Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.49 São Paulo 2023 Epub 27-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202349269782por

THEME SECTION: Youth, Itineraries and Reflexivities

Exploring the renewal of pedagogy: problem-based learning as a space for young peoples’ educational citizenship

Eunice Macedo she is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto (FPCEUP) and a researcher at the Center for Educational Research and Intervention (CIIE). PhD, master and degree in Educational Sciences. Experience in national and international projects in the areas of education with arts, youth citizenship

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1200-6621

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1200-6621

Elsa Guedes Teixeira is a guest assistant at the Higher School of Education of the Polytechnic Institute of Porto (ESE-IPP) and a researcher at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto (FPCEUP). She has a doctorate and master’s degree in Educational Sciences and a degree in Sociology. He has developed research projects in the area of socio-educational inclusion of young people, women and vulnerable groups.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6851-7263

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6851-7263

Alexandra Carvalho was a research fellow for the project EduTransfer (ref. PTDC/CEDEDG/29886/2017).

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0375-1873

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0375-1873

Helena C. Araújo is a Guest Professor at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto (FPCEUP) and a researcher at the Center for Educational Research and Intervention (CIIE). Experience in national and international projects in the areas of Sociology of Education; gender, Women’s history; History of education; Educational policy.

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2988-3209

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2988-3209

1Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

2Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal

This article explores how problem-based learning (PBL) can contribute to renewing pedagogy by placing young people at the center of the pedagogical relationship of knowledge construction, and enabling them to realize their rights. The starting point is the concern about the lack of space for listening to young people in different educational contexts and the recognition of the members of this social group as subjects of the construction of their citizenship. Their voices are crossed with those of teachers and researchers. It is argued that PBL can create space for the young people to enact “educational citizenship”. Grounded on the renewal of pedagogy, PBL constitutes a participatory method based on initiative, decision-making and supportive relationships. Within the scope of the EduTransfer project, and in dialogue with educational citizenship, PBL is seen as a curriculum development process, and a teaching-learning theory and method that can create space for realizing this citizenship. PBL gains a place as a strategy for educational institutions to ensure rights. It is these aspects that we focus on throughout the article, giving rise to a reflection on the different moments of this educational strategy. After focusing on methodological and procedural options, we bring together the voices of teachers, young people and researchers to explore PBL in action. While we assert the value of this approach, we also recognize limits to its implementation.

Keywords Problem-based learning; Educational citizenship; Young people’s voice(s); Itineraries; Reflexivity(ies).

Este artigo explora como a Aprendizagem Baseada na Resolução de Problemas (PBL) pode contribuir para renovar a pedagogia, colocando as e os jovens no centro da relação pedagógica de construção do saber, com realização de direitos. Parte-se da preocupação com a falta de espaço para a escuta das pessoas jovens em diferentes contextos educativos e reconhece-se os membros deste grupo social enquanto sujeitos autores e autoras da construção da sua cidadania. Assim, cruzam-se as suas vozes com as de docentes e investigadoras. Advoga-se que o recurso ao PBL pode criar espaço para o exercício da sua “cidadania educacional”. Tendo por base a renovação da pedagogia, o PBL constitui um método participativo sustentado na iniciativa, na tomada de decisão e numa relação solidária. Ao dialogar com a cidadania educacional, no âmbito do projeto EduTransfer é também central uma visão do PBL como processo de desenvolvimento do currículo, e teoria e método de ensino-aprendizagem que pode criar espaço para a realização dessa cidadania, ganhando lugar como estratégia de garantia de direitos por parte das instituições educativas. São estes aspectos que focamos ao longo do artigo, dando lugar a uma reflexão sobre os diferentes momentos desta estratégia educativa. Depois do foco nas opções metodológicas e processuais, fazemos o cruzamento de vozes docentes, juvenis e de investigação, que exploram o PBL em ação. Assumindo o valor desta abordagem, reconhecem-se também limites à sua implementação.

Palavras-chave Aprendizagem baseada na resolução de problemas; Cidadania educacional; Voz(es) jovens; Itinerários; Reflexividades

Introduction

In this article, we explore how PBL can renew pedagogy, placing young people at the center of the pedagogical relationship of knowledge building with the enactment of rights. Hence, in this article the theoretical-political assumptions of the concept of “educational citizenship” ( MACEDO; ARAÚJO, 2014; MACEDO, 2018) are addressed. This allows an understanding of the combination of education with the exercise of educational citizenship, which crosses the democratic “pedagogic rights” of “participation, inclusion and enhancement” ( BERNSTEIN, 1996, 2000) with the concepts of recognition ( LYNCH; LODGE, 2002), inclusion ( YOUNG, 2000) and interdependence ( LISTER, 1997, 2007). The “educational citizenship of rights” expresses and recognizes the voice of young people in and through school culture, as well as their reflexivity and action in their contexts; in turn, the “educational citizenship of knowledge” focuses on the right to know, participating in the construction and definition of knowledge ( MACEDO, 2018).

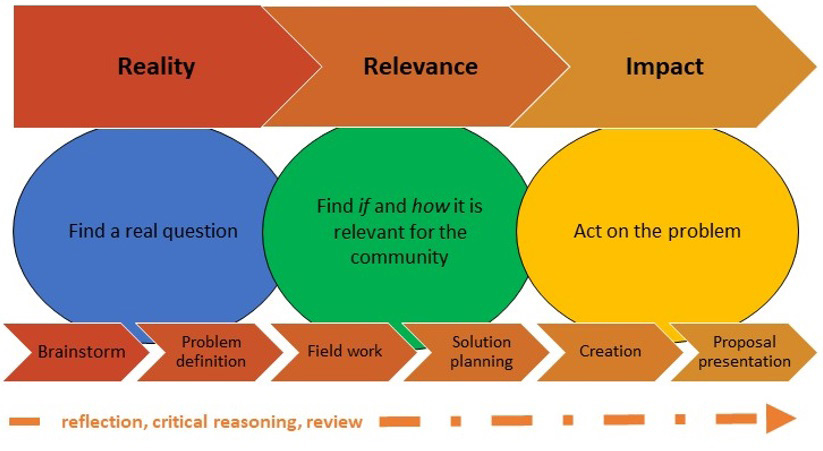

PBL enables collective participation in the construction of knowledge ( FREIRE, 1999) by young people. This method implements a learning intention, based on a “pedagogy of questions” which challenges young people to look for potential solutions. PBL constitutes a three-stage method and space for educational citizenship: focus on “reality,” understanding of “relevance” and creating “impact,” which are completed by “reflexivity.” These stages are embodied in eight complementary steps in a non-linear approach, which we will explore later.

