Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 29-Abr-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248238149por

ARTICLES

Education and the female condition in a treatise by Alexandre de Gusmão written in the Portuguese America in the late 17th century*

1- Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, RS, Brasil.Contacts: fernandoripe@yahoo.com.br; gianalangedoamaral@gmail.com

In this paper we present an analysis of the discourses about education and the female condition present in the work Arte de crear bem os filhos na Idade da Puericia [Art of raising children well at the age of childhood]. Written in the Portuguese America, but initially published in Portugal in 1685, the work by the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Gusmão (1629-1724) assigned its last chapter, “Of the special care that must be taken in raising girls”, to address the warnings necessary for the good upbringing of girls. In the context of production of the educational work proposed by Alexandre de Gusmão, we want to propose the analysis of a set of statements that put in evidence a kind of ordering of the living conditions and educational guidelines of female children. We infer that the propagation of works of a moralist nature in the Luso-Brazilian space between the 17th and 18th centuries enabled the circulation of such enunciative orders, significantly influencing the social behavior of the time. From a historical and philosophical perspective, mainly through Foucauldian theoretical references, we understand that the work was an efficient mechanism that acted in the discursive constitution on specific models of education to guarantee the production of a certain type of female child subject. Notably, we identified two regulations that warned about the good upbringing of Christian girls through the practices of guardianship and retreat.

Key words: History of education; Alexandre de Gusmão; Female education; Childhood

Neste artigo apresentamos uma análise dos discursos acerca da educação e da condição feminina presentes na obra Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia. Escrita na América Portuguesa, mas publicada inicialmente em Portugal no ano de 1685, a obra de autoria do padre jesuíta Alexandre de Gusmão (1629-1724) destinou seu último capítulo, “Do especial cuidado que se deve ter na criação das meninas”, para tratar das advertências necessárias à boa educação de raparigas. No contexto de produção da obra educativa proposta por Alexandre de Gusmão, queremos propor a análise de um conjunto de enunciados que colocam em evidência uma espécie de ordenamento das condições de vida e das orientações educativas de sujeitos infantis femininos. Inferimos que a propagação de obras de cunho moralista no espaço luso-brasileiro entre os séculos XVII e XVIII possibilitou a circulação de tais ordens enunciativas, influenciando, significativamente, o comportamento social da época. A partir de uma perspectiva histórica e filosófica, principalmente através de referenciais teóricos foucaultianos, entendemos que a obra foi um eficiente mecanismo que atuou na constituição discursiva de modelos específicos de educação para garantir a produção de um determinado tipo de sujeito infantil feminino. Notadamente, identificamos duas normativas que advertiam sobre a boa criação das meninas cristãs através das práticas de guarda e recolhimento.

Palavras-Chave: História da educação; Alexandre de Gusmão; Educação feminina; Infância

Introduction

The shaping of a female education in the modern West was, to a large extent, based on the representations that women occupied in the male imagination. In such a way that, during the Brazilian colonial period, the ideal representation of a woman was that of an honorable and devout woman, whose functions were focused on the home and family reproduction (ALGRANTI, 1993). Roughly speaking, the honorable woman would be the one “who controls her bad instincts and, demurely, hides her body, aware of the passions she is capable of unleashing […]. She represses her sexuality and transforms it into a procreative function” (ALGRANTI, 1993, p. 120). In Portuguese America, convents and retreats were the main institutions for the search for asylum, protection, devotion, pension and education for women who intended to guarantee their honor, expand their faith, extol the Catholic Christian values and develop within these spaces the learning of reading and, when possible, writing and manual works.

In colonial historiography, the topic of women’s education, through the establishment of enclosures and shelters, has attracted the attention of researchers2. However, the educational process for girls, involving broader aspects than the acquisition of reading and writing practices – first letters –, is not often addressed3. The analysis of other typologies from sources other than the regulations of retreats and convents and colonial administrative letters can make possible other historiographical approaches to educational practices, conditions, norms and rules of female social behavior – often available in civility manuals or in religious literature published at the time.

In this sense, we propose to focus on the analysis of discourse of social behavior treaties published and/or that circulated in the Luso-Brazilian space, between the 17th and 18th centuries, and that acted discursively in the production of a certain type of modern child subject. However, we have identified the occurrence of statements about education and the possible conditions for the female child gender that indicated, through edifying discourses, the requirement of an “ancient normative background that came to remember the disciplinary requirements to which the body should be subjected, and those of an institution that they reveal so that it could remain as such” (COURTINE, 2013, p. 14).

In this text, we will analyze the work of the Portuguese Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão, Arte de crear bem os filhos na Idade da Puericia, which was written in Portuguese America and published in Lisbon in 1685. This book is divided into two parts: the first one contains 19 chapters that guide the theological foundations for “good education”; in the second part of the work, entitled “How parents should be involved in raising boys”, the 25 chapters prescribe practical and edifying advice for parents to educate their children. Throughout 387 pages, the author developed teachings that were repeated several times, either through the demonstration of exemplary models, or through frightening representations, or even through the incitement to punishment and punishment as a corrective and disciplining way of good upbringing. Although his attention was focused on the formation and education of boys, Gusmão, in the last chapter of his work, consisting of ten pages and entitled “Of the special care that must be taken in the upbringing of girls”, he presents warnings necessary for the good upbringing of girls.

Elomar Tambara and Gomercindo Ghiggi (2000) edited a facsimile version of this work, in which they call the reader’s attention to the fact that the treatise perceives Jesuit education as a faithful maintenance of the traditional model of the Ratio Studiorum. For Tambara and Ghiggi, Priest Alexandre de Gusmão had as a discursive strategy all care to please God, so that this Catholic religiosity made some themes emerge such as the good and correct food, how to dress, the games and the ones accepted, concern for rejected boys, good morals, manners and habits socially accepted as organizing principles of the family and the republic.4

The researchers Renato Venâncio and Jânia Ramos (2004), when prefaced to another reprint of the work we are analyzing, alerted to the debate about the importance of childhood in ecclesiastical literature, which took place in an attempt to generalize, to the children’s world, the rigor and the discipline used until then in the strict and normative projects of convents and monasteries. It is worth noting that, in this period, the way education was thought of was equitable to the model of training children, whether through home education employed by masters, tutors, aides and preceptors, as in the internal form established in monasteries and religious convents. However, these models were used, almost exclusively, for the most socially wealthy, who, in contrast to those who had, in their social relationships, some form of proximity, could also have access to the knowledge and ways of living the court. It is also worth noting that the Arte de crear bem os filhos na Idade da Puericia is part of a set of works that integrate a pattern used by many disciples of Saint Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556). A narrative typology that intended to “frame in a religious, moral and spiritual perspective” a Christian society, massively of peasant habits and behaviors, but that “investing in a strategy of expansion of knowledge, conditioned by a precise program of ideological affirmation, adequate to the growing complexity of the world, through the use of specific techniques” configured modes of behavior closer to nobility (SANTOS, 2004, p. 581).

Alexandre de Gusmão (1629-1724), born in Lisbon, moved to Rio de Janeiro in his teens. At the age of 17 he joined the Ignatian Order, having initially served as a minister after having studied Philosophy and Theology at Colégio da Bahia. Considered a “particular genius” for the government, as well as being a “very learned writer”, the Jesuit was sequentially promoted to various positions of the Order’s Religion in the province. He served as Master of Humanities, Master of Novices, Vice-Rector and Rector of some Colleges of the Society (LEITE, 1949; MACHADO, 1741; ROCHA PITTA, 1950).

