Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.49 São Paulo 2023 Epub 27-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202349262397por

ARTICLES

With how many films can we talk about children? Childhood representational plurality in cinema 1

José Douglas Alves dos Santos holds a Ph.D. in Education from Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC). He is a pedagogue and master in Education from Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS). He is a member of Núcleo Infância, Comunicação, Cultura e Arte (NICA), writer, and a Collaborating Professor in the Didactics area of the Education Methodology Deparment at UFSC.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7263-4657

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7263-4657

Monica Fantin holds a Ph.D. in Education from UFSC with a period abroad at Università Cattolica di Milano. She is a full professor at the Education Graduate Program and the Pedagogy Undergraduate course from UFSC. She is the leader of the research group Núcleo Infância, Comunicação, Cultura e Arte (NICA, UFSC/CNPq).

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7627-2115

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7627-2115

2Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Ilha de Santa Catarina, SC, Brazil

This article presents part of the descriptive data about a doctoral study held between 2017 and 2021. The study problematized the formative, pedagogical, and aesthetic experience with films in an undergraduate Pedagogy degree. By highlighting children’s representational plurality through films, from a filmography review or film state of the art, this text aims to reflect on the significant amount of short, middle, and feature films that portray children in their different narratives. Regarding the methods used, we privileged the work in an interdisciplinary and multi-referential methodological conjunction based on Grounded Theory and scientific bricolage, backed by hermeneutic phenomenology. We point out 204 cinematographic works - from data on theses, dissertations, and scientific articles – from searches in theses and dissertations databases in digital libraries and journal platforms. The professors interviewed accounted for thirty productions. Faced with this number of works, we believe that films are part of students’ formative process and allow other interpretations of children and childhoods nowadays, revealing their relevance as a source and reference in the formative process.

Keywords Cinema and education; Children and childhoods; Teacher education; Filmography review; Cinematographic representations

Este artigo apresenta um recorte descritivo dos dados de uma pesquisa de doutorado realizada entre 2017 e 2021, cuja ênfase envolveu problematizar a experiência formativa, pedagógica e estética com filmes no contexto acadêmico, mais particularmente no curso de pedagogia. Ao salientar a pluralidade representacional das crianças por meio dos filmes, a partir de uma revisão filmográfica, ou do estado da arte fílmica, e com base nos relatos dos professores participantes do estudo, o objetivo deste texto é refletir sobre a quantidade significativa de curtas, médias e longas-metragens que representam as crianças em suas distintas narrativas. Em relação aos métodos utilizados, privilegiamos no trabalho uma conjunção metodológica interdisciplinar e multirreferencial, com base na Grounded Theory e na bricolagem científica, respaldada pela fenomenologia-hermenêutica. Evidenciamos um total de duzentas e quatro (204) obras cinematográficas entre as publicações analisadas – os dados referem-se a teses, dissertações e artigos científicos –, resultante de buscas no banco de teses e dissertações de bibliotecas digitais e em plataformas de periódicos. Entre os filmes descritos pelos docentes, contabilizamos trinta (30) produções. Consideramos, diante dessa quantidade de obras, que os filmes fazem parte do processo formativo dos estudantes e permitem outras leituras sobre as crianças e infâncias no contexto contemporâneo, o que revela sua relevância como fonte e referência no processo formativo.

Palavras-chave Cinema e educação; Crianças e infâncias; Formação docente; Revisão filmográfica; Representações cinematográficas

Contextualizing the study

This article refers to the research developed during a Ph.D. in the Education Graduate Program at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), in the Education and Communication (ECO) research line. The research focused on establishing approximations between pedagogy and cinema in the university training courses. Aiming to problematize the training experience, pedagogical, and aesthetic with films in the academic context, particularly in the Pedagogy undergraduate course, we analyzed the concepts of childhood and children’s representations through interviews with professors, trying to understand their narratives.

Qualitative research can be understood as a “process of reflection and analysis of the reality by using methods and techniques to fully understand the object of study in its historical context and/or structure” ( OLIVEIRA, 2007, p. 37). Regarding the methods used, we privileged a methodological interdisciplinary and multi-referenced combination based on Grounded Theory ( GOULDING, 1999) – also known in Portuguese, according to Tarozzi (2011) and Thomson and Cainelli (2020), as Teoria Fundamentada em Dados or simply Teoria Fundamentada – backed by the hermeneutic-phenomenology.

As Carter and Little (2007) point out, because the qualitative investigation focuses on understanding the meanings involving the studied object/subject, with no need to fit into a previous hypothesis, it allows different procedures and methodological approximations as long as they are duly articulated. We have done this in our work when bringing multidisciplinarity and multi-references inspired by the bricoleur perspective of research, which “instigates researchers to leave their spaces labeled as investigation, risking themselves when moving from one area to another,” as Rodrigues et al. (2016, p.973) highlight.

In its turn, hermeneutic phenomenology was present as a horizon and inspiration of an intellectual posture, allowing an analytical work that is not limited to hypotheses or pre-conceived ideas, nor would it allow us to distance ourselves from the object/theme investigated completely. According to Santos Filho and Gamboa (2009), it supports the data produced and analyzed because this approach uses a technique that recovers the meaning context of what is studied from analyzing the parts toward the whole.

As one methodological procedure, we conducted a state-of-the-art study to catalog works that dialogued with our perspective. According to Fantin, Santos, and Martins (2019), this methodological exercise helps researchers to have a “comprehensive panorama about the study problem, deepening their issues, or guiding them to delineate new questions, methodological procedures and/or theoretical approaches” ( FANTIN; SANTOS; MARTINS, 2019, p. 1159).

This exercise helped us delineate a question on the number of films used nowadays to analyze children and childhoods. Thus, besides a more traditional literature review, aiming for a state-of-the-art study of academic works on the theme from specific research sources and an established time frame, we also conducted a filmography review 3, a state-of-the-art study of the films used in articles, dissertations, and thesis – encompassing different periods – focused on the reflection of children and childhoods.

When using the descriptors “Child and cinema”/ “Childhood and cinema”/ “Children and cinema” / “Childhood and cinema,” we found fifty-nine works, forty-six of which were academic studies (thesis and dissertations) and thirteen were articles. This number resulted from searches conducted in databases of theses and dissertations of digital libraries (CAPES, BDTD, UDESC, UFSC, UFS, UNIT) and platforms of scientific journals (Scopus and Scielo). Two hundred and four cinematic works compose the corpus analytical, descriptive, or were used as examples in these publications.