To discuss the possibility of creating space for young people’s educational citizenship and recognizing their voice, in this article, reflective reports from teachers/trainers are analyzed, as are field notes from participant observation of the implementation of PBL in educational contexts, as well as online questionnaires answered by young people. The analysis crosses the voices of teachers and young people and focuses on dimensions of educational citizenship of rights and knowledge, which include: recognition in and through school culture, with “expression and recognition of one’s own voice”; “reflexivity and action on their own contexts”; and sociocultural/relational learning, with “decision making in the construction and definition of knowledge.”

We problematize challenges faced by PBL in guaranteeing these rights, focusing on: power within the class; creating spaces for media/digital literacy and critical reflexivity, and increasing youth participation, motivation and autonomy. Results of the PBL1 evaluation and proposals for change by the educational community are also presented. We reflect on the importance of PBL in reinventing the curriculum and the roles of young people and teachers, with young people being urged to actively participate in the construction of knowledge and decision-making, promoting mobilization for learning; and teachers/trainers assuming a new professional role, as facilitators.

Young people’s educational citizenship: theoretical and political assumptions

Focusing on the ways in which PBL places young people at the center of the pedagogical relationship of knowledge-building in the exercise of rights allows us to understand the links between education and the enactment of educational citizenship — a pedagogical renewal that can provoke participation (initiative, decision-making and supportive relationships).

Institutional systemic responsibilities in guaranteeing rights are recognized in light of the Convention on the Rights of the Child ( UNICEF, 2019, p. [1989]). For Bernstein (1996, 2000), “democratic pedagogical rights” should be guaranteed by the school through pedagogy — a role that is often not fulfilled. Educational citizenship shifts the focus from pedagogy to the subjects —young people ( MACEDO, 2018) — crossing the Bernsteinian proposal of the rights of participation, inclusion and enhancement with demands for recognition ( LYNCH; LODGE, 2002), inclusion ( YOUNG, 2000) and interdependence ( LISTER, 2007), allowing the role of young people in building and claiming rights to be accentuated. As a political right and opportunity ( LYNCH; LODGE, 2002), educational citizenship advocates that young people should be the authors of its construction, based on their voice.

Drawing inspiration from the “voice” of the “feminist epistemological-methodological tradition” ( ARNOT, 2006, p. 406), “voice” represents the history, experience, ways of knowing and getting to know, values and identities, meanings and expectations regarding the world of young people. It gives rise to the assertion of oneself as a “unique being” ( BERNSTEIN, 1996, 2000) and as members of a social group, tainted by intragroup heterogeneity ( YOUNG, 1997). The “expression” and “legitimation” of voice allow the embodiment of “action” ( MACEDO, 2018). This sociological view of voice — the history, experience, views and expectations regarding the world of particular groups — incorporates and goes beyond the view of the National Education Council ( CNE, 2021) about voice as a right of expression and recognition with potential for improving the school, as an organization, its learning processes, and “training of teachers and other educational agents” (p. 82). Thus, in addition to these aspects of a more instrumental vision, evident in school studies which emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1990s, our approach focuses more directly on the exercise of citizenship rights by the citizens who make up this group, taking into account the benefits of their participation to improve their lives and experiences at school and beyond.

Particularly since the 1990s, the exercise of citizenship rights by children and young people has been discussed as legitimate ( ELLIS, 2004; FRANCE, 1998; HALL; WILLIAMSON; COFFEY, 2000; FERREIRA, 2004; NUTBROWN; CLOUGH, 2009). The power of young people to act in the construction of citizenship is assumed, and it is up to the adult world — educational institutions, in particular — to create space for this citizenship construction to happen. As citizens at every moment of their lives, young people have the right to self-narration, participation, decision-making and control of action in solidarity with the world ( MACEDO, 2009a).

In the interweaving of distinct and contradictory contexts, the affirmation of young people’s citizenship can take on contradictory dimensions, in the tension between dependence and independence ( MACEDO, 2018). A “genuine interdependence” ( LISTER, 1997) “in” and “through” pedagogy and in the exercise of citizenship can reduce the conflict between contexts and between individual formulations, facilitating the shared construction of meanings that does not subordinate, but rather expands, the personal construction “mediated by the world” ( FREIRE, 1999).

Emerging from the dialogue between theoretical formulation and listening to voices, “educational citizenship of rights” corresponds to: the development of a feeling of belonging and recognition “in” and “through” school culture; partnership with the adult world through participation in the co-construction, co-maintenance and co-transformation of school life; and realization of individual potential and beyond, through interaction. In turn, “educational citizenship of knowledge” develops the right to participation ( BERNSTEIN, 1996), focusing on the right to knowledge, with participation in its construction and definition. Inclusion, recognition and interdependence are conditions for pedagogy as a space for exercising rights centered on subjects, their relationships, and knowledge. Educational citizenship is manifested in a back-and-forth between the creation of spaces by institutions and young people action in seizing these spaces to exercise citizenship. It implies attention by institutions to valuing and claiming rights, including the definition and construction of knowledge. This means being heard and recognized and being able to reflect and act in life contexts. It is this space that the curriculum with PBL can create, meaning that each young person is called to school “to collectively participate in the construction of knowledge that goes beyond knowledge based on pure experience, [knowledge] that takes into account their needs and makes them an instrument of struggle, enabling them to become the subjects of their own history” ( FREIRE, 1999, p. 16).

PBL can be traced back to the 1960s, as university’s adaptation to the intensification of the technologization of medicine and the expansion of healthcare ( AYALA; KOCH; MESSING, 2019) or to the 1970s ( CHECKLEY, 1997), situating the history of the method in the Socratic dialectical question-answer approach, in the Hegelian dialectic, or in the Dewey approach ( RHEM, 1998). 3 Vasconcelos and Almeida ( 2012, p. 4) associate this method with “Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.” This view is reinforced and associated with collaborative learning theories by Skinner, Braunack-Mayer and Winning (2015) regarding the role of the group. In the field of educational sciences, Cosme (2018) refers to PBL as an instrument that can encourage teachers to seize the curriculum in an engaged and innovative way, within the scope of curricular autonomy and flexibility ( PORTUGAL, 2018). Autonomy is to be understood as a fluid process, under construction and maturation based on experiences “stimulating decision and responsibility, […] respectful of freedom” ( FREIRE, 1997, p. 120–121).

