Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 27-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248240660por

ARTICLES

Literacy is more than teaching a code: discourse and authorship in language teaching*

1- Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. Contact: lucienecerdas@gmail.com

This article aims to discuss the use of the phonic method in literacy, preconized, in the midst of a “methods quarrel,” as the only evidence-based way to teach literacy. Although this discussion is not recent, from 2019 on, it gains strength by integrating the National Literacy Policy (PNA) [Portuguese acronym of the name], in a very controversial moment regarding the directions of education in the country. In this context, the discussion proposed here is based on the dialogue with authors such as Cecília Goulart, Magda Soares, João Wanderley Geraldi, among others who have dedicated their studies to literacy and contributed to the expansion of the debate on teaching of the mother tongue. Supported by these authors and by the Bakhtinian perspective on language, this article also presents pedagogical practices performed by undergraduate students of the Pedagogy course at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in the scope of the extension project “The school-university partnership in children’s literacy and the initial training of literacy teachers”, through which they are inserted into the daily life of public schools and participate in the planning and development of didactic projects focused on children’s literacy. From the proposed discussions in this article and the performance of the undergraduates, one can glimpse practices based on the discursiveness of human relations, which are shown to be potent for the valorization of children’s voices, their authorship as readers and writers, and their protagonism in the literacy process, seeking to expand their repertoire of cultural practices of reading and writing and their formation as socio-historical and cultural subjects in the struggle for social inclusion.

Key words: Literacy; Discursive perspective; Teaching mother tongue; Literacy practices

Este artigo tem como objetivo discutir o uso do método fônico na alfabetização, preconizado, em meio a uma “querela dos métodos”, como o único caminho baseado em evidências científicas para alfabetizar. Apesar dessa discussão não ser recente, a partir de 2019, ela ganha força ao integrar a Política Nacional de Alfabetização (PNA), em um momento bastante controverso quanto aos rumos da educação no país. Nesse contexto, a discussão proposta aqui se dá a partir do diálogo com autores como Cecília Goulart, Magda Soares, João Wanderley Geraldi, entre outros que têm se dedicado ao estudo da alfabetização e contribuído na ampliação do debate sobre o ensino da língua materna. Ancorado nesses autores e nos conhecimentos da perspectiva bakhtiniana sobre linguagem, este artigo apresenta práticas pedagógicas realizadas por licenciandos do curso de pedagogia da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) no âmbito do projeto de extensão “A parceria escola e universidade na alfabetização das crianças e na formação inicial de alfabetizadores”, por meio do qual eles se inserem no cotidiano das escolas públicas e participam do planejamento e desenvolvimento de projetos didáticos voltados à alfabetização das crianças. A partir das discussões propostas neste artigo e da atuação dos licenciandos, vislumbram-se práticas fundamentadas na discursividade própria das relações humanas, que se mostram potentes pela valorização da voz das crianças, de sua autoria como leitoras e escritoras e de seu protagonismo no processo de alfabetização, visando à ampliação do seu repertório de práticas culturais de leitura e escrita e sua formação como sujeitos sócio-históricos e culturais na luta pela inclusão social.

Palavras-Chave: Alfabetização; Perspectiva discursiva; Ensino de língua materna; Práticas de alfabetização

Introduction2

While starting to write this text, I immediately went back to the time of my teacher training and professional initiation, in the 1990s, when discussions about literacy methodologies and criticism of synthetic methods (phonic, syllabic, etc.) were effervescent, and new paths and proposals for teaching reading and writing were beginning to emerge. At that time, the search for innovative ways to address literacy from new perspectives in the teaching of reading and writing was very strong. The study by Soares (2000) on the State of Knowledge on literacy, for example, gives an account of the multiplicity of academic-scientific perspectives that, since 1980, have shed light on linguistic, cognitive, historical, social, and pedagogical aspects involved in theoretical and methodological discussions about literacy as a process that is much more complex than a coding and decoding technique.

Although the discussion about methods is part of the very history of literacy, the belief that there is only one possible method to teach literacy seemed outdated, but it was revived in the first years of the 21st century and gained strength from educational policies recently adopted in a very controversial moment regarding the directions of education in the country. We highlight the institution of a National Literacy Policy (PNA), by Decree No. 9,765, April 11, 2019, whose orientation is for the adoption of synthetic marching methods, with emphasis on phonic, pointed out in the document as the only one based on scientific evidence, coming from the “findings of cognitive sciences,” which cover the studies of the mind and its relationship with the brain, “such as cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience” (BRASIL, 2019, p. 20).

This discourse of scientificity, adopted in official documents about the phonic method in teaching reading and writing, supports the warning made by Soares (2004, 2019) of a dangerous trend of return to previous paradigms, “with loss of the advances and achievements” already made on literacy over many decades; with damage to the premise of teacher autonomy in their methodological choices; disregarding that learning the written language involves not only cognitive aspects, but the learning of a cultural object in its various facets (linguistic, historical, social, affective); and encouraging the use of a (phonic) method in which literacy begins at the end of the process, that is, by learning phoneme-letter relations. It is a step backwards because, by privileging a single area as scientific, the PNA disregards a whole academic production that points out other elements of literacy, such as the heterogeneity of children in their learning processes. I also highlight that this perspective contributes to a mistaken and fallacious interpretation that children’s literacy has been conducted in an improvised and amateurish way – which is not true – which would justify a greater control over the teaching work.

