Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 21-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248243770por

ARTICLES

Meanings of education in distance learning advertising: from the process paradigm to the product paradigm*

1- Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Contact: eduardoar76@gmail.com

2- Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil. Contact: carmen.agustini@gmail.com

In this article, based on the theoretical-methodological framework of Discourse Analysis, we analyze advertising pieces that put distance learning (DL) on sale in the market. Such advertisements circulate socially – although not exclusively – in the online form. Our objective was to restore, by means of a discursive and materialist interpretative device, (re)interpretation conditions to the process of producing effects of meanings evocable in and through the referred advertising pieces. This restoration was carried out by focusing on how the meanings of education at stake in DL advertising shift the inscription of (distance) learning, moving it away from the process paradigm and leading it toward the product paradigm. This rendering process produces, as an effect, the projection of (distance) learning to the status of merchandise. By means of our analyses, we show that, as merchandise, DL advertising establishes discourses that aggravate the class struggle in neoliberal capitalist society by means of articulation and discursive transversality that (re)direct DL’s discursive reduction to professionalization, to effortlessness, to instantaneousness, to the digital form and to jobs, configuring DL as the “new normal” of/in education. Because of this discursive practice and its impact on society, the discursive devices operating in DL advertising produce a risk to the emancipation of the subject in and through (distance) learning.

Key words: Distance learning; Advertising; Neoliberalism; Discourse

Neste artigo, com base no quadro teórico-metodológico da Análise de Discurso, analisamos peças publicitárias que colocam em oferta, no mercado, a educação a distância (EaD). Essas peças circulam socialmente – embora não exclusivamente – na modalidade online. Nosso objetivo consistiu em restituir, por meio de um dispositivo de leitura discursivo e materialista, condições de (re)leitura ao processo de produção de efeitos de sentidos evocáveis nas e pelas referidas peças publicitárias, focalizando como os sentidos de educação em jogo na publicidade da EaD deslocam a inscrição da educação (a distância), afastando-a do paradigma do processo e aproximando-a do paradigma do produto. Esse processo de significação produz como efeito a projeção da educação (a distância) ao estatuto de mercadoria. Com as análises, mostramos que, como mercadoria, a publicidade da EaD instaura discursividades que acirram a luta de classes na sociedade capitalista neoliberal pela articulação e transversalidade discursiva, que (re)atualizam a redução discursiva da EaD à profissionalização, ao menor esforço, à instantaneidade, ao digital, ao trabalho, configurando a EaD como o “novo normal” da/na educação. Como consequência dessa prática discursiva e seu impacto sobre a sociedade, as discursividades que funcionam na publicidade da EaD produzem risco à emancipação do sujeito na e pela educação (a distância).

Palavras-Chave: Educação a distância; Publicidade; Neoliberalismo; Discurso

Introduction

In this article we discuss and analyze, from the viewpoint of the structure and functioning of language, what has regularly revealed itself (evidence of meaning) in processes of discursive construction of the meaning of education in distance learning (DL), which receive formulation and circulation in advertising pieces aimed at promoting higher-education DL institutions and courses. Although both public and private institutions offer DL, when we established our reading material archive, based on an interest in understanding how the neoliberal capitalist discourse is involved in DL advertising, we observed that there is a discursive inscription different in the advertising pieces to which we have had access. That difference lies in their origin, related to either public or private institutions.

Such a discursive inscription marks an affiliation to a region with dominance of meanings (discursive formation) that materialize in the formulation, at the point in which the play between “intradiscourse” and interdiscourse is established.3Our analysis focuses on the way in which such formulation forms and circulates, seeking to restore, to the linguistic surface, the semantic density that is specific to it, that is, to open this surface to the discursive process that renders its meaning, exhibiting the articulations and discursive latitudes (PÊCHEUX, 2011) that constitute it.

Advertisement pieces related to public institutions mostly furnish logistical information (application deadlines, courses offered, address for access to public notices, etc.). Nevertheless, traces of the neoliberal capitalist discourse already appear in some of their advertisements , as illustrated by the following formulations: “A universidade do seu tempo – Vestibular Univesp 2018”4 (The university of your days – Univesp Entrance Exam 2018), “Universidade pública ao seu alcance – Vestibular Univesp 2019”5 (Public university within your reach – Univesp Entrance Exam 2019), and “Vestibular 2º semestre Univesp – Ensino Superior Gratuito”6 (Univesp 2nd Semester Entrance Exam – Free Higher Education). In such formulations, meanings of education as a consumer good can be set in motion via the potential forms of interpretation, representing public education as a good that is modern, current, accessible and attainable in the reader/consumer’s days. As such, the prepositional phrase “do seu tempo” (of your days) plays with meanings of days such as modern and current times, and of time as the reader’s available time, as a potential student. In turn, “Ao seu alcance” (within your reach) and “ensino superior gratuito” (free higher education) (re)produce meanings of accessible, due both to being possible and feasible and to being free of charge.

Meanwhile, pieces related to private institutions are created as advertising, a genre adopted as proper in and by publicity discourse and recognizable by frequently presenting traits such as the presence of celebrities, slogans, and the assumption of an interlocutor/target audience. In theory, public institutions would not be commercial institutions, for they would not seek profit. Hence, they would not need to promote education commercially. As such, our analysis in the present article is limited to examining the advertisements of private institutions.

Therefore, the pieces we analyzed lie on a discursive process that sets in motion a metaphorical relationship that produces equivalence between education and consumer good; and, as a result, an implicit relationship between education and profession/employment, providing certain stability to the meaning of educate. From this perspective, educate would mean, for example, “provide the prerequisites for employability”, although no implicit relationship between “becoming a professional” and “being employed” is necessary or sufficient, as contended by certain discourses circulating in society. In other words, graduating from university does not guarantee employment.

As we shall see in the analysis, this metaphorical effect exposes the signification of/in the advertisement pieces to other possible discursive articulations (PÊCHEUX, 1999), occasioning a shift away from the meaning of education. This is the case especially through the determination of discursive formation that sustains discourses about the new technologies of information and communication (DIAS, 2009, 2018), hereafter referred to as NTICs, within the scope of which the effect of synonymy between knowledge and information is already crystalized. Thus, it can (re)appear in the formulations (in the publicity pieces) as established knowledge. Following the reasoning of Dias (2009), this effect is historically and ideologically fashioned by the manner in which the meaning of speed is regulated by the discursive formation that sustains discourses about NTICs.

In such discursive formation, the meaning of speed would, imaginarily, correspond to the binary superspeed, the instantaneous speed that circumscribes the here-now of “in real time,” in the speed that inscribes, already in the present, an exact futurity due to, as we shall see, certain implied relationships. As such, this effect of the meaning of speed suppresses the meaning of process (the process of producing knowledge, the process of professional training, the process of subjectivation, the historical process). As a result, it allows, on the one hand, the encapsulation of knowledge, i.e., knowledge turns out to be seen as mere (instantaneous) information. On the other, it also allows the encapsulation of the student’s education itself, reducing it to capacitation, qualification or mere training, that is, a know-how that is not based on comprehension and does not produce comprehension about what underpins such know-how, in such a way that the student remains an object in the knowledge-employment-society relationship (ORLANDI, 2014).