In this text, we approached the terms child and childhood from the perspective of social sciences, in which these concepts had different meanings according to the sociocultural aspects. In this sense, ‘child’ is a more restricted concept associated with the child subject, this young person (or population), cultural producer, and holder of rights. Among its specificities is the contextual variety in which it develops, as the Belgian researcher Claude Javeau (2005) stresses, focusing more on a socio-anthropological perspective.

Childhood refers to a social category under change ( SARMENTO, 2004). Kuhlmann Júnior (2001) considers it a state condition of being a child, being understood in the context of relationships. According to the Portuguese historian Ernesto Martins (2018), it can be considered in its singular description, which would be connected to an ideal and universal representation or a plural one encompassing the singularity of these subjects. Therefore, in plural, childhoods represent and highlight the ways of being and living in particular social and cultural conditions.

In the table below, we organized the data from the sources used, describing the total of works in each digital library and article platforms used in this study, as well as the number of films in each one:

Table 1 - Filmography review of the state of art of film art

| Sources | Theses and Dissertations | Scientific articles | Film works |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAPES/BDTD | 08 | 42 | |

| UDESC/UFSC | 34 | 01 | |

| Unit/UFS | 04 | 03 | |

| Scopus/Scielo | 13 | 155 | |

| Total | 201 |

Source: Created by the authors.

Concerning the theme/conceptual axes in our research, the number of films found in these studies show the plurality of cinematic works representing children and childhoods, besides highlighting that the readings and interpretations about the films mainly involve the reference codes of each author. We notice different representations and approaches portrayed in or through cinema. If we could create a theme framework with all the protagonist children in these stories, or even those that are not central characters, we could see how much films can contribute to Pedagogy ( SANTOS, J., 2021).

We should highlight that, during the film review, or the film state of the art, on the theses and dissertations of the selected Programs, we prioritized the studies that directly approached some movie and not only mentioned them as a reflection or example. We did the same for the scientific articles. If we had used the same criterion, the total number would be higher.

Following what we proposed in this article, we bring part of a doctoral study, emphasizing the data that complement those previously mentioned, referring to the other methodological procedure that integrated our empirical work. We interviewed professors of the Pedagogy undergraduate course at the Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS). They told us about the movies they commonly use in their pedagogical practices. This allowed us to perceive how much films are part of students’ education and to what extent it is possible to reflect on children and childhoods in the contemporary context through film narratives.

Childhood representational plurality in the cinema: with how many films can we talk about children?

Considering the data collected during our film review and based on the reports of professors participating in the research, we can answer the question above simply and directly: with many. If we restrict our scope to the previously mentioned data, we notice many films representing children with certain specificities and interests. Even if such representation is not reliable or authentic from a scientific-pedagogical point of view – as a representation based on the concept problematized by studies from different areas and knowledge fields – films bring something from these subjects’ historical, political, and cultural context. Thus, films can dialogue with the pedagogical gaze in which the discourse about children is often delineated and circumscribed.

Most of the time, cinema deals with these subjects without the same intention as academic productions, helping to portray or unveil “truths” and other readings that do not always have a space or appear in the context of students’ university education. With a reading more guided by sensitiveness, the (re)education of our gaze through our sensitiveness – which can be as critical and social as others – the lenses of the cinema gaze can qualitatively approximate the formative and pedagogical scope.

To better understand these questions, we can consider the data from another research methodological procedure regarding one of the empirical phases. When interviewing professors from the Department of Education (DED) at UFS, we found the most used films in their pedagogical practices in the course and to what extent they dialogue with the central theme described here, children/childhoods in the different contemporary realities. In the following table, we situate the works indicated by each participant.

Table 2 - Films per professor at UFS pedagogy course

| Professors | Films |

|---|---|

|

AGBF (Bueno de Freitas) |

“ Vida Maria” / “ Vida José” / “A missão” / “Carlota Joaquina” / “Getúlio” / “ Villa-Lobos” / “ Entre os muros da escola” / “Pro dia nascer feliz” / “Olga” / “Aquarela do Brasil” |

|

AM (Menezes) |

“O Círculo” |

|

FAS (Santos) |

“O nome da rosa” / “Machuca” / “ Minha vida de menina” / “A Guerra do Fogo” |

|

FSR (Rocha) |

“O nome da rosa” / “História da civilização brasileira” / “Além do cidadão kane” |

|

IF (Freitas) |

“ XXY” |

|

JMAO (Oliveira) |

“Democracia em vertigem” / “Paterson” / “Janela da alma” / “Da escravidão moderna” / “Narradores de Javé” / “Milk” / “Divinas divas” / “Era o Hotel Cambridge” / “Medianeras – Buenos Aires na era do amor virtual” / “Jorge Malta – O filho do Holocausto” / “The square – A arte da discórdia” / “Crítico” / “O estranho mundo de Jack” / “Amor” / “Relatos selvagens” / “O Amor é Estranho” / “IDA” / “1984” / “O nome da rosa” / “ O começo da vida” / “ Elliot” |

|

MMT (Teles) |

“ Como estrelas na terra” / “A máquina do abraço” / “ O menino e o mundo” / “ A menina de cabelo de Brasil” / “ Alike” |

|

MJD (Dantas) |

“ O jardim secreto” / “ Oliver Twist” / “ A volta do Capitão Gancho” / “Escritores da liberdade” / “As mil e uma noite” |

|

MJNS (Soares) |

“A jornada da alma” / “A vila” / “Ponto de mutação” “A guerra do fogo” / “Giordano Bruno” / “O nome da rosa” / “A letra escarlate” / “Gênio indomável” / “Quebrando a banca” / “A teoria de tudo” / “A onda” / “Uma mente brilhante” / “ Sociedade dos poetas mortos” / “Jogo de imitação” / “Estrelas além de seu tempo” |

|

ML (Lucini) |

“ Tapete vermelho” / “ Alike” / “O conflito das águas” “ Sobre a violência” / “Narradores de Javé” / “ O substituto” / “Escritores da liberdade” / “ Uma lição de vida” / “ Quando sinto que já sei” / “Coleção EducaDoc: Saber, viver, lutar” |

|

RCSS (Souza) |

“ Gaby – Uma história verdadeira” / “Simples como amar” / “ Hotel Ruanda” / “ Sophia” / “O[um] gato preto” (animação) |

|

SAB (Bretas) |

“Ponto de mutação” / “O homem sem sombra” / “Uma cidade sem passado” |

|

SDZ (Zogaib) |

“ A escola da vida” |

|

TKGR (Ramos) |

“ Território do brincar” / “ O começo da vida” “ Bebês” / “ Em busca da terra do nunca” |

|

ACS (Cordeiro Santos) |

“Tempos modernos” / “Náufrago” (animação) “Aquarela do Brasil” / “Anísio Teixeira – Educação não é privilégio” |

Source: Created by the authors.

