Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.49 São Paulo 2023 Epub 16-Feb-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202349250586esp

ARTICLES

Perceived discrimination among teachers and traditional culture educators in intercultural education in La Araucanía, Chile*1

2-Universidad Católica de Temuco (UCT), Temuco, Araucanía, Chile

3-Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile

The article presents research results on the educational relationship between mentor teachers and traditional culture educators in the implementation of Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe (Bilingual Intercultural Education Program, BIEP) in La Araucanía, Chile. Research methodology is mixed, in which a Likert-style scale questionnaire is applied to a total of 155 participants, of which 105 are traditional culture educators and 50 are mentor teachers. Results show practices of explicit and implicit discrimination perceived by Mapuche students in the educational relationship they establish with the teacher. Both mentor teachers and traditional culture educators recognize that an educational relationship of involvement, recognition and collaboration could reverse such discriminatory practices. We conclude that the educational relationship in school education is based on implicit and explicit forms of racism towards the teaching of indigenous language and culture at school. Thus, the discrimination perceived by tradition educators challenges the school and its historical role in the processes of subalternization of the Mapuche people. In this context, there is a need for an intercultural educational intervention that provide a relevant response to the social, cultural, and linguistic diversity present in school education. This constitutes a challenge for directors, teachers, parents, and community members to advance in an inter-epistemic dialogue, based on respect, ethics, political commitment, co-responsibility, negotiation, mediation and abandonment of biased frames of reference.

Keywords Intercultural education; Educational relationship; Discrimination

El artículo expone resultados de investigación sobre la relación educativa entre profesores mentores y educadores tradicionales en la implementación del Programa de Educación Intercultural (PEIB) en La Araucanía, Chile. La metodología es mixta, se aplica un cuestionario de valoración Likert a un total de 155 participantes, de los que 105 son educadores tradicionales y 50 profesores mentores. Los resultados dan cuenta de prácticas de discriminación explícita e implícita percibida por los sujetos mapuches en la relación educativa que establecen con el profesor. Ambos actores educativos reconocen que una relación educativa de implicación, reconocimiento y colaboración podría revertir dichas prácticas discriminatorias. Concluimos que la relación educativa en la educación escolar se sustenta con base en un racismo implícito y explícito hacia la enseñanza de la lengua y la cultura indígena en la escuela. Así, la discriminación percibida por parte de los educadores tradicionales interpela a la escuela y su rol histórico en los procesos de subalternización del mapuche. En este contexto, se hacen necesarias estrategias de intervención educativa intercultural que den una respuesta pertinente a la diversidad social, cultural y lingüística presentes en la educación escolar. Esto se constituye en un desafío para los directivos, profesores, padres, madres y miembros de la comunidad: avanzar en un diálogo interepistémico, sustentado en el respeto, la ética, el compromiso político, la corresponsabilidad, la negociación, mediación y abandono de sus propios marcos de referencia.

Palabras clave Educación intercultural; Relación educativa; Discriminación

Introduction

In Chile, the implementation Bilingual Intercultural Education Program (BIEP) was conceived as a public policy, which since 1996 seeks to incorporate the teaching of indigenous language and culture in formal education, in order to favor curricular contextualization in indigenous territories (CHILE, 2010). This program has been characterized by the following stages (see table 1).

Table 1 Relevant stages of BIEP in Chile

| BIEP Stages | Characteristics and educational purposes |

|---|---|

| First (1993 - 1996) | Enactment of Indigenous Law No. 19,253, which establishes in its Article No. 28, the creation of a school program that incorporates the indigenous culture and language in the school. And, in Article No. 32, the creation of a BIEP system in territories with a high density of indigenous population. |

| Second (1996 to 2000) | Official inauguration of the BIEP in 1996, to reduce the gap in school success between the indigenous and non-indigenous population. It offers contextualized pedagogical strategies, didactic materials, and advice on the creation of a curriculum with an intercultural perspective. |

| Third (2001 - 2005) | Emergence of the Origins Program, to train teachers specialized in interculturalism and bilingualism, who are capable of generating curricular proposals. |

| Fourth (2006 - 2009) | Redefinition of the objectives of the BIEP, emphasizing the country’s cultural and linguistic diversity. Community participation is promoted for the construction of the school curriculum and the school’s educational project. Incorporation of traditional culture educators, the use of ICT and the production of school texts in indigenous languages. |

| Fifth stage (since 2009) | MINEDUC Decree N°280 emerges, to formalize the subject of Indigenous Language, which since 2013 has been taught in all schools with 20% indigenous students. Plans and programs are created for the teaching of Aymara, Mapudungun, Quechua, and Rapa Nui. |

Source: Own elaboration based on Poblete (2019).

According to Table 1, we note that through the BIEP, the State seeks to respond to the educational demands of indigenous peoples, who since the beginning of the 20th century have demanded a school education that considers the teaching of their own language and culture in the classroom (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021a; MUÑOZ, 2021). Thus, indigenous peoples seek to reverse the processes of cultural alienation and stop the loss of socio-historical and linguistic heritage induced by the Chilean education system (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021b).

In the implementation of the BIEP, a pedagogical duo is formed by a mentor teacher and a traditional culture educator. The mentor teacher is an education professional with a state-recognized professional degree. This educational agent, in an optional and/or obligatory manner (appointed by the principal of each school), is in charge of implementing the BIEP in the classroom, in collaboration with a traditional culture educator (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). The traditional culture educator is a member of one of the indigenous communities in which the school is located, who as a result of the mastery of their own socio-cultural heritage and Mapuzungun (Mapuche language) has the recognition and appreciation of the community (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019). According to the normative guidelines of the BIEP, the traditional culture educator must be chosen by the family and the community to represent them in their children’s school and, therefore, step in to teach their own language and culture in collaboration with a mentor teacher ( CHILE, 2009; Chile, 2018). As the traditional culture educator is considered to be a wise person who puts indigenous educational values and principles into practice, their figure is recognized and trusted by the members of the indigenous community (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021b). However, we observe in situthat, in general, traditional culture educators are not chosen by neither families nor communities, but they are rather chosen by the principals of each school ( ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019; MUÑOZ; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019).