Contrary to what the PNA would have us believe, discussions about literacy are marked by different voices, coming from the contributions of several areas of knowledge (SOARES; MACIEL, 2000), and by the practices that are built on a daily basis by the teachers who mediate the literacy process in this country, whose social inequalities impose themselves as a great challenge to the insertion of thousands of children in the world of written culture. These practices, forged in everyday school life, are becoming the teachers’ repertoire of knowledge, which does not give in to innovations without resistance to the learning needs of their students, despite the forms of supervision and surveillance over their work.

In this sense, Morais (2012) points out that research on what teachers do has shown that when they were forced to adopt the phonic method, they recreated their activities according to what they considered appropriate for their students, selecting new proposals to motivate and using their class time in a more productive and motivating way as forms of insubordination to interference in their work.

Silva (2014) corroborates, in his research, the finding of Morais (2012) that teachers, even though they have to follow a program to use the phonic method:

[...] (re)invented, in their daily lives, other ways of doing things, such as saying the name of the letters instead of pronouncing the phonemes and adding other proposals and materials, some of them closer to the syllabic method and others related to the literacy perspective. [...] they built their reading and writing teaching practices based not only on the program’s guidelines and materials, but also on other materials and other experiences they had undergone and that constituted their knowledge and practices. (SILVA, 2014, p. 121-122).

Likewise, Cerdas (2007, 2012), when reviewing research on literacy, brings relevant data about the variety of the repertoire of good practices developed and experienced in Brazilian classrooms in the most diverse contexts and conditions, but which are invisible. The materials produced for teacher training over the last few years, which bring accounts of teaching experiences, are also a source of significant and innovative practices, quite different from the mechanical and repetitive exercises of the synthetic methods, which emphasize training and memorization.

In the history of literacy methods3, the advocates of those named synthetics conceive language as a code and writing as a system of graphic representation of sounds, as is pointed out in the PNA booklet (BRASIL, 2019). Literacy is constituted, in this perspective, as “the teaching of reading and writing skills in an alphabetic system” (BRASIL, 2019, p. 18). The primary goal of these methods is to learn the rules of decoding and codification of the language, through knowledge of the alphabetic code and graphic phonemic correspondences. Therefore, “they treat the child as a being who conceives the internal units of words just as already literate individuals do [...]” (MORAIS, 2012, p. 30).

[...] start from the assumption that children, naturally and without difficulty, would already think, from an early age, that letters ‘replace sounds of the words we pronounce’ [...] this is what would justify the solution of simply transmitting to them, in a ready-made manner, the information about sound-graphic correspondences. (MORAIS, 2012, p. 31).

Learning this mode of graphic representation - writing - using synthetic methods begins with the study of the smaller linguistic units (sound, letter, syllable) to finally reach the more complex structures, especially the text. In practice, the idea of these methods is to introduce children to the sounds and letters step by step, in an order of increasing difficulty. From the moment they learn the alphabetic code, the proposed activities and exercises emphasize spelling and grammar, leaving the content of writing and its function in the background (COLELLO, 2014).

The phonic method therefore reflects an “[...] instrumental conception of language, which takes language and its operating system as objects of literacy, depersonalizing the subjects who enunciate it, who think about language and signify the world” (CORAIS, 2019, p. 163). Furthermore, with homogenization as an assumption, these methods ignore and disregard subjectivities, and literacy failure is seen as the fault of the subject alone, once the method has been applied to its satisfaction.

The adoption of the phonic method does not constitute innovation, but a step backwards for literacy, as it “considers that the ability to segment words into phoneme sequences is something not very complex [...] and that, without pronouncing such phonemes in isolation, children do not become literate or would not become literate in the ‘best way’” (MORAIS, 2012, p. 31).

Not to mention the texts present in these teaching materials, which constitute pseudotexts for learning to read and write, such as the example (Figure 1) of primer three of the Alfa e Beto Program book (BARBOSA, 2013, p. 26):

Figure 1 Text from Alfa and Beto program materialSource: (BARBOSA, 2013, p. 26).The tamarin eats pounds of muck in bed.Monkey goes to school with bag.Faquir eats okra with knife and gets weak.We present a literal translation of the phrases present in the material, even though the combination of syllables does not correspond to the objective that is being sought in Portuguese.

Believing that the phonic method is the solution for literacy in our country is to disregard the entire history of literacy and the theoretical and scientific advances in the area, not to mention the socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of Brazilian society. Cagliari’s quote, for example, makes explicit the misconception of synthetic method advocates that there is easier or harder knowledge in terms of letters/syllables/sounds.

For a child who is about to learn to write, anything is difficult, and the motivation for preferring one word to another or the writing of one letter to another is not justified in linguistic terms, but based on the child’s criteria and interests. Certainly, there are easier and more difficult words from the point of view of methods. If one adopts a syllabic method, words with the CV structure (consonant + vowel) are simpler than words with CCVVCC type syllables (e.g. trains). If the child starts from the alphabet instead, short words (e.g. trains) are easier than long words (e.g. mathematics) - even if these long words only have CV-type syllables. (It is not the case for the author’s example translated into English.) The difficulty lies in the methods and not in the action of the learner. So I don’t see how one can say that writing a word like fish constitutes a more complex, more difficult activity than writing paw or house, for someone who is learning to write. (The words chosen as examples by the author, in relation to the difficulty or ease in being written, do not present a direct correspondence with the English translations.). (CAGLIARI, 2007, p. 71-72, italics ours).

These methods are also characterized by the fragmentation of the reading material; concern that the reader be able to emit sounds corresponding to a group of letters; mechanical reading, which impairs the understanding of the meaning of the texts; reading letter by letter, or syllable by syllable, which hinders access to the meaning of the text; and disregard for the subject of learning. The situation often is that “The student speaks Portuguese, but does not recognize his language in the classroom, nor in the exercises proposed by the teacher, nor is he able to transpose the supposed learnings to his social practices” (COLELLO, 2014, p. 172).