Research on PBL has focused on: theory, with student reports as a starting point for learning; cognition and language, knowledge construction and negotiation of meanings; and relationships between student interactions and learning outcomes ( AYALA; KOCH; MESSING, 2019), with a gap regarding the activities and relational dynamics of group learning. In PBL, students work together on a problem (cause or question), organize ideas, collect information, define the nature of the problem and their learning goals, and propose forms of action ( AYALA; MESSING; TORO, 2011). However, as is emphasized, the main objective of PBL is not to solve the problem, but to implement a learning intention. PBL is an excuse to learn in a different way, bringing new dimensions to the relational construction of knowledge. Holen (2000) refers to the importance of social life in guiding learning — guidance that is learning in itself and not just context. As he also mentions, it is important for students to work together for a significant period of time that allows them to develop specific ways of relating within the team, ensuring the added value of PBL in relation to conventional methods. Vasconcelos and Almeida (2012) assume that the mediation of learning by the teaching staff is crucial to the success of this methodology. We explore these aspects around educational citizenship.

PBL allows young people to question and rethink their place as students in the authorship of knowledge and the construction of themselves as subjects. It abandons transmissive pedagogy — the pedagogy of response, which deposits finished knowledge in passive and receptive students; it focuses on the “pedagogy of the question” of consciousness ( FREIRE; FAUNDEZ, 1998); this “liberating pedagogy” allows young people’s enactment of educational citizenship; and it challenges young people to look for answers to poorly defined problems and accentuates the social dimension of learning, uncovering power relations. This attention to power inequalities implies ensuring space for all voices to speak out, preventing only “powerful voices” ( MACEDO, 2009a, 2009b) that are confident and familiar with school culture, from being reinforced. As a “pedagogy of question,” PBL focuses on building complicities between powers and building knowledge “with” young voices.

Vasconcelos and Almeida (2012) highlight the value of focusing on research — planning and executing a set of activities — which allows for a broader understanding of science and its construction. Furthermore, they affirm that the centrality of students that results from the creation of “everyday scenarios” that stimulate the exploration of equally stimulating questions through the expansion of knowledge is an advantage, as Barrows and colleagues mentioned in the 1970s ( CHECKLEY, 1997).

Doing and investigating what you do ( FREIRE, 2018 [1968]) allows PBL to be identified as a relational way of developing the curriculum, embedded in a complexity of linkages, which create a place for the school “as a center for the systematic production of knowledge, [… ] critically work on the intelligibility of things and facts and their communicability” ( FREIRE, 1997, p. 140). Concretely,

[…] a critical-dialogic pedagogy […] the critical apprehension of significant knowledge through the dialogic relationship. [...] where the construction of collective knowledge is proposed, combining popular knowledge and critical, scientific knowledge, mediated by experiences in the world.

This is about assuming that the quality of a school should not be measured exclusively by the educational success of students ( NADA, 2020), but rather by the construction of a relevant and meaningful learning environment ( BERNSTEIN, 1996 , 2000) MAGEN-NAGAR; SHACHAR, 2017 apud ( AYALA; KOCH; MESSING, 2019).

PBL as a method and space for educational citizenship

In methodological terms, a qualitative “interpretiviste” approach was adopted, emphasizing the multiple interpretation, interpellation and intersubjectivity in the production, collection and analysis of data ( MACEDO, 2018). The article analyzes the implementation of PBL, initially in person, and later online — through Teams — due to the confinement caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, which made the digital re-creation of the methodology possible. A training workshop on PBL was held with 25 teachers for a total of 36 hours, including 18 for implementing the PBL0 and sharing the implementation processes and results with colleagues. Reflective reports were prepared. Twenty-five online sessions were held with three tenth-grade classes (one from a vocational school and two from an upper secondary school). As predicted by this methodology, in the upper secondary school, PBL1 culminated in the presentation of the processes and solutions to the community (online) and the dissemination on the website of the school cluster; in the vocational school it involved the class community and their teachers. Twenty students responded to an online evaluation questionnaire that included a checklist for evaluating the skills developed, based on the Profile of Students Leaving Compulsory Schooling ( DIREÇÃO-GERAL DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2017). To cross the “polyphonies of voices” ( ARAÚJO, 2007), this article is based on (PBL0) teachers’ reflective reports, field notes from participant observation by researchers, and young people’s assessments expressed in the online questionnaire. In total, 22 professionals (teachers and trainers) and 75 young people (three tenth-grade classes) participated. The data was subject to content analysis (NVivo 1.4.1).

PBL, nonlinear complementarity approach: three stages, eight steps

In terms of the enactment of educational citizenship of rights and knowledge, PBL must recognize young voices, skills and knowledge, decision-making on how to understand the problem and what is (and is not) relevant to know, as crucial conditions for their authorship in the construction of citizenship.

As a relational way of developing the curriculum and a pretext for young people’s construction, PBL foresees a set of complementary stages and procedures that is essential to comply with, adapting the implementation to concrete subjects in concrete situations and taking advantage of their voice and the specificity of the context. With several possible appropriations, Figure 1 presents three stages of the method.

Source: Adapted from ( METHOD of authentic instruction: problem-based learning (n/d).).

Figure 1 - PBL in three stages “with” reflexivity

The dialogue with teachers 4 in training allowed us to introduce the transversal dimension of reflexivity, critical reasoning and review into the scheme, which feeds back into the development of knowledge and the construction of young people as authors of their educational citizenship, in line with investigative intervention, at the heart of the current reflection.