Within the framework of the BIEP, the incorporation of the traditional culture educator to the school institution is justified by the lack of professional instructors who master indigenous knowledge for each specific indigenous territory and community (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). Teacher training in Chile is characterized by monoculturality, monolingualism and the hegemony of westernized, Eurocentric knowledge which does not take other type knowledge into consideration in the curriculum (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO; VALDEBENITO, 2018). Thus, it is necessary to bring forth the role of a traditional culture educator and to facilitate the incorporation of indigenous knowledge into the classroom, which allows contextualizing the indigenous culture and language into the teaching- learning process through the BIEP public policy. In this perspective, what is desirable in the implementation of BIEP is the establishment of an ‘educational relationship’ between the mentor teacher and the traditional culture educator to teach Mapuche language and culture in the classroom (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). Here, the educational relationship is defined as the objective and subjective link established by both educational agents, in which their own indigenous and non-indigenous frames of reference come into tension, negotiation and mediation, so that together they make decisions and can implement the BIEP in the school ( POSTIC, 2001; HENON, 2012; MUÑOZ; QUINTRIQUEO; ESSOMBA, 2019).

The article exposes the perceived discrimination among the mentor teachers and the traditional culture educators in the educational relationship that is established in the implementation of the BIEP in rural schools in La Araucanía, Chile.

Discrimination in the education system

Historically, discrimination has been deeply rooted in the education system, mainly in schools located in contexts of colonization, either in the social and educational interaction between teacher and students, as well as, in the framework of the school curriculum (MAMPAEY; ZANONI, 2015). In the field of schooling, discriminatory practices are manifested through attitudes, gestures, verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as in explicit and implicit violence towards groups and subjects that have been subalternized by the hegemonic society ( CÁRDENAS; AGUILAR, 2015; MEDINA; CORONILLA; BUSTOS, 2015). Here, discrimination is understood as the vexatious treatment towards indigenous individuals and groups that have been historically minoritized, product of social, cultural, linguistic, gender and religious differences, caricaturing and criminalizing the image of the different other ( MERINO; QUILAQUEO; SAIZ, 2008; AGHASALEH, 2018). Such forms of expression of discrimination in school education, are at the basis of the social and educational interaction among teachers, students, traditional culture educators, family members and the indigenous community or socially vulnerable groups. Thus, school education forms an indigenous student as a socially subalternized and minoritized one, which limits their educational success in the implementation of the BIEP in La Araucanía.

In this context, discriminatory practices are exercised by subjects who assume a power relationship, based on contempt towards a person and an ethnic group (MERINO; QUILAQUEO; SAIZ, 2008). This is based on a set of prejudices and stereotypes sedimented in the structure of the dominant society, building a relationship of disadvantage and a diminished positioning of those who live in subalternity, violating their fundamental rights (DUBET, 2017).

In the educational context, discriminatory practices against indigenous peoples can be both explicit and implicit in the implementation of monocultural and monolingual curricular plans and programs in the dominant language such as Spanish, English, or Portuguese (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021a). Explicit discriminatory practices are manifested through verbal language, physical violence and the denial of family and community participation in school education. While implicit discriminatory practices are expressed through non-verbal language, such as gestures, looks, omission, concealment, and the ‘diversion’ of attention, which denote rejection and contempt towards the indigenous person in the process of incorporating the Mapuche into school education (ÁLVAREZ-SANTULLANO, 2015; ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019).

In this perspective in the Chilean school education system, particularly in La Araucanía, discrimination is expressed through the rejection of being different, which is more apparent in contexts of social and cultural diversity, such as indigenous territories. We have observed this reality both at the international and national level, where discrimination has the following sources of origin: 1) discriminatory practices towards social and cultural diversity has rooted since the period of colonization, a process in which the indigenous person is attributed a social category of inferiorization, both cognitively, physically and affectively (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019); 2) the school has remained a space where culture is generated, but of hegemonic nature as the knowledge that is created and transmitted pushes aside indigenous knowledge under the argument that it lacks scientificity ( CÁRDENAS; AGUILAR, 2015; ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019); 3) indigenous language and culture lacks systematicity to be included into the school curriculum ( CAJETE, 1994; BATTISTE; HENDERSON, 2009); 4) the transmission of school knowledge is the only truth, which oppresses students from subalternized groups (ethnic, cultural and indigenous) through symbolic violence, involuntary devaluation of their beliefs, knowledge and cultural values ( FERRÃO, 2010; SANTOS, 2010); 5) indigenous thoughts and voices (political thoughts) are silenced and dominated by westernized cultural symbols (SHIZHA, 2008); 6) dominant groups establish the hegemony of their ideas and educational processes and, therefore, assume them as unique truths and attribute public acceptance to them (LEACH; NEUTZE; ZEPKE, 2001); 7) the hegemonic vision in the construction of scientific knowledge and pedagogical practices used in school education systems ( FERRÃO, 2010; ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019); 8) schooling is a legacy of Westernized hegemony that can reach an alienating worldview for indigenous people (MAMPAEY; ZANONI, 2015); 9) teachers hold that they are purveyors of universally true knowledge and deny any other episteme such as, for example, that of indigenous peoples (ZAMBRANA, 2014); 10) teachers are conceived as conservative ‘custodians’ of the dominant knowledge, manifesting negative attitudes towards indigenous knowledge (SHIZHA, 2008); 11) at the social level the indigenous and their ways of life have been criminalized (AGHASALEH, 2018); and 12) socio-cultural diversity is assumed as a problem to overcome, in order to achieve national unification, ensuring the economic and educational development of the population ( HORST; GITZ-JOHANSEN, 2010; MAMPAEY; ZANONI, 2015).

In this perspective, discrimination in schools through the coloniality of knowledge and state of being is a rooted practice that has become naturalized and therefore invisibilized to the agents in the educational and social environment who experience it (MUÑOZ, 2021). This is apparent in teachers, principals, traditional culture educators, education assistants, social and public policy makers, who, unconsciously or consciously, transmit prejudices and educational relations based on discrimination and contempt for the indigenous, both at the level of guidelines offered to indigenous people and in teaching and learning practices.

