Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 13-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248243440esp

ARTICLES

2 - Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile. Contacto: asanhueza@uct.cl

4- Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, España. Contactos: neus.gonzalez@uab.cat; gustavo.gonzalez@uab.cat

This article proposes a substantive theory intended to explain the Mapuche people’s social invisibility phenomenon in the History and Social Sciences school curriculum, based on what elementary school teachers think, say and do in Chile. The research method was designed using Grounded Theory through its systematic and reflexive modality.This study was developed by means of a triangulation method combining questionnaires, interviews and participant observations, applied to elementary school teachers. The investigation integrated the different elements of Grounded theory into an organizational scheme that included the structure proposed by Strauss and Corbin (2002) and the research process for the purpose of developing our theory. The data codification process was conducted with the help of ATLAS.ti software. The results show an oficial knowledge policy that operates within the curriculum and makes the Mapuche history and memory invisible in the History school curriculum. Furthermore, there are certain mechanisms that intervene in the maintenance of this social invisibility, such as standardized tests, the professional development of elementary school teachers and the educational community.

Key words: History teaching; Mapuche culture; Cultural diversity; Curriculum design

El artículo propone una teoría sustantiva que busca explicar el fenómeno de la invisibilidad social del pueblo mapuche en el currículo escolar de Historia y Ciencias Sociales a partir de lo que piensan, dicen y hacen los profesores y profesoras de educación primaria en Chile. La investigación se llevó a cabo través de la teoría fundamentada en su modalidad sistemática y reflexiva. El estudio se desarrolló a partir de la triangulación de cuestionarios, entrevistas y observaciones participantes aplicadas a docentes del ciclo básico. El proceso de investigación integró los diversos componentes de la teoría fundamentada en un esquema organizativo que incluyó la estructura propuesta por Strauss y Corbin (2002) con el objetivo de formar nuestra teoría. La codificación de los datos fue realizado con el apoyo del software ATLAS.ti. Los resultados revelan una política oficial del conocimiento que opera en el currículo y que transforma en invisible la historia y la memoria mapuche en el currículo de Historia. Además, intervienen ciertos mecanismos que mantienen la invisibilidad social como las pruebas estandarizadas, la formación de docentes y la comunidad educativa.

Palabras-clave: Enseñanza de la historia; Cultura mapuche; Diversidad cultural; Diseño curricular

Introduction

This paper falls into a line of research that analyzes the invisibility of relevant actors such as women, children, indigenous people and sexual minorities in the teaching of history and Social Studiess. Furthermore, this line raises the necessary challenges to include them in teacher’s the daily activities and in that way to contribute to giving visibility to a world in where all of us are actors capable of transforming society (MAROLLA; PINOCHET; SANT, 2018).

Social invisibility of diverse groups has gone from a problem to a research topic and, currently, a hermeneutical category that allows to understand a contradictory phenomenon that implies to be in the world, but not to be seen or heard (THOMPSON, 2005; TOMÁS, 2010; VOIROL, 2005). Bourdin (2010) and Brighenti (2007) indicate that social invisibility is related to other categories such as exploitation, domination, and social contempt. In this order, to be socially invisible is the last experience of submission and implies a sign of the social structure that mutilates existence of groups such as women, children, sexual minorities, and indigenous people. Social invisibility thus shows a texture line that is more profound and of inexhaustible knowledge (MERLEAU-PONTY, 2010; LE BLANC, 2009). Visibility is the obverse of invisibility, nevertheless, both are part of a same process -of social construction- that weights on individuals or over their activities in the social space. In words of Le Blanc (2009): “Ainsi, le visible et l’invisible sont-ils des constructions sociales et non pas seulement les formes transcendantales de l’apparaître et du disparaître attachées à la plasticité des vie” (p. 195). Kràl (2014) and Honneth (1997 & 2011) explain that social invisibility does not have to be related -uniquely- with lack of presence -knowledge-, but with the negation of the existence in the social sense -recognition-. That is, the underestimation of its role as a relevant social actor in the public space. Therefore, social invisibility encloses at its center a collection of political struggles that revolve around identity, gender, race, or class. Voirol (2013) and Brighenti (2007) explain that there exist modalities of social invisibility. According to this, there exist minimum or maximum thresholds that help to understand the possibilities of a just visibility and to not contribute to the distortion of social representations.

In the area of history and Social Studies teaching, the discussion about invisibility has focused on the epistemological fields of History to reflect on a fundamental knowledge of history for citizens. That is, to question the historiographic paradigm that privileges the historic knowledge linked to political and institutional elements (HEIMBERG, 2015; MATOZZI, 2015). Precisely, a group of research has been developed in this area that have focused -preferably- in three fundamental scopes: 1) the training of teachers (ORTEGA; MAROLLA; HERAS, 2020; ANGUERA et al., 2018; MAROLLA; PAGÈS, 2015; SANTISTEBAN, 2015; CERECER; PAGÈS, 2013); 2) social representations of the students towards invisible groups (MAROLLA, 2018, 2019; MASSIP; PAGÈS, 2016; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT; PAGÈS; SANTISTEBAN, 2015); and 3) the revision of the curriculum and school textbooks (SANHUEZA; PAGÈS; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, 2019a, 2020; PAGÈS; VILLALÓN; ZAMORANO, 2017; PINOCHET; URRUTIA, 2016; PAGÈS.; VILLALÓN, 2013; VILLALÓN; PAGÈS, 2013, 2015; PAGÈS; SANT, 2012; SANT; PAGÈS, 2011). Nevertheless, other research has looked into the effects that teaching centered in political and military facts has on invisible groups and, furthermore, which knowledge can invisible groups bring to the teaching of History (SANHUEZA; PAGÈS; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, 2019b; SANHUEZA et al., 2018; TURRA; CATRIQUIR; VALDÉS, 2017).

This form of submission minimizes the participation of the Mapuche educative communities and gives a greater understanding of the western knowledges over those ancestral ones. This is shown with the exclusion from teaching and learning the history of the Mapuche knowledge on geography and the conception of time and temporality (CARTES, 2021; CUBILLOS; 2015). This last idea is in line with the body of research in the field of education in societies that have suffered colonialism, such as Mexico, Brazil or Canada (CEREZER, 2019; SANHUEZA; PAGÈS; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, 2019b; PLÁ, 2016; SEIXAS, 2012).

Grounded Theory in the didactics of history and Social Studiess

In Social Studiess didactics research, it is fundamental to explain the diverse transitions that exist in the theoretical plane, research design and data gathering (GONZÁLEZ, 2010). In this sense, Grounded Theory -GT- lends real utility to research from a critical stream as it allows deep formulations of social reality in which the studied didactic phenomenon occurs (RAMOS, 2017).

The research design is qualitative, and the data collection, analysis and interpretation phases were done in an interactive way to generate data-based theory (FLICK, 2015; MENDIZÁBAL, 2006; RUIZ, 2012). The methodology and procedures used for research come from GT in their systematic design. Strauss and Corbin (1998) pose that GT is a general methodology to develop theory based on methodically analyzed and gathered data. In agreement with Soneira (2006), this modality consists of a group of analytical steps to guarantee the construction of a theory. Furthermore, it offers researchers tools to manage great quantities of data and to relate concepts or constitutive elements of an emergent theory. The central procedures that the model developed by Strauss and Corbin (2002) offer are the Constant Comparative Method -CCM-, Theoretical Sampling -TS-, and the data encoding process -open, axial, and selective-.