To start with, we seek to focus on “Reality” around a real or “authentic” problem-cause-question ( STEPIEN; GALLAGHER, 1993), whose identification and definition emerges from a brainstorm. Understanding and defining the problem, which follows, requires in-depth study, which should allow us to understand the “Relevance” of the problem-cause-question for the community. Working on significant problems-causes-questions that are relevant for the community, including young people as researchers, facilitates the construction of knowledge about this reality, fostering greater commitment. Serious fieldwork, in a team-individual-team/class back-and-forth, is aimed at finding solutions for personal/team action on the problem; these solutions will be all the more appropriate as the process of understanding and defining the problem is rigorous. This action can create “Impact”. Dialogue with the wider local community constitutes a recognition of the itineraries carried out and the findings, and new questions may emerge.

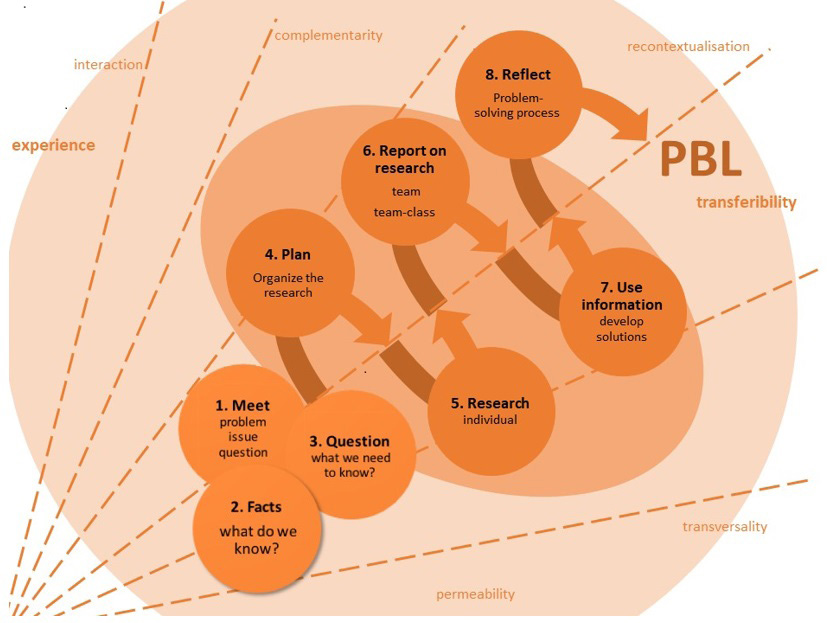

If there are guidelines, young people’s centrality must be encouraged in teams and in the class, and regulatory tendencies that mitigate autonomy must be avoided, as they reduce it to procedures and the management of relationships between peers. As Figure 2 illustrates, there is an almost “natural” sequence at the start of the investigative process (1, 2, 3), steps 4, 5, 6 can be developed several times back and forth and others take on a more transversal character (7, 8). There may also be overlapping and retaking of steps already taken, in the face of challenges emerging from experience, in an approach that is permeable to the field and to the subjects of the implementation.

Source: Macedo (2022), based on University of Rochester (2009).

Figure 2 - PBL: proposal of the project EduTransfer

In step 1, to “know the problem-cause-question” the starting idea is intentionally poorly defined, leaving space for thorough investigation based on young voices. In step 2, in the class team, given “what we already know” or what we think we know, it is important to determine the distinction between facts and opinions, checking the sources and their legitimacy. In step 3, we start “questioning what we need to know” about the problem-cause-question, its causes, people and entities involved, etc. In teams and given their interests/knowledge/skills, step 4 is about “planning the organization of the research” in dialogical decision-making. This plan may contain questions such as: where/how/when/with whom can we find information? Step 5, in view of the team’s plan, involves “individual research” in the construction of one’s own knowledge, with online or/and consultation of documents and studies, on-site visits, photographic records, interviews, listening to audios, viewing videos, and/or others thought up by students and repeated as many times as necessary, for personal systematization. This is shared with the team in step 6, which consists of “reporting on the research” to the team and then to the class team, in a relationship of “co-laboration”. Processes and results are discussed and new questions are asked. In step 7, there is a need to use information to develop “solutions,” with incorporation in the “final product” This “product” — the proposed solution — has a conceptual basis and does not have to correspond to a material construction, which would bring PBL closer to project-based learning. “Reflect on the problem-solving process” (step 8) incorporates discussion, throughout the process, within and between teams to assess procedures and findings, and readjust “solutions,” and reaches its climax in the presentation to the community. In a subsequent PBL, the solutions found may become new problems… “how could this solution be implemented?”.

Assessment in PBL has been the subject of controversy in the tension between evaluating and not evaluating, and what to evaluate. The option for formative evaluation throughout the process, as an opportunity for learning, is the most appropriate as it provides feedback on the process itself and on the resulting learning.

Professional, young and research voices in the co-construction of spaces for educational citizenship

In the analysis of reflective reports and field notes on the implementation of PBL, in educational contexts in which young people, teachers and researchers co-constructed spaces for affirming educational citizenship, we focus on young people’s rights of “inclusion” — belonging and recognition “by” and “in” school culture; “participation” — partnership in the co-construction, co-maintenance and co-transformation of school life and “enhancement” — realizing the potential of each young person and beyond. Meanings are sought for the experiences of bringing young people closer to citizenship, creating dialogues. As the materials are categorized by units of meaning, in a direct relationship with the rights under debate, the interdependence between rights is recognized.

Appraisal “in” and “through” school culture: expression and recognition of one’s own voice

One student stated that the team considers there is benefit in exploring the theme “extra support for students”, referring to a dialogue in which the expression of the heterogeneity of voices led to decision-making. This makes it possible to give visibility to the polyphony of voices in the team and the negotiation in solving problems: “We carried out an analysis and, as a group, we were able to draw different conclusions so that we could do a good job in the future” (Miguel, Field Note (FN), ES1, 19.05.2020).

In the “search for a solution”, an intermediate step of PBL, one young man emphasizes the need to define institutional support strategies for students, a search for a solution, as an intermediate step of PBL, saying: “[…] how could we implement it in the day the daily life of each student to improve their academic career?” (Miguel, FN, USS1, 19.05.2020).

In a five-way conversation, in which opinions and doubts are discussed, models of vertical leadership are reproduced, as they were learned in a more conventional educational approach, leading to the need for clarification: “We don’t have our leader!” (Ana, FN, USS1, 19.05.2020). The mistake allowed it to be made clear that leadership in PBL does not belong to a specific individual, but focuses on a form of shared leadership.

