Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.49 São Paulo 2023 Epub 08-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202349255022por

ARTICLES

2-Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil

2-Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasil

This paper analyzes how two babies, ages ten to twelve months, explored the space in an infants’ classroom during their entry process in an Early Childhood Education Center in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. While in the field, during the 2017 school year, the following research instruments were used: participant observation, video recordings and fieldnotes. Ethnography in education, in dialogue with cultural-historical psychology and Henri Lefebvre’s production of space theory, enabled us to perceive the baby in a space that is both product and production of such a person. The babies experienced and explored the classroom space during their entry process in the daycare center in different ways: (i) by watching, (ii) walking, (iii) crawling, (iv) touching, (v) fighting for toys, (vi) crying, (vii) learning how to care, (viii) sleeping, (ix) interacting with their peers and other people around them. The babies’ exploration trajectories in this classroom were constituted by the dialectic unity [perception/action], as babies [perceive/act] on the space, the objects, and the people seeking to familiarize themselves with this new space. There was, then, an active search, by the babies, for a recognition of the space and people, so that, perhaps, they could feel belonging to this social environment.

Keywords Babies; Early childhood education; Space; Cultural-historical psychology; Ethnography in education

Este artigo teve por objetivo analisar como dois bebês, com idades entre dez e doze meses, exploraram o espaço de uma sala de berçário durante seu processo de inserção em uma Escola Municipal de Educação Infantil (EMEI) de Belo Horizonte. No tempo de permanência em campo, durante o ano letivo de 2017, utilizaram-se os seguintes instrumentos de pesquisa: observação participante, videogravações e anotações em diários de campo. A etnografia em educação, em diálogo com a psicologia histórico-cultural e com a teoria da produção do espaço de Henri Lefebvre, possibilitou perceber o/a bebê em um espaço que é produto e produção de tal pessoa. Os/as bebês vivenciaram e exploraram o espaço do berçário, durante seu processo de inserção na creche, de maneiras distintas: (i) por meio do olhar, (ii) do caminhar, (iii) do engatinhar, (iv) do toque, (v) das disputas por brinquedos, (vi) do choro, (vii) do aprendizado do cuidado, (viii) do sono, (ix) dos encontros desses bebês com seus pares e com outras pessoas ali presentes. As trajetórias de exploração dos/as bebês nesse berçário foram marcadas pela unidade dialética [percepção/ação], pois os/as bebês [percebem/agem] sobre o espaço, os artefatos e sobre as pessoas em busca de se familiarizarem com esse novo espaço em que foram inseridos. Houve, então, uma ativa busca, por parte dos/as bebês, de um conhecimento/reconhecimento do espaço e das pessoas para que, talvez, pudessem se sentir pertencentes a esse meio social.

Palavras-chave Bebês; Educação infantil; Espaço; Psicologia histórico-cultural; Etnografia em educação

Introduction

In this paper, we trace the trajectories of two babies in the infants’ classroom during their entry process in an Early Childhood Education Center in Belo Horizonte (ECEC Tupi). We seek to highlight the babies’ experiences in this context, as well as the importance of a space designed for such end.

It is known that spaces in early childhood education schools , when organized and designed to welcome babies, enable them to interact with each other, with artefacts, notions of time, places and other people ( ARAÚJO, 2016; GOBBATO, 2011; SILVA, 2018; COCITO, 2017; MARTINS, 2010; ALVES, 2013; MÁXIMO, 2018) reveal teachers’ and managers’ conceptions of infant education ( MAXIMO, 2018) and may contribute, or not, to infants’ well-being and to their process of building a sense of belonging ( BROOKER, 2014; SUMSION et al., 2018).

Considering the institutional space as a pedagogical tool, how can we follow the babies’ movements in these places? Some methodological perspectives, based on cartography 4 , helped us to apprehend the subtleties of the babies’ and other children’s development processes in these spaces. Niina Rutanen ( 2014), based on an observation of the daily life of babies and children in a daycare center in Finland, and drawing on the spatial perspective of philosopher Henri Lefebvre - whose theory we also refer to - argues that children are producing space throughout their time in the daycare center, whether at mealtimes, during play, or during sleep. Therefore, how is the space in an infants’ classroom in Belo Horizonte produced by the babies? How do they experience, explore and appropriate the space? Is a space planned to welcome the babies during their entry process in the center important?

Throughout this paper, based on the trajectory of two babies, Henrique e Breno 5 , we will try to provide possible answers to these questions.

Thinking about space

Space as a concept and problematization

In 1889, the philosopher Henri Bergson (France, 1859-1941) released his first major book, Essay on the immediate data of consciousness ( BERGSON, 2013). At a first glance, it would not be absurd to think of the content of this late 19th century book as a treatise on space. However, it is exactly the opposite. Bergson, at that moment and throughout his career, tried to get rid of the supposed primacy of what we ordinarily call space in favor of a creative duration (or, simply, time).

For the philosopher, what prevents us from truly accessing the immediate data of consciousness, and thus from satisfactorily knowing the world and our own intellect, is precisely spatial mediation, which insists on harassing us. We can think, along with Bergson, in a duality of principle: everything that is of the order of spatiality would have simultaneity and juxtaposition as its main characteristic; whereas succession is on the side of time. Time is the place of heterogeneity and space of homogeneous things. There is no succession in space, only discrete elements “thrown” into the world, which have no relations with each other, and which therefore do not mean anything by themselves. We can infer the need for an organization of spatial data coming from outside, or, roughly speaking, the need for a consciousness whose main characteristic is, precisely, to be temporal. However, how to think this consciousness? How to establish categorically that it is of one type and not another? What is the type or typical that such an organizing matrix should have?