Adopting the perspective of language to analyze and understand the historical production of meanings about DL means focusing the reader’s eye to the semantic denseness of the advertising pieces that disseminate DL. This focus makes it explicit that the language employed and the effects thereby (re)directed function in and through opacity, thus producing the naturalization of the meanings placed in circulation by the advertisements. This mode of (re)interpreting the meaning of advertising pieces inscribes the present work into the theoretical-methodological practice of Discourse Analysis.

Does education (not) imply professionalization?

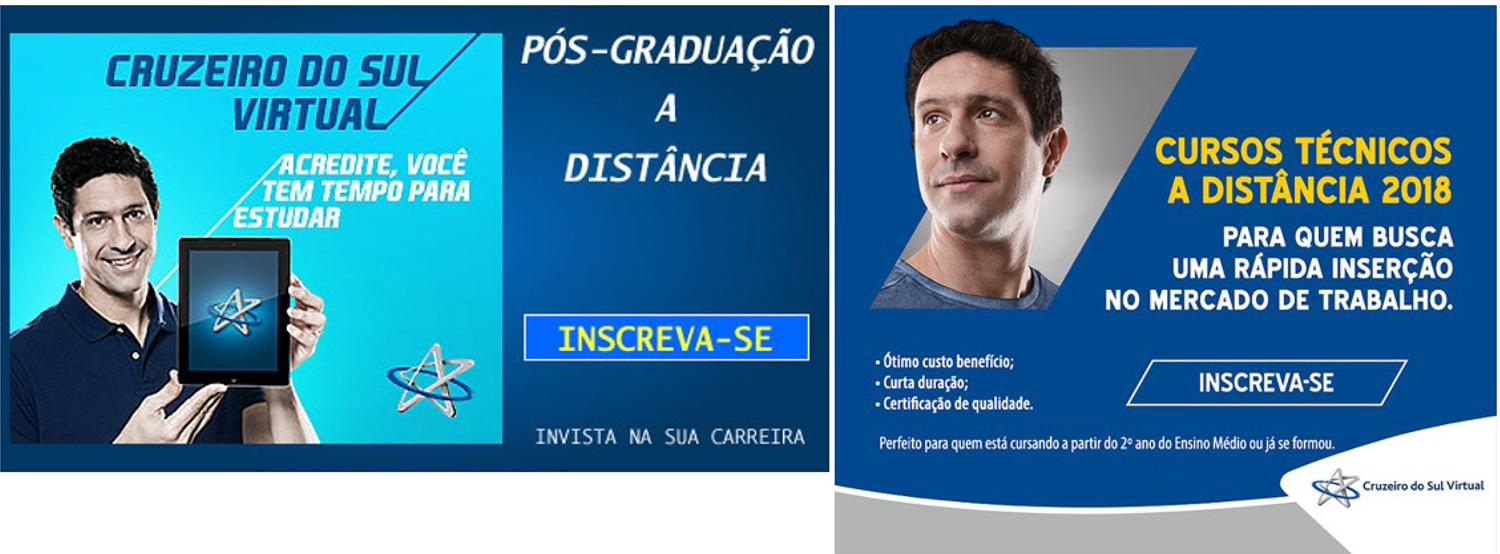

Analysis of the collection of advertising pieces contained in our reading material archive shows that they articulate decisive logical implications for the comprehension of their semantic functioning. In Figure 1, a logical implication receives exposure, as an effect of meaning, interpreted as follows: It is necessary to educate oneself and, by educating oneself, one becomes a professional; that is, by educating oneself, one becomes a professional.

Both advertisements in Figure 1 formulate the appeal – “inscreva –se” (apply) (for a university-level distance learning course). The command utterance summons the reader (target audience) to enroll in the logic of the discursive functioning that prevails in neoliberal capitalist discursive formation and that provides the reader with the articulation of certain transverse and pre-constructed discourses.8 It (re)produces coherence for the following evident fact: only education can transform your employment situation. In the current scenario, DL would provide anyone with the conditions necessary to affiliate to this evidence, thus becoming a consumer of education and, as a result, qualified for professional employment upon being absorbed into the (job) market.

This metaphorical effect can be interpreted based on the paraphrastic game that takes place in the following sequences:

a) Apply (for the university-level distance learning course)/invest in your career).

The paraphrastic relationship between “inscrever-se” (apply) and “investir” (invest) permits exposing the reader’s eye to the equivocal functioning of the verb “investir,” by which another memory network is put into action: that which stabilizes its reading-interpretation regulated by financial discursiveness, causing the utterance “inscreva-se” to enter the consumption domain, tying itself through cohesion to the neoliberal capitalist discourse. “Inscrever-se”, in this game, shifts to “investir,” which (im)mobilizes the reader in the field of investment in education/profession, in such a way that the meanings of profession are placed above the meanings of education, loosening the connection of the reader (potential student) with meanings relating to education as a process of preparation for life. One’s attention is directed toward preparation for employment, causing a shift from education to capacitation, qualification and training.

b) Go from one status to another (from unemployed to employed) / if employed, then you’ll enjoy better pay, a better career, etc.

The prevailing neoliberal capitalist discursive formation establishes a relationship of implication between “education” (university-level distance learning) and “getting a (better) job,” such that this relationship gains an effect of naturalization through discursive prägnanz9: One studies in order to have a profession and thus have the ability to enter the (job) market. Among the arguments, this relationship of implication (re)produces an effect of logical inference – those who study are (more) able to get a (better) job – and consequently class relations are aggravated. In Laval’s words (2019, pp. 13-14),

academic neoliberalism resulted, in fact, in a true war between classes to enter the “good schools” of an increasingly hierarchized and unequal school and university system. It is for this reason that analysis cannot be limited to the economic phenomenon of the commercialization of schooling, but rather extend to the social logic of “commodification” of the public school, which is tied to the generalized struggle between social classes in the school and university market.

When it limits the objective of education to professionalization and mere satisfaction of market demand, this implicative functioning (in the form of a logical inference) between “(university distance) education” and “getting a (better) job”, is established as an evidence. Such functioning sustains commonplace formulations, commonly heard in social interaction. An example is when parents tell their kids that they need to study in order to become someone in life, have a good job, have a good future. Or, in another example, in the classroom, when the students are surprised by hearing the teacher say that education does not aim exclusively at a professional practice.

c) If “(university-level distance) education,” then “getting a (better) job.” Conclusion: educating oneself is necessary.

The logical-inference effect that the relationship of implication between “(university-level distance) education” and “getting a (better) job” (re)produces the inferably unavoidable conclusion that “educating oneself is necessary.” And DL, imaginarily, is the mechanism for (providing the necessary conditions to the reader/consumer) to satisfy this need. Thus, the logically established conclusion sustains the call to “inscreva-se” (apply) and the advertising functions ideologically in the evidence of the meanings in a relationship of dominance in neoliberal capitalist discursive formation, (re)producing them and placing them in circulation in society.

Is education (not) merchandise?

By raising education to the status of merchandise10 so that education is attractive as such, the neoliberal capitalist discourse imposes upon it a specific social function that is restrictive and determined by the market logic: professional education, which must open the doors to the (job) market to its consumer. In DL, this social function is intensified, for time cannot be wasted.