Intercultural education in Chile

The review of the literature in Chile shows that there are numerous empirical, and normative studies on the implementation of BIEP in both rural and urban contexts (ACUÑA, 2012; CALDERÓN; FUENZALIDA; SIMONSEN, 2018; CASTILLO et al., 2016 ; FUENZALIDA, 2014; IBAÑEZ; RODRÍGUEZ; CISTERNAS, 2015; CHILE, 2017; 2018; TORRES, 2017; VALDEBENITO, 2017). In general, research results at the national level have some common denominators: 1) in schools that implement the BIEP, hegemony views indigenous knowledge is only one and it ignores the fact that there are variations according to territory ( ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020; VALDEBENITO, 2017); 2) in the school system, ways of knowing and seeing reality that are different from those imposed by the Eurocentric monocultural logic are not accepted (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019); 3) even when there is a chance to implement the BIEP, there is a lack of an accompaniment process that enables support, monitoring and follow-up for those in charge of carrying it out in the classroom (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020); 4) the BIEP lacks a systematized model that allows involving and sensitizing the participation and social commitment of the indigenous peoples themselves with the materialization of intercultural education for all students (CHILE, 2018); 5) the logic of exclusion of the Mapuche family and community from the curricular management of educational centers continues being relegated, so integration instances are just considered extra-curricular activities in the school program ( ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021a; ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021b; QUINTRIQUEO et al., 2021 ); 6) there is a lack of contextualized didactic material adapted to students level of mastery of indigenous languages, which limits their learning (VALDEBENITO, 2017); and 7) there are methodological problems in the implementation of the BIEP in the classroom, since teachers do not know the principles of indigenous education, such as teaching methods to train new generations based on their own cultural ways (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). Likewise, they lack professional training in the use of disciplinary and methodological tools for teaching second languages ( BASTIDAS, 2015; ESPINOZA, 2016; LAGOS, 2015; LUNA et al., 2014 ; SOTOMAYOR et al., 2014 ).

The review of international and national literature sustains that the concretization of intercultural education should promote: (a) the fight against discrimination in multiple forms (explicit, implicit) (SCHMELKES, 2013); (b) the fight against the radicalization of school education systems and the segregation of individuals (CIRELLI, 2013); (c) the fight against systemic racism in schools (CASTILLO; GUIDO, 2015); (d) education supported by the rights and freedoms of all individuals, regardless of their social, ethnic and economic background (POTVIN et al. 2015); e ) the positive consideration of the particular students’ needs (over-schooling, traumatization, bullying); f) the polarization of public debates or international tensions that may have an impact on the classroom; and g) the recognition and valorization of the multiple identities of the subjects that make up society ( BONNIE, 2015; FORNET-BETANCOURT, 2003; POTVIN et al., 2015). Consequently, there is a need to incorporate the principles of indigenous pedagogy and education into school system in communities that have been colonized (CAJETE, 1994; CAMPEAU, 2017; BROSSARD, 2019; LOISELLE; MCKENZIE, 2009; TOULOUSE, 2013, 2016). This may serve as response to the social and cultural diversity which is present in the different countries.

It is challenging to address the problems experienced by mentor teachers and traditional culture educators in their effort to teach the Mapuche language and culture in La Araucanía (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). First, it would be useful to understand these problems as it may become a foundation for further course of action for successfully teaching indigenous language and culture. Second, it implies understanding how the educational relationship established by the teacher and traditional educator contributes significantly to pedagogical innovation from an intercultural perspective ( HENON, 2012; POSTIC, 2001). This implies considering the interpersonal skills that mentor teachers and traditional educators have to generate negotiation strategies from their frames of reference to articulate Mapuche and school knowledge (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). From this approach, educational relationship is conceived as a communicative interaction between two or more people where one subject influences over the behavior of the other. This involves communication processes, which are analyzable according to the way in which they develop, and the contents negotiated to understand the ways of organizing and structuring social environment in community life ( ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019, 2020). Thus, the study of educational interaction makes it possible to study the complex relationships that arise between individuals, groups or institutions in a given society.

Methodology

The methodology used has a mixed design, which seeks to understand and explain the social phenomena that are at the basis of the educational relationship between the mentor teacher and the traditional culture educator and that enable and/or limit the implementation of the BIEP ( BIQUERRA, 2004; CORBETTA, 2010; SANDIN, 2003).

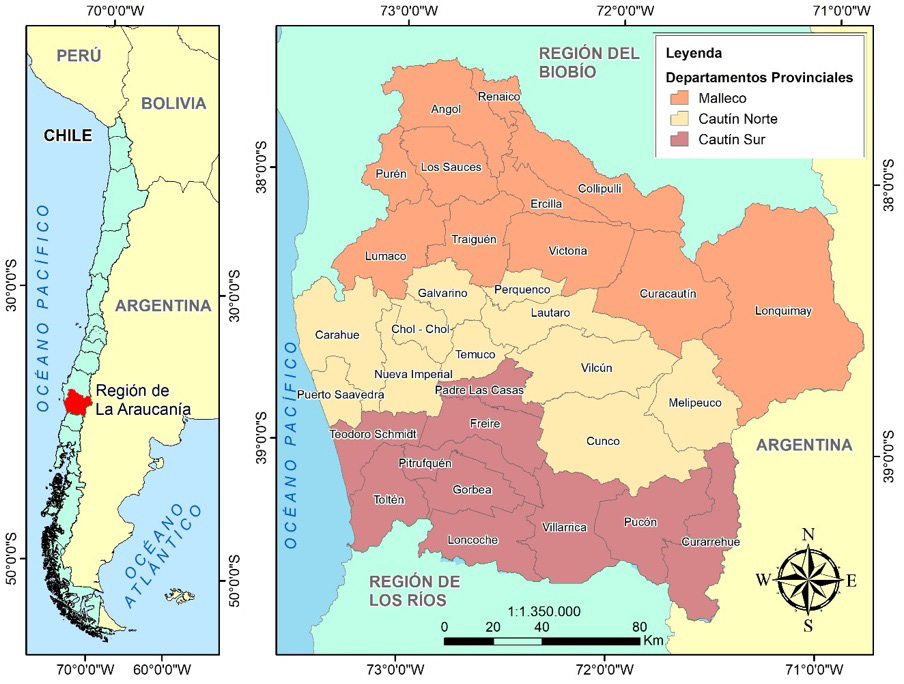

As already mentioned, the context of the study is located in La Araucanía, Chile (see Figure 1), which has historically obtained the lowest results in standardized evaluations in the Education Quality Measurement System (SIMCE). Country level (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020).

