Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.48 São Paulo 2022 Epub 04-Nov-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202248248461por

ARTICLES

Through the thread of names: transnational relations in the process of material provision at Ginásio Paranaense (1892-1906)*

1- Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil. Contacts: gecia.garcia@gmail.com; gizelesouza@ufpr.br

This text uses aspects from Master’s and Doctoral studies situated in the debates about the provision of school material, history of education, and a transnational approach. Following the onomastic method of Carlo Ginzburg (1991), through the thread of names, we understand the subjects involved in the process of supplying and manufacturing the school furniture of Ginásio Paranaense in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Thus, the work aims to identify and map the transnational references in the consumption of artifacts targeting secondary education, checking the needs imposed and how they were fulfilled. The documental sources are newspaper articles consulted at the Hemeroteca Digital da Biblioteca Nacional; reports and documents of governamental representatives, consulted at the Departamento de Arquivo Público Paranaense. Furthermore, we used icographic sources found in the archive of Colégio Estadual do Paraná and minutes from the Museu Maçônico do Paraná. Our theoretical base was the contributions of Serge Gruzinski (2001) regarding the international and intercontinental connections in the process of historic research; Eugenia Roldán Vera and Eckhardt Fuchs (2019) with the discussion on transnational history in the educational sphere; and Cynthia Greive Veiga (2018) to understand the existing margins between schools needs and how they were answered.

Key words: Transnational history; School material culture; History of education; School furniture; Secondary education

Este texto utiliza-se de aspectos provenientes da pesquisa realizada no âmbito do curso de mestrado, bem como no de doutorado, situada nos debates sobre o provimento material escolar, a história da educação e a abordagem transnacional. Na esteira do método onomástico de Carlo Ginzburg (1991), com o fio do nome, foi encontrada uma maneira de apreender os sujeitos envolvidos no processo de suprimento e fabricação dos móveis escolares destinados ao Ginásio Paranaense em fins do século XIX e início do XX. Desse modo, este trabalho tem como objetivo identificar e mapear as referências transnacionais no processo de consumo dos artefatos dirigidos ao ensino secundário, averiguando quais necessidades eram postas e como eram satisfeitas. A empiria documental corresponde a artigos de jornais consultados por meio da Hemeroteca Digital da Biblioteca Nacional; relatórios e ofícios de representantes governamentais, consultados no Departamento de Arquivo Público Paranaense; além de fontes iconográficas encontradas no acervo do Colégio Estadual do Paraná e atas do Museu Maçônico do Paraná. O trabalho tem como arcabouço teórico as contribuições de Serge Gruzinski (2001) no que se refere às conexões internacionais e intercontinentais no processo da investigação histórica; Eugenia Roldán Vera e Eckhardt Fuchs (2019) com a discussão sobre a história transnacional no âmbito educacional; e Cynthia Greive Veiga (2018) para compreender as margens existentes entre as necessidades da escola e como estas são atendidas.

Palavras-Chave: História transnacional; Cultura material escolar; História da educação; Móveis escolares; Ensino secundário

Introduction

Faced with realities to be studied from multiple scales, the historian has to turn himself into a type of electrician in charge of re-establishing the international and intercontinental connections that national historiographies have disconnected or hidden, blocking their respective frontiers.

Serge Gruzinski

An issue proposed by Serge Gruzinski (2001), when exploring the connected histories2is to bypass Eurocentric narratives in the investigations of Western historians and exhume the historic connections. Thus, Gruzinski understands that the historian’s role is to “make appear the continuities, the connections, or simple passages, often minimized (if not excluded from the analysis)” (p. 177). Hence, the author understands that the objects taken for a historical analysis articulate multiple contact points and junctions that end up producing new syntheses, which should emerge in the process of writing history3.

Regarding the history of education, Martin Lawn (2014), translated by Rafaela Silva Rabelo, states the difficulty in contemporary Europe in establishing themes that are not reduced to national configuration. The author explains that, when checking the circulation of certain objects, they end up losing authorship and are taken with a national characteristic, while other contact points are lost or become invisible. In other words, “history of education has been dealing with its study object as naturally national, as if it had impermeable frontiers, common institutions, different places, and native objects” (LAWN; RABELO, 2014, p. 132). Therefore, when we look at our study object, the process of supplying school desks, we tried to establish a more complex analysis, observing other facets in the material composition of Paraná secondary education.

Cynthia Greive Veiga (2018) explains the relations between school needs and how they are fulfilled should not be read a-historically – on the contrary: consumption relationships, in the case of school material provision, go beyond economic relations, also establishing socio-historic constructions. Supported by these assumptions, this study aims to understand, in the scope of Ginásio Paranaense, between 1892 and 1906, how was the process of supplying school furniture of this institution, in the sense of checking the circulation of subjects involved, the veiled systems of references, as well as the existing margins between school needs and its fulfillment.

These aspects allow us to problematize an operation established from material culture. According to Ulpiano Toledo Bezerra de Meneses (1998), we should be careful with the fetish of the object- that is, we should not reduce the analysis of the documental piece only to its physical properties. It is important to evaluate the physical/sensorial and the biography of the object (involving the production relation and social interaction) to identify the uses and senses articulated by the society which produced it. Regarding school material culture, Escolano Benito (2017, p. 9) explains that using this approach allows us to retake the “operatory rules that weave the relationships between people and things”, allowing thus to know a school culture and a school material culture.

Hence, when entering the empirical research, the historic weave developed here was designed based on the names intertwined, having Carlo Ginzburg’s (1991) considerations about the onomastic method as theoretical support. According to the author, this allows us to investigate the contextual weaves connecting the subjects. Three names are key to this research: Pedro Rispoli, Affonso Lubrano, and Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva. The first two are Italian immigrants who built many businesses in Brazil- among them, woodworking factors associated with the creation of the school furniture for Ginásio Paranaense. The third one, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, as the General Director of Public Instruction of Paraná, can be seen as a cultural mediator (GRUZINSKI, 2014) who helped the circulation of artifacts and knowledge, and their respective provision.

The initial research focus encompasses the first regulation of Ginásio Paranaense, published in 1892, when discussions about intuitive teaching and the equalization of Paraná secondary education with that of Ginásio Nacional do Rio de Janeiro were in vogue. We established 1906 as the starting point when Pedro Rispoli signs the contract to produce the furniture of Ginásio Paranaense, mainly the Cabinets of Chemistry, Physics, and Natural History.

In this scenario, also grounded on Eugenia Roldán Vera and Eckhardt Fuchs (2019), we believe that the material supply of Ginásio Paranaense took place through a process that “crossed borders”, because its consumption system was supported by the international circulation of catalogs, artifacts, and subjects, allowing connection points that contributed to the fabrication of school furniture in Paraná.

