which this already given, in this way, leaving what has already been thought for behind.

In this context, given the investigation results, bilingual literacy is pointed out as a hypothesis to contribute to the “turning point” of the deaf child. Bilingual literacy is understood as a set of pedagogical practices that involve specificities of Libras and Portuguese language in the writing appropriation process, such as:

Sign writing: this hypothesis is based on data collected in the interview with collaborator F. By using signwriting, the child related the records to sign language, producing meaning and attesting that the signs of Libras could be recorded in her language, in the same perspective found in the research by Lima, Alves and Stumpf (2018), which may contribute to the acquisition of new mechanisms for abstraction in the appropriation of the written language.

Deferred writing: the hypothesis of deferred writing is based on the concept of deferred textuality (Peluso, 2014, 2018), which includes the use of video resources and production of signed narratives, such as storytelling in Libras and videos of each child recorded with a smartphone in this survey at the end of each interview. These video productions work like a deferred text, having a structure and function like written text. Videos produced in Libras can be understood as the “speech” of the deaf made visible, as pointed out by Soares (2016) concerning the appropriation of the written language by the hearing child.

Bilingual writing: this hypothesis involves the interlinguistic and intermodal aspects of the deaf person’s writing, as verified in the text in Portuguese written by collaborator F. This textual production is composed with the linguistic structure of sign language, whose specificities are common in texts written in Portuguese by deaf people (BROCHADO, 2003), in a second language perspective (SOUZA et al., 2016).

In this sense, an initial action that should be considered is the problematization of what is the object to be taught and what is being taught when teaching the written Portuguese language to deaf people. For Soares (2016, p. 25, emphasis added), “[…] literacy methods have always been the issue because they derive from different conceptions about the object of literacy, that is, about what is taught when teaching the written language”. In the case of deaf education, the teaching of the written Portuguese language is related to the writing of a second language and learning a writing system that represents the orally spoken language, to which the deaf person has little or no access.

Therefore, the results of this investigation, in line with Larrosa (2015), open the possibility of breaking with what has been stated and is no longer admitted, opening spaces and questions for new ways of thinking in deaf education towards novel research that could deepen – characterizing and questioning – the “turning point” in the appropriation of the Portuguese language written by deaf children.

REFERENCES

BROCHADO, Sônia Maria Dechandt. A apropriação da escrita por crianças surdas usuárias da língua de sinais brasileira. 2003. Tese (Doutorado em Letras) – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Assis, 2003. [ Links ]

CAPOVILLA, Alessandra Gotuzo Seabra. Leitura, escrita e consciência fonológica: desenvolvimento, intercorrelações e intervenções. 2000. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia) – Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2000. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, Silvia Helena Barbi. A questão da referência: das teorias clássicas à dispersão de discursos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2003. [ Links ]

CORREA, Bianca Cristina; BUCCI, Lorenzza. A vivência em uma pré-escola e as expectativas quanto ao ensino fundamental sob a ótica das crianças. Jornal de Políticas Educacionais, Curitiba, v. 12, n. 9, p. 1-20, 2018. [ Links ]

CRUZ, Rosimeire Costa de Andrade. A pré-escola vista pelas crianças. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPED, 32., 2009, Caxambu. Anais […]. Rio de Janeiro: Anped, 2009. Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/gt07-5619-int.pdf. Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

DONDIS, Donis A. Sintaxe da linguagem visual. Tradução Jefferson Luiz Camargo. 3. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2015. [ Links ]

FARACO, Carlos Alberto. Linguagem escrita e alfabetização. São Paulo: Contexto, 2012. [ Links ]

FAVORETO DA SILVA, Rosane Aparecida. Experiências de crianças surdas com a palavra escrita. 2020. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2020. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, Emilia; TEBEROSKY, Ana. Psicogênese da língua escrita. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1999. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, Emilia. Cultura escrita e educação. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2001. [ Links ]

FIGUEIREDO, Luciana Cabral; GUARINELLO, Ana Cristina. Literatura infantil e a multimodalidade no contexto de surdez: uma proposta de atuação. Revista Educação Especial, Santa Maria, v. 26, n. 45, p. 175-193, 2013. [ Links ]

FORMAGIO, Carolina Lima Silva; LACERDA, Cristina Broglia Feitosa de. Práticas pedagógicas do ensino de português como segunda língua para alunos surdos no ensino fundamental. In: LACERDA, Cristina Broglia Feitosa de; SANTOS, Lara Ferreira dos; MARTINS, Vanessa Regina de Oliveira (org.). Escola e diferença: caminhos para a educação bilíngue de surdos. São Carlos: UFSCar, 2016. p. 169-241. [ Links ]

GESUELI, Zilda Maria. A criança surda e o conhecimento construído na interlocução em língua de sinais. 1998. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1998. [ Links ]

GESUELI, Zilda Maria. A escrita como fenômeno visual nas práticas discursivas de alunos surdos. In: LODI, Ana Claudia Balieiro; MELO, Ana Dorziat Barbosa de; FERNANDES, Eulalia (org.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2015. p. 173-186. [ Links ]

GESUELI, Zilda Maria; MOURA, Lia de. Letramento e surdez: a visualização das palavras. ETD: Educação Temática Digital, Campinas, v. 7, n. 2, p. 110-122, 2006. [ Links ]

KARNOPP, Lodenir Becker; PEREIRA, Maria Cristina da Cunha. Concepções de leitura e de escrita e educação de surdos. In: LODI, Ana Claudia Balieiro; MELO, Ana Dorziat Barbosa de; FERNANDES, Eulalia (org.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2015. p. 125-134. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Sonia. Autoria e autorização: questões éticas na pesquisa com crianças. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 116, p. 41-59, 2002. [ Links ]