Some studies, such as those by O’Neill and Domínguez (2001), Arnaut Toledo and Araújo (2009) and Arnaut Toledo and Barboza (2015), consider the Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão the first pedagogue in Brazil. This precedent title does not refer only to the fact that he was the first author to write works of an educational nature for children, still in the colonial period,5 but to his role in the evangelizing project established by the Society of Jesus in a large part of the occupied territory in the main colony, as well as his important role in the foundation of the Belém da Cachoeira Seminary, in Bahia. This Seminar was described in the words of Serafim Leite (2004, p. 241) as an institution with markedly popular characteristics, due to “in it, the children of the residents are raised, especially the poor, who lived in the sertão, and they can study not only the first elements of reading and writing, but also Latin and music”. Counting on the counterpart of the Portuguese Crown and on private collaboration, the Belém Seminary played an important role in the formation of missionaries of the Society of Jesus and in the educational process of literate subjects in the Recôncavo Baiano (SOUZA, 2015).

The treaty written by Gusmão is considered the first work written in Brazilian lands that aimed to present a pedagogical model to educate children through good Christian morals. The meaning given to education is very similar to the artisanal work that configures the pedagogical transmission of a preceptor, tutor, religious, or, in this case, a possible Jesuit missionary to shape youth in the constancy of the “real path of God’s commandments” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 27).

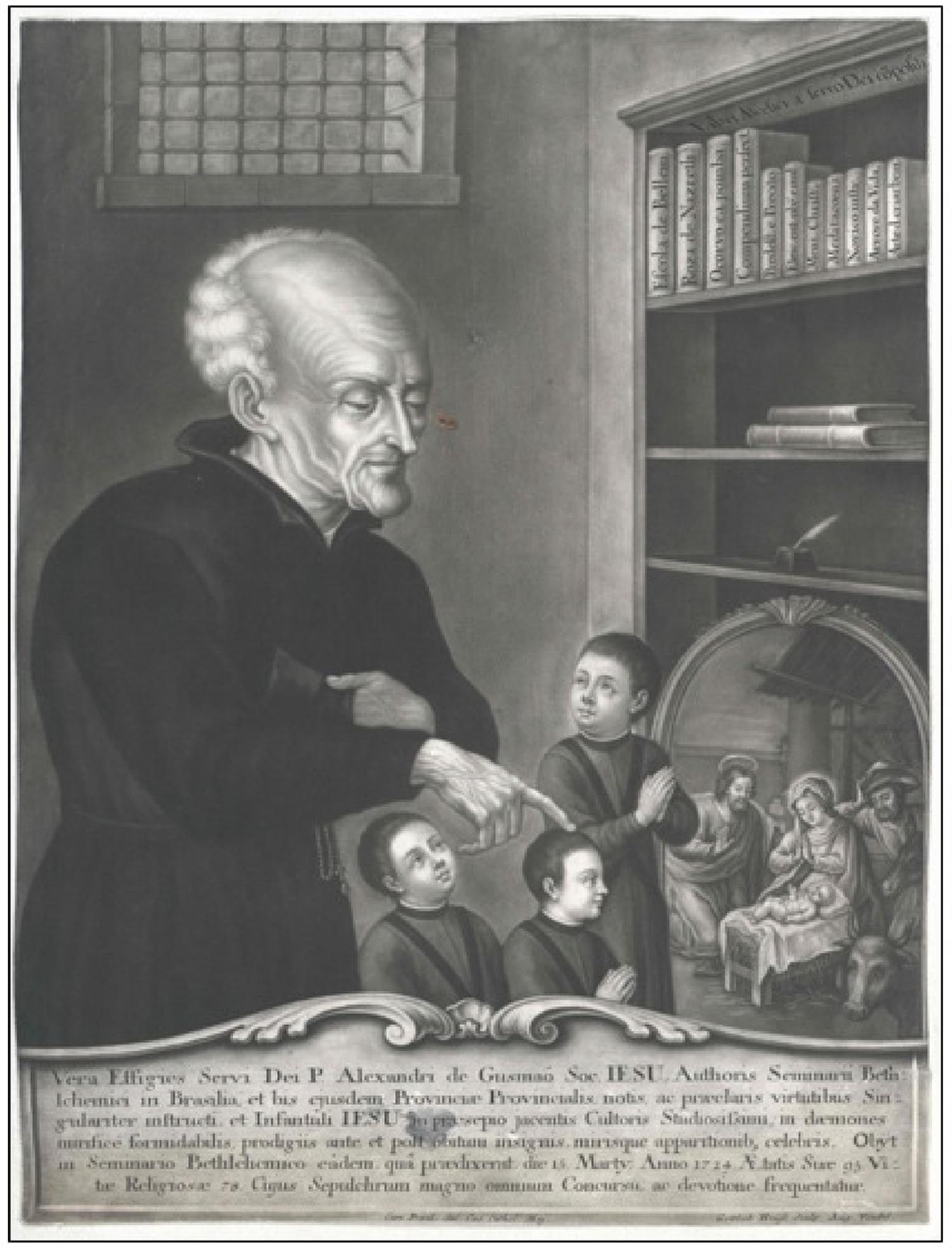

The following image by the Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão calls attention to the fact that the priest was represented teaching a small group of children, all boys, through the symbolic crib of the Baby Jesus. This symbolic representation of teaching demonstrates that the life of the Baby Jesus should be an example for children to follow.

Source: ÖNB Digital6.

Picture 1 – Representation of Priest Gusmão made by the artist Gottlieb Heüfs [undated]