Context and participants description

Fieldwork in Chile was done between March and June of 2019 and encompassed the Biobío, Araucanía, Los Lagos and Los Ríos regions. The selection of these territories is due to the fact that the schools in which the teachers teach are historically characterized as Ngulumpamu – present-day Chile – which is part of the Wallmapu – Mapuche country.

Of the 26 teachers -13 male and 13 female- that participated in the study, only 6 self-identify with the Mapuche people. Their professional experience of the participants in this context is characterized by a strong concentration in the initial sections ranging from 0 to 10 years of experience -19 teachers. While 7 teachers have developed their professional careers between 11 and more than 30 years. The initial training of the teachers was as follows: 14 teachers possess a general training and in practice have to teach every or almost every subject. On the other hand, 12 teachers are specialized in History and Geography and prepared to teach in high school but have developed their careers mainly in primary education given more working opportunities. Teachers who participated of interviews and observations will be referenced as PF and an assigned number -PF1-. On the other hand, those who have participates in questionnaire application will be identified with the term CH and an assigned number -CH1.

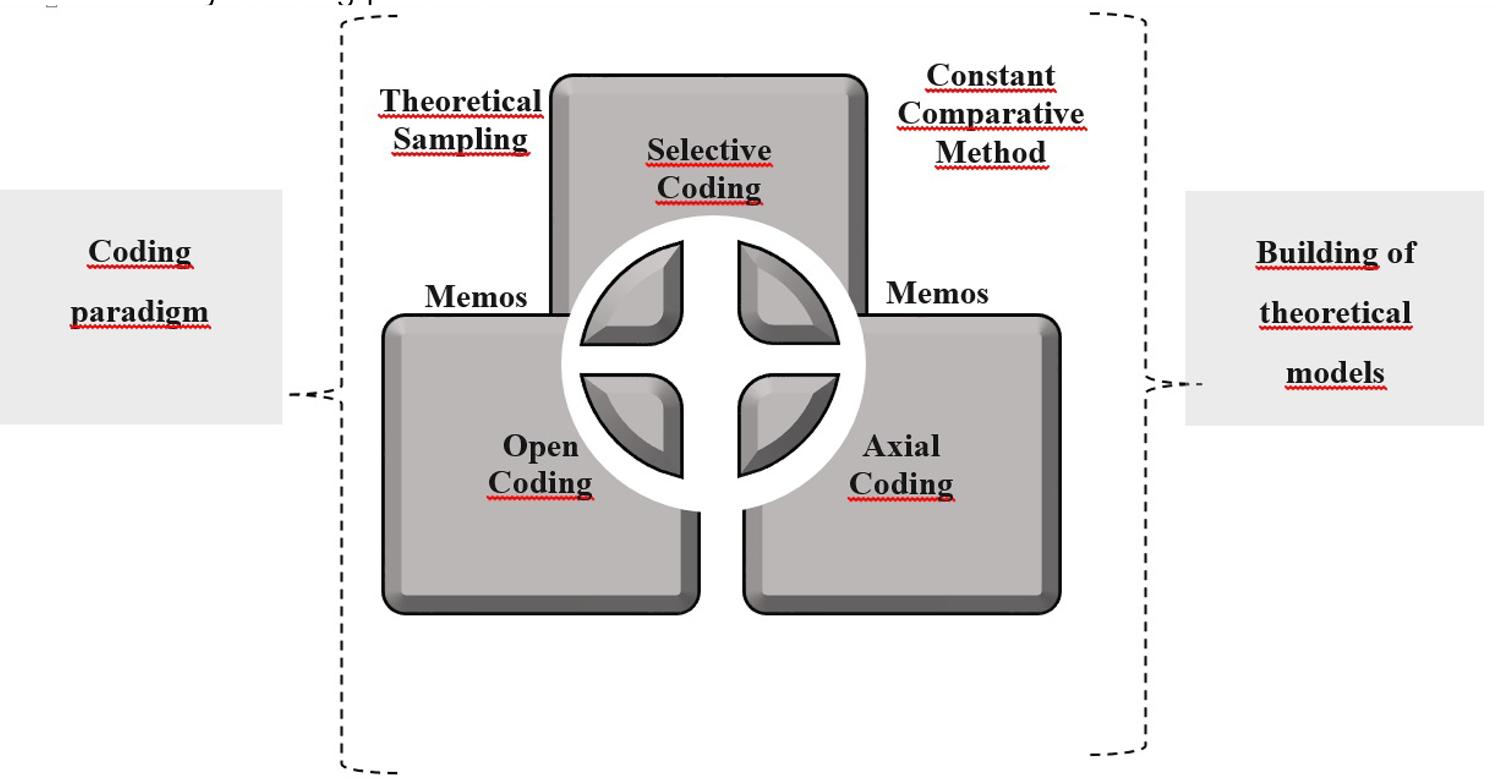

Next, we will explain the way in which the structure -components of GT- are integrated into the process of the specific research project carried out. To this end, we will use the concept of encoding paradigm to explain the organizational scheme of every procedure used to develop a theorical flow that allowed the emergence of a substantive theory on social invisibility of the Mapuche people in the history and Social Studiess curriculum. Thus, the procedures described are not static and, on the contrary, they are done simultaneously.

The encoding paradigm in the theorization flow

In this research the TS is developed in the field of study motivated mainly by the discovery and depth of the concepts and the theories more than by the participants per se (CORBIN; STRAUSS, 2015). TS in research is a loop that develops a relationship between the analysis questions, information gathering, and concept development.

El MT en la investigación es un bucle que desarrolla una relación permanente entre las preguntas de análisis, la recolección de información y el desarrollo de conceptos.

