Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 03-Jun-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248239129por

ARTICLES

The child body in the crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school *

1- Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, PR, Brasil. Contact: gbcamargo@uepg.br

2- Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil. Contact: marynelmagaranhani@gmail.com

With an interpretive and ethnographic basis, we carried out a research to understand what the experience of crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school is like, from the children’s point of view. And with this scenario, we bring in this text, reflections on the child body. For this, anchored in studies of the Sociology of Childhood, and motivated by the research problem-question (What is the experience of crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school like, from the children’s point of view?), the production of data considered the expressions of six children in two school contexts: a school of early childhood education and another of the early grades of elementary school, in the city of Ponta Grossa, Paraná, Brazil, from August 2018 to July 2019. Through the insertion of the researchers in the group of children, with participant observations, interviews and monitored visits, we sought an adequate interlocution to their speeches, understanding that they go beyond the exclusive use of verbal or written language, covering the movements of their body and their gestures. The data, emerging from the children’s speech, generated two themes for analysis: differences and strategies. These unfolded in the following axes of analysis: a) routines and spaces; b) school practices; and c) rules. The analyzes allowed us to reflect on the child’s body, the power of its movements and gestures as a valid way for the child to be in the world and belong to it, producing culture, interpreting and relating, shaping and influencing the social constructs in which they are inserted.

Key words: Child body; Crossing; Research with children; Early grades of elementary school

Com base interpretativa e cunho etnográfico, realizou-se uma pesquisa para compreender como é a experiência de travessia da educação infantil para os anos iniciais do ensino fundamental, do ponto de vista das crianças. E com esse cenário trouxemos, para este texto, reflexões sobre o corpo criança. Para isso, ancorada em estudos da Sociologia da Infância e motivada pela pergunta problema de pesquisa (como é a experiência de travessia da educação infantil para os anos iniciais do ensino fundamental, do ponto de vista das crianças?), a produção de dados considerou as expressões de seis crianças em dois contextos escolares: uma escola de educação infantil e outra de anos iniciais do ensino fundamental, no município de Ponta Grossa, no Paraná, no período de agosto de 2018 a julho de 2019. Por meio da inserção das pesquisadoras no grupo de crianças, com observações participantes, entrevistas e visitas monitoradas, buscou-se uma interlocução adequada às suas falas, compreendendo que elas ultrapassam o uso exclusivo da linguagem verbal ou escrita, abrangendo os movimentos do seu corpo e sua gestualidade. Os dados, emergidos das falas das crianças, geraram dois temas de análise: diferenças e estratégias. Esses se desdobraram nos seguintes eixos de análise: a) as rotinas e os espaços; b) as práticas escolares; e c) as regras. As análises permitiram refletir sobre o corpo criança, a potência de seus movimentos e gestualidades como uma maneira válida de a criança ser e estar no mundo, produzindo cultura, interpretando e se relacionando, moldando e influenciando os constructos sociais em que estão inseridas.

Palavras-Chave: Corpo criança; Travessia; Pesquisa com crianças; Anos iniciais do ensino fundamental

Introduction

[…] in the middle of the crossing, even the ground is lacking, the domains end. Then the body flies and forgets what is solid, no longer in expectation of stable discoveries, but as if installing itself forever in its foreign life: arms and legs enter a weak and fluid portance, the skin adapts to the turbulent environment, the vertigo of the head stops because from now on it can only count on its own support; in the pain of drowning, it gains confidence in the slow stroke. […]. ( SERRES, 1993 , p. 12).

When leaving and going to another place, the body experiences the turbulence of the river, the smell of the wind, the freshness of the water, the heat of the effort that swimming in the chaos of the in-between place provides, and with that, it reinterprets its movements, re-signifies its senses and changes. Serres (1993) alludes to the crossing of an impetuous river in every transition that happens to us, culminating in the body’s effort to experience the sensations that the action of crossing impels us to. To him “the body that crosses certainly learns a second world, the one towards which another language is spoken. But it begins above all in a third one, through which it transits” ( SERRES, 1993 , p. 12). The experience of crossing is individual, non-transferable, particular and is shown in the body, that is, it “sounds […] the body, that is, sensitivity, touch and skin, voice and ear, sight, taste and smell, pleasure and suffering, caress and wound, mortality” ( LARROSA, 2011 , p. 24).

Crossing, in this sense, is more comprehensive than transiting, as it implies considering body sensitivity in the process of moving from one place to another, from one situation to another, from one level to another. It is not simply going from one situation to another, but interpreting the senses that the body finds for the meaning of the passage. In this scenario, we present in this text the research we carried out to understand what the experience of crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school is like, from the children’s point of view3 .