All these questions are far too complex and, in our opinion, are of little help in understanding the world and the relationships in it, as is the case of the relationships between babies Breno and Henrique and the classroom space at ECEC Tupi. If we assume, as opposed to Bergson, a productivity or a creativity of space by itself, or even, if we understand that the world has privileged directions, that things are not simply arranged simultaneously and homogeneously in reality, then perhaps the issue becomes clearer. More precisely, based on the daily planning and experience at ECEC Tupi, we will show how the interactions of these babies (between themselves and adults, with the available artefacts, and also with space) change qualitatively. What is evident, in our view - and will be shown throughout this essay - is the impossibility of reducing spatial data, and even space experience, to a single perspective.

Space as social relationship

From Henri Lefebvre’s (France, 1901-1991) perspective, space is not passive, empty, “but a set of relations” between things (objects and products) “that implies, contains and disguises social relations” ( RUTANEN, 2014, p. 18). The space is produced both by what refers to its materiality and by the relationships established therein: “the social space manifests its versatility, its ‘reality’ at the same time formal and material. A product that is used and consumed, it is also a means of production; exchange networks, flow of raw materials and energies that cut the space and are determined by it” ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000, p. 127). Space, therefore, is not only composed of what is concrete, palpable, it contains social relations, power relations, micro and macro interactions. It is the unity between the “productive forces and their components (nature, labor, technique, knowledge), the structures (property relations) and the superstructures (the institutions and the state itself)” (p. 128). Hence, thinking of space by itself, “in itself,” is inconceivable ( SCHMID, 2008), since it is a product and also a means of production, historical, “social,” “experientially constructed” ( HARRISON; SUMSION, 2014, p. 3), dynamic, and complex ( SUMSION et al., 2018).

When a researcher analyzes some space, such as a classroom, he/she does what Lefebvre calls clippings in the social space. According to Lefebvre ( [1974] 2000 p. 129), “there is not one social space, but several social spaces” that have interdependence and implication as their primary characteristic; thus, any analysis of a “part” of that space represents an abstraction.

For the French author, the process of producing space happens in a dialectical way through the triad: representations of space, spaces of representation, and spatial practice. The representations of space have an allegedly objective - or conceived - character, they are those planned by “scientists, planners, urban planners” etc. ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000, p. 66). These conceived spaces “are penetrated with knowledge (knowledge and ideology mixed together) that is always relative and changing” (p. 69). Space is, according to Alves ( 2019, p. 556), seemingly “apolitical,” “neutral,” made for the purpose of naming “what citizens can and cannot do.” In these representations, the intention is to identify “lived and the perceived to the conceived,” even though each of these spatial realms has its own features.

The spaces of representation - or lived spaces – are what is “seen, spoken”, is affective, implying places of “passion and action, of lived situations, [...] it is essentially qualitative, fluid, and dynamic”. ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000, p. 70). It “subverts conceived space logic,” revealing how social action also produces space “from the expressions/actions of radicalism.” ( ALVES, 2019, p. 559). The children’s march on the National Day for Children’s Education 6 ( Figure 1), in some schools in our country, can be considered a subversion of the conceived space, since streets, sidewalks, the public space, generally speaking, in Brazil, are not thought or conceived for small children.

Source: Research data.

Figure 1- Children from ECEC Tupi at the International Day of Early Childhood Education march

In this sense, the practice of spaces (perceived spaces), in which children occupy the streets as in the case above, presupposes the articulation of the conceived and experienced dimensions. Such practice immediately clarifies the necessary interdependence between people and the space in which they are inserted, which they modify with the most diverse intentions 7 . For Vygotsky ([1933] 1933), as for Lefebvre, there is no split between people and space, between people and environment. These two dimensions, [person/environment], are understood as a unit of analysis, named by the Belarusian author as perejivânie (lived experience). Perejivânie is the unique way in which each person experiences a given situation, that is, it is as much a part of the person as the environment in which that person is. In this sense, Veresov and Fleer ( 2016, p. 330) argue that “the perejivânie concept is an analytical tool for examining the dialectics of the evolutionary and revolutionary aspects of development, as well as the dialectics of the social and the individual.” By focusing on the dialectical unity [person/environment], Vygotsky consequently understands that the “environment is not something static, composed only of materiality, but is psychic and cultural” ( VIGOTSKI, [1933] 1933, p. 683). Thus, the environment is also transformed, as well as the person who experiences it.

Therefore, for both Lefebvre and Vygotsky, it is only possible to speak of space, or even in the production of space (conceived/perceived/lived), because there are people who comprise and produce it. Whatever these spaces may be, “human beings cannot be absent, they do not allow themselves to be excluded” ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000, p. 189). In this sense, it is worth emphasizing, once again, the space by itself does not exist, it is a product and means of production of everyday life, it is historical and, therefore, it is also movement, experience, living, environment, including the person himself.

Consequently, it becomes crucial to think about the relationships between the designed space of the daycare center (the architectural project, the policies and legislation for early childhood education across the country, the curriculum, the school’s political and pedagogical plan, etc.); the space affectively experienced by the babies and their teachers symbolically covers the physical space and enables creation, subversion ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000) and people’s development ( VIGOTSKI, [1933] 1933; and the perceived space (articulation between the lived and conceived dimensions).

ECEC Tupi and the classroom spaces

Before the ECECs were established in Belo Horizonte, educational care for children between zero and five years of age was provided primarily in private or philanthropic daycare centers. The municipality was one of the only ones in the country that did not have municipal daycare centers with planned spaces for this purpose. The ECECs planning began in 2002. During this period, suitable locations were chosen, spread throughout the regions of the city, in such a way that buildings were not concentrated in a single area ( AMORIM, 2010). According to Amorim ( 2010), the construction of the ECECs’ buildings took into consideration the Child School Management Group guidelines, based on suggestions from the Educational Secretariat of Belo Horizonte, the resolutions of the Municipal Education Council - CME/BH no. 01/2000 - “which sets standards for early childhood education and, in its articles 14 and 15, and the national quality parameters for early childhood education” ( AMORIM, 2010, p. 76). We notice that, since the outset, the ECECs were designed to function as early childhood education schools that cares for children from zero to five years of age. Therefore, their spaces were planned and organized for this purpose.