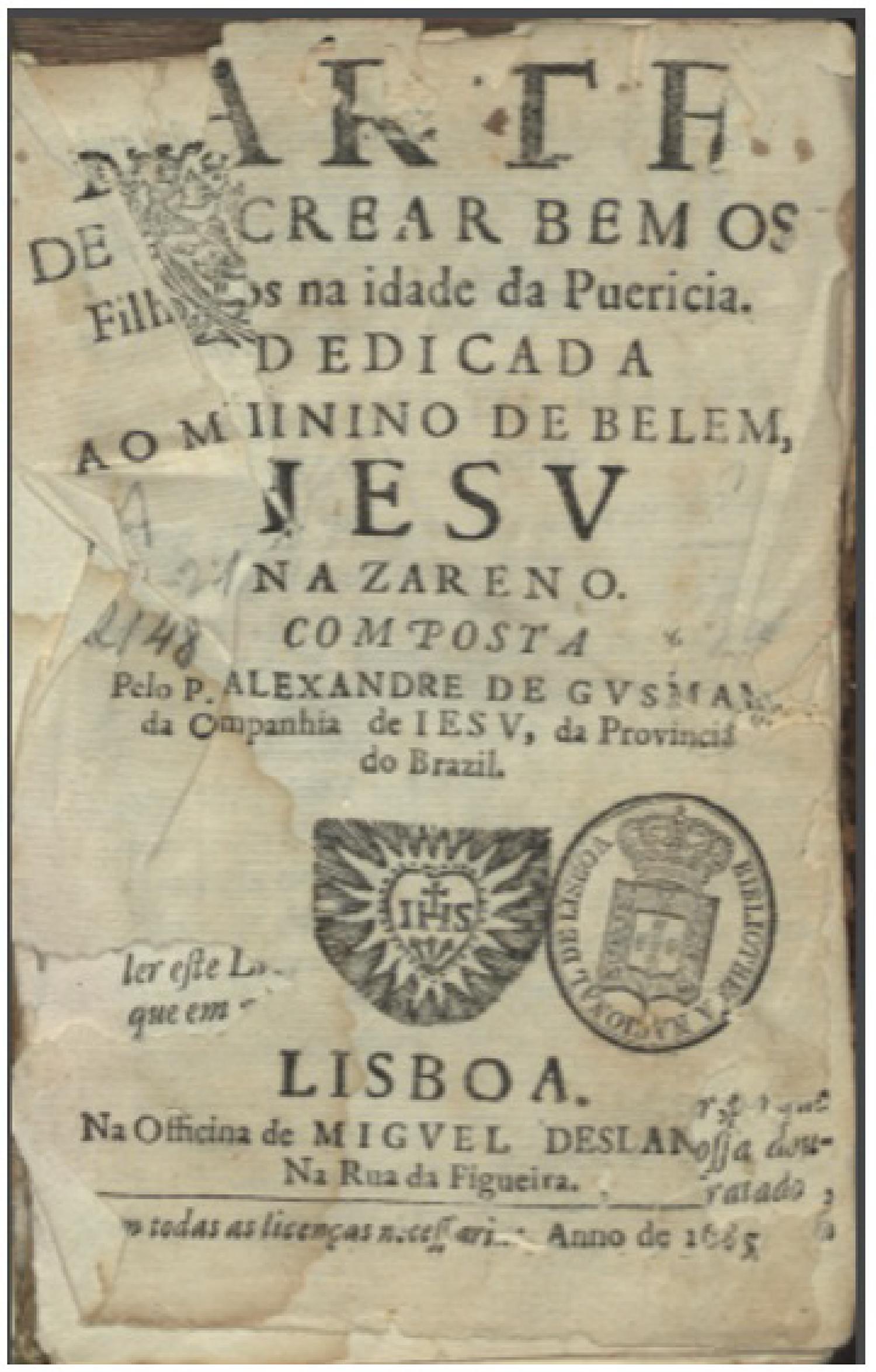

For the analysis of the work Arte de crear bem os filho na Idade da Puericia, we have its digital version available in the repository of the National Library of Portugal (BNP). The print was published in the Officina de Miguel Deslandes, in 1685 in the city of Lisbon and was regularly licensed, as a standard at the time, by the Real Meza of the General Commission on Examination and by the Censorship of Books, as can be seen on the front page.

Source: Biblioteca Nacional Digital.

Picture 2 – Front page of the Work Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia

Considering this scenario of educational practices and models of the Christian subject, we believe that the publication of Alexandre de Gusmão’s work has peculiar aspects for the editorial and social context of the time, which deserve to be highlighted. First, because it is a Catholic treaty written in the territory of the main overseas colony of Portugal, far from the seat of the Kingdom, it can evidence, in addition to the existence of a commercial route for books and booksellers7, also the interest in reading works that demonstrated the model of education that was implemented in the Court and that envisaged its formation in the Colony; secondly, for presenting a Christian-Catholic discourse that met the official desires of the Church to spread its faith and morals and the lay people’s desire for instruction and spiritual elevation through the reading of religious works; thirdly, because Alexandre de Gusmão believed, unlike most thinkers of his time who defined women as possessing reduced rationality, that girls should learn, in addition to “good arts”, the mastery of reading and writing.

By highlighting the context of production of the educational work proposed by Alexandre de Gusmão, we want to propose the analysis of a set of statements that highlight a kind of ordering of living conditions and educational guidelines of female children. We infer that the propagation of works of a moralist nature in the Luso-Brazilian space between the 17th and 18th centuries enabled the circulation of such enunciative orders, significantly influencing the social behavior of the time. This moralizing operation influenced from the knowledge that should be taught to the prescription of certain practical dictates for the daily lives of young maidens. These expected behaviors were considered legitimate and adequate and were part of the discursive construction that wanted to produce a pure, chaste, innocent girl, devoted to Christ, submissive to the will of her father and future husband or to the regulations of some religious order.

For a better systematization of the analysis undertaken in this article, we divide it as follows: first, we present some notes referring to the historiography of the female condition in the colonial context, calling attention to the reduced directions that girls had for learning of reading and writing, when compared to those instructions that were recommended for boys. In this sense, we highlight our main source of analysis as a powerful object of investigation that presents a specific pedagogical program for the education of children; secondly, we identified in the prerogatives of custody and retreat two disciplinary devices recommended by the Jesuit Gusmão, capable of acting in the conformation of behaviors and conducts, as well as expanding the mechanisms of control over the female population.

Notes on the historiography of the female condition in the colonial context and the pedagogical program of Alexandre de Gusmão

We believe that both studies on the history of childhood and on the history of women have highlighted the importance of understanding the religious discourses and practices of care, assistance and salvation that Catholics, in the West, directed to children and women as an interesting object of the historiography. In an expanded perspective, the idea of education will be perceived here both for its “school nature” and for its “non-school educational practices, whether or not involving institutions such as the State and the Church, brotherhoods and lay orders and professional groups” (FONSECA, 2009a, p. 10). Although the education of girls, in the 17th and 18th centuries, did not participate in this current of valuing childhood, some religious dedicated some concern with the ways in which they should be educated. In this educational universe, it is important to confront the different discourses about the cultural meanings attributed to the different ways of instructing girls – linked to values, beliefs and customs –, as well as to understand how they were historically described. As, for example, the three stories, narrated by Natalie Davis (1997) in On the Margins, of women who, in the 17th century, constituted themselves with ease within a misogynist universe, whose imaginary imposed restricted possibilities of action on them.

In the Brazilian historiographical field, there were not a few studies that focused on the female condition in colonial society. The pioneering studies pointed out expectations regarding women and the importance of motherhood8, the practices of seclusion and submission9, and other themes also aroused the interest of historical reflection, such as family relationships, sexuality, criminality, death or sin. However, in the context of the History of Education, there are few studies dedicated to the 17th and 18th centuries10. Furthermore, the investigations that demarcate the condition of female education in the Luso-Brazilian world are restricted. An interesting study, in the field of History of Education, on the normative discourse dictated by eighteenth-century society on female representation was carried out by Arilda Ines Miranda Ribeiro in the work Vestígios da educação feminina no século XVIII em Portugal (2002).11

At the end of the 17th century, female education did not participate in the movement to value education and social transformations12. In this way, it remained with few changes, “attached to the principles established in previous centuries: a very reduced instruction, compared to that recommended for boys, and directed towards the roles that young women should play in adulthood” (ALGRANTI, 1993, p. 240). The majority of girls, in this 17th century Luso-Brazilian context, did not share the literate culture, reserved for the children of the nobles and the most privileged, therefore, the urban aristocracies and nobles. However, the religion in the 17th century not only exerted a dominance over the devotion of the population but also promoted a series of discourses that guided ways of life, in the family and private life,13 through a regime of “living well”, which consisted of a series of instructions, advice and rules to educate the body, mind and soul. However, we can see the presence, in the colonial 1600s, of a pedagogical program to educate children developed by the Society of Jesus.14 It is specifically about the work that we will analyze by the Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão, which here will be perceived as a powerful source on which to base the study of the paradigms of child pedagogy in the Luso-Brazilian world, which efficiency allows to mark beyond the evident religious and cultural spaces, the existence of a long-term model of Catholic education. Gusmão’s work reproduces many of the ideas recorded by humanist pedagogical programs, such as the counter-reformer knowledge and moral precepts propagated among the Society of Jesus.