In total, we counted ninety-two works. At first, it was a high number, but it was understandable when we highlighted the choices individually: some professors work more with films than others. Furthermore, most participants work with at least three subjects per semester, contributing to this amount. The works in boldface on the table refer to films that, in our opinion, tend to articulate more fruitfully with our reflection regarding the approach to children/childhoods issues.

Therefore, according to the previous paragraph, we selected thirty of those that dialogue more closely with the theme, which helped answer the title question: with how many films can we talk about children? In advance, we can affirm that in the Pedagogy course of UFS, at least thirty. We have noticed that less than a third of the films mentioned by the professors fit within the exercise of deepening the gaze over children and childhoods, directly or indirectly. The others, though approaching issues relevant to training, do not fit the criteria that, pedagogically, allow their use with the pretext of the suggested problematization.

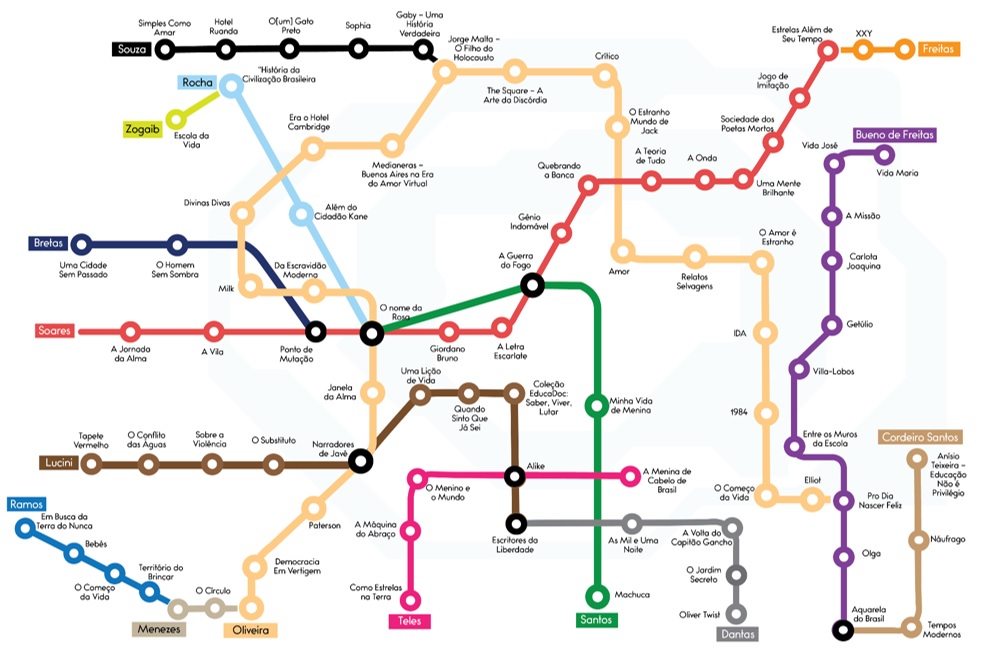

Using a simple imagination exercise, we can think about the list described in Table 2 of the films indicated by the professors as a conceptual map that shows the intersection points among the professors’ choices. Making an analogy with a subway map with stations and connections, we can portray such films in a “filmography map”.

Source: Created by the authors. The designer Kherlianne Barbosa did the art.

Figure 1 - Conceptual map (or filmography map) with the films of UFS professors

On the map above, the works mentioned by more than one professor form seven connection points, i.e., when a specific production was used by more than one professor in their respective subjects. For example, “O nome da rosa,” the most cited work during the interviews, was used by four professors: Oliveira, Soares, Rocha, and Santos. This data can be methodologically helpful for teachers, as when working with films, they can avoid excessive and repetitive use in the same classes and propose work activities in common.

Considering that the cinema in school or university “allows the contact of related subjects and the interaction with others, share intersection scenes, and do it from a global perspective and human interest 4”, as Francisco García García (2014, p.35) highlights. We can think about interdisciplinary collaborative actions involving the professors and students and the contents given in each subject, dialoguing with other knowledges and points of view. However, returning to the title question, we highlight the works closer to our discussion, which the professors use.

During the interviews with the professors, 5 we asked what subjects they typically taught and if they approached/problematized questions regarding children/childhoods. All of them expressed that the subjects touched the theme in some way, either more specifically in the syllabuses or content worked, or, more generally, from the elements/discussions brought by the professors in the debate – and with what objective.

Professor Bueno de Freitas commonly teaches K-12 Structure and Work, Education Structure and Work, and School Placement III. Of the ten films she mentions, we believe the first two, “Vida Maria” and “Vida José,” are more closely associated with our theme. These are two animated short films. The first is a national work, directed by Marcio Ramos, in 2007, which encompasses discussions on childhoods in the rural context. The second short film, which the professor mistakenly calls “Vida José 6” entitled The potter, is directed by Josh Burton, in 2005. It was an undergraduate final work in which the director presented similar issues to those found in “Vida Maria,” mainly regarding the learning process. When asked about why she used these works, she answered that she normally uses them to:

[...] understand a context, [...] even if knowing or calling students’ attention that this is a fiction work that can have approximations with that reality, [...] Certainly every film has a plot, a fictional perspective. Still, they allow us to access a context in which the school practices were experienced and can help us reflect on that time, that moment. When it is a documentary, or in the case of animations, the aim is to reflect from images, from the stimulus, how they perceive the education perspective or the exclusion of education, in this sense.

(Professor Bueno de Freitas).