The thread and the name: connected by a school desk

The weekend was close and those who flipped the pages of the A República newspaper on that summer Thursday of 1904 would find an unusual invitation for an event on the following Saturday: to visit the Exposição Paranaense [Paraná Exhbition]. The newspaper articled called attention to the school desks to be displayed in the main pavilion of the new Ginásio Paranaense, which would soon be open. They had a “special style never before seen among us” (A EXPOSIÇÃO, 1904, p. 2), the writer refers to the furniture origin and their supplier. According to the article, due to the indication of the General Director of Public Instruction, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, Lubrano Woodwork was responsible to make the desks, which were a large part of the furniture of Ginásio Paranaense. It is interesting to notice that the manufacturing references are not limited to the borders of Paraná, as the desk made by Lubrano was based on a sample brought by the director from a model school in the state of São Paulo (A EXPOSIÇÃO, 1904).

Three months later, in the same year and newspaper, other evidence about the material provision of Ginásio Paranaense was published. On May 12, under the title “expedients”, by the order of Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, two experts were designated to evaluate the school furniture intended for Ginásio Paranaense, manufactured by the woodworker Pedro Rispoli (PARANÁ, 1904, p. 1). As stated by Carlo Ginzburg (1991, p. 174): the “Ariadne’s thread that guides the researcher in the document maze is what distinguishes an individual from another in all known societies: the name”. Hence, by the onomastic method, we have identified three names connected to the provision of school desks for Ginásio Paranaense: Pedro Rispoli and Affonso Lubrano, responsible for the factory; General Director of Public Instruction, interested not only in buying the best furniture, but also to offer quality references to the process of manufacturing.

This way, dear reader, we invite you to follow through the thread of names, and the trails left by these subjects to understand their relationship with the material installation of Ginásio Paranaense.

On the trails of Pedro Rispoli and Afonso Lubrano

The movement of so many people among the continents establishes bonds and offers a continuous source of information and knowledge.

Serge Gruzinski

It was 1895 when the Italian Pedro Rispoli boarded the “Vapor Satellite” to cross the Atlantic Ocean to reach Brazil. He got off in Rio de Janeiro; however, he would set his home in Paraná, living in a small hotel in Curitiba (CÓDICE…, 1891, 1894, 1895). Three years later, Rispoli’s data are mentioned in the newspaper A República: 24 years old, son of Ângelo Rispoli, married, artist, living in Riachuelo (ALISTAMENTO, 1898). Regarding Affonso Lubrano, we have no records of his arrival in Brazil, whatever was possible to discover was connected to the traces left by Rispoli. Lubrano appears as a strong competitor in the woodworking field and, in the newspaper advertisements, both have similar proposals and endeavors.

As stated by Michel de Certeau (2015), the historian’s gestures connect the ideas to the places. For this reason, we have opted to alternate the scale of observation of those subjects to understand the factual panel that precedes their arrival in Brazil. At the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, more than 70 million Europeans crossed the Atlantic Ocean seeking better work conditions. According to Sérgio Odilon Nadalin (2017, p. 62), in this period in Europe, there was a scenario of overpopulation and the precariousness of services aggravated by the Industrial Revolution. Thus, several people “emigrated to work, plow, plant, and raise; to build something of their own”.

Elaine Maschio (2012) explains that the circulation of propaganda pamphlets between Brazil and Europe was one of the strategies of commercial agencies to convince foreigners to emigrate to Brazil. Contracts and agreements were also established through provincial states. This way:

[…] agents advertised, recruited settlers, prepared the land lots, and were responsible for the transportation, installation of setters, and settlement administration. The government was responsible for defining the settlers’ profile and paying for the total costs of this process, in general, stipulated by the agents themselves. Immigration was a business that generated meaningful profits for the businessmen in the field. (MASCHIO, 2012, p. 49).

In a report for the Legislative Assembly in 1876, the president of the province, Adolpho Lamenha Lins, makes some declarations about the settlement process in Paraná; For him, the Paraná Province was the most appropriate in the Empire “to receive immigrants from all countries, hard-working settlers that seek a new home and country to find their well-being and elements to establish a future for their children” (LINS, 1876, p. 77). The word hard-working associated with the displacement and foreign occupation in Paraná lands was not simply rhetorical: there are pieces of evidence about the expectations on the arrival of immigrants and also the economic scenario of the Empire. To Lins (1876, p. 78), “the lack of manpower is an economic fact originated at the end of commercial treats with England”. With the abolitionist laws- first, the Lei Euzébio de Queiróz and later the Lei do Ventre Livre –, the political representatives had to find alternatives to substitute the enslaved workforce, thus creating strategies

[…] to invite the foreign migration wave and since September 18, 1850, the so-called Lei das Terras, the Imperial government became the immediate tutor of the immigrant, providing for their well-being, from the transportation from their original countries until their definitive establishment in their destined place. (LINS, 1876, p. 78).

According to Rafaela Mascarenhas Rocha (2015), we can see differences in the migration motivations between São Paulo and Paraná. In the former, the immigrant workforce was used to “substitute the enslaved workforce in coffee plantations, in a system originally called “partnership”. While in Paraná, the initiative was focused on the development of family agriculture” (ROCHA, 2015, p. 56). This situation took place exactly because the food production in Curitiba did not have the same power as the economy of Mate herb. For this reason, the installation of agricultural settlements around the capital became known as the “green belt” of the city. These immigrants would daily go to the capital “with their wagons full of wood, cereals such as beans and corn, legumes and fresh vegetables; following the pathway of the neighborhoods Campina do Siqueira, Mercês, and Alto do São Francisco, until the city center” (MARANHÃO, 2014, p. 53).

Maschio (2004, p. 3) points out that the largest wave of Italian immigrants reached Paraná between 1875 and 1878, a total of 4,350 immigrants, through a “contract established between the President of the Province, Venâncio José Lisboa and the businessman Sabino Tripodi”. Together with this, in the period between 1870 and 1890, there was a greater move of immigrants to the province, establishing more than 20 settlements of Italian families and other ethnicities. The author highlights that “between 1829 and 1934 Paraná received 47,731 Polish people, 19,272 Ukrainians, 13,319 Germans, and 8,798 Italians” (MASCHIO, 2012, p. 48). The Italian flow was the 4th largest contingent in the immigrant proportion that arrived in the state.

Even though Paraná had a substantial production of agricultural goods, such as the Mate herb and subsistence farming, some Italian immigrants had other purposes, as stated by Maschio (2012, p. 19), there were “families and individuals that established themselves in the center of Curitiba and developed commerce, worked as liberal professionals, or as factory workers. For example, the urban immigrants that we focus on in this study: Pedro Rispoli and Affonso Lubrano – subjects that were part of the foreigners dedicated to commerce and industry, as owners of different establishments.

Paul Ricouer (2018, p. 222) explains that the change of scale does not make “the same things bigger or smaller, in greater or smaller characters, […] we see different things”. Because of that, the scale here resumes the empirical consult on some actions of Pedro Rispoli and Affonso Lubrano in Curitiba. The financial authority and the commercial circuit of these subjects can be seen by the array of investments they owned, as well as by the “complicity network” they mobilized (GRUZINSKI, 2014, p. 77).