Thus, ECEC Tupi is a large school, designed to meet the demands of 440 children, built on a slightly hilly terrain with a steep slope at the back. Going through the street, it is possible to see its entire extension and facade, because it does not have concrete walls that would make it impossible to see and/or contact the inside and/or outside of the school, an important dimension in early childhood education ( Barbosa, 2006).

ECEC Tupi’s entrance gate is next to a completely open playground ( Figure 2), with green grass, a big tree (which shades the two swings), some plastic toys (two little houses and a slide) and two wooden swings. The children, when they are there, have contact with passers-by on the street and can observe the space around them. This relationship between children and the outside world, enabled by the architectural option of a fence instead of a wall, represents, to some extent, a novelty, because usually, young children are relegated basically to private spaces, almost totally excluded from contact with public life.

The school building has two floors and a large outdoor area. As we enter, on the left, there are two restrooms accessible for children with disabilities, as requested by the competent agencies during the design of the ECECs. In front of the entrance door, there is a hall. In it, there is a large, metal, transparent door, which, at the time of a celebrations, meetings, etc., is opened to its full extent and people have easy access and view of the entire hall. The school administration office is located in this entrance hall, where there are collages made by the children and newsletters for the school community. In this hallway, located on the first floor, are the principal’s and coordinator’s offices, a few activity classrooms (for older children), the infants’ classroom, the library and two restrooms. These toilets have sinks and mirrors suitable for the children’s height, which corroborates the concept of a space designed for the care of small children.

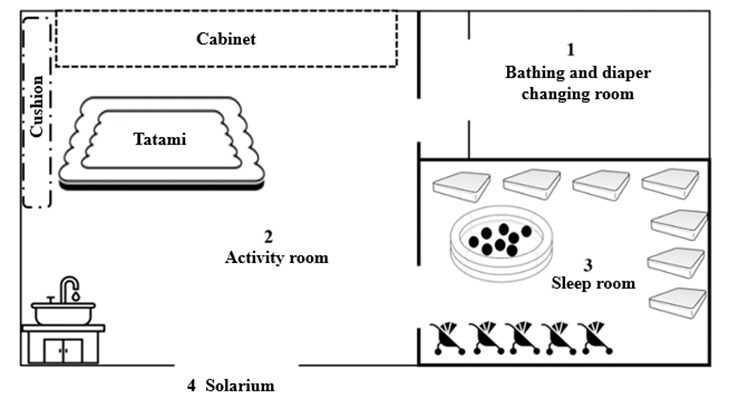

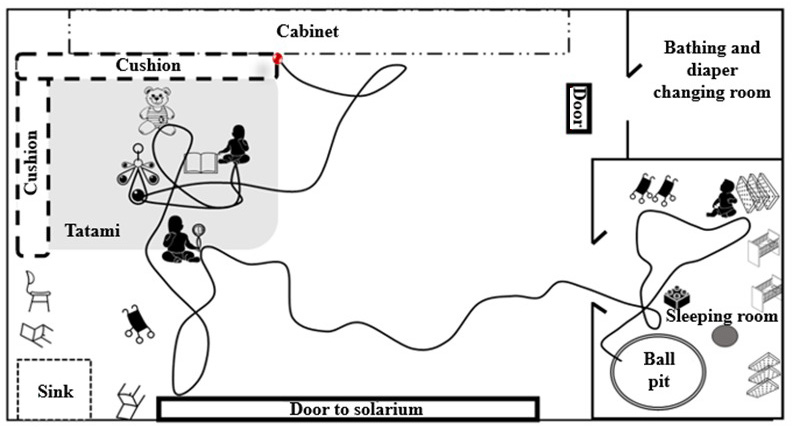

The rooms in the institution are well ventilated and have plenty of natural light. On the second floor, they have glass doors the length of an entire wall, where children have access to visualize the solarium (the outer part of the rooms on the first floor). The rooms on the second floor have large, low windows through which the children can see outside the school. The classroom ( Figure 3) is divided into four spaces: the bathing and diaper changing rooms (1), the activity room (2), the sleeping room (3), and the solarium (4).

The bathing and diaper changing rooms (1) are the space where the babies’ hygiene is carried out. The room has two showers and two medium-sized bathtubs, attached to a large bench. There is also a diaper changer on this bench. The activity room (2) is where children spend most of their time at ECEC Tupi. It has a large closet where the children’s belongings and the teachers’ work materials are kept. In it, there are some niches and each one belongs to a baby. Next to this cabinet are the tatami (rubber mat) and a snake-shaped cushion. On top of the mat is a pendulum made of colored ribbons. In front of the pendulum is the room’s sink. There is a built-in cabinet in it, located both at the top and bottom of the sink. Next to the sink is the glass door to the solarium (4). This space is outside the classroom. It is tree-shaded and has two masonry benches covered with yellow tiles. Its floor is almost entirely paved with cement. Finally, there is the sleep room (3), which is located opposite to the activity room and next to the bathing room and solarium. Access to it is only possible through the activity room. There are small cribs whose height and depth facilitate the babies’ autonomy to get in and out whenever they want. Figure 4 shows the classroom spaces.

Brief description of the classroom routine

The babies were in the classroom full time, from 7am to 5pm. There were twelve babies enrolled and seven teachers who took turns between the morning and afternoon shifts. When the babies arrive in the room, the teachers put them in their carts on the mat and fed them with milk bottles. The teachers then distributed a variety of toys on the mat and allowed and/or encouraged the babies to move around the room on their own initiative. At some moments, they opened the sleeping room, expanding the babies’ moving space. One teacher and her assistant 8 were responsible for the care of the babies during this period in the morning, while the other teacher could take care of the schedules. After this moment, around 8:20am, the teachers offered some fruit as a snack. At this point, the babies usually went to the solarium, where a variety of toys and a rug were available. During the time in the solarium, the teachers who had welcomed the children generally left the room to fulfill the collective planning time and two other teachers arrived and started the babies’ bathing time 9 .