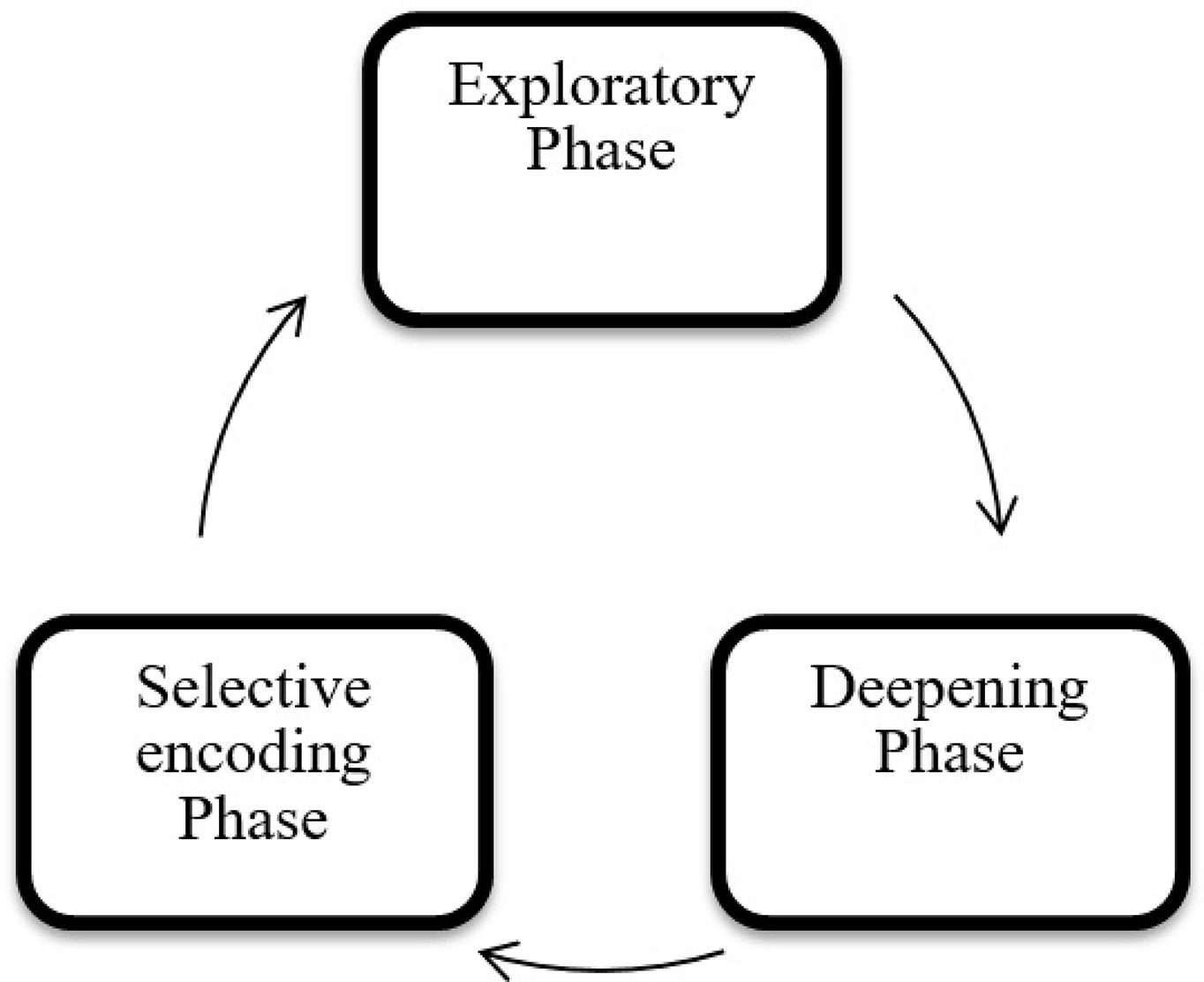

In our study the TS was done in three interconnected stages that evolved in accordance with our analysis of the instruments and the concepts we unveiled. The designed stages were: 1) exploration; 2) deepening; and 3) selective encoding (Figure 1)

The first exploration phase was done through the application of questionnaires to twenty-six teachers that taught Social Studiess in primary education -in the above-mentioned regions-. The instrument was designed based on prior research projects and specialty doctoral theses and, also, taking as reference the changes done by area specialists. Strauss and Corbin (2002) explain that the interaction of qualitative and quantitative methods must be selected taking as reference the construction of the emergent theory. For this reason, the questionnaires were utilized to explore what the teachers thought about: 1) the place of the Mapuche people in the school curriculum; and 2) to orientate the theoretical sampling towards happenings, places and people that will expand the meaning of categories.

The deepening phase was done based in the first analysis of the questionnaires. Through this analysis diverse concepts, properties and dimensions emerged that helped us select different teachers in different locations. The purpose of this action was to maximize the comparative possibilities and, in this way, give more depth to the theorical flow. Thus, we performed interviews in depth to six teachers to delve on the place the Mapuche people has in the area curriculum (KVALE, 2011).

Besides, in this stage we made field annotations through participant observation to two male and one female teacher (GOETZ; LE COMPTE, 1988).

In the last phase of selective encoding, we systematized the qualitative data from the questionnaires, the interviews, and the field notes. The reason to triangulate the data in this phase is the potential that exists to capture the different meanings and senses for formal theory generation (FLICK, 2014).

The theory building process in Grounded Theory

In our research the methods of Grounded Theory reciprocally mold in data collection and analysis, and, in this sense, the TS is inseparable from the CCM to develop the theory (CHARMAZ, 2013). To our research, the CCM allows real utility because it remains in constant tension with the TS and allows to manage the different types of data we obtained through the search for concepts and, furthermore, for the process of fragmentation and generalization of the analysis to build a continuous theorical flow in the development of categories and concepts (CORBIN, 2016).

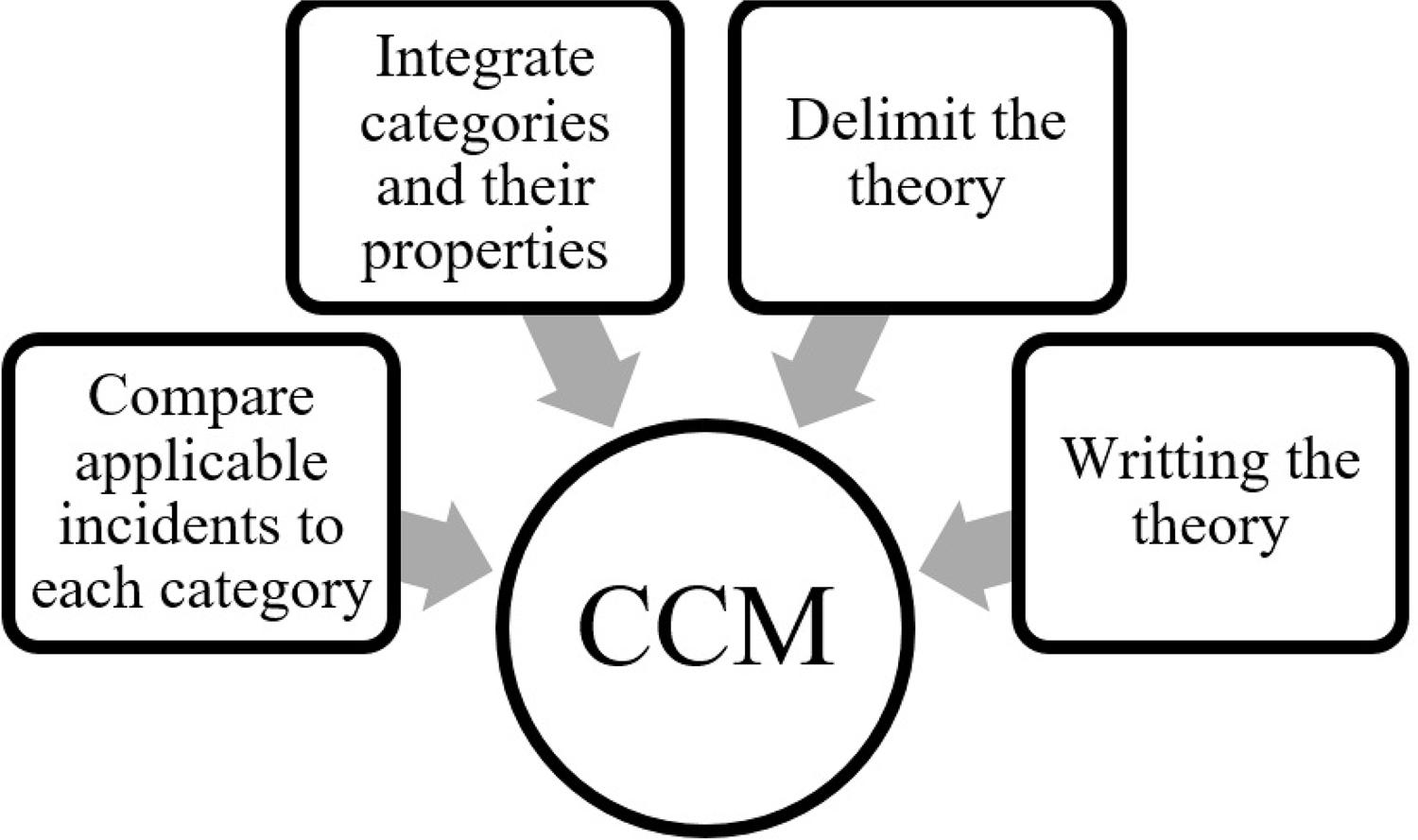

The CCM in our study combines an analytical comparison process and a process of theorical development to generate theory in a systematic manner. To this end we follow the steps proposal of Glaser and Strauss (2006) who propose a continuous or layered process that allow the increase of saturation of the substantive theory (Figure 2).