According to Figure 1, we specify that the application of the data and information collection instrument is carried out in La Araucanía within the framework of the training sessions offered by MINEDUC to mentor teachers and traditional culture educators who work in schools attached to the BIEP. These schools depend on the following public education administrations: 1) Cautín Norte Provincial Department of Education, which corresponds to schools located in the communes of Carahue, Cunco, Temuco, Galvarino, Imperial, Lautaro, Melipeuco, Perquenco, Saavedra, Vilcún and Chol -chol; 2) Cautín Sur Provincial Department of Education, which corresponds to schools located in the communes of Freire, Pitrufquén, Villarrica, Loncoche, Curarrehue, Toltén, Teodoro Schmidt, Gorbea, Padre las Casas and Pucón; and 3) Provincial Department of Education of Malleco, which corresponds to schools located in the communes of Angol, Renaico, Collipulli, Lonquimay, Curacautín, Ercilla, Victoria, Traiguén, Lumaco, Purén and Los Sauces.

The selection technique of the participants is intentional, according to accessibility and representativeness for the researcher (BIQUERRA, 2004). The participants of the study are mentor teachers (n=50) and traditional culture educators (n=105) from schools that implement the BIEP, considering a total of 155 participants. The inclusion criteria for traditional educators are: being recognized by the school institution and being recognized by the indigenous community to which they belong. The inclusion criterion for mentor teachers is to be designated by the school institution to implement the indigenous language subject.

The data collection technique is a questionnaire with a Likert-style scale which explores the psychosocial dimension of the educational relationship between the mentor teacher and the traditional culture educator. This seeks to unveil perceived discrimination practices in the implementation of the BIEP. The instrument has a high internal consistency in its different dimensions, according to its Cronbach’s Alpha equivalent to an α of ,876.

Data analysis technique consists of a descriptive statistic of the psychosocial dimension, through which it is expected to calculate the measures of central tendency, i.e., mean, median and mode. The use of these measures is justified since it allows us to describe the typical or representative values of the most frequent statements of the data set, with respect to the educational relationship, and also allows us to observe the trends or characteristics of the same. Thus, the descriptive statistic allows us to obtain a frequency distribution, with the purpose of identifying the level of recurrence in the statements (HERNÁNDEZ; FERNÁNDEZ; BAPTISTA, 2014). For this purpose, the frequency of response given by the mentor teacher and the traditional culture educator is identified for each statement in terms of its frequency (f) and identifying its percentile (%). For the descriptive analysis of the psychosocial dimension, the scores obtained by each traditional culture educator and mentor teacher are calculated based on the ideal average, i.e. from 1 to 5. Subsequently, the scores are classified into three levels, low, medium and high, whereby the ideal path is divided into three equal categories, i.e. scores from 1.0 to 1.7 correspond to a low level (NB, equivalent to disagreement). Scores from 1.71 to 3.41 correspond to a medium level (NM, equivalent to indifferent). Finally, the scores distributed between 3.42 and 5.0 correspond to a high level (NA, equivalent to agree), which allow us to understand how the BIEP is implemented in the school.

Results

Results make perceptions of mentor teachers and traditional culture educators explicit regarding the level of discrimination perceived in the educational relationship during the implementation of the BIEP in schools in La Araucanía. For this purpose, a comparative table is presented, according to the perception of each educational agent. Table 2 presents a general description of the data regarding the perception of discrimination in the educational relationship. The acronym LL refers to a low level of perceived discrimination; ML refers to a medium level and HL refers to a high level of perceived discrimination in the educational relationship between the mentor teacher and the traditional culture educator during the implementation of the BIEP.

Table 2 Perceived discrimination in the educational relationship

|

ASSERTIONS TRADITIONAL CULTURE EDUCATORS |

LL | ML | HL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (f) | (%) | (f) | (%) | (f) | (%) | |

| The educational relationship with the mentor teacher is affected by tensions or conflicts that hinder our work in the school. | 46 | 43.8 | 8 | 7.6 | 51 | 48.5 |

| The educational relationship with the mentor teacher is characterized by the fact that they ignore me in the classroom. | 62 | 59 | 6 | 5.7 | 37 | 35.2 |

| The educational relationship with the mentor teacher is characterized by the fact that they discriminate against me because I am Mapuche. | 64 | 60.9 | 6 | 5.7 | 35 | 33.3 |

| The educational relationship with the mentor teacher is characterized by the fact that they discriminate against me because I do not have a professional diploma. | 67 | 63.8 | 8 | 7.6 | 30 | 28.5 |

| In the educational relationship, it is the mentor teacher who is unaware of the Mapuche educational knowledge and skills to implement intercultural education. | 34 | 32.3 | 12 | 11.4 | 59 | 56.1 |

| In the educational relationship, the mentor teacher leaves me alone in the classroom when we implement the indigenous language course. | 52 | 49.5 | 5 | 4.7 | 48 | 45.7 |

| In the educational relationship I have noticed a low level of collaboration in class on the part of the mentor teacher. | 53 | 50.4 | 7 | 6.6 | 45 | 42.8 |

| The mentor teacher is uncomfortable with my presence in the classroom. | 66 | 62.8 | 8 | 7.6 | 31 | 29.5 |

| My knowledge and skills of the Mapuche language and culture have no place in the educational relationship at school. | 61 | 58 | 9 | 8.5 | 35 | 33.3 |