In his turn, Professor Menezes is only responsible for the subject Development and Learning Psychology at the Education Department. The professor said he liked to use short narratives, such as films/videos from YouTube (preferably excerpts of scientific documents on science and psychology). As he does not typically repeat movies in the classroom, he mentions only one film, “O círculo” (The circle, from 2017, by James Ponsoldt). On his objective, due to what the professor called “content polysemy” that the video helps transmit, he believes that movies “instead of giving a single sense, they cause a heuristic explosion” (Professor Menezes).

Professor Santos, who works with the subjects Introduction to the History of Education and Brazilian Education, said he did not use films in his classes. He prefers to recommend them for students to watch at home. Of the movies cited, “Vida de menina” (2003, by Helena Solberg) is the closest to our theme. Based on the book “Minha vida de menina” by Helena Morley, this feature film portrays Brazil from the late 19th century from the diary of the character Helena, alternating her childhood and teenagehood moments.

As an objective, Santos indicates the “glimpse of that social configuration,” among other elements to reflect, such as “women’s social place,” that “education should not be limited to the school space and how non-schooled women placed themselves in that society,” and through scenes aiming to make students “see this other time reality” (Professor Santos).

Professor Rocha commonly teaches the subjects of Education and Communication Theories, Didactics, General Didactics, Politics and Education, and Geography Teaching for Early Elementary Education. According to him, the syllabuses do not encompass the discussion on children and childhoods, but he brings this discussion for the subjects because of his interest. The professor mentions the use of following works in the last semesters: “O Nome da rosa” (Der Name der rose, 1986, by Jean-Jacques Annaud); some videos from the collection “História da civilização brasileira” 7; and “Além do cidadão Kane”, mentioning, “Muito Além do Cidadão Kane” (Beyond Citizen Kane, 1993, by Simon Hartog). We believe these three are not closely related or deepen the discussion about children and childhoods.

As an objective, Professor Rocha said he aimed to “instigate, bring data,” referring to documentaries, so that they

[...] can promote a situation in which students can position themselves in this situation, so that they can reflect about the possibility of the things portrayed in the film actually happening or that this could happen to them. [...] to place them in a reflexive situation, the documentaries and the films emerge to reflect, to position themselves. This is the perspective [...].

(Professor Rocha).

Professor Freitas, who most frequently works on the subjects of Didactics, Study Seminar I, Study Seminar II, and Curriculum Theory, mentioned only one film from which he uses: “XXY” (2007, by Lucía Puenzo). The movie, a co-production between Argentina, Spain, and France, raises an important debate about biology and human relations. It could be used, even if not directly, to deepen specific questions about children/childhoods, though they are not the central focus of its narrative.

About his objective, the aim is not only to

[...] shock, to trigger a discussion about prejudice but to know what people are thinking, what goes on in their heads”. In this sense, he affirms that “the director intends to present a different experience to people, an understanding of different people for those that are called...that consider themselves conventional or normal, and, thus, triggering a discussion about prejudice. This is what they do. I use it for other things, not just to talk about discrimination. I use it to shock.

(Professor Freitas).

Professor Oliveira works with the subjects Didactics, General Didactics, Education and Communication Theory, Information and Communication Technologies in Education, Politics and Education, Education Structure and Work, Art and Education, Education Evaluation, and Fundaments of Online Education. He reports using many movies and other audiovisual works, considering that 50% to 60% of his classes use such works. Out of the movies cited, we believe that two directly dialogue with our theme “O começo da vida” (The beginning of life, 2016, by Estela Renner) and “Elliot”, meaning “Billy Elliot” (2000, by Stephen Daldry).

On his reason for working with these works and others, he states that he wants students to “understand cinema as Art, and not communication, to experience a particular and subjective experience that potentializes this in discussion with others.” Oliveira says that “in general, all movies, regardless of the theme, is cinema, not Communication.” They help to

[...] develop sensitiveness [...] because audiovisual, in particular cinema, potentializes this more than the written text, mainly for those barely literate, have problems reading and writing, or do not read regularly.

(Professor Oliveira).

Another objective he mentions is

[...] to understand that audiovisual is maybe the most efficient form of art, communication, and information, as it looks pretty similar to reality because it makes this optical illusion [...] so I defend an imaginative pedagogy. Cinema helps transport us to various moments, historical times, different spaces, even condensing time, a lifetime in an hour and a half, or the history of humanity in one hour and a half.

(Professor Oliveira).

Professor Teles works more frequently with the subjects of Inclusive Education, School Placement III, and Art and Education. Among the films she mentions, four fit our research proposal of thinking about children and childhoods through cinema due to the knowledge that emerged from this aesthetic experience in pedagogy: “Como estrelas na terra” (Taara zameen par, 2007, by Aamir Khan and Amole Gupte), “O menino e o mundo” (2013, by Alê Abreu), “A menina de cabelo Brasil” – in fact “Imagine uma menina com cabelos de Brasil...” (2010, by Alexandre Bersot) – and “Alike,” entitled “Escolhas da vida” in Brazil (2015, by Rafa Cano Méndez and Daniel Martínez Lara).

These works are used to

[...] reflect, for students to think about their practice and what they are seeing, studying, and reading. They are always associated with the discussion in the classroom, the problem that students bring in this discussion, to reflect, because it is visual support [...] students see situations that bring this situation to their context, in which they live [...] to reflect about life. However, she recognizes that it is “challenging to work with films because we are still very much tied to the written text.

(Professor Teles).

Professor Dantas typically teaches the subjects Education Evaluation, School Placement I, Mathematics Literacy, Children’s Social History, Curriculum Theory, Education Sociological Fundaments, and Adult Education. Among the works she mentioned using in the last semesters, three are related more closely to our theme: “O Jardim Secreto” (The Secret Garden, 1993, by Agnieszka Holland), “Oliver Twist” (2005, by Roman Polanski), and “A volta do Capitão Gancho” (Hook, 1991, by Steven Spielberg).

When questioned on the aim of using these works, she said:

Always illustrate the texts we are working on in the classroom. In the case of Jardim Secreto, we had already worked with Ariès’s texts; in the case of Oliver Twist, we were working with the text Pequenos Trabalhadores do Brasil [Little Workers from Brazil], which, as in Oliver, approaches the issue of child labor. So, I always use films and videos as illustrations to work some text and ground them. So, it was in this sense. We work on a text, and then I bring a film that can help us understand it and bring some message to debate the text.