One separates the moment of learning to read and write from the moment of reading and writing, in opposition to the theoretical-methodological discussions held since the last decades of the 20th century. Methods that go against a perspective in which literacy is not characterized as teaching a code, but as “initial teaching-learning of reading and writing” (MORTATTI, 2019, p. 49) and that, having as an object of knowledge the language itself and its discursive manifestations, are based on social practices of reading and writing practices.

I understand, as do the authors with whom I dialogue, that knowing the relations between sounds and letters is not enough to understand writing in all its complexity, as we will see throughout this text. And as cultural knowledge, learning the language system cannot take place outside the context of discursive interactions (CORAIS, 2019), disregarding the learning subject.

The child, in this perspective, never arrives at school empty of knowledge about writing, however restricted his/her family and community environment may be in terms of quantity and quality of the reading and writing repertoire to which he/she is submitted and with which he/she interacts. This should be a fundamental premise of literacy in contemporary times, and even those who do not master alphabetic writing engage in reading and writing practices through the mediation of others and develop knowledge about texts and discursive genres that circulate socially. However, as these sociocultural experiences are unique, not all children arrive at school with the same level of knowledge about writing, which has important implications for the development of teaching practices, since the classroom is configured as a space of diversity and difference, which need to be respected as potentialities.

One cannot ignore at this point the context of the covid-19 pandemic, which, since the beginning of 2020, has taken children and teachers out of face-to-face contact in schools because of the need for social distance. A situation that, with no date to end, is likely to further deepen the gap between the richest and poorest children in society in terms of their living conditions, with consequences for their literacy, dropout rates, and school failure in the post-pandemic period.

It is important in this discussion to think about why, what for, and what we want as an education for disadvantaged children. The answers to these questions imply in options in the implementation of literacy policies and training of literacy teachers. More than the adoption of a method, the scientific discourse present in the PNA is linked to a government policy that intends to control the teacher’s work, not only in basic education but also in higher education, to a perspective of society in which differences are not tolerated and dissenting voices must be silenced, so that critical subject formation and Paulo Freire’s premise of education as a practice of freedom are rejected.

Therefore, the argument that many of us were literate with these synthetic methods does not hold up. A large part of those who have attended school for several years have not developed the taste and habit of reading. Students, even at university, show difficulties in writing, expressing their ideas and thoughts, and being authors of their writing. The evaluations that measure the population’s proficiency in reading and writing reveal unsatisfactory levels that prove this reality4. How many of us have actually become autonomous and authorial readers and writers in our use of written language?

There is a legitimate concern with the autonomy of subjects before the social practices of writing, in view of their belonging to literate societies, “[...] organized around a writing system [...] a culture whose values, attitudes and beliefs are transmitted through the written language and which values reading and writing more effectively than speaking and listening [...]” (MORTATTI, 2004, p. 98).Our daily life is full of writing, and its demands expand the perspectives for a literacy that allows “[...] a prolonged schooling and the social autonomy of adults in the political and economic space of developed societies” (CHARTIER, 1998, p. 12), which goes far beyond writing a simple note or a shopping list.

It is important to reaffirm the social function of school in the expansion of the cultural and literary repertoire of children, especially those whose access to reading and writing is restricted. It is to make it “[...] space-time for the expansion of the reading of the world by deepening both the linguistic knowledge and the ways of saying and reading the world [...]” (GOULART, 2019, p. 15).

Literacy is characterized as a political issue of social marginalization of those who do not master writing, not as a code to be deciphered, but as a language that is the basis of social interactions. As Geraldi (2011, p. 29) emphasizes, “Reducing literacy to the learning of a technique [...] is to divest the literacy process of any political character. As if technique were neutral and as if its use – the meanings it circulates – were independent of social interests. This is a fundamental issue of the idea of a literacy practice devoid of the ethical sense of teaching in promoting a more critical reading of reality (FREIRE, 1991). No one better than Paulo Freire (1991) described the political role of learning to read and write by pointing out that the reading of the world, which precedes the reading of the word, changes as the subject learns to read the written word.

Although the search for new didactic alternatives for literacy is not recent and coincides with my training as a teacher, the challenges of literacy and functional illiteracy – young people and adults who have attended school but show very low levels of proficiency in reading and writing – persist and show the lack of a state policy that really prioritizes education, a lack that can be seen in the discontinuity of policies and proposals for literacy and teacher training. Although the article does not aim to address these aspects in depth, it is worth noting that the discontinuation of the National Pact for Literacy at the Right Age (PNAIC) [Portuguese acronym of the name] is one of the most recent examples of discontinuity that has opened a vacuum for the adoption of a phonic perspective for literacy from the PNA.

The voice and the protagonism of children in literacy

For the discursive perspective, based on Bakhtinian principles, language constitutes us and is constituted by us in the dynamics of relations between subjects. And it is through the set of these relations, mediated by signs (gestural, oral, written, etc.), that the subjects apprehend the different social voices, also constituting their subjectivity, in a constant becoming, in a unique and singular way. The purpose of language is, therefore, in the “[...] meanings that mobilize man, from his most basic needs to his need to break with the established, including language” (GERALDI, 2011, p. 30). The subject uses language, as material reality, for his concrete needs, the linguistic form being much less important and its suitability to the concrete context of the enunciation situation being much more important.