After the baths, around 10:30 am, teachers began to organize the activity room and the babies for lunch, which started at 10:50 am. When all the babies had already been fed, the preparations for bedtime began: the teachers checked if there was any need to change diapers, offered water to everyone, partially closed the window of the sleep room and were silent, so that the babies could fall asleep. As soon as the children began to sleep, only one teacher remained in the classroom until the arrival of the afternoon shift teachers at 1 pm. During the afternoon shift, the routine was repeated, but the difference was the frequency of trips to the solarium (more frequent than in the morning) due to the temperature and the shade of the tree in this space.

After this brief explanation of the classroom routine, we see how the school’s organization and temporal planning is something indispensable and complex. The spatial triad (conceived/lived/perceived) is tensioned by the temporal dimension marked by the routine rhythm and presents several possibilities, as well as limits, to babies and their teachers. In this sense, “to think the children’s [and babies’] body in movement” ( SILVA, 2012, p. 219) is one of the challenges for educators and researchers who work in early childhood education schools. In the next section, we will analyze the different experiences of two babies exploring the classroom space.

Exploration trajectories of the classroom space

Aiming to understand how babies experience the space in the ECEC Tupi classroom, we contrasted different research instruments, using ethnography in education as a theoretical and methodological perspective. According to Judith Green and collaborators ( 2005), ethnography in education involves a dynamic process based on the researcher’s responsive and reflective attitude throughout the time in the field. Furthermore, it demands (i) contrasting information, (ii) seeking an emic perspective (from the point of view of the members themselves) with the people in the research, and (iii) an ethical stance ( GREEN et al., 2005, p. 31). For Green et al., ( 2005), the research information contrast is fundamental to give visibility to the often invisible practices that guide people’s actions in their daily lives. Moreover, “the juxtaposition of perspectives within a context provides information that study from a single perspective cannot reveal.” ( GREEN et al., 2005, p. 35). In other words, the use of different types of data, methods, or theories allows the researcher to build a well-founded interpretation.

During the construction of the empirical material, we remained in the field throughout 2017 10 , videorecording the classroom routine, writing fieldnote and conducting semi-structured interviews with the teachers, pedagogical staff and the babies’ families. We performed a micro genetic and contrasting analysis of the video records, fieldnotes, and interviews, as well as a comparison with theoretical studies, which allowed us to elaborate maps of the space exploration trajectories by the babies.

Our ethical stance pervades the entire research process, based on unconditional respect for the otherness and wholeness of babies and other research participants, teachers and families ( NEVES; MÜLLER, 2021). Such stance was materialized through several actions that, perhaps, were not directly related to our objective, but that were absolutely necessary, such as soothing or giving a bottle to a baby, talking to the teachers, etc. At certain occasions, it was critical to be sensitive to the babies’ and their teachers’ distancing movements. Thus, occasionally, we turned off the camera or shifted the focus of the footage when we noticed some uneasiness from the teachers or the babies.

Next, we will present two events 11 in which we focus on how two babies experienced and explored the infants’ classroom. Henrique (12m, 22d) 12 and Breno (9m, 12d) entered ECEC Tupi at different points in time. Breno started attending the center on the first school day of the year, February 2, 2017, and Henrique joined on May 22 of the same year. The selected events helped us to observe and contrast the exploration in the classroom of two distinct ways of locomotion - crawling and walking - marked by the dialectical unity [perception/action]. According to Vigotski:

[The] structural and integral nature, which is proper to both sensory and motor processes, helps us to explain the relationship that unites sensory and motor processes. They are united to each other by a structure. What has been said should be understood as follows: perception and action initially constitute a single, indivisible process, where action is the dynamic continuation of perception; both constitute an overall structure. Both perception and action manifest themselves as two parts, dependent on the laws of general formation of a single structure. There is, between these two processes, an internal structural connection that is essential and allocated of meaning. [...] Perception and action are united by affect. ( [1932] 1932, p. 297).

Therefore, we argue that affective perception and psychomotor action constitute a dialectical unit that constitutes Breno and Henrique’s trajectories. They [perceive/act] on the space, the artefacts, and on people in an attempt to familiarize themselves with this new space in which they are. Through these experiences, the babies produce processes of meaning and constitute their subjectivities.

Breno exploring the surroundings

Breno, at the beginning of February 2017, was moving in short spaces, with a lot of difficulty, dragging himself. He would put one arm in front of his body and lean over, moving forward with the help of one of his legs. The event “Breno exploring the surroundings” took place three months after his first day at the school.