(Professor Dantas).

Professor Soares usually teaches the subjects of Ethics and Environmental Education, Countryside/Rural Education, and School Placement IV. From her long list of films mentioned, we highlight the film “Sociedade dos Poetas Mortos” (Dead Poets Society, 1989, by Peter Weir), which could be closer (even if indirectly) to our reflections because the film brings elements to think the formative and educational process with more emphasis on young people than children. However, few can trace some associations with the school trajectory/inheritance of many children besides the academic logic established in the education institutions that reflect in society.

About the objective of using these films, Soares answered by bringing the example of the movie “A Vila” (The Village, 2004, by M. Night Shyamalan), in which she sought to discuss how society is designed, bringing examples of books from Durkheim, to:

[...] show the importance of this human nature, designed within the social wall, then I say that this is school, this panopticism done of people. [...] So I use these films to illustrate, [...] because people see better when watching a movie, watching the news, or seeing a photo.

(Professor Soares).

Professor Lucini usually teaches the following subjects: Curriculum Theories, Countryside/Rural Education, Didactics, and Special Topics I. Regarding the films used, we believe that six from her list directly dialogue with our themes from a more plural perspective of children/childhoods: “Tapete Vermelho” (2005, by Luís Alberto Pereira), “Alike” – previously mentioned by Professor Teles –, “Sobre a violência” (Om våld, 2014, by Göran Olsson), “O Substituto” (Detachment, 2011, by Tony Kaye), “Uma Lição de Vida” (The first grader, 2010, by Justin Chadwick), and “Quando sinto que já sei” (2014, by Antonio Sagrado, Raul Perez, and Anderson Lima).

About the objective of using films, she mentions how these works potentialize students’ conception of the world and profession.

When I say, “Look, Frantz Fanon, calls attention to the recolonization of everyday life, for racism, and the colonization process”. When I worked on the issue of ‘Escritores da liberdade’ [that as it focuses more on young people, we did not conclude in the selected list], the aim was to think about didactics, as my didatics contribute or not to transform myself, contribute in the transformation of life, or empower students for transformation. ‘Tapete Vermelho’ was also this, to problematize this [...] live in the countryside, how we reach this concept of rural man and how they see the city in these perspectives.

(Professor Lucini).

Professor Souza usually teaches Fundaments of Inclusive Education, Special Topics in Education, and Philosophical Fundaments of Education for the Deaf. Among the films, we highlight three that are closer to a proposal of rethinking the children/childhood notions from movie images: “Gaby: uma história verdadeira” (Gaby: a true history, 1987, by Luis Mandoki), “Hotel Ruanda” (Hotel Rwanda, 2004, by Terry George) and “Sophia”, refering to “O mundo de Sofia” (Sofies verden, 1999, by Erik Gustavson).

Regarding the proposed objective, she states:

[...] I always use them to allow more possibility to reflect on the themes. To have a critical sense, understand the contexts, and not have a linear reading. For example, suppose you have a deaf student in class. In that case, you cannot think that your student will only need Libras [Brazilian Sign Language], so when he watches a movie, he understands the general life context, the relationship with family and friends, in school, how all of this takes place, it is not enough to have an interpreter in the classroom, they also need more support and end up seeking more knowledge to, in their pedagogical know-how in the class, they do not have a limited understanding about the teaching-learning process. I always seek these objectives and many others. The more contextualized the work, the more it is a part of you.

(Professor Souza).

Furthermore, she affirms that she likes to use films for discussions, mentioning the project CineFórum, developed on the subject of Fundaments of Inclusive Education, in which she works

[...] with different themes, visual handicap, deafness, syndromes, etc. I always show a film related to the theme, [...] we study about the theme and after watching the movie we debate it and the content we are working on”. She believes she has a good return from the students and prefers to show them in the classroom, “sometimes when there is no time in the schedule, we suggest them to see it at home, but I usually prefer to do it in the classroom so that we can later construct this debate because I think the exchange is richer.

(Professor Souza).

Professor Bretas, when acting with Education Research, Fundaments of Scientific Investigation, Study Seminar I and II, affirms that the subjects’ syllabuses do not raise questions to think about children and childhoods, but she still works with the themes. She cites three films she likes to work with: “Ponto de mutação” (Mindwalk, 1990, by Bernt Amadeus Capra), “O homem sem sombra” (Hollow man, 2000, by Paul Verhoeven), and “Uma cidade sem passado” (Das schreckliche mädchen, 1990, by Michael Verhoeven). Considering the purpose of this text, they bring no possibilities to deepen the themes in question.

About the objective of using these films, Bretas describes the illustrative nature of the exercise:

[...] illustrating it, I like that because I think it broadens students’ perspective, a topic that is normally dealt with with theoretical texts can be closer to the student if you seek other resources, as meaningful as the texts, we do not abandon the texts, the discussion, but the student in general gets more involved with the topic because of the audiovisual resources, the movies especially.

(Professor Bretas).

Professor Zogaib teaches the subjects of Mathematics Literacy, Mathematics Teaching in the Early Years, School Placement, and Children’s Social History – the last one closer to our theme. She states that she always uses audiovisual elements. However, she only remembered the name of one movie with which she worked in the classroom, “A escola da vida” (L’école buissonnière, 2017, by Nicolas Vanier).

Using an example of the subject School Placement, she showed the film because of the way

[...] the professor brought the subject of history for children’s everyday lives, for their lives, and turned the classroom into an environment that lived this history [...]. So, to show there are other ways of working with children and work with the foreseen content, the content that, in a way, is meaningful to them. So the films deal with this and the relationships, the teacher-student relationship, peer relationship, and the issues of envy, prejudice against a new teacher, and a newcomer. So all the issues students deal with in their routine, as a teacher in the school. We discussed this experience of being a teacher in school.

(Professor Zogaib).

Professor Ramos normally teaches the subjects Fundaments of Childhood Education, Education of 0-3-year-old Children”, Children’s Social History, and Childhood Education School Placement. She brought four movies that directly dialogue with the idea developed here: “Território do brincar” (2015, by Renata Meirelles David Reeks), “O começo da vida” – também mencionado pelo professor Oliveira –, “Bebês” (Bébé(s), 2010, by Thomas Balmès), and “Em busca da terra do nunca” (Finding neverland, 2004, by Marc Forster).