This research, motivated by the research problem-question (What is the experience of crossing from early childhood education to the initial grades of elementary school like, from the children’s point of view?), took place in two school contexts: a Municipal Center for Early Childhood Education (known by the acronym CMEI – Initial Margin of the study – IM) and a school for the early grades of elementary school (School – Final Margin – FM), in the municipality of Ponta Grossa – PR.

With an interpretative and ethnographic investigation with children, we were included in a group of finalists in early childhood education (IM), from August to December 2018, at the CMEI. We accompanied these children on the crossing to the first grade of elementary school (FM) on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays from February to July 2019, at the School adjacent to the CMEI . Thus, the research period comprised the months of August to September 2018 and February to July 2019. During this period, we sought to get closer to the children, establishing a relationship of trust and sharing with them in everyday school life. An agreement between the management teams of the CMEI and the School was made at the beginning of the research, to make it possible for the children to be together in the first grade class of the FM. Considering that the School had three first-grade classes in 2019, this agreement favored the monitoring of children in classroom routines.

When we entered the IM, we joined a group of twenty-six children. With all of them we experienced the last stage of early childhood education. However, six children showed greater interest in producing data for the research. They gave us more attention than the others. They expressed their perceptions and reflections about the school and, therefore, brought us closer in different situations. They became the data producing subjects of this investigation.

In seeking a close relationship with the children, based on the condition that our posture was not one of control, dominion, or teaching, but of researchers curious to know their points of view, we used some data production instruments that brought us closer to them and their particular ways of interpreting the context4 in which they were inserted.

Thus, through participant observations of children in their routines, individual and collective interviews and monitored visits5 , we sought an adequate interlocution with their speeches, understanding that they go beyond verbal language, covering the movements of their body and their gestures. By understanding, as Le Breton (2007 , p. 7), “first of all, existence is corporeal”, we assume that the evidence of human existence is legitimized by the movements of the body that are transformed and transform a given space and time through actions and gestures, translated into the languages and expressions that guide our social relations. In this way, the child understands, interprets, creates culture, relates to his/her social universe from his/her body in motion.

For insertion and approximation with children, we admit that our posture as researchers gained the nuances of the least-adult concept ( MANDELL, 2003 ), which is defined as

[…] a membership role which suspends adult notions of cognitive, social, and intellectual superiority and minimizes physical differences by advocating that adult researchers closely follow children’s ways and interact with children within their perspective. Achieving a close involvement with small children is accomplished by sharing social objects. Through joint manipulation of objects, children and least-adult researchers take each other into account and create social meaning. By acting with children in their perspective, adults gain an understanding of children’s actions. ( MANDELL, 2003 , p. 58).

Thus, in the semantics of this crossing, the body and its differences, in the condition of least-adult, was not the cause of a relationship of control or power over children, when exercising the role of researchers. On the contrary, we approached them through movements and gestures that reflected our interest in being part of the group, as adults that we are, but putting ourselves in the place of sharing with children in their activities and action strategies in the school context. The body became the axis that produced the meanings and senses of “actions that wove the plot of everyday life, from the simplest and least concrete to those that occur in the public scene” ( BUSS-SIMÃO et al ., 2010 , p. 153).