Abela, García-Nieto and Pérez (2007), mention that substantive theory is that which is elaborated through empiric research in a specific area. In the case of our research, we understand theory as a set of categories and subcategories that are related and form a network that contributes to explain the social invisibility phenomenon of the Mapuche people in the teaching of Chilean history (STRAUSS; CORBIN, 2002).

Soneira (2006) and Gibbs (2012) point that through CCM the researcher chooses, codifies, and analyzes data in a simultaneous way to generate theory. Strauss y Corbin (2002) indicate that the codifying stage is divided in: 1) An initial reading of the text to identify concepts, properties, and dimensions -Open codification.; 2) A secondary stage of accuracy, development and systematic relation of the categories and subcategories by using associative, contradictory or causal relationships between people, contexts or structures -Axial codification-; and 3) A final stage of integration a refining of theory through the development of central categories connected to subcategories to form theory (Figure 3).

One of the most important challenges in our research was to move forward from a description to a theory that explains the social invisibility of the Mapuche people in the teaching of history. In our perspective, the theories start essentially with concepts. The TS in our research process observes words, incidents, things, events, and people. That is, categories or mainly concepts. The theorical exercise in the TS has the purpose of finding that which underlies to the particular and finds sense in the general. Seen this way, for example, interviewed teachers represent a set of traits and properties that are correlated to their individual experiences around the vicissitudes of teaching, achievements, political identity or feelings. The concepts and categories obtain there a fundamental importance in our research because these experiences that each teacher carries share certain common elements that are labelled in categories or properties that characterize traits. Thus, the concepts provide bridges between the participants and between the participants and the world (CORBIN; STRAUSS, 2015; PACKER, 2013).

The analysis procedure was done through the ATLAS.TI software that contributed to three fundamental processes in the elaboration of the theory that, as mentioned by San Martín (2014), facilitates managing information for the analysis of primary documents -interviews, observations and questionnaires- in a sequential manner during the project. The analysis through theorical coding -open, axial, and selective coding- and the use of memos and in vivo codes support the reflection on data, and the analysis itself, in the theorical flow. Lastly, the use in the software of the conceptual network function allowed to relate the codes, subcategories and categories through conditions, contexts and dimensions to create data-based explanatory models (COFFEY; ATKINSON, 2003).

Based in this theorical process, we developed a theorical/explanatory model of the thinking of the teachers about the social invisibility of the Mapuche people in the Chilean history and Social Studiess primary school curriculum (Table 1).

Results

In the process of analysis done through the TS, CCM and theorical coding five triangulation categories emerged from the data obtained through questionnaires, interviews and observations (Table 2).

Table 2 Teacher quotes

| Categories | Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1- Official knowledge policy | |

| 2- Invisibility of the Mapuche history and memory | |

| 3-Training of teachers | |

| 4- Obstacles and posibilities for social change | |

| 5- Teachers as controllers of the curriculum |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

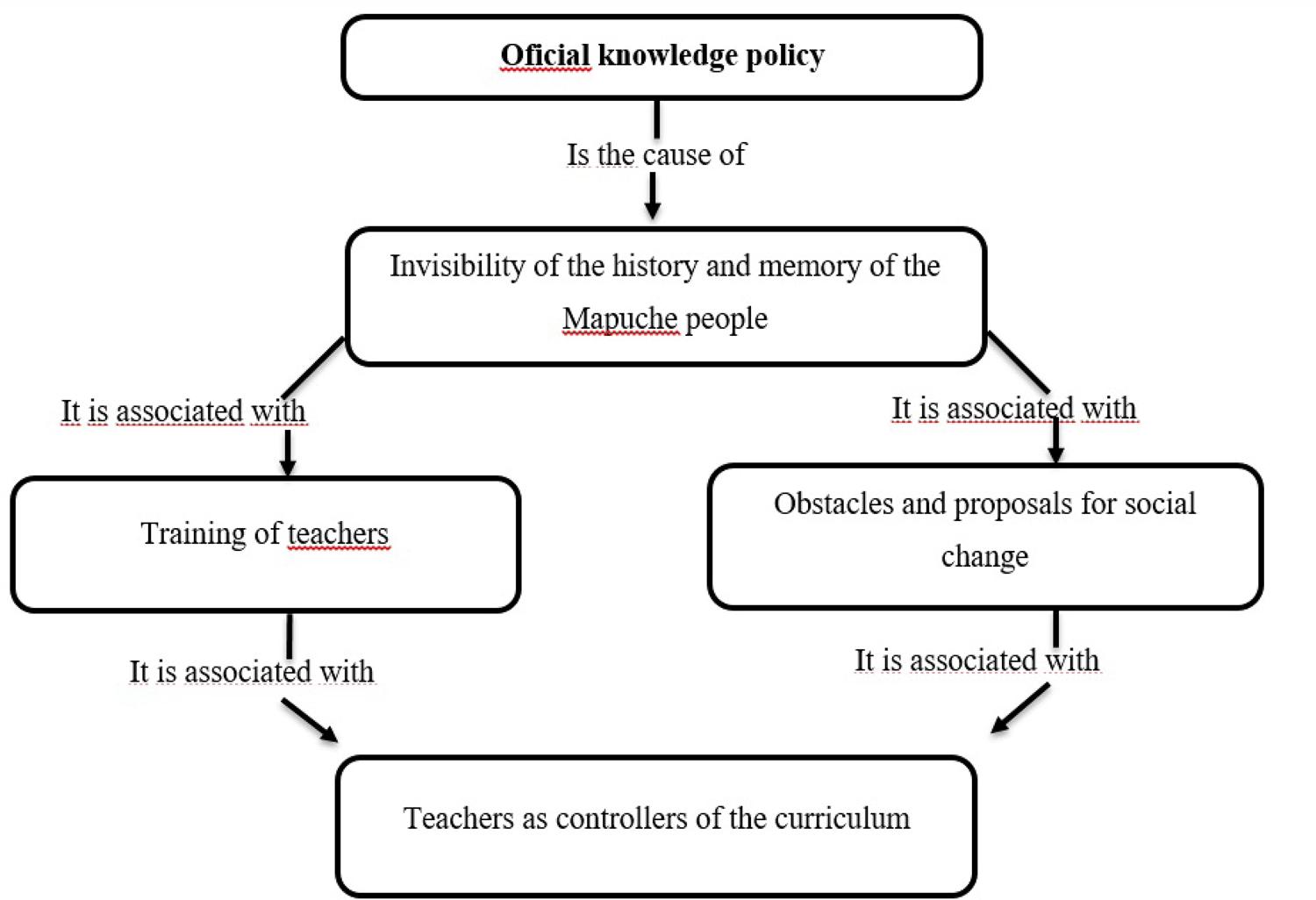

Below we present and develop an explanatory model based on what teachers say about the place the indigenous people in the school history curriculum. The explanatory model was designed based on the purposeful relations -related with/it is cause of- between the central category and the subcategories (Figure 4).