We identified, through a comparison with other religious works that circulated at the time, that the writing of Alexandre de Gusmão, in Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia, is very similar to the discourses mobilized in the treaty Philosophia moral de príncipes, para su buena criança y govierno: y para personas de todo estado initially published in Burgos (Spain), in the year of 1596, by the also Jesuit Juan de Torres of the Province of Castela.15 Also equivalent to the work of Alexandre de Gusmão, the statements described by Torres that constitute the model of a noble child, the chapters that prescribe the ways and virtues that were desired to be raised in children during childhood. Similarities can also be seen in the humanist pedagogical ideals propagated by François de Salignac de La Mothe Fénelon (1651-1715). Possibly the French Archbishop Fénelon was the author who most influenced female education in the 18th century in Europe. Although his most famous work is Les aventures de Télémaque (1699), it was Traité de l’éducation des filles16 (1687) that Fénelon expanded a little more the guidelines on instructions for girls. Although these educational practices were taught very sparingly, the author highlighted the importance of reading good books17, of the necessary knowledge of literature, history, Latin, music and painting18.

It is worth mentioning that in another study we discussed how written culture was established in the modern period as a condition of possibility for the constitution of children.19 In that investigation, we detected a series of prints, from the 16th century, that indicated ways of educating children from birth. Occasion in which we also draw attention to the potential for discursive propagation of the work De Pueris (1529) of Erasmus of Rotterdam. In the European modern period, there were not a few thinkers who indistinctly propagated the ideas of Erasmus. The advices from the theologian Erasmus were extraordinarily publicized, since in that period and in subsequent centuries, his works had a large number of editions and constant translations. But, we believe it is important to highlight that the woman occupied a reduced space in her pedagogy, as the female role of wife and mother gave marks for female education.

In fact, we believe that the education of girls is a contradictory proposition among the scholars of the 16th and 17th centuries, which enunciative uniformity will only be established in the following century. It was through a set of conditions of possibilities that the presence of the debate around female education in the Luso-Brazilian world took place with greater constancy. One of the possible conditions was, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the numerous mobility of religious who came to Portuguese America bringing in their luggage books of devotional literature obtained in Portugal and in the main European centers. Such literature, according to Ana Rodrigues Oliveira (2007, p. 136), indicated that most pedagogues, since the Late Middle Ages, already advised the age of seven for the intensification of teaching, which could be through the attendance of a school or privately through a preceptor. However, the author believes that the education of girls, especially those closest to the nobility, was conceived by pedagogues as endowed with weak rationality:

[…] Considering such presuppositions [child condition of weakness], very much indebted to Aristotle, pedagogues defended for girls an even more rigid and rigorous discipline than those reserved for women, because the weak rationality of their feminine nature was allied to the still incomplete rationality of the infantile condition. (OLIVEIRA, 2007, p. 137).

Contrary to the discourses that denied the development of good education to girls and women, still in the 16th century, the humanist Juan Luís Vives (1493-1540) in the work Instrucción de la mujer cristiana20 condemned those who did not believe in female education for thinking that the educated woman would be a possible sinner. A similar observation would have been made by M. Claude Fleury (1640-1723) in the treaty Traité du choix et de la méthode des études (1685), according to which women’s education deserved more attention, in addition to that developed pitiful. In Fleury’s opinion, female education should include the study of religion, sacred history, elementary aspects of arithmetic, writing practices and rudimentary knowledge of pharmacy and jurisprudence. The author still observed that other disciplines could be useful to them.21

In the constant publications that guided the female instructions, the prerogatives of guardianship and retreats were intensified. It was regulated that these prerogatives would be given from weaning, but, above all, after the age of twelve until a second condition of the girl, who could either get married or join some religious order. In this sense, it was advised to stop the walks, play outdoors and even have private conversations with other girls. These interdictions had clear motivations, either to preserve the girls’ natural chastity or to control the modesty and shyness characteristic of age.

Guardianship and retreat: enunciations of how girls should be raised

There was an episode reported by Santo Ambrósio22, “who for being such an illustrious Author”, deserved the attention of the Lisbon priest Alexandre de Gusmão. It was the imposition that some lords intended to give when they wanted to “marry a maiden” against her will. What they did not know is that this maiden had already signed a commitment, “that by the vow of a virgin she had taken Jesus Christ as her Spouse”. The attitude taken by the girl was very much associated with the pressure imposed by her relatives to get her to marry, so that “she fled as a victim of chastity to the sacred Altars, for fleeing the instances of her relatives, with which they pestered her, in order for her to marry”. Satisfied with the conditions that the “Author of nature” had destined for her, the virgin replied: “That is what you want from me, gentlemen. That I get married?”. It seemed not to be understood by the lords that the young maiden would have already made the election of a better husband, so that she would not be of any use to her “exaggerate riches, nobility, & beauty”. That “another richer, nobler, and more beautiful I have already found” said the young woman. Another one of “greater commitment” amended the conversation: “if your father were alive, you would not marry”. To which the girl replied that it was “perhaps I died because of this, because it was not an impediment to my holy “poldrinha” 23did not wish to marry, how could he “keep perpetually the most precious pearl of virginity, and live for that in perpetual cloister in the Monastery, what better happiness can I expect from them?” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p, p. 382-384).

The allegory narrated by Gusmão largely represents the female conditions in the 17th century Luso-Brazilian space. Gilberto Freyre (1994) described it as being common, in colonial sociability, for girls to marry at the age of twelve, evidencing the relativization of what it is to be a child for the period, and more specifically, the possibilities of life for the female gender. Two possibilities were accentuated in the imagination of that time, either the girl would be directed to be a good mother and wife, or she would affirm the vows of being a “Religious person consecrated to God, our Lord, and Spouse of Jesus Christ” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 385).

Alexandre de Gusmão emphasized in his treatise that the model for raising the “girls at home” should be similar to the way in which the “girls of the eyes” are cared for. The analogy presented by the Jesuit is based on a proverb of Solomon that “calls them girls, because in the Greek word it sounds like a girl of the eyes, rather than a girl of the house”. (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 377). According to Gusmão the first warning that should be offered in the good upbringing of the girls:

[…] is guarding, and recollection, because just as nature has guarded the girls of the eyes with so many teas, doors, & prisons of chapels, lashes, humors, veils, & membranes, so must those at home be guarded with all vigilance and care (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 377).

From a Foucaldian analysis we identified that the process of discursive prescriptions, which organized the ways of being a girl in the Luso-Brazilian space in the 1600s, based on the internal arrangement of the Church (Society of Jesus), and mobilized in the narrative of writers, incited a detailed process of individual fabrication of female childhood through surveillance and imprisonment. This process of producing subjects becomes efficient to the extent that a series of space regulations are adopted, a restriction of practices and a permanent look at the subject’s conduct. According to Michel Foucault (1997, p. 131):

Each individual in its place: in each place, an individual. Avoid distributions by groups, decompose collective deployments; to analyze the confused, massive or fleeting pluralities. The disciplinary space tends to be divided into as many parts as there are bodies or elements to be shared. It is necessary to annul the effects of indecisive divisions, the uncontrolled disappearance of individuals, their diffuse circulation, their unusable and dangerous coagulation; anti-desertion, anti-wandering, anti-agglomeration tactics. It is important to establish presences and absences, to know where and how to find individuals, to establish useful communications, to interrupt others, to be able at every moment to monitor the behavior of each one, to appreciate it, to sanction it, to measure its qualities or merits. Procedures, therefore, to know, master and use. The discipline organizes an analytical space.