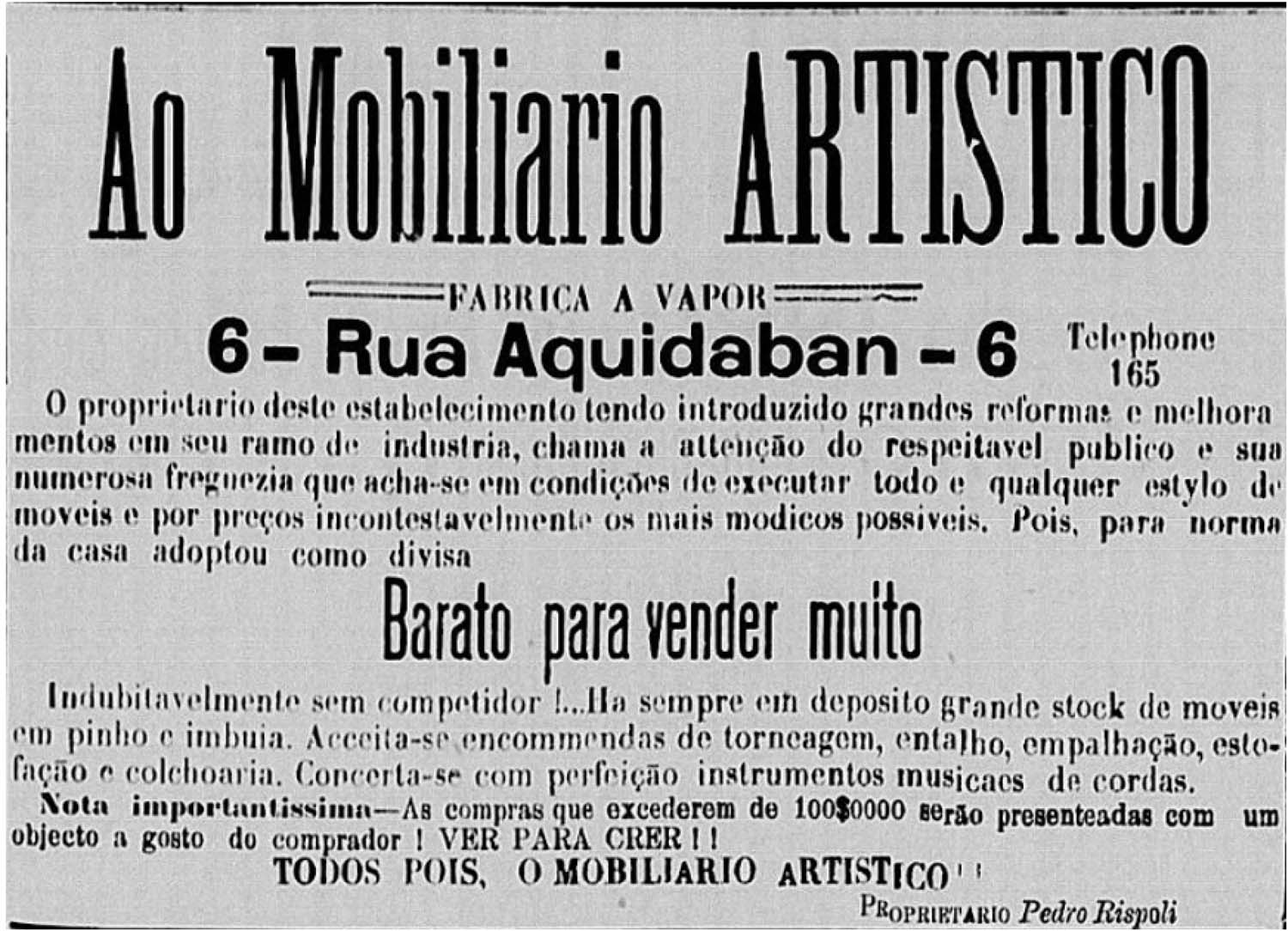

Named “O Mobiliário Artístico” [The Artistic Furniture] the commerce of Pedro Rispoli was located at Aquidabam Street (currently Emiliano Perneta Street), in Curitiba. The newspaper poster to publicize the factory states that the owner introduced “great renovations and improvements in his industrial field [and] can execute all and any style of furniture at, unquestionably, the most affordable prices possible” (AO MOBILIARIO, 1906, p. 3). The factory also kept in storage, pine, and imbuia furniture, and accepted demands of lathing, entailing, stuffing, upholstering, padding, and repairing musical instruments. In the slogan, the owner announced they sold “cheap to sell a lot”, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Source: “Ao mobiliário artístico” (1906, p. 3).

Figure 1 Poster of the steam factory of Pedro Rispoli in 1906

Marcenaria Lubrano, owned by Affonso Lubrano, was also announced in the newspaper A Notícia on May 10, 1906. The steam factory was “neatly” established in the new address at Liberdade street, nº 27 (current Barão do Rio Branco Street) having a “permanent exhibition of furniture, where people can […] find furniture of their taste” (MARCENARIA, 1906, p. 4). Furniture for the dining room, bedroom, boudoirs, offices, and desks were some of the products produced by the factory, besides using “the best woods of Parabá, which are: imbuia, oak, cedar, pine, etc, etc.” (MARCENARIA, 1906, p. 4).

Other traces left by these subjects in the commercial circuit can be seen in the newspaper pages: besides his steam factory Pedro Rispoli, had a furniture club (CLUB…, 1904), a cooperative of buildings (COPERATIVA…, 1908), had activities in a car factory, and in the creation of luxury furniture (DIARIO DA TARDE, 1907). Affonso Lubrano’s activities are similar to Rispoli’s: besides also manufacturing luxury furniture, he had a furniture cooperative (GRANDE…, 1908), and a car cooperative, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: “Cooperativa de carros” (1907, p. 3).

Figure 2 Poster of the car cooperative Affonso Lubrano in 1907

By the number of endeavors cited, we can see that these men had a prestigious place in the social fabric. Holders of considerable capital, these entrepreneurs could participate in various public notices and, thus, keep another front in the commercial dispute of Paraná. Among their action niches, the schools were a favorable field for the furniture area. Relying on a specialized workforce and factory technology, Rispoli and Lubrano, earned several biddings to supply furniture for Paraná public schools (GARCIA, 2020). What the public notices and newspaper articles do not show is the extra commercial connection of these subjects with the Director of the Public Instruction of Paraná. Before answering this question, it is important to understand the work of Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva in Paraná’s social context.

As a medical doctor, he could not only talk about the object of medicine but also had the authority of commenting on pedagogical and material aspects of school. The debate between physicians and bachelors (in Law and Medicine) about the school scenery was recurrent at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. These professionals commonly held positions of inspection and direction of Public Schooling: it was no different with Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, appointed by the governor Francisco Xavier da Silva, on October 22, 1900, for the position of General Director of Public Instruction in Paraná SOUZA, G., 2004). During the period he held the office (1900-1904), the Director wrote reports expressing his concern with school materiality and, on trips to São Paulo, under a governmental commission, he visited some educational establishments that, in his opinion, presented “a model organization, even luxurious, which are not far from those of more civilized countries” (SILVA, 1904, p. 6).