Showing a concern with participation, teachers highlighted the right of young people to be heard, as an enabler of autonomy in learning and the strengthening of a culture of proximity between young people and teachers:

Despite being challenging, I enjoyed just sitting with them [young people], listening to their reasons, recognizing new abilities and skills that had not been revealed until then [...]. Walking alongside them, and not in front of them, gave me time to see them in other roles, different from the usual, confirming that in new situations they reveal themselves to be different students.

(Mariana, teacher, ES2).

Observation of the teams showed that young people have things to say about the conditions that affect their lives, demanding to be “heard” and “recognized” as partners — assuming the right to participate.

Addressing real problems as citizens: young people’s reflexivity and action in their contexts

Highlighting the diversity of voices, among the problems-causes-questions identified by the groups in the educational institutions involved in the project, examples arise that range from concern about the lack of garbage bins in the city, to the search for building sustainable houses and classrooms, looking for a more ergonomic machine that facilitates the 3D design of metal equipment, investing in bitcoin, explaining the concept of family and new families, and facing the overload of curricular content; problems for which the groups undertook research and proposed solutions.

In a PBL session, a team explored the topic that the class team called “curricular content overload.”

One young woman states that in education, there is a focus on the quantity of content studied and not on the quality of learning and on understanding of the contents. She also states that at school “they appeal to a future worker.”

(FN, ES1, 12.05.20201).

Regarding the educational process, the importance of reinforcing citizenship being linked to real circumstances is stated: “The fact that this methodology requires students to work on a real problem, which specifically […] concerned their lives, contributed to the transformation of their civic practices” (José, teacher, ES2).

The debate between young people allows us to infer their ability to reflect on their contexts, as an exercise of educational citizenship, at the intersection with one of the fundamental steps of PBL — the distinction between facts and opinions (FN4). It also makes it possible to highlight the intersection between rights.

Still taking into account the dimension of “reflexivity and action in the contexts of life”, action is considered to be both taking the opportunity to speak and the solutions that young people construct for the problems defined. During the observation, it was possible to register young people’s reflexivity about the “job of student” and of teaching, anticipating “other” professional role. This was the case of one of the teams that focused on the pedagogical relationship. Having not identified concrete solutions, the young people gave their opinions and, together, asked questions about interaction and stimulation for learning and evaluation:

— Dynamism [in the classroom], how does it influence the school community? – says one of the colleagues.

— If there is no dynamism, there is not as much attention or knowledge acquisition.

— It makes the teacher’s job easier.

(FN, ES1, 26.05.2020).

The young woman raises yet another question, keeping her leading role in the debate:

— What were the main changes with distance learning?

— Very different [online]. Students’ concentration interferes... they become more distracted.

— More boring for students. There are teachers who don’t turn on the camera and just talk.

— Assessments. There are no tests and it is more complicated to evaluate.

— It’s different when it comes to monitoring, because we’re not with the teachers.

— The exercises are the tests… it allows for more copying [from others]. The teacher has no idea who is working.

(FN, ES1, 26.05.2020).

Taking this excerpt from the debate as an example, it is worth noting that at various times young people seem to take up the voices of teachers, expressing them as their own. This aspect reveals the interpellation and interdependence in the educational process. As mentioned above, it is about the assumption of “powerful voices” in presence, in this case, the voices of teachers. On the other hand, for teachers, young people’s participation and involvement in “reflection and action”, within the scope of solving identified problems, is enhanced in PBL by the development of skills, such as awareness of current issues:

The students got involved in all the tasks, producing very appealing materials that caught their own attention and that of the rest of the community. One of the aspects to highlight is the growth in students in the capacity for autonomy that went from an almost total lack of knowledge of human rights and their implications [...] to a knowledge that, in the end, allowed them to almost dispense with direct intervention of teachers. This was due to the fact that this methodology allows you to exercise your freedom and make choices [...], that is, to take responsibility for them.

(José, teacher, ES2).

Sociocultural and relational learning with decision-making in the construction and definition of knowledge

With regard to participation in the construction and definition of knowledge, not only is the content explored of interest, but also the instruments employed by young people. Also of interest are the sociocultural and relational learning processes that the construction of knowledge involves, particularly in decision-making in teams and with teachers. This view is based on an idea disseminated by UNESCO (1998) about the “four ways of knowing” or “pillars of knowledge”: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be. It is along these lines and taking the processes implemented into account, that we affirm the holistic nature of learning and the construction of knowledge, “given that there are multiple points of contact, relationship and exchange between them” (p. 90).

The construction of knowledge is evidenced through the re-signification of previous learning. The combination of a pedagogical relationship based on questions and lived experiences, as well as the interaction of different modules of the study plan, seem to point to “the refusal of specialized spheres” of learning. The project proposal, in a professional school, whose curriculum is assumed as interdisciplinary, was combined with PBL, enhancing the reaffirmation of the school’s role in the transversal construction of knowledge. This includes learning how to live side by side with other people, wherever they come from ( DELORS, 2013). Teachers and students were challenged to play different roles, allowing openness to change and improvement in teaching-learning, with an increase in young people’s media and digital literacy.

The dynamic of the session was based on a question-centered pedagogy, in which the teacher, deductively and resuming previous learning experiences, uses the voices of young people to revisit content already explored. The systematic use of questions and memories of images, architects, buildings, among other concepts and ideas that they had seen together, generated a climate of construction of ideas that informed the research of the PBL teams. A young man told the teacher: “It could replace other subjects!” The teacher responded: “All subjects are important. Knowledge is transversal.”

(FN, VS, 21.05.2020).

The teachers’ comments allowed emphasis on the place of PBL as a space for educational citizenship but did not fail to mention the difficulties experienced in implementation, namely, the pressure to comply with the subject’s syllabus and the preparation for national exams, as limitations on young people’s participation in the construction and definition of knowledge. On the other hand, there is evidence of the assumption of an “other” professional role with a loss of the teacher’s centrality in teaching-learning, which stimulates teacher change towards becoming a facilitator of learning:

Sometimes, I was called upon to support decisions, forcing me to omit my personal opinion, and directing them only to questions that would help them understand, for themselves, the best path. This ability not to form judgments or not to share too much information was not at all easy, it led me to take on a much more reserved, even discreet, stance. The center of learning was not conveyed by me, but in a very indirect way, only mediated and induced by the dynamics of the method in itself.