Language has the property of being dialogical, and the utterance is a whole of meaning materialized in oral and written texts. These statements are constituted by the word in dialogue with other words, in such a way that every speech is crossed by the speech of others. In the words of Fiorin (2016, p. 36), the Bakhtinian perspective conceives that “An utterance is constituted in relation to statements that precede or succeed it in the chain of communication [...] a statement requests a response, a response that does not yet exist.” And “[...] the study of the enunciation as the real unit of discursive communication will make it possible to understand more correctly also the nature of the units of language (as a system) – the words and sentences” (BAKHTIN, 2019, p. 22). This implies considering that the system of normative forms is the product of a reflection on language, a produced abstraction that does not serve the immediate purposes of communication (BAKHTIN, 2014).

The teaching object is the entire written language, not the language system per se (CORAIS, 2019). Thinking about literacy from this understanding is to glimpse paths quite different from those proposed by synthetic methods, especially phonic methods, which conceive writing as a code and disregard the dialogical relations that constitute it.

As the learning of the mother tongue, in all its complexity, its teaching should be based on the enunciations in which it manifests itself in the diversified universe of discursive genres and their contexts of production. Resuming Colello’s (2014, p. 172) concepts, I understand that the consequences of this discursive conception in relation to the teaching of the mother tongue are many and central to the criticism of the phonic methods, because this conception allows us to break “[...] with the passive posture of the subject-learner, not only in relation to the language itself, but, as a consequence, also in relation to the activities proposed in class or to the use of the didactic material”, moreover, as “agents of linguistic production”, the relationships between teachers and students are also modified.

Based on the Bakhtinian principle, the subject in his interactions with writing seeks meanings in reading, establishes dialogues with the text, with the other’s word. At the same time, he expresses himself through the word in a unique way. In this discursive dimension of language, “The search for the word itself, is, in fact, a search for the word precisely not my own, but for a word greater than myself” (BAKHTIN, 2011, p. 385). It is expected, that in the activities proposed in the classroom “[...] the enunciations of children in the concrete process of interaction are taken [...] that the different genres of discourse and the situations in which they are produced and that they evoke are worked”, being the study of the forms of language guided by the process of production of senses (GOULART, 2019, p. 16).

Literacy practices in the classroom, whatever they may be, are constituted in the space-time of discursive interactions between different subjects that mutually teach and learn. However, the quality of these relationships can vary depending on how knowledge is mediated by the teacher and how much the children’s speech in the classroom allows itself to be heard. The methodological option we make here is the one of the teacher’s authorship in planning and developing literacy practices that value the production of discourses in the classroom, in which children have a voice as subjects of the process of teaching/learning the written language in all its complexity as a cultural production of human interactions. I understand that:

It is in the act of writing, in the desire to materialize their discourse in written text, that the child is entering the world of writing, [...] is becoming a writer and reader of texts, as a socio-historical subject who seeks to understand the world by appropriating the written language, recognizing himself as a citizen. (CORAIS, 2019, p. 156).

It is also in the act of writing this text that I find myself following with practices that contemplate many of the aspects pointed out above, literacy as a discursive process, writing as language and the child as a subject of speech. Practices planned and developed by undergraduates of the course of Pedagogy in the context of the extension project “The school and university partnership in children’s literacy and initial training of literacy teachers”, coordinated by me, and that, in partnership with public schools in the initial training of students in the course of Pedagogy, seeks to create teaching projects aimed at the literacy of children in the early years of basic education. Beginning in 2017, this project provides undergraduates with the opportunity to experience the daily life of the school and the construction of practices that dialogue with the reality of children, their uniqueness and their needs. Therefore, the material presented here is part of the collection of practices developed in literacy classes by undergraduates, extensionists of the project, during the school year 2018. The selection of this material is due to the fact that the work done with the class indicates ways to teach the mother tongue in a discursive perspective.

The first experience to which I refer took place in a public school with children who were not yet literate and were brought together in the same classroom. These children bore the marks of failure in the apprehension of writing; they repeatedly said they “could not read”, revealing that a discourse constituted by the words of others, parents, teachers, classmates, becomes their own, since, in a traditional perspective, it is only possible to read and write when one learns to read and write alphabetically.

Contrary to the aforementioned idea, common to synthetic methods, we understand, from Vygotski (1991, p. 132), that one should “[...] teach children the written language, and not only the writing of letters”. Our challenge – as extensionists and coordinator – was to deconstruct the perspective of failure embodied by the class, based on didactic proposals, in which discovering the symbolic function of writing is also the search for authorship and protagonism of the children.