It is important to consider that the issues of hygiene and the value of modern architecture and pedagogy were already part of a debate that pervaded the 19th century. However, the schools created in the state of São Paulo (mainly the so-called grupos escolares) would enter the imaginary of society as signs of modernity announced by the Republican regime (SOUZA, R. F., 1998). To Marta Carvalho (2003), São Paulo school

[…] is strategically built as a sign of progress established by the Republic; a sign of modernity that worked as dispositive of fight and legitimation in the consolidation of the hegemony of this state in the Federation. The investment was prosperous and the São Paulo educational system is successful in organizing itself in a model system, in a double sense: in the logic that presided over its institutionalization and the exemplary force it has in the initiatives of school remodeling in other states. (CARVALHO, 2003, p. 225).

Jacques Le Goff’s (2003, p. 175) statement that « modernity awareness emerges from the feeling of rupture with the past”, helps us to interpret this historic event. Faced with this, we perceive a constant movement in the journalistic rhetoric and the reports of government representatives, establishing in the Republican regime a new redemptive order, while the monarchical regime would represent a precarious context that only the Republic could change. However, we know that the force of this event was related to a rhetorical strategy: though the Republic announced its concern with the educational scenario, there was no significant change in the first decades of the regime (SOUZA, G., 2004; BENCOSTTA, 2001).

In a Mason newspaper, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva was praised in 1901 as an educational authority that fought for the civic cause:

Also masonry, an invaluable factor of Freedom and Civism, for more than a year, under the auspices of the Respectful Lodge Fraternidade Paranaense, started in the School José Carvalho an eloquent series of civic lectures. […] The illustrious Director of Public Instruction came to brightly sanction them, granting an official stamp. Worthy of praise! (MOZAICO, 1901, p. 62, our highlight).

The School José Carvalho, mentioned by the newspaper, was created by the masonic lodge Fraternidade Paranaense4. According to the documents at Museu Maçônico Paranaense [Paraná Mason Museum], Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva was a member of this lodge. Coincidentally, Affonso Lubrano and Pedro Rispoli were also members. However, these subjects were also affiliated with another mason lodge: Unione e Fratellanza5 – we highlight that, in this lodge, the meetings and document records were held in Italian. However, we stress that the trails left by these subjects show the affinity of the conceptions shared by a political context.

In Brazil, according to Giana Lange do Amaral (2017, p. 58),

[…] the whole process of the Republic Proclamation also resulted from the work of politicians connected to Masonry. This became evident when we see that: the Republican Manifest of 1870 was written by the Gran-Master Saldanha Marinho, receiving signatures of a great number of masons: the “Republican Club” was presided by mason Quintino Bocaiúva; masons composed the first Provisory Government.

In fact, as a representative of the Republican government, many times, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva wrote in his reports about his concern to establish in public instruction the principles of laity and civic education. One of the constant agitations in his position was to “establish civic education in schools. Considering that, ex vi of political constitution, education became laic, by the exclusion of religious education, it seems to me that civic instruction has inescapable importance” (SILVA, 1904, p. 14). Besides the civic education in the national parties calendar, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva insisted on the conferences of civic education held in public spaces and announced through the lenses of Ginásio Paranaense.

Following this perspective, we perceive that the values surrounding the Republican precepts also reached the Mason philosophy. Therefore, it does not seem to be a coincidence that Affonso Lubrano and Pedro Rispoli rendered services, under the recommendation of Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, to the main institutions of the Republican regime, such as schools, kindergartens, Normal schools, and the Ginásio Paranaense (GARCIA, 2020). Because Masonry is here considered as

[…]a potential and aggregating locus, as a sociability space of intellectuals that ground ideas that are consolidated in the process of implementation of the Republic. Masons, who in their collective spaces, mason lodges, shared aspects of the liberal and positivist ideals, sought a new society based on order and progress. (AMARAL, 2017, p. 58).

Therefore, we believe that the places of action of these subjects reveal a “network of complicity” (GRUZINSKI, 2014, p. 77) that gave Pedro Rispoli and Affonso Lubrano the opportunity of satisfying the material demands of the Republican school, as well as benefiting them in the commercial circuit. Hence, after building the weave that connects these subjects, we still have to know other systems of reference that were present in the manufacturing of the furniture of Ginásio Paranaense.

The transnationalization of school artifacts: the installation of the Ginásio Paranaense and its specialized spaces

Even before Paraná left the protection of São Paulo, the old Comarca of Curitiba had inaugurated in 1846 the establishment of an institution to shelter secondary public instruction: “Licêo de Curitiba” (ZACHARIAS, 2013a, p. 21). Mariana Zacharias (2013a) points out that the history of secondary education in Paraná is marked by an unstable condition when offering its courses, as they were extinguished and recreated several times. According to the author, the definite extinction of the Licêo happened in 1874. However, in 1876, a preparatory institute was created, which became known as Instituto Paranaense. To this building, the Normal School was attached to be responsible for the formation of elementary education teachers. In 1892, the institute was called Ginásio Paranaense. The Library of the Capital and the General Direction of Public Instruction were in the same space.

Before diving into the processes of material installation of secondary education in Ginásio Paranaense, we once again need to change the observation scale to understand the historic scenery that precedes secondary education in Paraná. According to Clarice Nunes (2000, p. 36), the “emergency of this school form, is marked by university prestige”. However, the author shows that Brazilian schools were not directly born from this relationship but from “the policy of separation established by the Jesuit order between the teaching of humanities targeting the children of wealthy settlers and the education for the Indigenous” focused on catechism principles (p. 38).

Still, according to Nunes (2000), primary education would be grounded on the use of civilizing principles, in the sense of building governability pillars over the nation. Secondary education would be responsible for the formation of “an illustrious and intellectual elite, more fully inserted in the attributes of freedom and property, holder of privileges in the small circle that participated in the State power, in the local level, as well as in the broader Empire level” (NUNES, 2000, p. 39). This way, targeting the formation of illustrious young people, secondary education would provide a

[…] solid general culture, supported by ancient and modern humanities, aiming to prepare the leading individuals, that is, the men who would assume the greater responsibilities within the society and the nation, holders of the conceptions that would be infused in the people. (NUNES, 2000, p. 40).

Published in the newspaper A República, the Regulation of Ginásio Paranaense anticipated, in its first article, who was the public of secondary education and its aim: to the young people of Paraná to prepare them to enroll in the higher education establishments of the Republic and for the knowledge of “fundamental elements of general science”. Furthermore, “the course will be called Gymnázio Paranaense, attached to it, there will be a Normal School aiming to prepare teachers for the primary schools in the State” (PARANÁ, 1892, p. 2).