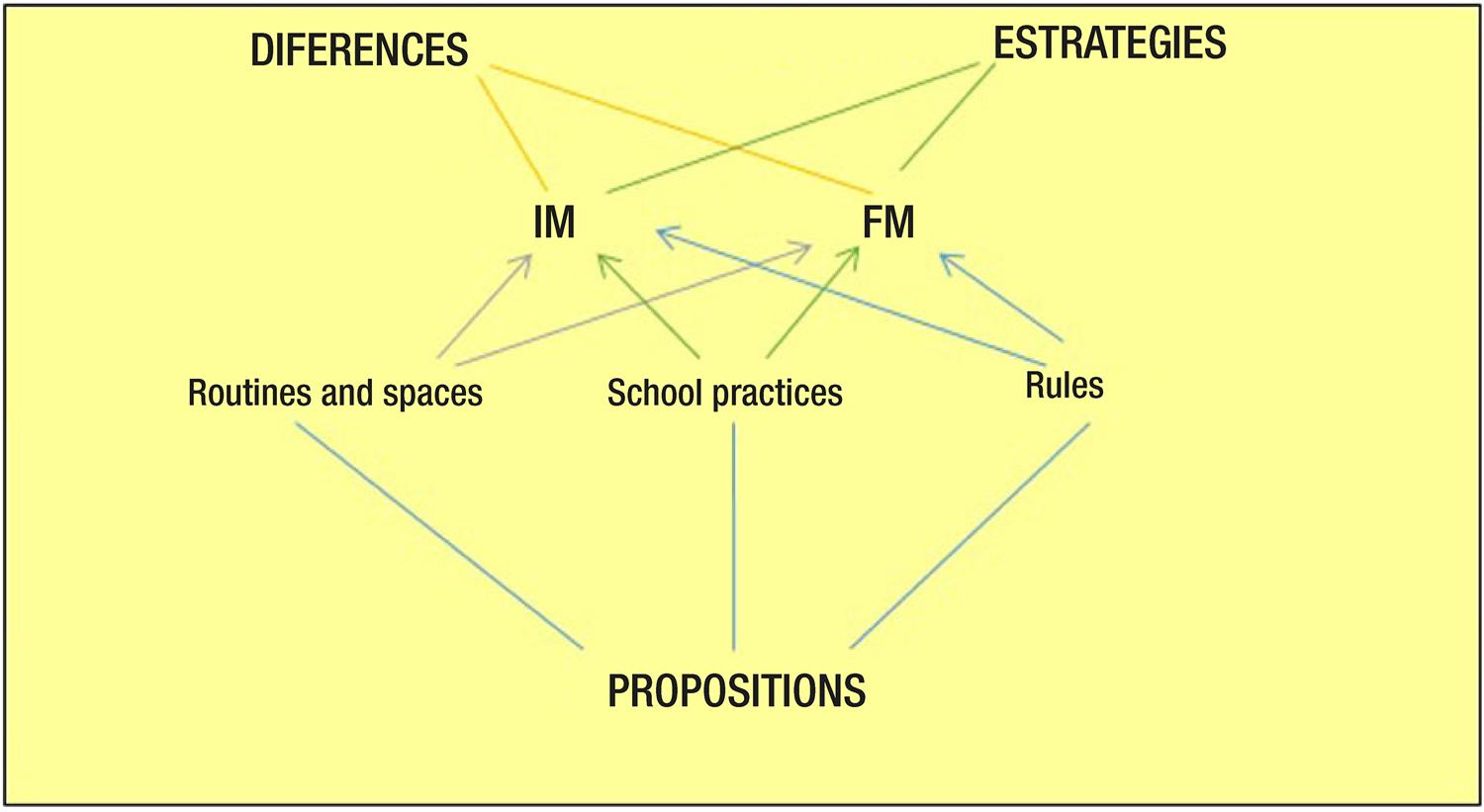

After the production of the data, we encoded the themes that emerged from the children’s speeches, through triangulation ( MINAYO, 2010 ) and we listed the structuring axes of the analysis. Thus, differences and strategies constituted the axes of analysis and in them we intertwined the themes picked from the speeches of the children that were organized into: a) routines and spaces; b) school practices; and c) rules. Observing the structuring axes that permeate these themes of analysis, we could see the revealed meanings and senses attributed by children to their crossing.

In the children’s speeches, it was still possible to verify some suggestions for the (re)organization of the school of the FM. The propositions made by them pointed out aspects that can compose the culture of the child’s school; rites and customs different from those found there. This organization of the data generated an analysis design, as shown in Figure 1 .

With this organization and from the triangulation as a method of data analysis, it was possible to see the meanings and senses attributed by the children to their crossing.

That is, with the body in movement (free or repressed), with their gestures, the children revealed their interpretations of the world, of the customs and routines of schools, of the relationships that gave rise to these contexts, and created strategies to face the constraints, reflected on cultures, acting consciously in this social universe.

In summary, the research took us and (re)affirmed the appropriation and use of the child body concept6 , in this and in other studies that we are carrying out, by visualizing and understanding the power and role of the child in the gesture of his/her body in movement.

Thus, supported by the perspective that Le Breton (2007 , p. 7) proposes on the bodily condition of human experience, in which “the body is the semantic vector by which the evidence of the relationship with the world is constructed”, and allied to the understanding that “the child uses his/her body as a totality” ( MERLEAU-PONTY, 2006 , p. 183), we propose the understanding that the child has his/her own body characteristics and specificities in relation to the world, a condition that constitutes him/her as a child. And the body, as a set of physical, affective, historical and social dimensions ( GARANHANI, 2008 ), in the child condition, expresses encodings not so marked and/or under construction, which constitutes the child body. Therefore, the child is body and the body is child in its different expressions and communications. It is the child’s body that feels, thinks, interprets, acts, relates, lives. And because it is a different body from the adult body or the elderly body, because it has particular characteristics and is less affected by social coding, it is called a child body.

With this understanding, the child body in the context of the crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school will be the focus of our discussion in this text.

The child body in the perspective of childhood sociology

According to James, Jenks and Prout (1999 , p. 208), “there is a lack of clarity about the status of the body in much of the work on new sociological approaches to childhood”. From the point of view of the Social Sciences, driven by the question of what the body is, some explanations were constructed, such as foundationalist and anti-foundationalist ones.