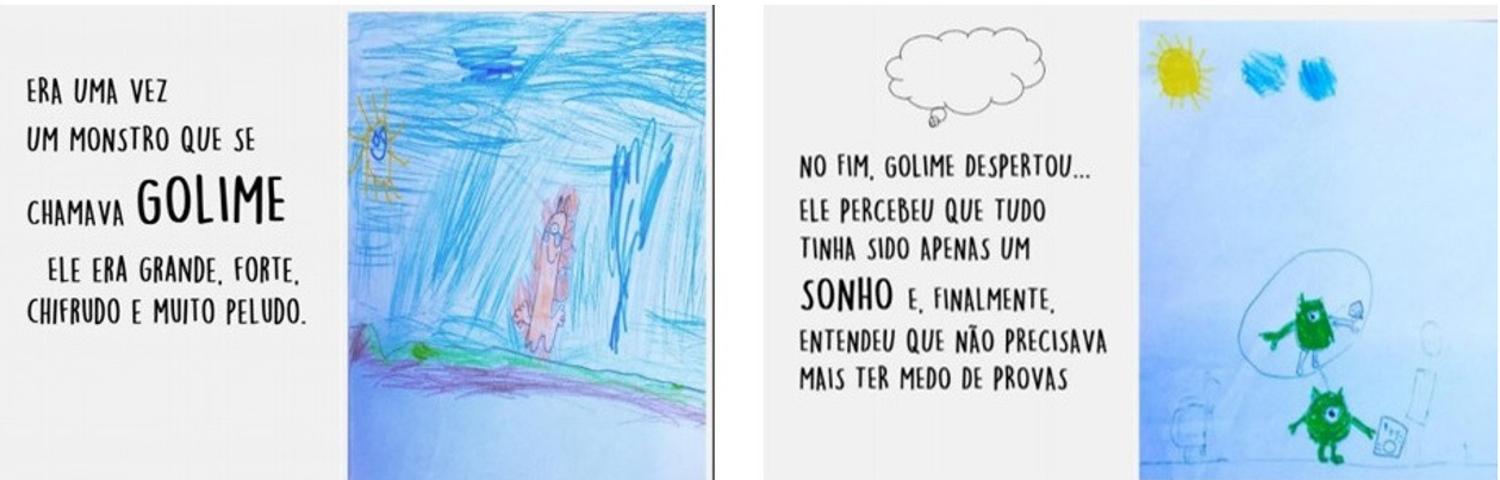

The activities developed as part of the didactic project entitled “Once upon a time” focused on expanding the children’s repertoire of fairy tales, collective text production and reflections on writing. It began with the reading of the book “Era uma vez” [Once upon a time…], by Vilardo (2012), which tells the story of a girl who, in the middle of the forest, finds a book and becomes curious to know about the story told, asking for help from other characters with reference to fairy tales, legends and fables. In the course of the text, an old lady appears who encourages the girl’s creativity to create her own story. In this way, she discovers herself as an author.

The children listened and participated in the reading of tales and fables referring to the characters of the book “Once upon a time...”. These stories were told using different strategies: reading; puppet shows; apron with characters; animation. This first stage lasted three weeks and each week two stories were narrated. After reading, the children orally discussed the stories, found space to express their opinions, impressions and feelings in relation to the text, they also also placed themselves as listeners of the other’s word, giving new meaning to their experience as readers. From this round of conversation, the children created drawings with which they wove a patchwork of stories (Figure 2), like a mosaic of interpretations and reciprocity with the word read/heard.

These activities enabled the children to participate in communication, interaction and learning situations mediated by children’s literature; contributing to the expansion of these children’s repertoire of texts; serving as a stimulus to orality through dialogue with the story read, with the teachers and among the children; and also enabled work with reading, writing and other languages as part of the development of these children’s creative and imaginative activity. We seek to break “[...] with the dichotomy between reading and writing, proposing a continuous flow of writings that ask to be read and readings that support textual production” (COLELLO, 2014, p. 175).

I understand that there is, therefore, a feeling of belonging of these students to the community of readers and writers with which they have been able to live in contact with the stories of fairy tales, which populate the childhood imagination. When they listen to the stories, they dialogue with their authors and characters, at the same time speaking about their impressions, giving their opinions and revealing their interpretations in exchanges with their peers.

It is the clearest expression of the Bakhtinian perspective that we live in a world of “words of the other” and belonging to this universe of the “word of the other” imposes on us the task of understanding it, which implies its assimilation and the appropriation of the riches of human culture (BAKHTIN, 2011, p. 379). In this dialogue with the word of the other, the students, collectively, assume the authorship in writing and create the class book (Figure 3). The children are mobilized for this writing and, considering the aspects of the discursive genre of fairy tales, they materialize their voices in the text, finding in plurality the consensus through negotiation.

This collective production allowed reflection on writing both from the point of view of aspects such as spelling, grammar, punctuation, as well as in relation to the meaning of the text as it was being developed. The children were able to express their opinions and, with the mediation of the undergraduate student, negotiated the name of the story, its characters, plot and ending, but also the formal composition of the text, its content and language. It meets the perspective of a writing always permeated by a meaning and that presupposes an interlocutor (SMOLKA, 2012).

With their copies in hand, since the class book was printed for each of the children, one of them announced: “Hey! This book is ours!” This line is the expression of the work done with them from the understanding of the sociointeractionist perspective that the development of children’s literary creation demands stimulating the child to write about a known and important theme “[...] that encourages them to express in words their inner world” (VYGOSTSKI, 2018, p. 66).

Although the text produced is quite simple, the children’s collective writing is marked by elements that allow us to say that they have expanded their repertoire of texts, insofar as their characters refer to those of the stories read, the rabbit, the turtle and the little pig. The “once upon a time”, “one day” are also marks of fairy tales. At the same time, they update these stories, situating them in their interests and everyday childhood experiences when their characters play soccer and one of them scores a goal, turning everything into a big party.

Through the perspective adopted in the activities conducted, these students could access, through the voice of the other, through the word, different discourses, they could dialogue with them, also producing their oral and written discourses, revealing impressions, hypotheses, desires and their enchantment with the universe of children’s literature. The same children who said they could not read could participate in the writing of a story woven by several hands in the “living practice of language” (BAKHTIN, 2014, p. 98). Writing as an encounter between people who assume roles in a process of negotiation of meanings and creation of new meanings; one writes for someone and expects from them a responsive attitude (COLELLO, 2014). Although it is only an experience, it is covered with meaning and significance, being characterized as dialogic, as it catalyzes the voices of these children, often silenced by the school itself.