| ASSERTIONS MENTOR TEACHERS | LL | ML | HL | |||

| (f) | (%) | (f) | (%) | (f) | (%) | |

| The educational relationship with the traditional culture educator is affected by tensions or conflicts that hinder our work in the school. | 39 | 78 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 18 |

| The educational relationship with the traditional culture educator is characterized by the fact that they ignore me in the classroom. | 46 | 92 | 4 | 8 | - | - |

| The educational relationship with the traditional culture educator is characterized because they discriminate against me because I am not Mapuche. | 49 | 98 | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| In the educational relationship with the traditional culture educator, I am uncomfortable that they do not have a professional diploma. | 44 | 88 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| In the educational relationship I do not know the Mapuche educational knowledge and skills to implement intercultural education. | 31 | 62 | 6 | 12 | 13 | 26 |

| In the educational relationship I leave the traditional culture educator alone in the classroom, when we implement the BIEP. | 43 | 86 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

| In the educational relationship I have noticed a low collaboration in classes on the part of the traditional culture educator. | 41 | 82 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 14 |

| I am uncomfortable with the presence of the traditional culture educator in the classroom. | 43 | 86 | - | - | 7 | 14 |

| My knowledge and skills of the Mapuche language and culture have no place in the educational relationship at school. | 43 | 86 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 12 |

f: frequencySource: Developed by the authors

In table 2, the discrimination perceived in the educational relationship shows that traditional educators recognize that their relationship with the mentor teacher is based on tensions or conflicts that make it challenging to incorporate Mapuche knowledge and academic knowledge into the classroom (48.5). When contrasting the perceptions of the traditional culture educator with the mentor teacher, we found that 78% of the latter disagreed with this perception. This means that the mentor teachers do not manage to visualize the predominance of tensions or conflicts in the educational relationship. Indeed, most mentor teachers could hide the existence of some kind of conflict or tension in the educational relationship, which could hinder the implementation of intercultural education. Such conflicts could be associated with the feeling of invisiblization experienced by traditional culture educators or the feeling of being ignored in the classroom when teaching Mapuche language and culture.

In this sense, data show that 35.2% of traditional culture educators perceive that they are ignored in their role and function in the school when passing on their cultural knowledge. Meanwhile, 92% of mentor teachers disagree. This could mean that mentor teachers have a highly rooted ‘colonizing’ view of the traditional culture educator, but not in terms of their potential to enrich the implementation of intercultural education and consequent students’ success, whether Mapuche or non-Mapuche. Indeed, data show that the perception of discrimination of the mentor teachers towards the traditional culture educator is denied or hidden under an ideological assessment that subalternizes ‘the Mapuche’ people, without visualizing its practical implications. This divergence in the results constitutes a factor that could deepen the construction of the perceived discrimination towards traditional culture educators in the implementation of the BIEP. This is reinforced in traditional culture educators, as most of them ignore, consciously or unconsciously, feeling discriminated against for being Mapuche.

In general, data show that 33.3% of those who say they feel discriminated against at school because of their Mapuche ancestry disagree with the educational relationship with the mentor teacher. This discrimination could also be associated with the low level of schooling that traditional culture educators have. Likewise, when considering the levels of indifference and agreement, it is observed that 36.1% perceive discrimination for not having an academic major or professional diploma.

In this sense, data show that the vast majority of traditional culture educators (60.9%) do not feel discriminated against for being Mapuche. However, there is also an important percentage of traditional culture educators (33%) who say they feel discriminated in the educational relationship, which is denied by 98% of the mentor teachers. This dichotomy could be explained because the teacher assumes an educational relationship with the traditional culture educator from a hegemony of knowledge and power that, by operating as systematic racism, implicitly denies the other in the school.

In the same sense, in relation to the assertion about the lack of knowledge of Mapuche lore and know-how, 50% of traditional culture educators perceive that it is the mentor teachers who experience the problem, which limits the implementation of intercultural education. However, 62% of the mentor teachers disagreed and only 26% agreed with this statement. These discrepancies allow us to confirm that both traditional culture educators and mentor teachers perceive a sense of competence with each other for reaching students and do not assume the process of mutual interaction as a social, political, and ethical commitment for the sake of the BIEP. This problem could have an impact on the processes of organization and planning of Mapuche educational contents to teach subjects, which would hinder the educational relationship that both agents establish. This could explain the low level of collaboration of mentor teachers with traditional culture educators that we observed in the field. Thus, as a result of the homogeneous distribution in the extremes of agreement and disagreement parameters, there is a discrepancy in the perception of traditional culture educators and mentor teachers, regarding the fact that in the educational relationship they are abandoned by the mentor teacher in the implementation of intercultural education. However, mentor teachers deny such abandonment in the classroom. This perception is reinforced when we note that the perception of the mentor teacher (82%) has a high valuation of the collaborative interaction with traditional culture educators. Moreover, they perceive that their part of the collaboration favors the incorporation of Mapuche educational knowledge and skills in the school environment.

However, in our observations we found that the collaboration on the part of the mentor teachers is perceived rather as a ‘deviation’, an omission, a laissez-faire, as an alien and dangerous project to implement in the structure of traditional education, consciously or consciously, planned, or unplanned. This discomfort could be explained, for example, by the historical denial of the indigenous episteme, both in the framework of school education and in society in general.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of the study allow us to identify three main points for discussion, these being: 1) discrimination that emerges in the educational relationship between traditional culture educators and mentor teachers; 2) the low collaboration in the implementation of the BIEP; and 3) the denial of epistemological tensions or conflicts in the classroom.