It is important to point out that during the Reform Benjamim Constant, in 1890, there was the equalization of secondary education in the main federal institution: the Ginásio Nacional, located in Rio de Janeiro (at the time, Brazil’s capital). With this, “the equalization aimed to give a unity to secondary education nation-wise, bringing with it supervisory measures, but not eliminating the preparatory examinations” (ZACHARIAS, 2013a, p. 37). Though the issue of equalization tried to promote national unity on the content to be taught, the initiative ended up becoming a great challenge to Brazilian cities and states. The same took place in Paraná, as the subjects of Physics, Chemistry, and Natural History demanded the installation of spaces with experimental characteristics, requiring appropriate furniture and technology for teaching.

When writing about secondary education, in the 1903 report, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva informs that, to follow the model of Ginásio Nacional, there needed to be “some improvements, whose main goal is to create a cabinet of Natural History and a Physics and Chemistry Laboratory”(SILVA, 1904, p. 15). To him, the installation of specialized equipment would substantially improve teaching, as “the purely theoretical study is almost completely unsuccessful” (p. 15).

About these questions, the director enthusiastically announces that “the founding stone has been settled”: the new building under construction to welcome the Ginásio Paranaense. About the hygiene conditions and aspiring an architecture considered modern, the new Ginásio was inaugurated in February 1904. However, 10 months later, the new General Director of Public Instruction, Reinaldo Machado, affirms in a Report that secondary education had not yet reached equalization with Ginásio Nacional. Furthermore, he stated that one measure the government should take, as soon as possible, would be the “acquisition of a Laboratory of Physics and Chemistry and a Cabinet of Natural History, which has been keenly missed for the practical teaching of these sciences, not only for the Ginásio students but also those of Normal School” (MACHADO, 1904, p. 23).

We have seen, through official letters and contracts found in the Public Archive of Paraná that, though the building was inaugurated in 1904, only in 1906 the government could gather efforts to provide the building with the necessary furniture for the Cabinets of Chemistry, Physics, and Natural History (CERQUEIRA, 1906).

On May 16, 1906, the Bachelor Arthur Pedreira Cerqueira, General Director of Public Instruction, was authorized by the government to sign a contract with Pedro Rispoli to manufacture the furniture needed for the buildings of Ginásio Paranaense and the Normal School. In the contract, they define the deadline of 60 days for the supplier’s production, which could be prorogated. We also found the list of pieces of furniture to be made:

250 pine desks, imitating imbuia varnished with 1.15 of length, 0.80 of height, following the model of fig.11 of the Catalog of “Maison Les Fils d’Emile Deyrolles”, 13 armchairs of imbuia carved and stuffed, the largest and tallest for the table of the Congregation […] 24 simple chairs of imbuia carved and stuffed following the chosen model. 1 pine lavatory imitating imbuia with a marble stone and a mirror […] 14 benches with iron frame for students’ recess with wooden seats. 2 small tables lathed and varnished. 1 platform for the Congregation painted table of 5 m in length, 3.30 in width. 4 blackboards with an easel of 2.40 meters high and 1.60 in length, and 1.10 wide. 24 clipboards for drawing painted black with 0.50 x 0.60 all with two frames with glass for schedules (free). (CERQUEIRA, 1906, p. 56-57, our highlight).

The contractor announces that the desks should follow “the model of fig.11 of the Catalog of ‘Maison Les Fils d’Emile Deyrolles’”. Until now, we could not find the referred catalog but we suspect that Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva was the mediator in the circulation of the artifact, considering that he wrote in his 1903 report that “through printed catalogs of important commercial houses of Europe, the government could order the material for the laboratory in good conditions” (SILVA, 1904, p. 16).

The reproduction of artifacts by local woodworkers through catalogs or even detailed descriptions of the contractors is discussed by Wiara Alcântara (2016) in a study about the transnationalization of school objects in the late 19th century. According to the author, in this period many companies signed patents to protect the intellectual production in the production of objects, as was described in the catalogs, with possible punishment for those who reproduced the exhibited artifact (ALCÂNTARA, 2016).

It seems that, though knowing the risks, the educational representatives of Paraná did not hesitate to take the catalogs of Maison Émile Deyrolle as references to their orders for carpenters and local factories. Furthermore, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva circulated in São Paulo, to know the main educational centers that also kept commercial relations with Maison Deyrolle. According to Diana Vidal (2017) and Wiara Alcântara (2018), the purchase of products from Maison Deyrolle all over the Brazilian empire was recurrent in the late 19th century, with the increase of experimentalist practices. Created in 1831 by Jean-Baptiste Deyrolle, the Maison Émile Deyrolle provided services related to the collections of Natural History, “as well as scientific equipment, taxidermy pieces, osteology, school furniture, and wall panels”6 (NAISSANCE, 2008, our translation).

In Brazil, the consumption of these objects for the teaching environment corresponds to a new pedagogical model: the intuitive method of teaching or the lesson of things. According to Alcântara (2018, p. 345),

The intuitive method was generalized, in the second half of the 19th century, in Europe and the Americas, contraposing book education, as an indispensable method for the renovation of education. In the transition of the 19th to the 20th century, with the intuitive method, the world of artifacts invaded schools. In this period, emerged new types of scientific artifacts [...] the Cabinet of Physics, the Laboratory of Chemistry, the Astronomic Observatory, the Cabinet of Pharmaceutical, the Anatomic Theater, the Cabinet of Natural History, and the Botanic Garden. These new learning spaces emerged in school in a cultural context of valuing knowledge production and learning based on observation, experience, physical demonstration of things, and palpable phenomena.

As we can see in the reports of government representatives, it was not different in the state of Paraná: all the investment in a modern teaching environment, mainly with Ginásio Paranaense (matching Ginásio Nacional), had, in its prerogative, the distance from a “purely theoretical” education, towards a more experimental one.