Considering the work done with the stories and fables, based on which other activities were also conducted (Figure 4) with the words chosen from the stories read – work with the mobile alphabet, bingo, hangman game, collective storytelling with use of images, word list –, I want to reinforce the concept that children learn by correcting their own writing, in group discussions, with the qualified mediation of the teacher, endowing these moments with meaning, without erasing the child’s capacity to express their thoughts, create, imagine and talk about their feelings, placing themselves in the world through words.

From the students’ posture of euphoria and enthusiasm observed by the undergraduate in the realization of these activities, I highlight the importance that the teaching-learning practices of the written language need to be meaningful in order to be internalized, because “It is not necessary to fragment language and its teaching in order to work on phonological knowledge, nor to focus on it in an exhaustive way” (CORAIS, 2019, p. 159), as happens in synthetic methods based on training exercises, repetition, and memorization.

Based on the Bakhtinian perspective, “The system of language is endowed with the necessary forms (i.e., the linguistic means) to emit expression, but language itself and its meaningful units – words and sentences – lack expression by their very nature, are neutral” (BAKHTIN, 2011, p. 296). Therefore, the “[...] emotion, the judgment of value, the expression are alien to the word, to the language and arise only in the process of its living employment in a concrete utterance [...] the meaning of a word [...] is extraemotional” (BAKHTIN, 2011, p. 292).

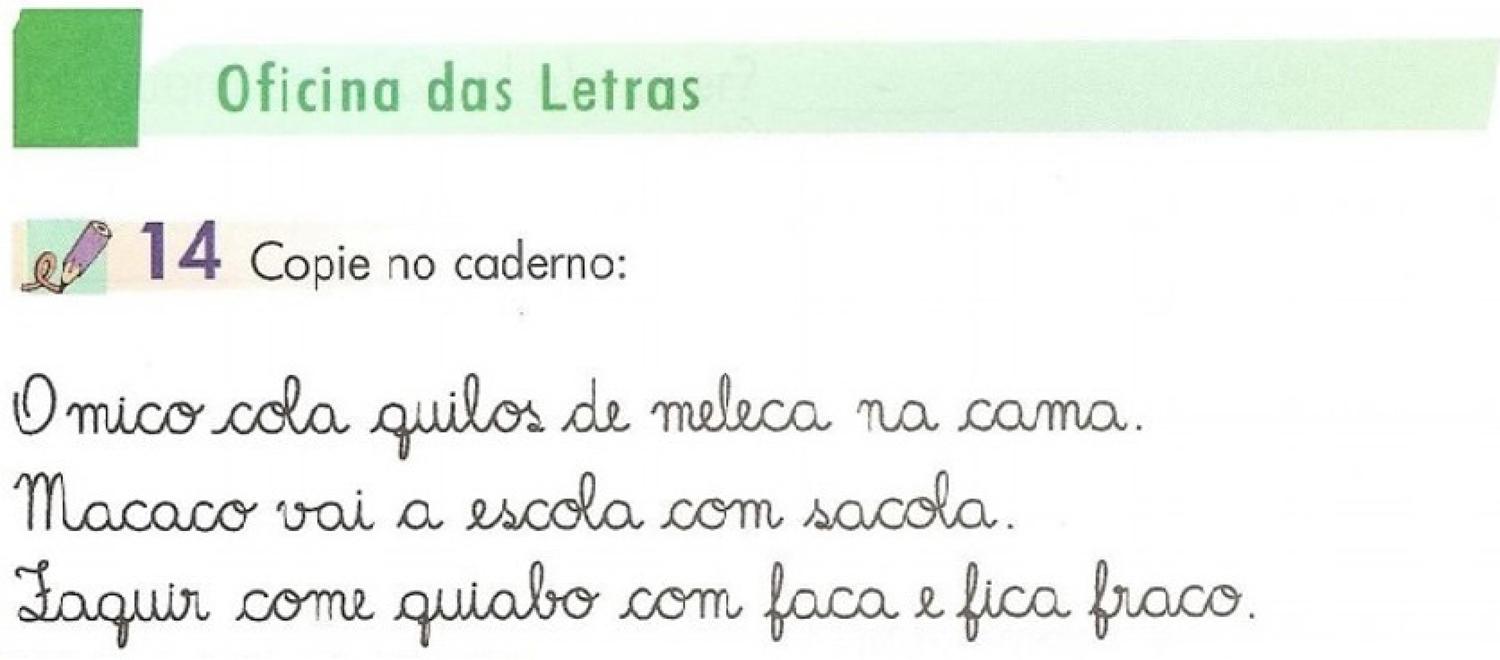

In another experience, also in the scope of the extension project that I hereby report, the undergraduates developed activities integrating reading, writing, and speaking from the reading of the children’s book Monstruosidades [Monstruosities], by Elias José (2009) with two first grade classes. Over the course of three months, the children were immersed in a fantastic universe with unconventional and fun monsters.

The work developed in these classes allowed the children to participate in activities using other languages, such as modeling with clay the monster created by each one, cutting and pasting, and drawing as forms of artistic expression, as shown in Figure 5. We seek to encourage students to place themselves as authors of their texts, to read and write while appropriating the alphabetic system.

Source: Research data.

Figure 5 The children express themselves through different languages in the making of their monsters

Once again, we seek to reconcile in the literacy practice the child’s artistic expression through the use of different materials, especially through drawing, which, in the social interactionist perspective, is a typical childhood creation, an activity that is itself stimulating or easily stimulated by others. In addition, the presence of activities organized from different languages, including writing, provides the materialization of the imagination and fantasy of children and all the feelings that they provoke.