Foundationalists explain that “the body is a real, material entity which is not reducible to the many different frameworks of meaning found in different cultures […]” ( JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 , p. 210). Being defended as a biological entity, whose functioning is independent of social relations, the body, for foundationalists, should be studied by sociologists, based on how it is “interpreted and experienced by different protagonists in different social and cultural contexts” (p. 211). According to the authors, this approach excludes investigations about the body in social and cultural relations.

Anti-foundationalists, by contrast, “argue in an entirely idealist fashion: that there is no material body – only our constructions or understandings, which are shaped by social circumstances” ( JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 , p. 211). From this perspective, sociologists must analyze the social representations of the body.

To these authors, both explanations “mirror the twin reductionisms […] making different and contradictory ontological and epistemological assumptions at every level” ( JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 , p. 210). This led us to seek other perspectives to interpret the child body.

In an attempt to overcome dualistic conceptions of the body, studies such as the one of Merleau-Ponty (1968)7 emerge in the post-industrial revolution context, which value the body as a locus of a subjective experience of the human being and include “both an appreciation of the importance of embodiment and the active role of children, assimilating and building their social world through this embodiment” ( JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 , p. 227).

In this sense, Merleau-Ponty (2011 , p. 257) states that “the use that a man will make of his body is transcendent in relation to this body as a simply biological being”. That is, our perception, speech, thought, and feeling only occur because we are an embodied and contextualized body.

In line with this, Le Breton (2007) explains that there are models of society that are communitarian and differ from individualistic models, with regard to the understanding of the body. In his words:

In societies that remain relatively traditional and communal, the ‘body’ is the connecting element of collective energy and, through it, each man is included in the bosom of the group. On the contrary, in individualistic societies, the body is the element that interrupts, the element that marks the limits of the person, that is, where the individual’s presence begins and ends. ( LE BRETON, 2007 , p. 30).

With this, community societies demarcate the body with inseparable elements, in which there is no division between thought and the physical being. That is, in these contexts, the body is thought, feeling, action, relationship. Body is subject, or “man and body are inseparable and, in collective representations, the components of the flesh are mixed with the cosmos, nature, and the others” ( LE BRETON, 2007 , p. 30).

Corroborating this, Larrosa (2002) explains that experience is what happens to us, or what happens in the body, in the total being. From this perspective, the body is not dissociated from the mind, nor subjugated to it. But it is through the body that the process of self-regulation of the physical, emotional, intellectual and social relationships takes place.

In this scenario, we ask: What, in the individual, is able to think? What elements of the being are able to feel? Although the discussion permeates the understanding of the abstract (thought and feeling), the answer is body. It is the body that thinks and feels. This body, as a total, inseparable being, a subject that lives in a unique way its relations with nature, with the subjects around it, with its micro and macro-social context. In this way, we were interested in this concept of child body, to defend that the child body, in the crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school, is the place of its experience, as much as it is the place of its interpretations and social actions. Thus, the child body is the way children experience, interpret their realities, understand social constructs, build cultures, regulate and relate to each other in their social life contexts.

Children, because they have not accessed some social regulations (or because they have not been so altered by social codes), expose their bodies in a powerful and protagonist way in the environment in which they live, as the “body uses labels [that] govern the interactions” ( LE BRETON, 2007 , p. 74) can only be consolidated in early adulthood. According to James, Jenks and Prout (1999 , p. 224-225):

What distinguishes the child from the adult is understood as the successful practice and performance of an internalized, even unconscious control over the body and its functions. This means, therefore, that little children who have not yet learned the specific (and historically variable) techniques of body control are culturally uncivilized.

We can interpret that the child’s incivility (term used by JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 ) makes them able to incorporate and act in their universes in a powerful, creative, intrepid and protagonist way, as they were little changed by the codes of social conduct.

Children are powerful subjects in interpretation and action in their schools. The experiences of children, in the transition from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school, observed in the investigation by the gestures of their body in movement, made us rethink the routines, practices, rules and school customs instituted by adults. Their speeches, their movements and gestures highlighted that school cultures need to legitimize the child body, as it represents the subject in all his/her instances, whether physical, cognitive, emotional, social or cultural, among others.

The child body in the crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school

In the particular contexts that the two schools presented in this research, we concentrated efforts to understand the children’s experiences in the routines and spaces of their schools, with the school practices experienced and with the rules contained in the two environments. Their different speeches (including non-orality) revealed their conscious abilities to observe the differences between their schools, to develop strategies for their experiences and to indicate propositions to compose school routines.

In the analysis of the theme “school routines and spaces”, we highlighted the children’s speeches and the indication they made of the differences in some aspects of their schools. Elements that made up the rituals of their school institutions, and demarcated the way in which the relationships within them are thought and conducted.