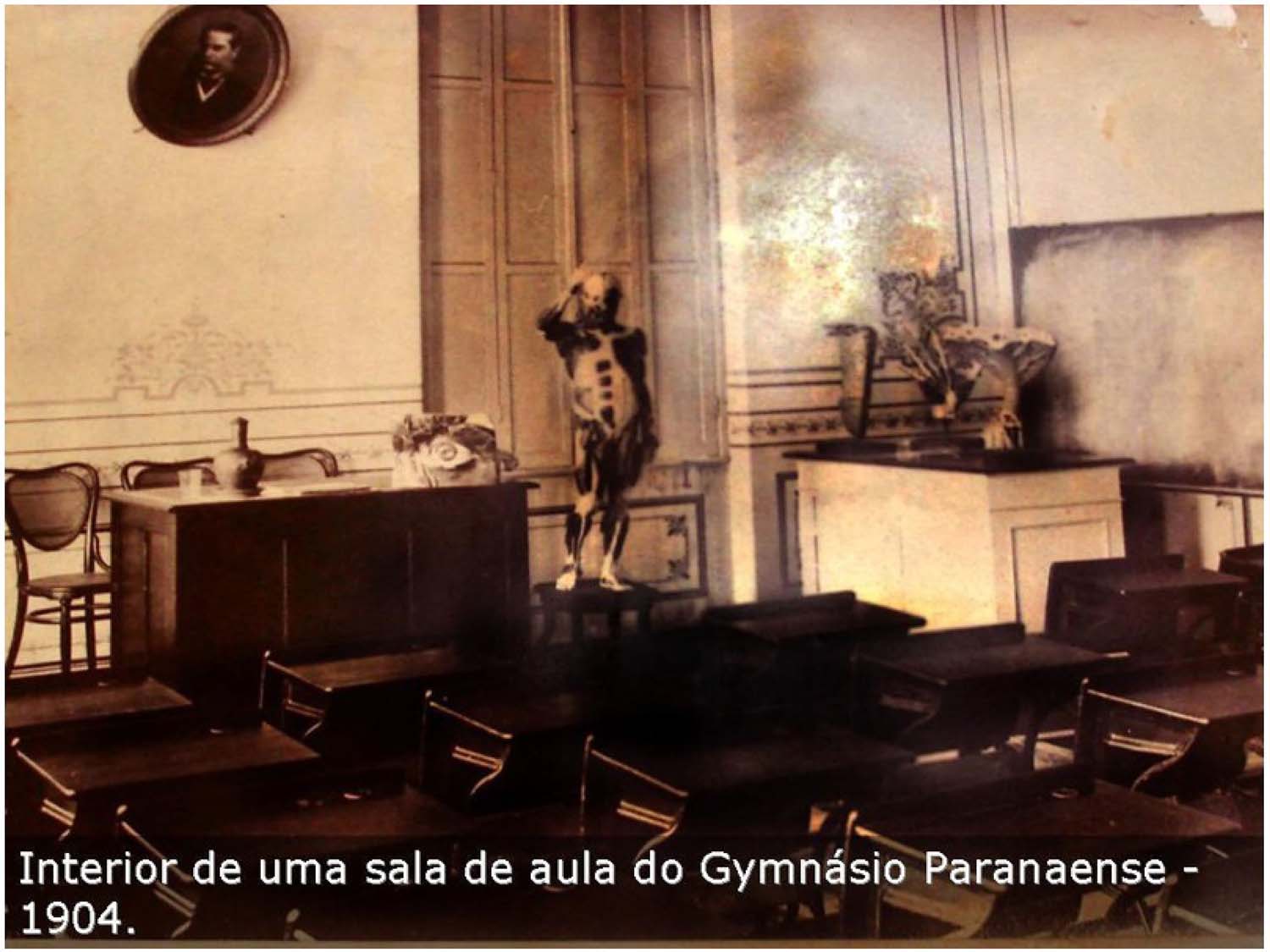

Figure 3 shows a classroom of Ginásio Paraense in 1904. In the center, we can see a model of human body anatomy imported from Maison Émile Deyrolle.

Source: Photo digitalized from the archive of Colégio Estadual do Paraná (1904).

Figure 3 Inside a classroom of Ginásio Paranaense – 1904

Another point to be highlighted in this image alludes to the discussion that opened this article: the manufacturing of furniture by the Lubrano Woodwork, for Ginásio Paranaense, in 1904. The coinciding dates suggest that the furniture appearing in the photo has been made by Afonso Lubrano, under the supervision of Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva.

Regarding Pedro Rispoli, we know that, besides the contract signed in 1906, received the amount of $240,000 in 1909, “for the manufacturing of furniture for the cabinets of Physics and Chemistry of Gymnasio Paranaense” (PARANÁ, 1909, p. 1). Figure 4 refers to these teaching environments. However, our document source was kept in a photo album called “Antigo Ginásio”[Former Ginásio], with the date of 1941. We can imagine that part of the furniture in the space still refers to those manufactured by Pedro Rispoli.

Source: Photo album of the “old ginásio”, dated from 1941.

Figure 4 Inside a classroom of former Ginásio Paranaense

Considering the characteristics of carving and the robustness of the wood, with apparently imbuia shelves, we might imagine that these cabinets were manufactured by Pedro Rispoli in 1909. Besides this, other objects, such as animals and skeletons in the showcases, typical of Maison Émile Deyrolle, suggest to us that this room was used for Natural Sciences studies, a space reserved for experiences and intuitive teaching.

Thus, in the toolbox used by the historian to understand the productions of the past (GRUZINSKI, 2014), it is clear that the installation of Ginásio Paranaense establishes a complex and international arrangement, highlighted in its materiality. The school furniture and objects shown here reveal fragments of cultures in contact. From Italian manufacturers to French objects, we can observe a “cross-border history”, in the terms of Lawn and Rabelo (2014). The actors in this web translated ideas that had contacts in different scales, such as the circulations and translations made by Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva when visiting São Paulo (with the school desks), the contact with Rio de Janeiro (by the equiparation with Ginásio Nacional), the appropriations of French reference (as the catalogs of Maison Deyrolle), and the reaction with Italy itself (from the manufactures Pedro Rispoli and Affonso Lubrano).

Final remarks

The lines that converge to the name and leave from it, composing a type of fine mesh web, provide the observer with a graphic image of the social fabric in which the individual is inserted.

Carlo Ginzburg

Who would have guessed that subjects from Italy would make furniture in Brazil, under local and global aspirations? Tracking the circuits described in this article made us understand the implicit systems of references in the process of manufacturing furniture in Paraná. Following Carlo Ginzburg (1991, p. 175), we could say that more than the visualization of a panel of individuals, the tracing of this “web of fine thread” allowed us to observe hybrid actions, materialized in school artifacts.

According to Cynthia Greive Veiga (2018), from the consumption that the school establishes to satisfy their needs, it is possible to identify a school economy. Supported by Polanyi (2012) and refuting the formal conception of the economy as an entrance of the market to satisfy a scarcity, the author starts from a broader concept, interpreting economy as “the processes of human interaction with their natural and social environment, to produce what is needed to live” (VEIGA, 2018, p. 32). This way, looking at our object – Ginásio Paranaense –, we can see how the processes of interaction between government representatives and manufacturers took place to supply secondary schools with specialized spaces.

For this reason, we point out that, from the objects consumed by Ginásio Paranaense, it was possible to identify which needs would be fulfilled. As we have seen in the report of Victor Ferreira do Amaral e Silva, the criterion used to match Ginásio Paranaense with Ginásio Nacional was the installation of Laboratories of Chemistry and Physics, as well as a room for Natural History. These demands reveal a period in which book knowledge was no longer in vogue: students needed to enter the field of observation, and empirical sciences, translated by intuitive teaching.

Thus, the circuit of these arrangements has revealed a transnational economy, filled not only by national references but also by subjects and knowledge that circulate internationally. Roldán Vera and Fuchs (2019) affirm that the transnational history approach can be understood as a history that crosses borders; under this perspective, it was possible to see that the material composition of Ginásio Paranaense revealed aspects that transcend its national configuration, establishing a more complex process of supply, with scales that varied between regional and intercontinental consumption.