Regarding levels of explicit and implicit discrimination that emerge in the educational relationship among traditional culture educators and the mentor teachers, this is a factor that has a negative impact on the teaching and learning process of Mapuche knowledge in the classroom. This is because students, upon observing the gestures, words and looks of contempt towards the traditional culture educators, assume an attitude of rejection towards learning about the Mapuche in the school environment (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019), constituting a factor that has a negative impact on the revitalization of social and cultural identity. Thus, the experience of discrimination perceived in the educational relationship towards the indigenous subject is not only an act of injustice, but it is also an act of humiliation that threatens values, identity and personality of individuals (DUBET, 2017). This reality invites us to reflect and question the status quoof discrimination in schools, which has been made invisible and naturalized in pedagogical practices, where apparently, indifference is constituted as one of the factors that make it visible (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021b). This is because by denying indifference to situations of discrimination, the need to address actions and intervention plans at the school level to address public policies and contribute to their adequate materialization becomes evident. ( ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUILAQUEO; QUINTRIQUEO, 2019; ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2020; TORRES, 2017). It is also necessary to overcome the limitations of colonialism that marks the historical context of discrimination and exclusion of the indigenous and their culture in schools, which makes Mapuche students to feel ashamed of their own ancestry. For this reason, it is essential to raise awareness of the importance of progressively eradicating discriminatory practices in society in general, and in schools in particular, in order to promote the social and educational development of people belonging to indigenous peoples.

In relation to the low collaboration in the implementation of the BIEP, in general, the traditional culture educator assumes a posture of resistance to work cooperatively with the mentor teacher, as a result of cultural differences and the history of discrimination rooted in the figure of the mentor teacher and their lack of knowledge regarding the Mapuche language and culture (QUINTRIQUEO et al., 2021). In this same sense, the low collaboration is expressed in the absence and mutual invisibility of both educational agents during the implementation of the BIEP. This is related to the standardized style of the Ministry of Education and the generalized reluctance in the school system for the implementation of BIEP. Let us consider that this program does not directly contribute to the achievement of learning in national standardized tests. Thus, this distance is produced by the opposition between educational principles and purposes that are proper to mentor teachers and the traditional culture educators, that is, formal school education and Mapuche education (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021a). Consequently, in the educational relationship there is an absence of pedagogical practices that promote cooperative learning among educational agents as a product of poor collaboration. This absence of cooperative learning could be explained by three reasons. The first refers to the attitude assumed by mentor teachers, who, consciously or unconsciously, resist the teaching of Mapuche language and culture at school (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019). This could influence the denial of Mapuche knowledge in the school, which traditional culture educators intend to incorporate. The second refers to the resistance of traditional culture educators to receive support in class management and educational contents, under the belief that it is they who are in charge of educating on Mapuche knowledge (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2019). The third, refers to the non- existence of spaces and periods for common lesson planning, in which generally it is the mentor teacher who informs the traditional culture educator the contents of the class just a few minutes before the start of the lesson (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO; VALDEBENITO, 2018). However, a common point that could be limiting collaboration between mentor teachers and the traditional culture educators in the implementation of the BIEP is the fear of both educational agents to be externally evaluated and the urge to maintain unilateral control of the learning situation.

Finally, the denial of epistemological tensions or conflicts during the incorporation of Mapuche language and culture in the classroom limits progress in the adequate implementation of the BIEP, being relegated to mutual blaming among mentor teachers and traditional culture educators (ARIAS-ORTEGA, 2020). This prevents them from having a critical vision that allows them to discuss the points of epistemological disagreement, which limits progress in making decisions that facilitate the teaching of Mapuche language and culture in the classroom. Thus, the educational relationship is strained because differences such as language, worldview, knowledge, and spirituality of the educational agents are not considered in the implementation of the BIEP (ARIAS-ORTEGA; QUINTRIQUEO, 2021a). This does not allow the generation of bonds of openness and recognition of the other from an intercultural perspective. However, the application of this approach would be a contribution for the implementation of the BIEP, from a didactic, pedagogical, and methodological point of view and for the articulation Mapuche educational contents and methods into the curriculum from an intercultural perspective (QUINTRIQUEO et al., 2021) .

In conclusion, discrimination perceived in the implementation of intercultural education in the Mapuche context by traditional culture educators and mentor teachers challenges the school and its historical role in the processes of subalternization of the Mapuche. In this context, there is a need to develop strategies for an intercultural intervention that provide a relevant response to the social, cultural, and linguistic diversity present in schools. Thus, it is a challenge for principals, teachers, parents, and community members to advance in an inter-epistemic dialogue, based on respect, ethics, political commitment, co-responsibility, negotiation, mediation, and abandonment of biased frames of reference. We conclude that in order to overcome these problems, it is necessary to build didactic, pedagogical, and methodological action strategies based on agreements which are sustained by dialog, reflection, and collaboration. This would allow us to assume an ethical, political, and epistemic commitment to transform and abandon exclusionary practices in order to advance in an education based on an intercultural approach to train future citizens, both indigenous and non-indigenous.

1- This article is part of investigation’ results of Proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación N°11200306, suports by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID). Acknowledgment to projects FONDECYT N°11191041, FONDECYT N° 1221718, FONDEF ID21I10187.

REFERENCES

ACUÑA, María. Perfil de educadores tradicionales y profesores mentores en el marco de la implementación del Sector de Lengua Indígena. Santiago de Chile: Mineduc/Unicef, 2012. (Educación e interculturalidad. Serie n. 1). [ Links ]

AGHASALEH, Rouhollah. Oppressive curriculum: sexist, racist, classist, and homophobic practice of dress codes in schooling. Springer Science+Business Media, NewYork, v. 2, p. 94-108, 2018. [ Links ]