Official knowledge policy

Teachers say that the place of the Mapuche people in the curriculum is conditioned by the interested treatment received by its history and culture. “The official knowledge policy” brings together the meanings given by teachers to political intentionality, and which is characterized for having the following three properties: 1) Subalternity of Mapuche memory on territorial dispossession; 2) Evasion by the Chilean State of its responsibilities on the current conflict between societies; and 3) Production and distribution of social representations in Chilean and Mapuche society.

Teachers mention that “The oficial knowledge policy’s” purpose is to subordinate the memory of the Mapuche people and its role as a social actor in public life. The interested treatment given to the Mapuche people content acts as a control exercise and defines the history that is or isn’t taught. The purpose of these actions would be to hide Chilean State responsibilities on the territorial and human dispossession experienced by the Mapuche people. Some of the teachers mention the following:

I believe the State should take responsibilities it does not want to. Then, to admit errors that they -the State- have committed would be serious. It is better not to investigate any further and that the topic -in the curriculum- stays floating. (Personal interview PF1, March 18th, 2019).

Very Little importance is given to the primary education curriculum. And that has only to do with public policy. But that is directly related with the people that are in Government, and more specifically, in the Ministry of Education. Why don’t they want it to be known? Why don’t they want it to studied and analized? Or that the historic processes of the Mapuche people are interpreted? (Personal Interview PF5, April 18th, 2019).

But I believe they do not tell us those things because it is not convenient for the State, the curriculum, or the Ministry of Education to mention all the atrocities that we suffered as people. (Personal interview PF3, April 25th, 2019).

According to the teachers, the purpose of the “Official knowledge policy” is to “Invisibilize the Mapuche history and memory”. This category is characterized for explaining the following processes: 1) Mapuche people invisibility in the curriculum; 2) factors/instruments that produce curriculum invisibility; and 3) the effects of the invisibility in student learning. Teachers say that “The invisibility of Mapuche history and memory” is produced: “By curricular requirements” (CH23), this means that, even when the Mapuche issue is openly debated in society and arouses conflict and controversy, it is not possible to discuss at school. Besides, teachers say that there are factors and instruments that determine its undervaluation, such as the vast amounts of content in the curriculum and what standardized tests evaluate: “It is not that is irrelevant, but schools concentrate on standardized tests” (CH24). The factors/instruments such as the expanse of the curriculum and national-level standardized tests are instruments which objective is to control or align what is or is not taught with the “Official knowledge policy”:

The main issue with the current history curriculum is how extensive its units are, and how it privileges scholarly knowledge. This is why, to cover in an effective way a Mapuche unit is almost impossible, because they are not deeply evaluated by standardized tests. (CH22).

Teachers mention that “The invisibility of Mapuche history and memory and the Official knowledge policy” contribute to students not understanding what happens in the world through History and Social Studiess, but what’s more, to build caricatures about the Mapuche people:

[…] the only unfortunate thing is that sometimes boys and girls fail to understand what is happening. Because the issue of Camilo Catrillanca -murdered by Chilean pólice- generates a tensión between the Mapyche issue and on the other side the issue with Chilean Carabineros (police) that is supposedly an institution that safeguards peace, then it is a paradox to them and many times it is not understandable. (Personal Interview PF6, March 14th, 2019).

[…] what I have seen, at least, is a caricature of the Mapuche people. Like the indigenous with its primitive characteristics as a warrior, as a fighter, staying in a state of war. That is the depiction shown in the textbooks. (Personal Interview PF2, May 17th, 2019).

“The invisibility of the Mapuche history and memory” is related to teacher training and with the obstacles for social change. In our analysis, teacher’s mention that their training does not answer to the challenges posed by the classroom or does not prepare them to deal with the Mapuche issues. Based on what they state, the category on training is characterized by: 1) Poor historic or cultural training regarding the Mapuche people; 2) Difficulty to address and to answer what to teach or what I would like my students to learn; and 3) A set of answers/solutions that teachers think and say might be included in training.

Teacher training regarding history and culture of indigenous peoples, and specifically the Mapuche people is scarce. “In Universities little or nothing is taught about indigenous peoples”. (CH11). Other teacher say that: “As teacher I consider that I do not have enough knowledge about the Mapuche issue, I have not delved in the study of the subject and maybe I should perfect myself in that area” (Personal Interview PF1, March 18th, 2019). The lack of preparation mentioned by teachers becomes an obstacle to make visible Mapuche history and memory, because if they consider not to possess enough knowledge on the history or culture it is not possible to delve or design learning activities beyond the curriculum requirements:

Many teachers do not have knowledge about indigenous peoples and their culture, less about the reasons of their current problems, thus they deprive their students of participating in instances of profound reflection on these issues. (CH7).

The poor preparation of teachers in Mapuche history and culture makes it a complex task to make students understand current problems: “At present, there have been big conflicts that are difficult to understand if you do not know the events that generated the problem” (CH15).

The third dimension of teacher training considers a series of proposals/solutions that emerge from practice. Teachers believe it is necessary to include current conflicts and Mapuche memory so boys and girls understand the problems of the reality that surrounds them: “It is necessary to incorporate the complex history to understand the current reality of conflicts and to contribute to their solution” (CH17). Introducing the present conflicts in teacher’s training answers the “[…] reality of our territories which have yet not been solved, further considering that the Mapuche cause is just” (CH24). This way, it would make sense of what happens in the student’s world, “To contextualize the current and past problems, nurturing critical thinking” (CH3). One of the teachers explained that knowing Mapuche culture allowed to transform his teaching: “My experiences indicate it, I grew up in a Mapuche context, but to be immerse in its culture and to be able to know it further, I fell I understand them better and can give them another perspective in my classes” (CH2). In short, teachers say that:

I believe that, if this was to be incorporated, as teachers we would have more knowledge and tools to teach the topic adequately. Oftentimes we do not delve in it because teachers do not feel themselves sufficiently competent to teach this content to their students. At the same time, the Mapuche issue is relevant to our history, not only past but present. (CH6).

We organized the obstacles and proposals for social change around what teachers say about some factors that contribute to “Invisibility of Mapuche history and memory”. One of the obstacles that teachers claim to face is the low recognition diverse educative communities give to Mapuche history and culture:

Unfortunately, society in our country nowadays does not accept it in a good way. For example, we are here in the south of Chile implementing every year as a State policy the teaching of Mapuzungun -Mapuche language- in primary school. From first and second grade to the detriment of teaching English. But one here has conversations, and as the town, the community is quite small, one talks with parents and tutors. What do you think of this or that? They were displeased, very angry, about taking away periods of English to teach Mapuzungun. (Personal Interview PF4, March 16th, 2019).

We related the second dimension of obstacles and proposals for social change with what teachers say to could generate societal transformation. Suggestions are oriented to the involvement of families or educative communities, the inclusion of Mapuche knowledge across the different curriculum and in teacher training, and the approach to build intercultural schools:

[…] we must work with society, with parents and tutors. It would be advisable to start teaching this to the youngest, but together with teaching the family. To explain them why this is done and that they also join. Let’s start where we are involved, in an area of indigenous people. (Personal interview PF4, March 16th, 2019).