REFERENCES

A EXPOSIÇÃO. A República, Curitiba, ano 19, n. 28, p. 2, 4 fev. 1904. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215554&pesq=&pagfis=15299. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ALCÂNTARA, Wiara Rosa Rios. A transnacionalização de objetos escolares no fim do século XIX. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v. 24, n. 2, p. 115-159, 2016. [ Links ]

ALCÂNTARA, Wiara Rosa Rios. Cultura material e história do ensino de ciências em São Paulo: uma perspectiva econômico administrativa. Rivista di Storia Dell’Educazione, Firenze, v. 5, n. 1, p. 343-361, 2018. [ Links ]

ALISTAMENTO eleitoral. A República, Curitiba, ano 13, n. 183, p. 2, 23 ago. 1898. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215554&pesq=&pagfis=8921. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

AMARAL, Giana Lange do. Os maçons e a modernização educativa no Brasil no período de implantação e consolidação da República. Revista História da Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 21, n. 53, p. 56-71, 2017. [ Links ]

AO MOBILIARIO artístico. A Notícia, Curitiba, ano 2, n. 157, p. 3, 10 maio 1906. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/187666/636. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

BENCOSTTA, Marcus Levy Albino. Arquitetura e espaço escolar: reflexões acerca do processo de implantação dos primeiros grupos escolares de Curitiba (1903-1928). Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 18, p. 103-141, 2001. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Marta Maria Chagas de. Reformas da instrução pública. In: LOPES, Eliane Marta Teixeira; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de; VEIGA, Cynthia Greive (org.). 500 anos de educação no Brasil. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. p. 519-550. [ Links ]

CERQUEIRA, Arthur Pedreira de. Contrato assinado com Pedro Rispoli. Curitiba: Departamento do Arquivo Público Paranaense, 1906. AP. 1249, p. 56-57. [ Links ]

CERQUEIRA, Arthur Pedreira de. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Snr. Dr. Bento José Lamenha Lins DD. Secretario do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Publica pelo Dr. Arthur Pedreira de Cerqueira Director Geral da Instrucção Publica em 31 de dezembro de 1907. In: LINS, Bento José Lamenha. Relatorio apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Joaquim Monteiro de Carvalho e Silva, Vice Presidente do Estado do Paraná, pelo bacharel Bento José Lamenha Lins, Secretario d’Estado dos Negocios do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Publica. Curitiba: Typ. d’A República, 1908. Disponível em: https://www.administracao.pr.gov.br/sites/default/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2021-11/ano_1907_mfn_722.pdf. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A escrita da história. Tradução Maria de Lourdes Menezes. Revisão Arno Vogel. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2015. [ Links ]

CLUB de moveis. Diario da Tarde, Curitiba, ano 6, p. 2, 24 abr. 1904. [ Links ]

CÓDICE 818: Registro de chegada de imigrantes ao Paraná – 1891-1895. Curitiba: Departamento do Arquivo Público Paranaense, 1891. [ Links ]

CÓDICE 821: Registro de chegada de imigrantes ao Paraná – 1895-1896. Curitiba: Departamento do Arquivo Público Paranaense, 1895. [ Links ]

CÓDICE 454: Relação de imigrantes que entraram na Hospedaria de Curitiba – 1894-1896. Curitiba: Departamento do Arquivo Público Paranaense, 1894. [ Links ]

COOPERATIVA de carros. O Olho da Rua, Curitiba, ano 1, n. 2, p. 5, 7 set. 1907. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=240818&pesq=&pagfis=297. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

COOPERATIVA de prédios. A República, Curitiba, ano 23, n. 19, 23 jan. 1908. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/215554/20291. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

DIARIO DA TARDE. Curitiba: Celestino Junior, ano. 10, n. 2485, 24 abr. 1907. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/800074/9245. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ESCOLANO BENITO, Agustín. A escola como cultura: experiências, memórias e arqueologia. Tradução e revisão técnica Heloísa Helena Pimenta Rocha e Vera Lucia Gaspar da Silva. Campinas: Alínea, 2017. [ Links ]

GARCIA, Gecia Aline. Itinerário moveleiro: o provimento material escolar para a instrução primária paranaense – anos finais do século XIX e início do século XX. 2020. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2020. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. O fio e os rastros: verdadeiro, falso, fictício. Tradução Rosa Freire d’Aguiar e Eduardo Brandão. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. O nome e o como: troca desigual e mercado historiográfico. In: GINZBURG, Carlo. A micro-história e outros ensaios. Lisboa: Difel; Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 1991. p. 169-178. [ Links ]

GRANDE cooperativa de móveis. A República, Curitiba, ano 23, n. 31, p. 2, 6 fev. 1908. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/215554/20338. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

GRUZINSKI, Serge. As quatro partes do mundo: história de uma mundialização. Belo Horizonte: UFMG; São Paulo: Edusp, 2014. [ Links ]

GRUZINSKI, Serge. Os mundos misturados da monarquia católica e outras connected histories. Topoi, Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 2, p. 175-195, 2001. [ Links ]

LAWN, Martin; RABELO, Rafaela Silva. Um conhecimento complexo: o historiador da educação e as circulações transfronteiriças. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 14, n. 1[34], p. 127-144, 2014. [ Links ]

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e memória. Tradução Bernardo Leitão. 5. ed. Campinas: Unicamp, 2003. [ Links ]

LINS, Adolpho Lamenha. Relatório apresentado à Assembleia Legislativa do Paraná no dia 15 de fevereiro de 1876 pelo Presidente da Província o Excelentissimo Senhor Doutor Adolpho Lamenha Lins. Província do Paraná: Typ. da Viúva Lopes, 1876. Disponível em: https://www.administracao.pr.gov.br/sites/default/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2022-03/relatorio_1876_presidente_adolpho_lamenha_lins_1.pdf. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Reinaldo. Relatorio apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Secretario do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Publica pelo Dr. Reinaldo Machado Director Geral Internio da Instrucção Publica do Estado em 31 de dezembro de 1904. In: LINS, Bento José Lamenha. Relatorio da Secretaria d’Estado dos Negocios do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Publica e annexos. Curitiba: Typ e lith. Impressora Paranaense, 1905. p. 45-69. Disponível em: https://www.administracao.pr.gov.br/sites/default/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2021-11/ano1904mfn699.pdf. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO, Maria Fernanda Campelo. Santa Felicidade, o bairro italiano de Curitiba: um estudo sobre restaurantes, rituais e (re)construção de identidade étnica. Curitiba: SAMP, 2014. (Teses do Museu Paranaense, v. 6). [ Links ]

MARCENARIA Lubrano. A Notícia, Curitiba, ano 2, n. 157, p. 4, 10 maio 1906. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=187666&pesq=&pagfis=634. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MASCHIO, Elaine Cátia Falcade. A escolarização dos imigrantes e de seus descendentes nas colônias italianas de Curitiba, entre táticas e estratégias (1875-1930). 2012. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2012. [ Links ]

MASCHIO, Elaine Cátia Falcade. Imigração italiana e escolarização: da Colônia Alfredo Chaves ao município de Colombo (1882-1917). In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO, 3., 2004, Curitiba. Anais... [S. l.]: Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação, 2004. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YKW2sIVkDWtH4Zm1d9Ac1Bnitbv3ZjRF/view?usp=sharing. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MENESES, Ulpiano Toledo Bezerra de. Memória e cultura material: documentos pessoais no espaço público. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 11, n. 21, p. 89-104, 1998. [ Links ]