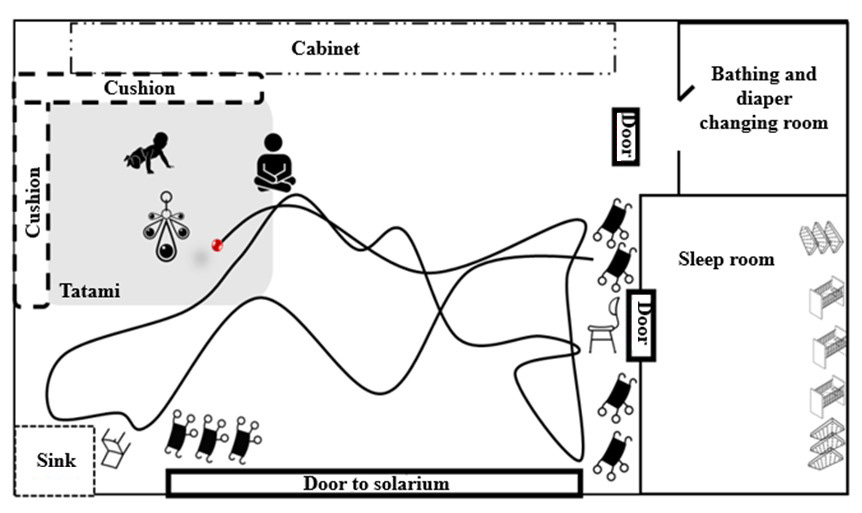

This event lasted 22 minutes and it was the first time the researcher noticed Breno (11m, 18d) exploring different spaces in the room, as he often showed interest in standing on the cart and/or sitting on the mat in the room, playing with different artefacts arranged by the teachers. On April 3, 2017, the baby arrived at the room with his mother, was placed in the stroller by the teacher and, around 7:20 am, Ms. Soraia, his teacher, asked him: “do you want to go down/ Breno:::?”. As soon as Ms. Soraia put him on the floor, he began his exploration of the room ( Figure 5 and 6).

The baby crawled to the ribbon mobile, touching it and causing a pendulum movement, went to a stroller, went to a chair, and tapped its feet, went to a stroller again, and tried to turn the stroller’s wheel with his hands ( Figure 6). The coordinator, Ms. Amalia, who was present in the room at that moment, called out to the baby: “Breno::/ hey Breno::”. The baby responded to her call by crawling to her. Then he went to the cabinet and the teacher, Ms. Soraia, said with a smile: “Breno:::/ you are really exploring the environment::/ huh?” The baby sat down, grabbed the nearby chair and pulled it over to his side. The chair made a noise and the baby kept pulling it. Breno went back to the cabinet and put his head on the door, repeatedly, as if to open it. He tried to move again and the teacher pulled him out, possibly fearing that he would hurt himself. The baby crawled again to the cart where Maria was lying, turned its wheel and remained there; turning the wheel of the cart, for 4 minutes (Chart 4 - Figure 6). It becomes apparent that Breno [perceived/acted] on the artefacts according to what affectively mobilized his attention.

Breno, as mentioned, had been attending ECEC Tupi for three months and the teachers knew him and had begun to establish an affectionate relationship with him which provided him with the confidence to explore the space. Ms. Soraia’s line, “you’re really exploring the environment::/ huh?::”, shows recognition of the baby’s movement, indicating a difference from the previous days, when Breno moved less around the classroom. Thus, such exploration was supported affectively and cognitively by the teachers’ presence, speeches and actions.

In Figure 5, it can be seen that Breno’s flow of movement was restricted to the activity room, as the door to the sleep room was closed, which differs from Henrique’s trajectory, which we will see in the next section. It is noticeable that the baby crawled through the empty spaces without obstacles. His exploring possibilities were, therefore, marked by the way he moved and by the sounds and movements that this moving around the room allowed and produced. Thus, the swing of the mobile, the spinning of the wheel and the noise of the chair, for example, were perceived by the baby, triggering him to act on the objects. We argue that a baby’s act of moving not only interferes in his/her psychological development, but also in his/her relations with others ( WALLON, [1954] 1954, p.81). Here, we can mention the moment when Ms. Amalia, the coordinator, called for the baby and the baby’s quick response.

Breno explored the room at his own pace, through crawling, marked by the intentionality of experiencing different artefacts (mobile, chair, stroller wheel). Since he had already known the room for some time, the baby chose to act on different objects, spending a significant amount of time at stops during his displacement (for example, four minutes spinning the stroller wheel), making the objects begin to belong to him.

The space perceived/ experienced by Breno includes different possibilities that, perhaps, were not conceived at the time of the ECECs planning. As an example, we can mention the strollers, which were in the classroom with a defined function (to offer rest to the babies), but Breno focused on turning their wheels, noticing a movement that caught his attention. Thus, it is clear that, besides the purpose for which an artefact was designed, the babies found several other purposes in the objects offered to them. The same situation occurred with the chair, whose use was conceived for the teachers to offer a bottle to the babies, and that was dragged by the baby, serving, therefore, to another purpose, completely different from the one originally conceived for it.

Therefore, Breno’s movements, when experiencing the space, were constituted by a dialectical tension [perception/action]. At the same time that he was familiarized with the environment, feeling affectively and cognitively safe because he had been there for three months, he felt “foreign” and tried to familiarize himself with the existing artefacts, affectively perceiving their different possibilities, acting on these artefacts (making them swing or spin, dragging them). In other words, the acts of [perceiving/acting] on the artefacts, as well as becoming familiar with the people around them, build a “sense of belonging” for the baby in that space ( SUMSION, 2018; BROOKER, 2014). The movement of [perception/action] was also present in Henrique’s trajectory, as we will see below.

Henrique exploring the surroundings

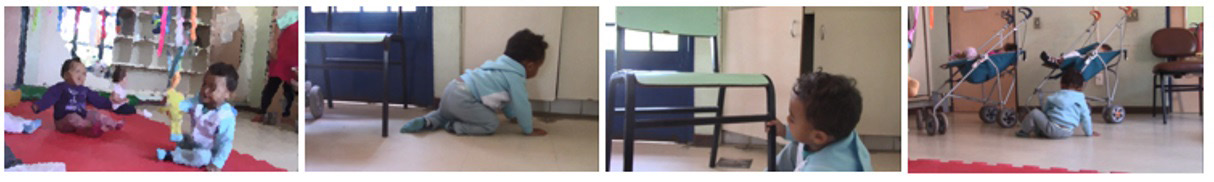

Henrique’s entry process at ECEC Tupi was different from his classmates. The baby started attending the infants’ classroom walking at 12 months of age. On his first day at the center, he showed a lot of interest in the artefacts on the mat and in his new classmates. He also proved to be a very curious baby with the space: he climbed on the objects around the room, in the closet niches, empty strollers, cribs, and armchairs.