We should generate cultural change. I believe that in Chile we need a cultural change, and we should do it. (…) to see what we can start to intervene in the national curriculum in regard to the indigenous peoples, especially the Mapuche. Nowadays there are schools that are dedicated to the Mapuche cultural issue, they designate themselves as intercultural. (Personal Interview PF5, April 18th, 2019).

Lastly, education transforms this society. That I have as a dream. These people that develop the policy frameworks, or the curriculum bases, or study plans if they can modify or adapt in this way, I believe that education can better society. But that must reach State o Government-level discussion. That would be my most positive aspiration. (Personal interview PF3, April 25th, 2019).

We built the characterization of teachers as controllers of the curriculum based on asking and observing the way in which teachers give life to the curriculum, but also, from the reflections they make after class is over. Based on field notes, teachers treat Mapuche themes in accordance with the place given by the curriculum. That is, they follow the official curricular itinerary and teach Mapuche history or culture when the learning objectives from the “Official knowledge policy” mention them. Those learning objectives give visibility to a Mapuche history or culture linked to colonial history or the setting of the Chilean national territory in the XIX century. For example, a teacher after finalizing his class said that: “[…] as teacher I have to prioritize and observing, teaching further than what the curriculum allows” (Personal interview PF6, March 14th, 2019). So, even when the space to deal with the Mapuche issue is minimum, teachers do make efforts to delve in the subject for two reasons. The first reason has to do with the sociocultural context in which they teach -Mapuche context- and, secondly, to answer questions that emerge from students given the violence episodes that shake the context and public opinion.

Context is fundamental to teaching and encourages to delve in topics that affect the daily life of students. However, according to our field notes, standardized tests give meaning to the emphasis teachers give to contents. Therefore, social reality is the source -preferably- from which questions from students emerge to understand the present:

Here in the zone in which we are located the topi cis important. Because I have a fairly large group of students from indigenous ancestry, in this case Mapuche or Huilliche. (Personal interview PF4, March 16th, 2019).

[…] children ask: teacher, what is going on? Specially here in Chile last year because of the Camilo Catrillanca situation. Teacher why did that happen? Where does all this come from? Children ask and one must be apt to be able to answer and maybe leave other content aside and delve into that. (Personal interview PF6, March 14th, 2019)

Lastly, this category is influenced by the “Official knowledge policy” and the mechanisms that produce “Mapuche histoty and memory invisibility”. In practice, teachers control the curriculum, mainly conditioned by the poor training on Mapuche history and culture, which makes it difficult to address the Mapuche issue in the teaching of history.

Discussion and conclusions

The article attempted to develop a substantive-level theory on the process of social invisibility of the Mapuche people in the teaching of history in Chile, taking as reference the voice of teachers of primary education. From this objective, we used the social invisibility category from critical social philosophy to understand how social negation -recognition- materializes itself in the History and Social Studiess curriculum. The theory we developed recognizes the political character of education which implies an interested selection of contents and meanings with hegemonic purposes (APPLE, 2016; GIROUX, 2003). The process of selection that happens in the teaching of history is not partial:

[…] and it hides many of the main characters of history, that avoids dealing with existing conflicts in any country, that presents others -the other nations, the other people- as responsible of the evils that have happened to them, etc. (PAGÈS, 2007, p. 208).

Teachers say that social invisibility of the Mapuche people is due to a politically interested treatment that happens in three levels. Meaning, “that official knowledge policy” produces the Mapuche people social invisibility in: 1) the History and Social Studiess; 2) initial training; and 3) in undervaluation of its role as social actors in public life. Research related to the social invisibility of the Mapuche people in the curriculum and school textbooks explain that being invisible is not a synonym of lack of historical content, or from a lack of research in the diverse areas of references from Social Sciences. On the contrary, it is correlated with the control of meaning and the production and distribution of unilateral representations (SANHUEZA; PAGÈS; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, 2019b; PINOCHET; URRUTIA, 2016; VILLALÓN; PAGÈS, 2015; PAGÈS; VILLALÓN, 2013). “The official knowledge policy” makes invisible the history and memory of the Mapuche people by means of fixing what history should be taught, by producing caricatures -violent, resistant or warrior- and, in short, to devalue the importance of the content through the emphasis given in standardized tests (SANHUEZA et al., 2018).

The results on teacher training and the proposals that emerge from the practice for social change join a series of research that consider that the specificity of the Mapuche context is a requirement that does not answer the needs of teachers to face daily practice (TURRA, 2015; TURRA; FERRADA, 2013). Furthermore, teachers say that it is important to include the educative communities to generate changes in social representations. Thys, it becomes necessary to train teachers that are able to question social reality to transform the teaching of History and Social Studies (SANTISTEBAN, 2015).

The substantive theory we built maintains that the social invisibility of the Mapuche people is a social construction which objective is to hide the Mapuche knowledge or their perspective to make them invisible in the social space. As Le Blanc (2009) and Honneth (1997) indicate, social invisibility weighted on the Mapuche people dehumanizes them and negates their participation in public space such as education or the classroom. But, furthermore, following the ideas of Brighenti (2007), “the official knowledge policy” contributes to build and fix certain social representations with a negative charge.

Teachers are conscious of this thinking and manipulate the curriculum and try to answer the questions their students have about social reality. However, this is hampered by the lack of disciplinary training and other diverse mechanisms used by the “Official knowledge policy for the invisibility of the Mapuche history and memory”. In this sense, it is a challenge in the training of teachers to try and understand how the political and ideological character of education creates social invisibilities to homogenize social life. To this end, it is necessary to research the social invisibilities through what teachers think, what students learn, and the impact generated by the expression of social submission to those who become invisible.

REFERENCES

ABELA, Jaime; GARCÍA-NIETO, Antonio; PÉREZ, Ana María. Evolución de la Teoría Fundamentada como técnica de análisis cualitativo. Madrid: CIS, 2007. [ Links ]

ANGUERA, Carles et al. Invisibles y ciudadanía global en la formación inicial. In: LÓPEZ, Esther; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; SÁNCHEZ, María (ed.). Buscando formas de enseñar: investigar para innovar en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid / Aupdcs, 2018. p. 413-422. [ Links ]

APPLE, Michael. Ideología y currículo. Madrid: Akal, 2016. [ Links ]

BOURDIN, Jean Claude. La invisibilidad social como violencia. Universitas Philosophica, Bogotá, v. 27, n. 54, p. 15-33, jun. 2010. [ Links ]

BRIGHENTI, Andrea. Visibility: A Category for the Social Sciences. Current Sociology, New York, v. 55, n. 3, p. 323-342, may. 2007. [ Links ]

CARTES, Daniela. Las representaciones de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la periodización en contextos de diversidad étnica: la cosmovisión mapuche. Estudio de casos de escuelas de la región de la Araucanía, Chile. Barcelona: UAB, 2021. 281 p. Tesis (Doctorado en Educación) – Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2021. [ Links ]

CERECER, Osvaldo; PAGÈS, Joan. Los actores invisibles de la historia: un estudio de caso de Brasil y Cataluña. In: PAGÈS, Joan; SANTISTEBAN, Antoni (coord.). Una mirada al pasado y un proyecto de futuro: investigación e innovación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Barcelona: Aupdcs / Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2013. p. 37-44. [ Links ]