MOZAICO do Ensino Civico. Esphynge, Curitiba, ano 3, n. 4, p. 62, set. 1901. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=372811&pesq=&pagfis=258. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MUSEU MAÇÔNICO PARANAENSE. Loja Fraternidade Paranaense nº 0.555. Curitiba: Museu Maçônico Paranaense, [2022a]. Disponível em: http://www.museumaconicoparanaense.com.br/MMPRaiz/LojaPRate1973/0555_Hist_Loja.htm. Acesso em: 17 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MUSEU MAÇÔNICO PARANAENSE. Loja Unione e Fratellanza nº 0.779. Curitiba: Museu Maçônico Paranaense, [2022b]. Disponível em: http://www.museumaconicoparanaense.com.br/MMPRaiz/LojaPRate1973/0555_Hist_Loja.htm. Acesso em: 17 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

NADALIN, Sérgio Odilon. Paraná: ocupação do território, população e migrações. 2. ed. Curitiba: SAMP, 2017. [ Links ]

NAISSANCE: la famille Deyrolle. Paris: deyrolle nature art éducation. [S. l.: s. n.], 2008. Disponível em: https://www.deyrolle.com/histoire/historique-de-la-maison-deyrolle/naissance-la-famille-deyrolle. Acesso em: 23 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

NUNES, Clarice. O “velho” e “bom” ensino secundário: momentos decisivos. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 14, p. 35-60, 2000. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria d’Estado dos Negocios do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Publica. Decreto n. 3 de 18 de outubro de 1892. Manda observar o Regulamento para o Gymnazio Paranaense. A República, Curitiba, ano 7, n. 790, p. 2, 20 out. 1892. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215554&pesq=&pagfis=3217. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria do Interior. Decreto n. 212. A República, Curitiba, ano 19, n. 122, p. 1, 27 maio 1904. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215554&pesq=&pagfis=15674. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria do Interior. Expediente. A República, Curitiba, ano 24, n. 144, p. 1, 22 jun. 1909. Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215554&pesq=&pagfis=22049. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

POLANYI, Karl. A subsistência do homem e ensaios correlatos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2012. [ Links ]

RICOEUR, Paul. Variações de escalas. In: RICOEUR, Paul. A memória, a história, o esquecimento. Campinas: Unicamp, 2018. p. 155-245. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Rafaela Mascarenhas. Histórico da imigração polonesa na região metropolitana de Curitiba. Revista Eletrônica de Ciências Sociais, Juiz de Fora, v. 8, n. 19, p. 52-76, 2015. [ Links ]

ROLDÁN VERA, Eugenia; FUCHS, Eckhardt. Introduction: the transnational in the history of education. In: FUCHS, Eckhardt; ROLDÁN VERA, Eugenia (ed.). The transnational in the history of education: concepts and perspectives. Cham: Palgrave, 2019. p. 1-48. [ Links ]

SILVA, Victor Ferreira do Amaral e. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Secretário do Interior, Justiça e Instrucção Pública pelo Dr. Victor Ferreira do Amaral Diretor Geral da Instrução Pública em 31 de dezembro de 1903. Curitiba: Typ d’A República, 1904. Disponível em: https://www.administracao.pr.gov.br/sites/default/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2021-11/ano_1903_mfn_694.pdf. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Gizele de. Instrução, o talher para o banquete da civilização: cultura escolar dos jardins de infância e grupos escolares do Paraná, 1900-1929. 2004. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2004. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. Templos de civilização: a implantação da escola primária graduada no estado de São Paulo (1890-1910). São Paulo: Unesp, 1998. [ Links ]

SUBRAHMANYAM, Sanjay. A cauda abana o cão: o subimperialismo e o estado da Índia, 1500-1760. In: SUBRAHMANYAM, Sanjay. Comércio e conflito: a presença portuguesa no Golfo de Bengala, 1500-1700. Tradução Elisabete Nunes. Lisboa: Ed. 70, 1994. p. 151-173. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Cynthia Greive. A história da escola como fenômeno econômico: diálogos com história da cultura material, sociologia econômica e história social. In: SILVA, Vera Lucia Gaspar da; SOUZA, Gizele de; CASTRO, César Augusto (org.). Cultura material escolar em perspectiva histórica: escritas e possibilidades. Vitória: UFES, 2018. p. 26-63. [ Links ]

VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. Transnational education in the late nineteenth century: Brazil, France and Portugal connected by a school museum. History of Education, Abingdon, v. 46, n. 2, p. 228-241, 2017. [ Links ]

ZACHARIAS, Mariana Rocha. Espaços e processos educativos do ginásio paranaense: os ambientes especializados e seus artefatos (1904-1949). 2013. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2013a. [ Links ]

ZACHARIAS, Mariana Rocha. Os espaços educativos do Ginásio Paranaense e Escola Normal (1904-1949). In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO, 7., 2013, Cuiabá. Anais... [S. l.]: Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação, 2013b. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/15Q3UqzXxTI3bT3hII4MVTLPMbXgGF-Gt/view?usp=sharing. Acesso em: 7 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

*English version by Viviane Ramos. The authors take full responsibility for the translation of the text, including titles of books/articles and the quotations originally published in Portuguese.

2- The concept of “connected histories” was created by the Indian historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam (1994). According to this author, different spheres of circulation transcend regional, national, or even continental frontiers, allowing us to understand the connections existing in different cultures.

3- Data availability: all set of data that support the results of this study was referenced in the article and are publically available.

4- According to its foundation minute, the Lodge Fraternidade Paranaense was found on April 1897. Among its founders were Affonso Lubrano, Pedro Rispoli, and Victor Ferreira do Amaral (MUSEU MAÇÔNICO PARANAENSE, [2022a]).

5- According to Museu Maçônico Paranaense, the Lodge Unione e Fratellanza was“founded in April 5, 1902 and its demand of filiation and regularization in the Grande Oriente do Brasil –G.O.B. ( a Masonic body) was approved on June 2, 1902 (Bol. G.O.B. – 1902, page. 208). Constitutional letter sent June 2, 1902 (filed in the Lodge Dario Vellozo nº 1.213) and regulated on July 26, 1902 (Livro Atas da Loja Luz Invisível nº 0.749 page. 3 vs)”. Affonso Lubrano was among the founders of this lodge (MUSEU MAÇÔNICO PARANAENSE, [2022b]).

6- In the original : “La vocation de l’enseigne y reste avant tout pédagogique. Outre le matériel scientifique, les pièces de taxidermie et d’ostéologie, le mobilier scolaire et les planches murales fournis à toutes les écoles et universités de France, beaucoup d’ouvrages spécialisés sont publiés par Deyrolle”.

Received: February 05, 2021; Accepted: April 07, 2021

texto em

texto em