The less vibrant colors in the early grades of elementary school interpreted as disenchantment with the school space; the inadequate size of the furniture that makes up the classrooms and the decoration of this environment, translated as a way of controlling the movement of the child’s body; the reduced time and space for playing submitted to the primacy of curricular contents of literacy; care with food and rest, brought to reflect the time spent in school in the early grades of elementary school. These were the elements that the children listed and made sense of, identifying them as different from those experienced in the school of early childhood education.

These differences experienced by the children, and which were expressed in the movement of the body, led to the rupture of the identity they had in the school of early childhood education and led to the elaboration of a new one, adjusted to the elements of the current school. Corroborating this, James, Jenks and Prout (1999 , p. 220) state that “the body in childhood is an essential resource for the acquisition and rupture of identity due to its unstable materiality”. This unstable body changed when it crossed from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school.

Upon arriving at the school in the first grade of elementary school, the children read their cultural dictates, adapted to them and left their marks there. Thus, the children’s new identity, built by the influence of their bodily experiences in the context of the school in the early grades of elementary school, in contact with the rituals and customs of this school, in contrast to those of the school of early childhood education, leads us to reflect on the way in which we, educational managers, teachers, public agencies responsible for the schooling of children, researchers and intellectuals in education, have thought of schools for children.

If the body is “shaped by society through social habits such as […] disciplinary regimes, and by symbolic processes that provide interpretations for the body” ( JAMES; JENKS; PROUT, 1999 , p. 224), we must question which body child, as a biopsychosocial existence, we are forming in our school institutions.

To the extent that school adults are concerned with having control and power over the bodies that are there, children create ways to face these situations of control, as it was possible to observe in the strategies they developed to diversify the school routine from early grades of elementary school, making the classroom trash can a place for meetings, conversation and laughter; and to expand the spaces for playing, running and moving around, by simulating the need to go to the bathroom.

In the reflection on the theme “school practices”, the children identified that, in the early grades of elementary school, there is a decrease in time and space for playing in relation to the practices of the school of early childhood education, but they also revealed that, due to being grown up and attending the big children’s school, the act of playing was re-signified. Thus, what we thought would be a frustration for them in crossing from one segment to the other was manifested as a good thing. The children, surprisingly, indicated that the new ways of playing, viable in the first grade of elementary school, were consistent with their expectations for this stage of their lives. This is not because adults organized games suitable for grown children, but because in their creative potential, children created conditions to explore their movements and gestures in the face of obligatory tasks and the imposition of norms. Just like when they avoided the teacher at recess to spend a little more time picking berries or when, in the classroom, they pretended to have completed the activity so that their group would not have to suffer punishment.

The boys revealed with their speech how much their body movements are expandable and guide their commitment to the learning process at school. Unlike the girls in this study, who revealed that in their strategies they preferred more introverted games and sought to train the tracing of the letters at home in order to succeed in the activities proposed at school.

We realized with this that girls tend to act with more restrained movements and gestures in relation to boys. Although they also subvert the rules in the school context, they are more discreet than boys. We believe that this body conformation is not only related to the issue of gender and social class, but especially to the issue of generation as a social category ( QVORTRUP, 2010 ).

To Qvortrup (2010) , children are subjects of a generational category: Childhood. And they are subject to the same social parameters (economic, technological, cultural, political, among others) as the other categories. Nonetheless,

[…] the generational categories do not suffer or deal with the impact of these parameters in the same way. They are in different positions in the social order. Means, resources, influence and power are distributed differently across categories, whose abilities to face external challenges consequently vary. ( QVORTRUP, 2010 , p. 638).

Corroborating with Qvortrup (2010) , we understand that, although discussions about the child’s agency have advanced, childhood has still been subordinated to other generational categories. It is a subordination linked not only to the factor of caring for children, but to the pejorative idea of their incompleteness. Height, weight, body dimensions, and their own logic are characteristics that lead to this misleading thought that the child is an incomplete subject (or a becoming-subject), which will only be complete when he/she reaches adulthood. A thought that needs to be changed, because all of us, children, young people, adults and old people are incomplete subjects, from the point of view that we always have something to achieve, to evolve and to develop. In this way, the school, as the locus of school experience, needs to be the place where the idea is propagated that despite generational differences (gender and social class) and different levels of development, we are all on the same path of human evolution and we must share this path with otherness.

The children demonstrated that they were able to think about their schooling processes by identifying the differences in school practices in the two schools and by creating participation strategies based on their movements and gestures, involving play in these contexts, as they understood that learning takes place in the body, that is, it is based on bodily experience.

In the analysis of school rules, the children were able to identify the differences between the two environments. They realized that the rules and norms contained an emphasis on the regulation and control of their movements and gestures.