Henrique’s (12m, 27d) second day at the center (5/24/2017) was also marked by his curiosity with the classroom during the morning shift. The baby arrived in the room at 7am and was quickly already on the floor, walking and exploring the space. During this time, one of the teachers and her assistant were responsible for bathing the babies together, while the other teacher was in the room with the other babies. Only seven babies were present that morning. Henrique’s exploration event lasted 40 minutes ( Figure 7 and Figure 8).

The baby began his exploration by climbing into the niches in the cabinets. Next, he played with a teddy bear laid out on the mat. The teacher, Ms. Telma, who was nearby, interacted with him, saying “squeeze::: him::: (the teddy bear) give him a tight hug:::/ hey::: what a delight:::”. Then he left it on the mat and became interested in the cloth book that his classmate Valeria was holding, and the two of them touched the book together. Valeria took one side of the book and Henrique the other. The baby looked at his classmate, let go of the book and went to the ribbon pendulum. At this moment the teacher commented “Yap:::/ (Henrique) is recognizing everything:::!” Then the baby walked to the closet in the classroom, went to the pendulum again and ended up meeting Larissa, who was holding a toy: two rattles wrapped in a green ribbon string. Henrique then pulled one of the rattles toward his side, and Larissa pulled the rattle toward her side, babbling “ba:::/ba/ba:::”. Henrique let go of the rattle and crawled back to the teddy bear.

He went on exploring the whole room, touched the chairs placed at different points, touched the handles of the sink cabinet, approached the researcher, watched the camera carefully, walked past the researcher, entered the sleep room, went to the ball pool, left the sleep room, went back to the activity room, went to the ribbon pendulum, returned to the sleep room, tried to climb into the ball pool, fell down, approached another classmate, Maria, who was sitting on the stacked cribs. As soon as the baby girl moved away, Henrique also settled down in the cribs, looked at the researcher and the teacher, smiled, crawled out, and finally got into the ball pool and stayed there until the teacher took him for a bath. All this trajectory, briefly outlined, highlights the number of moves made by Henrique during his second day at ECEC Tupi.

Ms. Telma, the teacher, was present the whole time during this event. She sat on the mat, watching the new baby and the others, assuming a “stable position in space”. ( RUTANEN, 2014, p. 23). In other words, she allowed the baby to move around the room without her direct intervention. The teacher seemed to acknowledge that the baby needed to feel a sense of belonging to the room through [perceiving/acting] on the objects when she rejoiced “Yap:::/ (Henrique) is recognizing everything:::!”. Sumsion and collaborators ( 2018) argue that the teacher, even in a “neutral” posture, subtly orchestrates the babies’ movement flows and interactions, that is, even without direct interference, the adult is composing the space corporally, by planning and organizing the environment.

At ECEC Tupi, the babies, during most of the time they spent in the classroom, made movements and interacted with the other babies, at their own pace, according to their own initiatives or, even, motivated by their teachers or available artefacts. In Henrique’s case, the teacher’s position of neutrality and respect contributed to his discovery of the space in the classroom. That is, he felt safe to explore the room autonomously, on his own initiative and at his own pace ( CORTEZZI, 2020). Moreover, on that day, there were several types of artefacts (stuffed animals, books, plastic toys, different chairs, a ball pool) on the mat, allowing the baby to interact with his peers, as we could see in Henrique’s meeting with Valéria, Larissa and Maria.

As mentioned, Henrique showed an enormous need to feel the artefacts: he touched the chairs, the carts, the rattle, the niches in the cabinet, and the ribbon pendulum. Vygotsky ( [1934] 1934) states that affective perception, in the early stages of the child’s life, is closely linked to motor skills. Therefore, it is through sensory-motor activity that movements “retain a subjective-affective feature” which, in turn, will enable more precise perceptions of the excitations caused by external objects ( WALLON, [1954] 1954, p. 78). The baby, by touching the objects, perceives the space, as well as appropriating their meanings. Going further, as he tries to feel artefacts and people, he is relying on his affective perception and memory, which will help him make meanings of the space that he is beginning to know ( VIGOTSKI, [1934] 1934).

In other words, the baby, by [perceiving/acting] on the room space, was attributing meanings to this experience and to this space. Thus, the relationships with the artefacts and with the other babies are different from those Henrique possibly experienced at home, because, being an only child, he had little contact with other children 15 . Besides, space is not something inert, it contains social relations and it is constantly produced. ( LEFEBVRE, [1974] 2000). Accordingly, from the entry of the baby in this classroom, a double transformation occurs: the baby modifies the space he starts to inhabit, as this same space modifies him. This transformation occurs, precisely from [perception/action] in a dialectical movement, triggering different making meaning processes.

Henrique’s event demonstrates a search for a “sense of belonging” ( SUMSION, 2018; BROOKER, 2014) that goes through a need for perception and an investigation whose endeavor is to know/recognize the space, the people, and the artefacts in the room. This may have happened because he did not yet know the room, the objects, nor the people there. We can infer that the baby seemed to want to know all the spaces at the same time, making quick movements back and forth exploring the possibilities of the available objects, as well as approaching other babies. We noticed that Henrique moved through a wider space than his colleague, Breno, because his possibilities of locomotion were unrestricted, the sleeping room was open and the cribs were placed against the walls, so that there were no obstacles for the him and other babies.

For those who were already in the space, Henrique was something new, a “new baby,” someone who had just arrived. This “new baby” status marked his movement around the room, as well as his quick interactions with the teacher and the other babies. In fact, Henrique didn’t fight for the artefacts that interested him (book and rattle) with Valeria and Larissa. It is important to mention that Henrique tried to interact with the babies, but, curiously, we did not notice any interest on the part of the other babies to start an interactive process with him.