Let us explain further: The current market logic, i.e., in the current scenario of the dominance of the NICTs (new information and communication technologies) and the paradigm of an online (digital) society, is the logic of the superspeed of time (DIAS, 2009), which presupposes building the boat when it is already on the water. In other words, (DL) students study and at the same time, they work. In this scenario, neither the (DL) student nor the market can find the time necessary for education. Hence, the capacitation – or qualification or training – is offered as a solution that rapidly provides a professional for the job and a job for the professional, such that both the market and the professional sphere are supposedly served. This discursive “metaphorization” – in which capacitation replaces education – promotes the effect of an appropriate fitting between DL and the market, forcing an unquestionable relationship of implication between studying and being employed, for it (con)figures itself as evident.

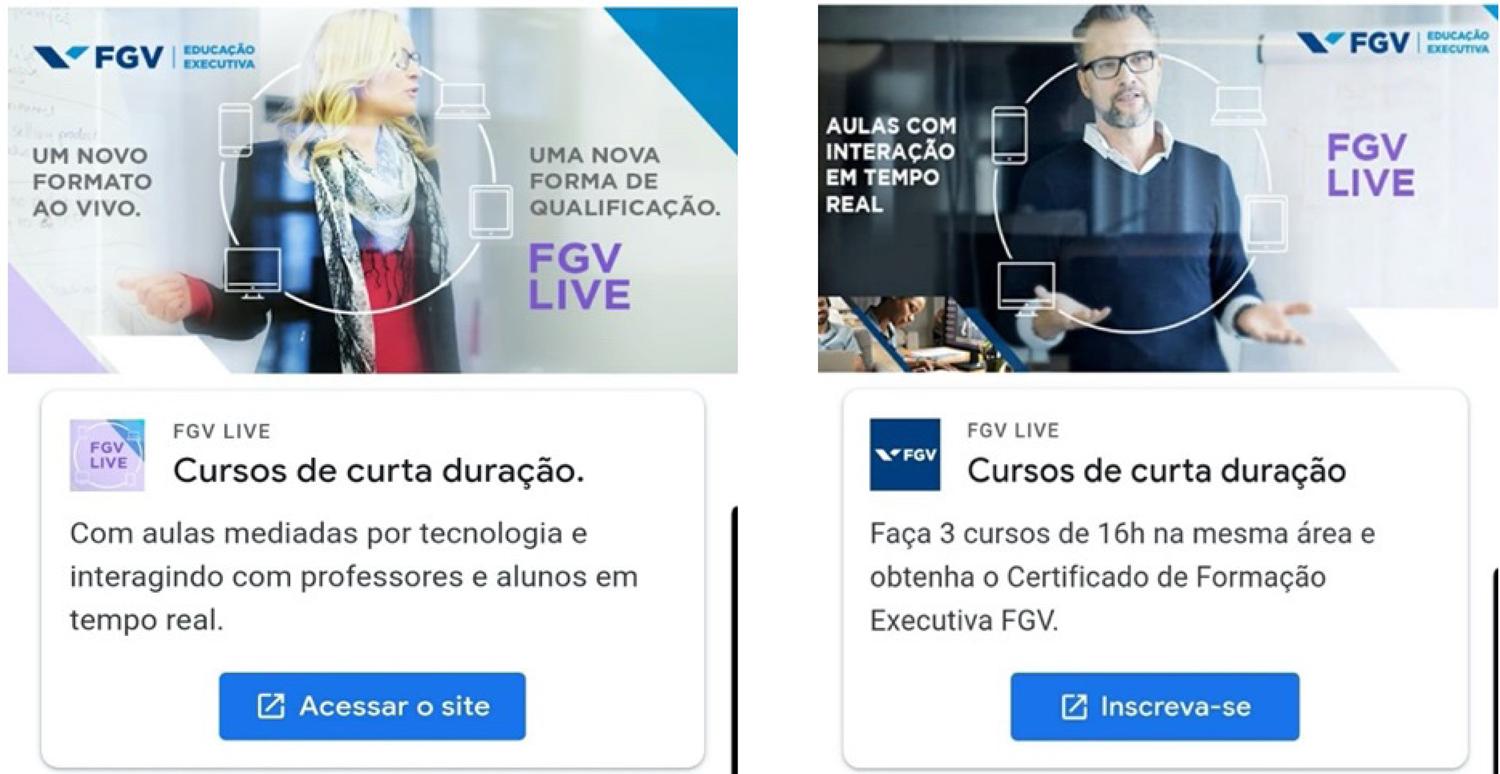

The DL student, as a consumer, faced with the offer of this type of education, “chooses” an institution not only based on the financial situation necessary to be a consumer in/of that institution for a certain amount of time, but also based on the quality of the product/merchandise that is offered. The DL student ultimately bases such a choice on the discursive articulation that (re)produces the logical inference between education (as a product/merchandise) and professionalization/employability, thus updating the following transverse discourse: The better the product, the better the job one can acquire. The circulation of advertising pieces sustained by supposed quality certifications is justified in this manner. In the advertisements in Figure 2, the assertion of such certification evokes pre-constructs that have an already supposed knowledge resulting from the discursive articulation mentioned above: The DL institution is certified by the quality it offers and the student is much better qualified for the market via such a DL institution.

A) Source: Google (https://painel.posestacio.com.br/assets/uploads/81/5dd03-estacio.jpg). B) Source: Google (https://unipguarulhos.com.br/macedo/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2018/11/top.jpg). C) Source: Google (https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/niusleter/etc_a2012m10n49/1.jpg).

Figure 2 Advertising pieces for the institutions Estácio and Unip

Also based on Figure 2, we can say that such discursive functioning materializes in several marks identified on the linguistic surface of the advertisements. The adjectives “preferida” (preferred) and “máxima” (top) function to predicate “Unip” and “ranking,” respectively, constructing the evidence that the institutions referred to – Paulista University (Unip) and Estácio, which offer DL as a product on the market – are those that offer the best product, i.e., the best DL and, by logical inference, the best prerequisite for entering the (job) market. Therefore, such functioning signifies that (distance) education11 must serve a professional purpose, preparing workers to satisfy the needs of the economy.

We can say that these discursive marks constitute “a lateral reminder of something that is already known from elsewhere” (PÊCHEUX, 1982, p. 73) and that they serve for considering the discursive object “DL as a good,” which simulates an autonomous designative proposition, with its “transparency” and “obviousness.” This syntagmatic formula, “DL,” functions as a simulated evocation of already established knowledge, that is, a meaning already given in its “obviousness,” external to both the formula and the subject(s) that enunciate it. In this manner, we make explicit one of the mechanisms of the functioning of the interdiscourse (already established, somewhere, independently) in the intradiscourse: “a preferida do mercado professional” (the preferred university in the professional market) and “Estácio é nota máxima no conceito institucional EaD do MEC” (Estácio is top-ranking in the Ministry of Education’s institutional concept of DL). Pêcheux (١٩82) called this mechanism a “pre-construct,” due to making the interdiscourse present as a memory effect – “we already know this.”