(Mariana, teacher, ES2).

Challenges to ensuring educational citizenship rights: three dimensions

PBL can constitute a space for the construction of young people’s educational citizenship in three dimensions. It can give rise to: i) the “expression and recognition of their voices”, ii) the “reflection and action of young people on their own life contexts”, and iii) the “participation in the construction and definition of knowledge”. However, PBL also poses challenges to the guarantee of educational citizenship rights within these dimensions of which we provide warning by bringing the voices of protagonists to the fore and dialoguing with them in direct speech.

Power relations among voices: challenge identified in the first dimension — “expression and recognition of the voice of young people”

We have already stated positive aspects such as promotion of the heterogeneity of voices, negotiation in solving problems, shared leadership, being heard as a promoter of autonomy in learning, and the culture of proximity between teachers and young people at school, and claiming the right to participate. However, in the teachers’ reflective reports, they highlight issues of power within the class, such as leadership relationships in which the powerful voices of young people who feel at home in the school culture are asserted ( MACEDO, 2009a, 2009b). This can reduce the expression of other voices and the lack of recognition of other views of the world by some young people, in a hierarchical dualization between powerful and powerless voices; situations arise of passivity in classes and teamwork that may relate to less adherence to the method, relationships between peers, unique living conditions or other aspects.

In this line of concern, teachers state that PBL led to questioning this type of interaction and to the awareness of the need to promote respect, “tolerance” and acceptance of the diverse voices. Although the pattern of apparent lack of recognition from the more conventional class seems to be repeated especially in the initial PBL sessions, these allow the expression of other voices, previously silenced in two distinct and sometimes complementary ways: self-silencing as a conflict management strategy, due to a lack of investment in social relationships or other issues; and/or voices silenced by others within the framework of differential power relations among peers or deriving from adult regulation ( MACEDO, 2018):

In certain teams the imbalance of skills was very significant; in others, several students wanted to take the lead because they were committed and considered that their opinion or idea was “more” valid, because they are generally recognized as a “good student” and therefore should be followed. [...] Some who were more discreet in class realized that in this experience their voice was very valid and were no longer afraid to participate; others adopted a posture of submission and followed the leader’s instructions.

(Iva, teacher, VS2).

The non-distinction between facts and opinions and digital literacy: challenge identified in the second dimension — “reflection and action on their life contexts”

As for the second dimension, we have already argued that PBL allows young people to claim space for self-realization as students and citizens, and to reflect critically on the educational process, linking learning to real-life problems that make sense to them. This implies transformation of the educational experience as a practice of citizenship, including awareness of current problems, and contributes to the distinction between facts and opinions. Still, some young people revealed some difficulty in making this distinction, especially regarding information found on the internet. This indicates the need to create more spaces for young people’s “digital literacy” ( OECD, 2019) — even more so at a time of widespread expansion of digitalization in pedagogical contexts. It also implies greater investment by the school in the construction of young people’s reflexivity(ies), both as a place to express their voices.

Lack of inclusion of groups in more fragile positions: challenge identified in the third dimension — “participation in the construction and definition of knowledge”

In the third dimension, we emphasized that PBL promotes participation, encouraging decision-making as a team and with teachers, focusing on a pedagogy of questioning and opening the way for a new teaching professional role. However, according to teachers, some students who already showed lack of motivation in general classes also revealed this in PBL. Teachers highlighted difficulties that were sometimes overcome by a limited number of young people, concerning the assumption of individualism, insecurity, lack of participation and critical reflexivity and/or autonomy, as well as time management. In these cases, PBL may not have produced the desirable mobilizing effect, or the young group may not have yet acquired the necessary empowerment for potential exposure to criticism, as they are often the object of stigmatization. This is due to the negative social representation of vocational courses and of the people who attend them. As Mariana (teacher, USS2) states:

It was difficult to overcome the resistance they expressed in presenting and exposing their ideas and proposals to other students outside their class. Winning over a small group of brave people for the first session resulted in a change in their predisposition for the following meetings.

Seeming to maintain and reproduce the negative view of a vocational course in an upper secondary school, the same teacher portrays as an “inferiority complex” what we could assume as the inculcation of stigma and devaluation of these students, including by teachers:

The latent inferiority complex in these students, from an academic point of view, constrains their posture and interaction with other classmates at school, making them averse to relationships outside their course. Despite this attitude of generalized inertia, the students carried the project to the end, came up with solutions, presented their proposals and were even able to support their colleagues from the other class, in a beautiful sharing of technological skills that they were able to demonstrate to their peers.

(Mariana, teacher, ES2).

It can be admitted that this culture of devaluation can lead young people to deny themselves, mitigating their educational citizenship, and recognizing themselves as minor, as objects — in dehumanization ( FREIRE, 1999). However, the open dialogue among young people allowed a raising of awareness. This is a very relevant research experience. In this framework of recognition, a young man from general education, with the agreement of others, asserted himself against this dehumanization: “Everyone looks at a vocational course and thinks, no offense, they are the stupid ones”, and a young woman continued, still deconstructing prejudices about the vocational course, stating: “From what I know about programming, it’s not exactly a simple thing!”.

PBL has an inclusive potential that needs to be worked on to counter socialization modalities established in contexts that reproduce cognitivist views of knowledge and legitimize social inequalities — illegitimately. If precautions are not taken in the pedagogical relationship of knowledge construction, it should be admitted that PBL can reinforce exclusion mechanisms with regard to the reproduction of inequalities in participation, with the reinforcement of “powerful voices” and the silencing of “other” voices. There is a need for strategies to combat exclusion and promote inclusion from the outset. This is evident in the constitution of heterogeneous teams that value the knowledge in presence, and in systematic dialogical reflexivity in the class-team, and in each team that constitutes it, about the importance of listening, valuing and of a collaborative work that creates space for “self-realization” on the part of each subject involved. This process may result in the construction of a sense of belonging, in which this self-realization goes beyond individual potential, to be expanded with the team. This concern is expressed below:

In the final presentation, one of the students used “I” instead of “we”. This fact leads me to question the way groups should be structured, because when they are created by students, they end up choosing the colleagues who are closer to them and less integrated students are excluded, no doubt.