In the same physical space, there are spaces that are not accessible to everyone ( RUTANEN, 2014). We argue that such accessibility is closely related to the babies’ possibilities of locomotion. Henrique was already walking and reaching the niches in the cabinets, touching the door glass that leads to the solarium, climbing alone in the ball pool. Breno, who was still crawling, could not do it. On the other hand, Breno could look and perceive the room from another perspective, closer to the floor, once he saw and explored the room’s drain that was located on the floor and the wheels of the carts that were right at his eye level ( Figure 6), actions that Henrique, during our observations, had not done.

Moreover, Breno, probably because he already knew more about the space, took his time to [perceive/act] on each artefact, trying to become thoroughly familiar with what affected him and what was very close to his field of vision. Henrique, on the other hand, quickly perceived and interacted with several objects and people, also trying to familiarize himself with everything that affected him, since, for him, everything was new and possibly amazing. This overall movement was only possible, because Henrique already walked and his field of vision was enlarged by his agile locomotion. He could quickly walk around the whole room, including the sleeping room. In this perspective, the dialectic unity [perception/action] shows us how the body is central in the production of space, affecting and being affected by situations and things present in this space ( LEFEVBRE, [1974] 2000; SUMSION, 2018).

Final remarks

The analyses of Henrique and Breno’s experiences in the classroom space, evidenced in the exploration trajectory maps, made visible the space as a place that produces and is produced in social relations. Different babies experienced the ECEC Tupi’s space in different ways, just as space is produced in different ways by different people. The babies’ entry process in this classroom was marked by exploring the space in many ways: by looking, walking, crawling, touching, competing for toys, crying, learning how to care, sleeping, and meeting their peers and other people present there. There was an active search, by the babies, for a recognition of space, of people, so that, perhaps, they could feel belonging to this social environment.

This means that we should no longer think of space as a simple receptacle of things simultaneously arranged, but as a place where different experiences can take place and be interrelated. Different babies, each in his/her own way, may affect/produce/act and be affected by the space/time of a school.

Thus, based on an approach that assigns both the child and the space a leading role, even if in different levels and degrees, we were able to observe the fruitfulness of the discussion raised concerning, more specifically, the unique experiences of two babies who had equally different motor possibilities and interests. In this sense, the only thing that remained as a constant, something repeated, was the fact that these babies were in a space thought/planned to be experienced by them. In other words, based on this discussion about the space of an infants’ classroom in early childhood education, we see how important an organized space is to welcome babies for them to have quality in the use of time and in the relationships established in this collective context. Maybe that’s why Breno and Henrique, in their search for a sense of belonging and recognition of the space and of themselves, perceived everything around them, touched, felt, had access to the available resources.

Finally, we argue that the organization of times and spaces in early childhood education must constantly be guided by the specificity of the field “whose function is sustained by the respect for children’s fundamental rights and the assurance of an integral development that is guided towards the different human dimensions (linguistic, intellectual, expressive, emotional, corporal, social, cultural)” ( ROCHA, 2008, p. 12).

REFERENCES

ALVES, Glória da Anunciação. A produção do espaço a partir da tríade lefebvriana concebido/percebido/ vivido. Geousp – Espaço e Tempo, São Paulo, v. 23, n. 3, p. 551-563, dez. 2019. [ Links ]

ALVES, Iury Lara. Bebês, por entre vivências, afordâncias e territorialidades infantis: de como o berçário se transforma em lugar. 2013. 161 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, 2013. [ Links ]

AMORIM, Marcelo Otávio. As unidades municipais de educação infantil de Belo Horizonte: investigações sobre um padrão arquitetônico. 2010. 161 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2010. [ Links ]

ARAUJO, Djanira Alves Biserra. Os espaços lúdicos como elementos formadores em uma creche do município de Santo André. 2016. 131 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Nove de Julho, São Paulo, 2016. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Maria Carmem. Por amor e por força: rotinas na educação infantil. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2006. [ Links ]

BERGSON, Henri. Essai sur les donnés immédiates de la conscience. Paris: PUF, 2013. (Quadrige). [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei 12.602/2012. Institui a Semana e o Dia Nacional da Educação Infantil. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/L12602.htm Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

BROOKER, Liz. Making this my space: infants’ and toddlers’ use of resources to make a day care setting their own. In: HARRISON, Linda J.; SUMSION, Jennifer (ed.). Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and Care: exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research and practice. Springer New York: Springer, 2014. p. 29-42. [ Links ]

CASTANHEIRA, Maria Lucia et al. Interactional ethnography: An approach to studying the social construction of literate practices. Linguistics and education, Santa Barbara, v. 11, n. 4, p. 353-400, 2000. [ Links ]

COCITO, Renata Pavesi. Do espaço ao lugar: contribuições para a qualificação dos espaços para bebês e crianças pequenas. 2017. 184 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Presidente Prudente, 2017. [ Links ]

CORSARO, Willian A. Friendship and peer culture in the early years. Norwood: Ablex, 1985. [ Links ]

CORTEZZI, Luíza de Paula. As vivências no currículo do berçário: as possibilidades de autonomia e proteção entre bolinhas e almofadas. 2020. 153 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2020. [ Links ]

GOBATTO, Carolina. “Os bebês estão por todos os espaços!”: um estudo sobre a educação de bebês nos diferentes contextos da vida coletiva da escola infantil. 2011. 222 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2011. [ Links ]

GREEN, Judith; DIXON, N. Carol; ZAHARLICK, Amy. A etnografia como lógica de investigação. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, n. 42, p. 13-72, dez. 2005. [ Links ]

HARRISON, Linda J.; SUMSION, Jennifer. Preface. In: HARRISON, Linda J.; SUMSION, Jennifer (ed.). Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care: exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research and practice. Springer New York: Springer, 2014. p. 5-6. [ Links ]