This constitutive exterior of the meanings interpretable in and through the advertisements in Figure 2 becomes interpretable in and through the dissimilation-presentification of an enunciator who is supposedly the “origin” of such knowledge. This enunciator is qualified as a spokesperson of the professional market, in the neoliberal capitalist system, i.e., “those who hire,” “the employers” – in other words, those who define the professional skills/qualifications in demand.

The functioning described above reveals another memory effect, another mechanism of presentification of the interdiscourse in the intradiscourse: the transverse-discourse, which, according to Pêcheux (1982, p. 117),

[…] crosses and connects together the discursive elements constituted by the interdiscourse as pre-constructed, which supplies, as it were the raw material in which the subject is constituted as ‘speaking subject’ with the discursive formation that subjects him. In this sense it can indeed be said that intradiscourse, as the ‘thread of the discourse’ of the subject, is strictly an effect of interdiscourse on itself, an ‘interiority’ wholly determined as such ‘from the exterior’.

This raw material that traverses the subject constitutes, as a result, what is said. In the case of the formulations that make up the advertising pieces and the manner in which they signify DL, their inscription in neoliberal capitalist discursive formation is exposed. Orlandi (2014) described such formation as being the same that “over-determines” the meanings of “formação” (education) via the meanings of “capacitação” (capacitation), “qualificação” (qualification). The author “discursivizes” the functioning of such discursive formation narrating the following scenario:

[…] there was a moment, in our history, in which one would say: “When will you ‘graduate’?” However, nowadays, the question is: “When will you ‘finish’?” [It’s] a matter of time [of superspeed], of opportunity, of employment, of a market of trained workers. A matter of “capacitation” to be an entrepreneur. Not of “education.” We don’t graduate; we finish. And what do we finish?

That equation is not easy. It involves the relationship between education, work, knowledge. And our query shifts to what “knowledge” means.

[…] let’s remember how the issue of “capacitation” has been constantly present in the media, in entrepreneurs’ and government leaders’ speeches. It’s a wildcard that one takes from one’s pocket to silence the force of social demands.

Let’s take the example of the highly disseminated “anti-poverty plan.” This plan is followed by the proposal of a card that will promote social access for millions of people, and the government guarantees that, this time, welfare is only part of the program because there will be “training courses” for those who live in conditions of extreme poverty. Such plan would avoid practices tied to populism and oligarchies run by rich rural landowners. Nor does it guarantee what the logo states: “a rich country is a country without poverty”. Despite talking about the poor, in the anti-poverty program, the president continues to talk about training and, when she talks about education, she talks about overseas courses for people with higher degree (it is thus necessary to get there). What’s left for the poorest people is training and capacitation. This issue is also present in the discourse of specialists. As one economist stated in an interview, training courses do not solve the problem, for they do not guarantee permanence, subsistence. For my part, I reaffirm what I have been saying: basic education is necessary. I mean real “formação” (education) so that those subjects can get a job, and know how to be objective in the social relationships in which they are involved. Because what is not being said is that, if we are a society of knowledge and information, these are the ways of satisfying the needs of a society of work (and of the market). (ORLANDI, 2014, p. 146-148).

For us to go further in our comprehension of the production of effects via the functioning of this discursive transversality, let us examine Figure 3. This figure features one of the latitudes of neoliberal capitalist discursive formation that determines DL advertising: its value, imputing a connection, inversely proportional, between (international) quality and (low) price, since education, when construed as merchandise, becomes priceable. So, the qualities of the product (education) are associated with a certain value/price: “qualidade internacional que cabe no seu bolso” (international quality affordable to your budget); “realize seu sonho de estudar com uma mensalidade que cabe no bolso” (make your studying dream come true by paying a monthly tuition that fits your budget), “oferta casadinha: no mês dos namorados, traga para a Estácio alguém que você ama, do crush ao amigo do peito e garanta 50% de bolsa, no curso todo, para cada um” (tied offer: during the month of Valentine’s Day, bring to Estácio someone you love, from a crush to a bosom buddy, and get 50% off tuition for each of you for the entire course).

A) Source: Google (https://cutt.ly/SiH3kpQ; https://cutt.ly/HiH8Tcq). B) Source: Google (https://www.portalr10.com/images/noticias/50984/1549374067.jpg).

Figure 3 Advertising pieces from Wyden Educacional and Estácio

The formulations stamped on the advertisements in Figure 3 do not allude to the type of knowledge that is considered the objective of education. Quite the opposite, all of the formulations orient the reader/consumer toward education as merchandise, allowing it to be reduced to a value, a price. Hence, DL on sale is advertised in sales promotions: “get 2 for the price of 1,” Estácio’s advertisement announces: “2 graduations for the price of 1.” This type of formulation is common in commercial discourse and it construes the product (“education”) as that which should be consumed in great quantity, leaving certain doubt as to its quality, which is rarely referred to in the advertisements. The consumption has to be advantageous, but not necessarily due to the quality of the product (education). What the advertisement pieces favor is the consumption of quantity, which the low price favors. Thus, one is dealing with a call to the reader/consumer – potential student – to take part in a commercial operation that solely aims at consumption, not at education (neither for a profession, nor for life).

Such discursive latitude makes it evident that DL, as a sellable product, is offered to less fortunate classes of society, since “caber no bolso” (fits one’s budget) means easily affordable due to a low price. This discursive latitude, constituted in this manner, discursivizes the ongoing class struggle in society. The class distinction also manifests in images that make up some of the publicity pieces. For example, the opacity of the Wyden Educacional advertisement shown in Figure 3 creates an association between the photo of a young black woman, dressed in the style of the business world, and the statements “realize seu sonho de estudar” (make your studying dream come true) and “com uma mensalidade que cabe no bolso” (paying a monthly tuition that fits your budget). This association makes it possible to (re)read meanings there that relate to the black people’s fight for better employment/life conditions and for equality in the conditions of existence.

If the Wyden Educacional advertisement with the photo of the black woman is collated with the other advertisements of the marketing campaign, such as the one in which the photo of a young man appears (Figure 3), one discovers indications of the production of certain silencing. That silence dissimulates the difference between the young people represented there, suggesting a relationship of supposition, as if these advertisements speak to all young people, assuming that all of them share the same socioeconomic conditions and have exactly the same needs to be satisfied by the offer of DL. It also assumes that they can all take exactly the same paths to achieve their objectives, dreams, professions, jobs, i.e., better conditions of life/existence. Hence, it also dissimulates that the resources of DL could be equally advantageous to all, regardless of who the reader/consumer is.

The discursive articulation that this latitude promotes leads to the notion meaning and circulation in society according to which DL is a good that is especially produced for certain less-fortunate social classes, which are considered its primary target-audience, producing a certain imaginary contradiction. Hence, publicity pieces encompass formulations such as “Educação a Distância: qualidade e conteúdo iguais ao curso presencial” (Distance Education: quality and content identical to the in-person course) and “o mesmo diploma do curso presencial” (the same diploma as the in-person course).

The discursive need that impels the advertising piece to affirm that DL offers the same quality and content as in-person education does materialize the difference between the two approaches that continues functioning implicitly, pointing to the existence of discourses that affirm exactly the opposite. In other words, DL could never offer the quality and content attributed to in-person education in an equivalent way.