As Vygotski (2018, p. 30) proclaims, “[...] any construction of fantasy influences, conversely, our feelings, and although this construction alone does not correspond to reality, every feeling it provokes is true, actually experienced by the person and takes possession of him.” We wanted the work with the monster theme to also be an opportunity for the children to talk about their fears and express their feelings and emotions based on the fantasy stimulated by reading the book that motivated the activities carried out.

The collective text created by the children as the final product of the project embraces the idea of “[...] textual production as a proposal of understanding aimed at a someone [...] and reading as an invitation to the reconstruction of meanings shared among interactants” (COLELLO, 2014, p. 172). For these children, the presence of an interlocutor, other students from the school, allowed the activity to gain meaning; by anticipating how these readers would respond to their production, they became involved in the dynamics of discursive interactions through writing, which required revising the writing, illustrating the text, designing the book and the cover, among other activities.

We prioritize the student’s voice in all the didactic proposals, whether in conversations, in reading groups, in their artistic productions, in individual writing, and in the collective production of the text in the book, reinforcing our understanding that the literacy practice is based on expression, dialogue, protagonism, and the child’s authorship. The appropriation of the language system takes place in the very context of its use in human interactions, in the production of discourses, and in cultural appropriation.

At the end of the process, a meeting was organized between the two groups at school so that they could present their monsters and their books, as well as their stories. The testimonial of one of the undergraduate students about this moment reveals how important this activity was in the children’s perception about being the author of their writing. “The students were eager (an excitement all around) to present the book to their classmates. [...] The students felt very important to be able to present the book to their classmates, they really felt like authors of something that was made by them, and that is why some of them wanted to read it.” Spaces for interaction were created in the school environment, by writing for others, writing gained meaning and significance for the children, as can be seen in one of the excerpts of the story created by them and in their care with the illustrations (Figure 6).

In the excerpt below (Figure 6), for example, it is interesting to note an inversion, it is not the monster that causes fear, but it is the monster that reveals his fears. The children identify with the character created by them and personify there the fear of tests, which seems to be related to this moment in which there is too much concern in preparing them for the external evaluations periodically applied in schools.

From these experiences with the children, we reinforce our perspective contrary to the idea of fragmenting the literacy process into two stages: learning the properties of the alphabetic system and learning to read and to produce texts (CORAIS, 2019). We understand that the activities of teaching writing should allow the “[...] child to say his speech, in different proposals, based on literature, on everyday life, on the event experienced inside or outside school, in personal or group narratives, or in free imagination and creation” (CORAIS, 2019, p. 161); that “It is with language that we organize our lives and it is with language that school activities are constituted, whether they are more interactive or less interactive” (GOULART, 2019, p. 18); and that the written language is “[...] an important social knowledge, an important way of meaning”. (GOULART, 2019).

I seek to reflect on paths that can be taken with children in their literacy and language work, radically opposing the discourse, present in the PNA, that the phonic method is the only scientific way to teach literacy. In this sense, Belintane (2006, p. 266) reminds us that the recommendation of the phonic perspective, by emphasizing the scientific character of a single method, creates opposition to other perspectives as if they were something “non-scientific” and that “it does not gather enough credibility to influence public policies”, highlighting its ideological character. As mentioned previously, I believe that the theoretical and methodological options in the implementation of public policies for literacy are not trivial choices. At the current moment, these choices involve policies that prioritize a greater control of the education networks, the guidelines, concepts, and strategies of the teaching work; the systematic use of phonic methodology; and “teacher training programs with more mechanisms for quality and program control” (BELINTANE, 2006, p. 271).

Final considerations

Like I started this text, I recall my entry into the teaching career as a moment of great excitement about literacy and a desire for change in classroom practices, long characterized by synthetic methods, which today are returning to the scene under the false discourse of scientificity.

What we were looking for, at that moment, as newcomers in our career, was to give a fresh look to literacy in the school context, trying to add to the practices more meaningful texts, games, spontaneous writing, and reading groups in the organization of an environment considered to be literate. At that moment there was a perspective that our teaching could make a difference in the ethical and civic education of students in search of a more equitable society.

Researches7 held with literacy teachers in different contexts revealed the diversity of situations experienced and practices, moving towards an increasingly meaningful work in the formation of our students as readers, in a more critical perspective on the teaching of reading and writing. Literacy is recognized as a much more complex social issue, which is not limited to a question of method, as so many scholars and researchers have been pointing out since the end of the 20th century.

After so many years, currently as a professor of education training future teachers, I am convinced that the discourse of using the phonic method as being the only really efficient one in literacy is a step backwards in face of so many significant and innovative experiences built in everyday school life in the teaching of reading and writing and the challenges of literacy. These challenges do not only include the permeability of theoretical and methodological perspectives in educational policies, but also the recognition of teaching staff, the improvement of teachers’ salaries, the improvement of working conditions in schools, and the mitigation of inequality in the lives of our children and their families. Cultural and economic realities are diverse and unequal, children are unique, singular, and the teaching-learning processes are heterogeneous, so it is a contradiction to think that a single method can attend to all this diversity.

As the Bakhtinian perspective indicates, no word is empty of ideological or experiential content, being the enunciation crossed by the discourse of others, in such a way that the methodological choices are not neutral. These choices are also political. It is, without a doubt, an important moment to reaffirm our commitment to public schooling and to the children of the low-income classes who need it most, which implies a literacy program that considers the student’s word in its diversity, in the search for the construction of authorship and protagonism in the expansion of their repertoire of cultural practices of reading and writing, in view of their formation as a socio-historical and cultural subject in the struggle for social inclusion.