Concerning the objective, we bring the example she cites referring to the film “Em busca da terra do nunca” which she worked with in two ways. We can associate one of them with fruition and the other as connected with an educational objective, with some established pedagogical criterion:

One is a shorter except, to work with the concept of make-believe, its relationship with the child, and how it takes place in everyday life. Another time, I watched with the group as a way to touch them, and then there was no objective. We just watched it.

(Professor Ramos).

Professor Cordeiro Santos, who was in her first year as a substitute professor, was responsible for Education Policies and Management, School Placement I, Undergraduate Dissertation Advising I and II, Education Structure and Working, and K-12 Structure and Working. None of the films she mentioned would fit the themes discussed here.

When referring to her use of movies, Professor Cordeiro Santos also affirms that “it is not simply showing the movie, it has to be related with what we are working, to have a direct relation

It is crucial to cause this impact. To raise questions. When he [student] watches a movie, he thinks, “Well, but they lived in this perspective. What do I have to do with this? Does that relate to what I experience?”. Bring references from different contexts. [...]. It is always related to the objective of the class. If I work with an author, I try to bring something from that author to ground better what I am doing, and not to be only restricted to the text we are reading.

(Professor Cordeiro Santos, 2019).

Based on these data, we can identify works used by the professors in their formative practices with undergraduate Pedagogy students. At the same time, only a part is more specifically related to children/childhood themes. The fact that professors used such works shows a dimension of these films in student training and a possibility of rethinking this practice. When identifying the movies and the professors’ objectives, professors can open a new communication channel, aiming to dialogue and work together; thus avoiding the excessive repetition of some movies with students and proposing interdisciplinary readings.

Through the reports described here, we have noticed that, in most cases, the movies are used as a support to illustrate specific content. In others, they are mentioned as having the same weight as other pedagogical resources. However, the idea of movies as a teacher tool in favor of a particular theme or subject is still explicit. This does not mean less pedagogical values; it only shows a practical dimension of cinema use in school and university.

When seeking an “approximation” with certain “contexts” and “realities” and aiming to reflect on them, Professor Bueno de Freitas recognizes that films, even in their “fictional perspective,” can contribute to revealing aspects of the present time and reality in which individuals are inserted (and even in different realities). In this case, they act as mediators of cultural phenomena through which it is possible to establish other readings and interpretations through its representative dimension ( FERRARA, 2002; ROSENSTONE, 2010; SANTOS, D., 2011). Professor Santos also highlights this access power through the images of another “temporal reality,” though he prefers to recommend films to the students without showing them in the classroom.

All the professors ’ interviews present this perception of movies as thought mobilizers ( BERGALA, 2008; FRANCO, 2013; PALLASMAA, 2018). However, some mentioned them more in the didactic purpose movies can have concerning the content. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that shows this aesthetic operation with the movies beyond such end, as we could perceive in the interviews with Bueno de Freitas, Teles, Rocha, Oliveira, Lucini, Souza, Zogaib, Ramos, and Cordeiro Santos.

Professors notice this, especially when students see the possibility of an event in the scenes, which is associated with the idea of cinematographic representation as a form to re-guide our gaze on the social reading of the world ( FANTIN, 2014). Reading through movie representations involves multiple interpretations, closer to what some theoreticians ( MOSCOVICI, 1978; CHARTIER, 2001; 1990; MANGUEL, 2001; FANTIN, 2011; HALL, 2016) observe: different cultural realities might be appropriated, producing other senses, which not necessarily focus on a fixed point about the presented events.

Professor Oliveira says he works with films considering them as texts, approaching them more as Art than Communication, as an artistic language that can produce meanings by sharing and making sensitiveness ( RANCIÈRE, 2005; BERGALA, 2008; ARROYO, 2009; FANTIN, 2009; ALMEIDA, 2017).

Professor Dantas commonly uses films as illustrations. After discussing the issue of the subject or reading about it, she can show a movie to help students remember and understand the contents. This is generally how the teachers use the films, grounded on images for learning support ( MEDEIROS, 2012; ALMEIDA, 2017). We can also identify this in the words of the Professor when she mentions how she uses films to illustrate because she believes students will understand it better.

We believe that this practice should not be considered counterproductive, as it can contribute to assimilating the contents needed for school and/or academic training, as sometimes happens ( COELHO; VIANA, 2011; CLARO, 2012; SANTOS, J., 2016), and can raise more interest and engagement with the students. Professors Bretas and Zogaib also consider movies as meaningful resources as any others in the formative context.

The central point of the debate, in this case, is that when synthesizing or being guided by this perspective, there is the risk of displacing films “from the condition of cinematographic art to be reduced to pedagogical products,” as Almeida (2017, p.7) reflects regarding the “cinema pedagogization.” In this case, for the author, the aesthetic operation that cinema in school allows “strips itself from its imaginary and its condition as a work of art to serve didactic-pedagogical proposals that transform it into a referent of a meaning that is somewhere else and not in the movie itself” ( ALMEIDA, 2017, p. 7), when the practice is limited to its illustration use.

Unlike Professor Menezes, who typically shows movie excerpts, or Santos and Soares, who prefer to recommend movies for students to watch at home, Souza likes to show the whole film in the classroom because she believes the debate can be more enriching. When seeking the possibility of reflection that movies can produce, she is closer to professors Bueno de Freitas, Rocha, Teles, Oliveira, and Lucini regarding such pedagogical practices in teacher training.

Final remarks

We know that there are multiple and of different orders of film used in the school/university formative context, with approaches focused either on the content taught in the subjects (mainly aiming to highlight certain issues or themes and help the assimilation of the theme) or on the aesthetic experience that such works may provide ( recognizing the need for a “less” conceptual approach facing the demand presented by students, which, not rarely, lack in their private formation the collective experiences of cinema and other arts, often granting them in the pedagogical discourse a less reflexive dimension, targeting entertainment 8).

However, we also know that such practices are not the only ones. We could think about approaches that instigate interdisciplinary works when teachers from different subjects show and mediate the same film; others aim for theoretical-practical guidance on a specific theme; others deeper analyses about film elements, emphasizing the technical dimension of the cinematographic action; others prefer to historicize, contextualize, and/or criticize certain narratives; others focus on the artistic-pedagogical production in the face of or from specific works; among other possibilities.