It is known that, both in early childhood education and in the early grades of elementary school, rules and norms are established with the prerogative of organizing collective living. However, in the school of early childhood education, the children did not emphasize the retaliation imposed on them for not complying with them. Unlike the elementary school, in which the punishments for disobedient and transgressors were always related to the deprivation of body movements that playing could provide during recess, which caused embarrassment to the children, as it was possible to observe in their speeches.

Thus, we understand that the rules and norms in the early grades of elementary school were instituted to preserve the institution (its furniture, its rituals, the curriculum) and not the children. This was observed in their speeches when they reported the order they constantly received to sit down and be quiet. Both commands denote the adults’ power of control over children and the framing of their bodies in school cultures, which are anchored in the understanding of the split between body and thought. That is, the rule presupposes that staying seated and silent, containing the movements of their bodies, their speeches and gestures, is necessary so that their mind can learn. This dualism in which the human body is an entity separate from the mind – as the foundationalists cited by James, Jenks and Prout (1999) claimed – has been refuted by theories that understand the body as the subject’s experience in broader scopes ( LE BRETON, 2007 ; MERLEAU-PONTY, 2006 ). However, there are many institutions, in different social instances, that still employ it in their organizations, as is the case of this school, for example.

The children broke the rules with a variety of genuine strategies, such as when they played hide-and-seek with the teacher, crawling under chairs, or when they faked displays of affection to avoid being scolded for their disobedience. In all the strategies created by them, the demonstration that they are emancipated and competent subjects for the school experience is present.

The propositions made by the children revealed their abilities to read and interpret the universe in which they are inserted. When, eagerly and creatively, they proposed that the elements of play and make-believe be emphasized in the routines and spaces, practices and rules of the first grade of elementary school, indicating that they wanted to be validated in their different forms of expression and in the particular logic of childhood, revealed that they are competent in carrying out interpretive reproduction8 in the context in which they live. In the same way, when they suggested that activities that relate learning and play should be expanded in the first grade of elementary school, they taught us to observe the schooling process from other angles, removing adults from the center, and putting them side by side with children and their cultures.

The suggestion of one of the research subjects to make it possible to do whatever the children wanted in the school context reveals an understanding that yearned to have more power in this context. The laughter after the proposition, however, revealed that he knew the purposes and routines of the school and, therefore, considered it unfeasible to be allowed to do everything the children wanted. The issue remains for adults who are involved in the schooling process to think about: Is it possible for a school to combine what is necessary, from the adults’ point of view, with what is pleasant, from the children’s point of view? Perhaps, the answer to this question is related to the understanding of the body as a subject’s experience in the context of Childhood Pedagogy9 .

What was evident in this study is that the child’s experience in crossing from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school occurs in and through the child’s body. This experience is loaded with unique meanings and senses, as children are competent and skilled subjects in reading and intervening in the school context.

Some final considerations about the study

By corroborating with the scholars of the Sociology of Childhood and Pedagogy of Childhood, we believe that our schools lack a “pedagogy that focuses on the processes of constitution of children as concrete and real human beings, belonging to different social and cultural contexts, which are also constitutive of their childhood” ( ROCHA; LESSA; BUSS-SIMÃO, 2016 , p. 35).

For this, the dilution of disciplinary boundaries, namely studies of Biology, Psychology, Anthropology, Sociology, among others, about children is one of the strategies to promote new school practices.

When considering the child as a competent and creative subject, who participates, interprets the reality in which is inserted and influences him/her, we understand that he/she must be placed together with adults in the process of organizing the school, at a level of sharing decision-making and actions. That is, the child body and the adult body can share the management of the schooling process. Childhood Pedagogy, as an area that “emerges from a scientific accumulation in the area of education that starts to criticize the reproduction of reductionist and conservative educational models of education/teaching, production/transmission of knowledge, collective life/classroom and children/students” ( BARBOSA, 2010 , p. 2), can be a useful ground to legitimize children’s cultures and the child body, validating their participation in sharing decision-making in the school context.

The experiences of children in the transition from early childhood education to the early grades of elementary school encouraged the reflection that we, adults, who are childhood scholars, still have a lot to learn. The ways in which schools are organized, their school practices, their routines and spaces, rules and norms, need to be restructured, taking into account what children say, their movements and gestures in their educational contexts. This is an exclusive movement of each school institution, which starts from the “deconstruction of many theoretical bases with which children were systematically thematized in the social sciences” ( SARMENTO, 2005 , p. 374), to consider their different ways of living, interacting and decision-making in this environment.

If we assume that the body in motion is one of the valid ways for the child to be in the world and belong to it, if we change the understanding of how they produce culture, interpret the world, relate to each other, shape and influence social constructs, we will be closer to internally transforming the concept of childhood and/or childhoods and, consequently, change our perspective on the pedagogical process, inverting the centrality of the schooling process.