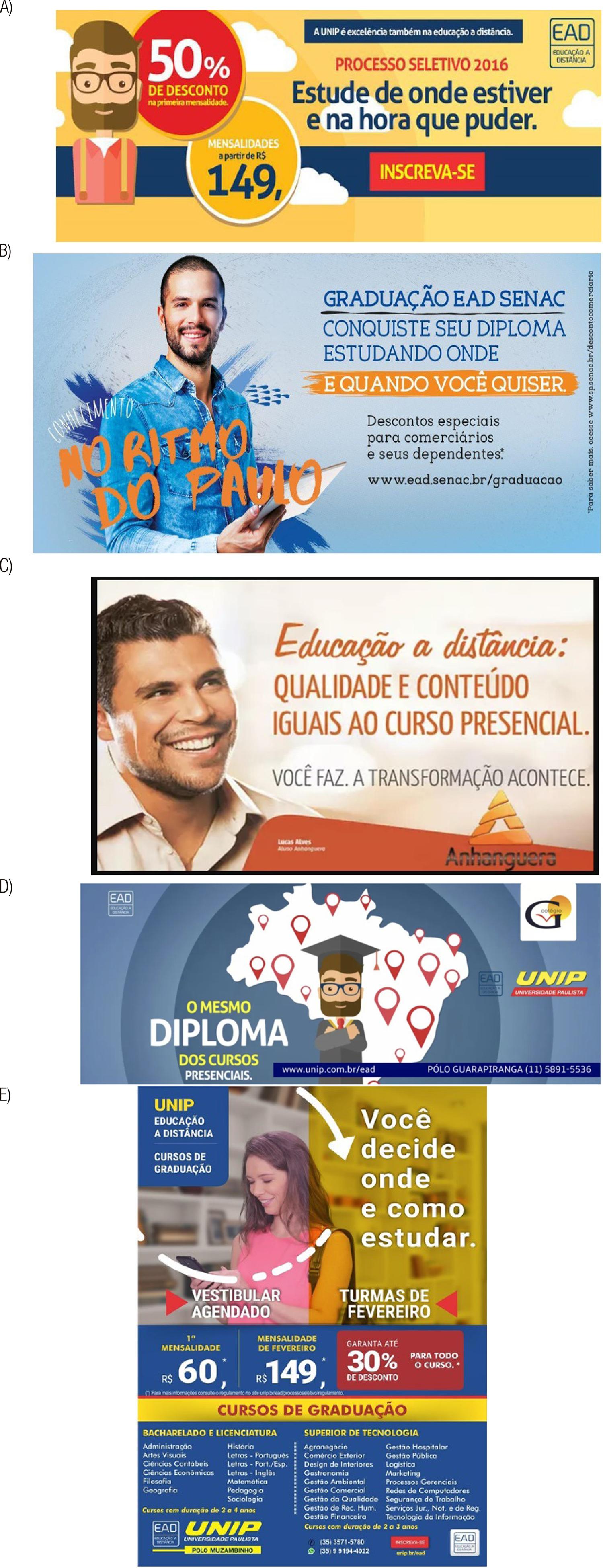

Does education (not) imply effort?

In other formulations of advertisements in Figure 4 and in the reading material archive, such as “Pós-graduação a Distância: para quem não pode perder tempo e quer dar um salto na carreira sem sair de casa” (Graduate-level Distance Learning: for those who don’t have time to waste and want to take a leap forward in their career without leaving home), “estudar a distância é assim: com flexibilidade e conforto” (distance learning: flexibility and comfort), “conquiste seu diploma estudando onde e quando você quiser/conhecimento no [seu] ritmo (de Paulo)” (earn your diploma studying wherever and whenever you want/knowledge at [your own, Paulo’s] pace), “você decide quando e como estudar” (you decide when and how to study) and “estude de onde estiver e na hora que puder” (study wherever you are and whenever you can), the evidence that DL offers flexibility, ease, convenience, optimization and celerity is reinforced. Hence, it appears to the readers/consumers that everything they want to achieve/obtain is guaranteed, without wasting time or leaving home and at the lowest price. In the conditions of (re)interpretation of the advertisements, “everything” can replace “education,” “diploma,” “employment,” “quality,” “dream,” “career,” “discount,” etc.

A) Source: Google (https://leonardoconcon.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/unip-processo-seletivo-1.jpg). B) Source: Google (https://www.pe.senac.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/EAD-1200x565-1200x565.jpg). C) Source: Google (https://cdn.abcdoabc.com.br/Cursos-EAD-Anhanguera-2015_3cbe4c9a.jpg). D) Source: Google (https://muzambinho.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/UNIPObj02.jpg). E) Source: Google (https://muzambinho.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/UNIPObj02.jpg).

Figure 4 Advertising pieces from Unip, SENAC and Anhanguera

The attributes presented as inherent to DL – flexibility, ease, convenience, optimization, celerity, among others – denounce/enunciate the fact that the primary target-audience of these advertisements encompasses those readers/consumers who “lack the conditions” to study or attend in-person teaching institutions, either for lack of time or lack of resources. Therefore, the advertisements expose the socioeconomic condition of those readers/consumers, and at the same time they reveal the divisions that aggravate the class struggle in our society. This situation leads the subjects “lacking the conditions” to choose in-person learning to be attracted to DL, which is construed, in the advertisements , as the only alternative for social ascension, especially by means of access to a (better) job.

This manner of signifying DL incorporates it into a memory network whereby it would be possible to conceive disarticulation between education and the effort it requires. In this direction, educating oneself occurs in an automatic and instantaneous mode, silencing the need to strive to graduate and/or get employed. This semantic logic produces a relationship of implication – if you are engaged in DL, you are prepared – and appears marked in formulations such as “Você faz. A transformação acontece” (You do it. The transformation occurs) and “emprego novo ano que vem? Aqui você pode” (New job next year? Here you can).

Based on such formulations, we understand that the reader/consumer would be ready for the “transformation” and for the “new job” instantaneously, automatically, which would occur without any effort. Indeed, these formulations reveal that they are sustained by the product paradigm to the detriment of the process paradigm.

The process paradigm is the basis of education, if it is taken to mean the process of constructing knowledge in which the pupil/student must/can engage as a subject, whereas the product paradigm is the basis of neoliberal capitalism, in which the person is individuated as a consumer. This overlapping of one paradigm (product) over the other (process) represents a constitutive contradiction by producing a shift from education as a process of/for the subject to education as an object that is consumable for/by the subject. Hence the possibility of (re)producing the non-need for effort as “natural evidence” (PÊCHEUX, 1982, p. 101). This contradiction influences the way in which the class struggle occurs because it interferes in the path of subjects within the social formation that circumscribes the path. It aggravates the separation between the capacitated/qualified/trained subject and the subject who is educated, between the working subject and the knowledge subject – and stabilizes the naturalization of the split between work and knowledge. These analytical consequences interact, in a significant way, with the considerations set forth by Orlandi (2014) in the aforementioned quotation.