ÁLVAREZ-SANTULLANO, Pilar. Los desvíos de la interculturalidad en el aula: análisis de un poema-entrevista como metodología de transmutación textual. In: QUILAQUEO, Daniel; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo; PEÑA CORTÉS, Fernando (ed.). Interculturalidad en contexto de diversidad social y cultural: desafíos de la investigación educativa en contexto indígena. Temuco: Universidad Católica de Temuco, 2015. p. 89-104. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin. Relación educativa entre profesor mentor y educador tradicional en la educación intercultural. 2019. 350 p. Tesis (Doctorado) – Facultad de Educación, Universidad Católica de Temuco, Temuco, 2019. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin. Relación pedagógica en la educación intercultural: una aproximación desde los profesores mentores en La Araucanía. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 46, e229579, p 1-18, 2020. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin; QUILAQUEO, Daniel; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo. Educación intercultural bilingüe en La Araucanía: principales limitaciones epistemológicas. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 45, p. 1-16, 2019. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo. Higher education in mapuche context: the case of La Araucanía, Chile. Educare, Heredia, v. 24, n. 2, p. 1-19, agt. 2020. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo. Relación educativa entre profesor y educador tradicional en la educación intercultural bilingüe. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, México, DC, v. 23, e05, p. 1-14, 2021a. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo. Tensiones epistemológicas en la implementación de la Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Ensaio, Rio de Janeiro, v. 29, n. 111, p. 503-524, 2021b. [ Links ]

ARIAS-ORTEGA, Katerin; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo; VALDEBENITO, Vanessa. Monoculturalidad en las prácticas pedagógicas en la formación inicial docente en La Araucanía, Chile. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, p. 1-19, 2018. [ Links ]

BASTIDAS, Marcelo. Educación Intercultural Bilingüe en el Ecuador: Un estudio de la demanda social. Alteridad. Revista de Educación, Ecuador, v. 10, n. 2, p. 180-189, 2015. [ Links ]

BATTISTE, Marie; HENDERSON, James. Protecting indigenous knowledge and heritage: a global challenge. Saskatoon: Purich, 2009. [ Links ]

BIQUERRA, Rafael. Metodología de la investigación educativa. Madrid: La Muralla, 2004. [ Links ]

BONNIE, Marcel. Enseigner en contexte de diversité ethnoculturelle: stratégies pour favoriser la réussite de tous les élèves. Quèbec: Chenelière Éducation, 2015. [ Links ]

BROSSARD, Louise. Les peuples autochtones: des réalités méconnues à tout point de vue. I’Icéa, Québec, p. 1-45, 2019. [ Links ]

CAJETE, Gregory. Look to the mountain: an ecology of Indigenous education. Durango: Kivaki, 1994. [ Links ]

CALDERÓN, Margarita; FUENZALIDA, Diego; SIMONSEN, Elizabeth. Mapuche Nütram: historia y voces de educadores tradicionales. Santiago de Chile: Universidad de Chile, 2018. Programa Transversal de Educación, Centro de Investigación Avanzada en Educación. [ Links ]

CAMPEAU, Diane. La pédagogie autochtone. Persévérance Scolaire des Jeunes Autochtones, Quebec, v. 1, p. 1-5, 2017. [ Links ]

CÁRDENAS, Bianca; AGUILAR, Mariana. Respeto a la diversidad para prevenir la discriminación en las escuelas. Revista Ra Ximhai, México, DC, v. 11, n. 1, p. 169-186, 2015. [ Links ]

CASTILLO, Elizabeth; GUIDO, Sandra. La interculturalidad: ¿principio o fin de la utopía? Revista Colombiana de Educación, Bogotá, v. 69, p.17-44, 2015. [ Links ]

CASTILLO, Silvia et al. Los educadores tradicionales Mapuche en la implementación de la educación intercultural bilingüe en Chile: un estudio de casos. Literatura y Lingüística, Santiago de Chile, v. 33, p. 391-414, 2016. [ Links ]

CHILE. Informe sobre Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Santiago de Chile: Ministerio de Educación, 2018. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ley 20370 Establece la Ley General de Educación, 17 de agosto de 2009. Santiago de Chile: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, 2009. [ Links ]

CHILE. Orientaciones Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Santiago de Chile: Departamento Superior de Educación General, 2010. [ Links ]

CHILE. Ministerio de Educación. Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe 2010-2016. Chile: Ministerio de Educación: División de Educación General: Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe, 2017. [ Links ]

CIRELLI, Carla. Movimiento indígena y educación intercultural en Ecuador. Revista Prohistoria, Rosario, n. 19, p. 149-152, 2013. [ Links ]

CORBETTA, Piergiorgio. Metodología y técnicas de investigación social. Madrid: McGrawHill, 2010. [ Links ]

DUBET, Francois. Ce que les discriminations font aux individus et aux sociétés. Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez, Québec, v. 47, n. 2, p. 65-80, 2017. [ Links ]

ESPINOZA, Marco. Contextos, metodologías y duplas pedagógicas en el Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe en Chile: una evaluación crítica del estado del debate. Pensamiento educativo. Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, Santiago de Chile, v. 53, n. 1, p. 1-16, 2016. [ Links ]

FERRÃO, María. Educación intercultural en América Latina: distintas concepciones y tensiones actuales. Revista Estudios Pedagógicos, Valdivia, v. 2, p. 333-342, 2010. [ Links ]

FORNET-BETANCOURT, Raúl. Filosofía e interculturalidad en América Latina. [S. l.]: Reihe Monographies, 2003. (Serie monographies; t. 36). [ Links ]

FUENZALIDA, Pablo. Re-etnización y descolonización: resistencias epistémicas en el currículum intercultural en la Región de Los Lagos-Chile. Revista Polis, Santiago de Chile, v. 13, n. 38, p. 107-132, 2014. [ Links ]

HENON, Sophie. Percevoir, comprendre et analyser la relation éducative: identification de schèmes d’action y transformation de l’habitus relationnel. Mont Saint Aignan: UFR Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société. Département Sciences de l’Education, 2012. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ, Roberto; FERNÁNDEZ, Carlos; BAPTISTA, Pilar. Metodología de la investigación. México, DC: Mc Graw Hill, 2014. [ Links ]

HORST, Christian; GITZ‐JOHANSEN, Thomas. Education of ethnic minority children in Denmark: monocultural hegemony and counter positions. Intercultural Education, Reino Unido, v. 21, n. 2, p. 137-151, 2010. [ Links ]

IBAÑEZ, Nolfa; RODRÍGUEZ, María; CISTERNAS, Tatiana. La Educación intercultural desde la perspectiva de docentes, educadores tradicionales y apoderados mapuche de la región de La Araucanía: una co-construcción. Santiago de Chile: Fondo de Investigación y Desarrollo en Educación. Departamento de Estudios y Desarrollo. División de Planificación y Presupuesto, Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2015. [ Links ]