Therefore, we understand the practice of discipline as a mechanism of power, which intention is to regulate the behavior of the subject (child) to desirable social standards. This process of regulation is strategically conceived based on a systematic control of space (for example, groupings of camps, modern school, prison, hospital architectures, etc.), control of time (the creation of routines, establishment of schedules) and promoting moderate and socially accepted behaviors (gestures, posture, games, etc.). However, this disciplining process is reinforced by a complex surveillance system.

For Gusmão, the task of monitoring the girls should be shared by all family members and servants. As a discursive strategy, the Jesuit resorted to São João Chrysostomo, who would have stated that “every family in the house, father, mother, nurse, eunuchs, and servants must take care of the custody of the girls, because all the custody of the house is not enough to only one” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 378). The constancy of watch and retreat, as a form of conformation, correction, the use of good customs, the strengthening of the soul, created certain moderation and became, possibly, the image of a girl of good hopes, in the same way that, symbolically, would set the father free from a temporal death – a constant threat that Gusmão brings of sudden death, that is, the incitement to fear of the possible unforeseen death.

In a way, we can infer that the daughters of the most privileged ones shared the same reflections contained in textbooks and pedagogical treatises, especially with regard to the values and principles that children should have. In general, Christian children should respect a routine very much based on Catholic precepts, taking as examples the hagiographic models, which were widespread since the Middle Ages, which presented good education through narratives about the childhood of the saints.

It is known that since the twelfth century in the medieval West the hagiographies developed the theme of the childhood of the saints in order to promote “models of living and spirituality to be instilled early on young Christians and their respective educators” (OLIVEIRA, 2007, p. 166). These hagiographies prematurely persist in the childhood attachment both to the doctrines and maxims of the Catholic faith and to learning the meaning and practice of renouncing profane pleasures and ideals.

This sanctified childhood model would be the educational basis proposed by Gusmão for raising girls. Not only with regard to the praiseworthy distinctions that the author makes to the saints who as children would become sacred through access to literate education, but for the conduct of a virtuous and pure life with charitable, solemn, pious, innocent, demure, immaculate and castes practices. Regarding the influence of literacy on the girls, Gusmão highlighted the dedication of many of them to the study of letters, which “in erudition exceeded any learned man of his time”:

It is enough for your doctrine to know that St Catherine, since childhood, put herself to the study of Rhetorica, & Philosophia, in which she came out eminent. Saint Eustochio, daughter of Saint Paula, studied Letters, Hebrew, Greek, & Latin, that she was called a miracle of her time. (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 385-386).

It is evident that, in this context, the study of letters aimed at girls had no interest in improving intellectual conditions, but in further sedimenting the “vision of a woman who must be educated in moral and religious precepts, because she is responsible for the destiny of the family” (ALMEIDA, 2003, p. 256). In this way, the Catholic reformism made it possible to expand female education, by considering it important in the social organization of the modern family.

Gusmão would still have resorted to the Ancients24 to advise that the guard and surveillance over the girls should be constant, even the father excusing himself from sleep to watch his daughter. According to the Jesuit, the practice of surveillance also aims to provide spiritual care for the child:

[…] I say that in three things, principally, the parents should watch over the children, insofar as their children are infants: first, Baptize them; second, that they should be baptized in time, and with the solemnity, and good choice of godparents, who are used to go to the Church. Third, when it is possible for mothers to raise their children at their breasts, and when for just causes they cannot, have a great choice in choosing of wet nurses. (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 171-172).

Among the advices offered by Priest Gusmão to vigilant parents were the practices of not allowing girls and maidens to “go out into the street after weaning, playing with the boys, nor allowing them after growing up needless visits” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 378). Gusmão also infers about the danger that such visits can cause to guarded daughters. In this case, even “the older ones” should hide from male visitors. In the words of the Jesuit, “where it is no less urban, otherwise be the Christian police and hide the girls in their rechambers,25 when any visits from men happen to enter their parents’ house” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 379).

The watchful eye of the father was not enough, it was necessary to move away from everything, nothing could corrupt the pure and chaste thought, the “humors from within, which fall from the interior of the brain” must remain angelic. Therefore, if “enclosed in their rechamber they are safe from any dust, which could harm them” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 380). The statements that make up the discourse on child sexuality in the analyzed work point to the prescription of a regulation of children’s behavior. It is worth remembering that the discourses on sexuality, in different historical periods, appear as an attempt to normalize sexual practices according to the standards desired at the time. According to the thinker Michel Foucault (1985), this control of social life could only be achieved through the domain of the body and sexuality. It is in this sense that the philosopher perceived sexuality as a discursive construction, an invention inseparable from discourse and the power relations which it is instituted.

Certainly, the regulation of sex has become a matter of concern for the State and Religion. The constant apprehensions in the works under analysis, as well as in other religious sermons, denote that since the 17th century, sexuality was guided by a markedly moral religious discourse that aimed to regulate and control, or even cure any sexual manifestation in childhood. For Foucault, it was only in the 18th century that sex became a central discursive object, and in the subsequent century:

[…] sexuality was detailed in each existence, in its smallest details; it was dug out in the behaviors; chased in dreams, suspected behind the smallest follies, followed until the early years of childhood; became the key to individuality: at the same time, what makes it possible to analyze it and what makes it possible to constitute it. (FOUCAULT, 1985, p. 137).

Still according to Michel Foucault, the decorum of attitudes, the concealment of body parts, “the decency of words cleanses the speech”, chastity and sex restricted to marriage soften the interdiction of talking about sex (FOUCAULT, 1985, p. p. 10). It should be noted that “if sex is repressed, that is, doomed to its prohibition, nonexistence and mutism, the mere fact of talking about it and its repression has an air of transgression” (FOUCAULT, 1985, p. 12). ). Likewise, it would be possible to expect its effects for a religious person, or even for a child; thus, talking about sex, or even about the practice of chastity, becomes limiting, considering that “the chaste, even talking about chastity, are ashamed” (BLUTEAU, 1712, p. 188). The effect of this repression in the religious field led to rigorous moral discourses about ways of being and remaining chaste. Puritanism, the incitement to chastity, the imperative of the innocent child, the blaming of the most affectionate childhood practices or the most robust games, the classification of abnormalities, the legal punishment of sexual deviants, the architectural projections and the surveillance networks that controlled the biased subjects, as well as other modern technologies and apparatuses that shaped social behavior, placed the “general economy of sex discourses in the core of modern societies from the 17th century onwards” (FOUCAULT, 1985, p. 17). However, the sexual behavior of the child population was not the exclusive object of analysis of the ecclesiastical power.26 In the temporal dynamics from the 17th to the 18th century, the discursive network that observed and determined its effects and limits widened, so that its interest became biological, economic and political, as a public thing and a matter of State. (CORAZZA, 2004, p. 271).

Philippe Ariès (2012, p. 136) highlighted that “an essential notion was imposed: that of childhood innocence”, so that the passage from shamelessness to innocence was promoted through the chastity condition of those who were just being born. Two aspects, for the author, contributed to the discourses of religious and moral reformers, from the second half of the 16th century, to evidence childhood as a stage of innocence: first, innocence, which should be preserved and, second, ignorance, which needed to be suppressed. Thus, the “sense of innocence resulted, therefore, in a double moral attitude towards childhood: to preserve it from the dirt of life, and especially from the tolerated – when not approved – sexuality among adults, and to strengthen it, developing the character and the reason” (ARIÈS, 2012, p. 91).