We cannot consider such approaches as fixed practices, in which there is no (or does not seem to have) dialogue among them. They are frequently used in parallel, or this is not their intention. When showing a movie as a recreational activity, with no evaluation nature, professors are also creating a moment of reflection; when they show the same movie to different classes or different professors and their subjects, some theoretical-practical guidance can be developed, some excerpts of the movie can bring a more technical approach of the narrative elements; before and/or the movie exhibition it is possible to historicize, contextualize, or even criticize the film; after the exhibition, it is possible to propose activities focused on the movie production; among many other possibilities.

The multiple work possibilities and approaches to the movies in the context of school-university formation also show a methodological reach that such practices can bring – which can go beyond the initial teacher’s planning when sometimes focusing only on one of these aspects or possibilities. Concerning the text’s objectives, we bring the result of two methodological procedures used in the research developed – the first part of the article, the film review from the movies used in articles, dissertations, and theses. In the second part, complementing the reflection, we bring data referring to the films used by professors from the Pedagogy course at the Universidade Federal de Sergipe.

We have found that, among the fifty-nine academic works found in the first part, resulting from the searches in the databases of theses and dissertations in digital libraries (CAPES, BDTD, UDESC, UFSC, UFS, UNIT) and platforms of scientific journals (Scopus and Scielo), in a total of two-hundred-four film works. In the second part, we could find ninety-two works during professors’ interviews.

By highlighting the high number of films (92) that are usually worked in the Pedagogy undergraduate course in the researched institution – thirty approaching more specifically children/childhoods in their narratives – and also the number of films in scientific publication – 204 in dissertations, theses, and journals – we believe that, due to this amount, films are present and part of students’ training process.

Regarding the question in the work title, “With how many films can we talk about children?”, we could notice a significant number of productions worked in the academic context, directly in the pedagogical practices in the classroom or theoretical reflection from such uses. Hence, we also highlight the representational plurality with which cinema portrays children and childhoods.

Thus, having access to such a number implies reflections about the films used and/or theoretical-methodological possibilities associated with students’ training through cinema. What allows us to perceive how films are part of students’ training process and to what measure we can use them to reflect on children and childhoods in the contemporary context.

Similarly to the representational plurality with which cinema approaches childhoods, we have also noticed the multiple natures of the work with films in pedagogy through the interviews with professors. Such an aspect indicates the diversity of educational conceptions presupposed in how movies are mobilized during teachers’ training. Be it to “understand a context” or to create “approximations” with a reality (Professor Bueno de Freitas); to work and foment the “polysemy of content” (Professor Menezes); to “perceive [...] another temporal reality” (Professor Santos); “instigate, raise data,” “establish a reflection situation” (Professor Rocha).

Or even “shock,” “to know what people are thinking,” and “trigger a discussion” (Professor Freitas); maybe live “a particular, subjective experience,” potentializing “this in the discussions, in the relationship with others,” what helps “develop sensitiveness” defending “an imaginative pedagogy” (Professor Oliveira); “reflect, so that students can think about their practice,” and “about life” (Professor Teles); “as an illustration to work with some text, as a grounding source”, to “help understanding” (Professor Dantas).

Still, “because people see better when watching a video, when watching the news, or when seeing a photo” (Professor Soares); “to think didactics, and how [...] it contributes or not for its transformation, contributes in life transformation, or empowers students for transformation” (Professor Lucini); to allow more “reflections about the themes [...], understand the contexts, so as [...] not to have a linear reading” (Professor Souza); “because [...] it really broadens students’ perspective” (Professor Bretas); “to show that there are other forms of work [...] and to work what is foreseen, the contents” (Professor Zogaib); “to work a concept,” or, sometimes, “just to touch them” (Professor Ramos), what is sometimes undervalued in training; to seek “a relationship with what we are studying” and, hence, causing an “impact,” to “raise questions”, ” to bring references from different contexts” (Professor Cordeiro Santos).

When considering that film texts allow other pedagogical readings in the institutional space about the themes approached, it is possible to assume its relevance as a source and a reference in such a process. Beyond the books as the primary material references present in the formation, the movie narratives are a relevant and necessary theoretical and reflexive base with conceptual pedagogical guidance.

Be in short, medium, or feature films, through documentaries, animations, dramas, and science fiction, among others; these productions have contributed to other readings and interpretations about these concepts. This leads us to reiterate how cinematographic narratives can contribute to pedagogy (with teachers’ training in general), with students’ formation – proposing readings and reflections situated in another linguistic-media dimension.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Rogério de. Cinema e educação: fundamentos e perspectivas. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, n. 33, e153836, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698153836 [ Links ]

ARROYO, Miguel G. Imagens quebradas: trajetórias e tempos de alunos e mestres. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2009. [ Links ]

BERGALA, Alain. A hipótese-cinema. Rio de Janeiro: Booklink: CINEAD-LISE-FE/UFRJ, 2008. [ Links ]

CARTER, Stacy M.; LITTLE, Miles. Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, Thousand Oaks, v. 10, n. 17, p. 1316-1328, sept. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307306927 [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história cultural: entre práticas e representações. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand, 1990. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. Cultura escrita, literatura e história. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2001. [ Links ]

CLARO, Silene Ferreira. Cinema e história: uma reflexão sobre as possibilidades do cinema como fonte e como recurso didático. Augusto Guzzo Revista Acadêmica, São Paulo, n. 10, p. 113-126, dez. 2012. https://doi.org/10.22287/ag.v1i10.132 [ Links ]

COELHO, Roseana Moreira de Figueiredo; VIANA, Marger da C. Ventura. A utilização de filmes em sala de aula: um breve estudo no Instituto de ciências exatas e biológicas da UFOP. Revista da Educação Matemática da UFOP, Ouro Preto, v. 1, p. 89-97, nov. 2011. Disponível em: https://www.repositorio.ufop.br/handle/123456789/7210 Acesso em: ago. 2017. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica. Audiovisual na escola: abordagens e possibilidades. In: BARBOSA, Maria Carmen Silveira; SANTOS, Maria Angélica (org.). Escritos de alfabetização audiovisual. Porto Alegre: Libretos, 2014. p. 47-67. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica. Cinema e imaginário infantil: a mediação entre o visível e o invisível. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 34, n. 2, p. 205-223, jul. 2009. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica. Crianças, cinema e educação: além do arco-íris. São Paulo: Annablume, 2011. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica. Crianças, cinema e mídia-educação: olhares e experiências no Brasil e na Itália. 2006. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2006. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica. Experiência estética e o dispositivo do cinema na formação. Revista Devir Educação, Lavras, v. 2, n. 2, p. 33-55, jul./dez. 2018. [ Links ]