LAGOS, Claudio. El Programa de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe y sus resultados: ¿perpetuando la discriminación? Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, Santiago de Chile, v. 52, p. 84-94, 2015. [ Links ]

LEACH, Linda; NEUTZE, Guyon; ZEPKE, Nick. Assessment and empowerment: some critical questions. Assessment Evaluation in Higher Education, Amsterdam, v. 26, n. 4, p. 293-305, 2001. [ Links ]

LOISELLE, Marguerite; MCKENZIE, Lauretta. La roue de bien-être: une contribution autochtone au travail social. Intervention, la Revue de lʼOrdre des Travailleurssociaux et des Thérapeutes Conjugaux et Familiaux du Québec, Quebec, v. 131, p. 183-193, 2009. [ Links ]

LUNA, Laura et al. Aprender lengua y cultura mapuche en la escuela: estudio de caso de la implementación del nuevo Sector de Aprendizaje Lengua Indígena desde un análisis de recursos educativos. Estudios Pedagógicos, Valdivia, v. 40, n. 2, p. 221-240, 2014. [ Links ]

MAMPAEY, Jelle; ZANONI, Patrizia. Reproducing monocultural education: ethnic majority staff’s discursive constructions of monocultural school practices. British Journal of Sociology of Education, Amsterdam, v. 37, n. 7, p. 928-946, 2015. [ Links ]

MEDINA, Virginia; CORONILLA, Ukranio; BUSTOS, Eduardo. La discriminación dentro del salón de clases. Ride, México, DC, v. 6, n. 11, p. 1-14, 2015. [ Links ]

MERINO, María; QUILAQUEO, Daniel; SAIZ, José. Una tipología del discurso de discriminación percibida en mapuches de Chile. Revista Signos, Valparaiso, v. 41, n. 67, p. 279-297, 2008. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, Gerardo. Educación familiar e intercultural en contexto mapuche: hacia una articulación educativa en perspectiva decolonial. Estudios Pedagógicos, Valdivia, v. 47, n. 1, p. 391-407, 2021. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, Gerardo; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo. Escolarización socio-histórica en contexto Mapuche: implicancias educativas, sociales y culturales en perspectiva intercultural. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 40, p. 1-17, 2019. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, Gerardo; QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo; ESSOMBA, Miquel. Participación familiar y comunitaria en la educación intercultural en contexto mapuche. Espacios, Caracas, v. 40, n. 19, p.1-21, 2019. [ Links ]

POBLETE, Rolando. Políticas educativas y migración en América Latina: aportes para una perspectiva comparada. Estudios Pedagógicos, Valdivia, v. 45, n. 3, p. 353-368, 2019. [ Links ]

POSTIC, Marcel. La relation éducative. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2001. [ Links ]

POTVIN, Maryse et al. Rapport sur la prise en compte de la diversité ethnoculturelle, religieuse et linguistique dans les orientations et compétences professionnelles en formation à l’enseignement. Montréal: Observatoire sur la Formation à la Diversité et L’équité (OFDE)/UQAM, 2015. [ Links ]

QUINTRIQUEO, Segundo et al. Conocimientos geográficos y territoriales con base epistémica en la memoria social mapuche. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, São Paulo, v. 36, n. 106, e3610603, p. 1-19, 2021. [ Links ]

SANDIN, María. Investigación cualitativa en educación: fundamentos y tradiciones. Madrid: McGraw-Hill, 2003. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura. Descolonizar el saber, reinventar el poder. Montevideo: Trilce, 2010. [ Links ]

SCHMELKES, Sylvia. Educación y pueblos indígenas: problemas de medición. Realidad, datos y espacio. México, DC: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), 2013. [ Links ]

SHIZHA, Edward. Indigenous? What indigenous knowledge? Beliefs and attitudes of rural primary school teachers towards indigenous knowledge in the science curriculum in zimbabwe. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, St Lucia, v. 37, p. 80-90, 2008. [ Links ]

SOTOMAYOR, Carmen et al. Competencias y percepciones de los Educadores Tradicionales Mapuche en la implementación del Sector lengua Indígena Mapuzugun: informe final. FONIDE N° FT 11258, 2014. Santiago de Chile: Fonide, 2014. [ Links ]

TORRES, Héctor. La educación intercultural bilingüe en Chile: experiencias cotidianas en las escuelas de la región mapuche de La Araucanía. 2017. 356 p. Tesis (Doctorado) – Faculté Des Études Supérieures Et Postdoctorales, Université Laval, Quebéc, 2017. [ Links ]

TOULOUSE, Pamela. Au-delà des ombres: réussite des élèves des premières nations, des Métis et des Inuits. Ontario: Ministère de l’Éducation de l’Ontario, 2013. [ Links ]

TOULOUSE, Pamela. Mesurer ce qui compte en éducation des autochtones: proposer une visión axée sur l’holisme, la diversité et l’engagement. Mesurer ce qui compte. Toronto: People for Education, 2016. Disponible en https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/P4E-MCQC-Mesurer-ce-qui-compte-en-education-des-Autochtones.pdf Acceso en: 16 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

VALDEBENITO, Ximena. Hacia una comprensión del vínculo entre las prácticas de enseñanza de educadores y educadoras tradicionales indígenas y el espacio escolar: Documento de trabajo N° 10. Santiago de Chile: Centro de Estudios del Mineduc, 2017. [ Links ]

ZAMBRANA, Amilcar. Pluralismo epistemológico: reflexiones sobre la educación superior en el estado plurinacional de Bolivia. Cochabamba: Fundación para la Educación en Contextos de Multilingüismo y Pluriculturalidad, 2014. [ Links ]

1-This article is part of investigation’ results of Proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación N°11200306, suports by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID). Acknowledgment to projects FONDECYT N°11191041, FONDECYT N° 1221718, FONDEF ID21I10187.

Received: April 01, 2021; Accepted: June 01, 2021

texto en

texto en