Final considerations

In the reflection presented in this text, it is intended to offer a small contribution to the History of Education from the analysis of the treaty by the Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão, Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia. Notably, the greatest peculiarity may be in the source used, since it allows the analysis of discourses about education and the condition of childhood women in colonial Portuguese America. Another singularity resides in the Foucauldian theoretical horizon, which made it possible to perceive and problematize surveillance and punishment as regulatory mechanisms of a shared female social behavior, propagated and promoted by a patriarchal and deeply devout society.

However, it is worth stating that the debate around intellectual capacities and the process of female education, particularly in France, has been intense since the end of the 17th century. At the same time that the Catholic reform project allowed a relative increase in the number of girls’ schools inside convents and retreats, the proliferation of literate women seemed to become a social concern/threat. In this complex relationship between religious institutions for women and knowledge, Zechlinski (2013, p. 175) revealed that, if, on the one hand, education opened “the doors to female erudition, enabling the nuns to exercise daily writing and reading”, on the other hand, “when this erudition began to evade the walls of the monasteries, sending educated girls into the world, it was considered harmful to the precepts of the Church”.

In the elaboration of this text, we apprehend that the expansion of intellectual production concerning female education was made possible through modern European thought, between the end of the 17th century and throughout the following one, which through different models of enunciation – scientific, pedagogical, religious, philosophical etc. – spread specific ways of being a woman, of being a mother, of being a wife, but, more specifically, of how to be educated. In this sense, the Christian guidelines of guardianship and retreat for the girls gained visibility in our analytical enterprise, enunciated by the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Gusmão when he promoted a series of edifying advices for the upbringing of children. The control of child sexuality was also important in this process, as nothing could distort the girls’ pure and chaste thinking.

In this discursive context, we identified the dissemination that female education could establish values and regulate behaviors. Such functions, at that time, did not seek to integrate a discourse of civilizational transformation, but to impose submissive behaviors and expand the mechanisms of control over the female population, which was markedly associated with the aegis of Christian foundations.

In this perspective of female instruction and education, spiritual formation stood out. The religious dimension increasingly established itself as an integral part of the process of formation of the female subject. Based on rules and control mechanisms, such as custody and retreat, the education of women in the Luso-Brazilian space was intended to be a model, reinforcing detachment, altruism, the spirit of sacrifice, filial love side by side with humility, obedience and submission, considered as desirable virtues for a good mother and future wife.

On the other hand, in the second half of the 18th century, a literature which main objective was also to be edifying, but which indicated the mastery of reading and writing by women, circulated in the second half of the 18th century. There were many sermons on virtues and ethics classes that prepared the girls that were closest to the nobility to be perceived as good, exemplary, chaste, Christian, moderately intellectual, “true ladies, knowing their place and their role” (MACHADO, 2008, p. 19).

Finally, we identified in the sermons of the Jesuit Alexandre de Gusmão a series of statements that incited the parents in the disposition of surveillance and the imprisonment of their daughters. These statements made up a set of recommendations on the importance of watching over female children and on how to discipline them through custody and retreat. However, Gusmão differed from most thinkers of his time in indicating access to literate education as a way of raising girls. For the Jesuit, the literacy of girls seems to be a possible constant in “the most political nations, & well-ordered Republics” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 386-387). In this sense, Gusmão shares that:

It is stated that it is not convenient, but very commendable, to teach the good arts to daughters from a young age; at least when reading, writing must learn all, those who are created for Religious must learn some principles of the Latin language. (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 386).

In this way, we understand that the Christian orientation to the education of girls was intended to act in the production of subjectivities, in the governance of souls and in the management of female childhood life, creating disciplined, obedient and literate maidens. From the recommendation of various disciplinary techniques, we identified that parents should keep, retreat and write to know their daughters in depth and incline them to the “holy love of virginal purity” (GUSMÃO, 1685, p. 381).

REFERENCES

ALGRANTI, Leila Mezan. Educação de meninas na América Portuguesa: das instituições de reclusão à vida em sociedade (séculos XVIII e início do XIX). Revista de História Regional, Ponta Grossa, v. 19, n. 2, p. 282-297, 2014. [ Links ]

ALGRANTI, Leila Mezan. Honradas e devotas: mulheres da colônia: condição feminina nos conventos e recolhimentos do Sudeste do Brasil, 1750-1822. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1993. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Suely Creusa Cordeiro de. O sexo devoto: normatização e resistência feminina no Império Português – XVI-XVIII. 2003. Tese (Doutorado em História) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, 2003. [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Álvaro de Araujo. O inventário crítico das ausências: a produção historiográfica e as perspectivas para a história da educação na América Portuguesa. História e Cultura, Franca, v. 4, n. 2, p. 100-117, 2015. [ Links ]

ARIÈS, Philippe. História social da criança e da família. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: LTC, 2012. [ Links ]

ARNAUT DE TOLEDO, Cézar de Alencar; ARAÚJO, Vanessa Freitag de. Educação e religião na obra Arte de criar bem os filhos na idade da puerícia, de Alexandre de Gusmão, de 1685. In: SEMINÁRIO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS HISTÓRIA, SOCIEDADE E EDUCAÇÃO NO BRASIL, 8., 2009, Campinas. Anais […]. v. 1. Campinas: Unicamp, 2009. p. 1-21. [ Links ]

ARNAUT DE TOLEDO, Cézar de Alencar; BARBOZA, Marcos Ayres. Fundamentos da educação cristã no Brasil Colonial no século XVII. In: ARNAUT DE TOLEDO, Cézar de Alencar; RIBAS, Maria Aparecida de Araújo Barreto; SKALINSKI JUNIOR, Oriomar (org.). Origens da educação escolar no Brasil Colonial. Maringá: UEM, 2015. p. 13-40. [ Links ]

AZZI, Riolando; REZENDE, Maria Valéria. A vida religiosa feminina no Brasil colonial. In: AZZI, Riolando (org.). A vida religiosa no Brasil: enfoques históricos. São Paulo: Paulinas, 1983. p. 24-60. [ Links ]

BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara. Da educação das meninas por Fénelon (1852). Revista História da Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 16, n. 36, p. 147-188, 2012. [ Links ]

BELLINI, Lígia. Cultura escrita, oralidade e gênero em conventos portugueses (Séculos XVII e XVIII). Tempo, Niterói, v. 15, n. 29, p. 211-233, 2010. [ Links ]

BLUTEAU, Raphael. Vocabulario portuguez & latino: letras B-C. Coimbra: Collegio das Artes da Companhia de Jesus, 1712. v. 2. Disponível em: <http://www.brasiliana.usp.br/en/dicionario/1/castidade>. Acesso em: 04 set. 2015. [ Links ]

BLUTEAU, Raphael. Vocabulario portuguez & latino: letras O-P. v. 6. Lisboa: Officina de Pascoal da Sylva; Impressor de Sua Magestade, 1720. [ Links ]

CATANI, Denice Bárbara; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de. Um lugar de produção e a produção de um lugar: história e historiografia da educação brasileira nos anos de 1980 e de 1990 – a produção divulgada no GT História da Educação. In: GONDRA, José Gonçalves (org.). Pesquisa em história da educação no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2005. p. 85-112. [ Links ]

CORAZZA, Sandra Mara. História da infância sem fim. 2. ed. Ijuí: Unijuí, 2004. [ Links ]