LANSKY, Samy; GOUVÊA, Maria Cristina Soares de; GOMES, Ana Maria Rabelo. Cartografia das infâncias em região de fronteira em Belo Horizonte. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 35, n. 128, p. 717-740, 2014. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, Henri. A produção do espaço. Tradução de Doralice Barros Pereira e Sérgio Martins (do original: La production de l’espace. 4. ed. Paris: Anthropos, 2000). Disponível em: http://www.mom.arq.ufmg.br/mom/02_arq_interface/1a_aula/A_producao_do_espaco.pdf Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Rita de Cássia. A organização do espaço da educação infantil: o que contam as crianças?. 2010. 166 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2010. [ Links ]

MÁXIMO, Luciana Perpetuo. Ações dos bebês em diferentes formas de organização do espaço e dos materiais em um ambiente de creche. 2018. 150 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Estadual Paulista, São José do Rio Preto, 2018. [ Links ]

NEVES, Vanessa F. A. MÜLLER, Fernanda. Ética no encontro com bebês e seus/suas cuidadores/as. In: ANPEd. Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação e Pesquisa em Eeducação. Ética e pesquisa em educação: subsídios. v. 2. Rio de Janeiro: ANPEd: Comissão de Ética em Pesquisa da ANPEd, 2021. p. 94-101. [ Links ]

NEVES, Vanessa F. A. et al. Dancing with the pacifiers: infant’s perizhivanyain a Brazilian early childhood education centre. Early Child Development and Care, London, jun. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1482891 [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Yoko Tachikawa de. Trajetórias e caminhos: uma cartografia dos bebês. 2016. 151 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2016. [ Links ]

RUTANEN, Niina. Lived spaces in a toddler group: application of lefebvre’s spatial triad. In: HARRISON, Linda J.; SUMSION, Jennifer (ed.). Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care: exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research and Practice. New York: Springer, 2014. p. 17-28. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Eloisa Acires C. “Diretrizes educacionais pedagógicas”. In: FLORIANÓPOLIS. Prefeitura Municipal de Florianópolis. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Diretrizes educacionais pedagógicas para a educação infantil. v. 1. Florianópolis: Prelo, 2010. p. 11-20. [ Links ]

SCHMID, Christian. Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space: towards a three-dimensional dialectic. In: GOONEWARDENA, Kanishka et al. Space, difference, everyday life: reading Henri Lefebvre. New York: Routledge, 2008. p. 27-45. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maurício Roberto da. Exercícios de ser criança: o corpo em movimento na educação infantil. In: ARROYO, Miguel; SILVA, Maurício Roberto da (org.). Corpo-infância: exercícios de ser criança; por outras pedagogias dos corpos. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012. p. 215-239. [ Links ]

SILVA, Viviane dos Reis. O que pensam as educadoras e o que nos revelam os bebês sobre a organização dos espaços na educação infantil. 2018. 272 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Sergipe, São Cristóvão, 2018. [ Links ]

SUMSION, Jennifer; HARRISON, Linda J. Introduction: exploring lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care. In: HARRISON, Linda J; SUMSION, Jennifer (ed.). Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care: exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research and practice. New York: Springer, 2014. p. 1-17. [ Links ]

SUMSION, Jennifer; HARRISON, Linda J. Harrison; STAPLETON, Matthew. Spatial perspectives on babies’ ways of belonging in infant early childhood education and care. Jornal of Pedagogy (Sciendo), Trnava, v. 1, p. 109-131, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2018-0006 [ Links ]

TEBET, Gabriela de Campos; ABRAMOWICZ, Anete. Estudos de bebês: linhas e perspectivas de um campo em construção. Educação e Temática Digital, Campinas, v. 20, n. 4, p. 924-946, out./dez. 2018. [ Links ]

VERSOV, Nikolai; FLEER, Marilyn. Perezhivanie as a theoretical concept for researching young children’s development. Mind, Culture, and Activity, Philadelphia, v. 23, n. 4, p. 325-335, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186198 [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semionovitch. Obras escogidas, IV. Madrid: Visor, [1932] 1996. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semionovitch. Quarta aula: a questão do meio na pedologia. Psicologia USP, São Paulo, v. 21, n. 4, p. 681-701, [1933] 2010. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semionovitch. Obras escogidas, II. Madrid: Visor, [1934] 1993. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. Psicologia e educação da infância. Lisboa: Estampa, [1954] 1975. [ Links ]

4For more information, see the International Cartographic Association (ICA) website and also Tebet and Abramowicz, 2018; Lanksy et al., 2014; Oliveira, 2014; Sumsion et al., 2014.

6Since 2012, as from Law 12.602, August 25 is celebrated as the National Day of Early Childhood Education throughout Brazil. This day was chosen in honor of the birth date of pediatrician and sanitarian Dr. Zilda Arns ( BRASIL, 2012).

7For example, in the case of conceived space and its supposed neutral nature, this intentionality is directly related to capitalist modes of action.

8In Belo Horizonte’s Municipal Education Network, there is the position of “Child Education Support Assistant”, for which a complete high school education is required. The working hours are 44 hours per week.

9In Belo Horizonte’s Municipal Education Network, teachers are entitled to four hours a week for collective planning activities.

10The empirical material was collectively constructed by the members of the research group. This fact facilitated the process of a long stay in the field: we remained in the field in the year 2017 for 80 school days (269 hours, 34 minutes and 11s of video recording).

11Our research group, based on the definitions proposed by Corsaro ( 1985) and Castanheira et al. ( 2000), defined an “event” as a sequence of actions (with the presence, or not, of other babies and adults) around a specific theme and/or with a purpose (even if it is not explicit). The event is an outcome of the interactional processes between participants and it is analytically identified a posteriori by recognizing its beginning, development and end. Events are interpreted through a dense analysis of who is doing what, with whom, when, how, for what purposes, and with what consequences, always focusing on their history and relations with other events ( NEVES et al., 2018).

Received: April 08, 2022; Revised: April 19, 2022; Accepted: June 06, 2022

texto en

texto en