CEREZER, Osvaldo. Ensinar história afro-brasileira e indígena no século XXI: a diversidade em debate. Curitiba: Appris, 2019. [ Links ]

CHARMAZ, Kathy. La teoría fundamentada en el siglo XXI: aplicaciones para promover estudios sobre la justicia social. In: DENZIN, Norman; LINCOLN, Yvonna (coord.). Estrategias de investigación cualitativa. v. 3. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2013. p. 270-325. [ Links ]

COFFEY, Amanda; ATKINSON, Paul. Encontrar el sentido a los datos cualitativos: estrategias complementarias de investigación. Antioquia: Universidad de Antioquia, 2003. [ Links ]

CORBIN, Juliet. La investigación en la Teoría Fundamentada como un medio para generar conocimiento profesional. In: BÉNARD, Silvia (coord.). La Teoría Fundamentada: una metodología cualitativa. México, DC: Universidad Autónoma de Aguas Calientes, 2016. p. 13-54. [ Links ]

CORBIN, Juliet; STRAUSS, Anselm. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory, New York: Sage, 2015. [ Links ]

CUBILLOS, Froilan. Conocimiento territorial ancestral de las comunidades Mapuce Bafkehce del Aija Rewe Fvzv Bewfv Mapu Mew. 2015. 201 p. Tesis (Doctorado en Educación) – Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2015. Disponible en: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/384601 Acceso en: 15 ag. 2020. [ Links ]

FLICK, Uwe. El diseño de la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata, 2015. [ Links ]

FLICK, Uwe. La gestión de la calidad en la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata, 2014. [ Links ]

GIBBS, Graham. El análisis de datos cualitativos en investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata, 2012. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. Pedagogía y política de la esperanza: teoría, cultura y enseñanza. Una antología crítica. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2003. [ Links ]

GLASER, Barney; STRAUSS, Anselm. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction, 2006. [ Links ]

GOETZ, Judith; LECOMPTE, Margaret. Etnografía y diseño cualitativo en investigación educativa. Madrid: Morata, 1988. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ, Gustavo. La teoría entre teoría y campo de investigación en la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In: ÁVILA, Rosa María; RIVERO, María Pilar; DOMÍNGUEZ, Pedro (ed.). Metodología de investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Zaragoza: IFC/UPDCS, 2010. p. 167-174. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, Neus; PAGÈS, Joan; SANTISTEBAN, Antoni. ¿Quién protagoniza la historia? Análisis de los relatos históricos del alumnado de educación primaria y secundaria. In: HERNÁNDEZ, Ana María; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; DE LA MONTAÑA, Juan Luis (ed.). Una enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para el futuro: recursos para trabajar la invisibilidad de personas, lugares y temáticas. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura/ Aupdcs, 2015. p. 801-812. [ Links ]

HEIMBERG, Charles. Réflexions pour une didactique de l`histoire des invisibles. In: HERNÁNDEZ, Ana María; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; DE LA MONTAÑA, Juan Luis (ed.). Una enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para el futuro: recursos para trabajar la invisibilidad de personas, lugares y temáticas. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura / Aupdcs, 2015. p. 635-647. [ Links ]

HONNETH, Axel. La lucha por el reconocimiento: por una gramática moral de los conflictos sociales. Barcelona: Crítica, 1997. [ Links ]

HONNETH, Axel. La sociedad del desprecio. Madrid: Trotta, 2011. [ Links ]

KRÁL, Françoise. Social invisibility and diaporas in anglophone literatura and culture: the fractal gaze. New York: Palgrave: MacMillan, 2014. [ Links ]

KVALE, Steinar. Las entrevistas en investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata, 2011. [ Links ]

LE BLANC, Guillaume. L’invisibilité sociale. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2009. [ Links ]

MAROLLA, Jesús. La inclusión de las mujeres en las clases de historia: posibilidades y limitaciones desde las concepciones de los estudiantes chilenos. Revista Colombiana de Educación, Bogotá, n. 77, p. 37-59, 2019. [ Links ]

MAROLLA, Jesús. Sujetos-víctimas o sujetos-políticos: las concepciones de los y las estudiantes chilenas sobre los roles de las mujeres en la enseñanza de la historia y las ciencias sociales. In: LÓPEZ, Esther; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; SÁNCHEZ, María (ed.). Buscando formas de enseñar: investigar para innovar en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid / Aupdcs, 2018. p. 985-995. [ Links ]

MAROLLA, Jesús; PAGÈS, Joan. Ellas sí tienen historia. Las representaciones del profesorado chileno de secundaria sobre la enseñanza de la historia de las mujeres. Clío & Asociados, Buenos Aires, n. 21, p. 223-236, 2015. [ Links ]

MAROLLA, Jesús; PINOCHET, Sixtina; SANT, Edda. Los y las invisibles desde la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In: JARA, Miguel; SANTISTEBAN, Antoni (coord.). Contribuciones de Joan Pagès al desarrollo de la didáctica de las ciencias sociales, la historia y la geografía en Iberoamérica. Neuquén: Uncoma / UAB, 2018. p. 215-225. [ Links ]

MASSIP; Mariona; PAGÈS, Joan. Humanos contra humanos: la necesidad de humanizar la historia escolar. In: GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; ARROYO, Aurora; MEDIERO, Beatriz (coord.). Deconstruir la alteridad desde la didáctica de las ciencias sociales: educar para una ciudadanía global. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Entinema, 2016. p. 447-457. [ Links ]

MATOZZI, Ivo. La historia desde abajo en la historia general escolar. In: HERNÁNDEZ, Ana María; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; DE LA MONTAÑA, Juan Luis (ed.). Una enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para el futuro: recursos para trabajar la invisibilidad de personas, lugares y temáticas. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura / Aupdcs, 2015. p. 259-267. [ Links ]

MENDIZÁBAL, Nora. Los componentes del diseño flexible en la investigación cualitativa. In: VASILACHIS, Irene (coord.). Estrategias de investigación cualitativa. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2006. p. 65-106. [ Links ]

MERLEAU-PONTY, Maurice. Lo visible y lo invisible. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión, 2010. [ Links ]

ORTEGA, Delfín; MAROLLA, Jesús; HERAS, Davinia. Invisibilidades sociales, identidades de género y competencia narrativa en los discursos históricos del alumnado de educación primaria. In: DÍEZ, Enrique; RODRÍGUEZ, Juan Ramón (coord.). Educación para el bien común: hacia una práctica crítica, inclusiva y comprometida socialmente. Barcelona: Octaedro, 2020 p. 89-103. [ Links ]

PACKER, Martín. La ciencia de la investigación cualitativa. Bogotá: Uniandes, 2013. [ Links ]

PAGÈS, Joan. La educación para la ciudadanía y la enseñanza de la historia: cuando el futuro es la finalidad de la enseñanza del pasado. In: ÁVILA, Rosa María; LÓPEZ, José Rafael; FERNÁNDEZ, Estibaliz (ed.). Las competencias profesionales para la enseñanza-aprendizaje de las ciencias sociales ante el reto europeo y la globalización. Bilbao: Aupdcs, 2007. p. 205-215. [ Links ]