COURTINE, Jean-Jacques. Decifrar o corpo: pensar com Foucault. Tradução Francisco Morás. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2013. [ Links ]

DAVIS, Natalie Zemon. Nas margens: três mulheres do século XVII. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1997. [ Links ]

DEL PRIORE, Mary. Ao sul do corpo: condição feminina, maternidades e mentalidades no Brasil Colônia. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1993. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Norbert. O processo civilizador: uma história dos costumes. v. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1993. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, António Gomes. Três propostas pedagógicas de finais de Seiscentos: Gusmão, Fénelon e Locke. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, Coimbra, v. 22, p. 267-292, 1988. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Thais Nivia de Lima e. Historiografia da educação na América Portuguesa: balanço e perspectivas. Revista Lusófona de Educação, Lisboa, v. 14, p. 111-124, 2009a. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Thais Nivia de Lima e. Letras, ofícios e bons costumes: civilidade, ordem e sociabilidade na América Portuguesa. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2009b. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. História da sexualidade I: a vontade de saber. 6. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 1985. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Vigiar e punir: nascimento da prisão. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1997. [ Links ]

FREYRE, Gilberto. Casa-grande & senzala: formação da família brasileira sob o regime da economia patriarcal. 29. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 1994. [ Links ]

GUSMÃO, Alexandre de. Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia: dedicado ao minino de Belém JESU Nazareno. Lisboa: Officina de Miguel Deslandes, 1685. [ Links ]

JINZENJI, Mônica Yumi. Cultura impressa e educação da mulher no século XIX. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2010. [ Links ]

LAGE, Ana Cristina Pereira. Conexões Vicentinas: particularidades políticas e religiosas da educação confessional em Mariana e Lisboa oitocentistas. Jundiaí: Paco, 2013. [ Links ]

LEITE, Serafim. História da Companhia de Jesus no Brasil. t. 1-10. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1949. [ Links ]

LEITE, Serafim. A história da Companhia de Jesus no Brasil. t. 4-6. São Paulo: Loyola, 2004. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Diogo Barbosa. Bibliotheca Lusitana histórica, critica, e cronológica. t. 1. Lisboa: Officina de Antonio Isidoro da Fonseca, 1741. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Ana Maria. Diálogos duradouros. In: LEPRINCE DE BEUMONT, Jeanne Marie. Tesouro de meninas ou diálogos entre uma sabia aia e suas discípulas. Rio de Janeiro: Lexikon, 2008. p. 7-24. [ Links ]

NEVES, Lúcia Maria Basto das. João Roberto Bourgeois e Paulo Martin: livreiros franceses no Rio de Janeiro, no início do oitocentos. In: ENCONTRO REGIONAL DE HISTÓRIA, 10., 2002, Rio de Janeiro. Anais […]. Rio de Janeiro: UERJ, 2002. p. 129. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Ana Rodrigues. A criança na sociedade medieval portuguesa. Lisboa: Teorema, 2007. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Claudia Fernanda. Educação feminina e sociabilidades na América Portuguesa: a mulher entre o lar e o mundo do trabalho na Comarca do Rio das Velhas (1750/1800). In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO, 5., 2008, Aracajú. Anais […]. Aracajú: UFS, 2008. p. 1-13. [ Links ]

O’NEILL, Charles; DOMÍNGUEZ, Joaquim María. Diccionnario histórico de La Compañía de Jesús: bibliográfico-temático. Madrid: Universidad Pontifícia Comillas, 2001. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michelle. Outrora, em outro lugar. In: PERROT, Michele (org.). História da vida privada 4: da Revolução Francesa à Primeira Guerra. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1991. p. 14-17. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Arilda Ines Miranda. Vestígios da educação feminina no século XVIII em Portugal. São Paulo: Arte & Ciência, 2002. [ Links ]

RIPE, Fernando Cezar; AMARAL, Giana Lange do. O dispositivo da cultura escrita na constituição do sujeito infantil moderno: evidências em impressos portugueses (finais do século XVII e século XVIII). Revista Maracanan, Rio de Janeiro, n. 16, p. 106-128, 2017. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Adair José dos Santos. A educação feminina nos séculos XVIII e XIX: intenções dos bispos para o Recolhimento Nossa Senhora de Macaúbas. 2008. Dissertação (Mestrado em História da Educação) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2008. [ Links ]

ROCHA PITTA, Sebastião da. História da América Portuguesa: coleção de estudos brasileiros. Salvador: Águia e Souza, 1950. [ Links ]

ROGERS, Rebecca; THÉBAUD, Françoise. La fabrique des filles: l’éducation des filles de Jules Ferry à la pilule. Paris: Textuel, 2010. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Zulmira. Emblemática, memória e esquecimento: a geografia da salvação e da condenação nos caminhos do «prodesse ac delectare» na história do predestinado peregrino e seu irmão Precito (1682) de Alexandre de Gusmão SJ [1629-1724]. In: COLÓQUIO INTERNACIONAL A COMPANHIA DE JESUS NA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA NOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII, 2004, Porto. Anais […]. Porto: Universidade do Porto, 2004. p. 581-600. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Zulmira; QUEIRÓS, Helena. Letras e gestos: programas de educação feminina em Portugal nos séculos XVIII-XIX. Via Spiritus, Porto, n. 19, p. 59-122, 2012. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Lais Viena de. Educados nas letras e guardados nos bons costumes: Padre Alexandre de Gusmão S. J. Salvador: UFBA, 2015. [ Links ]

TAMBARA, Elomar; GHIGGI, Gomercindo. Apresentação. In: GUSMÃO, Alexandre de. Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia: dedicada ao Menino de Belém Iesu Nazareno. Pelotas: Seiva, 2000. [ Links ]

TORRES, Juan de. Philosophia moral de príncipes, para su buena criança y gobierno, y para personas de todos os estados. Lisboa: Pedro Crasbeck, 1602. [ Links ]

VENÂNCIO, Renato Pinto; RAMOS, Jânia Martins. Apresentação. In: GUSMÃO, Alexandre de. Arte de crear bem os filhos na idade da Puericia. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2004. p. 9-32. [ Links ]

VILLALTA, Luiz Carlos. Bibliotecas, leitura e educação. Revista do Arquivo Público Mineiro, Belo Horizonte, v. 48, p. 20-21, 2012. [ Links ]

ZECHLINSKI, Beatriz Polidori. A educação feminina e seus conflitos: a atuação de religiosas francesas em contraste com os programas pedagógicos do século XVII. Revista Diálogos Mediterrânicos, Curitiba, n. 5, p. 153-175, 2013. [ Links ]

2 - View Rocha (2008), Villalta (2012), Oliveira (2008) and Lage (2013). However, it is possible to notice the existence of a concentration of that productivity on conventual spaces and retreats located in Minas Gerais. In addition, studies of Azzi and Rezende (1983), Almeida (2003) and Bellini (2010).

3 - However, it is worth highlighting the study carried out by Algranti (2014) who, through normative documents – such as education treaties, study plans and manuals on good manners and civility – reflected on the representations of society in relation to women and what they were expected to learn to better perform their functions and work in society.

4- On this last assertion, Gusmão highlighted the fifth chapter, entitled “How useful is the good upbringing of boys for the entire Republic”. In the sense perceived by Gusmão, the idea of Republic is not related to the form of government, but to the notion of a community of interest, in which subjects share common purposes.