(Ariana, teacher, VS2).

In the feedback regarding the implementation of PBL, the majority of young respondents stated that PBL met their expectations. The aspects related to educational citizenship that were evaluated most positively were learning team cooperation, namely, expressing ideas and opinions, without “fear”; greater interaction between teachers and students; and participation in the construction and definition of knowledge. A student mentioned that “the implementation of PBL is something that helped us develop our abilities to think, research a certain subject and criticize it (although we still need to improve)” (Student 1, ES1).

With regard to proposals for change in future PBL processes, young people expressed a preference for the face-to-face format: “I would like more practical work than theoretical work, in the sense of taking to the streets and working more with society” (Student 2, ES1); the need for more training on PBL, more time to delve deeper into the issues, and greater support in implementing the steps.

To finish...

PBL allows for the active reinvention of the curriculum and is particularly relevant in themes related to citizenship. In this process of curricular innovation with flexibility and autonomy, the roles of teachers and young people are reinvented in the construction of a participatory pedagogy which seeks to divert the power of professionals to young people, encouraging the construction and expression of their voice.

Recontextualization, which adapts PBL to specific educational institutions and to teachers and young people with diversity and specificity, is fundamental. It is to this extent that PBL can offer space for “educational citizenship of rights” with voice and recognition, decision-making and reflexivity in regards to the life and reality of each person as an individual and member of a specific social group. PBL can also create a place for the “educational citizenship of knowledge”, in which young people decide what is relevant to learn and how they should proceed to build their own knowledge.

According to the results of this qualitative interpretiviste study ( MACEDO, 2018), PBL mobilized young people to learn and contributed to their participation. Emphasis is placed on the construction of heterogeneous teams, systematic reflection in each team on the importance of collaborative work and valuing the best in each person; and the increase in the number of PBL training sessions. More time to delve deeper into the problems-causes-issues, greater support from teachers and the research team to implement the PBL stages, identify, (re)define the initial problems-causes-issues and distinguish between facts and opinions were also considered essential for the relational construction of meanings.

An aspect of enormous relevance, with implications for the pedagogical-relational relationship of knowledge construction, was the expectation that young people in complementary work teams would take the lead in understanding and resolving problems-causes-issues. Another dimension to emphasize was the challenge to teachers to rethink their professional roles, moving away from the role of transmitters of “finished” knowledge. This transmissive role, supported by regulatory procedures, allows teachers to remain in control of the learning situation, defining rhythms, topics and other guidelines, and removing the power to control from young people.

With PBL, professionals can take a step back and take advantage of previous experience to develop knowledge, which allows them to position themselves as learning facilitators. More than giving clear directions for the construction of knowledge by young people, PBL makes it possible for the emergence of the voices of the young people who make up the teams. This means that professionals, possessing specific knowledge, can and should share it as members of the class team, supporting decision-making and young people’s itineraries. Such a professional stance can create the space that Bernstein (1996, 2000) demands of the school as an institution, to guarantee “democratic pedagogical rights” through pedagogy. This would allow the combination of recognition of rights by the school and the exercise of rights by young people as subjects of this pedagogy, within the framework of educational citizenship. By implying the recognition of young learners as holders of knowledge and perspectives, PBL expands the place of young people’s participation in the definition and construction of knowledge, as an axis for achieving educational citizenship “with” voice.

Furthermore, by resorting to poorly structured problems-causes-issues, PBL had two implications in particular, resulting from little prior definition: it stimulated the development of the problem-cause-issue with exploration of its contours, dimensions, implications, entities and people involved, related actions, etc.; and created space for young people to carry out diverse exploratory itineraries, questioning meanings, a process that allowed the development of multiple solutions, in a growing complexity of the problem-cause-issue itself. The increasingly thorough mastery of new information provoked new questions, contributing to the construction of more elaborate thinking, guided by reflexivity.

In short, while not being a panacea for all the problems that affect the pedagogical relationship of the construction of knowledge in context and with specific people, as a theory and teaching-learning method, PBL fosters the renewal of pedagogy and encourages the enactment of young people’s educational citizenship.

Even when carried out online, PBL is also a crucial vessel for data collection as it allows the observation of young people participation, with interaction, listening, initiative, reflexivity and decision-making, and regarding intra and inter-team relationships as well as the ways to explore and construct knowledge. PBL can therefore consist of a space-time in which “no one educates anyone, no one educates themselves, […] [people] educate each other, mediated by the world”, as Freire ( 1981, p. 79) already asserted.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO, Helena Costa. Cidadania na sua polifonia: Debates nos estudos de educação feministas. Educação, Sociedade & Culturas, Porto, v. 25, p. 83-116. 2007. [ Links ]

ARNOT, Madeleine. Gender voices in the classroom. In: SKELTON, Christine; FRANCIS, Becky; SMULYAN, Lisa (ed.). The Sage handbook of gender and education. London: Sage, 2006. p. 407-421. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607996 [ Links ]

AYALA, Ricardo; KOCH, Tomas; MESSING, Helga. Understanding the prospect of success in professional training: an ethnography into the assessment of problem based learning. Ethnography and Education, London, v. 14, n. 1, p. 65-83. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2017.1388184 [ Links ]

AYALA-VALENZUELA, Ricardo; MESSING-GRUBE, Helga; TORO-ARÉVALO, Sergio. The didactic sense of “problem-based learning” in medical education. Revista Cubana de Educación Médica Superior, La Habana, v. 25, n. 3, p. 344-351. 2011. Disponível em: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumenI.cgi?IDARTICULO=31776 Acesso em: 22 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

BERNSTEIN, Basil. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research and critique. Bristol: Taylor & Francis, 1996. [ Links ]

BERNSTEIN, Basil. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research and critique. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000. [ Links ]

CHECKLEY, Kathy. Problem-based learning: the search for solutions to life’s messy problems. Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1997. [ Links ]

CNE. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Recomendação n.º 2/2021. A voz das crianças e dos jovens na educação escolar. Diário da República, n. 135, 2.ª série, p. 75-84, 2021. [ Links ]

COSME, Ariana. Autonomia e flexibilidade curricular: propostas estratégias de ação-ensino básico e ensino secundário. Porto: Porto Editora, 2018. [ Links ]