Regarding the formulations “Você faz. A transformação acontece” (You do it. The transformation occurs) and “emprego novo ano que vem? Aqui você pode” (New job next year? Here you can), one can infer a discursive function that produces, as an effect, the anticipation of a future state already in the present moment. That is, the effects of the proclaimed instantaneous transformation are superimposed upon the present moment of the formulations any time one reads them. Projected into the position of “you,” the readers/consumers are impelled to identify with this promised future, as if it was already possible/certain, in which the doors to the (job) market are open to them, provided they take a DL course. This is how it becomes possible to offer employment the same way merchandise is offered. Following this reasoning, DL would relinquish the vocation of offering education and take on the vocation of commercializing job openings. It is not by accident that there are advertising pieces that contain formulations such as “Unip é top no mercado de trabalho/Quem afirma são os que contratam” (Unip is top-notch in the job market/That’s what those who hire say) (Figure 2).

This functioning results from the way in which the over-determination of neoliberal capitalist discursive formation is applied to DL. It controls the latitudes of the discourses about DL and produces, as an effect, the aforementioned shift in its vocation: the discourses rival with and gain control over the meanings of education and take over historicized meanings. They express DL through metaphors by eternalizing it in a different memory network, which provides an outlet for meanings related to commerce and employment.

If we also consider the photos of the young people in the advertisements in Figures 3 and 4, it is possible to (fore)see evidence of the meaning of transformation – that DL can benefit those who consume it – producing identification with those who make up the primary target-audience of the advertisements. Hence the reader/consumer is expressed metaphorically (mirrored) by taking the position of the young people portrayed there. Through such a mechanism, the readers/consumers would recognize – in this metaphorical game (a game of mirrors, a game of superimposed images) – that which is suggested as their own future, i.e., young people who already have a job because they already are DL students, or they will have a job as soon as they become DL students.

The (re)interpretation of the DL advertisements rescues visibility, at the level of relationships of strength, to the dominance of the other pole of the class struggle. That is the pole of those who hire, the employers, the detainers of economic strength, who, for this reason, are presented as if they were the definers of the offer and of the new vocation of DL. The suggestion is that DL would be an unquestionable demand of the job market. Therefore, the ideological efficacy of the implicative functioning “você faz, a transformação acontece”, (you do it, the transformation occurs)”, a paraphrase of “aluno da EaD, aluno empregado” (DL student, employed student).

The strength of this relationship of implication, in turn, transforms the pre-construct that education is a process of educating the subject as a subject of knowledge into the pre-construct that education is an acquirable/consumable product. It articulates another semantic reference for education: education as merchandise; education achieved effortlessly; education as capacitation/qualification/training for employment; education without preparation (for life); education without a subject and without history.

Does education (not) imply time?

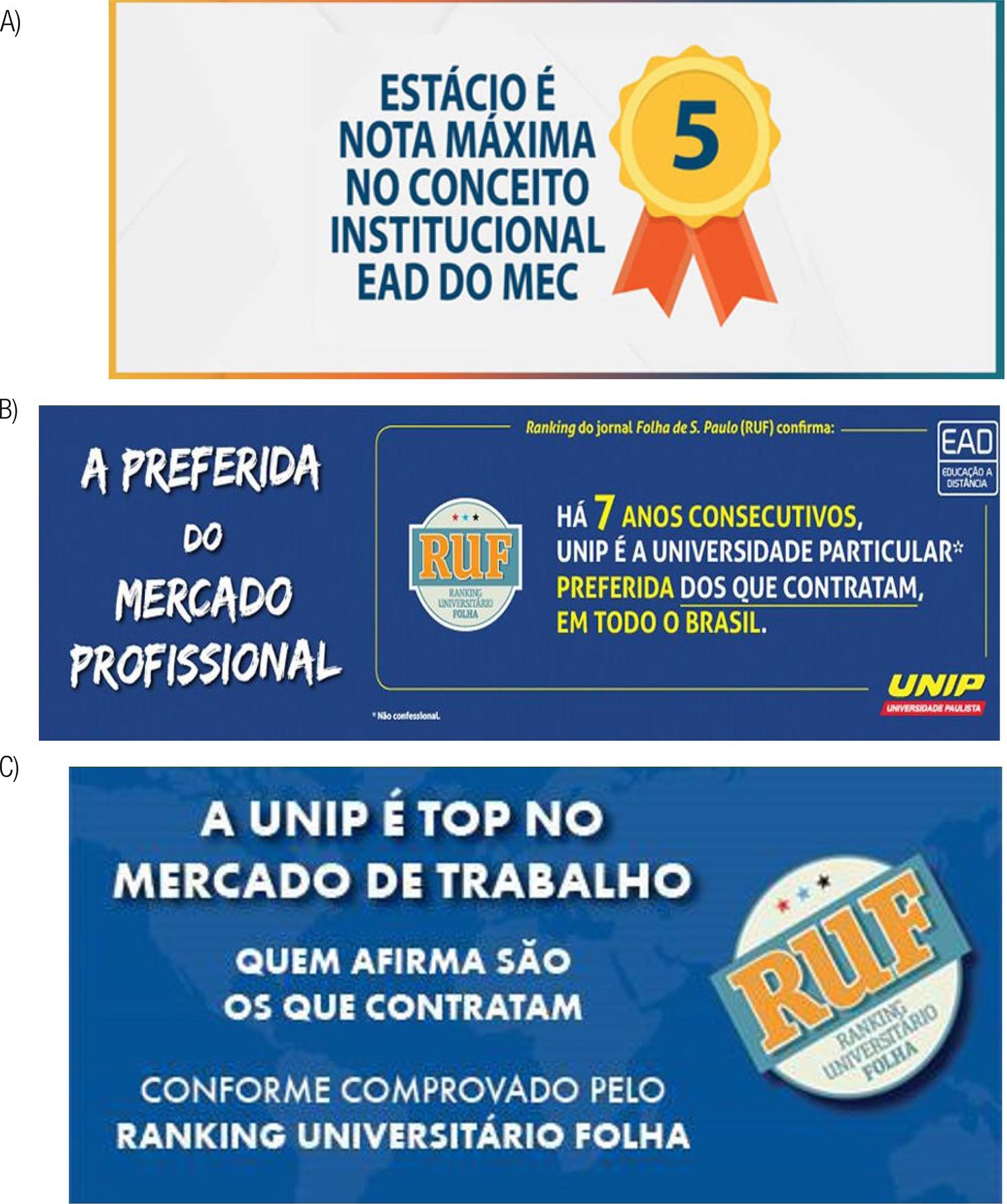

Another discursive latitude that operates in advertisements from the reading material archive and that involves (re)directing the meanings of DL, (re)occurring neoliberal capitalist discursive formation, can be inferred on an analysis of Figure 5. Therein a relationship of implication between time and education is injected into discourse: if there is a new live format, then there is a new form of qualification; if lessons feature interaction in real time, then it is live (executive) education. Interpreting this relationship of implication exposes the encapsulation, or envelopment (RODRIGUES, 2012), of education by evidence, that is, by the naturalized meaningful coherence of the rendering of “in real time,” configuring itself into an apparently crystalized image that traverses, in the form of a transverse discourse, the neoliberal capitalist discursive formation. In this discursive formation, “in real time,” as a transverse discourse, possible concatenations are articulated that become available to the processes of signification and, as such, are (re)enacted in discursive montages such as those in Figure 5.