REFERENCES

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Estética da criação verbal. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2011. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2014. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Os gêneros do discurso. São Paulo: Ed. 34, 2019. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Jamile de Oliveira. O desenvolvimento da leitura e escrita no 1º ano da escola Mons. Marinho a partir da inserção do programa Alfa e Beto. 2013. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Licenciatura em Pedagogia) – Universidade Federal do Sergipe, São Cristóvão, 2013. [ Links ]

BELINTANE, Claudemir. Leitura e alfabetização no Brasil: uma busca para além da polarização. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 32, n. 2, p. 261-277, 2006. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Alfabetização. PNA Política Nacional de Alfabetização. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2019. [ Links ]

CAGLIARI, Luiz Carlos. Alfabetização: o duelo dos métodos. In: SILVA, Ezequiel Teodoro da (org.). Alfabetização no Brasil: questões e provocações da atualidade. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2007. p. 51-72. [ Links ]

CERDAS, Luciene. As práticas das professoras alfabetizadoras como objeto de investigação: teses e dissertações de Programas de Pós-Graduação do Estado de São Paulo (1980 a 2005). 2007. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Escolar) – Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, 2007. [ Links ]

CERDAS, Luciene. Práticas e saberes docentes na alfabetização nos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental: contribuições de pesquisas contemporâneas em educação. 2012. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Escolar) – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Araraquara, 2012. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Anne-Marie. Alfabetização e formação de professores da escola primária. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 8, p. 4-12, 1998. [ Links ]

COLELLO, Silvia Maria Gasparian. Sentidos da alfabetização nas práticas educativas. In: MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo; FRADE, Isabel Cristina Alves da Silva (org.). Alfabetização e seus sentidos: o que sabemos, fazemos e queremos? Marília: Oficina Universitária; São Paulo: Unesp, 2014. p. 169-186. [ Links ]

CORAIS, Maria Cristina. Interações discursivas na alfabetização e apropriação do sistema de escrita. In: LINO, Claudia de Souza et al. FEARJ: debates sobre políticas públicas, currículo e docência na alfabetização. Rio de Janeiro: Rona, 2019. p. 155-171. [ Links ]

FIORIN, José Luiz. Introdução do pensamento de Bakhtin. São Paulo: Contexto, 2016. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. A importância do ato de ler: em três artigos que se complementam. São Paulo: Cortez, 1991. [ Links ]

GERALDI, João Wanderley. Alfabetização e letramento: perguntas de um alfabetizador que lê. In: ZACCUR, Edwirges (org.). Alfabetização e letramento: o que muda quando muda o nome? Rio de Janeiro: Rovelle, 2011. p. 13-32. [ Links ]

GOULART, Cecília. Para início de conversa sobre os processos de alfabetização e de pesquisa. In: GOULART, Cecília; GARCIA, Inez Helena Muniz; CORAIS, Maria Cristina (org.). Alfabetização e discurso: dilemas e caminhos metodológicos. Campinas: Mercado das Letras, 2019. p. 13-45. [ Links ]

JOSÉ, Elias. Monstruosidades. São Paulo: Noovha America, 2009. [ Links ]

MORAIS, Artur Gomes de. Sistema de escrita alfabética. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2012. (Como eu ensino). [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário. Métodos de alfabetização no Brasil: uma história concisa. São Paulo: Unesp Digital, 2019. [ Links ]

SILVA, Alexsandro da. Práticas de ensino de leitura e escrita no Programa Alfa e Beto: entre estratégias e táticas. Revista Educação em Questão, Natal, v. 49, n. 35, p. 99-126, 2014. [ Links ]

SMOLKA, Ana Luíza Bustamante. A criança na fase inicial da escrita: alfabetização como processo discursivo. São Paulo: Cortez, 2012. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. “Estou indignada com o MEC”. [Entrevista concedida a] Leonardo Pujol. Desafios da Educação, Porto Alegre, 8 abr. 2019. Disponível em: https://desafiosdaeducacao.grupoa.com.br/magda-soares-alfabetizacao-saeb/. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Letramento e alfabetização: as muitas facetas. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 25, p. 5-17, 2004. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda; MACIEL, Francisca (org.). Alfabetização. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2000. (Estado do Conhecimento, n. 1). [ Links ]

VILARDO, Cacau. Era uma vez... Ilustrações Bruna Assis Brasil. São Paulo: Paulinas, 2012. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semyonovich. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1991. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKI, Lev Semyonovich. Imaginação e criação na infância. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2018. [ Links ]

* English version by Jassyara Conrado Lira da Fonseca. The author takes full responsibility for the translation of the text, including titles of books/articles and the quotations originally published in Portuguese.

2- Data availability: the entire dataset supporting the results of this study has been published in this paper.

3- It is suggested to read Mortatti (2019).

4 - See the Paulo Montenegro Institute’s report, the 2018 INAF, which analyzes the reading and writing proficiency levels of the Brazilian population. Available at: https://alfabetismofuncional.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Inaf2018_Relato%CC%81rio-Resultados-Preliminares_v08Ago2018.pdf. Acess in: 22 jun 2020.

5- Once upon a time there was a rabbit and a turtle. The rabbit and the turtle lived in the forest. One day they met the little pig Alfonso. The rabbit, the turtle and little pig Alfonso decided to play ball. Piggy Alfonso scored a goal for Brazil. It was a great party.

6- Once upon a time there was a monster named Golime. He was big, strong, horny and very hairy [...]. In the end Golime awakened... He realized that it had all been just a dream, and finally understood that he didn’t have to be afraid of tests anymore.

7- See Cerdas (2007, 2012).

Received: July 07, 2020; Revised: February 24, 2021; Accepted: May 11, 2021

texto em

texto em