DELORS, Jacques. The treasure within: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be. What is the value of that treasure 15 years after its publication? International Review of Education, New York, v. 59, p. 319-330. 2013. [ Links ]

DIREÇÃO-GERAL DA EDUCAÇÃO. Perfil dos alunos à saída da escolaridade obrigatória. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação. 2017. [ Links ]

ELLIS, Sonja J. Young people and political action: who is taking responsibility for positive social change? Journal of Youth Studies, London, v. 7, n. 1, p. 89-102. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626042000209976 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Manuela. “A gente gosta é de brincar com os outros meninos!” Relações sociais entre crianças num jardim de infância. Porto: Afrontamento, 2004. [ Links ]

FRANCE, Alan. “Why should we care?”: Young people, citizenship and questions of social responsibility. Journal of Youth Studies, London, v. 1, n. 1, p. 97-111. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.1998.10592997 [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. A educação na cidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 1999. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. 5. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1997. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1981. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. Porto: Afrontamento, 2018 [1968]. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo; FAUNDEZ, Antonio. Por uma pedagogia da pergunta. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1998. [ Links ]

HALL, Tom; WILLIAMSON, Howard; COFFEY, Amanda. Young people, citizenship and the third way: a role for the youth service? Journal of Youth Studies, London, v. 3, n. 4, p. 461-472. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/713684383 [ Links ]

HOLEN, Are. The PBL group: self-reflections and feedback for improved learning and growth. Medical Teacher, London, v. 22, n. 5, p. 485-488. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590050110768 [ Links ]

LISTER, Ruth. Citizenship: feminist perspectives. New York: New York University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

LISTER, Ruth. Inclusive citizenship: realizing the potential. Citizenship Studies, London, v. 11, n. 1, p. 49-61. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020601099856 [ Links ]

LYNCH, Kathleen; LODGE, Anne. Equality and power in schools: redistribution, recognition, and representation. London; New York: Routledge, 2002. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Eunice. Cidadania em confronto: educação de jovens elites em tempo de globalização. Porto: LivPsic & CIIE, 2009a. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Eunice. Vozes jovens entre experiência e desejo: cidadania educacional e outras construções. Porto: Afrontamento. 2018. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Eunice. Vozes poderosas de jovens de elites económicas portuguesas. Configurações, Braga, v. 5-6, p. 175-197. 2009b. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Eunice; ARAÚJO, Helena Costa. Young Portuguese construction of educational citizenship: commitments and conflicts in semi-disadvantaged secondary schools. Journal of Youth Studies, London, v. 17, n. 3, p. 343-359. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.825707 [ Links ]

MACEDO, Eunice (coord.). Recomendações e implicações políticas: do cumprimento da tarefa à apropriação do conhecimento e da democracia: transferibilidade de práticas promissoras na aprendizagem através de diferentes contextos. Porto: CIIE_FPCEUP, 2022. Disponível em: https://edutransfer.fpce.up.pt/wp-content/uploads/sites/761/2022/04/01_Recomendacoes-politicas-EduTransfer.pdf Acesso em: 22 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

METHOD of authentic instruction: problem-based learning. In: Jen Welch [página web]. S. D. Disponível em: https://jenwelchmedhigheredportfolio.weebly.com/authentic-instruction.html . Acesso em: 3 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

NADA, Cosmin et al. Can mainstream and alternative education learn from each other? An analysis of measures against school dropout and early school leaving in Portugal. Educational Review, Birmingham, v. 72, n. 3, p. 365-385. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1508127 [ Links ]

NUTBROWN, Cathy; CLOUGH, Peter. Citizenship and inclusion in the early years: under-standing and responding to children’s perspectives on “belonging”. International Journal of Early Years Education, London, v. 17, n. 3, p. 191-206. 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669760903424523 [ Links ]

OECD. OECD future of education and skills 2030: conceptual learning framework. Core foundations for 2030. Paris: OECD, 2019. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 55/2018, de 6 de julho. Estabelece o currículo dos ensinos básico e secundário e os princípios orientadores da avaliação das aprendizagens. Diário da República, Lisboa, n. 129/2018, Série I, 2018. Disponível em: https://data.dre.pt/eli/dec-lei/55/2018/07/06/p/dre/pt/html Acesso em: 22 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

RHEM, James. Problem based learning: an introduction. The National Teaching & Learning Forum, USA, v. 8, n. 1, p. 1-4. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1002/ntlf.10043 [ Links ]

SKINNER, Vicki J.; BRAUNACK-MAYER, Annette; WINNING, Tracey A. The purpose and value for students of PBL groups for learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, Indiana, v. 9, n. 1. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1499 [ Links ]

STEPIEN, William; GALLAGHER, Shelagh. Problem-based learning: as authentic as it gets. Educational Learning, Illinois, v. 50, n. 7, p. 25-28. 1993. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura. Educação: um tesouro a descobrir: relatório para a Unesco da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o século XXI. Paris: Unesco, 1998. [ Links ]

UNICEF. Convenção sobre os direitos da criança e protocolos facultativos. Lisboa: Comité Português para a Unicef, 2019 [1989]. [ Links ]

UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER. Problem based learning: main concepts. New York: University of Rochester. 2009. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, Clara; ALMEIDA, António. Aprendizagem baseada na resolução de problemas no ensino das ciências: propostas de trabalho para ciências naturais, biologia e geologia. Porto: Porto Editora, 2012. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Iris Marion. Inclusion and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

YOUNG, Iris Marion. Intersecting voices: dilemmas of gender, political philosophy, and policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

3- Partial translation of the article by Direção Geral da Educação: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Secundario/Documentos/Avaliacao/aprend_baseres_probl02.pdf

4- We would like to thank professionals undergoing training between November 2019 and May 2020 for their participation.

Financing:This work was supported by national funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology, IP (FCT, IP), within the scope of the project EduTransfer (ref. PTDC/CEDEDG/29886/2017). It was also supported by FCT, IP, through multi-annual funding from the Center for Educational Research and Intervention (CIIE) 2020-2023 (projects with references UID/CED/0167/2019, UIDB/00167/2020 e UIDP/00167/2020).

Received: November 22, 2022; Accepted: May 15, 2023; Revised: April 24, 2023

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

texto en

texto en