5 - Alexandre de Gusmão wrote, among catechetical texts, sermons and treatises for education and moral behavior, a total of thirteen works: Escola de Belém, Jesus born in the crib (Évora, 1678); Arte de crear bem os filhos da Puericia (Lisbon, 1685); História do predestinado peregrino e seu irmão Preciso (Lisbon, 1682); Sermão na catedral da Bahia de Todos os Santos (Lisbon, 1686); Meditação para todos os dias da semana (Lisbon, 1689); Meditationes digestas per anum e menino cristão (both published in 1695); Rose of Nasareth, nas montanhas de Hebron (Lisbon, 1709); Eleição entre o bem & o mal eterno (1717); And the posthumous publications O corvo e a pomba da arca de Noé e Árvore da vida (both published in Lisbon, 1734), Compendium perfeccionista religiosea (Venice, 1783) and Preces recitandae statis temporibus ab alumnis Seminari Bethlemici (no date, possibly 1783).

6- Available in: https://digital.onb.ac.at/rep/osd/?10CE6E73. Acessed:2 march 2022.

7 - Regarding the trade in books and booksellers, it is suggested to consult Neves (2002).

8 - This is the case of Del Priore (1993).

9 - Here it is worth mentioning the work of Algranti (1993).

10 - Here, it is worth highlighting the critical panorama outlined by the historian Álvaro de Araujo Antunes (2015), about the production on the History of Education in Portuguese America, and the surveys carried out by Denice Catani and Luciano Faria Filho (2005) and Thais Nivia de Lima e Fonseca (2009b), who note the low percentage of works covering the period between the 16th and 18th century in the annals of the main events in the areas of History and History of Education.

11 -Although focusing on another temporality, in this case in the 1800s, it is important to highlight the study by Mônica Yumi Jinzenji, who identified the circulation of printed material that disseminated actions and knowledge about women in the context of relations between Metropolis and Colony in the work Cultura impressa e educação da mulher no Século XIX (2010).

12 - Norbert Elias, in the work The civilizing process (1993), pointed out the incessant prescriptions of “external corporal decorum” – posture, clothing, facial expressions – that were widely published through treatises in Europe since the end of the Middle Ages, seeking to meet a need for civilité of the time.

13 - According to Perrot (1991), throughout the 18th century in Europe there was a strong distinction between what belonged to the public sphere and what belonged to the private sphere in people’s lives. With the counter-revolution, this distinction became the definition of social roles, such as the differentiation that put men (as public subjects) and women (subject to the domestic model, therefore, private) in opposition.

14 - As a study reference on the education model implemented by the Society of Jesus in the process of overseas missions, we suggest Serafim Leite (1949).

15- Torres’ work is impressive not only for its voluminous treatise, approximately 995 pages plus appendices, but for the discursive tone of its recommendations and prescriptions for the good upbringing and government of princes.

16 - In 2012, Maria Helena Câmara Bastos published a translation of this work into Portuguese in the História da Educação magazine. She located in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France an 1852 edition supposedly translated by José Fonseca (also translator of The Aventuras de Telêmaco). In that document, Bastos adds that the education of women, directed by Fénelon, should be exclusively moral and private, not collective, but with a public, social purpose. Nevertheless, the main purpose of female education was in the ability to educate children and govern the home. For this purpose, Fénelon denounced the bad influence of ignorant and futile mothers, the bad Society of servants, who would not be good models, as they made the child indolent, insignificant, fearful, liar. She recommended, then, an attractive, virtuous and balanced education, based on good models, preferably those propagated and shared by Christians. Unlike Alexandre de Gusmão, who repeatedly enunciated punishment as a corrective method, Fénelon condemned punishment and recommended light penalties, applied in circumstances that did not provoke shame or remorse in the child. Education should also provide distractions and some entertainment, but he did not recommend that boys and girls stay together, have frequent outings, lots of conversations, especially with people characterized by bad nature. (BASTOS, 2012, p. 148).

17 - Fénelon highlights the vigilance that parents should have on the consumption of prohibited readings such as novels or entertainment reading.

18- As a reading suggestion we indicate: Ferreira (1988); Rogers and Thébaud (2010).

19 - In Ripe and Amaral (2017), we characterize modernity as a condition of possibility for the discursive proliferation about childhood. On that occasion, we present a set of works that were published and/or translated in Portugal between the end of the 17th century and the 18th century, which dealt with child care. Such printed productions were taken as subjectivity technologies and, therefore, effectively operated in the process of constitution of the modern child subject.

21- According to the historian Leila Algranti (1993, p, p. 242), for Fleury it would be “an audacity” to give the girls “other subjects” that “would be useless to them”.

22- Saint Ambrose configures, among the saints, the one with the greatest recurrence in Gusmão’s treatise. In all, there were seventeen narratives alluded to Saint Ambrose.

23 - According to Bluteau’s Dictionary (1712, v. 6, p. 571) poldrinha refers to young mare. However, in the stated context it seems to designate a girl who is pretty.

24- According to Ripe and Amaral (2017), when evoking the texts of ancient writers, 18th century authors exemplify models of virtuous lives, highlighting as the main moral virtues: prudence, justice and temperance. In the same way, the theological virtuous attitudes of faith, hope and charity were prestigious, which, in addition to fighting possible vices - the child subject, in that period, was considered as easily corruptible -, edified spiritual and moral education. According to Ripe and Amaral (2017), when evoking the texts of ancient writers, 18th century authors exemplify models of virtuous lives, highlighting as the main moral virtues: prudence, justice and temperance. In the same way, the theological virtuous attitudes of faith, hope and charity were prestigious, which, in addition to fighting possible vices - the child subject, in that period, was considered as easily corruptible -, edified spiritual and moral education.

25- The meaning of recamera (rechamber), in the context used by Gusmao, refers to some kind of inner and reserved chamber. It can also mean dressing room or wardrobe. Also quoted in the Bible, in Song of Songs 1.4, as the place where we can have an intimate and personal contact with God. Source: Priberam Dictionary of the Portuguese Language. Available at https://www.priberam.pt/dlpo/rec%C3%A2mara Accessed on: 2 Aug. 2017. The meaning of recamera (rechamber), in the context used by Gusmao, refers to some kind of inner and reserved chamber. It can also mean dressing room or wardrobe. Also quoted in the Bible, in Song of Songs 1.4, as the place where we can have an intimate and personal contact with God. Source: Priberam Dictionary of the Portuguese Language. Available at https://www.priberam.pt/dlpo/rec%C3%A2mara Accessed on: 2 Aug. 2017.

26 - It is worth noting the exemplification that Philippe Ariès put forward when describing that the sexual behavior of children was a recurrent idea that dates back to the 15th century, through the treatise De confissione mollicei, written by Gerson (1606) to help confessors to promote, in small penitents, the feeling of guilt. For Ariès, the propositions that Gerson presented in his treatise were very close to modern doctrine, as they did not consider the child as conscious of guilt. In this case, an example is that onanism would be an inevitable stage of sexuality. Although approaching an idea of innocence, Gerson actually promoted a “modification of the habits of education and the establishment of a new behavior towards children”. For Ariès, its regulation is so interesting, due to the moral ideal that Gerson imposed, that it would become a reference for the Jesuits and “of the brothers of Christian doctrine and all the moralists and rigorous educators of the 17th century” (ARIÈS, 2012, p. 81-82).

Received: May 16, 2020; Revised: August 25, 2020; Accepted: September 29, 2020

texto em

texto em