To change a conceptual formulation, we must go through a process of inner transformation, managed, among others, by evolutionary, socio-historical events, which range from knowledge to conviction, confirming or refuting what was already postulated in us intrinsically. Thus, the reflection that this study proposes can favor the process of transformation and resignification of childhoods in school contexts. However, we know that this transformation process is an individual and non-transferable experience ( LARROSA, 2011 , 2014 ), so our intention is to encourage more people to dedicate themselves to childhood studies from the children’s point of view.

In addition, we would like this study to contribute to overcoming the body and thought dualism that (still) exists in the collective imagination of the school and in the common sense of those who participate in it, and encourage the understanding that the experience is made and imprinted on the body, as a whole and singular subject.

Valuing the child’s body in its power, and empowering children as subjects who share decisions and actions in the school context are actions that contribute to making this a place where knowledge, learning, social relationships and school plots are mixed ( SERRES, 1993 ). May these plots, resignified by the children in the experience of the crossing, affect the adults of the school and culminate in a relationship of sharing actions and decisions in the school environment, in which the child body has ensured, in all its power and protagonism, its right to act consciously .

Finally, that the school plots, in their meeting points, favor us to understand that we are all apprentices and about to learn what the crossings can teach us.

REFERENCES

BARBOSA, Maria Carmen Silveira. Pedagogia da infância. In: OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade de; DUARTE, Adriana Maria Cancella; VIEIRA, Livia Maria Fraga. Dicionário verbetes: trabalho, profissão e condição docente. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2010. p. 2. Disponível em: https://gestrado.net.br/verbetes/pedagogia-da-infancia/. Acesso em: 3 out. 2019. [ Links ]

BUSS-SIMÃO, Márcia et al. Corpo e infância: natureza e cultura em confronto. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 26, n. 3, p. 151-168, 2010. [ Links ]

CORSARO, William A. Sociologia da infância. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. Mil platôs: capitalismo e esquizofrenia. Tradução Ana Lúcia de Oliveira. 3. ed. São Paulo: Ed. 34, 1996. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Cinthia Votto. A identidade da pré-escola: entre a transição para o ensino fundamental e a obrigatoriedade de frequência. 2014. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2014. Disponível em: https://sucupira.capes.gov.br/sucupira/public/consultas/coleta/trabalhoConclusao/viewTrabalhoConclusao.jsf?popup=true&id_trabalho=1345481. Acesso em: 10 out. 2017. [ Links ]

GARANHANI, Marynelma Camargo. A educação física na educação infantil: uma proposta em construção. In: ANDRADE FILHO, Nelson Figueiredo de; SCHNEIDER, Omar. Educação física para a educação infantil. São Cristóvão: UFS, 2008. p. 123-142. [ Links ]

GRAUE, Mary Elizabeth; WALSH, Daniel J. Investigação etnográfica com crianças: teorias, métodos e ética. Tradução Ana Maria Chaves. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbernkian, 2003. [ Links ]

JAMES, Allison; JENKS, Chris; PROUT, Alan. O corpo e a infância. In: KOHAN, Walter Omar; KENNEDY, David (org.). Filosofia e infância: possibilidades de um encontro. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1999. p. 207-238. (Filosofia na escola, v. 3). [ Links ]

LARROSA, Jorge. Experiência e alteridade em educação. Reflexão e Ação, Santa Cruz do Sul, v. 19, n. 2, p. 4-27, 2011. [ Links ]

LARROSA, Jorge. Notas sobre a experiência e o saber de experiência. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 19, p. 20-28, 2002. [ Links ]

LARROSA, Jorge. Tremores: escritos sobre experiência. Tradução Cristina Antunes e João Wanderley Geraldi. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2014. [ Links ]

LE BRETON, David. A sociologia do corpo. Tradução Sônia M. S. Fuhrmann. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

MANDELL, Nancy. The least-adult role in studying children. In: WAKSLER, Frances Chaput (ed.). Studying the social worlds of children: sociological readings. London: Falmer Press, 2003. p. 38-60. [ Links ]

MARCONDES, Keila Hellen Barbato. Continuidades e descontinuidades na transição da educação infantil para o ensino fundamental no contexto de nove anos. 2012. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, 2012. Disponível em: https://repositorio.unesp.br/bitstream/handle/11449/101554/marcondes_khb_dr_arafcl.pdf?sequence=1. Acesso em: 12 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Rita de Cássia; GARANHANI, Marynelma Camargo. A organização do espaço na educação infantil: o que contam as crianças? Revista Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 11, n. 32, p. 37-56, 2011. [ Links ]

MERLEAU-PONTY, Maurice. Fenomenologia da percepção. Tradução Carlos Alberto Ribeiro de Moura. 4. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2011. [ Links ]

MERLEAU-PONTY, Maurice. Psicologia e pedagogia da criança. Tradução Ivone C. Benedetti. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2006. [ Links ]