PAGÈS. Joan; SANT, Edda. Las mujeres en la enseñanza de la historia: ¿hasta cuándo serán invisibles? Cadernos de Pesquisa do CDHIS, Uberlândia, v. 25, n. 1, p. 91-117, 2012. [ Links ]

PAGÈS. Joan; VILLALÓN, Gabriel. Los niños y las niñas en la historia y en los textos históricos escolares. Analecta Calasanctiana, Madrid, v. 74, n. 109, p. 29-66, 2013. [ Links ]

PAGÈS. Joan; VILLALÓN, Gabriel; ZAMORANO, Alicia. Enseñanza de la historia y diversidad étnica: los casos chileno y español. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 42, n. 1, p. 161-182, 2017. [ Links ]

PINOCHET, Sixtina; URRUTIA, Nelson. Entre la academia y el aula: la aparición de actores marginados en la historia y su enseñanza. Revista de Historia y Geografía, Santiago de Chile, v. 34, n. 1, p. 135-156, 2016. [ Links ]

PLÁ, Sebastián. Currículum, historia y justicia social: estudio comparativo en América Latina. Revista Colombiana de Educación, Bogotá, n. 71, p. 53-77, 2016. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Juan Carlos. Usos y alcances de la Teoría Fundamentada en la investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In: MARTÍNEZ, Ramón; GARCÍA-MORIS, Roberto; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa (ed.). Investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales: retos, preguntas y líneas de investigación. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba / Aupdcs, 2017. p. 510-518. [ Links ]

RUIZ, José Ignacio. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto, 2012. [ Links ]

SAN MARTÍN, Daniel. Teoría fundamentada y Atlas.ti: recursos metodológicos para la investigación educativa. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, Tijuana, v. 16, n. 1, p. 104-122, 2014. [ Links ]

SANHUEZA, Alexis; PAGÈS, Joan; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, Neus. Enseñar historia y ciencias sociales para la justicia social del Pueblo Mapuche: la memoria social sobre el malon y el awkan en tiempos de la Ocupación de la Araucanía. Perspectiva Educacional, Valparaíso, v. 58, n. 2, p. 3-22, 2019b. [ Links ]

SANHUEZA, Alexis; PAGÈS, Joan; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, Neus. La historia mapuche en el currículo y en los textos escolares: reflexiones desde la memoria social mapuche para repensar la enseñanza del despojo territorial. Clío & Asociados, Buenos Aires, n. 31, p. 50-62, 2020. [ Links ]

SANHUEZA, Alexis; PAGÈS, Joan; GONZÁLEZ-MONFORT, Neus. ¿Qué formación reciben los futuros docentes que enseñarán historia mapuche? La formación inicial del profesorado en ciencias sociales en Chile y en Argentina. In: HORTAS, Maria João; DIAS, Alfredo; DE ALBA, Nicolás (ed.). Enseñar y aprender ciencias sociales: la formación del profesorado desde una perspectiva sociocrítica. Lisboa: Escola Superior de Educação / Aupdcs, 2019a. p. 864-871. [ Links ]

SANHUEZA, Alexis et al. Memorias del despojo mapunche y su implementación en ámbitos educativos: experiencia en la Escuela Trafún Chico, comuna de Panguipulli. In: POZO, Gabriel (ed.). Expoliación y violación de los derechos humanos en territorio mapuche: cartas del padre Sigifredo, misión de Panguipulli, año 1905. Santiago de Chile: Ocho Libros, 2018. p. 477-498. [ Links ]

SANT, Edda; PAGÈS, Joan. ¿Por qué́ las mujeres son invisibles en la enseñanza de la historia? Revista Historia y Memoria, Tunja, n. 3, p. 129-146, 2011. [ Links ]

SANTISTEBAN, Antoni. La formación del profesorado para hacer visible lo invisible. In: HERNÁNDEZ, Ana María; GARCÍA, Carmen Rosa; DE LA MONTAÑA, Juan Luis (ed.). Una enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para el futuro: recursos para trabajar la invisibilidad de personas, lugares y temáticas. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura / Aupdcs, 2015. p. 383-394. [ Links ]

SEIXAS, Peter. Indegenous historical consciousness: an oxímoron or a dialogue? In: CARRETERO, Mario; ASENSIO, Mikel; RODRÍGUEZ-MONEO, María (ed.). History education and the construction of a national identities. Charlotte: Information Age, 2012. p. 125-138. [ Links ]

SONEIRA, Abelardo. La “Teoría fundamentada en los datos” (Grounded Theory) de Glaser y Strauss. In: VASILACHIS, Irene (coord.). Estrategias de investigación cualitativa. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2006. p. 153-174. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, Anselm; CORBIN, Juliet. Bases de la investigación cualitativa: técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Antioquia: Universidad de Antioquia, 2002. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, Anselm; CORBIN, Juliet. Grounded Theory methodology: an overview. In: DENZIN, Norman; LINCOLN, Yvonna (ed.). Strategies of qualitative inquiry. London: SAGE, 1998. p. 158-183. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, John. La nouvelle visibilité. Réseaux, París, v. 129-130, n. 1, p. 59-87, 2005. [ Links ]

TOMÁS, Julia. La notion d’invisibilité sociale. Cultures et Sociétés, París, v. 16, n. 1, p. 103-109, 2010. [ Links ]

TURRA, Omar. Profesorado y saberes históricos-educativos mapuches en la enseñanza de la historia. Revista Electrónica Educere, San José, v. 19, n. 3, p. 1-20, 2015. [ Links ]

TURRA, Omar; CATRIQUIR, Desiderio; VALDÉS, Mario. La identidad negada: historia y subalternización cultural desde testimonios escolares mapuche. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 47, n. 163, p. 342-356, 2017. [ Links ]

TURRA, Omar; FERRADA, Donatila. La formación del profesorado en la lengua y cultura indígena: una histórica demanda educativa en contexto. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 42, n. 1, p. 229-242, 2013. [ Links ]

VILLALÓN, Gabriel; PAGÈS, Joan. La representación de los y las indígenas en la enseñanza de la historia en la educación básica chilena: el caso de los textos de estudio de historia de Chile. Diálogo Andino, Arica, n. 47, p. 27-36, 2015. [ Links ]

VILLALÓN, Gabriel; PAGÈS, Joan. ¿Quién protagoniza y cómo la historia escolar?: La enseñanza de la historia de los otros y las otras en los textos de estudios de historia de chile de educación primaria. Clío & Asociados, Buenos Aires, v. 17, n. 1, p. 119-136, 2013. [ Links ]

VOIROL, Olivier. Invisibilité sociale et invisibilité du social. In: FAES, Hubert et al. (coord.). L`invisibilité sociale: approches critiques et anthropologiques. Paris: L`Harmattan, 2013. p. 57-93. [ Links ]

VOIROL, Olivier. Présentation: visibilité et invisibilité: une introduction. Réseaux, París, v. 129-130, n. 1, p. 9-36, 2005. [ Links ]

* English version by Bora Hysi. The authors take full responsibility for the translation of the text, including titles of books/articles and the quotations originally published in Portuguese.

1- The data set that supports the results of this study is not publicly available, given the data confidentiality protocols. You may request access to the data directly with the author via e-mail at alexis.sanhueza.03@gmail.com. This work was supported by CONICYT BCH/DOCTORADO 72180226.

Received: September 10, 2020; Revised: February 09, 2021; Accepted: April 07, 2021

texto em

texto em