LANKSHEAR, Colin; KNOBEL, Michele. Pesquisa pedagógica: do projeto à implementação. Tradução Magda França Lopes. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2008. [ Links ]

LAROSSA, Jorge. Tremores: escritos sobre experiência. Tradução Cristina Antunes e João Wanderley Geraldi. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2015. [ Links ]

LEBEDEFF, Tatiana Bolívar. Aprendendo a ler “com outros olhos”: relatos de oficinas de letramento visual com professores surdos. Cadernos de Educação, Pelotas, n. 36, p. 175-195, 2010. [ Links ]

LEBEDEFF, Tatiana Bolívar. O povo do olho: uma discussão sobre a experiência visual e surdez. In: LEBEDEFF, Tatiana Bolívar (org.). Letramento visual e surdez. Rio de Janeiro: Wak, 2017. p. 226-251. [ Links ]

LIMA, Marleide Francisco de; ALVES, Edneia de Oliveira; STUMPF, Marianne Rossi. Escrita de sinais: uma proposta para o letramento de surdos em L1. Revista Prática Docente, Confresa, v. 3, n. 1, p. 140-157, 2018. [ Links ]

LURIA, Alexander Romanovich. O desenvolvimento da escrita na criança. In: VIGOTSKII, Lev Semenovich; LURIA, Alexander Romanovich; LEONTIEV, Alex N. (Org.). Linguagem, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem. Tradução Maria da Penha Villalobos. São Paulo: Ícone: USP, 1988. p. 143-189. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Edna de Lourdes. Psicogênese da leitura e da escrita na criança surda. 2000. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia da Educação) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2000. [ Links ]

MORAIS, Artur Gomes de. Sistema de escrita alfabética. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2012. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Marta Kohl de. Pensar a educação: contribuições de Vygotsky. In: CASTORINA, José Antonio et al. Piaget-Vygostky: novas contribuições para o debate. Tradução Claudia Schilling. 6. ed. São Paulo: Ática, 2000. p. 51-83. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Thereza Cristina Bastos Costa de. A escrita do aluno surdo: interface entre a libras e a língua portuguesa. 2009. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, 2009. [ Links ]

PELUSO, Leonardo. Los sordos, sus lenguas y su textualidad diferida. Traslaciones, Mendoza, v. 5, n. 9, p. 40-61, 2018. [ Links ]

PELUSO, Leonardo. Textualidad diferida y videograbaciones en LSU: un caso de política linguística. Revista Digital de Políticas Lingüísticas, Córdoba, v. 6, n. 6, p. 16-37, 2014. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Maria Cristina da Cunha. Reflexões sobre a aquisição da escrita da língua portuguesa por criança surda usuária da língua brasileira de sinais. Revista Espaço, Rio de Janeiro, n. 43, p. 239-263, 2015. [ Links ]

ROJO, Roxane. Letramentos múltiplos, escola e inclusão social. São Paulo: Parábola, 2009. [ Links ]

SANTAELLA, Lucia. Leitura de imagens. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2012. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tânia dos Santos Alvarez da. A aquisição da escrita pela criança surda desde a educação infantil. 2008. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2008. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Alfabetização: a questão dos métodos. São Paulo: Contexto, 2016. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Letramento: um tema em três gêneros. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2014. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Regina Maria de et al. Relatório do grupo de trabalho para analisar e propor a implantação da estrutura adequada para atender ensino de Libras e demais questões correlatas. In: LINS, Heloísa Andreia de Matos; SOUZA, Regina Maria de; NASCIMENTO, Lilian Cristine Ribeiro do (org.). Plano nacional de educação e as políticas locais para implantação da educação bilíngue para surdos. Campinas: Unicamp, 2016. p. 1-28. [ Links ]

STREET, Brian V. Os novos estudos sobre o letramento: histórico e perspectivas. In: MARINHO, Marildes; CARVALHO, Gilcinei Teodoro (org.). Cultura escrita e letramento. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2010. p. 33-53. [ Links ]

STUMPF, Marianne Rossi. Sistema signwriting: por uma escrita funcional para o surdo. In: THOMA, Adriana da Silva; LOPES, Maura Corcini (org.). A invenção da surdez: cultura, alteridade, identidade e diferença no campo da educação. Santa Cruz do Sul: Unisc, 2004. p. 143-159. [ Links ]

TAVEIRA, Cristiane Correia. Por uma didática da invenção surda: prática pedagógica nas escolas-piloto de educação bilíngue no município do Rio de Janeiro. 2014. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2014. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, Alfredo; LOPES, Maura Corcini. Para pensar de outros modos a modernidade pedagógica. ETD: Educação Temática Digital, Campinas, v. 12, n. 1, p. 147-166, 2010. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev Semenovich. A formação social da mente. Tradução José Cipolla Neto, Luis Silveira Menna Barreto e Solange Castro Afeche. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1984. [ Links ]

3- Search carried out on the websites of the Capes Theses and Dissertations Bank and Capes Periodicals containing the following keywords and respective operators: Surd*(deaf) AND “Língua Portuguesa” (Portuguese language) AND escrita (writing), in a period of 10 years (2009-2018).

4- According to Stumpf (2004), the SignWriting system, for writing signs, represents gestural units, not semantic units, so it can be applied to any sign language of the deaf.

Received: June 04, 2020; Accepted: August 05, 2020

texto em

texto em