MERLEAU-PONTY, Maurice. Résumés de cours: Collège de France 1952-1960. Paris: Gallimard, 1968. [ Links ]

MINAYO, Maria Cecília de Souza. Introdução. In: MINAYO, Maria Cecília de Souza; ASSIS, Simone Gonçalves de; SOUZA, Edinilsa Ramos de (org.). Avaliação por triangulação de métodos: abordagem de programas sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz, 2010. p. 19-51. [ Links ]

NEVES, Vanessa Ferraz Almeida. Tensões contemporâneas no processo de passagem da educação infantil para o ensino fundamental: um estudo de caso. 2010. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2010. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/BUOS-8FNP4D. Acesso em: 10 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, Gabriela Medeiros. A passagem da educação infantil para o 1º ano no contexto do ensino fundamental de nove anos: um estudo sobre alfabetização, letramento e cultura lúdica. 2011. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, 2011. Disponível em: http://guaiaca.ufpel.edu.br/handle/123456789/1614. Acesso em: 11 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

QVORTRUP, Jens. A infância enquanto categoria estrutural. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 36, n. 2, p. 631-644, 2010. [ Links ]

RANIRO, Caroline. O final da educação infantil e o início do ensino fundamental: a escola revelada por crianças e professoras. 2016. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, 2016. Disponível em: https://sucupira.capes.gov.br/sucupira/public/consultas/coleta/trabalhoConclusao/viewTrabalhoConclusao.jsf?popup=true&id_trabalho=3716203. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2017. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Eloisa Acires Candal; LESSA, Juliana Schumaker; BUSS-SIMÃO, Márcia. Pedagogia da infância: interlocuções disciplinares na pesquisa em educação. Da Investigação às Práticas, Lisboa, v. 6, n. 1, p. 31-49, 2016. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.mec.pt/pdf/inp/v6n1/v6n1a03.pdf. Acesso em: 4 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

SARMENTO, Manuel Jacinto. Gerações e alteridade: interrogações a partir da sociologia da infância. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 26, n. 91, p. 361-378, 2005. [ Links ]

SERRES, Michel. Criar. In: SERRES, Michel. Filosofia mestiça. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 1993. p. 7-44. [ Links ]

3- We believe that the meaning of the experience of the child body, in the transition that one school segment to the other provides, is what characterizes the novelty of this study, among so many others already consolidated in this theme, such as: Neves (2010) ; Nogueira (2011) ; Marcondes (2012) ; Fernandes (2014) ; and Raniro (2016) .

4- Graue and Walsh (2003 , p. 25) explain that context is a unit of culture, “a culturally and historically situated space and time, a specific here and now. It is the link between the categories of macro-social and micro-social events”.

5- The monitored visit “consists of a visit with an oral presentation, conducted by the children participating in the research, to the investigated spaces. During this presentation they narrate the spaces and, at the same time, speak freely about them. These statements often evoke memories, desires, feelings that are expressed by children and that, depending on the purpose of the research, may be an important source of data”. ( MARTINS; GARANHANI, 2011 , p. 45).

6- The concept of the child body is being built by researchers from the Educamovimento Research Group – Center for Studies and Research in Childhood and Early Childhood Education of Federal University of Paraná ((Nepie)/UFPR), with the prerogative of revealing and respecting specificities and characteristics that the child’s body presents. We understand that this concept is developed by other authors, namely from Philosophy, such as Deleuze and Guattari (1996) , and they explain the child body as a power of action and transformation of reality, through the body without organs and the becoming-child. Our perspective differs from it due to the emphasis we place on the child body as a competent social subject and creator of cultures.

7- We consider the author’s phenomenological expression important for understanding the body. Despite this, we do not intend to deepen his theoretical presuppositions, but to agree with the aspect that “the body is the hidden form of one’s own being or, conversely, that personal existence is the resumption and manifestation of a being in a situation”. ( MERLEAU-PONTY, 2011 , p. 229).

8- Interpretive reproduction is a concept developed by Corsaro (2011) . This concept proposes that children are not limited to reproduce or imitate their peers and social subjects, but are competent to produce cultures.

9- “The denomination Pedagogy of Childhood or Early Childhood Education was formulated from the recognition of the birth of an area, or subarea of Education, which had been concerned with specific educational instances, different and prior to school. The accumulation of these studies also presented a peculiar mark, taking childhood and the educational processes aimed at it as an object of concern, in a different way from those traditionally consolidated in educational theories, that is, critically contesting the Pedagogies of the child, based on liberal educational theories of the 20th century” ( ROCHA; LESSA; BUSS-SIMÃO, 2016 , p. 34).

Received: June 04, 2020; Received: August 25, 2020; Accepted: November 12, 2020

texto em

texto em