Therefore, the meaning of “in real time” furnishes the necessary condition for the imaginary construction of DL as something that is consumed, supposedly in an interactive manner, in a short, predefined time. Other evidences are articulated over this evidence of meaning. They are furnished by the discursive formation of the NICTs, which sustains the technological tendencies that over-determine the ways of producing DL, making a type of education appear concrete and viable, which would purportedly be conducted in a privileged manner, in a new format and a new time, that of live streams.

Thus, the educational process is encapsulated/enveloped in the short-duration (superspeed) paradigm, for it would have to occur subject to the restrictions of this supposed new format, which is typical both of performances (of diverse formats and for diverse purposes) in the entertainment world and of dissemination in the digital realm. This also leads to the supposition that beyond this short time of duration there would be no need for students (to make an effort) to educate themselves. In other words, there would be no need to dedicate time in addition to that of the live streams, which produces an effect of immediacy and simplicity for DL, thus reinforcing a semantic breaking-away from the meaning of “formation” (formação) as an implication of education.

It is within this semantic framework of the advertisements in Figure 5 that a corporate façade is attributed to DL, presenting a sub-product of this merchandise: executive (distance) education, whose imaginary commitment would be to offer “new qualification in real time” capable of placing, at the market’s discretion, entrepreneurs/professionals ready to satisfy market demands. The meaning of education in these advertisements thus shifts towards “qualification” (qualificação).

What is not said in the advertisements is that “qualification” (qualificação) and “formation” (formação) do not mean the same thing, because, in terms of education, they do not function synonymously. As we saw earlier, “qualification” results from the product paradigm, metaphorizing “capacitation” and “training,” whereas “education” results from the process paradigm, metaphorizing the conditions for constituting forms of individualization that could restore to the subject a relationship of identification with knowledge, opening up this relationship to other articulations that would escape the evidence of the subject’s status as a “consumer.”

The model of executive (distance) education, which promises “a new form of qualification” by way of courses of short duration, makes room for the question “when will you graduate?” to become meaningless and be replaced by the question “when will you finish?” – as was pointed out by Orlandi (2014). This question evidences the shift from the meaning of education determined in and by the relationship with the subject to the meaning of education determined in and by the relationship with time. This shift marks, for the subject, another form of identification with education, in which a slippery, short-lived, empty and excessively technical connection is (re)produced. Furthermore, this shift and its effects are intensified by the evidence of “in real time” as an interface of the evidence of the superspeed imposed as a paradigm of the current society organized by the metaphor of the network (DIAS, 2009) and of the digital world (DIAS, 2018).

The new normal of/in education

The advertising pieces that make up the reading material archive, from which the DL theme gained theoretical-analytical delineation in this article, set in motion effects of meaning that are not exclusive to the pieces. These effects are possible there because they are in circulation in society in a relationship of dominance, especially – we can say based on Dias (2009) – via the transposition from a society founded upon the circular paradigm of the (borderline, mappable) production of knowledge to a society founded upon the reticular paradigm of the (fluidic, continuous, indefinable) production of knowledge. In our opinion, this becomes possible by means of the decisive affiliation with the discursive formations of the NICTs and of the semantic world organized under the effect of evidence of the digital world, under the dominance of the neoliberal capitalist discursive formation.

This is the manner the advertisements that offer DL as a product/merchandise have their meaning administered, based on the way in which these discursive formations overlap, involve and over-determine each other. They make themselves present through the way in which the ideological construction – of school spaces, public policies, official documents that direct/regulate educational practices, processes for educating teachers, textbooks and the subjects that see themselves identified in them – gains sustainment. We emphasize that the constructed evidence of education as a product/good functions both for its commercialization in showcases and for its negotiation on stock exchanges as a commodity,12 reinforcing the ideological efficacy that reduces education to capacitation, training, qualification, professionalization, employment and, ultimately, a product only destined to satisfy the demands of the world of work.

In fact, we can say that such ideological efficacy is a practice that functions in the territory established by the power game disputed in and by the class struggle, whose result is “the reduction of teaching (of education, of DL) to a source of profit” (AVELAR, 2020). Consequently, education is inscribed into the world of highly lucrative businesses – and with DL, it is not different; quite the contrary, it is aggravated.

As a business that must necessarily be lucrative, education becomes an object of interest to companies, investors and magnates, as was reaffirmed by Marina Avelar, a researcher at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, in Switzerland, in an interview given to Cátia Guimarães. In the interview, when commenting on the actions of financial institutions – business entities of education – in relation to the establishing the relationship between public and private interests in and about education, the researcher alerted to the fact that

[…] those who dictate the [educational] content are no longer the entities of educators, associations and forums, but rather the educators that we used to call external, yet they are no longer external. There are many project disputes. Teachers generally want a creative, focused project that responds to the needs of each student and that will produce emancipation and critical thought. And the project that these foundations introduce generally is not that; it is a more pragmatic thing, of economic development, of developing abilities the market needs. […] These foundations generally have a vision of education aimed at practical abilities and jobs, of the job market, concentrating on economic development, contemplating a type of person that will later be useful to the job market. (AVELAR, 2020).

The advertisement analyses carried out in the present study also demonstrate what the above researcher denounces, also showing how the interests of corporate groups construe DL as a product/business via semantic relationships of implication, such as “você faz, a transformação acontece” (You do it. The transformation happens) or “se aluno EaD, então aluno empregado, aluno com futuro garantido” (If DL student, then employed student, a student with a guaranteed future).

When we were finishing writing this article, the emails appearing in our inboxes just wouldn’t stop coming in, offering the most diverse DL products. Among them, one that really stood out was offering “digital graduation” via DL, as shown in Figure 6.

In the advertisement in Figure 6, the meaning of “graduation” shifts based on its predication as “digital.” To this extent, it would be the “new” predicate, that is, the “new” product being offered, which, in this case, would not just be graduation, but also the digital format. By means of advertisements like this one, the market, whose known practice is that of the apparent diversification of its products, seeks to stabilize for the reader this evidence as a novelty that is necessary to consumption. Thus, the market promotes its products to the neeed/condition of what has become known as the “new normal.”

It is also worth emphasizing that, due to the pandemic scenario experienced throughout 2020 and 2021, associated with SARS-Cov-2 contamination, the recommendation was that physical contact and in-person meetings should be severely restricted. That restriction established the conditions for the production of the “new normal” as an evident fact and, consequently, DL as the “new normal” in/of the field of education. The discourse that sustains the “new normal” in/of education is crossed by the transverse discourse that (re)produces the digital paradigm as the memory of inscription of an already given, unavoidable (new) reality, presented to the reader/consumer as being global and universal, and capable of being equally accessed and experienced by all. These effects dissimulate the differences that constitute the social reality and the class struggle. Therefore, in this paradigm of the “new normal,” the market’s offers do not take into consideration the varying degrees of disparities that result from the existence and interaction of different generations and social classes marked by diverse conditions related to the digital world.

From our perspective, based on what our analyses enabled us to understand about the game of meanings operating in DL advertising, in the class struggle the paradigm of the process of education must not be relinquished. Education must not be reduced to mere capacitation (or training, qualification, professionalization), especially in DL, since, in this mode, there is a much higher likelihood of identifying an increasing number of subjects with (certain) meanings of education.