FANTIN, Monica; SANTOS, José Douglas Alves dos; MARTINS, Karine Joulie. Black mirror e o espetáculo revisitado: um estado da arte e algumas reflexões. Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 19, n. 62, p. 1147-1173, jul./set. 2019. https://doi.org/10.7213/1981-416X.19.062.DS12 [ Links ]

FERRARA, Lucrécia D’Alessio. Design em espaços. São Paulo: Rosari, 2002. [ Links ]

FRANCO, Marília. O cinema jamais foi mero entretenimento – entrevista por Marcus Tavares. Revistapontocom, Ouro Preto, jul. 2013. Disponível em: http://programajornaleeducacao.blogspot.com/2013/07/o-cinema-jamais-foi-e-ou-sera-mero.html Acesso em: mar. 2020. [ Links ]

GARCÍA GARCÍA, Francisco. El cine como ágora: saber y compartir las imágenes de un relato fílmico. In: ALVES, Luis Alberto; GARCÍA GARCÍA, Francisco; ALVES, Pedro. Aprender del cine: narrativa y didáctica. Madrid: Icono14, 2014. p. 21-39. [ Links ]

GOULDING, Christina. Grounded theory: some reflections on paradigm, procedures and misconceptions. United Kingdom: University of Wolverhampton, 1999. (Working paper series). [ Links ]

HALL, Stuart. Cultura e representação. Rio de Janeiro: PUC: Apicuri, 2016. [ Links ]

JAVEAU, Claude. Criança, infância(s), crianças – Que objetivo dar a uma ciência social da infância? Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 26, n. 91, p. 379-389, maio/ago. 2005. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, Moysés. Infância e educação infantil: uma abordagem histórica. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2001. [ Links ]

MANGUEL, Alberto. Lendo imagens. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2001. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Ernesto Candeias. As infâncias na história social da educação: fronteiras e intersecções sócio-históricas. Lisboa: Cáritas, 2018. [ Links ]

MEDEIROS, Sérgio Augusto Leal. Imagens educativas do cinema/possibilidades cinematográficas da educação. 2012. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, 2012. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, Serge. A representação social da psicanálise. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1978. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Maria Marly de. Como fazer pesquisa qualitativa. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

PALLASMAA, Juhani. Essências. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili, 2018. [ Links ]

RANCIÈRE, Jacques. A partilha do sensível: estética e política. São Paulo: Ed. 34, 2005. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Cicera Sineide Dantas et al. Pesquisa em educação e bricolagem científica: rigor, multirreferencialidade e interdisciplinaridade. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 46 n. 162 p. 966-982, out./dez., 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143720 [ Links ]

ROSENSTONE, Robert A. A história nos filmes, os filmes na história. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2010. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Dominique Vieira Coelho dos. Acerca do conceito de representação. Revista de Teoria da História, Goiânia, v. 3, n. 6, p. 27-53, dez., 2011. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.ufg.br/teoria/article/view/28974 Acesso em: mar. 2018. [ Links ]

SANTOS, José Douglas Alves dos. Cinema e ensino de história: o uso pedagógico de filmes no contexto escolar e a experiência formativa possibilitada aos discentes. 2016. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão, 2016. [ Links ]

SANTOS, José Douglas Alves dos. Infâncias na tela, múltiplos olhares: representações das crianças no cinema e na pedagogia. 2021. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS FILHO, José Camilo dos; GAMBOA, Silvio Ancizar Sanchez. Pesquisa educacional: quantidade-qualidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 2009. [ Links ]

SARMENTO, Manuel Jacinto. As culturas da infância nas encruzilhadas da segunda modernidade. In: SARMENTO, Manuel J.; CERISARA, Beatriz. Crianças e miúdos: perspectivas sociopedagógicas da infância e educação. Porto: ASA, 2004. p. 9-34. [ Links ]

TAROZZI, Massimiliano. O que é grounded theory? Metodologia de pesquisa e de teoria fundamentada nos dados. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2011. [ Links ]

THOMSON, Ana Beatriz A.; CAINELLI, Marlene. Grounded theory: conceito, desafios e os usos na educação histórica. Educação Unisinos, São Leopoldo, v. 24, p. 1-19, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4013/edu.2020.241.18749 [ Links ]

1- See: SANTOS, José Douglas Alves dos. Infâncias na tela, múltiplos olhares: representações das crianças no cinema e na pedagogia. 2021. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2021.

3- Though we know there are different conceptual specificities, in this text, we use “filmography” and “cinematographic”, as well as “film” and “cinema” as synonyms to avoid the repetitive use of the theme and because we consider its interpretative plurality, even if, in the stricto sensu, cinema is defined as the device/dark room, while film is the text/language, in the context of reception/fruition/mediation. See: Santos, J. (2021) and Fantin (2006 , 2011 , 2018).

4- “Allows the subjects to be in contact and interact with one another, sharing intersection themes and doing so from a global and human interest perspective.”

5- The interviews were conducted in the first semester of 2019, during the empirical phase of the doctoral research. The participants authorized the use of the data produced for academic ends and their identification in the work and future documents. As the study answers a more specific public, the work did not go through the Ethics Committee, using a self-declaration of ethical principles and procedures in research.

6- Until now, the short film has no official title in Portuguese. It is entitled “Vida José” in a video posted on YouTube.

8- We highlight that, regardless of the film and approach, when connected with a practice more associated with entertainment (a non-evaluation or compulsory activity with students), we consider it is also reflective, as it instigates in the audience, according to Juhani Pallasmaa (2018), a “bio-historical” and “existential” reflection – involving memories and experiences that allow sensorial-corporal “meetings/resonances” that influence individual perceptions.

Received: March 24, 2022; Accepted: July 04, 2022; Revised: May 26, 2022

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

texto en

texto en