Reducing education to mere training can produce, as a consequence, a historic fissure in the production of conditions that sustain the process of emancipation of the subject in and through education; and thus, in the production of conditions that enable subjects to render meanings and signify themselves not only for work, but also for life in society. This remark leads us to warn the reader of the imperious need for us to seek ways of restoring to subjects their central role in both the in-person and distance processes aimed at their education, so that the paradigm of production does not irreversibly destroy the paradigm of education.

REFERENCES

AGUSTINI, Cármen L. H.; ARAÚJO, Érica Daniela de. A figura do feminino em filmes infantis: pregnância e circulação de sentidos. Horizonte Científico, Uberlândia, v. 3, n. 1, p. 1-27, 2009. Disponível em: http://www.seer.ufu.br/index.php/horizontecientifico/article/view/4259. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

ALTBACH, Philip G. Knowledge and education as international commodities: the collapse of the common good. International Higher Education, Washington, DC, n. 28, p. 55-60, 2002. Disponível em: https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/6657/5878. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

AVELAR, Marina. A caixa preta das startups da educação. [Entrevista cedida a] Cátia Guimarães. Outras Mídias, São Paulo, 10 jul. 2020. Disponível em: https://outraspalavras.net/outrasmidias/a-caixa-preta-das-startups-da-educacao/. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Cristina Helena Almeida de. A mercantilização da educação superior brasileira e as estratégias de mercado das instituições lucrativas. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 18, n. 54, p. 761-801, 2013. Disponível em https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v18n54/13.pdf. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

DIAS, Cristiane. Análise do discurso digital: sujeito, espaço, memória e arquivo. Campinas: Pontes, 2018. [ Links ]

DIAS, Cristiane. Imagens e metáforas do mundo. Rua, Campinas, v. 15, n. 2, p. 15-28, 2009. Disponível em: https://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/rua/article/view/8638853/6459. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

LAVAL, Christian. A escola não é uma empresa: o neoliberalismo em ataque ao ensino público. 2. ed. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2019. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Romualdo Pereira de. A transformação da educação em mercadoria no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 30, n. 108, p. 739-760, 2009. Disponível em: <https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v30n108/a0630108.pdf>. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

ORLANDI, Eni Puccinelli. Formação ou capacitação? Duas formas de ligar sociedade e conhecimento. In: FERREIRA, Eliana Lucia; ORLANDI, Eni Puccinelli (org.). Discursos sobre a inclusão. Niterói: Intertexto, 2014. p. 141-186. [ Links ]

PÊCHEUX, Michel. Papel da memória. In: ACHARD, Pierre et al. (org.). Papel da memória. Campinas: Pontes, 1999. p. 49-57. [ Links ]

PÊCHEUX, Michel. Semântica e discurso: uma crítica à afirmação do óbvio. Campinas: Unicamp, 1995. [ Links ]

PÊCHEUX, Michel; GADET, Françoise. A língua inatingível. In: ORLANDI, Eni Puccinelli. Análise do discurso: Michel Pêcheux. Campinas: Pontes, 2011. p. 93-106. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Eduardo Alves. “A costura do invisível”: sentido e sujeito na moda. In: CARROZZA, Guilherme; SANTOS, Mirian dos; SILVA, Telma Domingues da (org.). Sujeito, sociedade, sentidos. Campinas: RG, 2012. p. 117-134. [ Links ]

SGUISSARDI, Valdemar. Modelo de expansão da educação superior no Brasil: predomínio privado/mercantil e desafios para a regulação e a formação universitária. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 29, n. 105, p. 991-1022, 2008. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v29n105/v29n105a04.pdf. Acesso em: 2 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA JÚNIOR, João dos Reis; SGUISSARDI, Valdemar. A educação superior privada no Brasil: novos traços de identidade. In: SGUISSARDI, Valdemar (org.). Educação superior: velhos e novos desafios. São Paulo: Xamã, 2000. p. 155-177. [ Links ]

3- The term “intradiscourse” refers to how what is said is presented in and through the superficiality of the language, whereas interdiscourse refers to how the signification, i.e., the production of the effects of meaning, becomes materially present in what is said.

4- Avaiable at: https://www.lins.sp.gov.br/fotos/60c8e1346b1de9ad9f20c086d86cf775.jpg. Accessed in: July 2020.

5- Avaiable at: http://folhadeipero.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Univesp.jpeg. Accessed in: July 2020.

6- Avaiable at: https://www.clickaracoiaba.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/vertibular_univesp_2semestre_2018-690x336.jpg. Accessed in: July 2020.

7- The advertising pieces reproduced (in an adapted manner and for the purpose of analysis) in this article circulated between 2018 and 2020. They were accessed in July 2020 and screen-captured. The screenshots came from URLs provided by Google Images. The advertisements in Figure 1 are available, respectively, at the following URLs: https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcT79epRmmuvm7U-pXxsT3xGNZtN1F_7G1Uykw&usqp=CAU; and https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcRz32_nc4ab5Et6CqHHUrqSgaxeifE9Vvp3Og&usqp=CAU.

8- Transverse and pre-constructed discourses are, according to Pêcheux (1982), mechanisms of the functioning of the interdiscourse in the intradiscourse, making it present as an effect of (discursive) memory.

9- We understand discursive prägnanz as a material vestige of the neoliberal capitalist discourse (AGUSTINI; ARAÚJO, 2009) that maintains the functioning of this effect of logical inference present in the different statements about education and professionalization.

10- Carvalho (2013) rescues readability to this process of transforming education into merchandise. The author presented the legal apparatus – established in Brazil via articulation between the Federal Constitution of 1988, the Law of Guidelines and Bases for National Education (1966) and Decree No. 2,306/1997 (which replaced Decree No. 2,027/1997). Those legal devices produced the conditions necessary for the dissimulation of a process of commercializing higher education, which was already diagnosed, according to the author, by Silva Júnior and Sguissardi (2000), reaffirmed by Sguissardi (2008) and Oliveira (2009). It is in this process that one observes “the transformation of education into merchandise, whose price is determined by the market with the central aim of obtaining profit for the benefit of the owners and shareholders [...]” (CARVALHO, 2013, p, p. 763). The author also warned: “The tendency toward the commercialization of higher education is not limited to the case of Brazil. The transformation of the educational sector into an object of interest to big capital is one of the consequences of globalization, especially in the Asiatic countries and in the developed countries of Anglo-Saxon origin, above all the United States” (p. 764).

11- Such meaning circulates via other routes in addition to the advertising pieces, branching out into and impregnating other potential formulations in which the meaning of education is at stake.

12 - Altbach (2002) had already warned about a “revolution” that was taking place in education and transforming it into an internationally negotiable commodity. As a commodity, according to the author, education can both be acquired by a consumer with the objective of constructing a range of skills and capacities of interest to the market, and can also be marketed by academic institutions that begin to function and act as multinational corporations. Following this path, education at all its levels would go beyond the status of a commodity and begin to function as a system that provides skills and capacities necessary to sustain financial success and thus establish the foundations for forming civil society and national participation.

Received: September 19, 2020; Accepted: February 10, 2021

texto em

texto em